Abstract

In the past 20 years, patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), Crohn's disease (CD), and other immune diseases have witnessed the impact of a great treatment advance with the availability of biological TNFα inhibitors. With 5 approved anti-TNFα biologics on the market and soon available biosimilars, patients have more treatment options and have benefited from understanding the biology of TNFα. Nevertheless, many unmet needs remain for people living with TNFα-related diseases, namely some side effects and tolerance of current anti-TNFα biologics and resistance to therapies. Furthermore, common diseases such as osteoarthritis and back/neck pain may respond to anti-TNFα therapies at early onset of symptoms. Development of new TNFα inhibitors focusing on TNFR1 specific inhibitors, preferably small molecules that can be delivered orally, is much needed.

Keywords: Antibodies, Receptors, Small molecule inhibitors, TNFα, TNFR1

TNFα and TNF receptors

TNFα

Tumor Necrosis Factor α (TNFα) is a small 157-amino-acid cytokine that has a number of functions. Initially TNF was described to have anti-tumor activity, as suggested by its name, and was determined to be in the sera of mice infected with bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) and exposed to endotoxin.1 Serum with TNF activity in fact demonstrated ability to kill tumor cells in vitro and in vivo. In fact, physician William B. Coley2 was one of the first to recognize a regression of tumors once a cancer patient contracted a bacterial infection.

In 1984, human TNFα cDNA was first cloned after TNFα was purified from HL-60 leukemia cells.3 The TNFα protein has about 30% homology with human lymphotoxin (also known as TNFβ). After that, TNFα was found to be a major regulator of immune function and inflammatory response.4 In vivo experiments showed that purified mouse TNFα could inhibit the growth or even completely shrink implanted tumors, mostly by inducing a host immune response.5

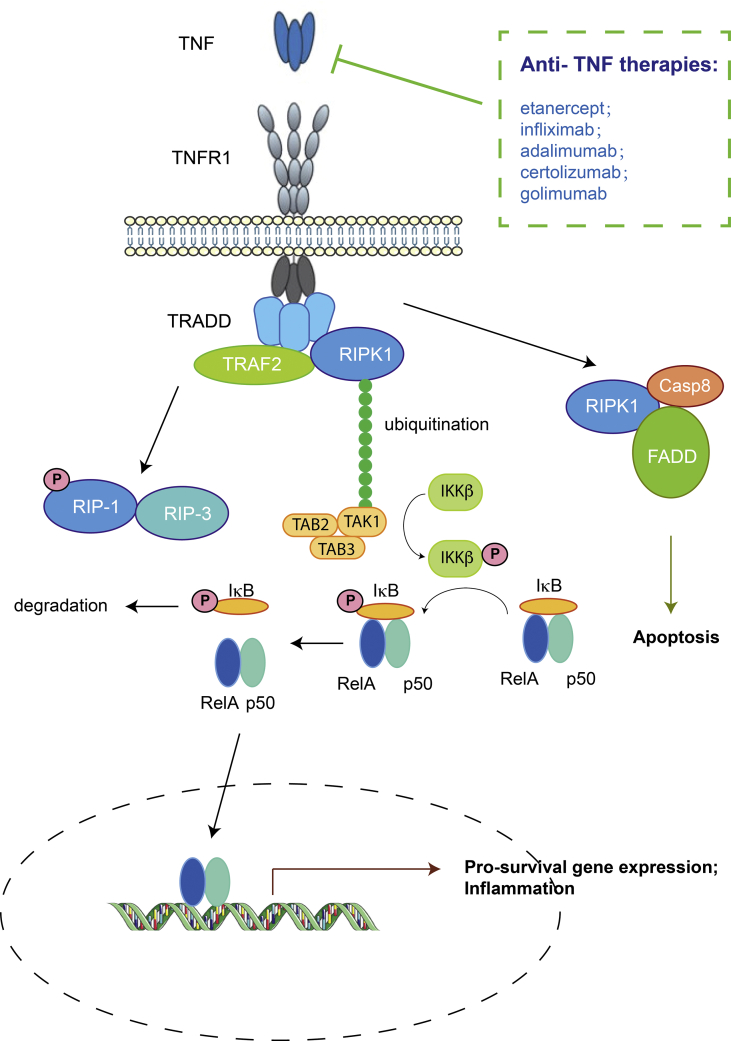

Initially, activated macrophages were identified as the major source of TNFα. Later on, many other cell types were also reported to secrete TNFα, including T cells, NK cells, neutrophils, mast cells, and non-immune cells.6 TNFα plays critical functions in the regulation of the immune system and is fundamental in host protection against microbial infection. An excess of TNFα signaling activity can lead to a number of autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel diseases (Fig. 1). Inappropriate TNFα activity is also correlated with diseases such as sepsis7 and cerebral malaria,8 although it is unclear whether TNFα blockade could lead to effective therapies for these two diseases.

Figure 1.

TNFα signaling pathways and approved therapies.

There are two forms of TNFα: the soluble ligand form (sTNFα) and the membrane-bound form (tmTNFα). TNFα is expressed as tmTNFα with a transmembrane domain. Trimeric tmTNFα proteins are attached to the cell surface via their transmembrane domains. TNFα releasing enzymes, such as tumor necrosis factor-α converting enzyme (TACE/ADAM17/CD156q), can cleave tmTNFα and release soluble TNFα into the circulation. TNFα can thus travel to, and affect, target cells that are distant from TNFα-producing cells including macrophages.

