Abstract

Background

Pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) has been proposed as an effective method for many respiratory diseases. However, the effects of exercise-based PR on asthma are currently inconclusive. This review aimed to investigate the effects of exercise-based PR on adults with asthma.

Methods

The PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, International Clinical Trials Registry Platform and ClinicalTrials.gov databases were searched from inception to 31 July 2019 without language restriction. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) investigating the effects of exercise-based PR on adults with asthma were included. Study selection, data extraction and risk of bias assessment were performed by two investigators independently. Meta-analysis was conducted by RevMan software (version 5.3). Evidence quality was rated by the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system.

Results

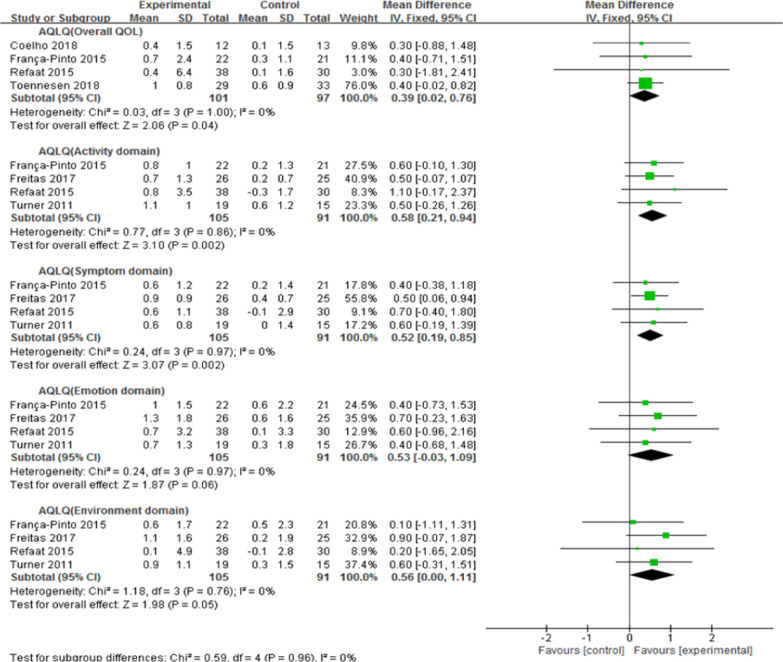

Ten literatures from nine studies (n = 418 patients) were identified. Asthma quality of life questionnaire total scores (MD = 0.39, 95% CI: 0.02 to 0.76) improved significantly in the experimental group compared to control group, including activity domain scores (MD = 0.58, 95% CI: 0.21 to 0.94), symptom domain scores (MD = 0.52, 95% CI: 0.19 to 0.85), emotion domain scores (MD = 0.53, 95% CI: − 0.03 to 1.09) and environment domain scores (MD = 0.56, 95% CI: 0.00 to 1.11). Both the 6-min walk distance (MD = 34.09, 95% CI: 2.51 to 65.66) and maximum oxygen uptake (MD = 4.45, 95% CI: 3.32 to 5.58) significantly improved. However, improvements in asthma control questionnaire scores (MD = − 0.25, 95% CI: − 0.51 to 0.02) and asthma symptom-free days (MD = 3.35, 95% CI: − 0.21 to 6.90) were not significant. Moreover, there was no significant improvement (MD = 0.10, 95% CI: − 0.08 to 0.29) in forced expiratory volume in 1 s. Nonetheless, improvements in forced vital capacity (MD = 0.23, 95% CI: 0.08 to 0.38) and peak expiratory flow (MD = 0.39, 95% CI: 0.21 to 0.57) were significant.

Conclusions

Exercise-based PR may improve quality of life, exercise tolerance and some aspects of pulmonary function in adults with asthma and can be considered a supplementary therapy. RCTs of high quality and large sample sizes are required.

Clinical trial registration: The review was registered with PROSPERO (The website is https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/, and the ID is CRD42019147107).

Keywords: Pulmonary rehabilitation, Asthma, Systematic review, Meta-analysis

Background

Asthma, characterized by variable symptoms of wheezing, shortness of breath, chest tightness and/or cough, and variable expiratory airflow limitation, affects 1–18% of the population in different countries [1]. From 1990 to 2015, the prevalence of asthma increased by 12.6%, to 358.2 million individuals, according to the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors (GBD) 2015 study [2]. In China, the overall prevalence of asthma in 50,991 participants was found to be 4.2%, representing 45.7 million Chinese adults [3]. Patients who experience asthma often have impaired quality of life (QOL), low pulmonary function, descending exercise tolerance and poor symptom control, which may be life-threatening and carry a significant burden for society. While medication is the main approach to asthma, non-pharmacological strategies can be used as supplements. Asthma patients, especially those with one or more risk factors for exacerbations, should consider non-pharmacological strategies and interventions to assist with symptom control and risk reduction.

Pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) is an evidence-based, multidisciplinary, and comprehensive intervention that was designed to improve the physical and psychological condition of patients with chronic respiratory disease [4, 5]. PR includes but is not limited to exercise training, education, and behaviour change [4, 5]. Exercise training is an important part of PR and involves endurance training, interval training, resistance/strength training, and flexibility training, among others. It has been reported to improve asthma symptoms, QOL, exercise capacity, bronchial hyperresponsiveness, exercise-induced bronchoconstriction and cardiopulmonary fitness and to reduce airway inflammation and nocturnal symptoms in patients with asthma [6–12]. However, these studies included both adults and children or focused on airway inflammation alone; furthermore, they are outdated. This meta-analysis aimed to evaluate the effects of exercise-based PR compared to other treatments (standard medical care, educational program, drug treatment, etc.) on QOL, asthma control, pulmonary function and exercise tolerance in adults with chronic persistent or clinically stable asthma.

