Abstract

Objective

Communication related to COVID-19 between provider and the patient/family is impacted by isolation requirements, time limitations, and lack of family/partner access. Our goal was to determine the content of provider communication resources and peer-reviewed articles on COVID-19 communication in order to identify opportunities for developing future COVID-19 communication curricula and support tools.

Methods

A systematic review was conducted using the UpToDate clinical decision support resource database, CINAHL, PubMed, PsycInfo, and Web of Science. The grey literature review was conducted in September 2020 and articles published between January-September 2020 written in English were included.

Results

A total of 89 sources were included in the review, (n = 36 provider communication resources, n = 53 peer-reviewed articles). Resources were available for all providers, mainly physicians, and consisted of general approaches to COVID-19 communication with care planning as the most common topic. Only four resources met best practices for patient-centered communication. All but three articles described physician communication where a general emphasis on patient communication was the most prevalent topic. Reduced communication channels, absence of family, time, burnout, telemedicine, and reduced patient-centered care were identified as communication barriers. Communication facilitators were team communication, time, patient-centered and family communication, and available training resources.

Conclusions

Overall, resources lack content that address non-physician providers, communication with family, and strategies for telehealth communication to promote family engagement. The gaps identified in this review reveal a need to develop more materials on the following topics: provider moral distress, prevention communication, empathy and compassion, and grief and bereavement. An evidence-base and theoretical grounding in communication theory is also needed.

Practice implications

Future development of COVID-19 communication resources for providers should address members of the interdisciplinary team, communication with family, engagement strategies for culturally-sensitive telehealth interactions, and support for provider moral distress.

Keywords: COVID-19, Communication, Health communication, Health care providers

1. Introduction

The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has created a rapid and changing health care landscape that has impacted communication between providers, patients, and families. New challenges created by the pandemic include communicating with patients while utilizing personal protective equipment and establishing new ways for patient and family to connect in the physical absence of families at the bedside [1,2]. While the pandemic has been a catalyst for widespread telehealth use to facilitate communication, technology itself can be a barrier in establishing human connection between providers, patients, and family members especially when discussing sensitive topics such as COVID-19 diagnosis, treatment options, limitations to healthcare resources, and decision-making about end-of-life care [3,4]. Patient- and family-centered communication become essential as virtual care systems rely predominantly on the quality of communication in COVID-19 interactions.

Developing ways to establish ongoing, meaningful communication with patients and family caregivers is one of the biggest challenges emerging from the COVID-19 pandemic [5]. Recommendations for providing patient and family-centered communication include routine assessment of advance care planning, optimal communication with patient and family while wearing personal protective equipment, training in online provider-family communication taking place over phone or video, and supporting family members of COVID-19 patients who are near death [2]. Health systems must adapt new communication tools to maintain family and patient-centered care yet acknowledge clinicians’ limited time and attention to learn new skills [6]. Palliative care has an essential role in the COVID-19 response and is the recognized leader in developing responsive communication tools and initiatives within healthcare systems [7]. An essential role of palliative care teams is to prepare front-line healthcare providers for discussions about SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID19, its diagnosis, treatment decisions, patient and family preferences, and end-of-life care in an empathetic manner that includes less medical jargon and more attention to emotional needs [8]. These discussions also include assessing what patients and families already know and sharing information about COVID-19 using plain language recommendations [5].

To support COVID-19 patients and families, healthcare providers need communication resources that promote ways to engage in compassionate communication with patients and families [3]. The majority of physicians currently in practice learned communication skills while in training, without a curriculum or evidence-based learning techniques, and communication competency for interactions with patients and family members varies [9]. Research in nursing also reveals a need for communication support as nurses find it difficult to preserve family trust and fear they may upset the patient or family [10,11]. As families must remain isolated from COVID-19 patients, communication between providers, patients, and families are reduced and require communication techniques that match new and changing contexts.

It is important that effective, evidence-based provider communication resources are supplied in the context of COVID-19. Treatment guidelines for COVID-19 issued by the National Institutes of Health include advance care planning and goals of care discussions for patients and family members [12], however little is known about the scope of provider communication tools and topics for COVID-19 communication. In order to develop and implement communication strategies to facilitate communication about COVID-19 and care, initial resources provided during the first months of the pandemic require examination. These guidelines were written with limited understanding of how COVID-19 influenced patient, family, and provider experiences during an unprecedented time when physical distancing was suddenly required. Understanding provider, patient, and family experiences in the context of COVID-19 care settings is vital to the development of responsive communication strategies [2]. COVID-19 service experiences, both from the viewpoint of provider, patient, and family, are shaped by health service availability, accessibility, and quality as well as people’s initial expectations and relationship [13].

1.1. Aim

Our goal was to determine the content of provider communication resources and peer-reviewed articles on COVID-19 and communication in order to identify opportunities for developing future COVID-19 communication curricula and support tools. We conducted a systematic review of both grey literature on provider COVID-19 communication resources and peer-reviewed literature of COVID-19 communication.

2. Methods

2.1. Search process

Two methods were used to locate information for this review. First, we searched grey literature by using the UpToDate clinical decision support resource database to search for society guideline links for coronavirus and guidelines for specialty care. Under Palliative Care we chose only US organizations, which included American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, Center to Advance Palliative Care, National Coalition for Hospice and Palliative Care, and National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. Each link was to the organization’s COVID-19 resource page which was reviewed including any links provided by the organization as a COVID-19 resource. Secondly, we systematically searched four databases for peer-reviewed literature: CINAHL, PubMed, PsycInfo, and Web of Science. Working with specialist librarians, we used standardized search strings that combined MeSH terms, free text terms, and broad-based terms for the keywords: ‘Coronavirus’ AND ‘Patient’ OR ‘Family’ OR ‘Provider’ AND ‘Communication’.

2.2. Selection criteria

2.2.1. Grey literature of provider communication resources

Communication resources were included if they were published specifically as a COVID-19 resource, included communication with patient/family, and available as print material. Video and webinar links, connection/picture aids, decision-making tools, public message campaigns, letter to patients/residents, hospital communication checklists, phone scripts for assessing symptoms, and patient education materials were excluded from the review. Resources were entered and organized into Excel and were listed by title, the developing organization, communication topic or goal, and specific focus of the resource.

2.2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria of peer-reviewed articles

This review also aimed to explore peer-reviewed articles on COVID-19 communication. To capture this breadth of material the authors decided to include all primary research of any design (qualitative or quantitative or mixed methods), reviews and case studies, editorials, commentaries, and opinion pieces. Inclusion criteria included original articles in journals with a peer-reviewed process, published between January 1, 2020 – September 1, 2020 that specifically discussed COVID-19 communication including: Provider, Patient, and Family needs and issues for COVID-19 care and Provider, Patient, and Family views or experiences during COVID-19 care. The search was restricted to English language, studies involving adult patients and family members aged 18 and over and did not include studies from developing countries where care settings differ significantly from the US.

2.3. Selection procedure

Two authors (EW and JVG) performed the grey literature search over a two-day period. These same researchers also conducted a screening of peer-reviewed articles by reviewing title and abstracts independently. Through open discussion, coders reviewed differences in coding to reach consensus. All disagreements were resolved with 100% agreement by both coders. Reasons for exclusion or ineligibility were recorded.

2.4. Data extraction and synthesis

First, data from each provider communication resource were extracted into an Excel database. Items for each extraction included reference details (URL, name of organization creating resource), communication context (face-to-face, telehealth), resource type (conversation guide or summary document), communication approach (general or proactive planning before COVID-19 diagnosis), provider audience (physician, nurse, all healthcare providers), intended recipient (to improve communication with patient, family, or both), and whether or not the resource included example clinician statements and questions (yes or no), example questions asked by patient and family, and example responses to patient/family questions. Provider communication resources were assessed for quality using the six domains of best practices for patient-centered communication that identifies role and skills within each domain [14]. Total patient-centered communication scores were calculated based on whether or not best practices were present for role and skill. Two researchers (EW and JVG) independently assessed patient-centered communication domains and resolved differences through iterative discussions.

