Abstract

The Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway is aberrantly activated in the majority of colorectal cancer cases due to somatic mutations in the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene. Prohibitin 1 (PHB1) serves pleiotropic cellular functions with dynamic subcellular trafficking facilitating signaling crosstalk between organelles. Nuclear-localized PHB1 is an important regulator of gene transcription. Using mice with inducible intestinal epithelial cell (IEC)-specific deletion of Phb1 (Phb1iΔIEC) and mice with IEC-specific overexpression of Phb1 (Phb1Tg), we demonstrate that IEC-specific PHB1 combats intestinal tumorigenesis in the ApcMin/+ mouse model by inhibiting Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Forced nuclear accumulation of PHB1 in human RKO or SW48 CRC cell lines increased AXIN1 expression and decreased cell viability. PHB1 deficiency in CRC cells decreased AXIN1 expression and increased β-catenin activation that was abolished by XAV939, a pharmacological AXIN stabilizer. These results define a role of PHB1 in inhibiting the Wnt/β-catenin pathway to influence the development of intestinal tumorigenesis. Induction of nuclear PHB1 trafficking provides a novel therapeutic option to influence AXIN1 expression and the β-catenin destruction complex in Wnt-driven intestinal tumorigenesis.

Keywords: adenoma, adenomatous polyposis coli, Axin1, colorectal cancer, intestinal epithelium, mitochondria

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) accounts for 8% of all cancer deaths globally with predicted continued increasing incidence and prevalence worldwide [1, 2]. The majority of CRCs (95%) are adenocarcinomas that originate in the intestinal epithelial cells (IECs) of the colorectal mucosa due to an accumulation of genetic mutations that confer their clonal advantage and expansion [3]. The initiation and progression of CRC is modelled by the “Vogelgram”, which describes the contribution of mutated suppressor genes and oncogenes in the onset and metastasis of cancer cells. Based on this model, normal epithelial LGR5+ stem cells undergo mutations in the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene that involve the formation of a pre-malignant lesion (adenoma) that develops into a malignant lesion (carcinoma) followed by metastasis [4]. The Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway regulates many fundamental cellular functions and is constitutively activated in ~80% of CRC cases due to somatic mutations in the APC or CTNNB1 (encoding β-catenin) genes [5]. The binding of Wnt ligands onto their receptors at the cell surface induces translocation of β-catenin into the nucleus, which in turn activates the T-cell factor (TCF) and lymphoid enhancer factor (LEF) transcription factors to promote the expression of genes such as MYC, AXIN2, FZD, and CCND1 that can drive cellular proliferation. In the absence of Wnt ligands, cytosolic β-catenin is bound by a destruction complex consisting of APC, AXIN, glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β), and casein kinase 1α (CK1α) that facilitates β-catenin phosphorylation and subsequent proteosomal degradation. APC genetic mutants lack binding sites for AXIN and abolish the formation of the β-catenin destruction complex resulting in aberrant Wnt/β-catenin activation [6].

Mitochondria are dynamic organelles that integrate cellular signaling and alter metabolism to match cellular energy demands. Bidirectional regulation between Wnt/β-catenin signaling and mitochondrial retrograde signaling is emerging as a key component in influencing cell fate decisions and tumor progression [7]. Prohibitin 1 (PHB1) is a scaffold protein that regulates mitochondrial function, cell survival, and transcription depending on subcellular localization [8, 9]. Dynamic partitioning of PHB1 between the mitochondria and nucleus of tumor cells has been shown to be signal-dependent and to influence apoptosis [10]. PHB1 is overexpressed in many cancers, including CRC, and is essential to maintain mitochondrial function during tumorigenesis [11]. However, a large number of studies indicate that PHB1 acts as a tumor suppressor and prevents cell proliferation [12]. In CRC, PHB1 expression levels were not associated with prognosis or metastasis [13]. In normal IECs, PHB1 is predominantly localized in the mitochondria [14]. Although plasma membrane-localized PHB1 has been shown to promote CRC cell migration and metastasis [13, 15], the role of nuclear-localized PHB1 in CRC was not previously elucidated. Here, using human CRC cell lines overexpressing nuclear PHB1 and ApcMin/+ mice crossed to mice with inducible IEC-specific deletion of Phb1 (Phb1iΔIEC) or mice with IEC-specific overexpression of Phb1 (Phb1Tg), we demonstrate the role of PHB1 as an inhibitor of Wnt pathway-driven intestinal tumorigenesis.

Results

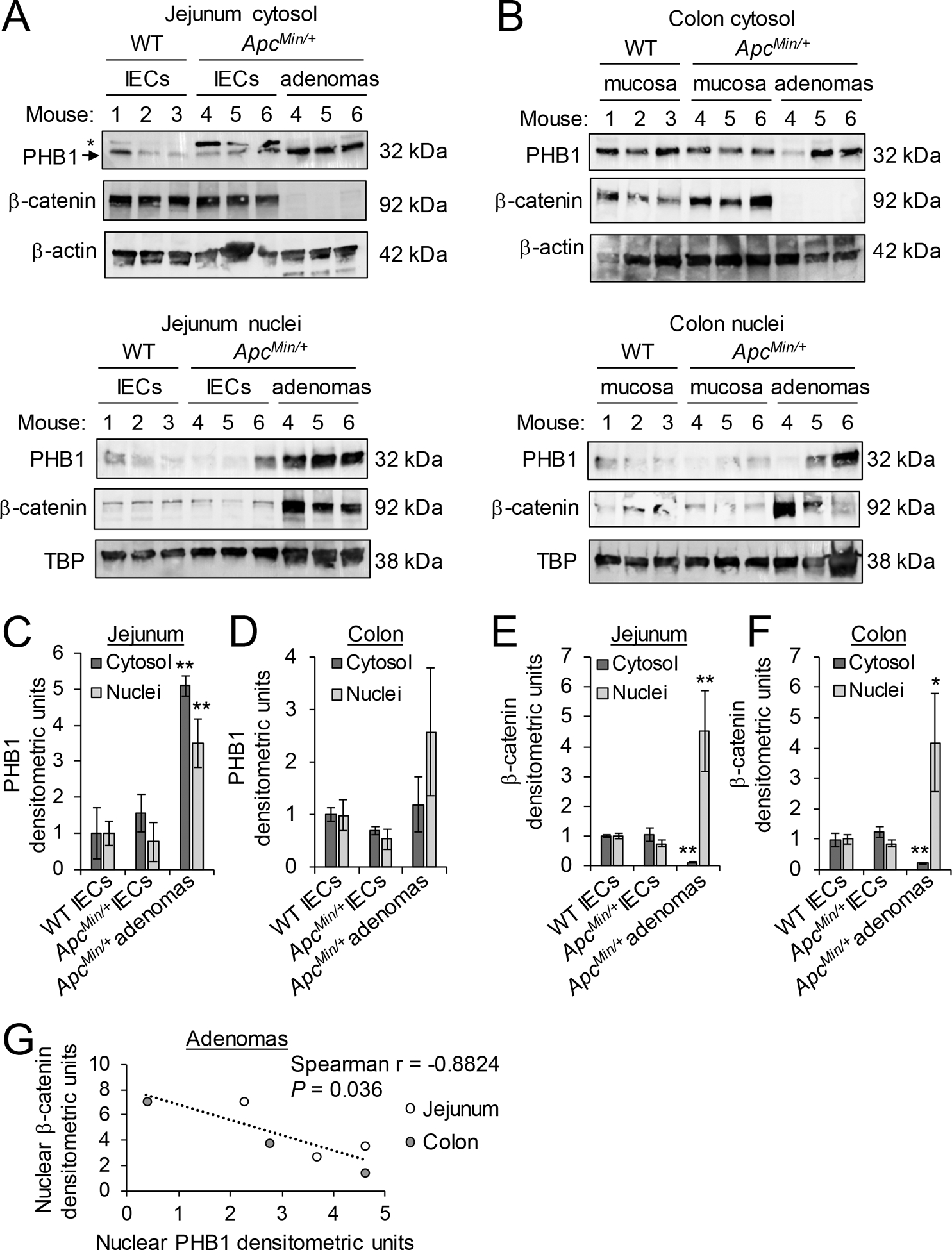

PHB1 expression inversely correlates with β-catenin expression in intestinal and colonic adenomas.

The ApcMin/+ mouse model of intestinal tumorigenesis was used to determine PHB1 nuclear and cytosolic expression in adenomas. In isolated jejunum IECs or colonic mucosa of WT and ApcMin/+ mice, PHB1 was expressed in the cytosol with slight expression in the nuclear fraction (Fig. 1A, B). In isolated jejunum adenomas, PHB1 protein expression was increased in the cytosolic and nuclear fractions (Fig. 1A–C). In ApcMin/+ colon adenomas, PHB1 protein expression was increased in the nuclear fraction in some colon adenomas (Fig. 1B), but across all mice this did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.183; Fig. 1D). Since the ApcMin/+ intestinal tumorigenesis model is driven by robust Wnt/β-catenin overexpression, we also measured β-catenin in the same nuclear and cytosolic extracts. As expected, β-catenin protein expression was increased in nuclear fractions and decreased in cytosolic fractions from isolated jejunum (Fig. 1A, E) and colonic (Fig.1B, F) adenomas, suggesting β-catenin activation. Interestingly, in jejunum and colonic adenomas, PHB1 nuclear expression inversely correlated with β-catenin nuclear expression (Fig. 1G).

Figure 1. PHB1 expression inversely correlates with β-catenin expression in adenomas.

Western blots of nuclear and cytosolic protein fractions of isolated IECs from jejunum (A) or mucosa of colon (B) of wild-type (WT) and ApcMin/+ mice or isolated adenomas from ApcMin/+ mice. *denotes non-specific band in (A), likely family member PHB2. Mean ± SEM of PHB1 western blot densitometry in jejunum (C) or colon (D). Mean ± SEM of β-catenin western blot densitometry in jejunum (E) or colon (F). (G) Spearman rank correlation of western densitometry in nuclear fraction of adenomas. n = 3 mice per group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. WT IECs by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s test.

