Abstract

Antibiotic resistance is a global health crisis that requires urgent action to stop its spread. To counteract the spread of antibiotic resistance, we must improve our understanding of the origin and spread of resistant bacteria in both community and healthcare settings. Unfortunately, little attention is being given to contain the spread of antibiotic resistance in community settings (i.e., locations outside of a hospital inpatient, acute care setting, or a hospital clinic setting), despite some studies have consistently reported a high prevalence of antibiotic resistance in the community settings. This study aimed to investigate the prevalence of antibiotic resistance in commensal Escherichia coli isolates from healthy humans in community settings in LMICs. Using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, we synthesized studies conducted from 1989 to May 2020. A total of 9363 articles were obtained from the search and prevalence data were extracted from 33 articles and pooled together. This gave a pooled prevalence of antibiotic resistance (top ten antibiotics commonly prescribed in LMICs) in commensal E. coli isolates from human sources in community settings in LMICs of: ampicillin (72% of 13,531 isolates, 95% CI: 65–79), cefotaxime (27% of 6700 isolates, 95% CI: 12–44), chloramphenicol (45% of 7012 isolates, 95% CI: 35–53), ciprofloxacin (17% of 10,618 isolates, 95% CI: 11–25), co-trimoxazole (63% of 10,561 isolates, 95% CI: 52–73), nalidixic acid (30% of 9819 isolates, 95% CI: 21–40), oxytetracycline (78% of 1451 isolates, 95% CI: 65–88), streptomycin (58% of 3831 isolates, 95% CI: 44–72), tetracycline (67% of 11,847 isolates, 95% CI: 59–74), and trimethoprim (67% of 3265 isolates, 95% CI: 59–75). Here, we provided an appraisal of the evidence of the high prevalence of antibiotic resistance by commensal E. coli in community settings in LMICs. Our findings will have important ramifications for public health policy design to contain the spread of antibiotic resistance in community settings. Indeed, commensal E. coli is the main reservoir for spreading antibiotic resistance to other pathogenic enteric bacteria via mobile genetic elements.

Subject terms: Bacterial infection, Health policy, Antibiotics, Antimicrobial resistance, Symbiosis

Introduction

Antibiotic resistance (ABR) is currently identified as one of the biggest threats to not only global health but also to food security and development1. Resistance occurs when the antibiotics (medicines used to prevent and treat bacterial infections) are no longer effective at inhibiting the growth of the bacteria1. There is a growing increase of resistance by bacteria to antibiotics2–10 with the World Health Organization (WHO) through its Global Antimicrobial Surveillance System (GLASS) report revealing that there are high levels of antibiotic resistance in both low- and high-income countries11. In fact, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) reported that 25,000 people died of diseases caused by antibiotic-resistant bacteria in 2007, which is over half the number caused by road traffic accidents in the same countries12. In 2015, this number increased to about 33,000 deaths resulting from an estimated 671,689 infections of selected antibiotic-resistant bacteria leading to 874,541 total disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs)13. This indicates that the burden in the European Union and European Economic Area is on the rise. Likewise, the World Health Organization (WHO) predicted that by 2050, the number of people who will die due to antibiotic resistance would increase from 700,000 to about 10 million per year globally14. As a result of antibiotic resistance, more than 2.8 million people are infected, and more than 35,000 die each year in the USA15,16.

The burden caused by antibiotic resistance is greater in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) whose health care systems are poor and lack tools to perform rapid diagnosis of the numerous neglected infectious diseases17. In the community settings in LMICs, high prevalence of multidrug-, extensive drug-, and pan drug-resistant commensal Escherichia coli isolated from healthy humans has been reported18. Thus, greater efforts should be placed in LMICs to contain the spread of antibiotic-resistant E. coli, especially with its relaxed antibiotics prescription policies. Antibiotic resistance has led to an increase in poverty in LMICs16, and antibiotics misuse is associated with the carriage of resistant commensal E. coli from healthy children in community settings worldwide19,20. In high-income countries, stringent antibiotic prescription policies are in place to reverse the course of antibiotic resistance21.