TNF receptors

Structurally TNFα exists as a homotrimer. Accordingly, TNFα receptors (TNFRs) also exist in the form of homotrimers, and are of two types: TNFR1 (p55) and TNFR2 (p75). Mouse TNFα cross-reacts with both human TNFR1 and TNFR2. On the other hand, human TNFα primarily binds mouse TNFR1, and only minimally activates mouse TNFR2.9,10

The human sTNFα binds to both TNFR1 and TNFR2 with sub-nanomolar affinity, although its affinity for TNFR1 is slightly higher due to slower dissociation (KD for TNFR1: 0.019 nM, KD for TNFR2: 0.42 nM, at 37 °C).11 While sTNFα activates both TNFR1 and TNFR2, tmTNFα mainly signals through TNFR2 in various systems, such as T cell activation, thymocyte proliferation, and granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor (gm-CSF) production.12

TNFR1 is expressed in most cell types, but is more abundant on white blood cells, including cells of myeloid lineage (e.g., monocytes). TNFR2 expression is limited to hematopoietic cells, as well as some oligodendrocytes and endothelial cells.13 In a chronic model of proliferative nephritis, expression of TNFR2 in renal endothelial cells was essential for sustained macrophage accumulation.

Regulatory T cells, also known as Treg cells, have low TNFR1 but high TNFR2 expression. Treg cells in general function as a negative regulator for the immune system, maintaining tolerance to self-antigens and preventing autoimmune disease. Using TNFR1(−/−) and TNFR2(−/−) mice, Yang et al studied the effect of TNFα on induced Treg (iTreg),14 and found that TNFR1, although critical for the differentiation of inflammatory T cells such as Th1 and Th17 cells, was not required for the maintenance of iTreg functions. However, TNFR2 was found to be crucial for iTreg differentiation, proliferation, and function. As TNFα may enhance the differentiation and function of iTreg via TNFR2 signaling, TNFR2-agonists or TNFR1-specific antagonists may be effective therapeutics for treating patients with immune diseases.14

Current anti-TNF therapeutics

Since TNFα is a key factor in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases (IMID), anti-TNFα agents have been developed successfully for IMID such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and Crohn's disease. Currently there are 5 approved anti-TNF biologics available to patients (Fig. 1, Table 1).

Table 1.

Five approved anti-TNF biologics.

| Generic name | Brand name | TNF binding domain | Fc or PEGylation | Indications | Year of FDA approval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Etanercept | Enbrel | human TNFR2 | human Fc | rheumatoid arthritis | 1998 |

| polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis | 1999 | ||||

| psoriatic arthritis | 2002 | ||||

| ankylosing spondylitis | 2003 | ||||

| plaque psoriasis | 2004 | ||||

| pediatric plaque psoriasis | 2016 | ||||

| Infliximab | Remicade | murine variable region of anti-TNF | human Fc | Crohn's disease | 1998 |

| rheumatoid arthritis (with MTX) | 1999 | ||||

| ankylosing spondylitis | 2004 | ||||

| psoriatic arthritis | 2005 | ||||

| ulcerative colitis | 2005 | ||||

| pediatric Crohn's disease | 2006 | ||||

| plaque psoriasis | 2006 | ||||

| pediatric ulcerative colitis | 2011 | ||||

| Adalimumab | Humira | human Fab of anti-TNF | human Fc | rheumatoid arthritis | 2002 |

| psoriatic arthritis | 2005 | ||||

| ankylosing spondylitis | 2006 | ||||

| Crohn's disease | 2007 | ||||

| plaque psoriasis | 2008 | ||||

| polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis | 2008 | ||||

| ulcerative colitis | 2012 | ||||

| pediatric Crohn's disease | 2014 | ||||

| hidradenitis suppurativa | 2015 | ||||

| Non-Infectious Intermediate, Posterior and Panuveitis | 2016 | ||||

| fingernail psoriasis | 2017 | ||||

| Certolizumab | Cimzia | humanized Fab of anti-TNF | PEG | Crohn's disease | 2008 |

| rheumatoid arthritis | 2009 | ||||

| psoriatic arthritis | 2013 | ||||

| ankylosing spondylitis | 2013 | ||||

| plaque psoriasis | 2018 | ||||

| axial spondyloarthritis, non-radiographic | 2019 | ||||

| Golimumab | Simponi | human Fab of anti-TNF | human Fc | rheumatoid arthritis | 2009 |

| psoriatic arthritis | 2009 | ||||

| ankylosing spondylitis | 2009 | ||||

| ulcerative colitis | 2013 | ||||

| rheumatoid arthritis (infusion) | 2013 | ||||

| psoriatic arthritis (infusion) | 2017 | ||||

| ankylosing spondylitis (infusion) | 2017 |

On August 24, 1998, Remicade® (infliximab) received accelerated approval from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of Crohn's disease. This was the first TNFα inhibitor approved for clinical use.

Also in 1998, Enbrel (etanercept) was approved by the FDA for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Before the approval of etanercept, only NSAIDs (Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs) and methotrexate were available as the treatment for RA. NSAIDs are useful only for the relief of mild pain from RA, while methotrexate, an anti-cancer drug, is toxic and its therapeutic effect for RA is limited.

As a key driver in inflammation, TNFα has been validated as a good drug target in many immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. So far, there are five biological anti-TNFα agents approved for the treatment of RA, polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and plaque psoriasis (Table 1). Four of the drugs are TNFα antibodies aimed to sequester TNFα by preventing it from binding to TNF-receptors. The only exception is, etanercept (Enbrel), which is a circulating TNFα receptor fusion protein to sequester TNFα. The key differences among these 5 drugs are introduced to reduce host elimination of the drugs by humanizing the antibodies.

