Abstract

A primary challenge in tissue engineering is to recapitulate both the structural and functional features of whole tissues and organs. In vivo, patterning of the body plan and constituent tissues emerges from the carefully orchestrated interactions between the transcriptional programs that give rise to cell types and the mechanical forces that drive the bending, twisting, and extensions critical to morphogenesis. Substantial recent progress in mechanobiology – understanding how mechanics regulate cell behaviors and what cellular machineries are responsible – raises the possibility that one can begin to use these insights to help guide the strategy and design of functional engineered tissues. In this perspective, we review and propose the development of different approaches, from providing appropriate extracellular mechanical cues to interfering with cellular mechanosensing machinery, to aid in controlling cell and tissue structure and function.

Keywords: mechanobiology, tissue engineering, mechanical environment, cytoskeleton and adhesion

Introduction

The physical organization of tissues is central to their ability to perform specialized functions. For example, the highly branched airways of the lung ending in alveoli that are closely juxtaposed to capillary blood vessels is critical for efficient gas exchange; and the ordered nano- and micro-architecture of bone maximizes mechanical strength and stiffness while minimizing weight. In the field of tissue engineering, where the goal is to build human tissues and organs both as therapeutic replacements and as experimental models for translational research, a major challenge is how to replicate tissue structure and function from cells and materials.

Tissues in vivo arrive at their functional adult state through the spatiotemporally coordinated patterning of cellular signaling and mechanical forces (Heisenberg and Bellaïche, 2013). It has become apparent that this coordination emerges largely as a result of deep interactions between biochemical signaling, cytoskeletal dynamics, and forces, each having been shown to modulate the other two (Hannezo and Heisenberg, 2019; Harris et al., 2018). The coordination of biochemical, structural, and mechanical signals is critical not only in development, but also in adult homeostasis, tissue repair, and disease. Recent progress made in the field of mechanobiology has substantially improved our understanding of how mechanical cues influence cell behaviors ranging from cell motility, proliferation, metabolism, differentiation to tissue-level organization and function. Research efforts to understand the molecular basis for these effects have revealed important insights about mechanosensors, transducers and associated signaling pathways.

In this perspective, we examine how such insights offer a diverse range of strategies to provide the appropriate mechanical cues and signaling needed to recapitulate structural, mechanical, and functional features of tissues. In particular, we will discuss top-down approaches to directly recreate physiologic mechanical environments by controlling properties of the extracellular matrix environment and by exerting mechanical forces in culture, as well as bottom-up approaches to directly manipulate mechanosensory pathways. Both approaches will likely be needed in order to induce desired cell behaviors while constructing functional living tissues in vitro.

TOP-DOWN APPROACHES: Manipulation of the extracellular mechanical environment

Adult tissues are complex three-dimensional dynamic structures that are continuously submitted to mechanical forces, and individual cells in those tissues are confined in an extracellular matrix (ECM) through which such forces are transmitted. Even when no external forces are applied, cells themselves apply contractile forces from their actomyosin cytoskeleton that generate tension throughout the tissue. Providing an appropriate mechanical environment for each tissue and application has been a major challenge in engineering tissues. Here, we discuss the use of biomaterial scaffolds in recreating tissue-like mechanical properties for cells, as well as the application of mechanical forces to improve cell and engineered tissue structure and function.

Engineered materials

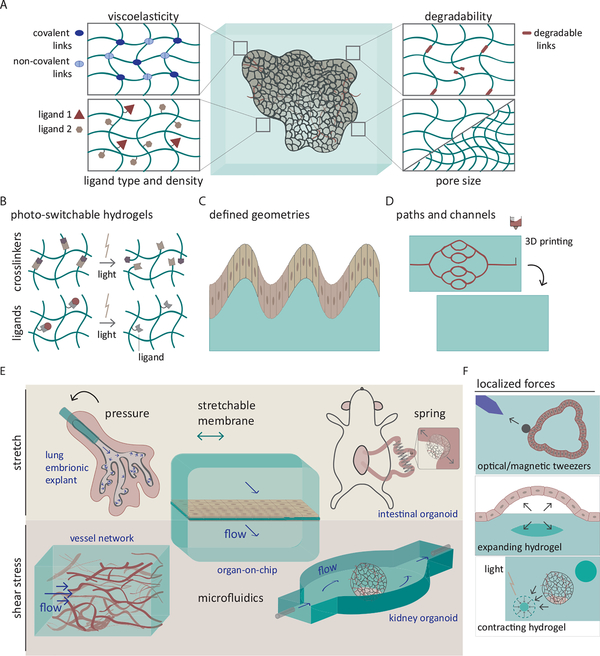

Biomaterials are critical for providing the initial physical scaffolding within which cells and other biomolecules are organized. Both natural ECM polymers (e.g., collagen, fibronectin and elastin) and synthetic materials have been extensively designed and exploited to mimic diverse aspects of native cellular environments, both for studies in mechanobiology as well as applications in tissue engineering (Caliari and Burdick, 2016). ECM-derived polymers provide structural and biochemical properties analogous to those found in natural cellular environments, but are limited due to the difficulty to independently control their different mechanical properties (Caliari and Burdick, 2016). Development of synthetic hydrogels, 3D networks of hydrophilic polymers, has been a critical advance for the mechanobiology field, as fine tuning of individual material properties in a decoupled manner has helped to link specific material properties to cellular behaviors (Figure 1A) (Li et al., 2017a).

Figure 1. Top-down approaches: manipulation of the extracellular mechanical environment.

(A) Biophysical properties of synthetic biomaterials including viscoelasticity, ligand type and density, degradability and pore size can be tailored orthogonally to control mechanosensitive cellular responses and functions in engineered tissues. (B) Mechanical properties as well as biochemical ligand presentation can be dynamically tuned with light. (C) Fabrication of biomaterials with defined physical geometries recapitulate native multicellular structures, such as villus- and crypt-like pattern, to better guide functional tissue development. (D) Complex hierarchical structures such as vascular tree-like channel networks can be created with 3D bioprinting. (E-F) Physiological mechanical forces exerting compressive, tensile or shear stress can be employed to activate mechanoregulatory processes essential for tissue organization and function. (E) Tensile stresses by pressurising from an intraluminal space, stretching the cell-seeded membrane, or using the tissue lengthening apparatus such as compressed spring and shear stress by medium perfusion through vascular network or organoid culture chambers can be exploited to emulate corresponding mechanical cellular environments. (F) Local mechanical forces can be applied in non-invasive and dynamic spatiotemporal manners by optical or magnetic actuation of nanoparticles, ferromagnetic or light-deformable hydrogels.

Inspired from the remarkable spectrum of mechanical properties found in different tissue microenvironments, Discher and colleagues reported in pioneering studies that mesenchymal stem cell specification to neuronal, myogenic, and osteogenic lineages was dictated by matrix stiffnesses mimicking those of the brain, muscle and bone (Engler et al., 2006). Exploiting similar approaches, researchers since have shown how stiffness affects a broad range of cellular behaviors including cell adhesion (Yeung et al., 2005), survival (Wang et al., 2000), proliferation (Klein et al., 2009), migration (Ghosh et al., 2007), cell-cell adhesion (Przybyla et al., 2016) and collective migration (Ng et al., 2012; Sunyer et al., 2016). By modulating the cytoskeleton and adhesion complexes, the stiffness of the ECM modifies the mechanical properties of the cells themselves and their ability to exert forces. This close link between tissue stiffness and function has established an important design principle to use materials that mimic the stiffness of the relevant organ in order to induce appropriate gene expression signatures, maturation, and function of resident cells (Guimarães et al., 2020; Vining and Mooney, 2017). By optimally adjusting substrates, one can create artificial stem cell niches to maintain stemness or induce differentiation toward a desired fate (Vining and Mooney, 2017).

More recent advances have shown that, in addition to stiffness, one can tune many other biomaterial properties such as pore size (Huebsch et al., 2015), ligand type and density (Cruz-Acuña et al., 2017; Enemchukwu et al., 2016; Gjorevski et al., 2016), degradability (Khetan et al., 2013; Trappmann et al., 2017) or fibrous components and their arrangements (Baker et al., 2015), allowing one to recapitulate or create new types of complex cell-ECM interactions. Novel engineered materials can also provide time-dependent viscoelastic responses, and strain stiffening or relaxation found in some extracellular matrices (Chaudhuri et al., 2020). While it is still not well understood how cells sense and respond to some of these different material properties, the opportunities to establish key design principles for engineering cell and tissue function abound. To illustrate, early evidence shows that substrates with the same stiffness, but different stress-relaxation or -stiffening properties differ in their influences on cellular responses and tissue growth (Chaudhuri et al., 2020). How to then use these time-dependent properties in specific settings is only just now being explored. For example, organoids are strongly impacted by mechanical properties of surrounding materials (Cruz-Acuña et al., 2017; Garreta et al., 2019; Gjorevski et al., 2016). However, the hydrogel conditions optimal for early stage organoid expansion appear to be problematic for organoid differentiation and self-organization required at later stages (Gjorevski et al., 2016).

