Abstract

Objective

The aim of the study was to conduct a systematic review of the literature to investigate the time of onset and duration of symptoms of loss of smell and taste in patients diagnosed with COVID-19.

Methods

Two independent authors performed a systematic review of the Medline/PubMed, SCOPUS, COCHRANE, Lilacs and Web of Science electronic databases. The time of onset and duration of symptoms were considered primary outcomes. The sex and age of individuals, the geographical location of the study, the prevalence of symptoms, other associated symptoms, associated comorbidities, and the impact on quality of life and eating habits were considered secondary outcomes.

Results

Our search generated 17 articles. Many of the studies reported that the onset of anosmia and ageusia occurred 4 to 5 days after the manifestation of other symptoms of the infection and that these symptoms started to disappear after one week, with more significant improvements in the first two weeks.

Conclusion

The present study concludes that the onset of symptoms of loss of smell and taste, associated with COVID-19, occurs 4 to 5 days after other symptoms, and that these symptoms last from 7 to 14 days. Findings, however, varied and there is therefore a need for further studies to clarify the occurrence of these symptoms. This would help to provide early diagnosis and reduce contagion by the virus.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Anosmia, Ageusia, Smell, Taste

1. Introduction

COVID-19 (Coronavirus 2019 disease), which is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), was first registered in China in December 2019, being associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome [1]. The spread of the virus was very rapid, reaching pandemic status in early 2020 [2]. By the end of August 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) had registered 24,021,218 confirmed cases and 821,462 confirmed deaths [3]. Brazil was the first country in Latin America to diagnose a patient with COVID-19, on February 25, 2020, in the city of São Paulo. According to the WHO, by the end of August 2020, Brazil had registered 3,669,995 confirmed cases and 116,580 deaths [3].

The most prevalent symptoms in the first patients included fever, cough, myalgia and shortness of breath [4]. However, as the pandemic spread to more countries and the numbers of infected individuals increased, other signs and symptoms came to be viewed as clinical manifestations of the disease [5]. One unusual symptom in particular began to appear in an increasing number of patients: dysfunction of smell and taste - loss of sensitivity to taste and smell [6]. In South Korea, China and Italy, a large percentage of infected patients developed anosmia or hyposnomy [4]. In Italy, about 33.9% of patients reported changes in smell and taste and 11% reported both disorders [6]. In South Korea, where tests were performed on a large scale, 30% of patients had loss of smell as the main sign in mild cases of infection [4]. More than two-thirds of those infected in Germany developed anosmia [4]. In Brazil, a study carried out with 253 recovered patients, showed that 212 had experienced sudden-onset anosmia and 196 had developed loss of smell accompanied by nonspecific inflammatory symptoms [6]. Sudden changes in smell thus came to be seen as initial signs of COVID-19 [7] and, anosmia, in the absence of other symptoms, such as rhinorrhea or nasal congestion, may be an indicator of SARS-CoV-2 infection [[8], [9], [10], [11], [12]].

In view of this, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) added the loss of taste and smell to the list of signs and symptoms that may arise from the second to the fourteenth day after exposure to the virus. During this time, there are generally no specific clinical manifestations, because it is the viral incubation period [1]. The Brazilian Academy of Rhinology and the Brazilian Association of Otorhinolaryngology and Cervical-Facial Surgery duly issued a warning that cases of anosmia, with or without concomitant ageusia, may indicate the presence of infection by COVID-19 [6]. However, despite being a very prevalent symptom in patients with COVID-19, the onset time and duration of these symptoms has not been well established. Understanding of this issue would contribute greatly to early diagnosis, thereby enabling prevention of further contagions and possible complications. We thus performed a systematic review of the literature to investigate the time of onset and duration of symptoms of loss of smell and taste in patients diagnosed with COVID-19.

2. Materials & methods

The present systematic review was carried out in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [13]. Our review was conducted using a protocol submitted to the International Prospective Registry for Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) and published under registration number: CRD42020186114.

2.1. Research strategy

The literature search was carried out in May 2020 using the Medline/PubMed (Online System for Research and Analysis of Medical Literature), SCOPUS, COCHRANE, Lilacs (Latin American and Caribbean literature in health sciences) and Web of Science electronic databases. Variations of the following descriptors were used: COVID-19; SARS-COV-2; smell; taste; olfaction disorders; anosmia; taste disorders; dysgeusia.

The bibliographic search in the electronic databases was carried out by two independent reviewers (SANTOS REA and DA SILVA, MG), using a pre-established protocol. A third reviewer (BARBOSA, DAM) was consulted when necessary and acted as a mediator in decisions regarding inclusion or exclusion criteria, on occasions when there was no agreement between the reviewers. Data extraction was performed according to the eligibility criteria established for the study.

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The present review included human studies that assessed the symptoms of loss of smell and/or taste in patients diagnosed with COVID-19, regardless of laboratory confirmation and other symptoms related to the disease. Studies were excluded if they did not explain in detail the outcomes investigated in the present review or if they did not provide detailed explanation of their methodology. Case-reports, letters to the editor, literature reviews, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and in vitro and animal studies were also excluded. There were no restrictions regarding language or year of publication.

2.3. Evaluation of articles

The assessment of the risk of bias in the studies was performed independently by two reviewers using the Modified Health Care Research and Quality Agency (AHRQ) instrument [14]. The studies were evaluated using a list of twenty-six items, divided into nine evaluation criteria: study question, study population, subject comparability, exposure or intervention, measured results, statistical analysis, results, discussion, and funding or sponsorship [14,15].

The primary outcomes for reviewing the literature on loss of smell and taste in patients diagnosed with COVID-19 were the time of onset and duration of symptoms. Secondary outcomes included the sex and age of individuals, the geographical location of the study, prevalence of symptoms, other associated symptoms, associated co-morbidities, and the impact on quality of life and eating habits.

The level of agreement between the reviewers and the quality of the studies (risk of bias) were analyzed using the kappa coefficient on the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences - SPSS version 20 for Windows (IBM SPSS Software, Armonk, NY, USA).