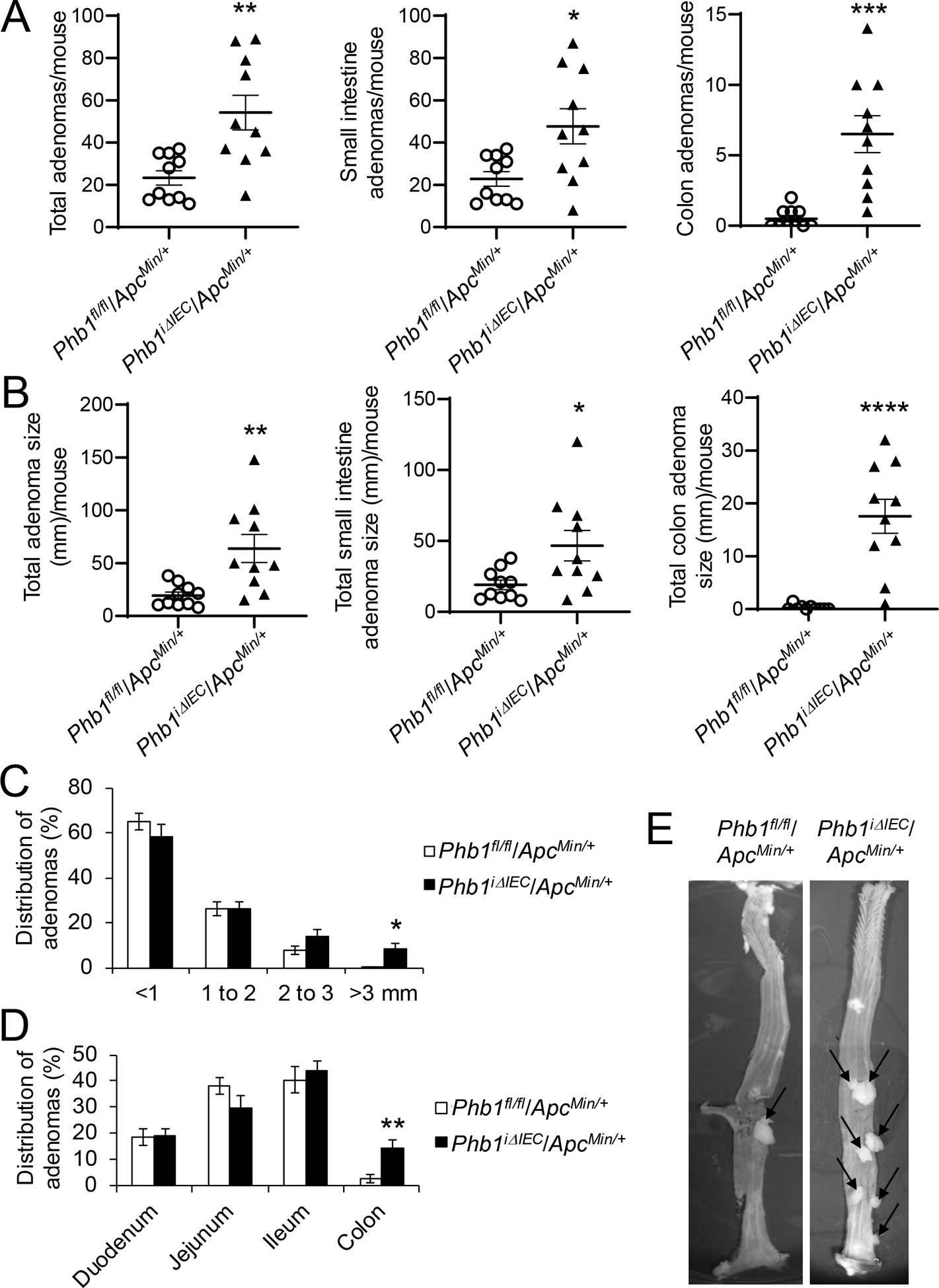

Phb1 deletion in IECs increases intestinal and colonic tumorigenesis in ApcMin/+ mice.

Mice with inducible IEC-specific deletion of Phb1 (Phb1iΔIEC) were recently described [16]. These mice have been characterized up to 12 weeks following deletion of Phb1 without evidence of spontaneous neoplasia in the small intestine or colon. Phb1iΔIEC mice and control Phb1fl/fl mice were crossed to ApcMin/+ mice. PHB1 western blotting verified loss of expression in IECs of PhbiΔIEC/ApcMin/+ mice and no alteration of PHB1 expression in adenomas of Phbfl/fl/ApcMin/+ mice compared to ApcMin/+ mice (Supplementary Fig. S1). PhbiΔIEC/ApcMin/+ mice exhibited increased number of adenomas per mouse in the small intestine and colon compared to Phbfl/fl/ApcMin/+ mice (Fig. 2A). Total adenoma size (mm) per mouse was increased in PhbiΔIEC/ApcMin/+ mice (Fig. 2B) with 8.3% ± 2.2 of adenomas in PhbiΔIEC/ApcMin/+ mice reaching >3 mm in size compared to only 0.3% ± 0.3 of adenomas in Phbfl/fl/ApcMin/+ mice (Fig. 2C). As expected, all PhbiΔIEC/ApcMin/+ and Phbfl/fl/ApcMin/+ mice developed the majority of adenomas in the mid- and distal small intestine with less frequent adenomas in the colon (Fig. 2D). Interestingly, PhbiΔIEC/ApcMin/+ mice exhibited highly significant increases in colonic adenoma numbers and size per mouse (Fig. 2A, B, E) with 14.2% ± 3.0 of total adenomas in PhbiΔIEC/ApcMin/+ mice located in the colon compared to only 2.8% ± 1.6 in Phbfl/fl/ApcMin/+ mice (Fig. 2D). These results suggest that deletion of Phb1 expression in IECs exacerbates the initiation and development of Wnt signaling-driven intestinal tumorigenesis. Adenoma incidence and growth in the colon is greatly increased during Phb1 deletion, an anatomical location normally with infrequent adenomas compared to the small intestine in the ApcMin/+ model [17].

Figure 2. Phb1 deletion in IECs increases intestinal tumorigenesis in ApcMin/+ mice.

(A) Average total adenoma counts per mouse. (B) Average total adenoma size per mouse. (C) Size percent distribution of adenomas. (D) Anatomical percent distribution of adenomas. (E) Representative photographs of colonic adenomas (arrows). n = 10 mice per group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005, ***P < 0.001 by unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t test.

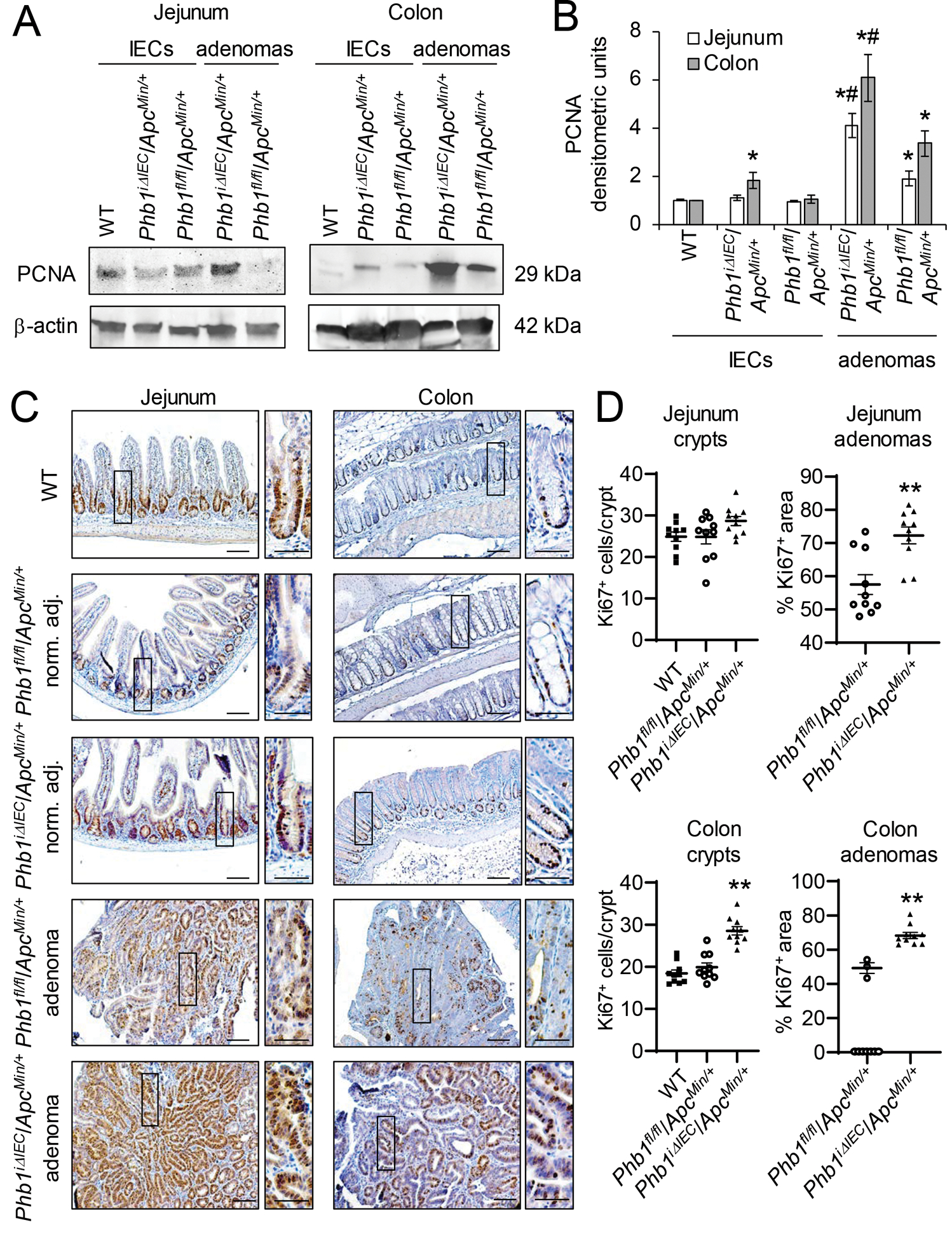

PhbiΔIEC/ApcMin/+ mice exhibit increased proliferation in adenomas and colonic IECs.