Second, data from peer-reviewed articles were extracted by one researcher (EW) and checked for accuracy and completeness by the second (JVG). The following information was extracted for each paper: author, journal, article type (summary, research study, or personal narrative), authors’ primary clinical expertise (physician, nurse, social worker, other), whose experience was represented (patient, family, or healthcare provider). Quality was assessed by determining whether or not resources were provided (yes or no), recommendations were evidence-based, and whether or not a theoretical framework was referenced to support article content.

Using a three-stage thematic synthesis [15], authors (EW, JVG) engaged a transparent summary of existing research. In this approach, we first implemented a line-by-line text coding per article, then developed descriptive themes, and ultimately generated analytical themes. The first stage included reading and re-reading the sample (EW, JVG) until article fluency was achieved. A line-by-line coding of the results sections completed the first stage. Moving into the second stage, we sought similarities and differences across line-by-line codes to group ideas and build descriptive themes. In the final stage of thematic synthesis, these descriptive themes were incorporated into synthesized findings that ultimately produced analytical themes. Analytical themes were determined based on the frequency and relevance of codes. Consensus on these generated themes was achieved via iterative discussions between authors.

3. Results

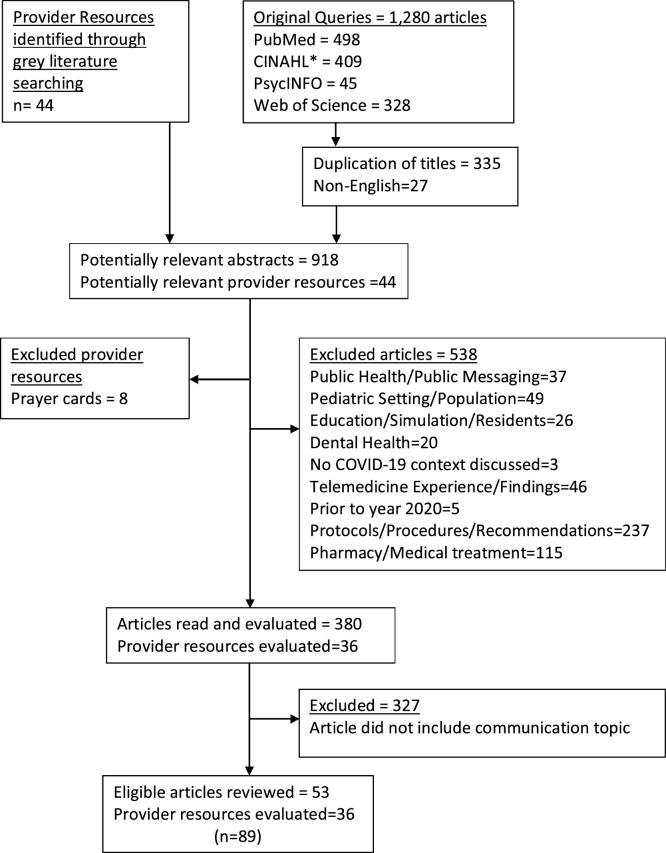

Fig. 1 shows the PRISMA diagram of the search process for grey and peer-reviewed literature. A total of 89 sources were included in the review (36 provider communication resources and 53 peer-reviewed articles).

Fig. 1.

Selection Process of Provider Resources and Peer-Reviewed Articles.

3.1. Characteristics of provider communication resources

Thirty-six COVID-19 provider communication resources were located through the systematic search of grey literature. Documents originated from 22 organizations. Table 1 summarizes provider communication resources included in this review. The sample represented both conversation guides [[16], [17], [18],20,21,[23], [24], [25], [26],28,[30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36],39,42,43] (n = 20) and summary documents [19,22,27,29,37,38,40,41,[44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51]] (n = 16) and primarily provided information on face-to-face communication [16,17,[19], [20], [21], [22],24,24,25,26,[28], [29], [30],33,35,40,45,49,50] (n = 18) or communication in either telehealth and face-to-face encounters [23,32,34,36,41,44,47,48] (n = 8). Communication specific to telehealth encounters were also identified [18,27,31,38,51] (n = 5). The majority of resources targeted healthcare providers generally (n = 19), with nine resources specifically targeting physicians [[16], [17], [18],20,22,24,26,31,33] and two resources specific to nurses [45,48]. Among all resources the most common goal was to improve communication with patients [[16], [17], [18], [19],22,23,25,[27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34],43] (n = 17), followed by communication with both patient and family [20,21,24,35,[31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36],[38], [39], [40], [41], [42],[44], [45], [46],48,50,[45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51]] (n = 16). Four resources [26,37,47,49] were available for communication with families specifically.

Table 1.

Resource type, communication characteristics, and content in provider communication resources (n = 36).

| Resource | Created By | Resource Type | Brief Summary of Resource | Context | Provider Audience | Intended Recipient | Approach | Example statements | Example questions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 Conversation Guide for Inpatient Care [16] | Ariadne Labs | Conversation Guide | To elicit patient preferences in terms of treatment | F2F | Physician | P | Proactive | ✓ | ✓ |

| COVID-19 Conversation Guide for Outpatient Care [17] | Ariadne Labs | Conversation Guide | To elicit patient preferences in terms of treatment | F2F | Physician | P | Proactive | ✓ | ✓ |

| COVID-19 Telehealth Communication Tips [18] | Ariadne Labs | Conversation Guide | How to open a telehealth visit | T | Physician | P | General | ✓ | ✓ |

| COVID-19 Recommendation Aid [19] | Ariadne Labs | Summary Document | Aid for making recommendations for outpatient care | F2F | All | P | Proactive | ✓ | ✓ |

| COVID-19 Conversation Guide for Crisis Standards [20] | Ariadne Labs | Conversation Guide | Crisis standards for treating patients | F2F | Physician | P, F | Proactive | ✓ | ✓ |

| COVID-19 Conversation Guide for Long-Term Care [21] | Ariadne Labs | Conversation Guide | To elicit patient preferences in terms of treatment | F2F | All | P, F | Proactive | ✓ | ✓ |

| A Physician’s guide to COVID-19 [22] | American Medical Association | Summary Document | Encourages physicians to communicate updates, preparedness plan, debunk myths, share facts | F2F | Physician | P | General | ||

| Advance Care Planning [23] | Prepare for your care | Conversation Guide | Engage in advance care planning for preventive care | F2F, T | All | P | Proactive | ✓ | ✓ |

| Best Case/Worst Case: ICU (COVID-19) [24] | University of Wisconsin-Madison | Conversation Guide | Intensive care unit discussions about prognosis | F2F | Physician | P, F | Proactive | ✓ | ✓ |

| Communication skills for bridging inequity v2.1 [25] | Vital Talk | Conversation Guide | Addressing racism | F2F | All | P | General | ✓ | ✓ |

| Goals of Care COVID Script [26] | Vital Talk | Conversation Guide | Goals of Care | F2F | Physician | F | Proactive | ✓ | ✓ |

| Patient Priorities Care in an Age-Friendly Health System Telehealth Guidance for COVID-19 Communications [27] | Baylor College of Medicine/Geriatrics | Summary Document | Telehealth clinic visits | T | Not stated | P | General | ✓ | ✓ |

| Honoring Previously Determined Preferences for Medical Care [28] | Oregon Health & Sciences University | Conversation Guide | Preferences for medical care | F2F | Not stated | P | Proactive | ✓ | ✓ |

| Medical Priorities for Treatment Options [29] | Respecting Choices | Summary Document | Discussing treatment options | F2F | Not stated | P | General | ||

| Palliative Communication Guide for Interpreters [30] | Center to Advance Palliative Care | Conversation Guide | Learn to be culturally sensitive in patient encounters | F2F | Interpreter | P | General | ✓ | ✓ |

| Proactive call to patients with COVID at home script [31] | Vital Talk | Conversation Guide | Script for telephone calls to patients at home with COVID-19 | T | Physician | P | Proactive | ✓ | |

| Proactive care planning for COVID-19 [32] | Respecting Choices | Conversation Guide | Discussing care plan with at-risk patient | F2F, T | All | P | Proactive | ✓ | ✓ |

| Saying Goodbye [33] | Vital Talk | Conversation Guide | What to say to family when a patient is dying | F2F | Physician | P | General | ✓ | |

| Introducing and Scheduling Proactive Care Planning [34] | Respecting Choices | Conversation Guide | Proactive conversation about preferences for care | F2F, T | All | P | Proactive | ✓ | ✓ |

