Abstract

Assessment of airway is recommended by every airway guideline to ensure safe airway management. Numerous unifactorial and multifactorial tests have been used for airway assessment over the years. However, there is none that can identify all the difficult airways. The reasons for the inadequacy of these methods of airway assessment might be their dependence on difficult to remember and apply mnemonics and scores, inability to identify all the variations from the “normal”, and their lack of stress on evaluating the non-patient factors. Airway Management Foundation (AMF) experts and members have been using a different approach, the AMF Approach, to overcome these problems inherent to most available models of airway assessment. This approach suggests a three-step model of airway assessment. The airway manager first makes the assessment of the patient through focused history, focused general examination, and focused airway assessment using the AMF “line of sight” method. The AMF “line of sight” method is a non-mnemonic, non-score-based method of airway assessment wherein the airway manager examines the airway along the line of sight as it moves over the airway and notes down all the variations from the normal. Assessment of non-patient factors follows next and finally there is assimilation of all the information to help identify the available, difficult, and impossible areas of the airway management. The AMF approach is not merely intubation centric but also focuses on all other methods of securing airway and maintaining oxygenation. Airway assessment in the presence of contagion like COVID-19 is also discussed.

Keywords: Airway assessment, airway management, COVID-19, line of sight, mnemonic, pandemic, paraoxygenation

Introduction

A thorough assessment of the airway is recommended by every airway guideline as the first step towards safe airway management.[1,2,3,4,5] Although, the definitions of the difficult airway are retrospective in nature,[1] the airway assessment is proposed so that the airway manager can identify the potentially difficult airway and make necessary preparations to deal with the difficulty. However, most of the guidelines and thus airway assessment methods are mainly intubation centric. Some of the guidelines include questions that need to be answered at the end of airway assessment[1,3] but almost none suggests any particular way to collate all these answers so as to make the assimilation simple.

Numerous ways of conducting airway assessment have been proposed that include many unifactorial and multifactorial tests and scores.[6,7,8,9,10,11,12] An approach based on assessing multiple airway features in an eleven-point table that follows the “line of sight” during conventional oral laryngoscopy is described in the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) guidelines.[1,13] Compared to any single test, multifactorial tests and a combination of multiple unifactorial tests alter both the sensitivity and specificity of detecting difficult airway, but the outcomes are variable.[14] However, none of the airway assessment methods can ensure detection of all difficult airway situations. Even a comprehensive, detailed airway assessment that prompts the operators to look at multiple airway risk factors and document the likely areas of difficulty did not result in a better prediction of the difficult airway when compared with the “regular” airway assessment.[15]

There is a need for a user-friendly and intuitive airway assessment model that allows quick and uniform assessment of multiple factors so as to identify most of the difficult airways. If an airway assessment tool could highlight the area(s) of difficulty and their probable amenability to optimization within the available resources, it would become even more wholesome.

Based on these needs, Airway Management Foundation (AMF) proposes a new approach to airway assessment, the AMF Approach. This approach offers a step ahead of the currently prevalent methods as it prompts the airway manager to view any difficult airway in the light of not only the patient factors but also the non-patient factors. It is not merely intubation centric but also focuses on all other methods of securing the airway and maintaining oxygenation. It promotes the thought process that supraglottic airway devices (SADs) are not merely rescue devices but first-line airway management devices as well. It replaces extubation with emergence; thereby further promoting the thought process that general anesthesia (GA) can be conducted successfully without intubation as well. The model is based on an organized “line of sight” method [Appendix I] and assessment cut-offs that are based on the known predictors [Appendix II] and added cut-offs keeping the newer devices and techniques in mind. The assessment findings categorize the areas of airway management as available, difficult, and impossible; difficult being optimizable as against impossible that is not optimizable. Optimizability is dependent on the available resources at the time when airway management is contemplated. The approach thus guides the airway manager in planning the airway management strategies. Finally, the AMF approach promotes the concept of over-diagnosing airway problems and making arrangements for them, rather than missing them and getting caught unawares. An outline of what is known and what is needed in airway assessment, and what makes the AMF approach unique is depicted in Table 1.

Table 1.

Outline of what is known and what is needed in airway assessment, and what AMF approach offers

| What is known |

| Most airway guidelines recommend thorough airway assessment before airway management to identify areas of difficulty. |

| Most guidelines and airway assessment methods are mainly intubation centric. |

| Numerous unifactorial and multifactorial tests and scores are described for airway assessment. |

| The ASA guidelines recommend eleven points along the “line of sight” to assess for difficult intubation. |

| The sensitivity and specificity of detecting difficult airway are different with different tests and their combinations. |

| None of the airway assessment methods can ensure detection of all difficult airway situations. |

| What is needed |

| An airway assessment model that allows the identification of most of the difficult airways. |

| An assessment tool that also identifies the possibility of optimization of the areas of difficulty. |

| What does the AMF Approach offer |

| It prompts the assessment of patient factors and nonpatient factors. |

| It focuses on all the methods of securing the airway and maintaining oxygenation and consequently floats the concept of emergence in place of extubation. |

| It uses the AMF “line of sight” method of focused airway assessment having modified cut-offs keeping the new devices and techniques in mind. |

| It introduces the concept of difficult and impossible areas of airway management; difficult being optimizable as against impossible that is not optimizable. |

| The approach guides the airway manager to plan airway management strategies. |

| It stresses on over-diagnosing airway problems and making arrangements accordingly. |

The AMF Approach

The AMF approach offers a unique roadmap to the airway manager to collect, tabulate, and process the information obtained during airway assessment. Since most airway assessment models only identify areas of difficulty in airway management, the AMF approach shall guide the airway manager about the management options for assessed difficulties simultaneously through its three-step approach:

Assessment of Patient

Assessment of Non-Patient Factors

Assimilation of All Assessments

Step I. Assessment of Patient

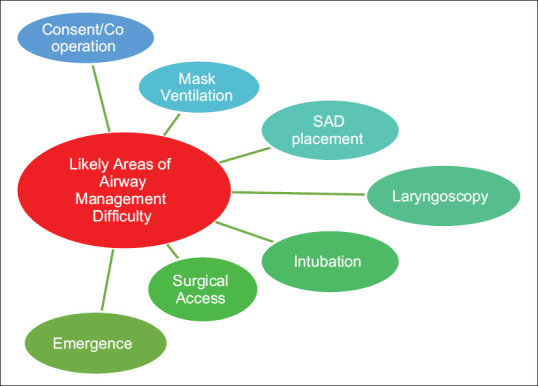

The AMF approach involves a simple and quick method to identify all the predictors of the problematic airway [Appendix II] that are present in a patient so that the likely areas of difficulty in airway management [Figure 1] can be pinpointed. It may be worth clarifying here that difficult intubation is a situation wherein laryngeal inlet is visible (i.e., laryngoscopy accomplished) yet an endotracheal tube will not pass or pass with considerable difficulty, into the trachea.