Methods

The methods of this review strictly followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [13] (see Additional file 1: Table S1).

Search strategy

The PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, International Clinical Trials Registry Platform and ClinicalTrials.gov databases were searched from inception to 31 July 2019 without language restriction. Detailed search strategies were developed for each database related to “asthma” and “pulmonary rehabilitation” (including “exercise training”, “exercise therapy”, “endurance training”, “resistance training”, “muscle stretching exercises”, “upper limb training”, and “interval training”) and “randomized controlled trials (RCTs)”. We also reviewed the references of the included literature and correlated systematic reviews.

Study selection

The study selection was conducted by two investigators, and any disagreements were resolved through consultation with a third investigator. First, repeated and irrelevant studies were discarded by examining titles and abstracts. Then, the full texts of potentially eligible studies were obtained and reviewed according to inclusion and exclusion criteria.

The inclusion criteria included all of the following: (i) participants with chronic persistent or clinically stable asthma who were greater than 18 years old; (ii) the intervention involved any exercise-based PR techniques, such as endurance training, resistance training, muscle stretching exercises, exercise training, upper limb training, flexibility training and interval training; (iii) at least one of the outcomes measured QOL, asthma control, pulmonary function or exercise tolerance; and (iv) the study design was an RCT.

The exclusion criteria included any of the following: (i) participants with complications of any other pulmonary diseases in addition to asthma; (ii) the literature type was a study protocol; and (iii) the full texts could not be obtained, such as with meeting abstracts or supplements.

Data extraction

Data extraction was conducted by two investigators, and disagreements were resolved by a third investigator. Information including author information, publication year, study design, region, participants (age, sex and sample size), interventions, comparator and outcomes was extracted. The primary outcome measure was QOL, as measured by the asthma QOL questionnaire (AQLQ) [14]. The secondary outcome measures were as follows: (i) asthma control, as measured by asthma control questionnaire (ACQ) [15, 16] and asthma symptom-free days; (ii) pulmonary function, measured by forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC) and peak expiratory flow (PEF); and (iii) exercise tolerance, as measured by the 6-min walk distance (6 MWD) and maximum oxygen uptake (VO2 max). When studies provided insufficient data for meta-analysis, we contacted the first author or corresponding author by email to determine whether additional data could be provided to us.

Risk of bias evaluation

Risk of bias was evaluated by two investigators, with a third investigator acting as an arbiter in the case of inconsistency, using the Cochrane risk of bias tool [17]. Aspects evaluated included random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting and other bias. Each study was scored with “low risk of bias”, “unclear risk of bias” or “high risk of bias”.

Data analysis

The meta-analysis was conducted using RevMan software (version 5.3). Data are presented as the mean and standard deviation (SD). The effect size was estimated by the mean difference (MD) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for continuous outcome measures. In the case of different scales (e.g., ACQ-6 and ACQ-7) for the same outcome measure, the standardized MD (SMD) was chosen [17]; a missing SD was calculated if possible. A fixed-effect model was applied if there was no statistically significant heterogeneity; otherwise, a random-effect model was employed [17]. The χ2 test with P < 0.1 or I2 > 50% indicated significant heterogeneity [18]. Additionally, we examined the effects of exercise-based PR on different domains of the QOL scale. If the data could not be assessed by meta-analyses, we summarized them in the text in qualitative ways.

Evidence quality evaluation

The quality of evidence for primary outcomes was evaluated using GRADEpro (GRADEproGDT, http://www.gradepro.org/) [19]. Factors downgrading the evidence quality (risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias) were rated, and the evidence quality was assessed as “very low”, “low”, “moderate” or “high”.

Results

Literature search and study selection

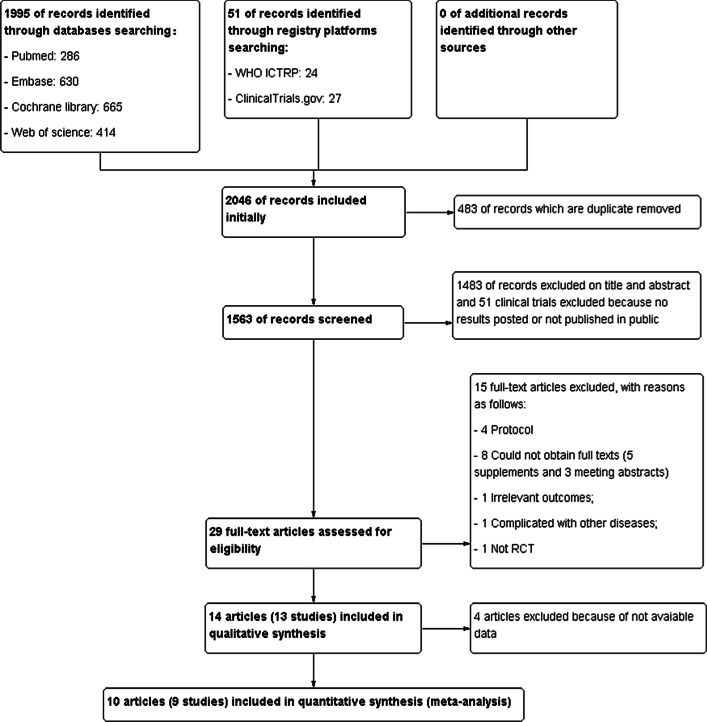

A total of 2046 records were identified. Fourteen literatures [20–33] from 13 studies were included in the qualitative synthesis, and 10 literatures [24–33] from 9 studies, including 418 participants, were eventually included in the meta-analysis. The process of study selection is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Study flow diagram