| Communication Skills for COVID-19: Patient Dying Despite Critical Care Support [35] | Lindenberger, Helman, Mier | Conversation Guide | Ventilator withdrawal shared decision-making conversation | F2F | All | P, F | General | ✓ | ✓ |

| COVID Ready Communication Playbook [36] | Vital Talk | Conversation Guide | Comprehensive guide that covers screening, deciding, notifying, proactive planning, etc. | F2F, T | All | P, F | Proactive | ✓ | |

| Working with Families Facing Undesired Outcomes during the COVID-19 crisis [37] | Social Work Hospice & Palliative Care Network | Summary Document | General suggestions for working with families | Not specified | All | F | General | ||

| A Quick Guide to Providing Telechaplaincy Services [38] | Association of Professional Chaplains | Summary Document | How to deliver telehealth care for chaplains | T | Chaplain | P, F | General | ✓ | |

| CALMER Goals of Care: A Discussion Guide [39] | Vital Talk | Conversation Guide | Motivate patient to choose a proxy and discuss goals of care | Not specified | All | P, F | General | ✓ | ✓ |

| Chaplaincy in the Time of COVID-19 [40] | Spiritual Care Association | Summary Document | Defines communication and supportive listening strategies | F2F | Chaplain | P, F | General | ✓ | ✓ |

| COVID-19 Communication Art Statements [41] | Academy of Communication in Healthcare | Summary Document | Skills to help build trust and increase resilience | F2F, T | All | P, F | General | ✓ | ✓ |

| COVID-19 Communication: Quick Tips to Connect [42] | Academy of Communication in Healthcare | Conversation Guide | Quick reference guide on general communication approach with exmaples | Not specified | All | P, F | General | ✓ | |

| ACP Conversation Guide: Outpatients High Risk [43] | SFVA Hospice and Palliative Care Service | Conversation Guide | Advance care planning conversation for high-risk patients | Not specified | Not stated | P | Proactive | ✓ | ✓ |

| COVID Language Guide [44] | Kelemen, Altillio, Leff | Summary Document | Includes responses to common questions, virtual family meetings, and end-of-life topics | F2F, T | All | P, F | General | ✓ | ✓ |

| Communication Guide for Nurses and Others During COVID-19 [45] | End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium | Summary Document | Defines communication role, offers communication tools including spiritual assessment | F2F | Nurse, All | P, F | General | ✓ | ✓ |

| About COVID-19 [46] | Health Literacy Project/Harvard Health Publishing | Summary Document | Gives plain language for answering patient/family questions | Not specified | All | P, F | Proactive | ✓ | |

| Person-centered Guidelines for Preserving Family Presence in Challenging Times [47] | Planetree International | Summary Document | Encourages proactive communication with family | F2F, T | All | F | General | ||

| Communication with Patients with COVID-19 [48] | Hospice & Palliative Nurses Association | Summary Document | Defines nurse’s role in communication, behaviors valued by patient/family, highlights assessment | F2F, T | Nurse | P, F | General | ✓ | |

| COVID-19 and Patient- and Family-Centered Care [49] | Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care | Summary Document | Communicate changes to policy, maintain connection with family | F2F | All | F | General | ||

| Spiritual Care – Brief COVID-19 Guidance for Healthcare Workers [50] | University of California, San Diego Health | Summary Document | Acknowledge legacy, recognize regret, affirm dignity, address concerns | F2F | All | P, F | General | ✓ | |

| Telehealth Visit Outline [51] | Reach PC | Summary Document | Tips for start and close of telehealth visit | T | All | P, F | General | ✓ |

F2F = Face-to-face communication; T = Telemedicine: P = Patient; F = Family.

Twenty-one resources provided a general approach to COVID-19 communication [18,22,25,27,29,30,33,35,[37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42],44,45,[47], [48], [49], [50], [51]] and fifteen resources provided a proactive approach aimed at addressing decision-making prior to a COVID-19 diagnosis [16,17,[19], [20], [21],23,24,26,28,31,32,34,36,43,46]. Thirty resources included examples for clinicians and were most likely to provide example clinician statements [16,20,21,[23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28],[30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36],[38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46],50,[48], [49], [50], [51]]. Three resources [37,47,49] did not provide example statements or questions and only two resources provided example questions asked by patients or family [44,46].

Sixteen resources focused communication on care planning. These resources included ways to elicit patient preferences [16,17,21,32] and conversations to select treatment options [28,29]. One resource addressed selecting options and patient well-being [19]. General goals of care discussions were addressed in three resources [26,34,36]; two resources centered on choosing a proxy [39,41], advance care planning [23,43], and prognosis discussions in the intensive care unit [24]. One resource addressed discussing limited resources and treatment options with family [20].

Seven resources included content that addressed working with families [44,47], including family assessment [48], family meetings [45], learning about family concerns [37], and communicating policy changes and updates [22,49]. Virtual communication in telehealth platforms was the primary emphasis in six resources which highlighted how to open and close telehealth visits [18,51], topics to discuss [27,31], and telehealth guide for tele-chaplaincy services [38]. Four resources emphasized general provider communication best practices [42], including plain language materials [46], addressing racism [25] and cultural sensitivity [30]. Communicating about dying was present in four resources which focused on removing the ventilator [35] and what to say to a family when a patient is near death [33,50]. One resource was a general COVID-19 communication summary document for chaplains [40].

3.1.1. Assessment of patient-centered communication practices

Content of each resource was compared against the six domains of patient-centered communication practices defined in terms of role and skill (Supplemental Table 1). Within the best practice definitions, only four resources scored 75% or higher [19,31,36,42], followed by 18 resources scored between 50–74%, and 12 resources scored 25% or less. The average score was 38%.

3.2. Characteristics of peer-reviewed articles

Fifty-three articles focusing on COVID communication were identified (Table 2 ). The most common publication type was an article summary where communication was emphasized, defined, or discussed as a key element of the COVID-19 context. Five personal narratives were also included: one article summarized a doctor’s experience as a COVID-19 patient [88] and four articles discussed the ways that physician communication with patients and families has changed pre-COVID to now [71,76,81,96]. Finally, the sample included three research studies: an editorial included findings of a survey of 376 healthcare providers empathic attitudes and psychosomatic symptoms that concluded that clinician’s higher empathy exposed them to more psychological suffering [56]; qualitative interviews with 9 families about challenges in palliative care interventions [62]; email or telephone interview with 8 physicians and 48 cancer patients that summarized 8 oncology-specific COVID-19 scenarios which patients responded to with anger, fear, and anxiety [68].

Table 2.

Characteristics of included peer-reviewed articles (n = 53).

| Publication and Overall Purpose | Journal and Publication Type | Authors’ Primary Clinical Expertise | Patient, Family, or Provider Experience | Primary Communication Topic | Resources Provided | Evidence-based | Theoretical Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adams [52] | Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, Summary with case | Physician | Provider | Goals of care | ✓ | ||

| Challenges and recommendations for goals of care discussions | |||||||

| Chen [53] | Critical Care Alert, Summary | Physician | Provider | Moral distress | |||

| Ethical considerations in the intensive care unit | |||||||

| Akgun, Shamas, et al [54] | Heart & Lung, Summary | Physician | Provider | Grief and bereavement | |||

| Practical and actionable communication strategies | |||||||

| Back, Tulsky, Arnold [55] | Annals of Internal Medicine, Summary | Physician | Provider | Advance care planning | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Pro-active care planning, explaining resource allocation | |||||||

| Barello, Palamenghi, Graffigna [56] | Patient Education and Counseling, Survey | Other | Provider | Empathy and compassion | ✓ | ||

| “C.O.P.E.” Project (COVID 19 – related Outcomes of health Professionals during the Epidemic) | |||||||

| Bergman, et al. [57] | Annals of Family Medicine, Summary | Physician | Provider | Telehealth | ✓ | ||

| Possible ways relationships develop in different health care encounters | |||||||

| Bowman, et al. [58] | Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, Summary | Nurse | Provider | General patient communication | ✓ | ||

| Training gaps in symptom management and patient communication | |||||||

| Brucato [59] | Journal of Communication in Healthcare, Interview | Physician | Provider | General patient communication | |||

| Importance of communication as part of effective pandemic response in clinical settings | |||||||