Figure 1.

Likely areas of difficulty during airway management

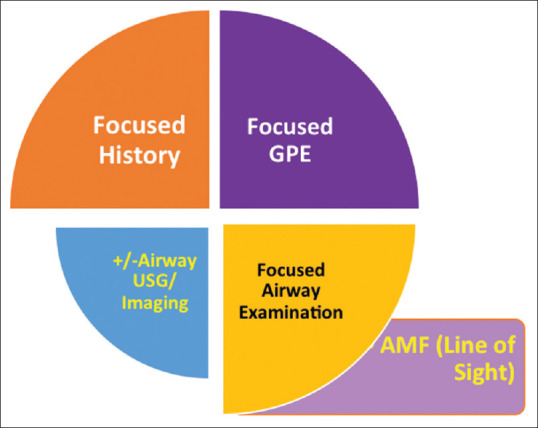

The assessment of the patient consists of mainly three steps. The fourth step of airway ultrasonography (USG) or imaging—although useful—may not be always needed [Figure 2]:

Figure 2.

Components of Assessment of Patient; Clockwise from Top Left. (GPEgeneral physical examination; USG-ultrasonography; AMF-Airway management foundation).

Focused History: history focused on detecting conditions that can have effect on airway management (diabetes mellitus, ankylosing spondylitis, rheumatoid arthritis, etc.).

Focused general physical examination (GPE): general examination focused to detect findings that can impact airway management, including considerations because of the specific patient condition (pregnancy/labor, obesity, age, etc.).

Focused Airway Examination using the AMF “Line of Sight” (LOS) Method: this approach recommends looking at multiple features along the line of sight moving systematically along the airway from parts of face and mouth to the neck.

Airway USG or other Imaging – only when needed.

The findings of all the steps of the Assessment of Patients are tabulated as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Suggested Method of Assessment of Patient, Including the AMF “Line of Sight” (LOS) Method for Focused Airway Examination. (References in Appendix II)

| Focused History | Variation | Area of Possible difficulty |

|---|---|---|

| Mental status, Hearing/speech, Level of apprehension, Consent | Mentally challenged, Hearing/speech impaired, Apprehensive, Refusal | Consent and Cooperation |

| Snoring | Present | MV |

| Previous Airway Event | Present | As per the event |

| Known supra-glottic/glottic/sub-glottic obstruction | Present | MV, SAD, Intubation |

| Neck irradiation | Present | MV, Lx |

| Tobacco/Gutka Chewer | Present | SAD, Lx |

| Cervical spine trauma/surgery | Present | Lx |

| Diabetes, Ankylosing spondylitis, Rheumatoid arthritis | Present | MV, Lx |

| Focused General Examination | Variation | Area of Possible Difficulty |

| Age | > 45 years; >55 years | SAD; MV |

| Gender | Male | SAD; MV |

| BMI (Obesity) | BMI >30 kg/m2 | MV; Lx; Surgical access |

| Gait | Stiff | Lx |

| Voice | Hoarse | MV; SAD; Intubation |

| Hyponasality | MV; Nasal intubation | |

| Pregnancy | Advanced pregnancy | Lx; Intubation |

| Active labor | ||

| Prayer sign | Positive | Lx |

| Focused Airway Examination: Line of Sight (LOS) method | Variation | Area of Possible difficulty |

| Nose | Deformed, Narrow nares/nasal passage, Blocked nostril(s) | Nasal Intubation |

| Bilateral blocked nostrils | MV | |

| Malar Region, Cheeks | Deformed, Masses, Flowing beard | MV |

| Mouth | Deformed | MV |

| Microstomia | SAD, Lx | |

| Teeth | Edentulous | MV |

| Missing, bucked, loose irregular, overbite, removable false denture | Lx | |

| IIG <3 cm | Lx | |

| IIG <2 cm | SAD | |

| Oral Cavity | MMP >2 | MV, Lx |

| High arched, narrow, or cleft palate | SAD, Lx | |

| Space occupying masses | MV, SAD, Lx | |

| Lower Jaw | Receding, prognathic | Lx |

| Injury, Mass | MV | |

| Lower jaw subluxation | ULBT Class 3 or ULCT Class >II/III | MV, Lx |

| Mandibular space | TMD <6.5 cm | MV, SAD, Lx |

| Poor compliance, scarring | MV, Lx | |

| Neck swelling, deformity, gross tracheal deviation | Present | Intubation, Surgical access |

| Cricothyroid membrane | Impalpable | Surgical access |

| Neck Length | SMD <12.5 cm | Lx, Surgical access |

| Neck Circumference | >40 cm (F)/>42 cm (M) | Lx, MV |

| Head-Neck ROM | <90° | MV, Lx, Surgical access |

Airway USG or other Imaging - These are indicated only in cases where the Assessment of Patient by the above method suggests the possible involvement of area(s) that could not be accessed/visualized through the clinical assessment alone. However, some airway managers use USG routinely during some airway assessments, e.g., while planning for extubation or to mark the cricothyroid membrane before planned or emergency front of neck access. BMI-body mass index; MV-mask ventilation; SAD-supraglottic airway device; Intubn-intubation; Lx-laryngoscopy; IIG-inter-incisor gap; ULBT-upper lip bite test; ULCT-upper lip catch test; MMP-modified Mallampati class; TMD-thyromental distance; SMD-sternomental distance

STEP-II. Assessment of Non-Patient Factors

After tabulating the patient factors, the AMF Approach prompts the airway manager to focus his attention on non-patient factors that may have a significant effect on airway management. Assessment of non-patient factors consists of the assessment of resources, surgical requirements, and airway manager's mindset:

-

Resources – Assessment of resources is crucial to plan airway management in any location. This consists of:

- Assessment of manpower – Manpower not only means extra hands but also people with more knowledge and skills.

