Abstract

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has produced considerable morbidity and mortality worldwide, and older adults are at especially high risk for developing severe COVID-19. A cohort study of driving behavior from 1/1/19 – 4/25/19 and 1/1/2020 - 4/25/20 was conducted. We hypothesized that older adults would reduce the number of days driving and number of trips/day they make after COVID-19 case acceleration. Data from 214 adults aged 66.5 to 92.8 years were used. Women comprised 47.6% of the sample and 15.4% were African American. Participants reduced the proportion of days driven during the pandemic (0.673 vs. 0.382 [p<.001]) compared to same period the year before (0.695 vs. 0.749). Trips/day showed a similar decline (p<.001). Participants also took shorter trips (p=.02), drove slower (p<.001), had fewer speeding incidents (p<.001), and different trip destinations (p<.001). These results indicate that older adults reduce their driving behavior when faced with a pandemic.

Keywords: social distancing, pandemic, COVID-19, driving, older adult

INTRODUCTION

Detailed examination of human behavior during a pandemic can help identify ways to slow disease transmission and mitigate disease severity and mortality. The highly contagious Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has produced considerable morbidity and mortality worldwide. As of April 25, 2020, the last day that data were collected for this report, COVID-19 had infected more than 2.8 million people and killed at least 200,000 worldwide (CNN, 2020). With no available vaccine or treatment, efforts to fight the disease have largely focused on social distancing.

COVID-19 disproportionately impacts older adults (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020 [a]). Moreover, this age group is at greater risk of developing serious complications due to the virus, and account for the vast majority of deaths due to the virus (Landry et al., 2020; WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2020). Medical risk factors for COVID-19 (e.g., heart disease, diabetes) are especially prevalent among older adults (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020). African Americans are at higher risk for contracting COVID-19 and are more likely to die from the disease (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020 [b]; Yancy, 2020). Therefore, social distancing is especially important for older adults, African Americans, and those with medical risk factors.

Since 2017, we have been following the everyday driving behavior of a cohort of older adults using an unobtrusive data logger installed in their personal vehicle. After installation, participants continue to drive normally in their own environments, traveling when and where they choose. Because we have comprehensive demographic and medical history data, we can identify participants who are at high risk for COVID-19.

We examined changes in daily driving behavior of older adults before and after the onset of very rapid increase in the number of United States (US) COVID-19 cases and compared that behavior to the same time period during the previous year. We hypothesized that, as a response to social distancing recommendations, older drivers would reduce the number and length of trips they took, and that these reductions would be especially pronounced among older adults with characteristics and medical conditions associated with higher rates of COVID-19.

METHODS

Population

Participants were recruited from Washington University Knight Alzheimer Disease Research Center studies and enrolled in a longitudinal study examining driving performance in preclinical Alzheimer disease (R01-AG056466). Participants were cognitively normal (Clinical Dementia Rating [CDR] (Morris, 1993) = 0), ≥ 65 years old, had a valid driver’s license, drove at least once per week, and met minimal visual acuity for driving. Most were retired (Table 1). Participants completed an annual assessment that includes a physical, neurological exam, and health history. The study protocol was approved by the Washington University Institution Research Protection Office (201412024), and written informed consent was obtained.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the sample (N=214) and medical conditions linked to COVID-19.

| Demographics and Risk Factors | |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 76.2 (5.7) |

