Abstract

Prognostication in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is challenging due to heterogeneity in clinical course. We hypothesize that constitutional genetic variation affects disease progression and could aid prognostication. Pooling data from seven studies incorporating 842 cases identifies two genomic locations associated with time from diagnosis to treatment, including 10q26.13 (rs736456, hazard ratio (HR) = 1.78, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.47–2.15; P = 2.71 × 10−9) and 6p (rs3778076, HR = 1.99, 95% CI = 1.55–2.55; P = 5.08 × 10−8), which are particularly powerful prognostic markers in patients with early stage CLL otherwise characterized by low-risk features. Expression quantitative trait loci analysis identifies putative functional genes implicated in modulating B-cell receptor or innate immune responses, key pathways in CLL pathogenesis. In this work we identify rs736456 and rs3778076 as prognostic in CLL, demonstrating that disease progression is determined by constitutional genetic variation as well as known somatic drivers.

Subject terms: Cancer genetics, Cancer genomics, Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, Genetic markers, Prognostic markers

The clinical course of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) is variable and difficult to predict. Here, the authors conduct a genome wide association study meta-analysis for time to first treatment in CLL patients and report two loci associating with progressive disease.

Introduction

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is a prevalent hematological malignancy with approximately 3750 new cases diagnosed in the United Kingdom every year1. CLL is characterized by marked clinical and biological heterogeneity with a proportion of patients having stable, asymptomatic disease which never requires therapeutic intervention, whilst others suffer from a progressive disease with associated shortened survival. Treatment for symptomatic CLL has been transformed by the advent of highly effective chemoimmunotherapy regimens, B-cell receptor signaling pathway inhibitors (BCRi) and agents targeting anti-apoptotic proteins but the majority of patients who progress to the point of therapeutic intervention have historically experienced CLL-related mortality. However the advent of highly effective combination regimens utilizing both BCRi and anti-apoptotic agents may improve patient outcomes2.

Prognostication in early stage CLL and identifying those patients at risk of progression remains challenging. Numerous methods of CLL prognostication exist, which range from clinical assessments to genomic techniques. Clinical assessments include the Rai3 or Binet4 scores, where adverse outcomes are associated with increasing tumor load and evidence of marrow failure, and the CLL international prognostic index (CLL-IPI)5 which utilizes a combination of clinical and biological characteristics to assess prognosis6–9. Cases with unmutated immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region (IGHV) genes10 and those with mutations/deletions affecting TP53, NOTCH1, and SF3B1 have poor prognoses11,12, although these alterations are infrequent in newly diagnosed CLL patients13,14. Once patients progress to symptomatic disease then somatic drivers of disease, particularly mutations of TP53 and SF3B1, as well as complex karyotype, become dominant prognostic markers15,16.

CLL arises from an unidentified cell-of-origin in response to continued signaling through the BCR either in response to ongoing antigenic stimulation by auto-antigens or allo-antigens, or is driven by autonomous BCR activation17. The increased incidence of CLL in first-degree relatives of affected patients also points to an element of genetic susceptibility, which has been borne out in large scale genome-wide association studies (GWAS) which to date have identified over 40 risk alleles18–25. Given the important genetic contribution to CLL susceptibility we hypothesized that constitutional genetic variants also contribute to determining risk of disease progression.

In this work, we conduct a GWAS using data from a large United Kingdom multicentre cohort study of well characterized predominantly early-stage CLL cases to identify two risk alleles for progressive disease in patients with previously untreated disease.

Results

Meta-analysis of CLL genome-wide association studies

We conducted six genome-wide association studies for single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associating with progressive CLL incorporating cases of European ancestry diagnosed at clinical centers across the United Kingdom (Supplementary Fig. 6; Supplementary Table 1). Of these, data on time to first treatment (TTFT) was available for 755 cases. We combined the association test statistic for 5199911 autosomal SNPs common to all 6 GWAS after exclusion of those with an imputation info (imputation quality) score of <0.9 and a minor allele frequency (MAF) of <0.025, and conducted a meta-analysis under a fixed-effects model. Quantile-quantile plots of observed vs. expected P values for SNPs showed minimal inflation of the test statistic (λGC = 1.027) excluding the possibility of hidden population sub-structure or cryptic relatedness (Supplementary Fig. 9).

