Abstract

The present studies examined the extent to which (a) communalism, familism, and filial piety would pattern onto a single family/relationship primacy construct; (b) this construct would be closely related to indices of collectivism; and (c) this construct would be related to positive psychosocial functioning and psychological distress. In Study 1, 1,773 students from nine colleges and universities around the United States completed measures of communalism, familism, and filial piety, as well as of individualistic and collectivistic values. Results indicated that communalism, familism, and filial piety clustered onto a single factor. This factor, to which we refer as family/relationship primacy, was closely and positively related to collectivism but only weakly and positively related to individualism and independence. In Study 2, 10,491 students from 30 colleges and universities in 20 U.S. states completed measures of communalism, familism, and filial piety, as well as of positive psychosocial functioning and psychological distress. The family/relationship primacy factor again emerged and was positively associated with both positive psychosocial functioning and psychological distress. Clinical implications and future directions for the study of cultural values are discussed.

Keywords: communalism, familism, filial piety, collectivism, well-being

The number of immigrants and children of immigrants in the United States has reached an all-time high. As of 2003, nearly 35 million foreign-born individuals resided in the country (Larsen, 2004), along with many more U.S.-born individuals who were raised by immigrant parents (Hernandez, 2009). Since 1965, the United States has become increasingly ethnically diverse as a result of newcomers and their descendants from non-European countries—most notably Latin America, Asia, and the Caribbean (Portes & Rumbaut, 2001, 2006).

The influx of newcomers has increased the salience of ethnicity in the United States and has prompted various ethnic communities to pay increased attention to their cultural heritage. As a result, multiculturalism and diversity have become important social initiatives and values in the United States (Huntington, 2004; Stepick, Dutton Stepick, & Vanderkooy, in press). This diversity both enriches and cautions against the use of pan-ethnic categories such as White, Black, Hispanic, and Asian. Accordingly, research on the cultural value orientations of U.S. ethnic groups has also gained momentum in recent years (Rogoff & Chavajay, 1995). For example, African Americans have maintained a separate cultural identity from other ethnic groups (see Boykin, & Allen, 2003). Separate cultural identities have also emerged in Hispanics (Suárez-Orozco & Páez, 2002), Asian Americans (Leong et al., 2006) and other groups. Much of the accompanying scholarship is premised on the notion that the cultures of these groups stem, at least in part, from the countries or regions from which their members originated.

In essence, each of the major non-European descent ethnic groups in the United States has brought and cultivated its own cultural value system. For example, among individuals from the African diaspora—African Americans and Caribbean Blacks, as well as African immigrants—communalism is known to be an important value orientation (e.g., Wallace & Constantine, 2005). Communalism represents an emphasis on social relationships and ties over individual achievement (Jagers & Mock, 1995). Ties to friends and family members, where “family” includes nonblood kin as well as blood relatives, are prioritized as an essential part of daily life (Nobles, Goddard, Cavil, & George, 1987).

Among Hispanics—individuals who (or whose families) originate from Spanish-speaking countries in the Americas—one of the prevailing cultural values is familism (Sabogal, Marin, Otero-Sabogal, Marin, & Perez-Stable, 1987). Familism represents prioritizing the needs of family members over one’s own needs; honoring family members; defining oneself in terms of one’s relationship to one’s family; and remaining respectful and obligated to one’s parents, siblings, and extended family members well into adulthood (Valdés, 2008).

Among Asian Americans, filial piety is one of the most closely held cultural values (Yeh & Bedford, 2003). Filial piety refers to bestowing honor upon one’s family, caring for aging parents, and carrying out parents’ wishes and dreams even after their deaths (Yeh & Bedford, 2004). Both East Asian (Bedford, 2004) and South Asian (Rao, McHale, & Pearson, 2003) parents may instill a sense of filial piety in their children. Children are socialized to experience guilt and shame if they violate these principles—even after reaching adulthood (Bedford, 2004; Bedford & Hwang, 2003).

Clearly, communalism, familism, and filial piety originate from different parts of the world and from separate cultural groups. In this sense, they are specific to the ethnic groups from which they originated. However, they also share a common thread in that (a) they each stress the importance of social ties over individual desires and successes, and (b) they prioritize the needs and the beneficence of the family or other important group (e.g., clan, nation, religious group) over the needs of the individual person. Thus, they may share some transcultural dimensions. These dimensions and characteristics may be consistent with the construct of collectivism—the tendency to value the needs of others (and of the groups to which one belongs) over one’s own personal needs (Bedford & Hwang, 2003; Jagers & Mock, 1995; Schwartz, 2007). However, communalism, familism, and filial piety have seldom been studied together (for an exception, see Unger et al., 2002, who found that familism and filial piety were strongly intercorrelated, and protective against drug and alcohol use, in a multiethnic sample of adolescents). In the multicultural and cross-cultural literatures, there is a fundamental tension between what is considered universal versus culture-specific. The present study empirically examines this tension with regard to these three culture-specific value systems and integrates bottom-up (theory building and cross-cultural relevance) and top-down (practical applicability) approaches, as recommended by Betancourt and Lopez (1993). That is, we use the first study to extract an underlying latent construct from among communalism, familism, and filial piety and to examine the consistency of this construct across ethnicity; and we use the second study to examine the associations of this construct with psychosocial functioning.

Collectivism is thought to apply to Latin American, Asian, Caribbean, African, and Middle Eastern cultural contexts (Triandis, 1995). Not coincidentally, these are some of the same regions where the culturally based values of communalism, familism, and filial piety originated. It would follow, then, that these three value orientations might be framed as elements or manifestations of collectivism—although more research is needed to substantiate this proposition.

Extant research has utilized primarily African American and Caribbean Black samples in studies of communalism (e.g., Mattis et al., 2004; Wallace & Constantine, 2005), primarily Hispanic samples in studies of familism (e.g., Bettendorf & Fisher, 2009; Smokowski, Rose, & Bacallao, 2008), and primarily Asian and Asian American samples in studies of filial piety (e.g., Chen, Bond, & Tang, 2007; Yeh & Bedford, 2003, 2004). Nevertheless, these constructs—especially familism and filial piety—have been shown to share commonalties, both conceptually (Kao, McHugh, & Travis, 2007; Kao & Travis, 2005) and empirically (Unger et al., 2002), particularly in terms of deference and obedience to family members and prioritizing the group over the individual. To the extent that this overlap is substantial, it is possible that a larger underlying construct may be extracted from among communalism, familism, and filial piety (Schwartz, 2007), and this construct may be salient for individuals from all three groups to which these values are thought to apply (individuals of African, Latin American, and Asian descent). Study 1 was designed to examine this proposition by examining the responses of participants from multiple ethnic groups on measures designed to assess these three value orientations.

The applicability of such a construct to European Americans also is worthy of investigation. European Americans have often served as a comparison group in studies of communalism specifically (Boykin et al., 2005; Tyler et al., 2008) and in cultural research in general (e.g., Brown et al., 2008; Eap et al., 2008; Park & Kim, 2008). However, especially in light of the rapid growth in ethnic minority populations in the United States, the assumption that “White culture” and “American culture” are synonymous (DeVos & Banaji, 2005; Rodriguez, Schwartz, & Whitbourne, 2010) has been called into question (e.g., Schwartz, Zamboanga, & Weisskirch, 2008), and individuals of European descent have begun to be recognized as a cultural and ethnic group characterized by considerable diversity (Vandello & Cohen, 1999). As a result, we argue here that Whites should be treated as a cultural group, rather than as a comparison group, in studies of cultural constructs.

Although White American culture is assumed to be highly individualistic (i.e., prioritizing the individual person over group allegiances and obligations; Hofstede, 2001), some studies have found that Whites do not differ from other ethnic groups in endorsement of familism (Schwartz, 2007) and other collectivistic values (Schwartz, Zamboanga, Rodriguez, & Wang, 2007). Moreover, the structural associations between cultural constructs (e.g., collectivism, ethnic identity) and other variables of interest (e.g., self-esteem, depressive symptoms, behavior problems, health risk behaviors) have often been found to be consistent across ethnic groups, including Whites (Kiang, Yip, & Fuligni, 2008; Marsiglia, Kulis, & Hecht, 2001; Rivas-Drake, Hughes, & Way, 2009; Yasui, Dorham, & Dishion, 2004). As a result, it is important to include European Americans as a group of substantive interest in cross-ethnic comparisons of the internal structure and external functions of cultural constructs.