Data extraction and risk of bias evaluation

The basic characteristics extracted from the included literatures are shown in Table 1. The risk of bias evaluation is summarized in Additional file 2: Figures S1, and Additional file 3: Figures S2.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of the included studies

| Study | Country | Design | Participants | Interventions | Outcomes | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| França-Pinto et al. [24] | Brazil |

RCT, 2 arms |

Participant status: Sex(F/M): EG: 17/5; CG: 17/4 Age(years): EG: 40 ± 11; CG: 44 ± 9 Participants randomly assigned: 43 participants were randomly assigned Analysed: EG: 22; CG: 21 |

EG: breathing exercise programme + educational programme + aerobic training programme CG: breathing exercise programme + educational programme Duration of treatments: 3 months |

IL-5, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, MCP-1, IgE, clinical control (asthma symptom-free days, ACQ), AQLQ, induced sputum, exercise capacity (VO2 max, maximal workload, pulmonary function (FEV1, FEV1% predicted) | |

| Cochrane and Clark [25] | Scotland |

RCT, 2 arms |

Participant status: Sex(F/M): 22/14 Age(years): EG: 27 ± 7; CG: 28 ± 8 Participants randomly assigned: 36 participants were randomly assigned Analysed: EG: 18; CG: 18 |

EG: physical training (aerobic exercises, stretching exercises) + educational sessions CG: educational sessions Duration of treatments: 3 months |

FEV1, FEV1% pre, VO2 max, oxygen pulse, body fat, cholesterol, LDL, HDL, max heart rate, VE max, VT, RR, VEO2, DI max (%) | |

| Refaat and Gawish [26] | Kuwait |

RCT, 2 arms |

Participant status: Sex(F/M): EG: 21/17; CG: 16/14 Age(years): EG: 35.8 ± 1.7; CG: 38 ± 5.3 Participants randomly assigned: 68 participants were randomly assigned Analysed: EG: 38; CG: 30 |

EG: physical training + standard medical care CG: standard medical care Duration of treatments: 3 months |

AQLQ, pulmonary function (FEV1, FVC, PEF) | |

| Toennesen et al. [27] | Denmark |

RCT, 4 arms |

Participant status: Sex(F/M): EG: 22/7; CG: 25/8 Age(years): EG: 43.7 ± 13.9; CG: 40.7 ± 14.7 Participants randomly assigned: 62 participants were randomly assigned Analysed: EG: 29; CG: 33 |

EG: high-intensity interval training CG: diet Duration of treatments: 8 weeks |

AQLQ, ACQ, VO2 max, FEV1%pred, FVC %pred, FENO, serum IL-6, serum hs-CRP, blood eosinophils, sputum eosinophils (%), sputum neutrophils (%) | Data from exercise and diet groups were analysed |

| Turner et al. [28] | Australia |

RCT, 2 arms |

Participant status: Sex(F/M): EG: 11/8; CG: 8/7 Age(years): EG: 65.3 ± 10.8, CG: 71.0 ± 9.7 Participants randomly assigned: 34 participants were randomly assigned Analysed: EG: 19; CG: 15 |

EG: exercise training + standard medical care CG: standard medical care Duration of treatments: 3 months |

AQLQ, ACQ, SF-36, 6 MWD, HADS, peak heart rate, SpO2 end test, dyspnoea end test, Quadriceps strength (% of pre), Hand grip strength (% of pre) | |

| Shaw and Shaw [29] | South Africa |

RCT, 4 arms |

Participant status: Sex(F/M): EG: 8/14; CG: 8/14 Age(years): EG: 21.95 ± 3.87; CG: 21.90 ± 3.89 Participants randomly assigned: 44 participants were randomly assigned Analysed: EG: 22; CG: 22 |

EG: aerobic exercise CG: normal daily activities Duration of treatments: 8 weeks |

FEV1, FVC, FEV1/FVC, PEF, MVV, IVC, VE, VT, mean chest circumferences at the height of the second intercostal space | Data from aerobic exercise (AE) and nonexercise control (NE) groups were analysed |

| Cambach et al. [30] | the Netherlands |

RCT, 2 arms |

Participant status: Sex(F/M): EG: 18/4; CG: 14/7 Age(years): EG: 40 ± 10; CG: 53 ± 15 Participants randomly assigned: 43 participants were randomly assigned Analysed: EG: 22; CG: 21 |

EG: PR + drug treatment CG: drug treatment Duration of treatments: 3 months |

QOL, exercise tolerance (endurance time, cardiac frequency, 6 MWD) | A crossover design study, data of phase 1(from baseline to 3 months) were analysed |

| Freitas et al. [31] | Brazil |

RCT, 2 arms |

Participant status: Sex(F/M): EG: 25/1; CG: 25/0 Age(years): EG: 45.9 ± 7.7; CG: 48.5 ± 9.6 Participants randomly assigned: 51 participants were randomly assigned Analysed: EG: 26; CG: 25 |

EG: a weight-loss programme + exercise CG: a weight-loss programme + sham exercise Duration of treatments: 3 months |