3. Results

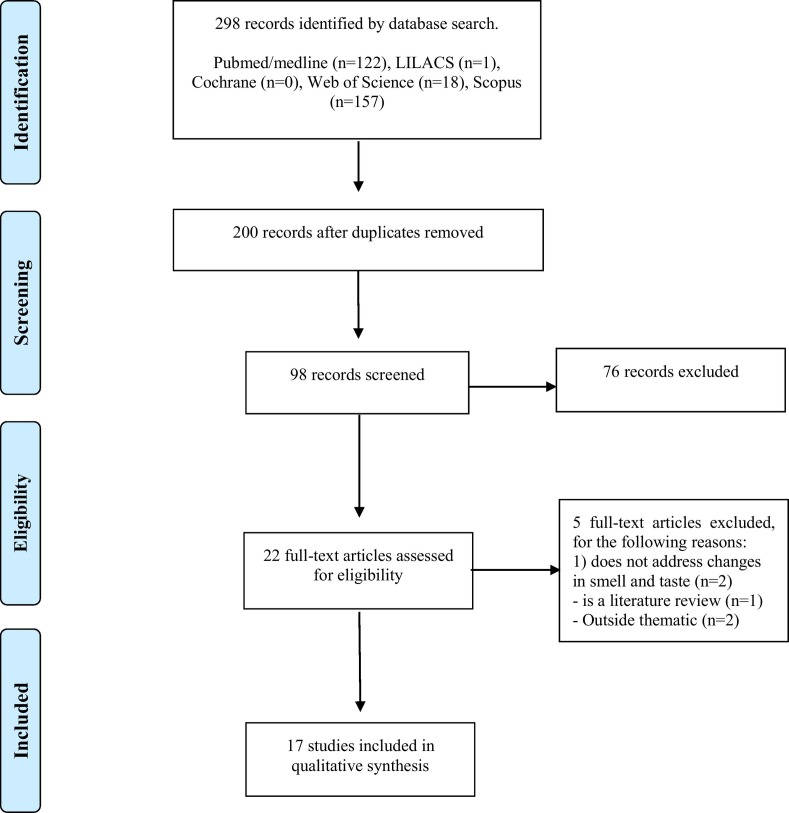

The initial database search identified a total of 298 articles, 122 in Medline/PubMed, 157 in Scopus, one in LILACS, 18 in Web of Science and none in Cochrane. Removal of duplicate articles reduced the total to 200, which title and abstract screening reduced further to 22 articles. These 22 studies underwent full-text analysis, resulting in the exclusion of 5 studies and generating a final total of 17 articles included for analysis, as shown in the flowchart presented in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

Selection of articles.

3.1. Quality assessment of articles

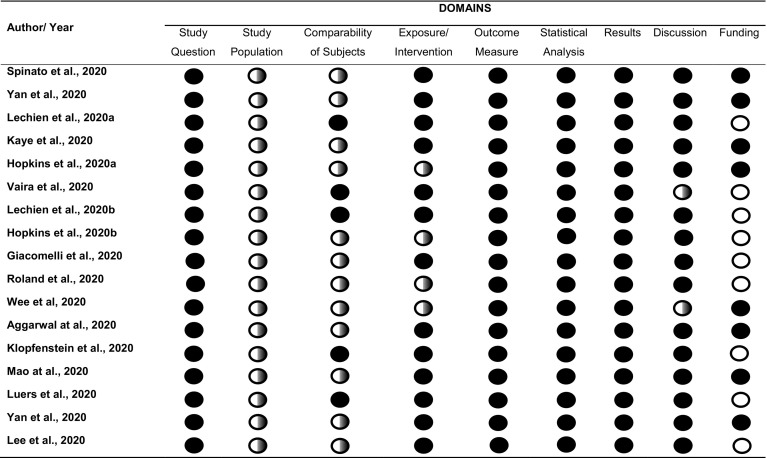

Table 1 shows the evaluation of the articles according to the points highlighted by West [14]. Evaluation of quality criteria revealed methodological shortcomings in some articles, including: failure to justify the sample size (all articles included in the review); failure to detail inclusion and exclusion criteria [8,9,12,[16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24]]; analysis of individuals who were not tested for COVID-19 [[18], [19], [20], [21]]; failure to address the limitations of the study [15,21]; and failure to cite sources of financing, even if these did not exist [8,10,15,19,20,[24], [25], [26], [27]]. The level of agreement between reviewers regarding analysis of data extraction and risk of bias was almost perfect (Kappa: 0.8824) [28].

Table 1.

Characterization of studies according to evaluation criteria highlighted by West et al. (2002).

=Yes;

=Yes;  =Partial;

=Partial;  =No information. Kappa: 0.8824.

=No information. Kappa: 0.8824.

The results of studies of the time of onset and duration of symptoms of loss of smell and taste in patients diagnosed with COVID-19, as well as the sex and age of individuals, the geographical location of the study, the prevalence of symptoms, associated symptoms, associated comorbidities, and the impact on quality of life and eating habits, are summarized in Table 2 .

Table 2.

Characteristics of studies included.

| Author (year) | Sample characterization | Methodological design | Investigated outcomes | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hopkins et al., 2020a | 382 female and male adults were included. 74.6% of the sample was composed of women. The median age range was 40 to 49 years. 46.8% of those evaluated were younger than 40 years old. The study was carried out in London, UK. | - Online survey of patients diagnosed during the COVID-19 pandemic, who sought advice by e-mail on smell and taste disorders and were followed up for one week. | 1.Duration of symptoms 2.Prevalence of symptoms |

1. In one week, 80.1% of individuals reported lower severity scores on follow-up, 17.6% remained unchanged and 1.9% were worse. There seems to have been a significant improvement in the first two weeks, but thereafter the recovery rate seems to taper off. 2. 86.4% of patients reported complete anosmia and another 11.5% reported severe loss of smell. |

| Hopkins et al., 2020b | 2428 female and male adults were included. 73% of the sample was composed of women. 64% of respondents were under 40 years old. The median age was 30 to 39 years. The study was carried out in London, UK | - A simple questionnaire regarding the onset of anosmia and associated symptoms was designed and sent to patients sought advice by email on symptoms of anosmia (cohort). The questionnaire was also widely applied throughout the population that did not contact the counseling service (cross-sectional study) | 1.Time of onset of symptoms 2.Duration of symptoms 3.Prevalence of symptoms 4.Associated symptoms |

1. 13% of individuals reported anosmia before other symptoms appeared, 38.4% at the same time as other symptoms, and 48.6% after other symptoms. 2. Symptoms lasted between 1 and 4 weeks. There seemed to be a significant improvement in the first 2 weeks. 3. 74.4% of individuals reported complete loss of smell, another 17.3% reported very severe loss. 90% reported that their sense of taste was reduced, but 61% of the entire group reported that they could still differentiate between sweet, salty, sour and bitter flavors. 4. Of the cohort, 17% of individuals reported no other symptoms associated with COVID-19. In patients who reported other symptoms, 51% reported cough or fever. |

| Spinato et al., 2020 | 202 female and male adults were included. The average age of the individuals was 56 years. The study was carried out in Italy. | - Patients were contacted 5 to 6 days after the swab for diagnosis of COVID-19 - A telephone interview was conducted, using the Respiratory Tract Infection Questionnaire. - Patients had performed the Sino-nasal Test 22 (SNOT-22). SNOT-22 classifies the severity of symptoms of changes in smell and taste. |

1.Time of onset of symptoms 2.Sex and age of individuals 3.Prevalence of symptoms 4.Associated symptoms |