Etanercept (Enbrel®)

Etanercept is an Fc fusion protein of the extracellular ligand-binding domain of human TNFR2. The Fc fragment, which is commonly used to extend the serum half-life of the engineered protein, is from human immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) Etanercept binds to TNFα and blocks its interaction with TNFα receptors, thereby intercepting the inflammation and immune responses induced by TNFα. Etanercept can be administered by subcutaneous injection. It has a mean elimination half-life of around 70 h. Anti-drug antibodies are rarely detected in patients receiving etanercept treatment.15

Etanercept can be given alone or in combination with methotrexate to treat active RA patients. A standard measurement of response is the “20% improvement in disease activity according to the American College of Rheumatology” (ACR 20). At 6 months, the ACR 20 responses were 51% and 59% for patients receiving etanercept at 10 mg twice weekly and 25 mg twice weekly, respectively. In comparison, methotrexate alone resulted in only 11% ACR 20.16 When combined with methotrexate, etanercept treatment achieves an ACR 20 of more than 80%17 at 6 months.

Etanercept is found to lower the number of memory B cells in the peripheral blood, follicular dendritic cell networks, and germinal center structures in tonsil biopsies of patients with RA. However, etanercept does not suppress lipopolysaccharide-induced TNFα and interleukin-1β production in a human monocytic cell line, nor does it induce cell-cycle arrest that leads to reduced T-cell proliferation. In contrast, infliximab does both of these things. Compared with an anti-TNFα antibody such as infliximab, etanercept has lower affinity for tmTNFα.18 This suggests that etanercept mainly intercepts sTNFα and TNFR1 interaction and retains tmTNFα and TNFR2 signaling. Out of all five TNFα blockers, data from the DANBIO registry (a nationwide registry of biological therapies in Denmark) revealed that etanercept was the best tolerated drug overall with the longest drug half-life.

Infliximab

Infliximab, the first anti-TNFα to reach routine clinical use, is a chimeric anti-TNFα monoclonal antibody that was first named cA2. Infliximab consists of a murine variable region and human constant region.

Infliximab was first tested for sepsis but failed to achieve any reduction of mortality as compared to placebo. However, in a 12-year old patient with Crohn's disease who was non-responsive to conventional therapies, infliximab as a compassionate-use treatment led to response after the first dose.19

Infliximab was later tested in a 12-week multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in patients with treatment-resistant luminal Crohn's disease, and demonstrated 65% response rate after a single dose. The response was significantly superior to the 17% response in the control group.20 In fistulizing Crohn's disease, infliximab treatment at the doses of 5 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg led to the closure of draining fistulas in 68% and 56% of patients, respectively, as compared to 26% in the control group.21 With these two trials to show the safety and efficacy, infliximab received accelerated approval from the FDA for Crohn's disease in 1998, and later from the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and agencies from 100 other countries.19

Healing of the mucosa in Crohn's disease patients occurs after infliximab induction treatment, and 50% of initial responders receiving infliximab maintenance therapy had complete mucosal healing at one year.22 In RA, the combination of infliximab and methotrexate treatment led to inhibition of joint damage.23 This is remarkable, since no prior treatments for RA could achieve this.

Following Crohn's disease, infliximab has been approved for RA, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, ulcerative colitis, and plaque psoriasis. For RA, infliximab plus methotrexate resulted in an ACR 20 response rate of 50–58%, vs. 20% for MTX alone.24 One drawback for infliximab is that intravenous infusion is required, less convenient than agents that are delivered by subcutaneous injections.

Since infliximab contains mouse amino acid sequence in the variable region, immunogenicity is always a concern. Induction of anti-drug antibodies (ADAs) is associated with rapid degradation of infliximab. Patients failing infliximab with elevated serum ADA levels tend to have a good clinical outcome after switching to etanercept.25 During clinical trials, ADAs were reported in 28.3% of patients after treatment with infliximab, and patients with low serum infliximab levels were associated with increased levels of ADAs. A high loading or priming dose of infliximab is thus proposed as a strategy to minimize ADAs. In addition, co-administration with methotrexate can both reduce immunogenicity and minimize the development of ADAs against infliximab.19

Adalimumab

Adalimumab is a recombinant human monoclonal antibody to TNFα. Despite being a human IgG, adalimumab can still induce ADAs. In a recent study of more than 20,000 patients who received adalimumab, ADAs were detected in 40% of these patients, and serum adalimumab concentrations were inversely related to ADA titers. Compared with the mean serum adalimumab concentration (6.1 μg/mL) from ADA-free patients, low concentrations of ADA (<100 ng/mL) appeared to have minimal impact on mean drug levels, while high ADAb titers (>300 ng/mL) were invariably associated with much reduced drug levels, to less than 30% of mean levels in patients without ADAs.26

Studies have shown that when paired with MTX, adalimumab provided a better clinical response and reduced radiographic progression in RA patients. In patients treated with 80 mg adalimumab plus MTX, 65.8% reached ACR 20.27 Most of the responses were rapid and could be observed within one week. In addition, the 40-mg and 80-mg doses of adalimumab in combination with MTX resulted in a statistically significant ACR70 response (26.9% and 19.2%, respectively) when compared with MTX alone.

Golimumab

Golimumab is a fully humanized IgG1 antibody produced by a murine hybridoma cell line. The splenocytes used to establish the hybridoma cell line were derived from humanized Medarex UltiMAb® (Medarex, Princeton, NJ, USA) transgenic mice. As the first once-monthly subcutaneous anti-TNFα therapy, golimumab is approved in the US and Europe for the treatment of moderately to severely active rheumatoid arthritis, active psoriatic arthritis and active ankylosing spondylitis, and is available for subcutaneous delivery.