Protective Functions of Collectivistic Values

In individuals from various ethnic groups, adherence to collectivist-type value orientations have been shown to promote self-esteem (Ghazarian, Supple, & Plunkett, 2008) and to help protect against anxiety and depression (Zhang, Norvilitis, & Ingersoll, 2007). These associations likely operate by creating support systems, facilitating greater allegiance to family and other social ties, and encouraging individuals to take responsibility for the effects of their behavior and its consequences on other people. Moreover, although purportedly collectivistic value systems such as communalism, familism, and filial piety have been examined separately as correlates of well-being (including self-esteem and life satisfaction), the literatures on these cultural values have yet to be integrated, and these three cultural value systems have not been examined together in a single study. As a result, relatively little is known about the associations of these three value systems—or a higher-order construct that integrates them and maps their relevance to psychosocial and health outcomes.

To the extent that communalism, familism, and filial piety cluster onto a single latent construct, which we will refer to as family/relationship primacy, and to the extent to which it is accurate to frame such a construct as a dimension of collectivism, the family/relationship primacy construct should be associated with measures of collectivism and similar constructs. In the United States, collectivism (and the family/relationship primacy construct) may also be linked with feelings of identification with one’s (or one’s family’s) heritage culture—which is likely more collectivistic than mainstream American culture (e.g., Hofstede, 2001). Based on prior research on collectivism (e.g., Le & Kato, 2005; Zhang et al., 2007), we expect that the family/relationship primacy construct should also be positively associated with indices of well-being and negatively related to indices of distress. Thus, using a top-down approach, the purpose of the second study reported in this article was to examine the associations of communalism, familism, and filial piety with well-being and distress— also in an ethnically diverse American sample.

Transcultural value orientations.

Before going further, we should briefly discuss the cultural values that have been studied across ethnic groups—which include individualism, collectivism and self-construal. The constructs of “individualism” and “collectivism” include refer to attitudes toward the self in relation to others (Singelis, Triandis, Bhawuk, & Gelfand, 1995; Triandis, 1995). As specified by Triandis and Gelfand (1998), “horizontal individualism and collectivism” refer to thinking of oneself as separate from, or connected to, others at one’s own social stratum (such as friends and coworkers). “Vertical individualism and collectivism” refer to thinking of oneself as separate from, or connected to, individuals who are above the person in a social hierarchy (such as parents, teachers, and employers). Although individualism and collectivism can be considered both at the between-country and at the between-individual level (Matsumoto, 2003), we consider here only individualism-collectivism at the individual level. Self-construal, which includes “independence and interdependence,” refers to relating to others as separate entities or as part of a whole, respectively (Markus & Kitayama, 1991). Although individualism and collectivism and self-construal represent similar constructs, there are some subtle differences between them. Individualism-collectivism refers to the priority or position of the self or group, whereas self-construal refers to the definition or orientation of the self as internal attributes or in relation to others. Nonetheless, these constructs can be grouped under the superordinate heading of general cultural values—where collectivistic cultural orientations include horizontal and vertical collectivism as well as interdependence, and where individualistic cultural orientations include horizontal and vertical individualism as well as independence.

Research conducted in the United States (Schwartz & Zamboanga, 2008; Schwartz et al., 2007) suggests that individual-level indices of heritage-culture retention—such as engaging in heritage-culture practices, holding collectivistic value orientations, and identifying with one’s heritage culture—tend to cluster together onto a single latent factor. Similarly, individual-level indices of American-culture acquisition—such as engaging in American cultural practices, holding individualistic value orientations, and endorsing an American identity—also tended to cluster together onto a single latent factor. These heritage and American cultural orientations have been found to emerge similarly across ethnic groups (including Whites) and to be somewhat positively correlated with one another. These findings suggest that one can identify with multiple cultural backgrounds (see also Kiang et al., 2008). Given that some White Americans—such as those of Irish, Italian, Greek, and Polish descent—tend to identify at least somewhat with their ethnic heritage (e.g., Ponterotto et al., 2001; Rodriguez, Schwartz, & Whitbourne, 2010), this phenomenon may be applicable to Whites as well as to members of other ethnic groups (e.g., Rodriguez et al., 2010; Schildkraut, 2007).

The Present Studies

We report the results of two studies in this article, both of which use large, multisite, multiethnic college student samples. The purpose of Study 1 was to adopt a bottom-up approach (Betancourt & Lopez, 1993), where we build theory by examining the extent to which communalism, familism, and filial piety would cluster onto a single latent construct, as well as to map the relationships of this latent construct to indices of collectivism, individualism, and other dimensions of cultural identity. Specifically, we hypothesized that communalism, familism, and filial piety would cluster together as a family/relationship primacy construct and would be positively correlated with indices of collectivism and other indices of heritage-culture retention (ethnic identity and heritage-cultural practices). Given that heritage and American orientations represent separate cultural dimensions (Schwartz, Unger, Zamboanga, & Szapocznik, 2010), we hypothesized that the family/relationship primacy construct would be largely uncorrelated with indices of individualism, American identity, and American cultural practices. We also examined mean differences in communalism, familism, filial piety, and the family/relationship primacy construct across gender and ethnicity, and we hypothesized that minority group members would score higher than Whites on each of these value orientations. The purpose of Study 2 was to adopt a top-down approach (i.e., orientated toward practical applicability; Betancourt & Lopez, 1993), where we examine the associations of the family/ relationship primacy construct with psychosocial well-being and psychological distress. For Study 2, we hypothesized that the family/relationship primacy construct would be positively associated with indices of well-being and negatively associated with indices of distress.

Study 1 Method

Participants

The sample for Study 1 consisted of 1,773 undergraduate students (M age = 20.3 years, SD = 3.37 years, 76% women) from 9 colleges and universities around the United States. In terms of ethnicity, 53% of the sample (n = 925) identified as White, 9% (n = 163) as Black, 25% (n = 439) as Hispanic, 7% (n = 121) as East/South Asian, 1% (n = 14) as Middle Eastern, and 5% (n =96) as Other (see Table 1). Forty percent of Blacks were African American (defined as the participant and both parents born in the United States), 48% were Caribbean, and 12% were African. Among Hispanics, the most common countries of origin were Cuba (33%), Mexico (8%), and Colombia (8%), with the remaining participants from a number of Caribbean, Central American, and South American countries. Among Asians, the most common countries of origin were China (17%), Vietnam (17%), India (12%), and the Philippines (12%), with the remaining participants from a number of East and South Asian countries.

Table 1.

Participants’ and Parents’ Nativity by Ethnic Group

| White | Black | Hispanic | East Asian | South Asian | Middle Eastern | χ2(5) | φ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study 1 | ||||||||

| Participants (% U.S. born) | 97.1% | 79.2% | 65.2% | 62.5%a | N/Ab | 64.3% | 276.98*** | .41 |

| Mothers (% U.S. born) | 92.9% | 44.0% | 16.6% | 4.2%a | N/Ab | 14.3% | 922.62*** | .76 |

| Fathers (% U.S. born) | 92.4% | 42.3% | 13.2% | 6.7%a | N/Ab | 7.1% | 952.61*** | .77 |

| Study 2 | ||||||||

| Participants (% U.S. born) | 96.2% | 84.8% | 76.7% | 65.6% | 58.3% | 73.1% | 1323.21*** | .36 |

| Mothers (% U.S. born) | 92.6% | 62.1% | 32.8% | 8.6% | 4.5% | 20.3% | 4982.99*** | .71 |

| Fathers (% U.S. born) | 93.2% | 62.3% | 30.2% | 11.2% | 5.1% | 12.2% | 5102.23*** | .72 |

The chi-square statistic and phi effect size refer to the comparison of percentages across ethnic groups.

For Study 1, East Asians and South Asians were combined into a single Asian group.

p < .001.

In terms of data collection sites, two were located in the Northeast, two in the Southeast, one in the Midwest, one in the Southwest, and three in the West. Three of the sites were major public universities, four were smaller/commuter state universities, and two were private colleges. Data for Study 1 were collected between September and December 2007.

Procedures

At each site, participants were directed to the study website by their course instructors (in cases where specific courses offered credit for participation), using printed or emailed announcements (in cases where participants took part to satisfy a general research requirement), or entered into prize drawings (in cases where no other form of credit was available). Prior to taking part in the study, each participant was asked to read an informed consent form and to check a box indicating that she or he was willing to participate. Participants then completed the assessment battery as a confidential online survey. Students were asked to provide their email addresses and student numbers for crediting purposes, but this information was not linked with participants’ responses. Students also provided the name of the college or university that they attended. This information was used only to control for multilevel nesting and was not used to identify specific participants or schools. Completion time for the entire survey ranged from 60 to 90 minutes. Respondents received credit toward their course grades in exchange for their participation. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at each site.

Measures

Family/relationship primacy.

