Summary

Takayasu arteritis is a rare inflammatory disease of large arteries. We performed a genetic study in Takayasu arteritis comprising 6,670 individuals (1,226 affected individuals) from five different populations. We discovered HLA risk factors and four non-HLA susceptibility loci in VPS8, SVEP1, CFL2, and chr13q21 and reinforced IL12B, PTK2B, and chr21q22 as robust susceptibility loci shared across ancestries. Functional analysis proposed plausible underlying disease mechanisms and pinpointed ETS2 as a potential causal gene for chr21q22 association. We also identified >60 candidate loci with suggestive association (p < 5 × 10−5) and devised a genetic risk score for Takayasu arteritis. Takayasu arteritis was compared to hundreds of other traits, revealing the closest genetic relatedness to inflammatory bowel disease. Epigenetic patterns within risk loci suggest roles for monocytes and B cells in Takayasu arteritis. This work enhances understanding of the genetic basis and pathophysiology of Takayasu arteritis and provides clues for potential new therapeutic targets.

Keywords: Takayasu arteritis, GWAS, vasculitis, genetic association, eQTL, epigenetic, genetic risk scroe, chromatin interaction, HLA

Introduction

Takayasu arteritis is a rare inflammatory disease affecting large arteries, most frequently the aorta and its major branches. Clinical manifestations result from vascular complications such as stenoses, occlusions, and aneurysms and may also include non-specific symptoms such as fatigue, fever, and weight loss.1,2 Disease onset typically occurs in the second or third decade of life and the disease is more common in women. Takayasu arteritis has been reported worldwide, but disease prevalence varies across populations and is the highest in East Asia.3 Although the etiology of Takayasu arteritis is incompletely understood, there is strong evidence for a role of genetic factors in the disease pathophysiology.4

The first suggestion of a genetic component to Takayasu arteritis arose in the 1960’s with the publication of a case report of familial aggregation of the disease.5 Later in the 1970’s, the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) was the first genetic region identified as a susceptibility factor. The association with the HLA-B∗52 allele remains the most robust genetic signal in Takayasu arteritis.4 In the last decade, four large-scale genetic analyses have been conducted, but only nine non-HLA genetic loci have been revealed with a genome-wide level of significance.6, 7, 8, 9 Despite the recent progress achieved, our knowledge of the genetic component of Takayasu arteritis remains significantly limited compared to other immune-mediated diseases. In this regard, two main limitations can be highlighted. First, the low prevalence of this form of vasculitis makes the collection of large cohorts challenging, thereby limiting the statistical power needed to uncover the genetic basis of the disease. Second, even though Takayasu arteritis has been described in all ancestries, large genetic studies have only analyzed individuals from Turkish, European-American, and Japanese populations.7, 8, 9 Awareness of the importance of including diverse and under-represented ancestry populations in genetic studies is growing and is positioned high on the priorities of genomic research.

We performed a large genome-wide association study (GWAS) in Takayasu arteritis, using affected individuals and control individuals from five diverse ancestries. We discovered several susceptibility loci for the disease. Functional and epigenetic enrichment analyses provided insights into the pathogenesis of Takayasu arteritis and revealed potential therapeutic targets.

Subjects and methods

Study population and genotyping

The total study population comprised 1,226 individuals diagnosed with Takayasu arteritis from five populations (Turkish, Northern European descendant from North America and the United Kingdom, Han Chinese, South Asian, and Italian) and 5,444 ancestry-matched unaffected individuals. All affected individuals fulfilled the American College of Rheumatology 1990 classification criteria for Takayasu arteritis.10 For 591 individuals diagnosed with Takayasu arteritis, genotyping data were generated via Infinium Global Screening Array-24 v.2.0 and Infinium OmniZhongHua-8 v.1.3 (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For the remaining individuals included in the analyses, the genotyping data were obtained from a previously published GWAS6 and from the Database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGAP) and the 1000 Genomes Project.11,12 A detailed description of the study population and the genotyping platforms used for each cohort can be found in Table S1. The study was approved by the institutional review boards and the ethics committees at all participating institutions, and written informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Quality controls and imputation

Unified stringent quality control (QC) of the data was conducted for each cohort separately before imputation via PLINK v.1.9.13 Samples were removed if they had a genotyping call rate < 95%. In addition, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) with a genotyping call rate < 98%, minor allele frequency (MAF) < 1%, and those deviated from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) in affected and control individuals (p value < 1 × 10−3) were filtered out. Sex chromosomes were not analyzed. In addition, duplicated or multi-allelic SNPs as well as those A/T-C/G SNPs with MAF > 0.4 were removed to avoid errors in the imputation process. Combining of QC-filtered genotyping datasets in each population was carried out before imputation unless the number of overlapping SNPs among different genotyping arrays was too low for imputation. In that case, imputation of each dataset was performed before merging. Imputation of genetic data was conducted with the Michigan Imputation Server with Minimac314 and the Haplotype Reference Consortium (HRC) r1.1 as reference population for all datasets.15 The software SHAPEIT16 was used for haplotype reconstruction. To control for potential imputation errors because different genotyping platforms were used, we used only SNPs with stringent correlation values (R2 > 0.9) for further analyses. Subsequently, imputed data were subjected to additional QC: MAF < 1% and HWE p value < 1 × 10−3. After merging different datasets, we used PLINK to detect strand consistency, and any SNP showing inconsistency was discarded from further analysis. To avoid the presence of first-degree relatives and/or duplicate subjects, we evaluated relatedness by using the genome function in PLINK v.1.913 and removed one individual from each pair (Pi-HAT > 0.4). We assessed principal-component analysis (PCA) to control for possible population stratification, and we used Eigensoft 6.1.4 software to calculate the principal components for each population independently by using around 100,000 independent SNPs.17 Individuals found >6 standard deviations from the cluster centroids were considered outliers and were removed. The corresponding plots were produced with R 3.6 software18 (Figure S1).

Classical HLA alleles imputation

Imputation of classical HLA alleles was performed with the HLA∗IMP:03 v.0.1.0 online software19 after following instructions detailed on its website. Briefly, this software used a multi-ancestral reference panel of 10,561 individuals (8,768 European, 869 Asian, 568 African American/African, and 365 Latino) with genotyping data as well as lab-based typing alleles. A total of 6,114 post-QC phased genotyped markers within the expanded HLA region (chr6: 20 to 40 Mb) were used for the imputation of both HLA class I and class II loci (HLA-A, HLA-B, HLA-C, HLA-DQA1, HLA-DQB1, and HLA-DRB1) at 2 fields of resolution. Only alleles with an imputation posterior probability of 0.9 were considered successfully imputed and used for the analyses.

Data analysis

First, we conducted logistic regression by using the 10 first principal components as covariates for each population independently. The genomic inflation factor (λ) was calculated for each cohort, and quantile-quantile (Q-Q) plots were generated with and without the HLA region. Next, the results of the logistic regression were meta-analyzed by means of the inverse variance method. A fixed-effects model was applied for those SNPs without evidence of heterogeneity, more than 90% of all SNPs (Cochran’s Q test p value [Q] > 0.1 and heterogeneity index [I2] < 50%), and a random-effects model was applied for SNPs displaying heterogeneity of effects between studies (Q ≤ 0.1 and I2 ≥ 50%). Genome-wide significance was established at a p value ≤ 5 × 10−8, and a threshold of p value ≤ 5 × 10−5 was set for suggestive associations. To identify independent associations in the HLA region, we conducted dependency analyses by using a stepwise strategy at the population level followed by inverse variance meta-analysis. First, we used the most associated variant identified in the meta-analysis within the HLA region as covariate to perform the conditional logistic regressions in each population separately. The results from the conditional logistic regressions were then meta-analyzed by the inverse variance method, and the SNP showing the most significant association was considered as an independent association and used as covariate in the second round of conditional logistic regressions in each of the populations and meta-analysis. This process was repeated until no variant reached a GWAS level of significance (p value < 5 × 10−8). In addition, using a similar approach, we also carried out pairwise conditional analysis among the independent SNPs identified and the classical HLA alleles found associated with Takayasu arteritis (p value < 5 × 10−8). We used PLINK v.1.913 for the analyses and qqman R package to generate the Manhattan and Q-Q plots.

Functional annotation

To evaluate the potential causality of the identified associated variants, we performed a detailed functional annotation by using a combination of in silico tools and public datasets. We used HaploReg v.4.1 to perform epigenomic annotation.20 To explore expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs) across different human tissues, we used several public databases: the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project,21 Blood NESDA NTR Conditional eQTL Catalog,22 Blood eQTL,23 and RegulomeDB.24 In addition, we checked the GTEx project to identify genetic variants regulating gene structure, named splicing QTLs (sQLTs). Finally, chromatin interactions between SNPs and gene promoter regions were evaluated via the webtool Capture Hi-C plotter (CHiCP; see Web Resources).25

Enrichment analyses

We performed a functional epigenomic enrichment analysis to assess whether disease-associated non-HLA SNPs were over- or under-represented among regulatory elements in the genome. GenomeRunner software26 was used to examine the SNP list (5 × 10−8 p value cutoff was used) within a regulatory context. Briefly, 127 reference epigenomes and seven epigenetic marks obtained from the Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) and the Roadmap Epigenomics Consortium projects were analyzed. H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 mark active and silenced promoters, respectively. H3K4me1 is associated with enhancers and regions downstream of transcription factor (TF) binding sites, and H3K4me2 has been related with both promoters and enhancers. H3K9me3 has been associated with repressive heterochromatic states. Finally, acetylation in H3K9 and H3K27 has been associated with transcriptional initiation and open chromatin structure. The processed gapped peak annotation panels were selected for these analyses.27,28 To control for functional enrichments occurring by chance, we used all common SNPs from dbSNP v.142 as background. The enrichment p values shown were corrected for multiple testing via a false discovery rate (FDR) calculation (FDR p values < 0.05 were considered significant).

