Significance

Various sources have reported insect decline in total biomass, numbers, and species diversity. With German data on a species-rich hoverfly community over 25 y and a theoretical model, we show how these decline rates are interrelated. The relationship between biomass and diversity losses depends on whether common or rarer species are most affected. Our analyses show stronger declines of common than rare hoverfly species. Strong reductions (up to −80%) in total abundance and biomass correspond with observed species richness declines of −20% to −40% on a seasonal basis. On a daily basis, however, hoverfly diversity declined in proportion to biomass loss, with important consequences for the functioning of ecosystems.

Keywords: biodiversity loss, insect decline, temporal scaling

Abstract

Reports of declines in biomass of flying insects have alarmed the world in recent years. However, how biomass declines reflect biodiversity loss is still an open question. Here, we analyze the abundance (19,604 individuals) of 162 hoverfly species (Diptera: Syrphidae), at six locations in German nature reserves in 1989 and 2014, and generalize the results with a model varying decline rates of common vs. rare species. We show isometric decline rates between total insect biomass and total hoverfly abundance and a scale-dependent decline in hoverfly species richness, ranging between −23% over the season to −82% at the daily level. We constructed a theoretical null model to explore how strong declines in total abundance translate to changing rank-abundance curves, species persistence, and diversity measures. Observed persistence rates were disproportionately lower than expected for species of intermediate abundance, while the rarest species showed decline and appearance rates consistent with random expectation. Our results suggest that large insect biomass declines are predictive of insect diversity declines. Under current threats, even the more common species are in peril, calling for a reevaluation of hazards and conservation strategies that traditionally target already rare and endangered species only.

Recent reports from lowland Germany have demonstrated a 3/4 loss in the biomass of flying insects in protected areas over a period of less than 30 y (1), as well as severe declines in abundance for several groups of insect species (2). These findings question the stability of ecosystem functioning under contemporary European land use. A biomass drop of such proportions can hardly be envisaged without cascading trophic effects (3–5) or without disruptions in pollination (6–8) and nutrient cycling (9). Most of these potentially far-reaching consequences will depend on the nature of the decline with respect to the abundance and diversity of the insect species in question (10). Hence, there is an urgent need to unravel whether and how total insect biomass decline translates into declines in the abundance and richness of insect species.

Long-term, taxon-specific studies on insects have revealed ongoing numerical declines and range contractions over the past decades (11–22). However, it is difficult to reconcile their findings with insect biomass decline as they represent 1) different facets of diversity changes (changes in areal coverage, species lists, abundance, and biomass), 2) differences in sampling methodology, and 3) differences with respect to the spatial and temporal scale of inference. As such, it is not straightforward to predict how the 3/4 decline in total flying-insect biomass in the Krefeld data (1) translates into abundance and diversity loss of insect species. Nonetheless, whether or not biomass losses are equally distributed over rare and common species could have large consequences for ecological functionality, such as affecting food availability at higher trophic levels (23, 24).

Interspecific variation in abundance changes may help uncover factors associated with the observed insect biomass loss. However, to predict the relationships between total insect biomass declines with persistence and abundance changes at the species level, as well as changes in diversity metrics at the community level, requires that we account for the stochastic nature of the processes involved (e.g., higher extirpation rates for rare species) (25, 26). Additionally, imperfect species detection during sampling in the field (i.e., species with low abundance could easily be missed) prevents a straightforward comparison of insect assemblages over time (27). To facilitate a meaningful analysis, we developed a theoretical framework, in which variability in rate of species decline as well as imperfect detection are integrated, permitting us to investigate how species persistence and diversity measures (Hill numbers) are theoretically affected under contrasting scenarios of decline rates along the common-to-rare species abundance axis. Such a framework is also crucial for properly interpreting empirical data of declining catches over time.

Next, we here examine the relationship between total insect biomass and diversity in an insect family: the hoverflies (Syrphidae). Hoverflies are considered important wild pollinators (28–30), important agents in biocontrol (31–33), suitable as bioindicators (34, 35), and hence a potentially informative group of insects, representative for a variety of ecological functions. All hoverfly individuals caught in six trap locations in German nature reserves in two seasons that were 25 y apart (1989 vs. 2014, two endpoints of the trend in the Krefeld data as described in ref. 1, with identical trap locations in each season) were identified at the species level, amounting to 19,604 individuals of 162 species from 59 genera.

We investigated how samples of total flying-insect biomass reflect changes in diversity of hoverflies, which form only a small subset (5% share in total flying-insect biomass; SI Appendix) in these samples of insect communities. We then compare these empirical findings to the theoretical results on hoverfly species, to establish how rates of decline are shared among common and rare species. Finally, we compare the rate of decline in total abundance and species richness of hoverflies at two temporal scales: across the season and daily (quantified as a latent variable in our analyses of the insect data based on variable trapping duration).

Theoretical Results

We first explore how the total biomass of a community depends on the abundance and richness of its constituent species. Declines in total insect biomass implicate declines in total insect abundance. However, total biomass declines may come about as a result of species loss, abundance loss, decline of especially the heavier species, or any combination of these mechanisms. At the same time, observed loss of species depends on the relative abundance of the species in the community, as well as on the variation in rate of decline among locally common and rare species. Small populations tend to be more sensitive to demographic and environmental stochasticity and as a result more prone to local extirpation (25, 26), even if their rates of decline (up to extirpation) equal those of more common species.

Under the assumption of a Poisson distribution of species abundance, and given the population “growth” rate of each species (e.g., ; if < 1 a population is declining), the number of species that are expected to still be present at a given time point () is given by

| [1] |

Here we assume three different scenarios: (I) a uniform decline rate among species, (II) common species declining more rapidly than rare species, and (III) rare species declining more rapidly than common species (Fig. 1A). Additionally, we acknowledge that direct assessment of species loss is inhibited by imperfect detection. For a given sampling efficiency (i.e., the fraction of locally present individual insects that are trapped), the expected number of species detected is given by

| [2] |

which shows that besides sampling efficiency, observed richness also relies on the abundance of each species (; i.e., the number of individuals available to be trapped from species ). In SI Appendix, we provide further details on the steps undertaken to derive species decline rates for each of the scenarios.

