Abstract

Background

Pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum) is a cereal crop that possesses the ability to withstand drought, salinity and high temperature stresses. The NAC [NAM (No Apical Meristem), ATAF1 (Arabidopsis thaliana Activation Factor 1), and CUC2 (Cup-shaped Cotyledon)] transcription factor family is one of the largest transcription factor families in plants. NAC family members are known to regulate plant growth and abiotic stress response. Currently, no reports are available on the functions of the NAC family in pearl millet.

Results

Our genome-wide analysis found 151 NAC transcription factor genes (PgNACs) in the pearl millet genome. Thirty-eight and 76 PgNACs were found to be segmental and dispersed duplicated respectively. Phylogenetic analysis divided these NAC transcription factors into 11 groups (A-K). Three PgNACs (− 073, − 29, and − 151) were found to be membrane-associated transcription factors. Seventeen other conserved motifs were found in PgNACs. Based on the similarity of PgNACs to NAC proteins in other species, the functions of PgNACs were predicted. In total, 88 microRNA target sites were predicted in 59 PgNACs. A previously performed transcriptome analysis suggests that the expression of 30 and 42 PgNACs are affected by salinity stress and drought stress, respectively. The expression of 36 randomly selected PgNACs were examined by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR. Many of these genes showed diverse salt- and drought-responsive expression patterns in roots and leaves. These results confirm that PgNACs are potentially involved in regulating abiotic stress tolerance in pearl millet.

Conclusion

The pearl millet genome contains 151 NAC transcription factor genes that can be classified into 11 groups. Many of these genes are either upregulated or downregulated by either salinity or drought stress and may therefore contribute to establishing stress tolerance in pearl millet.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12864-021-07382-y.

Keywords: Pearl millet, NAC, Transcription factor, microRNAs, Drought, Salinity

Background

Pearl millet [Pennisetum glaucum (L.) R. Br.] is the sixth most important staple food crop. It is a nutritionally superior crop for people living in arid and semi-arid regions of Sub-Saharan Africa and the Indian subcontinent. It can withstand harsh environmental conditions such as drought, salinity and high temperature [1]. Transcriptomic analyses has identified functional genes and pathways involved in pearl millets stress response [2–5]. The pearl millet genome has been sequenced by the International Pearl Millet Genome Sequencing Consortium [6]. The availability of pearl millet transcriptome and genome data helps to identify genes that contribute to stress tolerance in pearl millet. Among abiotic stresses, drought and salinity cause severe yield losses in major staple crops [7, 8]. Current climate prediction models forecast the deterioration of annual precipitation and an increase in salinization [9]. Breeding abiotic stress-tolerant crops such as pearl millet is therefore important to secure the food supply even under these conditions. To cope with these environmental stresses, plants activate defense responses, including the activation of sets of metabolic pathways and genes. Stress-responsive genes are classified into two types [10]: “functional” genes encoding proteins such as late embryogenesis-associated proteins, detoxification enzymes, heat shock proteins and molecular chaperones, which directly protect plants from abiotic stress, and “regulatory” genes encoding proteins such as protein kinases and transcription factors (TFs), which have roles in the perception and transduction of stress signals. TFs can interact with the promoter regions of gene and thereby alter gene expression patterns. Plant TFs are divided into different families [11]. Like many TFs, the NAC (NAM, ATAF1 and 2, and CUC2) family has versatile functions in plants [12]. The NAC domain was deduced from three previously characterized proteins, petunia NAM (no apical meristem), Arabidopsis thaliana ATAF1/2 (Arabidopsis thaliana activation factor 1/2) and CUC2 (cup-shaped cotyledon) [13, 14]. Previous studies in Arabidopsis, rice and wheat has demonstrated the involvement of NAC genes in abiotic stress responses [15–20]. A study in rice showed that, OsNAC2 plays a positive regulatory role in drought and salt tolerance in rice through ABA-mediated pathways [21]. In wheat, NAC transcription factor, TaNAC69 leads to enhanced tolerance to drought stress through increased expression of stress related genes [18]. Another rice NAC gene, OsNAC05 is responsible for root diameter enlargement and drought stress tolerance [22]. Overexpression of rice stress responsive NAC gene, SNAC1 improves drought and salt tolerance by enhancing root development and reducing transpiration rate in transgenic cotton [15]. All these study supports that NAC genes governs abiotic stress response of plants.

Genome-wide investigations of NAC transcription factor genes suggest that Arabidopsis thaliana has 117 NAC TFs, Setaria italica has 147 NAC TFs, Oryza sativa has 151 NAC TFs, and Zea mays has 152 NAC TFs [20, 23, 24]. However, NAC TF genes in pearl millet have not been analyzed thus far.

The objective of this study was to identify pearl millet NAC TFs and characterize their expression patterns. In this study, 151 NAC TF genes were identified in pearl millet (annotated as Pennisetum glaucum NAC genes; PgNACs). We have also analyzed their genomic distribution, phylogenetic relationships, gene structure, conserved motifs, microRNA targeting and expression profiles under drought and salinity-stress conditions.

Results

Identification and annotations of NAC genes in pearl millet

The HMMER Search with the HMM profile identified 151 NAC genes among 35,757 pearl millet genes. All the identified NAC genes were named by adding the prefix “Pg”, for Pennisetum glaucum, and were numbered according to their chromosomal position, yielding PgNAC001 to PgNAC151. Deduced PgNAC protein sequences exhibited a diverse range of amino acid lengths: the smallest PgNAC was 98 amino acids (PgNAC011) long, whereas the largest was 750 amino acids (PgNAC134) long (Additional File 2). The CDD search and the SMART program confirmed the presence of NAC domains in each PgNAC.

Chromosomal distribution, gene structure prediction and duplication analysis of PgNACs

