Abstract

Advanced, late-stage Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-positive nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is incurable, and its treatment remains a clinical and therapeutic challenge. Results from a phase II clinical trial in advanced NPC patients employing a combined chemotherapy and EBV-specific T cell (EBVST) immunotherapy regimen showed a response rate of 71.4%. Longitudinal analysis of patient samples showed that an increase in EBV DNA plasma concentrations and the peripheral monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio negatively correlated with overall survival. These parameters were combined into a multivariate analysis to stratify patients according to risk of death. Immunophenotyping at serial time points showed that low-risk individuals displayed significantly decreased amounts of monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells postchemotherapy, which subsequently influenced successful cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) immunotherapy. Examination of the low-risk group, 2 weeks post-EBVST infusion, showed that individuals with a greater overall survival possessed an increased frequency of CD8 central and effector memory T cells, together with higher levels of plasma interferon (IFN)-γ, and cytotoxic lymphocyte-associated transcripts. These results highlight the importance of the rational selection of chemotherapeutic agents and consideration of their impact on both systemic immune responses and downstream cellular immunotherapy outcomes.

Keywords: immunotherapy, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, EBV, T cell, MDSC

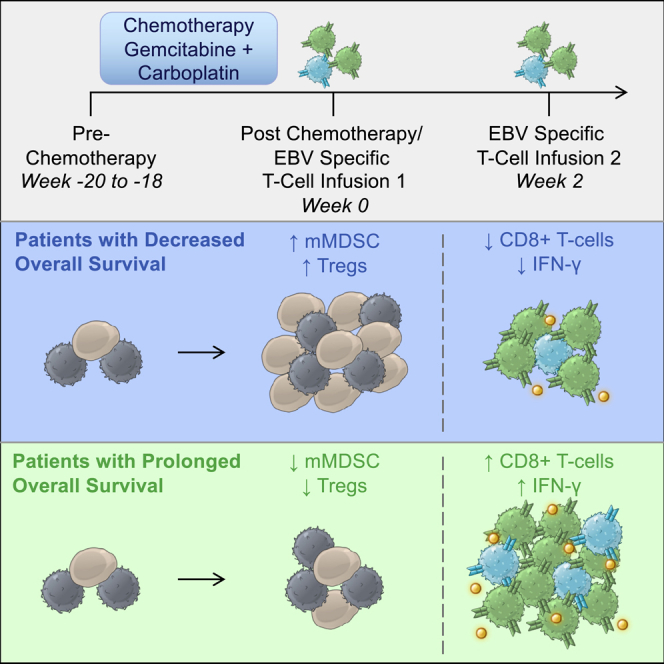

Graphical Abstract

Patients with advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma were treated with a combined chemotherapy and cellular immunotherapy regimen. Those who displayed lower overall survival possessed higher amounts of regulatory leukocytes following chemotherapy. These results demonstrated the importance of the rational selection of chemotherapeutic agents and consideration of their impact on both systemic immune responses and downstream cellular immunotherapy outcomes.

Introduction

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-positive nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) represents a significant health problem in Asia. Incidence rate of NPC in Southeast Asian males is 10 to 21.4 per 100,000.1 Early intervention with radiotherapy and radiochemotherapy for stage I and II disease, respectively, can lead to successful treatment in over 80% of cases. However, beyond chemotherapy, the therapeutic options for late-stage disease remain comparably limited.2 An alternative to standard chemotherapy regimens is the use of immunotherapeutic strategies, which focus on increasing the immune response to cancer-associated antigens. Experimental NPC immunotherapies have included dendritic cell (DC) vaccination,3, 4, 5 immune checkpoint blockade (ICB),6, 7, 8, 9 and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) infusion.10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 NPC and other virally derived cancers should be an ideal candidate for immunotherapeutic strategies due to the presence of nonself, viral antigens, which are more immunogenic than neo-epitopes found in cancers that arise from inherited or de novo mutations.

Pursuant to this, we conducted a phase II trial in the first line setting, employing four cycles of gemcitabine and carboplatin chemotherapy, followed by adoptive transfer of six serial infusions of autologous, in vitro-expanded EBV-specific T cells (EBVSTs). The overall response rate for this therapy was 71.4%, with a median overall survival of 29.9 months.17 However, despite the favorable clinical outcomes, there was still a subset of patients who did not show a benefit from receiving EBVST immunotherapy, suggesting that a more dominant environment of immunosuppression exists in these individuals that potentially compromises efficacy.

The understanding of the correlative biological markers, which could identify mechanisms that drive resistance to EBVST treatment can potentially uncover a broader understanding of mechanisms of tumor resistance to immunotherapy. One readily available biomarker is the complete blood count, which is able to determine leukocyte subset frequencies. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratios and monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratios (MLRs) have been used as a prognostic in many cancer indications.18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24 Although not validated, they have also been used to categorize responding patients undergoing chemotherapy25, 26, 27, 28 and outcomes to ICB.29, 30, 31, 32, 33 However, in order to increase the accuracy of immunotherapy patient stratification, it is likely that the measurement of multiple biological factors must be conducted to better identify patients who are most likely to respond.34, 35, 36

Here, we devised a stratification methodology based on plasma EBV DNA concentrations and peripheral MLRs to determine risk of death. High-risk individuals who failed to respond to EBVST therapy displayed an increase in monocyte frequency, immunosuppressive cytokines, and myeloid chemoattractants postchemotherapy. Flow cytometric analysis revealed that resistance to immunotherapy correlates with a postchemotherapy efflux of a specific monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cell (mMDSC) population. Conversely, patients who responded to therapy displayed increased CD8 memory T cell frequencies, increased peripheral interferon (IFN)-γ levels, and increased expression cytotoxic lymphocyte-associated transcripts, 2 weeks post-first EBVST infusion. This report demonstrates that expansion of the myeloid compartment can exert a dominant immune-suppressive effect, which points toward a window of therapeutic opportunity and thus determines successful immunotherapy.

Results

Overall Survival Correlated with Decreased MLRs and EBV Plasma Concentrations

Treatment of 38 NPC patients with a combined chemotherapy of gemcitabine and carboplatin, followed by EBVST immunotherapy regimen, showed an increase in overall response rates when retrospectively compared to similar trials using chemotherapy regimens alone.17,37,38 Here, we aim to investigate the underlying mechanisms that could account for both patients who benefit and those who do not from the combined chemo- and immunotherapies by performing longitudinal analyses on cryopreserved samples.