1. The change in sense of smell or taste occurred before other symptoms in 24 patients (11.9%); at the same time as other symptoms in 46 patients (22.8%); and after other symptoms in 54 patients (26.7%); 6 patients (3.0%) reported that altered sense of smell or taste had been the only symptom. 2. Altered sense of smell or taste was found in 105 women (72.4%) and in 97 men (55.7%). No comparison was made between age and changes in smell and taste. 3. Changes in sense of smell or taste were reported by 130 patients (64.4%). 4. Of the 130 patients who reported altered sense of smell or taste, 45 (34.6%) also reported nasal obstruction. Other common symptoms were: fatigue (68.3%), dry or productive cough (60.4%) and fever (55.5%). |

| Yan et al., 2020ª | 262 adults were included, 161 women, 98 men, and 1 person of indeterminate sex. The age profile of the individuals was as follows: 18–29 years: 36 individuals; 30–39 years: 78 individuals; 40–49 years: 56 individuals; 50–59 years: 45 individuals; 60–69 years: 26 individuals; 70–79 years: 15 individuals; > 80+ years: 5 individuals. The study was carried out in the United States, in the State of California. | - Adult patients, diagnosed or not with COVID-19, reported their symptoms, focusing on smell and taste, by way of an internet platform (Qualtrics, Provo, UT). The sample was divided into “COVID positive” and “COVID negative” patients. A comparison was made between these two groups. | 1.Prevalence of symptoms 2.Associated symptoms |

1. Among patients testing positive for COVID-19, 68% reported loss of sense of smell and 71% loss of sense of taste. 4. Other self-reported symptoms associated with testing positive for COVID-19 were: fatigue (81%), fever (70%), myalgia or arthralgia (63%), diarrhea (48%) and nausea (27%). |

| Lechien et al., 2020a | A total of 1420 individuals (over 15 years of age), male and female, were included, 458 men and 962 women. The average age of the individuals was 39.17 years. This was a multicentre European study carried out with data from France (Paris, Marseille), Italy (Milan, Verona, Naples, Genoa, Florence, Forli), Spain (Seville, Santiago de Compostela, San Sebastian), Belgium (Mons, Brussels, Charleroi, Saint-Ghislain) and Switzerland (Geneva). | - Patients and health professionals diagnosed with COVID 19 were identified through the database of hospital laboratories, and underwent an interview, using a standardized questionnaire containing questions about clinical or epidemiological outcomes, - The questionnaire was applied in the patient's room or by telephone, to infected home patients or health professionals. |

1.Duration of symptoms 2.Sex and age of individuals 3.Prevalence of symptoms 4.Associated symptoms 5.Associated comorbidities |

1. The average duration of symptoms in patients with mild to moderate COVID-19 was 11.5 ± 5.7 days. Loss of smell persisted at least 7 days after the disease in 37.5% of cured patients. 2. The symptom of loss of smell was more prevalent in women. Young patients had greater loss of smell. 3. 70.2% of the individuals had loss of smell and 54.2% of the individuals had loss of taste. 4. The most common symptoms were headache (70.3%), nasal obstruction (67.8%), cough (63.2%), asthenia (63.3%), myalgia (62.5%), rhinorrhea (60.1%) and sore throat (52.9%). Fever was reported by 45.4%. 5. Allergic rhinitis (13.4%), hypertension (9.2%), reflux (6.9%) and asthma (6.5%) were the most prevalent comorbidities. |

| Kaye et al., 2020 | 237 adults were included, 108 men and 129 women. The average age of the individuals was 39.6 years. The study was conducted using data from the United States, Mexico, Italy, the United Kingdom and other countries. | - Input data from the “COVID-19 Anosmia Report to Clinicians” was analyzed. This tool enables health professionals to submit a confidential report of cases of anosmia and dysgeusia related to COVID 19. | 1.Time of onset of symptoms 2.Duration of symptoms |

1. The time taken for anosmia to improve was 7.2 ± 3.2 days. 2. Anosmia was observed in 175 (73%) of individuals before diagnosis of COVID 19, and 65 (27%) of individuals after diagnosis of COVID 19. |

| Vaira et al., 2020 | 72 adults were studied, 27 men and 45 women. The average age of the individuals was 49.2 years. The study was carried out in Italy. | - Medical records were evaluated and some general information was recorded: age, sex, previous medical history and positive swab. - The olfactory function was evaluated using the CCCRC orthonasal olfaction test. |

1.Time of onset of symptoms 2.Duration of symptoms 3.Sex and age of individuals 4.Prevalence of symptoms 5.Associated symptoms |

1. Ageusia and anosmia were the first symptoms of COVID-19, usually occurring within the first 5 days of the beginning of the clinical period. In 13 patients (18.1%), impaired taste and smell were the first clinical manifestations of the disease. 2. At the time of the assessment, the majority of these patients (66%) reported complete recovery of chemosensitive functions, which occurred within 5 days in 19 cases, and more than 5 days in the remaining 16 cases. 18 patients (34%) reported lasting impairment of taste and smell. 3. No differences were found in relation to sex and smell and/or taste disorders. Olfactory and gustatory scores were worse in patients over 50 years of age. 4. Fifty-three patients (73.6%) reported experiencing chemosensory disorders in the period during which they were infected with COVID-19. Taste disorders alone were reported in nine cases (12.5%), while 14 individuals (14.4%) reported olfactory dysfunctions alone. Thirty patients (41.7%) reported that they experienced disorders of both senses. 5. Other symptoms reported were: fever (95.8%), cough (83.3%), nasal obstruction (15.3%), rhinorrhea (18.1%), sore throat (51.4%), headache (41.6%), asthenia (66.7%), abdominal symptoms (11.1%), and pneumonia (30.6%). |

| Lechien et al., 2020b | 417 adults were studied, 154 men and 263 women. The average age was 36.9 years. The study was carried out in 12 European hospitals, in Italy, Spain, Belgium and France. | - Patients diagnosed with COVID-19 were recruited from 12 European hospitals. - The following epidemiological and clinical outcomes were studied: age, sex, ethnicity, comorbidities and general and otorhinolaryngological symptoms. - Patients completed olfactory and taste questionnaires based on the olfactory and taste component of the National Survey on Health and Nutrition Examination and the short version of the Questionnaire on Negative Declarations of Olfactory Disorders (sQOD-NS). |

1.Time of onset of symptoms 2.Sex and age of individuals 3.Prevalence of symptoms 4.Associated symptoms 5.Associated comorbidities |

1. The average time between the beginning of the infection and the evaluation was 9.2 ± 6.2 days. Olfactory dysfunction appeared before other symptoms in 11.8% of cases. 2. Women were proportionally more affected by dysfunctions in smell and taste compared to men. No comparison was made between age and changes in smell and taste. 3. 85.6% of individuals reported dysfunctions of smell and 88.0% of individuals reported dysfunctions in taste. 4. The most prevalent general symptoms were: cough, myalgia, and loss of appetite. Facial pain and nasal obstruction were the otorhinolaryngological symptoms most commonly related to the disease. 5. The most prevalent comorbidities were: allergic rhinitis, asthma, hypertension, and hypothyroidism. There was no significant association between comorbidities and the development of olfactory or gustatory disorders. |

| Giacomelli et al., 2020 | 59 adults were studied, 40 men and 19 women. The average age was 60 years. The study was carried out in Italy | - All patients hospitalized at L. Hospital Sacco, Milan, with positive SARS-CoV-2, completed a simple questionnaire, including questions about the presence or absence of ATD, its type and time of onset in relation to hospitalization. | 1. Time of onset of symptoms 2. Sex and age of individuals 3.Prevalence of symptoms 4.Associated symptoms |