To determine whether IEC-specific deletion of Phb1 fosters a pro-survival environment enhancing Wnt-driven tumorigenesis, cell proliferation and apoptosis were measured in Phbfl/fl/ApcMin/+ and PhbiΔIEC/ApcMin/+ mice. Since our previous results demonstrated that PhbiΔIEC mice develop spontaneous intestinal inflammation in the ileum while sparing more proximal segments of small intestine or colon [16], we assayed anatomical locations in which inflammation does not develop at this time point in these mice (jejunum and colon). PCNA, a marker of proliferation, was most highly expressed in jejunum and colon adenomas from Phbfl/fl/ApcMin/+ mice compared to PhbiΔIEC/ApcMin/+ adenomas (Fig. 3A, B). Isolated IECs from colon, but not jejunum, of PhbiΔIEC/ApcMin/+ mice exhibited increased PCNA expression compared to IECs of Phbfl/fl/ApcMin/+ mice, but this did not reach the increased PCNA expression found in colonic adenomas (Fig. 3A, B). Consistent with these results, Ki67 immunohistochemical staining demonstrated increased Ki67+ cells in jejunum and colonic adenomas of PhbiΔIEC/ApcMin/+ mice compared to adenomas of Phbfl/fl/ApcMin/+ mice (Fig. 3C, D and Supplementary Fig. S2). In non-tumor regions, Ki67+-cells were increased in colonic crypts, but not jejunum crypts, of PhbiΔIEC/ApcMin/+ (Fig. 3D). As a marker of apoptosis, cleaved Caspase 3 expression was decreased in jejunum and colonic adenomas in both PhbiΔIEC/ApcMin/+ and Phbfl/fl/ApcMin/+ mice compared to isolated normal IECs, but there was no further change in cleaved Caspase 3 expression by Phb1 deletion (Supplementary Fig. S3A, B). TUNEL immunofluorescent staining demonstrated similar TUNEL+ expression in adenomas from PhbiΔIEC/ApcMin/+ and Phbfl/fl/ApcMin/+ mice (Supplementary Fig. S3C). These results suggest that loss of Phb1 expression in IECs enhances proliferation in adenomas and colonic IECs without affecting apoptosis.

Figure 3. PhbiΔIEC/ApcMin/+ mice exhibit increased proliferation in adenomas and colonic IECs.

(A) Representative western blots of PCNA (marker of proliferation) in isolated IECs or adenomas from Phbfl/fl/ApcMin/+ or PhbiΔIEC/ApcMin/+ mice compared to IECs from wild-type (WT) mice. (B) Mean ± SEM of PCNA normalized to β-actin densitometric units. n = 3 (WT) or 6 mice (all other groups). *P < 0.05 vs Phbfl/fl/ApcMin/+ IECs, #P < 0.05 vs Phbfl/fl/ApcMin/+ adenomas by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s test. (C) Ki67 immunohistochemistry staining in adenomas or normal adjacent tissue. Scale bars: 100 μm; boxed pullouts: 50 μm. (D) Ki67+ cells/crypt and percentage of the area of Ki67 immunostaining in adenomas per mouse ± SEM. Mice without adenomas present in colon sections are plotted as 0 on the X-axis. n =10 mice per group. **P < 0.01 vs Phbfl/fl/ApcMin/+ by unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t test.

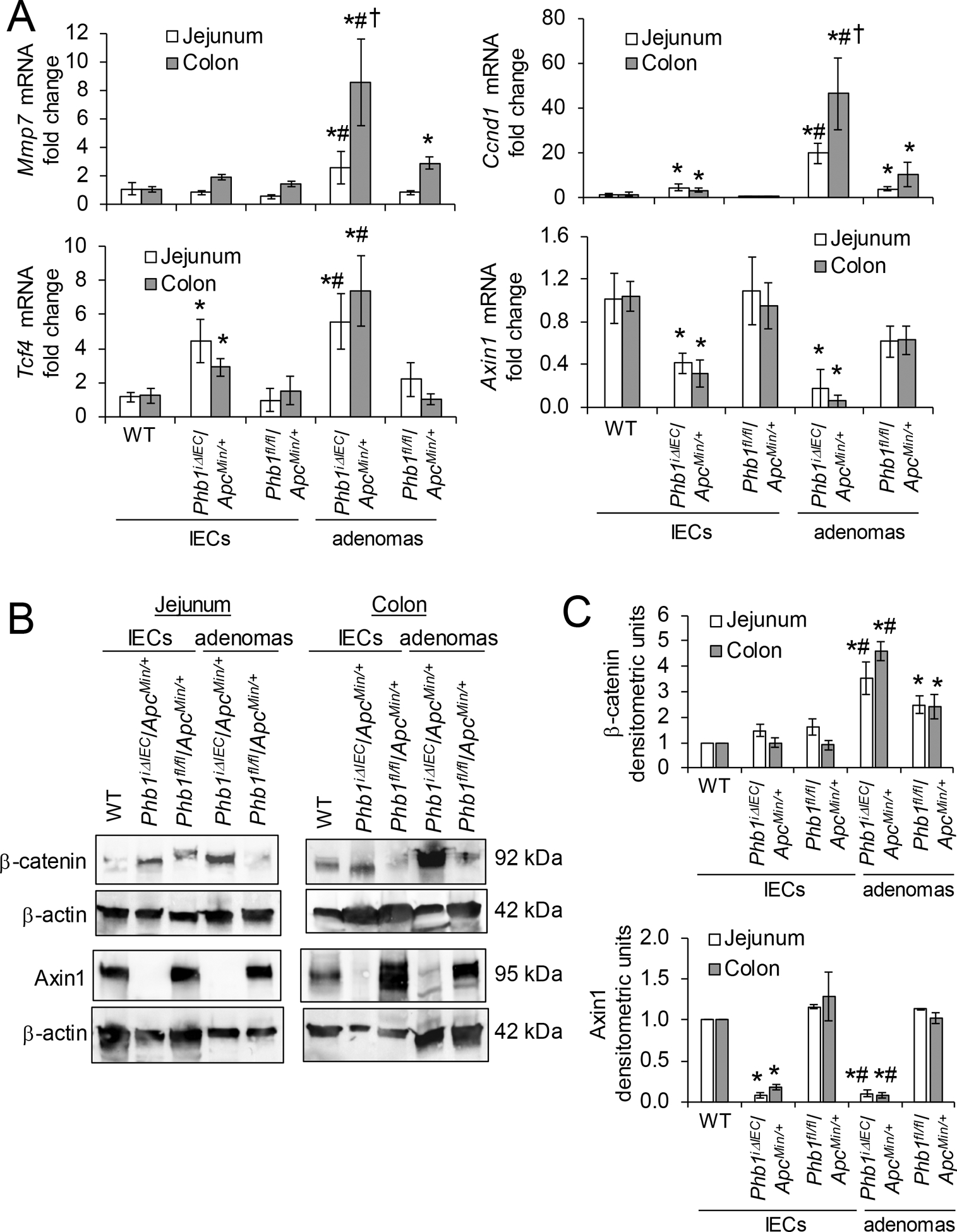

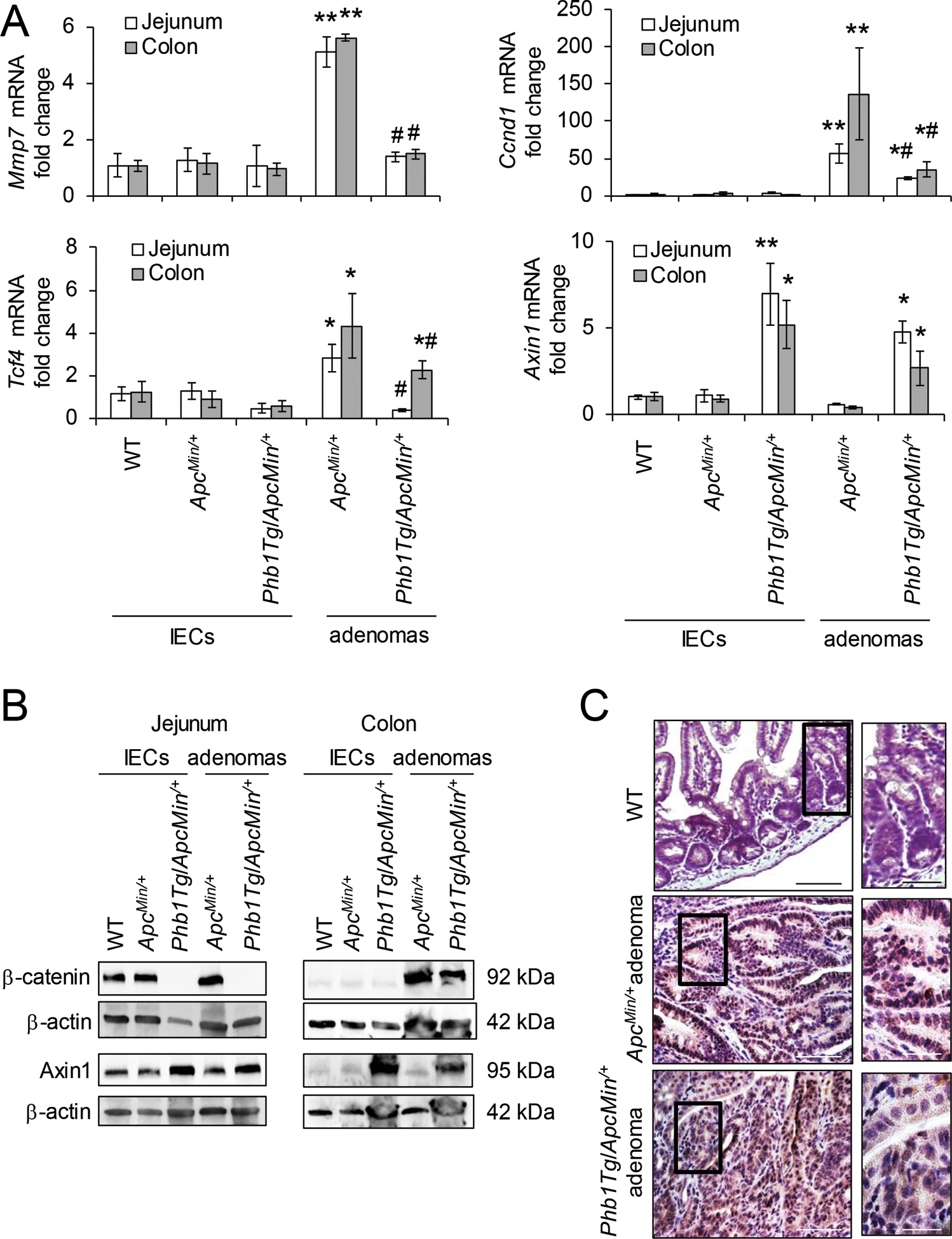

β-catenin activation is increased in PhbiΔIEC mice.