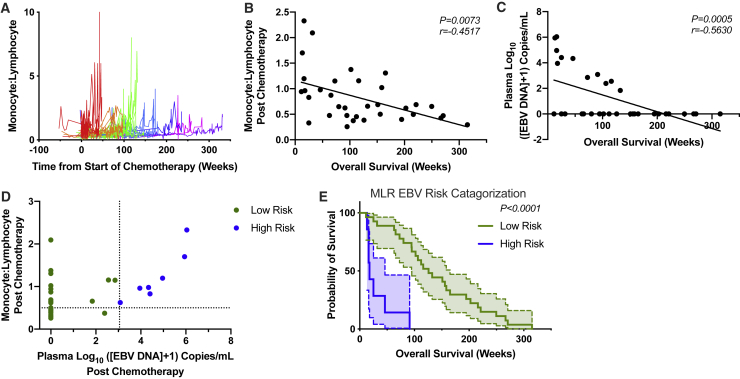

Clearance of NPC is dependent on lymphocyte action. Decreased amounts of lymphocytes in relation to other leukocyte subsets have been correlated with poor prognosis in NPC as well as other cancer indications.18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24 Observation of the longitudinal MLR kinetics in regard to overall survival showed that patients experienced an increase close to the time of death (Figures 1A and S2). Following this finding, multiple univariate analyses of peripheral clinical parameters, including full blood counts, ratio-metric analyses of leukocyte populations, and EBV DNA plasma concentration, at the pre- and postchemotherapy time points, were performed to examine their relationship to overall survival (Table 1). EBV DNA plasma concentration and MLR were the most significantly correlated parameters with survival compared to the other factors (Table 1; Figures 1B and 1C). These two parameters were then combined in a multivariate analysis in order to better define patients, attributing them to either a high- or low-risk category, relating to their time of death (Figure 1D). Kaplan-Meier plots of the risk groups yielded an improved separation compared to using either of the single variates alone (Figures 1E and S3). These results show that patients who experience both increased MLR and EBV plasma concentrations have decreased overall survival and thus less potential benefit from immunotherapy, suggesting that a degree of interplay may exist between these parameters. These conditions could yield an immunosuppressive environment, rendering conditions adverse for optimal immunotherapy.

Figure 1.

Overall Survival Correlated with Decreased Monocyte-to-Lymphocyte Ratios (MLRs) and EBV Plasma Concentrations

(A) Longitudinal MLRs, calculated from clinical complete blood counts. Colored line sets represent different intervals of overall survival, with each patient indicated as a single line. Overall survival in weeks for the colors are as follows: red, <50; orange, >50, <100; green, >100, <150; light blue, >150, <200; dark blue, >200, <250; pink, >250, <300; purple, >300. (B) Correlation of MLR with overall survival at postchemotherapy time point (Spearman correlation). (C) Correlation of plasma EBV DNA concentrations with overall survival at postchemotherapy time point (Spearman correlation). (D) Stratification of patients with cutoffs of >3.05 log10 ([EBV DNA] + 1) and >0.5 MLR. (E) Survival plot of high- and low-risk individuals (Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test, 95% confidence interval [CI] shown between dashed lines). For all experiments, n = 34. (D and E) n = 7 high risk; 27 low risk.

Table 1.

Univariate Analysis of Clinical Parameters, with Overall Survival at Pre- and Postchemotherapy Time Points

| Prechemotherapy | Postchemotherapy | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard Ratio | p Value | Hazard Ratio | p Value | |

| Monocyte/lymphocyte ratio | 3.244 (1.333–7.898) | 9.53E−03 | 4.377 (1.93–9.927) | 4.09E−04 |

| EBV (/10,000) | 1.006 (1.001–1.012) | 1.38E−02 | 1.036 (1.014–1.059) | 1.59E−03 |

| Neutrophil count | 1.15 (1.022–1.294) | 2.00E−02 | 1.577 (1.113–2.235) | 1.03E−02 |

| Monocyte count | 4.007 (0.7209–22.27) | 1.13E−01 | 7.291 (1.469–36.18) | 1.51E−02 |

| WBC count | 1.143 (1.012–1.291) | 3.10E−02 | 1.375 (1.032–1.832) | 2.94E−02 |

| SII | 1 (1–1) | 1.20E−02 | 1 (1–1.001) | 4.35E−02 |

| Neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio | 1.067 (1.009–1.129) | 2.36E−02 | 1.141 (0.9955–1.308) | 5.80E−02 |

| Platelet count | 1.004 (1.001–1.007) | 2.26E−02 | 1.004 (0.999–1.008) | 1.28E−01 |

| Platelet/lymphocyte ratio | 1.001 (1–1.002) | 3.56E−02 | 1.001 (0.9993–1.003) | 2.39E−01 |

| Lymphocyte count | 0.8174 (0.4433–1.507) | 5.18E−01 | 0.8137 (0.4033–1.641) | 5.65E−01 |

| Eosinophil count | 0.7771 (0.0394–15.33) | 8.68E−01 | 1.743 (0.05878–51.69) | 7.48E−01 |

| Basophil count | 7.645 (2.81E−07–2.08E+08) | 8.16E−01 | 1.029 (1.39E−13–7.63E+12) | 9.99E−01 |

| Age | 1.01 (0.9753–1.045) | 5.84E−01 | 1.009 (0.9747–1.045) | 6.06E−01 |

| Sex | 0.7134 (0.3259–1.562) | 3.98E−01 | 0.7047 (0.3218–1.543) | 3.82E−01 |

Cox proportional hazard model, hazard ratios shown with range in parentheses. SII, systemic immune-inflammation index; WBC, white blood cell. n = 34.

Overall Survival between Risk Groups Is Determined by Regulatory Leukocyte Presence Postchemotherapy