1. Twelve patients (20.3%) had symptoms before hospitalization, while eight (13.5%) had symptoms during hospitalization. Changes in taste were more frequent (91%) before hospitalization, while, after hospitalization, taste and olfactory changes appeared with equal frequency. 2. Women reported smell and taste disorders more frequently than men. Patients with at least one of these senses affected were younger than patients without the disorders. 3. 20 patients (33.9%) reported either impaired taste or an olfactory disorder and 11 (18.6%) reported both disorders. 4. Fever 43 (72.8%), cough 22 (37.3%), dyspnea 15 (25.4%), sore throat 1 (1.7%), arthralgia 3 (5.1%), runny nose 1 (1.7%), headache 2 (3.4%), asthenia 1 (1.7%), abdominal symptoms 5 (8.5%). |

| Roland et al., 2020 | 302 adults were studied, 88 men and 214 women. The mean age of the individuals was 40 years for the positive COVID-19 group, and 38 years for the negative COVID-19 group. The study was carried out in the United States, in the State of California. | - An anonymous survey was released by various media (Facebook, Twitter, Reddit and Nextdoor), looking for volunteer participants who had been tested or quarantined for the symptoms of COVID-19. Self-reported anonymous responses were collected - Groups of health professionals who care for patients with COVID - 19 were also targeted. Participants recruited included those who identified themselves as over 18 and had a history of previous COVID - 19 tests or a history of quarantine for symptoms of COVID - 19. |

1.Prevalence of symptoms 2.Associated symptoms |

1. 66% of individuals with COVID 19 had a change in smell or taste. 2. Other symptoms reported were: body pain 112 (77%), fever 106 (73%), sore throat 59 (41%), shortness of breath 50 (34%), headache 93 (64%), cough 79 (54%), nasal obstruction 68 (47%), nausea or diarrhea 64 (44%), rhinorrhea 52 (36%) |

| Wee et al., 2020 | 860 adult males and females were included in the study. No detailed data on sex and age of the individuals were provided. The study was carried out in Singapore. | - During a two-week period, a questionnaire was administered to patients diagnosed with COVID 19, including questions about respiratory symptoms, self-reported OTD, and epidemiological and travel risk factors in screening for ED to stratify the risk of hospitalization. | 1.Prevalence of symptoms 2.Associated symptoms |

1. Of the patients testing positive for COVID-19, approximately one fifth (22.7%) had impaired smell and taste. 2. Fever was the most common concomitant symptom (60.0%), followed by cough (28.5%) and rhinorrhea (28.5%). |

| Aggarwal et al., 2020 | 16 adults were included, 12 men and 4 women. The average age was 65.5 years. The study was conducted in the Midwest region of the United States. | - The medical records of patients hospitalized for COVID-19 in the health system of a medium-sized city in the Midwest region of the USA were analyzed. - Data on symptoms were analyzed on the initial presentation of the patient or on admission. - Data were collected on medical history and previous comorbidities, and vital signs on admission - All laboratory values on the day of hospitalization and during hospitalization were collected. |

1.Prevalence of symptoms 2.Associated symptoms 3.Associated comorbidities |

1. 3 patients (19%) reported loss of smell and taste. 2. Fever (94%), cough (88%) and dyspnea (81%), chest pain (6.3%), headache (25%) and diarrhea (6.3%). 3. 6 patients (38%) had chronic kidney disease; 1 (6%) end-stage kidney disease; 2 (13%) had a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD); 9 patients (56.3%) had a history of hypertension; 3 (19%) had a history of coronary artery disease; 3 (19%) with a history of congestive heart failure and 2 (13%) with a history of stroke. |

| Klopfenstein et al., 2020 | 114 adult female and male patients were included. Of these, only 54 were studied, as the objective of the study was to evaluate only those who had anosmia. Thus, a total of 36 women and 18 men with impaired sense of smell were evaluated. The average age of the individuals was 47 years. The study was carried out in France. | - The medical records of all adult patients with COVID-19 between March 1 and March 17, 2020, who were examined in the consultation for infectious diseases or hospitalized in the hospital, and who reported anosmia were analyzed. - Data were collected on: age, sex, comorbidities, characteristics of anosmia (date of appearance since the onset of symptoms, duration of anosmia), other symptoms, physical signs and outcome. |

1.Time of onset of symptoms 2.Duration of symptoms 3.Prevalence of symptoms 4.Associated symptoms 5.Associated comorbidities |

1. Anosmia started 4.4 ± 1.9 days after infection started. 2. The average duration of anosmia was 8.9 days, with ≥ 7 days for 55% of individuals and ≥14 days for 20% of individuals. 3. 47% of individuals diagnosed with COVID 19 had anosmia. Of these, 85% also had dysgeusia. 4. Anosmia was associated with dysgeusia 85%; rhinorrhea (57%); nasal obstruction (30%); fatigue (93%); cough (87%); headache (82%); fever (74%); myalgia (74%); arthralgia (72%) and diarrhea (52%). 5. The most frequent comorbidities were: asthma (13%), high blood pressure (13%) and cardiovascular diseases (11%). |

| Mao et al., 2020 | 214 adults were studied, 127 women and 87 men. The average age was 52.7 years. The study was conducted in Wuhan, China. | - Data were collected from January 16, 2020 to February 19, 2020 at three special service centers designated for COVID-19 in China. - Clinical data were extracted from electronic medical records and data on all neurological symptoms and verified by two trained neurologists. |

1.Prevalence of symptoms 2.Associated symptoms 3.Associated comorbidities |

1. 12 patients had a change in taste and 11 patients had a change in smell. 19 patients had manifestations in the peripheral nervous system. In these patients, the most common symptoms were impaired taste (5.6%) and impaired smell (5.1%). 2. Fever (61.7%); cough (50%) and anorexia (31.8%). 3. The most frequent comorbidities were: hypertension (23.8%); diabetes (14%); heart or cerebrovascular diseases (7%) and malignancies (6.1%). |

| Luers et al., 2020 | 72 adults were studied, 31 women and 41 men. The average age of the individuals was 38 years. The study was conducted in Germany. | - Medical records of outpatients, diagnosed with COVID 19, identified retrospectively by the records of the University Hospital of Cologne, Cologne, Germany, were analyzed. | 1.Time of onset of symptoms 2.Prevalence of symptoms 3.Associated symptoms |

