Abstract

This work critically discusses the direct and indirect effects of natural polyamines and their catabolites such as reactive oxygen species and γ-aminobutyric acid on the activity of key plant ion-transporting proteins such as plasma membrane H+ and Ca2+ ATPases and K+-selective and cation channels in the plasma membrane and tonoplast, in the context of their involvement in stress responses. Docking analysis predicts a distinct binding for putrescine and longer polyamines within the pore of the vacuolar TPC1/SV channel, one of the key determinants of the cell ionic homeostasis and signaling under stress conditions, and an additional site for spermine, which overlaps with the cytosolic regulatory Ca2+-binding site. Several unresolved problems are summarized, including the correct estimates of the subcellular levels of polyamines and their catabolites, their unexplored effects on nucleotide-gated and glutamate receptor channels of cell membranes and Ca2+-permeable and K+-selective channels in the membranes of plant mitochondria and chloroplasts, and pleiotropic mechanisms of polyamines’ action on H+ and Ca2+ pumps.

Keywords: abiotic stress, Ca2+ ATPase, H+-ATPase, ion channel, organelle, polyamines, TPC1, vacuole

Introduction

Polyamines (PAs) are plant growth regulators and important components of plant stress responses (Alcázar et al., 2010; Takahashi and Kakehi, 2010; Pottosin and Shabala, 2014; Pál et al., 2015; Paschalidis et al., 2019). PAs putrescine2+ (Put), spermidine3+ (Spd), and spermine4+ (Spm) are natural polycations and, therefore, can affect different cation transporters, including those regulating Ca2+ homeostasis and signaling (Pottosin and Shabala, 2014). Stress-induced PA changes can remodel ion transport across cellular membranes, with important consequences for plant performance (Pottosin and Shabala, 2014; Pottosin, 2015). PA effects on ion transport depend on cell-, tissue-, and genotype-specificity and growth conditions (Pandolfi et al., 2010). Most likely, PAs were not originally designed as signaling compounds but then acquired this function during evolution by leveraging on a strong variation of levels of individual PAs and their catabolites during plant responses to changing environment. Owing to this level of complexity, the initial question should be related to the primary effects of different PAs and their catabolites (e.g., ROS) on individual ion transporters. Are these effects direct and specific for different PAs? Are there allosteric PA-binding sites? In vivo effects may be also dependent on the PA metabolism and traffic, and an involvement of the intermediate signaling. Finally, catabolization of PAs and signaling by their catabolites, ROS and GABA, should be considered. The aim of this work is to elucidate diverse effects of PAs on key plant membrane ion transporters to stimulate more focused studies in this field.

Polyamine Transport May Affect Membrane Potential and ΔpH

Polyamines induce a rapid depolarization in roots and leaves (Fromm et al., 1997; Ozawa et al., 2010; Pottosin et al., 2014a). A significant part of it is due to the traffic per se of these polycations across the plasma membrane, PM (Pottosin et al., 2014a). Interestingly, PM Put transporter, PUT3, is phosphorylated by SOS2 (CIPK24). It forms a tertiary complex with SOS1 (PM Na+/H+ antiporter) and SOS2, key elements in response to salinity; within this complex, the activity of PUT3 and SOS1 is synergistically modulated (Chai et al., 2020). Thus, Put uptake can contribute to the pH and Na+ regulation. PA traffic is documented for most intracellular membranes, albeit transporters, which facilitate PA uptake into plant vacuoles and mitochondria, remain elusive (Fujita and Shinozaki, 2015). No specific PA transporter was postulated for chloroplasts, but chloroplasts represent the main source of Put synthesis in photosynthetic tissues (Borrell et al., 1995). In Arabidopsis chloroplasts, Put may account for up to 40% of the total cellular Put (Krueger et al., 2011). A small but significant fraction of unprotonated (uncharged) Put can freely diffuse through the thylakoid membrane and partly buffer the light-induced thylakoid lumen acidification, changing the proportion between membrane potential (ΔΨ) and ΔpH across the thylakoid membrane (Ioannidis et al., 2006, 2012). Under salinity, Put-induced increase in ΔΨ at the expense of ΔpH stimulates cyclic electron flow and decreases pH-dependent non-photochemical quenching. This increases the quantum yield by PSII, decreasing the overreduction of PSI acceptors and, eventually, enhancing the ATP production (Wu X. et al., 2019). A stark increase in the Put production upon K+ deficiency is accompanied by an increase in the Mg2+ content. Mg2+ uptake into thylakoids causes an opposite effect on ΔΨ/ΔpH partition and favors lumen acidification and stromal alkalinization, optimal for the Calvin cycle (Cui et al., 2020).

Direct Effects of Polyamines on the Tonoplast Cation Channels

Tonoplast harbors two types of cation channels: slow (SV/TPC1) and fast (FV) vacuolar channels. FV channels are inhibited by micromolar Ca2+ and Mg2+ and conduct small monovalent cations indiscriminately, whereas SV channels are activated by an elevated cytosolic Ca2+ and conduct both monovalent and divalent cations with a little preference (Pottosin and Dobrovinskaya, 2014, 2018). Both channels are rapidly, reversibly, and directly suppressed by PAs (Pottosin and Shabala, 2014; Table 1). PAs cause the voltage-dependent block of the SV/TPC1 pore. In agreement with an early study (Colombo et al., 1992), PAs can be transported by SV/TPC1. The FV current is intrinsically flickering, and its inhibition by cytosolic PAs is voltage independent. It remains to be elucidated whether PAs block the FV channel or alter its gating.

TABLE 1.

Key plant plasma membrane and vacuolar ion transporters—targets for polyamines.

| Ion transporter | Ionic transport function/physiological implications | Involvement in stress responses | PA effect (half-efficient concentration) |

| Slow vacuolar SV channel (TPC1) | Transport of Ca2+, Na+, Mg2+ K+, NH4+, and other small cations across tonoplast (1), vacuolar K+ release/cytoplasmic K+ homeostasis (2), Ca2+- and voltage-induced vacuole electrical excitability/intracellular signaling (3,4), Ca2+ release and long-distance signaling/sensors and amplifiers of Ca2+ signal, ROS, and Ca2+ interplay (3,5–7), cation homeostasis (8,9), ABA signaling in seed germination and stomatal closure (10,11) | Salt stress (detrimental vacuolar Na+ leak) (3,5,7,12–14), long-distance signaling (5), aluminum tolerance (15), lead stress response (16), wounding via jasmonate signaling (17), insect herbivory response (6), hypoxia sensors (18) | Direct, reversible. Voltage-dependent block from either membrane side (Spm4+ 50 μM > Spd3+ 500 μM > Put2+ 3 mM) (19–21) |

| Fast vacuolar FV channel (unknown molecular identity) | NH4+ > K+ > Na+ transport (22), K+ uptake and release/Volume adjustment via auxin (23), tonoplast electric potential regulation (24), K+ sensing/intracellular K+ homeostasis (25), vacuolar volume adjustment via auxin (26) | Detrimental for salt stress (vacuolar Na+ leak) (13,24,27), K+ deprivation (vacuolar K+-cycling) (25,28) | Direct, reversible, voltage-independent, from the cytosolic side (Spm4+ 6 μM > Spd3+ 80 μM >> Put2+ 4 mM) (19,21,29) |

| Vacuolar K+ VK channel (TPK1) | Selective K+ transport across tonoplast (30–33), K+ homeostasis, vacuolar K+ mobilization, stomata closure (34–36), mechano- and osmo-sensor (37), vacuolar excitability in combination with TPC1(4) | Salt stress (31,33,38) and K+ deprivation (28,34,36), tolerance by refilling of cytosolic K+ | Voltage-independent, cytosolic side block (Spm4+ ∼ Spd3+ 0.5 mM) (39) |

| Inward-rectifying shaker K+ channels (AKT1, KAT1) | K+ uptake and tissue K+ transport (33,40–44) and stomata opening (45,46) | K+ starvation/deficiency, K+ uptake (33,47,48), Fe2+ toxicity tolerance (49), drought tolerance by enhancing root K+ uptake (42,50,51) | Indirect inhibition, cytosolic side (52), indirect, extracellular side (53,54), voltage-independent (Spm4+ ∼ Spd3+ ∼ Put2+ 0.5 –1 mM), inhibition via increase in PIP2 (55) |

| Outward-rectifying shaker K+ Channels (SKOR, GORK) | K+ efflux, general metabolic switch, cell death (33,56,57), K+ loading into xylem, SKOR (43,44,58), stomata closure, GORK (59,60), initial depolarization phase of the action potentials (61) | Salt stress (sensitivity via K+ loss) (43,57,58,62,63), cell death (64), relocation of energy from metabolism to defense (56), oxidative stress tolerance by cation distribution (65) | Indirect inhibition from extracellular side, voltage-independent (Spm4+ ∼ Put2+ 1 mM) (54), activation from extracellular side via increase in PIP2 and PLDδ activity (Spm4+ = tSpm4+ > Spd3+ > > Put2+≈ Dap2+) (66,67), GABA formed by Put2+ catabolism decreases the expression (63) |

| Voltage-independent non-selective cation channels VI-NSCC (uncertain molecular identity) | General cation transport/uptake of nutrients, growth and development, Ca2+ influx/transduction of stimuli (cyclic nucleotides, membrane stretch, amino acids, and purines) (1,68) | Salt stress sensitivity, Na+ influx (1,68–71) | Extracellular side, voltage-independent inhibition (Spm4+ ∼ Spd3+ (∼1 mM) > Put2+) (53), extracellular side, indirect? (Spm4+ ∼ Spd3+ ∼ Put2+ 1 mM) (72.73) |