Intravenous administration of a single dose of 100 mg golimumab appears to produce higher serum concentration (Cmax) than does subcutaneous administration (29.5 μg/mL vs. 6.3 μg/mL), but the median terminal half-life was similar for both (IV: 11.8 days; SC: 10.9 days).28 After the SC administration of 100 mg golimumab, it takes 3.5 days to reach Cmax. Concomitant use of methotrexate increased the mean steady-state trough serum concentration as well as the half-life.29 It is speculated that methotrexate, an immunosuppressive agent, may limit the production of ADAs that accelerate the degradation of golimumab. In people with detectable ADAs, the half-life of golimumab can be as short as 2.9 days.29 In the phase III GO-FORWARD trial, patients receiving 100 mg golimumab monthly plus methotrexate had an ACR 20 response rate of 56.2% at week 14.30

Certolizumab

Certolizumab is a recombinant Fab fragment of a humanized TNFα antibody conjugated to 40-kDa polyethylene glycol (PEG). While other TNFα blockers are produced in mammalian cells, certolizumab is produced in bacteria and can have reduced production costs. Conjugation to PEG, or PEGylation, is a common practice to extend the half-life of small proteins. This is achieved by reducing renal clearance, decreasing proteolysis, and by theoretically decreasing immunogenicity. The PEGylation increases certolizumab's half-life to the point where it is comparable to that of intact monoclonal antibodies (~13 days).31

Other biological TNFα inhibitors are either full length antibodies or Fc fusion proteins. They all contain the human Fc fragment that could potentially induce immune effector functions. Certolizumab lacks the Fc portion, and thus will not induce complement-dependent lysis and antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity.

Certolizumab may be administered with or without methotrexate. When used as monotherapy in RA, patients who received 400 mg certolizumab every 4 weeks had an ACR 20 response rate of 45.5% vs. 9.3% in the placebo group.32 When certolizumab was combined with MTX, 58.8%–60.8% ACR 20 was achieved at week 24, compared with 13.6% in the placebo group.33

Long-term safety and efficacy were studied for certolizumab plus MTX in patients with RA. After treatment for 6 months with certolizumab 400 mg every 2 weeks, the dose was reduced to 200 mg every 2 weeks for maintenance treatment up to 5 years. For patients previously treated with certolizumab who had demonstrated a response, clinical improvements were maintained to week 232 if they could continue to use certolizumab. For patients who failed to reach ACR 20 goal in prior treatments, mean ACR 20/50/70 responses were 68.4%, 47.1%, and 25.1%, respectively.34 In summary, certolizumab provided sustained improvements in clinical outcomes for 5 years, and was well tolerated.

Issues with current TNFα blockers

Which TNFα blocker is better?

With all the five TNFα blockers on the market, and more biosimilars expected to be approved, patients and their physicians may be wondering which TNFα blocker is best. Since there has been no direct comparison of all these five TNFα blockers in one clinical trial, it is difficult to draw a definitive conclusion. However, looking at the real world data may provide some insights.

DANBIO is a nationwide registry of biological therapies in Denmark for patients with rheumatologic diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis, axial spondyloarthritis, and psoriatic arthritis. The database also monitors the quality of clinical treatment at national, regional, and hospital levels. All patients suffering from any rheumatologic disease or who are taking medication mainly used to combat rheumatologic diseases are required to enter their data into this registry, regardless whether they are seeking treatment from a public hospital or a private clinic.

With the DANBIO database, a study compared three of the five available TNFα blockers for treating RA (adalimumab, etanercept, and infliximab).35 Patients initiated with different TNFα blockers were compared for their response and remission measured by American College of Rheumatology criteria (70% improvement, ACR70) at 6 months and Disease Activity Score in 28 joints (DAS28) at 48 months, respectively.

Adalimumab was shown to have the highest rates in treatment response and disease remission.

Infliximab had the lowest rates of treatment response, disease remission, and drug adherence. Etanercept showed the longest drug adherence rate and also a good response that is comparable to adalimumab.

Although the DANBIO database provides a way to compare different TNFα blockers for their clinical activity, a side-by-side comparison in a random and double blind clinical trial is required to draw a conclusion. Nevertheless, from the real world data, it is clear that for certain people one TNFα blocker might be better than others. For example, for RA patients with a high risk of tuberculosis, etanercept is preferred over infliximab and adalimumab.36 According to the data from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register (BSRBR), the rate of tuberculosis in patients treated with infliximab or adalimumab was 3–4 fourfold higher than in those treated with etanercept.36

Immune diseases induced by TNF blockers

TNFα blockade could lead to a feedback of further immune activation and production of additional immune cytokines, contributing to the disease's pathogenesis or to interruption of TNFα-mediated tissue repair via TNFR2. For example, TNF-α, IL-17 and IFN-α are all involved in pathogenesis of psoriatic lesions. IFN-α is produced mainly by plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDC), which are inhibited by TNFα. Therefore, in the presence of TNFα blockade, there will be an increase of pDC cells and activity. IFN-α also stimulates and activates T cells to produce TNFα and IL-17, leading to an overactive immune response and psoriasis lesions.

Treatment time frame

RA, Crohn's disease and psoriasis are chronic diseases. One question that patients always ask will be whether the treatment can be stopped after the disease is in remission.