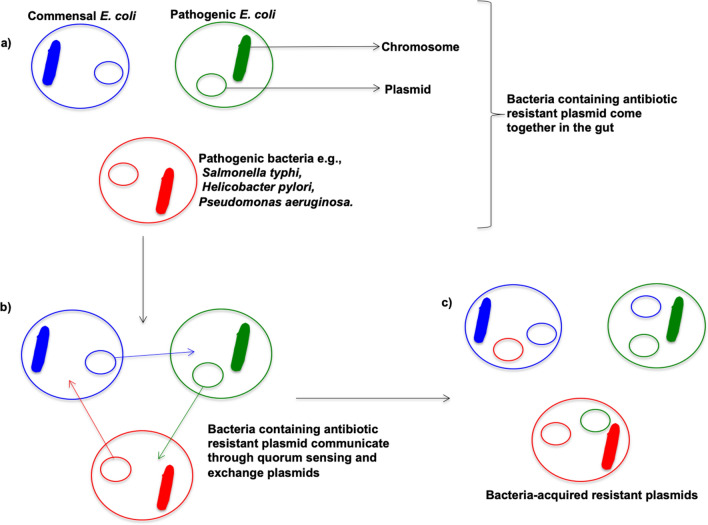

Commensal Escherichia coli is a gram-negative bacterium located in the gut of humans, animals, birds, and also exists in the environment22. It is a pathogen on the WHO global critical pathogen priority list for research, discovery, and new antibiotics development23. When we ingest antibiotics for the treatment of bacterial infections, the commensal E. coli is exposed to these antibiotics and can develop resistance to these antibiotics through natural selection24. Indeed, commensal E. coli is one of the major reservoirs for the transmission of antibiotic resistance to other pathogenic bacteria through plasmid exchange, for example (Fig. 1)25–32. Humans can be exposed to viable commensal antibiotic-resistant E. coli by contact with livestock or a contaminated natural environment and by inadequately cooked food or cross-contamination33–35.

Figure 1.

Transfer of resistance between bacteria through plasmid exchange. (a) Commensal E. coli, pathogenic E. coli and other pathogenic bacteria come together in the gut, (b) Bacteria attached and exchanged plasmids conferring antibiotic resistance. (c) Bacteria-acquired resistant plasmids.

Many studies have shown a high prevalence of resistance to antibiotics by pathogenic and commensal bacteria in healthcare settings8. However, when comparing these studies to those conducted in community settings there is a large discrepancy, especially in LMICs36. This is as a result of the fact that little attention is given at the community level to contain the global antibiotic resistance crises; despite some studies that compare the prevalence of resistance to antibiotics in both communities and hospitals all showed consistently high values with no significant difference8,22,37–40. Thus, similar attention should be given to contain the cause of resistance to antibiotics by bacteria in communities, as is the case in hospitals. If this situation is not addressed, many of the gains in modern medicine will be lost and the commitment to achieve universal health coverage by world leaders will be in vain7,41. In this paper, we aim to provide an appraisal of the evidence of the high prevalence of antibiotic resistance by commensal E. coli to commonly prescribed antibiotics in community settings (i.e., locations outside the hospital such as homes and schools) in LMICs to bring to light the extent of the problem and inform interventions targeted at controlling and preventing antibiotic resistance. Indeed, a multitude of knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP), education, and community engagement interventions exist in community settings in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), yet data to support and justify their set-up are often lacking. Thus, our data should prove useful to support the course for the fight against antibiotic resistance by researchers, community pharmacists, public health policymakers, advocacy groups, farmers, among others. A collective approach involving every country to fight antibiotic resistance is crucial to reduce the mortality, morbidity, associated health and healthcare costs, and the spread of resistant bacteria10,42.

