Abstract

The diverse clinical manifestations of COVID-19 is emerging as a hallmark of the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection. While the initial target of SARS-CoV-2 is the respiratory tract, it is becoming increasingly clear that there is a complex interaction between the virus and the immune system ranging from mild to controlling responses to exuberant and dysfunctional multi-tissue directed autoimmune responses. The immune system plays a dual role in COVID-19, being implicated in both the anti-viral response and in the acute progression of the disease, with a dysregulated response represented by the marked cytokine release syndrome, macrophage activation, and systemic hyperinflammation. It has been speculated that these immunological changes may induce the loss of tolerance and/or trigger chronic inflammation. In particular, molecular mimicry, bystander activation and epitope spreading are well-established proposed mechanisms to explain this correlation with the likely contribution of HLA alleles. We performed a systematic literature review to evaluate the COVID-19-related autoimmune/rheumatic disorders reported between January and September 2020. In particular, we investigated the cases of incident hematological autoimmune manifestations, connective tissue diseases, antiphospholipid syndrome/antibodies, vasculitis, Kawasaki-like syndromes, acute arthritis, autoimmune-like skin lesions, and neurologic autoimmune conditions such as Guillain–Barré syndrome. We screened 6263 articles and report herein the findings of 382 select reports which allow us to conclude that there are 2 faces of the immune response against SARS-CoV-2, that include a benign virus controlling immune response and a many faceted range of dysregulated multi-tissue and organ directed autoimmune responses that provides a major challenge in the management of this viral disease. The number of cases for each disease varied significantly while there were no reported cases of adult onset Still disease, systemic sclerosis, or inflammatory myositis.

Keywords: COVID-19, Autoimmune manifestations, systematic review

1. Introduction

The outbreak of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) that first emerged in Wuhan (Hubei Province, China) in December 2019 rapidly became a pandemic, with more than 32.7 million cases reported as of September 27, 2020 [1]. The COVID-19 clinical presentation ranges from asymptomatic individuals or mild flu-like symptoms, to a very severe condition with interstitial pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [2]. In the first phases of the disease, the viral infection triggers a strong immune response which is fundamental for viral clearance, with a cascade of events involving both innate and adaptive immunity that potentially can become harmful when they become dysregulated [3,4]. The immunological alterations associated with different stages of COVID-19 have been described since the earliest reports, and include an elevated number of macrophages, hyperactivation of T cells and the release of increased plasma levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g. IL-1β, IL-6, TNFα), leading to what is termed as “a cytokine storm” and cytokine release syndrome that appears to be correlated with the severity of disease outcome [5] possibly modifiable with immunomodulating drugs [6]. Several studies enlighten the immunological and clinical similarities between COVID-19 disease and hyperinflammatory diseases, leading to the hypothesis that the SARS-CoV-2 infection might trigger an autoimmune response in genetically predisposed subjects [7,8].

During the past decades, viral infections have been proposed as environmental factors triggering autoimmunity in genetically prone individuals. Respiratory viruses, particularly parainfluenza and coronaviruses, have been associated with the onset of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [9] while growing evidence describes the occurrence of well-known autoimmune conditions in COVID-19, including autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA), immune thrombocytopenia (ITP), thrombotic events associated with anti-phospholipid antibodies, connective tissue diseases, Kawasaki-like disease, ANCA-associated vasculitis, arthritis, autoimmune-like skin manifestations and neurologic demyelinating syndromes. The enormous number of publications reported in the literature over the past months has made it virtually impossible to follow the literature and derive a meaningful consensus opinion. These thoughts highlight the need for a timely systematic literature review to not only illustrate the data on autoimmune rheumatic conditions described in patients with COVID-19, but also to serve as a summary of what we understand about the potential mechanism(s) involved.

2. Study search strategy and selection

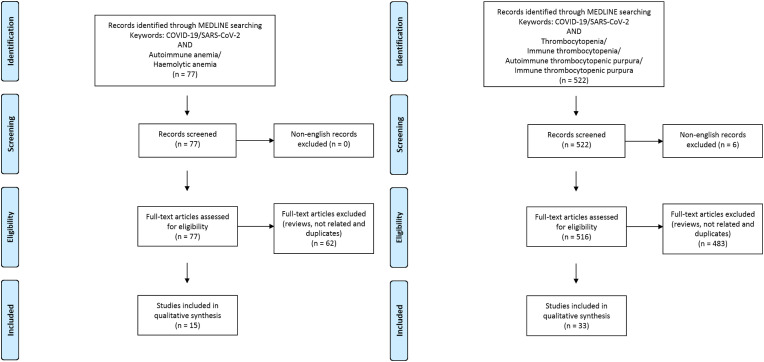

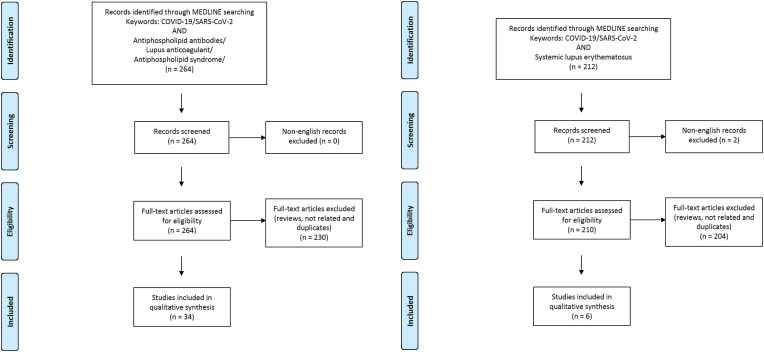

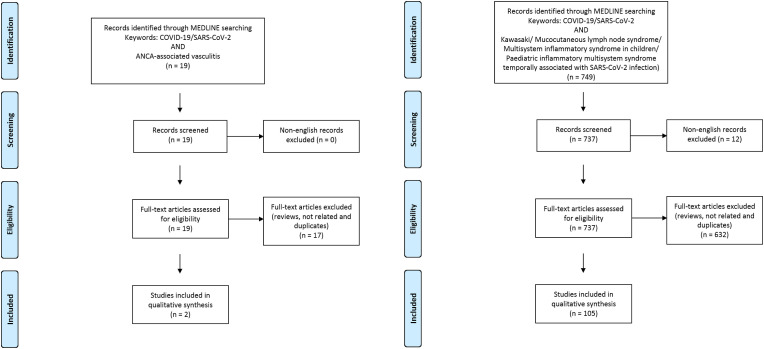

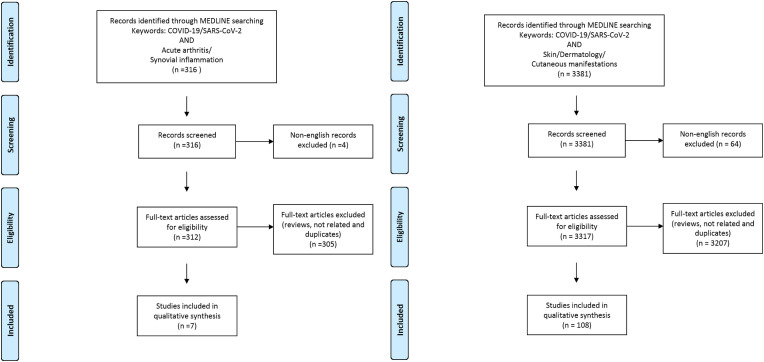

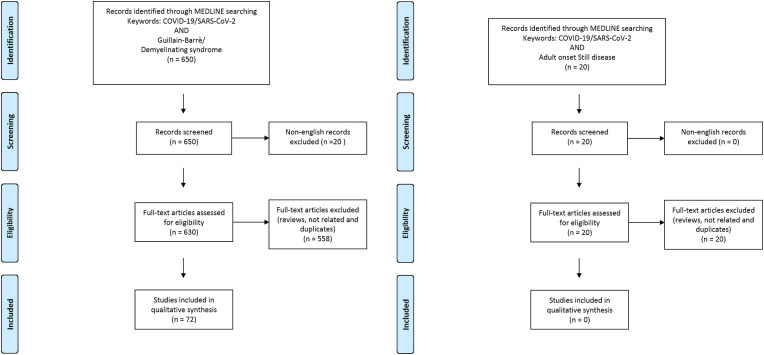

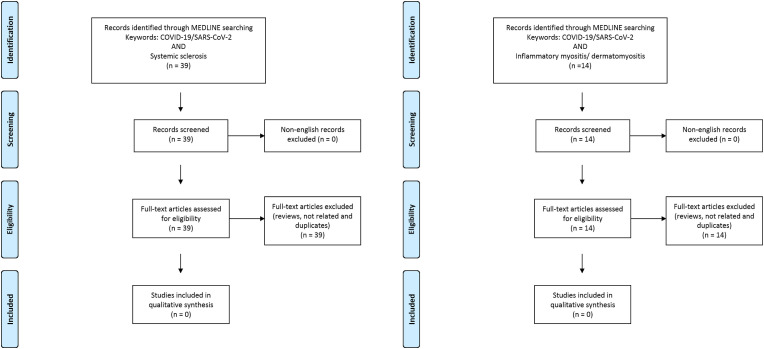

The Medline database was accessed from PubMed and systematically searched for articles published in English between January 1 and September 30, 2020. We followed the search strategy and article selection process illustrated in the flowcharts in Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6 according to the recommendations of the PRISMA statement [10]. The search strings in title/abstract and the keywords used for each association are detailed in the respective flowchart. Only peer-reviewed articles in English accepted for publication that included case reports and case series were included in this search. Two reviewers (LN and FM) searched all relevant articles independently and summarized them. They discussed any area of uncertainty, screened the full text reports and decided whether these met the inclusion criteria while resolving any disagreement through discussions. Neither of the authors were blind to the journal titles or to the study authors or institutions.

Fig. 1.

Flowcharts show the study selection process according to preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA).

Fig. 2.

Flowcharts show the study selection process according to preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA).

Fig. 3.

Flowcharts show the study selection process according to preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA).

Fig. 4.

Flowcharts show the study selection process according to preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA).

Fig. 5.

Flowcharts show the study selection process according to preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA).

Fig. 6.

Flowcharts show the study selection process according to preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA).

3. Results

3.1. Hematologic manifestations

3.1.1. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA)

AIHA is frequently linked to autoimmune diseases, drugs, malignancy and, in rare cases, infections [11]. A few cases of AIHA have been shown to be associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection (Table 1 ) including both warm and cold AIHA. In some cases, patients were affected by pre-existent immune thrombocytopenia, suggesting a susceptible background for hematological dysregulations [[12], [13], [14]]. Molecular mimicry has been proposed to trigger AIHA, with antibodies elicited against viral proteins cross reacting with self-antigens. A putative self-antigen involved could be Ankyrin-1, an erythrocyte membrane protein showing structural similarities with the viral spike protein [15]. In two cases AIHA and idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) presented both during COVID-19 and Evans syndrome were diagnosed [16,17]. In some cases, patients had an indolent B lymphoid malignancy either already known or discovered because of the hemolytic episode. The delay between COVID-19 and hemolytic manifestations ranged from 4 to 13 days [18].