The identification of key pathways was performed by Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis with Metascape.29 Disease-associated genetic variants (p value < 5 × 10−5) located within 50 kb of a gene were annotated, and those genes were used for this analysis. The Biological Process ontology branch was selected and only terms with p value < 1 × 10−3 and at least three genes were considered. Bonferroni corrected p values (q values) are also shown. Because GO terms often overlap, we categorized the results with a cluster-based approach based on GO similarities to provide better interpretation.

Cumulative genetic risk score

We investigated whether a cumulative genetic risk score (GRS) for Takayasu arteritis varies across populations. We examined the GRSs of a total of 2,504 individuals from the five major populations included in the 1000 Genomes Project phase 3 release: African, n = 661; Admixed American, n = 347; East Asian, n = 504; European, n = 503; South Asian, n = 489.12 The GRS calculation was carried out following the method described by Hughes et al.30 Briefly, the GRS of each individual is calculated by the sum of the number of risk alleles (0, 1, or 2) from each SNP multiplied by the natural logarithm of its odds ratio (OR). The SNPs and the OR values used are listed in Table S2. We included the most significant genetic variant in each locus identified with a suggestive level of significance (p value < 5 × 10−5) in our meta-analysis, plus the variant rs12524487, which tags HLA-B∗52, the most robust genetic association in Takayasu arteritis confirmed in every population studied.7 We analyzed a total of 70 genetic variants (two loci were excluded because of the lack of the associated variant information in the 1000 Genomes Project data). ORs used were those obtained in the meta-analysis. To determine whether the cumulative GRS was different across populations, we performed one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test by using GraphPad Prism v.8.1.1 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). ANOVA p values < 0.05 and Tukey’s adjusted p values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Takayasu arteritis’ genetic relationship with other immune-mediated diseases

We projected Takayasu arteritis into a previously constructed lower-dimensional representation of immune-mediated disease (IMD) genetics, an “IMD basis,” by using the project_sparse function from the cupcake R package. To represent all the ancestral groups included in this study, we used the summary statistic of the meta-analysis for these analyses. Projection requires knowledge of the linkage disequilibrium (LD) between variants, and we used an LD matrix estimated from our GWAS samples to allow for the different ancestries included.

Takayasu arteritis was compared to (1) IMD GWASs; (2) UK Biobank self-reported disease traits “round 2” version, which contains the most complete coverage of self-reported IMD but is restricted to the white European subset of participants; (3) UK Biobank ICD code traits from GeneAtlas,31 which does not restrict by ancestry, although most genotyped participants included in the UK Biobank were also white European;32 and (4) GWAS summary data from FinnGen, and it was restricted to traits starting with the codes D-S because we considered this subset to represent non-infectious, non-cancer diseases.

Classes 1–3 were available in supplementary tables of Burren et al.,33 while GWAS summary data from FinnGen was accessed from its website. We used classes 1–2 to generate the hierarchical clustering, whereas we used classes 3–4 for comparisons based on Mahalanobis distance. Mahalanobis distance was calculated as (P j – P TAK)′ S−1 (P j − P TAK) where P j and P TAK represent the projected vectors of trait j and TAK respectively and S represents the correlation between components calculated from the European LD reference matrix. We confirmed that results were visually indistinguishable if we used the LD matrix calculated from the samples in this study.

Results

Multi-ancestral meta-analysis

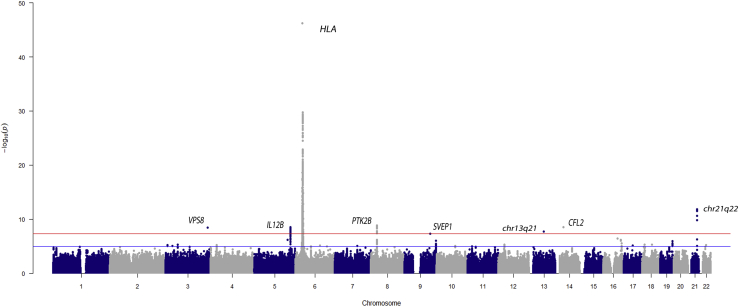

We report a cross-ancestry meta-analysis comprised of individuals from five different populations: Turkish, Northern European descendant, Han Chinese, South Asian, and Italian. From the original 6,670 individuals (1,226 affected individuals), a total of 6,221 individuals (1,091 affected individuals) and around 4 million variants were maintained after stringent QC filtering (a summary of sample/variant QC is shown in Table S3). First, we performed logistic regression analyses in each population independently (Figure S2) followed by a meta-analysis including all cohorts. Results of genomic control analysis showed no evidence of population stratification for any cohort (Figure S3 and Table S3). The results of the meta-analysis are illustrated in Figure 1. As expected, the most robust association signal was observed within the HLA region.

Figure 1.

Manhattan plot showing the results of the meta-analysis among the five populations included in this study

The −log10 p value for the genetic variants analyzed are plotted against their physical chromosomal position. The red and blue lines represent the genome-wide level of significance (p value < 5 × 10−8) and the suggestive level of significance (p value < 5 × 10−5), respectively.

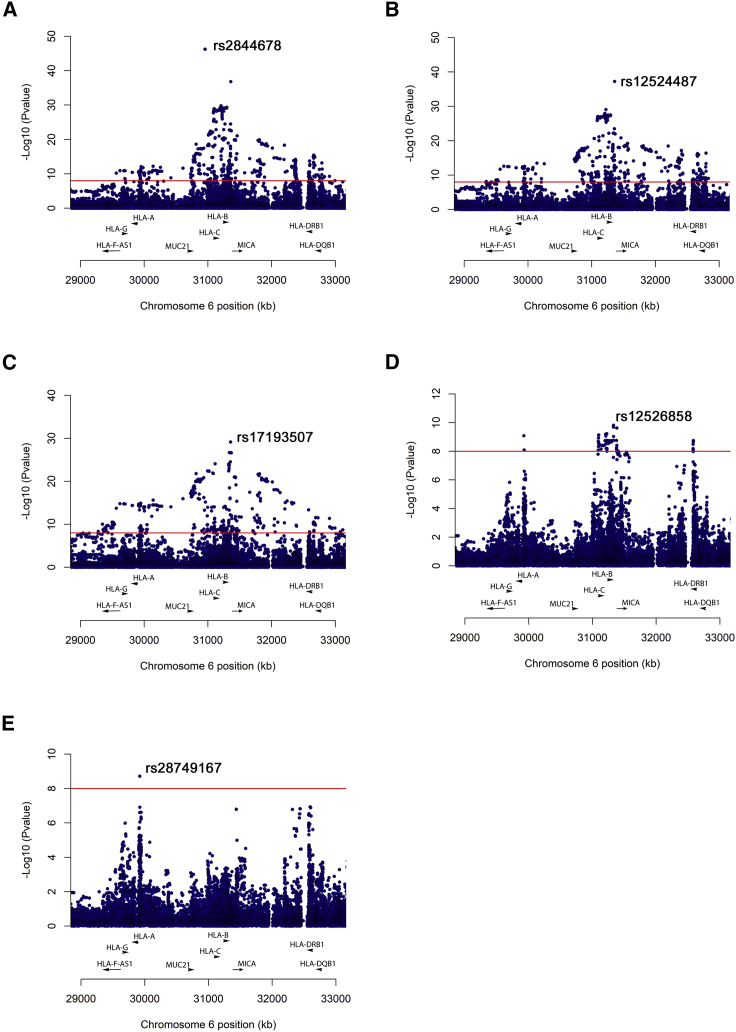

To further evaluate the HLA association with Takayasu arteritis, we first conducted a stepwise conditional analysis of more than 60,000 SNPs located in the extended HLA region (chr6: 20 to 40 Mb). As shown in Figure 2, five SNPs were identified as independent associations with Takayasu arteritis (p value < 5 × 10−8). The strongest effect corresponds with several polymorphisms in complete LD located 5′ of MUC21 (index SNP: rs2844678, p value = 5.70 × 10−47; OR = 2.71). In addition, two intergenic SNPs located between HLA-B and MICA (rs12524487, p value = 5.72 × 10−38, OR = 3.12; rs17193507, p value = 7.08 × 10−30, OR = 3.28), the SNP rs12526858 within HLA-B (p value = 1.55 × 10−10, OR = 2.70) and the SNP rs28749167 located in the non-classical HLA-G gene (p value = 1.90 × 10−9, OR = 1.43), were identified as independent risk factors. Detailed results are displayed in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Manhattan plots showing the results of stepwise conditional analysis of the HLA region

(A) Unconditioned.

(B) Conditioning on rs2844678.

(C) Conditioning on rs2844678 + rs12524487.

(D) Conditioning on rs2844678 + rs12524487 + rs17193507.

(E) Conditioning on rs2844678 + rs12524487 + rs17193507 + rs12526858.

The −log10 p value for the genetic variants analyzed are plotted against their physical chromosomal position. The red line represents the genome-wide level of significance (p value < 5 × 10−8).

Table 1.

Stepwise conditional analysis of the HLA variants and the imputed classical HLA alleles to detect independent associations with Takayasu arteritis

| Covariates | Risk factor | p value | OR | Position (HG19) | Locus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNPs | |||||

| none | rs2844678 | 5.70E−47 | 2.71 | 30950050 | 5′ MUC21 |

| rs2844678 | rs12524487 | 5.72E−38 | 3.12 | 31354238 | HLA-B/MICA |

| rs2844678 + rs12524487 | rs17193507 | 7.08E−30 | 3.28 | 31351054 | HLA-B/MICA |

| rs2844678 + rs12524487 + rs17193507 | rs12526858 | 1.55E−10 | 2.70 | 31323721 | HLA-B |

| rs2844678 + rs12524487 + rs17193507 + rs12526858 | rs28749167 | 1.90E−9 | 1.43 | 29921034 | HLA-G |

| Classical alleles | |||||

| none | HLA-B∗5201 | 4.16E−36 | 4.37 | N/A | N/A |

| HLA-B∗5201 | HLA-B∗1302 | 2.96E−25 | 3.21 | N/A | N/A |

| HLA-B∗5201 + HLA-B∗1302 | HLA-B∗1501 | 1.09E−15 | 3.07 | N/A | N/A |

| HLA-B∗5201 + HLA-B∗1302 + HLA-B∗1501 | HLA-DQB1∗0502 | 3.88E−8 | 1.90 | N/A | N/A |

Abbreviations are as follows: SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; OR, odds ratio.