Results

Literature search

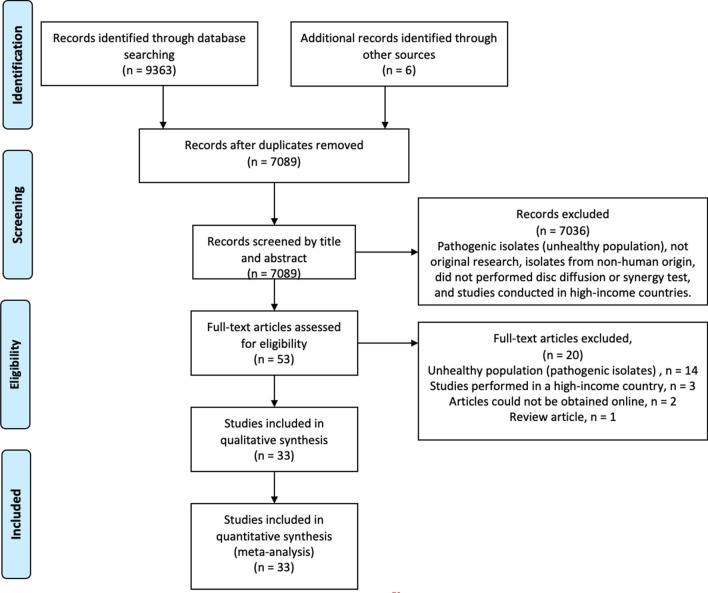

A total of 9363 articles were obtained from the search (PubMed = 3634, EMBASE + MEDLINE = 2103, Web of Science = 3046, CINAHL = 290 and Cochrane Library = 289). Out of the 9363 articles, 2280 duplicates were removed using EndNote X8. We screened 7089 articles to identify article hits that met our inclusion criteria (Fig. 2). We performed a full-text screening of 53 studies and data were extracted from 33 articles8,28,29,43–72. A total of 20 articles in which the isolates were pathogenic (14), were collected in a high-income country (3), could not be obtained online (2), or review articles (1) were excluded for data extraction.

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of the literature search strategy73. Additional records were identified from the reference lists of some of the included studies.

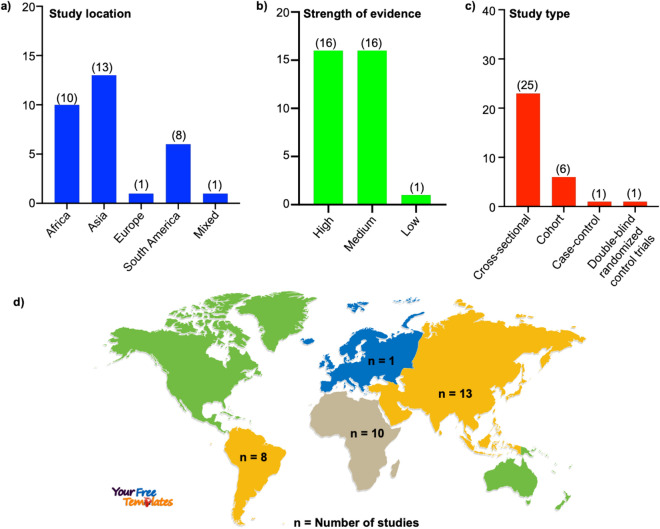

Study location, strength of evidence, and study type

Out of the 33 included studies, 10 were from Africa, 13 from Asia, 1 from Europe, 8 from South America, and 1 from multiple locations (Fig. 3a,d). The quality of the evidence was assessed as described previously74,75. Of the 33 studies, 16 were marked as high quality, 16 as a medium, and 1 as low quality (Fig. 3b). These included studies were cross-sectional (25), cohort (6), case–control (1), and double-blind randomized control trials (1) (Fig. 3c).

Figure 3.

Characteristics of the included studies. (a) Location, (b) quality of the evidence, and (c) type of studies. (d) World map showing the number of studies by continents. The world map was obtained from (https://yourfreetemplates.com/) on 17th December 2020.

Age, sample size, and gender

The included studies comprise of about 7755 health individuals in community settings from 0 to 77 years of age from 1989 to 2019. One limitation of this study is that some articles did not record the number of males and females, thus it was challenging to determine the ratio of males to females. However, we calculated the number of males and females using the studies that recorded the numbers. Of these studies, 2443 were males and 2010 were females. Thus, assuming a total population of 7755, we extrapolated the number of males to be 4255, and females 3500.