We next measured Wnt/β-catenin activation in PhbiΔIEC/ApcMin/+ and Phbfl/fl/ApcMin/+ mice. During Phb1 deletion, adenomas from both jejunum and colon exhibited increased expression of Wnt target genes Mmp7, Ccnd1, and Tcf4 compared to adenomas from Phbfl/fl/ApcMin/+ mice (Fig. 4A). Highest expression of Mmp7 and Ccnd1 was demonstrated in colon adenomas from PhbiΔIEC/ApcMin/+ mice, with colon adenomas expression significantly increased compared to jejunum adenomas during Phb1 deletion (Fig. 4A). In addition, Ccnd1 and Tcf4 were increased in Phb1 deficient IECs isolated from jejunum and colon (Fig. 4A). β-catenin protein was highly abundant in isolated adenomas from PhbiΔIEC/ApcMin/+ mice compared to Phbfl/fl/ApcMin/+ mice (Fig. 4B, C). AXIN1, the core molecule and limiting component of the β-catenin degradation complex, was recently shown to possess a putative PHB1 binding domain in the promoter region [18]. Axin1 mRNA (Fig. 4A) and protein (Fig. 4B, C) expression was concomitantly decreased in PhbiΔIEC/ApcMin/+ IECs and adenomas compared to Phbfl/fl/ApcMin/+ mice.

Figure 4. β-catenin activation is increased in PhbiΔIEC mice.

(A) Mean ± SEM of relative mRNA expression in isolated IECs or isolated adenomas. (B) Representative western blots of isolated colonic IECs or adenomas. (C) Mean ± SEM of β-catenin or Axin1 normalized to β-actin densitometric units. n = 3 (WT) or 6 mice (all other groups). *P < 0.05 vs Phbfl/fl/ApcMin/+ IECs, #P < 0.05 vs Phbfl/fl/ApcMin/+ adenomas, †P < 0.05 vs PhbiΔIEC/ApcMin/+ jejunum adenomas by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s test.

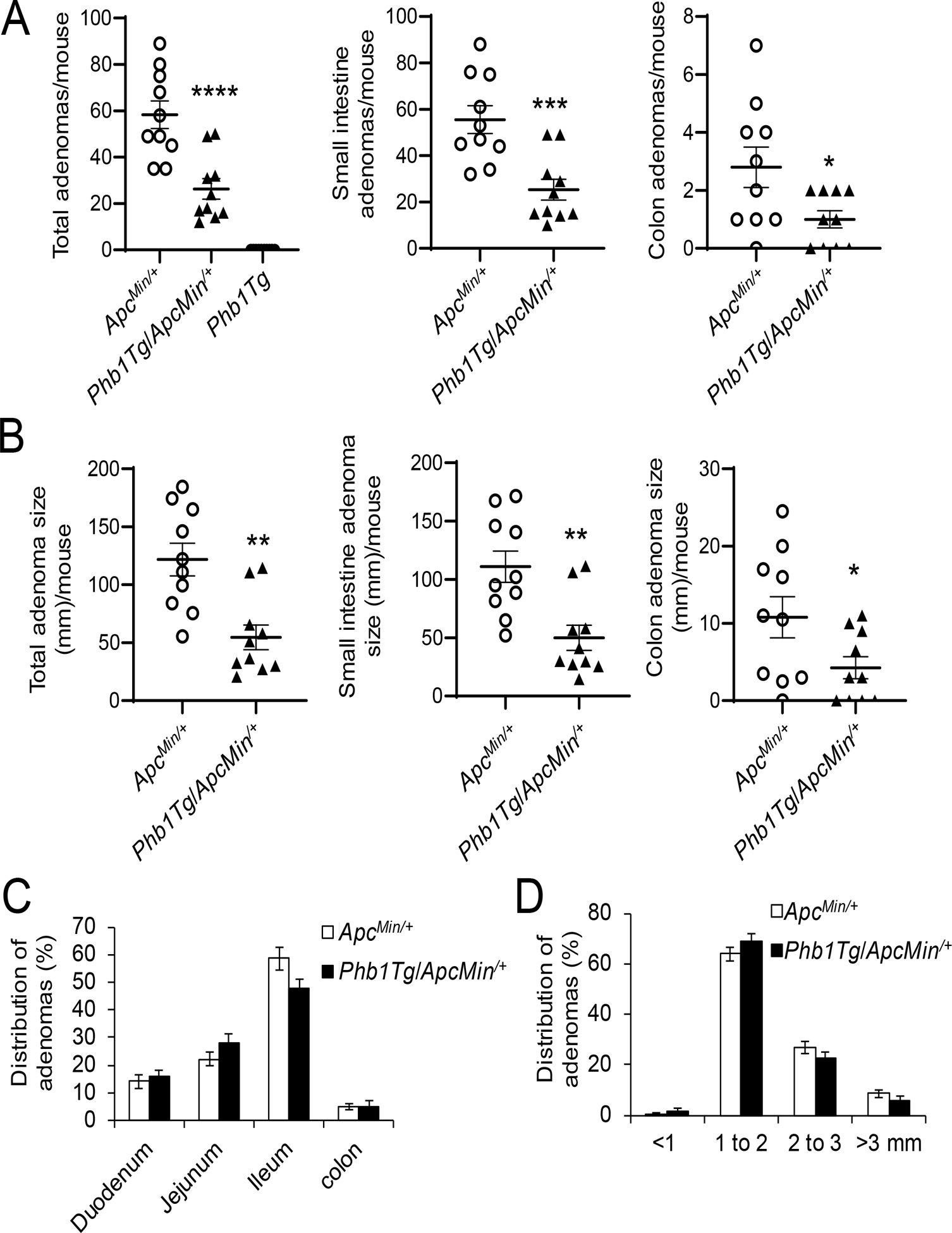

IEC-specific Phb1 overexpression ameliorates intestinal tumorigenesis in ApcMin/+ mice.

To confirm the role of PHB1 in intestinal tumorigenesis in ApcMin/+ mice, mice with IEC-specific overexpression of Phb1 driven by the Villin promoter (Phb1Tg mice) [19] were crossed to ApcMin/+ mice. Phb1Tg/ApcMin/+ mice developed fewer adenomas per mouse in the small intestine and colon compared to ApcMin/+ mice (Fig. 5A). Since PHB1 is overexpressed in various types of cancers [20] and has been reported as increased in CRC [21, 22], Phb1Tg mice were assessed for adenoma formation alongside ApcMin/+ and Phb1Tg/ApcMin/+ mice. No adenomas were evident in Phb1Tg mice (Fig. 5A), suggesting that PHB1 overexpression in IECs is not sufficient to initiate intestinal tumorigenesis. Total adenoma size (mm) per mouse in the small intestine and colon was decreased in Phb1Tg/ApcMin/+ mice compared to ApcMin/+ mice (Fig. 5B). PHB1 overexpression did not alter the anatomical location of adenomas (Fig. 5C) or the size distribution of adenomas, with the majority being 1–2 mm in size (Fig. 5D).

Figure 5. IEC-specific Phb1 overexpression ameliorates intestinal tumorigenesis in ApcMin/+ mice.

(A) Average total adenoma counts per mouse. (B) Average total adenoma size per mouse. (C) Anatomical percent distribution of adenomas. (D) Size percent distribution of adenomas. n =10 mice per group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005, ***P < 0.001 by unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t test.