We used measures of communalism, familism, and filial piety as our indicators for this latent construct. For all three of these measures, a 5-point Likert scale was used, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). We report alpha coefficients from the present study, across ethnicity, to affirm that our measures were adequately internally consistent across ethnic groups. To assess communalism, we used the Communalism Scale (Boykin, Jagers, Ellison, & Albury, 1997), which consists of 31 items (in Study 1, α’s ranged from .86 for Hispanics to .90 for Blacks) tapping into the extent to which the person values family and social connectedness. A sample item from this scale is “There are very few things I would not share with family members.” To assess familism, we used the Attitudinal Familism Scale (Lugo Steidel & Contreras, 2003; α’s ranged from .83 for Hispanics to .89 for Blacks), which consists of 18 items assessing the importance placed on family bonds and on obligations to family members. A sample item from this scale is “A person should rely on his or her family if the need arises.” To assess filial piety, we used the Filial Piety Scale (α’s ranged from .87 for Hispanics to .90 for Whites) developed by Unger et al. (2004). This scale was based on a Chinese-language filial piety measure (Ho, 1994) and is one of the only filial piety measures available in English. The Filial Piety Scale consists of 13 items assessing the extent to which the respondent uses her/his parents as a referent and benchmark for her or his own behavior. A sample item from this scale is “The worst thing a person can do is disrespect his or her parents.”

Comparison measures of cultural identity.

Following Chirkov (2009) and Schwartz et al. (2010), we included comparison measures of cultural identity in three domains—practices, values, and identifications. These three domains are important to include separately because, although they overlap somewhat, they represent three distinct domains of cultural identity—behavioral, cognitive, and affective (Castillo, Conoley, & Brossart, 2004).

Cultural practices were assessed using the Stephenson (2000) Multigroup Acculturation Scale. This scale targets the extent to which one engages in customs (e.g., language, holiday celebrations, religious observations) from one’s heritage culture and from American culture. Following current practices in cultural psychology (e.g., Phinney, 2003), heritage (17 items, α’s ranged from .80 for Whites to .85 for Asians) and American (15 items, α’s ranged from .89 for Hispanics to .95 for Whites) cultural practices were assessed separately. Sample items include “I think in English” and “I listen to music from my ethnic group.” A 5-point Likert scale was used, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Cultural values were assessed in terms of individualism-collectivism and self-construal (independence-interdependence). Horizontal and vertical individualism and collectivism were assessed using corresponding 4-item scales developed by Triandis and Gelfand (1998). Internal consistency coefficients for the present sample were: horizontal individualism (α’s ranged from .71 for Hispanics to .74 for Whites); vertical individualism (α’s ranged from .76 for Hispanics to .79 for Blacks); horizontal collectivism (α’s ranged from .62 for Asians to .76 for Blacks); and vertical collectivism (α’s ranged from .70 for Hispanics to .77 for Blacks). Sample items include “I’d rather depend on myself than on others” (horizontal individualism), “Winning is everything” (vertical individualism), “I feel good when I collaborate with others” (horizontal collectivism), and “It is my duty to take care of my family, even when I have to sacrifice what I want” (vertical collectivism). Five-point Likert scales were used, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Self-construal was measured using the 24-item Self-Construal Scale (Singelis, 1994). Twelve items measure independence (α’s ranged from .68 for Whites to .70 for Asians) and 12 assess interdependence (α’s ranged from .73 for Hispanics to .80 for Blacks). Sample items include “I prefer to be direct and forthright in dealing with people I have just met” (independence) and “My happiness depends on the happiness of those around me” (interdependence). The same 5-point Likert scale was used for this measure.

Cultural identifications were measured in terms of both heritage and American identifications. Heritage-culture identifications were assessed using the Multi-Group Ethnic Identity Measure (MEIM; Roberts et al., 1999). The MEIM consists of 12 items (α’s ranged from .90 for Blacks to .92 for Asians) that assess the extent to which one (a) has considered the subjective meaning of one’s ethnicity and (b) feels positively about one’s ethnic group. Sample items include “I think a lot about how my life will be affected by my ethnic group membership” and “I am happy that I am a member of the ethnic Group 1 belong to.” A 5-point Likert scale was used, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Because few validated measures of American identity exist in the literature, we adapted the MEIM so that “the U.S.” was inserted into each item in place of “my ethnic group” or “the ethnic group I belong to.” The scores on this measure were highly internally consistent (α’s ranged from .88 for Whites to .90 for Asians). As an index of construct validity, American identity scores were moderately and significantly correlated (r = .56, p < .001) with scores on American cultural practices.

Study 1 Results

Plan of Analysis

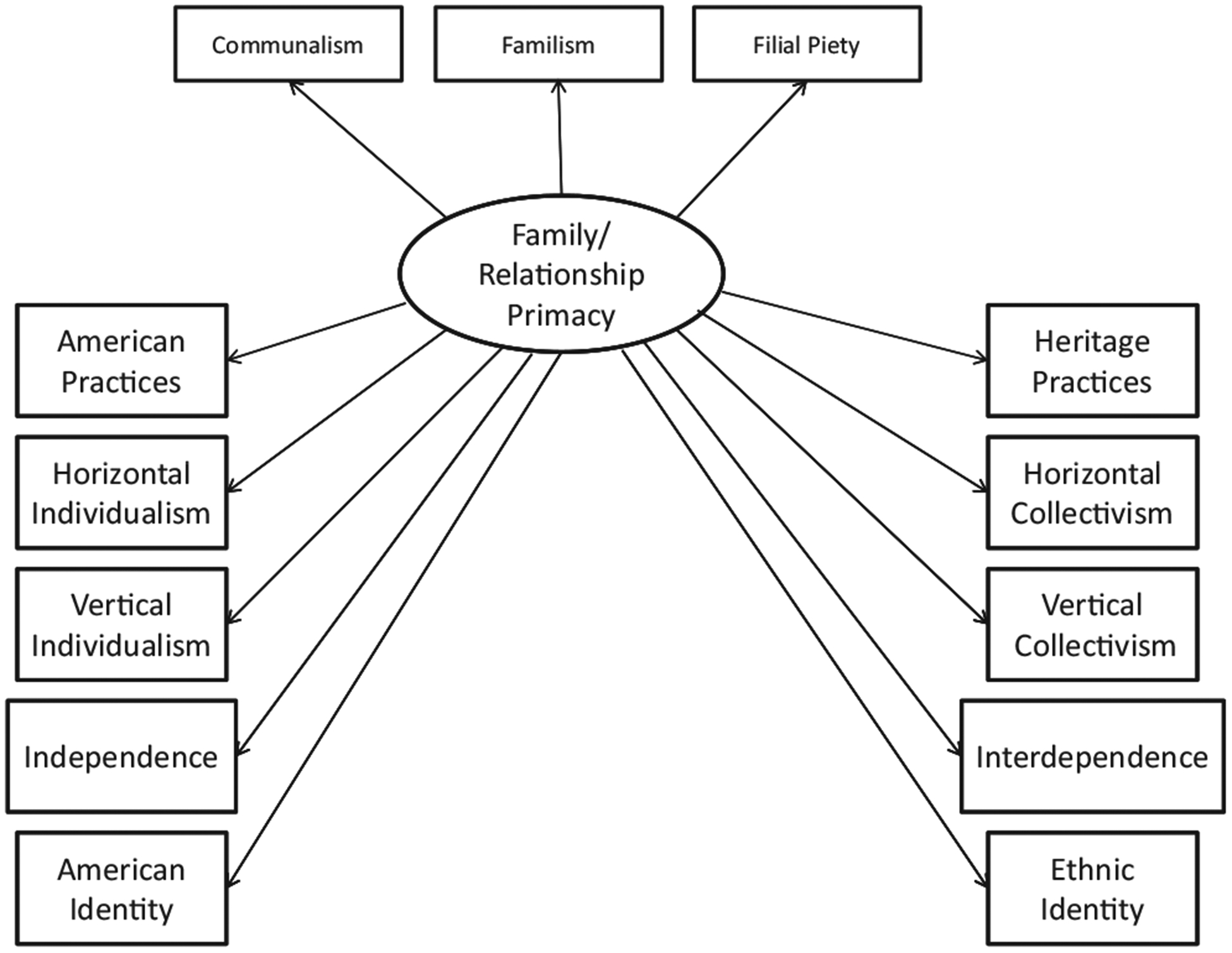

As stated above, the goals of Study 1 were to: (a) ascertain the extent to which communalism, familism, and filial piety would cluster together onto a single latent factor and (b) examine the associations of this latent factor with other indicators of cultural identity. Our analytic plan consisted of four steps. First, we examined the bivariate correlations among communalism, familism, and filial piety to determine whether a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) model could be estimated using these constructs. The second step was to estimate a CFA model in which these three cultural values were specified as indicators of a single latent variable. Because a CFA model with only three indicators is saturated and does not produce fit indices, we used a parceling approach (e.g., Little, Cunningham, Shahar, & Widaman, 2002), in which two indicators were used for each cultural subscale (for a total of six indicators). Third, we estimated the equivalence of the fit and parameter estimates of this CFA solution across gender and across ethnic groups. Fourth, we estimated a model in which the latent family/relationship primacy factor was allowed to correlate with indices of cultural practices, values, and identifications (see Figure 1). Finally, using multigroup structural equation modeling, we examined the consistency of these correlations across gender and across ethnicity. In all analyses, nesting of participants within sites was controlled by including dummy variables for all but one of the sites, with the site providing the largest number of participants used as the reference group. This approach is the preferred solution when there are not enough nesting units to estimate a multilevel model (Bengt Muthén, Mplus workshop, August 20, 2007).