Table 1.

Hemolytic anemia cases associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

| Manifestation | Patients number | Sex | Age (years) | Treatment | Outcome | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AIHA | 1 warm | F | 46 | IVIg, glucocorticoids and transfusion | Recovered | [12] |

| AIHA | 7 (4 warm, 3 cold) |

4 M 3 F |

median 62 (range 61–89) | Glucocorticoids (5 cases), + rituximab (2 cases), transfusion (2 cases) | Partly recovered | [18] |

| AIHA | 1 cold | F | 46 | None | Death | [13] |

| Evans syndrome | 1 | M | 39 | IVIg | Recovered | [16] |

| AIHA | 1 warm | M | 17 | Glucocorticoids, transfusion | Recovered | [14] |

| AIHA | 1 cold | M | 62 | Transfusion | Recovered | [100] |

| AIHA | 2 cold | F M |

43 63 |

Transfusion None |

Recovered Recovered |

[101] |

| AIHA | 1 warm | M | 56 | IVIg, glucocorticoids and transfusion | Recovered | [102] |

| AIHA | 1 cold | F | 51 | Glucocorticoids | Recovered | [103] |

| Evans syndrome | 1 | F | 23 | Transfusion, glucocorticoids, IVIg, rituximab | Recovered | [17] |

| AIHA | 1 cold | M | 48 | Transfusion | Death | [104] |

| AIHA | 1 warm | F | 13 | Glucocorticoids | Recovered | [105] |

| AIHA | 1 cold | F | 24 | None | Recovered | [106] |

| AIHA | 2 cold | M M |

70 67 |

None None |

Recovered Death |

[107] |

| AIHA | 1 mixed | F | 14 | Glucocorticoids, transfusions, rituximab | Recovered | [25] |

Abbreviations. AIHA: autoimmune hemolytic anemia. F: female. M: male. IVIg: intravenous immunoglobulin.

3.1.2. Immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP)

Thrombocytopenia may occur in nearly 30% of cases of coronaviruses infections [19] and a mild reduced platelet count is a common finding in COVID-19. Possible causes include the reduced production due to bone marrow progenitor destruction by direct viral infection or cytokine storm, impaired biogenesis in the lung, platelet consumption due to microthrombi formation or platelet destruction [19]. The latter mechanism could be induced by viral infections through cross-reactivity between viral and platelet proteins, or through platelet coating with antibodies or immune complexes generated during the infection that are recognized by the reticuloendothelial cells and destroyed [20]. ITP has been reported in HKU1 coronavirus (a related but distinct coronavirus) infection [21]. It is therefore not surprising that SARS-CoV-2 also appears to trigger ITP, either during the course of the infection or in some cases weeks after the resolution and appears to be independent of the severity of the disease.

The reported cases of ITP associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection are listed in Table 2 with a limited number of cases occurring at pediatric ages [[22], [23], [24], [25]]. Of note, an association between low platelet counts (for any cause) and mortality has been found in these cases [26,27]. Therefore, when thrombocytopenia is present in the context of SARS-CoV-2 infection, it is important to consider ITP, as the prompt management may significantly improve the prognosis. Flares of previously diagnosed ITP have been described, as in the case of a woman with a previous diagnosis of ITP, receiving immunosuppressive therapy with prednisone (10 mg/daily) and cyclosporine (50 mg/daily) experiencing a severe exacerbation with marked decrease of platelet count during COVID-19 [28]. Another case concerned a 37-year-old woman who was treated with mycophenolate mofetil for ITP secondary to systemic lupus erythematosus and had a flare during mild COVID-19 [29]. ITP exacerbation also occurred in a 34-year-old woman during the second trimester of pregnancy [30] and a de novo disease was diagnosed in another pregnant woman [31]. Among patients affected by ITP, death was determined to be secondary to intracerebral bleeding [32], or respiratory deterioration [33]. One additional case of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) was diagnosed 9 days after a SARS-CoV-2 infection confirmed by serum tests [34].

Table 2.

Immune thrombocytopenia cases associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

| Manifestation | Patients number | Sex | Age (years) | Treatment | Outcome | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITP | 1 | F | 65 | IVIg, platelet transfusion, glucocorticoids, thrombopoietin | Recovered | [108] |

| ITP | 1 | F | 32 | Platelet transfusion, glucocorticoids | Improvement | [109] |

| ITP | 1 | M | 39 | IVIg, glucocorticoids | Recovered | [110] |

| ITP | 3 | 2 M 1 F |

59 66 67 |

Glucocorticoids (2 cases), + IVIg (1 case), platelet transfusion | 2 Improvements 1Death |

[32] |

| ITP | 1 | M | 41 | IVIg | Recovered | [111] |

| ITP | 3 | 1 M 2 F |

50 49 96 |

IVIg | 2 Recovered 1 Death |

[33] |

| ITP | 1 | F | 12 | IVIg, glucocorticoids | Recovered | [22] |

| ITP | 1 | F | 10 | IVIg | Recovered | [23] |

| ITP | 1 | M | 84 | IVIg, glucocorticoids | Recovered | [112] |

| ITP flare | 1 | F | 72 | IVIg, platelet transfusion, glucocorticoids | Recovered | [28] |

| ITP flare | 1 | F | 37 | IVIg, glucocorticoids | Recovered | [29] |

| ITP flare | 1 | F | 34 | IVIg, glucocorticoids | Improvement | [30] |

| ITP | 1 | F | 41 | IVIg, platelet transfusion | Recovered | [31] |

| ITP | 3 | 2 M 1 F |

66 57 79 |

IVIg and thrombopoietin (2 cases). No treatment (1 case) | Recovered | [113] |

| TTP | 1 | F | 57 | IVIg, glucocorticoids, plasma exchange and plasma infusion | Recovered | [34] |

| ITP (1 ITP flare) | 3 | F M M |

57 72 39 |

IVIg IVIg IVIg |

Recovered Recovered Recovered |

[114] |

| ITP | 1 | M | 53 | IVIg, glucocorticoids, platelet transfusion, thrombopoietin | Recovered | [115] |

| ITP | 1 | M | 38 | IVIg, glucocorticoids | Recovered | [116] |

| ITP | 1 | F | 51 | IVIg, glucocorticoids, platelet transfusion, thrombopoietin | Recovered | [117] |

| ITP | 1 | F | 73 | IVIg, glucocorticoids, platelet transfusion | Recovered | [118] |

| ITP | 1 | M | 86 | IVIg, glucocorticoids | Recovered | [119] |

| ITP | 1 | M | 41 | IVIg, glucocorticoids | Recovered | [120] |

| ITP | 14 | 7 M 7 F | Median age 64 | IVIg in 9, glucocorticoids in 7, thrombopoietin in 3 | Recovered, 3 Relapsed | [121] |

| ITP flare | 1 | F | 58 | IVIg, glucocorticoids | Recovered | [122] |

| ITP | 1 | M | 48 | IVIg, glucocorticoids | Recovered | [123] |

| ITP | 1 | F | 29 | Glucocorticoids, platelet transfusion | Recovered | [124] |

| ITP | 3 | F M M |

69 88 31 |

Glucocorticoids Glucocorticoids Glucocorticoids |

Recovered Recovered Recovered |

[125] |

| ITP | 1 | M | 67 | IVIg, glucocorticoids, platelet transfusion, thrombopoietin | Recovered | [126] |

| ITP | 1 | F | 2 | None | Recovered | [127] |

| ITP | 1 | M | 89 | IVIg, glucocorticoids, platelet transfusion | Death | [128] |

| ITP | 1 | M | 22 | IVIg, platelet transfusion | Recovered | [129] |

| ITP | 1 | F | 63 | IVIg | Recovered | [130] |

| ITP | 1 | M | 16 | Glucocorticoids | Improvement | [25] |

Abbreviations. ITP: immune thrombocytopenic purpura. F: female. M: male. IVIg: intravenous immunoglobulins. TTP: thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura.

In a retrospective single-center study, Chen and Colleagues enrolled 271 patients to determine the association of thrombocytopenia during the delayed-phase of COVID-19, i.e. 14 days after symptoms appeared. Thrombocytopenia occurred in 11.8% of cases, mostly in elderly or in the presence of low lymphocyte count at admission. This was significantly associated with the duration of hospital stay, being mostly transient, lasting less than 7 days. In three patients who developed a dramatic decline in platelet count, without other putative explanations, bone marrow aspiration demonstrated an impaired megakaryocyte maturation, similar to what is observed in ITP. The authors therefore speculated that the delayed-phase platelet decrease might have been immune mediated in these patients [35]. In other cases, the management with immunoglobulins was preferred to glucocorticoids, because of the possible harmful effect of the latter in SARS-CoV-2 infection hypothesized during the first months of the pandemic [36].

3.2. Antiphospholipid antibodies and syndrome

Since the earliest reports, COVID-19 has been associated with coagulation abnormalities and includes a pro-thrombotic state, affecting the prognosis through both arterial and venous thrombotic events [37], observed in up to 31% of patients in intensive care units. Potential underlying mechanisms include immobilization, hypoxia, or disseminated coagulopathy [38]. Serum antiphospholipid antibodies (aPLs), including IgG and IgM anti-cardiolipin (aCL), IgG and IgM anti-beta2-glycoprotein I (β2-GPI) antibodies and lupus anticoagulant (LAC), may be found in up to 12% of young healthy subjects and 18% of elderly people with chronic diseases [39]. Most individuals with aPLs do not experience thrombotic events, for which a “second hit” is probably required to develop the antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), that is based on the confirmation of serum autoantibodies on two or more occasions at least 12 weeks apart. Critical illnesses, infections and aging [40] are known to trigger aPLs, either transiently or chronically with or without the development of thrombosis [41,42]. Table 3 illustrates the cases of aPLs that are either associated with or not associated with thrombosis. These findings seem to suggest an additional role of aPLs or LAC in the pathogenesis of thrombosis (either arterial or venous) in patients with COVID-19.

Table 3.