These findings highlight the necessity to develop materials whose properties can be dynamically tuned over time. One possible strategy could take advantage of the cells own ability to remodel and locally modify the material properties of their surroundings. Cells can alter their surrounding matrix by degrading it, depositing their own ECM or by pulling on and deforming a viscoplastic matrix. The main limitation here is that such strategies are irreversible. Another more controlled and direct alternative could be relying on photo-switchable cross-linkers or ligands that would allow for reversible changes in hydrogel’s material properties such as stiffness, degradability, or ECM composition upon light stimulation (Figure 1B) (Rosales and Anseth, 2016). Indeed, hydrogels with photocleavable bonds have proven useful for intestinal organoid development, where a stiffer matrix favors stem cell colony growth, while softening the matrix in a later stage favors crypt formation and size (Hushka et al., 2020). One major advantage of light-based strategies is that it also allows for local modification and patterning of the hydrogel, that would allow for the generation of spatially heterogeneous matrices. Matrices in vivo are not homogeneous and different cell types within tissues and organs may need different ligands and mechanical properties. Also, local modification of the mechanical properties could be exploited to trigger downstream signaling cascades in specific cells and locations. Besides building matrices with spatially patterned properties, researchers have also fabricated matrices with defined physical architectures to control tissue response. Providing the appropriate geometries and structural support can guide physiologically relevant cell-patterns found in the small intestine (Figure 1C) (Nikolaev et al., 2020) or promote tissue vascularization (Figure 1D) (Skylar-Scott et al., 2019). By combining the use of a crypt- and villus-like geometry and the ability to perfuse-out dead cells, Nikolaev et al. are able to improve intestinal organoid cell type diversity and regenerative capacity compared to conventional culture methods. The methods for generating such complex architectures are continually evolving. While traditional casting and foaming techniques have been used for decades, recent advances in 3D bioprinting and photodegradable or photopolymerizable hydrogels are opening new avenues to creating complex structures like specific channel networks or separated compartments within the material (Brassard et al., 2020; Grigoryan et al., 2019).

Mechanical forces

With every breath, step, or blink, cells are being submitted to various types of dynamic or sustained mechanical loads, such as tension, compression, or shear stress, which provide mechanoregulatory signals critical to tissue homeostasis, remodeling and function. To take advantage of these mechanoregulatory systems in building functional tissue constructs, significant effort has been invested in the artificial reproduction of physiological mechanical forces in tissue culture environments.

Compressive and tensile forces have been applied in vitro to 2D substrate-adhered or 3D matrix-embedded cells, most commonly by using stretchable membrane-based devices (Kurpinski et al., 2006) or bioreactors that are designed to apply controlled deformations to cell-embedded scaffolds (Bilodeau and Mantovani, 2006). Owing to the relative simplicity of implementing such approaches in tissue culture systems, many types of loading regimens, such as uniaxial or multiaxial, static or cyclic, have been studied and widely used to improve mechanical properties and structures of load bearing tissues such as cartilage (Lee et al., 2017), tendon (Testa et al., 2017) and ligament (Benhardt and Cosgriff-Hernandez, 2009). In addition, contractile tissues such as skeletal (Powell et al., 2002), smooth (Sharifpoor et al., 2011) and cardiac muscles (Ronaldson-Bouchard et al., 2018) can be trained with cyclic mechanical strain to improve twitch force generation and contractile amplitudes. Application of physiologically relevant levels of mechanical strain has shown to enhance structural organization and functional maturation of developing epithelial tissues (Nelson et al., 2017) or implanted organoids (Figure 1E) (Poling et al., 2018).

As an alternative to deforming tissue constructs using mechanical approaches, synthetic materials have been engineered to deform in response to light, temperature, or electric or magnetic field, thus applying mechanical forces to adhered or embedded cells (Figure 1F) (Cezar et al., 2016; Chandorkar et al., 2019; Sutton et al., 2017). Light-responsive hydrogels are particularly interesting because they offer the possibility of generating local mechanical deformations, allowing for more complex structures to develop. Ferromagnetic hydrogels offer the additional possibility of cytocompatible and remote manipulations even for engineered tissues already implanted in the body (Cezar et al., 2016).

Shear stress exerted by fluid flow is a critical cue for embryonic development, postnatal remodeling and functional homeostasis of the endothelium, and application of physiological shear stress in vitro recapitulates these mechanosensitive events (Hahn and Schwartz, 2009). However, the effects of flow-induced shear are not limited to vascular physiology, as it also influences epithelial monolayer integrity, polarity, multicellular organization and function, as demonstrated in kidney proximal tubule, intestinal epithelial cells (Figure 1E) (Jang et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2012) and lung alveolar epithelial-capillary interface (Huh et al., 2010). Fluid flow also has been recently demonstrated to support organoid development as organoids developed under continuous shear flow displayed improved cellular self-organization, organ-specific marker expression, functional maturation, and improved vascularization (Figure 1E) (Homan et al., 2019; Jin et al., 2018). Despite being an important cue for tissue function, practical incorporation of fluid shear stress in engineered tissues has not been widely explored. Only recently have reports begun to emerge with methods to form in vitro perfusable vascular networks by harnessing vasculogenic self-assembly of endothelial cells (Kim et al., 2013; Song et al., 2020) or endothelialization of hollow structures pre-defined with 3D printed sacrificial materials (Kinstlinger et al., 2020; Miller et al., 2012). Bioprinting of 3D epithelial tubes with accessible inlets and outlets for perfusion (Lin et al., 2019) may pave the way for incorporating shear stress into epithelial tissue engineering. Given the role of shear stress in organizing structures and functions of endothelium and epithelium, it would be reasonable to predict that exposure of engineered vascularized or epithelial tissues with physiologic levels of fluid perfusion would yield tissues that better mimic those observed in vivo.

In contrast to approaches that reproduce the mechanical milieu of living tissues, some researchers have developed mechanical approaches to artificially trigger cellular responses. For instances, indirect mechanical stimulation with high frequency nanoscale vibration (Tsimbouri et al., 2017) or acoustic, ultrasonic waves (Hasanova et al., 2011; Qiu et al., 2019) applied in the cell culture environment can improve osteogenic differentiation and mineralized matrix formation by mesenchymal stem cells, proliferation and matrix deposition by chondrocytes and action potential activation by neural cells. Another example is the utilization of nanoparticles functionalized with peptides, protein ligands, antibodies, and chemical compounds that can bind specific cell surface receptors (Figure1F) (Cho et al., 2012; Mannix et al., 2008), which then can be pulled, vibrated, or clustered using optical, magnetic, electric or acoustic forces to mimic ligand-receptor interactions and trigger receptor signaling (Lee et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2016; Seo et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2005). Thus, classical cell surface receptor signaling pathways could be reconfigured and used as artificial mechanosensitive pathways. Such strategies, if adapted and optimized, could provide remote and non-invasive manipulation with spatiotemporal precision. Hence, these strategies hold tremendous potential for tissue engineering applications to enhance stem cell differentiation, locally program cellular proliferation and apoptosis to steer morphological development, or to trigger growth factor receptor signaling that mediates structural self-organization.

Overall, both the understanding of how the cell mechanical environment affects cell and tissue behavior and the technical advancements needed to reproduce those mechanical microenvironments in vitro are rapidly advancing. However, most of these technical advances are still in early stages and making them broadly accessible and applicable in a high throughput manner will still face many challenges.

BOTTOM-UP APPROACHES I: Manipulation of cytoskeletal and adhesion pathways

Where several have attempted to engineer the environment surrounding the cell with appropriate architectural and mechanical cues (top-down), others have chosen to engineer the cells themselves (referred to herein as bottom-up approaches). Inherently, cells continually send and receive mechanical and chemical cues to maintain balance with its surrounding environment. This balance is cardinal, as perturbations or mutations in this cascade results in developmental and architectural disruptions to tissues and underlie the etiology and progression of many diseases including cardiovascular disease, cancer, stroke, and others (Jaalouk and Lammerding, 2009). Here, we review key examples of how scientists have harnessed the activity of the cell’s mechanotransduction machinery from within to influence the overall behavior and fate of the system.

Cytoskeleton and contractile apparatus

In response to pushing, pulling, and other mechanical forces, tissues can change shape, fold, hold fast, or fracture. These processes all require internal contractile forces that are generated by the actomyosin cytoskeleton. The dynamics of this network are crucial to controlling the organization of cells, their responses to forces, and the collective effects on tissue structure. As such, the contractile machinery is an attractive target to harness control over cell and tissue morphodynamics.