- Assessment of fallback capabilities – Fallback capabilities mean availability of ICU or higher referral center if needed.

-

Assessment of available equipment including paraoxygenation equipment.

- Equipment – a lot of optimization is dependent on the equipment that is available [Table 3].

- Paraoxygenation is the broad term used by AMF for various methods of providing O2 during the attempts to secure the airway. It includes (but is not limited to) – (a) use of nasal prongs with O2 flows up to 10–15 Lpm [attached to either common gas outlet (of older anesthesia workstations) or to auxiliary O2 outlet of newer ones], also called nasal oxygenation during efforts of securing a tube (NODESAT)[2,16], (b) high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC)[17], or (c) transnasal humidified rapid insufflation ventilatory exchange (THRIVE).[18]

- Surgical Requirements – Airway management is best tailored to meet the surgical requirements, if safely possible. Changes in airway management plan may be necessitated by patient positioning, sharing of the airway with the surgeon, surgical technique (e.g., robotic surgery, laser surgery), etc.

- Airway manager's mindset – Some airway situations can be managed in more than one ways, and the final method of management is guided by the mindset of the airway manager in charge. The same is true regarding the decision to continue with an SAD after it has been used to secure the airway in an emergency of intubation failure.

Table 3.

The AMF Suggested Method of Assimilation of Assessments to Aid Airway Management Planning

| Areas | Available, Difficult or Impossible? | Optimization needed for Difficult (some examples) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cooperation | A/D/I | Attendants/Medication* | ||

| Mask ventilation | A/D/I | OPA, NPA, Case specific† | ||

| SAD placement | A/D/I | 2nd generation SAD, Preshaped SADs, Laryngoscope, Bougie‡ | ||

| Laryngoscopy | A/D/I | OELM, other blades (e.g., McCoy blade), Videolaryngoscope, Fiberscope, Case specific§ | ||

| Intubation | A/D/I | Stylet, Bougie, Magill forceps, Cuff inflation,[19] Case specific║ | ||

| Front of neck access | A/D/I | Bandage removal, Scar incision, Ultrasound-guided | ||

| Emergence | A/D/I | Fully awake, Bailey’s maneuver,[20] AEC¶ | ||

| Resources | Available? | |||

| Equipment | Yes/No | |||

| Knowledge and Skills | Yes/No | |||

| Extra hand | Yes/No | |||

| Paraoxygenation** | Yes/No | |||

| Fall back capabilities†† | Yes/No | |||

| Surgical requirement | Possible? | |||

| Special patient position | Yes/No | Yes/No | ||

| Airway shared | Yes/No | Yes/No | ||

| Airway manager’s mindset | Possible? | |||

| Is intubation MUST? | Yes/No | Yes/No | ||

| Can SAD be the definitive airway device? | Yes/No | Yes/No | ||

* - Attendant is allowed inside the operation theater to comfort the patient (for children or patients with a handicap (mentally or physically challenged); very small (¼ to ½ of the usual) dose of anxiolytic may be considered. †e.g., cling film for beard, gauze pieces to puff out cheeks, ramping for obese, etc., OPA-oropharyngeal airway, NPA-nasopharyngeal airway. ‡Bougie-guided introduction requires gentle pharyngoscopy as well.[21]. § - e.g., gauze pack for missing incisors or cleft palate, ramping for obese, etc., OELM-optimum external laryngeal manipulation. ║e.g., gauze pack for missing incisors or cleft palate. ¶In addition to these optimization options that suggest that the airway device will be removed on the table itself, the airway manager can either defer the removal of the airway device till the airway and patient have stabilized or perform tracheostomy before removal of the airway device. AEC - airway exchange catheter. **e.g., Nasal prong, Auxiliary O2 flow, High flow nasal cannula (HFNC)/ Transnasal humidified rapid insufflation ventilatory exchange (THRIVE). Please remember that paraoxygenation may be difficult or impossible in the presence of blocked bilateral nasal passages, while attempting nasal intubation in the presence of large oral swelling and in the presence of large laryngeal or tracheal swelling/foreign body. ††e.g., ICU or a higher referral center

STEP III. Assimilation of All Assessments

The third step of the AMF Approach is the assimilation of the findings of the assessment of the patient and those of the assessment of non-patient factors. AMF proposes to conduct this process of assimilation through a standardized method as shown in Table 3.

Once the boxes in Table 3 are filled, the airway manager is lead to clear-cut available (A), difficult (D), and impossible (I) areas of airway management, viewed in the light of not only the airway assessment findings but also those of assessment of available resources, surgical requirements, and airway manager's mindset.

An area or component of airway management is considered “impossible” when it is, or is likely to be, not optimizable within the available resources.

On the other hand, a component of airway management is labeled as “difficult” if it is considered optimizable within the available resources. The optimization skills and techniques are well known, but the important ones are included in Table 3 to make the AMF Approach and the recommendations more useful and complete.

The possibility of maintaining oxygenation during the process of airway access forms an important component of assimilation and decision-making.

This final step of assimilation paves way for a safe airway management plan for the patient and in the situation in question. Three points need to be made here: (i) with the patient's safety being the top priority, even slight doubt about the optimizability of any component should be enough to label it “impossible” and; (ii) same findings in assessment may be called “difficult” under some circumstances and “impossible” under other circumstances (depending upon available resources) or vice-versa; and finally, (iii) the AMF assimilation process promotes the concept that if used properly, SADs should be considered as definitive airway devices in many more cases than at present.