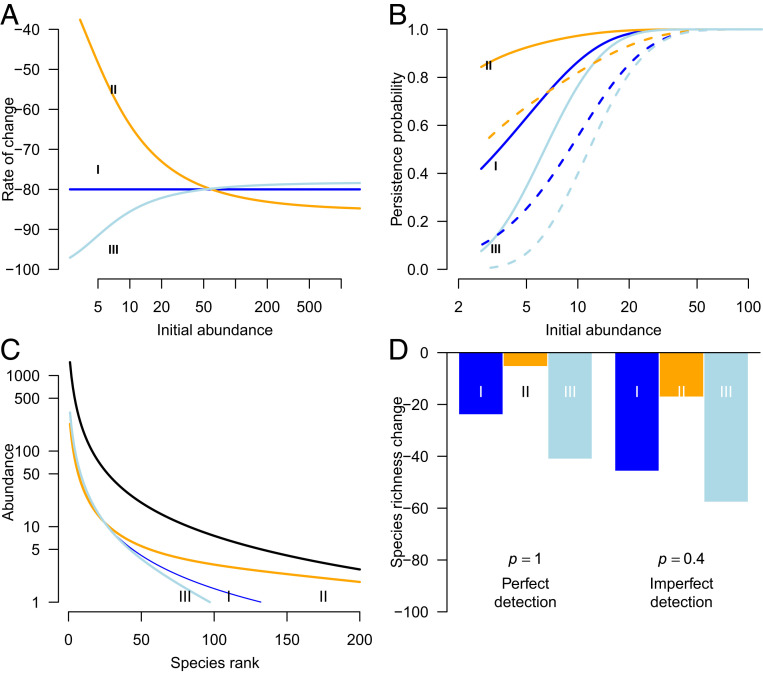

Fig. 1.

Theoretical exploration of the meaning of 80% total abundance loss for the persistence, abundance, and loss of the species that make up a community. (A) Three different scenarios of how the rate of decline is distributed across the gradient of common to rare species, while maintaining an overall loss of 80% (I, equal decline rates between species; II, higher decline rates for abundant species; and III, higher decline rates for rare species). (B) Persistence probabilities for each scenario assuming perfect ( = 100%; solid lines) and imperfect ( = 40%; dashed lines) sampling efficiency. (C) Rank abundance curves for the initial population (thick black line) and for each of the scenarios of decline. (D) Fraction of species lost in each scenario under perfect ( = 100%) and imperfect ( = 40%) sampling efficiency.

In all three scenarios, rare species have lower persistence rates than common species (Fig. 1B). Observed persistence appears even less when assuming imperfect detection (here arbitrarily at 40%; Fig. 1B). The species rank-abundance distributions are affected as well (Fig. 1C), but this is particularly evident for high-ranking (i.e., less common) species. For a given total abundance loss, the strongest declines in the number of species are to be expected under scenario III. In all scenarios, observed species losses are greater when detection is imperfect compared to when all available insects are trapped (Fig. 1D). However, this does not affect the slope of the relationship between persistence rates and initial abundance and does not alter qualitatively the difference in persistence rates among the three scenarios. Furthermore, higher-order diversity measures (i.e., Hill numbers of order 1 and higher) (27, 36) respond differently to scenario II (higher decline rates of previously abundant species) than species richness (i.e., consistent with the Hill number of order 0): The higher-order Hill numbers increase over time under scenario II due to the increasing evenness among species, even though all species decline in abundance (SI Appendix, Fig. S1).

Empirical Results

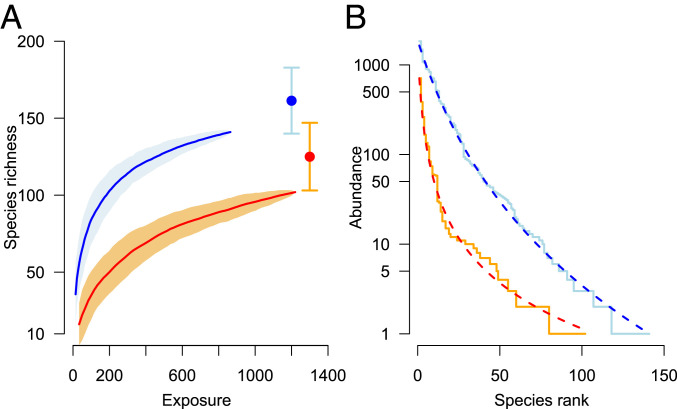

The total flying-insect biomass, number of hoverflies, and number of species of hoverflies were severely reduced in 2014 compared to 1989, despite the approximately 41% longer trap exposure time in 2014 (Table 1 and SI Appendix). Accounting for trap-exposure time only, 82% less insect biomass was trapped in 2014 than in 1989, as well as 89% fewer hoverfly individuals (Table 1). The overall species richness of hoverflies, as well as their accumulation pattern with increasing exposure time, indicated a lower richness in 2014 than in 1989 (Fig. 2A). Chao’s estimates of richness based on the accumulated species-abundance lists suggest 161.4 (SE = 10.9) hoverfly species were present in 1989 against 125.0 (SE = 11.2) in 2014, essentially a 23% decline in richness between the 2 y over a 25-y period. Similar losses in richness have been reported recently for various insect orders (2, 12), depending obviously on the spatial and temporal scales of inference. Furthermore, higher-order diversity measures (i.e., Hill numbers of orders 0 to 3, respectively species richness, Shannon diversity, Simpson diversity; and unnamed higher-order diversity measure in SI Appendix, Fig. S2) all declined, with increasing magnitude of decline with increasing order of Hill number (27, 36).

Table 1.