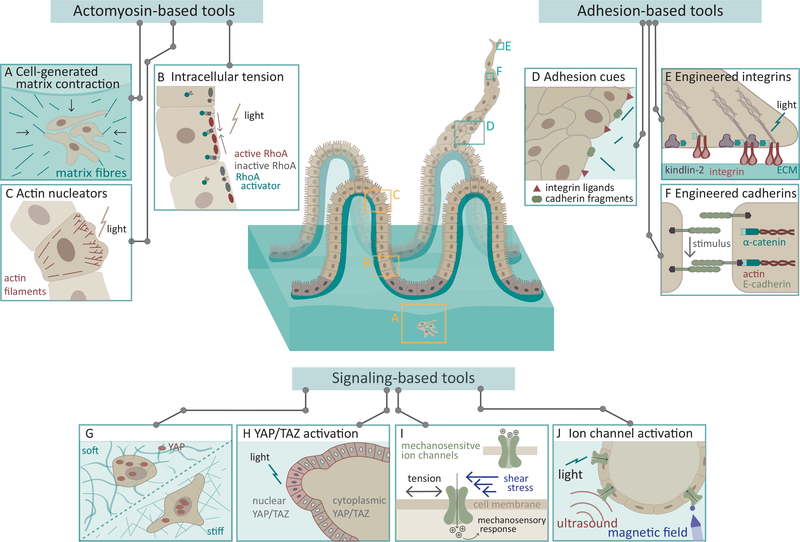

Engineering tissues that fold and bend is a current challenge within the field and an appealing example of where methods to harnessing contractility could be applied. An engineered tissue that bends and/or folds could be formed from an initially planar culture if specific regions of the tissue contract. However, to create controlled bends such as those observed in gastrulation, alveoli of the lung or within the intestinal villi, the spatial location and magnitude of contraction needs to be engineered. Exciting examples of controlled bending have emerged by patterning contractile cells within the ECM (Hughes et al., 2018; Viola et al., 2020). These cells pull on the matrix resulting in collagen alignment and predictable folding patterns (Figure 2A). By altering the density or spacing of cells, invaginations (inward bending), evaginations (outward bending), spirals, ruffles, and other patterns emerge. Combining the autonomous contractile properties of cells with well-developed methods of patterning to achieve these effects highlights a new promising approach. Yet, these studies are just a first step. In vivo tissues fold with significantly better precision, in terms of magnitude and spatial resolution of folding, and in the presence of complex cellular compositions. It remains to be seen how to establish universal methods to achieve such shape-shifting capabilities to engineer desired tissue architectures.

Figure 2. Bottom up approaches: harnessing mechanotransduction machinery and signaling to build tissues.

Engineering complex folding patterns and sprouts are two main challenges facing tissue engineers. Here we depict in the center, gut microvilli, a tissue which emerges from complex folding patterns, as an example tissue that could perhaps be created from contractility (A-C), adhesions (D-F) and signaling (G-F) based tools. Bends within tissues have been demonstrated to emerge from (A) cell’s contracting, pulling on and locally aligning the matrix as well as (B) increases in intracellular tension from inducible constructs such as RhoA. (C) In contrast, protrusions emerge as actin polymerization and branching are induces from actin remodelers such as RAC, CDC42 or WASP. An analogous is to manipulate cadherin and integrins. (D) Scaffolds integrating specific cadherin and integrin bioactive cues promote formation and stabilization of these tissue structures. (E,F) Finer manipulations of these adhesion can be engineered with inducible synthetic constructs. A third approach is to target key mechanosensitive signaling molecules such as (G) YAP/TAZ or (I) Piezo. (H,J) Optogenetic constructs for Yap or Piezo enable spatiotemporal control of activity. (J) Additionally, Piezo channel can be stimulated with sound or magnetic fields.

While patterning cells onto matrices can create the molds necessary for in vitro reconstitution of curved tissues, control over tissue dynamics is lacking. For some tissues, dynamic, multiple sequences of movements may be necessary to generate the functional structure of interest. For instance, actomyosin assembly/disassembly cycles (i.e. actin waves or pulses) are key generators to drive key cell processes such as gastrulation, epithelia tissue contraction, folding, extension and integrity (Coravos et al., 2017). During gastrulation apical constriction and invagination arises from continuous pulses of contractions that draw neighboring cells towards one another followed by a sustained contraction (Martin et al., 2009). Thus, to control tissue shape changes in a physiological manner it is important to tune specific cellular or subcellular regions in a spatially and temporally coordinated fashion. Luckily, engineered control over dynamics of actomyosin contractility may be achievable for such purposes with optogenetic tools. One common approach is to usurp the Rho GTPase pathway by expressing a optogenetic RhoA GEF that localizes to the plasma membrane in response to light stimulus inducing a rapid and local increase in cellular contraction (Figure 2B) (Izquierdo et al., 2018; Valon et al., 2017). Similar tools have also been created to induce local loss of contractility as well. For instance, synthetic constructs enable control over the localization of inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatase, a phosphatase that breaks down PI(4,5)P2, to decouple the actin machinery from the membrane (Guglielmi et al., 2015). Synthetic RhoA GEF or inositol phosphatase show promise as they are sufficient to drive or halt, respectively, apical constriction and subsequent invagination and folding in fly embryos (Guglielmi et al., 2015; Izquierdo et al., 2018) and thus, provide a framework for inducible gain-of-contractility and loss-of contractility tools that could be used to control tissue architecture. Perhaps, tools such as these may provide a means to achieve local tissue constrictions to direct more complex structural folds such as those in the intestinal villi, although the forces and mechanisms that govern these complex structures are only starting to be elucidated (Pérez-González et al., 2020; Roca-Cusachs et al., 2017). However, in cases such as sprouting, local patterns of constriction may not be sufficient to generate the desired structures, as methods to control actin polymerization, nucleation and severing processes are needed. Fortunately, tools for controlling these processes have been developed over the years (Castellano et al., 1999; Nakamura et al., 2020; Stone et al., 2019). For instance, inducible Rac, Cdc42 or, WASP stimulate actin polymerization and cell protrusions and could serve as key initiators of protrusions for sprouting or branching features (Figure 2C) (Castellano et al., 1999; Wu et al., 2009)

These examples highlight tools that can harness the contractile machinery to gain control of tensile properties of a tissue. However, morphogenic changes occur through a conglomerate of mechanical and biological changes. For instance, compressive forces exerted from proliferating cells or the surrounding matrix could also guide tissue buckling and architecture changes (Trushko et al., 2020). Thus, while these tools in principle are amenable to engineering, it is unclear if harnessing the cell’s contractile properties or machine alone will be sufficient to reconstitute many of the structural motifs observed in vivo. Other concerns arise with commandeering contractile machines as contraction affects processes beyond cell tension and shape, to influence cell fate, proliferation, metabolism and Yap-mediated transcription (Bays and DeMali, 2017; Ma et al., 2019; Wozniak and C hen, 2009). While, structural motifs may in theory be created, the cost to cellular behavior or transformation is unknown. Perhaps tools that precisely regulate proliferation or locally compress tissues may be used in conjunction with contractility methods or as an alternative approach to promote tissue folding and bending.

Adhesion Receptors

Adhesion receptors mediate the dynamic connections between cells and the surrounding environment and play pivotal roles in tuning cell adherence and transmission of mechanical and chemical signals. Key among these receptors are the integrins and cadherins, which mediate the connection between a cell and underlying matrix or biomaterial or the connection between two cells, respectively. Yet, the role of cadherins and integrins extends beyond simple mechanical adhesion as these receptors in part regulates cell recognition and sorting, self-organization, boundary formation and maintenance, coordinated cell movements, and cell polarity (Halbleib and Nelson, 2006; Kechagia et al., 2019). Thus, engineering control over adhesion receptor type, number, or strength could offer a new approach to direct tissue function and morphology.

Current platforms applying external forces to cells provide some degree of control over their adhesive properties as these forces can regulate receptor-ligand affinity, the connection between receptor and actin cytoskeleton, and stimulate receptor clustering, all leading to growth and strengthening of cell-matrix and cell-cell adhesion complexes (Kechagia et al., 2019; Yap et al., 2018). However, these mechanical stimuli also activate a myriad of signaling cascades separate from their effects on adhesion receptors (such as Notch receptors, GPCRs, ion channels, and more) (Polacheck et al., 2017; Ranade et al., 2015; Xu et al., 2018). Materials integrating or coated with native proteins, protein fragments or peptides that bind cadherins and integrins are a key method to directly control adhesions (Figure 2D) (Cheng and García, 2013; Cosgrove et al., 2016). These engineered platforms provide better control of engaging specific integrin heterodimers and cadherin types with some demonstration of promoting specific cellular responses such as cell fate regulation (Clark et al., 2020; Cosgrove et al., 2016), proliferation (Gray et al., 2008), cell orientation (Gloerich et al., 2017), collective migration speed and persistence (Borghi et al., 2010), tissue development (Li et al., 2017b; Weber et al., 2007) and regeneration (Cheng and García, 2013; Clark et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2017).