| Reactive oxygen species-induced Ca2+ influx ROSIC Weakly voltage-dependent, OH•-induced non-selective conductance (unknown molecular identity) | Non-selective cation and small anions conductance (74–77), Ca2+ influx and signaling via ROS and ABA/stomatal closure (75,76,78), polarized (root hair, pollen tube) growth (74,79) | Drought stress, signaling (78), salinity (64), hypersensitive response to biotic stress (80) | Extracellular PAs act as cofactors for ROSIC activation by OH (Spm4+ ∼ Spd3+ ∼ Put2+ 1 mM) (75,81,82), PA export and oxidation by DAO or PAO results in the ROS burst in the apoplast and activation of Ca2+ influx via ROSIC upon pathogen attack (83–85), salinity (86), ABA-induced stomata closure (87) |

| H+-pump P-type ATPase (AHA: auto inhibited H+-ATPAse) | Drives H+ extrusion and PM hyperpolarization (88,89), intracellular and apoplastic pH regulation (90–94), fueling H+-coupled secondary transports (95–97), plant growth and development, stomatal aperture (98–101) | Salt stress, generation of electric and pH gradients for K+ uptake (43,62,102–105), Al3+ toxicity/tolerance (106,107), pathogen infection sensitivity (97), alkaline stress tolerance (108,109), drought adaptation by auxin (110), wounding, leaf-to-leaf electrical signaling and plant defense (111) | Activation/Stimulation Rapid activation (Spm4+ 0.1 mM, Spd3+ or Put2+ 1mM) (112), (Put2+ in the elongation zone) (113), (Spm4+ ∼ Spd3+ ∼ Put2+ ∼1mM) (114), (Spm4+ > Spd3+ > Put2+ 1 mM), (80) via 14-3-3 proteins binding (Spm4+ only, ∼0.1mM) (115), via GABA by Put2+ catabolism (63) Inhibition/Suppression Rapid (Spm4+ 1 mM) (112,113), long-term suppression/decrease in expression (Put2+∼ Spm4+ ∼ Spd3+ 50 μM) (116) Restoration Long term (Put2+ or Spd3+ 0.5–1 mM and Spm4+ 1 mM) (102,117) |

| Ca2+-pump P-type ATPase PMCA (the plasma membrane located Ca2+-ATPases) Type IIB (ACA: auto-inhibited Ca2+-ATPase) | Ca2+ extrusion from cytosol, Ca2+ signaling, protein glycosylation, protein and polysaccharide secretion, enzymes activation, stomatal closure (118–123), plant growth and development (124–126) | Abiotic stresses (118,127), Ca2+ stress (deficiency) (128), salinity adaptation (118,119), chilling (129), anoxia (118), Mn2+ toxicity (119), pathogen-induced cell death and signaling (130) | Rapid activation (Spm4+ ∼ Put2+ 0.1–1 mM) (75,81,82,119) and long-term potentiation via Spm4+, Spd3+, or Put2+ production by salicylic acid (131) |

1Pottosin and Dobrovinskaya, 2014; 2Hedrich et al., 2018; 3Pottosin and Dobrovinskaya, 2018; 4Jaślan et al., 2019; 5Choi et al., 2014; 6Kiep et al., 2015; 7Evans et al., 2016; 8Hedrich and Marten, 2011; 9Hedrich et al., 2018; 10Peiter et al., 2005; 11Peiter, 2011; 12Bonales-Alatorre et al., 2013; 13Shabala et al., 2020; 14Koselski et al., 2019; 15Wherrett et al., 2005; 16Miśkiewicz et al., 2020; 17Lenglet et al., 2017; 18Wang et al., 2017; 19Dobrovinskaya et al., 1999b; 20Dobrovinskaya et al., 1999a; 21Pottosin and Shabala, 2014; 22Brüggemann et al., 1999; 23Burdach et al., 2020; 24Tikhonova et al., 1997; 25Pottosin and Martínez-Estévez, 2003; 26Burdach et al., 2018; 27Pottosin and Muñiz, 2002; 28Cui et al., 2020; 29Brüggemann et al., 1998; 30Ward and Schroeder, 1994; 31Pottosin et al., 2003; 32Bihler et al., 2005; 33Chérel and Gaillard, 2019; 34Gobert et al., 2007; 35Ragel et al., 2019; 36Tang et al., 2020; 37Maathuis, 2011; 38Wang et al., 2013; 39Hamamoto et al., 2008; 40Dreyer et al., 2017; 41Chen et al., 2017; 42Feng et al., 2020; 43Rubio et al., 2020; 44Raddatz et al., 2020; 45Kwak et al., 2001; 46Wang Y. et al., 2018; 47Wang and Wu, 2013; 48Zhang et al., 2018; 49Wu L. B. et al., 2019; 50Shabala and Cuin, 2008; 51Ahmad et al., 2016; 52Liu et al., 2000; 53Zhao et al., 2007; 54Pottosin, 2015; 55Xie et al., 2005; 56Demidchik, 2014; 57Adem et al., 2020; 58Gaymard et al., 1998; 59Hosy et al., 2003; 60Corratgé-Faillie et al., 2017; 61Cuin et al., 2018; 62Buch-Pedersen et al., 2006, 63Su et al., 2019; 64Demidchik et al., 2010; 65Garcia-Mata et al., 2010; 66Zarza et al., 2019; 67Zarza et al., 2020; 68Demidchik and Maathuis, 2007; 69Demidchik and Tester, 2002; 70Essah et al., 2003; 71Keisham et al., 2018; 72Shabala et al., 2007a; 73Shabala et al., 2007b; 74Foreman et al., 2003; 75Zepeda-Jazo et al., 2011; 76Demidchik, 2018; 77Pottosin et al., 2018; 78Pei et al., 2000; 79Wu et al., 2010; 80Pottosin et al., 2014b; 81Pottosin et al., 2012; 82Velarde-Buendía et al., 2012; 83Yoda et al., 2006; 84Marina et al., 2008; 85Moschou et al., 2009; 86Rodríguez et al., 2009; 87An et al., 2012; 88Haruta and Sussman, 2012; 89Palmgren and Morsomme, 2018; 90Marty, 1999; 91Zhu et al., 2015; 92Grunwald et al., 2017; 93Hoffmann et al., 2020; 94Gjetting et al., 2020; 95Duby and Boutry, 2009; 96Bobik et al., 2010; 97Falhof et al., 2016; 98Yamauchi et al., 2016; 99Inoue and Kinoshita, 2017; 100Hoffmann et al., 2019; 101Yamauchi and Shimazaki, 2017; 102Zhao and Qin, 2004; 103Zepeda-Jazo et al., 2008; 104Janicka et al., 2018; 105Rubio et al., 2020; 106Bose et al., 2015b; 107Zhang et al., 2017; 108Xu et al., 2012; 109Yang et al., 2019; 110Xu et al., 2013; 111Kumari et al., 2019; 112Pottosin et al., 2014a; 113Pandolfi et al., 2010; 114Reggiani et al., 1992; 115Garufi et al., 2007; 116Janicka-Russak et al., 2010; 117Liu et al., 2006; 118Kabała and Kłobus, 2005; 119Bose et al., 2011; 120Bonza et al., 2016; 121Costa et al., 2017; 122Yang et al., 2017; 123Hilleary et al., 2020; 124Behera et al., 2018; 125Yu et al., 2018; 126García-Bossi et al., 2020; 127Bonza and De Michelis, 2011; 128Aslam et al., 2017; 129Schiøtt and Palmgren, 2005; 130Zhu et al., 2010; 131Sudha and Ravishankar, 2003.

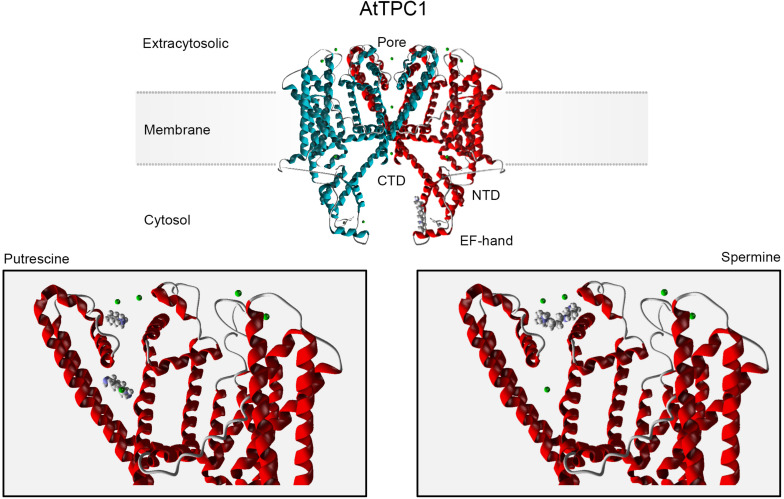

In silico analysis predicts two binding sites for Put within the TPC1 pore, one below and one above the filter (Figure 1, bottom left), in agreement with a multioccupancy block by this diamine (Pottosin, 2015). These sites overlap with the conducting route for permeable cations, implying their mutual competition. Longer Spm and Spd molecules partly share the external binding site with Put (Figure 1, bottom right), but their binding is much stronger. An additional binding site for Spm was predicted in the TPC1 cytosolic domain, overlapping with the regulatory Ca2+-binding site (Figure 1, top).

FIGURE 1.

In silico docking analysis of the TPC1 interacting sites for polyamines. The AtTPC1 dimer is depicted in the upper panel. Monomers forming the channel are differently color-coded. Molegro Virtual Docker software (MVD; Molexus IVS: http://molexus.io/molegro-virtual-docker/) was employed using the AtTPC1 structure from the Protein Data Bank (PDB: https://www.rcsb.org/structure/5EJ1). The putrescine and spermine structures were obtained from PubChem (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/1045; … 1103). The protein structure was optimized and cavities were detected for 5EJ1. Docking was performed for each cavity using the MolDock Optimizer as a search algorithm and the MolDock Score as a Scoring function. The lower panel corresponds to the docking prediction for PAs binding in the extracytosolic region. Two main binding sites for Put were predicted. The total binding energy for upper and lower binding conformations was −42.88 and −43.81, respectively (MolDockScore; MVD units). The Spm binding site partly overlaps the upper Put-binding site, with a higher binding energy (MolDockScore: −71.91 MVD units). Spm binding to this site involves two additional acidic residues, Asp 269 (−10.12 MVD units) and Glu 637 (−3.69 MVD units), which contribute by 19% into the total binding energy and determine the Spm orientation. An additional cytosolic binding site is predicted for Spm (upper panel, −73.43 MVD units), which overlaps with the EF2 hand regulatory Ca2+-binding site. Green spheres are permeable divalent cations, Ca2+ or Ba2+.