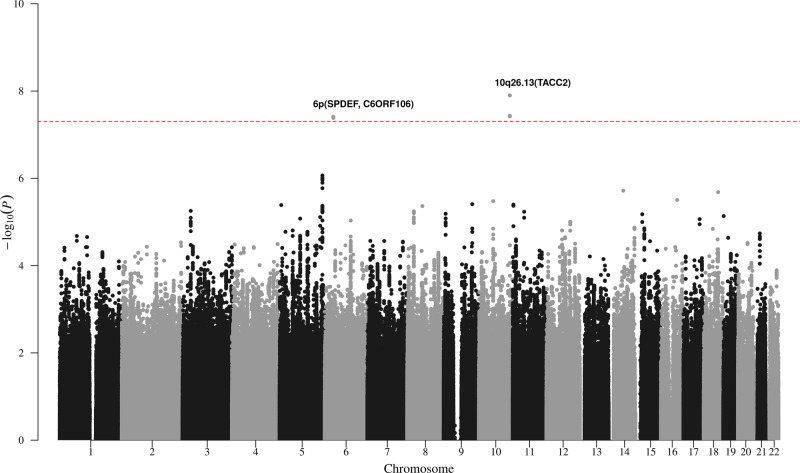

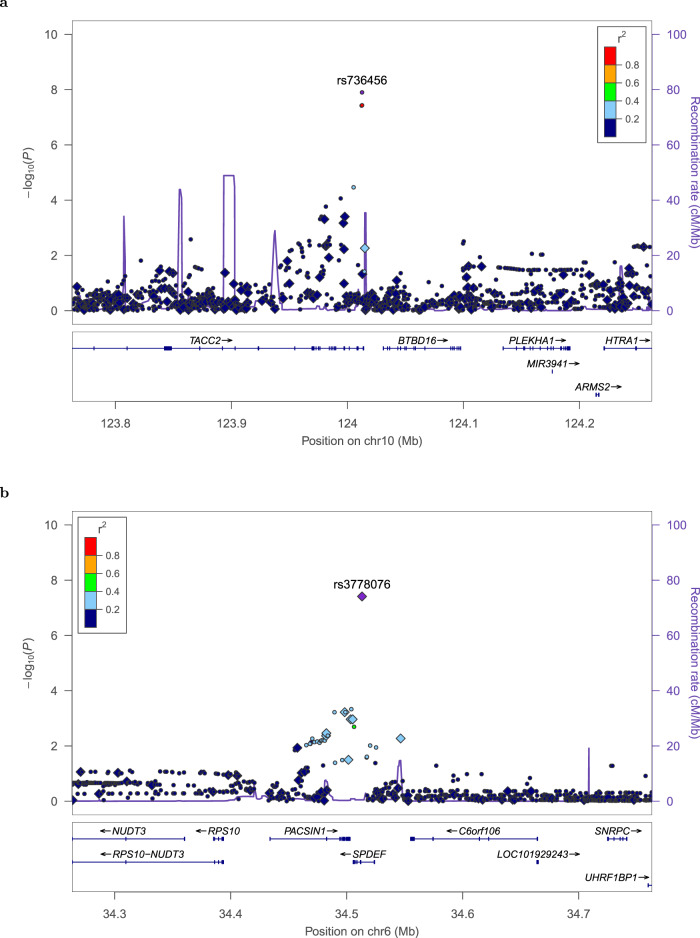

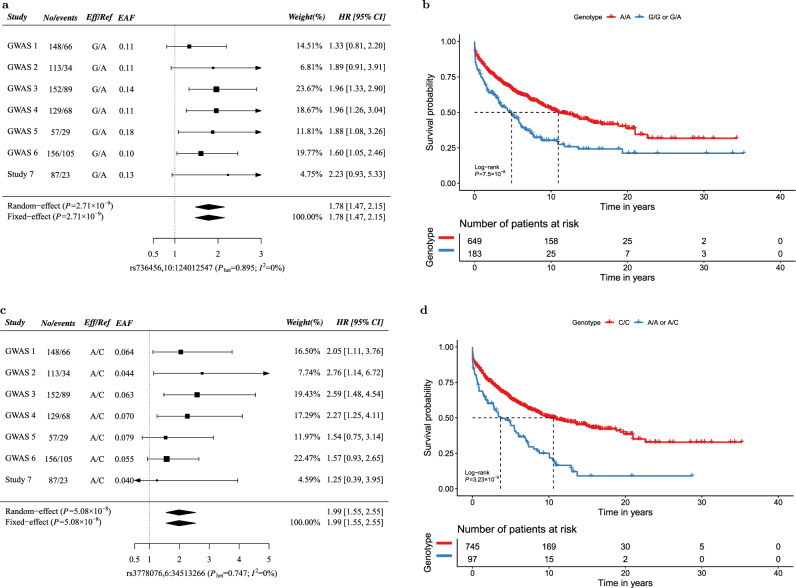

Pooling data from 6 GWAS identified 5 SNPs at two genomic locations that surpassed genome-wide significance (P ≤ 5 × 10−8) for association with time from diagnosis to first treatment (Fig. 1). The strongest statistical evidence for an association with progressive CLL was for rs736456 (hazard ratio (HR) = 1.76, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.45–2.14; P = 1.26 × 10−8), which maps to the TACC2 locus on chromosome 10q26.13 (Fig. 2). The second strongest association with progressive disease was for rs3778076 (HR = 2.03, 95% CI = 1.58–2.62; P = 3.89 × 10−8) which maps to the SPDEF and C6ORF106 (ILRUN) genes on chromosome 6p (Fig. 2). We genotyped rs736456 and rs3778076 in a seventh cohort, bringing the total number of CLL cases analyzed to 842. Both markers showed consistent direction and magnitude of effect sizes across all seven studies with no evidence of heterogeneity (Fig. 3). There was no evidence of significant interaction between rs736456 and rs3778076 (P = 0.131), suggesting that each locus has an independent effect on CLL progression. Analysis conditioning on the lead SNP at each locus showed no evidence for other variants (P < 10−4) associating with progressive disease (Supplementary Fig. 10).

Fig. 1. Manhattan plot from chronic lymphocytic leukemia meta-analysis of 6 genome-wide association studies for variants associating with progressive disease.

Manhattan plot of fixed-effects meta-analysis results for time to first treatment (TTFT). Study-specific single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) effect sizes were combined using the inverse-variance-weighted approach, and nominal meta P values were calculated based on Z-score statistics. The x-axis represents SNP coordinates on autosomal chromosomes and the y-axis shows the fixed-effects meta P values in the −log10 scale. All statistical tests were two-sided and red dashed line indicates significance at genome-wide level (P ≤ 5 × 10−8). Risk loci for progressive CLL are annotated with chromosome position and local genes.