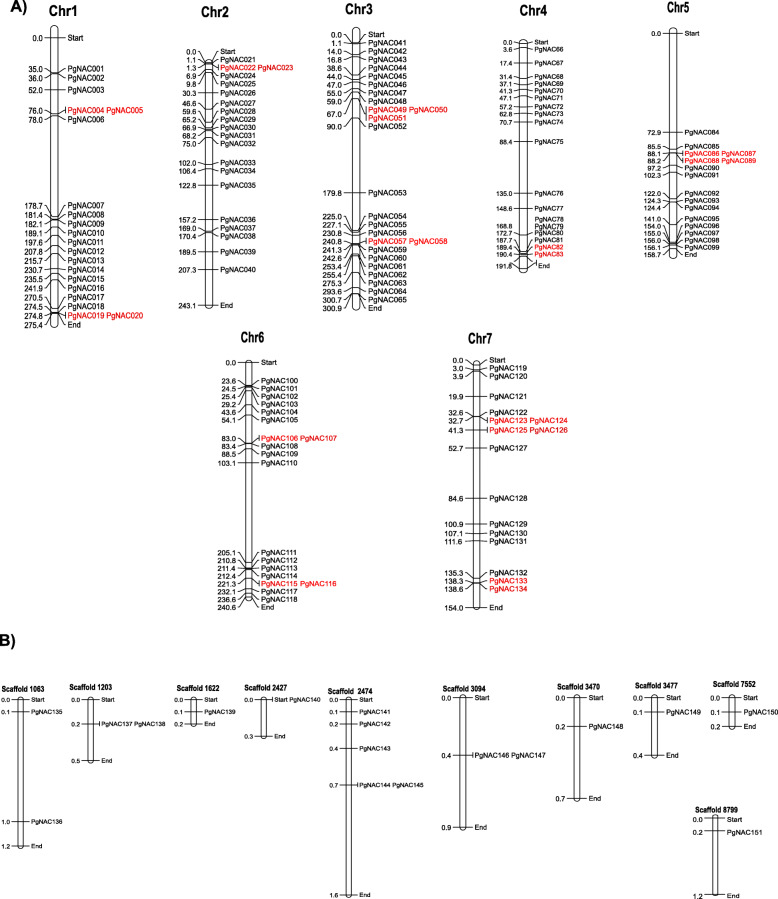

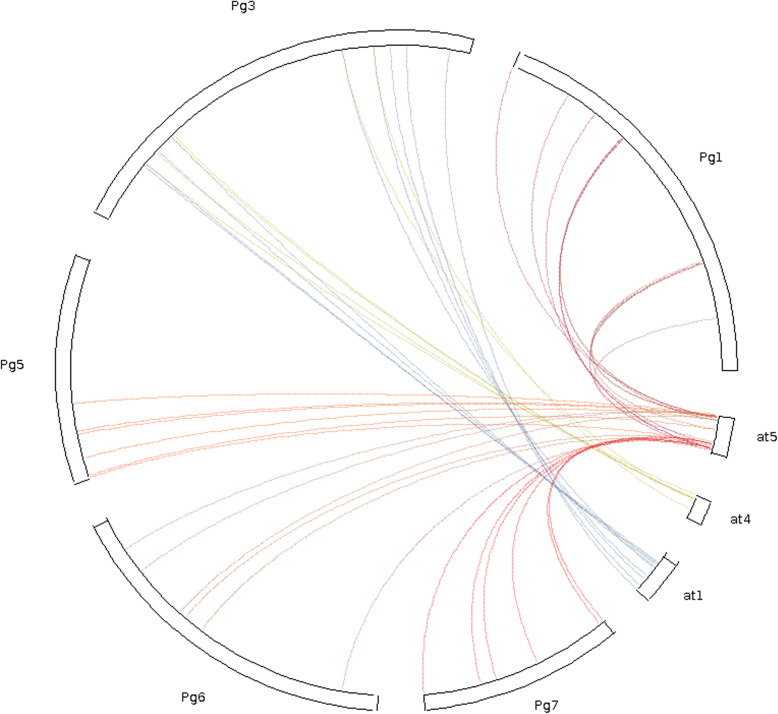

Physical mapping of PgNACs on all 7 pearl millet chromosomes revealed an uneven distribution for the first 134 PgNACs. Among the chromosomes, chromosome 3, which is the largest in size (300.9 Mb), had the largest number of PgNACs (25; 18%). Chromosomes 1 and 6 had the second largest number (15%) of PgNACs. Chromosome 5 had the smallest number (11%) of PgNACs, and its size is 158.7 Mb. PgNACs located on chromosomes 1 and 5 appear to congregate at one end of the arms, while chromosomes 2, 3, and 4 show clusters of PgNACs at both ends. Chromosome 7 has a non-clustered distribution of PgNACs. The remaining PgNACs (PgNAC135 to PgNAC151) mapped to 10 different scaffolds. Among these, scaffold 2474 had the largest number (5) of PgNACs (PgNAC141 to PgNAC145), while scaffolds 1622, 2427, 3470, 3477, 7552 and 8799 each had 1 PgNAC (Fig. 1). We further analyzed different types of duplication events of PgNAC genes. Among the 151 PgNAC genes 38 genes (25.17%) exhibited segmental and 76 genes (50.33%) exhibited dispersion duplication (Fig. 1 and Additional File 2). However, we didn’t find any tandem duplication in these PgNAC genes. To understand evolution and collinearity of NAC family between the species, we identified members of PgNAC family that are collinear with the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana. For the NAC family 32 collinear gene pairs were identified among pearl millet and Arabidopsis thaliana (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Positioning of PgNACs in the pearl millet genome. a Chromosome map showing the positions of PgNAC001–134 on chromosomes 1–7 in pearl millet. b Positions of PgNAC135–151 on scaffolds. Gene positions are shown in Mb. Duplicated PgNACs are shown in red

Fig. 2.

Collinearity analysis of NAC genes in pearl millet and Arabidopsis thaliana. The circle plot was created by MCScanX tool. Identified colinear genes were linked by the colored lines. Pg and at represent Pearl millet and Arabidopsis thaliana respectively

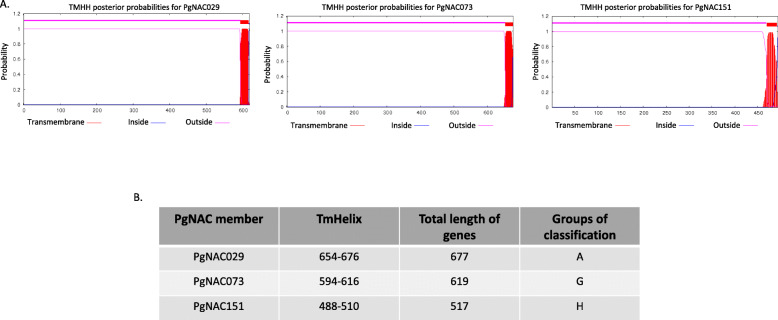

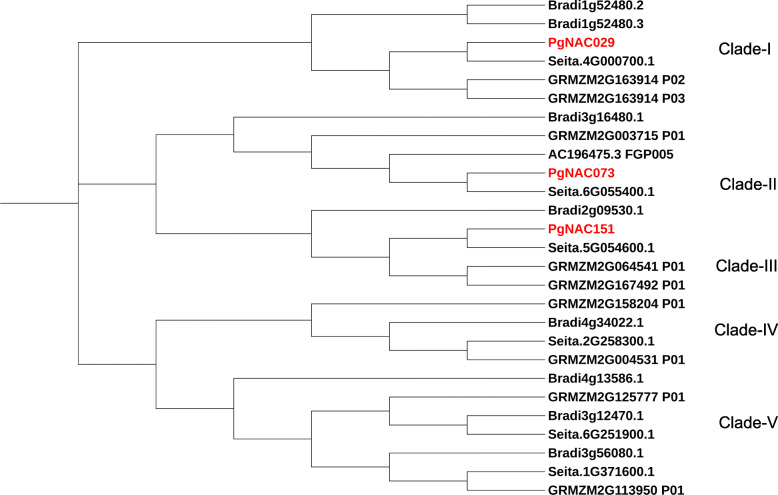

All PgNACs showed great variation in size, with the smallest gene being 0.5 kb and the longest being 9 kb. The number of introns in PgNACs ranged from zero to twelve. Thirty-eight PgNACs consist of three exons and two introns. PgNAC101 and PgNAC007 have 13 and 10 exons, respectively. Twenty-nine PgNACs have only one exon (Additional File 3). Three PgNACs (PgNAC073, PgNAC029, and PgNAC151) were predicted to have a single transmembrane helix at the N-terminus (Fig. 3). These three PgNACs are more like membrane-associated NAC proteins from Setaria italica, Brachypodium distachyon and Zea mays. Each membrane associated PgNAC was placed in a different NAC protein clade (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Analysis of PgNAC transmembrane helices. a Transmembrane regions in PgNAC073, PgNAC029, and PgNAC151. b Positions of the transmembrane helices in PgNAC073, PgNAC029, and PgNAC151, as well as their classification

Fig. 4.

