Abstract

The term energy metabolism comprises the entirety of chemical processes associated with uptake, conversion, storage, and breakdown of nutrients. All these must be tightly regulated in time and space to ensure metabolic homeostasis in an environment characterized by cycles such as the succession of day and night. Most organisms evolved endogenous circadian clocks to achieve this goal. In mammals, a ubiquitous network of cellular clocks is coordinated by a pacemaker residing in the hypothalamic suprachiasmatic nucleus. Adipocytes harbor their own circadian clocks, and large aspects of adipose physiology are regulated in a circadian manner through transcriptional regulation of clock-controlled genes. White adipose tissue (WAT) stores energy in the form of triglycerides at times of high energy levels that then serve as fuel in times of need. It also functions as an endocrine organ, releasing factors in a circadian manner to regulate food intake and energy turnover in other tissues. Brown adipose tissue (BAT) produces heat through nonshivering thermogenesis, a process also controlled by the circadian clock. We here review how WAT and BAT contribute to the circadian regulation of energy metabolism. We describe how adipose rhythms are regulated by the interplay of systemic signals and local clocks and summarize how adipose-originating circadian factors feed-back on metabolic homeostasis. The role of adipose tissue in the circadian control of metabolism becomes increasingly clear as circadian disruption leads to alterations in adipose tissue regulation, promoting obesity and its sequelae. Stabilizing adipose tissue rhythms, in turn, may help to combat disrupted energy homeostasis and obesity.

Keywords: circadian clocks, energy metabolism, adipose tissue, BAT, WAT, circadian rhythm, hormones, adipokines, cytokines, thermogenesis, obesity

Molecular and Cellular Circadian Networks

Many aspects of the environment show regular rhythms. For many organisms the most prominent of these rhythms is the 24-hour solar cycle resulting in changes in, for example, illumination, temperature, or food availability. Species throughout all phyla have adapted to these predictable variations by evolving internal timekeepers, so-called circadian clocks (from the Latin “circa diem,” meaning “around a day”).

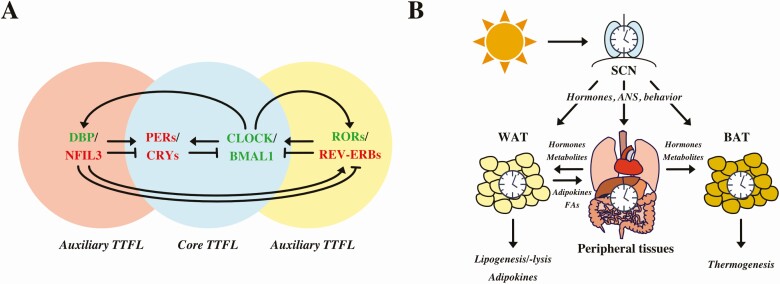

At the molecular level, the circadian clock of mammals consists of clock genes such as brain and muscle aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator-like protein 1 (Bmal1, aka Arntl), circadian locomotor output cycles kaput (Clock) and its analogue, neuronal PAS domain protein 2 (Npas2), cryptochrome 1 and 2 (Cry1/2), and period 1-3 (Per1-3) (Fig. 1A) (1). They interact in a transcriptional-translational feedback loop (TTFL), which comprises the heart of the clock machinery (2). Briefly, in the morning BMAL1 and CLOCK heterodimerize and bind to E-box enhancers in the promotors of Per and Cry genes (3). Over the course of the day PER and CRY proteins translocate into the nucleus, where they inhibit CLOCK:BMAL1–mediated transcription, including their own (4). Gradual degradation of PER and CRY during the night is controlled by the casein kinases and F-box ubiquitin transferases, thus resulting in disinhibition of CLOCK:BMAL1 toward the next morning (1). This core loop is stabilized by a second TTFL in which retinoic acid-related orphan receptors (RORα-γ) and reverse erythroblastoma (REV-ERBα/β, aka NR1D1/2) proteins compete for binding to retinoic acid-related orphan receptor response elements (ROREs) in the promotor of Bmal1 (5). Thereby, RORs activate whereas REV-ERBs inhibit Bmal1 gene expression. A third feedback loop consists of D-site albumin promotor binding protein and nuclear factor interleukin 3 regulated (NFIL3, aka E4BP4), which modulate gene expression by binding to D-boxes in the promotors of several clock genes, for example, Per1-3, Rev-Erbα/β, Rorα/β, and Cry1 (5-10). The role of D-boxes as additional feedback loops is still a current research topic. So far it is assumed that D-box regulation is involved in circadian signaling. However, mice deficient for E4bp4 do not show differences in circadian oscillation (6). These interlocked TTFLs drive circadian gene expression of thousands of tissue-specific clock-controlled genes throughout the day (11, 12).

Figure 1.

A, The core transcriptional-translational feedback loop (TTFL) comprises the transcription factors brain and muscle aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator-like protein 1 (BMAL1) and circadian locomotor output cycles kaput (CLOCK), inducing expression of period 1-3 (PERs) and cryptochrome 1 and 2 (CRYs), which in turn repress BMAL1:CLOCK activity. The circadian clock is modulated and stabilized by auxiliary loops. Nuclear factor interleukin 3 regulated (NFIL3) and D-site albumin promotor binding protein (DBP) inhibit and activate expression of several clock genes, respectively. Retinoic acid-related orphan receptors (RORs) and reverse erythroblastoma (REV-ERBs) are controlled by BMAL1:CLOCK and function as activators or inhibitors of Bmal1 expression, respectively. B, The zeitgeber light aligns the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) with the external light-dark cycle. Peripheral clocks, for example, white adipose tissue (WAT), gut, liver, pancreas, and brown adipose tissue (BAT), are synchronized by the SCN via the autonomic nervous system (ANS), hormones, and behavior. The circadian clock network drives rhythms in lipogenesis and lipolysis as well rhythmic release of adipokines from WAT. BAT produces heat via nonshivering thermogenesis.

Molecular clocks are found in all cells and tissues. This circadian clock network is organized in a hierarchical manner with a master pacemaker located in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus (13). The most prominent, the zeitgeber—an external time signal entraining the endogenous circadian clock—is light. Light reaches melanopsin (OPN4) expressing intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells that directly project to the SCN through the retinohypothalamic tract (14, 15). In this way, the SCN aligns its internal rhythm with the external light-dark cycle. In the absence of regular light input, the endogenous circadian rhythm is maintained, showing a “free-running” species-specific period close to 24 hours (2). From the SCN, behavioral, neuronal, and humoral signals transmit internal time to peripheral tissues (Fig. 1B) (16). Apart from light, other zeitgebers can influence the circadian clock network. The timing of food intake, for example, is a potent zeitgeber of peripheral tissue clocks while only marginally affecting the master pacemaker (17, 18).

Adipose Functions in Metabolism

Most adipose tissue depots in mammals are classified as “white” (19) with spherical cells of variable size (25-200 µm) and a single large lipid droplet. Brown adipocytes, on the other hand, are smaller (15-60 µm) and contain multiple small lipid droplets as well as much more mitochondria (20). One main function of white adipose tissue (WAT) is the storage of energy. Stimulated by insulin, glucose and lipoprotein-derived fatty acids (FAs) are taken up by the adipocyte where they are converted into triglycerides (TGs) (21, 22). If energy levels drop, stored TGs are broken down during lipolysis and released as glycerol and FAs that can then both be used as energy sources by other organs (23, 24). WAT is also an important endocrine organ. White adipocytes release adipocytokines such as leptin and adiponectin to regulate metabolic functions in other peripheral tissues and the brain (24).

Brown adipose tissue (BAT) differs morphologically and functionally from WAT. Brown adipocytes convert energy into heat by nonshivering thermogenesis (20). Cold exposure as well as noradrenergic stimulation lead to β-adrenergic excitation, which then induces lipolysis in brown adipocytes (22, 25). The resulting FAs activate uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1), which forms a proton leak in the inner mitochondrial membrane to produce heat during oxidative phosphorylation (25, 26).