| Carico, Sheppard, Thomas [60] | Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, Summary | Other- Pharmacy | Provider | Prevention | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Overview of Health Belief Model with a guide to patient communication in these uncertain contexts | |||||||

| Cordero & Davis [61] | Journal of Patient Experience, Summary | Physician | Provider | General patient communication | |||

| Offers practical tools for communication that can mitigate interpersonal bias | |||||||

| Dhavale et al. [62] | Indian Journal of Palliative Care, Qualitative | Social Work | Provider | General patient communication | |||

| Describe challenges of patients and caregivers during the lockdown due to COVID-19 pandemic | |||||||

| Diamond, Jacobs, Karliner [63] | Patient Education and Counseling, Editorial | Physician | Provider | General patient communication | ✓ | ||

| Algorithm approach to overcome language barrier for limited English proficient patients | |||||||

| Fan, et al. [64] | World Journal of Clinical Cases, Summary | Nurse | Patient | General patient communication | |||

| Common issues of being in isolation were raised and strategies offered | |||||||

| Feder et al. [65] | Heart & Lung, Summary | Physician | Provider | General patient communication | ✓ | ||

| Application of core palliative care principles during COVID-19 crisis | |||||||

| Finset, et al. [66] | Patient Education and Counseling, Summary | Other- Multidisciplinary | Provider | Prevention | |||

| Implementation of health communication in the COVID-19 crisis | |||||||

| Gaur, et al. [67] | Journal of Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine, Summary | Physician | Provider | Advance care planning | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Proposes an evidence-based COVID-19 Communication and Care Planning Tool allowing for informed consent and shared decision making | |||||||

| Gharzai, et al. [68] | Journal of the American Medical Association, Qualitative | Physician | Provider | Prognosis/End of life care | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Identify clinical scenarios that pose communication challenges with patient reactions | |||||||

| Gibbon, et al. [69] | Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, Summary | Physician | Provider | Prognosis/End of life care | ✓ | ||

| Developed a point-of-care tool to summarize outcome data for critically ill patients with COVID-19 | |||||||

| Hart, et al. [70] | Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, Summary | Physician | Family | Goals of care | ✓ | ||

| Toolbox of strategies for supporting family-centered in-patient care during COVID-19 | |||||||

| Hauser [71] Health care |

Hasting Center Report, Personal Narrative | Physician | Provider | General patient communication | |||

| professionals disconnect with patients and families | |||||||

| Hector [72] | Caring for the Ages: Journal of Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine, Summary | Social Work | Provider | Grief and bereavement | ✓ | ||

| Proactive communication and collaboration with families during COVID-19 | |||||||

| Hill [73] | The Diabetic Foot Journal, Summary | Other | Provider | Goals of care | |||

| Explores the role and influence of patient and healthcare professional communication in the context of diabetes and diabetes-related foot problems | |||||||

| Holstead & Robinson [74] | Journal of Clinical Oncology, Summary | Physician | Provider | Telehealth | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Strategies to help maintain a high standard of care and communication with patients | |||||||

| Houchens & Tipirneni [75] | Journal of Hospital Medicine, Summary | Physician | Provider | General patient communication | |||

| Challenges arising from communicate barriers in the time of COVID-19 | |||||||

| Julka-Anderson [76] | Journal of Medical Imaging and Radiation Sciences, Personal Narrative | Other-Radiation Therapist | Provider | Telehealth | ✓ | ||

| Adapting communication skills | |||||||

| Lewin [77] | Canadian Medical Association Journal, Summary | Physician | Provider | Goals of care | |||

| Making treatment recommendations during COVID-19 pandemic | |||||||

| Lewis [78] | American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Medicine, Summary with Case | Physician | Provider | Goals of care | |||

| Facilitating goals-of-care during the COVID-19 pandemic | |||||||

| Lu [79] | Journal of Palliative Medicine, Summary | Physician | Provider | Goals of care | ✓ | ||

| Establishing communication strategies for kidney disease in context of COVID-19 | |||||||

| Marra, et al. [80] | Critical Care Bio Medical Central, Summary | Physician | Provider | General patient communication | |||

| Highly compromised verbal and nonverbal communication in the COVID-19 pandemic | |||||||

| McNairy, Bullington, Bloom-Feshbach [81] | Journal of General Internal Medicine, Personal Narrative | Physician | Provider | Empathy and compassion | |||

| Recommend using technology to improve doctor-patient communication during COVID-19 | |||||||

| Montauk, Kuhl [82] | Psychological Trauma, Summary | Nurse | Provider | Grief and bereavement | |||

| Recommendations to support family members of COVID-19 patients in the ICU | |||||||

| Negro, Mucci, et al [83] | Intense & Critical Nursing, Summary | Nurse | Provider | Telehealth | ✓ | ||

| Recommend video conference with family of COVID-19 patients in the ICU | |||||||

| Nemetz, Urbach, Devon [84] | Journal of Medical Internet Research, Summary | Physician | Provider | Telehealth | |||

| To resolve communication challenges including preparation, professionalism, empathy, respect, and the virtual physical examination | |||||||

| Pahuja, Wojcikewych [85] | Journal of Palliative Medicine, Summary with Case | Physician | Provider | Prognosis/End of life care | |||

| To present a case of inadvertently created barriers to routine palliative intervention | |||||||

| Prestia [86] | Nurse Leader, Summary | Nurse | Provider-Leadership | Moral distress | |||

| Offers suggestions on staying resilient and upholding one’s moral obligations during COVID-19 | |||||||

| Raftery, Lewis, Cardona [87] | Gerontology, Summary | Nurse | Provider | Advance care planning | |||

| Proposes nurse-led and allied health-led ACP discussions to ensure patient and family inclusion and understanding of the disease prognosis, prevention of overtreatment, and potential out comes in crisis times | |||||||

| Ramachandran [88] | Anesthesia Reports, Personal Narrative | Physician | Patient | Empathy and compassion | |||

| To present a junior doctor’s view of how COVID-19 was managed by the health system and a personal view of his COVID-19 experience | |||||||

| Rathore, Puneet, et al [89] | Indian Journal of Palliative Care, Summary | Physician | Empathy and compassion | ✓ | |||

| Proposes a model of CARE approach for providing holistic care during the times of pandemic | |||||||

| Ritchey, Foy, McArdel [90] | American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Medicine, Summary with Case | Physician | Provider | Telehealth | ✓ | ||

| Describes a case illustrating the successful use of palliative care telehealth in the care of a COVID-19-positive patient at the end of life | |||||||

| Robblee, Buse, et al [91] | Headache, Summary with scenarios | Physician | Provider | Moral distress | |||

| To describe 11 scenarios of unhelpful and dysfunctional messages heard by the authors and their colleagues during the COVID-19 pandemic | |||||||

| Rosenbluth, Good [92] | Journal of Hospital Medicine, Summary | Physician | Provider | General patient communication | |||

| To discuss challenges during COVID-19 pandemic | |||||||

| Schlögl, A. Jones [93] | Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, Summary | Physician | Provider | Empathy and compassion | |||

| To provide recommendations to improve mindful communication | |||||||

| Schrager [94] | American Academy of Family Physicians, Summary | Physician | Provider | Empathy and compassion | |||

| To present recommendations for providers to stay connected with patients during COVID-19 pandemic | |||||||

| Selman, Chao, et al. [95] | Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, Summary | Other: Ph.D. Researchers | Provider | Grief and bereavement | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Recommendations for hospital clinicians on bereavement support | |||||||

| Simpson, Porter [96] | Houston Methodist DeBakey Cardiovascular Journal, Personal Narrative | Physician | Provider | General patient communication | |||

| To provide recommendations to | |||||||

| improve patient-provider relationship during COVID-19 pandemic | |||||||

| Sirianni, Torabi [97] | Canadian Family Physician, Summary | Physician | Provider | Goals of care | ✓ | ✓ | |

| To provide recommendations to improve communication during COVID-19 pandemic | |||||||

| Siropaides, Sulistio, Reimold [98] | Circulation, Summary | Physician | Provider | Prevention | ✓ | ||

| To provide recommendations to optimize communication to patients with cardiovascular disease during the COVID-19 pandemic | |||||||