| Women, No. (%) | 100 (46.7) |

| Education, mean (SD), y | 16.6 (2.3) |

| African American Race, No. (%) | 33 (15.4) |

| State of Residence | |

| Missouri, No. (%) | 189 (88.3) |

| Illinois, No. (%) | 22 (10.3) |

| Colorado, No. (%) | 1 (0.5) |

| Tennessee, No. (%) | 1 (0.5) |

| Texas, No. (%) | 1 (0.5) |

| Employment Status (N=200) | |

| Retired, No. (%) | 174 (87.0) |

| Employed, No. (%) | 23 (11.5) |

| Homemaker, No. (%) | 2 (1.0) |

| Unemployed, No. (%) | 1 (0.5) |

| Texas, No. (%) | 1 (0.5) |

| Risk Factors | |

| Obese, No. (%) | 62 (29.7) |

| Heart Disease, No. (%) | 23 (10.8) |

| Hypertension, No. (%) | 120 (56.1) |

| Diabetes, No. (%) | 24 (11.2) |

| Number of Risk Factors | |

| 0, No. (%) | 62 (29.0) |

| 1, No. (%) | 88 (41.1) |

| 2, No. (%) | 54 (25.2) |

| 3 or More, No. (%) | 10 (4.7) |

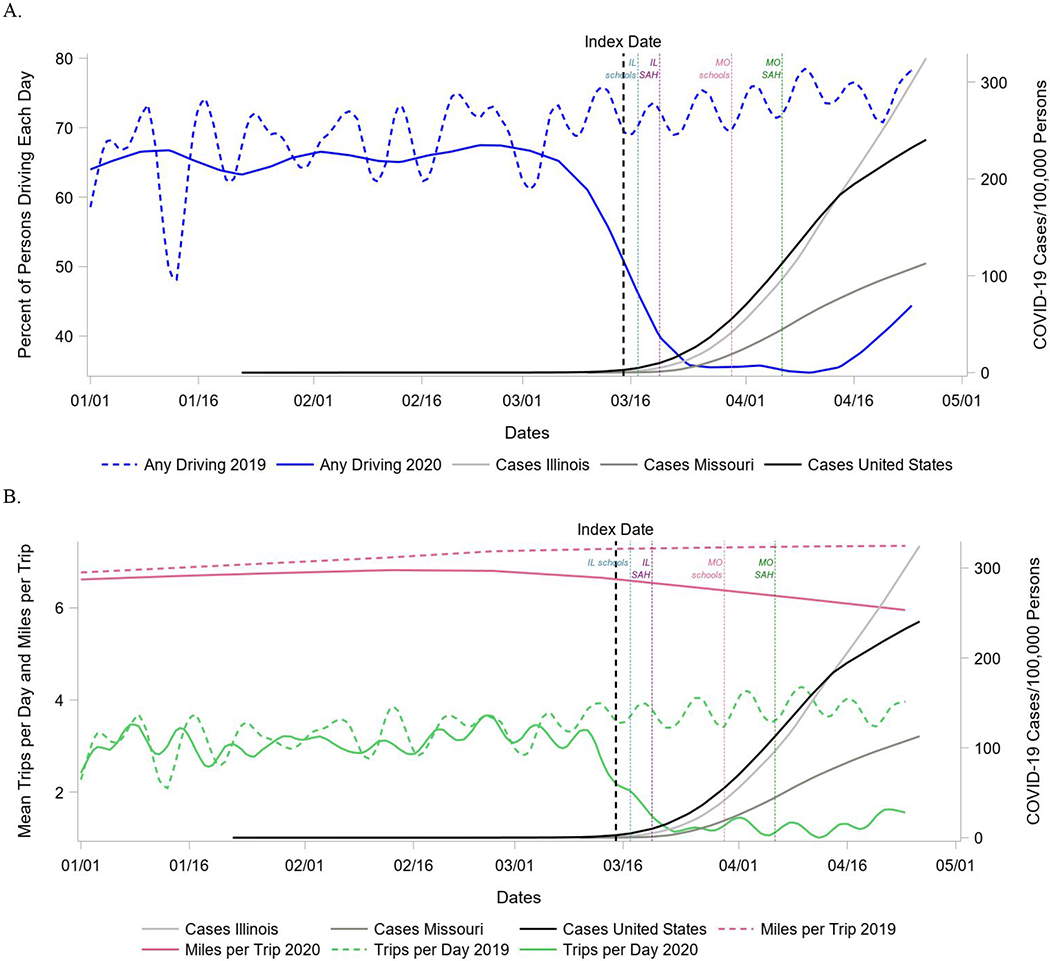

We operationally defined “high risk” for COVID-19 based on the Centers for Disease Control’s designations as being at high risk for contracting or for experiencing severe illness due to race or existing medical conditions (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020 [a]; Centers for Disease Control, 2020 [b]). Confirmed COVID-19 case data were obtained from the Johns Hopkins Center for Systems Science and Engineering (Gardner 2020) for the total US and for Missouri and Illinois. An index date of March 15, 2020 was operationalized based on the point at which the number of COVID-19 cases in the US began to increase rapidly (see Figure 1), presuming that most residents would be aware of the US spread of COVID-19 by then. Figure 1 also shows the number of cases per day for Missouri and Illinois separately, as well as sentinel events (school closings and stay-at-home orders) indicating part of the institutional reaction to the growing COVID-19 crisis. Daily driving data prior to (Pre 2020: 1/1/20-3/14/20) and after (Post 2020: 3/15/20-4/25/20) the index date were compared to each other, and to the same dates the year before (Pre 2019: 1/1/19-3/14/19 and Post 2019: 3/15/19-4/25/19). Two-hundred fifty-seven participants were active on 1/1/19, but only data from N=214 participants (aged 66.5-92.8 years) with complete data collection over the four time periods were included.

Figure 1.

Driving behavior before and after the onset of the pandemic during 2020, and compared to driving during the same time periods in the year prior to the pandemic.