Figure 1.

Structural model for Study 1.

Bivariate correlations and CFA.

The correlations among communalism, familism, and filial piety ranged from .63 to .76 (all ps < .001). Given the magnitude of these correlations, we proceeded to estimate a CFA model with these cultural values. We created parcels for each of the cultural values by dividing each scale into “first” and “second” halves, summing the items in the first half of each scale to create the first parcel, and summing the items in the second half of each scale to create the second parcel. The six parcels were then modeled as indicators of a single latent variable. The error terms for each pair of parcels were allowed to correlate. The error correlation between the two familism parcels was not statistically significant and was dropped from the model.

Model fit was examined using three primary indices (Kline, 2006)—the comparative fit index (CFI), which compares the specified model against a null model with no paths or latent variables; the non-normed fit index (NNFI, also known as the Tucker-Lewis Index), which is similar to the CFI but is adjusted to penalize models with excessive parameters; and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), which indicates the extent to which the covariance matrix implied by the model differs from the covariance matrix observed in the data. We also report the 90% confidence interval for the RMSEA index. The chi-square index is reported, but not used in interpretation, because it tests the null hypothesis of perfect fit to the data—which is often untenable in large samples and/or complex models (Davey & Savla, 2010; Kline, 2006). Although a number of cutoffs for “good” model fit have been proposed, we follow the guidelines established by Kline (2006): CFI ≥ .95, NNFI ≥ .90, and RMSEA ≤ .08.

The resulting model fit the data well, χ2(7) = 49.40, p < .001; CFI = .99; NNFI = .98; RMSEA = .060 (90% CI = .045 to .076). The standardized factor loadings were .63 and .76 for communalism, .76 and .84 for familism, and .82 and .82 for filial piety. We then conducted multigroup metric invariance tests (Vandenberg & Lance, 2000) to ensure that this model fit equivalently across gender and across ethnicity. For comparisons across ethnicity, we included the four largest ethnic groups in the sample—Whites, Blacks (including both African Americans and Black immigrants), Hispanics, and Asians (including both East and South Asians); Middle Eastern and “Other” participants were not included because of small sample sizes. We compared the fit of an unconstrained model, where the factor loadings were free to vary across gender or across ethnic groups, to a fully constrained model where each factor loading was constrained equal across gender or across ethnic groups. A nonsignificant difference in fit between the constrained and unconstrained models would indicate that the factor loadings are equivalent across gender or ethnicity.

Differences in model fit between the unconstrained and constrained models were examined using three standard invariance-testing indices: the difference in chi-square values (Δχ2), the difference in CFI values (ΔCFI), and the difference in NNFI values (ΔNNFI). The null hypothesis of invariance would be statistically rejected if at least two of the following three criteria are met: Δχ2 significant at p < .05 (Byrne, 2001); ΔCFI ≥ .01 (Cheung & Rensvold, 2002); and ΔNNFI ≥ .02 (Vandenberg & Lance, 2000). Results indicated that the null hypothesis of invariance across gender, Δχ2(6) = 2.40, p = .88; ΔCFI < .001; ΔNNFI < .001, and across ethnicity, Δχ2(9) = 9.59, p = .38; ΔCFI < .001; ΔNNFI < .001, could be retained.

Next, given that the latent family/relationship primacy construct was found to possess adequate factorial validity, we estimated descriptive statistics on communalism, familism, filial piety, and the latent family/relationship primacy factor (see Table 2). These statistics were computed for each of the four largest ethnic groups (Whites, Blacks, Hispanics, and Asians) in the sample. Because Whites scored lowest on communalism, familism, and filial piety, for the latent construct the mean for Whites was set to zero, and the means for each the other groups therefore represent the mean difference between Whites and the ethnic group in question (Hancock, Lawrence, & Nevitt, 2000). Blacks reported the highest scores on all three indices, and on the latent variable.

Table 2.

Communalism, Familism, and Filial Piety by Ethnic Group

| Variable | Whites M (SD) | Blacks M (SD), Cohen’s da,b | Hispanics M (SD), Cohen’s da,b | Asians M (SD), Cohen’s da,b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Communalism | 106.17a (14.53) | 109.86b (15.15), .25 | 106.78a,b (13.96), .04 | 110.27b (14.83), .28 |

| Familism | 63.89a (9.80) | 68.84b (10.09), .50 | 67.62b (8.74), .39 | 68.19b(9.82), .44 |

| Filial piety | 40.68a (8.97) | 45.17b (6.77), .52 | 43.14c (8.43), .28 | 43.52b,c(8.08), .32 |

| Latent constructc | 0.00a (11.10) | 6.20b (10.42), .56 | 3.68b (10.26), .34 | 3.85b(9.72), .35 |

Note. Within each row, means with the same subscript are not significantly different at p < .05.

Indicates the effect size (Cohen’s d) for comparing the mean for the group in question to the mean for Whites.

The Cohen’s d value for the comparison between any two ethnic groups can be computed by subtracting the d value for one group from the d value from the other group, and taking the absolute value of this difference.

Refers to the latent variable comprised of communalism, familism, and filial piety. Because Whites scored lowest on communalism, familism, and filial piety, the latent mean is set at zero for Whites.

We then estimated a bivariate correlations model where standardized covariances (correlations) were estimated between the family/relationship primacy factor and the indices of cultural practices, values, and identifications. We first freely estimated all correlations, and we then trimmed nonsignificant paths from the model. As shown in Table 3, in every case, the correlation for heritage orientation was higher than the corresponding correlation for American orientation. We therefore sought to test our hypothesis that the correlations between the family/relationship primacy construct and collectivist/heritage orientations were significantly stronger than the correlations between the family/relationship primacy construct and individualistic/American orientations. To test this possibility, we compared two models: (a) a model in which the correlations between the family/relationship primacy factor and each pair of matching heritage/American orientation indicators (heritage and American cultural practices, vertical individualism and vertical collectivism, horizontal individualism and horizontal collectivism, independence and interdependence, ethnic identity and American identity) were free to vary; and (b) a model in which each pair of “matching” correlations were constrained equal. Invariance tests indicated a significant difference in fit between the constrained and unconstrained models, Δχ2(5) = 194.20, p < .001; ΔCFI = .029; ΔNNFI = .053. This comparison allowed us to conclude that the correlations of the family/relationship primacy with heritage/collectivist orientations were significantly stronger than the corresponding correlations with American/individualist orientations.

Table 3.

Correlations of Family/Relationship Primacy With Indices of Cultural Identity

| Construct | Collectivist/heritage | Individualistic/American |

|---|---|---|

| Cultural practices | .15*** | .11*** |

| Self-construal | .53*** | .32*** |

| Horizontal individualism/collectivism | .44*** | .14*** |

| Vertical individualism/collectivism | .72*** | .17*** |

| Cultural identifications | .45*** | .29*** |

p < .001.

We then sought to examine the extent to which the full correlation matrix would be consistent across gender and across ethnicity. We again conducted multigroup invariance tests between constrained and unconstrained models. Results indicated that the correlations between family/relationship primacy and other dimensions of cultural identity were consistent across gender, Δχ2(10) =5.02, p = .89; ΔCFI < .001; ΔNNFI < .001, and across Whites, Blacks, Hispanics, and Asians, Δχ2(36) = 64.16, p < .003; ΔCFI = .003; ΔNNFI < .001. This suggests that family/ relationship primacy is more closely related to heritage orientation than to American orientation for all four major ethnic groups.

Study 1 Discussion

The results of Study 1 indicate that the three family/relationship primacy constructs under study here—communalism, familism, and filial piety—are closely related to one another and characterized by similar factor structures across ethnic groups. The present findings suggest that these value systems share a common, collectivist-based underpinning. This underpinning was strongly related to vertical collectivism, which refers to deference to and respect for one’s family members (cf. Triandis, 1995). In particular, familism and filial piety are similar to vertical collectivism in that parents must be obeyed without question, and in that individuals must prioritize family members’ wishes and needs over their own.