AQLQ, ACQ, pulmonary function (FEV1, FVC, TLC, ERV), strength of muscle, VO2 max, work rate | Sham exercise; stretching exercise and breathing exercise that did not affect asthma control |

| Freitas et al. [32] | Brazil |

RCT, 2 arms |

Participant status: Sex(F/M): EG: 25/1; CG: 25/0 Age(years): EG: 45.9 ± 7.7; CG: 48.5 ± 9.6 Participants randomly assigned: 51 participants were randomly assigned Analysed: EG: 26; CG: 25 |

EG: a weight-loss programme + exercise CG: a weight-loss programme + sham exercise Duration of treatments: 3 months |

asthma symptom-free days | Sham exercise; stretching exercise and breathing exercise that did not affect asthma control |

| Coelho et al. [33] | Brazil |

RCT, 2 arms |

Participant status: Sex(F/M): EG: 18/2; CG: 14/3 Age(years): EG: 45.0 ± 19.0; CG: 47.0 ± 14.0 Participants randomly assigned: 37 participants were randomly assigned Analysed: EG: 20; CG: 17 |

EG: physical activity + usual care CG: usual care Duration of treatments: 3 months |

AQLQ, ACQ, HADS, daily steps, 6 MWD |

F female, M male, IL-5 interleukin 5, MCP monocyte chemoattractant protein, IgE immunoglobulin E, LDL low-density lipoprotein, HDL high-density lipoprotein, VE minute venFtilation, VT maximum tidal volume, RR maximum respiratory rate, VEO2 ventilatory equivalent for oxygen at maximal exercise, DI max dyspnoea index at maximal exercise, FENO fractional exhaled nitric oxide, CRP C-reactive protein, HADS hospital anxiety and depression scale, SpO2 percutaneous oxygen saturation, MVV maximal voluntary ventilation, IVC inspiratory vital capacity, TLC total lung capacity, ERV expiratory reserve volume

Effects of inventions

The results of the meta-analyses are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Meta-analysis of exercise-based PR for asthma

| Outcomes | No. of RCTs | No. of participants | Effect estimate (95% CI) | I2 (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome measures | ||||||

| Quality of life | ||||||

| AQLQ (Overall QOL) | 4 | 198 | MD 0.39 (0.02, 0.76) | 0 | 0.04 | |

| AQLQ (Activity domain) | 4 | 196 | MD 0.58 (0.21, 0.94) | 0 | 0.002 | |

| AQLQ (Symptom domain) | 4 | 196 | MD 0.52 (0.19, 0.85) | 0 | 0.002 | |

| AQLQ (Emotion domain) | 4 | 196 | MD 0.53 (− 0.03, 1.09) | 0 | 0.06 | |

| AQLQ (Environment domain) | 4 | 196 | MD 0.56 (0.00, 1.11) | 0 | 0.05 | |

| Secondary outcome measures | ||||||

| Asthma control | ACQ | 5 | 215 | SMD − 0.25 (0.51, 0.02) | 0 | 0.07 |

| Asthma symptom-free days | 2 | 94 | MD 3.35 (− 0.21, 6.90) | 17 | 0.07 | |

| Pulmonary function | FEV1 | 5 | 242 | MD 0.10 (− 0.08, 0.29) | 74 | 0.28 |

| FVC | 3 | 163 | MD 0.23 (0.08, 0.38) | 0 | 0.003 | |

| PEF | 2 | 112 | MD 0.39 (0.21, 0.57) | 0 | < 0.0001 | |

| Exercise tolerance | 6 MWD | 3 | 94 | MD 34.09 (2.51, 65.66) | 0 | 0.03 |

| VO2 max | 3 | 141 | MD 4.45 (3.32, 5.58) | 0 | < 0.00001 | |

RCTs randomized controlled trials, CI confidence interval, AQLQ asthma quality of life questionnaire, MD mean difference, ACQ asthma control questionnaire, SMD standardized MD, FEV1 forced expiratory volume in 1 s, FVC forced vital capacity, PEF peak expiratory flow, 6 MWD 6-min walk distance, VO2 max maximum oxygen uptake

AQLQ

Six studies [24, 26–28, 31, 33] (283 participants) provided numerical data for the AQLQ and were included in the meta-analysis. Among them, four studies [24, 26, 27, 33] (198 participants) provided the total AQLQ scores; there was no statistical heterogeneity (χ2 = 0.03, P = 1.00; I2 = 0%), and a fixed-effects model was adopted. The pooled results showed that the total AQLQ scores in the experimental group (EG) were significantly improved compared to those in the control group (CG) (MD, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.02 to 0.76; Z = 2.06, P = 0.04). Four studies [24, 26, 28, 31] (196 participants) provided AQLQ domain scores. For the activity domain, there was no statistical heterogeneity (χ2 = 0.77, P = 0.86; I2 = 0%), and a fixed-effects model was utilized. The activity domain scores in EG improved more than those in CG (MD, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.21 to 0.94; Z = 3.10, P = 0.002). In the symptom domain, there was no statistical heterogeneity (χ2 = 0.24, P = 0.97; I2 = 0%), and a fixed-effect model was used. The symptom domain scores in EG improved more than those in CG (MD, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.19 to 0.85; Z = 3.07, P = 0.002). There was no statistical heterogeneity in the emotion domain (χ2 = 0.24, P = 0.97; I2 = 0%), and a fixed-effect model was used. According to pooled data, there was no statistically significant improvement between the two groups (MD, 0.53; 95% CI, -0.03 to 1.09; Z = 1.87, P = 0.06). Regarding the environment domain, there was no statistical heterogeneity (χ2 = 1.18, P = 0.76; I2 = 0%), and a fixed-effect model was selected. The pooled data showed no statistically significant improvement between the two groups (MD, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.00 to 1.11; Z = 1.98, P = 0.05) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Forest plot of exercise-based PR on AQLQ in patients with asthma. AQLQ: asthma quality of life questionnaire; SD: standard deviation; CI: confidence interval