An alternative approach is to utilize synthetic constructs to control adhesions genetically. It has long been appreciated that certain mutations in integrins and cadherins can enhance their affinity (Luo et al., 2009; Tabdili et al., 2012). Similarly, many scaffolding proteins (e.g., talin, kindlin2, or α-catenin) modulate adhesion by guiding either the connection between the scaffolding proteins and receptor or the connection between the receptor and the matrix (Kechagia et al., 2019; Yap et al., 2018). Thus, modulating the expression of such constructs could be used to drive changes in cell adhesion, motility, and mechanics. Recently, optogenetic approaches have been developed to hone integrin- and cadherin-based adhesions with spatiotemporal specificity (Baaske et al., 2019; Liao et al., 2017; Ollech et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2020). In Liao et al, the authors displayed success in using optogenetic induced-binding between integrin αvβ3 and kindlin2 to induce specific and rapid filopodial extensions and angiogenic sprouting in 3D gels (Figure 2E) (Liao et al., 2017). Supporting that stimulating focal adhesion in this manner is sufficient to induce actin protrusions and sprouting. By finely controlling adhesion formation in this way, one could potentially regulate activation of mechanosensory pathways, cell spreading and perhaps more integrated cell behaviors such as individual and collective cell migration and invasion. Analogous strategies could be applied to modulate cadherin-based adhesions. Ollech et al. demonstrated a method by which addition of small, light-controlled molecules induces binding between cadherin and alpha-catenin to create an inducible tether between cadherin and the actin cytoskeleton (Figure 2F) (Ollech et al., 2020). Engineering cadherin connections directly may provide means to directly control angiogenic or epithelial sprouting and development, or stabilize the cadherin connection to induce barrier and structural changes in epithelial and vascular linings.

Here we outlined methods that have been applied or could be applied to manipulate integrin or cadherin-based adhesions to harness control over tissue shape and behavior. While these approaches focus on the precise manipulations of cadherin or integrins, we cannot discard the possibility of cross-talk. Mechanically-driven crosstalk between cadherins and integrins regulates the spatial distribution of these receptors, their signaling intermediates, actomyosin contractility and intracellular forces (Mui et al., 2016). Thus, methods to manipulate adhesions need to be calibrated to preserve the fine balance between traction forces at focal adhesions and intercellular tension at adherens junctions that is crucial for directional collective cell migration and other concerted cell processes (Borghi et al., 2010; Mui et al., 2016).

BOTTOM-UP APPROACHES II: Manipulation of Mechanotransduction Signaling

As discussed above, mechanical signals are first sensed by cell surface receptors such as integrins or cadherins. Force-induced changes in these adhesion receptors trigger and regulate a myriad of signaling networks. Here, we explore the potential utility of two key players – the YAP/TAZ transcriptional regulators and Piezo ion channels – as illustrative examples. With the purpose of improving engineered organs, taking control of these key downstream effectors of mechanical signals provides an appealing alternative strategy to applying forces directly.

YAP/TAZ

The transcriptional co-activators YAP and TAZ are the best-known example of mechanosensitive transcriptional regulators. They belong to the Hippo signaling pathway that regulates tissue growth and organ size among other biological processes (Ma et al., 2019). Over the last decade, it has been shown that several mechanical cues such as substrate stiffness (Figure 2G) (Dupont et al., 2011), mechanical stretch (Benham-Pyle et al., 2015) and shear stress (Nakajima et al., 2017) are able to translocate YAP and TAZ to the nucleus. Recently, there have been examples of how stiffness-dependent stem cell differentiation is often YAP-dependent (Mosqueira et al., 2014; Musah et al., 2014; Totaro et al., 2017). Most importantly, silencing YAP (to mimic a soft substrate) or expressing a constitutively active form of YAP (to mimic a stiff substrate) was sufficient to trigger the expected stemness or cell differentiation state. These results suggest that manipulating YAP/TAZ signaling directly could provide a powerful way to guide mechanotransduction responses without exposing cells to forces.

Inhibiting YAP signals significantly reduces organoid development efficiency in stem cell derived intestinal organoids (Gjorevski et al., 2016; Serra et al., 2019) or human airway organoids (Tan et al., 2017). Given the importance of YAP signaling in stem cell differentiation, manipulating YAP signaling could be used to potentially improve organoid development and complexity. However, overexpressing YAP in all cells in intestinal organoids reduces Paneth cell differentiation and impedes organoid development (Serra et al., 2019). This evidence suggests that to mimic organ development, and to guide cell self-organization, a localized YAP/TAZ activation in space and time may be required. Indeed, during intestinal organoid development, the heterogeneity in YAP nuclear localization between cells drives symmetry-breaking and differentiation into different cell lineages (Serra et al., 2019). This highlights the need for alternative strategies beyond global activation or depletion of YAP/TAZ. One could achieve such capabilities via chemically or light-induced depletion or expression to modulate YAP/TAZ (Figure 2H) (Dowbaj et al., 2020).

Besides cell differentiation, YAP and TAZ are also implicated in cell proliferation and tissue homeostasis (Ma et al., 2019). Controlling cell proliferation (having cell division when more cells are needed or arresting them to avoid overgrowth) is still a major challenge in generating engineered tissues. For example, in many engineered tissue constructs, paracrine signaling from stromal cells is essential for the survival, proper function, and organization of other cell types like epithelial cells in skin tissues, hepatocytes in liver tissues or endothelial cells in vascular networks (Chen et al., 2020; Song et al., 2020). However, over-proliferation and excessive ECM deposition of these stromal cells can stiffen the matrix and trigger a fibrotic response. As fibroblast activation and proliferation has been linked to YAP activation (Haak et al., 2019), time-controlled Yap inhibition in stromal cells could provide a new handle in limiting the stromal fibrotic response and overgrowth while still allowing these cells to support tissue organization and function. However, having proliferation on-demand by manipulating YAP/TAZ signaling still requires a better understanding of the mechanisms linking cell division and YAP/TAZ nuclear translocation, and how to gain such control without the unwanted risks of transformation.

Mechanosensitive Ion Channels

Mechanosensitive ion channels (MSICs) have been gaining increasing attention as key, bona fide force sensors that couple mechanical stimuli to cellular responses by conferring mechanically gated ion flux into the cells (Figure 2I) (Ranade et al., 2015). Among such MSICs, evolutionarily conserved Piezo proteins, Piezo1 and its close homolog Piezo2 show widespread expression in a variety of tissues and cell types. Indeed, mechanosensitive activation of Piezo1 is critical in vascular development, remodeling and homeostasis (Li et al., 2014; Ranade et al., 2014), epithelial cell expansion and crowding (Eisenhoffer et al., 2012), self-renewal and differentiation of stem cells (Segel et al., 2019) and innate immunity (Solis et al., 2019), while Piezo2 plays important roles regulating cell contractility (Pardo-Pastor et al., 2018) and in sensory neurons regulating proprioception and somatosensation (Woo et al., 2015; Zheng et al., 2019). In addition, TRPV ion channels are also expressed across multiple tissues and play mechanosensitive functions that are separate from (Servin-Vences et al., 2017) or cooperating with Piezo1 (Mendoza et al., 2010; O’Conor et al., 2014; Swain et al., 2020).

Several features of these ion channels make them compelling targets for manipulation in the context of serving tissue engineering. First, as these MSICs are membrane-spanning mechanosensors that respond to mechanical cues by signaling to diverse downstream cascade elements, experimental approaches to directly activate these ion channels may provide promising ways to recapitulate at least some aspects of cellular responses to mechanical forces. The use of small molecule agonists provides a simple method for global and uniform activation of target ion channels in the cells. For example, treatment with chemical agonists to Piezo1 or TRPV have been shown to improve bone formation, cartilage tissue formation, and their mechanical properties by mimicking the effects of mechanical loading (Li et al., 2019; O’Conor et al., 2014). Activation of Piezo1 also induces mechanosensitive endothelial responses that closely resemble those experiencing cyclic stretching that fortifies pulmonary vascular barrier (Zhong et al., 2020) or fluid shear stress activating characteristic gene signatures (Caolo et al., 2020) and controlling vascular tone (Wang et al., 2016). Hence, such simple manipulation could substitute mechanical stimuli required for tissue development and function, potentially circumventing the necessity of mechanically stimulating tissues.