APL and APS cases associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

| Number of patients | Sex | Mean or median age (years) | Number of patients with APL (n° or n°/tot tested) | APL (n°/tot tested) | Manifestations in APL population | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 2 M 1 F |

69 65 70 |

3 | aCL IgA 3/3 anti–β2-GPI IgA and IgG 3/3 |

Multiple cerebral infarctions, lower limbs and hand finger ischemia | [131] |

| 2 | 1 M 1 F |

58 29 |

2 | aCL IgG and IgM 2/2 | Splenic infarct, cerebral infarction – peroneal and tibial artery thrombosis | [132] |

| 1 | M | 82 | 1 | aCL IgA, IgM, IgG | Pulmonary embolism | [133] |

| 2 | 2 M | 79 | 1 | aCL IgM | Multiple cerebral infarcts | [134] |

| 1 | F | 49 | 1 | aCL IgG and IgM | Deep vein thrombosis in the four extremities | [135] |

| 1 | M | 72 | 1 | aCL IgM and anti-β2-GPI IgM | ICU patient, no evident thrombosis but signs of endothelial stimulation | [136] |

| 24 | 14 M 10 F | 64.3 | 2 | aCL IgM 2/24 anti-β2-GPI IgM 2/24 |

Venous thromboembolism | [45] |

| 57 | 122 M 28 F | 63 | 50 | LAC 50/57 aCL IgM 1/57 | Thrombotic events | [137] |

| 35 | 24 M 11 F |

56.6 | 31 | LAC 31/34 | Venous thrombosis | [138] |

| 25 | 17 M 8 F | 47.7 | 24 | aCL IgG 13/25 aCL IgM 5/25 aCL IgA 7/25 a-β2-GPI IgG 1/25 a-β2-GPI IgM 0/25 a-β2-GPI IgA 3/25 LAC 23/25 |

Massive pulmonary embolism | [46] |

| 79 | 45 M 34 F | ≈57 | 31 | aCL IgG 4/79 aCL IgM 2/79 aCL IgA 17/79 a-β2-GPI IgG 12/79 a-β2-GPI IgM 1/79 a-β2-GPI IgA 19/79 LAC 2/79 |

Cerebral infarction, myocardial infarction | [44] |

| 35 | 26 M 9 F | 73 | 3 | aCL IgG 1/35 aCL IgM 2/35 aPS/PT IgG 1/35 aPS/PT IgM 2/35 |

Multiple recent microvascular and macrovascular thrombosis at autopsy | [139] |

| 122 | 60 M 62 F | 54.3 | 41 | aCL IgG 15/112 aCL IgM 3/112 aCL IgA 2/121 a-β2-GPI IgG 7/112 a-β2-GPI IgM 8/112 a-β2-GPI IgA 4/121 LAC 16/72 |

10 Thrombosis (venous or arterial) | [140] |

| 31 | 28 M 3 F | 63 | 23 | aCL IgG 6/31 aCL IgM 1/31 aCL IgA 3/31 a-β2-GPI IgG 3/31 a-β2-GPI IgM 1/31 a-β2-GPI IgA 3/31 LAC 21/31 aPS/PT 7/31 |

7 Thrombosis (venous or arterial) | [141] |

| 74 | N.A. | 63.5 | 65 | aCL IgG or aCL IgM or a-β2-GPI IgG or a-β2-GPI IgM or a-β2-GPI IgA 9/74 LAC 63/74 |

5 Thrombosis (venous or arterial) | [142] |

| 86 | 54 M 32 F | 66.6 | 12/31 | aCL IgG or aCL IgM or a-β2-GPI IgG or a-β2-GPI IgM or a-β2-GPI IgA or LAC 12/31 | 5 Acute ischemic strokes | [143] |

| 1 | M | 69 | 1 | aCL IgG and IgM, LAC | Thrombotic microangiopathy | [144] |

| 844 | 405 M 439 F | 59 | 7/9 | aCL IgG or aCL IgM or a-β2-GPI IgG or a-β2-GPI IgM or LAC 7/9 | 7 Acute ischemic strokes | [145] |

| 68 | 34 M 34 F | ≈57 | 30 | aCL IgG 0/62 aCL IgM 1/62 a-β2-GPI IgG 0/62 a-β2-GPI IgM 1/60 LAC 30/68 |

19 Thrombosis (venous or arterial) | [146] |

| 21 | 9 M 12 F | 62 | 12 | aCL IgG 2/21 aCL IgM 3/21 a-β2-GPI IgG 1/21 a-β2-GPI IgM 0/21 LAC 21/31 aPS/PT/annexin IgG or IgM 11/21 |

2 Pulmonary thromboembolisms | [147] |

| 1 | M | 31 | 1 | aCL IgM, LAC | No thrombotic event | [148] |

| 27 | 12 M 15 F | 58 | 7 | aCL IgG or IgM 0/27 a-β2-GPI IgG or IgM a-β2-GPI IgA 1/27 LAC 6/27 |

3 Thrombosis (venous or arterial) | [149] |

| 1 | F | 34 | 1 | LAC | Acute ischemic stroke | [150] |

| 43 | 27 M 16 F | ≈63.2 | 16 | aCL IgG or IgM 0/43 a-β2-GPI IgG or IgM 0/43 LAC 16/43 |

1 Thrombosis | [151] |

| 1 | M | 48 | 1 | aCL IgG and IgM a-β2-GPI IgG and IgM LAC |

APS flare with limb arterial ischemia | [152] |

| 89 | 61 M 7 F | 68 | 64 | aCL IgG or IgM 7/89 a-β2-GPI IgG or IgM 6/89 LAC 59/89 |

6 Deep vein thrombosis, 6 pulmonary embolisms | [153] |

| 33 | 17 M 16 F |

70 | 8 | aCL IgG 5/33 aCL IgM 6/33 a-β2-GPI IgG 2/33 a-β2-GPI IgM 2/33 |

No thrombotic events | [154] |

| 64 | 32 M 32 F | 62 | 64 | aCL IgG or IgM a-β2-GPI IgG or IgM |

N.A. | [155] |

| 19 | 10 M 9 F | 65 | 10 | aCL IgG 2/10 aCL IgM 1/10 aCL IgA 6/10 a-β2-GPI IgG 6/10 a-β2-GPI IgM 0/10 a-β2-GPI IgA 7/10 LAC 1/10 |

4 Acute ischemic strokes | [156] |

| 2369 | N.A. | N.A. | 1 | aPL (not defined) | N.A. | [157] |

| 56 | 33 M 23 F | 66 | 24 | aCL IgG 16/56 aCL IgM 3/56 a-β2-GPI IgG 1/56 a-β2-GPI IgM 4/56 |

N.A. | [158] |

| 56 | N.A. | N.A. | 30 | aCL or a-β2-GPI IgG or IgM 5/56 LAC 25/56 |

N.A. | [43] |

| 1 | M | 31 | 1 | LAC | Acute limb ischemia, myocardial infarction | [159] |

| 1 | F | 30 | 1 | aCL IgG and IgM, a-β2-GPI IgG and IgM, LAC | No thrombotic events, Evans syndrome | [160] |

Abbreviations. aPL: antiphospholipid antibody. APS: antiphospholipid syndrome. M: male. F: female. aCL: anti-cardiolipin antibody. Ig: immunoglobulin. A-β2-GPI: anti-beta2glycoprotein I. N.A.: information not available. ICU: intensive care unit. PTT: partial thromboplastin time. LAC: lupus anticoagulant. aPS/PT: anti phosphatidylserine/prothrombin.

Whether SARS-CoV-2 induces the development of aPLs or acts as a second hit in previously positive patients remains unclear and the clinical significance of aPLs in COVID-19 is still to be elucidated. Some authors have reported a high incidence of LAC in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Thus, for instance, in a cohort of 56 patients, while twenty-five were found to be positive for LAC, five of the 50 patients that were tested had aCL or anti–β2 GPI antibodies, of which three were associated with LAC [43]. APLs may develop in critically ill patients [44], as the reactivity is found in 31 out of 66 patients requiring ICU admission and in none of those in non-critical conditions. The analysis of previous sera revealed that aPLs appear at a median time of 39 days following disease onset, suggesting that critically ill patients with longer disease duration are more likely to develop aPLs.

On the other hand, the association with aPLs is not clear in the analysis of patients with thrombosis. In fact, in a cohort of 785 patients with COVID-19, out of the 24 who had a venous thromboembolism without known risk factors (besides the infection), only two patients were weakly positive for aCL IgM and anti-β2-GPI IgM [45]. On the contrary, in a study of a separate series of patients, a majority of patients with severe thrombotic events had positive aPLs [44,46]. Other authors suggest that these data should be interpreted with caution, as false positive LAC testing might be due to the marked elevation in C-reactive protein (CRP) levels seen in pulmonary or systemic inflammation [47]. Moreover, concomitant therapy with anticoagulants can alter LAC testing [48] and aPL titers are not consistently defined in these studies, making the clinical course difficult to evaluate.

3.3. Systemic lupus erythematosus

A few cases of de novo appearance of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) or SLE-like syndrome associated with COVID-19 have been reported. In addition, flares of previously diagnosed SLE have been described. Table 4 illustrates the main clinical manifestations and the outcomes of the reported cases.

Table 4.

Systemic lupus erythematosus cases associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

| Patients number | Sex | Age (years) | Manifestations | Treatment | Outcome | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 18 | Pericardial tamponade with shock, ventricular dysfunction, pleural serositis, nephritis, ANA, dsDNA, secondary APS, anemia, thrombocytopenia, low complement | Glucocorticoids, plasma exchange, HCQ, anticoagulation | Death | [161] |

| 1 | F | 23 | Nephritis, ANA, dsDNA, low complement, aPL, direct Coombs, varicella-like rash | Glucocorticoids | Death | [162] |

| 1 | F | 85 | Thrombocytopenia, pleural effusion, proteinuria, ANA, low complement, finger vasculitis | Glucocorticoids, HCQ | Improvement | [163] |

| 1 | M | 62 | Nephritis, neuropsychiatric symptoms, lymphopenia, ANA | Glucocorticoids, TCZ | Improvement | [164] |

| 1 (flare) | M | 62 | During flare: low complement, aPL, thrombocytopenia with cerebral hemorrhage, hemolytic anemia | Glucocorticoids, IVIg, rituximab | Death | [165] |

| 1 (flare) | M | 63 | During flare: APS. | Glucocorticoids, HCQ, anticoagulation | Death | [166] |

Abbreviations. F: female. ANA: antinuclear antibodies. dsDNA: anti double strand DNA. APS: antiphospholipid syndrome. HCQ: hydroxychloroquine. M: male. aPL: antiphospholipid antibody. TCZ: tocilizumab. IVIg: intravenous immunoglobulins.

3.4. ANCA-associated vasculitis

A small number of cases of anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA)-associated vasculitis related to COVID-19 have been reported and are listed in Table 5 .

Table 5.

