To the Editor: Chilblain-like lesions (CBLL) have been related to severe acute respiratory coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection,1 although solid microbiological confirmation is still lacking.

We present a prospective cohort study of 37 patients (median age, 14 years) presenting new-onset CBLL during the COVID-19 outbreak in Spain that included (1) SARS-CoV-2 testing (nasopharyngeal polymerase chain reaction [PCR] and serologies) and immunologic profiles for all patients, (2) custom recall antigen experiments and intracellular cytokine production evaluation in selected cases, and (3) skin biopsy for histopathology and immunochemistry (11 samples) and SARS-CoV-2 PCR and electron microscopy (3 cases) (Supplemental Tables I-IV; available via Mendeley at https://doi.org/10.17632/vgvxtcb82c.1).

CBLL mainly affected the toes (Table I ), with other features including dusky erythematoedematous changes on the dorsal surfaces of the toes and fingers (24.32%), purpuric macules (37.83%), and blisters (10.81%). Two patients presented with more obvious signs of distal skin ischemia (Supplemental Figs 1-3; available via Mendeley at https://doi.org/10.17632/vgvxtcb82c.1). In most cases, the lesions fully/partially remitted with topical therapy or no therapy. Only 1 patient presented with signs of retinal vasculitis. Vascular pulses and Doppler ultrasonography showed normal blood flows in the entire series. All biopsy specimens were consistent with pernio, and 54.5% showed complement C3d and C4d deposition around small vessels (Supplemental Fig 4; available via Mendeley at https://doi.org/10.17632/vgvxtcb82c.1). Nasopharyngeal PCR had positive results in 8.1%, and SARS-CoV-2 serology results were positive in just 8.1% of patients. Recall antigen assays showed positive responses in the 3 patients who underwent them (2 with negative SARS-CoV-2 serologies). Five of the 37 patients presented mild anticardiolipin titer elevation. Interferon (IFN) alfa levels were increased in only 1 of 24 tested patients, whereas the rest of the cytokines remained within normal or undetectable levels. No virus was detected on electron microscopy or PCR testing in skin samples.

Table I.

Summary of demographic and clinical features of the patients presenting chilblain-like lesions (N = 37)

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Female | 20 (54.05) |

| Male | 17 (45.95) |

| Mean age, y, mean ± SD | 22.08 ± 15.46 |

| Median age, y | 14 |

| Latency between systemic symptoms and skin lesions, days | 21.76 ± 23.01 |

| Affected areas, n (%) | |

| Toes only | 15 (40.55) |

| Fingers only | 10 (27.03) |

| Toes and sides of feet | 7 (18.92) |

| Toes and heels | 2 (5.40) |

| Toes and fingers | 2 (5.40) |

| Toes, fingers, and sides of feet | 1 (2.70) |

| Associated signs and symptoms, n (%) | |

| Purpuric macules | 14 (37.83) |

| Erythema | 6 (16.21) |

| Pruritus | 5 (13.51) |

| Cold skin | 5 (13.51) |

| Blisters | 4 (10.81) |

| Pain | 3 (8.10) |

| Edema | 3 (8.10) |

| Ulceration and/or necrosis | 2 (5.40) |

| History of systemic symptoms, n (%) | 17 (45.95) |

| Evolution of the lesions (+2 weeks), n (%) | |

| Complete resolution | 16 (43.24) |

| Partial resolution | 14 (37.84) |

| Persistence | 4 (10.81) |

| Worsening | 3 (8.11) |

| Prescribed therapy, n (%) | |

| None | 24 (64.86) |

| Topical corticosteroids | 8 (21.63) |

| Oral corticosteroids | 1 (2.70) |

| Pentoxifylline | 4 (10.81) |

SD, Standard deviation.

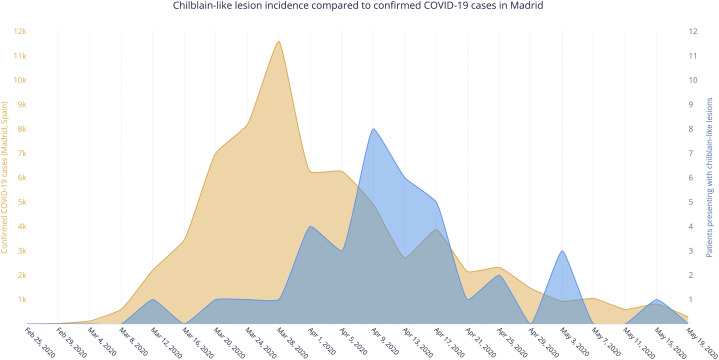

Our patients presented with CBLL in striking parallel to the rise and fall of the COVID-19 pandemic in Madrid, but approximately 2 weeks later (Fig 1 ). The low proportion of positive SARS-CoV-2 serology test results would argue against the idea of a causal relationship between CBLL and SARS-CoV-2 infection. Lack of serologic test accuracy and a more prominent innate immune response might explain this discrepancy.2 However, our preliminary results with SARS-CoV-2 assays suggest that patients could have been exposed to SARS-CoV-2 despite negative routine serologic test results. These patients might have had mild SARS-CoV-2 infection, although the upregulation of the type I IFN pathway could have resulted in the onset of CBLL in genetically predisposed patients. The lower rate of measured IFN alfa could be due to the fact that we measured it in a late phase of infection, according to PCR test results.

Fig 1.

Chilblain-like lesions: the incidence at our center compared with confirmed COVID-19 cases over time in Madrid.

The exact role of SARS-CoV-2 in the development of CBLL, if any, remains unclear.3 We were unable to detect the virus in skin samples; however, the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein has been shown in the endothelial and epithelial cells of eccrine glands.4 Additionally, immune complex deposition can lead to tissue injury through various mechanisms, including complement activation, which could contribute to their pathogenesis.5

In conclusion, if CBLL were secondary to SARS-CoV-2, absence of a more evident humoral response would be highlighted. Recall antigen assays could help clarify this association.

Footnotes

Funding sources: None.

Conflicts of interest: None disclosed.

IRB approval status: Reviewed and approved by the IRB of La Paz University Hospital, Madrid, Spain.

Reprints not available from the authors.

References

- 1.Colmenero I., Santonja C., Alonso-Riaño M., et al. SARS-CoV-2 endothelial infection causes COVID-19 chilblains: histopathological, immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study of seven paediatric cases. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183(4):729–737. doi: 10.1111/bjd.19327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Netea M.G., Joosten L.A.B. Trained immunity and local innate immune memory in the lung. Cell. 2018;175:1463–1465. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kanitakis J., Lesort C., Danset M., Jullien D. Chilblain-like acral lesions during the COVID-19 pandemic (“COVID toes”): histologic, immunofluorescence and immunohistochemical study of 17 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:870–875. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Torrelo A., Andina D., Santonja C., et al. Erythema multiforme-like lesions in children and COVID-19. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:442–446. doi: 10.1111/pde.14246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rojko J.L., Evans M.G., Price S.A., et al. Formation, clearance, deposition, pathogenicity, and identification of biopharmaceutical-related immune complexes: review and case studies. Toxicol Pathol. 2014;42:725–764. doi: 10.1177/0192623314526475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]