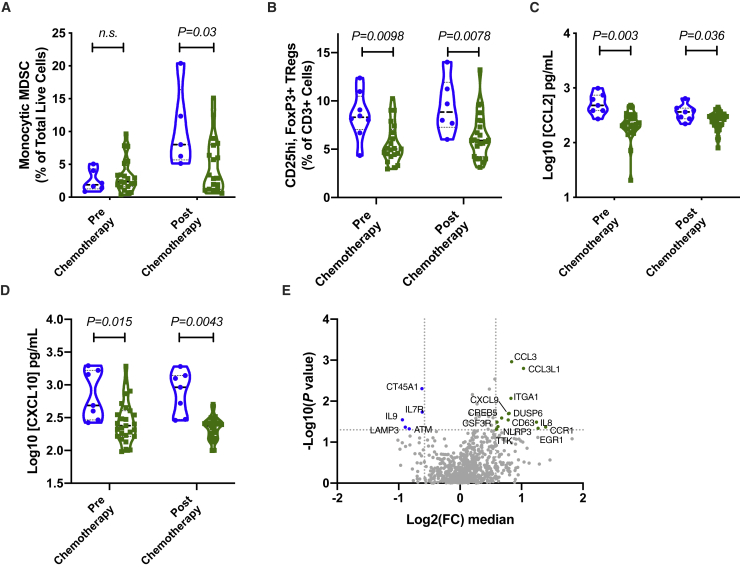

In order to elucidate the underlying mechanisms that determine survival between the high- and low-risk groups, we examined the phenotype of the peripheral, cryopreserved leukocytes at the prechemotherapy and postchemotherapy time points. In particular, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) underwent flow cytometry analysis for the presence of MDSCs and T cell subsets. We employed an automated flow cytometry analysis pipeline, “Flowpip,” to aid in the objective identification of leukocyte subsets, which correlate with clinical outcomes. Flowpip analysis revealed a population of CD11b-positive, CD33-positive, CD14-intermediate, and human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-DR-negative-low cells, which was increased in high-risk individuals postchemotherapy (Figures 2A and S4). This population was confirmed using manual gating techniques to be of mMDSC origin. mMDSC frequencies showed no difference between high- and low-risk groups prechemotherapy. Correspondingly, Flowpip identified a significantly increased regulatory T cell (Treg) frequency in the high-risk group compared to the low-risk group at both pre- and postchemotherapy time points. These findings were again confirmed by manual gating strategies, showing an increase in the median at the later time point (Figures 2B and S5). Plasma cytokine analysis showed that production of regulatory leukocyte-associated chemokines, such as CCL2 and CXCL10, were increased in the high-risk group (Figures 2C and 2D). Comparison of the PBMC transcriptome between the risk groups at the postchemotherapy time point revealed that high-risk individuals had elevated amounts of myeloid-associated transcripts, such as NLRP3, CSF3R, CCL3, and CCL3L1 (Figure 2E).

Figure 2.

Overall Survival between Risk Groups Is Determined by Regulatory Leukocyte Abundance Postchemotherapy

(A) Percentage of monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells (mMDSCs) over total live cells. (B) Percentage of CD25hi, FOXP3+, Tregs over total number of CD3+ T cells. (C) Plasma concentration of CCL2. (D) Plasma concentration of CXCL10. (A–D) n = 34 (n = 7 high risk [blue dots and violin plot], 27 low risk [green dots and violin plot]). Significance calculated using Wilcoxon rank-sum test. (E) Transcriptome profile of PBMCs from postchemotherapy time point. Fold change (FC) was determined by comparison of the median gene expression between the high- and low-risk groups. p value was calculated using Welch’s t test without adjustment.

Combined, these results show that following chemotherapy, high-risk individuals, who did not show a benefit from the chemo- and immunotherapeutic treatment, possessed an increased monocyte frequency relative to lymphocytes, the majority of which was comprised of mMDSCs. The inhibitory component was further augmented by the presence of an increased amount of Tregs, as demonstrated by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). The combination of these inhibitory leukocytes in the high-risk group could establish an environment predictive for a poorer outcome to EBVST infusion.

Overall Survival in Low-Risk Group Is Determined by an Increased Cytotoxic CD8 T Cell Signature

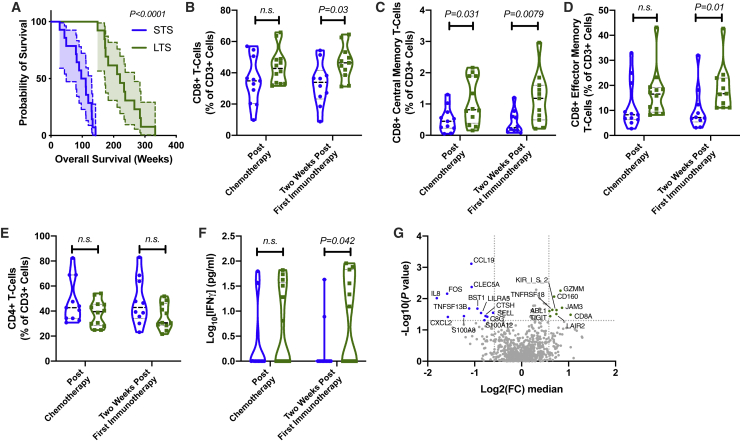

Whereas analysis of the postchemotherapy time point pointed toward a mechanism of resistance to immunotherapy, there were still individuals who possessed a favorable MLR and EBV profile but had a low overall survival. We examined the differences within the low-risk group by dividing individuals into long-term survivors (LTSs) and short-term survivors (STSs), as determined by the median overall survival in the low-risk group (Figure 3A). We focused our analysis on the time points prior to receiving the first EBVST injection (postchemotherapy) and 2 weeks post-first immunotherapy injection. Automated flow cytometry analysis identified that overall CD8 T cells, as well as CD8 effector and central memory subsets, were elevated in the LTS group, 2 weeks post-first immunotherapy. Results were confirmed by manual gating strategies (Figures 3B–3D). No significant differences were detected in CD4 T cell subsets between the groups at the examined time points (Figure 3E).

Figure 3.

Overall Survival in Low-Risk Group Is Determined by an Increased Cytotoxic CD8 T Cell Signature

(A) Survival plot of low-risk individuals, stratified into short-term survivors (STSs) and long-term survivors (LTSs), as determined by the median survival of the low-risk group. Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test, 95% CI shown between dashed lines. (B) Percentage of CD8+ T cells over total number of CD3+ T cells. (C) Percentage of CD8+ central memory T cells (CD45RA−, CCR7+) over total number of CD3+ T cells. (D) Percentage of CD8+ effector memory T cells (CD45RA−, CCR7−) over total number of CD3+ T cells. (E) Percentage of CD4+ T cells over total number of CD3+ T cells. (F) Plasma concentration of IFN-γ. (A–F) n = 27 (n = 14 STS [blue dots and violin plot], 13 LTS [green dots and violin plot]). Significance calculated using Wilcoxon rank-sum test. (G) Transcriptome profile of PBMCs from 2 weeks post-first immunotherapy time point. FC was determined by comparison of the median gene-expression between the STS and LTS groups. p value was calculated using Welch’s t test without adjustment.

2 weeks after the first immunotherapy infusion, there was a significant difference between the LTS and STS groups in terms of IFN-γ production (Figure 3F). Transcriptome analysis of the PBMCs revealed an increased expression of transcripts associated with T cell function in the LTS group, such as GZMM, CD8A, JAM3, and CD160. Conversely, these individuals had lower expression of myeloid-associated transcripts, such as CLEC5A, S100A8, S100A9, LILRA5, and CXCL2.