Oscillating Signals Regulate White Adipose Tissue Metabolism

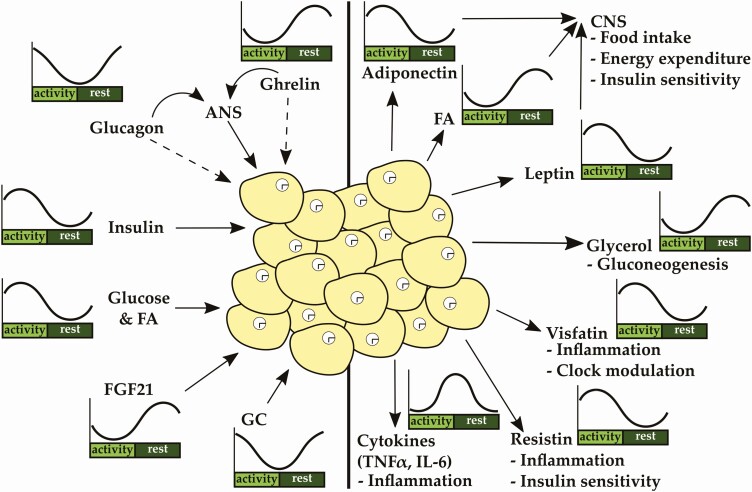

Metabolic homeostasis is regulated by the interaction of different organs, including liver, pancreas, adrenal, and adipose tissue, in a circadian manner. Involved tissues release factors or stimulate the autonomic nervous system to mediate the metabolic state to other participating organs. WAT is a target tissue that receives and integrates numerous signals. WAT metabolism is strongly controlled by the interplay of 2 pancreatic hormones, β-cell–derived insulin and α-cell–derived glucagon, both of which are regulated by energy intake while also showing underlying circadian rhythms in plasma levels controlled by the SCN (27). Besides regulation by the SCN, cell-autonomous clocks in α and β cells control the circadian release of locally produced hormones (28-31). α- and β-Cell clocks show distinct phases in vivo and in vitro, with the α-cell clock being phase delayed by 1 to 2 hours compared to β cells. Cell type–specific clocks regulate the transcription of key genes involved in glucose sensing and hormone release (28). Together, the findings show that insulin—but also glucagon—release is regulated by the intrinsic clock in the distinct cell types and is affected by metabolic state. Food intake increases circulating FAs, amino acids, and glucose, which triggers the release of insulin from pancreatic β cells, resulting in a peak of blood insulin levels in the middle of the active phase (27, 28). In adipocytes, insulin inhibits lipolysis and activates lipogenesis (Fig. 2) (32-34). Insulin-mediated repression of lipolysis is regulated via the mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1)-early growth response element 1 pathway, which inhibits adipose triglyceride lipase (Atgl) promotor activity, encoding a key enzyme of lipolysis (32), and other key proteins of the lipolytic pathway including hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL) and perilipin (35-39). On the other hand, insulin increases glucose and FA uptake as well as FA synthesis and TG storage by glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4, aka SLC2A4) translocation and activating upstream stimulatory factor-1/2/regulatory element-binding protein-1c (SREBP-1c)- and carbohydrate-response element binding protein-α/β (ChREBP-α/β)-mediated target gene expression, respectively (40). Insulin sensitivity is gated by the clock (41-43). In vitro studies suggest that insulin action, that is, activation of the protein kinase B–pathway, depends on adipose clock function at least in subcutaneous adipose tissue (41). Glucagon, released from pancreatic α cells as a signal of low energy, is a strong counterregulatory signal of insulin and displays high levels in the transition of rest to activity phase. Although it is still not clear whether adipocytes actually express the glucagon receptor, the hormone induces adipose lipolysis. Glucagon’s effects may be mediated by stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system (SNS), which induces lipolysis via β-adrenergic pathways (44-47).

Figure 2.

White adipose tissue (WAT) function is regulated by numerous rhythmic signals originating from other peripheral or central tissues. The circadian clocks in white adipocytes are essential for proper WAT function. WAT releases adipokines and cytokines in a circadian manner, regulating food intake, insulin sensitivity, and inflammation. ANS indicates autonomic nervous system; IL, interleukin; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

Fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) is regulated by NFIL3 (aka E4BP4) and peaks during the fasting period (48). It is predominantly synthesized in the liver and regulates carbohydrate and lipid metabolism (48-50). In lean mice, FGF21 increases adipose lipid uptake through cluster of differentiation 36 (CD36) and lipoprotein lipase (LPL). Conversely, in insulin-resistant obese mice, FGF21 increases catabolism of TGs in BAT while inducing WAT browning by an increase in PGC-1α protein levels (51-53). FGF21 potently lowers blood glucose levels by increasing glucose uptake into the liver, WAT, and BAT (54, 55) via adiponectin (56, 57). Moreover, adiponectin seems to mediate FGF21-induced energy expenditure (57). Ghrelin, a stomach-derived hormone, shows a diurnal oscillation with increased levels during fasting and low levels during feeding phases (58-60), and its messenger RNA (mRNA) expression and release are disrupted in Bmal1 knockouts (60). Ghrelin promotes lipogenic gene expression in WAT via autonomic stimulation (61, 62) or directly through activation of its receptor, growth hormone secretagogue receptor, which is expressed in adipocytes of old, but hardly detectable in young, mice (63).

Glucocorticoids (GCs) are secreted from the adrenal in a circadian manner and in response to stress. The adrenal clock gates the sensitivity to incoming signals and regulates GC rhythms (64). The local clock is important for rhythmic production of steroidogenic genes but seems to be dispensable for rhythmic GC output (65, 66). Global clock disruption deletes rhythmic GC output (64, 67). GCs promote adipocyte differentiation (68-70). Dampened GC rhythms result in increased lipid accumulation and body weight gain due to upregulation of the FA transporter Cd36 (71). Hypercortisolemia increases lipolysis while at the same time promoting visceral adiposity, probably by enhanced preadipocyte differentiation (69, 72). GCs stimulate the expression of Hsl, Atgl, and Lpl, key enzymes of the lipolytic pathway, in a dose-dependent manner (73-76). At the same time, GCs promote adipose insulin resistance by downregulating the expression of insulin receptor substrate-1 and inhibiting GLUT4 plasma membrane translocation (77-79). GC effects are dependent on 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 (11β-HSD1), which might be a promising target to counteract GC-mediated adiposity and insulin resistance (74). In subcutaneous, but not in visceral adipose tissue, GC decreases lipolysis by reducing the expression of Hsl (80). This strongly suggests that the effects of GCs on adipose tissue metabolism are depot dependent.

Together, WAT physiology is regulated by numerous incoming oscillating signals in a circadian manner. Insulin and ghrelin, signaling the feeding:fasting state, activate lipogenic gene expression. Insulin and FGF21 increase lipid and glucose uptake at different times of day to maintain energy homeostasis. Glucagon and GCs, both peaking around activity onset, stimulate lipolysis to fuel the body in the transition from rest to the active state.

White Adipose Tissue Clocks Drive Rhythmic Gene Expression

Adipose physiology is regulated by adipocyte clocks. Together with the circadian-regulated incoming signals, adipose tissue adapts to daily variations of energy availability and needs to maintain energy homeostasis. Adipocyte clocks regulate the local transcriptome in a circadian manner including key enzymes of lipogenesis and lipolysis, for example, Atgl, Hsl, caveolin 2, acyl-CoA synthetase (Acsl1), phosphatidate phosphatase (Lpin1), Lpl, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (Pparα), PPAR gamma coactivator 1-β (Pgc1β), Srepb1-α, and Pparγ2 (81-86). BMAL1:CLOCK activate gene expression of Atgl and Hsl via binding to E-box promotor elements (81). Most of those diurnal rhythms are lost in obese individuals with type 2 diabetes (83, 87). The physiological significance of adipose tissue clocks has been demonstrated in numerous studies. Bmal1-deficient embryonic fibroblasts show impaired differentiation into adipocytes (82). BMAL1:CLOCK dimers regulate adipogenesis via the Wnt signaling pathway (88, 89). Genetic disruption of the circadian clock by mutations in Clock leads to increased adiposity on regular chow in a genetic background–dependent manner. In both strains, Clock mutants show blunted or lost rhythms in serum TGs, FAs, and glycerol, indicating impairments in fat absorption and lipolysis (81, 90). The latter was attributed to decreased transcription of Atgl and Hsl (81). Adipocyte-specific knockout of Bmal1 leads to obesity under high-fat diet conditions, probably due to changes in circulating polyunsaturated FAs that centrally affect food intake rhythms. This idea is supported by the aberrant expression of hypothalamic neuropeptides involved in appetite regulation in those mice (91). Together, the existence of a circadian adipocyte-hypothalamus axis emphasizes the importance of a functional adipose tissue clock for the circadian regulation of energy homeostasis.

Overexpression of Bmal1 increases the expression of lipogenesis-related genes in WAT (82). BMAL1:CLOCK induce Ppar expression via E-box binding (92, 93). PPARγ in particular is crucial for adipocyte differentiation and adipogenesis (94-96). PPARs also feed-back on Clock gene expression. PPARγ induces Rev-Erbα expression in adipose tissue whereas PPARα activates Bmal1 transcription in the liver (97, 98). PER2, being part of the negative limb of the core TTFL, directly inhibits expression of PPARγ target gene expression by suppressing PPARγ binding to PPAR response elements (99). The clock modulator–differentiated embryo chronodrocyte protein 1 (DEC1) prevents PPARγ-mediated target gene expression, thereby promoting circadian oscillations in these genes. In line with this, Dec1 deficiency leads to a pronounced increase in gene expression related to FA biosynthesis, lipid storage, and lipolysis in the dark phase as well as a loss of circadian variation in serum FAs (100). Expression of the nuclear receptors Rev-Erbα/β and RORα/β peaks at the end of the light phase in mice. Srebp-1c, Pparγ, as well as adiponectin and leptin also exhibit diurnal mRNA rhythms peaking at night (101). Genetic disruption of Rev-Erbα is associated with decreased SREBP1 and SREBP2 activity (102). REV-ERBα regulates SREBPs activity and bile acid metabolism in the liver (102). In muscle, REV-ERBβ is recruited to the Srebp-1c promotor, inducing gene expression (103). Thus, REV-ERB agonists may be promising candidates to treat obesity by increasing energy expenditure and, thereby, improving dyslipidemia and hyperglycemia through alterations in circadian gene expression of metabolic genes (104).