In a clinical trial conducted by Tanaka et al,37 RA patients treated with infliximab were taken off this medication and their subsequent clinical course were recorded. After attaining low disease activity by infliximab treatment, 56 (55%) of the 102 patients with RA were able to discontinue infliximab for >1 year without progression of radiological articular destruction. The results also showed that lower patient age and shorter disease duration were associated with a greater likelihood of success in drug withdrawal. Some studies have also found that if anti-TNFα medication is initiated early on in RA disease development, it is possible to induce faster disease remission and increase the chance of a successful medication withdrawal.

TNF inhibitors under development

ATROSAB

Atrosab is a new generation humanized monoclonal antibody that specifically blocks the pro-inflammatory TNF receptor 1 (TNFR1), without interacting with the TNF receptor 2 (TNFR2). Since TNFR2 is implicated in pro-survival (anti-apoptosis) and regeneration-promoting signals, a TNFR1-specific TNFα inhibitor is considered to be more advantageous than inhibitors that block both TNFR1 and TNFR2. Atrosab is the first humanized version of H398, an antagonistic TNFR1-specific antibody.38 Unfortunately, the bivalent full length antibody is able to cross-link TNFR1 in the absence of ligand, showing intrinsic agonist activity in a certain concentration range.

To circumvent the cross-linking issue, a monovalent Fab fragment from Atrosab, Fab13.7, has been selected for further development. Its binding to TNFR1 has been strengthened by affinity maturation and site-directed mutagenesis. Thus, Fab13.7 has superior inhibition of TNFα-mediated TNFR1 activation while lacking agonistic activity. Fab13.7 would be a true antagonist in the presence or absence of TNFα.39 However, the half-life of Fab13.7 is significantly shorter than that of an intact IgG antibody. To extend the half-life and also to reserve monovalent binding, Fab13.7 was engineered to be expressed as a fusion protein of a heterodimerizing Fc domain (Fc-one/kappa, or Fc1k).40 This newly generated fusion protein had an extended serum half-life, and strong binding to TNFR1, without affecting TNFR2.

Another approach to increase the half-life is PEGylation. The pegylated form, Fab13.7PEG, has an EC50 value of 0.37 nM, which is 2.2 times better than Atrosab. Fab13.7PEG also expressed bioactivity scoring 1.5 to 1.9 times greater than Atrosab. However, Fab13.7PEG has an initial half-life of 0.08 h and terminal half-life of 1.4 h, compared with 2.2 h and 41.7 h for Atrosab, respectively.39

Small molecule TNFα inhibitors

Small molecules that could be delivered orally to patients are the future of new TNFα inhibitors, Patients with diseases less destructive to tissue organs, such as osteoarthritis and low back pain, would demand drugs with fewer and less severe side effects, and oral delivery. Structures of some of the small molecule TNFα inhibitors under investigation is shown (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Structures of small molecule TNFα inhibitors.

Suramin

Suramin is a polysulfonated urea analog used mainly to combat trypanosomiasis (caused by parasitic protozoan trypanosomes) and onchocerciasis (blindness caused by Onchocerca volvulus infection). Suramin was found to interfere with TNFα trimerization, an essential step to form the active ligand for binding to TNFα receptors.41 In addition, Suramin analogs including Evans blue and trypan blue were identified to have the structural characteristics responsible for interaction with TNFα. These two dyes were shown to inhibit TNFα-TNFR1 binding with an IC50 of 0.75 and 1.00 mM, respectively, as compared with the IC50 of 0.65 mM for suramin.42

Interestingly, Suramin was also found to inhibit the binding of CD40 ligand (CD40L) to CD40 with high affinity.43 In the collagen induced arthritis rat model for RA, suramin showed in vivo activity to reduce inflammation and repair joint destruction at a dose of 10 mg/kg/day for 3 weeks by intraperitoneal injection.44 Suramin also showed activity in an acute liver injury model induced by d-galactosamine (GalN) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS).45

SPD304

SPD304 is a small TNFα inhibitor that destabilizes the TNFα trimer.46 When bound to TNFα, SPD304 greatly increases the dissociation rate of TNFα trimers, leading to disassembly of the active form of the TNFα ligand. SPD304 has an IC50 value of 22 μM to inhibit TNFα-TNFR1 interaction, and prevents 50% of TNFα-induced NF-κB activation at 4.6 μM.46 SPD304 also binds to RANKL, another member of the TNF family, with an affinity of 14 μM.47,48 In an ischemia-induced heart failure rat model, SPD304 was able to show some activity.49 Analogs of SPD304 have been investigated to reduce toxicity, but none has produced optimal anti-TNFα activity for further clinical studies.50

IW927

Carter et al identified IW927, a small antagonist molecule binding to TNFR1, by screening chemical libraries. IW927 was found to block TNFα binding to its receptor with an IC50 of 50 nM. IW927 also disrupted TNFα-induced IκB phosphorylation with an IC50 of 600 nM.51 No binding of IW927 to TNFR2 or CD40 was detected, and this compound appeared to be safe as judged by cell-based assay.

IV703, a “photochemically enhanced” analog of IW927, was able to bind reversibly to the TNFR1 with weak affinity but can be covalently attached to the receptor via a photochemical reaction. A crystal structure of IV703 and TNFR1 was obtained to show that the inhibitor interacts with a surface region of TNFR1 that is involved in TNFα binding.51

Physcion-8-O-β-d-monoglucoside (PMG)

By surface plasmon resonance (SPR) screening of extracts from five herbs, Cao et al revealed that Rheum officinale contains a compound that binds to TNFR1. Recovered compounds were pooled and analyzed by an ultra-performance liquid chromatography/quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (UPLC-QTOF-MS/MS). A major component matched the profile of physcion-8-O-β-d-monoglucoside (PMG). Purified PMG was used to confirm binding to TNFR1 by SPR, and demonstrated an affinity of 376 nM.52

The inhibitory effect of PMG on TNFα activity was tested with L929 cells for TNFα-induced cell death. Cell apoptosis was also examined with annexin V-FITC/PI double staining. At 20 μM, PMG showed anti-TNFα activity comparable to SPD304.