These findings show that EBVST immunotherapy outcomes in advanced NPC are dependent on several factors: first, that the EBV viral load is decreased postchemotherapy; second, that the patient’s immune system is correctly conditioned following chemotherapy, with a limited expansion of mMDSCs; and third, that a proinflammatory cytotoxic T cell signature persists in the patients throughout the immunotherapy time course.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate that the patient’s response to chemotherapy is integral to successful EBVST immunotherapy. This led to the identification of a series of clinical markers, which when combined, stratify patients by their overall survival. Following chemotherapy, individuals who do not experience a significant increase in regulatory leukocytes possess conditions favorable to receive immunotherapy. 2 weeks post-EBVST administration, those that demonstrate a beneficial response to immunotherapy display an increased memory CD8 T cell response. The identification of biomarkers in ICB has been greatly expanded in recent years but largely center around similar findings—patients who respond to immunotherapy possess one or more of the following factors: increased frequencies of T cells with a greater capacity for effector function, a tumor environment with decreased regulatory components, and/or a tumor with a higher mutational burden.39 Ratio metric analyses offer a simple means of testing for the balance between the modulatory and stimulatory arms of the immune system, where the mechanistic relationship is understood, for example, between activated T cells and antigen-presenting cells. The relationship between lymphocyte and monocyte frequencies was first studied in hematological malignancies but has since been expanded to prognosticate for solid tumors (reviewed in Gu et al.40 and Nishijima et al.41), including NPC.20, 21, 22, 23, 24

With the advance of immunotherapy, either as a single treatment or in combinations across many cancer types, the establishment of predictive and prognostic biomarkers has become increasingly complex. Biomarkers for determining ICB have been mixed in their predictive capability. The more robust examples of biomarkers in predicting outcomes to ICB include microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer.42 Examination of the tissue microenvironment for expression of programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) yields a varied predictive outcome depending on the indication.43 Furthermore, patients who do not express PD-L1 in the tumor have also been shown to respond to therapy.44 The use of a combined assay, examining PD-L1 tumor expression and tumor mutational burden (TMB), resulted in an improved stratification.45 Response to PD-1 therapy was also shown to be dependent on the presence of an increased frequency of peripheral proinflammatory CD14+, CD16−, and HLA-DRhi monocytes before treatment initiation in melanoma patents,46 thus highlighting the importance of a multivariate analysis.

In our study, we showed that chemotherapy treatment yielded differential effects on the patients and their leukocyte profiles. Following the cessation of chemotherapy and the recovery of the patient’s immune system, high-risk individuals experienced an expansion in their percentage of monocytes and mMDSCs. These increased frequencies likely impacted the outcome of EBVST immunotherapy, highlighting the importance of the patient’s base state prior to T cell infusion. Indeed, mMDSCs are actively recruited to the tumor microenvironment, where they can suppress CTL functions.47 The chemotherapeutics used in this study have been demonstrated to be effective against mMDSCs. Gemcitabine has been shown to inhibit mMDSC numbers and function,48,49 as well as increase tumor cross-presentation.50 Carboplatin induces myelotoxicity at maximum tolerated doses.51 When utilized below the maximum tolerated dose, carboplatin mediates immunostimulatory effects by upregulation of MHC, release of proinflammatory cytokines, and downregulation of immune checkpoint inhibitor proteins, resulting in greater CTL tumor infiltration.52,53 The high-risk individuals either possessed an environment, which reduced the efficacy of chemotherapy, or the degree of myeloablation in these patients was so astringent as to cause a massive bone marrow efflux event upon withdrawal. We hypothesize that the more severe rebound of the monocytic cells adversely affected successful receipt of immunotherapy. A similar phenomenon has been reported in the context of human papillomavirus (HPV)-positive cervical cancer.54

The increased severity of an immunosuppressive environment was also evidenced by the elevated levels of CCL2 and CXCL10 in the high-risk group. Both CCL2 and CXCL10 have been associated with increased frequencies of mMDSCs in non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC)55 and are correlated with an adverse prognostic factor of overall survival and distant metastasis-free survival in NPC.56,57 CCL2 has been shown to be a potent mMDSC chemoattractant toward tumor environments.58,59 Within the microenvironment nitration of CCL2 by mMDSC-derived peroxynitrite impaires the infiltration of effector CD8+T cells,60,61 blockade using CCR2 inhibitors can prevent this process.62 CXCL10 has been shown in vitro to possess anti-tumor activities; however, it is highly expressed in NPC, calling into question its pro-T cell attributes in this context.57 Indeed, in the pancreatic cancer setting, increased frequencies of Tregs have been found to be recruited to the tumor site by MDSCs expressing high levels of CXCL10.63

We hypothesize that the chemotherapy regimen in the low-risk group did not permit expansion of suppressive leukocytes, in particular, mMDSCs, compared to the high-risk group. The resultant condition rendered the low-risk patients susceptible to receiving successful EBVST immunotherapy, allowing their T cells to traffic to sites of disease, proliferate, and carry out their cytotoxic function. This mechanism is in contrast to fludarabine and cyclophosphamide (Flu-Cy) regimens, whereby the chemotherapeutic reagents are utilized to create immunological space in the lymphocyte compartment to improve immunotherapy engraftment.64 Here, we propose that the degree of inhibitory compartment removal underpins cellular therapy efficacy. In agreement, NPC clinical trials that employed EBVSTs without prior chemotherapy did not show a therapeutic benefit.16 Furthermore, murine studies have demonstrated the synergistic effect between chemotherapy and immunotherapy in the treatment of solid tumors,65 thus highlighting the importance of both chemotherapeutic conditioning, followed by EBVST immunotherapy in this study.

After the first EBVST immunotherapy infusion memory, CD8 T cell frequencies were found to be significantly increased in LTSs, which was coincident with increased IFN-γ and decreased myeloid chemokine concentrations in the peripheral plasma. Differences in the quality of the EBVST product were previously examined but did not factor into the differences observed in this analysis. The ability of T cells to persist in vivo has been directly correlated with increased response rates both in chimeric antigen receptor T cell (CAR-T) clinical trials66,67 and in adoptive T cell immunotherapy.68,69 Infused products that were derived from naive cells or those with a central memory phenotype exhibited greater in vivo-proliferative capacity and were able to control disease to a greater extent than cells with a terminally differentiated phenotype. In this analysis, we observed that the presence of an increased central memory CD8 T cell profile correlated with overall survival in the LTS group.

Whereas this analysis yields a possible mechanistic explanation for the observed clinical response, our study possess several limitations. One of the more prominent is the limited amount of patients enrolled in the study. This constraint has several downstream impacts, namely, the inability to perform a K-fold cross-validation to assess the predictive accuracy of the biomarkers. Furthermore, it should be stressed that this study was a retrospective exploratory analysis rather than a pre-specified confirmatory analysis. The findings presented here will be tested as part of the exploratory analyses in a multicenter phase III clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02578641), which has ended the recruitment stage.

In summary, we were able to retrospectively determine a patient’s overall survival in response to the combined chemo- and immunotherapy regimens using a series of peripheral blood markers in a multivariate methodology. These results highlight the importance of using multifactorial analyses in immunotherapy trials, where complex cellular interactions define clinical efficacy. We propose a mechanism of action that determines successful cellular immunotherapy, whereby limiting the expansion of mMDSCs is crucial to a patient’s response. This analysis permits rationally informed therapeutic interventions, such as myeloablation, in order to improve EBVST administration.