ANCA-associated vasculitis cases related to SARS-CoV-2 infection.

| Patients | Sex | Age (years) | Manifestations | Treatment | Outcome | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | M M |

64 46 |

Pauci-immune crescentic glomerulonephritis, MPO-ANCA Focal necrotizing glomerulonephritis, skin vasculitis, c-ANCA |

Glucocorticoids, rituximab Glucocorticoids, rituximab |

Improvement Improvement |

[167] |

| 1 | F | 37 | Pulmonary hemorrhage, PR3-ANCA | Glucocorticoids, plasmapheresis, IVIg | Death | [168] |

Abbreviations. M: male. MPO-ANCA: myeloperoxidase antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. c-ANCA: cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. PR3-ANCA: proteinase 3 antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. IVIg: intravenous immunoglobulins.

3.5. Kawasaki-like disease

The pediatric population appears to be less affected than adults that develop severe SARS-CoV-2 infection. Thus, the pediatric cases comprise only 1–5% of total COVID-19 cases observed, and those that do become infected generally develop mild disease and low mortality [49]. This has been ascribed to the decreased level of maturity and function (binding affinity) of ACE2, the likely cell receptor for the virus, with reduced virus binding to cells. In addition, differences in the immune response to SARS-CoV-2 was also thought to play a role [50]. Nonetheless, in the early months of 2020, pediatricians began reporting cases of children with fever and signs of systemic inflammation with features in common with Kawasaki disease. Kawasaki disease is an acute and usually self-limiting vasculitis of medium sized vessels, which almost exclusively affects children. In some cases it is complicated by hemodynamic instability, a condition known as Kawasaki disease shock syndrome (KDSS) [51], or by a macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) [52]. In Table 6 Kawasaki disease-like cases are displayed.

Table 6.

Kawasaki-like cases associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

| Patients number (confirmed/non confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection) | Sex | Mean or median age (months/years) | Manifestations | Treatment | Outcome | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (confirmed) | F | 6m | Complete KD | ASA, IVIg | Recovered | [169] |

| 1 (confirmed) | M | 5y | Atypical KD | ASA IVIg glucocorticoids |

Recovered | [170] |

| 1 (confirmed) | M | 8y | Complete KD, shock | ASA, IVIg, TCZ | Recovered | [171] |

| 1 (confirmed) | M | 4m | Complete KD | ASA IVIg |

Recovered | [172] |

| 8 (2 confirmed) | 5 M 3F |

8.8y | Atypical KD, shock, toxic shock syndrome symptoms | 8 IVIg, + ASA in 6, glucocorticoids in 5 | 1 Death 7 Recovered 1 Coronary aneurysm |

[65] |

| 4 (all confirmed) | 3 M 1F |

10y | Atypical KD, shock | 1: IVIg, TCZ, anakinra 2: IVIg, TCZ 3: IVIg, TCZ 4: TCZ |

2 Coronary artery abnormalities final outcome unknown | [173] |

| 10 (8 confirmed) | 7 M 3F |

7.5y | 5 complete KD, 5 atypical KD 5 shock |

10 IVIg, + ASA in 2, + glucocorticoids in 8 | Recovered 2 Coronary artery aneurysms |

[59] |

| 21 (19 confirmed) | 9 M 12F |

7.9y | 11 complete KD, 10 atypical KD 12 shock |

21 IVIg, plus ASA in 21, plus glucocorticoids in 10 | Recovered | [60] |

| 16 (11 confirmed) | 8 M 8F |

10y | 10 complete 6 atypical 7 severe (ICU) |

First line: 15 IVIg + ASA 1 HCQ Second line: 4 IVIg again, 1 IVIg + glucocorticoids, 2 glucocorticoids, 1 anakinra, 1 TCZ. |

Improved/Recovered 3 Coronary abnormalities |

[62] |

| 58 (45 confirmed) | 35 M 33F |

9y | 23 fever and inflammatory state. 29 shock 13 complete KD |

IVIg in 41, glucocorticoids in 37, anakinra in 3, infliximab in 8 | 1 Death 8 Coronary artery aneurysms |

[64] |

| 17 (all confirmed) | 8 M 9F |

8y | 8 Complete KD 5 Incomplete KD 13 shock |

4 ASA 14 glucocorticoids 13 IVIg 1 TCZ |

Recovered 1 Coronary artery aneurysm |

[174] |

| 35 (31 confirmed) | 18 M 17F |

10y | 35 Fever and inflammatory state 28 Shock |

35 IVIg, 12 glucocorticoids, 3 anakinra | Recovered | [175] |

| 3 (3 confirmed) | 2 M 1 F |

15.3y | 3 overlapping KD and TSS symptoms | 2 IVIg, 2 ASA, 1 steroid | Recovered 2 Coronary artery dilatations |

[176] |

| 1 confirmed | M | 14y | Atypical KD, shock | Infliximab | Recovered | [177] |

| 44 (confirmed) | 20 M 24 F |

7.3y | 44 Fever 37 gastrointestinal symptoms 22 shock |

42 glucocorticoids, 36 IVIg, 8 anakinra | Recovered 1 Renal replacement therapy |

[63] |

| 33 (confirmed) | 20 M 13 F |

10y | 31 Fever Inflammatory state 21 hypotension |

18 IVIg, 17 glucocorticoids, 12 TCZ | 1 Death 32 Recovered 2 Coronary artery ectasias |

[66] |

| 35 (27 confirmed) | 27 M 8 F |

11y | 33 fever 21 shock |

35 IVIg, glucocorticoids, biologics | 1 Death 34 Recovered 6 Coronary artery aneurysms |

[67] |

| 2 (confirmed) | 2 M | 12y 7y |

Complete KD | 1 steroid, 1 IVIg + steroid | Recovered | [178] |

| 1 (confirmed) | F | 6y | Atypical KD, shock | IVIg, ASA | Recovered | [179] |

| 1 (non-confirmed) | M | 3y | Complete KD | IVIg | N.A. | [180] |

| 1 (non-confirmed) | M | 5y | Atypical KD, shock | IVIg, ASA, glucocorticoids | Recovered | [181] |

| 6 (confirmed) | 1 M 5 F |

8.5y | KD (incomplete), shock | 6 IVIg, 5 glucocorticoids, 1 anakinra | Recovered 1 Coronary artery dilatation |

[182] |

| 20 (19 confirmed) | 10 M 10 F |

10y | Atypical KD, shock | 20 IVIg, + glucocorticoids in 2, + anakinra in 1, + TCZ in 1 | Recovered | [183] |

| 1 (non-confirmed) | F | 3y | Atypical KD | IVIg, ASA | Recovered | [184] |

| 4 (confirmed) | 1 M 3 F |

9.2y | Atypical KD | 4 IVIg, 3 glucocorticoids, 3 ASA |

Recovered | [185] |

| 156 (79 confirmed) | M/F ratio 0.96 | 8y | 66 Atypical KD, 72 ICU | N.A. | N.A. | [186] |

| 15 (at least 12 confirmed) | 11 F 4 F |

8.8y | 13 Atypical KD, 10 shock | 10 IVIg, 5 glucocorticoids, 11 ASA | Recovered 8 Coronary artery abnormalities |

[187] |

| 1 (confirmed) | F | 11y | Atypical KD, shock | IVIg, glucocorticoids, TCZ | Recovered | [188] |

| 1 (confirmed) | M | 16y | Atypical KD, shock | Steroid | Recovered | [189] |

| 1 (confirmed) | M | 10y | Atypical KD, shock | N.A. | Critically ill at last follow up | [190] |

| 33 (confirmed) | 20 M 13 F |

8.6y | 21 Complete KD, 16 shock |

33 IVIg, 29 ASA, 23 steroid, 4 anakinra, 3 TCZ, 1 infliximab | Recovered (16 coronary artery abnormalities) | [191] |

| 1 (non-confirmed) | F | 8y | Atypical KD, shock | IVIg, steroid, ASA | Recovered | [192] |

| 15 (confirmed) | 11 M 4 F |

12y | 15 Atypical KD, shock | 12 IVIg, 2 ASA, 3 steroid, 12 TCZ, 2 anakinra | 1 Death 3 Coronary artery abnormalities |

[68] |

| 99 (95 confirmed) | 53 M |

∼ 33y |

36 KD (complete or atypical) 29 shock |

69 IVIg, 63 steroids | 2 Death 9 Coronary artery aneurysms |

[193] |

| 186 (131 confirmed) | 115 M | 8.3y | 74 KD (complete or atypical), 62 ICU | 144 IVIg, 91 steroid, 14 TCZ/siltuximab, 24 anakinra | 4 Death 15 Coronary artery aneurysms |

[69] |

| 1 (confirmed) | M | 16y | Atypical KD, shock | IVIg, TCZ | Recovered | [194] |

| 1 (confirmed) | M | 9y | MIS-C | Glucocorticoids | Recovered | [195] |

| 1 (confirmed) | F | 35y | Atypical KD | None | Recovered | [196] |

| 1 (confirmed) | F | 36y | KD and shock | Glucocorticoids, IVIg, ASA | Recovered | [197] |

| 6 (3 confirmed) | 3 M 3 F | 8.1y | 4 KD (complete and atypical), 2 myocarditis 3 shock |

None | Recovered | [198] |

| 10 (8 confirmed) | 4 M 6 F | 10.2y | 5 complete KD, 5 atypical KD 4 shock |

9 IVIg, 5 glucocorticoids, 1 TCZ | Recovered 1 Coronary artery aneurysm |

[199] |

| 1 (confirmed) | M | 14y | Atypical KD, shock/MIS-C | IVIg, ASA | Recovered | [200] |

| 1 (confirmed) | M | 6y | Atypical KD | IVIg, ASA | Recovered | [201] |

| 78 | 52 M 26 F | 11y | PIMS-TS 68 shock |

59 IVIg, 57 glucocorticoids, 8 anakinra, 7 infliximab, 3 TCZ, 1 rituximab, 45 ASA | 2 Deaths 18 Coronary artery aneurysms |

[202] |

| 1 (confirmed) | M | 45y | MIS-C | IVIg, TCZ | Recovered | [203] |

| 7 (2 confirmed) | 5 M 2 F | 6.1m | 3 complete KD 4 atypical KD | 7 IVIg, 7 glucocorticoids, 7 ASA, 6 infliximab, 2 anakinra | 1 Death 6 Coronary artery aneurysms |

[204] |

| 1 (confirmed) | F | 19y | Complete KD/MIS-C | IVIg, glucocorticoids, TCZ, colchicine | Recovered | [205] |

| 28 (all confirmed) | 16 M 12 F | 9y | MIS-C | 20 IVIg, 17 glucocorticoids, 5 anakinra, | Recovered 6 Coronary artery abnormalities |