High prevalence of antibiotic resistance in the community settings will potentially impact health policy

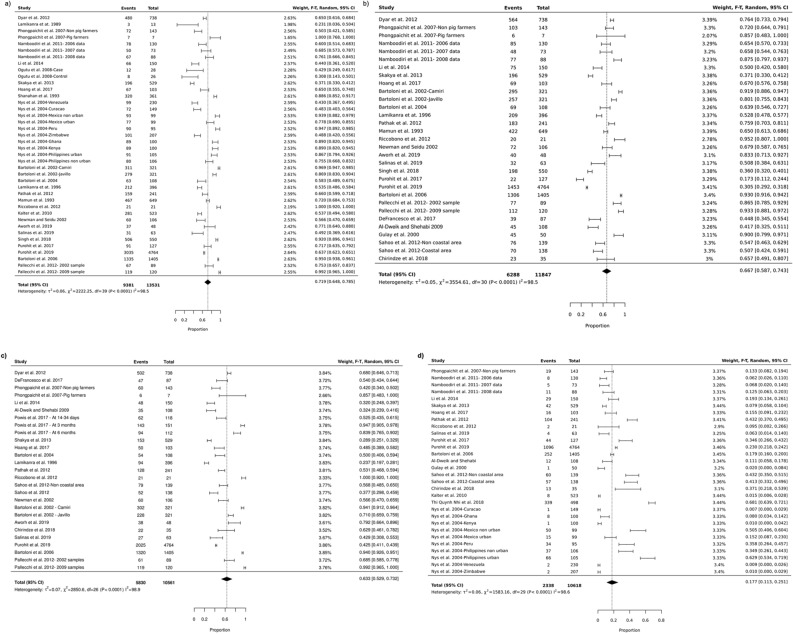

The pooled prevalence of commensal E. coli isolated from healthy individuals in community settings in LMICs for the different antibiotics are summarized in Table 1, Fig. 4, and Supplementary Fig. 1. A high prevalence was seen for some of the commonly prescribed antibiotics in these countries like ampicillin (72%, 95% CI: 65–79), cefotaxime (27%, 95% CI: 12–44), chloramphenicol (45%, 95% CI: 35–53), ciprofloxacin (17%, 95% CI: 11–25), co-trimoxazole (63%, 95% CI: 52–73, nalidixic acid (30%, 95% CI: 21–40), oxytetracycline (78%, 95% CI: 65–88), streptomycin (58%, 95% CI: 44–72), tetracycline (67%, 95% CI: 59–74), and trimethoprim (67%, 95% CI: 59–75). These findings will be very useful for evidence-based health policy design aimed at combating the spread of antibiotic resistance in the community.

Table 1.

Prevalence of antibiotic resistance in commensal E. coli isolated from human sources in community settings in low- and middle-income countries.

| Antibiotics | Mechanism of inhibition | Study number | Total number of isolates | Number of resistant isolates | Pooled prevalence (%) | Lower bound 95% CI | Upper bound 95% CI | I2 (%) | Quality of the evidence (study number) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ampicillin | Cell wall synthesis | 25 | 13,531 | 9381 | 72 | 65 | 79 | 99 | High (13), medium (11), low (1) | 8,28,29,43,44,46,47,49,50,53,55,58–66,68–72 |

| Cefotaxime | Cell wall synthesis | 10 | 6700 | 3493 | 27 | 12 | 44 | 99 | High (3), medium (7), low (0) | 28,29,43,47,48,53,55,57,58,60 |

| Chloramphenicol | Protein synthesis | 18 | 7012 | 3343 | 45 | 35 | 53 | 99 | High (11), medium (6), low (1) | 8,28,29,43,44,47–49,53,59,60,62–64,66,68–70 |

| Ciprofloxacin | Nucleic acid synthesis | 19 | 10,618 | 2338 | 17 | 11 | 25 | 99 | High (11), medium (8), low (0) | 26,37,38,41–43,45,47–52,55,58–60,65,66 |

| Co-trimoxazole | Folate synthesis | 20 | 10,561 | 5830 | 63 | 52 | 73 | 98 | High (10), medium (10), low (0) | 8,28,29,43,45,47,49–53,55–57,59–61,63,70,72 |