Fig. 2. Regional association and linkage disequilibrium plots for loci associated with progressive CLL.

Regional plots of time to first time treatment (TTFT) survival associations for rs736456 (a) and rs3778076 (b) reaching genome-wide significance (P ≤ 5 × 10−8). Study-specific single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) effects were combined in a fixed effect model using an inverse-variance-weighted method. Nominal meta-analysis P values were calculated based on Z-score statistics and all statistical tests were two-sided. Plots show SNP coordinates based on genomic build b37/hg19 on the x-axis, and −log10 (P values) on the y-axis. Genotyped and imputed SNPs are represented by diamonds and circles, respectively, and are colored according to their linkage disequilibrium (pairwise r2) with the lead SNP based on the 1000 Genomes European panel. Reference genes in the region are shown in the lower panel, with arrows indicating transcript direction, dense blocks representing exons and horizontal lines representing introns. Two additional SNPs at 10q26.13 (rs4752676 and rs736457) (a) and one additional SNP at 6p (rs11757517) (b) also reach genome-wide significance in meta-analysis (Supplementary Figs. 60–62). The symbol for rs11757517 is obscured on the regional plot (b) by the symbol for rs3778076.

Fig. 3. Forest plots and survival curves for loci associated with progressive CLL.

Panels a and c show forest plots for rs736456 (a) and rs3778076 (c) for the association with time to first treatment (TTFT) by GWAS. No/events: Number of CLL patients/Number of patients receiving treatment; Eff/Ref: effect/reference allele; EAF: effect allele frequency; HR: hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval; For each study, allelic dosage was estimated for SNP and included in a Cox proportional hazard model to estimate HR and 95% CI. Wald-type CIs based on the standard normal distribution were reported here. Squares denote the per-allele HR, with size proportional to the weight of the study. Pooled HRs derived from both the fixed and random-effects models are indicated by diamonds with their corresponding meta P values from Wald tests shown in the left parentheses. X-axis label formats include reference sequence (rs) identifier and chromosome:position (b37). P values for Cochran’s Q test (Phet) and I2 for heterogeneity are shown in parentheses. Panels b and d show Kaplan–Meier survival plots for TTFT in CLL patients stratified by rs736456 (b) and rs3778076 (d). TTFT is defined as the time from diagnosis of CLL to treatment or last follow-up without treatment. The number of patients in each group at each timepoint are indicated in the table. Nominal P values from log-rank tests are shown. All statistical tests were two-sided.

Neither the lead SNP on chromosome 10 nor chromosome 6 were significantly associated with post-treatment survival (rs736456 (chr. 10), HR 1.03, 95% CI 0.79–1.35, P = 0.801; rs3778076 (chr. 6), HR 0.99, 95% CI 0.70–1.42) (Supplementary Fig. 11).