Phylogenetic relationship among membrane-associated NAC TFs from pearl millet, Setaria italica, Brachypodium distachyon and maize. Multiple sequence alignment of all putative membrane-associated NAC TFs in pearl millet (proteins with “PgNAC” in their names), Setaria italica (proteins with “Seita”), Brachypodium distachyon (proteins with “Bradi”) and maize (proteins with “GRMZM”) was conducted using ClustalW. MEGA 7.0 was used to create phylogenetic trees using the neighbor-joining method with 1000 bootstrap replicates and the p distance method

Phylogenetic analysis of PgNACs and conservation of motifs

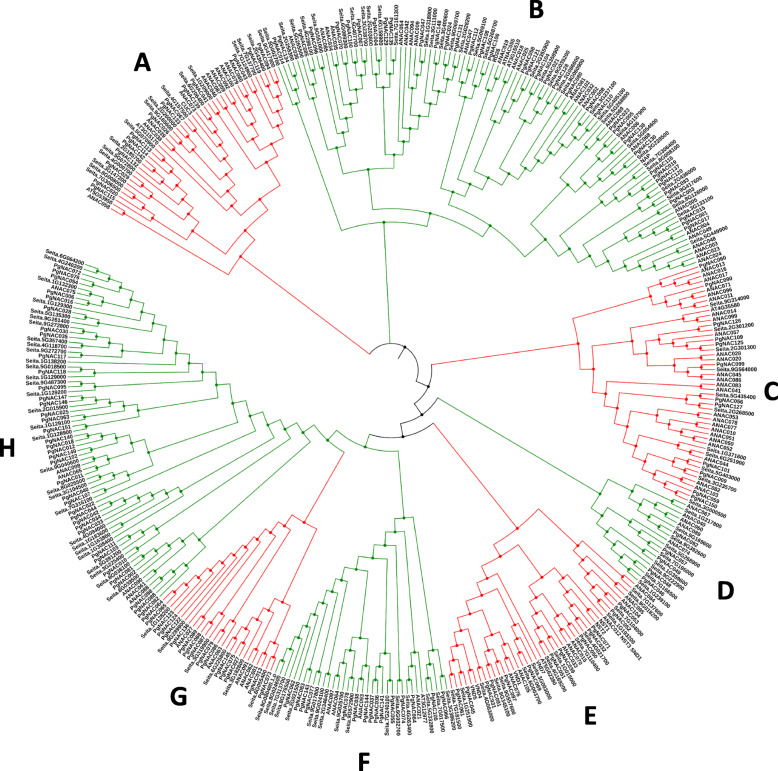

Comprehensive phylogenetic analyses were performed by aligning the sequences of 145 SiNACs (Setaria italica NAC proteins), 126 AtNACs (Arabidopsis thaliana NAC proteins) and 151 PgNACs. All NACs were grouped into 8 groups (A to H). Group H was the largest group with 37 PgNAC members, while the smallest was group D with 5 members (Fig. 5). Most PgNAC-encoding genes in the same group shared similar exon-intron structures and/or duplication patterns. For instance, all the PgNAC-encoding members in groups D and E have 2 or 3 introns. Group B has the largest number (12) of duplicated genes.

Fig. 5.

Phylogenetic analysis of pearl millet and Setaria italica. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining method with 1000 bootstrap replicates as described in the legend for Fig. 3. The letters A-K correspond to the 11 NAC TF subfamilies

The MEME suite found 17 motifs in PgNACs. PgNAC N-terminal regions were found to be more conserved than C-terminal regions. Generally, PgNACs in the same groups showed similar motif compositions (Table 1 and Additional File 4), supporting the idea that their functions are also similar.

Table 1.

Conserved motifs present in pearl millet PgNACs. Conserved motifs were identified using the online tool MEME with the default parameters

| No. | Motif | Sites | E-value | Width | GO annotation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | TCCTCCTGGATTTAGATTTCATCCTACTGATGAWGAACTTRTTRNTYATT | 130 | 5.4e-1077 | 50 | BP: Multicellular organism development |

| 2. | AGAMCTAATAGAGCTACTGVWDCTGGATATTGGAAGGCTACTGGAAMKGA | 74 | 1.7e-852 | 50 | CC: chloroplastMF: RNA binding |

| 3. | TTGGAATGAAGAAGACTCTTGTTTTTTATAGAGGAAGAGCTCCTAAGGGA | 77 | 7.1e-802 | 50 | MF: oxygen binding |

| 4. | TGTTATTGCTGAAGTTGATATTTATAAGTTTGATCCTTGGGATCTTCCTG | 149 | 3.9e-805 | 50 | |

| 5. | AAGACTGATTGGATTATGCATGAATATAGACTTGAAGATGCTGATGATGC | 128 | 6.6e-773 | 50 | |

| 6. | AGGAATGGTATTTTTTTTCTCCTAGAGATAGAAAGTATCCTAATGGAGCT | 87 | 1.6e-640 | 50 | |

| 7. | CTGCTGCTCCTGCTCCTGCTCCTATTGTTATTGCTCAAGCTGCTGCTCCT | 145 | 1.2e-566 | 50 | |

| 8. | CTGCTGCTGGAGGAGGAGAAGGATCTTCTTCTGAAGCTGCTGCTGCTGCT | 145 | 5.8e-452 | 50 | CC: mitochondrionCC: chloroplast thylakoid membraneCC: anchored to membrane |

| 9. | TAAGGAAGATTGGGTTCTTTGTAGAGTTTTTTATAAGTCTAGAGCTACTA | 134 | 3.8e-395 | 50 | |

| 10. | TACTCTTACTCATGATTCTGTTATGCCTTCTACTGCTGCTCAAGTTTCTG | 125 | 2.6e-338 | 50 | MF: RNA bindingCC: chloroplast thylakoid membraneMF: transcription factor activityBP: protein transportMF: ATP binding |

| 11. | GCTCCTCCTCCTCCTCCTCCT | 143 | 7.5e-212 | 21 | |

| 12. | TTCCTAAGGTTGAACCTCAAGCTGATGATGGAGGAAATTCTCTTGCTGCT | 125 | 1.3e-259 | 50 | |

| 13. | CTTCTTGCTGATACTACTTCTGGAGCTTTTCAATATTCTTCTCTTCTTT | 125 | 1.6e-172 | 49 | CC: plasma membrane |