(A) Percent of persons driving each day and (B) mean number of trips per day and miles per trip presented with number of confirmed COVID-19 cases for the entire US, Missouri, and Illinois (second Y axis). Reference lines indicate when school closure and stay-at-home orders went into effect in state, which may have impacted trips made and/or number of other drivers on the road. Abbreviations: IL=Illinois; MO=Missouri; SAH=Stay at Home.

Driving behavior was captured using the Driving Real World In-Vehicle Evaluation System (DRIVES) and a commercial GPS data logger (G2 Tracking Device™, Azuga Inc, San Jose, CA) plugged into the vehicle’s onboard diagnostics–II (OBD-II) port (Babulal et al., 2016; Babulal et al., 2019; Roe et al., 2019). From ignition on, the data logger records the position (latitude and longitude), date, time, and speed of the vehicle every 30 seconds, along with safety-related events whenever they occur (e.g., hard braking) until ignition off. Trips to selected destinations were examined by finding the closest landmark within 0.2 miles of a participant trip end using Missouri and Illinois “Points of Interest” and “Places of Worship” landmarks extracted from OpenStreetMap (Ramm 2019; Haklay & Weber, 2008) (Supplemental Table 1).

Statistical Analysis

General linear models tested the within-subjects effects of Time (same participant, Pre vs. Post period within a year) and Year (same participant, 2019 vs. 2020) and their interaction on seven driving behaviors. This model treated Time and Year as fixed factors (Wolfinger & Chang, 1995), and adjusted for the repeated natures of the Time and Year variables. Days driving and number of trips per day for each of the four periods were examined for all participants. Among participants taking trips, mean length in miles and speed in miles/hour of each trip, along with mean number of three types of aggressive behaviors (hard braking, hard acceleration, speeding)/mile/trip were compared for each Time X Year combination. Analyses were repeated for each between-subject factor (age group [based on a median split], gender, race, and medical conditions). Analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC), alpha of .05 (two-sided), and statistical significance was determined using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995; McDonald 2009) with a false-discovery rate of .05 to address multiple comparison concerns.