A suppression of the FV and SV channels by PAs is essential at any condition but is more important under salinity. FV and SV channels are unable to differentiate between K+ and Na+, thus mediating the Na+ leak from the vacuole (Pottosin and Dobrovinskaya, 2014). A futile vacuolar Na+ cycling has a rather high energy cost, imposing a penalty for plant performance (Shabala et al., 2020). The suppression of vacuolar FV and SV channels may also be relevant at conditions of K+ deprivation, preventing vacuolar reuptake of cytosolic K+ by FV and SV channels. Notably, the overexpression of the tonoplast K+ (Na+)/H+ antiporter NHX1, which mediates vacuolar K+ uptake, may be counterbalanced by a massive increase in Put under K+ deprivation (De Luca et al., 2018).

Indirect Effects of Polyamines on the Plasma Membrane K+ Channels

In animal systems, PAs act as direct pore-plugging agents, underlying inward rectification of K+-selective Kir channels and exerting a voltage-dependent block of a variety of cation channels, including Na+ (lacking in plants) and ligand-gated channels (Williams, 1997; Guo and Lu, 2000; Huang and Moczydlowski, 2001). Cyclic nucleotides-gated and glutamate receptor channels in animal cells are blocked by PAs with a high affinity in a charge-specific manner. No data are available for their homologs, abundant in plants.

Plant voltage-dependent K+ channels belong to the Shaker family (Sharma et al., 2013). Their counterparts in animal cells are not blocked by the physiological concentrations of PAs. Inward rectifying K+ channels in guard cells are suppressed by endogenous PAs, which promote stomata closure under drought (Liu et al., 2000). An indirect inhibition was also reported for both inward- and outward-rectifying Shaker K+ channels in roots (Table 1). Membrane-bound PIP2 is a cofactor for numerous PM cation channels in animals (Suh and Hille, 2008) and inward- and outward-rectifying Shaker K+ channels in plants (Liu et al., 2005). PAs block animal inward rectifier Kir2.1 but also activate it by strengthening the interaction with PIP2 (Xie et al., 2005). PAs induced a rapid increase in PIP2 in Arabidopsis seedling, triggering a massive K+ efflux mediated by outward-rectifying GORK channels (Zarza et al., 2020). This mechanism appears to be specific for Arabidopsis. In vivo studies on pea and barley roots did not reveal any significant Spm-induced K+ efflux (Zepeda-Jazo et al., 2011; Velarde-Buendía et al., 2012).

Pleiotropic Effects of Polyamines on H+ and Ca2+ Pumps

Operation of the PM-based H+- and Ca2+-ATPase pumps is central for responses to a variety of biotic and abiotic stresses (Table 1). An abrupt activation of H+ pumping occurs upon salt and hypertonic shock (Shabala and Cuin, 2008; Pandolfi et al., 2010; Bose et al., 2015a).

Upon long-term exposures, free and conjugated PAs could modify (either activate or inhibit) the activity of the PM H+- and Ca2+-ATPase pumps. This may be due to the changes in the protein expression, membrane composition/stability, and redox state (Srivastava and Rajbabu, 1983; Sudha and Ravishankar, 2003; Liu et al., 2005, 2014; Roy et al., 2005; Janicka-Russak et al., 2010; Du et al., 2015). Tonoplast H+ pumps, V-type ATPase and PPase, are only slightly affected by PAs, both upon direct application (Liu et al., 2004, 2006; Zhao and Qin, 2004) and after long-term exposure (Sun et al., 2002; Tang and Newton, 2005). Plant mitochondrial F-ATPase showed low sensitivity to PAs at physiological ionic conditions (Peter et al., 1981).

In pea and barley roots, PAs indiscriminately (Put∼Spm) induced eosin-sensitive Ca2+ efflux, pinpointing to the Ca2+-ATPase activation (Zepeda-Jazo et al., 2011; Velarde-Buendía et al., 2012; Pottosin et al., 2014b). Low millimolar concentrations of PAs stimulated the PM H+-ATPase activity in rice coleoptiles, but only Put can reach this concentration in planta (Reggiani et al., 1992). Spm and Spd caused a transient increase in a vanadate-sensitive H+ pumping in pea roots, whereas Put induced a sustained H+ efflux (Pottosin et al., 2014a). The general mechanism of the PM H+-ATPase activation involves a phosphorylation of a penultimate Thr, which promotes 14-3-3 protein binding and relief of the autoinhibition, while phosphorylation of other Ser and Thr residues in the C-terminal may either activate or inhibit the H+-ATPase (Falhof et al., 2016). Ca2+-dependent phosphorylation of Ser931 by SOS2-like kinase prevents the 14-3-3 protein binding, thus inhibiting the PM H+-ATPase (Fuglsang et al., 2007). PA-induced Ca2+-efflux may indirectly activate the H+-pumping in vivo by the local cytosolic Ca2+ depletion. Indeed, Put-induced stimulation of H+ pumping was suppressed by the Ca2+-pump inhibition, whereas Put did not affect the PM H+-pump in vitro. In addition, cytosolic Spm at higher concentration inhibited the H+ pumping by pea root PM vesicles (Pottosin et al., 2014a). Spm but not Spd or Put suppressed the H+ pumping in maize roots (Pandolfi et al., 2010). Contrary to this, Spm but no other PAs stimulated the PM H+-ATPase activity both in maize and Arabidopsis by a promotion of the 14-3-3 protein binding to the unphosphorylated C-terminal (Garufi et al., 2007). However, H+ efflux and H+-ATPase activity are not necessarily correlated. In its upregulated state, the PM H+-ATPase transports 1 H+ per 1 ATP, but this coupling may be loosened at high cytosolic cation concentration (Buch-Pedersen et al., 2006). Whether Spm may act as such an uncoupler remains to be elucidated. Also, Spm and Spd but not Put are able to compete with Mg2+ for binding to ATP, thus decreasing the ATPase activity, e.g., of a mitochondrial F-type ATPase (Igarashi et al., 1989). As Mg2+ and Spm binding sites in ATP are overlapped only partly, a ternary complex ATP-Mg2+-Spm can be formed, which is processed by an ATPase more rapidly than Mg-ATP (Meksuriyen et al., 1998).

Effects of Polyamine Catabolites: ROS and GABA

A substantial part of PA effects may be attributed to their catabolites, and the balance of the PA synthesis and catabolization is stress-regulated and may define the net response (Moschou et al., 2012; Pottosin et al., 2014b; Pál et al., 2015; Gupta et al., 2016). The immediate product of PA oxidation by diamine- (DAO; for Put) and polyamine- (PAO; for Spm and Spd) oxidases is H2O2. It could be converted to a more aggressive hydroxyl radical (OH•) in the presence of the transition metals in the cell wall (Demidchik, 2014) and cytosol (Rodrigo-Moreno et al., 2013). These two ROS species target two types of conductances: (1) non-selective (Ca2+-permeable) also known as ROS-activated NSCC or ROSIC (Pei et al., 2000; Demidchik and Maathuis, 2007; Zepeda-Jazo et al., 2011) and (2) outward-rectifying K+-selective channels GORK and SKOR (Demidchik et al., 2010; Garcia-Mata et al., 2010). ROS generation upon PA catabolization in the apoplast is essential for the hypersensitive response to pathogen attack, wound-healing, stomata closure, and salinity-associated ROS signaling, among all (see Tavladoraki et al., 2012; Pottosin et al., 2014b). The source depends on the relative expression of amine oxidases: mainly DAO in dicots and mainly PAO in monocots (Moschou et al., 2008). Transmission of the external ROS signal to internal signaling is mediated by ROS-activated Ca2+ influx, positively fed back to ROS production due to a Ca2+ activation of the PM-bound NADPH-dehydrogenase (Takeda et al., 2008; Demidchik et al., 2018; Pottosin and Zepeda-Jazo, 2018). In pea roots, OH• at lower and higher levels, respectively, induced a transient Ca2+ pumping by Ca2+-ATPase and a sustained Ca2+ influx via ROSIC (Zepeda-Jazo et al., 2011). OH•-induced Ca2+ pumping was potentiated by PAs, with Ca2+ efflux becoming sustained in pea roots in the presence of Spm (Zepeda-Jazo et al., 2011; Pottosin et al., 2012), whereas in barley, the OH• and PA effects on Ca2+ pumping were roughly additive (Velarde-Buendía et al., 2012). PAs also potentiated the ROSIC-mediated K+ efflux (Zepeda-Jazo et al., 2011). This potentiation was much more pronounced in a salt-tolerant vs. salt-sensitive barley variety (Velarde-Buendía et al., 2012). In cereals such as barley and wheat, the magnitude of the ROS-induced K+ efflux correlates negatively with salt tolerance (Maksimović et al., 2013; Wang W. et al., 2018). However, ROS-induced K+ efflux by modified GORK channels can also result in a “metabolic switch” relocating more cell energy to stress defense (Demidchik, 2014; Shabala, 2017). A transient drop in the cytosolic K+ in a local region (e.g., root tip) per se could also serve as a stress signal (Shabala, 2017).

The γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) in plants is produced via decarboxylation of glutamate or by a two-step Put catabolization. Increased DAO expression in response to abiotic stresses (Shelp et al., 2012) may lead to increased GABA production. Upon heavy metal and hypoxia, GABA production is fed back, promoting the PA biosynthesis and reducing their catabolization (Wang et al., 2014; Seifikalhor et al., 2020). GABA inhibits the malate efflux from roots by a direct binding to anion transporter ALMT1 (Ramesh et al., 2015). GORK contains a conserved GABA-binding motif, and GABA induces K+ efflux via GORK (Adem et al., 2020). GABA over-accumulating Arabidopsis mutant displayed increased activity of the PM H+ ATPase, a better control of the membrane potential and K+ retention/reduced ROS-induced K+ efflux from roots, and lower Na+ uptake, conferring salt tolerance (Su et al., 2019). GABA provokes a hyperpolarization, via either inhibition of anion efflux via ALMT or stimulation of the H+ pumping; it reduces ROS-induced K+ efflux but increases ROS-induced Ca2+ efflux from barley roots (Shabala et al., 2014; Gilliham and Tyerman, 2016). Thus, GABA may antagonize the effects of ROS overproduction under stresses, which increase K+ efflux and Ca2+ uptake.

Polyamines and their catabolism also rapidly upturn NO signaling, which targets multiple ion transporters. These include activation of the PM H+-ATPase, inhibition (by direct nitrosylation) of GORK channels, activation of Ca2+ influx across the PM, and Ca2+ release from intracellular stores. The latter could lead to Ca2+-dependent activation of the slow anion and inhibition of inward-rectifying K+ currents, provoking stomata closure (Pottosin and Shabala, 2014; Seifikalhor et al., 2019).

Outlook

In contrast to Ca2+ and Mg2+, which act at a point, PAs with repeatedly space-distributed charges can form links between multiple binding anionic centers, which explains a higher binding affinity for longer polyamines in comparison to diamine Put, predicted by the docking analysis. Respective amino acids should be mutated to test whether they decrease the affinity of block by PAs and, if so, to verify whether this will be detrimental for plants’ performance under stress (e.g., salinity). In addition to pore block, long PA Spm likely interferes with cytosolic Ca2+ binding to the EF2 site (Figure 1). EF2 is critical for the AtTPC1 activation (Guo et al., 2016), whereas Ca2+ binding to EF1 likely has an allosteric effect, increasing Ca2+ affinity for EF2 (Demidchik et al., 2018). Spm binding along the EF2 loop would affect its mobility and Ca2+ affinity, thus potentially altering TPC1 gating.

There are several unresolved problems regarding PA effects on PM ion transporters. In plants, PAs affect two key PM ionotropic ATPases, Ca2+ and H+ pumps. Diverse and sometimes opposite effects on the H+-ATPase imply multiple and mostly indirect mechanisms. A rapid stimulation of Ca2+ pumping by PAs in barley and pea roots is worth to be explored in other plant species and in vitro studies with isolated Ca2+-ATPases. By analogy with their animal counterparts, glutamate receptors and cyclic nucleotide gated channels are plausible but unexplored targets for PAs in plants. In the latter case, in addition to direct effects, the signaling cascade involving PA catabolization–NO generation–activation of the adenylate cyclase-Ca2+ signal is worth to be explored (Jeandroz et al., 2013; Pottosin and Shabala, 2014). Overall, signaling by PAs needs to be considered in a close context with ROS, NO, and Ca2+ signaling.

Direct effects of free and conjugated PAs on individual ion transporters should be compared, and underexplored effects of cadaverine and thermospermine should be addressed. Also, our knowledge on PA traffic and subcellular compartmentalization remains fragmentary. Early studies suggested that the vacuolar PA concentration is lower than that in the cytosol (Pistocchi et al., 1987; DiTomaso et al., 1992). Taking into the account the dominant vacuolar volume, it implies that if one operates with an average tissue PA content, actual cytosolic and vacuolar PA concentrations are several times under- and overestimated, respectively.

Polyamines alleviate stress-induced suppression of photosynthesis in different ways, including a stabilization of the thylakoid ultrastructure, control of lipid composition, regulation of the expression, structure and oligomerization of photosynthetic membrane proteins, promotion of the chlorophyll biosynthesis, and improvement of the antioxidant activity (Hamdani et al., 2011; Hu et al., 2014; Li et al., 2015, 2018; Shu et al., 2015). However, to the best of our knowledge, the effects of PAs on ion transport across chloroplast membranes have not been addressed. Meanwhile, chloroplasts possess a variety of cation and K+-selective channels in the inner envelope and thylakoid membranes, which finely tune the photosynthesis (for a review, see Checchetto et al., 2013). No data are available on the effects of PAs on mitochondrial ion channels in plants. Plausible PA targets, based on published data on animal mitochondria, involve a mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter (MCU), controlling mitochondrial Ca2+ homeostasis, metabolism, and cell death (Yan et al., 2015 and references therein; Wagner et al., 2016), a mitochondrial transition pore (Cui et al., 2020), and an ATP- and ROS-sensitive mito KATP channel, whose activity decreases ΔΨ and damps mitochondrial ROS production under salinity and drought (Trono et al., 2015).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