| 14. | TTAAGCTTGCTGGAGAAGCTCTTCCTGCTGCTGCTGGATCT | 121 | 3.6e-121 | 41 | |

| 15. | AGAAATTTCTTCTTCTTCTGATTATCTTAAGCTTCCTCCTGAACCTGCTG | 78 | 6.3e-104 | 50 | |

| 16. | TCTTGCTCCTAAGGCTGCTGATGCTGGA | 145 | 1.4e-093 | 28 | CC: chloroplast |

| 17. | GCTGATCCTTCTTCTGCTCCTGTTAAGGCTAAGAGACAAC | 53 | 2.2e-067 | 40 |

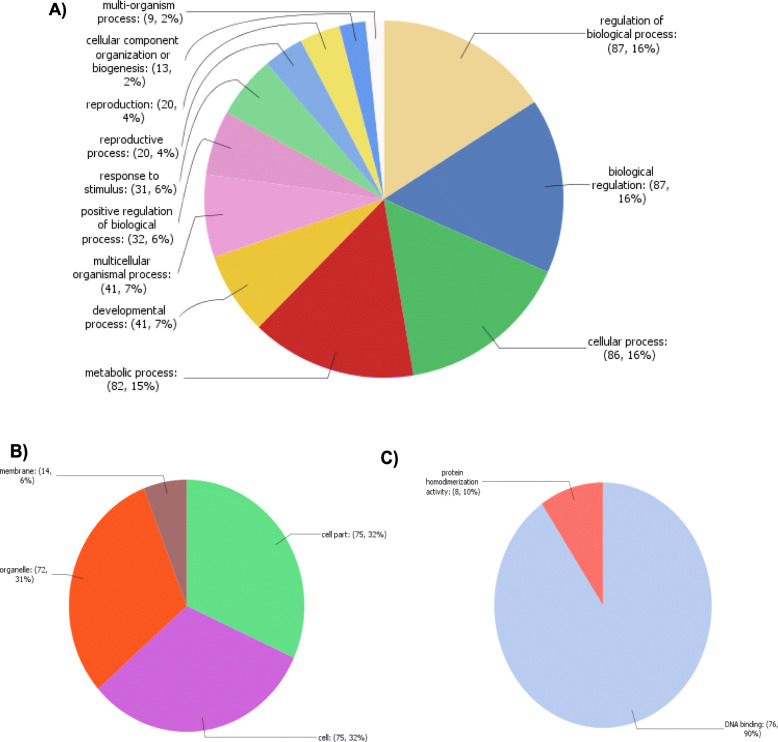

PgNACs GO annotation

GO term analysis suggested that the majority of PgNACs are involved in DNA binding (90%). Eight PgNACs (PgNAC009, PgNAC021, PgNAC085, PgNAC125, PgNAC029, PgNAC112, PgNAC118, and PgNAC137) were associated with the GO term “homodimerization”. Approximately 86.25% of PgNACs were associated with the GO term “Nucleus”. Nine PgNACs were associated with the GO term “external and internal stimuli”, and 29 were associated with “response to stress” (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Gene Ontology (GO) terms associated with PgNACs. a GO terms for the category “Biological process”. b GO terms for the category “Molecular functions”. c GO terms for the category “Cellular components”

miRNAs target sites in PgNACs

The results of analyzing miRNAs targeting PgNACs found a total of 88 miRNA target sites in the 59 PgNACs. Among them, PgNAC023 had the most (six) miRNA target sites. PgNAC023 is targeted by miRNA162, miRNA167h, miRNA394a and miRNA394b. PgNAC092 had four miRNA target sites, and is targeted by miR165a, miR165b, miR166b and miR166p. Among miRNAs, miR529 had the most (17) target sites in 14 PgNAC genes. In a previous study, miR529 was shown to regulate resistance to oxidative stress by targeting transcription factor genes in rice [25]. (Additional file: 5). Our findings suggest that expression of PgNACs is regulated by multiple miRNAs.

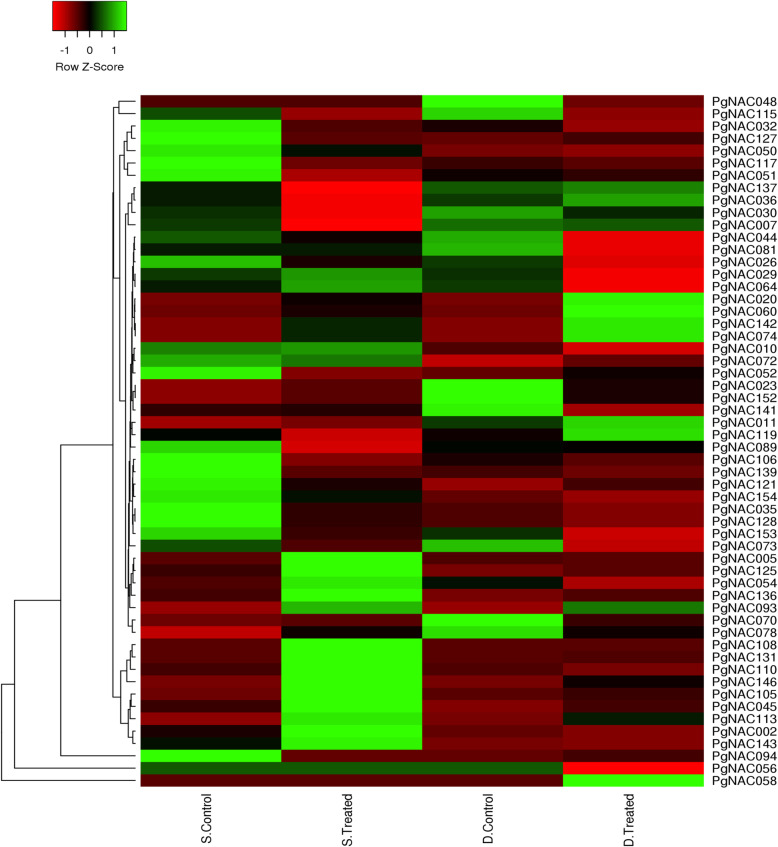

Transcriptomic expression of PgNACs during drought and salinity stress

PgNAC expression was examined using previously published transcriptome data. Seventy-two PgNACs were expressed under these drought-stressed and salinity-stressed conditions. PgNAC108, PgNAC131, PgNAC110, PgNAC146, PgNAC105, PgNAC045, PgNAC113, PgNAC002, PgNAC143, PgNAC005, PgNAC125, PgNAC054, and PgNAC136 were strongly expressed under salinity-stressed conditions. Whereas PgNAC137, PgNAC036, PgNAC007, PgNAC020, PgNAC060, PgNAC142, PgNAC074, and PgNAC011 were strongly expressed under drought-stressed conditions. PgNAC093, PgNAC142, PgNAC074, PgNAC020, and PgNAC060 were expressed under both salinity and drought conditions (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

PgNAC expression levels based on a previous transcriptome analysis. The colors in the heat map reflect PgNAC expression levels. The samples used included roots from non-stressed plants (S. Control); roots from salinity-stressed roots (S. Treated), roots from non-stressed roots (D. Control), and roots from drought-stressed plants (D. Treated)