ACQ

Six studies [20, 24, 27, 28, 31, 33] investigated the effects of exercise-based PR on asthma control by ACQ. Among them, five studies [24, 27, 28, 31, 33] (215 participants) provided numerical data for ACQ scores and were included in the meta-analysis. There was no statistical heterogeneity (χ2 = 0.73, P = 0.95; I2 = 0%), and a fixed-effect model was applied. The data revealed no statistically significant improvement between the two groups (MD, − 0.25; 95% CI, − 0.51 to 0.02; Z = 1.79, P = 0.07). One study [20], which was not included in the meta-analysis, reported a mean improvement in asthma control of 0.22 versus 0.73, but the change was not statistically significant between the two groups (see Additional file 4: Figure S3).

Asthma symptom-free days

Five studies [21–24, 32] investigated the effects of exercise-based PR on asthma symptom-free days; two studies [24, 32] (94 participants) provided numerical data and were included in the meta-analysis. Because there was no statistical heterogeneity (χ2 = 1.20, P = 0.27; I2 = 17%), a fixed-effect model was used. However, there was no statistically significant improvement between the two groups (MD, 3.35; 95% CI, -0.21 to 6.90; Z = 1.84, P = 0.07). Three studies [21–23] that were not included in the meta-analysis reported a statistically significant improvement (see Additional file 5: Figure S4).

FEV1

Seven studies [20, 22, 24–26, 29, 31] investigated the effects of exercise-based PR on FEV1. Among them, five [24–26, 29, 31] (242 participants) provided numerical data for FEV1 and were included in the meta-analysis. There was statistical heterogeneity (χ2 = 15.37, P = 0.004; I2 = 74%); thus, a random-effects model was used. According to the data, there was no statistically significant improvement (MD, 0.10; 95% CI, − 0.08 to 0.29; Z = 1.08, P = 0.28) between the two groups. Two studies [20, 22] also reported no change in FEV1 between the two groups (see Additional file 6: Figure S5).

FVC

Four studies [22, 26, 29, 31] investigated the effects of exercise-based PR on FVC. Among them, three studies [26, 29, 31] (163 participants) provided numerical data for FVC and were included in the meta-analysis. There was no statistical heterogeneity (χ2 = 0.12, P = 0.94; I2 = 0%), and a fixed-effect model was used. The data showed greater improvement in EG (MD, 0.23; 95% CI, 0.08 to 0.38; Z = 2.94, P = 0.003) than in CG. One study [22] reported no change in FVC between the two groups (see Additional file 7: Figure S6).

PEF

Two studies [26, 29] (112 participants) provided numerical data for PEF; they were included in the meta-analysis. A fixed-effect model was used due to a lack of statistical heterogeneity (χ2 = 0.02, P = 0.87; I2 = 0%). The data showed a greater effect in EG (MD, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.21 to 0.57; Z = 4.32, P < 0.0001) than in CG (see Additional file 8: Figure S7).

6 MWD

Three studies [28, 30, 33] (94 participants) provided numerical data for 6 MWD. As there was no statistical heterogeneity (χ2 = 1.06, P = 0.59; I2 = 0%), a fixed-effect model was used. The effect in EG was greater (MD, 34.09; 95% CI, 2.51 to 65.66; Z = 2.12, P = 0.03) than that in CG (see Additional file 9: Figure S8).

VO2 max

Five studies [21, 22, 24, 25, 27] investigated the effects of exercise-based PR on VO2 max. Among them, three [24, 25, 27] (141 participants) provided numerical data and were included in the meta-analysis. There was no statistical heterogeneity (χ2 = 1.50, P = 0.47; I2 = 0%), and a fixed-effect model was used. The data showed that the effect in EG was superior (MD, 4.45; 95% CI, 3.32 to 5.58; Z = 7.74, P < 0.00001) to that in CG. Two studies [21, 22] that were not included in the meta-analysis also reported a significant increase in VO2 max between the two groups (see Additional file 10: Figure S9).

Evidence quality evaluation

The overall AQLQ and every domain were rated as having “moderate quality” due to small sample sizes and wide confidence intervals. The GRADE evidence profile is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Quality of evidence for primary outcomes in patients with asthma

| Certainty assessment | No. of patients | Effect | Certainty | Importance | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of included studies | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsiste-ncy | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerat-ions | Experimental group | Control group | Relative (95% CI) | Absolute (95% CI) | ||

| Asthma quality of life—AQLQ (overall QOL) | ||||||||||||

| 4 | RCT | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Seriousa | None | 101 | 97 | – |

MD 0.39 higher (0.02 higher to 0.76 higher) |

⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate |

Critical |

| Asthma quality of life—AQLQ (activity domain) | ||||||||||||

| 4 | RCT | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Seriousa | None | 105 | 91 | – |

MD 0.58 higher (0.21 higher to 0.94 higher) |

⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate |

Critical |

| Asthma quality of life—AQLQ (symptom domain) | ||||||||||||

| 4 | RCT | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Seriousa | None | 105 | 91 | – |

MD 0.52 higher (0.19 higher to 0.85 higher) |

⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate |

Critical |

| Asthma quality of life—AQLQ (emotion domain) | ||||||||||||

| 4 | RCT | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Seriousa | None | 105 | 91 | – |