“Compound 1”

Using a combined in silico/in vitro/in vivo screening approach, Mouhsine et al identified a new TNFα direct inhibitor, “Compound 1”, that binds to TNFα with high affinity at nM levels, and inhibits TNFα activity by effectively disrupting TNFα–TNFR binding.53 This inhibitor prevents TNFα-induced apoptosis and NF-κB activation in L929 and HEK cell lines, respectively. It also showed in vivo activity in a hepatic shock model, although a high dose was needed due to low solubility and poor bioavailability.

TNF cavity-induced allosteric modification (CIAM) inhibitors

A CIAM method was developed to identify surface cavities near protein–protein interaction sites. With the CIAM method, a pseudo-allosteric cavity was identified distal to the WP9 loop, a critical TNFα contact site in TNFR1.54 Compounds that could bind to the cavity and induce conformational perturbation at WP9 were identified after standard virtual screening procedures were employed. F002 was designed and synthesized based on the structure of a first generation compound. Binding of F002 to TNFR1 was verified by isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC). Since there is only one tryptophan residue (W107) in the TNFR1 ectodomain located in the WP9 loop, binding to F002 will induce changes that can be detected by fluorescence quenching. In L929 cells, F002 was able to rescue cells from TNFα induced cytotoxicity in a dose dependent manner. Moreover, F002 binding inhibited TNFα mediated IκBα and p38 phosphorylation in both murine L929 and human monocyte THP-1 cells.55

In vivo activity of F002 was studied in the collagen-induced arthritis model. Mice treated with F002 showed a dose dependent decrease in the clinical features of arthritis compared with the untreated or control group. Histological analysis of ankles of the animals revealed that F002 treated mice have significantly reduced synovitis and mononuclear cell infiltration. Cartilage destruction was also prevented in the F002 treated group. These studies suggest that targeted conformational perturbation of receptor conformation disables TNFR1 functions.

Recently, two compounds that were improved from F002 were tested in a traumatic brain injury (TBI) mouse model.56 In this model, injury-induced sleep lasts for 6 h and coincides with increased cortical levels of inflammatory cytokines, including TNFα. Brain-injured mice treated with Compound 7 or SGT11 slept significantly less than those treated with vehicle. SGT11 restored cognitive, sensorimotor, and neurological function. C7 and SGT11 significantly decreased cortical inflammatory cytokines 3 h post-TBI. The study suggests that TNFα inhibitors can be used to target neuroinflammation after traumatic brain injury.

Conclusion

In the past two decades, emerging biological TNFα inhibitors have changed the paradigm of treating TNFα-related immune diseases. Not only more effective treatments are available, the cost of treatment is likely to be driven down by the patent expiration for the first generation of biologic anti-TNF agents and the availability of biosimilars. Biosimilars of infliximab, etanercept, and adalimumab have shown similar efficacy as the original drugs and have reached patients in Europe and other countries. In the US, although the FDA has approved two etanercept biosimilars, neither is available to patients yet. Although the TNFα inhibitor market is facing challenges from other therapies targeting inflammation molecules, such as IL-6 inhibitors (sarilumab) and JAK inhibitors, it is expected that TNFR1 specific inhibitors, including small molecules that could be delivered orally to patients are the future of new TNFα inhibitors.

Funding

This work is supported, in part, by research grants to YZ from the Department of Veterans Affairs Healthcare Network, a Penn Center for Musculoskeletal Disorders (PCMD) pilot grant (P30-AR050950-10 Pilot), and a grant from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS, R21 AR071623).

Conflict of Interests

All author declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

All authors have read and approved the final submitted manuscript. The authors thank Martin F. Heyworth, MD, for critically editing the manuscript, and Dr. Mark I. Greene and his lab members for discussions.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chongqing Medical University.

Contributor Information

Hongtao Zhang, Email: zhanghon@pennmedicine.upenn.edu.

Yejia Zhang, Email: yejia.zhang@uphs.upenn.edu, yejia.zhang@va.gov.