| Sivashanker, Mendu, et al [99] | The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, Summary | Physician | Provider | Prevention | ✓ | ||

| To develop a pragmatic COVID-19 exposure disclosure checklist to improve communication | |||||||

| Stilos, Moore [100] | Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal, Summary | Nurse and Physician | Provider | Prognosis/end of life care | |||

| To discuss the challenges for communication during COVID-19 pandemic | |||||||

| Ting, Edmonds, et al [101] | BMJ, Summary | Physician | Provider | General patient communication | ✓ | ||

| To provide recommendation for communication and palliative care during COVID-19 | |||||||

| Underwood [102] | Journal of Aesthetic Nursing, Summary | Other: CEO | Provider | General patient communication | |||

| Reinventing patient communication to stay connected | |||||||

| Wallace, Wladkowski [103] | Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, Summary | Social Work | Provider | Grief and bereavement | ✓ | ||

| To describe the relationship of the COVID-19 pandemic to anticipatory grief, disenfranchised grief, and complicated grief for individuals, families, and their providers | |||||||

| Wolf, Waissengrin [104] | The Oncologist, Summary with Case | Physician | Provider | Telehealth | ✓ | ||

| To provide recommendations for telehealth communication |

The articles were published in the United States (n = 41), United Kingdom (n = 5), India (n = 2), Canada (n = 2), Singapore (n = 1), Australia (n = 1), and Israel (n = 1). The majority of authors were physicians (64%), followed by nurses (13%), research groups or multidisciplinary research teams (10%), social workers (5%), and other healthcare providers (8%). All but three articles described the communication experiences of physicians (94%). Communication resources or references to resources were provided in 58% of articles, with less than 13% providing an evidence-base or theoretical framework for recommended communication strategies.

A variety of communication topics were covered in the articles, with the most prevalent topic a general emphasis on patient communication (25%) where lessons learned were highlighted [59,64,71,75,80,92], barriers [96] and resources [58] shared culture humility [61] and equitable care [63] addressed, and communication in palliative care settings emphasized [62,65,101]. Goals of care discussions and telehealth were the next most common communication topics (13%, respectively). Recommendations for goals of care discussions were highlighted [52,97,77] and included end-of-life context [78], dialysis decision-making [79], family-centered care [70], and diabetes [73]. Published articles about telehealth focused on use in the intensive care unit [83], surgery [84], cancer care [74,76,104], and palliative care [77] and centered on social connectedness [57].

Empathy and compassion were the next most common communication topic (11%) with an emphasis on staying connected to patients [81,94,102] by treating mind, body, and spirit [89] in response to the lack of nonverbal communication [93]. This challenge was underscored by one physician’s personal experience [88]. Grief and bereavement were also a central communication topic in 10% of the sample, with articles addressing communication with family [72,82], bereavement risk factors [95], types of grief [103], and ways to mitigate fear and suffering [54].

There were four articles each in the area of prevention, prognosis/end-of-life care, and moral distress. The clinician’s communication role was described as part of prevention efforts to help the public manage the overflow of education [66,99], with a specific focus on the pharmacist’s role ([60] and cardiac care [98]. Barriers to end-of-life care [68,58] were described, with one article addressing cancer care settings [99] and another offering a prognostic communication for clinicians [69]. Leadership [86], ethics [53], and interprofessional communication [91] were central to discussions about communication and ethics and how they influence symptoms of moral distress [56]. Finally, the sample included two articles on advance care planning [55,67].

3.3. Communication barriers in COVID-19 care

Six analytical themes with corresponding subthemes identifying communication barriers were established: reduced communication channels, family/partner cannot be present, time, burnout for providers, telemedicine, and reduced patient-centered care. Subtheme frequencies were highest within themes of family/partner cannot be present (23 articles), reduced patient-centered care (18 articles), and reduced communication channels (17 articles). Increased anxiety and fear for family made worse by isolation (7 articles) was the most frequent subtheme under the theme heading of family/partner cannot be present. Complementing that finding, isolation increasing fear and anxiety for patients (6 articles) was the most common subtheme under the reduced patient-centered care theme heading. Personal protective equipment interrupting verbal messages and nonverbal communication was the most frequent subtheme (10 articles) under the theme of reduced communication channels.

Table 3 summarizes the six communication barriers. The most common communication barrier during COVID-19 pandemic is that patients and family members could not recognize the face and voice of their healthcare providers due to masking and the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) [59,71,75,76,80,81,84,93,96,100,101]. Frontline health workers in Italian emergency units in March 2020 experienced reduced communication channels resulting from masks, goggles, and face shields and struggled to recognize faces and voices [59]. Physicians in Switzerland interacted with elderly patients with hearing aids who had difficulty understanding masked voices [93]. A second communication barrier during the COVID-19 pandemic is that patients are anxious and fearful because they are left alone to face illness and their family cannot be physically present [52,53,58,64,73,77,79,82,83,85,88,89]. For example, COVID-19 patients with a diagnosis of end stage renal failure were challenged to make dialysis decisions without their family members present to help comprehend language and provide emotional support [79].

Table 3.

Barriers to COVID-19 communication identified from peer-reviewed articles.

| Communication Barriers | ||

|---|---|---|

| Main themes | Subthemes | References |

| Reduced communication channels | Nonverbals minimized on phone/videophone | [52,74,76,84] |

| Trust inhibited for family | [52] | |

| Cannot visually identify providers under PPE | [59,93] | |

| PPE (respirator and/or face shield) muffling voice and facial nonverbals | [71,75,76,80,81,84,93,96,100,101] | |

| Family/Partner cannot be present | Increased patient anxiety and fear made worse with isolation/uncertainty | [52,64,73,77,79,82,89] |

| Loss of family voice/advocate/decision making | [53,58,82,83,85,88] | |

| Inability for goodbyes | [53,54] | |

| No access to patient/updates/information | [58,59,62,78,81,82] | |

| Unable to engage last wishes | [62] | |

| Family meetings less possible | [83] | |

| Time | Reduction in time to provide care | [55] |

| Timing, post-mortem contact | [59] | |

| Clinician bias over resources, treatment, consensus of patient | [69] | |

| Clinician out of time to learn new skills | [70] | |

| Lack of advanced care planning completed with dying patients | [95] | |

| Lack of training | [97] | |

| Empathy/Burnout for providers | Risk factor | [56,80] |

| Moral distress | [86] | |

| Lack of training and role clarity for end-of-life conversations | [87,100] | |

| Exposure without PPE | [91] | |

| Organization needs | [99,103] | |

| Telemedicine/Phone | Relationship distance (nonverbals) | [57,100,104] |

| Family with no availability | [70] | |

| Family with limited tech literacy | [70,74] | |

| Patient missing glasses/hearing aids | [70,101] | |

| Message/understanding is too minimal | [82] | |

| Policy limitations | [90] | |

| Reduced patient-centered care | Limits to other needed care (i.e. cancer) | [62,68,98] |

| Unable to engage last wishes | [62] | |

| Tailored and understandable messages/Interpreters needed | [63,66,88] | |

| Shift from individual patient to societal level of care | [65] | |

| Privacy impossible at times | [78] | |

| Isolation causes increased fear and anxiety/uncertainty | [79,81,85,89,98,100] | |

| Rounds not possible | [81,94] | |

| Worry about discharge (care at home, finances) | [64] | |

Running out of time was the third most common communication barrier during the pandemic [55,59,69,70,95,97]. Even for providers who have a deep understanding and experience of communication with the patient/family, they are overworked and lack the time to talk to the patient/family in new situations presented by the pandemic [55,59]. During the pandemic, less completion of advance care planning (ACP) prior to hospital admission was identified and resulted in prolonged grief because families were not allowed to see their loved ones in the midst of active dying or upon post-mortem [95]. The fourth communication barrier is an intense emotional impact on patient/family and providers [56,80,86,87,91,99,100,103]. Witnessing high numbers of suffering/deaths in a short period of time brought complicated grief for providers during COVID-19 pandemic [103]. Prestia (2020) suggests truthful, mindful and relevant communication for nurses when they talk with COVID-19 patients and their families to minimize the negative impact of moral distress [86].

