Abstract

Background

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) is the most aggressive lung tumor, characterized by a rapid doubling time and the development of widespread metastases, for which immune checkpoint inhibitors have been approved to overcome T cell anergy. In light of its dismal prognosis, and lack of curative options, new therapies for extensive-disease SCLC are desperately needed.

Methods

RRx-001 is a small molecule Myc inhibitor and down-regulates CD47 expression on tumor cells. We evaluated the programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) status of circulating tumor cells (CTCs) pre and post RRx-001 treatment in a phase 2 clinical trial, called QUADRUPLE THREAT, where patients with previously treated SCLC received RRx-001 in combination with a platinum doublet. The trial was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT02489903. Fourteen patients with SCLC were analyzed to investigate the association between clinical outcome and PD-L1 expression on CTCs pre and post RRx-001. The correlation between the binary clinical outcome (clinical benefit vs. progressive disease) and the change of PD-L1 expression on CTCs after RRx-001 was analyzed using a logistic regression adjusting for baseline PD-L1 expression.

Results

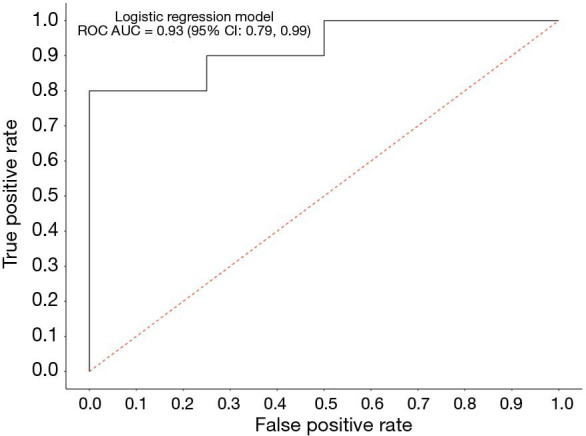

The logistic model McFadden goodness of fit score was 0.477. The logistic model analyzing the association between decreased PD-L1 expression on CTCs after RRx-001 and response to reintroduced platinum doublet had an approximate 92.8% accuracy in its prediction of clinical benefit. The estimated receiver operating characteristic (ROC) displayed a ROC area under the curve (AUC) of 0.93 (95% confidence interval, 0.78–0.99).

Conclusions

These results suggest that PD-L1 expression on CTCs decreased after RRx-001 was significantly correlated with response to reintroduced platinum-based doublet therapy. Monitoring PD-L1 expression on CTCs during RRx-001 treatment may serve as a biomarker to predict response to RRx-001-based cancer therapy.

Keywords: Circulating tumor cell (CTC), small cell lung cancer (SCLC), RRx-001, Myc, CD47, programmed death-ligand-1 (PD-L1)

Introduction

RRx-001 is a small molecule Myc inhibitor (1-3). RRx-001 down-regulates CD47, also known as a “don’t eat me” signal and repolarizes tumor-associated macrophages (TAM) from M2 to M1 (4,5). RRx-001 was given with cisplatin or carboplatin plus etoposide to twenty-six patients in a non-randomized phase 2 clinical trial called QUADRUPLE THREAT (QT; NCT02489903) including previously treated small cell lung cancer (SCLC) patients. SCLC is the fastest-growing lung tumor subtype with a doubling time in the range of 25 to 217 days (6) and a propensity for early dissemination and relapse, despite initial response rates of around 80%. SCLC has been designated as a recalcitrant tumor type by the National Institutes of Health due to its exceptional aggressivity, recidivism and lethality (7). The prognosis remains dismal even with the recent FDA approval of three checkpoint inhibitors since overall response rate (ORR), progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) are not markedly altered (8). Hence, additional therapies to interrupt the inevitability of the sharp downward trajectory of SCLC and improve the clinical course are urgently needed.