Next, we imputed the HLA classical alleles to determine their association with Takayasu arteritis. Consistent with the previous knowledge, the HLA-B∗52:01 (p value = 4.16 × 10−36, OR = 4.37) showed the strongest association among all markers. The results of the conditional logistic regressions detected independent associations surpassing the genome-wide level of significance of other class I and class II HLA alleles are as follows: HLA-B∗13:02, p value = 2.96 × 10−25, OR = 3.21; HLA-B∗15:01, p value = 1.09 × 10−15, OR = 3.07; HLA-DQB1∗05:02, p value = 3.88 × 10−8, OR = 1.90. To determine the relationship between the HLA variants and the classical alleles, we performed conditional regression analysis (Table S4). We can observe that some signals, even though they remained significant, showed an attenuated effect after adjusting for other markers, as is the case of HLA-B∗5201-rs12524487, HLA-B∗15:01-rs12524487, and HLA-B∗15:01-rs28479167. These results suggest that we cannot rule out an independent effect for these markers in Takayasu arteritis. In contrast, the association of rs12526858 was completely abrogated by conditioning on HLA-B∗15:01, which indicates that the association of this variant relies on the association of the classical allele.

Finally, we also evaluated each population independently (Table S5). Interestingly, some SNPs located in other non-classical HLA genes were identified associated at a genome-wide level of significance in specific populations. These include a variant located in PSORS1C1 in the Turkish population (rs61444472, p value = 2.37 × 10−17), a polymorphism within HLA-V in the Northern European descendant population (rs45479291, p value = 1.92 × 10−16), and rs1264697 (p value = 1.33 × 10−8) located near TRIM31 in the Chinese population.

Outside of the HLA, 41 SNPs shared between at least two independent populations surpassed the genome-wide level of significance (p value < 5 × 10−8), showing no OR heterogeneity among populations (Table S6). These variants were located within seven genomic regions, four of which corresponded with previously unreported Takayasu arteritis-associated loci. The most significant variants within each genomic region are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Meta-analysis results showing the most significant genetic variant in each locus associated with Takayasu arteritis at a genome-wide level of significance (p value < 5E−8)

| Locus | Chr | Position (HG19) | SNP | Location | Minor allele | p value | OR | Q statistic p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VPS8a | 3 | 184612321 | rs58693904 | intronic | T | 3.73E−9 | 1.51 | 0.550 |

| IL12B | 5 | 158804928 | rs4379175 | upstream | T | 3.13E−9 | 1.36 | 0.173 |

| PTK2B | 8 | 27195121 | rs28834970 | intronic | C | 1.40E−9 | 0.71 | 0.957 |

| SVEP1a | 9 | 113117183 | rs7038415 | upstream | A | 4.90E−8 | 1.45 | 0.174 |

| chr13q21a | 13 | 65078467 | rs9540128 | intergenic | T | 1.89E−8 | 2.02 | 0.793 |

| CFL2a | 14 | 35189914 | rs76457959 | upstream | T | 2.84E−9 | 1.62 | 0.682 |

| chr21q22 | 21 | 40464924 | rs4817983 | intergenic | C | 1.92E−12 | 0.64 | 0.125 |

Abbreviations are as follows: Chr, chromosome; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; OR, odds ratio.

Novel previously unreported genetic loci in Takayasu arteritis.

We detected evidence of association with a genetic variant located upstream of SVEP1 (sushi Von Willebrand factor type A, EGF And pentraxin domain containing 1) (rs7038415, p value = 4.90 × 10−8, OR = 1.45) and a variant upstream of CFL2 (cofilin 2) (rs76457959, p value = 2.84 × 10−9, OR = 1.62). Notably, these genes have been associated with coronary disease and atrial fibrillation, respectively.34, 35, 36, 37 We also identified a genetic association within VPS8 (rs58693904, p value = 3.73 × 10−9, OR = 1.51), which encodes the VPS8 subunit of the CORVET complex and is involved in vesicle-mediated protein trafficking.38 In addition, we identified a genetic association with an intergenic variant located in chr13q21 (rs9540128, p value = 1.89 × 10−8, OR = 2.02). None of these variants showed high LD with any other genotyped or imputed SNPs (Figure S4).

Along with the previously unreported identified genetic susceptibility loci for Takayasu arteritis, our findings also reinforced the association of three previously reported loci. The strongest effect after the HLA region corresponded with chr21q22 (rs4817983, p value = 1.92 × 10−12, OR = 0.64). This intergenic region was first described in Turkish and European-American populations and was replicated later in the Japanese population.6,9 We confirmed and extended this genetic association to Takayasu arteritis in Han Chinese and Italian cohorts (p value = 8.32 × 10−3, OR = 0.47 and p value = 2.98 × 10−4, OR = 0.33, respectively). Although the results for the South Asian cohort were not statistically significant, a consistent OR direction was detected. Furthermore, our results validated the association of IL12B (interleukin 12B) (rs4379175, p value = 3.13 × 10−9, OR = 1.36) and PTK2B (protein tyrosine kinase 2 beta) (rs28834970, p value = 1.40 × 10−9, OR = 0.71) with homogeneity across all five cohorts. A nominal association was observed in Han Chinese population for both genes. These results further establish the association of these loci with Takayasu arteritis and provide evidence of a common genetic background among different ancestral groups. Finally, the high LD structure among the identified GWAS-level SNPs restrained the localization to a single genetic variant in any of these three genomic regions (regional plots are shown in Figure S4).

In addition, 308 SNPs corresponding to 66 genomic regions (including PTK2B and chr21q22 loci) showed suggestive evidence of association with Takayasu arteritis (p value ≤ 5 X 10−5) (Table S7). It should be noted that some of these loci have been related to other IMDs, such as PLCG2 (phospholipase C gamma 2) with inflammatory bowel disease, RBPJ (recombination signal-binding protein for immunoglobulin kappa J region) with rheumatoid arthritis, or ZMIZ1 (zinc finger MIZ-type containing 1) with Crohn disease, among others.39, 40, 41 Interestingly, a cross-phenotype analysis of systemic vasculitis suggested ZMIZ1 as a shared risk factor.42 Other promising candidate genes are CCR7 (C-C motif chemokine receptor 7) and RGS6 (regulator of G protein signaling 6).

Finally, we checked the known GWAS-level variants associated with Takayasu arteritis in our meta-analysis. Detailed data are shown in Table S8. Briefly, the variants identified in KLHL33 and LILRB3 were not included in our meta-analysis because of inability to impute or low-quality imputation, respectively. The results of our meta-analysis showed significant associations in a FCGR2A/FCGR3A variant (rs10919543, p value = 2.68 × 10−3, OR = 1.45) and a DUSP22 variant (rs17133698, p value = 4.89 × 10−3, OR = 0.64), consistent with previous studies. It should be noted that the variant in FCGR2A/FCGR3A was not evaluated in the Turkish and Northern European descendant populations in this study and, similarly, the SNP in DUSP22 was filtered out (MAF < 1%) in our Northern European descendant and Italian populations. We detected an association in the SNP reported in IL6 (rs2069837, p value = 2.05 × 10−2, OR = 0.84), but interestingly, we find that ORs directions in this locus are different across populations. Finally, the variant rs103294, which is located in LILRA3 and was reported previously in a Japanese cohort, showed no tendency of association in the meta-analysis (this variant only passed the QC in Turkish and Italian populations) but was found to be associated in our Turkish cohort (p value = 9.36 × 10−9, OR = 1.66).

Functional annotations and epigenetic enrichment analysis of genome-wide associated SNPs

In line with most of the genetic susceptibility loci detected in IMDs, Takayasu arteritis-associated genetic variants reside in non-coding regions, suggesting that they might influence the disease by disrupting regulatory elements. To assign biological significance to those variants, we carried out a comprehensive functional annotation by using in silico approaches.

First, we evaluated the regulatory potential of disease-associated variants reported with a GWAS level of significance in our study (p value < 5 × 10−8). Epigenetic annotation indicates that most of these variants co-localize with epigenetic marks and, therefore, most likely contribute to chromatin states across multiple primary tissues and cells (Table S9). We found that 85% of variants may alter regulatory motifs and, therefore, might disrupt TF binding. DNase hypersensitivity sites were also observed in 44% of the variants analyzed. Finally, protein binding was identified in some of these variants. For example, in lymphoblastoid cell lines, a Takayasu arteritis-associated genetic variant in PTK2B, rs755951, is located in a binding site for CTCF, and binding of PU.1 was detected in at least two disease-associated variants in chr21q22.