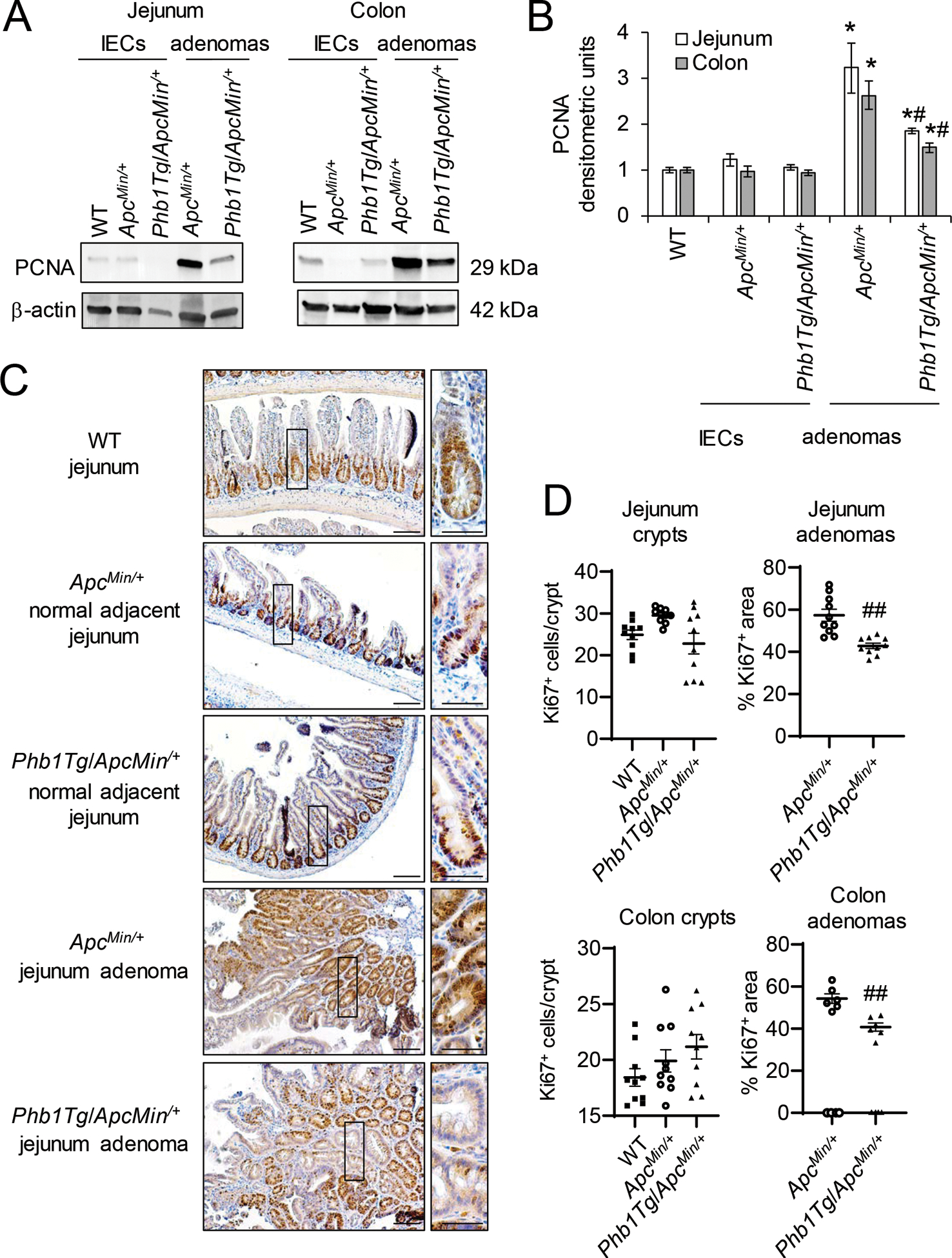

Phb1Tg/ApcMin/+ mice exhibit decreased proliferation, increased apoptosis, and decreased β-catenin activation in intestinal adenomas.

As a measure of proliferation, PCNA protein expression was increased in jejunum and colon adenomas in both ApcMin/+ and Phb1Tg/ApcMin/+ mice compared to normal IECs (Fig. 6A, B), but induction was dampened in Phb1Tg/ApcMin/+ adenomas compared to ApcMin/+ adenomas (Fig. 6A, B). The number of Ki67+ cells in adenomas of Phb1Tg/ApcMin/+ mice was decreased compared to adenomas of ApcMin/+ mice (Fig. 6C, D and Supplementary Fig. S4). The number of Ki67+ cells in histologically normal regions were not altered by PHB1 overexpression (Fig. 6C, D). In agreement, normal IECs from Phb1Tg/ApcMin/+ mice exhibited PCNA expression similar to IECs from ApcMin/+ mice (Fig. 6A, B).

Figure 6. Phb1Tg/ApcMin/+ mice exhibit decreased proliferation in adenomas compared to ApcMin/+ mice.

(A) Representative western blots of PCNA in isolated IECs or adenomas. (B) Mean ± SEM of PCNA normalized to β-actin densitometric units. (C) Ki67 immunohistochemistry staining. Scale bars: 100 μm, boxed pullouts: 50 μm. (D) Ki67+ cells/crypt and percentage of the area of Ki67 immunostaining in adenomas per mouse ± SEM. n = 4 mice per group (A, B) or n =10 mice per group (C, D). *P < 0.05 vs ApcMin/+ IECs, #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 vs ApcMin/+ adenomas by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s test.

IEC-specific PHB1 overexpression was previously shown to be associated with increased apoptosis during a mouse model of colitis-associated cancer [23]. To determine whether PHB1 overexpression alters apoptosis in a model of spontaneous intestinal tumorigenesis, cleaved Caspase 3 and TUNEL staining were measured in ApcMin/+ and Phb1Tg/ApcMin/+ mice. Cleaved Caspase 3 expression was not altered by PHB1 overexpression in isolated IECs from jejunum or colon (Supplementary Fig. S5A, B). Cleaved Caspase 3 was decreased in jejunum and colonic adenomas in ApcMin/+ and Phb1Tg/ApcMin/+ mice compared to normal IECs, with Phb1Tg/ApcMin/+ adenomas exhibiting significantly higher expression than ApcMin/+ adenomas (Supplementary Fig. S5A, B). Consistent with these results, the number of TUNEL+ cells per adenoma was increased in Phb1Tg/ApcMin/+ mice compared to ApcMin/+ mice (Supplementary Fig. S5C, D). PHB1 overexpression decreased Wnt target gene expression, including Mmp7, Ccnd1, and Tcf4, in adenomas (Fig. 7A). This was consistent with decreased β-catenin protein expression and less nuclear localized β-catenin in Phb1Tg/ApcMin/+ adenomas compared to ApcMin/+ adenomas (Fig. 7B, C). Axin1 expression was increased in Phb1Tg/ApcMin/+ IECs and adenomas (Fig. 7A, B). These results suggest that PHB1 overexpression in IECs decreases proliferation and increases apoptosis in Wnt-dependent adenomas.

Figure 7. β-catenin activation in adenomas is inhibited in Phb1Tg/ApcMin/+ mice.

(A) Mean ± SEM of relative mRNA expression in isolated IECs or isolated adenomas. n = 6 mice per group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs ApcMin/+ IECs, #P < 0.05 vs ApcMin/+ adenomas by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s test. (B) Representative western blots of isolated IECs or adenomas. (C) β-catenin immunohistochemistry staining of colonic adenomas. Scale bars: 125 μm, boxed pullouts: 50 μm.

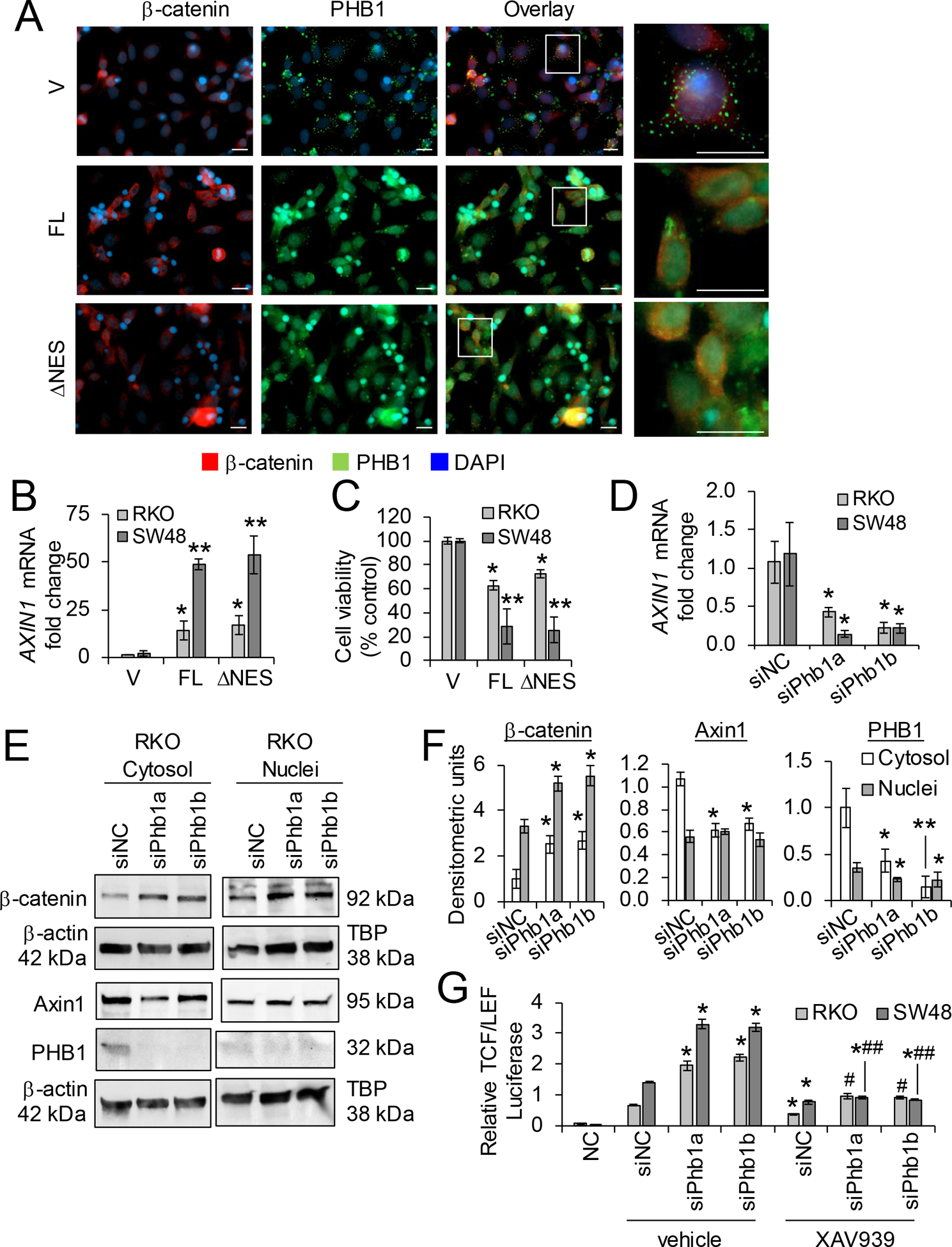

Relative expression of PHB1 regulates β-catenin activation in RKO and SW48 human CRC cell lines.