Materials and Methods

Samples

PBMCs and plasma were collected from patients prior to generate lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCL)s and EBVSTs. Following venesection, patients received chemotherapy consisting of gemcitabine (1,000 mg/m2) and carboplatin (area under the curve [AUC] 2). 2 to 4 weeks postchemotherapy, EBVSTs were administered at a dose of 1 × 108 cells/m2 on weeks 0, 2, 8, 16, 24, and 32. New peripheral blood samples were obtained before commencement of chemotherapy and before each EBVST infusion (Figure S1).17

Serum Cytokine Analysis

Plasma was diluted as described in protocols. A 27-plex Human Cytokine and Chemokine Luminex Multiplex Bead Array Assay Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was used to measure the following cytokines: interleukin (IL)-3, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, IL-9, IL-10, IL-15, IL-17, IL-21, (CXCL10) IP-10, CCL3 (MIP-1α), CCL4 (MIP-1β), CCL20 (MIP-3α), CCL2, IFN-α2, IFN-γ, epidermal growth factor (EGF), fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-2, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), transforming growth factor (TGF)A, CD40L, fractalkine, granulocyte macrophage-colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), granulocyte-CSF (G-CSF), growth-regulated oncogene (GRO), macrophage-derived chemokine (MDC), and eotaxin. Plates were washed using BioTek ELx405 washer (BioTek, USA) and read with Flexmap 3D systems (Luminex, Austin, TX, USA), per the manufacturer’s instructions. Data were analyzed using Bio-Plex Manager 6.0 software with a 5-parameter curve-fitting algorithm applied for standard curve calculations.

Immunophenotyping

PBMCs from frozen patient samples at the time points were stained with two different fluorescently labeled monoclonal antibody panels to determine cell lineage and activation status. The Treg panel included the following: BUV 395 anti-CD25, Pacific Blue anti-FoxP3, BV 711 anti-CD127, fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) anti-CD4, phycoerythrin (PE) anti-CTLA4, PECF594 anti-CD45RA, PECy5 anti-CD3, PECy7 anti-CCR7, and near-infrared LIVE/DEAD cell stain. Tregs were identified using a single cell gate and LIVE/DEAD cell-negative, CD3-positive, CD4-positive, CD25-positive, CD127-negative, FOXP3-positive, and CTLA4-positive gating strategy. The mMDSC panel included the following: BUV 395 anti-CD15, FITC anti-CD16, PE anti-CD33, PECF594 anti-CD34, PECy7 anti-CD11b, allophycocyanin (APC) anti-CD14, APC H7 anti-HLA-DR, and violet LIVE/DEAD cell stain. mMDSCs were identified using a single cell gate and LIVE/DEAD cell-negative, CD16-negative, CD15-negative, CD34-negative, CD11b-positive, CD33-positive, CD14-intermediate, and HLA-DR-negative-low gating strategy. Cells were acquired using an LSR II (BD Biosciences) flow cytometer. Data were analyzed on FACSDiva (BD Biosciences) and FlowJo (Tree Star) software.

RNA Isolation

One hundred thousand thawed PBMCs from time points were pelleted in Eppendorf tubes. Samples subsequently underwent RNA extraction using a QIAGEN RNAEasy Micro Kit. Samples were processed according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. Final elution volume was in 15 μL RNase-free water.

Nanostring Processing

Gene expression was analyzed using a Nanostring PanCancer Immune Panel (XT-CSO-HIP1-12 115000132). 100 ng of each patient sample was prepared, per the manufacturer’s guidelines. Quantification of gene expression was obtained using the nCounter platform; raw counts were processed using nSolver. Raw counts were processed and normalized to the internal positive controls and housekeeping genes using nSolver 4.0 software.

Statistical Analysis

Data were log10(x + 1) transformed. Spearman’s ranked correlation was used, exploring the relationship between clinical parameter (e.g., EBV, MLR) and overall survival. One-way ANOVA was used to investigate the relationship between risk factors and 2-year survival outcome. Cox proportional hazard regression was used for all survival analysis. EBV and MLR cutoffs were selected from one with the best separation of high-risk and low-risk groups out of all of the plausible combinations of observed values between EBV and MLR. A two-tailed significance level of 0.05 was chosen. All analysis was conducted using R (v.3.6, packages of ggplot2, survival70) and Prism.

Flowpip Pipeline

We developed a pipeline to handle the flow cytometry data and identify populations correlating to survival. The pipeline can be broken down into 4 stages: data transformation, batch effect correction, clustering, and statistical analysis.

Data Transformation

First, the cells are sampled so that each donor across all batches has a number of cells. Then, for each marker, data are scaled using the hyperbolic arcsine transformation (arcsinh), which is then standardized.

| (1) |

| (2) |

To get rid of outliers that may affect the quality of the clustering later, we use the hyperbolic tangent function to clip them. A cofactor of 3 is being used.

| (3) |

Batch Effect Correction

The MNNs (mutual nearest neighbors) algorithm was applied to correct for batch effect.71 To fasten the process, correction vectors are computed on a subsample of 20,000 cells. We set the number of neighbors k to 20.

Clustering

Once data have been corrected, we group the cells into clusters using the SLM (smart local moving) algorithm.72 This algorithm belongs to graph clustering algorithms. It builds a graph by having each cell act as a node and being connected to its nearest neighbors through vertices. When building the graph, we connect each cell to its 20 nearest neighbors. To speed up clustering, we use the Annoy library to compute L1 distances (https://github.com/spotify/annoy). We set the number of trees to 50. Forward scatter-height (FSC-H), FSC-width (FSC-W), side scatter (SSC)-H, and SSC-W are discarded when computing distances; this is to avoid redundancy with FSC-area (A) and SSC-A. A sizable number of clusters from SLM may be of very small size. We remove those in which sizes are less than 0.05% of all cells.

Statistical Analysis

We then apply MetaCyto73 to label clusters. Finally, for each cluster, we used the Mann-Whitney rank test to identify significant differences with the null hypothesis, as there is no difference between the stratified groups high- versus low-risk and LTSs versus STSs.

Author Contributions

Conception and Study Design, R.H., A.L., M.P., H.C.T., and J.E.C.; Experimental Execution, R.H., Q.C., L.X.W., and V.B.A.; Automated Pipeline Analysis, D.M.; Bioinformatics Analysis, W.X., R.G., and B.L.; Results Interpretation and Analysis, W.-K.C., W.-W.W., J.W., J.N., R.C., C.L.C., T.S., S.H., and A.C.

Conflicts of Interest

R.H., W.X., D.M., and J.N. are employed by Tessa Therapeutics, which is currently conducting a phase III trial, utilizing a combined chemotherapy and Epstein-Barr virus-specific T cell (EBVST) immunotherapy regimen. W.-W.W., H.C.T., and J.E.C. are consultants for Tessa Therapeutics.

Acknowledgments

This work was enabled with the following grants: Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology (IMCB) Colab Tessa Therapeutics (IAF ICP I1601E0006); Cell Therapy Programme (IAF-PP H18/01/a0/022); National Medical Research Council (NMRC) Clinician-Scientist Individual Research Grant (CS-IRG) (NMRC/CIRG/1352/2013); Clinician Scientist Award-Senior Investigator (CSA-SI) (NMRC/CSASI/0013/2017); and Open Fund-Large Collaborative Grant (OF-LCG) (NMRC/OFLCG/003/2018).