References

- 1.Carswell E.A., Old L.J., Kassel R.L., Green S., Fiore N., Williamson B. An endotoxin-induced serum factor that causes necrosis of tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1975;72(9):3666–3670. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.9.3666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coley W.B. II. Contribution to the knowledge of sarcoma. Ann Surg. 1891;14(3):199–220. doi: 10.1097/00000658-189112000-00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pennica D., Nedwin G.E., Hayflick J.S. Human tumour necrosis factor: precursor structure, expression and homology to lymphotoxin. Nature. 1984;312(5996):724–729. doi: 10.1038/312724a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen G., Goeddel D.V. TNF-R1 signaling: a beautiful pathway. Science. 2002;296(5573):1634–1635. doi: 10.1126/science.1071924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haranaka K., Satomi N., Sakurai A. Antitumor activity of murine tumor necrosis factor (TNF) against transplanted murine tumors and heterotransplanted human tumors in nude mice. Int J Cancer. 1984;34(2):263–267. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910340219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zelova H., Hosek J. TNF-alpha signalling and inflammation: interactions between old acquaintances. Inflamm Res. 2013;62(7):641–651. doi: 10.1007/s00011-013-0633-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lv S., Han M., Yi R., Kwon S., Dai C., Wang R. Anti-TNF-α therapy for patients with sepsis: a systematic meta-analysis. Int J Clin Pract. 2014;68(4):520–528. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gimenez F., Barraud de Lagerie S., Fernandez C., Pino P., Mazier D. Tumor necrosis factor α in the pathogenesis of cerebral malaria. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2003;60(8):1623–1635. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-2347-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bossen C., Ingold K., Tardivel A. Interactions of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and TNF receptor family members in the mouse and human. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(20):13964–13971. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601553200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ando D., Inoue M., Kamada H. Creation of mouse TNFR2-selective agonistic TNF mutants using a phage display technique. Biochem Biophys Rep. 2016;7:309–315. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrep.2016.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grell M., Wajant H., Zimmermann G., Scheurich P. The type 1 receptor (CD120a) is the high-affinity receptor for soluble tumor necrosis factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(2):570–575. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.2.570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grell M., Douni E., Wajant H. The transmembrane form of tumor necrosis factor is the prime activating ligand of the 80 kDa tumor necrosis factor receptor. Cell. 1995;83(5):793–802. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90192-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Venkatesh D., Ernandez T., Rosetti F. Endothelial TNF receptor 2 induces IRF1 transcription factor-dependent interferon-beta autocrine signaling to promote monocyte recruitment. Immunity. 2013;38(5):1025–1037. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang S., Xie C., Chen Y. Differential roles of TNFalpha-TNFR1 and TNFalpha-TNFR2 in the differentiation and function of CD4(+)Foxp3(+) induced Treg cells in vitro and in vivo periphery in autoimmune diseases. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10(1):e27. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-1266-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moots R.J., Xavier R.M., Mok C.C. The impact of anti-drug antibodies on drug concentrations and clinical outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with adalimumab, etanercept, or infliximab: results from a multinational, real-world clinical practice, non-interventional study. PLoS One. 2017;12(4):e0175207. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moreland L.W., Schiff M.H., Baumgartner S.W. Etanercept therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130(6):478–486. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-6-199903160-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bae S.C., Kim J., Choe J.Y. A phase III, multicentre, randomised, double-blind, active-controlled, parallel-group trial comparing safety and efficacy of HD203, with innovator etanercept, in combination with methotrexate, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: the HERA study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(1):65–71. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-207613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scallon B., Cai A., Solowski N. Binding and functional comparisons of two types of tumor necrosis factor Antagonists. J Pharmacol Exp Therapeut. 2002;301(2):418–426. doi: 10.1124/jpet.301.2.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Melsheimer R., Geldhof A., Apaolaza I., Schaible T. Remicade((R)) (infliximab): 20 years of contributions to science and medicine. Biologics. 2019;13:139–178. doi: 10.2147/BTT.S207246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Targan S.R., Hanauer S.B., van Deventer S.J. A short-term study of chimeric monoclonal antibody cA2 to tumor necrosis factor alpha for Crohn's disease. Crohn's Disease cA2 Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(15):1029–1035. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199710093371502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Present D.H., Rutgeerts P., Targan S. Infliximab for the treatment of fistulas in patients with Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(18):1398–1405. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199905063401804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rutgeerts P., Diamond R.H., Bala M. Scheduled maintenance treatment with infliximab is superior to episodic treatment for the healing of mucosal ulceration associated with Crohn's disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63(3):433–442. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lipsky P.E., van der Heijde D.M., St Clair E.W. Infliximab and methotrexate in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor Trial in Rheumatoid Arthritis with Concomitant Therapy Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(22):1594–1602. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011303432202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maini R., St Clair E.W., Breedveld F. Infliximab (chimeric anti-tumour necrosis factor alpha monoclonal antibody) versus placebo in rheumatoid arthritis patients receiving concomitant methotrexate: a randomised phase III trial. ATTRACT Study Group. Lancet. 1999;354(9194):1932–1939. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)05246-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jamnitski A., Bartelds G.M., Nurmohamed M.T. The presence or absence of antibodies to infliximab or adalimumab determines the outcome of switching to etanercept. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(2):284–288. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.135111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kelly C., Imir M., Jeanne E. The relationship between serum adalimumab and corresponding anti-adalimumab antibody levels: analysis of over 20,000 patient results. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114:S17–S18. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weinblatt M.E., Keystone E.C., Furst D.E. Adalimumab, a fully human anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha monoclonal antibody, for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in patients taking concomitant methotrexate: the ARMADA trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(1):35–45. doi: 10.1002/art.10697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu Z., Wang Q., Zhuang Y. Subcutaneous bioavailability of golimumab at 3 different injection sites in healthy subjects. J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;50(3):276–284. doi: 10.1177/0091270009340782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhuang Y., Xu Z., Frederick B. Golimumab pharmacokinetics after repeated subcutaneous and intravenous administrations in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and the effect of concomitant methotrexate: an open-label, randomized study. Clin Therapeut. 