Telehealth offers a pathway to connect COVID-19 patients and their family members, especially when social distancing and isolation are barriers to care delivery. However, telehealth itself can become a communication barrier [57,70,74,82,100,104], and providers should not solely rely on telehealth when communicating to patient/family. For example, for patients and their family members who live in rural areas without reliable internet access, providers should prioritize patient/family’s needs and enhance engagement during communication in each encounter [70]. Telehealth created an extra layer of barriers when communicating with family members regarding medical interventions, the consequences of those decisions, and subsequent transition to end-of-life care because families needed constant and continual real-time discussions in order to comprehend unfolding medical information [82].

The last communication barrier was decreased patient-centered care [[62], [63], [64], [65], [66],78,79,81,85,89,94,98,100]. Due to resource strain and the need to protect society from the impact of COVID-19, providers may not be able to provide patient-centered care [65]. For example, in addition to information of COVID-19 treatment, providers should provide COVID-19 patients and their families with clear and culturally sensitive information about how to take care of themselves to quarantine or self-isolate [63].

3.4. Communication facilitators in COVID-19 care

Five analytical themes with corresponding subthemes identifying communication facilitators were established: strategize team communication, time and communication, patient-centered communication, family-centered communication, and communication training/resources. Subtheme frequencies were highest within themes of communication training/resources (23 articles), patient-centered communication (22 articles), followed by family-centered communication (14 articles). Subthemes were highly diversified across themes, with the highest frequency subthemes established under patient-centered communication; subthemes of invest in relationship with patient (6 articles) and empathize/acknowledge emotion (5 articles) were most dominant. Table 4 summarizes communication facilitators.

Table 4.

Facilitators for COVID-19 communication identified from peer-reviewed articles.

| Communication Facilitators | ||

|---|---|---|

| Main themes | Subthemes | References |

| Strategize team communication | Designate communication responsibility | [52] |

| Team reflection time | [52,53] | |

| Maintain active engagement with patient situations | [92] | |

| Engage palliative care service | [54] | |

| Integrate technology with patient as a team | [90] | |

| Time and communication | Communicate with family before intubation | [53] |

| Let patient know that more communication is coming | [76] | |

| Prioritize communication | [92] | |

| Accomplish communication with technology | [92] | |

| Patient-centered communication | Invest in relationship with patient | [57,66,68,82,94,104] |

| Adapt technology to share care plan | [64,81,82] | |

| Empathize/acknowledge | [65,66,68,82,88] | |

| Share treatment options openly/honestly and clearly | [69,80,89] | |

| Practice cultural humility | [73] | |

| Align with patient values in decision making | [77,97] | |

| See your patients | [94] | |

| Seek patient privacy | [104] | |

| Family-centered communication | Obtain information needs and preferences from family/communication plan | [53,66,72] |

| Hold family meeting(s) however possible | [54] | |

| Include family by using technology | [64,82] | |

| Empathize/acknowledge | [65,66,82] | |

| Enable family presence in person or with technology by communicating risks and options | [70] | |

| Share reasons for policies about access and PPE | [72] | |

| Practice cultural humility | [73] | |

| Align with family values in decision-making | [77] | |

| Identify substitute decision-maker | [97] | |

| Communication training resources | Vital Talk | [55,58] |

| SPIKES | [74,104] | |

| Attention to eye expression/nonverbals | [59] | |

| Develop and share a question/prompt list to use with patients | [60] | |

| Use interpreters/LEP (Limited English Proficiency) materials/algorithm | [61,63] | |

| Bad News resource | [87] | |

| COVID advance care planning tool, ACP guide | [67,87] | |

| Ask-Tell-Ask | [68] | |

| Rely on words spoken, tone, and silences/ lay terms | [71,88,101] | |

| Strategies to communicate with compassion to team, patient, and family | [75] | |

| 3 Stage Protocol for goals of care | [79] | |

| Checklist for video calls | [84] | |

| PPERV (Preparation, professionalism, empathy, respect, virtual physical exam) | [84] | |

| “Trustful, mindful, relevant, sensitive communication” | [86,95] | |

| What to do/What to say | [91] | |

| ABC (Attend mindfully, Behave Calmly, Communicate Clearly) | [93] | |

4. Discussion and conclusion

4.1. Discussion

In this review, peer-reviewed articles and provider resources were limited to information about face-to-face interactions and focused primarily on physician-patient communication. Articles predominantly highlighted the connection between physician and patient and resources were primarily for physician audiences. However, patient communication is often compromised or not at all possible due to advanced COVID-19 disease processes and findings from this study demonstrate that COVID-19 communication barriers pertain more to communication with family. Few provider resources reviewed in this study focused on communication with families, with even less content available for telehealth interactions.

Despite the missing content in provider resources to support family communication, family-centered communication was strongly identified as a main communication facilitator in COVID-19. Absence of family or inability to secure proxy communication created gaps and providers were in positions to rely on anyone they could link as a relative to the patient. Findings here underscore the importance of early palliative care which includes family assessment. Palliative care providers are experts in supporting family members by facilitating critical conversations, discussing goals of care, and working to identify patient’s desires. When surrogates are more quickly identifiable, surrogate confidence in knowing the patient’s wishes can be a barrier to advance care planning discussions [105] and this should be addressed in providers communication resources for COVID-19 care. Infection-control policies for COVID-19 often present barriers to communication with surrogate decision makers, and most surrogates will not be physically present when discussing treatment options with clinicians. Many decision-making discussions will occur via telecommunication [12].

Although telemedicine was considered an effective resolution to communication restrictions, the inconsistent availability of telemedicine was a noted communication barrier identified in peer-reviewed articles. Current research indicates that understanding human factors in technology adoption, including user awareness, acceptance and readiness, and skill impact the communication that is produced [106]. It has previously been noted that a lack of consideration of an individual’s characteristics and social environment is a barrier to integrating telemedicine/telehealth tools [107]. Barriers to technology adoption should be addressed in COVID-19 care and telehealth communication assessment is needed, especially in diverse patient and family populations [108].

With little known about COVID-19, healthcare providers do not know how or have no way to explain patient prognosis and in some cases do not have time to engage the patient/family about goals, shared decision-making, or transitioning to end-of-life care [62,85,86,95]. When patients near death in the hospital, families long for proactive communication, shared decision-making, and personalized end-of-life care [109]. The loss of touch as nonverbal communication in patient-provider interactions as a result of the pandemic [110] requires healthcare providers to be creative in nonverbal communication and places an even greater emphasis on creating new ways for nonverbal expression. This is especially salient in telehealth interactions as providers’ culturally sensitive communication influences a family’s perception of quality of care and experience of end-of-life care [111]. As communication resources are developed for providers, greater attention is needed for communication practices that acknowledge cultural diversity [112]. This is essential as medical education includes a lack of experiential exposure to different cultures resulting in communication miscues [113].

Additionally, this review also showed that healthcare providers suffer from high emotional exhaustion due to insufficient communication skills and an absence of communication efficacy during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, none of the current provider communication resources fulfill the needs of decreasing moral distress or compassion fatigue of healthcare providers, nor do they account for the range of disciplinary providers interfacing with patients and families in this public health crisis. E-mental health interventions for COVID frontline workers are currently available and consist of social media platforms, online resources, and mobile applications, however these resources have limited empirical evaluation [114]. Resources and tools are needed to address provider stress from overloaded work and exposure to COVID-19 without PPE. Research has shown that there are no major differences in the prevalence of burnout between physicians and nurses and improving communication skills is one way to reduce symptoms of burnout [115]. Findings here highlight team communication as a communication facilitator. Notably, physicians play an important role in patient care and establishing organizational culture for collaboration with other physicians and team members [116].

Finally, the amount of materials available in the grey literature demonstrates the immense need for COVID-19 resources for healthcare providers which was further evidenced by details of the communication barriers in peer-reviewed articles. However, there remains a lack of evidence-base or theoretical framework for communication resources and information summarized in peer-reviewed articles. Best practices for patient-centered communication were primarily missing in communication resource content and peer-reviewed articles rarely included a summary of evidence-based work for communication recommendations or reference a theoretical framework. As we continue to learn more about COVID-19 and adjust to communication changes in the clinical setting, future work on understanding interactions about COVID-19 should be grounded in communication theory.