1. Both symptoms occurred on average on the fourth day after the first symptoms. In 9 patients (13%), reduced smell and loss of meaning occurred together on the first day that they noticed any symptoms. 2. 53 individuals (74%) had reduced smell and 50 individuals (69%) had reduced taste. 3. Other symptoms included headache (78%), cough (75%) and muscle pain (71%) and diarrhea (31%). - Nasal symptoms included nasal congestion (54%); sneezing (50%); rhinorrhea (53%); nasal itching (11%). |

| Yan et al., 2020b | 260 adults were included, 161 women, 98 men, and one person of unidentified sex. The age profile of the individuals was: 18–29 years: 36 individuals; 30–39 years: 78 individuals; 40–49 years: 56 individuals; 50–59 years: 45 individuals; 60–69 years: 26 individuals; 70–79 years: 15 individuals; > 80+ years: 5 individuals. The study conducted in the United States, in the city of San Diego. | - A retrospective review was conducted of all patients who in a San Diego Hospital system with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 infection. - Data on olfactory and gustatory function and the clinical course of the disease were examined. |

1.Duration of symptoms 2.Prevalence of symptoms 3.Associated symptoms |

1. Regarding the improvement in the loss of smell, 29 out of 40 (72.5%) reported improvement at the time of the survey (18% in <1 week, 37.5% in 1 to 2 weeks, 18% in 2 to 4 weeks). Most of the patients testing positive for COVID-19 showed improvement in the senses of smell and taste that correlated temporally with clinical resolution of the disease. 2. In positive COVID-19 patients, 68% and 71% had impaired smell and taste, respectively. 3. Fatigue (81%), fever (70%), myalgia or arthralgia (63%), diarrhea (48%) and nausea (27%). |

| Lee et al., 2020 | 3191 adults were studied, 2030 women and 1161 men. The average age of the individuals was 44 years. The study was carried out in Daegu, Korea. | - Doctors prospectively interviewed patients diagnosed with COVID-19 who were awaiting hospitalization or isolation concerning the presence of anosmia or ageusia. - Additional telephone calls were made after admission to assess the duration of symptoms among those who reported that anosmia or ageusia persisting until hospitalization or isolation. |

1.Duration of symptoms 2.Sex and age of individuals 3.Prevalence of symptoms |

1. Most patients with anosmia or ageusia recovered within 3 weeks; with the average recovery time was 7 days for both symptoms. 2. Impaired sense of smell or taste was found in 336 women (68.9%) and in 152 men (31.1%), and the average age of individuals with such changes was 36.5 years. Younger individuals, particularly those aged between 20 and 39 years, showed a tendency to experience longer duration of anosmia 3. Of 3191 patients, 232 (7.27%) had anosmia and 143 (4.48%) had ageusia. |

3.2. Characterization of the studies

3.2.1. Sex and age of individuals

All 17 articles provided data on the age and sex of individuals, although only five articles found an association between sex and alterations in the sense of taste or smell [10,12,15,24,25], with women presenting a higher prevalence of such alterations. Only four articles found an association between age and olfactory and gustatory symptoms, [10,15,24,25], although these results were inconsistent. Two studies found that younger people presented a higher prevalence of these symptoms [10,25]; one study found that adults with a mean age of 36.5 were more affected [24]; and one study showed that symptoms were more prevalent in individuals over 50 years of age [15].

3.2.2. Geographical location of studies

The studies covered by the present review provided data for countries on three continents, three articles were from Asia [21,23,24], five from North America [9,16,17,20,22], and 10 from Europe [[8], [9], [10],12,15,18,19,[25], [26], [27]]. All articles reported alterations in the sense of smell and taste in patients with COVID-19, although, in Asian countries, the prevalence of olfactory and gustatory dysfunction reported was lower compared to North America and Europe. In China, the prevalence of such symptoms was 5.6%, in Korea, 15%, and, in Singapore, 22%. In North America and Europe, the prevalence varied from 18.6% to 90%.

3.3. Time of onset of symptoms

The articles reviewed reported conflicting results regarding the time of onset of symptoms of loss of smell and/or taste in patients diagnosed with COVID-19. Many studies, however, reported that the onset of anosmia and ageusia occurred 4 to 5 days after the appearance of other symptoms of the infection [15,26,27]. Analysis of the prevalence of the appearance of changes in smell and/or taste before, simultaneously with or after other symptoms as reported in these articles found that the prevalence of such symptoms emerging prior to other symptoms varied between 13% [19] and 73% in patients (before diagnosis) [9]; the prevalence of such symptoms emerging at the same time as other symptoms, varied from 13.5% [8] to 38.4% [19]; and that of such symptoms appearing after other symptoms from 27% [9] to 48.6% [19].

3.4. Duration of symptoms

The duration of symptoms of loss of smell and/or taste in patients diagnosed with COVID-19 was addressed in eight articles [9,10,15,[17], [18], [19],24,26]. The findings were inconsistent but, generally speaking, the symptoms begin to disappear after one week [9,15,24], and, in the first two weeks, significant improvement occurred [[17], [18], [19]]. In addition, two studies found that 34% [15] and 37.5% [10] of the subjects continued to show symptoms for at least 7 days, even after recovery from the disease.

3.5. Prevalence of symptoms

Only one of the studies reviewed did not assess the prevalence of symptoms of loss of smell and/or taste in patients diagnosed with COVID-19. This study looked only at individuals who had already presented with anosmia [9]. Six combined the prevalence for symptoms of loss of smell and taste, reporting a minimum prevalence of 19% [22] and a maximum of 73.6% [15]. Regarding olfactory disorders alone, six studies found a prevalence of over 68% [10,12,16,17,25,27] and two found a prevalence of less than 7.27% [23,24]. In relation to taste disorders, six studies reported a prevalence greater 54.2% [10,16,17,19,25,27] and two registered a prevalence of below 5.1% [23,24].

3.6. Associated symptoms

Many studies also showed that changes in smell and/or taste may occur concomitantly with other symptoms. The most commonly mentioned were: fever [8,12,16,17,[19], [20], [21], [22], [23],[25], [26], [27]], cough [8,10,12,15,[19], [20], [21], [22], [23],[25], [26], [27]], headache [8,10,15,20,22,26,27], and fatigue [12,16,17,26]. Some studies also reported gastrointestinal symptoms [8,[15], [16], [17],20,22,26,27]., Six studies found that smell and taste disorders occurred together with nasal obstruction [10,12,15,20,25,26].

3.7. Associated comorbidities

Five of the studies covered by our review investigated co-morbidities present in patients diagnosed with COVID-19 [10,22,23,25,26]. The most prevalent co-morbidities were systemic arterial hypertension [10,22,23,25,26], rhinitis [10,25], asthma [10,25,26], and cardiovascular disease [22,23,26].

4. Discussion

The spread of COVID-19 around the world has been accompanied by the appearance of symptoms that differ from a common flu [29,30]. Changes in smell and taste have been strongly associated with a positive diagnosis of infection by the new coronavirus [31]. This association is confirmed by the prevalence of more than 50% for anosmia and/or agneusia in patients with COVID-19 [10,12,15,16,27]. However, the time of onset time and duration of these symptoms has yet to be clearly established. Adequate quantification of loss of smell and/or taste, and identification of the temporal relationship between COVID-19 contagion and olfactory and/or gustatory dysfunctions would provide great assistance in arriving at an early diagnosis and thereby avoiding further contagion and possible complications [32]. The present systematic review thus aimed to establish the time of onset and duration of symptoms of loss of smell and taste in patients diagnosed with COVID-19.