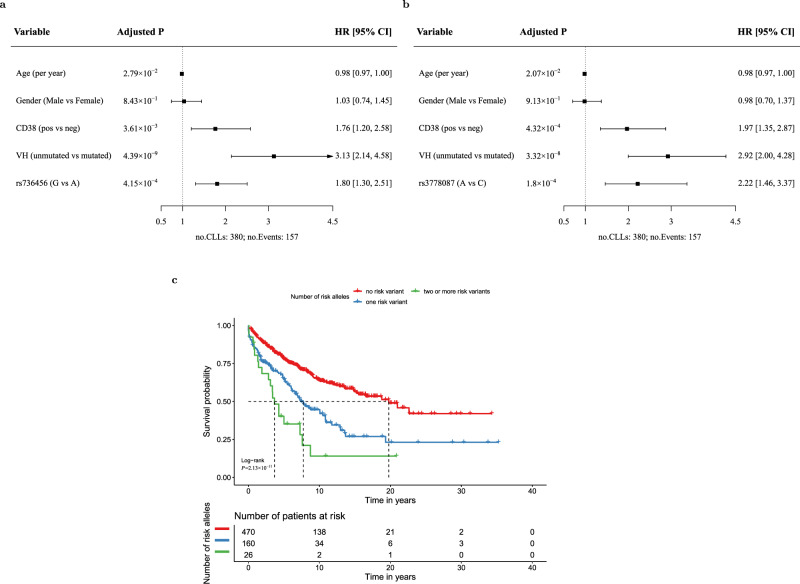

rs736456 and rs3778076 predict disease progression in early stage CLL

In order to further investigate the associations with progressive disease we stratified patients by disease stage at presentation and established prognostic markers. rs736456 (chromosome 10) and rs3778076 (chromosome 6) significantly associate with disease progression in patients with Binet stage A disease at presentation, but have limited prognostic impact in patients with Binet stage B and C at presentation (Supplementary Fig. 12) (P = 3.81 × 10−5 in Binet A and P = 0.12 in Binet B/C for rs736456 carriers vs. non-carriers; P = 1.93 × 10−9 in Binet A and P = 0.69 in Binet B/C for rs3778076 carriers vs. non-carriers), consistent with a specific role in driving progression in early stage disease. Both genetic markers retained significance in multivariate models for disease progression restricted to Binet stage A patients and when adjusted for study in the model (Fig. 4). rs736456 and rs3778076 were particularly powerful markers for disease progression in stage A patients when considered together, where carriers of 1 risk allele (P = 1.4 × 10−7) or 2 or more risk alleles (P = 7.9 × 10−8) have a significantly shorter time to first treatment compared to non-carriers (Fig. 4c). Whilst not as powerful as IGHV status, rs736456 and rs3778076 had prognostic utility approximately equivalent to CD38 status. Moreover, rs736456 and rs3778076 both significantly associate with progressive disease in patients with otherwise low risk clinical markers, including IGHV mutation (Supplementary Fig. 13), CD38 negativity (Supplementary Fig. 14), low β2 microblobulin (Supplementary Fig. 15) and wild-type for TP53 (Supplementary Fig. 16). As such, rs736456 and rs3778076 are particularly powerful prognostic markers in analysis restricted to patients with disease that is Binet stage A, IGHV mutated and CD38 negative (Supplementary Fig. 17). Taken together, these data identify rs736456 and rs3778076 as prognostic for disease progression in patients with otherwise low risk markers, but which have limited prognostic power in patients with high-risk markers or late stage disease.

Fig. 4. Multivariate prognostication models for time to first treatment (TTFT) and survival curves in Binet stage A CLL.

Study-stratified multivariable Cox proportional hazard model for TTFT in Binet A CLL patients incorporating rs736456 (a) and rs3778076 (b). Age at diagnosis (continuous), gender (binary), CD38 (binary), VH (binary) and SNP allelic dosage for the effect allele (continuous) were included together in a study-stratified Cox proportional hazard model to estimate Hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). CI and nominal P values from Wald tests based on the standard normal distribution were reported here. Cases with missing data for any of the variables were excluded from multivariate models. c Kaplan–Meier survival plot for TTFT by number of cumulative risk alleles (0, 1, >1) for rs3778076 and rs736456 in Binet A CLL patients. TTFT is defined as the time from diagnosis of CLL to treatment or last follow-up without treatment. The number of patients in each group at each timepoint are indicated in the table. Nominal P value from the log-rank test is shown. All statistical tests were two-sided.

Progressive disease loci at chromosomes 10 and 6

To identify cis-regulated genes at each locus associated with progressive disease we interrogated gene expression data derived from a meta-analysis of 31624 blood samples collated by the eQTLGen consortium26. Thirteen genes were annotated to within 1 Mb of the chromosome 10 association signal and rs736456 is eQTL for the PLEKHA1 gene (pleckstrin homology domain-containing family A; TAPP-1) (Benjamini-Hochberg corrected P-value [PBH] = 1.29 × 10−15) (Supplementary Table 2). Of the 27 genes annotated to within 1 Mb of the chromosome 6 signal, rs3778076 is eQTL for 5 genes including most significantly UHRF1BP1 (Ubiquitin-Like Containing PHD And RING Finger Domains 1-Binding Protein 1) (PBH = 6.73 × 10−139) and ILRUN (Inflammation And Lipid Regulator With UBA-Like And NBR1-Like Domains; C6ORF106) (PBH = 3.54 × 10−64)(Supplementary Table 3).

Shared risk alleles for CLL etiology and progressive disease

rs3778076 maps close (103 kb) to an established CLL etiological risk variant on chromosome 6q21 (rs3800461)20 and the two variants are in linkage disequilibrium (r2 0.46, D’ 0.91) suggesting they might drive initial CLL development and subsequent progression to symptomatic disease via a common mechanism. Consistent with this hypothesis, rs3800461 is also an eQTL for UHRF1BP1 and ILRUN (C6ORF106) (Supplementary Table 4), although we cannot exclude these variants operating through independent mechanisms. Of other CLL risk variants identified via large scale GWAS18–25, data on 5 variants did not pass quality control in our study (rs9815073, rs6858698, rs10069690, rs7944004, rs71597109) and none of the others were significantly (P < 10−3) associated with progressive disease (Supplementary Figs. 18–59).

Discussion

CLL susceptibility loci identified to date implicate genes central to B-cell development, BCR signaling and apoptotic responses20. These risk alleles may therefore function by promoting the generation of abnormal pro-B populations or to maintain the outgrowth of CLL-precursors in response to continuous BCR signaling. However, the current model would suggest that once the pre-leukemic CLL clone has established, disease progression becomes largely dependent on the classic multi-hit model of oncogenesis where acquired somatic drivers promote clonal expansion11, thus temporally limiting the impact of constitutional genetic variants to disease progression at an early stage.

The evidence presented herein suggests that, in addition to being etiological, constitutional risk alleles contribute to disease progression in CLL post-diagnosis. Our data suggest that rs736456 and rs3778076 are powerful prognostic markers in early stage CLL, but have less impact as disease progresses, predicted to be due to the acquisition of strongly prognostic somatic alterations which then dominate. Consistent with this model, the prognostic power of rs3778076 and rs735456 is weaker in patients with Binet stage B or C disease and in patients with high risk somatic markers, such as unmutated IGHV or CD38 positivity.