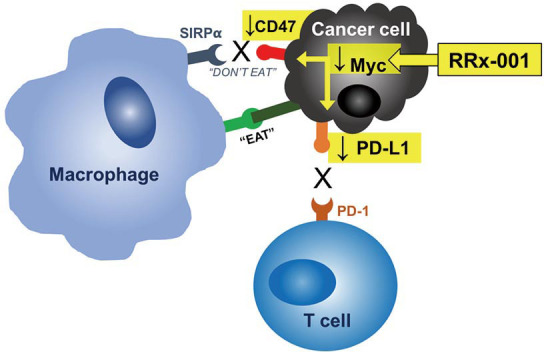

Immune evasion is a hallmark of cancer (9), which is the raison d’etre for immune checkpoint inhibitors especially in potentially susceptible tumor types such as SCLC. In SCLC, a profoundly immunosuppressive environment is present (9,10), which accounts in part for the overall poorness of responses to standard therapies. Among the most important contributors to immune evasion are immune checkpoints, such as programmed death-ligand-1 (PD-L1), which binds to programmed death-1 (PD-1) on T cells, B cells, dendritic cells, and natural killer T cells and induces systemic and local tolerance (11). PD-L1 expression has been demonstrated in SCLC and associated with poor outcomes (12). Importantly, RRx-001 is a Myc inhibitor and Myc has been shown to regulate the mRNA expression of PD-L1 (Figure 1) (13). Therefore, we investigated the association between clinical outcome and the change of PD-L1 expression on CTCs from baseline in SCLC patients treated with RRx-001.

Figure 1.

Hypothetical schema of RRx-001 impact on a circulating tumor cell. RRx-001 may downregulate CD47 and PD-L1 through inhibiting Myc. PD-L1, programmed death-ligand-1.

The enumeration and characterization of circulating tumor cells (CTCs), cells that are shed from the primary or metastatic tumor, provided a minimally invasive and, therefore, repeatable, method despite being present in extremely low numbers (approximately 1 CTC to, rarely, greater than 40 CTCs per 1 mL in SCLC patients) (3,14), enabling the sampling of tumor cells from peripheral blood and monitoring PD-L1 expression on tumor cells over time on the clinical study. In this study we evaluated the PD-L1 status of CTCs pre and post RRx-001 treatment in a phase 2 clinical trial, called QUADRUPLE THREAT, where patients with previously treated extensive-disease SCLC received RRx-001 in combination with a platinum doublet. We present the following article in accordance with the REMARK reporting checklist (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tlcr-20-359).

Methods

Patients

In an open label, non-randomized phase 2 study called QUADRUPLE THREAT (QT) (NCT02489903), the data were available for 14 patients with SCLC in third-line or beyond who had previously progressed on a platinum doublet i.e., cisplatin/carboplatin plus etoposide. The patients received weekly 4 mg RRx-001 followed by a reintroduced platinum doublet. Tumor response was evaluated according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECISTv1.1) measured every 6 weeks. PFS and OS were followed for up to 2 years. Collected data are Health Information Portability and Accessibility Act (HIPAA) protected and anonymized for inclusion. Among twenty-six patients consented for this study under Institutional Review Board (IRB)-approved protocols, 14 patients are included in this analysis, as the remaining enrolled patients had different (non-SCLC) tumor types. The study was approved by the respective institutional review board at each institution that participated in the clinical trial (registration number NCT02489903) and individual consent for this retrospective analysis was waived. All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013).

Analysis of CTCs

Fourteen patients with SCLC were analyzed to investigate the association between clinical response and PD-L1 expression on CTCs pre (Cycle 1 Day 1 or C1D1) and post (Cycle 3 Day 1 or C3D1) RRx-001 treatment as described previously (15). Epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM)-positive CTCs from 10 mL of blood on two consecutive time points cycle 1 day 1 and cycle 3 day 1 (one cycle duration =1 week) were detected by EpCAM-based immunomagnetic capture and flow cytometric analysis where CTCs were defined as viable, EpCAM-positive cells, negative for the pan-hematopoietic marker CD45 and possessing an intact nucleus (15). CTCs were further characterized for protein expression of PD-L1. Blood was drawn into 10-mL CellSave or lavender top (EDTA) tubes and immediately labeled with a study-specific code identifier.

Statistical analysis

Change from baseline in PD-L1 expression on CTCs was summarized via standard descriptive statistics, and graphically depicted as a scatter and longitudinal line plot (change vs. baseline). Change from baseline in PD-L1 expression on CTCs was compared between patients who had clinical benefit defined as stable disease (SD), partial response (PR) or complete response (CR) and patients who had progressive disease (PD) using a Wilcoxon two-sided test. The correlation between the binary clinical outcome (SD/PR/CR vs. PD) and the change in PD-L1 expression on CTCs pre and post RRx-001 was analyzed using a logistic regression adjusting for baseline PD-L1 expression. McFadden pseudo R2 number of 0.40 is considered to be excellent (16,17). Accuracy is defined in the standard way as 1 − (false positive rate + false negative rate).