In summary, the circadian clock is important for adipocyte differentiation and the rhythmic expression of lipogenic and lipolytic genes. Clock proteins regulate the activity of proteins involved in WAT metabolism that, in turn, control rhythmic FA release. FAs signal the metabolic state to the brain, adjusting food intake. Circadian disruptions in WAT metabolism lead to alterations in adipogenesis, lipid mobilization, and food intake, promoting obesity.

Rhythmic Output from White Adipose Tissue Regulates Metabolism

Metabolic homeostasis is regulated by factors released by, inter alia, WAT in a circadian manner. Such factors modulate the physiology of other tissues and are integrated at a central level to control food intake. One of the main functions of WAT is the storage of lipids and release of lipolytic products. The latter—as FAs and glycerol—exhibits a prominent circadian rhythm in mice and humans that is only partly driven by food intake (81, 90, 100, 105). A loss of polyunsaturated FA (PUFA) rhythms induces alterations in the expression of appetite-regulating neuropeptides and increases food intake. Decreased PUFA levels are accompanied by reduced expression of long-chain fatty acid elongase 5/6 (Elovl5/6) and stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 (Scd1), key enzymes in PUFA biosynthesis (91, 106). Restoration of PUFA content in the hypothalamus rescues food intake rhythms, body weight development, appetite-regulated neuropeptide expression, and energy homeostasis (91). This clearly shows the crucial role of oscillating lipolytic output for whole-body metabolic homeostasis.

WAT is also an endocrine organ releasing adipokines in a circadian manner that contribute to the regulation of metabolism throughout the body (Fig. 2). Secretion of leptin, one of the best studied adipokines, is stimulated by insulin but is also regulated by adipose tissue clocks (107, 108). The diurnal leptin pattern is maintained under regular feeding of 6 meals a day but is abolished by lesioning the SCN, which suggests that leptin secretion is controlled by the circadian clock (109). In vitro studies reveal that the adipocyte clock regulates leptin secretion. Although mRNA expression of leptin is not rhythmic in adipocytes, leptin release changes throughout the day (107). Leptin levels correlate with body fat content and decrease during fasting (110-112). It crosses the blood-brain barrier and acts as a satiety hormone, regulating energy expenditure and food intake (113-116). Leptin binds to leptin receptors throughout the central nervous system, for example, in the arcuate nucleus. The arcuate nucleus contains neuropeptide Y (NPY)-/agouti-related peptide (AgRP)-positive and proopiomelanocortin (POMC)-/ cocaine- and amphetamine-related transcript (CART)-positive neurons, which regulate food intake and energy expenditure (117). Leptin suppresses food intake by inhibiting the expression of orexigenic neuropeptides Agrp and Npy and stimulating the expression of anorexigenic Pomc (118-121). Chronic jet lag promotes obesity probably by central leptin resistance and downregulation of leptin transcription (122). Leptin’s effects on energy expenditure may in part be mediated by BAT activation. A recent discovery suggests that the thermogenic effect of leptin may be regulated by PGC-1β expressing POMC-neurons (123). Furthermore, leptin stimulates β-adrenergic receptors and, thereby, increases expression of Ucp1 in BAT (124). Despite the effects on BAT, leptin activates β-oxidation in peripheral tissues, for example, muscle and liver, via adenosine monophosphate–activated protein kinase C (AMPK) signaling (125). Thereby, leptin prevents lipid accumulation in such tissues. Furthermore, leptin directly suppresses the release of GCs, which play an important role in glucose and lipid homeostasis (70, 126, 127). Adiponectin is expressed in a circadian manner in adipose tissue (128) as a target gene of PPARγ and PGC1β, which are regulated by the circadian clock (129). As mentioned earlier, it plays a crucial role in the regulation of energy expenditure and insulin sensitivity (56, 57). Adiponectin increases β-oxidation and glucose uptake and, thus, decreases body weight (130-132). It also induces browning of WAT via a sirtuin 1 (SIRT1)-AMPK–mediated upregulation of Ucp1 expression to affect energy expenditure (133, 134). However, in BAT itself, adiponectin seems to inhibit Ucp1 expression via inhibition of β-adrenergic receptor expression (135). Expression of adiponectin receptors (Adipor1 and 2) exhibits a circadian oscillation in adipose tissue and in the mediobasal hypothalamus (128, 136). The adipokine signals the peripheral metabolic state to the brain, which in combination with blood glucose levels results in adjustment of food intake (137, 138). Its action is mediated by AMPK signaling (139). Adiponectin also induces Bmal1 expression in the mediobasal hypothalamus that then locally regulates the expression of orexigenic neuropeptides (136). These findings suggest a mechanism by which peripheral circadian clock disruption my alter food intake rhythms, promoting the development of metabolic disorders.

Serum visfatin levels, encoded by nicotinamide phosphoriboysltransferase (Nampt), exhibit a diurnal rhythm that is inversely related to leptin (140-143). Nampt expression rhythms are shifted by sleep deprivation, negatively affecting glucose homeostasis (142). Visfatin/NAMPT also catalyzes the rate-limiting step in the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) salvage pathway. Nampt expression is regulated by the circadian clock and modulates the core TTFL by regulating the activity of the histone deacetylase SIRT1 (143). Its insulin-mimetic function is controversial and still under investigation (144-146). However, it has become more evident that visfatin has a proinflammatory function and most studies agree on a positive correlation between fat mass and visfatin levels (147-150). Infiltrated immune cells might be a major source of visfatin expression (149, 151). Circulating visfatin levels are positively correlated with proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and C-reactive protein, and visfatin expression is strongly correlated with expression of tumor necrosis factor α (Tnf-α) and Il-6 (148, 150, 152). Thus, increased visfatin may have deleterious effects on energy homeostasis. In fact, visfatin induces insulin resistance in the liver partly via induction of inflammatory pathways and induces FA-mediated neuroinflammation (152, 153).

Resistin reduces insulin sensitivity and shows a circadian rhythm trailing that of insulin and suggesting a negative feedback on insulin action (154). Circadian rhythms in resistin expression are stimulated by rhythmic input of insulin. In obesity, concomitant with insulin resistance, rhythmic resistin expression is blunted or abolished (155, 156). In humans, resistin is mainly expressed by macrophages whereas its main source in rodents are adipocytes. Gene and protein structures differ between humans and rodents, accounting for their different functional roles (157). Human resistin activates circadian expression of proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNFα, IL-6, and IL-12, which contribute to development of insulin resistance and inflammation (158, 159). In turn, such cytokines enhance resistin expression (160). Neutrophils are the first immune cells to infiltrate adipose tissues after a dietary challenge (161). Neutrophils, in turn, attract further immune cells including macrophages, which then reduce insulin sensitivity and induce chronic inflammation (162, 163). TNFα, predominantly released by macrophages, promotes lipolysis (164) and inhibits the expression of perilipin, a protein associated with fat storage (164, 165). Furthermore, it decreases GLUT4 and LPL expression (166). As such, high TNFα levels inhibit insulin-mediated glucose uptake (167, 168) and promote the development of insulin resistance, for example, in obese individuals (167, 169). GC treatment inhibits TNFα-mediated insulin resistance but also decreases its lipolytic effects, which contribute to fat accumulation (170).

Taken together, through rhythmic release of FAs and adipokine hormones, WAT plays a pivotal role in the circadian modulation of energy homeostasis. It regulates food intake rhythms, energy expenditure, insulin sensitivity, and metabolic inflammation. In laboratory rodents, WAT rhythm disruption promotes overeating and obesity.

Circadian Aspects of Brown Adipose Tissue Metabolism Crosstalk

The main function of BAT is the conversion of energy into heat by nonshivering thermogenesis (20). Heat production in BAT is achieved by β-oxidation or through uncoupling of mitochondrial proton transport from energy production by UCP1 (171). BAT heat generation allows mammals to keep their body temperature more constant and cope with cold temperature environments. On a cold stimulus, autonomic activation leads to a release of noradrenaline at BAT terminals. Activation of β 3-adrenergic receptors in brown adipocytes results in G protein–controlled activation of the protein kinase A pathway and further gene expression of metabolic genes, including Ucp1 (171). Additionally, this pathway activates ATGL to yield FAs that then further stimulate UCP1 (26, 171).