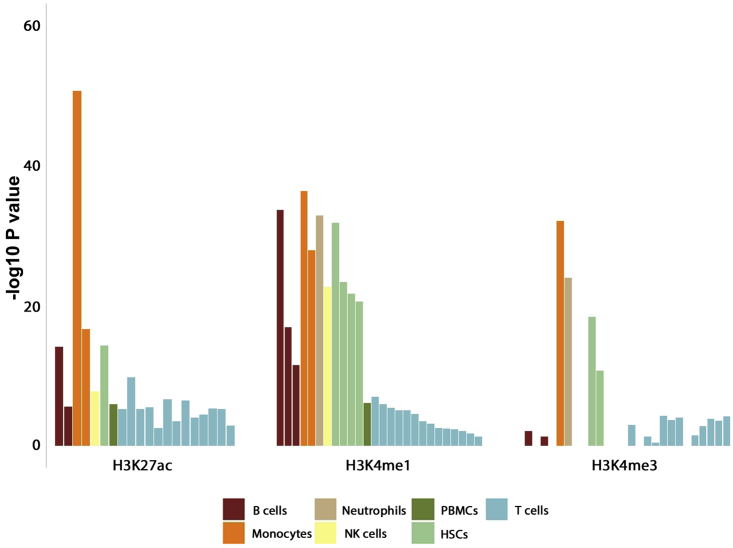

Because most of the associated variants co-localize with epigenetic features, we performed a regulatory enrichment analysis to evaluate whether the presence of epigenetic marks at these loci was more frequent than expected by chance and to determine the specific cell subsets that are more likely to be affected by these genetic variants. We analyzed seven different histone marks (H3K4me1, H3K4me2, H3K4me3, H3K9ac, H3K27ac, H3K27me3, and H3K9me3) across 127 reference epigenomes. Of 889 combinations of regulatory features and tissues examined, we found 170 associated enrichments in 86 cell types/tissues (Table S10). Most epigenetic mark enrichment patterns were observed in blood cells, which include a wide repertoire of immune cells. In agreement with our current understanding of the immunopathology of Takayasu arteritis, the most significant enrichments were observed in monocytes (Figure 3). Our results showed enrichment of H3K27ac (p value = 2.58 × 10−51), H3K4me1 (p value = 5.43 × 10−37), H3K9ac (p value = 3.80 × 10−21), H3Kme2 (p value = 2.22 × 10−26), and H3K4me3 (p value = 1.03 × 10−32) in primary human monocytes. Three specific B cell lines presented strong enrichments as well, including primary B cells from cord blood (H3K4me1, p value = 5.43 × 10−37; H3K4me3, p value = 1.20 × 10−32), primary B cells from peripheral blood (H3K27ac, p value = 5.22 × 10−15; H3K4me1, p value = 3.02 × 10−17), and GM12878 lymphoblastoid cells (H3K27ac, p value = 2.59 × 10−6; H3K9ac, p value = 7.61 × 10−6; H3K9me3, p value = 2.02 × 10−7; H3K4me2, p value = 6.68 × 10−6; H3K4me1, p value = 3.22 × 10−12; H3K4me3, p value = 4.89 × 10−2). Other robust epigenetic mark co-localizations were also detected in other immune cells, such as neutrophils, natural killer cells, and T cell subsets, and in other tissues, such as the heart and digestive tissues.

Figure 3.

Column bar plot representing the results from histone marks enrichment analysis among genetic susceptibility loci identified with a GWAS level of significance (p value < 5 × 10−8) in Takayasu arteritis in this study

The y axis corresponds with the −log10 corrected p value of H3K27ac, H3K4me1, and H3K4me3 enrichments in different blood cell types. These data were derived via ENCODE and Roadmap Epigenomics Consortium projects. PBMCs, peripheral blood mononuclear cells; HSCs, hematopoietic stem cells.

Given that epigenetic marks may correlate with gene expression changes, we examined several public repositories of eQTLs to explore the relationship between gene expression and genetic variants associated with Takayasu arteritis. We found that 78% of variants detected with a GWAS level of significance in our study have been linked to altered expression of at least one gene in multiple tissues and/or cell types (Table S11). Takayasu arteritis-associated variants in PTK2B are associated with expression changes of several genes in whole blood, lymphoblastoid cell lines, monocytes, and left ventricular heart tissue, among others. Notably, the disease risk alleles in PTK2B are associated with reduced expression of PTK2B. Furthermore, these polymorphisms also alter the expression levels of PTK2B isoforms, acting as splicing QTLs. In addition, Takayasu arteritis susceptibility variants in PTK2B are associated with altered expression levels of other genes, such as DPYSL2 (dihydropyrimidinase-like 2) in lymphoblastoid cell lines, EPHX2 (epoxide hydrolase 2) in tibial artery tissue, and CHRNA2 (cholinergic receptor nicotinic alpha 2 subunit) and TRIM35 (tripartite motif-containing 35) in whole blood. Takayasu arteritis-associated variants upstream of IL12B change the expression of UBLCP1 (ubiquitin-like domain-containing CTD phosphatase 1) in whole blood, and those in the intergenic region chr21q22 alter the expression of several genes, including ETS2 (ETS proto-oncogene 2, transcription factor) and LCA5L (lebercilin LCA5 like).

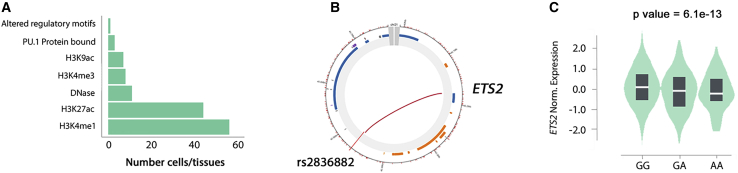

Under the assumption that chromatin architecture might influence transcriptional regulation, we used the CHiCP webtool to detect and visualize physical chromatin interactions between Takayasu arteritis-associated variants and gene promoter regions across multiple cell types.25 The vast majority of examined variants showed multiple interactions in different cell types, and several of them interact with the promoters of genes whose expression levels were affected (Table S11 and Figure S5). It is worth highlighting the physical interaction between variants in the chr21q22 locus and ETS2 promoter in multiple immune cells, such as monocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils. The functional relevance of this interaction is supported by the above mentioned eQTL results. Altogether, these findings pinpointed ETS2 as a potential target gene for Takayasu arteritis influenced by the disease susceptibility locus in chr21q22 (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Functional annotation results point to ETS2 as a causal gene for the chr21q22 association

(A) Summary of the epigenetic marks found at rs2836882 in chr21q22.

(B) Circular view of the chromatic interaction between rs2836882 in chr21q22 and the ETS2 promoter obtained from Capture Hi-C data. This interaction is observed in several cell types: endothelial precursors, megakaryocytes, monocytes, M0 macrophages, M1 macrophages, M2 macrophages, neutrophils, and CD34+ cells. The red color of the line indicates a strong confidence for this interaction.

(C) Violin plot representing the difference in expression levels of ETS2 depending on rs2836882 genotypes obtained from GTEx project.

Pathway analysis

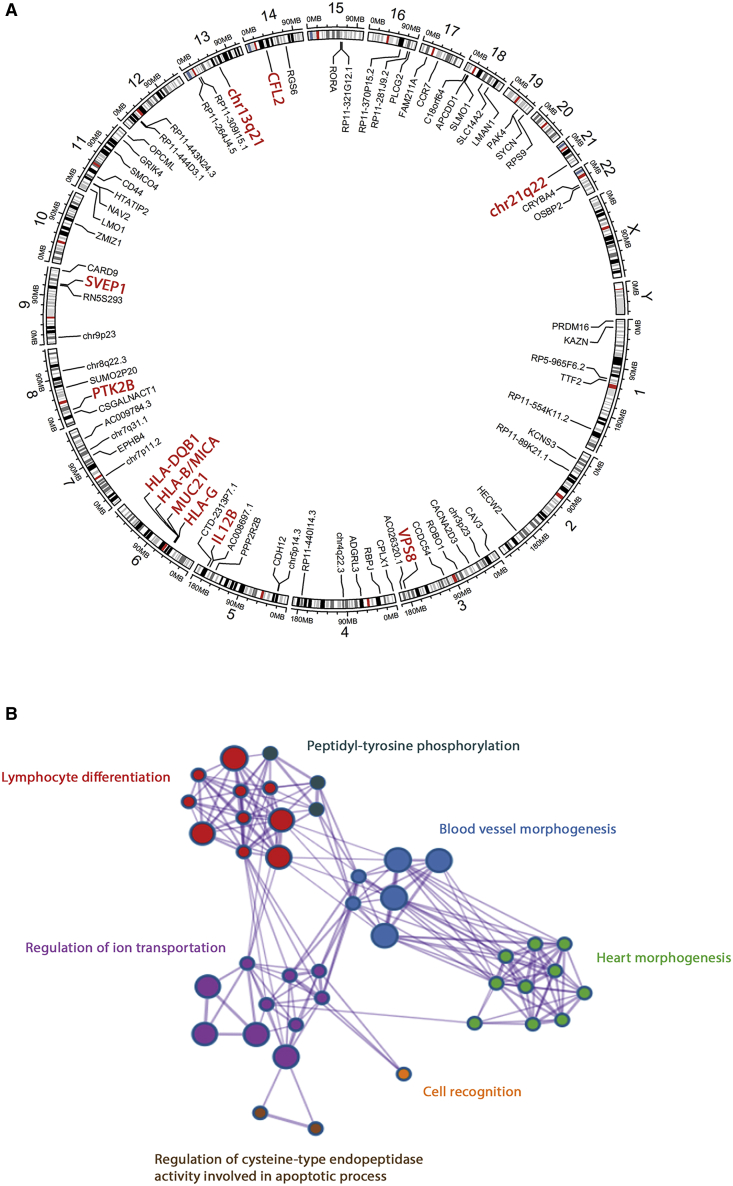

To highlight biological processes that might be relevant in the pathogenesis of Takayasu arteritis, we performed a GO term enrichment analysis by using all genes annotated to genetic variants with at least a suggestive level of association with Takayasu arteritis in our study (p value < 5 × 10−5). Given that ontologies are often redundant, the results from these analyses commonly reveal related and even overlapping terms. To simplify their interpretation, we clustered GO terms by their similarities, revealing seven different clusters: lymphocyte differentiation (p value = 3.23 × 10−6), blood vessel morphogenesis (p value = 2.80 × 10−5), heart morphogenesis (p value = 1.07 × 10−4), regulation of ion transmembrane transport (p value = 2.30 × 10−4), cell recognition (p value = 6.38 × 10−4), peptidyl-tyrosine phosphorylation (p value = 4.29 × 10−3), and regulation of cysteine-type endopeptidase activity involved in apoptotic process (p value = 7.05 × 10−3) (Figure 5). A detailed list of all GO terms showing included genes is displayed in Table S12.