Family/relationship primacy was also related to interdependence and to identification with the heritage culture. It therefore appears that the extent to which one identifies with one’s cultural or ethnic heritage may be associated with higher levels of collectivism and perceived familial obligations. This association appears to apply to European Americans as well as to members of other ethnic groups. Rodriguez et al. (2010) found that White American participants often cited their ethnic heritage (e.g., Irish, Italian, Polish) with regard to a sense of group solidarity that they saw as missing from mainstream American culture.

It is interesting that endorsing communalism, familism, and filial piety does not appear to contraindicate also endorsing American cultural values and a sense of American identity (cf. Schwartz et al., 2010). The correlations between the family/relationship primacy factor and indices of American cultural practices, values, and identifications were generally small—with only one above .20. The finding that these indices of heritage and American cultural endorsement were largely uncorrelated supports a bidimensional model of cultural identity (Schwartz et al., 2010). As Phinney (2003) and Oyserman, Coon, and Kemmelmeier (2002) have reported, individualism and collectivism—and by extension, American and heritage orientations—are not opposing and may be compatible with one another. One can engage both in practices typical of American culture and in practices drawn from one’s heritage culture (Phinney, 2003), can endorse both individualistic and collectivistic value orientations (Coon & Kemmelmeier, 2002), and can identify with both American culture and one’s (or one’s family’s) heritage culture (Kiang et al., 2008).

Having established the factorial and construct validity of communalism, familism, and filial piety vis-à-vis one another and other cultural identity indices, we proceeded to Study 2, which was designed to examine the extent to which these family/relationship primacy constructs (a) would be associated with adaptive psychosocial functioning and (b) would protect against psychological distress, antisocial activities, and health risk behaviors.

Study 2 Method

Participants and Procedures

The sample for Study 2 consisted of 10,573 undergraduate students (M age = 20.3 years, SD = 3.37 years, 97% between 18 and 28; 73% were women) from 30 colleges and universities around the United States. In terms of ethnicity, 58% (n = 6,141) of the sample identified as White, 8% (n = 896) as Black, 14% (n = 1,527) as Hispanic, 13% (n = 1,383) as East/South Asian, and 1% (n = 136) as Middle Eastern. Eight participants identified as Other, and 442 participants did not indicate their ethnicity. The majority of participants indicated that both they (88%) and their mothers (68%) and fathers (69%) had been born in the United States—although these percentages differed significantly across ethnicity (see Table 1). Data on the Study 2 sample were collected between September 2008 and October 2009. Because we sampled largely from introductory courses, it is highly unlikely that any of the same individuals participated in both Study 1 (data collected in 2007) and Study 2 (data collected in 2008–2009).

Fifty-eight percent of Blacks self-identified as African American, 22% as Caribbean, and 20% as African. Among Hispanics, the most common countries of origin were Mexico (17%), Cuba (16%), Colombia (6%), and the Dominican Republic (3%), with the remaining participants from a number of Caribbean, Central American, and South American countries. Among Asians, the most common countries of origin were Vietnam (15%), China (12%), Korea (11%), the Philippines (10%), and India (9%), with the remaining participants from a number of East and South Asian countries.

In terms of sites, six were located in the Northeast, seven in the Southeast, six in the Midwest, three in the Southwest, and eight in the West. Fifteen of the sites were major public universities, eight were smaller/commuter state universities, four were major private universities, and three were private colleges. At each site, the same procedures from Study 1 were used.

Measures

Family/relationship primacy.

The same measures from Study 1 were used to index communalism, familism, and filial piety. In Study 2, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for communalism ranged from .90 for Whites to .93 for Asians; Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for familism ranged from .88 for Blacks to .91 for Asians; and Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for filial piety ranged from .88 for Blacks to .91 for Asians.

Positive psychological functioning.

We assessed positive psychosocial functioning in terms of five forms of overall well-being (cf. Waterman, 2008): self-esteem (Swann, Chang-Schneider, & Larsen-McClarty, 2007), meaning in life (Steger & Frazier, 2005), life satisfaction (Diener, Suh, Lucas, & Smith, 1999), psychological well-being (ability to successfully handle the tasks of life; Ruini et al., 2003; Ryff & Keyes, 1995), and eudaimonic well-being (feelings of life purpose and of having “found oneself”; Ryan & Deci, 2001; Ryff & Singer, 2006). Although these indicators are somewhat independent of one another (Keyes, Shmotkin, & Ryff, 2002; Waterman et al., 2010), there is also evidence that they share a common referent and nomological net—namely happiness and satisfaction (Waterman, Schwartz, & Conti, 2008).

Self-esteem was assessed using the Rosenberg (1969) Self-Esteem Scale, which is the most commonly used measure of self-esteem for adolescents and adults. The measure consists of five positively worded items (e.g., “I feel that I have a number of good qualities”) and five negatively worded items (e.g., “At times, I think I am no good at all”). A five-point response scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), was used for each item. Negatively worded items were reverse-coded and summed with the positively worded items to create a total score (α’s for Study 2 ranged from .86 for Asians to .89 for Hispanics).

Meaning in life was measured using the 5-item Presence subscale from the Meaning in Life Scale (Steger, Frazier, Oishi, & Kaler, 2006). Sample items include “I understand my life’s meaning.” In Study 2, Cronbach’s alpha values ranged from .85 for Asians to .88 for Whites.

Life satisfaction was assessed using the five-item Satisfaction with Life Scale (Pavot & Diener, 1993). This measure has been extensively validated around the world (Kuppens, Realo, & Diener, 2008). Sample items include “In most ways, my life is close to my ideal.” A five-point response scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), was used for each item. In Study 2, Cronbach’s alpha values ranged from .85 for Blacks to .89 for Asians.

Psychological well-being was measured using the shortened (18-item) version of the Scales for Psychological Well-Being (Ryff & Keyes, 1995). This instrument assesses the dimensions of psychological well-being identified by Ryff (1989): autonomy, environmental mastery, personal growth, positive relations with others, purpose in life, and self-acceptance. a 6-point likert-type scale is used, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). Ten items are worded in a positive direction, and eight are worded in a negative direction. A composite score for psychological well-being is created by recoding the negatively worded items and summing across the 18 items. Items include “I am quite good at managing the many responsibilities of my daily life.” In Study 2, Cronbach’s alpha for the composite score ranged from .81 for Blacks to .86 for Asians.

Eudaimonic well-being was assessed using the Questionnaire on Eudaimonic Well-Being (Waterman et al., 2010). This 21-item measure taps into the extent to which respondents enjoy challenging activities, expend a great deal of effort in activities that they enjoy, and spend time pursuing and actualizing their personal potentials. Each item is responded to using a 5-point Likert-type scale, with possible choices ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Fourteen of the items are written in an affirmative direction, and 7 items are written in a negative direction and are reverse scored. Sample items include “I feel I have discovered who I really am” and “I feel best when I’m doing something worth investing a great deal of effort in.” In the Study 2 sample, Cronbach’s alpha values ranged from .85 for Blacks to .88 for Asians.

Psychological distress.

We measured distress in terms of symptoms of depression and general anxiety. For both measures, each item was answered using a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977), which measures feelings of dysthymia, listlessness, and difficulty eating and sleeping during the week prior to assessment. A sample item is “I have felt down and unhappy this week.” In the Study 2 sample, Cronbach’s alpha values ranged from .86 for Blacks to .88 for Asians. General anxiety was assessed using an 18-item adapted version of the Beck Anxiety Inventory (Beck, Epstein, Brown, & Steer, 1988). Seven of the items from the original Beck Anxiety Inventory were retained, and 11 items not on the original measure (e.g., difficulty sleeping, excessive worrying, being in a bad mood, having “butterflies” in one’s stomach) were added to cover a broader range of dimensions of anxiety in normally functioning individuals. Items referring to extreme or clinically elevated symptoms of anxiety (e.g., wobbliness in legs, fainting, feelings of choking, fear of dying) were not included in the adapted version of the measure. Both the original measure and our adapted version target feelings of tension, hypervigilance, and difficulty relaxing or calming down during the week prior to assessment. A sample item is “This week, I have found myself worrying about the worst possible things that can happen to me.” In the Study 2 sample, Cronbach’s alpha values were .95 for all ethnic groups.