[206] |

| 8 (all confirmed) | N.A. | N.A. | Atypical KD | IVIg, glucocorticoids, ASA | N.A. | [207] |

| 1 (confirmed) | M | 19y | Atypical KD | None | Recovered | [208] |

| 31 (30 confirmed) | 18 M 13 F | 7.6y | MIS-C/KD | 20 IVIg, 21 glucocorticoids, | 1 Death 3 Coronary artery abnormalities |

[209] |

| 1 (confirmed) | M | 16y | PIMS-TS shock | IVIg, glucocorticoids, ASA | Recovered Coronary aneurysm |

[210] |

| 1 (confirmed) | M | 5m | Atypical KD | IVIg, ASA | Recovered Coronary artery abnormalities |

[211] |

| 2 (all confirmed) | N.A. | N.A. | Atypical KD | 2 IVIg | N.A. | [212] |

| 20 (19 confirmed) | 15 M 5 F | 10.6y | PIMS-TS | N.A. | N.A. | [213] |

| 1 (non-confirmed) | F | 7 | PIMS-TS | IVIg, glucocorticoids, ASA | Recovered | [214] |

| 3 (2 confirmed) | 2 M 1 F | 6y | PIMS-TS 2 shock |

IVIg, ASA | Recovered | [215] |

| 570 (565 confirmed) | 316 M 254 F | 8y | MIS-C 202 shock |

424 IVIg, 331 glucocorticoids, 309 ASA | 10 Deaths 95 Coronary artery abnormalities |

[216] |

| 30 (2 confirmed) | 12 M 2 F | 2y | 22 complete KD, 8 atypical KD | 30 IVIg, 14 IVIg + glucocorticoids, | Recovered 2 Coronary artery aneurysms |

[217] |

| 25 (17 confirmed) | 15 M 10 F | 12.5y | MIS-C | 23 IVIg, 20 glucocorticoids, 10 TCZ, 4 infliximab, 1 anakinra | Recovered 7 Coronary artery abnormalities |

[218] |

| 11 (all confirmed) | 9 M 2 F | 59m | PIMS-TS, 5 shock | N.A. | 2 Deaths | [219] |

| 1 (confirmed) | M | 45y | KD | IVIg, TCZ, topical glucocorticoids | Recovered | [220] |

| 1 (confirmed) | F | 13y | MIS-C | IVIg | Recovered | [221] |

| 45 (all confirmed) | 24 M 21 F | 7y | MIS-C | 18 IVIg, 27 glucocorticoids | 5 Deaths | [222] |

| 1 (confirmed) | M | 14y | MIS-C | None | Recovered | [223] |

| 28 (all confirmed) | 14 M 14 F | 11.4y | MIS-C, 23 shock | 20 IVIg, 24 ASA, 27 glucocorticoids | Recovered | [224] |

| 9 (all confirmed) | 4 M 5 F | 12y | MIS-C, 5 shock | 8 IVIg, 6 ASA, 7 TCZ | Recovered | [225] |

| 1 (confirmed) | M | 9y | PIMS-TS | IVIg, glucocorticoids, ASA | Recovered | [226] |

| 6 (all confirmed) | 5 M 1 F | 7.7y | MIS-C, 5 shock | 4 IVIg, 3 ASA, 2 glucocorticoids | 4 Deaths | [227] |

| 3 (all confirmed) | N.A. | N.A. | MIS-C | N.A. | N.A. | [228] |

| 5 (all confirmed) | N.A. | 84.4m | PMIS-TS | None | Recovered | [229] |

| 1 (confirmed) | F | 7m | MIS-C | Glucocorticoids | Death | [230] |

| 2 (1 confirmed) | 2 M | 31m | PIMS-TS | None | 1 Death | [231] |

| 1 (confirmed) | N.A. | N.A. | MIS-C, shock | IVIg, ASA | Recovered | [232] |

| 1 (confirmed) | F | 10y | MIS-C, shock | None | Recovered | [233] |

| 1 (confirmed) | F | 5y | MIS-C, shock | IVIg, ASA | Recovered | [234] |

| 3 (all confirmed) | 1 M 2 F | 8.3y | MIS-C, shock | 2 IVIg, 3 glucocorticoids, 1 TCZ | Recovered | [235] |

| 10 (8 confirmed) | 10 M 6 F | 9.2y | MIS-C, 10 shock | 5 IVIg, 10 glucocorticoids, 2 anakinra | Recovered 4 Coronary artery abnormalities |

[236] |

| 6 (all confirmed) | 2 M 4 F | 6y | MIS-C, 5 shock | 6 IVIg, 6 glucocorticoids | Recovered | [237] |

| 12 (all confirmed) | 9 M 3 F | 8y | MIS-C | N.A. | Recovered 2 Coronary artery abnormalities |

[238] |

| 15 (all confirmed) | 9 M 6 F | 11.5y | MIS-C | 12 IVIg, 3 glucocorticoids, 9 TCZ, 2 anakinra, 2 ASA | 1 Death 1 Coronary artery aneurysm |

[239] |

| 23 (15 confirmed) | 11 M 12 F | 7.2y | MIS-C, 15 shock | 15 IVIg, 22 glucocorticoids | Recovered | [240] |

| 1 (confirmed) | F | 14y | MIS-C, shock | IVIg, glucocorticoids, | Pseudotumor cerebri, improvement | [241] |

| 23 (4 confirmed) | 17 M 6 F | 6.5y | MIS-C, 9 shock | 23 IVIg, 15 glucocorticoids, 2 TCZ | 15 Recovered and no deaths at last follow up | [242] |

| 1 (confirmed) | M | 11y | MIS-C, shock | IVIg, ASA, glucocorticoids, infliximab | Coronary artery aneurysms, temporary pacing for atrioventricular block | [243] |

| 52 (all confirmed) | 31 M 21 F | 10.7y | MIS-C, 25 shock | 28 IVIg, 24 glucocorticoids, 3 anakinra, 1 TCZ, 1 adalimumab, 1 infliximab | 43 Recovered at last follow up | [244] |

| 27 (22 confirmed) | 14 M 13 F | 6y | MIS-C, 12 shock | 19 IVIg, 17 glucocorticoids, 17 ASA | Recovered 3 coronary artery abnormalities |

[245] |

| 3 (all confirmed) | 1 M 2 F | 8.3y | MIS-C, 3 shock | 2 IVIg, 3 glucocorticoids, 3 ASA | Recovered 3 surgery for acute appendicitis 1 coronary artery abnormalities |

[246] |

| 1 (confirmed) | M | 5y | MIS-C, shock | TCZ | Death | [70] |

| 1 (confirmed) | M | 10y | PIMS-TS, shock | IVIg, glucocorticoids, anakinra, ASA | Recovered | [247] |

| 1 (confirmed) | M | 3y | MIS-C | Glucocorticoids | Recovered | [248] |

| 10 (all confirmed) | 3 M 7 F | 9.9y | MIS-C, 1 shock | 7 IVIg, 6 glucocorticoids | Recovered | [249] |

| 33 (18 confirmed) | 19 M 14 F | 2.8y | PIMS-TS, 3 shock | 24 IVIg, 18 glucocorticoids, 3 anakinra | Recovered | [250] |

| 1 (confirmed) | F | 25y | MIS-C, shock | IVIg, ASA | Recovered | [251] |

| 54 (49 confirmed) | 25 M 29 F | 7y | MIS-C | 45 IVIg, 41 glucocorticoids, | Recovered | [252] |

| 1 (confirmed) | F | 15y | MIS-C | IVIg, glucocorticoids, ASA | Recovered Coronary artery aneurysms |

[253] |

| 1 (confirmed) | F | 8y | PIMS-TS | IVIg, glucocorticoids | Recovered | [254] |

| 2 (all confirmed) | 2 F | 11.5y | PIMS-TS, shock | None | Recovered 2 Surgery for acute appendicitis |

[255] |

| 9 (all confirmed) | N.A. | N.A. | MIS-C | N.A. | N.A. | [256] |

| 13 (all confirmed) | 23 M 18 F | ∼8.8y | MIS-C | 8 IVIg, 13 glucocorticoids, 7 anakinra | N.A. | [257] |

| 44 (40 confirmed) | N.A. | N.A. | MIS-C, 19 hepatitis | N.A. | Recovered 6 Coronary artery abnormalities |

[258] |

| 18 (all confirmed) | 14 M 4 F | 7.7y | MIS-C | N.A. | N.A. | [259] |

| 2 (1 confirmed) | 1 M 1 F | 8.5y | PIMS-TS | 1 anakinra | Recovered 1 Coronary artery abnormalities 1 Surgery for acute appendicitis |

[260] |

| 1 (confirmed) | F | 10y | MIS-C, pancreatitis | IVIg, ASA | Recovered | [261] |

| 35 (N.A.) | 22 M 13 F | 8.6y | MIS-C | 19 IVIg, 1 infliximab, glucocorticoids, ASA | Recovered 1 Ileocolic resection with ileostomy |

[262] |

Abbreviations. Confirmed: PCR or serology positive. m: months. F: female. M: male. KD: Kawasaki disease (complete: meeting American Heart Association criteria. Atypical: not fulfilling criteria for complete KD). ASA: acetylsalicylic acid. IVIg: intravenous immunoglobulins. y: years. m: months. LN: lymphadenopathy. TCZ: tocilizumab. KD: Kawasaki disease. KDSS: Kawasaki disease shock syndrome. TSS: toxic shock syndrome. ICU: intensive care unit. MIS-C: multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children. PIMS-TS: pediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2. N.A.: information not available.

Pediatric COVID-19 cases may develop features similar to Kawasaki disease and this is of particular interest since a role for infectious agents has previously been proposed in the pathogenesis of Kawasaki disease. This is particularly true for respiratory viruses that had previously been reported to be a ‘new’ RNA virus that affects upper respiratory tract detected in the bronchial epithelium [53,54].