The role of PHB1 in cancer has been described as pro- and anti-tumorigenic depending on the tumor type [12]. This discrepancy has been proposed to be dependent on the subcellular localization of PHB1 [20, 24]. PHB1 possess a leucine/isoleucine nuclear export sequence (NES) at the C-terminus (aa 257–270) that is necessary for PHB1 export from the nucleus [10]. At the N-terminus of PHB1, a transmembrane domain (aa 2–24) anchors PHB1 to the inner mitochondrial membrane or cell membrane [24]. This structure facilitates dynamic shuttling of PHB1 between the nucleus and cytosol in a signal-dependent manner which has been shown to influence cell fate decisions [10]. PHB1 and β-catenin nuclear protein expression across human CRC cell lines SW48, HCT-116, SW480, Caco2, and RKO was compared to CCD-18Co non-transformed colon cells. β-catenin was most abundantly expressed in nuclei of SW480 cells, followed by HCT-116, SW48, and Caco2 cells (Supplementary Fig. S6A). CCD-18Co and RKO cells, which do not harbor genetic mutations that aberrantly activate the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, exhibited the lowest nuclear β-catenin expression. Although PHB1 was not abundantly expressed in the nuclei of these cell lines, its expression was highest in CCd-18Co, RKO, and Caco2 cells versus SW48, HCT-116, and SW480 (Supplementary Fig. S6A). To overexpress PHB1, RKO (wild-type for Wnt/β-catenin genes) and SW48 (mutant at S33 of β-catenin and exhibits aberrant activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling [25]) were transfected with pCDNA4 vector (V), the full-length coding sequence of PHB1 (pCDNA4-PHB1; PHB1-FL), or pCDNA4-PHB1ΔNES lacking the nuclear export signal. RKO and SW48 cells overexpressing PHB1-FL or PHB1ΔNES demonstrated increased nuclear PHB1 and decreased nuclear β-catenin expression (Fig. 8A and Supplementary Fig. S6B). PHB1-FL or PHB1ΔNES overexpression increased AXIN1 mRNA expression and decreased cell viability, with the greatest decrease in SW48 cells that harbor aberrant Wnt/β-catenin activation (Fig. 8B, C).

Figure 8. Relative expression of PHB1 regulates β-catenin activation and cell viability in RKO and SW48 CRC cell lines.

(A-C) RKO or SW48 cells were transfected with pCDNA4 (vector; V), full-length pCDNA4-PHB1 (FL), or pCDNA4-PHB1ΔNES (ΔNES) for 72 hr. (A) Immunofluorescent staining of RKO cells. Scale bars: 20 μm; boxed pullouts: 20 μm. (B) Mean ± SEM of relative AXIN1 mRNA expression. (C) Cell viability as measured by LDH release. (D-G) RKO or SW48 cells were transfected with 2 unique siRNAs against PHB1 or siNegative Control (siNC) for 48 hr. (D) Mean ± SEM of relative AXIN1 mRNA expression. (E) Representative western blot of β-catenin, AXIN1, or PHB1 (to demonstrate efficiency of siRNA knockdown). (F) Mean ± SEM of densitometric units by western blotting. (G) Relative luciferase expression of transcriptional activation by β-Catenin after 10 μM XAV939 or vehicle treatment for 16 hr. Negative control (NC) cells were transfected with a non-inducible firefly reporter construct. n = 3 (A, D-G) or n = 6 (B, C) biological replicates per group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs V by unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t test (B, C); *P < 0.05 vs siNC vehicle, #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 vs siPhb1 vehicle by one-way ANOVA (D, F) or two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s test (G).

To determine whether loss of PHB1 expression alters β-catenin activation in human CRC cell lines, RKO and SW48 cells were transfected with 2 unique siRNAs against PHB1 to knockdown PHB1 expression. PHB1 deficiency decreased AXIN1 mRNA and protein expression and increased β-catenin accumulation (Fig. 8D–F and Supplementary Fig. S6C, D). To determine whether the increase β-catenin activation during PHB1 knockdown is mediated by decreased AXIN1 levels, RKO and SW48 cells transfected with siPhb1 were treated with XAV939, a tankyrase inhibitor that results in AXIN1 protein accumulation [26]. As expected, XAV939 decreased TCF/LEF transcriptional activation in siNegative control cells (Fig. 8G). Additionally, XAV939 abolished siPhb1-induced TCF/LEF transcriptional activation with the most significant decrease in SW48 cells (Fig. 8G), suggesting that PHB1 deficiency results in loss of AXIN1 expression in CRC cells that can be restored by XAV939 to reduce β-catenin activation.

Discussion

The role of PHB1 in tumorigenesis is context-dependent and varies between tissue/tumor types. Although PHB1 expression is increased in CRC [21, 22], little was previously known regarding the expression or role of PHB1 in neoplasia prior to transformation. Using mice with IEC-specific overexpression or deletion of Phb1, we show that relative levels of PHB1 in IECs regulate adenoma formation in ApcMin/+ mice. IEC-specific overexpression of Phb1 inhibited Wnt/β-catenin activation, decreased proliferation, and increased apoptosis in ApcMin/+ adenomas, resulting in decreased adenoma numbers and size. Deletion of Phb1 in IECs increased Wnt/β-catenin activation and cell proliferation, resulting in increased ApcMin/+ adenoma numbers and size, with adenoma incidence and progression in the colon greatly enhanced. Importantly, we demonstrate that nuclear accumulation of PHB1 in CRC cell lines increased AXIN1 mRNA expression, decreased β-catenin nuclear expression, and decreased cell viability. Collectively, these results suggest that PHB1 plays an important role in regulating Wnt-dependent intestinal tumorigenesis. Complimentary results demonstrating that PHB1 acts as negative regulator of Wnt/β-catenin were reported in mouse liver and human hepatocarcinoma cells via inhibition of E2F1-induced Wnt10a or WNT9A promoter activation [27].

PHB1 serves diverse functions in the cell including regulation of cell cycle progression, apoptosis, and transcription depending on its subcellular localization [8]. Polymorphisms of the PHB1 gene have been linked to gastric, breast, ovarian, and skin cancers but whether these polymorphisms alter PHB1 function or subcellular localization has not been studied [28]. In normal IECs, PHB1 is predominantly localized in the mitochondria, where it has been shown to be required for optimal activity of the electron transport chain [14, 29–31]. Given the role of PHB1 in driving oxidative phosphorylation, mitochondrial localization of PHB1 in CRC cells likely sustains energy production necessary for transformed cells which rely on both oxidative phosphorylation and glycolysis [32]. The protein structural domains of PHB1 facilitates dynamic shuttling between the mitochondria, nucleus, and plasma membrane and in this way, PHB1 trafficking mediates signaling crosstalk between cellular organelles. Plasma membrane-localized PHB1 has been shown to promote metastasis [15] and migration of CRC cells in response to extrinsic chemotaxis [13].

The role of nuclear-localized PHB1 in CRC was not previously elucidated. Emerging evidence demonstrates bidirectional crosstalk between mitochondria and the Wnt pathway, specifically demonstrating Wnt signaling regulation of mitochondrial function including mitochondrial biogenesis, metabolism, and dynamics, as well as mitochondrial-directed regulation of Wnt signaling as a mechanism to influence cell fate decisions and tumorigenesis [7]. Our results demonstrating that forced nuclear accumulation of PHB1 by PHB1-FL or PHB1ΔNES overexpression in human RKO and SW48 CRC cells decreased Wnt/β-catenin activation and cell viability suggest that PHB1 serves as a mediator of mitochondria-to-nuclear signaling to regulate the Wnt pathway. Interestingly, nuclear accumulation of PHB1 induced the greatest decrease (72.7% ± 3.8) in cell viability in SW48 cells that harbor aberrant Wnt/β-catenin activation, suggesting that nuclear PHB1 expression may have therapeutic potential against Wnt-dependent CRC. Our recent study demonstrated that the synthetic small molecule FL3 induced nuclear partitioning of PHB1 in human CRC cells lines, suggesting a potential mechanism to therapeutically target this pathway [18]. Further evidence for PHB1/Wnt crosstalk is provided by a recent study demonstrating that PHB1 is a direct target gene of Wnt in leukemia cells via a TCF4 site in the PHB1 promoter [33]. Although Wnt regulation of PHB1 has not been studied in CRC, we speculate that the increased PHB1 expression in CRC specimens [21, 22] could, in part, be driven by Wnt.

AXIN1 or AXIN2 are the rate-limiting components of the β-catenin destruction complex with redundant functions in vivo in terms of inhibition of canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling [34]. AXIN1 is ubiquitously expressed and acts a tumor suppressor protein, whereas AXIN2 is a Wnt/β-catenin transcriptional target gene [35]. AXIN1 and AXIN2 undergo proteasomal degradation by tankyrase with even small increases in AXIN protein altering β-catenin abundance [36]. Interestingly, the promoter region of AXIN1 was recently shown to possess a putative PHB1 binding domain [18]. Phb1Tg/ApcMin/+ mice and PhbiΔIEC/ApcMin/+ mice exhibited increased and decreased Axin1 mRNA expression, respectively, suggesting that relative IEC-specific PHB1 expression regulates Axin1 transcription. Overexpression of nuclear PHB1 in RKO and SW48 CRC cell lines increased AXIN1 mRNA expression and decreased transcriptional activation by β-catenin. Furthermore, knockdown of PHB1 expression in RKO and SW48 cells decreased AXIN1 mRNA expression and increased TCF/LEF transcriptional activation that was abolished by restoring AXIN1 abundance with XAV939 treatment. These results suggest that nuclear PHB1 inhibits Wnt/β-catenin-signaling, in part through AXIN1 regulation, to suppress Wnt-driven intestinal tumorigenesis. Current tankyrase inhibitors that stabilize AXIN have shown effectiveness in ApcMin/+ mice and some APC-mutant CRC cell lines, suggesting that full-length APC function may not be strictly required for AXIN to degrade β-catenin [37]. The tight control AXIN1 expression exerts on the β-catenin destruction complex is a property currently being exploited in the development of novel therapeutics for Wnt-driven cancers [36] and our results suggest that nuclear PHB1 upregulation of Axin1 expression is sufficient to impact tumor growth in the absence of normal APC activity.