The tool used to assess risk of bias (AHRQ) [14] found that the articles reviewed were effectively addressed the proposed study question. Some, however, were marred by methodological shortcomings, especially with regard to the “study population”, since they did not calculate the sample size. However, this probably occurred due to the lack of information on the prevalence of this novel disease. We also observed that the studies analyzed employed a variety of different methods and presented their findings in different ways, making it impossible to carry out a meta-analysis.

All articles included in this review investigated both female and male individuals, but only five articles found any association between sex and changes in taste and smell [10,12,15,24,25]. Although men have a less favorable prognosis for COVID-19 [33], the prevalence in women of changes in smell and taste was higher in the five studies reviewed [10,12,15,24,25]. The average age range was 38 to 65 years, with a predominance of adults and elderly people affected by the infection. This is the age group that appears to be most affected by COVID-19 [[34], [35], [36]]. One study cited working outside the home during the pandemic as an important risk factor for the transmission of the disease among adults, as this occasions more contact with people and, consequently, greater exposure to the virus [37].

The prevalence of smell and taste dysfunction appeared to be lower in Asia, compared to North America and Europe. It is thus possible to identify a change in the profile of the main symptoms as the disease passes through different countries. This may be related to the different strains of the virus that have been circulating since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Around 93 mutations have been observed throughout the SARS-CoV-2 genome in different geographic regions [38]. A meta-analysis carried out with cases of COVID-19 in China, the country that presented the first cases of the disease, showed that the main symptoms were fever, cough, fatigue, sputum and dyspnea [39]. When the disease reached European countries, a change in symptoms occurred and olfactory and gustatory changes began to appear as clinical signs. Such signs may prove a great aid to diagnosis of COVID-19, since they are predominant symptoms in people affected by the virus [40]. Most patients with Sars-CoV-2 infection are considered asymptomatic and do not require hospitalization [10]. Symptomatic patients have symptoms such as fever, dry cough, shortness of breath, gastrointestinal symptoms and also symptoms that mainly affect smell and taste, in which there is a significant reduction in these senses. Such symptoms have been reported mainly in countries in Europe and America [25].

In the studies evaluated the prevalence of changes in both taste and smell in patients with COVID-19 ranged from 19% to 73%. Furthermore, a survey of 204 patients found a prevalence of these symptoms of 56.9% among adults [41]. Another study found that 19% of patients experienced loss of both olfactory and gustatory functions concomitantly [42]. Even with these divergences, the presence of the two associated symptoms in individuals with suspected COVID-19 is of great importance for the diagnosis of this infection, It can, in fact, be seen from the articles included in this review that, in patients with a positive or negative diagnosis, these changes in smell and taste were more likely to be present in patients with a positive diagnosis of the disease. This association has also been observed in other studies of adult individuals with a positive diagnosis of COVID-19 [42,43].

Regarding the time of onset of smell and/or taste changes in patients with COVID-19, it was difficult to establish a relationship between the findings of the studies reviewed, because of the extent to which they differ from one another. Some of the authors indicate that these changes may precede the development of other common symptoms of the disease, such as fever, shortness of breath, dry cough and fatigue [8,10,12]. It is important to note that, in the context of a pandemic, tracking symptoms of loss of smell and/or taste in non-hospitalized patients may prove to be a useful clinical screening tool [15], helping to direct patients towards testing services and thus helping to commence care early on and hence reduce transmission of the disease.

The results of the studies also diverged regarding the duration of symptoms of loss of smell and/or taste. This ranged from five days to four weeks, with an average of one to two weeks for recovery. In addition, a case-control study with 119 individuals found that the average duration of smell and/or taste disorders was 7.5 ± 3.2 days, and that 40% of individuals recovered completely 7.4 ± 2.3 days after the onset of symptoms, without having to seek hospital care [31]. More detailed investigation of the duration of these symptoms is, however, still required. Two of the studies reviewed reported persistence of symptoms, even after recovery from the disease [10,15]. Furthermore, the impact of this persistence of olfactory and gustatory loss after the end of COVD-19 infection is still unclear. We therefore stress the importance of conducting research that analyzes the time and persistence of symptoms associated with olfactory and gustatory disorders in patients with COVID-19, since the results found in the literature are scarce and present divergent findings.

The scientific literature considers a number of hypotheses regarding the pathogenic mechanisms associated with changes in smell and taste in patients with COVID-19 and some of these takes into account the duration of sensory dysfunctions. One such hypothesis is that these disorders occur due to direct damage caused by the virus to olfactory and gustatory receptors [44]. It is believed that changes in smell can be caused by damage caused by the virus to the olfactory bulb [44], or to the olfactory nerve [24]. In the case of taste disorders, studies have hypothesized that this may be associated with damage to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) [15], which was recently identified as the SARS-CoV-2 cell receptor [45]. ACE2 receptors are present in the oral cavity [46] and have been associated with the modulation of taste perception [46]. Furthermore, Cazzolla et al. [47] have observed a correlation between the occurrence of smell and taste disorders and IL-6 levels. Recovery of olfactory and gustatory functions is associated with reduced levels of IL-6 and one probable explanation for this finding concerns the role that IL-6 plays at the peripheral level in cell receptors infected by the virus. At the central level, IL-6 also plays a role in the intermediate stages on the gustatory and olfactory pathways, especially in the thalamus [47]. Further studies, however, are needed to shed light on the physiological mechanisms associated with these symptoms, both in cases where changes in smell and/or taste are transient and in those where they are permanent.

It was also observed that changes in smell and/or taste may occur concomitantly with other symptoms. The other symptoms most commonly mentioned by the studies under review were: fever, cough, headache, fatigue and gastrointestinal symptoms. These are classic symptoms of the mildest form of COVID-19. The literature indicates that the most severe symptoms of the virus include respiratory distress, fever, cough and fatigue [39,48]. Other, less prevalent symptoms that may appear are diarrhea, nausea and vomiting [49,50]. Of the thirteen studies, only six reported individuals presenting changes in smell and taste who also experienced nasal obstruction [10,12,15,20,25,26]. This corroborates case reports showing that anosmia and ageusia can be found in patients testing positive for COVID-19, even when other respiratory symptoms are absent [29,50]. Vaira et al. [44] thus claim that sudden changes in smell and taste, usually not accompanied by symptoms of nasal obstruction or rhinitis, are strongly suggestive of ongoing COVID-19 infection and should be treated with care.