Study 2 Results

Plan of Analysis

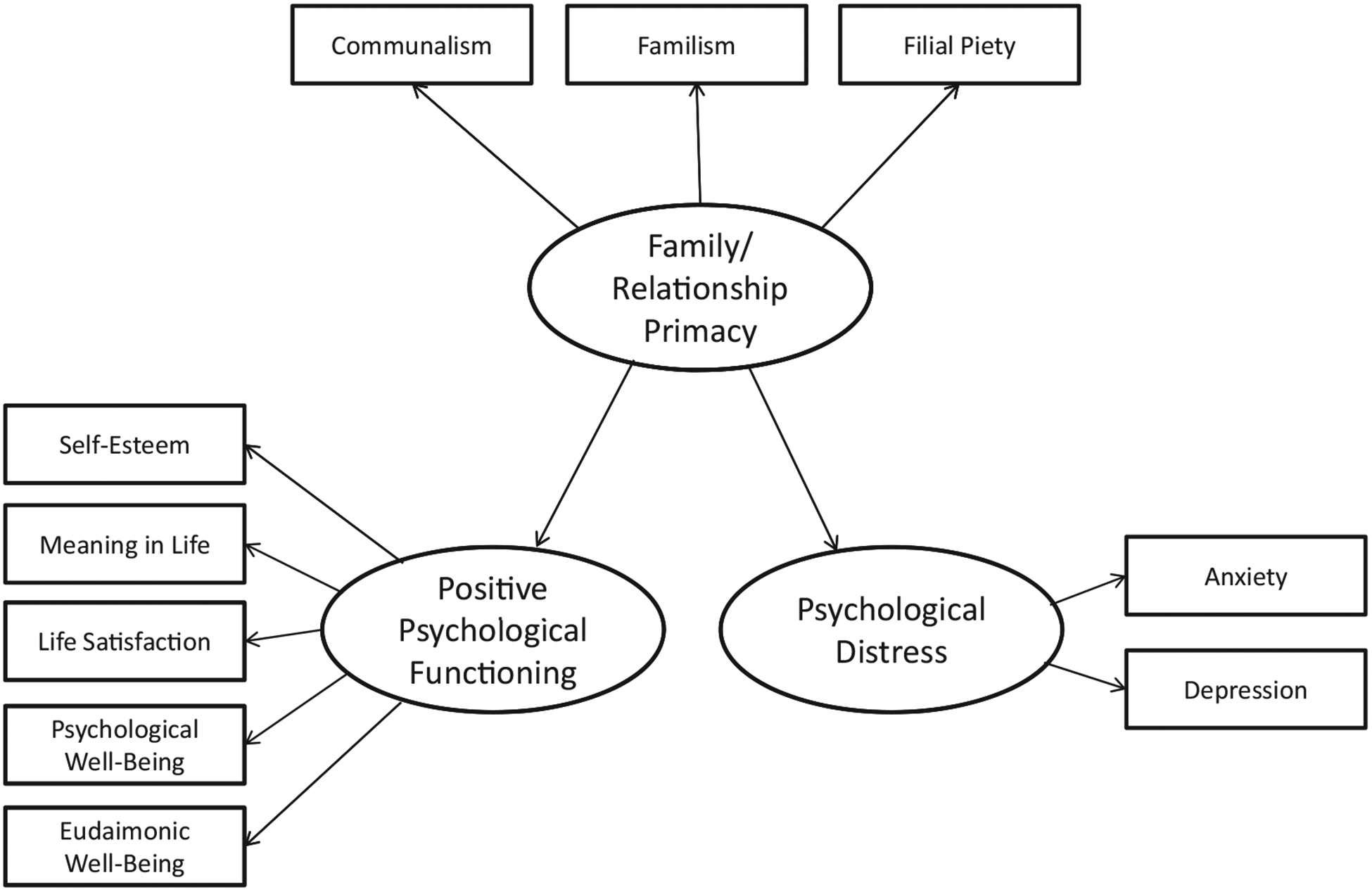

Analyses for Study 2 included two primary steps. First, we estimated a measurement model to ensure that each latent variable was sufficiently and strongly represented by the indicators used to define it. Second, we estimated a multivariate model where culturally specific value orientations were allowed to predict indices of well-being and distress (see Figure 2). In all of the models estimated for Study 2, because we had enough sites to estimate a multilevel model, we used the sandwich estimator (Kauermann & Carroll, 2001) to control for nesting of participants within sites. The sandwich estimator adjusts the standard errors for model parameters to account for multilevel nesting, but the “site” level of analysis is not explicitly modeled. This technique is therefore useful when the goal is to adjust standard errors to account for multilevel nesting, but not to examine site-level effects.

Figure 2.

Structural model for Study 2.

Measurement Models

The first step of analysis was to estimate a measurement model where each construct (family/relationship primacy, positive psychosocial functioning, and psychological distress) was defined by the indicator variables used to measure it (cf. Brown, 2006). This model allowed us to (a) ensure that the various indicators for each latent construct clustered together as expected and (b) obtain indices of overall model fit. We also calculated the reliability of each latent construct, where reliability is posited as the ratio of the variance explained by the latent variable to the overall variability among the indicators (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Correlations among the indicator variables ranged from .70 to 79 for family/ relationship primacy, and from .47 to .67 (mean .56) for positive psychological functioning. For psychological distress, the correlation between anxiety and depression was .82.

The measurement model provided a good fit to the data, χ2(31) = 609.69, p < .001; CFI = .96; NNFI = .95; RMSEA = .044 (90% CI = .041 to .047). Reliability for the positive psychosocial functioning construct was .87, with factor loadings ranging from .64 to .82. Reliability for the psychological distress construct was .91, with factor loadings of .85 and .97. Reliability for the family/relationship primacy construct was .89, with factor loadings between .80 and .90.

We then estimated directional paths from family/relationship primacy to positive psychological functioning and psychological distress. Results indicated that family/relationship primacy was positively related to both positive psychosocial functioning, β= .18, p < .001, and psychological distress, β= .06, p < .001. However, the percentages of variability explained were very small—3% for positive psychological functioning and less than 1% for psychological distress.

We then estimated the extent to which this model would fit equivalently across gender and across the four largest ethnic groups in the sample (White, Black, Hispanic, and Asian). Metric invariance tests were conducted using the same procedures used in Study 1. The invariance tests across ethnicity again included Whites, Blacks, Hispanics, and Asians—the four ethnic groups with sufficient sample sizes. Results indicated that the associations of the family/relationship primacy construct with well-being and with distress were consistent across gender, Δχ2(2) = 2.89, p = .24; ΔCFI < .001; ΔNNFI < .001, and across ethnicity, Δχ2(6) =10.43, p = .11; ΔCFI < .001; ΔNNFI < .001.

General Discussion1

The purpose of the present studies was to examine the convergence among three culturally specific, collectivist-based value systems—communalism, familism, and filial piety—as well as to gauge the associations of these value systems to other cultural indices and to positive psychological functioning and psychological distress. Whereas the extant literature has been somewhat scattered, often relying on samples from only one ethnic group and using only one cultural values variable, in the present study we used large and ethnically diverse samples, measured three different purportedly culturally specific values, and examined the equivalence of findings across ethnicity. Although the constructs and measures were based on cultural beliefs and values from different ethnic groups originating from the African diaspora, Latin America, and Southern and Eastern Asia, respectively, communalism, familism, and filial piety share a number of conceptual and empirical commonalities. Most evident is that all of these value systems imply the primacy of family and that the welfare of the group takes precedence over the individual’s own needs—and all of them appear relevant to all four major ethnic groups included in our samples.

However, these value systems—especially familism and filial piety—appear to have been endorsed more strongly by minority group members than by Whites. Communalism, which implies a value orientation centered around social ties rather than individual achievements, appears to involve only small ethnic differences. However, familism and filial piety go a step further and imply lifelong subjugation of self for the family—such as obligations to obey, honor, and take care of one’s parents and other family members, as well as the importance of honoring (and avoidance of incurring shame or disrespect to) one’s family. Communalism does not include this aspect of subjugation and obligation. It is interesting, however, Blacks—for whom communalism was proposed as a culturally specific construct, scored highest on communalism, familism, filial piety, and the latent family/relationship primacy construct. Hispanics—and Asians to a lesser extent—tended to score lower on these culturally specific value orientations. Although immigrants often adapt to American culture over time and across generations, at least to some extent (Alba & Nee, 2006), African Americans have maintained a separate cultural identity— somewhat by choice, somewhat out of necessity, and somewhat due to discrimination—for most of the United States’ history (Nobles et al., 1987). Collectivist value systems may therefore be maintained more strongly among African Americans (and immigrant Blacks, who may acculturate to an African American belief system; Portes & Rumbaut, 2006) than among other ethnic groups. Thus, with regard to the tension between culturally specific and universal aspects of collectivism, it appears that there is an interesting balance. On the one hand, collectivism is “universally” found in all four major ethnic groups included in the present study (Blacks, Hispanics, Asians, and Whites). On the other hand, collectivism is differentially endorsed by these ethnic groups, with Blacks representing the most collectivist group according to the family/relationship primacy construct. In other words, both culturally specific and transcultural elements exist in the family/ relationship primacy construct, as demonstrated by the present findings.