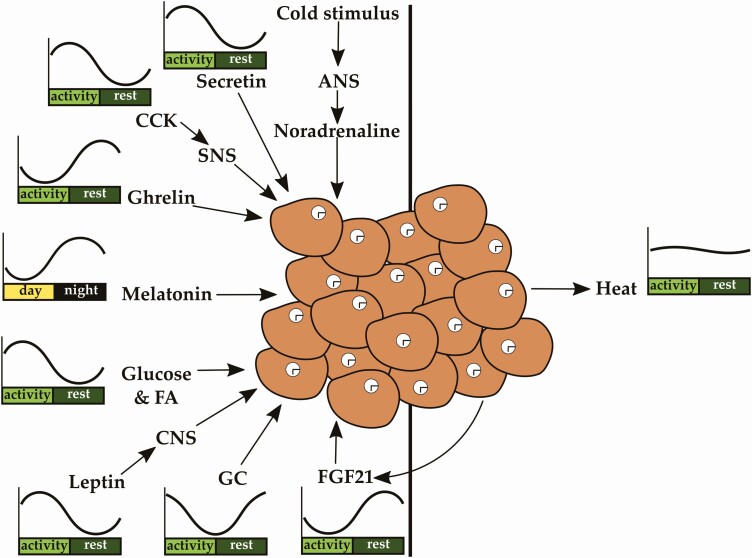

Heat production in BAT is also induced by a carbohydrate-rich meal (diet-induced thermogenesis or DIT; Fig. 3) through autonomic adrenergic activation (172, 173). Hormones originating from the gut as well as bile acids are also able to stimulate DIT (174). Gut-derived cholecystokinin (CCK) and secretin activate BAT thermogenesis via vagal afferents and sympathetic efferents and UCP1 activation (174). Ghrelin rhythms affect Ucp1 expression, and its secretion is reduced after food intake (175, 176). By using DIT, our body is able to partly reduce excessive energy uptake from food and thereby avoid energy storage in the form of fat (171). The induction of BAT postprandial thermogenesis leading to glucose and FA uptake might be stimulated by insulin (173). Interestingly, UCP1 seems to be essential because mice with ablated UCP1 no longer show diet-induced thermogenesis but gain weight instead (177). Endocrine circadian factors such as the pineal hormone melatonin (156, 157) modulate the capacity of BAT for nonshivering thermogenesis (171). In rodents, GCs downregulate UCP1 and, thereby, BAT thermogenesis. In humans, they have the opposite effect (178).

Figure 3.

Brown adipose tissue (BAT) function is modulated by numerous rhythmic signals originating from other peripheral or central tissues as well as circulating metabolites such as glucose and fatty acids (FAs). The circadian clock in brown adipocytes is essential for proper BAT function. BAT produces heat via nonshivering thermogenesis, affecting body temperature. ANS indicates autonomic nervous system; CCK, cholecystokinin; SNS, sympathetic nervous system.

Like WAT, BAT is also involved in the circadian regulation of energy metabolism. However, because BAT function is not primarily endocrine, the focus of metabolic regulation is connected to the clearance of metabolic factors from the bloodstream as well as affecting the capacity of thermogenesis in brown adipocytes. The circadian clock and metabolic regulation of BAT are tightly connected. Chronic rhythm disruption by repeated shifting of the light-dark cycle leads not only to whitening of the BAT but also reduces UCP1 expression in rats (179).

Glucose as well as TG/FA uptake in BAT is rhythmic, with a maximum at the end of the inactive or in the beginning of the active phase, respectively (180-183). Enzymes involved in TG breakdown such as LPL also show their maximum activity and expression in the beginning of the active phase (180, 183). This indicates a role of BAT in circadian gating of FA, TG, as well as glucose clearance (180, 183, 184). In line with this, thermogenesis is higher in the active phase (182). Because high BAT activity in humans is associated with reduced glycemia, these data suggest that sufficient BAT could stabilize glucose fluctuations throughout the day and thereby maintain glucose homeostasis (184). Interestingly, glucose uptake in human BAT is increased in the morning, correlating with high Ucp1 and Glut4 gene expression (184, 185). FGF21 seems to be important for BAT glucose clearance. It inhibits temperature decreases in BAT and ameliorates normal glucose clearance by controlling stable BAT temperature and, thereby, BAT thermogenesis (186). Interestingly, BAT thermogenic activity also increases the local release of FGF21, indicating the existence of a paracrine feedback (187).

Circadian thermogenic plasticity is controlled by REV-ERBα as shown in mice that cope better with cold temperatures at times of low REV-ERBα expression (189). REV-ERBα represses UCP1. In turn, cold temperatures downregulate Rev-Erbα, leading to an induction of UCP1 to increase thermogenesis. REV-ERBα depletion leads to the complete loss of body temperature rhythms and BAT activity with overall higher body temperature (189). This emphasizes the importance of the circadian regulation of BAT metabolism. Interestingly, the SCN itself is involved in plasma TG variations by regulating lipid uptake into BAT through the control of REV-ERBα (182, 190). This fuels the assumption that disturbed circadian rhythms contribute to hyperlipidemia (190).

In summary, circadian regulation of metabolism by BAT mainly involves regulating the uptake and clearance of glucose and lipids from the circulation. In addition, the capacity of thermogenesis is regulated by the circadian clock within BAT, but also by circadian hormones such as melatonin and GCs (see Fig. 3).

Conclusion

The role of WAT and BAT depots in the circadian regulation of metabolism becomes increasingly clear. Both fat depots harbor intrinsic clocks that regulate the tissue-specific transcription of many key genes involved in lipogenesis and lipolysis in WAT and thermogenesis in BAT. WAT regulates feeding behavior, carbohydrate metabolism, and energy expenditure by releasing adipokines and FAs in a circadian manner. In this way, metabolism is modulated as a function of the peripheral energy state through central integration of feedback signals to respond to the organism’s needs. BAT, in turn, contributes to the circadian regulation of energy substrates in the circulation. In recent years, research has mostly focused on characterizing the effects of (tissue) clock disruption on energy metabolism. Circadian studies have helped us understand how incoming signals and WAT physiology are integrated at the tissue level to generate coherent output that, in turn, regulates food intake and modulates the physiology of other organs involved in metabolic homeostasis. Thus, adipose tissues not only possess a lipid storage and thermogenesis function, but are important regulators of energy homeostasis. From a clinical point of view, it will be important to dissect the regulatory mechanisms controlling circadian rhythms in adipose tissues. Together, recent findings have changed our view on adipose tissue as storage tissue and emphasize its role as a possible therapeutic target. Such knowledge may help us devise adipose depot-specific chronopharmacological approaches to counteract the misbalanced energy homeostasis that has become so prevalent in modern societies. Clock modulators like nobiletin, a RORα/β agonist, may be putative therapeutic agents. Nobiletin promotes adipocyte differentiation, stimulates lipolysis by induction of, for example, Pparγ expression, improves insulin resistance, and decreases adipocytokine expression (191-194). Another possible therapeutic approach may be the use of light. Very recent findings show that light increases lipolysis and mitochondrial activity via Opsin3 signaling in adipose tissues (195, 196). Chronotargeted approaches might be useful to modulate adipose tissue activity, and future studies are needed to evaluate their beneficial effects in humans.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This work was supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG; grant Nos. GRK1957, OS353-7/1, OS353-10/1, and CRC296).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AgRP

agouti-related peptide

- AMPK

adenosine monophosphate–activated protein kinase C

- Atgl

adipose triglyceride lipase

- Bmal1

brain and muscle aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator-like protein 1

- BAT

brown adipose tissue

- CD36

cluster of differentiation 36

- Clock

circadian locomotor output cycles kaput

- Cry1/2

cryptochrome 1 and 2

- DIT

diet-induced thermogenesis

- FAs

fatty acids

- FGF21

fibroblast growth factor 21

- GCs

glucocorticoids

- GLUT4

glucose transporter 4

- IL

interleukin

- LPL

lipoprotein lipase

- mRNA

messenger RNA

- Nampt

nicotinamide phosphoriboysltransferase

- Npas2

neuronal PAS domain protein 2

- Per1-3

period 1-3

- PGC-1

PPAR gamma coactivator 1

- POMC

proopiomelanocortin

- PUFAs

polyunsaturated fatty acids

- REV-ERBα/β

reverse erythroblastoma

- RORα-γ

retinoic acid-related orphan receptors

- ROREs

retinoic acid-related orphan receptor response elements

- SCN

suprachiasmatic nucleus

- SNS

sympathetic nervous system

- SREBP-1c

stimulatory factor-1/2/regulatory element-binding protein-1c

- TGs

triglycerides

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor α

- TTFL

transcriptional-translational feedback loop

- UCP1

uncoupling protein 1

- WAT

white adipose tissue

Additional Information

Disclosures: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Data Availability

This review manuscript does not contain any original data. Data sharing is not applicable to this article because no data sets were generated or analyzed during the present study.