Results

CTCs provide a snapshot of the characteristics of primary and/or metastatic tumor cells (18). We analyzed a clinical data set comprised of 14 RECIST-evaluable patients with complete biomarker data. Seven out of 14 SCLC patients (50%) were females and the median age (years) at baseline was 65 (range, 49–84). The association between clinical response and the change of PD-L1 expression on CTCs from baseline was investigated by using a logistic regression. The logistic model McFadden goodness of fit score (0 to 100) was 0.477, which is a strong correlation value. The logistic model analyzing the association between decreased PD-L1 expression on CTCs after RRx-001 and response to platinum-based doublet therapy had an approximate 92.8% accuracy in its prediction of clinical benefit (SD/PR/CR). The estimated receiver operating characteristic (ROC) displayed a ROC area under the curve (AUC) of 0.93 (95% confidence interval, 0.78‒0.99), which suggested an excellent measure of performance (Figure 2). These results indicate that the reduction of PD-L1 expression on CTCs after RRx-001 was significantly correlated with response to RRx-001-based cancer therapy.

Figure 2.

Logistic regression model ROC. The correlation between the binary clinical outcome (SD/PR/CR vs. PD) and the change in PD-L1 expression on CTCs was analyzed using a logistic regression adjusting for baseline PD-L1 expression. ROC, receiver operating characteristic; SD, stable disease; PR, partial response; CR, complete response; PD, progressive disease; PD-L1, programmed death-ligand-1; CTC, circulating tumor cell.

Discussion

In the QT study, we have shown that the combination of RRx-001 and a reintroduced platinum doublet was associated with clinical benefit and less hematologic and non-hematologic toxicities than expected upon the re-administration of a platinum doublet (19). The oncoprotein Myc is frequently overexpressed in SCLC and the overexpression of Myc has been shown to correlate with PD-L1 expression in lung cancer (20). Myc was previously thought to be undruggable, however, it has been shown that the mechanism of RRx-001 activity is related to inhibition of Myc (21). PD-L1 expression on tumor cells is a validated predictive biomarker for sensitivity to immune checkpoint blockade (22). Therefore, we hypothesized that PD-L1 on CTCs during RRx-001 treatment may serve as a biomarker to predict response to RRx-001-based cancer therapy (Figure 1).

It has been suggested that RRx-001-mediated down-regulations of Myc, CD47 and Myc-stimulated immunosuppressive signaling pathways may serve as underlying mechanisms by which re-sensitization to the reintroduced chemotherapeutic agents occurred (5). In the current study, reduction of PD-L1 expression on CTCs after RRx-001 was significantly correlated with response to reintroduced platinum-based doublet therapy. PD-L1 on tumor cells mediates immune escape (23). Thus, our study suggests that RRx-001 has potential immunomodulatory properties and monitoring of the dynamic changes of PD-L1 expression on CTCs in SCLC patients treated with RRx-001 may serve as a biomarker to evaluate therapeutic efficiency. In the ongoing phase 3 study of a combination therapy with RRx-001 and platinum doublet in previously treated SCLC (REPLATINUM, NCT03699956), biomarker analyses are planned to correlate clinical response with dynamic co-expression of CD47 and PD-L1 on CTCs.

Our findings should be interpreted with caution in view of the limited samples, an exploratory study and univariate analyses which does not take into account variable confounding factors that may affect PD-L1 expression on CTCs. The results need to be confirmed in larger cohorts.

In conclusion, this is the first evidence suggesting a correlation between reduction of PD-L1 expression on CTCs after RRx-001 and response to reintroduced platinum doublet therapy in previously treated SCLC. Our study suggests that PD-L1 on CTCs during RRx-001 treatment may serve as a biomarker to predict response to RRx-001-based therapy in advanced cancer patients.

Supplementary

The article’s supplementary files as

Acknowledgments

Funding: The clinical trial described in this report was supported by EpicentRx. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI grant number JP18K15928.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was approved by the respective institutional review board at each institution that participated in the clinical trial (registration number NCT02489903) and individual consent for this retrospective analysis was waived. All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013).