Using the AMF Approach

Let us apply the AMF Approach in a test case. A healthy 20-yr-boy with post-traumatic bilateral temporomandibular joint (TMJ) ankylosis is posted for bilateral TMJ release. There is no significant history other than a fall on the chin 5 years ago followed by gradually increasing difficulty in mouth opening. His assessment is shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Assessment of the Test Patient

| Focused History | Variation | Area of Possible Difficulty |

|---|---|---|

| Snoring | Present | MV |

| Focused General Examination | Variation | Area of Possible Difficulty |

| All factors | None | None |

| Focused Airway Examination: Line of Sight (LOS) Method | Variation | Area of Possible Difficulty |

| Nose | None* | None* |

| Malar Region, Cheeks | None | None |

| Mouth | None | None |

| Teeth | IIG=0.4 cm* | SAD, Lx* |

| Oral Cavity | Can’t be assessed* | No comments* |

| Lower Jaw | Receding* | MV, Lx* |

| Lower jaw subluxation | ULBT Class 3* | MV, Lx* |

| Mandibular space | None | None |

| Neck swelling, deformity, tracheal deviation | None | None |

| Cricothyroid membrane | None | None |

| Neck Length, Circumference, ROM | None | None |

*Features relevant to this case

As far as non-patient factors are concerned, the patient is in a tertiary care center with all the resources. The surgical team is fine with both oral and nasal routes but will keep the face turned to one side for the initial half and then turn it to the other side. Let us now tick the boxes of the assimilation table for this patient as shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Assimilation of Assessments of the Test Patient

| Areas | Available/Difficult/Impossible | Optimization needed | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cooperation | Available | None | ||

| Mask ventilation | Difficult | Head tilt, NPA | ||

| SAD placement | Impossible | None | ||

| Laryngoscopy | Difficult (direct laryngoscopy impossible but nasal fiberscope-guided laryngoscopy possible) | Flexible fiberscope guidance | ||

| Intubation | Available | As needed during fiberscopy; Blind nasal (±Et CO2 guidance, Cuff inflation technique) | ||

| Front of neck access | Available | None | ||

| Emergence | Available | None | ||

| Resources | Available? | |||

| Equipment (Flexible fiberscope) | Yes | |||

| Knowledge and Skills | Yes | |||

| Extra hand | Yes | |||

| Paraoxygenation | Yes | |||

| Fall back capabilities | Yes | |||

| Surgical requirement | Possible? | |||

| Special patient position | Yes | Yes | ||

| Airway shared | No | - | ||

| Airway manager’s mindset | Possible? | |||

| Is intubation MUST? | Yes | Yes | ||

| Can SAD be the definitive airway device? | No | No | ||

The airway manager now has a clear picture of all the factors (patient and nonpatient) to help him make airway management plan(s). If the same patient was in a center that did not have equipments and/or skills for flexible fiberscopy or if the patient was an uncooperative child, then the assimilation table would have looked different, leading to different management strategies.

Likely Outcome of AMF Approach

These AMF recommendations for Airway Assessment, through the described AMF Approach, have the potential to make airway assessment all-inclusive yet simple to remember and apply in day-to-day practice. If practiced and conducted regularly, the whole process takes less than 5 min. It is not claimed that using the method of assessment put forward in these recommendations will recognize and successfully resolve all problematic airways. However, the three-step AMF Approach is much more holistic than any available model.

The assessment and tabulation of Patient Factors [Table 2] suggested in these recommendations lead to the likely problematic areas. The non-mnemonic, non-scoring-based “line of sight” (LOS) method of focused airway assessment [Appendix I] makes assessment of the patient very easy to use because it is fully focused to find the predictors of difficulty [Appendix II] as these appear in the line of sight of the airway manager [Tables 2 and 4]. The next step of rating of the problematic areas detected during the patient assessment as ”available”, “difficult”, or ”impossible” in the light of all non-patient factors [Tables 3 and 5] provides a unique perspective to the airway manager to conduct much safer airway management than he would do otherwise. This is because while ticking the boxes in Table 3, the airway manager is compelled to think of optimization options available around him and arrange these before embarking on airway management [Table 5]. The usefulness of AMF Approach has been tested and approved by many AMF experts and members over the past nearly 10 years.

And finally, in the time of COVID-19 pandemic, a thought process needs to be nurtured wherein the airway manager is prepared to conduct airway assessment in a patient who is a potential carrier of a contagious infection that is spread by aerosol. This has been taken care of in Appendix IA, which suggests a modification of the AMF Approach under these circumstances.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

Our gratitude to Dr. Raminder Sehgal for being a part of the first attempt at simplification of airway assessment nearly 17 years ago.

Special thanks to AMF instructors who have been using, teaching, and enriching the AMF Approach for a long time (in alphabetical order): Dr. Akhil Agarwal, Dr. Anju Grewal, Dr. Bhavna Saxena, Dr. Kavita R Sharma, Dr. Manoj Bhardwaj, Dr. Manpreet Singh, Dr. Munisha Agarwal, Dr. Nishkarsh Gupta, Dr. Ranju Singh, and Dr. SD Sharma.

Thanks to a large pool of AMF instructors from various institutions from all over India for their constant support and feedback. Some noteworthy among these being (in alphabetical order): ABVIMS & Dr. RML Hospital Delhi, AIIMS Delhi, AIIMS Patna, ASCCMS Jammu, BSA Medical College & Hospital Delhi, DMCH Ludhiana, ESIC Hospital & PGIMSR Delhi, GMCH Amritsar, GMCH Chandigarh, Hindu Rao Hospital Delhi, LHMC Delhi, MAMC & Lok Nayak Hospital Delhi, Medanta Hospital Gurugram, PGI Chandigarh, PGIMS Rohtak, VMMC & Safdarjung Hospital Delhi, SGRD Medical College & Hospital Amritsar, Sir Ganga Ram Hospital Delhi, SPS Hospital Ludhiana, UCMS & GTB Hospital Delhi.

Thanks to All AMF members for their valuable inputs from time to time.