MD 0.53 higher (0.03 lower to 1.09 higher) |

⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate |

Critical |

| Asthma quality of life—AQLQ (environment domain) | ||||||||||||

| 4 | RCT | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Seriousa | None | 105 | 91 | – |

MD 0.56 higher (0 to 1.11 higher) |

⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate |

Critical |

CI confidence interval, RCT randomized controlled trial, AQLQ asthma quality of life questionnaire, MD mean difference

aSmall sample size and wide confidence interval

Discussion

PR is a comprehensive intervention designed to improve the physical and psychological condition of people with chronic respiratory disease and to promote long-term adherence to health-enhancing behaviours [34]. In recent years, quite a few studies have confirmed the positive effects of PR on patients with respiratory conditions, such as cystic fibrosis, bronchiectasis, interstitial lung disease, and lung transplantation [35–38]. Exercise training is part of PR, which has been applied widely. This systematic review and meta-analysis summarized the effects of exercise-based PR on adults with chronic persistent or clinically stable asthma, aiming to provide evidence for clinicians and policy makers.

QOL, an important index for characterizing patient populations and evaluating therapeutic interventions, cannot be captured by biological or clinical indicators. The AQLQ is a widely used instrument to evaluate QOL in those with asthma; it consists of an activity domain, symptom domain, emotion domain and environment domain. Our meta-analysis showed that exercise-based PR significantly improved overall QOL as well as each domain, with a consistent trend, but the improvement in the emotion and environment domains was not statistically significant. The p value was 0.06 in the emotion domain, near 0.05; it was 0.05 in the environment domain. This may be due to the small sample size; thus, significant improvement was not detected. From another perspective, many people with asthma also have emotional problems, such as anxiety and depression. This is usually related to multiple factors, including older age, lower income, use of oral corticosteroids, patients’ perceived severity of asthma, disability, social support and personality traits [39]. In addition, the environmental domain of AQLQ includes cigarette smoke, dust, weather or air pollution outside, and strong smells or perfumes. Environmental risk factors are challenging in adult-onset asthma and play an important role in asthma or related phenotypes [40]. The dynamic and unique biological responses triggered by allergens and air pollutants have proven difficult to predict and prevent [41]. Thus, exercise-based PR alone may not be effective owing to the complexity of emotional and environmental aspects. RCTs with larger sample sizes are necessary to prove the effects of exercise-based PR on these domains of the AQLQ.

Asthma control levels were evaluated by both the ACQ and asthma symptom-free days. There was no statistically significant decrease (a higher score on the ACQ indicates worse asthma control), with an SMD of − 0.25. A recent study [42] reported that regular exercise improves asthma control in adults, which is opposite to our results. Probable explanations are as follows. First, the intervention time of our included studies referring to the ACQ was no more than three months, while that of the previous study was six months. Second, the measurement instrument of our review was the ACQ, while the instrument used in the previous study was the asthma control test. For asthma symptom-free days, there was no statistically significant decrease, with an MD of 3.35 days. Exercise-based PR in proper time and intensity may improve asthma control.

Pulmonary function tests are applied for diagnosing and monitoring at the patient level and for evaluating population trends in respiratory disease over time [43]. As reported in a previous meta-analysis [9], there was no significant improvement in FEV1. In terms of FVC, there was significant improvement in three studies [26, 29, 31]. However, one study [22] reported no change between the two groups, and it was not included in the meta-analysis because data were reported as medians and interquartile ranges. A statistically significant improvement in PEF was detected in our review, in contrast to the meta-analysis conducted by Carson and Ram [8, 10]. Divergent opinions exist regarding the effects of exercise-based PR on the pulmonary function of asthma patients, and this may be due to small sample sizes, different exercise durations and intensities, and asthma severity, among others.

Exercise tolerance was evaluated by 6 MWD and VO2 max in our review. EG had a statistically significant improvement by 34.09 m compared with CG. There was a statistically significant improvement in VO2 max, with an MD of 4.45, which is in accordance with a previous meta-analysis [6, 8, 9]. These results support the idea that exercise-based PR enhances exercise tolerance.

There were some limitations in our study. First, the sample size was small, leading to imprecision of outcomes. Nonetheless, this is the only systematic review and meta-analysis to date evaluating the effectiveness of exercise-based PR in adults with asthma. Second, there were various forms of exercise-based PR, which made it difficult to evaluate the effect of a single form. Third, the characteristics of interventions made it difficult to implement blinding, leading to potential performance bias. Finally, four studies could not be included in the quantitative analysis because of the original forms of data reported, such as medians or quartiles; thus, the data could not be used fully.

Conclusions

Exercise-based PR may improve the QOL, exercise tolerance and pulmonary function of adults with asthma and can be considered a supplementary therapy for asthma management. Additionally, asthma control may be enhanced with proper time and intensity of exercise-based PR. RCTs of high quality and large sample sizes are required for further research.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1. The PRISMA Checklist.

Additional file 2: Figure S1. Risk of bias evaluation.

Additional file 3: Figure S2. Risk of bias evaluation.

Additional file 4: Figure S3. Funnel plots of all studies for each secondary outcome measure.

Additional file 5: Figure S4. Funnel plots of all studies for each secondary outcome measure.

Additional file 6: Figure S5. Funnel plots of all studies for each secondary outcome measure.

Additional file 7: Figure S6. Funnel plots of all studies for each secondary outcome measure.

Additional file 8: Figure S7. Funnel plots of all studies for each secondary outcome measure.