Footnotes

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the REMARK reporting checklist. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tlcr-20-359

Data Sharing Statement: Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tlcr-20-359

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tlcr-20-359). BO and TRR are employees of EpicentRx. NA is a consultant to EpicentRx. JBT received funding from the NCI Intramural Program and research funding from EpicentRx to her institution. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Oronsky B, Reid TR, Oronsky A, et al. Brief report: RRx-001 is a c-Myc inhibitor that targets cancer stem cells. Oncotarget 2018;9:23439-42. 10.18632/oncotarget.25211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oronsky B, Reid TR, Larson C, et al. REPLATINUM Phase III randomized study: RRx-001 + platinum doublet versus platinum doublet in third-line small cell lung cancer. Future Oncol 2019;15:3427-33. 10.2217/fon-2019-0317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lian S, Xie R, Ye Y, et al. Dual blockage of both PD-L1 and CD47 enhances immunotherapy against circulating tumor cells. Sci Rep 2019;9:4532. 10.1038/s41598-019-40241-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cabrales P. RRx-001 Acts as a Dual Small Molecule Checkpoint Inhibitor by Downregulating CD47 on Cancer Cells and SIRP-alpha on Monocytes/Macrophages. Transl Oncol 2019;12:626-32. 10.1016/j.tranon.2018.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oronsky B, Paulmurugan R, Foygel K, et al. RRx-001: a systemically non-toxic M2-to-M1 macrophage stimulating and prosensitizing agent in Phase II clinical trials. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2017;26:109-19. 10.1080/13543784.2017.1268600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harris K, Khachaturova I, Azab B, et al. Small cell lung cancer doubling time and its effect on clinical presentation: a concise review. Clin Med Insights Oncol 2012;6:199-203. 10.4137/CMO.S9633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oronsky B, Reid TR, Oronsky A, et al. What's New in SCLC? A Review. Neoplasia 2017;19:842-7. 10.1016/j.neo.2017.07.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Regzedmaa O, Zhang H, Liu H, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for small cell lung cancer: opportunities and challenges. Onco Targets Ther 2019;12:4605-20. 10.2147/OTT.S204577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fouad YA, Aanei C. Revisiting the hallmarks of cancer. Am J Cancer Res 2017;7:1016-36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weiskopf K, Jahchan NS, Schnorr PJ, et al. CD47-blocking immunotherapies stimulate macrophage-mediated destruction of small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Invest 2016;126:2610-20. 10.1172/JCI81603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun NY, Chen YL, Wu WY, et al. Blockade of PD-L1 Enhances Cancer Immunotherapy by Regulating Dendritic Cell Maturation and Macrophage Polarization. Cancers (Basel) 2019;11:1400. 10.3390/cancers11091400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yasuda Y, Ozasa H, Kim YH. PD-L1 Expression in Small Cell Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2018;13:e40-1. 10.1016/j.jtho.2017.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Casey SC, Baylot V, Felsher DW. The MYC oncogene is a global regulator of the immune response. Blood 2018;131:2007-15. 10.1182/blood-2017-11-742577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hodgkinson CL, Morrow CJ, Li Y, et al. Tumorigenicity and genetic profiling of circulating tumor cells in small-cell lung cancer. Nat Med 2014;20:897-903. 10.1038/nm.3600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas A, Rajan A, Berman A, et al. Sunitinib in patients with chemotherapy-refractory thymoma and thymic carcinoma: an open-label phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2015;16:177-86. 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71181-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu B, Shao J, Palta M. Pseudo-R2 in logistic regression model. Statistica Sinica 2006;16:847-60. [Google Scholar]

- 17.McFadden D. Conditional logit analysis of qualitative choice behavior. In: Zarembka P. editor. Frontiers in Econometrics. New York: Academic Press, 1973:105-42. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Allard WJ, Matera J, Miller MC, et al. Tumor cells circulate in the peripheral blood of all major carcinomas but not in healthy subjects or patients with nonmalignant diseases. Clin Cancer Res 2004;10:6897-904. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morgensztern D, Rose M, Waqar SN, et al. RRx-001 followed by platinum plus etoposide in patients with previously treated small-cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer 2019;121:211-7. 10.1038/s41416-019-0504-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim EY, Kim A, Kim SK, et al. MYC expression correlates with PD-L1 expression in non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2017;110:63-7. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2017.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen H, Liu H, Qing G. Targeting oncogenic Myc as a strategy for cancer treatment. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2018;3:5. 10.1038/s41392-018-0008-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tong M, Wang J, He W, et al. Predictive biomarkers for tumor immune checkpoint blockade. Cancer Manag Res 2018;10:4501-7. 10.2147/CMAR.S179680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang X, Wang J, Deng X, et al. Role of the tumor microenvironment in PD-L1/PD-1-mediated tumor immune escape. Mol Cancer 2019;18:10. 10.1186/s12943-018-0928-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The article’s supplementary files as