Results of Study 2 indicated that endorsing communalism, familism, and filial piety was associated, albeit to a small extent, with increased well-being but also somewhat higher distress. As Keyes (2005) reported, adaptive and maladaptive functioning are not necessarily inverses of one another. It is possible that the increased well-being associated with communalism, familism, and filial piety may result from the social ties and family closeness that are likely associated with these value orientations (cf. Yeh & Bedford, 2003). The small relationship with distress may be driven by incompatibilities between these collectivist-based value orientations and the individualism characterizing American culture. It appears that putting others, particularly family, before oneself serves to promote individual well-being, but may also be associated with some distress, across ethnicity. The United States has been rated as the most highly individualistic, and least collectivistic, country in the world (Hofstede, 2001)—suggesting that collectivist-oriented attitudes and behaviors may be incompatible with American cultural expectations. Familism and filial piety, for example, include obeying parents even when one does not agree, as well as caring for elderly parents in the home (Bedford & Hwang, 2003; Sabogal et al., 1987)—cultural mores that are at variance with the prevailing American culture. However, this explanation for the positive relationship between family/ relationship primacy and distress should be considered tentative, given that we did not examine other important and more proximal predictors of distress. Other studies (e.g., Smokowski & Bacallao, 2007) have found inverse relationships between collectivist orientations and distress.

It is noteworthy that, although European Americans tended to endorse the collectivist-based family/relationship primacy to a lesser extent compared to other ethnic groups, the structural relationships of these values to well-being and distress were largely consistent across ethnic groups. That is, although Whites were less likely to endorse these values compared to members of minority groups, White individuals who endorse these collectivist-based values would likely be afforded a similar degree of well-being as someone from another ethnic group with equivalent endorsement of these values. As a result, it is not ethnicity per se, but rather the endorsement of specific cultural values, that can drive the relationship to specific dimensions of psychological functioning.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

The present results should be interpreted in light of at least three important limitations. First, although a great deal of research in cultural psychology is conducted with college students, it is important to also include nonstudent emerging adults in cultural psychology studies. Non-college-attending emerging adults may have fewer opportunities to engage in ethnocultural exploration. Second, the cross-sectional nature of the present studies allows us to discuss associations, but it does not permit us to draw conclusions about the direction of effects. That is, although our perspective holds that family/relationship primacy facilitates well-being, we cannot rule out the possibility that individuals with high levels of well-being may then be inclined to adopt collectivist-type cultural values. It is important for future studies to utilize longitudinal designs where the direction of effects can be empirically ascertained. Third, the findings for Study 2 were quite modest, suggesting that family/relationship primacy may be less strongly related to adaptive and maladaptive aspects of functioning than we had expected.

The identification of the family/relationship primacy construct in the present study opens up some exciting possibilities for future research. First, it is possible that variations in family/relationship primacy may occur not only due to ethnic differences, but also to variations within ethnic groups. This variation may be due to individuals’ level of biculturalism and the degree to which they adhere to both their culture-of-origin values as well as more mainstream American values. Moreover, it is possible that the associations of family/relationship primacy to positive and negative functioning may be moderated by the immediate cultural context (e.g., whether the context is supportive of collectivist value systems) or region of the United States. Clustering techniques such as cluster analysis or latent class analysis may help to detect heterogeneity both between and within ethnic groups, as well as to permit examination of variables that predict such heterogeneity. Second, site-level effects remain to be examined using multilevel modeling techniques. It is possible, for instance, that attending a commuter college or university where most students reside at home with their parents may encourage collectivism and may accentuate the effects of family/relationship primacy on psychosocial outcomes, whereas attending a large state university where most students reside on campus may encourage individualism and may attenuate these effects. It is important for future research to examine these, as well as other, possibilities.

Despite these limitations and caveats, the present studies have empirically demonstrated that the cultural values drawn from three very distinct ethnic backgrounds are quite similar and can be combined under the rubric of collectivism. Moreover, across ethnic groups, these values have been shown to be facilitative of well-being and somewhat positively related to distress. At the same time, ethnic differences emerged in the extent to which the family/relationship primacy construct was endorsed. We hope that the present results will lead to further research using multiple methods to shed more light on the continuing debate over what is culture-specific and transcultural, especially in terms of value orientations.

Footnotes

The discussion for Study 2 is included as part of the General Discussion section.

Contributor Information

Seth J. Schwartz, University of Miami

Robert S. Weisskirch, California State University-Monterey Bay

Eric A. Hurley, Pomona College

Byron L. Zamboanga, Smith College

Irene J. K. Park, University of Notre Dame

Su Yeong Kim, University of Texas at Austin.

Adriana Umaña-Taylor, Arizona State University.

Linda G. Castillo, Texas A&M University

Elissa Brown, St. John’s University.

Anthony D. Greene, University of North Carolina-Charlotte

References

- Alba R, & Nee V (2006). Remaking the American mainstream: Assimilation and contemporary immigration. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, & Steer RA (1988). An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56, 893–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedford OA (2004). The individual experience of guilt and shame in Chinese culture. Culture & Psychology, 10, 29–52. [Google Scholar]

- Bedford OA, & Hwang K-K (2003). Guilt and shame in Chinese culture: A cross-cultural framework from the perspective of morality and identity. Journal for the Theory of Social Behavior, 33, 127–144. [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt H, & Lopez SR (1993). The study of culture, ethnicity, and race in American psychology. American Psychologist, 48, 629–637. [Google Scholar]

- Bettendorf SK, & Fischer AR (2009). Cultural strengths as moderators of the relationship between acculturation to the mainstream U.S. society and eating-and body-related concerns among Mexican American women. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 56, 430–440. [Google Scholar]

- Boykin AW, Albury A, Tyler KM, Hurley EA, Bailey CT, & Miller OA (2005). Culture-based perception of academic achievement among low-income elementary students. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 11, 339–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boykin AW, & Allen BA (2003). Cultural integrity and schooling outcomes of African American schoolchildren from low-income backgrounds In Pufall P & Undsworth R (Eds.), Childhood revisited. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boykin AW, Jagers RJ, Ellison C, & Albury A (1997). The communalism scale: Conceptualization and measurement of an Afrocultural social ethos. Journal of Black Studies, 27, 409–418. [Google Scholar]

- Brown R, Adler N, Worthman C, Copeland W, Costello EJ, & Angold A (2008). Cultural and community determinants of subjective social status among Cherokee and White youth. Ethnicity and Health, 13, 289–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA (2006). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM (2001). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. New Jersey: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo LG, Conoley CW, & Brossart DF (2004). Acculturation, White marginalization, and family support as predictors of perceived distress in Mexican American female college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 51, 151–157. [Google Scholar]

- Chen SX, Bond MH, & Tang D (2007). Decomposing filial piety into filial attitudes and filial enactments. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 10, 213–223. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung GW, & Rensvold RB (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 9, 233–255. [Google Scholar]

- Chirkov V (2009). Critical psychology of acculturation: What do we study, and how do we study it, when we investigate acculturation? International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 33, 94–105. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences.Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Coon H, & Kemmelmeier M (2001). Cultural orientations in the United States: Re-examining differences among ethnic groups. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 32, 348–364. [Google Scholar]

- Davey A, & Savla J (2010). Statistical power analysis with missing data: A structural equation modeling approach. New York: Taylor and Francis. [Google Scholar]

- DeVos T, & Banaji MR (2005). American = White? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 447–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Suh EM, Lucas RE, & Smith HL (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 276–302. [Google Scholar]

- Eap S, DeGarmo DS, Kawakami A, Shelley NH, Hall GCN, & Teten AL (2008). Culture and personality among European American and Asian American men. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 39, 630–643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fornell C, & Larcker DF (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar]

- Ghazarian SR, Supple AJ, & Plunkett SW (2008). Familism as a predictor of parent-adolescent relationships and developmental outcomes for adolescents in Armenian American immigrant families. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 17, 599–613. [Google Scholar]

- Hancock GR, Lawrence FR, & Nevitt J (2000). Type I error and power of latent mean methods and MANOVA in factorially invariant and noninvariant latent variable systems. Structural Equation Modeling, 7, 534–556. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez D (2009). Demographic change and the life circumstances of immigrant families. Future of Children, 14, 17–47. [Google Scholar]

- Ho D (1994). Filial piety, authoritarian moralism, and cognitive conservatism in Chinese societies. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs, 114, 349–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede G (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across nations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Huntington SP (2004). The Hispanic challenge. Foreign Policy, 141,30–45. [Google Scholar]