The pediatric manifestations described during the pandemic are not entirely representative of Kawasaki disease since the criteria established by the 2017 American Heart Association [55] are infrequently met. As a consequence, the pediatric syndrome associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection has been coined ‘pediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection’ (PIMS-TS) in Europe and ‘multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children’ (MIS-C) in the United States [56,57]. Case definitions by the World Health Organization (WHO), Royal College of Pediatrics and Child Health (UK) and Center for Disease Control (CDC, US) are slightly different but all include persistent fever, laboratory evidence of inflammation and single or multi-organ dysfunction following exclusion of other microbial causes. Confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection is needed for meeting the criteria established by the WHO and CDC [58]. When compared with classical Kawasaki disease, newly diagnosed Kawasaki-like patients were older and had more signs of cardiac involvement, shock and MAS and required adjunctive steroid treatment more frequently [59]. In a different cohort [60], in addition, all patients had gastrointestinal symptoms, which is uncommon in typical Kawasaki disease and 10-fold higher levels of procalcitonin than those reported in classic KDSS [61]. Another study coined the syndrome ‘Kawa-COVID-19’, confirming the fact that it occurs in older age patients who commonly develop gastrointestinal symptoms and hemodynamic failure. These patients also show lower lymphocyte counts, lower platelet count, higher rate of myocarditis and resistance to therapy following a first immunoglobulin course compared to a historical cohort of patients [62]. The high prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms has also been reported in a series of other cases [63]. Whittaker and colleagues identified three clinical patterns with different manifestations. One with persistent fever and elevated inflammatory markers, but no organ failure or manifestations of Kawasaki disease or toxic shock syndrome. Another with shock, left ventricular dysfunction, elevation of troponin and NT-proBNP. Children with the third pattern fulfilled the American Heart Association diagnostic criteria for Kawasaki disease [64]. Among causes of death, refractory shock and stroke were reported and most patients were on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) support [[65], [66], [67], [68], [69], [70]].

3.6. Arthritis

Only a limited number of cases of acute arthritis have been described in the context of SARS-CoV-2 infection (Table 7 ). In a study by López-González and colleagues, 81 out of 306 patients with proven COVID-19 complained of joint pain at admission, even though none had clear signs of arthritis. Four of them showed crystal-induced acute arthritis during hospitalization, demonstrated by polarized light microscopy analysis of the synovial fluid [71]. Arthritis has been described as an early sign of COVID-19 [72] or occurring after the resolution of the viral infection [73]. In both cases described above, rheumatoid factor and anti-citrullinated peptide antibodies were negative. In one case synovial tissue biopsy was performed, and signs of stromal activation, edema and moderate inflammatory features with perivascular and diffuse infiltrates were observed [72]. In a separate study, three cases of reactive arthritis following SARS-CoV-2 infection were reported; 2 of them completely recovered after NSAIDs therapy [74,75] while one case required intra-articular glucocorticoids injection with moderate improvement [76].

Table 7.

Arthritis cases associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

| Manifestation | Patients number | Sex | Mean or median age (years) | Treatment | Outcome | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arthritis | 4 crystal-induced | M | 60.2 | Glucocorticoids (intra-articular or oral), colchicine | Recovered | [71] |

| Arthritis | 1 oligoarthritis | M | 57 | Spontaneous resolution | Recovered | [73] |

| Polyarthritis | 1 | M | 61 | Glucocorticoids, baricitinib | Recovered | [72] |

| Reactive arthritis | 1 | M | 50 | NSAIDs, intra-articular Steroid injection |

Moderate improvement | [76] |

| Crystal-induced arthritis | 4 | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | [71] |

| Reactive arthritis | 1 | F | 37 | Topical NSAIDs | Recovered | [75] |

| Reactive arthritis | 1 | M | 73 | NSAIDs | Recovered | [74] |

Abbreviations: M: male. NSAIDs: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. N.A.: data not available.

3.7. Skin manifestations

Numerous reports have described several different types of cutaneous manifestations similar to chilblain, urticarial eruptions, diffuse or disseminated erythema among others in COVID-19 patients. Skin lesions reported in COVID-19 patients can be classified into 4 groups: exanthema (varicella-like, papulo-vesicular and morbilliform rash), vascular (chilblain-like, purpuric/petechial and livedoid lesions), urticarial and acro-papular eruption [77]. Skin conditions belonging to the last three mentioned groups, are often described in patients with co-existing autoimmune diseases, especially connective tissue diseases. Criado and colleagues recently discussed the possible mechanisms through which SARS-CoV-2 may exert an action on the skin. Among these are the cytokine release syndrome, the activation of the coagulation and complement systems or the direct entry of the virus following infection of the endothelial cells in dermal blood vessels. Such virus-host interactions may lead to a direct and an indirect damage of the microvasculature of the skin, causing multiple dermatological conditions [78]. According to a recent study, it is possible to establish a temporal relationship between the type of skin involvement and other systemic symptoms and the severity of the disease. Vesicular lesions appear early in the disease course and seem to predate other symptoms, while chilblain-like manifestations are associated with a less severe pulmonary disease and livedo reticularis with the most severe cases of pneumonia [79]. Using the research strategy we employed, we could identify several eligible papers of case reports and case series reporting different kind of autoimmune-like skin lesions in both adults and children with confirmed/suspected COVID-19 disease (Table 8 ).

Table 8.

Autoimmune-like skin lesions in confirmed/suspected COVID-19 patients.

| Skin Lesion | Patients number (sex) | Mean or median age (years) | Treatment for skin lesions | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Periorbital erythema | 1 F, 1 M | 46.5 | Aclometasone dipropionate 0.05% ointment; none | [263] |

| Chilblain-like lesions | 3 F, 1 M | 8.25 | None | [264] |

| Purpuric lesions | 1 M, 2 F | 46 | None | [265] |

| Acral/maculopapular and urticarial lesions | 14 M, 12 F | 28 | None | [266] |

| Livedo reticularis | M | 57 | None | [267] |

| Chilblain-like lesions | F | 35 | None | [87] |

| Chilblain-like lesions | 21 F, 19 M | 22 | None | [268] |

| Chilblain-like lesions | 4 M, 3 F | 14 | None | [269] |

| Bullous hemorrhagic vasculitis | M | 79 | Methylprednisolone | [270] |

| Catastrophic acute lower limbs necrosis | M | 83 | N.A. | [271] |

| Papular-purpuric exanthema | F | 39 | Topical glucocorticoids | [272] |

| Purpuric exanthema | M | 59 | N.A. | [273] |

| Purpuric rash | M | 58 | Mometasone furoate cream | [274] |

| Acute maculopapular eruption | M | 34 | Antihistamines | [275] |

| Chilblain lesions/livedo, Maculopapular exanthema, Palpable purpura, Acute urticaria |

5 F, 5 M 6F, 1 M 3 F, 1 M 3 F, 1 M |

39 53 62 54.5 |

N.A. | [276] |

| Urticarial Vasculitis | 1 F, 1 M | 60 | Prednisone, antihistamines | [277] |

| Schamberg's purpura | F | 13 | N.A. | [278] |

| Chilblain-like lesions | 13 F, 17 M | 11 | None | [279] |

| Maculopapular eruptions | 2 M, 5 F | 66.57 | Glucocorticoids (6/7) | [280] |

| Retiform purpura | F | 79 | N.A. | [281] |

| Pernio-like lesions | 155 F, 163 M | 25 | N.A. | [282] |

| Acral necrosis | F | 74 | N.A. | [283] |

| Cutaneous small vessel vasculitis | F | 71 | Betamethasone dipropionate 0.05% cream | [284] |

| Chilblain-like, purpuric, maculopapular lesions | 29 M, 29 F | 14 | N.A. | [285] |

| Cutaneous small vessel vasculitis | F | 83 | Prednisone | [286] |

| Acral purpuric lesions | M | 12 | N.A. | [287] |

| Urticarial lesions | F | 55 | Betamethasone 0.1% ointment, antihistamines | [288] |

| Urticarial rash | 2 F | 35 | Antihistamines | [289] |

| Acral perniosis | 5 M, 1 F | 14 | N.A. | [290] |

| Chilblain lesions | M | 16 | N.A. | [291] |

| Maculopapular rash | 3 F | 73 | None | [292] |

| Chilblain-like lesions | 142 | 27 | N.A. | [293] |

| Acro-ischemia | 3 | N.A. | N.A. | [294] |

| Chilblain-like lesions | M | 23 | N.A. | [295] |

| Vascular acrosyndromes | 2 M, 2 F | 27 | None | [296] |

| Maculopapular rash | F | 37 | None | [297] |

| Petechial skin rash | M | 48 | Betamethasone dipropionate 0.05% cream, loratadine | [298] |

| Urticarial exanthema | M | 61 | Antihistamines | [299] |

| Chilblain-like lesions | 49 M, 46 F | 23 | None | [300] |

| Vascular lesions | 7 | N.A. | None | [301] |

| Chilblain-like lesions | 35 F, 28 M | 14 | N.A. | [302] |

| Digitate Papulosquamous eruption | 1 | N.A. | None | [303] |

| Chilblain-like lesions | 2 F | 31 | N.A. | [304] |

| Maculopapular rash | 2 F, 1 M | 68 | None | [305] |

| Maculopapular/Papulosquamous rash | 6 M, 2 F | 55.6 | N.A. | [306] |

| Maculopapular/Urticarial/Purpuric/Necrotic rash | 33 M, 19 F | 58 | N.A. | [307] |

| Urticarial rash | 2 F | 48 | None | [308] |

| Urticarial rash | M | N.A. | N.A. | [309] |

| Acral vasculitis, Urticarial rash |

6 2 |

N.A. | N.A. | [310] |

| Acro-ischemia | M | 81 | Aspirin | [311] |

| Chilblain-like, Urticarial rash, Maculopapular rash, Livedo/necrosis |

48 F, 23 M 47 F, 26 M 98 F, 78 M 10 F, 11 M |

32.5 48.7 55.3 63.1 |

N.A. | [79] |

| Chilblain-like | 5 F, 14 M | 14 | N.A. | [312] |

| Acral lesions | 42 M, 32 F | 19.66 | N.A. | [313] |

| Urticarial-like | F | 60 | N.A. | [314] |

| Acute urticaria | 1 F, 1 M | 59 | Antihistamines | [315] |

| Oral erosions, petechiae | F | 19 | IVIg, methylprednisolone | [316] |

| Retiform purpura | 1 | N.A. | N.A. | [317] |

| Chilblain-like lesions | 11 M, 6 F | 32 | N.A. | [318] |

| Livedo reticularis | F | 62 | Heparin | [319] |

| Urticarial skin rash, Chilblain-like lesions |

1 F, 1 M F |

59.5 1 |

Glucocorticoids, antihistamines N.A. |

[320] |

| Livedoid retiform purpura | M | 61 | None | [321] |

| Chilblain-like lesions | 13 M, 9 F | 12 | Antihistamines | [322] |

| Chilblain-like lesions | 18 M, 9 F | 14.4 | None | [323] |

| Chilblain-like lesions | 3 F, 3 M | 35 | N.A. | [324] |

| Chilblain-like lesions | 41 | 16 | N.A. | [325] |

| Chilblain-like lesions | F | 48 | None | [326] |

| Acral lesions | 23 M, 13 F | 11.1 | Topical glucocorticoids/antibiotics or none | [327] |

| AGEP-like (exanthematous pustulosis) | M | 33 | N.A. | [328] |

| Urticarial, vesicular, maculopapular, necrotic lesions | 23 | N.A. | N.A. | [329] |