References

- 1. Partch CL, Green CB, Takahashi JS. Molecular architecture of the mammalian circadian clock. Trends Cell Biol. 2014;24(2):90-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Buhr ED, Takahashi JS. Molecular components of the mammalian circadian clock. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2013;(217):3-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lowrey PL, Takahashi JS. Genetics of the mammalian circadian system: photic entrainment, circadian pacemaker mechanisms, and posttranslational regulation. Annu Rev Genet. 2000;34:533-562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Takahashi JS. Transcriptional architecture of the mammalian circadian clock. Nat Rev Genet. 2017;18(3):164-179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jolley CC, Ukai-Tadenuma M, Perrin D, Ueda HR. A mammalian circadian clock model incorporating daytime expression elements. Biophys J. 2014;107(6):1462-1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yoshitane H, Asano Y, Sagami A, et al. Functional D-box sequences reset the circadian clock and drive mRNA rhythms. Commun Biol. 2019;2:300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mitsui S, Yamaguchi S, Matsuo T, Ishida Y, Okamura H. Antagonistic role of E4BP4 and PAR proteins in the circadian oscillatory mechanism. Genes Dev. 2001;15(8):995-1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ohno T, Onishi Y, Ishida N. A novel E4BP4 element drives circadian expression of mPeriod2. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(2):648-655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yamaguchi S, Mitsui S, Yan L, Yagita K, Miyake S, Okamura H. Role of DBP in the circadian oscillatory mechanism. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20(13):4773-4781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yamajuku D, Shibata Y, Kitazawa M, et al. Cellular DBP and E4BP4 proteins are critical for determining the period length of the circadian oscillator. FEBS Lett. 2011;585(14):2217-2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhang R, Lahens NF, Ballance HI, Hughes ME, Hogenesch JB. A circadian gene expression atlas in mammals: implications for biology and medicine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(45):16219-16224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mure LS, Le HD, Benegiamo G, et al. Diurnal transcriptome atlas of a primate across major neural and peripheral tissues. Science. 2018;359(6381):eaao0318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ralph MR, Foster RG, Davis FC, Menaker M. Transplanted suprachiasmatic nucleus determines circadian period. Science. 1990;247(4945):975-978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hughes S, Jagannath A, Hankins MW, Foster RG, Peirson SN. Photic regulation of clock systems. Methods Enzymol. 2015;552:125-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hattar S, Kumar M, Park A, et al. Central projections of melanopsin-expressing retinal ganglion cells in the mouse. J Comp Neurol. 2006;497(3):326-349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dibner C, Schibler U, Albrecht U. The mammalian circadian timing system: organization and coordination of central and peripheral clocks. Annu Rev Physiol. 2010;72:517-549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dibner C. The importance of being rhythmic: living in harmony with your body clocks. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2020;228(1):e13281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Challet E, Mendoza J. Metabolic and reward feeding synchronises the rhythmic brain. Cell Tissue Res. 2010;341(1):1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zwick RK, Guerrero-Juarez CF, Horsley V, Plikus MV. Anatomical, physiological, and functional diversity of adipose tissue. Cell Metab. 2018;27(1):68-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cedikova M, Kripnerová M, Dvorakova J, et al. Mitochondria in white, brown, and beige adipocytes. Stem Cells Int. 2016;2016:6067349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kahn BB, Flier JS. Obesity and insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 2000;106(4):473-481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schoettl T, Fischer IP, Ussar S. Heterogeneity of adipose tissue in development and metabolic function. J Exp Biol. 2018;221(Pt Suppl 1):jeb162958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Alves-Bezerra M, Cohen DE. Triglyceride metabolism in the liver. Compr Physiol. 2017;8(1):1-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kershaw EE, Flier JS. Adipose tissue as an endocrine organ. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(6):2548-2556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cannon B, Nedergaard J. Brown adipose tissue: function and physiological significance. Physiol Rev. 2004;84(1):277-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Klingenspor M, Fromme T, Hughes DA Jr, et al. An ancient look at UCP1. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1777(7-8):637-641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yamamoto H, Nagai K, Nakagawa H. Role of SCN in daily rhythms of plasma glucose, FFA, insulin and glucagon. Chronobiol Int. 1987;4(4):483-491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Petrenko V, Saini C, Giovannoni L, et al. Pancreatic α- and β-cellular clocks have distinct molecular properties and impact on islet hormone secretion and gene expression. Genes Dev. 2017;31(4):383-398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Boden G, Ruiz J, Urbain JL, Chen X. Evidence for a circadian rhythm of insulin secretion. Am J Physiol. 1996;271(2 Pt 1):E246-E252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Petrenko V, Gandasi NR, Sage D, Tengholm A, Barg S, Dibner C. In pancreatic islets from type 2 diabetes patients, the dampened circadian oscillators lead to reduced insulin and glucagon exocytosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(5):2484-2495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Saini C, Petrenko V, Pulimeno P, et al. A functional circadian clock is required for proper insulin secretion by human pancreatic islet cells. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2016;18(4):355-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chakrabarti P, Kim JY, Singh M, et al. Insulin inhibits lipolysis in adipocytes via the evolutionarily conserved mTORC1-Egr1-ATGL-mediated pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2013;33(18):3659-3666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Burns TW, Terry BE, Langley PE, Robison GA. Insulin inhibition of lipolysis of human adipocytes: the role of cyclic adenosine monophosphate. Diabetes. 1979;28(11):957-961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wang D, Sul HS. Insulin stimulation of the fatty acid synthase promoter is mediated by the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway. Involvement of protein kinase B/Akt. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(39):25420-25426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Meijssen S, Cabezas MC, Ballieux CG, Derksen RJ, Bilecen S, Erkelens DW. Insulin mediated inhibition of hormone sensitive lipase activity in vivo in relation to endogenous catecholamines in healthy subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86(9):4193-4197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nishino N, Tamori Y, Kasuga M. Insulin efficiently stores triglycerides in adipocytes by inhibiting lipolysis and repressing PGC-1α induction. Kobe J Med Sci. 2007;53(3):99-106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tansey JT, Huml AM, Vogt R, et al. Functional studies on native and mutated forms of perilipins. A role in protein kinase A-mediated lipolysis of triacylglycerols. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(10):8401-8406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Choi SM, Tucker DF, Gross DN, et al. Insulin regulates adipocyte lipolysis via an Akt-independent signaling pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30(21):5009-5020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Miyoshi H, Souza SC, Zhang HH, et al. Perilipin promotes hormone-sensitive lipase-mediated adipocyte lipolysis via phosphorylation-dependent and -independent mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(23):15837-15844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Czech MP, Tencerova M, Pedersen DJ, Aouadi M. Insulin signalling mechanisms for triacylglycerol storage. Diabetologia. 2013;56(5):949-964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Carrasco-Benso MP, Rivero-Gutierrez B, Lopez-Minguez J, et al. Human adipose tissue expresses intrinsic circadian rhythm in insulin sensitivity. FASEB J. 2016;30(9):3117-3123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Shi SQ, Ansari TS, McGuinness OP, Wasserman DH, Johnson CH. Circadian disruption leads to insulin resistance and obesity. Curr Biol. 2013;23(5):372-381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rudic RD, McNamara P, Curtis AM, et al. BMAL1 and CLOCK, two essential components of the circadian clock, are involved in glucose homeostasis. PloS Biol. 2004;2(11):e377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Weinges KF. The effect of glucagon and insulin on the metabolism of nonesterified fatty acids in isolated fatty tissue of the rat in vitro [article in German]. Klin Wochenschr. 1961;39:293-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Prigge WF, Grande F. Effects of glucagon, epinephrine and insulin on in vitro lipolysis of adipose tissue from mammals and birds. Comp Biochem Physiol B. 1971;39(1):69-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Krzeski R, Czyzyk-Krzeska MF, Trzebski A, Millhorn DE. Centrally administered glucagon stimulates sympathetic nerve activity in rat. Brain Res. 1989;504(2):297-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Fredholm B, Rosell S. Effects of adrenergic blocking agents on lipid mobilization from canine subcutaneous adipose tissue after sympathetic nerve stimulation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1968;159(1):1-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tong X, Muchnik M, Chen Z, et al. Transcriptional repressor E4-binding protein 4 (E4BP4) regulates metabolic hormone fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) during circadian cycles and feeding. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(47):36401-36409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Andersen B, Beck-Nielsen H, Højlund K. Plasma FGF21 displays a circadian rhythm during a 72-h fast in healthy female volunteers. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2011;75(4):514-519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Oishi K, Uchida D, Ishida N. Circadian expression of FGF21 is induced by PPARα activation in the mouse liver. FEBS Lett. 2008;582(25-26):3639-3642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Schlein C, Talukdar S, Heine M, et al. FGF21 lowers plasma triglycerides by accelerating lipoprotein catabolism in white and brown adipose tissues. Cell Metab. 2016;23(3): 441-453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Emanuelli B, Vienberg SG, Smyth G, et al. Interplay between FGF21 and insulin action in the liver regulates metabolism. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(2):515-527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Fisher FM, Kleiner S, Douris N, et al. FGF21 regulates PGC-1α and browning of white adipose tissues in adaptive thermogenesis. Genes Dev. 2012;26(3):271-281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. BonDurant LD, Ameka M, Naber MC, et al. FGF21 regulates metabolism through adipose-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Cell Metab. 2017;25(4):935-944.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Xu J, Stanislaus S, Chinookoswong N, et al. Acute glucose-lowering and insulin-sensitizing action of FGF21 in insulin-resistant mouse models—association with liver and adipose tissue effects. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;297(5):E1105-E1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lin Z, Tian H, Lam KS, et al. Adiponectin mediates the metabolic effects of FGF21 on glucose homeostasis and insulin sensitivity in mice. Cell Metab. 2013;17(5):779-789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Holland WL, Adams AC, Brozinick JT, et al. An FGF21-adiponectin-ceramide axis controls energy expenditure and insulin action in mice. Cell Metab. 2013;17(5):790-797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Nakazato M, Murakami N, Date Y, et al. A role for ghrelin in the central regulation of feeding. Nature. 2001;409(6817):194-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Kojima M, Hosoda H, Date Y, Nakazato M, Matsuo H, Kangawa K. Ghrelin is a growth-hormone-releasing acylated peptide from stomach. Nature. 1999;402(6762):656-660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Laermans J, Vancleef L, Tack J, Depoortere I. Role of the clock gene Bmal1 and the gastric ghrelin-secreting cell in the circadian regulation of the ghrelin-GOAT system. Sci Rep. 2015;5:16748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Theander-Carrillo C, Wiedmer P, Cettour-Rose P, et al. Ghrelin action in the brain controls adipocyte metabolism. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(7):1983-1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Tschöp M, Smiley DL, Heiman ML. Ghrelin induces adiposity in rodents. Nature. 2000;407(6806):908-913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Lin L, Saha PK, Ma X, et al. Ablation of ghrelin receptor reduces adiposity and improves insulin sensitivity during aging by regulating fat metabolism in white and brown adipose tissues. Aging Cell. 2011;10(6):996-1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Oster H, Damerow S, Kiessling S, et al. The circadian rhythm of glucocorticoids is regulated by a gating mechanism residing in the adrenal cortical clock. Cell Metab. 2006;4(2):163-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Son GH, Chung S, Choe HK, et al. Adrenal peripheral clock controls the autonomous circadian rhythm of glucocorticoid by causing rhythmic steroid production. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(52):20970-20975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Dumbell R, Leliavski A, Matveeva O, Blaum C, Tsang AH, Oster H. Dissociation of molecular and endocrine circadian rhythms in male mice lacking Bmal1 in the adrenal cortex. Endocrinology. 2016;157(11):4222-4233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Leliavski A, Shostak A, Husse J, Oster H. Impaired glucocorticoid production and response to stress in Arntl-deficient male mice. Endocrinology. 2014;155(1):133-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Hauner H, Schmid P, Pfeiffer EF. Glucocorticoids and insulin promote the differentiation of human adipocyte precursor cells into fat cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1987;64(4):832-835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Campbell JE, Peckett AJ, D’souza AM, Hawke TJ, Riddell MC. Adipogenic and lipolytic effects of chronic glucocorticoid exposure. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2011;300(1):C198-C209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Gathercole LL, Morgan SA, Bujalska IJ, Hauton D, Stewart PM, Tomlinson JW. Regulation of lipogenesis by glucocorticoids and insulin in human adipose tissue. PloS One. 2011;6(10):e26223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Tholen S, Kovary K, Rabiee A, Bielczyk-Maczyńska E, Yang W, Teruel MN. Flattened circadian glucocorticoid oscillations cause obesity due to increased lipid turnover and lipid uptake. bioRxiv 2020:2020.01.02.893081.