The progressive disease allele at chromosome 10 (rs736456) is associated with increased expression of PLEKHA1 (pleckstrin homology domain containing A1; TAPP1) whilst the allele at chromosome 6 (rs3778076) is associated with increased expression of ILRUN (Inflammation And Lipid Regulator With UBA-Like And NBR1-Like Domains; C6ORF106) and UHRF1BP1 (UHRF binding protein 1). PLEKHA1, a plekstrin homology (PH) adapter protein is a target for phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase (PI3K) signaling and a partner for phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) which regulates the assembly of signaling complexes at the cell membrane27. PI3K-mediated signaling is a key element of BCR-mediated signal transduction, a receptor with a central, etiological role in CLL pathogenesis28. Herold and colleagues identified and validated an 8-gene expression signature including PLEKHA1 that predicted time to first treatment in CLL29. Furthermore, the PLEKHA1 homologous protein TAPP2 is differentially expressed in CLL, with increased expression in ZAP70 positive/IGHV unmutated CLL, a subtype associated with enhanced signaling via the BCR with associated pro-survival effects on cultured CLL-cells30,31.

ILRUN (C6ORF106) regulates interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) signaling which modulates cellular responses to viral antigens. Given that CLL may arise in response to chronic stimulation of the BCR by viral antigens, constitutional regulation of an IRF3-dependent response may therefore affect the expansion of CLL-clones32. IRF3 also regulates expression of miR-15533,34 which is thought to be etiological in a subset of patients33,35 and also associates with unmutated IGHV and aggressive disease in CLL36–40.

UHRF1BP1 has been identified as a susceptibility gene for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)41 with differential methylation affecting regulation of this gene42, however UHRF1BP1 has not previously been associated with B-cell tumors. An etiological CLL GWAS identified susceptibility variants mapping to within the B-cell scaffold protein with ankyrin repeats 1 (BANK1) gene20. BANK1 is an adapter for BCR signals, modulates CD40 receptor-mediated signaling responses and has also been implicated in SLE and other inflammatory arthropathies43–45. Therefore, the association of both UHRF1BP1 and BANK1 with CLL and SLE could imply common etiological factors between the two diseases. Given that both CLL and SLE are considered to arise, in part, due to a loss of immunological tolerance to self-antigens or auto-antigens this may provide further indirect evidence for auto-antigenic drive in the etiology of CLL.

Collectively the risk alleles identified herein map to genes known to be regulatory for B-cell development and the control of autoimmunity supporting the concept that either aberrant BCR signals and/or a breakdown in normal immunological tolerance contributes to CLL clonal expansion and the subsequent acquisition of somatic driver mutations.

Many patients with Binet stage A CLL never progress to the point of therapeutic intervention and the accurate identification of patients in this group has been the subject of intensive investigation. Multiple prognostic features and tests have been described to identify those with a low risk of progressive disease. Conversely, the identification of high-risk prognostic features in stage A CLL patients has been used to define a group likely to need close surveillance as opposed to community monitoring programmes. The failure, to date, to demonstrate a survival benefit for early treatment of high-risk asymptomatic patients is due to an inability to successfully identify an appropriate high-risk group and also the limits of pre-emptive chemotherapy-based approaches46. However, with the advent of highly-effective targeted therapies such as BCRi pre-emptive therapy in high-risk CLL patients is again under investigation47.

Genetic tests for constitutional genetic markers, such as rs736456 and rs3778076, have the advantage of being easy to perform, highly reproducible and inexpensive making them ideal for incorporation into multivariate prognostication models for disease progression in early stage CLL.

Methods

Patients and ethics

CLL patients were diagnosed at clinical centers in the United Kingdom, including Bournemouth (Royal Bournemouth Hospital, GWAS 1), Cardiff (University Hospital of Wales, GWAS 2), Hull (Hull University Teaching Hospital NHS Trust, GWAS 3 and GWAS 4, study 7), Newcastle (Royal Victoria Infirmary, GWAS 5) and Gateshead/Sunderland (Queen Elisabeth Hospital/City Hospitals Sunderland NHS Trust, GWAS 6). Collection of patient samples and associated clinico-pathological information was undertaken with written informed consent. All studies were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and received local institutional review board and/or research ethics approval (Hull 08/H1304/35; Cardiff 02/4806). Newcastle, Gateshead, and Sunderland CLL patient samples were collected and stored following approval from the Newcastle Academic Health Partners Biobank (http://www.ncl.ac.uk/biobanks/collections/nbrtb/).

CLL diagnosis, CD38/IGHV analysis

All patients had typical CLL with an absolute B cell count >5 × 109 L−1 expressing CD5, CD23, CD19 and were diagnosed in accordance with World Health Organisation guidelines48 contemporaneous to the time of diagnosis. Cases were recruited to each study in the following time periods: GWAS1 (1970–2005), GWAS2 (1979–2009), GWAS3 (1970–2009), GWAS4 (1997–2013), GWAS5 (1972–2002), GWAS6 (1969–2015), study 7 (1997–2017). IGHV gene sequences were analyzed using IgBlast (v1.3.0) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/igblast/) and those with at least 98% homology to germline were regarded as unmutated10. CD38 expression was determined at each individual clinical center via flow cytometric analysis of diagnostic samples and a cut-off of 30% was used for positivity49. Serum β2 microblobulin was performed by referring centers using locally established and validated immunoassays. Assessment of deletion 17p and TP53 mutation analysis was in line with ERIC recommendations on TP53 mutation analysis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia50.

Treatment was initiated in response to standard indications51. Given the historic nature of the treated cohorts in this study the treatment regimens employed were predominantly chemotherapeutic (chlorambucil monotherapy, fludarabine monotherapy, fludarabine, and cyclophosphamide) or chemoimmunotherapeutic (chemotherapy in combination with a CD20 monoclonal antibody). A minority of patients were treated with other regimens including radiotherapy, alemtuzumab, ibrutinib or ibrutinib in combination with venetoclax.