IP, OD, and SS developed the concept. MO-A performed the docking analysis. IZ-J composed the table. IP and OD wrote the draft. All authors edited the final version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Adem G. D., Chen G., Shabala L., Chen Z. H., Shabala S. (2020). GORK channel: a master switch of plant metabolism? Trends Plant Sci. 25 434–445. 10.1016/j.tplants.2019.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad I., Mian A., Maathuis F. J. M. (2016). Overexpression of the rice AKT1 potassium channel affects potassium nutrition and rice drought tolerance. J. Exp. Bot. 67 2689–2698. 10.1093/jxb/erw103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcázar R., Altabella T., Marco F., Bortolotti C., Reymond M., Koncz C., et al. (2010). Polyamines: molecules with regulatory functions in plant abiotic stress tolerance. Planta 231 1237–1249. 10.1007/s00425-010-1130-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An Z. F., Li C. Y., Zhang L. X., Alva A. K. (2012). Role of polyamines and phospholipase D in maize (Zea mays L.) response to drought stress. S. Afr. J. Bot. 83 145–150. 10.1016/j.sajb.2012.08.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aslam R., Williams L. E., Bhatti M. F., Virk N. (2017). Genome-wide analysis of wheat calcium ATPases and potential role of selected ACAs and ECAs in calcium stress. BMC. Plant Biol. 17:174. 10.1186/s12870-017-1112-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behera S., Zhaolong X., Luoni L., Bonza M. C., Doccula F. G., De Michelis M. I., et al. (2018). Cellular Ca2 + signals generate defined pH signatures in plants. Plant Cell 30 2704–2719. 10.1105/tpc.18.00655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bihler H., Eing C., Hebeisen S., Roller A., Czempinski K., Bertl A. (2005). TPK1 is a vacuolar ion channel different from the slow-vacuolar cation channel. Plant Physiol. 139 417–424. 10.1104/pp.105.065599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobik K., Boutry M., Duby G. (2010). Activation of the plasma membrane H+-ATPase by acid stress. Plant Signal. Behav. 5 681–683. 10.4161/psb.5.6.11572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonales-Alatorre E., Pottosin I., Shabala L., Chen Z. H., Zeng F., Jacobsen S. E., et al. (2013). Differential activity of plasma and vacuolar membrane transporters contributes to genotypic differences in salinity tolerance in a halophyte species, Chenopodium quinoa. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14 9267–9285. 10.3390/ijms14059267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonza M. C., De Michelis M. I. (2011). The plant Ca2 + -ATPase repertoire: biochemical features and physiological functions. Plant Biol. (Stuttg) 13 421–430. 10.1111/j.1438-8677.2010.00405.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonza M. C., Luoni L., Olivari C., De Michelis M. I. (2016). “Plant type 2B Ca2 + -ATPases: the diversity of isoforms of the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana,” in Regulation of Ca2 + -ATPases,V-ATPases and F-ATPases. Advances in Biochemistry in Health and Disease, Vol. 14 eds Chakraborti s., Dhalla NS. (Cham: Springer: ) 10.1007/978-3-319-24780-9_13 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borrell A., Culianez-Macia F. A., Altabella T., Besford R. T., Flores D., Tiburcio A. F. (1995). Arginine decarboxylase is localized in chloroplasts. Plant Physiol. 109 771–776. 10.1104/pp.109.3.771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bose J., Babourina O., Ma Y., Zhou M., Shabala S., Rengel Z. (2015a). “Specificity of ion uptake and homeostasis maintenance during acid and aluminium stresses,” in Aluminum Stress Adaptation In Plants. Signaling and Communication in Plants, Vol. 24 eds Panda S., Baluška F. (Cham: Springer; ), 10.1007/978-3-319-19968-912 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bose J., Pottosin I., Shabala S. S., Palmgren M. G., Shabala S. (2011). Calcium efflux systems in stress signalling and adaptation in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2 1–17. 10.3389/fpls.2011.00085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bose J., Rodrigo-Moreno A., Lai D., Xie Y., Shen W., Shabala S. (2015b). Rapid regulation of the plasma membrane H+-ATPase activity is essential to salinity tolerance in two halophyte species, Atriplex lentiformis and Chenopodium quinoa. Ann. Bot. 115 481–494. 10.1093/aob/mcu219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brüggemann L. I., Pottosin I. I., Schönknecht G. (1998). Cytoplasmic polyamines block the fast activating vacuolar cation channel. Plant J. 16 101–106. 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00274.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brüggemann L. I., Pottosin I. I., Schönknecht G. (1999). Selectivity of the fast activating vacuolar cation channel. J. Exp. Bot. 505 873–876. 10.1093/jxb/50.335.873 12432039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buch-Pedersen M. J., Rudashevskaya E. L., Berner T. S., Venema K., Palmgren M. G. (2006). Potassium as an intrinsic uncoupler of the plasma membrane H+-ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 281 38285–38292. 10.1074/jbc.M604781200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdach Z., Siemieniuk A., Karcz W. (2020). Effect of auxin (IAA) on the fast vacuolar (FV) channels in red beet (Beta vulgaris L.) taproot vacuoles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21:4876. 10.3390/ijms21144876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdach Z., Siemieniuk A., Trela Z., Kurtyka R., Karcz W. (2018). Role of auxin (IAA) in the regulation of slow vacuolar (SV) channels and the volume of red beet taproot vacuoles. BMC Plant Biol. 18:102. 10.1186/s12870-018-1321-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai H., Guo J., Zhong Y., Hsu C. C., Zou C., Wang P., et al. (2020). The plasma-membrane polyamine transporter PUT3 is regulated by the Na+ /H+ antiporter SOS1 and protein kinase SOS2. New Phytol. 226 785–797. 10.1111/nph.16407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Checchetto V., Teardo E., Carraretto L., Formentin E., Bergantino E., Giacometti G. M., et al. (2013). Regulation of photosynthesis by ion channels in cyanobacteria and higher plants. Biophys. Chem. 182 51–57. 10.1016/j.bpc.2013.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z. H., Chen G., Dai F., Wang Y., Hills A., Ruan Y. L., et al. (2017). Molecular evolution of grass stomata. Trends Plant Sci. 22 124–139. 10.1016/j.tplants.2016.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chérel I., Gaillard I. (2019). The complex fine-tuning of K+ fluxes in plants in relation to osmotic and ionic abiotic stresses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20:715. 10.3390/ijms20030715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi W. G., Toyota M., Kim S. H., Hilleary R., Gilroy S. (2014). Salt stress-induced Ca2+ waves are associated with rapid, long-distance root-to-shoot signaling in plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111 6497–6502. 10.1073/pnas.1319955111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo R., Cerana R., Bagni N. (1992). Evidence for polyamine channels in protoplasts and vacuoles of Arabidopsis thaliana cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 182 1187–1192. 10.1016/0006-291x(92)91857-m [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corratgé-Faillie C., Ronzier E., Sanchez F., Prado K., Kim J. H., Lanciano S., et al. (2017). The Arabidopsis guard cell outward potassium channel GORK is regulated by CPK33. FEBS Lett. 591 1982–1992. 10.1002/1873-3468.12687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa A., Luoni L., Marrano C. A., Hashimoto K., Köster P., Giacometti S., et al. (2017). Ca2 + -dependent phosphoregulation of the plasma membrane Ca2 + -ATPase ACA8 modulates stimulus-induced calcium signatures. J. Exp. Bot. 68 3215–3230. 10.1093/jxb/erx162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui J., Pottosin I., Lamade E., Tcherkez G. (2020). What is the role of putrescine accumulated under potassium deficiency? Plant Cell Environ. 43 1331–1347. 10.1111/pce.13740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuin T. A., Dreyer I., Michard E. (2018). The role of potassium channels in Arabidopsis thaliana long distance electrical signalling: AKT2 modulates tissue excitability while GORK shapes action potentials. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19:926. 10.3390/ijms19040926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Luca A., Pardo J. M., Leidi E. O. (2018). Pleiotropic effects of enhancing vacuolar K/H exchange in tomato. Physiol. Plant 163 88–102. 10.1111/ppl.12656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demidchik V. (2014). Mechanisms and physiological roles of K+ efflux from root cells. J. Plant Physiol. 171 696–707. 10.1016/j.jplph.2014.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demidchik V. (2018). ROS-Activated ion channels in plants: biophysical characteristics, physiological functions and molecular nature. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19:1263. 10.3390/ijms19041263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demidchik V., Cuin T. A., Svistunenko D., Smith S. J., Miller A. J., Shabala S., et al. (2010). Arabidopsis root K+-efflux conductance activated by hydroxyl radicals: single-channel properties, genetic basis and involvement in stress-induced cell death. J. Cell Sci. 123 1468–1479. 10.1242/jcs.064352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demidchik V., Maathuis F. J. M. (2007). Physiological roles of nonselective cation channels in plants: from salt stress to signalling and development. New Phytol. 175 387–404. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02128.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demidchik V., Shabala S., Isayenkov S., Cuin T. A., Pottosin I. (2018). Calcium transport across plant membranes: mechanisms and functions. New Phytol. 220 49–69. 10.1111/nph.15266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demidchik V., Tester M. (2002). Sodium fluxes through non-selective cation channels in the plasma membrane of protoplasts from Arabidopsis thaliana roots. Plant Physiol. 128 379–387. 10.1104/pp.010524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiTomaso J. M., Hart J. J., Kochian L. V. (1992). Transport kinetics and metabolism of exogenously applied putrescine in roots of intact maize seedlings. Plant Physiol. 98 611–620. 10.1104/pp.98.2.611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrovinskaya O. R., Muñiz J., Pottosin I. I. (1999a). Asymmetric block of the plant vacuolar Ca2+-permeable channel by organic cations. Eur. Biophys. J. 28 552–563. 10.1007/s002490050237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrovinskaya O. R., Muñiz J., Pottosin I. I. (1999b). Inhibition of vacuolar ion channels by polyamines. J. Membr. Biol. 167 127–140. 10.1007/s002329900477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreyer I., Gomez-Porras J. L., Riedelsberger J. (2017). The potassium battery: a mobile energy source for transport processes in plant vascular tissues. New Phytol. 216 1049–1053. 10.1111/nph.14667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du H., Zhou X., Yang Q., Liu H., Kurtenbach R. (2015). Changes in H+-ATPase activity and conjugated polyamine contents in plasma membrane purified from developing wheat embryos under short-time drought stress. Plant Growth Reg. 75 1–10. 10.1007/s10725-014-9925-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duby G., Boutry M. (2009). The plant plasma membrane proton pump ATPase: a highly regulated P-type ATPase with multiple physiological roles. Pflügers Arch. 457 645–655. 10.1007/s00424-008-0457-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essah P. A., Davenport R., Tester M. (2003). Sodium influx and accumulation in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 133 307–318. 10.1104/pp.103.022178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans M. J., Choi W. G., Gilroy S., Morris R. J. (2016). A ROS-assisted calcium wave dependent on the AtRBOHD NADPH oxidase and TPC1 cation channel propagates the systemic response to salt stress. Plant Physiol. 171 1771–1784. 10.1104/pp.16.00215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falhof J., Pedersen J. T., Fuglsang A. T., Palmgren M. (2016). Plasma membrane H+-ATPase regulation in the center of plant physiology. Mol. Plant 9 323–337. 