Additional file 9: Figure S8. Funnel plots of all studies for each secondary outcome measure.

Additional file 10: Figure S9. Funnel plots of all studies for each secondary outcome measure.

Acknowledgements

None.

Abbreviations

- PR

Pulmonary rehabilitation

- GRADE

Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation

- RCT

Randomized controlled trial

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- EG

Experimental group

- CG

Control group

- QOL

Quality of life

- SD

Standard deviation

- MD

Mean difference

- CI

Confidence interval

- F

Female

- M

Male

- IL-5

Interleukin 5

- MCP

Monocyte chemoattractant protein

- IgE

Immunoglobulin E

- ACQ

Asthma control questionnaire

- AQLQ

Asthma quality of life questionnaire

- VO2 max

Maximum oxygen uptake

- FEV1

Forced expiratory volume in 1 s

- LDL

Low density lipoprotein

- HDL

High density lipoprotein

- VE

Minute ventilation

- VT

Maximum tidal volume

- RR

Maximum respiratory rate

- VEO2

Ventilatory equivalent for oxygen at maximal exercise

- DI max

Dyspnea index at maximal exercise

- FVC

Forced vital capacity

- PEF

Peak expiratory flow

- FENO

Fractional exhaled nitric oxide

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- 6 MWD

6-Min walk distance

- HADS

Hospital anxiety and depression scale

- SpO2

Percutaneous oxygen saturation

- MVV

Maximal voluntary ventilation

- IVC

Inspiratory vital capacity

- TLC

Total lung capacity

- ERV

Expiratory reserve volume

Authors’ contributions

Jiansheng Li conceived this study. Zhenzhen Feng searched the literature, conducted the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. Yang Xie and Jiajia Wang screened the studies, extracted the data, and evaluated the risk of bias. Yang Xie revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Supported by the Qihuang Scholars Award of the State TCM Academic Leader Program and Central Plains Thousand People Program (No. ZYQR201810159). These funders have no any roles in the design of the study, analysis, interpretation of data, decision to publish or in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during the present study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12931-021-01627-w.

References

- 1.Global Initiative for Asthma. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. 2019. https://ginasthma.org/gina-reports. Accessed 15 Feb 2020.

- 2.GBD 2015 Chronic Respiratory Disease Collaborators Global, regional, and national deaths, prevalence, disability-adjusted life years, and years lived with disability for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet Respir Med. 2017;5:691–706. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30293-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang K, Yang T, Xu J, Yang L, Zhao J, Zhang X, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and management of asthma in China: a national cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2019;394:407–418. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31147-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nici L, Donner C, Wouters E, Zuwallack R, Ambrosino N, Bourbeau J, et al. American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement on pulmonary rehabilitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:1390–1413. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200508-1211ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spruit MA, Singh SJ, Garvey C, ZuWallack R, Nici L, Rochester C, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: key concepts and advances in pulmonary rehabilitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:e13–64. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201309-1634ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eichenberger PA, Diener SN, Kofmehl R, Spengler CM. Effects of exercise training on airway hyperreactivity in asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2013;43:1157–1170. doi: 10.1007/s40279-013-0077-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ram FS, Robinson SM, Black PN. Effects of physical training in asthma: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2000;34:162–167. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.34.3.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ram FS, Robinson SM, Black PN, Picot J. Physical training for asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001116.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heikkinen SA, Quansah R, Jaakkola JJ, Jaakkola MS. Effects of regular exercise on adult asthma. Eur J Epidemiol. 2012;27:397–407. doi: 10.1007/s10654-012-9684-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carson KV, Chandratilleke MG, Picot J, Brinn MP, Esterman AJ, Smith BJ. Physical training for asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pakhale S, Luks V, Burkett A, Turner L. Effect of physical training on airway inflammation in bronchial asthma: a systematic review. BMC Pulm Med. 2013;13:38. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-13-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Francisco CO, Bhatawadekar SA, Babineau J, Reid WD, Yadollahi A. Effects of physical exercise training on nocturnal symptoms in asthma: systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0204953. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0204953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Epstein RS, Ferrie PJ, Jaeschke R, Hiller TK. Evaluation of impairment of health related quality of life in asthma: development of a questionnaire for use in clinical trials. Thorax. 1992;47:76–83. doi: 10.1136/thx.47.2.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Juniper EF, O'Byrne PM, Guyatt GH, Ferrie PJ, King DR. Development and validation of a questionnaire to measure asthma control. Eur Respir J. 1999;14:902–907. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.14d29.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Juniper EF, Bousquet J, Abetz L, Bateman ED. Identifying 'well-controlled' and 'not well-controlled' asthma using the Asthma Control Questionnaire. Respir Med. 2006;100:616–621. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, et al. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions (version 6). 2019. https://training.cochrane.org/handbook. Accessed 15 Jan 2020.