Second, their exquisite mechanical sensitivity combined with improved understanding towards protein structures and gating mechanisms provide compelling tools for remote, spatiotemporally localized control for mechanosensitive cellular responses. For instance, ion channels can be activated by fairly low magnitude of mechanical inputs generated by vibrations (Tsimbouri et al., 2017) or ultrasound (Qiu et al., 2019) which is sufficient to activate MSICs but not enough to directly affect other mechanosensory components such as cytoskeleton or adhesion proteins. More importantly, ion channels can be genetically engineered by inserting light-responsive domain, or to have binding specificity with surface-functionalized microbubbles or nanoparticles thereby enabling transduction of remote signals such as light, ultrasound, magnetic fields or low-frequency radio waves into desired MSIC activation (Figure 2J) (Huang et al., 2010; Pan et al., 2018; Stanley et al., 2016; Stanley et al., 2015). In addition, cells can be engineered to express transgenes with synthetic ion-sensitive promoters, that allows further tuning of cellular responses induced by channel modulation (Krawczyk et al., 2020). While yet to be practically implemented for tissue engineering applications, it appears feasible that extension of such approaches could precisely control or even synthetically tune mechanosensitive cellular responses within in vitro or implanted tissue constructs.

Outlook and Present Challenges

Engineering of tissue constructs with physiologically relevant architectures and sizes has long been an unrealized goal of tissue engineering. Here, we propose that advances in our understanding of how cells are regulated by forces, which are known to be critical in driving the structure and function of cells and tissues, can be used to greatly expand the tool box needed to guide tissue engineering into the next era.

While the approaches proposed here focus on manipulating one of several key components in the mechanotransduction machinery—forces, ECM, cytoskeleton, cadherins or integrins, and downstream signaling— we cannot ignore the presence of feedback loops that tie each to affect the others. For instance, adhesion receptor activity is fine-tuned and integrated with cytoskeletal contractility such that adhesion receptors experiencing mechanical forces trigger increased internal contractility associated signaling. Likewise, an increase in cytoskeletal-derived tension leads to robust increase in adhesion receptor clustering and activity and matrix remodeling (Kechagia et al., 2019; Yap et al., 2018). Furthermore, the activity of integrin adhesions and cadherins are integrated as well (Mui et al., 2016). Thus, while we present these methods as tools to target a specific subcomponent, a primary challenge for the field is to understand how these systems cooperate together in order to control specific tissue-forming processes (such as sorting or branching morphogenesis).

Taking cell sorting as one example, it has been long observed that when two cell types are mixed together, over time they are able to find like neighbors and form separate colonies, a phenomenon referred to as cell sorting (Townes and Holtfreter, 1955). The process was thought to be driven by differential adhesions controlling cell-cell contact information; yet, how adhesion specifically directs cell sorting remains unclear. The current dogma is that sorting is not dictated by the biophysical properties of cadherin bonds themselves, but by broader cadherin-dependent differences in intercellular adhesion or cortical tension (Fagotto, 2014; Maître et al., 2012). In vitro, experimentally generated differences in expression levels of cadherins are sufficient to induce cell sorting in simple two cell systems; however, such differences do not lead to the sorting of cells in more complex tissues or in vivo (Ninomiya et al., 2012). If adhesion changes are not enough, then what is driving these effects? One explanation is that the expression of one cadherin type is not sufficient because other cell receptors such as Notch and Eph are involved (Ventrella et al., 2017). These receptors serve as additional layers of signaling that can locally increase or decrease the strength of cadherin-mediated adhesions. In a sorting context, Notch receptors can directly influence the cell adhesive properties (Polacheck et al., 2017; Tossell et al., 2011) or can be engineered for synthetic programs to drive the expression of different levels or types of cadherin receptors (Toda et al., 2018). Synthetic tools such as synNotch may provide a useful tools to better recapitulate the mechanisms for coordinating cells in processes such as sorting. A second receptor to consider are integrins. Cerchiari et al. discovered that cadherin-based cell sorting pattern can be altered by introducing cell-ECM interaction as additional cue (Cerchiari et al., 2015). Hence, tools discussed above to promote integrin activity may influence sorting behaviors as well. Beside the influence of other cell receptors, a second mechanism involves cortical tension to drive boundary formation (Harris, 1976; Krieg et al., 2008; Monier et al., 2010). While adhesions are needed to mechanically couple the cortices of adhering cells at their cell-cell boundaries, cortical tension has been demonstrated as to control cell-cell contact expansion and necessary for sorting (Maître et al., 2012). Thus, tools to manipulate cortical tension could be added to the toolbox to drive sorting, for example using inducible systems to activate Rho or Rac GEFs. Extending from sorting, we can quickly appreciate that tools that enable control of adhesion-based tissue boundary formation may be useful not only for sorting, but also to direct tissue folding, invagination, separation or branching. As an example, Wang et al. were able to recapitulate some features of stratified epithelial branching by combining engineering cadherin adhesions with inducing the formation of a basement membrane layer in epithelial spheroids (Wang et al., 2020).

Another important challenge is the proper guidance of tissue organization and function across different scales. Each organ and tissue has characteristic macro-, micro-scale architectures and hierarchies that are closely linked to the function, but such multiscale features cannot be easily mimicked by application of a single procedure or tool. While tissue engineering has been traditionally attempted to reconstruct the macro-scale architectures of target tissues, recent advances in micro-engineered systems reveal the importance of recreating local environmental cues and micro-scale features in fulfilling the functionality of tissues. For example, one can choose optimal matrix composition and stiffness to meet the bulk tissue properties, but such uniform scaffold may largely overlook local variances that guide organization of micro-scale cellular organization. However, a proper selection of global signals combined with local fine-tuning would be essential.

In conclusion, one can appreciate that the rapid advances in mechanobiology are beginning to point to strategies that could be further developed in order to better control key morphogenetic processes important for engineering tissues. And yet, it is also clear that the insights gained thus far are only a fraction of what will be needed in order to coordinate the multiple adhesion, contractile, and signaling machineries required to direct cells in executing the complex, coordinated maneuvers common in developmental patterning of tissue structures. Regardless, persistent and simultaneous efforts both in uncovering the fundamental mechanisms underlying mechanobiology and in usurping those mechanisms to engineer tissues will be essential in achieving a reality where one can build functional tissues.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (EB00262), the National Science Foundation Cellular Metamaterials Engineering Research Center, and NSF Science and Technology Center for Engineering Mechanobiology. NIH National Research Services Awards T32 EB16652 and F32 HL154664 support J.L.B and EMBO Long-term fellowship (EMBO ALTF 811-2018) support M.U.