| Nalidixic acid | Nucleic acid synthesis | 21 | 9819 | 3960 | 30 | 21 | 40 | 99 | High (10), medium (10), low (1) | 8,28,29,43,46–49,51,55,57–59,61,63,64,66,68–71 |

| Oxytetracycline | Protein synthesis | 2 | 1451 | 1047 | 78 | 65 | 88 | 96 | High (0), medium (2), low (0) | 44,67 |

| Streptomycin | Protein synthesis | 13 | 3831 | 2610 | 58 | 44 | 72 | 99 | High (9), medium (3), low (1) | 29,47,48,53,61–64,66,69,70,72 |

| Tetracycline | Protein synthesis | 25 | 11,847 | 6288 | 67 | 59 | 74 | 99 | High (15), medium (10), low (0) | 8,28,29,43,45,47–51,53,55–64,66,70–72 |

| Trimethoprim | Folate synthesis | 9 | 3265 | 1854 | 67 | 59 | 75 | 98 | High (3), medium (5), low (1) | 28,44,46,48,64,66–69 |

Figure 4.

Forest plots showing the prevalence of antibiotic resistance in commensal E. coli isolated from human sources in community settings in low- and middle-income countries. (a) Cell wall synthesis inhibitor (ampicillin), (b) protein synthesis inhibitor (tetracycline), (c) folate synthesis inhibitor (co-trimoxazole), and (d) nucleic acid synthesis inhibitor (ciprofloxacin).

Prevalence of antibiotic resistance data of a plethora of antibiotics will potentially impact antibiotic stewardship programs

In this study, the prevalence of resistance was collected for a range of diverse antibiotics and mechanisms of actions such as, inhibition of protein, nucleic acid, folic acid, or cell wall synthesis. For some antibiotics, the resistance was very high, others were emerging, and for some it was low (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 4). This evidence should prove useful to inform antibiotic stewardship programs.

Investigating the source of heterogeneity

The results show a high I2 value, which indicates considerable heterogeneity. Funnel plots and Egger’s regression test was used to explore the sources of heterogeneity. The funnel plots for all antibiotics were asymmetrical (Supplementary Fig. 2), thus indicating a possibility of publication bias. We further investigate the existence of publication bias per antibiotic using Egger’s regression test (Supplementary Table 5). Most of the antibiotics (ampicillin, cefotaxime, co-trimoxazole, nalidixic acid, streptomycin, and trimethoprim) did not exhibit publication bias. The antibiotics that exhibited publication bias were chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin, oxytetracycline, and tetracycline. On further stratification of each antibiotic prevalence, according to continents (Africa, South America, and Asia), there was a reduced likelihood of publication bias based on visual examination of the funnel plot.

Discussion

Antibiotic resistance (ABR) is a serious global health threat that needs to be addressed urgently2–8. ABR's impact is particularly greater in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), which bear the highest-burden and subsequently suffer the most from this problem, primarily because their healthcare systems lack the resources needed to contain or to treat challenging infectious diseases caused by drug-resistant bacteria17. Indeed, it has led to an increase in poverty in LMICs16. While there has been a general increase in multidrug-resistant pathogenic bacteria in community settings77 recent evidence suggests that the prevalence of multidrug-resistant commensal Escherichia coli isolated from healthy individuals is particularly high in LMICs18. In this study, we synthesized a total of 33 articles to obtain a pooled prevalence of ABR in the top ten antibiotics commonly prescribed in community settings (i.e., locations outside of a hospital, such as schools and homes) in LMICs.

There are several factors that contribute to ABR78, with a complicated inter-relationship that spans across different sectors outside of healthcare alone, such as agriculture and industry. Among the main factors identified leading to resistance in commensal E. coli in LMICs are overcrowding, poverty, socioecological behaviours, food and supply chain safety issues, highly contaminated waste effluents and inadequate surveillance systems79. Nevertheless, the primary driver of multidrug-resistance in LMICs has been misuse and over-prescription of antibiotics80. Commensal E. coli are typically present in the guts of humans, animals, birds, as well as in the environment, and can develop resistance to antibacterial agents through natural selection when ingested for the treatment of bacterial infections22,24.