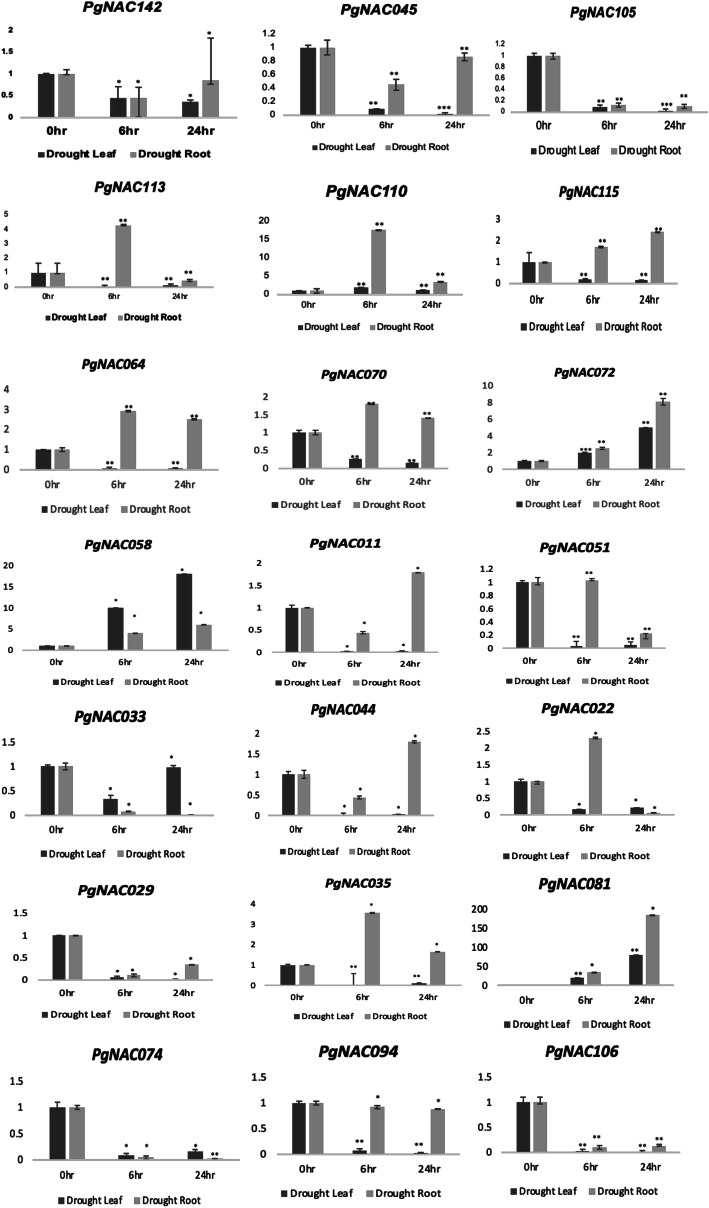

Expression profiling by qRT-PCR

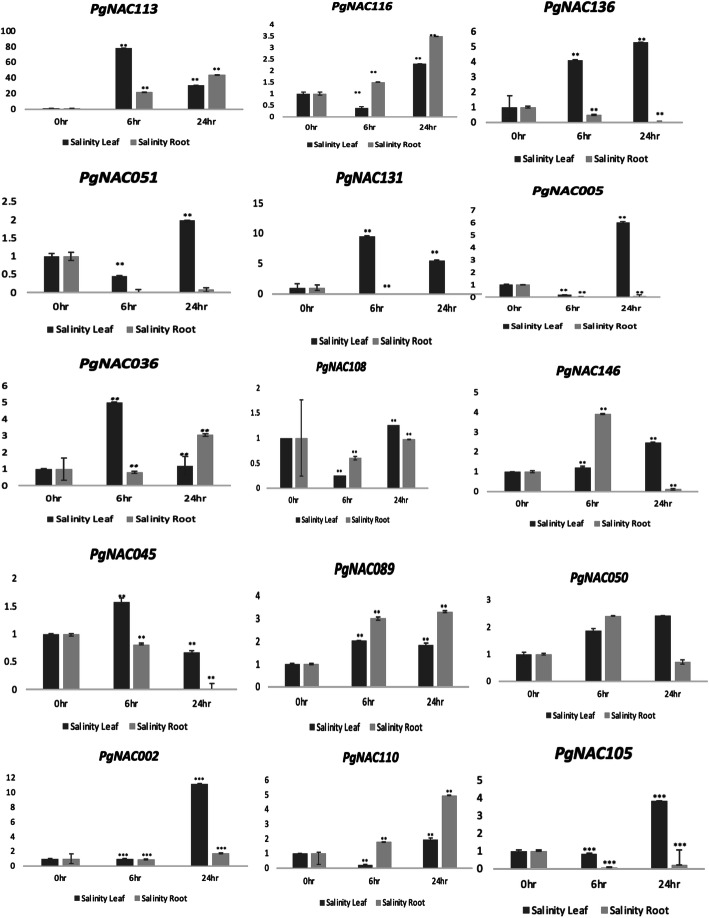

Quantitative RT-PCR was performed to confirm the expression of randomly selected PgNACs under drought and salinity stress. For drought, PgNAC142, PgNAC045, PgNAC105, PgNAC113, PgNAC110, PgNAC072, PgNAC044, PgNAC011, PgNAC022, PgNAC051, PgNAC029, PgNAC094, PgNAC106, PgNAC074, PgNAC033, PgNAC035, and PgNAC081 were studied. The expression of PgNAC081 was 170 times higher in roots under drought-stressed condition than control condition. Under drought-stressed conditions, most PgNACs were more strongly expressed in roots than in leaves (Fig. 8). PgNAC029, PgNAC106, and PgNAC074 were downregulated in both leaf and root tissues. For salinity, PgNAC051, PgNAC005, PgNAC036, PgNAC116, PgNAC146, PgNAC108 PgNAC131, PgNAC093, PgNAC089, PgNAC050, PgNAC136, PgNAC002, PgNAC113, PgNAC018, PgNAC105, PgNAC045 and PgNAC110 were selected. Most of these PgNACs were upregulated in both root and leaf tissues. PgNAC113 was strongly induced in roots by salinity stress (with 76-fold change) than control condition. (Fig. 9).

Fig. 8.

Expression of selected PgNACs under drought-stressed conditions. Pearl millet plants were exposed to drought stress for 0, 6, and 24 h, and their roots and leaves were sampled. The relative mRNA abundance of 21 selected PgNACs in these samples was determined by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR, with PgActin as an internal control. Data are presented as the means ± standard deviations (SD) of three biological replicates. Asterisk indicate significant differences. * P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, students t-test

Fig. 9.

Expression analysis of selected PgNACs for salinity. Pearl millet plants were exposed to salinity stress for 0, 6, and 24 h, and their roots and leaves were sampled. The relative mRNA abundance of 16 selected PgNACs was determined in these samples using quantitative reverse transcription-PCR, with PgActin as an internal control. Data are presented as the means ± standard deviations (SD) of three biological replicates. Asterisk indicate significant differences. * P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, students t-test

Discussion

The chromosomal distribution of PgNACs was uneven and clustered. This pattern is similar to the distribution of NAC TF genes in Setaria italica, Oryza sativa, Solanum tuberosum, Brachypodium distachyon and other species [24, 26–28]. Structurally diversified multigene family are known to develop during evolution to cope with changing environmental conditions [29]. The numbers of introns in PgNACs ranges from 0 to 12, which is comparable to NAC TF genes in rice (0–16) [26]. However, banana and cassava NAC TFs contain 0–5 and 0–9 introns, respectively [30, 31]. During gene duplication, the loss of introns occurs faster than the gain of introns [26]. The 29 PgNACs that have no introns may represent the original genes. In plants, segmental and dispersion duplication contributes to evolution of novel functions such as adaptation to stress [32]. In this study, 75% PgNAC genes exhibited either segmental or dispersion duplication. In miRNA-PgNACs association studies 88 miRNAs binding sites were found in 59 PgNACs. This association studies confirms that miRNAs are master regulators of PgNACs. Most of these pearl millet miRNAs targeting PgNACs are salinity and drought stress responsive. Previous studies have proved that miRNAs and NAC TFs together are key players of stress responses [33, 34]. However, further studies are necessary to elucidate the roles of these miRNAs and their association with pearl millet NACs.