RESULTS

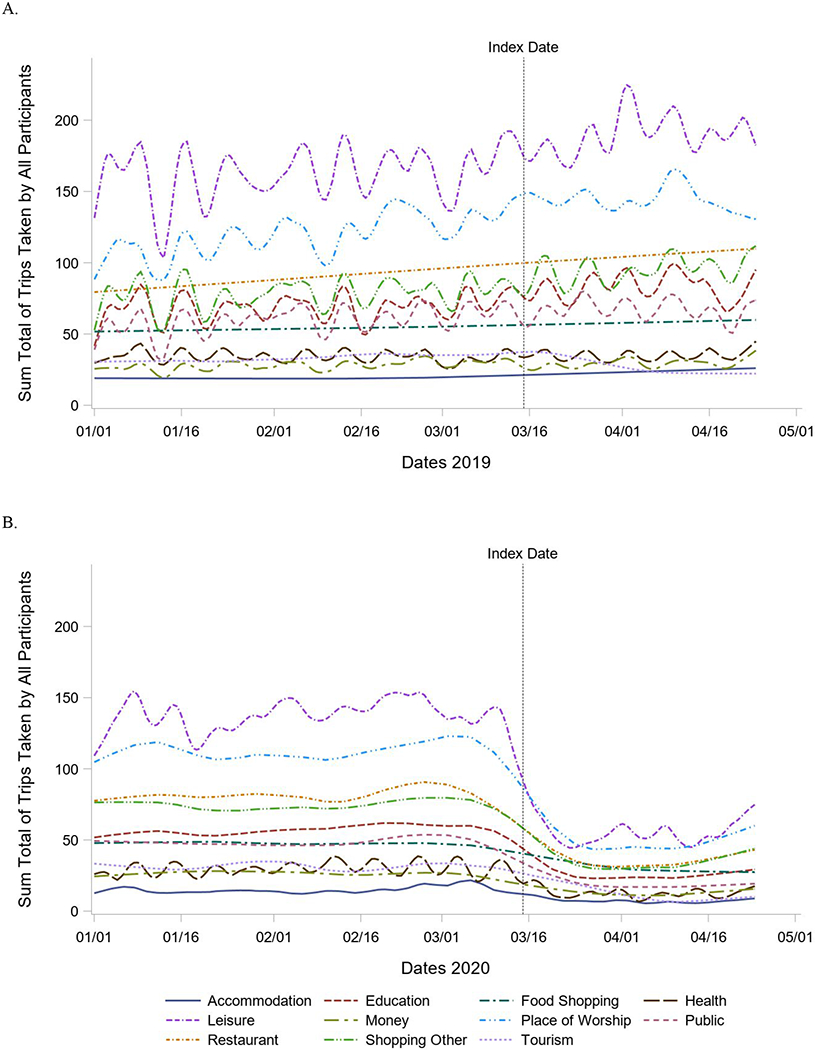

Participants (N=214; Table 1) were aged 66.5 to 92.8 years. Time X Year interactions were found for proportion of days driving, trips/day, miles/trip, speed/trip, and overspeeding such that after the index date participants drove on fewer days, went on fewer trips, went on shorter trips, and had fewer speeding events than before COVID-19 (Supplemental Table 2, Figure 1). Women reduced their percentage of days driving more than men, but changes in driving behavior were unrelated to demographics and medical risk factors otherwise (Supplemental Tables 3 and 4). Participants decreased the number of days they drove and trips/day for the purposes of education, leisure, worship, eating at restaurants, going to public places, and general shopping, but not for food shopping, health, money, and accommodations (Supplemental Table 5, Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Type of trips made.

Trips per day for the entire sample to selected destinations over the Pre-Post study periods in (A) 2019 and (B) 2020.

DISCUSSION

Older adults dramatically decreased the number of trips they took and number of days driving, after the index date (i.e., the time that most persons would presumably have been aware that the pandemic was spreading across the US). Refuting our hypotheses, the extent of social distancing change with pandemic onset was unrelated to most personal characteristics of drivers. This may be a “floor effect” since participants took few trips after the index date. They also showed less speeding during the pandemic which, speculatively, may have been due to less highway driving, and/or less high-speed passing behavior with fewer other drivers on the road. Many businesses were also closed. Older drivers did not decrease their travel for food shopping, healthcare, and money/banking. These destinations are generally essential to everyday life; however, they also occurred with less frequency than other destination categories before COVID-19, so there was less room for decline.

Study participants were highly educated and primarily resided in Missouri and Illinois, therefore the extent to which these findings extend to other populations is unknown. The number of African American participants was small (N=33). Data on lung disease, an important risk factor for COVID-19, were unavailable at the time of manuscript submission but will be obtained and examined in a future report. Study strengths include the ability to longitudinally and continuously study the driving behavior/social distancing of older adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. This allowed us to examine and rule out the possibility that behavior change was an artifact linked to seasonal changes in driving behavior, or to variation in the specific participants comprising the cohort across the study period.