Footnotes

A primary challenge in regenerative medicine is to controllably recapitulate the structural and functional features of tissues and organs at multiple length scales. In this Perspective, Kim, Uroz, Bays, and Chen discuss how insights from mechanobiology are offering new strategies to the design and assembly of engineered tissues.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Baaske J, Mühlhäuser WW, Yousefi OS, Zanner S, Radziwill G, Hörner M, Schamel WW, and Weber W (2019). Optogenetic control of integrin-matrix interaction. Communications biology 2, 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker BM, Trappmann B, Wang WY, Sakar MS, Kim IL, Shenoy VB, Burdick JA, and Chen CS (2015). Cell-mediated fibre recruitment drives extracellular matrix mechanosensing in engineered fibrillar microenvironments. Nature materials 14, 1262–1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bays JL, and DeMali KA (2017). It takes energy to resist force. Cell Cycle 16, 1733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benham-Pyle BW, Pruitt BL, and Nelson WJ (2015). Mechanical strain induces E-cadherin–dependent Yap1 and β-catenin activation to drive cell cycle entry. Science 348, 1024–1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benhardt HA, and Cosgriff-Hernandez EM (2009). The role of mechanical loading in ligament tissue engineering. Tissue Engineering Part B: Reviews 15, 467–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilodeau K, and Mantovani D (2006). Bioreactors for tissue engineering: focus on mechanical constraints. A comparative review. Tissue engineering 12, 2367–2383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borghi N, Lowndes M, Maruthamuthu V, Gardel ML, and Nelson WJ (2010). Regulation of cell motile behavior by crosstalk between cadherin-and integrin-mediated adhesions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107, 13324–13329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brassard JA, Nikolaev M, Hübscher T, Hofer M, and Lutolf MP (2020). Recapitulating macro-scale tissue self-organization through organoid bioprinting. Nature Materials, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caliari SR, and Burdick JA (2016). A practical guide to hydrogels for cell culture. Nature methods 13, 405–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caolo V, Debant M, Endesh N, Futers TS, Lichtenstein L, Bartoli F, Parsonage G, Jones EA, and Beech DJ (2020). Shear stress activates ADAM10 sheddase to regulate Notch1 via the Piezo1 force sensor in endothelial cells. Elife 9, e50684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellano F, Montcourrier P, Guillemot J-C, Gouin E, Machesky L, Cossart P, and Chavrier P (1999). Inducible recruitment of Cdc42 or WASP to a cell-surface receptor triggers actin polymerization and filopodium formation. Current Biology 9, 351–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerchiari AE, Garbe JC, Jee NY, Todhunter ME, Broaders KE, Peehl DM, Desai TA, LaBarge MA, Thomson M, and Gartner ZJ (2015). A strategy for tissue self-organization that is robust to cellular heterogeneity and plasticity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112, 2287–2292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cezar CA, Roche ET, Vandenburgh HH, Duda GN, Walsh CJ, and Mooney DJ (2016). Biologic-free mechanically induced muscle regeneration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113, 1534–1539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandorkar Y, Nava AC, Schweizerhof S, Van Dongen M, Haraszti T, Köhler J, Zhang H, Windoffer R, Mourran A, and Möller M (2019). Cellular responses to beating hydrogels to investigate mechanotransduction. Nature communications 10, 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri O, Cooper-White J, Janmey PA, Mooney DJ, and Shenoy VB (2020). Effects of extracellular matrix viscoelasticity on cellular behaviour. Nature 584, 535–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen AX, Chhabra A, Song HHG, Fleming HE, Chen CS, and Bhatia SN (2020). Controlled Apoptosis of Stromal Cells to Engineer Human Microlivers. Advanced Functional Materials, 1910442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng AY, and García AJ (2013). Engineering the matrix microenvironment for cell delivery and engraftment for tissue repair. Current opinion in biotechnology 24, 864–871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho MH, Lee EJ, Son M, Lee J-H, Yoo D, Kim J. w., Park SW, Shin J-S, and Cheon J (2012). A magnetic switch for the control of cell death signalling in in vitro and in vivo systems. Nature materials 11, 1038–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark AY, Martin KE, García JR, Johnson CT, Theriault HS, Han WM, Zhou DW, Botchwey EA, and García AJ (2020). Integrin-specific hydrogels modulate transplanted human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell survival, engraftment, and reparative activities. Nature communications 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coravos JS, Mason FM, and Martin AC (2017). Actomyosin pulsing in tissue integrity maintenance during morphogenesis. Trends in cell biology 27, 276–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove BD, Mui KL, Driscoll TP, Caliari SR, Mehta KD, Assoian RK, Burdick JA, and Mauck RL (2016). N-cadherin adhesive interactions modulate matrix mechanosensing and fate commitment of mesenchymal stem cells. Nature materials 15, 1297–1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Acuña R, Quirós M, Farkas AE, Dedhia PH, Huang S, Siuda D, García-Hernández V, Miller AJ, Spence JR, Nusrat A, and García AJ (2017). Synthetic hydrogels for human intestinal organoid generation and colonic wound repair. Nature cell biology 19, 1326–1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowbaj AM, Jenkins RP, Hahn K, Montagner M, and Sahai EM (2020). An optogenetic method for interrogating YAP1 and TAZ nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling. bioRxiv. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont S, Morsut L, Aragona M, Enzo E, Giulitti S, Cordenonsi M, Zanconato F, Le Digabel J, Forcato M, and Bicciato S (2011). Role of YAP/TAZ in mechanotransduction. Nature 474, 179–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhoffer GT, Loftus PD, Yoshigi M, Otsuna H, Chien C-B, Morcos PA, and Rosenblatt J (2012). Crowding induces live cell extrusion to maintain homeostatic cell numbers in epithelia. Nature 484, 546–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enemchukwu NO, Cruz-Acuña R, Bongiorno T, Johnson CT, García JR, Sulchek T, and García AJ (2016). Synthetic matrices reveal contributions of ECM biophysical and biochemical properties to epithelial morphogenesis. Journal of Cell Biology 212, 113–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engler AJ, Sen S, Sweeney HL, and Discher DE (2006). Matrix elasticity directs stem cell lineage specification. Cell 126, 677–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagotto F (2014). The cellular basis of tissue separation. Development 141, 3303–3318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garreta E, Prado P, Tarantino C, Oria R, Fanlo L, Martí E, Zalvidea D, Trepat X, Roca-Cusachs P, and Gavaldà-Navarro A (2019). Fine tuning the extracellular environment accelerates the derivation of kidney organoids from human pluripotent stem cells. Nature materials 18, 397–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh K, Pan Z, Guan E, Ge S, Liu Y, Nakamura T, Ren X-D, Rafailovich M, and Clark RA (2007). Cell adaptation to a physiologically relevant ECM mimic with different viscoelastic properties. Biomaterials 28, 671–679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gjorevski N, Sachs N, Manfrin A, Giger S, Bragina ME, Ordóñez-Morán P, Clevers H, and Lutolf MP (2016). Designer matrices for intestinal stem cell and organoid culture. Nature 539, 560–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloerich M, Bianchini JM, Siemers KA, Cohen DJ, and Nelson WJ (2017). Cell division orientation is coupled to cell–cell adhesion by the E-cadherin/LGN complex. Nature communications 8, 13996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray DS, Liu WF, Shen CJ, Bhadriraju K, Nelson CM, and Chen CS (2008). Engineering amount of cell–cell contact demonstrates biphasic proliferative regulation through RhoA and the actin cytoskeleton. Experimental cell research 314, 2846–2854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigoryan B, Paulsen SJ, Corbett DC, Sazer DW, Fortin CL, Zaita AJ, Greenfield PT, Calafat NJ, Gounley JP, and Ta AH (2019). Multivascular networks and functional intravascular topologies within biocompatible hydrogels. Science 364, 458–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guglielmi G, Barry JD, Huber W, and De Renzis S (2015). An optogenetic method to modulate cell contractility during tissue morphogenesis. Developmental cell 35, 646–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guimarães CF, Gasperini L, Marques AP, and Reis RL (2020). The stiffness of living tissues and its implications for tissue engineering. Nature Reviews Materials, 1–20.33078077 [Google Scholar]

- Haak AJ, Kostallari E, Sicard D, Ligresti G, Choi KM, Caporarello N, Jones DL, Tan Q, Meridew J, and Espinosa AMD (2019). Selective YAP/TAZ inhibition in fibroblasts via dopamine receptor D1 agonism reverses fibrosis. Science translational medicine 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn C, and Schwartz MA (2009). Mechanotransduction in vascular physiology and atherogenesis. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology 10, 53–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halbleib JM, and Nelson WJ (2006). Cadherins in development: cell adhesion, sorting, and tissue morphogenesis. Genes & development 20, 3199–3214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannezo E, and Heisenberg C-P (2019). Mechanochemical feedback loops in development and disease. Cell 178, 12–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris AK (1976). Is cell sorting caused by differences in the work of intercellular adhesion? A critique of the Steinberg hypothesis. Journal of theoretical biology 61, 267–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris AR, Jreij P, and Fletcher DA (2018). Mechanotransduction by the actin cytoskeleton: converting mechanical stimuli into biochemical signals. Annual review of biophysics 47, 617–631. [Google Scholar]