4.2. Conclusion

Gaps exist within provider communication resources and peer-reviewed accounts of the COVID-19 communication context. A comparison of topics addressed in provider resources and peer-reviewed articles demonstrates a need to develop more materials on provider moral distress, prevention communication, empathy and compassion, and grief and bereavement. Of significance is the lack of content (research or resource) that addresses nurse experiences and needs, communication with family, and telehealth interactions that promote family engagement and cultural sensitivity.

4.3. Practice implications

Three important findings shape future development of communication support for frontline providers working in any health crises (e.g., COVID-19, Ebola, SARS). First, the majority of sources in this review were physician-centered. Communication strategies demonstrated a specific focus on topics typically discussed and initiated by the physician and did not always include ways to respond when topics are initiated by patient/family, which is a more common communicative role for nurses, social workers, and other healthcare team members. Second, there continues to be a lack of evidence-base for communication support materials. Both provider communication resources and peer-reviewed articles focused the majority of content on care planning, goals of care, and general communication practices from personal and institutional experiences. More research is needed to evaluate whether these ‘best practices’ are also effective for patients and families; current materials reflect only the voice of the provider (namely the physician) and there is a need to learn more about what is comforting for patients and families. Finally, it is evident that telehealth interactions will continue to be more widespread. As providers utilize new technology, more work is needed to determine best ways to engage patient and family in virtual environments.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Archstone Foundation. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Archstone Foundation.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Acknowledgements

We thank Adele Dobry and Jennifer Masunaga, Librarians at California State University Los Angeles, who assisted in designing the literature search strategy.

References

- 1.Fang J., Liu Y.T., Lee E.Y., Yadav K. Telehealth solutions for in-hospital communication with patients under isolation during COVID-19. West. J. Emerg. Med. 2020;21(4):801–806. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2020.5.48165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Janssen D.J.A., Ekstrom M., Currow D.C., Johnson M.J., Maddocks M., Simonds A.K., Tonia T., Marsaa K. COVID-19: guidance on palliative care from a European Respiratory Society international task force. Eur. Respir. J. 2020;56(3) doi: 10.1183/13993003.02583-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bowman B.A., Back A.L., Esch A.E., Marshall N. Crisis symptom management and patient communication protocols are important tools for all clinicians responding to COVID-19. J. Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60(2):e98–e100. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lau J., Knudsen J., Jackson H., Wallach A.B., Bouton M., Natsui S., Philippou C., Karim E., Silvestri D.M., Avalone L., Zaurova M., Schatz D., Sun V., Chokshi D.A. Staying connected in the COVID-19 pandemic: telehealth at the largest safety-net system in the United States. Health Aff. (Millwood) 2020;39(8):1437–1442. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aboumatar H. Three reasons to focus on patient and family engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic. Qual. Manage. Health Care. 2020;29(3):176–177. doi: 10.1097/QMH.0000000000000262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hart J.L., Turnbull A.E., Oppenheim I.M., Courtright K.R. Family-centered care during the COVID-19 era. J. Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60(2):e93–e97. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Etkind S.N., Bone A.E., Lovell N., Cripps R.L., Harding R., Higginson I.J., Sleeman K.E. The role and response of palliative care and hospice services in epidemics and pandemics: a rapid review to inform practice during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60(1):e31–e40. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Powell V.D., Silveira M.J. What should palliative care’s response be to the COVID-19 pandemic? J. Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60(1):e1–e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Back A.L., Fromme E.K., Meier D.E. Training clinicians with communication skills needed to match medical treatments to patient values. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019;67(S2):S435–S441. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leung D., Blastorah M., Nusdorfer L., Jeffs A., Jung J., Howell D., Fillion L., Rose L. Nursing patients with chronic critical illness and their families: a qualitative study. Nurs. Crit. Care. 2017;22(4):229–237. doi: 10.1111/nicc.12154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Banerjee S.C., Manna R., Coyle N., Shen M.J., Pehrson C., Zaider T., Hammonds S., Krueger C.A., Parker P.A., Bylund C.L. Oncology nurses’ communication challenges with patients and families: a qualitative study. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2016;16(1):193–201. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2015.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Institutes of Health COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel, Coronavirus Disease . 2019. (COVID-19) Treatment Guidelines, 2020.https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mirzoev T., Kane S. What is health systems responsiveness? Review of existing knowledge and proposed conceptual framework. BMJ Glob. Health. 2017;2(4) doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000486. e000486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.King A., Hoppe R.B. “Best practice” for patient-centered communication: a narrative review. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2013;5(3):385–393. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-13-00072.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas J., Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2008;8:1–10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ariadne Labs . 2020. COVID-19 Conversation Guide for Inpatient Care.https://covid19.ariadnelabs.org/serious-illness-care-program-covid-19-response-toolkit/#inpatient-resources [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ariadne Labs . 2020. COVID-19 Conversation Guide for Outpatient Care.https://covid19.ariadnelabs.org/serious-illness-care-program-covid-19-response-toolkit/#inpatient-resources [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ariadne Labs . 2020. COVID-19 Telehealth Communication Tips.https://covid19.ariadnelabs.org/serious-illness-care-program-covid-19-response-toolkit/#inpatient-resources [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ariadne Labs . 2020. COVID-19 Recommendation AId.https://covid19.ariadnelabs.org/serious-illness-care-program-covid-19-response-toolkit/#inpatient-resources [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ariadne Labs . 2020. COVID-19 Conversation Guide for Crisis Standards.https://covid19.ariadnelabs.org/serious-illness-care-program-covid-19-response-toolkit/#inpatient-resources [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ariadne Labs . 2020. COVID-19 Conversation Guide for Long-Term Care.https://covid19.ariadnelabs.org/serious-illness-care-program-covid-19-response-toolkit/#inpatient-resources [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Medical Association . 2020. A Physician’s Guide to COVID-19.https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/public-health/physicians-guide-covid-19 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prepare for your care . 2020. Advance Care Planning Script.https://www.capc.org/documents/813/ [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schwarze M.L., Zelenski A., Baggett N., Kalbfell E., Silverman E., Campbell T. 2020. Best case/worst case: ICU (COVID-19)http://www.hipxchange.org/BCWC_COVID-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.VitalTalk . 2020. Communication Skills for Bridging Inequity v2.1.https://www.vitaltalk.org/wp-content/uploads/COVID-Ready-Communication-Skills-for-Bridging-Inequity_-A-VitalTalk-Playbook-Supplement-1.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 26.VitalTalk . 2020. Goals of Care COVID Script.https://www.capc.org/covid-19/covid-19-goals-care-conversation-script/ [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baylor College Of Medicine/Geriatrics . 2020. Patient Priorities Care in an Age-Friendly Health System Telehealth Guidance for COVID19 Communications.https://patientprioritiescare.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Patient-Priorities-Care-in-an-Age-Friendly-Health-System-Telehealth-to-Address-COVID-19_PPCJF04172020.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oregon Health & Sciences University . 2020. Honoring Previously Determined Preferences for Medical Care.https://www.ohsu.edu/sites/default/files/2020-03/Honoring%20Previously%20Determined%20Preferences%20For%20Medical%20Care_Pocket%20Card.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 29.Respecting Choices . 2020. Medical Priorities for Treatment Options.https://respectingchoices.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Medical_Priorities_Treatment_Options_For_Use_in_Conversation_Only.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 30.Center to Advance Palliative Care . 2020. Palliative Communication Guide for Interpreters (Pocket Card Format)https://www.capc.org/documents/download/770/ [Google Scholar]

- 31.VitalTalk . 2020. Proactive Call to Patients With COVID at Home Script.https://www.capc.org/covid-19/proactive-call-patients-covid-19-about-receiving-care-home-conversation-script/ [Google Scholar]

- 32.Respecting Choices . 2020. Proactive Care Planning for COVID-19.https://respectingchoices.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Proactive_Care_Planning_Conversation_COVID-19.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 33.VitalTalk . 2020. Saying Goodbye to a Dying Familiy Member Over the Phone: Conversation Script.https://www.capc.org/covid-19/saying-goodbye-dying-family-member-over-phone-conversation-script/ [Google Scholar]