Summary of hoverfly data

| Trap no. | No. samples | Exposure time | No. species | No. individuals | Biomass | |||||

| 1989 | 2014 | 1989 | 2014 | 1989 | 2014 | 1989 | 2014 | 1989 | 2014 | |

| 1 | 20 | 13 | 140 | 216 | 96 | 52 | 2,084 | 394 | 949 | 416 |

| 2 | 20 | 12 | 140 | 182 | 86 | 28 | 3,222 | 122 | 1,508 | 223 |

| 3 | 21 | 13 | 146 | 216 | 73 | 56 | 2,005 | 516 | 898 | 240 |

| 4 | 21 | 13 | 146 | 216 | 95 | 66 | 4,091 | 417 | 1,429 | 423 |

| 5 | 21 | 12 | 146 | 184 | 75 | 45 | 3,504 | 953 | 1,020 | 178 |

| 6 | 20 | 10 | 140 | 200 | 91 | 38 | 2,060 | 236 | 1,453 | 257 |

| 123 | 73 | 864 | 1,220 | 141 | 102 | 16,966 | 2,638 | 7,257 | 1,737 |

For each trap and year the number of samples, the total exposure time (in days), the total number of hoverfly species and individuals, and the biomass of all flying insects are given.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of species richness and species relative abundance between 1989 (blue) and 2014 (red) based on six malaise traps in each year. (A) Species accumulation curves along with 95% intervals based on 100 random permutations of original data (data pooled within year), against cumulative exposure time (number of trap-sampling days). Points depict Chao’s estimates of richness in each year along with 95% confidence intervals. (B) Rank abundance curves where solid lines depict data and dashed lines the fitted Zipf–Mandelbrot estimates.

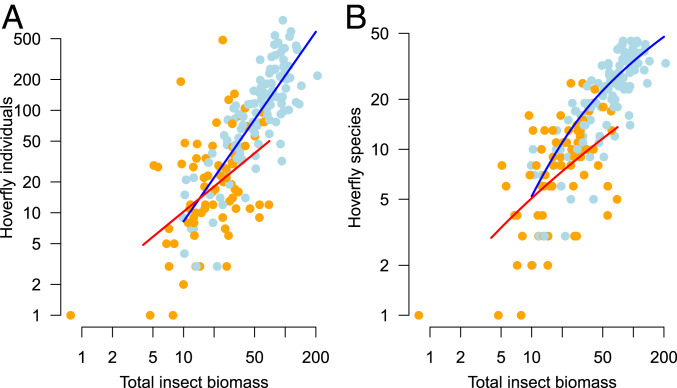

Even though hoverflies make up less than 5% of total insect biomass in the samples, we found that the total hoverfly abundance was significantly correlated with total flying-insect biomass, with abundance increasing linearly with larger biomass samples (on log-log scale; Fig. 3A). The relationship of the number of individuals to the total insect biomass changed from 1989 to 2014 in both intercept and slope (model with and without interaction; likelihood-ratio test, F = 6.5, P = 0.012, d.f. = 87, = 75.05%; Fig. 3A), showing that somewhat fewer hoverflies were trapped per gram of total insect biomass in 2014 than in 1989. We did not observe any significant difference in the distribution of log-body size of the trapped species between the 2 y (SI Appendix, Fig. S3), suggesting that it is unlikely that declines in biomass are a result of lighter species replacing heavier ones, at least within the group of hoverflies. Hoverfly species richness was nonlinearly related to biomass (Fig. 3B), with slightly diminishing increases in richness at larger biomass samples as a consequence of the nonlinearity of the species accumulation curve against cumulative exposure time (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 3.

(A and B) Relationships between total biomass of flying insects (grams per sample) and (A) number of hoverfly individuals and (B) number of hoverfly species. Blue and orange points depict trap sample data of 1989 and 2014, respectively, while blue and red lines depict year-specific fitted relationships.

We developed a statistical model to increase the temporal resolution of our analyses and to incorporate sampling aspects (i.e., exposure length and spatial differences; Materials and Methods) and interpolated daily weather conditions (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). Using this model, we estimated a mean loss of 82.7% (CI: 82.0 to 83.5) in daily total hoverfly abundance = −1.756, SD = 0.028; SI Appendix, Fig. S5A and Table S1) and a decline of 81.2% (CI: 79.6 to 82.6) in hoverfly species richness per trapping day ( = −1.671, SD = 0.040 (SI Appendix, Fig. S5B and Table S2). Weather and trap effects were significant (SI Appendix, Tables S1 and S2), but did not affect the annual rate of decline in either response variable. These estimates indicate that at the daily level, declines in total insect biomass are paralleled by isometric declines in abundance and species richness. However, the strength of the correlation between total flying-insect biomass and species richness depends on the temporal scale of inference, with species richness declining much more on a daily basis (−82%) than total richness decline obtained from the seasonally accumulated samples (−23%). These results bear consequence for ecosystem functionality, for which arguably the daily activity and presence of hoverfly species are most relevant.

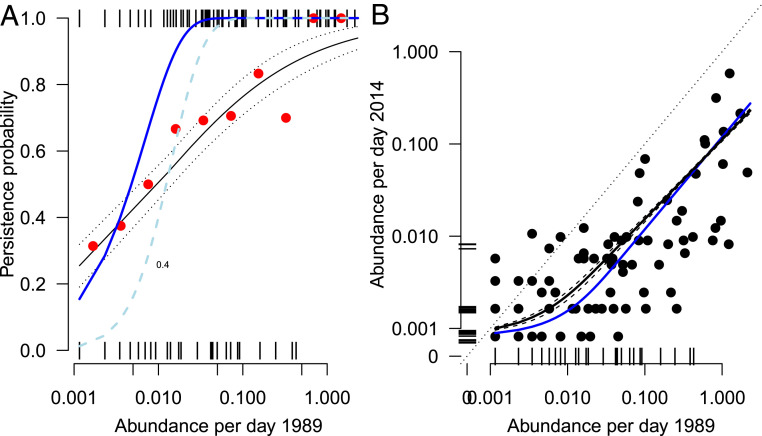

For the 141 hoverfly species caught in 1989, the probability of being caught again in 2014 increased linearly with log abundance in 1989 (Fig. 4A). The probability of presence in the 2014 trap data (given presence in 1989) was lower than expected under a null model with a uniform decline rate across species (i.e., scenario I in Fig. 1A), especially for the species that were relatively abundant in 1989. The observed extirpation rates are thus more consistent with a scenario in which common species have higher per capita decline rates than rare species (scenario II in Fig. 1A). Note the similarity of the lines of Fig. 4A with theoretical results in Fig. 1B: high decline rates of common species under imperfect detection (as not all flying insects will be trapped; orange dashed line) compared to the equal decline rate scenario and perfect detection (blue solid line).