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2020.09.040.

Contributor Information

Han Chong Toh, Email: toh.han.chong@singhealth.com.sg.

John E. Connolly, Email: jeconnolly@imcb.a-star.edu.sg.

Supplemental Information

References

- 1.Chang C.M., Yu K.J., Mbulaiteye S.M., Hildesheim A., Bhatia K. The extent of genetic diversity of Epstein-Barr virus and its geographic and disease patterns: a need for reappraisal. Virus Res. 2009;143:209–221. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wee J., Tan E.H., Tai B.C., Wong H.B., Leong S.S., Tan T., Chua E.T., Yang E., Lee K.M., Fong K.W. Randomized trial of radiotherapy versus concurrent chemoradiotherapy followed by adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with American Joint Committee on Cancer/International Union against cancer stage III and IV nasopharyngeal cancer of the endemic variety. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005;23:6730–6738. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.16.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chia W.K., Wang W.-W., Teo M., Tai W.M., Lim W.T., Tan E.H., Leong S.S., Sun L., Chen J.J., Gottschalk S., Toh H.C. A phase II study evaluating the safety and efficacy of an adenovirus-ΔLMP1-LMP2 transduced dendritic cell vaccine in patients with advanced metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Ann. Oncol. 2012;23:997–1005. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gerdemann U., Christin A.S., Vera J.F., Ramos C.A., Fujita Y., Liu H., Dilloo D., Heslop H.E., Brenner M.K., Rooney C.M., Leen A.M. Nucleofection of DCs to generate Multivirus-specific T cells for prevention or treatment of viral infections in the immunocompromised host. Mol. Ther. 2009;17:1616–1625. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rupec R.A., Jundt F., Rebholz B., Eckelt B., Weindl G., Herzinger T., Flaig M.J., Moosmann S., Plewig G., Dörken B. Stroma-mediated dysregulation of myelopoiesis in mice lacking I κ B α. Immunity. 2005;22:479–491. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jain A., Chia W.K., Toh H.C. Immunotherapy for nasopharyngeal cancer-a review. Linchuang Zhongliuxue Zazhi. 2016;5:22. doi: 10.21037/cco.2016.03.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chow J.C., Ngan R.K., Cheung K.M., Cho W.C. Immunotherapeutic approaches in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Expert. Opin. Biol. Ther. 2019;19:1165–1172. doi: 10.1080/14712598.2019.1650910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Forster M.D., Devlin M.-J. Immune Checkpoint Inhibition in Head and Neck Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2018;8:310. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fang W., Yang Y., Ma Y., Hong S., Lin L., He X., Xiong J., Li P., Zhao H., Huang Y. Camrelizumab (SHR-1210) alone or in combination with gemcitabine plus cisplatin for nasopharyngeal carcinoma: results from two single-arm, phase 1 trials. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:1338–1350. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30495-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Louis C.U., Straathof K., Bollard C.M., Gerken C., Huls M.H., Gresik M.V., Wu M.F., Weiss H.L., Gee A.P., Brenner M.K. Enhancing the in vivo expansion of adoptively transferred EBV-specific CTL with lymphodepleting CD45 monoclonal antibodies in NPC patients. Blood. 2009;113:2442–2450. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-157222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Straathof K.C.M., Bollard C.M., Popat U., Huls M.H., Lopez T., Morriss M.C., Gresik M.V., Gee A.P., Russell H.V., Brenner M.K. Treatment of nasopharyngeal carcinoma with Epstein-Barr virus--specific T lymphocytes. Blood. 2005;105:1898–1904. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Louis C.U., Straathof K., Bollard C.M., Ennamuri S., Gerken C., Lopez T.T., Huls M.H., Sheehan A., Wu M.F., Liu H. Adoptive transfer of EBV-specific T cells results in sustained clinical responses in patients with locoregional nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J. Immunother. 2010;33:983–990. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181f3cbf4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith C., Tsang J., Beagley L., Chua D., Lee V., Li V., Moss D.J., Coman W., Chan K.H., Nicholls J. Effective treatment of metastatic forms of Epstein-Barr virus-associated nasopharyngeal carcinoma with a novel adenovirus-based adoptive immunotherapy. Cancer Res. 2012;72:1116–1125. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee A.Z.E., Tan L.S.Y., Lim C.M. Cellular-based immunotherapy in Epstein-Barr virus induced nasopharyngeal cancer. Oral Oncol. 2018;84:61–70. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2018.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith C., Lee V., Schuessler A., Beagley L., Rehan S., Tsang J., Li V., Tiu R., Smith D., Neller M.A. Pre-emptive and therapeutic adoptive immunotherapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma: Phenotype and effector function of T cells impact on clinical response. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6:e1273311. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2016.1273311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang J., Fogg M., Wirth L.J., Daley H., Ritz J., Posner M.R., Wang F.C., Lorch J.H. Epstein-Barr virus-specific adoptive immunotherapy for recurrent, metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer. 2017;123:2642–2650. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chia W.-K., Teo M., Wang W.-W., Lee B., Ang S.-F., Tai W.-M., Chee C.L., Ng J., Kan R., Lim W.T. Adoptive T-cell transfer and chemotherapy in the first-line treatment of metastatic and/or locally recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Mol. Ther. 2014;22:132–139. doi: 10.1038/mt.2013.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Proctor M.J., McMillan D.C., Morrison D.S., Fletcher C.D., Horgan P.G., Clarke S.J. A derived neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio predicts survival in patients with cancer. Br. J. Cancer. 2012;107:695–699. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Templeton A.J., McNamara M.G., Šeruga B., Vera-Badillo F.E., Aneja P., Ocaña A., Leibowitz-Amit R., Sonpavde G., Knox J.J., Tran B. Prognostic role of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in solid tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2014;106:dju124. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu A., Li H., Zheng Y., Tang M., Li J., Wu H., Zhong W., Gao J., Ou N., Cai Y. Prognostic Significance of Neutrophil to Lymphocyte Ratio, Lymphocyte to Monocyte Ratio, and Platelet to Lymphocyte Ratio in Patients with Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. BioMed Res. Int. 2017;2017:3047802. doi: 10.1155/2017/3047802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yao J.-J., Zhu F.-T., Dong J., Liang Z.-B., Yang L.-W., Chen S.-Y., Zhang W.J., Lawrence W.R., Zhang F., Wang S.Y. Prognostic value of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a large institution-based cohort study from an endemic area. BMC Cancer. 2019;19:37. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-5236-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takenaka Y., Kitamura T., Oya R., Ashida N., Shimizu K., Takemura K., Yamamoto Y., Uno A. Prognostic role of neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio in nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0181478. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang S., Zhao K., Ding X., Jiang H., Lu H. Prognostic Significance of Hematological Markers for Patients with Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma: A Meta-analysis. J. Cancer. 2019;10:2568–2577. doi: 10.7150/jca.26770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chua M.L.K., Tan S.H., Kusumawidjaja G., Shwe M.T.T., Cheah S.L., Fong K.W., Soong Y.L., Wee J.T., Tan T.W. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic marker in locally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A pooled analysis of two randomised controlled trials. Eur. J. Cancer. 2016;67:119–129. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marín Hernández C., Piñero Madrona A., Gil Vázquez P.J., Galindo Fernández P.J., Ruiz Merino G., Alonso Romero J.L., Parrilla Paricio P. Usefulness of lymphocyte-to-monocyte, neutrophil-to-monocyte and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratios as prognostic markers in breast cancer patients treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2018;20:476–483. doi: 10.1007/s12094-017-1732-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li X., Dai D., Chen B., Tang H., Xie X., Wei W. The value of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio for response and prognostic effect of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in solid tumors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Cancer. 2018;9:861–871. doi: 10.7150/jca.23367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goto W., Kashiwagi S., Asano Y., Takada K., Takahashi K., Hatano T., Takashima T., Tomita S., Motomura H., Hirakawa K., Ohira M. Predictive value of lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio in the preoperative setting for progression of patients with breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:1137. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-5051-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mao Y., Chen D., Duan S., Zhao Y., Wu C., Zhu F., Chen C., Chen Y. Prognostic impact of pretreatment lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio in advanced epithelial cancers: a meta-analysis. Cancer Cell Int. 2018;18:201. doi: 10.1186/s12935-018-0698-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Capone M., Giannarelli D., Mallardo D., Madonna G., Festino L., Grimaldi A.M., Vanella V., Simeone E., Paone M., Palmieri G. Baseline neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and derived NLR could predict overall survival in patients with advanced melanoma treated with nivolumab. J. Immunother. Cancer. 2018;6:74. doi: 10.1186/s40425-018-0383-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mann H., Mushtaq M.U., Gonzalez X.A.A., Ahmed A.T., Gupta S. Pre-therapy neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio do not predict survival in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018;36:e15092. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sekine K., Kanda S., Goto Y., Horinouchi H., Fujiwara Y., Yamamoto N., Motoi N., Ohe Y. Change in the lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio is an early surrogate marker of the efficacy of nivolumab monotherapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2018;124:179–188. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2018.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li M., Spakowicz D., Burkart J., Patel S., Husain M., He K., Bertino E.M., Shields P.G., Carbone D.P., Verschraegen C.F. Change in neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio during immunotherapy treatment is a non-linear predictor of patient outcomes in advanced cancers. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2019;145:2541–2546. doi: 10.1007/s00432-019-02982-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sacdalan D.B., Lucero J.A., Sacdalan D.L. Prognostic utility of baseline neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors: a review and meta-analysis. OncoTargets Ther. 2018;11:955–965. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S153290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nishino M., Ramaiya N.H., Hatabu H., Hodi F.S. Monitoring immune-checkpoint blockade: response evaluation and biomarker development. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2017;14:655–668. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rizvi H., Sanchez-Vega F., La K., Chatila W., Jonsson P., Halpenny D., Plodkowski A., Long N., Sauter J.L., Rekhtman N. Molecular Determinants of Response to Anti-Programmed Cell Death (PD)-1 and Anti-Programmed Death-Ligand 1 (PD-L1) Blockade in Patients With Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Profiled With Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018;36:633–641. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.75.3384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lu S., Stein J.E., Rimm D.L., Wang D.W., Bell J.M., Johnson D.B., Sosman J.A., Schalper K.A., Anders R.A., Wang H. Comparison of Biomarker Modalities for Predicting Response to PD-1/PD-L1 Checkpoint Blockade: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5:1195–1204. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leong S.S., Wee J., Rajan S., Toh C.K., Lim W.T., Hee S.W., Tay M.H., Poon D., Tan E.H. Triplet combination of gemcitabine, paclitaxel, and carboplatin followed by maintenance 5-fluorouracil and folinic acid in patients with metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer. 2008;113:1332–1337. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leong S.-S., Wee J., Tay M.H., Toh C.K., Tan S.B., Thng C.H., Foo K.F., Lim W.T., Tan T., Tan E.H. Paclitaxel, carboplatin, and gemcitabine in metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a Phase II trial using a triplet combination. Cancer. 2005;103:569–575. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yarchoan M., Albacker L.A., Hopkins A.C., Montesion M., Murugesan K., Vithayathil T.T., Zaidi N., Azad N.S., Laheru D.A., Frampton G.M., Jaffee E.M. PD-L1 expression and tumor mutational burden are independent biomarkers in most cancers. JCI Insight. 2019;4:e126908. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.126908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gu L., Li H., Chen L., Ma X., Li X., Gao Y., Zhang Y., Xie Y., Zhang X. Prognostic role of lymphocyte to monocyte ratio for patients with cancer: evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2016;7:31926–31942. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nishijima T.F., Muss H.B., Shachar S.S., Tamura K., Takamatsu Y. Prognostic value of lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio in patients with solid tumors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2015;41:971–978. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Le D.T., Uram J.N., Wang H., Bartlett B.R., Kemberling H., Eyring A.D., Skora A.D., Luber B.S., Azad N.S., Laheru D. PD-1 Blockade in Tumors with Mismatch-Repair Deficiency. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;372:2509–2520. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ancevski Hunter K., Socinski M.A., Villaruz L.C. PD-L1 Testing in Guiding Patient Selection for PD-1/PD-L1 Inhibitor Therapy in Lung Cancer. Mol. Diagn. Ther. 2018;22:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s40291-017-0308-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Borghaei H., Paz-Ares L., Horn L., Spigel D.R., Steins M., Ready N.E., Chow L.Q., Vokes E.E., Felip E., Holgado E. Nivolumab versus Docetaxel in Advanced Nonsquamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;373:1627–1639. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alborelli I., Leonards K., Rothschild S.I., Leuenberger L.P., Savic Prince S., Mertz K.D., Poechtrager S., Buess M., Zippelius A., Läubli H. Tumor mutational burden assessed by targeted NGS predicts clinical benefit from immune checkpoint inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer. J. Pathol. 2020;250:19–29. doi: 10.1002/path.5344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Krieg C., Nowicka M., Guglietta S., Schindler S., Hartmann F.J., Weber L.M., Dummer R., Robinson M.D., Levesque M.P., Becher B. High-dimensional single-cell analysis predicts response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy. Nat. Med. 2018;24:144–153. doi: 10.1038/nm.4466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gabrilovich D.I., Nagaraj S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009;9:162–174. doi: 10.1038/nri2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sasso M.S., Lollo G., Pitorre M., Solito S., Pinton L., Valpione S., Bastiat G., Mandruzzato S., Bronte V., Marigo I., Benoit J.P. Low dose gemcitabine-loaded lipid nanocapsules target monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells and potentiate cancer immunotherapy. Biomaterials. 