- 18.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336:924–926. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boyd A, Yang CT, Estell K, Ms CT, Gerald LB, Dransfield M, et al. Feasibility of exercising adults with asthma: a randomized pilot study. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2012;8:13. doi: 10.1186/1710-1492-8-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mendes FA, Almeida FM, Cukier A, Stelmach R, Jacob-Filho W, Martins MA, et al. Effects of aerobic training on airway inflammation in asthmatic patients. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43:197–203. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181ed0ea3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mendes FA, Gonçalves RC, Nunes MP, Saraiva-Romanholo BM, Cukier A, Stelmach R, et al. Effects of aerobic training on psychosocial morbidity and symptoms in patients with asthma: a randomized clinical trial. Chest. 2010;138:331–337. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-2389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goncalves RC, Nunes MPT, Cukier A, Stelmach R, Martins MA, Carvalho CRF. Effects of an aerobic physical training program on psychosocial characteristics, quality-of-life, symptoms and exhaled nitric oxide in individuals with moderate or severe persistent asthma. Braz J Phys Ther. 2008;18:127–135. doi: 10.1590/S1413-35552008000200009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.França-Pinto A, Mendes FAR, de Carvalho-Pinto RM, Agondi RC, Cukier A, Stelmach R, et al. Aerobic training decreases bronchial hyperresponsiveness and systemic inflammation in patients with moderate or severe asthma: a randomised controlled trial. Thorax. 2015;70:732. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-206070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cochrane LM, Clark CJ. Benefits and problems of a physical training programme for asthmatic patients. Thorax. 1990;45:345–351. doi: 10.1136/thx.45.5.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Refaat A, Gawish M. Effect of physical training on health-related quality of life in patients with moderate and severe asthma. Egypt J Chest Dis Tuberc. 2015;64:761–766. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcdt.2015.07.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Toennesen LL, Meteran H, Hostrup M, Wium Geiker NR, Jensen CB, Porsbjerg C, et al. Effects of exercise and diet in nonobese asthma patients-A randomized controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6:803–811. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2017.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Turner S, Eastwood P, Cook A, Jenkins S. Improvements in symptoms and quality of life following exercise training in older adults with moderate/severe persistent asthma. Respiration. 2011;81:302–310. doi: 10.1159/000315142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shaw BS, Shaw I. Pulmonary function and abdominal and thoracic kinematic changes following aerobic and inspiratory resistive diaphragmatic breathing training in asthmatics. Lung. 2011;189:131–139. doi: 10.1007/s00408-011-9281-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cambach W, Chadwick-Straver RV, Wagenaar RC, van Keimpema AR, Kemper HC. The effects of a community-based pulmonary rehabilitation programme on exercise tolerance and quality of life: a randomized controlled trial. Eur Respir J. 1997;10:104–113. doi: 10.1183/09031936.97.10010104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Freitas PD, Ferreira PG, Silva AG, Stelmach R, Carvalho-Pinto RM, Fernandes FL, et al. The role of exercise in a weight-loss program on clinical control in obese adults with asthma. A randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:32–42. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201603-0446OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Freitas PD, Silva AG, Ferreira PG, da Silva A, Salge JM, Carvalho-Pinto RM, et al. Exercise improves physical activity and comorbidities in obese adults with asthma. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2018;50:1367–1376. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coelho CM, Reboredo MM, Valle FM, Malaguti C, Campos LA, Nascimento LM, et al. Effects of an unsupervised pedometer-based physical activity program on daily steps of adults with moderate to severe asthma: a randomized controlled trial. J Sports Sci. 2018;36:1186–1193. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2017.1364402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spruit MA. Pulmonary rehabilitation. Eur Respir Rev. 2014;23:55–63. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00008013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dassios T, Katelari A, Doudounakis S, Dimitriou G. Aerobic exercise and respiratory muscle strength in patients with cystic fibrosis. Respir Med. 2013;107:684–690. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2013.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mandal P, Sidhu MK, Kope L, Pollock W, Stevenson LM, Pentland JL, et al. A pilot study of pulmonary rehabilitation and chest physiotherapy versus chest physiotherapy alone in bronchiectasis. Respir Med. 2012;106:1647–1654. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yuen HK, Lowman JD, Oster RA, de Andrade JA. Home-based pulmonary rehabilitation for patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a pilot study. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2019;39:281–284. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0000000000000418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Florian J, Watte G, Teixeira PJZ, Altmayer S, Schio SM, Sanchez LB, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation improves survival in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis undergoing lung transplantation. Sci Rep. 2019;9:9347. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-45828-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Adewuya AO, Adeyeye OO. Anxiety and depression among Nigerian patients with asthma; Association with sociodemographic, clinical, and personality factors. J Asthma. 2017;54:286–293. doi: 10.1080/02770903.2016.1208224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Le Moual N, Jacquemin B, Varraso R, Dumas O, Kauffmann F, Nadif R. Environment and asthma in adults. Presse Med. 2013;42:e317–e333. doi: 10.1016/j.lpm.2013.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang IV, Lozupone CA, Schwartz DA. The environment, epigenome, and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140:14–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jaakkola JJK, Aalto SAM, Hernberg S, Kiihamäki S-P, Jaakkola MS. Regular exercise improves asthma control in adults: a randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep. 2019;9:12088. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-48484-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stanojevic S. Standardisation of lung function test interpretation: global lung function initiative. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6:10–12. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30472-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. The PRISMA Checklist.

Additional file 2: Figure S1. Risk of bias evaluation.

Additional file 3: Figure S2. Risk of bias evaluation.

Additional file 4: Figure S3. Funnel plots of all studies for each secondary outcome measure.

Additional file 5: Figure S4. Funnel plots of all studies for each secondary outcome measure.

Additional file 6: Figure S5. Funnel plots of all studies for each secondary outcome measure.

Additional file 7: Figure S6. Funnel plots of all studies for each secondary outcome measure.

Additional file 8: Figure S7. Funnel plots of all studies for each secondary outcome measure.

Additional file 9: Figure S8. Funnel plots of all studies for each secondary outcome measure.

Additional file 10: Figure S9. Funnel plots of all studies for each secondary outcome measure.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during the present study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.