Fig. 4.

(A) Probability of species persistence in the malaise trap data versus log abundance (n = 141). Red points depict average probabilities over 10 equidistant classes of abundance (for depiction purposes only), while the solid black line represents the fitted probabilities from a logistic regression (Eq. 13) along with 1 SE (dashed black lines). The blue line depicts the expected persistence probabilities calculated under a null model with uniform rate of decline across species (i.e., scenario I in Fig. 1), while the dashed light blue line represents expectations for observed persistence based on an arbitrarily chosen 40% sampling efficiency. (B) Population sizes in 2014 versus 1989. The solid black line depicts expected abundance (i.e., for species that are present in both years and for which a trend can be derived) along with 95% confidence levels (dashed black lines) in 2014 given abundance in 1989 as calculated from data (Eq. 17), while the solid blue line depicts the expected abundance in 2014 assuming a uniform rate of decline across species (i.e., scenario I in Fig. 1A).

Among species trapped in both years (n = 81), species abundances in 2014 appeared to have, on average, declined relatively less for rare than for common species, with a slope estimate of = 0.861 (SE) against log abundance in 1989 (Eq. 15 and Fig. 4B). Comparison with a model of equal decline rates between species (scenario I) also suggests that persistent rare species experience lower abundance decline rates (i.e., black line versus theoretical blue line in Fig. 4B), even though changes in abundance between the years differed considerably between species. Of the 24 most common species in 1989 (N 200 per 1,000 trap-sampling days), 3 were extirpated in 2014, while almost all remaining species were severely reduced in numbers (Table 2). In the group of rare species (between one and four individuals per 1,000 trap-sampling days), only 2 increased in abundance class, and 34 species (67%) of this group were not seen in 2014. However, 18 of the 21 new species in 2014 were in this rare species group (N 4; Table 2). Of the remaining group of species of intermediate abundance (66 species in 1989) a considerable number (n = 23) were no longer observed in 2014 and those that did reappear were considerably reduced in numbers.

Table 2.

Distribution of number of species per abundance-class category in 2014 and 1989

| 1989 | |||||

| Common | Intermediate 5 to | Rare 1 | Not | Total | |

| 200 (%) | 200 (%) | to 4 (%) | trapped (%) | trapped | |

| 2014 | |||||

| Common | 3 (12.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Intermediate | 16 (66.7) | 19 (28.8) | 2 (3.9) | 3 (14.3) | 37 |

| Rare | 2 (8.3) | 24 (36.4) | 15 (29.4) | 18 (85.7) | 41 |

| Not trapped | 3 (12.5) | 23 (34.8) | 34 (66.7) | 0 | |

| Total trapped | 24 | 66 | 51 |

Abundance classes are defined as rare, 1 to 4 individuals per 1,000 trapping days; intermediate, 5 to 200 individuals per 1,000 trapping days; and common, >200 individuals per 1,000 trapping days. Percentages in parentheses quantify the distribution of species column-wise.

Discussion

Biomass declines of total flying insects predict diversity declines in hoverflies, with numerical declines appearing across the full range of species. The highly time-demanding and logistically demanding effort required for taxonomic identification in insect communities forms a challenge in insect biodiversity studies such as the present one. Although nearly 20,000 specimens were identified to species level, only 2 y of data are available and utilized in the present study. Ecological processes that may affect our conclusions based on those 2 y, such as for example boom-and-burst dynamics of species with longer development cycles (observed for example in several beetle and cricket species) or mass-migration influx during autumn, are, however, not evident in our data and as such we do not expect such processes to have affected our results and conclusions. Our data, being representative for regional biomass distribution (SI Appendix, Fig. S6) and fitting in the 27-y trend of biomass decline across 63 different sites in Germany (1), suggest that our study sites are not exceptional and that these patterns are likely to be widespread.

Species persistence probabilities appeared lower than expected for species of intermediate abundance, where the expectation is drawn assuming a uniform rate of decline among species. Contrarily, for rare species, persistence probabilities are higher than expected under this same model, although maintaining lower persistence probabilities than more common species. Variation in species persistence probabilities thus appears to be most consistent with our hypothetical scenario II, in which the declining rates of common species are stronger than those of rare ones, while still resulting in an overall 80% drop in abundance and assuming imperfect sampling. Conditional on persistence, variation in the rate of decline between common and rare species (Fig. 4B) corroborates this result. The disproportionately high extirpation rate of intermediately common species in the empirical data did not match any of the model scenarios, which included only monotonically increasing or decreasing decline rates along the abundance axis. This difference likely caused the mismatch in the higher-order Hill number responses between empirical data and hypothetical scenarios (compare SI Appendix, Fig. S1, scenario II vs. SI Appendix, Fig. S2).

We conclude that large insect biomass reductions are thus disproportionately affected by the numerical declines of common species and by the extirpation of intermediately common species. The relative abundances of the hoverfly species in the malaise traps, even though only 2 y were analyzed, match the distribution and abundance of the species at the national scale (37) (SI Appendix, Fig. S7). As such, these results challenge our current understanding of population extinction processes, where stochastic variation pushes populations with the lowest numbers to disappear first (25, 26). While the mechanisms require additional research, it might be that previously common species are more heavily affected by reduced population sizes than expected because they are less adapted to deal with potential Allee effects (38) than already rare species or may be more dependent on intact metapopulations compared to naturally rare species (39, 40). Accordingly, the decline in most common species, and decline and disappearance of the intermediate species, contributed most to the drop in higher-order diversity indexes, as these indexes rely less on the response of rare species to community change (27). As such, the observed declines in rare, intermediate, and most common species differentially determined the responses in total abundance, species richness, and diversity.