Appendix-I

The AMF “Line of Sight” Examination of Airway

Method of Focused Airway Assessment using the AMF Line of Sight (LOS) examination:

-

Equipment needed

- Torch

- Measuring tape

- Two scales (preferably 12 inches/30 cm)

- +/- cotton wisp or metal spatula

Position - Patient and operator sit face-to-face so that the operator's eyes are at the level of the patient's mouth.

-

Procedure – Having conducted the focused history and general physical examination and explaining the LOS examination, start scanning the patient from the forehead downwards along the airway.

- Look at the malar region, cheeks, and nose.

- Gently evert the tip of the nose and look inside the nostrils in the torchlight.

- Perform the test for nasal patency.

- Now, look at the lips and teeth.

- Ask the patient to open his mouth and measure the interincisor gap (IIG).

- Perform the modified Mallampati (MMP) test and also look at the palate. (Mallampati is the name of a scientist, so M is always capital)

- Examine the lower jaw next and perform the upper lip bite test (ULBT)/upper lip catch test (ULCT) as applicable.

- Feel the compliance of the submandibular region next and measure the thyromental distance (TMD).

- Examine the whole length of the neck.

- Identify the cricoid cartilage.

- Measure the neck length sternomental distance (SMD) and thickness (neck circumference).

- Finally come to the side of the patient (by asking the patient to turn by 90° to the right or left or by standing and coming to the side of the patient) and measure the neck range of motion (ROM).

-

Specific Tests that are part of the LOS examination

- Test for nasal patency: The patient is asked to keep his mouth closed. He is now asked to block one of his nostrils and gently breathe in and out through the other nostril. His breath is felt on the back of the operator's bare hand or forearm. The in-out movement of the breaths can be compared better by observing the difference in the back and forth movement of cotton wisp held near the patient's open nostril. Alternately, the patient is asked to gently breathe out on a metal spatula held 1 cm away from each nostril keeping the other nostril closed. The side where the area of fogging due to condensation of the moisture in the expired breath is 1 cm more in diameter than the other side is considered to be more patent.[22]

- Interincisor gap (IIG)[23] – With head in the neutral position, the patient is asked to open his mouth as wide as possible. A scale is held between the central incisors or the corresponding alveolar margins (in an edentulous patient) so that its length matches the length of the patient's face. The distance between the free margins of the central incisors/gums is the IIG.

-

Modified Mallampati class (MMP) (Mallampati classification[6] modified by Samsoon and Young*)[24] – With head in the neutral position, the patient is asked to open his mouth as wide as possible and put out his tongue without phonation. The operator illuminates the oral cavity and beyond with the help of a torch and looks for the fauces (the space between the tongue below and soft palate above through which at least some part of the posterior pharyngeal wall is visible), tonsillar pillars, uvula, soft palate, and hard palate and classifies these as follows:

- If all four (soft palate, fauces, uvula, pillars) are visible –MMP class I

- If soft palate, fauces, uvula visible – MMP Class II

- If soft palate (+/- base of uvula) – MMP Class III

- If the soft palate is not visible at all, only hard palate visible – MMP Class IV

-

Upper lip bite test (ULBT)[11] –The patient is asked to catch his upper lip with his lower teeth as high as possible. It is a good idea to demonstrate the same once. The ULBT is classified as:

- Class I if lower incisors can bite the upper lip above the vermilion line thereby hiding the mucosa of upper lip fully;

- Class II if lower incisors can bite the upper lip below the vermilion line thereby hiding only a part of the mucosa of upper lip; and

- Class III if lower incisors cannot bite the upper lip at all.

-

Upper lip catch test (ULCT)[25] – If the patient is edentulous, the patient tries to catch the upper lip with the lower lip. The findings are classified as:

- Class zero (0): The lower lip gliding or rolling over the upper lip reaching as high as the columella or else positioning itself at any point above midway between the vermilion line and the columella;

- Class I: The lower lip catching the upper lip, completely above the vermilion line fully covering and passing past the vermilion reaching a point midway between the vermilion and the columella;

- Class II: The lower lip catches the upper lip at the level of the vermillion line or positioning itself just above it (2 mm); and

- Class III: The lower lip just caresses the upper lip, but falls short of obliterating the vermillion line.

- Thyromental distance (TMD)[26] – The patient is asked to extend his head as much as possible with mouth closed and without moving the shoulders back. A scale is placed between the center of the chin above to the thyroid notch below. The straight distance between these two points is the thyromental distance. If using a flexible measuring tape, then the tape should be held taut between these two points to measure the TMD.

-

Identifying cricoid cartilage – Instead of using the popularly recommended ” laryngeal handshake” technique.[2] we prefer to use what AMF calls the “laryngeal finger slide” technique, which is as follows:

- The airway manager asks the patient to extend his head as much as possible and gently places his nondominant hand on the patient's forehead.

- With the thumb and middle finger of his dominant hand, he now holds the hyoid bone at the two ends (the two greater cornua).

- The index finger now identifies the middle part of the hyoid in the center of the patient's neck.

- The index finger in the midline is next slid down the midline as the thumb and the middle finger slide along the side of the larynx.

- The first prominence felt by the index finger as it slides down in the midline is the thyroid notch.

- As the finger in midline slowly slides down further, it meets a depression. This is the cricothyroid membrane.

- Sliding down further, the next hard structure felt in the midline is the cricoid cartilage. The thumb and middle finger should be on the cricoid cartilage at this time.

- Sternomental distance (SMD) (neck length)[8,27] – The patient is asked to extend his head as much as possible with mouth closed and without moving the shoulders back. A scale is placed between the center of the chin above to the center of the sternal notch below. The straight distance between these two points is the sternomental distance. If using a flexible measuring tape, then the tape should be held taut between these two points to measure the SMD.

- Neck circumference (neck thickness)[28] – The patient is asked to sit with his head in a neutral position. The neck circumference is measured at the level of thyroid notch using a measuring tape.