10.1016/j.molp.2015.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng X., Liu W., Cao F., Wang Y., Zhang G., Chen Z.-H., et al. (2020). Overexpression of HvAKT1 improves barley drought tolerance by regulating root ion homeostasis and ROS and NO signaling. J. Exp. Bot. 71:eraa354. 10.1093/jxb/eraa354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foreman J., Demidchik V., Bothwell J. H. F., Mylona P., Miedema H., Torres M. A., et al. (2003). Reactive oxygen species produced by NADPH oxidase regulate plant cell growth. Nature 422 442–446. 10.1038/nature01485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromm J., Meyer A. J., Weisenseel M. H. (1997). Growth, membrane potential and endogenous ion currents of willow (Salix viminalis) roots are all affected by abscisic acid and spermine. Physiol. Plant 99 529–537. 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1997.tb05353.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fuglsang A. T., Guo Y., Cuin T. A., Qiu Q., Song C., Kristiansen K. A., et al. (2007). Arabidopsis protein kinase PKS5 inhibits the plasma membrane H+ -ATPase by preventing interaction with 14-3-3 protein. Plant Cell 19 1617–1634. 10.1105/tpc.105.035626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita M., Shinozaki K. (2015). “Polyamine transport systems in plants,” in Polyamines, eds Kusano T., Suzuki H. (Tokyo: Springer; ), 10.1007/978-4-431-55212-315 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- García-Bossi J., Kumar K., Barberini M. L., Díaz-Domínguez G., Rondón-Guerrero Y., del C., et al. (2020). The role of P-type IIA and P-type IIB Ca2 + -ATPases in plant development and growth. J. Exp. Bot. 71 1239–1248. 10.1093/jxb/erz521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Mata C., Wang J., Gajdanowicz P., Gonzalez W., Hills A., Donald N., et al. (2010). A minimal cysteine motif required to activate the SKOR K+ channel of Arabidopsis by the reactive oxygen species H2O2. Int. J. Biol. Chem. 285 29286–29294. 10.1074/jbc.M110.141176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garufi A., Visconti S., Camoni L., Aducci P. (2007). Polyamines as physiological regulators of 14-3-3 interaction with the plant plasma membrane H+-ATPase. Plant Cell Physiol. 48 434–440. 10.1093/pcp/pcm010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaymard F., Pilot G., Lacombe B., Bouchez D., Bruneau D., Boucherez J., et al. (1998). Identification and disruption of a plant Shaker-like outward channel involved in K+ release into the xylem sap. Cell 94 647–655. 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81606-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilliham M., Tyerman S. D. (2016). Linking metabolism to membrane signaling: the GABA-malate connection. Trends Plant Sci. 21 295–301. 10.1016/j.tplants.2015.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gjetting S. K., Mahmood K., Shabala L., Kristensen A., Shabala S., Palmgren M., et al. (2020). Evidence for multiple receptors mediating RALF-triggered Ca2+ signaling and proton pump inhibition. Plant J. 104 433–446. 10.1111/tpj.14935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobert A., Isayenkov S., Voelker C., Czempinski K., Maathuis F. J. M. (2007). The two-pore channel TPK1 gene encodes the vacuolar K+ conductance and plays a role in K+ homeostasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 10726–10731. 10.1073/pnas.0702595104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunwald Y., Wigoda N., Sade N., Yaaran A., Torne T., Chaka-Gosa S., et al. (2017). Arabidopsis leaf hydraulic conductance is regulated by xylem-sap pH, controlled, in turn, by a P-type H+-ATPase of vascular bundle sheath cells. bioRxiv [Preprint] 10.1101/234286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo D., Lu Z. (2000). Mechanism of cGMP-gated channel block by intracellular polyamines. J. Gen. Physiol. 115 783–798. 10.1085/jgp.115.6.783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J., Zeng W., Chen Q., Lee C., Chen L., Yang Y., et al. (2016). Structure of the voltage-gated two-pore channel TPC1 from Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature 531 196–201. 10.1038/nature16446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta K., Sengupta A., Chakraborty M., Gupta B. (2016). Hydrogen peroxide and polyamines act as double edged swords in plant abiotic stress responses. Front. Plant Sci. 7:1343. 10.3389/fpls.2016.01343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamamoto S., Marui J., Matsuoka K., Higashi K., Igarashi K., Nakagawa T., et al. (2008). Characterization of a tobacco TPK-type K+ channel as a novel tonoplast K+ channel using yeast tonoplasts. J. Biol. Chem. 283 1911–1920. 10.1074/jbc.M708213200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamdani S., Yaakoubi H., Carpentier R. (2011). Polyamines interaction with thylakoid proteins during stress. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 104 314–319. 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2011.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haruta M., Sussman M. R. (2012). The effect of a genetically reduced plasma membrane protonmotive force on vegetative growth of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 158 1158–1171. 10.1104/pp.111.189167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedrich R., Marten I. (2011). TPC1 – SV Channels gain shape. Mol. Plant 4 428–441. 10.1093/mp/ssr017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedrich R., Mueller T. D., Becker D., Marten I. (2018). Structure and function of TPC1 vacuole SV channel gains shape. Mol. Plant 11 764–775. 10.1016/j.molp.2018.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilleary R., Paez-Valencia J., Vens C., Toyota M., Palmgren M., Gilroy S. (2020). Tonoplast-localized Ca2 + pumps regulate Ca2 + signals during pattern-triggered immunity in Arabidopsis thaliana. PNAS 117 18849–18857. 10.1073/pnas.2004183117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann R. D., Olsen L. I., Ezike C. V., Pedersen J. T., Manstretta R., López-Marqués R. L., et al. (2019). Roles of plasma membrane proton ATPases AHA2 and AHA7 in normal growth of roots and root hairs in Arabidopsis thaliana. Physiol Plant 166 848–861. 10.1111/ppl.12842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann R. D., Portes M. T., Olsen L. I., Damineli D. S. C., Hayashi M., Nunes C. O., et al. (2020). Plasma membrane H+-ATPases sustain pollen tube growth and fertilization. Nat. Commun. 11:2395. 10.1038/s41467-020-16253-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosy E., Vavasseur A., Mouline K., Dreyer I., Gaymard F., Poree F., et al. (2003). The Arabidopsis outward K+ channel GORK is involved in regulation of stomatal movements and plant transpiration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100 5549–5554. 10.1073/pnas.0733970100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L., Xiang L., Zhang L., Zhou X., Zou Z., Hu X. (2014). The photoprotective role of spermidine in tomato seedlings under salinity alkalinity stress. PLoS One 9:e110855. 10.1371/journal.pone.0110855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C. J., Moczydlowski E. (2001). Cytoplasmic polyamines as permeant blockers and modulators of the voltage-gated sodium channel. Biophys. J. 80 1262–1279. 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76102-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igarashi K., Kashiwagi K., Kobayashi H., Ohnishi R., Kakegawa T., Nagasu A., et al. (1989). Effect of polyamines on mitochondrial F1-ATPase catalyzed reactions. J. Biochem. 106 294–298. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a122847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue S. I., Kinoshita T. (2017). Blue light regulation of stomatal opening and the plasma membrane H+-ATPase. Plant Physiol. 174 531–538. 10.1104/pp.17.00166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ioannidis N. E., Cruz J. A., Kotzabasis K., Kramer D. M. (2012). Evidence that putrescine modulates the higher plant photosynthetic proton circuit. PLoS One 7:e29864. 10.1371/journal.pone.0029864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ioannidis N. E., Sfichi L., Kotzabasis K. (2006). Putrescine stimulates chemiosmotic ATP synthesis. BBA Bioenergetics 1757 821–828. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.05.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janicka M. G., Reda M. G., Czy Ewska K., Kaba A. K. (2018). Involvement of signalling molecules NO, H2O2 and H2S in modification of plasma membrane proton pump in cucumber roots subjected to salt or low temperature stress. Funct. Plant Biol. 45 428–439. 10.1071/FP17095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janicka-Russak M., Kabała K., Młodziñska E., Kłobus G. (2010). The role of polyamines in the regulation of the plasma membrane and the tonoplast proton pumps under salt stress. J. Plant Physiol. 167 261–269. 10.1016/j.jplph.2009.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaślan D., Dreyer I., Lu J., O’Malley R., Dindas J., Marten I., et al. (2019). Voltage-dependent gating of SV channel TPC1 confers vacuole excitability. Nat. Commun. 10:2659. 10.1038/s41467-019-10599-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeandroz S., Lamotte O., Astier J., Rasul S., Trapet P., Besson-Bard A., et al. (2013). There’s more to the picture than meets the eye: nitric oxide cross talk with Ca2+ signaling. Plant Physiol. 163 459–470. 10.1104/pp.113.220624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabała K., Kłobus G. (2005). Plant Ca2 + -ATPases. Acta Physiol. Plant. 27 559–574. 10.1007/s11738-005-0062-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keisham M., Mukherjee S., Bhatla S. C. (2018). Mechanisms of sodium transport in plants-progresses and challenges. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19:647. 10.3390/ijms19030647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiep V., Vadassery J., Lattke J., Maaß J. P., Boland W., Peiter E., et al. (2015). Systemic cytosolic Ca2+ elevation is activated upon wounding and herbivory in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 207 996–1004. 10.1111/nph.13493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koselski M., Wasko P., Kupisz K., Trebacz K. (2019). Cold- and menthol-evoked membrane potential changes in the moss Physcomitrella patens: influence of ion channel inhibitors and phytohormones. Physiol. Plant 167 433–446. 10.1111/ppl.12918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger S., Giavalisco P., Krall L., Steinhauser M. C., Büssis D., Usadel B., et al. (2011). A topological map of the compartmentalized Arabidopsis thaliana leaf metabolome. PLoS One 6:e17806. 10.1371/journal.pone.0017806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari A., Chételat A., Nguyen C. T., Farmer E. E. (2019). Arabidopsis H+-ATPase AHA1 controls slow wave potential duration and wound-response jasmonate pathway activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116 20226–20231. 10.1073/pnas.1907379116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak J. M., Murata Y., Baizabal-Aguirre V. M., Merrill J., Wang M., Kemper A., et al. (2001). Dominant negative guard cell K+ channel mutants reduce inward-rectifying K+ currents and light-induced stomatal opening in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 127 473–485. 10.1104/pp.010428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenglet A., Jaślan D., Toyota M., Mueller M., Müller T., Schönknecht G., et al. (2017). Control of basal jasmonate signalling and defence through modulation of intracellular cation flux capacity. New Phytol. 216 1161–1169. 10.1111/nph.14754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Hu L., Zhang L., Pan X., Hu X. (2015). Exogenous spermidine is enhancing tomato tolerance to salinity-alkalinity stress by regulating chloroplast antioxidant system and chlorophyll metabolism. BMC Plant Biol. 15:303. 10.1186/s12870-015-0699-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Gu W., Li J., Li C., Xie T., Qu D., et al. (2018). Exogenously applied spermidine alleviates photosynthetic inhibition under drought stress in maize (Zea mays L.) seedlings associated with changes in endogenous polyamines and phytohormones. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 129 35–55. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2018.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H. P., Dong B. H., Zhang Y. Y., Liu Z. P., Liu Y. L. (2004). Relationship between osmotic stress and the levels of free, conjugated, and bound polyamines in leaves of wheat seedlings. Plant Sci. 166 1261–1267. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2003.12.039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H. P., Yu B. J., Zhang W. H., Liu Y. L. (2005). Effect of osmotic stress on the activity of H+-ATPase and the levels of covalently and noncovalently conjugated polyamines in plasma membrane preparation from wheat seedling roots. Plant Sci. 168 1599–1607. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2005.01.024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Yu B. J., Liu Y. L. (2006). Effects of spermidine and spermine levels on salt tolerance associated with tonoplast H+-ATPase and H+-PPase activities in barley roots. Plant Growth Regul. 49 119–126. 10.1007/s10725-006-9001-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu K., Fu H., Bei Q., Luan S. (2000). Inward potassium channel in guard cells as a target for polyamine regulation of stomatal movements. Plant Physiol. 124 1315–1325. 10.1104/pp.124.3.1315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M. Y., Sun J., Wang K. Y., Liu D., Li Z. Y., Zhang J. (2014). Spermidine enhances waterlogging tolerance via regulation of antioxidant defense, heat shock protein expression and plasma membrane H+-ATPase activity in Zea mays. J. Agro. Crop Sci. 200 199–211. 10.1111/jac.12058 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maathuis F. J. (2011). Vacuolar two-pore K+ channels act as vacuolar osmosensors. New Phytol. 191 84–91. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03664.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maksimović J. D., Zhang J., Zeng F., Živanović B. D., Shabala L., Zhou M., et al. (2013). Linking oxidative and salinity stress tolerance in barley: can root antioxidant enzyme activity be used as a measure of stress tolerance? Plant Soil 365 141–155. 10.1007/s11104-012-1366-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marina M., Maiale S. J., Rossi F. R., Romero M. F., Rivas E. I., Gárriz A., et al. (2008). Apoplastic polyamine oxidation plays different roles in local responses of tobacco to infection by the necrotrophic fungus Sclerotinia sclerotiorum and the biotrophic bacterium Pseudomonas viridiflava. Plant Physiol. 147 2164–2178. 10.1104/pp.108.122614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marty F. (1999). Plant vacuoles. Plant Cell 11 587–599. 10.1105/tpc.11.4.587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meksuriyen D., Fukuchi-Shimogori T., Tomitori H., Kashiwagi K., Toida T., Imanari T., et al. (1998). Formation of a complex containing ATP, Mg2+, and spermine. Structural evidence and biological significance. J. Biol. Chem. 273 30939–30944. 10.1074/jbc.273.47.30939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miśkiewicz J., Trela Z., Burdach Z., Karcz W., Balińska-Miśkiewicz W. (2020). Long range correlations of the ion current in SV channels. Met3PbCl influence study. PLoS One 15:e0229433. 10.1371/journal.pone.0229433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moschou P. N., Paschalidis K. A., Roubelakis-Angelakis K. A. (2008). Plant polyamine catabolism: the state of the art. Plant Signal. Behav. 3 1061–1066. 10.4161/psb.3.12.7172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moschou P. N., Sarris P. F., Skandalis N., Andriopoulou A. H., Paschalidis K. A., Panopoulos N. J., et al. (2009). Engineered polyamine catabolism preinduces tolerance of tobacco to bacteria and oomycetes. Plant Physiol. 149 1970–1981. 10.1104/pp.108.134932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moschou P. N., Wu J., Cona A., Tavladoraki P., Angelini R., Roubelakis-Angelakis K. A. (2012). The polyamines and their catabolic products are significant players in the turnover of nitrogenous molecules in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 63 5003–5015. 10.1093/jxb/ers202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozawa R., Bertea C. M., Foti M., Narayana R., Arimura G., Muroi A., et al. (2010). Polyamines and jasmonic acid induce plasma membrane potential variations in lima bean. Plant Signal. Behav. 5 308–310. 10.4161/psb.5.3.10848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pál M., Szalai G., Janda T. (2015). Speculation: polyamines are important in abiotic stress signaling. Plant Sci. 237 16–23. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2015.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmgren M., Morsomme P. (2018). The plasma membrane H+-ATPase, a simple polypeptide with a long history. Yeast 36 201–210. 10.1002/yea.3365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandolfi C., Pottosin I., Cuin T., Mancuso S., Shabala S. (2010). Specificity of polyamine effects on NaCl-induced ion flux kinetics and salt stress amelioration in plants. Plant Cell Physiol. 51 422–434. 10.1093/pcp/pcq007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paschalidis K., Tsaniklidis G., Wang B. Q., Delis C., Trantas E., Loulakakis K., et al. (2019). The interplay among polyamines and nitrogen in plant stress responses. Plants (Basel) 8:315. 10.3390/plants8090315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei Z.-M., Murata Y., Benning G., Thomine S. Â, Klüsener B., Gethyn J., et al. (2000). Calcium channels activated by hydrogen peroxide mediate abscisic acid signalling in guard cells. Nature 406 731–734. 10.1038/35021067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peiter E. (2011). The plant vacuole: emitter and receiver of calcium signals. Cell Calcium 50 120–128. 10.1016/j.ceca.2011.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peiter E., Maathuis F., Mills L., Knight H., Pelloux J., Hetherington A. M., et al. (2005). The vacuolar Ca2+-activated channel TPC1 regulates germination and stomatal movement. Nature 434 404–408. 10.1038/nature03381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peter H. W., Pinheiro M. R., Silva-Lima M. (1981). Regulation of the F-ATPase from mitochondria of Vigna sinensis (L.) Savi cv. Pitiuba by spermine, spermidine, putrescine, Mg2+, Na+, and K+. Can. J. Biochem. 59 60–66. 10.1139/o81-009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pistocchi R., Bagni N., Creus J. A. (1987). Polyamine uptake in carrot cell cultures. Plant Physiol. 84 374–380. 10.1104/pp.84.2.374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pottosin I. (2015). “Polyamine action on plant ion channels and pumps,” in Polyamines, eds Kusano T., Suzuki H. (Tokyo: Springer; ), 10.1007/978-4-431-55212-319 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pottosin I., Dobrovinskaya O. (2014). Non-selective cation channels in plasma and vacuolar membranes and their contribution to K+ transport. J. Plant Physiol. 171 732–742. 10.1016/j.jplph.2013.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pottosin I., Dobrovinskaya O. (2018). Two-pore cation (TPC) channel: not a shorthanded one. Funct. Plant Biol. 45 83–92. 10.1071/FP16338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pottosin I., Shabala S. (2014). Polyamines control of cation transport across plant membranes: implications for ion homeostasis and abiotic stress signaling. Front. Plant Sci. 5:154. 10.3389/fpls.2014.00154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pottosin I., Velarde-Buendía A. M., Bose J., Fuglsang A. T., Shabala S. (2014a). Polyamines cause plasma membrane depolarization, activate Ca2+-, and modulate H+-ATPase pump activity in pea roots. J. Exp. Bot. 65 2463–2472. 10.1093/jxb/eru133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pottosin I., Velarde-Buendía A. M., Bose J., Zepeda -Jazo I., Shabala S., Dobrovinskaya O. (2014b). Cross-talk between reactive oxygen species and polyamines in regulation of ion transport across the plasma membrane: implications for plant adaptive responses. J. Exp. Bot. 65 1271–1283. 10.1093/jxb/ert423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pottosin I., Velarde-Buendia A. M., Zepeda-Jazo I., Dobrovinskaya O., Shabala S. (2012). Synergism between polyamines and ROS in the induction of Ca2+ and K+ fluxes in roots. Plant Signal. Behav. 7 1084–1087. 10.4161/psb.21185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pottosin I., Zepeda-Jazo I. (2018). Powering the plasma membrane Ca2+-ROS self-amplifying loop. J. Exp. Bot. 69 3317–3320. 10.1093/jxb/ery179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pottosin I., Zepeda-Jazo I., Bose J., Shabala S. (2018). An anion conductance, the essential component of the hydroxyl-radical-induced ion current in plant roots. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19:897. 10.3390/ijms19030897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pottosin I. I., Martínez-Estévez M. (2003). Regulation of the fast vacuolar channel by cytosolic and vacuolar potassium. Biophys. J. 84 977–986. 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74914-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pottosin I. I., Martínez-Estévez M., Dobrovinskaya O. R., Muñiz J. (2003). Potassium-selective channel in the red beet vacuolar membrane. J. Exp. Bot. 54 663–667. 10.1093/jxb/erg067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pottosin I. I., Muñiz J. (2002). Higher plant vacuolar ionic transport in the cellular context. Acta Bot. Mex. 60 37–77. 10.21829/abm60.2002.902 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raddatz N., Morales de Los Ríos L., Lindahl M., Quintero F. J., Pardo J. M. (2020). Coordinated transport of nitrate, potassium, and sodium. Front. Plant Sci. 11:247. 10.3389/fpls.2020.00247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragel P., Raddatz N., Leidi E. O., Quintero F. J., Pardo J. M. (2019). Regulation of K+ nutrition in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 10:281. 10.3389/fpls.2019.00281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramesh S., Tyerman S., Xu B., Bose J., Kaur S., Conn V., et al. (2015). GABA signalling modulates plant growth by directly regulating the activity of plant-specific anion transporters. Nat. Commun. 6:7879. 10.1038/ncomms8879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reggiani R., Zaina S., Bertani A. (1992). Plasmalemma ATPase in rice coleoptiles: stimulation by putrescine and polyamines. Phytochemistry 31 417–419. 10.1016/0031-9422(92)90009-F [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigo-Moreno A., Andrés-Colás N., Poschenrieder C., Gunsé B., Peñarrubia L., Shabala S. (2013). Calcium- and potassium-permeable plasma membrane transporters are activated by copper in Arabidopsis root tips: linking copper transport with cytosolic hydroxyl radical production. Plant Cell Environ. 36 844–855. 10.1111/pce.12020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez A. A., Maiale S. J., Menédez A. B., Ruiz O. A. (2009). Polyamine oxidase activity contributes to sustain maize leaf elongation under saline stress. J. Exp. Bot. 60 4249–4262. 10.1093/jxb/erp256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy P., Niyogi K., Sengupta D. N., Ghosh B. (2005). Spermidine treatment to rice seedlings recovers salinity stress-induced damage of plasma membrane and PM-bound H+-ATPase in salt- tolerant and salt-sensitive rice cultivars. Plant Sci. 168 583–591. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2004.08.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio F., Nieves-Cordones M., Horie T., Shabala S. (2020). Doing ‘business as usual’ comes with a cost: evaluating energy cost of maintaining plant intracellular K+ homeostasis under saline conditions. New Phytol. 225 1097–1104. 10.1111/nph.15852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiøtt M., Palmgren M. G. (2005). Two plant Ca2 + pumps expressed in stomatal guard cells show opposite expression patterns during cold stress. Physiol. Plant 124 278–283. 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2005.00512.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seifikalhor M., Aliniaeifard S., Bernard F., Mehdi S., Mojgan L., Batool H., et al. (2020). γ-Aminobutyric acid confers cadmium tolerance in maize plants by concerted regulation of polyamine metabolism and antioxidant defense systems. Sci. Rep. 10:3356. 