In several recent studies, attempts have been made to convert numerical species and abundance loss into biomass loss (16, 19–21). By scaling with species average weight they show that abundance declines, species range contraction, or species loss may or may not be paralleled by their respective biomass loss (19–21). However, as these studies typically focus on the biomass of single insect taxonomic groups, they cannot reveal the true correspondence in declines between total insect biomass and species diversity. While abundance and biomass are proportional under spatial and temporal scaling, species richness is not (Fig. 3). Hence, sampling differences (and efficiency) between the various studies, e.g., whether or not monitoring occurs throughout the growing season, are likely to distort proportionality between declines in persistence and abundance and hence correspondence between biomass and diversity loss. In this study we demonstrate that under large biomass drops, species richness and diversity are inevitably reduced, particularly so when inferring at a small temporal scale (SI Appendix, Figs. S2 and S5).

As hoverflies are a relatively rich and diverse taxon (in terms of habitat requirements and functional groups), the observed declines across the species (mainly losers, essentially no winners) suggest that a common factor is responsible for the declines in hoverflies and possibly for other insect orders. While the variety of ecological functions is proportional to species richness (41–44), resource flows are mostly governed by the abundance of species (45–47), and hence we expect ecological functionality to be diminished in analogous proportions to abundance loss. Furthermore, the severe drop in both daily richness and daily abundance during the growing season suggests that both the diversity and quantity of the ecological functions that hoverflies perform (such as pollination and predation) will be jeopardized.

We conclude that an 80% insect biomass decline implies a disruption of the entire insect community, which constitutes a major part of the second trophic level in many ecosystems. Our results, with species of intermediate abundance (both locally and regionally; SI Appendix, Fig. S7) disproportionately in peril (Fig. 4A) and the most common species severely reduced in numbers (Figs. 2B and 4B), challenge current conservation efforts. Under the “umbrella species” paradigm, rare and specialized species and their habitats are prioritized in conservation strategies, from the notion that by doing this it will provide a safe haven for the more common and generalist species as well (40). To revert current trends in insect decline, this may be insufficient if current pressures on rare species are different from those on more common species. A holistic approach is required (48, 49) involving connecting and enlarging of nature reserves, together restoring basic ecological conditions, also for common species.

Materials and Methods

Data.

We utilize data obtained from six malaise traps in the Wahnbachtal (North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, N, E) that were deployed in 1989 and again in 2014, at the exact same locations. Traps were situated in wet meadows as well as tall perennial meadows, in close proximity to shrub corridors, to forest–grassland borders, and to the Wahnbach River and surrounded by agricultural land, essentially a rather heterogeneous habitat. The Wahnbach River and the greater part of the valley are protected for watershed purposes and are subject to nature conservation management by the Wahnbach Talperrenverband. Hence, several restrictions apply to safeguard against water contamination.

Total insect biomass collected with these traps was already included in ref. 1, but here we focus on additional information: the abundance and richness of hoverflies (Syrphidae) in each of the collected samples. Methodologies of collection are described in refs. 1 and 50–53. In brief, malaise traps were deployed throughout the growing season and operated continuously (day and night). Malaise trap construction (e.g., size, material, coloring, and ground sealing) and placing (e.g., positioning, orientation, and slope of the locations) were standardized in all aspects. Insect samples were preserved in 80% ethanol solution. Catches of the six traps investigated in the present study were emptied regularly: On average exposure intervals were 7.0 d (SD = 0.5) in 1989 and 16.7 d (SD = 5.6) in 2014. Across the six traps in 2014 the total exposure time (in number of days) was 42% higher compared to 1989. All collected samples (n = 196) were used in the present analysis with in total 19,604 individual hoverflies counted, distributed over 162 species and 59 genera. In Table 1 we further provide summary statistics relevant for sample size descriptions.

To assess how environmental conditions have changed over the 25 y, several additional datasets were assembled. Aerial photographs allowed us to investigate broad changes in the landscape surrounding the trap locations. Virtually no landscape changes were observed in this area, and hence we did not include landscape variables in our analysis. Furthermore, climatic data were obtained from 169 climatic stations and were used to interpolate daily weather variables to each trap location, using spatiotemporal kriging. These steps are described in ref. 1. Seasonal profiles of temperature, precipitation, and wind speed are given in SI Appendix, Fig. S3. Raw data and R code of the analysis are available in Zenodo (54).

Analysis Overview.

Our analysis consists of three components. First, we considered total abundance, species richness, and species diversity, at two temporal scales: pooled per year, i.e., across the sampling season, and seasonally (i.e., per day), and we compared these metrics between 1989 and 2014. Second, we examined how total flying biomass (i.e., the weight of all trapped insects, of which hoverflies are only a small proportion) related to total abundance as well as species richness of hoverflies. Third, we derived persistence probabilities and population growth rate trends per species, to examine interspecific variation in these parameters.

Pooled Species Richness and Diversity.

We pooled data across traps in each year and compared species richness and diversity between the two sampling years. Because of unequal sampling length between the 2 y (Table 1), we calculated the change in species richness between 1989 and 2014 using two methods. First, we used the Chao (55, 56) estimator for species richness, as it has been found to perform best among competing estimators (57),

| [3] |

where is the observed richness, the samples size, and the number of species with exactly detections, i.e., the number of singletons, the number of doubletons, and the (unobserved) number of species not detected. Second, changes in species richness between the two sampling years were also assessed by species accumulation curves against exposure time.

To better visualize how dominance and diversity changed between the 2 y, we fitted rank-abundance curves (58) to the hoverfly data. We initially considered five common distributions (broken stick, preemption, log-normal, Zipf, and Zipf–Mandelbrot) (59, 60) but for both datasets the Zipf–Mandelbrot distributions had a superior fit. We therefore report only results on the fitting of this rank distribution. The Zipf–Mandelbrot rank-abundance distribution is given by

| [4] |

where and parameters shape the decline in abundance with increasing species rank.

Finally, we compared the Hill numbers (27) of orders = 0 to 3 for the pooled data across the 2 y. Hill numbers conveniently express diversity with varying emphasis along the common to rare species axis, with higher-order estimates putting more weight on the common species compared to rare ones. Hill numbers are given by

| [5] |

where is the relative proportion of the th species in the sample, and the summation is taken over all species in the data. For , equals the species richness; for it corresponds to the exponent of the Shannon diversity index; for , corresponds to the inverse Simpson index; while for higher-order values of , diversity measures emphasize common species more over rare species (27).