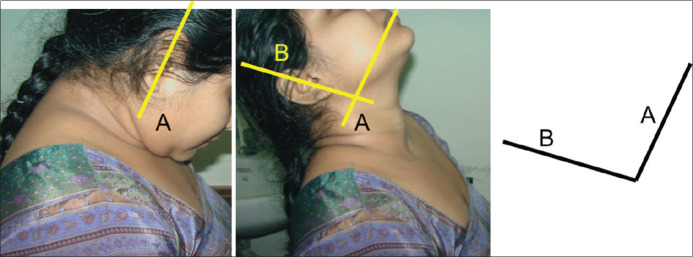

- Neck range of motion (ROM) [Figure 3] - Ask the patient to flex her neck as much as possible by bringing her chin down to touch her chest. Mark a point on the upper margin of her pinna and another one on the opposite (lower) margin of the ear on the ear lobule. Place the edge of one of the scales touching both these marked points. The lower margin of the scale can be rested on the soft tissue below to hold it securely in position. Holding the scale in this position, now ask the patient to slowly extend her neck as much as possible without moving the shoulders back. Place the edge of the other scale in such a manner that its edge touches both these marked points and also the edge of the first scale (the edge that was in contact with the marked points). The angle formed between the two scales now is the angle of neck range of motion (ROM).

Appendix – IA

Application of AMF Approach in Patients Suspected of Having Disease That is Highly Contagious Through Aerosols.

The world had never been devoid of infectious diseases that can spread through aerosols, be it open tuberculosis or HINI infection. But this pandemic of COVID -19 has taught us an important lesson, i.e., not to take things casually or for granted. The airway manager is likely to get exposed to aerosol from the patient for the first time during preanesthetic check-up (PAC) and airway assessment. It is only to be expected (and hoped) that all airway managers would now onwards meet all their patients for the first time (be it the formal PAC clinic or their chambers outside the OTs or elsewhere) wearing at least surgical gown, surgical cap, surgical mask, goggles, and gloves.

Modifications suggested for airway assessment

General preparation: Use Assessment Proformas wherever possible (online proforma are preferred over paper proforma). Use mike to make the communication with the patient easier across barriers.

Preparation for the assessor: Assessor should be wearing a surgical gown, surgical cap, N-95 mask, gloves, and a face shield in the correct manner.

-

Preparation for the patient: The patient should come wearing a mask (at least a surgical mask, if not N95) over her mouth and nose and maintain social distancing.

- Option 1: The patient should sit across a transparent plastic barrier with two openings for the assessor's hands and arms to pass. This may look a far-fetched idea but has the potential of becoming a norm if COVID-19 spills over into 2021, as some epidemiologists predict.

- Option 2: The patient should also be wearing a mask (at least a surgical mask, if not N95) over her mouth and nose and sit at least 1 m (3 feet) away from the assessor while focused history and general examination are underway.

The focused history should begin with a detailed history of any suspicious illness and/or contact (of the patient and all her contacts) in the past 2 weeks.

-

Conduct of LOS Examination: After eliciting focused history and conducting the focused general examination, explain the LOS examination to the patient.

- Additional tools – A camera phone with flash covered with a disposable polythene cover.

-

Steps –

- Counsel the patient and explain that she will be asked to perform certain maneuvers, which the assessor will demonstrate on himself. Also, tell her that photographs will be clicked to aid the assessment.

- Ask the patient to take off/pull down her mask.

- Click three photographs, one front and two side views (from either side).

- Demonstrate how to evert the tip of the nose. Now ask the patient to evert her nose gently. At this time click another picture from the front. The camera is zoomed to the nostrils with flash on at the time of clicking the picture.

- Now demonstrate how to perform the test for nasal patency. Hand over a cotton wisp to the patient and ask her to perform the test for nasal patency. Note the movement of the cotton wisp while the patient herself does the test. Ask her to dispose-off the wisp safely in a covered bin.

- Now examine the lips and teeth.

- Test for IIG should be conducted at the end as it involves the scale to be kept very close to patient's open mouth, almost touching her teeth or gums (if the patient is edentulous).

- For performing the MMP ask the patient to open her mouth fully and protrude the tongue. Take the lens of your camera phone in line with the oral cavity and about 1 foot away from her mouth. Click a picture with flash on. Now bring down the camera so that the hard palate is visible. Take another picture with flash on.

- Examine the lower jaw next and perform the ULBT/ULCT as applicable.

- Ask the patient to reapply the mask with the chin exposed.

- Feel the compliance of the submandibular region next and measure the TMD and SMD simultaneously with a 30 cm (1 foot) disposable cardboard/paper scale.

- Ask the patient to pull the mask over her chin as well.

- Examine the whole length of the neck.

- Identify the cricoid cartilage.

- Measure the neck thickness (neck circumference). If using a 30 cm disposable scale, place one edge of the scale on the thyroid notch, and gently bend the scale around one side of the neck. Place your finger at the point of contact of the other edge on the back of the patient's neck. Remove the scale and place it back so that edge on thyroid notch is now at the point that your finger was marking and gently wrap it around the patient's neck to reach the thyroid notch again. If the mark on thyroid notch is 6 cm then the neck circumference is a little over 36 cm (most scales have a few mm extra on either side of the beginning and end of markings).

- Ask the patient to turn by 90 ° to the right or left and ask her to flex her neck maximally and take a picture. Now ask the patient to extend the neck to the maximum without moving her shoulders back and take another picture.

- Finally, measure the IIG. Hand over the disposable scale to the patient. Demonstrate the measurement of IIG by using another scale. Ask her to open her mouth and place the scale as shown by you. Take a picture of the patient with a scale in position.

Dispose off the disposable scale and the camera phone cover safely and change your gloves once the airway assessment is complete.

Use the pictures to assess the malar region, nose, face, IIG, MMP, palate, and neck range of motion (NROM) [Figures 3 and 4].

-

NOTE:

- If using a reusable torch and measuring tape for assessment, these should be decontaminated appropriately before reusing.

- The assessor and the patient come in contact only during marking the cricoid cartilage, measuring the TMD, SMD, and neck circumference.

Figure 3.