- Jagers RJ, & Mock LO (1995). The communalism scale and collectivistic-individualistic tendencies: Some preliminary findings. Journal of Black Psychology, 21, 153–167. [Google Scholar]

- Kao HF, McHugh ML, & Travis SS (2007). Psychometric tests of expectations to filial piety scale in a Mexican-American population. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 16, 1460–1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao HF, & Travis SS (2005). Effects of acculturation and social exchange on the expectations of filial piety among Hispanic/Latino parents of adult children. Nursing and Health Sciences, 7, 226–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauermann G, & Carroll RJ (2001). A note on the efficacy of sandwich covariance matrix estimation. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 96, 1387–1396. [Google Scholar]

- Keyes CLM (2005). Mental illness and/or mental health: Investigating axioms of the complete state model of health. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73, 539–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes CLM, Shmotkin D, & Ryff CD (2002). Optimizing well-being: The empirical encounter of two traditions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 1007–1022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiang L, Yip T, & Fuligni AJ (2008). Multiple social identities and adjustment in young adults from ethnically diverse backgrounds. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 18, 643–670. [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB (2006). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kuppens P, Realo A, & Diener E (2008). The role of positive and negative emotions in life satisfaction judgment across nations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95, 66–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen LJ (2004). The foreign-born population in the United States: 2003. Current Population Reports, P20–551 Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau. [Google Scholar]

- Le TN, & Kato T (2005). The role of peer, parent, and culture in risky sexual behavior for Cambodian and Lao/Mien adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 38, 288–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leong FTL, Inman AG, Ebreo A, Yang LH, Kinoshita LM, & Fu M (Eds.). (2006). Handbook of Asian American psychology. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Little TD, Cunningham WA, Shahar G, & Widaman KF (2002). To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling, 9, 151–173. [Google Scholar]

- Lugo Steidel AG, & Contreras JM (2003). A new familism scale for use with Latino populations. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 25, 312–330. [Google Scholar]

- Markus HR, & Kitayama S (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98, 224–253. [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Kulis S, & Hecht ML (2001). Ethnic labels and ethnic identity as predictors of drug use among middle school students in the Southwest. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 11, 21–48. [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto D (2003). The discrepancy between consensual-level culture and individual-level culture. Culture and Psychology, 9, 89–95. [Google Scholar]

- Mattis JS, Beckham WP, Saunders BA, Williams JE, McAllister D, Myers V, … Dixon C (2004). Who will volunteer? Religiosity, everyday racism, and social participation among African American men. Journal of Adult Development, 11, 1573–3440. [Google Scholar]

- Nobles WW, Goddard LL, Cavil WE, & George PY (1987). African-American families: Issues, insights and directions. Oakland, CA: Black Family Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Oyserman D, Coon HM, & Kemmelmeier M (2002). Rethinking individualism and collectivism: Evaluation of theoretical assumptions and meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin, 128, 3–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park YS, & Kim BSK (2008). Asian and European American cultural values and communication styles among Asian American and European American college students. Cultural Diversity &Ethnic Minority Psychology, 14, 47–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavot W, & Diener E (1993). Review of the satisfactions with life scales. Psychological Assessment, 5, 164–177. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS (2003). Ethnic identity and acculturation In Chun KM, Organista PB, & Marín G (Eds.), Acculturation: Advances in theory, measurement, and applied research (pp. 63–82). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Ponterotto JG, Casas JM, Suzuki LA, & Alexander CM (Eds.). (2001). Handbook of multicultural counseling. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Portes A, & Rumbaut RG (2006). Immigrant America: A portrait (3rd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Portes A, & Rumbaut RG (Eds.). (2001). Legacies: The story of the immigrant second generation. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D scale. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rao N, McHale J, & Pearson E (2003). Links between socialization goals and child-rearing practices in Chinese and Indian mothers. Infant and Child Development, 12, 475–492. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Drake D, Hughes D, & Way N (2009). A preliminary analysis of associations among ethnic-racial socialization, ethnic discrimination, and ethnic identity among urban sixth graders. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 19, 558–584. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, Phinney JS, Masse LC, Chen YR, Roberts CR, & Romero A (1999). The structure of ethnic identity in young adolescents from diverse ethnocultural groups. Journal of Early Adolescence, 19, 301–322. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez L, Schwartz SJ, & Whitbourne SK (2010). American identity crisis: The relation between national, cultural, and personal identity in a multiethnic sample of emerging adults. Journal of Adolescent Research, 25, 324–349. [Google Scholar]

- Rogoff B, & Chavajay P (1995). What’s become of research on the cultural basis of cognitive development? American Psychologist, 50, 859–877. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M (1979). Conceiving the self. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Ruini C Ottolini F, Rafanelli C Tossani E, Ryff CD, & Fava GA (2003). The relationship of psychological well-being to distress and personality. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 72, 268–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, & Deci EL (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 141–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 1069–1081. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD, & Keyes CLM (1995). The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 719–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD, & Singer BH (2006). Best news yet on the six-factor model of well-being. Social Science Research, 35, 1103–1119. [Google Scholar]

- Sabogal F, Marin G, Otero-Sabogal R, Marin B, & Perez-Stable EJ (1987). Hispanic familism and acculturation: What changes and what doesn’t. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 9, 183–205. [Google Scholar]

- Schildkraut DJ (2007). Defining American identity in the twenty-first century: How much “there” is there? Journal of Politics, 69, 597–615. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ (2007). The applicability of familism to diverse ethnic groups: A preliminary study. The Journal of Social Psychology, 147, 101–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Zamboanga BL, & Szapocznik J (2010). Rethinking acculturation: Implications for theory and research. American Psychologist, 65, 237–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, & Zamboanga BL (2008). Testing Berry’s model of acculturation: A confirmatory latent class approach. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 14, 275–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Zamboanga BL, Rodriguez L, & Wang SC (2007). The structure of cultural identity in an ethnically diverse sample of emerging adults. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 29, 159–173. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Zamboanga BL, & Weisskirch RS (2008). Broadening the study of the self: Integrating the study of personal identity and cultural identity. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2, 635–651. [Google Scholar]

- Singelis TM (1994). The measurement of independent and interdependent self-construals. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 20, 580–591. [Google Scholar]

- Singelis TM, Triandis HC, Bhawuk DPS, & Gelfand MJ (1995). Horizontal and vertical dimensions of individualism and collectivism: A theoretical and measurement refinement. Cross-Cultural Research, 29, 240–275. [Google Scholar]

- Smokowski PR, Rose R, & Bacallao ML (2008). Acculturation and Latino family processes: How cultural involvement, biculturalism, and acculturation gaps influence family dynamics. Family Relations, 57, 295–308. [Google Scholar]

- Steger MF, & Frazier P (2005). Meaning in life: One link in the chain from religiousness to well-being. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52, 574–582. [Google Scholar]

- Steger MF, Frazier P, Oishi S, & Kahler M (2006). The Meaning in Life Questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53, 80–93. [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson M (2000). Development and validation of the Stephenson multigroup acculturation scale (SMAS). Psychological Assessment, 12, 77–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepick A, Dutton Stepick C, & Vanderkooy P (in press). Becoming American In Schwartz SJ, Luyckx K, & Vignoles VL (Eds.), Handbook of identity theory and research. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Orozco MM, & Páez MM (Eds.). (2002). Latinos: Remaking America. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Swann WB Jr., Chang-Schneider C, & Larsen McClarty K (2007). Do people’s self-views matter? Self-concept and self-esteem in everyday life. American Psychologist, 62, 84–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triandis HC (1995). Individualism and collectivism Boulder, CO: Westview Press. [Google Scholar]

- Triandis HC, & Gelfand MJ (1998). Converging measurement of horizontal and vertical individualism and collectivism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 118–128. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler KM, Dillihunt ML, Boykin AW, Coleman ST, Scott DM, Tyler CMB, & Hurley EA (2008). Examining cultural socialization within African American and European American households. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 14, 201–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger JB, Ritt-Olson A, Teran L, Huang T, Hoffman BR, & Palmer P (2002). Cultural values and substance use in a multiethnic sample of California adolescents. Addiction Research & Theory, 10, 257–279. [Google Scholar]

- Valdés MI (2008). Hispanic customers for life: A fresh look at acculturation. New York: Paramount. [Google Scholar]

- Vandello JA, & Cohen D (1999). Patterns of individualism and collectivism across the United States. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 279–292. [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberg RJ, & Lance CE (2000). A review and synthesis of the measurement invariance literature: Suggestions, practices, and recommendations for organizational research. Organizational Research Meth- ods, 3, 4–70. [Google Scholar]