Daily Activity Abundance, Species Richness, and Diversity.

We considered the total abundance (number of hoverfly individuals) and number of species at a finer temporal scale, in addition to the analysis integrating data across the sampling years. At this finer temporal scale of analysis, sampling and environmental effects are likely to be more pronounced than in the pooled analysis. For example, abundance is measured through the number of individuals trapped, which in turn depends on both trap (and sample) exposure length (longer intervals trap more insects) and the environmental conditions (e.g., weather) affecting the activity of species during the exposure period of a sample. Furthermore, contrary to abundance, species richness does not act additively with respect to exposure period length; i.e., we do not expect a monotonic increase in richness with sampling interval length, but rather a nonlinear increase approaching an asymptote akin to species–area relationships.

To allow comparison of abundance and species richness between the 2 y, we developed a model that accounts for environmental and sampling processes, by modeling the daily values of the response variable using a latent variable approach (1) and where sample expectations are aggregated over daily expectations of the corresponding exposure interval. Parameter estimates were obtained by fitting three parallel Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) chains using the Just Another Gibbs Sampler (JAGS) (61) and R (62) using 12,000 iterations, a burn-in period of 2,000 samples and a thinning interval of 10 samples to account for serial chain autocorrelation. Inference was thus based on 3,000 posterior samples for each parameter.

Total daily abundance.

Let be the total number of individuals observed in each sample , collected between day and , and let be its expectation under a Poisson process:

| [6] |

In turn, the expectation per sample is the sum of the (unobserved) daily expectations over the corresponding exposure interval

| [7] |

where is the latent number of individuals on a given day in sample , which in turn is modeled as a function of a number of covariates (Parameterization).

Observed and expected daily species richness.

Let be the proportion of the total abundance on day of the exposure interval of sample . Also let be the observed abundance of species in sample . Under the assumption that is invariant with respect to species, the expected abundance of each species in each day is given as the latent multinomial sample .

The number of species expected to have been trapped on day is then simply

| [8] |

where if and 0 otherwise. Next, to account for imperfect detection (not all species present on a particular day are likely to have been trapped), we relied on Chao’s estimator to derive the number of species expected to be present: . To this end, we tracked doubletons () and singletons () for each exposure day in the MCMC samples and computed the expected richness using Eq. 3.

Parameterization.

The daily expectations of total number of hoverfly individuals were modeled as a function of year, a seasonal component (day number , where 0 = January 1), weather effects (temperature, wind speed, and precipitation), and an effect for each trap (five contrasts),

| [9] |

where and , with representing each weather variable . Prior to analysis, weather and seasonal covariates were scaled to unit variance and zero mean.

Using the posterior estimates of expected daily richness (), we also derived the rate of decline in richness between the 2 y, while at the same time accounting for weather and sampling effects. To accomplish this, we used expected richness estimates as the response in a regression with Poisson error structure (allowing for overdispersion) and a log link:

| [10] |

This was performed for each of the MCMC iterations, and results were summarized over the posterior distributions of the coefficients.

Representativeness of the Sampled Years.

We compared within-year profiles of total flying-insect biomass between Wahnbachtal and all other sites analyzed in ref. 1 in the periods 1989 to 1992 and 2013 to 2015 (n = 15 and 29, respectively), which allowed us to infer how representative the six malaise traps included in this study are for the regional biomass distribution and trend (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). The years (1989 and 2014) in which the Wahnbachtal was sampled are at the beginning and toward the end of the study period analyzed in ref. 1, allowing easy comparison with the overall biomass declines reported in that study.

Abundance–Biomass Relationship.

To infer how total flying-insect biomass related to the abundance of hoverflies, we regressed the log of the number of individuals per sample against the log of the biomass per sample. We used simple linear regression with Gaussian error and with separate slope and intercept for each year and examined whether simpler models (for example a common slope across years) were more parsimonious:

| [11] |

where and are the intercept and slope coefficients relating abundance to biomass ().

We did not expect a linear relationship between biomass and hoverfly richness, but rather a curvilinear one, with the increase in species richness diminishing at large biomass quantities. To relate the number of species to total flying-insect biomass of a given sample, we used rarefaction theory (63). The number of species expected to be trapped in sample depends on the number of individuals trapped () total richness (S), and relative abundance of each species (). Additionally, it depends on the seasonal activity of each species, as not all species may be available to be trapped during each exposure period of each sample. The expected number of species in sample given total sample abundance is given by

| [12] |

which essentially represents sampling without replacement. The summation is taken over all species observed (, here across locations and years) and results in the rarefied richness from a total of individuals (ever counted across locations and years) to the total abundance of sample . Parameter represents the average species’ seasonal availability (SI Appendix). To produce the relationship between richness and biomass (Fig. 3), we replaced in Eq. 12 with the mean expectation of abundance given biomass from Eq. 11.

Persistence and Rates of Change by Species.

We examined variation in the persistence probabilities between species (i.e., the probability of a species being present in 2014, given its presence in 1989) as well as rate of change in abundance for all species present in both years (). Both response variables were subsequently contrasted against our theoretical results (Fig. 1).

To analyze persistence, we used generalized linear models (GLMs) with species presence in 2014 as a response, assuming a binary error distribution and a logit link, and with log(abundance 1989) as an explanatory variable:

| [13] |

The fitted logistic regression (based on observations) was compared to the expected persistence probability for each species under a uniform decline rate (i.e., scenario I in Fig. 1). The expected probability of persistence was derived using Eq. 1, where we defined the rate of decline in total abundance of species present in 1989 as

| [14] |

For species present in both years we modeled the abundance per species in 2014 by maximizing the likelihood of a zero-truncated Poisson distribution, with a log-link relationship to log(abundance in 1989):

| [15] |

Here too, we compared this observed species abundance to the expected abundance in 2014 under a uniform decline rate. Parameter measures the effect of initial abundance on rate of species decline: Value reflects scenario I, reflects scenario II, and reflects scenario III. Because zero observations are excluded in this analysis, we used a zero-truncated Poisson distribution to estimate and :