- 72. Wu T, Yang L, Jiang J, et al. Chronic glucocorticoid treatment induced circadian clock disorder leads to lipid metabolism and gut microbiota alterations in rats. Life Sci. 2018;192:173-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Slavin BG, Ong JM, Kern PA. Hormonal regulation of hormone-sensitive lipase activity and mRNA levels in isolated rat adipocytes. J Lipid Res. 1994;35(9):1535-1541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Wang Y, Yan C, Liu L, et al. 11β-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 shRNA ameliorates glucocorticoid-induced insulin resistance and lipolysis in mouse abdominal adipose tissue. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2015;308(1):E84-E95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Ottosson M, Mårin P, Karason K, Elander A, Björntorp P. Blockade of the glucocorticoid receptor with RU 486: effects in vitro and in vivo on human adipose tissue lipoprotein lipase activity. Obes Res. 1995;3(3):233-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Fried SK, Russell CD, Grauso NL, Brolin RE. Lipoprotein lipase regulation by insulin and glucocorticoid in subcutaneous and omental adipose tissues of obese women and men. J Clin Invest. 1993;92(5):2191-2198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Turnbow MA, Keller SR, Rice KM, Garner CW. Dexamethasone down-regulation of insulin receptor substrate-1 in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(4):2516-2520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Sakoda H, Ogihara T, Anai M, et al. Dexamethasone-induced insulin resistance in 3T3-L1 adipocytes is due to inhibition of glucose transport rather than insulin signal transduction. Diabetes. 2000;49(10):1700-1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Olefsky JM. Effect of dexamethasone on insulin binding, glucose transport, and glucose oxidation of isolated rat adipocytes. J Clin Invest. 1975;56(6):1499-1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Samra JS, Clark ML, Humphreys SM, MacDonald IA, Bannister PA, Frayn KN. Effects of physiological hypercortisolemia on the regulation of lipolysis in subcutaneous adipose tissue. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83(2):626-631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Shostak A, Meyer-Kovac J, Oster H. Circadian regulation of lipid mobilization in white adipose tissues. Diabetes. 2013;62(7):2195-2203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Shimba S, Ishii N, Ohta Y, et al. Brain and muscle Arnt-like protein-1 (BMAL1), a component of the molecular clock, regulates adipogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(34):12071-12076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Stenvers DJ, Jongejan A, Atiqi S, et al. Diurnal rhythms in the white adipose tissue transcriptome are disturbed in obese individuals with type 2 diabetes compared with lean control individuals. Diabetologia. 2019;62(4):704-716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Loboda A, Kraft WK, Fine B, et al. Diurnal variation of the human adipose transcriptome and the link to metabolic disease. BMC Med Genomics. 2009;2:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Christou S, Wehrens SMT, Isherwood C, et al. Circadian regulation in human white adipose tissue revealed by transcriptome and metabolic network analysis. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):2641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Zvonic S, Ptitsyn AA, Conrad SA, et al. Characterization of peripheral circadian clocks in adipose tissues. Diabetes. 2006;55(4):962-970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Otway DT, Mäntele S, Bretschneider S, et al. Rhythmic diurnal gene expression in human adipose tissue from individuals who are lean, overweight, and type 2 diabetic. Diabetes. 2011;60(5):1577-1581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Guo B, Chatterjee S, Li L, et al. The clock gene, brain and muscle Arnt-like 1, regulates adipogenesis via Wnt signaling pathway. FASEB J. 2012;26(8):3453-3463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Ross SE, Hemati N, Longo KA, et al. Inhibition of adipogenesis by Wnt signaling. Science. 2000;289(5481): 950-953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Oishi K, Atsumi G, Sugiyama S, et al. Disrupted fat absorption attenuates obesity induced by a high-fat diet in Clock mutant mice. FEBS Lett. 2006;580(1):127-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Paschos GK, Ibrahim S, Song WL, et al. Obesity in mice with adipocyte-specific deletion of clock component Arntl. Nat Med. 2012;18(12):1768-1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Oishi K, Shirai H, Ishida N. CLOCK is involved in the circadian transactivation of peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα) in mice. Biochem J. 2005;386(Pt 3):575-581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Inoue I, Shinoda Y, Ikeda M, et al. CLOCK/BMAL1 is involved in lipid metabolism via transactivation of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) response element. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2005;12(3):169-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Rosen ED, Sarraf P, Troy AE, et al. PPARγ is required for the differentiation of adipose tissue in vivo and in vitro. Mol Cell. 1999;4(4):611-617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Barak Y, Nelson MC, Ong ES, et al. PPARγ is required for placental, cardiac, and adipose tissue development. Mol Cell. 1999;4(4):585-595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Medina-Gomez G, Gray SL, Yetukuri L, et al. PPAR gamma 2 prevents lipotoxicity by controlling adipose tissue expandability and peripheral lipid metabolism. PloS Genet. 2007;3(4):e64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Canaple L, Rambaud J, Dkhissi-Benyahya O, et al. Reciprocal regulation of brain and muscle Arnt-like protein 1 and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α defines a novel positive feedback loop in the rodent liver circadian clock. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20(8):1715-1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Fontaine C, Dubois G, Duguay Y, et al. The orphan nuclear receptor Rev-Erbα is a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) γ target gene and promotes PPARγ-induced adipocyte differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(39):37672-37680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Grimaldi B, Bellet MM, Katada S, et al. PER2 controls lipid metabolism by direct regulation of PPARγ. Cell Metab. 2010;12(5):509-520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Noshiro M, Kawamoto T, Nakashima A, et al. DEC1 regulates the rhythmic expression of PPARγ target genes involved in lipid metabolism in white adipose tissue. Genes Cells. 2020;25(4):232-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Yang X, Downes M, Yu RT, et al. Nuclear receptor expression links the circadian clock to metabolism. Cell. 2006;126(4):801-810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Le Martelot G, Claudel T, Gatfield D, et al. REV-ERBα participates in circadian SREBP signaling and bile acid homeostasis. PloS Biol. 2009;7(9):e1000181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Ramakrishnan SN, Lau P, Crowther LM, et al. Rev-erb beta regulates the Srebp-1c promoter and mRNA expression in skeletal muscle cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;388(4):654-659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Solt LA, Wang Y, Banerjee S, et al. Regulation of circadian behaviour and metabolism by synthetic REV-ERB agonists. Nature. 2012;485(7396):62-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Dallmann R, Viola AU, Tarokh L, Cajochen C, Brown SA. The human circadian metabolome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(7):2625-2629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Hatori M, Vollmers C, Zarrinpar A, et al. Time-restricted feeding without reducing caloric intake prevents metabolic diseases in mice fed a high-fat diet. Cell Metab. 2012;15(6): 848-860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Otway DT, Frost G, Johnston JD. Circadian rhythmicity in murine pre-adipocyte and adipocyte cells. Chronobiol Int. 2009;26(7):1340-1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Cammisotto PG, Bukowiecki LJ. Mechanisms of leptin secretion from white adipocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2002;283(1):C244-C250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Kalsbeek A, Fliers E, Romijn JA, et al. The suprachiasmatic nucleus generates the diurnal changes in plasma leptin levels. Endocrinology. 2001;142(6):2677-2685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Frederich RC, Hamann A, Anderson S, Löllmann B, Lowell BB, Flier JS. Leptin levels reflect body lipid content in mice: evidence for diet-induced resistance to leptin action. Nat Med. 1995;1(12):1311-1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Maffei M, Halaas J, Ravussin E, et al. Leptin levels in human and rodent: measurement of plasma leptin and ob RNA in obese and weight-reduced subjects. Nat Med. 1995;1(11):1155-1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Boden G, Chen X, Mozzoli M, Ryan I. Effect of fasting on serum leptin in normal human subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81(9):3419-3423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Mistry AM, Swick AG, Romsos DR. Leptin rapidly lowers food intake and elevates metabolic rates in lean and ob/ob mice. J Nutr. 1997;127(10):2065-2072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Meister B. Control of food intake via leptin receptors in the hypothalamus. Vitam Horm. 2000;59:265-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Campfield LA, Smith FJ, Guisez Y, Devos R, Burn P. Recombinant mouse OB protein: evidence for a peripheral signal linking adiposity and central neural networks. Science. 1995;269(5223):546-549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Woods SC, Lotter EC, McKay LD, Porte D Jr. Chronic intracerebroventricular infusion of insulin reduces food intake and body weight of baboons. Nature. 1979;282(5738):503-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Arble DM, Sandoval DA. CNS control of glucose metabolism: response to environmental challenges. Front Neurosci. 2013;7:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Morrison CD, Morton GJ, Niswender KD, Gelling RW, Schwartz MW. Leptin inhibits hypothalamic Npy and Agrp gene expression via a mechanism that requires phosphatidylinositol 3-OH-kinase signaling. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;289(6):E1051-E1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Korner J, Savontaus E, Chua SC Jr, Leibel RL, Wardlaw SL. Leptin regulation of Agrp and Npy mRNA in the rat hypothalamus. J Neuroendocrinol. 2001;13(11):959-966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Cowley MA, Smart JL, Rubinstein M, et al. Leptin activates anorexigenic POMC neurons through a neural network in the arcuate nucleus. Nature. 2001;411(6836):480-484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Schwartz MW, Seeley RJ, Woods SC, et al. Leptin increases hypothalamic pro-opiomelanocortin mRNA expression in the rostral arcuate nucleus. Diabetes. 1997;46(12):2119-2123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Kettner NM, Mayo SA, Hua J, Lee C, Moore DD, Fu L. Circadian dysfunction induces leptin resistance in mice. Cell Metab. 2015;22(3):448-459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Delezie J, Gill JF, Santos G, Karrer-Cardel B, Handschin C. PGC-1β-expressing POMC neurons mediate the effect of leptin on thermoregulation in the mouse. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):16888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Scarpace PJ, Matheny M, Pollock BH, Tümer N. Leptin increases uncoupling protein expression and energy expenditure. Am J Physiol. 1997;273(1 Pt 1):E226-E230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Minokoshi Y, Kim YB, Peroni OD, et al. Leptin stimulates fatty-acid oxidation by activating AMP-activated protein kinase. Nature. 2002;415(6869):339-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Bornstein SR, Uhlmann K, Haidan A, Ehrhart-Bornstein M, Scherbaum WA. Evidence for a novel peripheral action of leptin as a metabolic signal to the adrenal gland: leptin inhibits cortisol release directly. Diabetes. 1997;46(7):1235-1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Opata AA, Cheesman KC, Geer EB. Glucocorticoid regulation of body composition and metabolism. In: Geer EB, ed. The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis in Health and Disease: Cushing’s Syndrome and Beyond. Springer International Publishing; 2017:3-26. [Google Scholar]