| Urticarial vasculitis | F | 64 | Antihistamines | [330] |

| Grover-like disease | M | 59 | N.A. | [331] |

| Pernio-like eruption | 4 M, 3 F | 33 | Topical/oral glucocorticoids or none | [332] |

| Chilblain-like lesions | M | 10 | Topical glucocorticoids | [333] |

| Acral lesions | 4 F, 1 M | 3 | None | [334] |

| Vascular lesions | 3 F, 7 M | 39.9 | N.A. | [335] |

| Macular eruption with vasculitis | F | 81 | None | [336] |

| Maculopapular rash | 3 F, 1 M | 21.75 | Hydrocortisone, rupatadine and none | [337] |

| Ulcers | 3 M | 65.6 | Antibiotics | [338] |

| Livedo racemosa and retiform purpura | 4 | 55 | Anticoagulation therapy | [339] |

| Enanthem | 6 | 50 | N.A. | [340] |

| Erythema nodosum | M | 42 | Topical glucocorticoids | [341] |

| Anagen effluvium, urticarial lesions and maculopapular rash | F | 35 | Low dose systemic glucocorticoids and antihistamines | [342] |

| Maculopapular, pernio-like, urticarial, vasculitic and petechial skin lesions | 9 M, 1 F | 63 | Glucocorticoids | [343] |

| Pernio-like skin lesions | F | 77 | LMW heparin | [344] |

| Acute urticaria | M | 54 | Topical glucocorticoids, antihistamines | [345] |

| Maculopapular rash | M | 52 | None | [346] |

| Angioedema and urticaria | M | 40 | Antihistamines | [347] |

| Livedo reticularis | F | 34 | None | [348] |

| Erythema nodosum | F | 54 | Naproxen, hydroxyzine | [349] |

| Chilblain-like lesions | 12 M, 12 F | 32 | N.A. | [350] |

| Acro-ischemic lesions | M | 10 | None | [351] |

| Guttate psoriasis | M | 38 | Topical betamethasone 0.025% | [352] |

| Erythematosus rash | M | 69 | Topical glucocorticoids, antihistamines | [353] |

| Auricle perniosis | F | 35 | Methylprednisolone, heparin | [354] |

| Oral vesicles and maculopapular rash | F | 9 | N.A. | [355] |

| Necrotic acral lesions | M | 59 | Tocilizumab | [356] |

| Urticaria and angioedema | F | 46 | Prednisolone, antihistamines | [357] |

| Chilblains and retinal vasculitis | M | 11 | N.A. | [358] |

| Minor aphthae | 1 F, 3 M | 33 | N.A. | [359] |

| Vascular, urticarial and acropapular lesions | 137 | N.A. | N.A. | [360] |

| Petechial and urticarial lesions | F | 33 | Methylprednisolone, antibiotics, anticoagulation therapy | [361] |

| Purpuric rash and maculopapular eruption | F | 42 | N.A. | [362] |

| Maculopapular lesions | F | 57 | None | [363] |

| Chilblain-like lesions | 8 M, 8 F | 10 | N.A. | [364] |

| Chilblain-like, maculopapular exanthema, urticarial, livedo reticularis-like lesions | 13 | N.A. | N.A. | [365] |

| Acrofacial purpura, necrotic ulcerations | 3 F, 18 M | 57 | N.A. | [366] |

| Mucocutaneous manifestations (e.g. aphthous stomatitis, maculopapular acral rash, urticaria) | 304 | N.A. | N.A. | [367] |

| Chilblain-like lesions | 4 M, 5 F | 11 | N.A. | [368] |

Abbreviations: N.A.: information not available. IVIg: immunoglobulins. F: female. M: male.

3.8. Autoimmune-like neurologic disease

Acute inflammatory neuropathies resembling Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) have been reported in patients with COVID-19. The inflammatory cascade triggered by SARS-CoV-2 may affect the nervous system and the anosmia (loss of sense of smell) and ageusia (loss of sense of taste) have been reported in up to 60% of the infected patients that corroborates the theory of its neurovirulence [80]. The previously known coronaviruses SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV showed neurotropism, entering the brain via olfactory nerves [81]; the often persistent anosmia and ageusia in COVID-19 patients suggest this new coronavirus is also able to target olfactory neurons. Likewise, these viruses can enter the central nervous system via retrograde axonal transport through other cranial and peripheral nerves [81]. Thus, it is not surprising to note the increasing number of reports on COVID-19 patients with acute immune-mediated like neurologic signs and symptoms, published in the literature since the beginning of the pandemic. A recent systematic review showed that published cases of GBS induced by SARS-CoV-2 reported mostly a sensorimotor, demyelinating GBS with a typical clinical presentation, which is similar to GBS cases due to other etiological factors [82]. Table 9 summarizes the case reports/series identified through our research strategy.

Table 9.

Autoimmune-like neurologic lesions in COVID-19 patients.

| Neurologic condition | Patients number (sex) | Mean or median age (years) | Treatment | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | M | 65 | IVIg | [369] |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | M | 21 | Plasma exchange | [370] |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | 1 | N.A. | N.A. | [371] |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | F | 70 | IVIg | [372] |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | M | 64 | N.A. | [373] |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | M | 41 | IVIg | [374] |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | F | 53 | N.A. | [375] |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | M | 71 | IVIg | [376] |

| Miller-Fisher syndrome | M | 36 | IVIg | [377] |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | F | 66 | IVIg | [378] |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | M | 54 | N.A. | [379] |

| Guillain-Barré/Miller-Fisher overlap syndrome AMSAN |

M M |

55 60 |

IVIg IVIg |

[380] |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | F | 54 | IVIg | [381] |

| Miller-Fisher syndrome | F | 51 | IVIg | [382] |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome with leptomeningeal enhancement |

F | 56 | IVIg | [383] |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | F | 76 | N.A. | [384] |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | M | 50 | IVIg | [385] |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | M | 64 | IVIg | [386] |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | 1 M, 1 F | 56.5 | IVIg | [387] |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | M | 72 | IVIg | [388] |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | 4 M, 1 F | 58.4 | IVIg | [389] |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | 3 F | 58.6 | IVIg | [390] |

| Guillain-Barrè syndrome | M | 68 | IVIg | [391] |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | M | ~70 | IVIg | [392] |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome with facial diplegia | M | 58 | IVIg | [393] |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | M | ~60 | IVIg | [394] |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | F | 61 | IVIg | [395] |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome with facial diplegia | M | 61 | Prednisone | [396] |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | M | 54 | IVIg | [397] |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | M | 57 | IVIg | [398] |

| ADEM | F | 64 | IVIg | [399] |

| ADEM-like condition | M | 71 | N.A. | [400] |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | F | 66 | IVIg | [401] |

| CIS | F | 42 | N.A. | [402] |

| ADEM | F | 51 | Methylprednisolone I.V., IVIg | [403] |

| ANE | F | 59 | High dose dexamethasone | [404] |

| Acute demyelination | F | 54 | Glucocorticoids | [405] |

| Demyelinating lesions | F | 54 | High dose dexamethasone Antiepileptic therapy |

[406] |

| AMSAN | F | 70 | IVIg | [407] |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | 7 M | 57 | IVIg | [408] |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | 1 M, 1 F | 26 | Plasma exchange, I.V. labetalol, IVIg | [409] |

| ANM and AMAN | M | 61 | Methylprednisolone I.V., plasma exchange | [410] |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | M | 57 | IVIg | [411] |

| AIDP | M | 68 | IVIg | [412] |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | M | 30 | IVIg, LMW heparin | [413] |

| Guillain-Barré-Strohl syndrome | M | 54 | IVIg | [414] |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | M | 77 | IVIg | [415] |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | 4 M, 1 F | 72.6 | IVIg, Methylprednisolone | [416] |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | F | 67 | Plasma exchange | [417] |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | M | 49 | IVIg | [418] |

| Miller-Fisher syndrome | M | 63 | None | [419] |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | M | 49 | IVIg | [420] |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | M | 11 | IVIg | [421] |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | M | 15 | IVIg | [422] |

| Miller-Fisher syndrome | M | 31 | IVIg | [423] |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | M | 75 | I.V. glucocorticoids, IVIg | [424] |

| AMAN | F | 70 | Plasma exchange, IVIg | [425] |

| Miller-Fisher syndrome | M | 61 | Plasma exchange, IVIg | [426] |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | 11 M, 6 F | 53 | Plasma exchange, IVIg | [427] |

| ATM | M | 24 | I.V. methylprednisolone | [428] |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | F | 56 | N.A. | [429] |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | M | 48 | Plasma exchange | [430] |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | F | 72 | IVIg | [431] |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | M | 69 | IVIg | [432] |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | F | 58 | Plasma exchange | [433] |

| Miller-Fisher syndrome, polyneuritis | M M |

50, 39 |

IVIg, acetaminophen | [434] |

| ATM | M | 60 | Methylprednisone | [435] |

| ANM | F | 69 | Methylprednisolone, plasma exchange | [436] |

| ATM | F | 59 | Methylprednisolone | [437] |

| Miller-Fisher syndrome | F | 74 | IVIg | [438] |

| Miller-Fisher syndrome | F | 50 | IVIg | [439] |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | F | 58 | IVIg | [440] |

Abbreviations: IVIg: intravenous immunoglobulins. N.A.: information not available. M: male. F: female. I.V.: intravenous AMSAN: acute motor sensory axonal neuropathy. ADEM: acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. CIS: clinically isolated syndrome. ANE: acute necrotizing encephalopathy. ATM: acute transverse myelitis. ANM: acute necrotizing myelitis.

4. Discussion

Since February 2020, nearly all the efforts of the international scientific and medical community have been focusing on understanding COVID-19 and our knowledge continues to grow exponentially, but much remains to be elucidated both in terms of pathophysiology and clinical presentation. One of the fundamental issues with regards to COVID-19 is whether the viral infection triggers autoimmunity and is a contributing factor to the risks of complications that develop, or whether patients with autoimmune diseases are at increased risk of infection with SARS-CoV-2 or have a more severe disease outcome. We shall first describe issues related to reports of autoimmune manifestations in COVID-19 patients and subsequently attempt to summarize results of COVID-19 in patients with autoimmune disease. During the pandemic, several autoimmune phenomena have been described to co-occur with or follow COVID-19 and it seems that the inflammatory response is similar in COVID-19 and autoimmunity [7]. In this systematic literature review we analyzed most if not all the reported cases of autoimmune-like manifestations in COVID-19 patients up to September 2020. The results of our research showed a variety of phenomena involving the skin, nervous system, vessels, hematopoietic system and joints. This is relatively not unexpected, considering that viruses are well established triggers of autoimmunity in genetically susceptible individuals. Molecular mimicry, bystander activation and the epitope spreading are well-established proposed mechanisms to explain this link [83]. Moreover, HLA (both class I and class II) and non-HLA polymorphisms are associated with autoimmune diseases and the control of viral infections is largely mediated by the recognition of viral peptides in association with HLA-class I molecules by effector CD8+ T cells [84]. Of note, a recent study identified an association of HLA-DRB1*15:01, HLADQB1*06:02 (MHC-class II) and HLAB*27:07 (MHC-class I) in 99 severe COVID-19 Italian patients [85] and each of these alleles are known to be associated with autoimmunity [86]. Thus, it is possible that COVID-19 patients who express one of these alleles are at increased risk of developing autoimmune-like manifestations.