2012;34(1):77–90. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2011.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keystone E.C., Genovese M.C., Klareskog L. Golimumab, a human antibody to tumour necrosis factor {alpha} given by monthly subcutaneous injections, in active rheumatoid arthritis despite methotrexate therapy: the GO-FORWARD Study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(6):789–796. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.099010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baker M., Stephens S. Investigation of the pharmacokinetic properties of certolizumab pegol, an anti-TNF agent: 1117. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:S437. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fleischmann R., Vencovsky J., van Vollenhoven R.F. Efficacy and safety of certolizumab pegol monotherapy every 4 weeks in patients with rheumatoid arthritis failing previous disease-modifying antirheumatic therapy: the FAST4WARD study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(6):805–811. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.099291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Keystone E., Heijde D., Mason D., Jr. Certolizumab pegol plus methotrexate is significantly more effective than placebo plus methotrexate in active rheumatoid arthritis: findings of a fifty-two-week, phase III, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(11):3319–3329. doi: 10.1002/art.23964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smolen J.S., van Vollenhoven R., Kavanaugh A. Certolizumab pegol plus methotrexate 5-year results from the rheumatoid arthritis prevention of structural damage (RAPID) 2 randomized controlled trial and long-term extension in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;17(1):e245. doi: 10.1186/s13075-015-0767-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hetland M.L., Christensen I.J., Tarp U. Direct comparison of treatment responses, remission rates, and drug adherence in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with adalimumab, etanercept, or infliximab: results from eight years of surveillance of clinical practice in the nationwide Danish DANBIO registry. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(1):22–32. doi: 10.1002/art.27227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dixon W.G., Hyrich K.L., Watson K.D. Drug-specific risk of tuberculosis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with anti-TNF therapy: results from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register (BSRBR) Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(3):522–528. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.118935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tanaka Y., Takeuchi T., Mimori T. Discontinuation of infliximab after attaining low disease activity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: RRR (remission induction by Remicade in RA) study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(7):1286–1291. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.121491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zettlitz K.A., Lorenz V., Landauer K. ATROSAB, a humanized antagonistic anti-tumor necrosis factor receptor one-specific antibody. mAbs. 2010;2(6):639–647. doi: 10.4161/mabs.2.6.13583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Richter F., Zettlitz K.A., Seifert O. Monovalent TNF receptor 1-selective antibody with improved affinity and neutralizing activity. mAbs. 2019;11(1):166–177. doi: 10.1080/19420862.2018.1524664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Richter F., Seifert O., Herrmann A., Pfizenmaier K., Kontermann R.E. Improved monovalent TNF receptor 1-selective inhibitor with novel heterodimerizing Fc. Taylor & Francis; 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alzani R., Corti A., Grazioli L., Cozzi E., Ghezzi P., Marcucci F. Suramin induces deoligomerization of human tumor necrosis factor alpha. J Biol Chem. 1993;268(17):12526–12529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mancini F., Toro C.M., Mabilia M., Giannangeli M., Pinza M., Milanese C. Inhibition of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha)/TNF-alpha receptor binding by structural analogues of suramin. Biochem Pharmacol. 1999;58(5):851–859. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00150-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Margolles-Clark E., Jacques-Silva M.C., Ganesan L. Suramin inhibits the CD40-CD154 costimulatory interaction: a possible mechanism for immunosuppressive effects. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009;77(7):1236–1245. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sahu D., Saroha A., Roy S., Das S., Srivastava P.S., Das H.R. Suramin ameliorates collagen induced arthritis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2012;12(1):288–293. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2011.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goto T., Takeuchi S., Miura K. Suramin prevents fulminant hepatic failure resulting in reduction of lethality through the suppression of NF-kappaB activity. Cytokine. 2006;33(1):28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2005.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.He M.M., Smith A.S., Oslob J.D. Small-molecule inhibition of TNF-alpha. Science. 2005;310(5750):1022–1025. doi: 10.1126/science.1116304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Papaneophytou C.P., Rinotas V., Douni E., Kontopidis G. A statistical approach for optimization of RANKL overexpression in Escherichia coli: purification and characterization of the protein. Protein Expr Purif. 2013;90(1):9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Melagraki G., Ntougkos E., Rinotas V. Cheminformatics-aided discovery of small-molecule protein-protein interaction (PPI) dual inhibitors of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and receptor activator of NF-kappaB ligand (RANKL) PLoS Comput Biol. 2017;13(4):e1005372. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yu Y., Cao Y., Bell B. Brain TACE (tumor necrosis factor-alpha-converting enzyme) contributes to sympathetic excitation in heart failure rats. Hypertension. 2019;74(1):63–72. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.119.12651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Melagraki G., Leonis G., Ntougkos E. Current status and future prospects of small-molecule protein-protein interaction (PPI) inhibitors of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and receptor activator of NF-kappaB ligand (RANKL) Curr Top Med Chem. 2018;18(8):661–673. doi: 10.2174/1568026618666180607084430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carter P.H., Scherle P.A., Muckelbauer J.K. Photochemically enhanced binding of small molecules to the tumor necrosis factor receptor-1 inhibits the binding of TNF-alpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(21):11879–11884. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211178398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cao Y., Li Y.H., Lv D.Y. Identification of a ligand for tumor necrosis factor receptor from Chinese herbs by combination of surface plasmon resonance biosensor and UPLC-MS. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2016;408(19):5359–5367. doi: 10.1007/s00216-016-9633-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mouhsine H., Guillemain H., Moreau G. Identification of an in vivo orally active dual-binding protein-protein interaction inhibitor targeting TNFalpha through combined in silico/in vitro/in vivo screening. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):e3424. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-03427-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Takasaki W., Kajino Y., Kajino K., Murali R., Greene M.I. Structure-based design and characterization of exocyclic peptidomimetics that inhibit TNF alpha binding to its receptor. Nat Biotechnol. 1997;15(12):1266–1270. doi: 10.1038/nbt1197-1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Murali R., Cheng X., Berezov A. Disabling TNF receptor signaling by induced conformational perturbation of tryptophan-107. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(31):10970–10975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504301102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rowe R.K., Harrison J.L., Zhang H. Novel TNF receptor-1 inhibitors identified as potential therapeutic candidates for traumatic brain injury. J Neuroinflammation. 2018;15(1):e154. doi: 10.1186/s12974-018-1200-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]