10.1038/s41598-020-59592-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifikalhor M., Aliniaeifard S., Shomali A., Azad N., Hassani B., Lastochkinaet O., et al. (2019). Calcium signaling and salt tolerance are diversely entwined in plants. Plant Signal. Behav. 14:11. 10.1080/15592324.2019.1665455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shabala S. (2017). Signalling by potassium: another second messenger to add to the list? J. Exp. Bot. 68 4003–4007. 10.1093/jxb/erx238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shabala S., Chen G., Chen Z. -H., Pottosin I. (2020). The energy cost of the tonoplast futile sodium leak. New Phytol. 225 1105–1110. 10.1111/nph.15758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shabala S., Cuin T. A. (2008). Potassium transport and plant salt tolerance. Physiol. Plant 133 651–669. 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2007.01008.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shabala S., Cuin T. A., Pottosin I. I. (2007a). Polyamines prevent NaCl-induced K+ efflux from pea mesophyll by blocking non-selective cation channels. FEBS Lett. 581 1993–1999. 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.04.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shabala S., Cuin T. A., Prismall L., Nemchinov L. G. (2007b). Expression of animal CED-9 anti-apoptotic gene in tobacco modifies plasma membrane ion fluxes in response to salinity and oxidative stress. Planta 227 189–197. 10.1007/s00425-007-0606-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shabala S., Shabala L., Barcelo J., Poschenrieder C. (2014). Membrane transporters mediating root signalling and adaptive responses to oxygen deprivation and soil flooding. Plant Cell Environ. 37 2216–2233. 10.1111/pce.12339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma T., Dreyer I., Riedelsberger J. (2013). The role of K+ channels in uptake and redistribution of potassium in the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Front. Plant Sci. 4:224. 10.3389/fpls.2013.00224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelp B. J., Bozzo G. G., Trobacher C. P., Zarei A., Deyman K. L., Brikis C. J. (2012). Hypothesis/review: contribution of putrescine to 4-aminobutyrate (GABA) production in response to abiotic stress. Plant Sci. 19 130–135. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2012.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu S., Yuan Y., Chen J., Sun J., Zhang W., Tang Y., et al. (2015). The role of putrescine in the regulation of proteins and fatty acids of thylakoid membranes under salt stress. Sci. Rep. 5:14390. 10.1038/srep14390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava S. K., Rajbabu P. (1983). Effect of amines and guanidines on ATPase from maize scutellum. Phytochemistry 22 2375–2679. 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)97671-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Su N., Wu Q., Chen J., Shabala L., Mithöfer A., Wang H., et al. (2019). GABA operates upstream of H+-ATPase and improves salinity tolerance in Arabidopsis by enabling cytosolic K+ retention and Na+ exclusion. J. Exp. Bot. 70 6349–6361. 10.1093/jxb/erz367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudha G., Ravishankar G. A. (2003). Influence of putrescine on anthocyanin production in callus cultures of Daucus carota mediated through calcium ATPase. Acta Physiol. Plant 25 69–75. 10.1007/s11738-003-0038-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suh B. C., Hille B. (2008). PIP2 is a necessary cofactor for ion channel function: how and why? Annu. Rev. Biophys. 37 175–195. 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C., Liu Y. L., Zhang W. H. (2002). Mechanism of the effect of polyamines on the activity of tonoplasts of barley roots under salt stress. Acta Bot. Sin. 44 1167–1172. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T., Kakehi J. (2010). Polyamines: ubiquitous polycations with unique roles in growth and stress responses. Ann. Bot. 105 1–6. 10.1093/aob/mcp259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda S., Gapper C., Kaya H., Bell E., Kuchitsu K., Dolan L. (2008). Local positive feedback regulation determines cell shape in root hair cells. Science 319 1241–1244. 10.1126/science.1152505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang R., Zhao F., Yang Y., Wang C., Li K., Kleist T. J., et al. (2020). A calcium signalling network activates vacuolar K+ remobilization to enable plant adaptation to low-K environments. Nat. Plants 6 384–393. 10.1038/s41477-020-0621-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang W., Newton R. J. (2005). Polyamines reduce salt-induced oxidative damage by increasing the activities of antioxidant enzymes and decreasing lipid peroxidation in Virginia pine. Plant Growth Reg. 46 31–43. 10.1007/s10725-005-6395-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tavladoraki P., Cona A., Federico R., Tempera G., Viceconte N., Saccoccio S., et al. (2012). Polyamine catabolism: target for antiproliferative therapies in animals and stress tolerance strategies in plants. Amino Acids 42 411–426. 10.1007/s00726-011-1012-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikhonova L. I., Pottosin I. I., Dietz K. J., Schönknecht G. (1997). Fast-activating cation channel in barley mesophyll vacuoles. Inhibition by calcium. Plant J. 11 1059–1070. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1997.11051059.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trono D., Laus M. N., Soccio M., Alfarano M., Pastore D. (2015). Modulation of potassium channel activity in the balance of ROS and ATP production by durum wheat mitochondria-An amazing defense tool against hyperosmotic stress. Front. Plant Sci. 6:1072. 10.3389/fpls.2015.01072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velarde-Buendía A. M., Shabala S., Cvikrova M., Dobrovinskaya O., Pottosin I. (2012). Salt-sensitive and salt-tolerant barley varieties differ in the extent of potentiation of the ROS-induced K+ efflux by polyamines. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 61 18–23. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2012.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner S., De Bortoli S., Schwarzländer M., Szabò I. (2016). Regulation of mitochondrial calcium in plants versus animals. J. Exp. Bot. 67 3809–3829. 10.1093/jxb/erw100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Fan L., Gao H., Wu X., Li J., Lv G., et al. (2014). Polyamine biosynthesis and degradation are modulated by exogenous gamma-aminobutyric acid in root-zone hypoxia-stressed melon roots. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 82 17–26. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2014.04.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F., Chen Z. H., Shabala S. (2017). Hypoxia sensing in plants: on a quest for ion channels as putative oxygen sensors. Plant Cell Physiol. 58 1126–1142. 10.1093/pcp/pcx079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Tian F., Hao Q., Han Y., Li Q., Wang X., et al. (2018). Improved salt tolerance in a wheat stay-green mutant tasg1. Acta Physiol. Plant 40:39 10.1007/s11738-018-2617-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Blatt M. R., Chen Z.-H. (2018). “Ion transport at the plant plasma membrane,” in eLS, (Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.), 10.1002/9780470015902.a0001307.pub3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Wu W. H. (2013). Potassium transport and signaling in higher plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 64 451–476. 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050312-120153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward J. M., Schroeder J. I. (1994). Calcium-activated K+ channels and calcium-induced calcium release by slow vacuolar ion channels in guard cell vacuoles implicated in the control of stomatal closure. Plant Cell 6 669–683. 10.1105/tpc.6.5.669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wherrett T., Shabala S., Pottosin I. (2005). Different properties of SV channels in root vacuoles from near isogenic Al-tolerant and Al-sensitive wheat cultivars. FEBS Lett. 579 6890–6894. 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.11.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams K. (1997). Interactions of polyamines with ion channels. Biochem. J. 325 289–297. 10.1042/bj3250289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J., Shang Z., Wu J., Jiang X., Moschou P. N., Sun W., et al. (2010). Spermidine oxidase-derived H2O2 regulates pollen plasma membrane hyperpolarization-activated Ca2+-permeable channels and pollen tube growth. Plant J. 63 1042–1053. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04301.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L. B., Holtkamp F., Wairich A., Frei M. (2019). Potassium ion channel gene OsAKT1 affects iron translocation in rice plants exposed to iron toxicity. Front. Plant Sci. 10:579. 10.3389/fpls.2019.00579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X., Shu S., Wang Y., Yuan R., Guo S. (2019). Exogenous putrescine alleviates photoinhibition caused by salt stress through cooperation with cyclic electron flow in cucumber. Photosynth. Res. 141 303–314. 10.1007/s11120-019-00631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie L. H., John S. A., Ribalet B., Weiss J. N. (2005). Long polyamines act as cofactors in PIP2 activation of inward rectifier potassium (Kir2.1) channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 126 541–549. 10.1085/jgp.200509380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W., Jia L., Baluška F., Ding G., Shi W., Ye N., et al. (2012). PIN2 is required for the adaptation of Arabidopsis roots to alkaline stress by modulating proton secretion. J. Exp. Bot. 63 6105–6114. 10.1093/jxb/ers259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W., Jia L., Shi W., Liang J., Zhou F., Li Q., et al. (2013). Abscisic acid accumulation modulates auxin transport in the root tip to enhance proton secretion for maintaining root growth under moderate water stress. New Phytol. 197 139–150. 10.1111/nph.12004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi S., Shimazaki K. (2017). Determination of H+-ATPase activity in Arabidopsis guard cell protoplasts through H+-pumping measurement and H+-ATPase quantification. Bio protocol 7:e2653 10.21769/BioProtoc.2653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi S., Takemiya A., Sakamoto T., Kurata T., Tsutsumi T., Kinoshita T., et al. (2016). The plasma membrane H+-ATPase AHA1 plays a major role in stomatal opening in response to blue light. Plant Physiol. 171 2731–2743. 10.1104/pp.16.01581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan H., Zhang D., Hao S., Li K., Hang C. H. (2015). Role of mitochondrial calcium uniporter in early brain injury after experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage. Mol. Neurobiol. 52 1637–1647. 10.1007/s12035-014-8942-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang D. L., Shi Z., Bao Y., Yan J., Yang Z., Yu H., et al. (2017). Calcium pumps and interacting BON1 protein modulate calcium signature, stomatal closure, and plant immunity. Plant Physiol. 175 424–437. 10.1104/pp.17.00495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Wu Y., Ma L., Yang Z., Dong Q., Li Q., et al. (2019). The Ca2+ sensor SCaBP3/CBL7 modulates plasma membrane H+-ATPase activity and promotes alkali tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 31 1367–1384. 10.1105/tpc.18.00568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoda H., Hiroi Y., Sano H. (2006). Polyamine oxidase is one of the key elements for oxidative burst to induce programmed cell death in tobacco cultured cells. Plant Physiol. 142 193–206. 10.1104/pp.106.080515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H., Yan J., Du X., Hua J. (2018). Overlapping and differential roles of plasma membrane calcium ATPases in Arabidopsis growth and environmental responses. J. Exp. Bot. 69 2693–2703. 10.1093/jxb/ery073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarza X., Shabala L., Fujita M., Shabala S., Haring M. A., Tiburcio A. F., et al. (2019). Extracellular spermine triggers a rapid intracellular phosphatidic acid response in Arabidopsis, involving PLDδ activation and stimulating ion flux. Front. Plant Sci. 10:601. 10.3389/fpls.2019.00601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]