In conclusion, our results suggest that when faced with a pandemic, older adults reduce their driving behavior, which will likely help to prevent transmission of COVID-19 among themselves and in their communities. This appears to be true even among those who are not at especially high risk for getting the disease. Travel may increase as social distancing recommendations are lifted (Stoddart, Osborne, & Cruz, 2020). We will continue to track these participants as they navigate this pandemic and its aftermath, and will explore additional demographic, medical, and environmental factors that may be related to transmission of COVID-19.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The authors thank the participants, investigators/staff of the Driving Performance in Preclinical Alzheimer’s Disease study (R01-AG056466), and the investigators/staff of the Knight Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center. Additional thanks to Vaisakh Puthusseryppady and Dr. Michael Hornberger for their help in obtaining the Open Street Map data.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging [grant numbers R01-AG056466, R03-AG055482, P50-AG05681, P01-AG03991, P01-AG026276]; Fred Simmons and Olga Mohan; and the Charles and Joanne Knight Alzheimer’s Research Initiative. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interests:

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

IRB protocol/human subjects approval numbers: Washington University School of Medicine Human Research Protection Office (201412024).

REFERENCES

- Babulal GM, Stout SH, Benzinger TLS et al. (2019). A naturalistic study of driving behavior in older adults and preclinical Alzheimer disease: A pilot study. J Appl Gerontol. 38(2):277–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babulal GM, Traub CM, Webb M et al. (2016). Creating a driving profile for older adults using GPS devices and naturalistic driving methodology. Version 2. F1000Res, 5:2376 eCollection 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. JR Stat Soc B (Methodol), 57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (a). People Who Need to Take Extra Precautions. Updated April 29, 2020 (2020, May 1). Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-at-higher-risk.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (b). Health Equity Considerations and Racial and Ethnic Minority Groups. Updated July 24, 2020 (2020, July 27). Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/health-equity/race-ethnicity.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fcoronavirus%2F2019-ncov%2Fneed-extra-precautions%2Fracial-ethnic-minorities.htmll

- CNN. April 25 coronavirus news. (2020, August 4). Retrieved from: https://www.cnn.com/world/live-news/coronavirus-pandemic-04-25-20-intl/index.html

- Gardner L Mapping 2019-nCoV. Johns Hopkins Whiting School of Engineering; (2020, May 1). Retrieved from: https://systems.jhu.edu/research/public-health/ncov/ [Google Scholar]

- Haklay M, Weber P (2008). OpenStreetMap: User-generated street maps. IEEE Pervasive Computing, 7(4),12–18. [Google Scholar]

- Landrey MD, Vanden Bergh G, Hjelle KM, Jalovcic D, Tuntland HK (2020) Betrayal of trust? The impact of the COVID-19 global pandemic on older persons. J Appl Gerontol. 39(7):687–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald JH (2009). Handbook of Biological Statistics. Baltimore, MD: Sparky House Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Morris JC (1993). The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): Current version and scoring rules. Neurology, 43:2412–2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramm F OpenStreetMap data in layered GIS format. (2020, May 1). Retrieved from: https://download.geofabrik.de/osm-data-in-gis-formats-free.pdf

- Roe CM, Stout SH, Rajasekar G et al. (2019). A 2.5-Year longitudinal assessment of naturalistic driving in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis, 68:1625–1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoddart M, Osborne M, Cruz A When each state’s stay-at-home order lifts. (2020, May 1). Retrieved from: https://abcnews.go.com/US/list-states-stay-home-order-lifts/story?id=70317035

- WHO Regional Office for Europe. (2020, April 6). Press briefing on COVID-19 and the health and well-being of older people. https://www.facebook.com/WHOEurope/videos/163802871435665/

- Wolfinger RD, Chang M (1995). Comparing the SAS GLM and MIXED procedures for repeated measures. Proceedings of the Twentieth Annual SAS Users Group Conference . SAS Institute Inc.: Cary, NC. [Google Scholar]

- Yancy CW (2020). COVID-19 and African Americans. JAMA. 2020;323(19):1891–1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.