The edge of the scale is placed on two points; one marked on the upper margin and another marked on the lower margin of the patient's pinna in extreme flexion (left picture) and the scale is held there (A). The patient is now asked to gently extend the neck as much as possible and the edge of the other scale is held such that it touches both the marked points (B) and that edge of the first scale that was touching these very points (A) (middle picture). The angle between those edges (A and B) of the two scales that were touching the two points is the neck range of motion (ROM) of this patient (right picture)

Figure 4.

(Clockwise from top left): Pictures showing how (i) malar region and face, (ii) nose, (iii) interincisor gap (IIG), (iv) modified Mallampati (MMP) class, and (v) palate can be assessed from properly taken photographs

Appendix - II

Known predictors6,7,13,27,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37

Over the years investigators have documented many predictors to identify areas that may cause difficulty in a particular patient.

-

Cooperation

- Age – children

- Mentally challenged

- Hearing/speech impaired

- Apprehensive

- Refusal

-

2.

Mask ventilation

- Stiff gait

- Male sex

- Age > 55

- BMI > 30 kg/m2

- H/o snoring

- H/o neck radiation

- H/o ankylosing spondylitis

- Hoarse voice

- Hyponasality in voice

- Facial asymmetry

- Beard

- Bilateral blocked nostrils

- No teeth

- Modified Mallampati (MMP) class > 2

- Restricted jaw movement (Upper lip bite test-ULBT II/III)

- TMD < 6.5 cm

- Thick neck (Neck circumference > 40/42 cm (F/M)

- Thyromental distance (TMD) < 6 cm

- Decreased neck range of motion (ROM)

- Upper airway obstruction

- Poor lung/chest compliance

-

3.

SAD

- Male gender

- Age > 45 years

- Microstomia

- Interincisor gap (IIG) < 2 cm

- Swelling in oral/pharyngeal area

- TMD < 6.5 cm

- Neck range of motion (ROM) < 90 °

- Glottic or infraglottic obstruction (suggestive symptoms and signs)

- Reduced chest compliance

-

4.

Laryngoscopy

- Stiff gait

- Advanced pregnancy and active labor

- H/o diabetes mellitus, ankylosing spondylitis, rheumatoid arthritis

- Prayer sign

- Microstomia

- Buck/Missing/Loose teeth

- Interincisor gap < 3 cm

- MMP > 2

- Intraoral growth

- High arched or cleft palate

- Restricted jaw movement (Upper lip bite test-ULBT II/III)

- Retro-/Micro-/Prognathia

- TMD < 6.5 cm

- Stiff, noncompliant submandibular region

- Sternomental distance (SMD) < 12.5 cm

- Neck circumference > 40 (F)/42 cm (M)

- ROM < 90 °

-

5.

Intubation

- Hoarse voice (Glottic or sub-glottic obstruction)

-

For nasal intubation

- ‒ Hypo-nasality

- ‒ Deformed, narrow nares/nasal passage, blocked nostril(s)

- Reduced IIG – (No space for laryngoscope (Lx) and endotracheal tube (ETT) together)

- Missing incisors – [Blade in the gap of missing teeth; Reduced space for ETT between teeth (canine, premolars, and molars)]

- High arched palate – narrow space for ETT

- Cleft palate – [Blade in the cleft; may cause injury and reduced space for ETT between teeth (canine, premolars, and molars)]

- Gross tracheal deviation

-

6.

Surgical access

-

Impalpable cricothyroid membrane (CTM)

- ‒ Thick scar over the site

- ‒ Neck swelling

- ‒ Morbid obesity

- Short neck

- Restricted neck extension

-

-

7.

Emergence

- Difficulty in airway access or in maintaining oxygenation still present at extubation or created intraoperatively

References

- 1.Apfelbaum JL, Hagberg CA, Caplan RA, Blitt CD, Connis RT, Nickinovich DG, et al. Practice guidelines for management of the difficult airway: An updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists task force on management of the difficult airway. Anesthesiology. 2013;118:251–70. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31827773b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frerk C, Mitchell VS, McNarry AF, Mendonca C, Bhagrath R, Patel A, et al. Difficult Airway Society 2015 guidelines for management of unanticipated difficult intubation in adults. Br J Anaesth. 2015;115:827–48. doi: 10.1093/bja/aev371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Law JA, Broemling N, Cooper RM, Drolet P, Duggan LV, Griesdale DE, et al. The difficult airway with recommendations for management-part 2-the anticipated difficult airway. Can J Anaesth. 2013;60:1119–38. doi: 10.1007/s12630-013-0020-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rehn M, Hyldmo PK, Magnusson V, Kurola J, Kongstad P, Rognås L, et al. Scandinavian SSAI clinical practice guideline on pre-hospital airway management. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2016;60:852–64. doi: 10.1111/aas.12746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Myatra SN, Shah A, Kundra P, Patwa A, Ramkumar V, Divatia JV, et al. All India Difficult Airway Association 2016 guidelines for the management of unanticipated difficult tracheal intubation in adults. Indian J Anaesth. 2016;60:885–98. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.195481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mallampati SR, Gatt SP, Gugino LD, Desai SP, Waraksa B, Freiberger D, et al. A clinical sign to predict difficult tracheal intubation: A prospective study. Can Anaesth Soc J. 1985;32:429–34. doi: 10.1007/BF03011357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson ME, Spiegelhalter D, Robertson JA, Lesser P. Predicting difficult intubation. Br J Anaesth. 1988;61:211–6. doi: 10.1093/bja/61.2.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al Ramadhani S, Mohamed LA, Rocke DA, Gouws E. Sternomental distance as the sole predictor of difficult laryngoscopy in obstetric anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 1996;77:312–6. doi: 10.1093/bja/77.3.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reed MJ, Dunn MJ, McKeown DW. Can an airway assessment score predict difficulty at intubation in the emergency department? Emerg Med J. 2005;22:99–102. doi: 10.1136/emj.2003.008771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khan ZH, Mohammadi M, Rasouli MR, Farrokhnia F, Khan RH. The diagnostic value of the upper lip bite test combined with sternomental distance, thyromental distance, and interincisor distance for prediction of easy laryngoscopy and intubation: A prospective study. Anesth Analg. 2009;109:822–4. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e3181af7f0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khan ZH, Kashfi A, Ebrahimkhani E. A comparison of the upper lip bite test (a simple new technique) with modified Mallampati classification in predicting difficulty in endotracheal intubation: A prospective blinded study. Anesth Analg. 2003;96:595–9. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200302000-00053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El-Ganzouri A, McCarthy RJ, Tuman KJ, Tanck EN, Ivankovich AD. Preoperative airway assessment: Predictive value of a multivariate risk index. Anesth Analg. 1996;82:1197–204. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199606000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Management of the Difficult Airway. Practice guidelines for management of the difficult airway: An updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Management of the Difficult Airway. Anesthesiology. 2003;98:1269–77. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200305000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Srinivasan C, Kuppuswamy B. Comparison of validity of airway assessment tests for predicting difficult intubation. Indian Anaesth Forum. 2017;18:63–8. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cattano D, Killoran PV, Iannucci D, Maddukuri V, Altamirano AV, Sridhar S, et al. Anticipation of the difficult airway: Preoperative airway assessment, an educational and quality improvement tool. Br J Anaesth. 2013;111:276–85. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levitan RM. NO DESAT! [Last accessed 2020 Jul 25]. Available from: https://epmonthly.com/article/nodesat .