| [16] |

where is the expectation under a Poisson distribution. The expected abundance of each species in 2014 is given as . To integrate that only nonzero-integer values are observed, i.e., and , the expected abundance given initial abundance in 1989 is given as

| [17] |

which typically produces nonlinear curves, reflecting that only nonzero observation can be observed for low initial abundances (Fig. 4B).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We greatly acknowledge members of the Entomological Society Krefeld and cooperating botanists and entomologists that were involved in the investigations: K. Cölln, B. Franzen, M. Grigo, M. Hellenthal, J. Hembach, A. Hemmersbach, T. Hörren, J. Illmer, N. Mohr, S. Risch, O. and W. Schmitz, H. Schwan, R. Seliger, W. Stenmans, H. Sumser, and H. Wolf. For funding, C.A.H. and E.J. were supported by Dutch Research Council (NWO) Grants 840.11.001 and 841.11.007. The investigations of the Entomological Society Krefeld and its members are spread over numerous individual projects at different locations and in different years. Grants and permits that have made this work possible are as follows: F + E Biodiversitätsverluste in Fauna-Flora-Habitatrichtlinie–Lebensraumtypen (FFH-LRT) FFH-LRT des Offenlandes, gefördert durch das Bundesamt für Naturschutz mit Mitteln des Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz und nukleare Sicherheit (BMU), Bezirksregierung Köln, Bergischer Naturschutzverein, Rhein-Sieg Kreis, and Land Nordrhein-Westfalen–Europäische Gemeinschaft Europäischer Landschaftsfonds für die Entwicklung des ländlichen Raums (ELER).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. M.L.F. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2002554117/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability.

Dataset and R-code data have been deposited in Zenodo (54).