Using qRT-PCR, we identified 36 PgNACs that respond to either drought or salinity stress. Some of the drought and salinity stress responsive PgNACs shows homology with previously reported stress responsive NAC genes [15, 28]. In our analysis, many PgNACs were upregulated in roots rather than in leaves. This difference may be because roots are the primary organ exposed to stress [2]. Similar results were obtained for NAC TF genes in Brachypodium distachyon when their expression levels were assessed after plants were exposed to cadmium stress [35]. In common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris), 11 NAC TF genes were upregulated by drought stress, while 8 were downregulated [36]. JUNGBRUNNEN 1 (JUB1), a NAC factor, acts as an important regulator of drought tolerance in Solanum lycopersicum [37]. Another Arabidopsis NAC TF, ANAC092, regulates senescence, seed germination, and tolerance to salt stress [38]. Several other NAC TFs, such as OsNAC6 [16, 39, 40] in rice; ANAC019, ANAC056 and ANAC072 [41] in Arabidopsis; and SNAC1 in cotton [15], are involved in establishing stress tolerance in plants. Similar to these NAC TFs, PgNACs are likely to regulate drought and salinity tolerance in pearl millet. In a previous study, one of the stress-responsive pearl millet NAC transcription factor gene, PgNAC21, was overexpressed in Arabidopsis, and improved its salinity stress tolerance [42]. In the future, we plan to perform functional characterization of other PgNAC genes. The stress responsive PgNAC genes identified in our study could be utilized as promising candidates for molecular breeding to generate new stress tolerant plant genotypes.

Conclusion

In our study, a comprehensive analysis including gene structure, phylogenetic analysis, chromosomal location, miRNA binding and expression analysis under abiotic stresses of the NAC gene family in pearl millet was first performed. We identified 151 NAC genes in the pearl millet genome, these genes provide preliminary information for the future functional characterization studies. Furthermore, expression analysis of PgNAC genes in root and leaf tissues and under salinity and drought stresses implied that PgNACs participate in the stress responses of the pearl millet. Our systematic analysis of the NAC TF genes in pearl millet lays foundation for the follow-up study of the functional characteristics of PgNAC genes and the cultivation of stress tolerant pearl millet varieties. In future, we will study functions of some of the key PgNACs by overexpressing them in pearl millet or Arabidopsis thaliana.

Methods

Sequence retrieval, database searches and domain searches

To identify the PgNACs, 35,756 coding gene sequences of pearl millet were retrieved from the GIGA database (http://gigadb.org/dataset/100192) and converted to all 6 standard reading frames with the standalone JEMBOSS software [43, 44]. Nucleotide sequences for the 1016 NAC TFs from Arabidopsis thaliana, Oryza sativa, Setaria italica, Sorghum bicolor and Zea mays were retrieved from the Plant Transcription Factor Database v4.0 (http://planttfdb.cbi.pku.edu.cn/family.php?fam=NAC) [11] and used as subjects to perform BLAST searches against the pearl millet coding sequences. The hidden Markov model (HMM) profile of NAC and NAM domains was extracted from the pFAM database [45–47], and NAC and NAM HMM profiles were used to search the pearl millet genome sequences for specific domains using HMMER [48]. Hits with an expected value less than 1.0 were selected, and redundancy was minimized using the decrease redundancy tool (https://web.expasy.org/decrease_redundancy). The presence of NAC domains in the filtered sequences was confirmed by SMART (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de) and pFAM (http://pfam.xfam.org/). For the transmembrane motifs, the sequences were searched using the TMHMM server ver 2.0 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM/).

Chromosome positioning, gene structure and gene duplication analysis for PgNACs

The BLASTN program in the BLAST+ suite [49] was performed using PgNAC sequences as queries and the pearl millet genome sequence (Taxid: 4543) as the database to determine the positions of PgNACs in the pearl millet genome. The positions of PgNACs in the genome were displayed using MapChart [50]. Gene structure display server program (GSDS, http://gsds.cbi.pku.edu.cn/index.php) was utilized to show exon/intron structure of each PgNAC gene by comparing the coding sequences with their corresponding genomic sequences [51]. NAC sequences of Arabidopsis thaliana were extracted from TAIR database [52]. MCScanX was employed to analyze various types of duplications including segmental, tandem, proximal and dispersed with default parameters. Members of NAC gene family with the segmental duplication and collinear analysis were retrieved from the above datasets for further analysis [53].

Phylogenetic analysis and conserved motif identification

For phylogenetic analysis, the sequences of all NAC transcription factors were imported into MEGA7, and multiple sequence alignment was performed using CLUSTALW with the default’s parameters. A file with the extension “.MEG” was used to construct an unrooted phylogenetic tree based on the neighbor-joining method using bootstrap analysis with 1000 replicates [54]. The MEGA7 output tree was edited using the Interactive Tree of Life online tool (iTOL; https://itol.embl.de/). Conserved motifs in the NAC transcription factor sequences were identified using multiple EM for motif elicitation (MEME suite). The input parameters for motif identification were as follows: number of repetitions, any; maximum number of motifs, 20; and width of motif, 50. The discovered motifs were annotated using GOMo gene ontology [55].

Prediction of microRNAs target sites in PgNACs

In pearl millet, microRNAs (miRNAs) have been reported to be involved in stress responses [3, 56]. MiRNAs are small (20–24 nucleotides) non-coding RNAs derived from single-stranded precursors. MiRNAs negatively regulate target genes by pairing to the corresponding gene and facilitating its cleavage [57]. The psRNATarget tool was used to identify the target sites of pearl millet miRNAs in PgNACs (http://plantgrn.noble.org/psRNATarget/) [58]. To avoid false-positives, only gene sequences with a 3.0 points cut-off threshold were considered miRNAs target genes.

NAC TF GO annotation and expression analysis using transcriptome data

Gene Ontology (GO) terms were assigned to PgNACs using the Blast2GO program based on their similarities to Oryza sativa proteins (National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) taxid: 4530) [59].

Previously available RNA sequencing data for drought and salinity conditions were primarily used to examine the expression of the PgNACs. These data were retrieved from the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under accession numbers SRR6327851 to SRR6327856; SRR6327857 to SRR6327862 for drought-stressed samples and SRP128956 for salinity-stressed samples [2, 4].

Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR)

Drought- (ICMB843) and salinity-tolerant (ICMB01222) pearl millet genotypes were obtained from the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT), India. Eexperiments were conducted under controlled greenhouse conditions. Approximately, 20 seeds from each genotype were sown in equal volumes of soil and vermiculite in perforated terracotta pots. Each growth experiment was performed in triplicate. Drought stress was imposed on 21-day-old plants by incubating the plants in 20% (w/v) PEG for 6 and 24 h, while control plants were maintained in normal water. For salinity stress, plants were incubated in 250 mM NaCl solution for 6 and 24 h. Total RNA was isolated from root and leaf tissues with Trizol. For cDNA synthesis, 1 μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed with oligo (dT) primers and PrimeScript Reverse Transcriptase. To examine PgNAC genes expression, real-time PCR was performed using a step-one real-time instrument and the TB Green I kit (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Reactions were performed in triplicate and each reaction mixture contained 100 ng of cDNA, 1 μL of each primer (10 μM/μL) and 10 μL of TB green master mix in a final volume of 20 μL. The primers sequences used for qRT-PCR are provided in (Additional File 1). The PCR conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s and 60 °C for 30 s, and melt-curve analysis. The PgActin gene was used as a reference [60]. The qPCR assays were performed with three replicates. Relative fold differences for each sample in each experiment were calculated using the ΔΔCt method [61].