- 17.Vourc’h M, Asfar P, Volteau C, Bachoumas K, Clavieras N, Egreteau P, et al. High-flow nasal cannula oxygen during endotracheal intubation in hypoxemic patients: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41:1538–48. doi: 10.1007/s00134-015-3796-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel A, Nouraei AR. Transnasal humidified rapid-insufflation ventilatory exchange (THRIVE): A physiological method of increasing apnoea time in patients with difficult airways. Anaesthesia. 2015;70:323–9. doi: 10.1111/anae.12923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar R, Gupta E, Kumar S, Sharma KR, Gupta NR. Cuff inflation-supplemented laryngoscope-guided nasal intubation: A comparison of three endotracheal tubes. Anesth Analg. 2013;116:619–24. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e31827e4d19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nair I, Bailey PM. Use of the laryngeal mask for airway maintenance following tracheal extubation. Anaesthesia. 1995;50:174–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1995.tb15104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brimacombe J, Keller C. Gum elastic bougie-guided insertion of the ProSeal laryngeal mask airway. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2004;32:681–4. doi: 10.1177/0310057X0403200514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thongrong C, Thaisiam P, Kasemsiri P. Validation of simple methods to select a suitable nostril for nasotracheal intubation. Anesthesiol Res Pract. 2018:4910653. doi: 10.1155/2018/4910653. doi: 10.1155/2018/4910653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crawley SM, Dalton AJ. Predicting the difficult airway. BJA Educ. 2015;15:253–7. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Samsoon GL, Young JR. Difficult tracheal intubation: A retrospective study. Anaesthesia. 1987;42:487–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1987.tb04039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khan ZH, Arbabi S, Yekaninejad MS, Khan RH. Application of the upper lip catch test for airway evaluation in edentulous patients: An observational study. Saudi J Anaesth. 2014;8:73–7. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.125942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patil VL, Stehling LC, Zaunder HL. Fiberoptic Endoscopy in Anesthesia. Chicago: Yearbook Medical Publishers; 1983. p. 79. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Savva D. Prediction of difficult tracheal intubation. Br J Anaesth. 1994;73:149–53. doi: 10.1093/bja/73.2.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gonzalez H, Minville V, Delanoue K, Mazerolles M, Concina D, Fourcade O. The importance of increased neck circumference to intubation difficulties in obese patients. Anesth Analg. 2008;106:1132–6. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e3181679659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Carvalho CC, da Silva DM, de Carvalho Junior DA, Santos Neto JM, Rio BR, Neto CN, et al. Pre-operative voice evaluation as a hypothetical predictor of difficult laryngoscopy. Anaesthesia. 2019;74:1147–52. doi: 10.1111/anae.14732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nichol HC, Zuck D. Difficult laryngoscopy: The “anterior” larynx and the atlanto-occipital joint. Br J Anaesth. 1983;55:141–4. doi: 10.1093/bja/55.2.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Langeron O, Masso E, Huraux C, Guggiari M, Bianchi A, Coriat P, et al. Prediction of difficult mask ventilation. Anesthesiology. 2000;92:1229–36. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200005000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kheterpal S, Healy D, Aziz MF, Shanks AM, Freundlich RE, Linton F, et al. Incidence, predictors, and outcome of difficult mask ventilation combined with difficult laryngoscopy: A report from the multicenter perioperative outcomes group. Anesthesiology. 2013;119:1360–9. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000435832.39353.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arne J, Descoins P, Fusciardi J, Ingrand P, Ferrier B, Boudigues D, et al. Preoperative assessment for difficult intubation in general and ENT surgery: Predictive value of a clinical multivariate risk index. Br J Anaesth. 1998;80:140–6. doi: 10.1093/bja/80.2.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hung O, Murphy M. Changing practice in airway management: Are we there yet? Can J Anaesth. 2004;51:963–8. doi: 10.1007/BF03018480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ramachandran SK, Mathis MR, Tremper KK, Shanks AM, Kheterpal S. Predictors and clinical outcomes from failed Laryngeal Mask Airway Unique™: A study of 15,795 patients. Anesthesiology. 2012;116:1217–26. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318255e6ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jun JH, Kim JH, Baik HJ, Kim YJ, Yun DG. Analysis of predictive factors for difficult ProSeal laryngeal mask airway insertion and suboptimal positioning. Anesth Pain Med. 2013;8:271–8. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saito T, Chew S, Liu W, Thinn K, Asai T, Ti L. A proposal for a new scoring system to predict difficult ventilation through a supraglottic airway. Br J Anaesth. 2016;117(Suppl_1):i83–6. doi: 10.1093/bja/aew191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]