Unmutated IGHV, CD38-positivity, Binet stage B or C, serum β2 microblobulin >3.5 mg L−1 and deletion/mutation of TP53 at presentation were all significantly associated with shorter time to first treatment (TTFT) in univariate analysis (Supplementary Figs. 1–5; P < 0.05), confirming that established prognostic markers predict disease progression in patients recruited to this study.

Genotyping and quality control procedures

DNA was extracted from peripheral blood and genotyped on Illumina OmniExpress arrays (8v1, 8v1-2, or 8v1.3). Genotypes were determined using Illumina GenomeStudio software (v2.0) (Illumina) with 922269 SNPs common to all three arrays (Supplementary Fig. 6). Quality control and data analysis were performed using R v3.5.1 and PLINK v1.9b4.4 (Supplementary Fig. 6). Given that CLL cases were genotyped using DNA extracted from tissue samples that include leukemic B cells we applied rigorous quality control to remove variants potentially affected by somatic copy number alterations. For each GWAS we excluded markers with departure from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE; P ≤ 10−3), a call rate <95% or with significant differences in minor allele frequency (P ≤ 10−3) between genotype batches. Data from all six GWAS were combined for sample quality control processing. Samples were excluded if the call rate was < 95%, heterozygosity exceeded 3 standard deviations from the overall mean heterozygosity or were identified as non-European based on principal components analysis using 1000 genome data as a reference (Supplementary Fig. 7). Samples were also removed such that there were no two individuals with estimated relatedness pihat ≥0.1875, with retention of the sample with the higher call rate. As an additional control check to ensure that the constitutional variants reported here are not located within recurrent regions of somatic copy number change we used Nexus Copy Number software 10 (build version 9665) (BioDiscovery, California) to interrogate B allele frequency and Log R ratio at variant positions.

Following the exclusion of poor quality markers and samples, haplotypes were estimated from genotypes using ShapeIT (v2.r790)52 and genome-wide imputation was performed using the Michigan Imputation Server (https://imputationserver.sph.umich.edu/index.html) and the Haplotype Reference Consortium reference haplotype panel (http://www.haplotype-reference-consortium.org/). All variants with an imputation info score <0.9 were excluded from subsequent analysis.

Genome-wide analysis for markers that predict time to first treatment

The primary outcome assessed in this study was time to first treatment (TTFT), defined as the interval between CLL diagnosis and date of first treatment or last follow-up. For each study, allelic dosage was estimated for the minor allele at each variant position and included in a cox proportional hazard model to estimate hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). Variants were included in the meta-analysis if they had results from all six studies. Study-specific single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) effects were combined using an inverse-variance-weighted method (fixed effects model) and the DerSimonian–Laird approach (random effects model) using R metafor package (v2.4-0)53. SNPs with fixed-effect P values of ≤5 × 10−8 were deemed significant at genome-wide level. Cochran’s Q test and I2 were used to assess the heterogeneity across studies. Regional plots were generated using LocusZoom (V1.4) downloaded from https://github.com/statgen/locuszoom-standalone.

To test for secondary signals in regions achieving genome-wide significance we carried out conditional analysis on the index SNP by study and then combined individual conditional effect sizes from 6 studies under a fixed effects model. SNPs with a conditional meta P value <10−4 were considered independent of the index SNP.

Heterogeneity of Kaplan-Meier survival curves was assessed by the log-rank test, including tests for established prognostic markers, the most likely index SNP genotypes (for genotypes with posterior probabilities >0.9), combined groups of established prognostic markers/SNPs and combined SNP genotypes. For joint analyses, pairwise log-rank tests, with false discovery rate (FDR) corrections for multiple testing, were used to test for significant differences between survival curves.

Study-stratified multivariate Cox proportional hazard models incorporating established prognostic markers including IGHV and CD38 status were used to determine the impact of variants on disease progression. Cases with missing data for any of the variables were excluded from multivariate models.

A secondary outcome was post-treatment survival, defined as the interval between first treatment for CLL-related symptoms and death or last follow-up. Data on post-treatment survival were available on 390 CLL cases from six studies (GWAS1-6), with 231 deaths and 159 censored at last follow-up.

Technical validation of variants associating with progressive CLL

rs3778076 was directly genotyped in all six GWAS and rs736456 was imputed to high quality in all six GWAS (info score 0.974–0.985). Fidelity of array genotyping and imputed dosages was confirmed using Sanger sequencing in a subset of samples for each sentinel variant with concordance of 100% for all variants (Supplementary Fig. 8). rs3778076 and rs736456 were directly genotyped in study 7 using Sanger sequencing.

Expression quantitative trait loci analysis

To identify cis expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs) we made use of summary data from the eQTLGen Consortium for whole blood, which incorporates 37 independent datasets derived from a total of 31684 individuals (http://www.eqtlgen.org/cis-eqtls.html)26. Benjamini-Hochberg (BH)-adjusted P values were estimated for each gene annotated to within 1 Mb of rs736456 on 10q26.13 and rs3778076 on 6p.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by Blood Cancer UK (formely Bloodwise) (#06002 and #13044 to J.M.A.). J.M.A. is recipient of an Oncology/Haematology Fellowship from Gilead Pharmaceuticals and C.E. received funding from JGW Patterson Foundation. This work was supported by Cancer Research UK (C2115/A21421). E.W. and G.S. received funding from Blood Cancer UK (#14024). A.S. was partly funded by the National Institute for Health Research Oxford Biomedical Research Centre; the views and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the National Institute for Health Research, the UK National Health Service, the UK Department of Health or the Universities of Oxford. We are grateful for the support of the Clinical Trials Research Unit at The University of Leeds and the Hull York Medical School, University of Hull for funding the Daisy Tumour Bank.