- Hasanova GI, Noriega SE, Mamedov TG, Thakurta SG, Turner JA, and Subramanian A (2011). The effect of ultrasound stimulation on the gene and protein expression of chondrocytes seeded in chitosan scaffolds. Journal of tissue engineering and regenerative medicine 5, 815–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heisenberg C-P, and Bellaïche Y (2013). Forces in tissue morphogenesis and patterning. Cell 153, 948–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homan KA, Gupta N, Kroll KT, Kolesky DB, Skylar-Scott M, Miyoshi T, Mau D, Valerius MT, Ferrante T, and Bonventre JV (2019). Flow-enhanced vascularization and maturation of kidney organoids in vitro. Nature methods 16, 255–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H, Delikanli S, Zeng H, Ferkey DM, and Pralle A (2010). Remote control of ion channels and neurons through magnetic-field heating of nanoparticles. Nature nanotechnology 5, 602–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huebsch N, Lippens E, Lee K, Mehta M, Koshy ST, Darnell MC, Desai RM, Madl CM, Xu M, and Zhao X (2015). Matrix elasticity of void-forming hydrogels controls transplanted-stem-cell-mediated bone formation. Nature materials 14, 1269–1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes AJ, Miyazaki H, Coyle MC, Zhang J, Laurie MT, Chu D, Vavrušová Z, Schneider RA, Klein OD, and Gartner ZJ (2018). Engineered tissue folding by mechanical compaction of the mesenchyme. Developmental cell 44, 165–178. e166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh D, Matthews BD, Mammoto A, Montoya-Zavala M, Hsin HY, and Ingber DE (2010). Reconstituting organ-level lung functions on a chip. Science 328, 1662–1668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hushka EA, Yavitt FM, Brown TE, Dempsey PJ, and Anseth KS (2020). Relaxation of Extracellular Matrix Forces Directs Crypt Formation and Architecture in Intestinal Organoids. Advanced Healthcare Materials 9, 1901214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izquierdo E, Quinkler T, and De Renzis S (2018). Guided morphogenesis through optogenetic activation of Rho signalling during early Drosophila embryogenesis. Nature communications 9, 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaalouk DE, and Lammerding J (2009). Mechanotransduction gone awry. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology 10, 63–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang K-J, Mehr AP, Hamilton GA, McPartlin LA, Chung S, Suh K-Y, and Ingber DE (2013). Human kidney proximal tubule-on-a-chip for drug transport and nephrotoxicity assessment. Integrative Biology 5, 1119–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y, Kim J, Lee JS, Min S, Kim S, Ahn DH, Kim YG, and Cho SW (2018). Vascularized liver organoids generated using induced hepatic tissue and dynamic liver‐specific microenvironment as a drug testing platform. Advanced Functional Materials 28, 1801954. [Google Scholar]