In light of these considerations, it is likely than the autoimmune manifestations described in COVID-19 represent more the results of the inflammatory cascade and the immune activation triggered by the virus rather than a direct effect of the virus per se. SARS-CoV-2 RNA or proteins have not been detected in the synovia or in the cerebrospinal fluid in COVID-19 patients experiencing arthritis or GBS, however, in chilblain-like lesions immunohistochemical techniques demonstrated the presence of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein in the cytoplasm of cutaneous dermal vessels [87], suggesting a direct role of the virus in conferring damage to the skin and forming skin lesions.

In general, most autoimmune diseases are known to more frequently occur in women compared to men, as estrogens are generally considered as enhancers of immunity while androgens are immunosuppressants, also reflecting the different susceptibility of genders to infections [88]. Our research shows a slightly higher prevalence of hemolytic anemia, immune thrombocytopenia and autoimmune-like skin lesions in women with COVID-19; on the contrary, anti-phospholipid syndrome, Kawasaki-like syndrome and arthritis cases appeared more frequent in men.

Some studies have investigated gender differences in COVID-19. Results of such studies showed that in fact there is no disparity in the prevalence of COVID-19 between men and women, however, male patients have a higher mortality and a more severe disease [89]. The gender-related differences in the spectrum of immune responses might explain both the outcome and the clinical presentation, even in terms of autoimmune-like phenomena.

The different mechanisms by which the virus can induce autoimmunity account for differences in the timing of appearance of clinical manifestation. In fact, some of the clinical manifestations can present at the beginning of the infection [12] and in some cases even in patients with mild COVID-19-related symptoms [33]. Therefore, when evaluating a patient with these manifestations, it is advisable to exclude SARS-CoV-2 positivity. On the other hand, in patients with COVID-19, after weeks from severe infection, seroconversion can induce negative outcomes, as auto-antibodies can be elicited with development of complications, as in some cases of ITP or in the appearance of APLs [35,44].

Another aspect to reflect on is the management of these conditions. Typically, glucocorticoids and immunomodulatory agents represent the gold standard treatment for autoimmune diseases; however, glucocorticoids have been used with caution or completely avoided in COVID-19 patients, as during the first months of the pandemic there were alerts of possible worsening of the viral infection after glucocorticoids, that was the basis for the notes of caution [36]. More recent data, though, support a beneficial role of glucocorticoids, in particular dexamethasone, in the treatment of COVID-19 [90]. We could hypothesize that treating severe cases with glucocorticoids may help reduce the development of autoimmune complications, but a particular attention to the timing of administration has to be considered in order to avoid infection spreading. Infections can trigger autoimmune diseases even after a long latency time, certainly, it would be relevant to investigate whether recovered COVID-19 patients are at greater risk of developing these diseases, indicating that immune dysregulation can be induced even after the infection has resolved.

Patients affected by autoimmune diseases are reasoned to be generally more susceptible to infections, due to the use of the immunosuppressive treatments and particularly when the disease status is not fully under control [91]. In some cases, in fact, these patients can develop disease flares or new autoimmune complications in the context of SARS-CoV-2 infection, as described for patients with pre-existing hemolytic anemia [12], ITP [29,30], and arthritis [71]. It is to be noted that diverse outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with existing autoimmune disease appear in the literature. A possible explanation for these observations relies on the fact that during disease remission these patients have an immune system that is primed to down-regulate the inflammation, while during flares the regulatory mechanisms become dysfunctional enhancing the deleterious effects of the SARS-CoV-2 infection and contributing to the severity of the disease. Since the beginning of the pandemic this subpopulation of patients has been investigated and multiple studies have attempted to assess the risk and outcome of COVID-19 in patients affected by autoimmune diseases [92,93]. On one hand, taking into account the previous considerations, this category of patients should be at higher risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection. On the other hand, they could be protected from a worse disease outcome being under therapy with b-DMARDs or ts-DMARDs, which have been considered useful to treat some features of COVID-19 [94]. According to some data on different cohorts, autoimmune patients do not seem to have an increased risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection compared to the general population and also the disease outcome do not appear to be more severe [95]. In particular, a recently published Italian study investigated the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in a population affected by inflammatory arthritis and treated with immunosuppressant drugs compared with the general population, without finding a higher prevalence of COVID-19 compared to the general population [96]. Similar results also emerged from a study performed in Spain including a cohort of adult and pediatric patients affected by rheumatic diseases [97]. A preliminary study from the Italian Registry of the Italian Society for Rheumatology showed that immunosuppressive treatments were not significantly associated with an increased risk of intensive care unit admission, or mechanical ventilation, or death [98].

Nonetheless, it is currently impossible to draw any conclusion and it is necessary to be cautious until data on larger cohorts of patients will be available. The efforts of the COVID-19 Global Rheumatology Alliance are focusing in this direction [99].

5. Conclusions

SARS-CoV-2 infection shares features with autoimmune diseases, as it can induce clinical manifestations like Guillain-Barré syndrome, arthritis, antiphospholipid syndrome and chilblain-like lesions. Glucocorticoids, high dose intravenous immunoglobulins, cytokine blockers and immunomodulatory drugs seem to play a relevant role in the management of the disease, as it happens in autoimmune disorders. The number of case reports describing autoimmune-like phenomena in COVID-19 is increasing, and these conditions can involve various organs and systems, thus requiring specific knowledge by specialized physicians and a multidisciplinary approach. It is important to raise awareness about possible long-term complications related to the viral infections and thus the follow-up of recovered COVID-19 patients is encouraged.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declarations of interests

None.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Mr. Andrea Pederzani for his precious help and contribution to this research.

References

- 1.Gates B. Responding to covid-19 — a once-in-a-century pandemic? N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:1677–1679. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2003762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y., et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yazdanpanah F., Hamblin M.R., Rezaei N. The immune system and COVID-19: friend or foe? Life Sci. 2020;256 doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117900. 117900-117900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vabret N., Britton G.J., Gruber C., Hegde S., Kim J., Kuksin M., et al. Immunology of COVID-19: current state of the science. Immunity. 2020;52:910–941. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mehta P., McAuley D.F., Brown M., Sanchez E., Tattersall R.S., Manson J.J. COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet. 2020;395:1033–1034. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ceribelli A., Motta F., De Santis M., Ansari A.A., Ridgway W.M., Gershwin M.E., et al. Recommendations for coronavirus infection in rheumatic diseases treated with biologic therapy. J. Autoimmun. 2020;109 doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2020.102442. 102442-102442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodríguez Y., Novelli L., Rojas M., De Santis M., Acosta-Ampudia Y., Monsalve D.M., et al. Autoinflammatory and autoimmune conditions at the crossroad of COVID-19. J. Autoimmun. 2020;114 doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2020.102506. 102506-102506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caso F., Costa L., Ruscitti P., Navarini L., Del Puente A., Giacomelli R., et al. Could Sars-coronavirus-2 trigger autoimmune and/or autoinflammatory mechanisms in genetically predisposed subjects? Autoimmun. Rev. 2020;19 doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102524. 102524-102524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joo Y.B., Lim Y.-H., Kim K.-J., Park K.-S., Park Y.-J. Respiratory viral infections and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2019;21 doi: 10.1186/s13075-019-1977-9. 199-199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G., Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int. J. Surg. 2010;8:336–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liebman H.A., Weitz I.C. Vol. 101. Medical Clinics of North America; 2017. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia; pp. 351–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lopez C., Kim J., Pandey A., Huang T., DeLoughery T.G. Simultaneous onset of COVID-19 and autoimmune haemolytic anaemia. Br. J. Haematol. 2020;190:31–32. doi: 10.1111/bjh.16786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zagorski E., Pawar T., Rahimian S., Forman D. Cold agglutinin autoimmune haemolytic anaemia associated with novel coronavirus (COVID-19) Br. J. Haematol. 2020 doi: 10.1111/bjh.16892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wahlster L., Weichert-Leahey N., Trissal M., Grace R.F., Sankaran V.G. COVID-19 presenting with autoimmune hemolytic anemia in the setting of underlying immune dysregulation. Pediatr. Blood Canc. 2020;67 doi: 10.1002/pbc.28382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Angileri F., Légaré S., Marino Gammazza A., Conway de Macario E., Macario A.J.L., Cappello F. Is molecular mimicry the culprit in the autoimmune haemolytic anaemia affecting patients with COVID-19? Br. J. Haematol. 2020;190:e92–e93. doi: 10.1111/bjh.16883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li M., Nguyen C.B., Yeung Z., Sanchez K., Rosen D., Bushan S. Evans syndrome in a patient with COVID-19. Br. J. Haematol. 2020;190:e59–e61. doi: 10.1111/bjh.16846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vadlamudi G., Hong L., Keerthy M. Evans syndrome associated with pregnancy and COVID-19 infection. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2020;2020 doi: 10.1155/2020/8862545. 8862545-8862545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lazarian G., Quinquenel A., Bellal M., Siavellis J., Jacquy C., Re D., et al. Autoimmune haemolytic anaemia associated with COVID-19 infection. Br. J. Haematol. 2020;190:29–31. doi: 10.1111/bjh.16794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou M., Qi J., Li X., Zhang Z., Yao Y., Wu D., et al. The proportion of patients with thrombocytopenia in three human-susceptible coronavirus infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Haematol. 2020;189:438–441. doi: 10.1111/bjh.16655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang M., Ng M.H.L., Li C.K. Thrombocytopenia in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome (review) Hematology. 2005;10:101–105. doi: 10.1080/10245330400026170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Magdi M., Rahil A. Severe immune thrombocytopenia complicated by intracerebral haemorrhage associated with coronavirus infection: a case report and literature review. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2019;6 doi: 10.12890/2019_001155. 001155-001155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patel P.A., Chandrakasan S., Mickells G.E., Yildirim I., Kao C.M., Bennett C.M. Severe pediatric COVID-19 presenting with respiratory failure and severe thrombocytopenia. Pediatrics. 2020;146 doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsao H.S., Chason H.M., Fearon D.M. Immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) in a pediatric patient positive for SARS-CoV-2. Pediatrics. 2020;146 doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]