2016;96:47–62. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Le H.K., Graham L., Cha E., Morales J.K., Manjili M.H., Bear H.D. Gemcitabine directly inhibits myeloid derived suppressor cells in BALB/c mice bearing 4T1 mammary carcinoma and augments expansion of T cells from tumor-bearing mice. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2009;9:900–909. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2009.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nowak A.K., Lake R.A., Marzo A.L., Scott B., Heath W.R., Collins E.J., Frelinger J.A., Robinson B.W. Induction of tumor cell apoptosis in vivo increases tumor antigen cross-presentation, cross-priming rather than cross-tolerizing host tumor-specific CD8 T cells. J. Immunol. 2003;170:4905–4913. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.10.4905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yarbro C.H. Carboplatin: a clinical review. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 1989;5(2, Suppl 1):63–69. doi: 10.1016/0749-2081(89)90083-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Galluzzi L., Senovilla L., Zitvogel L., Kroemer G. The secret ally: immunostimulation by anticancer drugs. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2012;11:215–233. doi: 10.1038/nrd3626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lynch T.J., Bondarenko I., Luft A., Serwatowski P., Barlesi F., Chacko R., Sebastian M., Neal J., Lu H., Cuillerot J.M., Reck M. Ipilimumab in combination with paclitaxel and carboplatin as first-line treatment in stage IIIB/IV non-small-cell lung cancer: results from a randomized, double-blind, multicenter phase II study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012;30:2046–2054. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.4032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Welters M.J., van der Sluis T.C., van Meir H., Loof N.M., van Ham V.J., van Duikeren S., Santegoets S.J., Arens R., de Kam M.L., Cohen A.F. Vaccination during myeloid cell depletion by cancer chemotherapy fosters robust T cell responses. Sci. Transl. Med. 2016;8:334ra52. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad8307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yamauchi Y., Safi S., Blattner C., Rathinasamy A., Umansky L., Juenger S., Warth A., Eichhorn M., Muley T., Herth F.J.F. Circulating and Tumor Myeloid-derived Suppressor Cells in Resectable Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018;198:777–787. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201708-1707OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yang J., Lv X., Chen J., Xie C., Xia W., Jiang C., Zeng T., Ye Y., Ke L., Yu Y. CCL2-CCR2 axis promotes metastasis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma by activating ERK1/2-MMP2/9 pathway. Oncotarget. 2016;7:15632–15647. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Teichmann M., Meyer B., Beck A., Niedobitek G. Expression of the interferon-inducible chemokine IP-10 (CXCL10), a chemokine with proposed anti-neoplastic functions, in Hodgkin lymphoma and nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J. Pathol. 2005;206:68–75. doi: 10.1002/path.1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shi H., Zhang J., Han X., Li H., Xie M., Sun Y., Liu W., Ba X., Zeng X. Recruited monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells promote the arrest of tumor cells in the premetastatic niche through an IL-1β-mediated increase in E-selectin expression. Int. J. Cancer. 2017;140:1370–1383. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kumar V., Patel S., Tcyganov E., Gabrilovich D.I. The Nature of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells in the Tumor Microenvironment. Trends Immunol. 2016;37:208–220. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Feng S., Cheng X., Zhang L., Lu X., Chaudhary S., Teng R., Frederickson C., Champion M.M., Zhao R., Cheng L. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells inhibit T cell activation through nitrating LCK in mouse cancers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115:10094–10099. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1800695115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Molon B., Ugel S., Del Pozzo F., Soldani C., Zilio S., Avella D., De Palma A., Mauri P., Monegal A., Rescigno M. Chemokine nitration prevents intratumoral infiltration of antigen-specific T cells. J. Exp. Med. 2011;208:1949–1962. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Flores-Toro J.A., Luo D., Gopinath A., Sarkisian M.R., Campbell J.J., Charo I.F., Singh R., Schall T.J., Datta M., Jain R.K. CCR2 inhibition reduces tumor myeloid cells and unmasks a checkpoint inhibitor effect to slow progression of resistant murine gliomas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2020;117:1129–1138. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1910856117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lunardi S., Lim S.Y., Muschel R.J., Brunner T.B. IP-10/CXCL10 attracts regulatory T cells: Implication for pancreatic cancer. OncoImmunology. 2015;4:e1027473. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1027473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McDonnell A.M., Joost Lesterhuis W., Khong A., Nowak A.K., Lake R.A., Currie A.J., Robinson B.W. Restoration of defective cross-presentation in tumors by gemcitabine. OncoImmunology. 2015;4:e1005501. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1005501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nowak A.K., Robinson B.W.S., Lake R.A. Synergy between chemotherapy and immunotherapy in the treatment of established murine solid tumors. Cancer Res. 2003;63:4490–4496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ghorashian S., Kramer A.M., Onuoha S., Wright G., Bartram J., Richardson R., Albon S.J., Casanovas-Company J., Castro F., Popova B. Enhanced CAR T cell expansion and prolonged persistence in pediatric patients with ALL treated with a low-affinity CD19 CAR. Nat. Med. 2019;25:1408–1414. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0549-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fraietta J.A., Lacey S.F., Orlando E.J., Pruteanu-Malinici I., Gohil M., Lundh S., Boesteanu A.C., Wang Y., O’Connor R.S., Hwang W.T. Determinants of response and resistance to CD19 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Nat. Med. 2018;24:563–571. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0010-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hinrichs C.S., Borman Z.A., Gattinoni L., Yu Z., Burns W.R., Huang J., Klebanoff C.A., Johnson L.A., Kerkar S.P., Yang S. Human effector CD8+ T cells derived from naive rather than memory subsets possess superior traits for adoptive immunotherapy. Blood. 2011;117:808–814. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-286286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Graef P., Buchholz V.R., Stemberger C., Flossdorf M., Henkel L., Schiemann M., Drexler I., Höfer T., Riddell S.R., Busch D.H. Serial transfer of single-cell-derived immunocompetence reveals stemness of CD8(+) central memory T cells. Immunity. 2014;41:116–126. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Therneau T.M., Grambsch P.M. Springer Nature; 2000. Statistics for Biology and Health. Modeling Survival Data: Extending the Cox Model. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Haghverdi L., Lun A.T.L., Morgan M.D., Marioni J.C. Batch effects in single-cell RNA-sequencing data are corrected by matching mutual nearest neighbors. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018;36:421–427. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Waltman L., van Eck N.J. A smart local moving algorithm for large-scale modularity-based community detection. Eur. Phys. J. B. 2013;86:471. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hu Z., Jujjavarapu C., Hughey J.J., Andorf S., Lee H.-C., Gherardini P.F., Spitzer M.H., Thomas C.G., Campbell J., Dunn P. MetaCyto: A Tool for Automated Meta-analysis of Mass and Flow Cytometry Data. Cell Rep. 2018;24:1377–1388. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.