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. List of primers used in quantitative real time-PCR expression analysis of PgNAC genes.

Additional file 2. Detail catalogue of NAC in pearl millet.

Additional file 3 Gene structure of PgNACs. Image was created by submitting the sequences to the gene structure display 2.0 online tool. Red boxes denote the exon/coding region, black lines are intron and blue boxes defines.

Additional file 4 Location of 17 Motifs on the PgNACs. The location of motifs were derived by the multiple alignment of the motifs by online tool MAST. Each of the following 152 sequences has an E-value less than 10. The motif matches shown here have a position p-value less than 0.0001. Colored boxes represent the respective motif.

Additional file 5. Analyzing pearl millet miRNAs targeting PgNACs.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to ICRISAT, India for providing the pearl millet seeds for this study.

Authors’ contributions

AD and TT designed the experiments. AD, HS and PY performed the experimental work. AD analyzed the data. AD wrote the manuscript. TT and DT revised and reviewed the manuscript. SL and SG contributed reagents and experimental materials. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ambika Dudhate, Email: ambika_dudhate@anesc.u-tokyo.ac.jp, Email: ambika_dudhate@uky.edu.

Harshraj Shinde, Email: hsshinde@anesc.u-tokyo.ac.jp, Email: harshraj19@uky.edu.

Pei Yu, Email: yupei@anesc.u-tokyo.ac.jp.

Daisuke Tsugama, Email: dtsugama@anesc.u-tokyo.ac.jp.

Shashi Kumar Gupta, Email: S.Gupta@cgiar.org.

Shenkui Liu, Email: shenkuiliu@nefu.edu.cn.

Tetsuo Takano, Email: takano@anesc.u-tokyo.ac.jp.

References

- 1.Shivhare R, Lata C. Exploration of Genetic and Genomic Resources for Abiotic and Biotic Stress Tolerance in Pearl Millet. Front Plant Sci. 2017;7. 10.3389/fpls.2016.02069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Dudhate A, Shinde H, Tsugama D, Liu S, Takano T. Transcriptomic analysis reveals the differentially expressed genes and pathways involved in drought tolerance in pearl millet [Pennisetum glaucum (l.) r. Br]. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0195908. 10.1371/journal.pone.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Jaiswal S, Antala TJ, Mandavia MK, Chopra M, Jasrotia RS, Tomar RS, et al. Transcriptomic signature of drought response in pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum L.) and development of web-genomic resources. Sci Rep. 2018;8:3382. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-21560-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shinde H, Tanaka K, Dudhate A, Tsugama D, Mine Y, Kamiya T, et al. Comparative de novo transcriptomic profiling of the salinity stress responsiveness in contrasting pearl millet lines. Environ Exp Bot. 2018;155:619–627. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2018.07.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shivhare R, Asif MH, Lata C. Comparative transcriptome analysis reveals the genes and pathways involved in terminal drought tolerance in pearl millet. Plant Mol Biol. 2020;103:639–52. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Varshney RK, Shi C, Thudi M, Mariac C, Wallace J, Qi P, et al. Pearl millet genome sequence provides a resource to improve agronomic traits in arid environments. Nat Biotechnol. 2017;35:969. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shrivastava P, Kumar R. Soil salinity: a serious environmental issue and plant growth promoting bacteria as one of the tools for its alleviation. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2015;22:123–131. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daryanto S, Wang L, Jacinthe PA. Global synthesis of drought effects on maize and wheat production. PLoS One. 2016;11:1–16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nelson GC, Valin H, Sands RD, Havlík P, Ahammad H, Deryng D, et al. Climate change effects on agriculture: economic responses to biophysical shocks. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2014;111:3274–3279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222465110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Seki M. Regulatory network of gene expression in the drought and cold stress responses. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2003;6:410–417. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5266(03)00092-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jin J, Tian F, Yang DC, Meng YQ, Kong L, Luo J, et al. PlantTFDB 4.0: toward a central hub for transcription factors and regulatory interactions in plants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D1040–D1045. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nuruzzaman M, Sharoni AM, Kikuchi S. Roles of NAC transcription factors in the regulation of biotic and abiotic stress responses in plants. Front Microbiol. 2013;4:1–16. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aida M. Genes involved in organ separation in Arabidopsis: an analysis of the cup-shaped cotyledon mutant. Plant Cell Online. 1997;9:841–857. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.6.841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kikuchi K, Ueguchi-Tanaka M, Yoshida KT, Nagato Y, Matsusoka M, Hirano HY. Molecular analysis of the NAC gene family in rice. Mol Gen Genet. 2000;262:1047–1051. doi: 10.1007/PL00008647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu G, Li X, Jin S, Liu X, Zhu L, Nie Y, et al. Overexpression of rice NAC gene SNAC1 improves drought and salt tolerance by enhancing root development and reducing transpiration rate in transgenic cotton. PLoS One. 2014;9:e86895. 10.1371/journal.pone.0086895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Rachmat A, Nugroho S, Sukma D, Aswidinnoor H. Sudarsono. Overexpression of OsNAC6 transcription factor from Indonesia rice cultivar enhances drought and salt tolerance. Emirates J Food Agric. 2014;26:519–27.