- Kechagia JZ, Ivaska J, and Roca-Cusachs P (2019). Integrins as biomechanical sensors of the microenvironment. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khetan S, Guvendiren M, Legant WR, Cohen DM, Chen CS, and Burdick JA (2013). Degradation-mediated cellular traction directs stem cell fate in covalently crosslinked three-dimensional hydrogels. Nature materials 12, 458–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HJ, Huh D, Hamilton G, and Ingber DE (2012). Human gut-on-a-chip inhabited by microbial flora that experiences intestinal peristalsis-like motions and flow. Lab on a Chip 12, 2165–2174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Lee H, Chung M, and Jeon NL (2013). Engineering of functional, perfusable 3D microvascular networks on a chip. Lab on a Chip 13, 1489–1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinstlinger IS, Saxton SH, Calderon GA, Ruiz KV, Yalacki DR, Deme PR, Rosenkrantz JE, Louis-Rosenberg JD, Johansson F, and Janson KD (2020). Generation of model tissues with dendritic vascular networks via sacrificial laser-sintered carbohydrate templates. Nature biomedical engineering, 1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein EA, Yin L, Kothapalli D, Castagnino P, Byfield FJ, Xu T, Levental I, Hawthorne E, Janmey PA, and Assoian RK (2009). Cell-cycle control by physiological matrix elasticity and in vivo tissue stiffening. Current biology 19, 1511–1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krawczyk K, Xue S, Buchmann P, Charpin-El-Hamri G, Saxena P, Hussherr M-D, Shao J, Ye H, Xie M, and Fussenegger M (2020). Electrogenetic cellular insulin release for real-time glycemic control in type 1 diabetic mice. Science 368, 993–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieg M, Arboleda-Estudillo Y, Puech P-H, Käfer J, Graner F, Müller D, and Heisenberg C-P (2008). Tensile forces govern germ-layer organization in zebrafish. Nature cell biology 10, 429–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurpinski K, Chu J, Hashi C, and Li S (2006). Anisotropic mechanosensing by mesenchymal stem cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 103, 16095–16100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Kim ES, Cho MH, Son M, Yeon SI, Shin JS, and Cheon J (2010). Artificial control of cell signaling and growth by magnetic nanoparticles. Angewandte Chemie 122, 5834–5838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JK, Huwe LW, Paschos N, Aryaei A, Gegg CA, Hu JC, and Athanasiou KA (2017). Tension stimulation drives tissue formation in scaffold-free systems. Nature materials 16, 864–873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Hou B, Tumova S, Muraki K, Bruns A, Ludlow MJ, Sedo A, Hyman AJ, McKeown L, and Young RS (2014). Piezo1 integration of vascular architecture with physiological force. Nature 515, 279–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Eyckmans J, and Chen CS (2017a). Designer biomaterials for mechanobiology. Nature materials 16, 1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Nih LR, Bachman H, Fei P, Li Y, Nam E, Dimatteo R, Carmichael ST, Barker TH, and Segura T (2017b). Hydrogels with precisely controlled integrin activation dictate vascular patterning and permeability. Nature materials 16, 953–961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Han L, Nookaew I, Mannen E, Silva MJ, Almeida M, and Xiong J (2019). Stimulation of Piezo1 by mechanical signals promotes bone anabolism. Elife 8, e49631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao Z, Kasirer-Friede A, and Shattil SJ (2017). Optogenetic interrogation of integrin αVβ3 function in endothelial cells. Journal of cell science 130, 3532–3541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin NY, Homan KA, Robinson SS, Kolesky DB, Duarte N, Moisan A, and Lewis JA (2019). Renal reabsorption in 3D vascularized proximal tubule models. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116, 5399–5404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Liu Y, Chang Y, Seyf HR, Henry A, Mattheyses AL, Yehl K, Zhang Y, Huang Z, and Salaita K (2016). Nanoscale optomechanical actuators for controlling mechanotransduction in living cells. Nature methods 13, 143–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo B-H, Karanicolas J, Harmacek LD, Baker D, and Springer TA (2009). Rationally designed integrin β3 mutants stabilized in the high affinity conformation. Journal of Biological Chemistry 284, 3917–3924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma S, Meng Z, Chen R, and Guan K-L (2019). The Hippo pathway: biology and pathophysiology. Annual review of biochemistry 88, 577–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maître J-L, Berthoumieux H, Krens SFG, Salbreux G, Jülicher F, Paluch E, and Heisenberg C-P (2012). Adhesion functions in cell sorting by mechanically coupling the cortices of adhering cells. science 338, 253–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannix RJ, Kumar S, Cassiola F, Montoya-Zavala M, Feinstein E, Prentiss M, and Ingber DE (2008). Nanomagnetic actuation of receptor-mediated signal transduction. Nature nanotechnology 3, 36–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin AC, Kaschube M, and Wieschaus EF (2009). Pulsed contractions of an actin–myosin network drive apical constriction. Nature 457, 495–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza SA, Fang J, Gutterman DD, Wilcox DA, Bubolz AH, Li R, Suzuki M, and Zhang DX (2010). TRPV4-mediated endothelial Ca2+ influx and vasodilation in response to shear stress. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 298, H466–H476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JS, Stevens KR, Yang MT, Baker BM, Nguyen D-HT, Cohen DM, Toro E, Chen AA, Galie PA, and Yu X (2012). Rapid casting of patterned vascular networks for perfusable engineered three-dimensional tissues. Nature materials 11, 768–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monier B, Pélissier-Monier A, Brand AH, and Sanson B (2010). An actomyosin-based barrier inhibits cell mixing at compartmental boundaries in Drosophila embryos. Nature cell biology 12, 60–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosqueira D, Pagliari S, Uto K, Ebara M, Romanazzo S, Escobedo-Lucea C, Nakanishi J, Taniguchi A, Franzese O, and Di Nardo P (2014). Hippo pathway effectors control cardiac progenitor cell fate by acting as dynamic sensors of substrate mechanics and nanostructure. ACS nano 8, 2033–2047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mui KL, Chen CS, and Assoian RK (2016). The mechanical regulation of integrin–cadherin crosstalk organizes cells, signaling and forces. Journal of cell science 129, 1093–1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musah S, Wrighton PJ, Zaltsman Y, Zhong X, Zorn S, Parlato MB, Hsiao C, Palecek SP, Chang Q, and Murphy WL (2014). Substratum-induced differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells reveals the coactivator YAP is a potent regulator of neuronal specification. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111, 13805–13810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima H, Yamamoto K, Agarwala S, Terai K, Fukui H, Fukuhara S, Ando K, Miyazaki T, Yokota Y, and Schmelzer E (2017). Flow-dependent endothelial YAP regulation contributes to vessel maintenance. Developmental Cell 40, 523–536. e526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura H, Rho E, Deng D, Razavi S, Matsubayshi HT, and Inoue T (2020). ActuAtor, a molecular tool for generating force in living cells: Controlled deformation of intracellular structures. bioRxiv. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson CM, Gleghorn JP, Pang M-F, Jaslove JM, Goodwin K, Varner VD, Miller E, Radisky DC, and Stone HA (2017). Microfluidic chest cavities reveal that transmural pressure controls the rate of lung development. Development 144, 4328–4335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng MR, Besser A, Danuser G, and Brugge JS (2012). Substrate stiffness regulates cadherin-dependent collective migration through myosin-II contractility. Journal of Cell Biology 199, 545–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaev M, Mitrofanova O, Broguiere N, Geraldo S, Dutta D, Tabata Y, Elci B, Brandenberg N, Kolotuev I, and Gjorevski N (2020). Homeostatic mini-intestines through scaffold-guided organoid morphogenesis. Nature, 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ninomiya H, David R, Damm EW, Fagotto F, Niessen CM, and Winklbauer R (2012). Cadherin-dependent differential cell adhesion in Xenopus causes cell sorting in vitro but not in the embryo. Journal of Cell Science 125, 1877–1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Conor CJ, Leddy HA, Benefield HC, Liedtke WB, and Guilak F (2014). TRPV4-mediated mechanotransduction regulates the metabolic response of chondrocytes to dynamic loading. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111, 1316–1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ollech D, Pflästerer T, Shellard A, Zambarda C, Spatz JP, Marcq P, Mayor R, Wombacher R, and Cavalcanti-Adam EA (2020). An optochemical tool for light-induced dissociation of adherens junctions to control mechanical coupling between cells. Nature communications 11, 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-González C, Ceada G, Greco F, Matejcic M, Gómez-González M, Castro N, Kale S, Álvarez-Varela A, Roca-Cusachs P, and Batlle E (2020). Mechanical compartmentalization of the intestinal organoid enables crypt folding and collective cell migration. bioRxiv. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Y, Yoon S, Sun J, Huang Z, Lee C, Allen M, Wu Y, Chang Y-J, Sadelain M, and Shung KK (2018). Mechanogenetics for the remote and noninvasive control of cancer immunotherapy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115, 992–997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo-Pastor C, Rubio-Moscardo F, Vogel-González M, Serra SA, Afthinos A, Mrkonjic S, Destaing O, Abenza JF, Fernández-Fernández JM, and Trepat X (2018). Piezo2 channel regulates RhoA and actin cytoskeleton to promote cell mechanobiological responses. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115, 1925–1930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polacheck WJ, Kutys ML, Yang J, Eyckmans J, Wu Y, Vasavada H, Hirschi KK, and Chen CS (2017). A non-canonical Notch complex regulates adherens junctions and vascular barrier function. Nature 552, 258–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poling HM, Wu D, Brown N, Baker M, Hausfeld TA, Huynh N, Chaffron S, Dunn JC, Hogan SP, and Wells JM (2018). Mechanically induced development and maturation of human intestinal organoids in vivo. Nature biomedical engineering 2, 429–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell CA, Smiley BL, Mills J, and Vandenburgh HH (2002). Mechanical stimulation improves tissue-engineered human skeletal muscle. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology 283, C1557–C1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Przybyla L, Lakins JN, and Weaver VM (2016). Tissue mechanics orchestrate Wnt-dependent human embryonic stem cell differentiation. Cell stem cell 19, 462–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Z, Guo J, Kala S, Zhu J, Xian Q, Qiu W, Li G, Zhu T, Meng L, and Zhang R (2019). The mechanosensitive ion channel piezo1 significantly mediates in vitro ultrasonic stimulation of neurons. iScience 21, 448–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranade SS, Qiu Z, Woo S-H, Hur SS, Murthy SE, Cahalan SM, Xu J, Mathur J, Bandell M, and Coste B (2014). Piezo1, a mechanically activated ion channel, is required for vascular development in mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111, 10347–10352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranade SS, Syeda R, and Patapoutian A (2015). Mechanically activated ion channels. Neuron 87, 1162–1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roca-Cusachs P, Conte V, and Trepat X (2017). Quantifying forces in cell biology. Nature cell biology 19, 742–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronaldson-Bouchard K, Ma SP, Yeager K, Chen T, Song L, Sirabella D, Morikawa K, Teles D, Yazawa M, and Vunjak-Novakovic G (2018). Advanced maturation of human cardiac tissue grown from pluripotent stem cells. Nature 556, 239–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosales AM, and Anseth KS (2016). The design of reversible hydrogels to capture extracellular matrix dynamics. Nature Reviews Materials 1, 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segel M, Neumann B, Hill MF, Weber IP, Viscomi C, Zhao C, Young A, Agley CC, Thompson AJ, and Gonzalez GA (2019). Niche stiffness underlies the ageing of central nervous system progenitor cells. Nature 573, 130–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo D, Southard KM, Kim J. w., Lee HJ, Farlow J, Lee J. u., Litt DB, Haas T, Alivisatos AP, and Cheon J (2016). A mechanogenetic toolkit for interrogating cell signaling in space and time. Cell 165, 1507–1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serra D, Mayr U, Boni A, Lukonin I, Rempfler M, Meylan LC, Stadler MB, Strnad P, Papasaikas P, and Vischi D (2019). Self-organization and symmetry breaking in intestinal organoid development. Nature 569, 66–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Servin-Vences MR, Moroni M, Lewin GR, and Poole K (2017). Direct measurement of TRPV4 and PIEZO1 activity reveals multiple mechanotransduction pathways in chondrocytes. Elife 6, e21074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharifpoor S, Simmons CA, Labow RS, and Santerre JP (2011). Functional characterization of human coronary artery smooth muscle cells under cyclic mechanical strain in a degradable polyurethane scaffold. Biomaterials 32, 4816–4829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skylar-Scott MA, Uzel SG, Nam LL, Ahrens JH, Truby RL, Damaraju S, and Lewis JA (2019). Biomanufacturing of organ-specific tissues with high cellular density and embedded vascular channels. Science advances 5, eaaw2459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solis AG, Bielecki P, Steach HR, Sharma L, Harman CC, Yun S, de Zoete MR, Warnock JN, To SF, and York AG (2019). Mechanosensation of cyclical force by PIEZO1 is essential for innate immunity. Nature 573, 69–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song HHG, Lammers A, Sundaram S, Rubio L, Chen AX, Li L, Eyckmans J, Bhatia SN, and Chen CS (2020). Transient Support from Fibroblasts is Sufficient to Drive Functional Vascularization in Engineered Tissues. Advanced Functional Materials, 2003777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SA, Kelly L, Latcha KN, Schmidt SF, Yu X, Nectow AR, Sauer J, Dyke JP, Dordick JS, and Friedman JM (2016). Bidirectional electromagnetic control of the hypothalamus regulates feeding and metabolism. Nature 531, 647–650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SA, Sauer J, Kane RS, Dordick JS, and Friedman JM (2015). Remote regulation of glucose homeostasis in mice using genetically encoded nanoparticles. Nature medicine 21, 92–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone OJ, Pankow N, Liu B, Sharma VP, Eddy RJ, Wang H, Putz AT, Teets FD, Kuhlman B, and Condeelis JS (2019). Optogenetic control of cofilin and αTAT in living cells using Z-lock. Nature chemical biology 15, 1183–1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunyer R, Conte V, Escribano J, Elosegui-Artola A, Labernadie A, Valon L, Navajas D, García-Aznar JM, Muñoz JJ, and Roca-Cusachs P (2016). Collective cell durotaxis emerges from long-range intercellular force transmission. Science 353, 1157–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton A, Shirman T, Timonen JV, England GT, Kim P, Kolle M, Ferrante T, Zarzar LD, Strong E, and Aizenberg J (2017). Photothermally triggered actuation of hybrid materials as a new platform for in vitro cell manipulation. Nature communications 8, 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swain SM, Romac JM-J, Shahid RA, Pandol SJ, Liedtke W, Vigna SR, and Liddle RA (2020). TRPV4 channel opening mediates pressure-induced pancreatitis initiated by Piezo1 activation. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 130, 2527–2541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabdili H, Barry AK, Langer MD, Chien Y-H, Shi Q, Lee KJ, Lu S, and Leckband DE (2012). Cadherin point mutations alter cell sorting and modulate GTPase signaling. Journal of cell science 125, 3299–3309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan Q, Choi KM, Sicard D, and Tschumperlin DJ (2017). Human airway organoid engineering as a step toward lung regeneration and disease modeling. Biomaterials 113, 118–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa S, Costantini M, Fornetti E, Bernardini S, Trombetta M, Seliktar D, Cannata S, Rainer A, and Gargioli C (2017). Combination of biochemical and mechanical cues for tendon tissue engineering. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine 21, 2711–2719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toda S, Blauch LR, Tang SK, Morsut L, and Lim WA (2018). Programming self-organizing multicellular structures with synthetic cell-cell signaling. Science 361, 156–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tossell K, Kiecker C, Wizenmann A, Lang E, and Irving C (2011). Notch signalling stabilises boundary formation at the midbrain-hindbrain organiser. Development 138, 3745–3757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]