- 34.Respecting Choices . 2020. Introducing and Scheduling Proactive Care Planning.https://respectingchoices.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Scheduling_Proactive_Care_Planning_for_COVID-19.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lindenberger E., Helman S., Meier D. 2020. Communication Skills for COVID-19: Patient Dying Despite Critical Care Support.https://northmemorial.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/vent-withdrawal-shared-decision-making-conversation-script.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 36.VitalTalk . 2020. COVID Ready Communication Playbook.https://www.vitaltalk.org/guides/covid-19-communication-skills/ [Google Scholar]

- 37.Social Work Hospice & Palliative Care Network . 2020. Working With Families Facing Undesired Outcomes During the COVID19 Crisis.https://swhpn.memberclicks.net/assets/01%20Working%20With%20Families%20Undesired%20Outcomes%20COVID19.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 38.Association of Professional Chaplains . 2020. A Quick Guide to Providing Telechaplaincy Services.https://www.professionalchaplains.org/Files/resources/COVID-19/A%20Quick%20Guide%20to%20Providing%20Telehealth%20Services.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 39.VitalTalk . 2020. CALMER Goals of Care: A Discussion Guide.https://www.optimistic-care.org/docs/pdfs/Calmer_Goals_of_Care_Discussion_Guide_NEW.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spiritual Care Association . 2020. Chaplaincy in the Time of COVID-19.https://www.spiritualcareassociation.org/docs/resources/chaplaincy_time_covid_final_3_30_20.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 41.Academy of Communication in Healthcare . 2020. COVID-19 Communication Art Statements.http://www.achonline.org/COVID-19/ART [Google Scholar]

- 42.Academy of Communication in Healthcare . 2020. COVID-19 Communication: Quick Tips to Connect.http://www.achonline.org/COVID-19/Quick-Tips [Google Scholar]

- 43.SFVA Hospice and Palliative Care Service . 2020. Advance Care Planning Conversation Guide: For Use With Outpatients at High Risk of Developing COVID-19 Complications. prepareforyourcare.org. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kelemen A., Altilio T., Leff V. 2020. COVID Language Guide.https://swhpn.memberclicks.net/assets/COVIDLanguageGuideFinal.pdf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium . 2020. Communication Guide for Nurses and Others During COVID-19.https://www.aacnnursing.org/Portals/42/ELNEC/PDF/ELNEC-Communication-Guide-During-COVID-19.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 46.2020. Health Literacy Project/Harvard Health Publishing, About COVID-19.https://drive.google.com/file/d/1O_8ts5-92PpFkT-B07yNiqjYWHBfL55Q/view [Google Scholar]

- 47.P. International . 2020. Person-centered Guidelines for Preserving Family Presence in Challenging Times.https://planetree.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Published-Guidelines-on-Family-Presence-During-a-Pandemic-Final-8.13.20v5.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hospice & Palliative Nurses Association . 2020. Communication With Patients With COVID19.https://advancingexpertcare.org/HPNAweb/Education/COVID19_PrimaryPalliativeNursing.aspx [Google Scholar]

- 49.Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care . 2020. COVID-19 And Patient- and Family-centered Care.https://www.ipfcc.org/bestpractices/covid-19/IPFCC_PFCC_and_COVID.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 50.University of California San Diego Health . 2020. Spiritual Care - Brief COVID-19 Guidance for Healthcare Workers.https://anselmhouse.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Spiritual-Care-Guidance-for-Health-Care-Workers_Kestenbaum.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 51.Temel . 2020. Telehealth Visit Outline (REACH-PC Study)https://www.pcori.org/research-results/2017/comparing-ways-provide-palliative-care-patients-advanced-lung-cancer [Google Scholar]

- 52.Adams C. Goals of care in a pandemic: our experience and recommendations. J. Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60(1):E15–E17. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen E. Palliative care and ethical considerations in the COVID-19 ICU. Critical Care Alert. 2020;28(6):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Akgün K.M., Shamas T.L., Feder S.L., Schulman-Green D. Communication strategies to mitigate fear and suffering among COVID-19 patients isolated in the ICU and their families. Heart Lung. 2020;49(4):344–345. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2020.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Back A., Tulsky J.A., Arnold R.M. Communication skills in the age of COVID-19. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020;172(11):759–760. doi: 10.7326/M20-1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Barello S., Palamenghi L., Graffigna G. Empathic communication as a “Risky strength” for health during the COVID-19 pandemic: the case of frontline Italian healthcare workers. Patient Educ. Couns. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2020.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bergman D., Bethell C., Gombojav N., Hassink S., Stange K.C. Physical distancing with social connectedness. Ann. Fam. Med. 2020;18(3):272–277. doi: 10.1370/afm.2538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bowman B.A., Back A.L., Esch A.E., Marshall N. Crisis symptom management and patient communication protocols are important tools for all clinicians responding to COVID-19. J. Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60(2):e98–e100. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brucato A. Taylor & Francis Ltd; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: 2020. Voices From the Frontline: Notes From a COVID-19 Emergency Unit in Milan, Italy…Dr. Antonio Brucato; pp. 76–78. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Carico R.R., Jr., Sheppard J., Thomas C.B. Community pharmacists and communication in the time of COVID-19: applying the health belief model. Res. Social Adm. Pharm. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cordero D.M., Davis D.L. Communication for equity in the service of patient experience: health justice and the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Patient Exp. 2020;7(3):279–281. doi: 10.1177/2374373520933110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dhavale P., Koparkar A., Fernandes P. Palliative care interventions from a social work perspective and the challenges faced by patients and caregivers during COVID-19. Indian J. Palliat. Care. 2020;26:58–62. doi: 10.4103/IJPC.IJPC_149_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Diamond L.C., Jacobs E.A., Karliner L. Providing equitable care to patients with limited dominant language proficiency amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Patient Educ. Couns. 2020;103(8):1451–1452. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2020.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fan P.E.M., Aloweni F., Lim S.H., Ang S.Y., Perera K., Quek A.H., Quek H.K.S., Ayre T.C. Needs and concerns of patients in isolation care units - learnings from COVID-19: a reflection. World J. Clin. Cases. 2020;8(10):1763–1766. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i10.1763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Feder S., Akgün K.M., Schulman-Green D. Palliative care strategies offer guidance to clinicians and comfort for COVID-19 patient and families. Heart Lung. 2020;49(3):227–228. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2020.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Finset A., Bosworth H., Butow P., Gulbrandsen P., Hulsman R.L., Pieterse A.H., Street R., Tschoetschel R., van Weert J. Effective health communication - a key factor in fighting the COVID-19 pandemic. Patient Educ. Couns. 2020;103(5):873–876. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2020.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gaur S., Pandya N., Dumyati G., Nace D.A., Pandya K., Jump R.L.P. A structured tool for communication and care planning in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020;21(7):943–947. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.05.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gharzai L.A., Resnicow K., An L.C., Jagsi R. Perspectives on oncology-specific language during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: a qualitative study. JAMA Oncol. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.2980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gibbon L.M., GrayBuck K.E., Buck L.I., Huang K.-N., Penumarthy N.L., Wu S., Curtis J.R. Development and implementation of a clinician-facing prognostic communication tool for patients with COVID-19 and critical illness. J. Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60(2):e1–e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hart J.L., Turnbull A.E., Oppenheim I.M., Courtright K.R. Family-centered care during the COVID-19 era. J. Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60(2):e93–e97. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hauser J.M. Walls. Hastings Cent. Rep. 2020;50(3):12–13. doi: 10.1002/hast.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hector P. Proactive communication and collaboration with families during COVID-19. Caring Ages. 2020;21(5):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hill A. Patient-practitioner communication in diabetes and diabetes-related foot complications. Diabetic Foot J. 2020;23(2):56–61. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Holstead R.G., Robinson A.G. Discussing serious news remotely: navigating difficult conversations during a pandemic. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2020;16(7):363–368. doi: 10.1200/OP.20.00269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Houchens N., Tipirneni R. Compassionate communication amid the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Hosp. Med. 2020;15(7):437–439. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Julka-Anderson N. How COVID-19 is testing and evolving our communication skills. J. Med. Imaging Radiat. Sci. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jmir.2020.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lewin W. Joule Inc.; Ottowa, Ontario: 2020. Making Treatment Recommendations During the COVID-19 Pandemic; p. E521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lewis A. Discussing goals of care in a pandemic: precedent for an unprecedented situation. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care. 2020;37(10):873–874. doi: 10.1177/1049909120941881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]