- 17.Mao X, Zhang H, Qian X, Li A, Zhao G, Jing R. TaNAC2, a NAC-type wheat transcription factor conferring enhanced multiple abiotic stress tolerances in Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot. 2012;63:2933–2946. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xue GP, Way HM, Richardson T, Drenth J, Joyce PA, McIntyre CL. Overexpression of TaNAC69 leads to enhanced transcript levels of stress up-regulated genes and dehydration tolerance in bread wheat. Mol Plant. 2011;4:697–712. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssr013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li X, Li X, Li M, Yan Y, Liu X, Li L. Dual function of NAC072 in ABF3-mediated ABA-responsive gene regulation in Arabidopsis. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1–9. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shiriga K, Sharma R, Kumar K, Yadav SK, Hossain F, Thirunavukkarasu N. Genome-wide identification and expression pattern of drought-responsive members of the NAC family in maize. Meta Gene. 2014;2:407–417. doi: 10.1016/j.mgene.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang D, Zhou L, Chen W, Ye N, Xia J, Zhuang C. Overexpression of a microRNA-targeted NAC transcription factor improves drought and salt tolerance in Rice via ABA-mediated pathways. Rice. 2019;12. 10.1186/s12284-019-0334-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Jeong JS, Kim YS, Redillas MCFR, Jang G, Jung H, Bang SW, et al. OsNAC5 overexpression enlarges root diameter in rice plants leading to enhanced drought tolerance and increased grain yield in the field. Plant Biotechnol J. 2013;11:101–114. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ooka H, Satoh K, Doi K, Nagata T, Otomo Y, Murakami K, et al. Comprehensive analysis of NAC family genes in Oryza sativa and Arabidopsis thaliana. DNA Res. 2003;10:239–247. doi: 10.1093/dnares/10.6.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Puranik S, Sahu PP, Mandal SN, Suresh BV, Parida SK, Prasad M. Comprehensive genome-wide survey, genomic constitution and expression profiling of the NAC transcription factor family in foxtail millet (Setaria italica L.) PLoS One. 2013;8:1–16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yue E, Liu Z, Li C, Li Y, Liu Q, Xu JH. Overexpression of miR529a confers enhanced resistance to oxidative stress in rice (Oryza sativa L.) Plant Cell Rep. 2017;36:1171–1182. doi: 10.1007/s00299-017-2146-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nuruzzaman M, Manimekalai R, Sharoni AM, Satoh K, Kondoh H, Ooka H, et al. Genome-wide analysis of NAC transcription factor family in rice. Gene. 2010;465:30–44. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singh A, Sharma V, Pal A. Genome-wide organization and expression profiling of the NAC transcription factor family in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) DNA Res. 2013;20:403–423. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dst019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.You J, Zhang L, Song B, Qi X, Chan Z. Systematic analysis and identification of stress-responsive genes of the NAC gene family in Brachypodium distachyon. PLoS One. 2015;10:1–20. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shang H, Li W, Zou C, Yuan Y. Analyses of the NAC transcription factor gene family in gossypium raimondii Ulbr.: chromosomal location, structure, phylogeny, and expression patterns. J Integr Plant Biol. 2013;55:663–676. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cenci A, Guignon V, Roux N, Rouard M. Genomic analysis of NAC transcription factors in banana (Musa acuminata) and definition of NAC orthologous groups for monocots and dicots. Plant Mol Biol. 2014;85:63–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Hu W, Wei Y, Xia Z, Yan Y, Hou X, Zou M, et al. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the NAC transcription factor family in cassava. PLoS One. 2015;10:1–25. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Panchy N, Lehti-Shiu M, Shiu SH. Evolution of gene duplication in plants. Plant Physiol. 2016;171:2294–2316. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.00523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.AFA S, Sajad M, Nazaruddin N, Fauzi IA, AMA M, Zainal Z, et al. MicroRNA and transcription factor: Key players in plant regulatory network. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:1–18. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hernández Y, Sanan-Mishra N. miRNA mediated regulation of NAC transcription factors in plant development and environment stress response. Plant Gene. 2017;11:190–198. doi: 10.1016/j.plgene.2017.05.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhu G, Chen G, Zhu J, Zhu Y, Lu X, Li X, et al. Molecular characterization and expression profiling of NAC transcription factors in Brachypodium distachyon L. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0139794. 10.1371/journal.pone.0139794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Wu J, Wang L, Wang S. Comprehensive analysis and discovery of drought-related NAC transcription factors in common bean. BMC Plant Biol. 2016;16:10.1186/s12870-016-0882–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Thirumalaikumar VP, Devkar V, Mehterov N, Ali S, Ozgur R, Turkan I, et al. NAC transcription factor JUNGBRUNNEN1 enhances drought tolerance in tomato. Plant Biotechnol J. 2018;16:354–66. 10.1111/pbi.12776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Balazadeh S, Siddiqui H, Allu AD, Matallana-Ramirez LP, Caldana C, Mehrnia M, et al. A gene regulatory network controlled by the NAC transcription factor ANAC092/AtNAC2/ORE1 during salt-promoted senescence. Plant J. 2010;62:250–64. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Nakashima K, Tran LSP, Van Nguyen D, Fujita M, Maruyama K, Todaka D, et al. Functional analysis of a NAC-type transcription factor OsNAC6 involved in abiotic and biotic stress-responsive gene expression in rice. Plant J. 2007;51:617–630. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ohnishi T, Sugahara S, Yamada T, Kikuchi K, Yoshiba Y, Hirano H-Y, et al. OsNAC6, a member of the NAC gene family, is induced by various stresses in rice. Genes Genet Syst. 2005;80:135–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Ooka H, Satoh K, Doi K, Nagata T, Otomo Y, Murakami K, et al. Comprehensive analysis of NAC family genes in Oryza sativa and Arabidopsis thaliana. DNA Res. 2003;239–47. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Shinde H, Dudhate A, Tsugama D, Gupta SK, Liu S, Takano T. Pearl millet stress-responsive NAC transcription factor PgNAC21 enhances salinity stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2019;135:546–53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Rice P, Longden L, Bleasby A. EMBOSS: The European Molecular Biology Open Software Suite. Trends Genet. 2000;16:276–87. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Carver T, Bleasby A. The design of Jemboss: a graphical user interface to EMBOSS. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1837–43. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Finn RD, Bateman A, Clements J, Coggill P, Eberhardt RY, Eddy SR, et al. Pfam: The protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;1:222–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Sonnhammer ELL, Eddy SR, Birney E, Bateman A, Durbin R. Pfam: Multiple sequence alignments and HMM-profiles of protein domains. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Coggill P, Finn RD, Bateman A. Identifying protein domains with the Pfam database. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2008;1:512–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Finn RD, Clements J, Arndt W, Miller BL, Wheeler TJ, Schreiber F, et al. HMMER web server: 2015 Update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:W30–W38. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Camacho C, Coulouris G, Avagyan V, Ma N, Papadopoulos J, Bealer K, et al. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:10.1186/1471-2105-10–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Voorrips RE. MapChart: software for the graphical presentation of linkage maps and QTLs. J Hered. 2002;93:77–78. doi: 10.1093/jhered/93.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hu B, Jin J, Guo AY, Zhang H, Luo J, Gao G. GSDS 2.0: An upgraded gene feature visualization server. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:1296–1297. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huala E, Dickerman AW, Garcia-Hernandez M, Weems D, Reiser L, LaFond F, et al. The Arabidopsis information resource (TAIR): a comprehensive database and web-based information retrieval, analysis, and visualization system for a model plant. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:102–105. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang Y, Tang H, Debarry JD, Tan X, Li J, Wang X, et al. MCScanX: a toolkit for detection and evolutionary analysis of gene synteny and collinearity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:1–14. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Buske FA, Bodén M, Bauer DC, Bailey TL. Assigning roles to DNA regulatory motifs using comparative genomics. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:860–866. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shinde H, Dudhate A, Anand L, Tsugama D, Gupta SK, Liu S, et al. Small RNA sequencing reveals the role of pearl millet miRNAs and their targets in salinity stress responses. South African J Bot. 2020;132:395–402. doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2020.06.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Voinnet O. Origin, biogenesis, and activity of plant MicroRNAs. Cell. 2009;136:669–687. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dai X, Zhuang Z, Zhao PX. PsRNATarget: a plant small RNA target analysis server (2017 release) Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:49–54. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Conesa A, Götz S. Blast2GO: a comprehensive suite for functional analysis in plant genomics. Int J Plant Genomics. 2007;2008:1–12. doi: 10.1155/2008/619832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shivhare R, Lata C. Selection of suitable reference genes for assessing gene expression in pearl millet under different abiotic stresses and their combinations. Sci Rep. 2016;14:23036. 10.1038/srep23036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 61.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. List of primers used in quantitative real time-PCR expression analysis of PgNAC genes.

Additional file 2. Detail catalogue of NAC in pearl millet.

Additional file 3 Gene structure of PgNACs. Image was created by submitting the sequences to the gene structure display 2.0 online tool. Red boxes denote the exon/coding region, black lines are intron and blue boxes defines.

Additional file 4 Location of 17 Motifs on the PgNACs. The location of motifs were derived by the multiple alignment of the motifs by online tool MAST. Each of the following 152 sequences has an E-value less than 10. The motif matches shown here have a position p-value less than 0.0001. Colored boxes represent the respective motif.

Additional file 5. Analyzing pearl millet miRNAs targeting PgNACs.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].