No adenomas were evident in Phb1Tg mice or in PhbiΔIEC mice, suggesting that PHB1 overexpression or deletion, respectively, in IECs was not sufficient to initiate intestinal tumorigenesis. In fact overexpression of PHB1 in normal IECs did not alter proliferation, apoptosis, or Wnt/β-catenin signaling, suggesting that PHB1 overexpression only alters Wnt/β-catenin activation after neoplastic progression. Future studies will determine whether PhbiΔIEC mice develop spontaneous intestinal neoplasia at time points beyond 12 weeks after the induction of Phb1 deletion. For instance, liver-specific Phb1 deficient mice develop hepatocellular carcinoma from 20 weeks of age [38]. Interestingly, in PhbiΔIEC/ApcMin/+ mice, adenoma incidence and growth was greatly increased in the colon, an anatomical location normally with infrequent adenomas compared to the small intestine in the ApcMin/+ model [17]. We speculate that enhanced colonic tumorigenesis during IEC-specific Phb1 deletion could be due to differing microbiota abundance and diversity between colon and small intestine, with colonic microbiota reported to influence CRC tumorigenesis [39]. Perhaps Phb1 deletion and ApcMin/+ in IECs, coupled with colonic microbiota, is a combination that drives colonic adenoma formation. Future studies using antibiotic-treated or germ-free PhbiΔIEC/ApcMin/+ mice will determine the role of microbiota in adenoma formation in this model.

In summary, these results define a role of PHB1 in inhibiting the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, thereby influencing the initiation and progression of intestinal tumorigenesis. Nuclear partitioning of PHB1 in human CRC cells was demonstrated to potently induce AXIN1 expression, inhibit β-catenin activation, and decrease cell viability, with the greatest efficacy in CRC cells harboring aberrant activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Induction of nuclear PHB1 trafficking provides a novel therapeutic option to influence AXIN1 expression and the β-catenin destruction complex in Wnt pathway-driven intestinal tumorigenesis.

Materials and Methods

Animal models

All mice were grouped-housed in standard cages under a controlled temperature (25˚C) and photoperiod (12-hour light /dark cycle) and were allowed standard chow and tap water ad libitum. All experiments were approved by the Baylor Scott & White Research Institute or University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Experiments were performed with age- and gender-matched littermate mice. Animals were allocated to experimental groups based on genotype, no further randomization was used.

Phb1fl/fl mice (C57Bl/6 genetic background), Phb1iΔIEC mice (C57Bl/6 background and previously described [16]), and Phb1Tg mice (C57Bl/6 background and previously described [19]) were crossed to ApcMin/+ mice (Jackson Labs). The resulting offspring were genotyped by PCR analysis of tail genomic DNA obtained at weaning for expression of the floxed Phb1 allele, Villin-Cre-ERT2 transgene, Phb1Tg transgene, or ApcMin/+ mutation using primer sequences previously described [16, 17, 19]. Wild-type (WT) C57Bl/6 mice were obtained from Jackson labs. Starting at 8 weeks of age, Phb1fl/fl mice and Phb1iΔIEC mice were i.p. injected with 100 μl of 10 mg/ml tamoxifen for 4 consecutive days to induce deletion of Phb1 as previously described [40]. To ensure continuity of Phb1 deletion, tamoxifen injections were repeated at 12, 16, and 19 weeks of age [40]. All mice were aged to 20 weeks and the entire small intestine and colon were excised, cut open longitudinally, and neoplasia number and size was quantitated by investigators blind to genotype using a dissecting microscope and prepared for histological evaluation or biochemical analyses. Adenomas were isolated using a dissecting microscope and combined by anatomical location (duodenum, jejunum, ileum, and colon). IECs were then isolated as previously described [41]. Since colon IECs produced low protein yield for nuclear and cytosolic fractionation, colonic mucosa was mechanically separated from the muscularis using a glass slide and processed for protein cell fractionation.

Cell culture

RKO (CRL-2577), SW48 (CCL-231), SW480 (CCL-228), Caco2 (HBT-37), HCT-116 (CCL-247), and CCD-18Co (CRL-1459) cells were acquired from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). Cells were cultured in 1X Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 40 mg/L penicillin and 90 mg/L streptomycin. Cells were maintained in an incubator with 5% CO2 at 37°C. All experiments were performed on RKO cells between passages 5 and 14 and SW48 between passages 4 and 10. All cell lines were verified mycoplasma free using Genlantis MycoScope PCR Detection kit as recently as March 2020 (Fisher Scientific). To overexpress nuclear PHB1, RKO and SW48 cells were transiently transfected for 72 hr using Nucleofector T kit (Lonza) with pCDNA4 expression vector (V), full-length coding region of PHB1 (pCDNA4-PHB1), or PHB1 with the nuclear export signal deleted (aa Δ256–271) and referred to as PHB1ΔNES herein [14]. To knockdown PHB1 expression, cells were transiently transfected with Stealth RNAi™ against Phb1 (5′-CAGAAUGUCAACAUCACACUGCGCA −3′, Invitrogen, referred to as siPhb1a herein), a second pooled siPhb1 (FlexiTube GeneSolution GS5245, Qiagen, referred to as siPhb1b herein), or Stealth RNAi™ siRNA Negative Control Med GC (Invitrogen) at 20 μm concentration for 48 hr and treated with tankyrase inhibitor/AXIN stabilizer 10 μM XAV939 (Sigma-Aldrich) for 16 hr.

SDS-PAGE and western immunoblot analysis

Protein lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE electrophoresis for western blotting. Nuclear and cytosolic proteins were extracted using the Qproteome Nuclear Protein Kit (Qiagen). The following antibodies were detected by chemiluminesence: PHB1 (PA5–17325, ThermoFisher) Axin1 (2087T, Cell Signaling), β-catenin (9581, Cell Signaling), Cleaved Caspase 3 (9661, Cell Signaling), PCNA (ab29, Abcam), TBP (ab818, Abcam), β-actin (A1978; Sigma-Aldrich). Densitometric units were measured using Photoshop CC and target proteins were normalized to TBP (nuclear extracts) or β-actin (cytosolic extracts) as loading controls. Whole membrane scans of western blots are shown in Supplementary Figures S7–S10.

RNA isolation and quantitative real-time PCR analysis

For quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis, total RNA was isolated using Trizol (Invitrogen) and was transcribed into cDNA using a High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosystems). Gene expression analysis was performed using Power SYBR Green Master Mix Assay (Applied Biosystems) on a Step One Plus real-time PCR detection system (Applied Biosystems). 18S was used as a control and results were calculated using the Δ-ΔCt method. The following primers were used: Mmp7 sense: 5’-GCTGCCACCCATGAATTTGG-3’; Mmp7 antisense: 5’-GCCTGCAATGTCGTCCTTTG-3’; Ccnd1 sense: 5’-GCTGCGAAGTGGAAACCATC-3’; Ccnd1 antisense: 5’-TTGAAGTAGGACACCGAGGG-3’; Tcf4 sense: 5’-CAGGGACCTTGGGTCACAT-3’; Tcf4 antisense: 5’-CAAGGAGACTCTGGTGGCAA-3’; Phb1 sense: 5′-GCATTGGCGAGGACTATGAT-3; Phb1 antisense 5′-CTCTGTGAGGTCATCGCTCA-3′; Axin1 sense: 5′-CCTGTGGTCTACCCGTGTCT-3’; Axin1 antisense: 5′-CTGGCTTTGGTGAACTGTTG-3’; 18S sense: 5’-CCCCTCGATGCTCTTAGCTGAGTGT-3’; 18S antisense: 5’-CGCCGGTCCAAGAATTTCACCTCT-3’.

Cell viability assay

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) detection kit (Takara Clontech) was used to measure cell cytotoxicity. An aliquot of 100 μl of culture media was added to 100 μl of LDH reagent and percentage of viable cells were measured according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

TCF/LEF luciferase reporter

Cell lines were Nucleofected with TCF/LEF Cignal Reporter construct containing TCF/LEF inducible firefly luciferase coupled with a constitutively active renilla luciferase construct (Qiagen; CCS018L). Negative control cells were Nucleofected with a non-inducible firefly luciferase reporter/constitutively active renilla luciferase construct (Qiagen; CCS018L). Dual luciferase activity was measured using the Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay (Promega; 0000262556).

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) staining

Immunofluorescent TUNEL staining was performed to measure apoptosis using the In Situ Cell Death Detection kit as described by the manufacturer (Roche). Nuclei were stained with 4, 6’diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). The number of TUNEL+ cells in were counted in all adenomas in swiss-rolled intestine and colon.

Immunohistochemistry

Five-micrometer paraffin-embedded sections of mouse intestine were incubated with β-Catenin (9581, Cell Signaling) or Ki67 (ACK02, Leica) antibody. Elimination of primary antibody or IgG control antibody was used as a negative control. ABC kit (Vector Labs) and DAB staining (Dako) were performed according to manufacturer’s protocol. Tissue sections were briefly counter-stained with hematoxylin (Sigma) to visualize tissue morphology and imaged using Zeiss Axioskop Plus microscope. The number of Ki67+ cells per crypt was counted in 50 well-oriented crypts. All adenomas in each section were digitally captured at 20× magnification. Using Image J software (NIH), DAB staining was quantified as previously described (9) and expressed as the percentage of the whole region of interest. Percentage values from the same mouse were then averaged.

Immunofluorescence

Cells were plated on coverslips, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min, and permeabilized in 0.2% Triton-X100 in 1x PBS for 10 min on ice. After washing in 1x PBS, cells were incubated with blocking buffer (2% BSA in 1x PBS) for 1 hr followed by incubation with primary antibodies (β-Catenin (9581, Cell Signaling) at 1:50 dilution in blocking buffer and PHB1 (PA5–17325, ThermoFisher) at 1:100 dilution) for 16 hr at 4°C. After washing in 1x PBS, cells were incubated with secondary antibodies (Rhodamine Red™-X (RRX) AffiniPure F(ab’)₂ Fragment Donkey Anti-Rabbit IgG, 711-296-152, Jackson Immuno and FITC AffiniPure F(ab’)₂ Fragment Donkey Anti-Mouse IgG) at 1:500 dilution for 1 hr. Cells were then stained with 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI, D9542, Sigma) at 1:1000 in 1x PBS for 5 min. Cells were visualized using Zeiss Axioskop Plus microscope.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Setting a 2-fold increase or decrease in adenoma number as a biologically relevant response to Phb1 deletion or overexpression, respectively, with an alpha and beta level set at 0.05 and 0.2, a sample size of n = 10 mice per group was used to power the study (Stata version 9, StataCorp). An unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test was used for single comparisons, one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test for multiple comparisons, and two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test for assessing the combination of genotype and anatomical location or XAV939 treatment (GraphPad Prism 8.2). The data met the assumptions of the utilized statistical tests. Sum of squares between groups indicated variance between groups being compared during ANOVA. Spearman rank was used to analyze the correlation of PHB1 densitometric units with β-catenin densitometric units (Prism). P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Jie Han (Baylor Scott & White Research Institute) for technical assistance. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01-DK117001 (ALT), Litwin IBD Pioneers Crohn’s Colitis Foundation 301869 (ALT), and GI & Liver Innate Immune Program (GALIIP) - University of Colorado Anschutz (ALT).