Figure 5.

Takayasu arteritis genetic susceptibility loci identified and the main Gene Ontology terms represented

(A) Schematic illustration depicting the susceptibility loci identified in this study. Loci surpassing the genome-wide level of significance (p value < 5 × 10−8) are highlighted in red.

(B) Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis. Biological Process GO clusters revealed with genes annotated to genetic susceptibility loci identified in this study (p value < 5 × 10−5). Only clusters detected with a p value < 1 × 10−3 and that included at least three genes are shown. Each node corresponds with a GO term, and edges represent connections between GO terms. Each GO cluster is defined by a different color and the most-associated Biological Process within each cluster is highlighted.

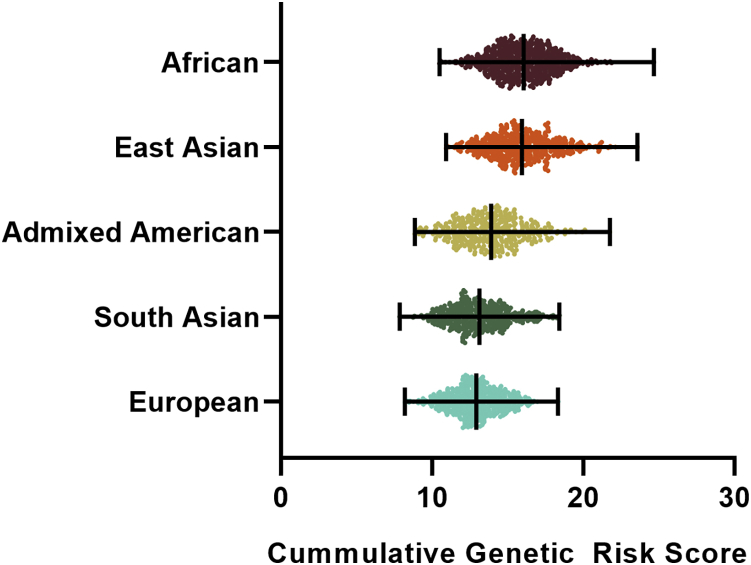

Cumulative GRS

To investigate if the diversity of Takayasu arteritis prevalence among ancestries may have genetic bases, we assessed the cumulative GRS of more than 2,500 individuals from the five major populations included in the 1000 Genomes project and tested whether mean GRS differences across populations exist. The GRS values are illustrated in Figure 6. There was a significant difference between the GRSs among populations (ANOVA p value < 0.0001). The highest GRSs were observed in African and East Asian populations, whereas European and South Asian populations showed the lowest values. The multiple comparison test on mean GRS between each pair of populations revealed statistically significant differences for all pairs except African versus East Asian and European versus South Asian (Tukey’s adjusted p value = 0.924 and 0.457, respectively).

Figure 6.

Dot plot representing the cumulative genetic risk score (GRS) for Takayasu arteritis across the five major populations included in the 1000 Genomes Project

Each dot illustrates the GRS value of an individual, and the black lines represent the means and ranges. Data were used from the 1000 Genomes Project phase 3 release. African, n = 661; Admixed American, n = 347; East Asian, n = 504; European, n = 503; South Asian, n = 489. There was a significant difference between the GRSs among populations (ANOVA p value < 0.0001). The multiple comparison test on mean GRS between each pair of populations revealed statistically significant differences for all pairs (p value < 0.0001) except African versus East Asian and European versus South Asian (Tukey’s adjusted p value = 0.924 and 0.457, respectively).

Takayasu arteritis genetic relationship with multiple IMDs

Relating different diseases through their GWAS summary statistics has been used to reveal etiological relationships between diseases. We chose to compare Takayasu arteritis to other IMDs through projecting it into a previously constructed lower-dimensional representation of IMD genetics, an “IMD basis.”33 This representation uses 13 components to summarize axes of risk shared between different combinations of diseases. We found Takayasu arteritis differed significantly (FDR < 1%) from controls on eight of the 13 components, five of which were also associated with Crohn disease and/or ulcerative colitis. In the original report of the IMD basis, relationships between different IMD GWASs and self-reported disease traits in European UK Biobank subjects were inferred from hierarchical clustering of their projections, and we reclustered the same set of traits here together with Takayasu arteritis to examine with which IMDs it shared genetic risk components. We found that Takayasu arteritis clustered with Crohn disease, ulcerative colitis, and ankylosing spondylitis (Figure S6). However, clustering across multiple dimensions can be sensitive to choices of algorithm, and although the method appears robust to different ancestries (because it is based on summary ORs that have been calculated with appropriate ancestry adjustment), we also wanted to confirm this was not an effect of comparing to European subjects. We therefore also compared Takayasu arteritis to projections of all diseases in two large cohorts (FinnGen and all UK Biobank subjects including non-Europeans) by using a one-dimensional summary, the Mahalanobis distance (see Subjects and methods). This found that in both cohorts, Crohn disease was the closest genetically to Takayasu arteritis, followed by ulcerative colitis, out of the hundreds of traits considered (Figure S7).

Discussion

We report the results of a large genetic association study in Takayasu arteritis using affected individuals and control individuals from five diverse populations. In addition to the well-known HLA-B∗52 association, we detected several independent signals within the HLA region and characterized four non-HLA loci that confer genetic susceptibility in Takayasu arteritis with a GWAS level of significance (SVEP1, CFL2, VPS8, and chr13q21). Further, we identified >60 genetic loci with a suggestive level of association with the disease.

Consistent with our current knowledge of the disease, the strongest association signals were observed within the HLA region. Multiples studies have previously analyzed the association of this region with Takayasu arteritis, confirming HLA-B∗52:01 as a robust genetic factor in several ancestries. Other HLA classical alleles (class I and class II) and variants along the extended HLA region have also been identified in specific populations. However, the complex LD structure of this region and the low statistical power of most of these studies have limited the localization of the specific effects and the identification of new susceptibility loci at a GWAS level of significance.4 Here, we report five variants showing independent associations with the disease; three are located near the well-known susceptibility locus HLA-B (rs12524487-HLA-B/MICA, rs17193507-HLA-B/MICA, and rs12526858-HLA-B), and the other two variants (rs2844678-MUC21 and rs28749167-HLA-G) might indicate previously unreported risk loci for Takayasu arteritis. In addition, four independent HLA classical alleles were identified as susceptibility factors for Takayasu arteritis (HLA-B∗52:01, HLA-B∗13:02, HLA-B∗15:01, and HLA-DQB1∗05:02). Conditional regression analysis revealed that the association in rs12526858 is dependent on HLA-B∗15:01. Our results also suggested a genetic relationship among the HLA-B variants and the HLA-B classical alleles, but independent effect on the disease etiology cannot be discarded. Although our data strongly suggest additional effects exist beyond HLA-B∗52:01 in Takayasu arteritis, further studies are needed to functionally characterize these complex effects.

Of interest, giant cell arteritis, which is another large vessel vasculitis that can present with clinical and angiographic findings that are sometimes similar to Takayasu arteritis, appears to be associated with a distinctly different genetic susceptibility within the HLA region. Unlike Takayasu arteritis, the most robust genetic association in giant cell arteritis is within the HLA class II region.43

The strongest association outside the HLA region corresponds with SVEP1, which encodes a cell-adhesion molecule also known as Polydom.44 This protein acts as a ligand for integrin α9β1, which has been recently described to play an important role in the development of autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis.45,46 In this context, Polydom is necessary for lymphatic vessel remodeling, a process that is involved in immune cell trafficking and surveillance.47 In addition, silencing SVEP1 in endothelial cell lines was associated with increased expression of key molecules involved in endothelial cell-leukocyte adhesion, including interleukin-8 (IL-8), growth-regulated oncogene-α (GRO-α), monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1), and monocyte chemoattractant protein 3 (MCP-3).48 Furthermore, SVEP1 polymorphisms have been also associated with cardiovascular conditions such as increased risk of coronary disease and blood pressure.35, 36, 37,49

Cofilin 2 (CFL2) encodes an actin-binding protein that is a key regulator of actin dynamics.50 It has been shown that the actin cytoskeleton and its regulators play an important role in T cell-B cell interaction.51 A related gene family member, cofilin, is involved in the clustering of T cell receptors during T cell activation through actin reorganization.52 In addition, previous studies reported associations between CFL2 and atrial fibrillation, and mutations in this gene have been described in individuals with congenital myopathy.34,53,54

In contrast, VPS8 and chr13q21 loci have not been previously associated with any related disease. VPS8 encodes a vacuolar protein involved in vesicular-mediated protein trafficking. A protein-protein interaction analysis with the STRING webtool55 revealed other related vacuolar proteins that have been associated with cardiovascular disease. For example, polymorphisms in VPS33B are associated with hypertension and myocardial infarction in Japanese individuals.56

With regard to the four “novel” genetic association signals we identified in Takayasu arteritis, it should be noted that no additional variants in strong LD (r2 > 0.6) with any of the associated variants were identified in our study and that we did not detect clear functional implications of the identified polymorphisms on the pathophysiology of the disease. These variants might disrupt regulatory elements in a cell type-specific context or might tag unidentified genetic variants that could be responsible for the causality of these associations. Replication and fine-mapping studies in independent populations followed by functional studies should be conducted to confirm and characterize the functional consequences of these novel genetic susceptibility loci in Takayasu arteritis.