This review revealed a high prevalence of antibiotic resistance in commensal E. coli to the most prescribed antibiotics in LMICs. Moreover, this was a consistent finding across several classes of antibiotics with different mechanisms of action. For instance, the pooled prevalence of antibiotic resistance for the β-lactam antibiotic ampicillin was 72%, 95% CI: 65–79, while for trimethoprim, a folic acid synthesis inhibitor, the pooled prevalence was 67%, 95% CI: 59–75. Similar observations were reported in a recent systematic review investigating ABR in E. coli strains isolated from humans, animals, food, and the environment in several middle- and high-income countries. The authors presented high rates of resistance against a range of antibiotics found in E. coli isolates, although the pooled prevalence was generally lower than in the isolates from healthy individuals from LMICs presented here81. For ciprofloxacin, the pooled prevalence from our study was 17%, 95% CI: 11–25, which is in the range of the resistance seen for treating E. coli associated urinary tract infection (8% to 65%)11, and other E. coli isolated from farmed minks in Zhucheng, China76. Likewise, for cotrimoxazole, our data (63%, 95% CI, 52–73) agrees with another study carried out in Zimbabwe, where the prevalence was 68% for Gram-negative bacillli82. The main limitation of our study is the fact that the heterogeneity between studies was very high (Table 1, Fig. 4). We performed an additional statistical analysis stratified by continent. The goal was to solve the heterogeneity issue, however, there was no significant difference between the pooled prevalence of antibiotic resistance values between continents. The high heterogeneity between studies could stem from the different factors associated with the carriage resistant commensal E. coli in LMICs highlighted in the discussion section above. Since I2 statistics test for heterogeneity can be misleading during meta-analysis of observational studies83,84, we performed an alternative assessment of the strength of evidence of the different studies (supplementary table 3)74,75. The included studies utilized disc diffusion or synergy test to investigate the expression of resistant genes in the presence of antibiotics. However, those that employed an additional method, such as PCR, plasmid transfer assay, nucleic acid identification, mass spectrometry, to validate the presence of genes conferring resistance to a particular antibiotic were graded as high.

Our study is in line with the WHO’s Global action plan on antimicrobial resistance, which calls for improved awareness of the problems arising from antibiotic resistance as stated in one of the five strategic objectives85. Indeed, raising awareness can be facilitated, for example, through the making of participatory videos86. As expected, in this study, resistance was commonly detected from stool samples collected from healthy volunteers in community settings. Our findings have important ramifications for public health policies and antibiotic resistance stewardship through a one-health approach for the fight against ABR. In some of the studies screened, factors such as previous antibiotic use19,55,59,65, geographical location8,57, age8,59, socioeconomic status43,55,57, and exposure to animals49,65 were highlighted as being associated with a high prevalence of resistance. The situation is even more pressing with the emergence of global pandemics such as the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID19) caused by the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)87. Prior to the availability of approved vaccines, different medicines have been tested randomly in clinical trials to find a cure for this deadly pandemic87–94. Since viral infections are often associated with bacterial infections95,96, the antibiotic azithromycin in combination with the antimalarial drug hydroxychloroquine was proposed as an option for the treatment of COVID19 patients97. Thus, we may see a post-COVID19 global health crisis with a surge in antibiotic resistance leading to many deaths97.

Conclusion

This study provides further evidence of the high prevalence of antibiotic resistant commensal E. coli from healthy human sources in community settings in LMICs. These findings should encourage health researchers, medical professionals, advocacy groups, and health policymakers to work together to develop appropriate interventions to counteract this growing global health threat. We recommend that the strategies that have been implemented in healthcare settings to contain the spread of resistance, such as surveillance, raising awareness, improve sanitation and hygiene, rapid diagnosis of diseases, and stringent prescription policies should also be urgently implemented in the communities to curb antibiotic resistance.

Methods

Design

A systematic approach was used to retrieve and synthesize studies that met our inclusion criteria following PRISMA guidelines73.