Abbreviations:

- APC

adenomatous polyposis coli

- CRC

colorectal cancer

- IECs

intestinal epithelial cells

- PHB1

Prohibitin 1

- WT

wild-type

Footnotes

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests in relation to the work described.

References

- 1.Arnold M, Sierra MS, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global patterns and trends in colorectal cancer incidence and mortality. Gut 2017; 66: 683–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 2015; 65: 87–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barker N, Ridgway RA, van Es JH, van de Wetering M, Begthel H, van den Born M et al. Crypt stem cells as the cells-of-origin of intestinal cancer. Nature 2009; 457: 608–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fearon ER, Vogelstein B. A genetic model for colorectal tumorigenesis. Cell 1990; 61: 759–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schatoff EM, Leach BI, Dow LE. Wnt Signaling and Colorectal Cancer. Curr Colorectal Cancer Rep 2017; 13: 101–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Behrens J, Jerchow BA, Wurtele M, Grimm J, Asbrand C, Wirtz R et al. Functional interaction of an axin homolog, conductin, with beta-catenin, APC, and GSK3beta. Science 1998; 280: 596–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delgado-Deida Y, Alula KM, Theiss AL. The influence of mitochondrial-directed regulation of Wnt signaling on tumorigenesis. Gastroenterol Rep 2020; 8: 215–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Basmadjian C, Thuaud F, Ribeiro N, Desaubry L. Flavaglines: potent anticancer drugs that target prohibitins and the helicase eIF4A. Future Med Chem 2013; 5: 2185–2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thuaud F, Ribeiro N, Nebigil CG, Desaubry L. Prohibitin ligands in cell death and survival: mode of action and therapeutic potential. Chem Biol 2013; 20: 316–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rastogi S, Joshi B, Fusaro G, Chellappan S. Camptothecin induces nuclear export of prohibitin preferentially in transformed cells through a CRM-1-dependent mechanism. J Biol Chem 2006; 281: 2951–2959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou TB, Qin YH. Signaling pathways of prohibitin and its role in diseases. J Recept Signal Transduct Res 2013; 33: 28–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang D, Tabti R, Elderwish S, Abou-Hamdan H, Djehal A, Yu P et al. Prohibitin ligands: a growing armamentarium to tackle cancers, osteoporosis, inflammatory, cardiac and neurological diseases. Cell Mol Life Sci 2020; Epub ahead of print 15 Feb 2020; doi: 10.1007/s00018-020-03475-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma LL, Shen L, Tong GH, Tang N, Luo Y, Guo LL et al. Prohibitin, relocated to the front ends, can control the migration directionality of colorectal cancer cells. Oncotarget 2017; 8: 76340–76356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Theiss AL, Idell RD, Srinivasan S, Klapproth JM, Jones DP, Merlin D et al. Prohibitin protects against oxidative stress in intestinal epithelial cells. FASEB J 2007; 21: 197–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chiu CF, Ho MY, Peng JM, Hung SW, Lee WH, Liang CM et al. Raf activation by Ras and promotion of cellular metastasis require phosphorylation of prohibitin in the raft domain of the plasma membrane. Oncogene 2013; 32: 777–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jackson DN, Panopoulos M, Neumann WL, Turner K, Cantarel BL, Thompson-Snipes L et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction during loss of prohibitin 1 triggers Paneth cell defects and ileitis. Gut 2020; Epub ahead of print 28 February 2020; doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-319523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cormier RT, Bilger A, Lillich AJ, Halberg RB, Hong KH, Gould KA et al. The Mom1AKR intestinal tumor resistance region consists of Pla2g2a and a locus distal to D4Mit64. Oncogene 2000; 19: 3182–3192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jackson DN, Alula KM, Delgado-Deida Y, Tabti R, Turner K, Wang X et al. The synthetic small molecule FL3 combats intestinal tumorigenesis via Axin1-mediated inhibition of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. Cancer Res 2020; Epub ahead of print 14 July 2020; doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-1120-0216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Theiss AL, Vijay-Kumar M, Obertone TS, Jones DP, Hansen JM, Gewirtz AT et al. Prohibitin is a novel regulator of antioxidant response that attenuates colonic inflammation in mice. Gastroenterology 2009; 137: 199–208, 208 e191–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Theiss AL, Sitaraman SV. The role and therapeutic potential of prohibitin in disease. Biochim Biophys Acta 2011; 1813: 1137–1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen D, Chen F, Lu X, Yang X, Xu Z, Pan J et al. Identification of prohibitin as a potential biomarker for colorectal carcinoma based on proteomics technology. Int J Oncol 2010; 37: 355–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hammoudi A, Song F, Reed KR, Jenkins RE, Meniel VS, Watson AJ et al. Proteomic profiling of a mouse model of acute intestinal Apc deletion leads to identification of potential novel biomarkers of human colorectal cancer (CRC). Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2013; 440: 364–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kathiria AS, Neumann WL, Rhees J, Hotchkiss E, Cheng Y, Genta RM et al. Prohibitin attenuates colitis-associated tumorigenesis in mice by modulating p53 and STAT3 apoptotic responses. Cancer Res 2012; 72: 5778–5789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peng YT, Chen P, Ouyang RY, Song L. Multifaceted role of prohibitin in cell survival and apoptosis. Apoptosis 2015; 20: 1135–1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tortelote GG, Reis RR, de Almeida Mendes F, Abreu JG. Complexity of the Wnt/betacatenin pathway: Searching for an activation model. Cell Signal 2017; 40: 30–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krishnamurthy N, Kurzrock R. Targeting the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway in cancer: Update on effectors and inhibitors. Cancer Treat Rev 2018; 62: 50–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mavila N, Tang Y, Berlind J, Ramani K, Wang J, Mato JM et al. Prohibitin 1 Acts As a Negative Regulator of Wingless/Integrated-Beta-Catenin Signaling in Murine Liver and Human Liver Cancer Cells. Hepatol Commun 2018; 2: 1583–1600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chowdhury D, Kumar D, Sarma P, Tangutur AD, Bhadra MP. PHB in Cardiovascular and Other Diseases: Present Knowledge and Implications. Curr Drug Targets 2017; 18: 1836–1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bourges I, Ramus C, Mousson de Camaret B, Beugnot R, Remacle C, Cardol P et al. Structural organization of mitochondrial human complex I: role of the ND4 and ND5 mitochondria-encoded subunits and interaction with prohibitin. Biochem J 2004; 383: 491–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hsieh SY, Shih TC, Yeh CY, Lin CJ, Chou YY, Lee YS. Comparative proteomic studies on the pathogenesis of human ulcerative colitis. Proteomics 2006; 6: 5322–5331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsutsumi T, Matsuda M, Aizaki H, Moriya K, Miyoshi H, Fujie H et al. Proteomics analysis of mitochondrial proteins reveals overexpression of a mitochondrial protein chaperon, prohibitin, in cells expressing hepatitis C virus core protein. Hepatology 2009; 50: 378–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yu L, Lu M, Jia D, Ma J, Ben-Jacob E, Levine H et al. Modeling the Genetic Regulation of Cancer Metabolism: Interplay between Glycolysis and Oxidative Phosphorylation. Cancer Res 2017; 77: 1564–1574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim DM, Jang H, Shin MG, Kim JH, Shin SM, Min SH et al. beta-catenin induces expression of prohibitin gene in acute leukemic cells. Oncol Rep 2017; 37: 3201–3208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chia IV, Costantini F. Mouse axin and axin2/conductin proteins are functionally equivalent in vivo. Mol Cell Biol 2005; 25: 4371–4376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leung JY, Kolligs FT, Wu R, Zhai Y, Kuick R, Hanash S et al. Activation of AXIN2 expression by beta-catenin-T cell factor. A feedback repressor pathway regulating Wnt signaling. J Biol Chem 2002; 277: 21657–21665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang Z, Tacchelly-Benites O, Yang E, Thorne CA, Nojima H, Lee E et al. Wnt/Wingless Pathway Activation Is Promoted by a Critical Threshold of Axin Maintained by the Tumor Suppressor APC and the ADP-Ribose Polymerase Tankyrase. Genetics 2016; 203: 269–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lau T, Chan E, Callow M, Waaler J, Boggs J, Blake RA et al. A novel tankyrase small-molecule inhibitor suppresses APC mutation-driven colorectal tumor growth. Cancer research 2013; 73: 3132–3144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ko KS, Tomasi ML, Iglesias-Ara A, French BA, French SW, Ramani K et al. Liver-specific deletion of prohibitin 1 results in spontaneous liver injury, fibrosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma in mice. Hepatology 2010; 52: 2096–2108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jackson DN, Theiss AL. Gut bacteria signaling to mitochondria in intestinal inflammation and cancer. Gut Microbes 2020; 11: 285–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.el Marjou F, Janssen KP, Chang BH, Li M, Hindie V, Chan L et al. Tissue-specific and inducible Cre-mediated recombination in the gut epithelium. Genesis 2004; 39: 186–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nenci A, Becker C, Wullaert A, Gareus R, van Loo G, Danese S et al. Epithelial NEMO links innate immunity to chronic intestinal inflammation. Nature 2007; 446: 557–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.