The most prevalent comorbidities in individuals with COVID-19 experiencing loss of smell and/or taste were: systemic arterial hypertension [10,16,[24], [25], [26]], rhinitis [10,25], asthma [10,25,26] and cardiovascular diseases [16,24,26]. Furthermore, Chen et al. compared the characteristics of patients diagnosed with COVID-19 who died with those who recovered, and observed that those who died were more likely to have a comorbidity, such as hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular disease or chronic lung disease [51]. No study mentioned the impact of smell and/or taste dysfunction on the quality of life and eating habits of patients with COVID-19.

Taste and smell play an important role in the selection of diet, metabolism, and quality of life. Anosmic individuals may present changes in eating habits, such as increased seasoning and use of sugar [52]. In addition, increased consumption of salt, sugar, and fat in patients with changes in smell or taste may complicate issues relating to hypertension, diabetes and cardiovascular diseases [53]. A longitudinal cohort study with subjects self-reporting impaired sense of taste and smell showed these individuals to have greater increases in systolic blood pressure and mean arterial pressure compared to individuals without impaired taste and smell [54]. In view of the high prevalence of co-morbidities such as arterial hypertension and cardiovascular diseases associated with dysfunctions of smell and/or taste in patients diagnosed with COVID-19, studies are therefore needed to investigate the influence of changes in smell and/or taste on quality of life and eating habits in patients diagnosed with COVID-19, especially those with co-morbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, obesity, cardiovascular disease, and others.

4.1. Study limitations

The main limitation of the present study was the heterogeneity of the selected articles, which employed a variety of different methodologies. Some used virtual questionnaires, while others used the medical records of hospitalized patients or telephone interviews. These factors may have influenced the findings regarding the exact duration of olfactory and gustatory symptoms, since most of the studies were based on patient reports and conducted with no prior explanation as to what these symptoms are or how they may change over time. This may lead to a lack of accurate information regarding the reported symptoms.

5. Conclusion

The present study concluded that the onset of symptoms of loss of smell and taste, associated with COVID-19, was 4 to 5 days after other symptoms, and that these symptoms lasted from 7 to 14 days. Findings, however, varied and there is therefore a need for further studies to clarify the occurrence of these symptoms. This would help to provide early diagnosis and reduce contagion by the virus. Furthermore, loss of the sense of smell and taste, in the absence of symptoms indicative of nasal obstruction, to provide a strong indication for a diagnosis of COVID-19. We should also note the need for nutritional monitoring of patients with olfactory and gustatory changes, to avoid excessive consumption of salt and sugar. Finally, it is recommended that a molecular diagnostic test for SARS-CoV-2 be performed in all individuals with sudden, severe loss of smell and taste, and no other symptoms.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

KNFP conceptualized and designed the study, drafted, and critically revised the manuscript. REAS, MGS, MCBMS, and DAMB performed literature reviews, critically reviewed, interpreted data/literature reviews, drafted, and revised the manuscript. ALVG, LCMG and RSA conceptualized and designed the study, critically reviewed the manuscript draft and revisions.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to NPlast (the Phenotypic Nutrition and Plasticity Studies Unit) for technical support. This study received financial assistance from the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES - Brazil), the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq - Brazil), the Pro-Rectory for Research and Innovation (Propesqi - UFPE), and the Foundation for the Support of Science and Technology of Pernambuco (FACEPE - Brazil). The study sponsors were not involved in the study design; data collection, analysis, and interpretation; the writing of the manuscript; nor in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

References

- 1.Tong J.Y., Wong A., Zhu D., Fastenberg J.H., Tham T. The prevalence of olfactory and gustatory dysfunction in COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Otolaryngol - Head Neck Surg (United States) 2020 doi: 10.1177/0194599820926473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ornell F., Schuch J.B., Sordi A.O., Kessler F.H.P. ‘“Pandemic fear”’ and COVID-19: mental health burden and strategies. Brazilian J Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2020-0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Who WHO coronavirus disease (COVID-19) dashboard [internet] 2020. https://covid19.who.int/