Type of studies

The types of studies included in the systematic review are those in which the main outcome was the prevalence of antibiotic resistance in commensal Escherichia coli: cross-sectional, case–control, cohort studies, and randomized control trials.

Type of participants (study population)

This review included studies concerning the general healthy populations in community settings in LMICs.

Outcome of interest

The primary outcome was prevalence of resistance to antibiotic by commensal E. coli in community settings in LMICs.

The secondary outcomes were: odds ratio, risk ratio, rate, 95% confidence interval, and p-value.

Other inclusion and exclusion criteria

Articles written in English language were included from 1989 to May 2020 in LMICs. Articles containing studies conducted in a country that was classified as a LMIC before transforming into a high-income country according to the World Bank definition were also included. The included studies must investigate the resistance of commensal E. coli on either solid or liquid growth media in the presence of antibiotics.

Essential data necessary for inclusion

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they reported at least one of the primary or secondary outcomes listed in the outcome of interest section above.

Data sources

Published data from PubMed, EMBASE, MEDLINE, Web of Science, CINAHL and Cochrane Library, reference lists of selected studies and unpublished data such as abstracts from Conference proceedings; dissertations and theses were the data sources.

Systematic search strategy

A literature search was performed on the 10th of March 2018 and was updated on the 18th of May 2020. Briefly, we searched PubMed, EMBASE, MEDLINE, Web of Science, CINAHL, and Cochrane Library using MeSH terms for PubMed and the comparable terms for the other databases. The search terms were “E. coli OR Escherichia coli OR Enterobacteriaceae” AND "antibiotic resistance OR antimicrobial resistance OR drug resistance” AND "prevalence OR incidence OR morbidity OR odd ratio OR risk ratio OR confidence interval OR p-value OR rate". For PubMed, EMBASE, and MEDLINE, studies performed in humans were selected using the Species filters. While for Web of Science and Cochrane Library additional search words were added to select for species (human* OR infant* OR child* OR adolescen* OR male* OR female OR age OR adult*) since there was no sorting filter for species. For CINAHL, no selection for species was performed. Search words were designed from the different categories in the PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome) format. Details of the search terms used are summarized in Supplementary Table 1. The articles obtained from the search were exported to EndNote for duplicate removal. The unique hits were further exported to Rayyan QCRI website for screening and data extraction98. An initial screening was performed by title and abstract, followed by full article text.

Data extraction and quality assessment

A two-step process was followed involving screening of titles and abstracts to identify relevant articles, which was followed by full-text reading of the relevant articles. A total of 53 full-text articles were screened, and the data extracted and recorded on an excel spreadsheet by five researchers. To exclude selection bias, a sixth researcher was available to solve the disagreements that arose during the data extraction. The parameters that were extracted are listed in Supplementary Table 2. The quality of evidence in the included studies was assessed as described before72,73 (Supplementary Table 3). In brief, studies that utilized disc diffusion or synergy test in combination with one of the following biochemical test such as, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), plasmid transfer assay (PTA), pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), nucleic acid sequencing, and mass spectrometry to detect the presence of resistant genes was graded as high. Furthermore, studies which use only disc diffusion of synergy test with a sample size less than 15 were classified as medium. Lastly, studies which sample size of below 15 and utilized only disc diffusion or synergy test were classified as low.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed in Stata99 and JBI SUMARI100. The prevalence of antibiotic resistance of commensal E. coli was defined as the proportion of the isolates in a specific study that were found to be resistant to a given antibiotics presented as a percentage. The pooled prevalence was calculated using the metaprop command in Stata101. Metaprop pools proportions and presents a weighted sub-group and overall pooled estimates with inverse-variance weights obtained from a random-effects model. In this case, it involved a meta-analysis of the prevalence values of the individual publications weighted on sample size while accounting for potential heterogeneity between studies. For JBI SUMARI, proportional meta-analysis was calculated using the random-effects model of Freeman-Tukey transformation. Besides, a forest plot was constructed for each of the top ten most reported antibiotics in our study.

The source of heterogeneity was explored by stratifying the pooled prevalence by year of sample analysis (study period), geographical location (continents), and type of antibiotic. