Key Points

Question

What is the association of aspirin use with the risk of colorectal cancer in older adults?

Findings

In this pooled analysis of 2 cohort studies with a total of 94 540 participants, regular use of aspirin at or after age 70 years was associated with a lower risk of colorectal cancer compared with nonregular use. However, this reduction in risk was evident only among individuals who initiated use at a younger age.

Meaning

These results suggest that the initiation of aspirin use at an older age for the sole purpose of primary prevention of colorectal cancer should be discouraged; however, the findings support recommendations to continue using aspirin if initiated at a younger age.

This pooled analysis of 2 cohort studies evaluates the association of aspirin use with the risk of colorectal cancer in older adults.

Abstract

Importance

Although aspirin is recommended for the prevention of colorectal cancer (CRC) among adults aged 50 to 59 years, recent data from a randomized clinical trial suggest a lack of benefit and even possible harm among older adults.

Objective

To examine the association between aspirin use and the risk of incident CRC among older adults.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A pooled analysis was conducted of 2 large US cohort studies, the Nurses’ Health Study (June 1, 1980–June 30, 2014) and Health Professionals Follow-up Study (January 1, 1986–January 31, 2014). A total of 94 540 participants aged 70 years or older were included and followed up to June 30, 2014, for women or January 31, 2014, for men. Participants with a diagnosis of any cancer, except nonmelanoma skin cancer, or inflammatory bowel disease were excluded. Statistical analyses were conducted from December 2019 to October 2020.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Cox proportional hazards models were used to calculate multivariable adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs for incident CRC.

Results

Among the 94 540 participants (mean [SD] age, 76.4 [4.9] years for women, 77.7 [5.6] years for men; 67 223 women [71.1%]; 65 259 White women [97.1%], 24 915 White men [96.0%]) aged 70 years or older, 1431 incident cases of CRC were documented over 996 463 person-years of follow-up. After adjustment for other risk factors, regular use of aspirin was associated with a significantly lower risk of CRC at or after age 70 years compared with nonregular use (HR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.72-0.90). However, the inverse association was evident only among aspirin users who initiated aspirin use before age 70 years (HR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.67-0.95). In contrast, initiating aspirin use at or after 70 years was not significantly associated with a lower risk of CRC (HR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.76-1.11).

Conclusions and Relevance

Initiating aspirin at an older age was not associated with a lower risk of CRC in this pooled analysis of 2 cohort studies. In contrast, those who used aspirin before age 70 years and continued into their 70s or later had a reduced risk of CRC.

Introduction

Aspirin is considered the most established agent for chemoprevention of colorectal cancer (CRC)1,2,3 and is currently recommended by the US Preventive Services Task Force for individuals aged 50 to 59 years with specific cardiovascular risk profiles.4 This recommendation is due to remarkably consistent data from previous cohort studies and randomized clinical trials (RCTs).5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13 However, the US Preventive Services Task Force cited insufficient evidence to issue a recommendation for adults aged 70 years or older.

Recently, the Aspirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly (ASPREE) study, an RCT of 19 114 relatively healthy adults aged 70 years or older (or 65 years or older for US racial/ethnic minorities), reported that participants assigned to daily low-dose aspirin (100 mg) had an increased risk of death from cancer, including CRC, after a median of 4.7 years of follow-up,14 without a corresponding increase in overall incidence and CRC incidence.15 These results suggest a potential difference in the effect of aspirin at older ages. However, the vast majority of ASPREE participants (89%) had never used aspirin regularly before joining the study.16 Thus, the association of continuing aspirin use with CRC at older ages among individuals who initiate use when younger remains unclear.

Previous studies have found that regular use of aspirin is associated with a lower risk of CRC in the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study (HPFS).6,11,17 In the present study, we specifically evaluated the association between regular use of aspirin and CRC incidence among participants in the NHS and HPFS who had reached age 70 years, which provides a unique opportunity to prospectively examine the use of aspirin across mid and late adulthood in association with long-term risk of CRC.

Methods

Study Population

This prospective cohort study included women from the NHS and men from the HPFS who reached 70 years of age. The NHS, conducted from June 1, 1980, to June 30, 2014, is a prospective cohort of 121 701 US female registered nurses aged 30 to 55 years at enrollment. The HPFS was conducted from January 1, 1986, to January 31, 2014, and included 51 529 male health professionals aged 40 to 75 years. Details of the cohorts have been described previously.6,11 Participants were mailed biennial questionnaires that included a validated assessment of diet and questions on lifestyle factors, medical history, and disease outcomes, including aspirin use and CRC. The response rate reached 90% in both cohorts.18 We excluded participants with a diagnosis of any cancer, except nonmelanoma skin cancer, or inflammatory bowel disease before age 70 years. Participants with missing prior aspirin use and those who died or were lost to follow-up before 70 years were also excluded. We also excluded participants with missing aspirin use data during follow-up (5186 [4.3%] in the NHS and 1357 [2.5%] in the HPFS; eFigure in the Supplement). The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of the Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, and those of participating registries as required. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants to access their medical records. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

Assessment of Exposure and Covariates

Beginning in 1980 for the NHS and 1986 for the HPFS, we collected information biennially on participants’ use of aspirin. Participants were specifically asked about use of standard-dose (325 mg) tablets. Between 1994 and 1998, participants were asked to convert 4 low-dose (81 mg) aspirin tablets to 1 standard-dose tablet. Since 2000, regular use of low-dose aspirin was reported separately from standard-dose aspirin.18 Consistent with our prior studies,6,18,19 regular aspirin use was defined as using aspirin 2 or more times per week, including both standard-dose and low-dose aspirin. Missing aspirin use was updated using information from the previous questionnaires with only 1 biennial questionnaire cycle carried forward. Our primary exposure was regular aspirin use at or after age 70 years. Nonregular aspirin users were those who were not regular users of aspirin at any time at or after 70 years. In the NHS, participants were asked in 1980 how many years they had been regularly using aspirin. In the HPFS, prior aspirin use at younger ages was collected in 1996, and participants were asked if they used aspirin and the use frequency in their 20s, 30s, 40s, 50s, and 60s. Consistent with previous studies,18,19 covariates were selected as potential confounders (eMethods in the Supplement).

Ascertainment of Outcome

Our primary end point was incident CRC. Written permission to acquire medical records and pathology reports was obtained from participants who reported CRC on the biennial questionnaire. Deaths were identified through the National Death Index, next of kin, and postal authorities. For all deaths due to CRC, we requested permission to review medical records from the next of kin. Two blinded physicians (K.N., J.A.M., or E.L.G.) reviewed records to confirm a diagnosis of CRC and abstract information on tumor, node, metastasis (TNM) stage at the time of diagnosis.

Statistical Analysis

Person-time started from the date a person reached the age of 70 years until the date of diagnosis of CRC, death, or the end of follow-up on June 30, 2014, for women or January 31, 2014, for men, whichever came first. We evaluated the association between biennially updated aspirin use and CRC risk at or after age 70 years. We also examined the association according to prior aspirin use (prior regular aspirin user or prior nonregular user) and prior aspirin use duration (<5 or ≥5 years) before age 70 years. Analyses according to CRC defined by stage were also performed.

Cox proportional hazards regression model stratified on age and calendar time (2-year intervals) was used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs. All covariates were updated biennially and included as time-varying variables. In the multivariable model, covariates including family history of CRC; personal history of diabetes; body mass index; alcohol use; physical activity20; smoking pack-years; lower endoscopy; Alternative Healthy Eating Index 2010 score21; intakes of total calories, calcium, and folate; and regular use of other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), multivitamins, and menopausal hormones (for women only) were adjusted. To address the potential influence of cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk, a model further adjusted for regular use of cholesterol-lowering drugs (eg, statins), hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and CVD was performed. Analyses were performed separately in the NHS and HPFS cohorts, and a meta-analysis was then conducted using a random-effects model for pooled estimates.

As a secondary analysis, we further evaluated the association of aspirin initiated at different age categories and risk of subsequent incident CRC through separate cohort analyses among participants who had not used aspirin before reaching the corresponding age category in the NHS. For each cohort defined according to baseline categories of age at initiation, we evaluated the risk of incident CRC after the baseline age (eMethods in the Supplement).

For all analyses, a 2-sided P < .05 was regarded as statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc). Statistical analyses were conducted from December 2019 to October 2020.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

We analyzed a total of 94 540 participants aged 70 years or older (mean [SD] age, 76.4 [4.9] years for women, 77.7 [5.6] years for men; 65 259 White women [97.1%], 24 915 White men [96.0%]), including 67 223 women from the NHS (71.1%) and 27 317 men from the HPFS (28.9%), encompassing 996 463 total person-years (699 626 years for the NHS and 296 837 years for the HPFS) of follow-up. We documented 1431 incident cases of CRC, including 857 (59.9%) among women (NHS) and 574 (40.1%) among men (HPFS). The age-standardized characteristics of participants according to aspirin use at or after age 70 years in the NHS and the HPFS are presented in eTable 1 in the Supplement. In both the NHS and the HPFS, compared with nonusers, participants who used aspirin at or after age 70 years were more likely to be older (mean [SD] age, 75.1 [4.5] vs 77.3 [5.0] years in the NHS and 75.7 [5.0] vs 78.4 [5.7] years in the HPFS); smoke currently or in the past (51.7% vs 53.9% in the NHS and 51.5% vs 55.5% in the HPFS); have a prior lower endoscopy (30.2% vs 31.8% in the NHS and 31.2% vs 36.8% in the HPFS); have a history of hypertension (60.5% vs 72.0% in the NHS and 45.6% vs 59.3% in the HPFS), dyslipidemia (67.3% vs 77.0% in the NHS and 44.9% vs 61.4% in the HPFS), diabetes (11.9% vs 15.9% in the NHS and 11.1% vs 14.3% in the HPFS), and CVDs (11.6% vs 23.3% in the NHS and 17.4% vs 38.4% in the HPFS); regularly use multivitamins (65.1% vs 72.4% in the NHS and 57.5% vs 68.8% in the HPFS), NSAIDs (27.7% vs 30.5% in the NHS and 12.3% vs 17.2% in the HPFS), and cholesterol-lowering drugs (23.4% vs 40.9% in the NHS and 14.4% vs 35.1% in the HPFS); take in more total calories (mean [SD] kcal/d, 1665 [423] vs 1675 [418] in the NHS and 1955 [534] vs 1969 [520] in the HPFS); and consume more folate (mean [SD] μg/d, 509 [200] vs 536 [191] in the NHS and 586 [253] vs 630 [241] in the HPFS) and calcium (mean [SD] mg/d, 1097 [396] vs 1148 [392] in the NHS and 981 [382] vs 1014 [365] in the HPFS).

Aspirin Use at 70 Years or Older and Risk of CRC

Among individuals aged 70 years or older, regular use of aspirin was associated with a lower risk of CRC compared with nonregular users (pooled HR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.72-0.90 [model 2]) (Table 1), which was consistent in both women (HR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.70-0.93) and men (HR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.67-0.97). However, this inverse association was restricted to those who initiated regular use of aspirin before age 70 years (pooled HR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.67-0.95). In contrast, among those who did not regularly use aspirin before age 70 years, regular aspirin use at or after 70 years was not associated with reduced risk of CRC (pooled HR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.76-1.11) (Table 1). The results were consistent after further adjustment for use of cholesterol-lowering drugs, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and CVD (model 3). Among individuals who used aspirin before age 70 years, the inverse association was also consistent after further adjustment for duration of aspirin use before 70 years (pooled HR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.70-0.95).

Table 1. Aspirin Use at Age 70 Years or Above and Risk of Colorectal Cancer.

| Variable | HR (95% CI)a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHS | HPFS | Pooled analysis | ||||

| Nonregular user | Regular user | Nonregular user | Regular user | Nonregular user | Regular user | |

| Overall | ||||||

| No. of cases/person-years | 414/295 970 | 443/403 656 | 179/79 649 | 395/217 188 | 593/375 619 | 838/620 844 |

| Model 1b | 1 [Reference] | 0.79 (0.69-0.91) | 1 [Reference] | 0.79 (0.65-0.94) | 1 [Reference] | 0.79 (0.70-0.88) |

| Model 2c | 1 [Reference] | 0.81 (0.70-0.93) | 1 [Reference] | 0.80 (0.67-0.97) | 1 [Reference] | 0.80 (0.72-0.90) |

| Model 3d | 1 [Reference] | 0.80 (0.69-0.92) | 1 [Reference] | 0.85 (0.70-1.03) | 1 [Reference] | 0.81 (0.73-0.91) |

| Nonregular use of aspirin before age 70 | ||||||

| No. of cases/person-years | 215/125 690 | 109/74 204 | 106/44 553 | 113/45 149 | 321/170 243 | 222/119 353 |

| Model 1b | 1 [Reference] | 0.86 (0.67-1.10) | 1 [Reference] | 0.95 (0.71-1.27) | 1 [Reference] | 0.90 (0.74-1.08) |

| Model 2c | 1 [Reference] | 0.88 (0.69-1.13) | 1 [Reference] | 0.98 (0.73-1.31) | 1 [Reference] | 0.92 (0.76-1.11) |

| Model 3d | 1 [Reference] | 0.87 (0.67-1.12) | 1 [Reference] | 1.05 (0.78-1.41) | 1 [Reference] | 0.94 (0.77-1.14) |

| Prior history of regular use of aspirin before age 70 | ||||||

| No. of cases/person-years | 199/170 280 | 334/329 452 | 73/35 096 | 282/172 039 | 272/205 376 | 616/501 491 |

| Model 1b | 1 [Reference] | 0.86 (0.72-1.03) | 1 [Reference] | 0.70 (0.53-0.91) | 1 [Reference] | 0.79 (0.65-0.97) |

| Model 2c | 1 [Reference] | 0.85 (0.71-1.02) | 1 [Reference] | 0.71 (0.54-0.92) | 1 [Reference] | 0.80 (0.67-0.95) |

| Model 3d | 1 [Reference] | 0.84 (0.70-1.01) | 1 [Reference] | 0.73 (0.56-0.96) | 1 [Reference] | 0.80 (0.69-0.94) |

| Model 4e | 1 [Reference] | 0.85 (0.71-1.02) | 1 [Reference] | 0.74 (0.56-0.97) | 1 [Reference] | 0.81 (0.70-0.95) |

Abbreviations: HPFS, Health Professionals Follow-up Study; HR, hazard ratio; NHS, Nurses’ Health Study.

Values listed as HR (95% CI) unless otherwise indicated.

Model 1 is conditioned on age and calendar time.

Model 2 is conditioned on age and calendar time, and adjusted for family history of colorectal cancer, diabetes, body mass index, alcohol consumption, physical activity, smoking pack-years, lower endoscopy, total energy intake, calcium intake, folate intake, Alternative Healthy Eating Index 2010 score, and regular use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, multivitamins, and menopausal hormones (for women only).

Model 3 includes model 2 covariates plus regular use of cholesterol-lowering drugs, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and cardiovascular diseases.

Model 4 includes model 2 covariates plus duration of aspirin use before age 70.

These results were largely consistent in analyses according to CRC stage, although we had limited statistical power within each stage category. The multivariable HR for regular aspirin use after 70 years was 0.83 (95% CI, 0.69-1.00) for nonmetastatic (stage I, II, III) and 0.45 (95% CI, 0.15-1.38) for metastatic (stage IV) CRC among those who regularly used aspirin before age 70 years of age (eTable 2 in the Supplement).

Analyses by Duration of Aspirin Use Before Age 70 Years or Age at Initiation

We further grouped those who initiated aspirin before age 70 years by the cumulative duration of use before 70 years. The apparent protective benefits of aspirin use at or after 70 years were evident only among those who had regularly used aspirin for 5 or more years before 70 years of age (pooled HR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.59-0.98). In contrast, no benefit was observed among those who used aspirin for less than 5 years before 70 years of age (pooled HR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.77-1.30) (Table 2). When we considered the initiation age of aspirin use, the lower risk of CRC for aspirin use at or after 70 years was found only when individuals initiated aspirin before 70 years of age (Table 3).

Table 2. Aspirin Use at Age 70 or Above and Risk of Colorectal Cancer by Prior Duration of Use.

| Variable | HR (95% CI)a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHS | HPFS | Pooled analysis | ||||

| Nonregular user | Regular user | Nonregular user | Regular user | Nonregular user | Regular user | |

| Duration of use <5 y before age 70 | ||||||

| No. of cases/person-years | 67/52 382 | 126/97 913 | 20/11 170 | 75/37 180 | 87/63 552 | 201/135 093 |

| Model 1b | 1 [Reference] | 1.00 (0.74-1.36) | 1 [Reference] | 1.03 (0.61-1.74) | 1 [Reference] | 1.01 (0.77-1.31) |

| Model 2c | 1 [Reference] | 0.99 (0.73-1.34) | 1 [Reference] | 1.03 (0.61-1.75) | 1 [Reference] | 1.00 (0.77-1.30) |

| Model 3d | 1 [Reference] | 0.98 (0.72-1.34) | 1 [Reference] | 1.05 (0.61-1.80) | 1 [Reference] | 1.00 (0.76-1.30) |

| Duration of use ≥5 y before age 70 | ||||||

| No. of cases/person-years | 129/116 434 | 237/249 978 | 48/23 167 | 229/145 677 | 177/139 608 | 466/395 655 |

| Model 1b | 1 [Reference] | 0.85 (0.68-1.06) | 1 [Reference] | 0.65 (0.47-0.90) | 1 [Reference] | 0.76 (0.59-0.99) |

| Model 2c | 1 [Reference] | 0.84 (0.68-1.05) | 1 [Reference] | 0.65 (0.47-0.90) | 1 [Reference] | 0.76 (0.59-0.98) |

| Model 3d | 1 [Reference] | 0.83 (0.67-1.04) | 1 [Reference] | 0.67 (0.48-0.93) | 1 [Reference] | 0.77 (0.63-0.95) |

Abbreviations: HPFS, Health Professionals Follow-up Study; HR, hazard ratio; NHS, Nurses’ Health Study.

Values are listed as HR (95% CI) unless otherwise indicated.

Model 1 is conditioned on age and calendar time.

Model 2 is conditioned on age and calendar time, and adjusted for family history of colorectal cancer, diabetes, body mass index, alcohol consumption, physical activity, smoking pack-years, lower endoscopy, total energy intake, calcium intake, folate intake, Alternative Healthy Eating Index 2010 score, and regular use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, multivitamins, and menopausal hormones.

Model 3 includes model 2 covariates plus regular use of cholesterol-lowering drugs, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and cardiovascular diseases.

Table 3. Aspirin Use at Age 70 or Above and Risk of Colorectal Cancer by Age at Initiation.

| Pooled analysis | HR (95% CI)a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never regular user | Regular user only before age 70 | Regular user at or after age 70 | ||||

| Initiation age ≥70 | Initiation age 60-69 | Initiation age 50-59 | Initiation age <50 | |||

| No. of cases/person-years | 321/170 243 | 272/205 376 | 222/119 353 | 236/165 773 | 197/172 890 | 183/162 828 |

| Model 1b | 1 [Reference] | 0.90 (0.58-1.39) | 0.91 (0.76-1.08) | 0.69 (0.57-0.84) | 0.68 (0.50-0.92) | 0.72 (0.60-0.87) |

| Model 2c | 1 [Reference] | 0.93 (0.65-1.33) | 0.93 (0.78-1.11) | 0.71 (0.60-0.86) | 0.70 (0.55-0.89) | 0.76 (0.63-0.92) |

| Model 3d | 1 [Reference] | 0.94 (0.64-1.38) | 0.94 (0.78-1.12) | 0.73 (0.57-0.95) | 0.73 (0.52-1.02) | 0.77 (0.64-0.93) |

Abbreviation: HR, hazard ratio.

Values are listed as HR (95% CI) unless otherwise indicated.

Model 1 is conditioned on age and calendar time.

Model 2 is conditioned on age and calendar time, and adjusted for family history of colorectal cancer, diabetes, body mass index, alcohol consumption, physical activity, smoking pack-years, lower endoscopy, total energy intake, calcium intake, folate intake, Alternative Healthy Eating Index 2010 score, and regular use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, multivitamins, and menopausal hormones.

Model 3 includes model 2 covariates plus regular use of cholesterol-lowering drugs, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and cardiovascular diseases.

Aspirin Use With Different Initiation Age and Subsequent Risk of CRC After Initiation in the NHS

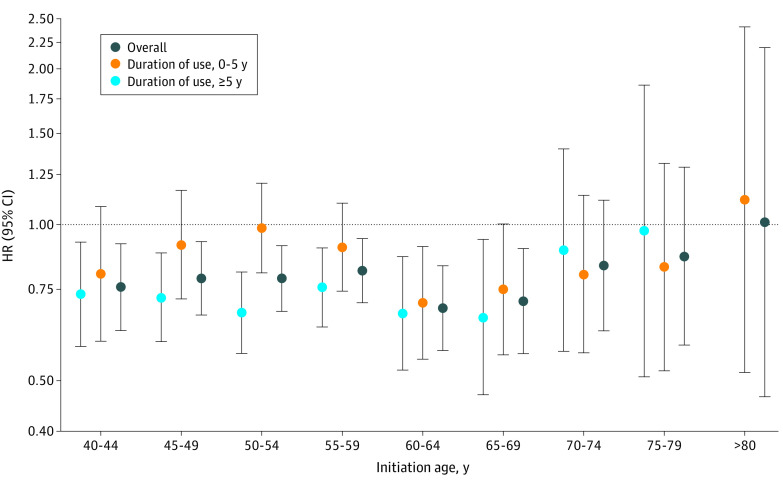

To further evaluate the association of aspirin initiated at different ages and subsequent risk of CRC (not restricted to CRC at or after 70 years), we performed separate cohort analyses among participants who had not used aspirin before reaching the corresponding age category in the NHS. Compared with nonregular users, women who initiated regular aspirin treatment at a younger age (<70 years) had a decreased risk of subsequent CRC, which was mainly consistent with the risk level among those who had cumulatively taken aspirin for 5 or more years (Figure). Specifically, compared with nonregular use, regular aspirin use was associated with a multivariable HR for CRC of 0.76 (95% CI, 0.63-0.92) for women who initiated aspirin use from 40 to 44 years of age; 0.79 (95% CI, 0.67-0.93) for ages 45 to 49 years; 0.79 (95% CI, 0.68-0.91) for ages 50 to 54 years; 0.82 (95% CI, 0.71-0.94) for ages 55 to 59 years; 0.69 (95% CI, 0.57-0.83) for ages 60 to 64 years; and 0.71 (95% CI, 0.56-0.90) for ages 65 to 69 years. In contrast, initiating aspirin use at an older age (≥70 years) was associated with weaker benefits, even for those who had cumulatively taken aspirin for 5 or more years. Specifically, the corresponding HR was 0.83 (95% CI, 0.62-1.12) for initiation of aspirin use at ages 70 to 74 years; 0.87 (95% CI, 0.59-1.29) for ages 75 to 79 years; and 1.01 (95% CI, 0.47-2.20) for 80 years and older.

Figure. Aspirin Initiated at Different Ages and Subsequent Risk of Colorectal Cancer in the Nurses’ Health Study.

Multivariable HRs for colorectal cancer of regular use of aspirin initiated at different ages or duration of use vs nonregular users were conditioned on age and calendar time and adjusted for family history of colorectal cancer, diabetes, body mass index, alcohol consumption, physical activity, smoking pack-years, lower endoscopy, total energy intake, calcium intake, folate intake, Alternative Healthy Eating Index 2010 score, and regular use of NSAIDs, multivitamins, and menopausal hormones. Owing to a limited number of participants who initiated aspirin after 80 years of age and used for more than 5 years, separate analysis was not performed. HR indicates hazard ratio; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

Discussion

In 2 large US prospective cohorts, regular aspirin use at or after 70 years of age was associated with a significantly reduced risk of CRC, but this association was evident only among those who regularly used aspirin at a younger age, particularly for at least 5 years before reaching 70 years of age. In contrast, initiation of aspirin after 70 years was not associated with lower risk of CRC.

Substantial evidence suggests that a benefit of aspirin for CRC requires at least 5 to 10 years of use.4 However, these data are primarily derived from cohort studies and RCTs conducted in middle-aged adults.13 This limitation led to current US Preventive Services Task Force recommendations for low-dose aspirin for primary prevention of CRC among US adults aged 50 to 59 years with a greater than 10% 10-year cardiovascular risk. However, this advice did not extend to adults 70 years or older, for whom the evidence was considered insufficient.4 Recently, the ASPREE RCT compared daily low-dose aspirin vs placebo in 19 114 healthy older adults.14 After 4.7 years of follow-up, participants taking aspirin experienced higher all-cause mortality that was largely attributable to death from cancer. A recent study reported no significant difference between groups for all incident cancers (HR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.95-1.14), including CRC (HR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.81-1.30), in the ASPREE trial.15 A secondary analysis of the Japanese Primary Prevention Project (JPPP), an open-label RCT designed to examine the effects of low-dose aspirin on vascular events in an older Japanese population (aged 60-85 years),22 showed that aspirin was associated with higher overall cancer incidence but not cancer mortality during a 5-year study period.23,24 Because 89% of the participants in the ASPREE trial and all the participants in the JPPP study did not regularly use aspirin before enrollment,16,24 our results demonstrating that initiation of aspirin use at or after age 70 was not associated with a reduction in risk of incident CRC are broadly consistent with the lack of protective effect observed in ASPREE and JPPP. However, these RCTs were inconsistent in demonstrating potential harm related to incidence and mortality.

A basis for the lack of outcome of aspirin on CRC when initiated at an older age is biologically plausible.25 There is growing evidence that cancers that arise in older adults may have a differential mechanistic basis compared with those in younger individuals. For example, aging is associated with alterations in DNA methylation, which may affect susceptibility to cancer.26,27 Among older adults, CRC arises more commonly in the right side of the colon,28,29 and tumors have a higher prevalence of specific molecular changes, including positive or high CpG island methylator phenotype and BRAF variations.30,31,32 Previous studies reported that regular aspirin use was associated with a lower risk of BRAF wild-type or KRAS wild-type CRC but not BRAF-variant or KRAS-variant CRC.33,34 There is also a greater incidence of the G12 variant of KRAS in those younger than 40 years compared with the more frequent A146, K117, and Q61 variants in older patients.35 Second, aspirin esterase activity may differ among older individuals, changing pharmacodynamic properties of aspirin.36 Third, the gut microbiota of older people differs from that of younger adults,37,38 which may influence drug metabolism39 and the development of age-related disease by modulating metabolic and inflammatory processes. For example, the gut microbiota may affect the antithrombotic activity of aspirin by reducing its level in circulation.40 A recent study also showed that Lysinibacillus sphaericu reduced the bioavailability and chemopreventive effects of aspirin on the development of CRC in mice.41 Last, body mass index or body weight may also influence the effect of aspirin on CRC. Some studies have shown that aspirin has limited benefit in individuals with higher body mass index or body weight,42,43 which is more common in an older population. However, a secondary analysis of the Concerted Action Polyposis Prevention 2 (CAPP2) study showed that aspirin preferentially protected against CRC in patients with obesity with Lynch syndrome.44

We acknowledge that the differential association of aspirin among those who initiated its use after 70 years of age may be due to a more limited duration of use. However, among those who initiated aspirin use after 70 years, we found that the lack of association of aspirin use with CRC was consistent among those who used for more than 5 years and those who used for less than 5 years (Figure). In addition, in many prior studies, aspirin use for at least 5 years was sufficient for an association to emerge.7,12 Another possible explanation for our results is that those who initiated aspirin after 70 years may differ in the prevalence of health conditions, such as CVD. However, in a model adjusted for additional CVD risk factors, such as use of cholesterol-lowering drugs (eg, statins), hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and CVD, the results were consistent. A recent analysis of data from the Women's Health Initiative also found that aspirin was associated with a lower risk of CRC within all levels of CVD risk, supporting the possibility that baseline CVD risk may not significantly affect the association.45

Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of this study include the use of 2 large, well-characterized cohorts of the NHS and the HPFS, which have collected biennial updated data on aspirin use since 1980 and 1986, respectively, and provided a unique opportunity to examine aspirin use across mid to late adulthood in association with long-term risk of CRC. We also prospectively collected important lifestyle and dietary risk factors to reduce the potential for confounding. Third, we confirmed CRC cases through medical records and pathology reports.

Our study also has several limitations. First, our results are not as definitive as in an RCT. However, such a trial to confirm the differential benefits according to age at initiation would require a large number of participants initiating aspirin at different ages with follow-up beyond 70 years of age, which limits feasibility. Second, this is a post hoc analysis and was not specifically powered to evaluate the association of aspirin initiated in older age with CRC. However, with our reasonably large sample size, our study still offers a potential explanation for the lack of protective effect of aspirin on CRC observed among older adults in the ASPREE trial. Third, although our study was large, we had limited ability to examine the association in specific subgroups, particularly according to different ages at initiation. Last, the NHS and HPFS are based on self-reported questionnaires. However, because our participants are health professionals, it is likely that self-reported intake reflects actual use.

Conclusions

In this cohort study, initiation of aspirin at an older age (≥70 years) was not associated with lower risk of CRC. In contrast, those who initiated aspirin at a younger age and continued use at an older age appeared to derive continued benefit for CRC risk reduction. Taken together with the results of the ASPREE trial, these findings suggest that initiation of aspirin use at an older age for the sole purpose of primary prevention of CRC should be discouraged. However, our findings appear to support recommendations to continue aspirin use if initiated at a younger age. Further studies to elucidate biologic mechanisms of aspirin according to age are warranted.

eMethods. Ascertainment of Covariates; Statistical Analyses

eFigure. Flowchart of the Study

eTable 1. Age-Standardized Characteristics of Participants Aged 70 or Above in Nurses’ Health Study (1980-2014) and Health Professionals Follow-up Study (1986-2014)

eTable 2. Regular Aspirin Use at or After Age 70 and Risk of Colorectal Cancer Developed at or After Age 70 According to Cancer Stage

eReferences

References

- 1.Drew DA, Cao Y, Chan AT. Aspirin and colorectal cancer: the promise of precision chemoprevention. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16(3):173-186. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chapelle N, Martel M, Toes-Zoutendijk E, Barkun AN, Bardou M. Recent advances in clinical practice: colorectal cancer chemoprevention in the average-risk population. Gut. 2020;69(12):2244-2255. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-320990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drew DA, Chan AT. Aspirin in the prevention of colorectal neoplasia. Annu Rev Med. 2020;72. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-060319-120913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bibbins-Domingo K; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force . Aspirin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(12):836-845. doi: 10.7326/M16-0577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flossmann E, Rothwell PM; British Doctors Aspirin Trial and the UK-TIA Aspirin Trial . Effect of aspirin on long-term risk of colorectal cancer: consistent evidence from randomised and observational studies. Lancet. 2007;369(9573):1603-1613. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60747-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan AT, Giovannucci EL, Meyerhardt JA, Schernhammer ES, Wu K, Fuchs CS. Aspirin dose and duration of use and risk of colorectal cancer in men. Gastroenterology. 2008;134(1):21-28. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.09.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rothwell PM, Wilson M, Elwin CE, et al. Long-term effect of aspirin on colorectal cancer incidence and mortality: 20-year follow-up of five randomised trials. Lancet. 2010;376(9754):1741-1750. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61543-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burn J, Gerdes AM, Macrae F, et al. ; CAPP2 Investigators . Long-term effect of aspirin on cancer risk in carriers of hereditary colorectal cancer: an analysis from the CAPP2 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;378(9809):2081-2087. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61049-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cook NR, Lee IM, Zhang SM, Moorthy MV, Buring JE. Alternate-day, low-dose aspirin and cancer risk: long-term observational follow-up of a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(2):77-85. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-2-201307160-00002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burn J, Sheth H, Elliott F, et al. ; CAPP2 Investigators . Cancer prevention with aspirin in hereditary colorectal cancer (Lynch syndrome), 10-year follow-up and registry-based 20-year data in the CAPP2 study: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2020;395(10240):1855-1863. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30366-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan AT, Ogino S, Fuchs CS. Aspirin and the risk of colorectal cancer in relation to the expression of COX-2. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(21):2131-2142. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bosetti C, Santucci C, Gallus S, Martinetti M, La Vecchia C. Aspirin and the risk of colorectal and other digestive tract cancers: an updated meta-analysis through 2019. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(5):558-568. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chubak J, Whitlock EP, Williams SB, et al. Aspirin for the prevention of cancer incidence and mortality: systematic evidence reviews for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(12):814-825. doi: 10.7326/M15-2117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McNeil JJ, Nelson MR, Woods RL, et al. ; ASPREE Investigator Group . Effect of aspirin on all-cause mortality in the healthy elderly. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(16):1519-1528. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1803955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McNeil JJ, Gibbs P, Orchard SG, et al. ; ASPREE Investigator Group . Effect of aspirin on cancer incidence and mortality in older adults. J Natl Cancer Inst. Published online August 11, 2020. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djaa114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McNeil JJ, Woods RL, Nelson MR, et al. ; ASPREE Investigator Group . Baseline characteristics of participants in the ASPREE (ASPirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly) Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017;72(11):1586-1593. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glw342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chan AT, Giovannucci EL, Meyerhardt JA, Schernhammer ES, Curhan GC, Fuchs CS. Long-term use of aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of colorectal cancer. JAMA. 2005;294(8):914-923. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.8.914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simon TG, Ma Y, Ludvigsson JF, et al. Association between aspirin use and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(12):1683-1690. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.4154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cao Y, Nishihara R, Wu K, et al. Population-wide impact of long-term use of aspirin and the risk for cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(6):762-769. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.6396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu PH, Wu K, Ng K, et al. Association of obesity with risk of early-onset colorectal cancer among women. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(1):37-44. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.4280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chiuve SE, Fung TT, Rimm EB, et al. Alternative dietary indices both strongly predict risk of chronic disease. J Nutr. 2012;142(6):1009-1018. doi: 10.3945/jn.111.157222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ikeda Y, Shimada K, Teramoto T, et al. Low-dose aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular events in Japanese patients 60 years or older with atherosclerotic risk factors: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312(23):2510-2520. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.15690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yokoyama K, Ishizuka N, Uemura N, et al. ; JPPP study group . Effects of daily aspirin on cancer incidence and mortality in the elderly Japanese. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2018;2(2):274-281. doi: 10.1002/rth2.12097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Teramoto T, Shimada K, Uchiyama S, et al. Rationale, design, and baseline data of the Japanese Primary Prevention Project (JPPP)—a randomized, open-label, controlled trial of aspirin versus no aspirin in patients with multiple risk factors for vascular events. Am Heart J . 2010;159(3):361–369 e4. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.11.030 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Chan AT, McNeil J. Aspirin and cancer prevention in the elderly: where do we go from here? Gastroenterology. 2019;156(3):534-538. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.11.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pérez RF, Tejedor JR, Bayón GF, Fernández AF, Fraga MF. Distinct chromatin signatures of DNA hypomethylation in aging and cancer. Aging Cell. 2018;17(3):e12744. doi: 10.1111/acel.12744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zheng SC, Widschwendter M, Teschendorff AE. Epigenetic drift, epigenetic clocks and cancer risk. Epigenomics. 2016;8(5):705-719. doi: 10.2217/epi-2015-0017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nawa T, Kato J, Kawamoto H, et al. Differences between right- and left-sided colon cancer in patient characteristics, cancer morphology and histology. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23(3):418-423. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.04923.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jess P, Hansen IO, Gamborg M, Jess T; Danish Colorectal Cancer Group . A nationwide Danish cohort study challenging the categorisation into right-sided and left-sided colon cancer. BMJ Open. 2013;3(5):e002608. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gonsalves WI, Mahoney MR, Sargent DJ, et al. ; Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology . Patient and tumor characteristics and BRAF and KRAS mutations in colon cancer, NCCTG/Alliance N0147. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(7):dju106. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ang PW, Loh M, Liem N, et al. Comprehensive profiling of DNA methylation in colorectal cancer reveals subgroups with distinct clinicopathological and molecular features. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:227. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Willauer AN, Liu Y, Pereira AAL, et al. Clinical and molecular characterization of early-onset colorectal cancer. Cancer. 2019;125(12):2002-2010. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Amitay EL, Carr PR, Jansen L, et al. Association of aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs with colorectal cancer risk by molecular subtypes. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111(5):475-483. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djy170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nishihara R, Lochhead P, Kuchiba A, et al. Aspirin use and risk of colorectal cancer according to BRAF mutation status. JAMA. 2013;309(24):2563-2571. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.6599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Serebriiskii IG, Connelly C, Frampton G, et al. Comprehensive characterization of RAS mutations in colon and rectal cancers in old and young patients. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):3722. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-11530-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hubbard RE, O’Mahony MS, Calver BL, Woodhouse KW. Plasma esterases and inflammation in ageing and frailty. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;64(9):895-900. doi: 10.1007/s00228-008-0499-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Claesson MJ, Cusack S, O’Sullivan O, et al. Composition, variability, and temporal stability of the intestinal microbiota of the elderly. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(suppl 1):4586-4591. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000097107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O’Toole PW, Jeffery IB. Gut microbiota and aging. Science. 2015;350(6265):1214-1215. doi: 10.1126/science.aac8469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wong SH, Yu J. Gut microbiota in colorectal cancer: mechanisms of action and clinical applications. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16(11):690-704. doi: 10.1038/s41575-019-0209-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim IS, Yoo DH, Jung IH, et al. Reduced metabolic activity of gut microbiota by antibiotics can potentiate the antithrombotic effect of aspirin. Biochem Pharmacol. 2016;122:72-79. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2016.09.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhao R, Coker OO, Wu J, et al. Aspirin reduces colorectal tumor development in mice and gut microbes reduce its bioavailability and chemopreventive effects. Gastroenterology. 2020;159(3):969-983.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang X, Chan AT, Slattery ML, et al. Influence of smoking, body mass index, and other factors on the preventive effect of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on colorectal cancer risk. Cancer Res. 2018;78(16):4790-4799. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-0326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rothwell PM, Cook NR, Gaziano JM, et al. Effects of aspirin on risks of vascular events and cancer according to bodyweight and dose: analysis of individual patient data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2018;392(10145):387-399. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31133-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Movahedi M, Bishop DT, Macrae F, et al. Obesity, aspirin, and risk of colorectal cancer in carriers of hereditary colorectal cancer: a prospective investigation in the CAPP2 Study. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(31):3591-3597. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.9952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seaton ME, Peters U, Johnson KC, Kooperberg C, Bafford A, Zubair N. Effects of colorectal cancer risk factors on the association between aspirin and colorectal cancer. Anticancer Res. 2019;39(9):4877-4884. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.13673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods. Ascertainment of Covariates; Statistical Analyses

eFigure. Flowchart of the Study

eTable 1. Age-Standardized Characteristics of Participants Aged 70 or Above in Nurses’ Health Study (1980-2014) and Health Professionals Follow-up Study (1986-2014)

eTable 2. Regular Aspirin Use at or After Age 70 and Risk of Colorectal Cancer Developed at or After Age 70 According to Cancer Stage

eReferences