- 4.Jotz G.P., Voegels R.L., Bento R.F. Otorhinolaryngologists and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2020 doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1709724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vargas-Gandica J., Winter D., Schnippe R., Rodriguez-Morales A.G., Mondragon J., Escalera-Antezana J.P., et al. Ageusia and anosmia, a common sign of COVID-19? A case series from four countries. J Neurovirol. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s13365-020-00875-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kosugi E.M., Lavinsky J., Romano F.R., Fornazieri M.A., Luz-Matsumoto G.R., Lessa M.M., et al. Incomplete and late recovery of sudden olfactory dysfunction in COVID-19. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bjorl.2020.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kang Y.J., Cho J.H., Lee M.H., Kim Y.J., Park C.S. The diagnostic value of detecting sudden smell loss among asymptomatic COVID-19 patients in early stage: the possible early sign of COVID-19. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2020.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giacomelli A., Pezzati L., Conti F., Bernacchia D., Siano M., Oreni L., et al. Self-reported olfactory and taste disorders in SARS-CoV-2 patients: a cross-sectional study. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaye R., CWD Chang, Kazahaya K., Brereton J., Denneny J.C. COVID-19 anosmia reporting tool: initial findings. Otolaryngol - Head Neck Surg (United States) 2020 doi: 10.1177/0194599820922992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lechien J.R., Chiesa-Estomba C.M., Place S., Van Laethem Y., Cabaraux P., Mat Q., et al. Clinical and epidemiological characteristics of 1,420 European patients with mild-to-moderate coronavirus disease 2019. J Intern Med. 2020 doi: 10.1111/joim.13089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parma V., Ohla K., Veldhuizen M.G., Niv M.Y., Kelly C.E., Bakke A.J., et al. More than smell – COVID-19 is associated with severe impairment of smell, taste, and chemesthesis. Chem Senses. 2020 doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjaa041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spinato G., Fabbris C., Polesel J., Cazzador D., Borsetto D., Hopkins C., et al. Alterations in smell or taste in mildly symptomatic outpatients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.West S., King V., Carey T.S., Lohr K.N., McKoy N., Sutton S.F., et al. Systems to rate the strength of scientific evidence. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ) 2002;47:1–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vaira L.A., Deiana G., Fois A.G., Pirina P., Madeddu G., De Vito A., et al. Objective evaluation of anosmia and ageusia in COVID-19 patients: single-center experience on 72 cases. Head Neck. 2020 doi: 10.1002/hed.26204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yan C.H., Faraji F., Prajapati D.P., Boone C.E., DeConde A.S. Association of chemosensory dysfunction and COVID-19 in patients presenting with influenza-like symptoms. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/alr.22579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yan C.H., Faraji F., Prajapati D.P., Ostrander B.T., DeConde A.S. Self-reported olfactory loss associates with outpatient clinical course in COVID-19. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/alr.22592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hopkins C., Surda P., Whitehead E., Kumar B.N. Early recovery following new onset anosmia during the COVID-19 pandemic - an observational cohort study. J Otolaryngol - Head Neck Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1186/s40463-020-00423-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hopkins C., Surda P., Nirmal Kumar B. Presentation of new onset anosmia during the covid-19 pandemic. Rhinology. 2020 doi: 10.4193/Rhin20.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roland L.T., Gurrola J.G., Loftus P.A., Cheung S.W., Chang J.L. Smell and taste symptom-based predictive model for COVID-19 diagnosis. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/alr.22602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wee L.E., Chan Y.F.Z., Teo N.W.Y., Cherng B.P.Z., Thien S.Y., Wong H.M., et al. The role of self-reported olfactory and gustatory dysfunction as a screening criterion for suspected COVID-19. Eur Arch Oto-Rhino-Laryngology. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00405-020-05999-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aggarwal S., Garcia-Telles N., Aggarwal G., Lavie C., Lippi G., Henry B.M. Clinical features, laboratory characteristics, and outcomes of patients hospitalized with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): early report from the United States. Diagnosis. 2020 doi: 10.1515/dx-2020-0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mao L., Jin H., Wang M., Hu Y., Chen S., He Q., et al. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee Y., Min P., Lee S., Kim S.W. Prevalence and duration of acute loss of smell or taste in COVID-19 patients. J Korean Med Sci. 2020 doi: 10.3346/JKMS.2020.35.E174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lechien J.R., Chiesa-Estomba C.M., De Siati D.R., Horoi M., Le Bon S.D., Rodriguez A., et al. Olfactory and gustatory dysfunctions as a clinical presentation of mild-to-moderate forms of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a multicenter European study. Eur Arch Oto-Rhino-Laryngology. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00405-020-05965-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klopfenstein T., Kadiane-Oussou N.J., Toko L., Royer P.Y., Lepiller Q., Gendrin V., et al. Features of anosmia in COVID-19. Med Mal Infect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2020.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luers J.C., Rokohl A.C., Loreck N., Wawer Matos P.A., Augustin M., Dewald F., et al. Olfactory and gustatory dysfunction in coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) Clin Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Landis J.R., Koch G.G. An application of hierarchical kappa-type statistics in the assessment of majority agreement among multiple observers. Biometrics. 1977 doi: 10.2307/2529786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Villalba N.L., Maouche Y., Ortiz M.B.A., Sosa Z.C., Chahbazian J.B., Syrovatkova A., et al. Anosmia and dysgeusia in the absence of other respiratory diseases: should COVID-19 infection be considered? Eur J Case Reports Intern Med. 2020 doi: 10.12890/2020_001641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Russell B., Moss C., Rigg A., Hopkins C., Papa S., Van Hemelrijck M. Anosmia and ageusia are emerging as symptoms in patients with COVID-19: what does the current evidence say? Ecancermedicalscience. 2020 doi: 10.3332/ecancer.2020.ed98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beltrán-Corbellini Á., Chico-García J.L., Martínez-Poles J., Rodríguez-Jorge F., Natera-Villalba E., Gómez-Corral J., et al. Acute-onset smell and taste disorders in the context of Covid-19: a pilot multicenter PCR-based case-control study. Eur J Neurol. 2020 doi: 10.1111/ene.14273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mullol J., Alobid I., Mariño-Sánchez F., Izquierdo-Domínguez A., Marin C., Klimek L., et al. The loss of smell and taste in the COVID-19 outbreak: a tale of many countries. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s11882-020-00961-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cai H. Sex difference and smoking predisposition in patients with COVID-19. Lancet Respir Med. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30117-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Palaiodimos L., Kokkinidis D.G., Li W., Karamanis D., Ognibene J., Arora S., et al. Severe obesity is associated with higher in-hospital mortality in a cohort of patients with COVID-19 in the Bronx, New York. Metabolism. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2020.154262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Munayco C., Chowell G., Tariq A., Undurraga E.A., Mizumoto K. MedRxiv Prepr; 2020. Risk of death by age and gender from CoVID-19 in Peru, March-May, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu P., Zhu J., Zhang Z., Han Y. A familial cluster of infection associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating possible person-to-person transmission during the incubation period. J Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Güner R., Hasanoğlu İ., Aktaş F. Covid-19: prevention and control measures in community. Turkish J Med Sci. 2020 doi: 10.3906/sag-2004-146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Phan T. Genetic diversity and evolution of SARS-CoV-2. Infect Genet Evol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2020.104260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li L. quan, Huang T., Wang Y. qing, Wang Z. ping, Liang Y., Huang T. bi, et al. COVID-19 patients’ clinical characteristics, discharge rate, and fatality rate of meta-analysis. J Med Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gautier J.F., Ravussin Y. A new symptom of COVID-19: loss of taste and smell. Obesity. 2020 doi: 10.1002/oby.22809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mercante G., Mercante G., Ferreli F., Ferreli F., De Virgilio A., De Virgilio A., et al. Prevalence of taste and smell dysfunction in coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Otolaryngol - Head Neck Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2020.1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Izquierdo-Dominguez A., Rojas-Lechuga M., Mullol J., Alobid I. Olfactory dysfunction in the COVID-19 outbreak. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2020 doi: 10.18176/jiaci.0567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sayin İ., Yaşar K.K., Yazici Z.M. Taste and smell impairment in COVID-19: an AAO-HNS anosmia reporting tool-based comparative study. Otolaryngol - Head Neck Surg (United States) 2020 doi: 10.1177/0194599820931820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vaira L.A., Salzano G., Fois A.G., Piombino P., De Riu G. Potential pathogenesis of ageusia and anosmia in COVID-19 patients. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/alr.22593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhou P., Lou Yang X., Wang X.G., Hu B., Zhang L., Zhang W., et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Suliburska J., Duda G., Pupek-Musialik D. The influence of hypotensive drugs on the taste sensitivity in patients with primary hypertension. Acta Pol Pharm - Drug Res. 2012;69(1):121–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cazzolla A.P., Lovero R., Lo Muzio L., Testa N.F., Schirinzi A., Palmieri G., et al. Taste and smell disorders in COVID-19 patients: role of interleukin-6. Am Chem Soc Public Heal Emerg Collect. 2020 doi: 10.1021/2Facschemneuro.0c00447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fu L., Wang B., Yuan T., Chen X., Ao Y., Fitzpatrick T., et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X., Qu J., Gong F., Han Y., et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang Q., Shan K.S., Abdollahi S., Nace T. Anosmia and ageusia as the only indicators of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Cureus. 2020 doi: 10.7759/cureus.7918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen T., Wu D., Chen H., Yan W., Yang D., Chen G., et al. Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: retrospective study. BMJ. 2020 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ferris A.M., Schlitzer J.L., Schierberl M.J., Catalanotto F.A., Gent J., Peterson M.G., et al. Anosmia and nutritional status. Nutr Res. 1985 doi: 10.1016/S0271-5317(85)80030-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kershaw J.C., Mattes R.D. Nutrition and taste and smell dysfunction. World J Otorhinolaryngol - Head Neck Surg. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.wjorl.2018.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu Y.H., Huang Z., Vaidya A., Li J., Curhan G.C., Wu S., et al. A longitudinal study of altered taste and smell perception and change in blood pressure. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2018.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]