References

- 1.Hallmann C. A., et al. , More than 75 percent decline over 27 years in total flying insect biomass in protected areas. PLoS One 12, e0185809 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seibold S., et al. , Arthropod decline in grasslands and forests is associated with landscape-level drivers. Nature 574, 671–674 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nebel S., Mills A., McCracken J., Taylor P., Declines of aerial insectivores in North America follow a geographic gradient. Avian Conserv. Ecol. 5, 1 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hallmann C. A., Foppen R. P., van Turnhout C. A., de Kroon H., Jongejans E., Declines in insectivorous birds are associated with high neonicotinoid concentrations. Nature 511, 341–343 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.English P. A., Green D. J., Nocera J. J., Stable isotopes from museum specimens may provide evidence of long-term change in the trophic ecology of a migratory aerial insectivore. Front. Ecol. Environ. 6, 1–13 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biesmeijer J. C., et al. , Parallel declines in pollinators and insect-pollinated plants in Britain and The Netherlands. Science 313, 351–354 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Potts S. G., et al. , Global pollinator declines: Trends, impacts and drivers. Trends Ecol. Evol. 25, 345–353 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Potts S. G., et al. , “The assessment report of the intergovernmental science-policy platform on biodiversity and ecosystem services on pollinators, pollination and food production” (IPBES, Bonn, Germany, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Speight M. C., Saproxylic Invertebrates and their Conservation (Council of Europe, 1989). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leather S., “Ecological Armageddon”–more evidence for the drastic decline in insect numbers. Ann. Appl. Biol. 172, 1–3 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conrad K. F., Warren M. S., Fox R., Parsons M. S., Woiwod I. P., Rapid declines of common, widespread British moths provide evidence of an insect biodiversity crisis. Biol. Conserv. 132, 279–291 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dirzo R., et al. , Defaunation in the anthropocene. Science 345, 401–406 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fox R., et al. , Long-term changes to the frequency of occurrence of British moths are consistent with opposing and synergistic effects of climate and land-use changes. J. Appl. Ecol. 51, 949–957 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Habel J. C., et al. , Butterfly community shifts over two centuries. Conserv. Biol. 30, 754–762 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Habel J. C., Trusch R., Schmitt T., Ochse M., Ulrich W., Long-term large-scale decline in relative abundances of butterfly and burnet moth species across south-western Germany. Sci. Rep. 9, 1–9 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hallmann C. A., et al. , Declining abundance of beetles, moths and caddisflies in The Netherlands. Insect Conserv. Diver. 13, 127–139 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Strien A. J., van Swaay C. A., van Strien-van Liempt W. T., Poot M. J., WallisDeVries M. F., Over a century of data reveal more than 80% decline in butterflies in The Netherlands. Biol. Conserv. 234, 116–122 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stepanian P. M., et al. , Declines in an abundant aquatic insect, the burrowing mayfly, across major North American waterways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117, 2987–2992 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Homburg K., et al. , Where have all the beetles gone? Long-term study reveals carabid species decline in a nature reserve in Northern Germany. Insect Conserv. Diver. 12, 268–277 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Macgregor C. J., Williams J. H., Bell J. R., Thomas C. D., Moth biomass increases and decreases over 50 years in Britain. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 3, 1645–1649 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bell J. R., Blumgart D., Shortall C. R., Are insects declining and at what rate? An analysis of standardised, systematic catches of aphid and moth abundances across Great Britain. Ins. Conserv. Diver. 13, 115–126 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Klink R., et al. , Meta-analysis reveals declines in terrestrial but increases in freshwater insect abundances. Science 368, 417–420 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bowler D. E., Heldbjerg H., Fox A. D., de Jong M., Böhning-Gaese K., Long-term declines of European insectivorous bird populations and potential causes. Conserv. Biol. 33, 1120–1130 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Møler A., Parallel declines in abundance of insects and insectivorous birds in Denmark over 22 years. Ecol. Evol. 9, 6581–6587 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gilpin M. E., Soulé M., “Minimum viable populations: Processes of species extinction” in Conservation Biology: The Science of Scarcity and Diversity, Soulé M. E., Ed. (Sinauer, Sunderland, MA, 1986), pp. 19–34. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fagan W. F., Holmes E., Quantifying the extinction vortex. Ecol. Lett. 9, 51–60 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chao A., et al. , Rarefaction and extrapolation with Hill numbers: A framework for sampling and estimation in species diversity studies. Ecol. Monogr. 84, 45–67 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Larson B., Kevan P., Inouye D. W., Flies and flowers: Taxonomic diversity of anthophiles and pollinators. Can. Entomol. 133, 439–465 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ssymank A., Kearns C. A., Pape T., Thompson F. C., Pollinating flies (Diptera): A major contribution to plant diversity and agricultural production. Biodiversity 9, 86–89 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ssymank A., Hamm A., Vischer-Leopold M., Caring for Pollinators, Safeguarding Agro-Biodiversity and Wild Plant Diversity (BfN-Skripten, Bonn, Germany, 2009), vol. 250. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chambers R., Adams T., Quantification of the impact of hoverflies (Diptera: Syrphidae) on cereal aphids in winter wheat: An analysis of field populations. J. Appl. Ecol. 23, 895–904 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Colley M., Luna J., Relative attractiveness of potential beneficial insectary plants to aphidophagous hoverflies (Diptera: Syrphidae). Environ. Entomol. 29, 1054–1059 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rojo S., et al. , A World Review of Predatory Hoverflies (Diptera, Syrphidae: Syrphinae) and Their Prey (CIBIO, 2003). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sommaggio D., “Syrphidae: Can they be used as environmental bioindicators?” in Invertebrate Biodiversity as Bioindicators of Sustainable Landscapes, Paoletti M. G., Ed. (Elsevier, 1999), pp. 343–356. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Speight M., Castella E., Sarthou J., Monteil C. “(2013) Syrph the Net on CD. The Database of European Syrphidae” (Issue 9, Syrph the Net Publications, Dublin, Ireland, 2004). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hill M. O., Diversity and evenness: A unifying notation and its consequences. Ecology 54, 427–432 (1973). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ssymank A., Doczkal D., Rennwald K., Dziock F., Rote Liste und Gesamtartenliste der Schwebfliegen (Diptera: Syrphidae) Deutschlands. Rote Liste gefährdeter Tiere, Pflanzen und Pilze Deutschlands Band 3, Teil 1. Naturschutz Biologische Vielfalt 70, 13–83 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dennis B., Allee effects: Population growth, critical density, and the chance of extinction. Nat. Resour. Model. 3, 481–538 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thomas C. D., Dispersal and extinction in fragmented landscapes. Proc. R. Soc. B 267, 139–145 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Habel J. C., Schmitt T., Vanishing of the common species: Empty habitats and the role of genetic diversity. Biol. Conserv. 218, 211–216 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mouillot D., et al. , Rare species support vulnerable functions in high-diversity ecosystems. PLoS Biol. 11, e1001569 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jain M., et al. , The importance of rare species: A trait-based assessment of rare species contributions to functional diversity and possible ecosystem function in tall-grass prairies. Ecol. Evol. 4, 104–112 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oliver T. H., et al. , Biodiversity and resilience of ecosystem functions. Trends Ecol. Evol. 30, 673–684 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leitao R. P., et al. , Rare species contribute disproportionately to the functional structure of species assemblages. Proc. R. Soc. B 283, 20160084 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith M. D., Knapp A. K., Dominant species maintain ecosystem function with non-random species loss. Ecol. Lett. 6, 509–517 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gaston K. J., Fuller R. A., Commonness, population depletion and conservation biology. Trends Ecol. Evol. 23, 14–19 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Winfree R., Fox W. J., Williams N. M., Reilly J. R., Cariveau D. P., Abundance of common species, not species richness, drives delivery of a real-world ecosystem service. Ecol. Lett. 18, 626–635 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Harvey J. A., et al. , International scientists formulate a roadmap for insect conservation and recovery. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 4, 174–176 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Samways M. J., et al. , Solutions for humanity on how to conserve insects. Biol. Conserv. 242, 108427 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sorg M., Entomophage Insekten des Versuchsgutes Höfchen (BRD, Burscheid).- Teil 1. Aphidiinae (Hymenoptera, Braconidae). Pflanzenschutz-Nachrichten Bayer 43, 29–45 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schwan H., Sorg M., Stenmans W., Naturkundliche Untersuchungen zum Naturschutzgebiet ‘Die Spey’ (Stadt Krefeld, Kreis Neuss) - I. Untersuchungsstandorte und Methoden. Natur. Am. Niederrh. 8, 1–13 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sorg M., Schwan H., Stenmans W., Müller A., Ermittlung der Biomassen flugaktiver Insekten im Orbroicher Bruch mit Malaise Fallen in den Jahren 1989 und 2013. Mitteilungen Entomologischen Verein Krefeld 2013, 1–5 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ssymank A., et al. , Praktische Hinweise und Empfehlungen zur Anwendung von Malaisefallen für Insekten in der Biodiversitätserfassung und im Monitoring. Series Naturalis 1, 1–12 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hallmann C. A., et al. , Data and code from: Insect biomass decline scaled to species diversity: General patterns derived from a hoverfly community. Zenodo. 10.5281/zenodo.4298758. Deposited 30 November 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Chao A., Estimating the population size for capture-recapture data with unequal catchability. Biometrics 43, 783–791 (1987). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chiu C. H., Wang Y. T., Walther B. A., Chao A., An improved nonparametric lower bound of species richness via a modified Good–Turing frequency formula. Biometrics 70, 671–682 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Palmer M. W., The estimation of species richness by extrapolation. Ecology 71, 1195–1198 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Whittaker R. H., Dominance and diversity in plant communities. Science 147, 250–260 (1965). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wilson J. B., Methods for fitting dominance/diversity curves. J. Veg. Sci. 2, 35–46 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Oksanen J., et al. , vegan: Community ecology package (R package version 2.5-2, 2018).

- 61.Plummer M., “JAGS: A program for analysis of Bayesian graphical models using Gibbs sampling” in Proceedings of the 3rd International Workshop on Distributed Statistical Computing, Hornik K., et al., Eds. (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2003), vol. 124, pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 62.R Core Team , R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (Version 3.6.2, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hurlbert S. H., The nonconcept of species diversity: A critique and alternative parameters. Ecology 52, 577–586 (1971). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Dataset and R-code data have been deposited in Zenodo (54).