Source data

Author contributions

W.-Y.L. collated data, conducted data analysis and drafted the manuscript. S.E.F., N.S., C.E., T.R., E.W., C.S., G. Strathdee, T.M.-F., R.P., H.Mearns, T.B., R.S.H., H.Marr, J.W., G.Summerfield, S.M., A.P., C.P., C.F., F.F., M.J.S.D., S.J., A.Sellors, A.Schuh, P.R., D.O., J.B., S.R., A.B., L.C., P.E., P.H., and G.P. generated/collated data and/or advised on data a nalysis. J.M.A. and D.J.A. designed the project, generated data, analyzed data, directed the research and drafted the manuscript. J.M.A. also obtained funding. All authors contributed to the final version of the manuscript.

Data availability

Genome-wide association summary statistics (Lin_TTFT_CLLmetaAssoc.txt) are available for download from 10.25405/data.ncl.12136365. eQTL data is available from the eQTLGen consortium via http://www.eqtlgen.org/cis-eqtls.html (2019-12-11-cis-eQTLsFDR-ProbeLevel-CohortInfoRemoved-BonferroniAdded.txt.gz). The remaining data are contained within the supplementary information files or available from the authors upon reasonable request. Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Stephen J. Chanock and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: David J. Allsup, James M. Allan.

Contributor Information

David J. Allsup, Email: hycda1@hyms.ac.uk

James M. Allan, Email: james.allan@newcastle.ac.uk

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-020-20822-9.

References

- 1.HMRN. Haematological Malignancy Research Network. https://www.hmrn.org/ (2018).

- 2.Hillmen, P. et al. Ibrutinib plus venetoclax in relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia: the CLARITY study. J. Clin. Oncol. JCO1900894, 10.1200/JCO.19.00894 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Rai KR, et al. Clinical staging of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 1975;46:219–234. doi: 10.1182/blood.V46.2.219.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Binet JL, et al. A new prognostic classification of chronic lymphocytic leukemia derived from a multivariate survival analysis. Cancer. 1981;48:198–206. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19810701)48:1<198::AID-CNCR2820480131>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.International CLLIPIWG. An international prognostic index for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL-IPI): a meta-analysis of individual patient data. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:779–790. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30029-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin K, et al. Relationship between p53 dysfunction, CD38 expression, and IgV(H) mutation in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2002;100:1404–1409. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-11-0066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crespo M, et al. ZAP-70 expression as a surrogate for immunoglobulin-variable-region mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:1764–1775. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa023143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bulian P, et al. CD49d is the strongest flow cytometry-based predictor of overall survival in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014;32:897–904. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.50.8515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dohner H, et al. Genomic aberrations and survival in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000;343:1910–1916. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200012283432602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamblin TJ, Davis Z, Gardiner A, Oscier DG, Stevenson FK. Unmutated Ig V(H) genes are associated with a more aggressive form of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 1999;94:1848–1854. doi: 10.1182/blood.V94.6.1848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Landau DA, et al. Mutations driving CLL and their evolution in progression and relapse. Nature. 2015;526:525–530. doi: 10.1038/nature15395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zenz T, et al. TP53 mutation and survival in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010;28:4473–4479. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.8762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zainuddin N, et al. TP53 Mutations are infrequent in newly diagnosed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk. Res. 2011;35:272–274. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2010.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gunnarsson R, et al. Large but not small copy-number alterations correlate to high-risk genomic aberrations and survival in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a high-resolution genomic screening of newly diagnosed patients. Leukemia. 2010;24:211–215. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stilgenbauer S, et al. Gene mutations and treatment outcome in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: results from the CLL8 trial. Blood. 2014;123:3247–3254. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-01-546150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herling CD, et al. Complex karyotypes and KRAS and POT1 mutations impact outcome in CLL after chlorambucil-based chemotherapy or chemoimmunotherapy. Blood. 2016;128:395–404. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-01-691550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burger JA, Chiorazzi N. B cell receptor signaling in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Trends Immunol. 2013;34:592–601. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crowther-Swanepoel D, et al. Common variants at 2q37.3, 8q24.21, 15q21.3 and 16q24.1 influence chronic lymphocytic leukemia risk. Nat. Genet. 2010;42:132–136. doi: 10.1038/ng.510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Speedy HE, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies multiple susceptibility loci for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Nat. Genet. 2014;46:56–60. doi: 10.1038/ng.2843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Law PJ, et al. Genome-wide association analysis implicates dysregulation of immunity genes in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:14175. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berndt SI, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies multiple risk loci for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:868–876. doi: 10.1038/ng.2652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Di Bernardo MC, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies six susceptibility loci for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:1204–1210. doi: 10.1038/ng.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berndt SI, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies discovers multiple loci for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:10933. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Slager SL, et al. Common variation at 6p21.31 (BAK1) influences the risk of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2012;120:843–846. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-03-413591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Slager SL, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies a novel susceptibility locus at 6p21.3 among familial CLL. Blood. 2011;117:1911–1916. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-09-308205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Võsa, U. et al. Unraveling the polygenic architecture of complex traits using blood eQTL meta-analysis. Preprint at bioRxiv 10.1101/447367 (2018).