The results of our multi-ancestral approach also extended the genetic associations of PTK2B, IL12B, and a locus on chr21q22 to other populations. Of interest, these genetic associations are examples of shared risk loci among different IMDs. The rs17057051 polymorphism in PTK2B has been previously reported as a genetic susceptibility factor in inflammatory bowel disease.57 The genetic effect in this SNP, which is in strong LD (r2 > 0.8) with the lead PTK2B variant associated with Takayasu arteritis in our study, is in the same direction in both disease conditions. The polymorphisms rs6556412 and rs4379175, upstream of IL12B, have been associated with inflammatory bowel disease and psoriasis, respectively.57, 58, 59 Interestingly, while the direction of the genetic effect in this locus is similar in Takayasu arteritis and inflammatory bowel disease, it appears that the risk allele in rs4379175-IL12B in Takayasu arteritis is protective against psoriasis. Finally, the genetic region chr21q22 has also been reported to be associated with ankylosing spondylitis and inflammatory bowel disease57,60,61 and with a genetic effect in the same direction as we report in Takayasu arteritis.

PTK2B encodes a tyrosine kinase, PYK2, which is expressed in multiple cell types, including immune cells. Indeed, experiments in mice showed that deficiency in Pyk-2 leads to abnormal function of marginal zone B cells.62 In agreement with results published in a Japanese cohort,9 we observed that the minor alleles of disease-associated SNPs in PTK2B are protective and are associated with increased expression of PTK2B in different tissues. Furthermore, these SNPs are linked with the expression of different isoforms of PTK2B. One causal variant, rs2322599, was proposed in the Japanese study, however, a total of ten SNPs (including rs2322599) surpassed the GWAS level of significance in our meta-analysis. No single variant could be identified as causal given the high LD in this region and the broad epigenetic enrichment patterns involving these variants. Importantly, disease-associated variants in PTK2B are also associated with gene expression changes involving other genes in this locus, such as DPYSL2, EPHX2, CHRNA2, and TRIM35. In this context, we cannot rule out that these other genes might also play a role in Takayasu arteritis. Indeed, chromatin interaction was revealed between disease-associated variants in PTK2B and promoter regions of EPHX2 and CHRNA2. Interestingly, the PTK2B variant rs755951 is located in a CTCF binding site, suggesting the involvement of this Takayasu arteritis risk variant in long-range chromatin interactions.

Epigenomic annotation, chromatin interaction maps, and eQTL analysis also revealed the possible regulatory mechanisms underlying the genetic association between Takayasu arteritis and IL12B. Our data identified UBLCP1 as a possible target gene affected by this genetic association. In whole blood, almost all Takayasu arteritis-associated variants in IL12B alter UBLCP1 mRNA expression. Interestingly, UBLCP1 has been found to be associated with increased genetic risk in psoriasis.63

Among findings from functional annotation analyses in the genetic risk locus in the chr21q22 region, it should be highlighted that PU.1 protein binding was detected in this locus in ENCODE ChIP-seq experiments. PU.1 is a TF member of the Ets family and is required for hematopoietic development.64 Mice deficient in Pu.1 showed a lack of mature B cells and macrophages.65 Our eQTL analysis of Takayasu arteritis risk variants in this locus revealed higher expression of ETS2 in whole blood, and Hi-C data showed chromatin interaction between these variants and ETS2 promoters in monocytes and macrophages, among other immune cell types. ETS2 also encodes a member of the Ets family with a key role in macrophage development. Recently, experimental data confirmed the functional synergy between Ets2 and PU.1 to activate the transcription of bcl-x, which encodes Bcl-xL, a necessary protein for macrophage survival.66 Interestingly, another member of the Ets family, ETS1, has been identified as a susceptibility risk locus for other IMDs, such as lupus and inflammatory bowel disease.67,68

The finding of enrichment in active chromatin epigenetic marks among the identified Takayasu arteritis risk loci was consistent with our understanding of the disease, reflecting a robust immunological signature. Specifically, monocytes and B cells presented the highest enrichment patterns. Monocytes and macrophages are thought to play a crucial role in the pathophysiology of large vessel vasculitis, including Takayasu arteritis.69 Although the role of B cells in Takayasu arteritis is less clear, a seemingly successful response to rituximab treatment in some affected individuals, the presence of tissue infiltrating B cells in affected arteries, higher frequency of circulating plasmablasts, and the presence of anti-endothelial cell antibodies in individuals diagnosed with Takayasu arteritis point to a possible role for B cells in this disease.70,71 Our analysis also identified other important immune cell types implicated in the pathophysiology of this form of vasculitis, including T cell subsets and NK cells, the latter of which is consistent with results from enrichment analysis in a recent report.9 We also revealed enrichment patterns across non-immune-related tissues. In agreement with the pathophysiology of Takayasu arteritis, several heart-related tissue types were detected. The enrichments found in digestive tissues could be explained by a plausible genetic overlap between Takayasu arteritis and inflammatory bowel disease and an observed higher prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in individuals diagnosed with Takayasu arteritis.72,73 This is also supported by our data projecting the genetic component of multiple IMDs in which Takayasu arteritis was found to cluster with Crohn disease, ulcerative colitis, and ankylosing spondylitis.

The most significant biological process identified among genetic risk loci detected in our study was lymphocyte differentiation, which includes key specific pathways such as leukocyte differentiation, T cell activation, inflammatory response to antigenic stimulus, and cytokine production, among others. Along with the disease-associated loci in IL12B and PTK2B, other genetic loci with suggestive association, such as CCR7, RBPJ, PLCG2, RORA, ZMIZ1, CD44, LMO1, and CARD9, are included in these pathways. Among these genes, PLCG2 has been associated with inflammatory bowel disease, RBPJ has been associated with rheumatoid arthritis, and ZMIZ1 has been associated with Crohn disease.39, 40, 41 Genes in blood vessel and heart morphogenesis pathways were also observed. These include CFL2 and SVEP1 and several genes with a suggestive level of association, such as EPHB4 and PRDM16, which are risk loci for inflammatory bowel disease and rheumatoid arthritis, respectively.57,74

The cumulative GRSs, which is a simple and intuitive approach to convert genetic data into a predictive measure of disease susceptibility, suggest that the differences in Takayasu arteritis prevalence have genetic bases. Although the GRS value of the African population was higher than expected, the data were in line with Takayasu prevalence described to date, being the highest in East Asia, Mexico, and South East Asia.3 Epidemiological data of Takayasu arteritis in African populations are scarce. However, a recent review analyzing the current state of systemic vasculitis in Africa concluded that these pathologies might be under-diagnosed.75 Another plausible explanation for these results might be the existence of unidentified protective genetic effects against Takayasu arteritis in African populations. It should be noted that these results should be interpreted as estimates based on our current knowledge of the genetic component of Takayasu arteritis. The accuracy of our estimations could be limited given that the ORs of the associated signals might vary among populations. Further, additional genetic loci involved in Takayasu arteritis remain to be identified in currently studied and additional populations.

Finally, genetic studies have been successful in proposing new molecular targets for drug discovery.76 In this regard, the potential of IL12B as a drug target for Takayasu arteritis has been revealed by genetic studies. Furthermore, it is worth mentioning that PYK2, EST2, and the SVEP1-integrin interaction might represent promising drug targets for Takayasu arteritis. Indeed, natalizumab, an anti-α4 integrin antibody, has already shown beneficial therapeutic effects in multiple sclerosis and Crohn disease.77,78 Leflunomide, which is a PYK2 antagonist used to treat rheumatoid arthritis,79 has also been investigated in other large vessel vasculitides, including Takayasu arteritis and giant cell arteritis.80, 81, 82

In summary, we performed a large multi-ancestral GWAS in Takayasu arteritis. We revealed risk factors within the HLA region and four non-HLA genetic associations with a GWAS level of significance, extended the genetic association of previously reported risk loci to other populations, and uncovered over 60 additional candidate genetic susceptibility loci for the disease. Using functional and epigenetic enrichment characterization, we identified pathways, biological processes, and target genes affected by these genetic risk loci. Our results also suggest a close genetic relationship between Takayasu arteritis and inflammatory bowel diseases. Finally, the results of this work highlight immune cell types that are crucial in mediating genetic risk in Takayasu arteritis.

Data and Code Availability

Summary statistics of the meta-analysis are available and can be provided upon reasonable request. The code to reproduce the comparison figures of the genetic relationship among immune-mediated diseases analyses is available from https://github.com/chr1swallace/tak-basis. The rest of the data/code used in this study are included in the main manuscript or its supplementary material.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health grant R01 AR070148 to A.H.S. The Vasculitis Clinical Research Consortium has received support from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (U54 AR057319 and U01 AR51874 04), the National Center for Research Resources (U54 RR019497), and the Office of Rare Diseases Research of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. J.C.M., A.P.K., and R.M.M. acknowledge support from the Imperial College, National Institute for Health Research, Biomedical Research Centre. C.W. and G.R. acknowledge support from The Wellcome Trust (WT107881) and the Medical Research Council (MC_UU_00002/4). This work was supported by the use of study data downloaded from the dbGaP website, under dbGaP: phs000272.v1.p1, phs000431.v2.p1, phs000583.v1.p1, and phs000444.v1.p1.

Published: December 11, 2020

Footnotes

Supplemental Data can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2020.11.014.

Web resources

Capture Hi-C plotter (CHiCP), https://www.chicp.org/chicp/

Cupcake R package, https://github.com/ollyburren/cupcake

ENCODE, https://www.encodeproject.org/

FinnGen, https://www.finngen.fi/fi

HLA∗IMP:03 v.0.1.0, http://imp.science.unimelb.edu.au/hla/instructions

Roadmap Epigenomics Consortium, http://www.roadmapepigenomics.org/

UK Biobank, http://www.nealelab.is/uk-biobank/

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Jennette J.C., Falk R.J., Bacon P.A., Basu N., Cid M.C., Ferrario F., Flores-Suarez L.F., Gross W.L., Guillevin L., Hagen E.C. 2012 revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference Nomenclature of Vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:1–11. doi: 10.1002/art.37715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Souza A.W., de Carvalho J.F. Diagnostic and classification criteria of Takayasu arteritis. J. Autoimmun. 2014;48-49:79–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2014.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnston S.L., Lock R.J., Gompels M.M. Takayasu arteritis: a review. J. Clin. Pathol. 2002;55:481–486. doi: 10.1136/jcp.55.7.481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Renauer P., Sawalha A.H. The genetics of Takayasu arteritis. Presse Med. 2017;46:e179–e187. doi: 10.1016/j.lpm.2016.11.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirsch M.S., Aikat B.K., Basu A.K. Takayasu’s Arteritis. Report of Five Cases with Immunologic Studies. Bull. Johns Hopkins Hosp. 1964;115:29–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Renauer P.A., Saruhan-Direskeneli G., Coit P., Adler A., Aksu K., Keser G., Alibaz-Oner F., Aydin S.Z., Kamali S., Inanc M. Identification of Susceptibility Loci in IL6, RPS9/LILRB3, and an Intergenic Locus on Chromosome 21q22 in Takayasu Arteritis in a Genome-Wide Association Study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67:1361–1368. doi: 10.1002/art.39035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saruhan-Direskeneli G., Hughes T., Aksu K., Keser G., Coit P., Aydin S.Z., Alibaz-Oner F., Kamalı S., Inanc M., Carette S. Identification of multiple genetic susceptibility loci in Takayasu arteritis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2013;93:298–305. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Terao C., Yoshifuji H., Kimura A., Matsumura T., Ohmura K., Takahashi M., Shimizu M., Kawaguchi T., Chen Z., Naruse T.K. Two susceptibility loci to Takayasu arteritis reveal a synergistic role of the IL12B and HLA-B regions in a Japanese population. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2013;93:289–297. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Terao C., Yoshifuji H., Matsumura T., Naruse T.K., Ishii T., Nakaoka Y., Kirino Y., Matsuo K., Origuchi T., Shimizu M. Genetic determinants and an epistasis of LILRA3 and HLA-B∗52 in Takayasu arteritis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115:13045–13050. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1808850115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arend W.P., Michel B.A., Bloch D.A., Hunder G.G., Calabrese L.H., Edworthy S.M., Fauci A.S., Leavitt R.Y., Lie J.T., Lightfoot R.W., Jr. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of Takayasu arteritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33:1129–1134. doi: 10.1002/art.1780330811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tryka K.A., Hao L., Sturcke A., Jin Y., Wang Z.Y., Ziyabari L., Lee M., Popova N., Sharopova N., Kimura M., Feolo M. NCBI’s Database of Genotypes and Phenotypes: dbGaP. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D975–D979. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Auton A., Brooks L.D., Durbin R.M., Garrison E.P., Kang H.M., Korbel J.O., Marchini J.L., McCarthy S., McVean G.A., Abecasis G.R., 1000 Genomes Project Consortium A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature. 2015;526:68–74. doi: 10.1038/nature15393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang C.C., Chow C.C., Tellier L.C., Vattikuti S., Purcell S.M., Lee J.J. Second-generation PLINK: rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. Gigascience. 2015;4:7. doi: 10.1186/s13742-015-0047-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Das S., Forer L., Schönherr S., Sidore C., Locke A.E., Kwong A., Vrieze S.I., Chew E.Y., Levy S., McGue M. Next-generation genotype imputation service and methods. Nat. Genet. 2016;48:1284–1287. doi: 10.1038/ng.3656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCarthy S., Das S., Kretzschmar W., Delaneau O., Wood A.R., Teumer A., Kang H.M., Fuchsberger C., Danecek P., Sharp K., Haplotype Reference Consortium A reference panel of 64,976 haplotypes for genotype imputation. Nat. Genet. 2016;48:1279–1283. doi: 10.1038/ng.3643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delaneau O., Zagury J.F., Marchini J. Improved whole-chromosome phasing for disease and population genetic studies. Nat. Methods. 2013;10:5–6. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Price A.L., Patterson N.J., Plenge R.M., Weinblatt M.E., Shadick N.A., Reich D. Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:904–909. doi: 10.1038/ng1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.R Development Core Team . R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2019. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Motyer A., Vukcevic D., Dilthey A., Donnelly P., McVean G., Leslie S. Practical Use of Methods for Imputation of HLA Alleles from SNP Genotype Data. bioRxiv. 2016 doi: 10.1101/091009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ward L.D., Kellis M. HaploReg: a resource for exploring chromatin states, conservation, and regulatory motif alterations within sets of genetically linked variants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D930–D934. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Consortium G.T., GTEx Consortium Human genomics. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) pilot analysis: multitissue gene regulation in humans. Science. 2015;348:648–660. doi: 10.1126/science.1262110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jansen R., Hottenga J.J., Nivard M.G., Abdellaoui A., Laport B., de Geus E.J., Wright F.A., Penninx B.W.J.H., Boomsma D.I. Conditional eQTL analysis reveals allelic heterogeneity of gene expression. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2017;26:1444–1451. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddx043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Westra H.J., Peters M.J., Esko T., Yaghootkar H., Schurmann C., Kettunen J., Christiansen M.W., Fairfax B.P., Schramm K., Powell J.E. Systematic identification of trans eQTLs as putative drivers of known disease associations. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:1238–1243. doi: 10.1038/ng.2756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boyle A.P., Hong E.L., Hariharan M., Cheng Y., Schaub M.A., Kasowski M., Karczewski K.J., Park J., Hitz B.C., Weng S. Annotation of functional variation in personal genomes using RegulomeDB. Genome Res. 2012;22:1790–1797. doi: 10.1101/gr.137323.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schofield E.C., Carver T., Achuthan P., Freire-Pritchett P., Spivakov M., Todd J.A., Burren O.S. CHiCP: a web-based tool for the integrative and interactive visualization of promoter capture Hi-C datasets. Bioinformatics. 2016;32:2511–2513. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dozmorov M.G., Cara L.R., Giles C.B., Wren J.D. GenomeRunner web server: regulatory similarity and differences define the functional impact of SNP sets. Bioinformatics. 2016;32:2256–2263. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kundaje A., Meuleman W., Ernst J., Bilenky M., Yen A., Heravi-Moussavi A., Kheradpour P., Zhang Z., Wang J., Ziller M.J., Roadmap Epigenomics Consortium Integrative analysis of 111 reference human epigenomes. Nature. 2015;518:317–330. doi: 10.1038/nature14248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Consortium E.P., ENCODE Project Consortium An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature. 2012;489:57–74. doi: 10.1038/nature11247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou Y., Zhou B., Pache L., Chang M., Khodabakhshi A.H., Tanaseichuk O., Benner C., Chanda S.K. Metascape provides a biologist-oriented resource for the analysis of systems-level datasets. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:1523. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09234-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hughes T., Adler A., Merrill J.T., Kelly J.A., Kaufman K.M., Williams A., Langefeld C.D., Gilkeson G.S., Sanchez E., Martin J., BIOLUPUS Network Analysis of autosomal genes reveals gene-sex interactions and higher total genetic risk in men with systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2012;71:694–699. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Canela-Xandri O., Rawlik K., Tenesa A. An atlas of genetic associations in UK Biobank. Nat. Genet. 2018;50:1593–1599. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0248-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bycroft C., Freeman C., Petkova D., Band G., Elliott L.T., Sharp K., Motyer A., Vukcevic D., Delaneau O., O’Connell J. The UK Biobank resource with deep phenotyping and genomic data. Nature. 2018;562:203–209. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0579-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burren O.S., Reales G., Wong L., Bowes J., Lee J.C., Barton A., Lyons P.A., Smith K.G.C., Thomson W., Kirk P.D.W. Informed dimension reduction of clinically-related genome-wide association summary data characterises cross-trait axes of genetic risk. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.01.14.905869. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roselli C., Chaffin M.D., Weng L.C., Aeschbacher S., Ahlberg G., Albert C.M., Almgren P., Alonso A., Anderson C.D., Aragam K.G. Multi-ethnic genome-wide association study for atrial fibrillation. Nat. Genet. 2018;50:1225–1233. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0133-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stitziel N.O., Stirrups K.E., Masca N.G., Erdmann J., Ferrario P.G., König I.R., Weeke P.E., Webb T.R., Auer P.L., Schick U.M., Myocardial Infarction Genetics and CARDIoGRAM Exome Consortia Investigators Coding Variation in ANGPTL4, LPL, and SVEP1 and the Risk of Coronary Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016;374:1134–1144. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van der Harst P., Verweij N. Identification of 64 Novel Genetic Loci Provides an Expanded View on the Genetic Architecture of Coronary Artery Disease. Circ. Res. 2018;122:433–443. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.312086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kichaev G., Bhatia G., Loh P.R., Gazal S., Burch K., Freund M.K., Schoech A., Pasaniuc B., Price A.L. Leveraging Polygenic Functional Enrichment to Improve GWAS Power. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2019;104:65–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jonker C.T.H., Galmes R., Veenendaal T., Ten Brink C., van der Welle R.E.N., Liv N., de Rooij J., Peden A.A., van der Sluijs P., Margadant C., Klumperman J. Vps3 and Vps8 control integrin trafficking from early to recycling endosomes and regulate integrin-dependent functions. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:792. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03226-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Banerjee S., Biehl A., Gadina M., Hasni S., Schwartz D.M. JAK-STAT Signaling as a Target for Inflammatory and Autoimmune Diseases: Current and Future Prospects. Drugs. 2017;77:521–546. doi: 10.1007/s40265-017-0701-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stahl E.A., Raychaudhuri S., Remmers E.F., Xie G., Eyre S., Thomson B.P., Li Y., Kurreeman F.A., Zhernakova A., Hinks A., BIRAC Consortium. YEAR Consortium Genome-wide association study meta-analysis identifies seven new rheumatoid arthritis risk loci. Nat. Genet. 2010;42:508–514. doi: 10.1038/ng.582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ellinghaus D., Ellinghaus E., Nair R.P., Stuart P.E., Esko T., Metspalu A., Debrus S., Raelson J.V., Tejasvi T., Belouchi M. Combined analysis of genome-wide association studies for Crohn disease and psoriasis identifies seven shared susceptibility loci. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2012;90:636–647. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ortiz-Fernández L., Carmona F.D., López-Mejías R., González-Escribano M.F., Lyons P.A., Morgan A.W., Sawalha A.H., Merkel P.A., Smith K.G.C., González-Gay M.A., Martín J., Spanish GCA Study Group, UK GCA Consortium, Turkish Takayasu Study Group, Vasculitis Clinical Research Consortium, IgAV Study Group, AAV Study group Cross-phenotype analysis of Immunochip data identifies KDM4C as a relevant locus for the development of systemic vasculitis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2018;77:589–595. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carmona F.D., Coit P., Saruhan-Direskeneli G., Hernández-Rodríguez J., Cid M.C., Solans R., Castañeda S., Vaglio A., Direskeneli H., Merkel P.A., Spanish GCA Study Group. Italian GCA Study Group. Turkish Takayasu Study Group. Vasculitis Clinical Research Consortium Analysis of the common genetic component of large-vessel vasculitides through a meta-Immunochip strategy. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:43953. doi: 10.1038/srep43953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gilgès D., Vinit M.A., Callebaut I., Coulombel L., Cacheux V., Romeo P.H., Vigon I. Polydom: a secreted protein with pentraxin, complement control protein, epidermal growth factor and von Willebrand factor A domains. Biochem. J. 2000;352:49–59. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sato-Nishiuchi R., Nakano I., Ozawa A., Sato Y., Takeichi M., Kiyozumi D., Yamazaki K., Yasunaga T., Futaki S., Sekiguchi K. Polydom/SVEP1 is a ligand for integrin α9β1. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:25615–25630. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.355016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kon S., Uede T. The role of α9β1 integrin and its ligands in the development of autoimmune diseases. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 2018;12:333–342. doi: 10.1007/s12079-017-0413-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Morooka N., Futaki S., Sato-Nishiuchi R., Nishino M., Totani Y., Shimono C., Nakano I., Nakajima H., Mochizuki N., Sekiguchi K. Polydom Is an Extracellular Matrix Protein Involved in Lymphatic Vessel Remodeling. Circ. Res. 2017;120:1276–1288. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.308825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nakada T.A., Russell J.A., Boyd J.H., Thair S.A., Walley K.R. Identification of a nonsynonymous polymorphism in the SVEP1 gene associated with altered clinical outcomes in septic shock. Crit. Care Med. 2015;43:101–108. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Giri A., Hellwege J.N., Keaton J.M., Park J., Qiu C., Warren H.R., Torstenson E.S., Kovesdy C.P., Sun Y.V., Wilson O.D., Understanding Society Scientific Group. International Consortium for Blood Pressure. Blood Pressure-International Consortium of Exome Chip Studies. Million Veteran Program Trans-ethnic association study of blood pressure determinants in over 750,000 individuals. Nat. Genet. 2019;51:51–62. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0303-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maciver S.K., Hussey P.J. The ADF/cofilin family: actin-remodeling proteins. Genome Biol. 2002;3 doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-5-reviews3007. reviews3007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Burbage M., Keppler S.J. Shaping the humoral immune response: Actin regulators modulate antigen presentation and influence B-T interactions. Mol. Immunol. 2018;101:370–376. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2018.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee K.H., Meuer S.C., Samstag Y. Cofilin: a missing link between T cell co-stimulation and rearrangement of the actin cytoskeleton. Eur. J. Immunol. 2000;30:892–899. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200003)30:3<892::AID-IMMU892>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nielsen J.B., Thorolfsdottir R.B., Fritsche L.G., Zhou W., Skov M.W., Graham S.E., Herron T.J., McCarthy S., Schmidt E.M., Sveinbjornsson G. Biobank-driven genomic discovery yields new insight into atrial fibrillation biology. Nat. Genet. 2018;50:1234–1239. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0171-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Agrawal P.B., Greenleaf R.S., Tomczak K.K., Lehtokari V.L., Wallgren-Pettersson C., Wallefeld W., Laing N.G., Darras B.T., Maciver S.K., Dormitzer P.R., Beggs A.H. Nemaline myopathy with minicores caused by mutation of the CFL2 gene encoding the skeletal muscle actin-binding protein, cofilin-2. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;80:162–167. doi: 10.1086/510402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Szklarczyk D., Gable A.L., Lyon D., Junge A., Wyder S., Huerta-Cepas J., Simonovic M., Doncheva N.T., Morris J.H., Bork P. STRING v11: protein-protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):D607–D613. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yamada Y., Kato K., Oguri M., Horibe H., Fujimaki T., Yasukochi Y., Takeuchi I., Sakuma J. Identification of 13 novel susceptibility loci for early-onset myocardial infarction, hypertension, or chronic kidney disease. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2018;42:2415–2436. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2018.3852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liu J.Z., van Sommeren S., Huang H., Ng S.C., Alberts R., Takahashi A., Ripke S., Lee J.C., Jostins L., Shah T., International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics Consortium. International IBD Genetics Consortium Association analyses identify 38 susceptibility loci for inflammatory bowel disease and highlight shared genetic risk across populations. Nat. Genet. 2015;47:979–986. doi: 10.1038/ng.3359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Franke A., McGovern D.P., Barrett J.C., Wang K., Radford-Smith G.L., Ahmad T., Lees C.W., Balschun T., Lee J., Roberts R. Genome-wide meta-analysis increases to 71 the number of confirmed Crohn’s disease susceptibility loci. Nat. Genet. 2010;42:1118–1125. doi: 10.1038/ng.717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tsoi L.C., Spain S.L., Knight J., Ellinghaus E., Stuart P.E., Capon F., Ding J., Li Y., Tejasvi T., Gudjonsson J.E., Collaborative Association Study of Psoriasis (CASP) Genetic Analysis of Psoriasis Consortium. Psoriasis Association Genetics Extension. Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium 2 Identification of 15 new psoriasis susceptibility loci highlights the role of innate immunity. Nat. Genet. 2012;44:1341–1348. doi: 10.1038/ng.2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Reveille J.D., Sims A.M., Danoy P., Evans D.M., Leo P., Pointon J.J., Jin R., Zhou X., Bradbury L.A., Appleton L.H., Australo-Anglo-American Spondyloarthritis Consortium (TASC) Genome-wide association study of ankylosing spondylitis identifies non-MHC susceptibility loci. Nat. Genet. 2010;42:123–127. doi: 10.1038/ng.513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Anderson C.A., Boucher G., Lees C.W., Franke A., D’Amato M., Taylor K.D., Lee J.C., Goyette P., Imielinski M., Latiano A. Meta-analysis identifies 29 additional ulcerative colitis risk loci, increasing the number of confirmed associations to 47. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:246–252. doi: 10.1038/ng.764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Guinamard R., Okigaki M., Schlessinger J., Ravetch J.V. Absence of marginal zone B cells in Pyk-2-deficient mice defines their role in the humoral response. Nat. Immunol. 2000;1:31–36. doi: 10.1038/76882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nair R.P., Duffin K.C., Helms C., Ding J., Stuart P.E., Goldgar D., Gudjonsson J.E., Li Y., Tejasvi T., Feng B.J., Collaborative Association Study of Psoriasis Genome-wide scan reveals association of psoriasis with IL-23 and NF-kappaB pathways. Nat. Genet. 2009;41:199–204. doi: 10.1038/ng.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Iwasaki H., Akashi K. Myeloid lineage commitment from the hematopoietic stem cell. Immunity. 2007;26:726–740. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.McKercher S.R., Torbett B.E., Anderson K.L., Henkel G.W., Vestal D.J., Baribault H., Klemsz M., Feeney A.J., Wu G.E., Paige C.J., Maki R.A. Targeted disruption of the PU.1 gene results in multiple hematopoietic abnormalities. EMBO J. 1996;15:5647–5658. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sevilla L., Zaldumbide A., Carlotti F., Dayem M.A., Pognonec P., Boulukos K.E. Bcl-XL expression correlates with primary macrophage differentiation, activation of functional competence, and survival and results from synergistic transcriptional activation by Ets2 and PU.1. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:17800–17807. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008270200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Han J.W., Zheng H.F., Cui Y., Sun L.D., Ye D.Q., Hu Z., Xu J.H., Cai Z.M., Huang W., Zhao G.P. Genome-wide association study in a Chinese Han population identifies nine new susceptibility loci for systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat. Genet. 2009;41:1234–1237. doi: 10.1038/ng.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.de Lange K.M., Moutsianas L., Lee J.C., Lamb C.A., Luo Y., Kennedy N.A., Jostins L., Rice D.L., Gutierrez-Achury J., Ji S.G. Genome-wide association study implicates immune activation of multiple integrin genes in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat. Genet. 2017;49:256–261. doi: 10.1038/ng.3760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Espinoza J.L., Ai S., Matsumura I. New Insights on the Pathogenesis of Takayasu Arteritis: Revisiting the Microbial Theory. Pathogens. 2018;7:73. doi: 10.3390/pathogens7030073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hoyer B.F., Mumtaz I.M., Loddenkemper K., Bruns A., Sengler C., Hermann K.G., Maza S., Keitzer R., Burmester G.R., Buttgereit F. Takayasu arteritis is characterised by disturbances of B cell homeostasis and responds to B cell depletion therapy with rituximab. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2012;71:75–79. doi: 10.1136/ard.2011.153007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]