- 128. Gómez-Abellán P, Gómez-Santos C, Madrid JA, et al. Circadian expression of adiponectin and its receptors in human adipose tissue. Endocrinology. 2010;151(1):115-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Barnea M, Chapnik N, Genzer Y, Froy O. The circadian clock machinery controls adiponectin expression. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2015;399:284-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Yamauchi T, Kamon J, Waki H, et al. The fat-derived hormone adiponectin reverses insulin resistance associated with both lipoatrophy and obesity. Nat Med. 2001;7(8):941-946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Fruebis J, Tsao TS, Javorschi S, et al. Proteolytic cleavage product of 30-kDa adipocyte complement-related protein increases fatty acid oxidation in muscle and causes weight loss in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(4):2005-2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Berg AH, Combs TP, Du X, Brownlee M, Scherer PE. The adipocyte-secreted protein Acrp30 enhances hepatic insulin action. Nat Med. 2001;7(8):947-953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Liu L, Zhang T, Hu J, et al. Adiponectin/SIRT1 axis induces white adipose browning after vertical sleeve gastrectomy of obese rats with type 2 diabetes. Obes Surg. 2020;30(4):1392-1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Masaki T, Chiba S, Yasuda T, et al. Peripheral, but not central, administration of adiponectin reduces visceral adiposity and upregulates the expression of uncoupling protein in agouti yellow (Ay/a) obese mice. Diabetes. 2003;52(9):2266-2273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Qiao L, Yoo Hs, Bosco C, et al. Adiponectin reduces thermogenesis by inhibiting brown adipose tissue activation in mice. Diabetologia. 2014;57(5):1027-1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Tsang AH, Koch CE, Kiehn JT, Schmidt CX, Oster H. An adipokine feedback regulating diurnal food intake rhythms in mice. eLife. 2020;9:e55388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Suyama S, Lei W, Kubota N, Kadowaki T, Yada T. Adiponectin at physiological level glucose-independently enhances inhibitory postsynaptic current onto NPY neurons in the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus. Neuropeptides. 2017;65:1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Suyama S, Maekawa F, Maejima Y, Kubota N, Kadowaki T, Yada T. Glucose level determines excitatory or inhibitory effects of adiponectin on arcuate POMC neuron activity and feeding. Sci Rep. 2016;6:30796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Kubota N, Yano W, Kubota T, et al. Adiponectin stimulates AMP-activated protein kinase in the hypothalamus and increases food intake. Cell Metab. 2007;6(1):55-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Haider DG, Schaller G, Kapiotis S, Maier C, Luger A, Wolzt M. The release of the adipocytokine visfatin is regulated by glucose and insulin. Diabetologia. 2006;49(8):1909-1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Kralisch S, Klein J, Lossner U, et al. Hormonal regulation of the novel adipocytokine visfatin in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. J Endocrinol. 2005;185(3):R1-R8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Benedict C, Shostak A, Lange T, et al. Diurnal rhythm of circulating nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (Nampt/visfatin/PBEF): impact of sleep loss and relation to glucose metabolism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(2):E218-E222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143. Ramsey KM, Yoshino J, Brace CS, et al. Circadian clock feedback cycle through NAMPT-mediated NAD+ biosynthesis. Science. 2009;324(5927):651-654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144. Skop V, Kontrová K, Zídek V, et al. Autocrine effects of visfatin on hepatocyte sensitivity to insulin action. Physiol Res. 2010;59(4):615-618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145. Harasim E, Chabowski A, Górski J. Lack of downstream insulin-mimetic effects of visfatin/eNAMPT on glucose and fatty acid metabolism in skeletal muscles. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2011;202(1):21-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146. Sonoli SS, Shivprasad S, Prasad CV, Patil AB, Desai PB, Somannavar MS. Visfatin–a review. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2011;15(1):9-14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147. Filippatos TD, Derdemezis CS, Gazi IF, et al. Increased plasma visfatin levels in subjects with the metabolic syndrome. Eur J Clin Invest. 2008;38(1):71-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148. Chang YC, Chang TJ, Lee WJ, Chuang LM. The relationship of visfatin/pre-B-cell colony-enhancing factor/nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase in adipose tissue with inflammation, insulin resistance, and plasma lipids. Metabolism. 2010;59(1):93-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149. Friebe D, Neef M, Kratzsch J, et al. Leucocytes are a major source of circulating nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT)/pre-B cell colony (PBEF)/visfatin linking obesity and inflammation in humans. Diabetologia. 2011;54(5):1200-1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150. Terra X, Auguet T, Quesada I, et al. Increased levels and adipose tissue expression of visfatin in morbidly obese women: the relationship with pro-inflammatory cytokines. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2012;77(5):691-698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151. Curat CA, Wegner V, Sengenès C, et al. Macrophages in human visceral adipose tissue: increased accumulation in obesity and a source of resistin and visfatin. Diabetologia. 2006;49(4):744-747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152. Heo YJ, Choi SE, Jeon JY, et al. Visfatin induces inflammation and insulin resistance via the NF-κB and STAT3 signaling pathways in hepatocytes. J Diabetes Res. 2019;2019:4021623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153. Tran A, He W, Jiang N, Chen JTC, Belsham DD. NAMPT and BMAL1 are independently involved in the palmitate-mediated induction of neuroinflammation in hypothalamic neurons. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020;11:351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154. Oliver P, Ribot J, Rodríguez AM, Sánchez J, Picó C, Palou A. Resistin as a putative modulator of insulin action in the daily feeding/fasting rhythm. Pflugers Arch. 2006;452(3): 260-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155. Steppan CM, Bailey ST, Bhat S, et al. The hormone resistin links obesity to diabetes. Nature. 2001;409(6818):307-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156. Ando H, Yanagihara H, Hayashi Y, et al. Rhythmic messenger ribonucleic acid expression of clock genes and adipocytokines in mouse visceral adipose tissue. Endocrinology. 2005;146(12):5631-5636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157. Huang X, Yang Z. Resistin’s, obesity and insulin resistance: the continuing disconnect between rodents and humans. J Endocrinol Invest. 2016;39(6):607-615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158. Silswal N, Singh AK, Aruna B, Mukhopadhyay S, Ghosh S, Ehtesham NZ. Human resistin stimulates the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-alpha and IL-12 in macrophages by NF-kappaB-dependent pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;334(4):1092-1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159. Tripathi D, Kant S, Pandey S, Ehtesham NZ. Resistin in metabolism, inflammation, and disease. FEBS J. 2020;287(15):3141-3149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160. Kaser S, Kaser A, Sandhofer A, Ebenbichler CF, Tilg H, Patsch JR. Resistin messenger-RNA expression is increased by proinflammatory cytokines in vitro. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;309(2):286-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161. Elgazar-Carmon V, Rudich A, Hadad N, Levy R. Neutrophils transiently infiltrate intra-abdominal fat early in the course of high-fat feeding. J Lipid Res. 2008;49(9):1894-1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162. Xu H, Barnes GT, Yang Q, et al. Chronic inflammation in fat plays a crucial role in the development of obesity-related insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 2003;112(12):1821-1830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163. Weisberg SP, McCann D, Desai M, Rosenbaum M, Leibel RL, Ferrante AW Jr. Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue. J Clin Invest. 2003;112(12):1796-1808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164. Souza SC, Moitoso de Vargas L, Yamamoto MT, et al. Overexpression of perilipin A and B blocks the ability of tumor necrosis factor α to increase lipolysis in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(38):24665-24669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165. Brasaemle DL, Rubin B, Harten IA, Gruia-Gray J, Kimmel AR, Londos C. Perilipin A increases triacylglycerol storage by decreasing the rate of triacylglycerol hydrolysis. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(49):38486-38493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166. Hauner H, Petruschke T, Russ M, Röhrig K, Eckel J. Effects of tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) on glucose transport and lipid metabolism of newly-differentiated human fat cells in cell culture. Diabetologia. 1995;38(7):764-771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167. Hotamisligil GS. The role of TNFα and TNF receptors in obesity and insulin resistance. J Intern Med. 1999;245(6):621-625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168. Hotamisligil GS, Arner P, Caro JF, Atkinson RL, Spiegelman BM. Increased adipose tissue expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in human obesity and insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 1995;95(5):2409-2415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169. Kern PA, Saghizadeh M, Ong JM, Bosch RJ, Deem R, Simsolo RB. The expression of tumor necrosis factor in human adipose tissue. Regulation by obesity, weight loss, and relationship to lipoprotein lipase. J Clin Invest. 1995;95(5):2111-2119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170. Lee MJ, Fried SK. Glucocorticoids antagonize tumor necrosis factor-α-stimulated lipolysis and resistance to the antilipolytic effect of insulin in human adipocytes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2012;303(9):E1126-E1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171. Tan DX, Manchester LC, Fuentes-Broto L, Paredes SD, Reiter RJ. Significance and application of melatonin in the regulation of brown adipose tissue metabolism: relation to human obesity. Obes Rev. 2011;12(3):167-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172. Rothwell NJ, Stock MJ. A role for brown adipose tissue in diet-induced thermogenesis. Nature. 1979;281(5726):31-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173. U Din M, Saari T, Raiko J, et al. Postprandial oxidative metabolism of human brown fat indicates thermogenesis. Cell Metab. 2018;28(2):207-216.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174. Saito M, Matsushita M, Yoneshiro T, Okamatsu-Ogura Y. Brown adipose tissue, diet-induced thermogenesis, and thermogenic food ingredients: from mice to men. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020;11:222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175. Qian J, Morris CJ, Caputo R, Garaulet M, Scheer FAJL. Ghrelin is impacted by the endogenous circadian system and by circadian misalignment in humans. Int J Obes (Lond). 2019;43(8):1644-1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 176. Lin L, Lee JH, Bongmba OY, et al. The suppression of ghrelin signaling mitigates age-associated thermogenic impairment. Aging (Albany NY). 2014;6(12):1019-1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 177. Feldmann HM, Golozoubova V, Cannon B, Nedergaard J. UCP1 ablation induces obesity and abolishes diet-induced thermogenesis in mice exempt from thermal stress by living at thermoneutrality. Cell Metab. 2009;9(2):203-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 178. Ramage LE, Akyol M, Fletcher AM, et al. Glucocorticoids acutely increase brown adipose tissue activity in humans, revealing species-specific differences in UCP-1 regulation. Cell Metab. 2016;24(1):130-141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 179. Herrero L, Valcarcel L, da Silva CA, et al. Altered circadian rhythm and metabolic gene profile in rats subjected to advanced light phase shifts. PloS One. 2015;10(4): e0122570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 180. van den Berg R, Kooijman S, Noordam R, et al. A diurnal rhythm in brown adipose tissue causes rapid clearance and combustion of plasma lipids at wakening. Cell Rep. 2018;22(13):3521-3533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 181. van der Veen DR, Shao J, Chapman S, Leevy WM, Duffield GE. A diurnal rhythm in glucose uptake in brown adipose tissue revealed by in vivo PET-FDG imaging. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2012;20(7):1527-1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 182. Dollet L, Zierath JR. Interplay between diet, exercise and the molecular circadian clock in orchestrating metabolic adaptations of adipose tissue. J Physiol. 2019;597(6): 1439-1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 183. Bartelt A, Bruns OT, Reimer R, et al. Brown adipose tissue activity controls triglyceride clearance. Nat Med. 2011;17(2):200-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 184. Lee P, Bova R, Schofield L, et al. Brown adipose tissue exhibits a glucose-responsive thermogenic biorhythm in humans. Cell Metab. 2016;23(4):602-609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 185. van den Berg R, Kooijman S, Noordam R, et al. A diurnal rhythm in brown adipose tissue causes rapid clearance and combustion of plasma lipids at wakening. Cell Rep. 2018;22(13): 3521-3533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 186. Kwon MM, O’Dwyer SM, Baker RK, Covey SD, Kieffer TJ. FGF21-mediated improvements in glucose clearance require uncoupling protein 1. Cell Rep. 2015;13(8):1521-1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 187. Hondares E, Iglesias R, Giralt A, et al. Thermogenic activation induces FGF21 expression and release in brown adipose tissue. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(15):12983-12990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 188. Cui X, Nguyen NLT, Zarebidaki E, et al. Thermoneutrality decreases thermogenic program and promotes adiposity in high-fat diet-fed mice. Physiol Rep. 2016;4(10):e12799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 189. Gerhart-Hines Z, Feng D, Emmett MJ, et al. The nuclear receptor Rev-erbα controls circadian thermogenic plasticity. Nature. 2013;503(7476):410-413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 190. Moran-Ramos S, Guerrero-Vargas NN, Mendez-Hernandez R, Basualdo MDC, Escobar C, Buijs RM. The suprachiasmatic nucleus drives day-night variations in postprandial triglyceride uptake into skeletal muscle and brown adipose tissue. Exp Physiol. 2017;102(12):1584-1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 191. Miyata Y, Tanaka H, Shimada A, et al. Regulation of adipocytokine secretion and adipocyte hypertrophy by polymethoxyflavonoids, nobiletin and tangeretin. Life Sci. 2011;88(13-14):613-618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]