- 27.Marshall AJ, Krahn AK, Ma K, Duronio V, Hou S. TAPP1 and TAPP2 are targets of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling in B cells: sustained plasma membrane recruitment triggered by the B-cell antigen receptor. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002;22:5479–5491. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.15.5479-5491.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoellenriegel J, et al. The phosphoinositide 3′-kinase delta inhibitor, CAL-101, inhibits B-cell receptor signaling and chemokine networks in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2011;118:3603–3612. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-05-352492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Herold T, et al. An eight-gene expression signature for the prediction of survival and time to treatment in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 2011;25:1639–1645. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Costantini JL, et al. TAPP2 links phosphoinositide 3-kinase signaling to B-cell adhesion through interaction with the cytoskeletal protein utrophin: expression of a novel cell adhesion-promoting complex in B-cell leukemia. Blood. 2009;114:4703–4712. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-213058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Allsup DJ, et al. B-cell receptor translocation to lipid rafts and associated signaling differ between prognostically important subgroups of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7328–7337. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kostareli E, et al. Molecular evidence for EBV and CMV persistence in a subset of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia expressing stereotyped IGHV4-34 B-cell receptors. Leukemia. 2009;23:919–924. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tarassishin L, et al. Interferon regulatory factor 3 inhibits astrocyte inflammatory gene expression through suppression of the proinflammatory miR-155 and miR-155*. Glia. 2011;59:1911–1922. doi: 10.1002/glia.21233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tian WL, et al. IRF3 is involved in human acute myeloid leukemia through regulating the expression of miR-155. Biochem Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016;478:1130–1135. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.08.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marton S, et al. Small RNAs analysis in CLL reveals a deregulation of miRNA expression and novel miRNA candidates of putative relevance in CLL pathogenesis. Leukemia. 2008;22:330–338. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2405022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cui B, et al. MicroRNA-155 influences B-cell receptor signaling and associates with aggressive disease in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2014;124:546–554. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-03-559690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vargova K, et al. MiR-155/miR-150 network regulates progression through the disease phases of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood Cancer J. 2017;7:e585. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2017.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guinn D, et al. miR-155 expression is associated with chemoimmunotherapy outcome and is modulated by Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibition with Ibrutinib. Leukemia. 2015;29:1210–1213. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ferrajoli A, et al. Prognostic value of miR-155 in individuals with monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis and patients with B chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2013;122:1891–1899. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-01-478222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Calin GA, et al. A MicroRNA signature associated with prognosis and progression in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;353:1793–1801. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gateva V, et al. A large-scale replication study identifies TNIP1, PRDM1, JAZF1, UHRF1BP1 and IL10 as risk loci for systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat. Genet. 2009;41:1228–1233. doi: 10.1038/ng.468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Imgenberg-Kreuz J, et al. DNA methylation mapping identifies gene regulatory effects in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2018;77:736–743. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aiba Y, et al. BANK negatively regulates Akt activation and subsequent B cell responses. Immunity. 2006;24:259–268. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kozyrev SV, et al. Functional variants in the B-cell gene BANK1 are associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:211. doi: 10.1038/ng.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Genin E, et al. Epistatic interaction between BANK1 and BLK in rheumatoid arthritis: results from a large trans-ethnic meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e61044. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cymbalista F, et al. Early versus deferred treatment with combined fludarabine, cyclophosphamide and rituximab (fcr) improves event-free survival in patients with high-risk binet stage a chronic lymphocytic leukemia–first results of a randomized German-French cooperative Phase III Trial. Blood. 2013;122:524–524. doi: 10.1182/blood.V122.21.524.524. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Langerbeins P, et al. The CLL12 trial protocol: a placebo-controlled double-blind Phase III study of ibrutinib in the treatment of early-stage chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients with risk of early disease progression. Future Oncol. 2015;11:1895–1903. doi: 10.2217/fon.15.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Swerdlow S. H., et al. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Vol. 2 (ed. Swerdlow S. H.) Ch. 13, 216 (International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2017).

- 49.Matrai Z, et al. CD38 expression and Ig VH gene mutation in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2001;97:1902–1903. doi: 10.1182/blood.V97.6.1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pospisilova S, et al. ERIC recommendations on TP53 mutation analysis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 2012;26:1458–1461. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hallek M, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a report from the International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia updating the National Cancer Institute-Working Group 1996 guidelines. Blood. 2008;111:5446–5456. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-093906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Delaneau O, Marchini J, Zagury JF. A linear complexity phasing method for thousands of genomes. Nat. Methods. 2011;9:179–181. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Viechtbauer W. Conducting Meta-Analyses in R with the metafor Package. J. Statist. 2010;36:48. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Genome-wide association summary statistics (Lin_TTFT_CLLmetaAssoc.txt) are available for download from 10.25405/data.ncl.12136365. eQTL data is available from the eQTLGen consortium via http://www.eqtlgen.org/cis-eqtls.html (2019-12-11-cis-eQTLsFDR-ProbeLevel-CohortInfoRemoved-BonferroniAdded.txt.gz). The remaining data are contained within the supplementary information files or available from the authors upon reasonable request. Source data are provided with this paper.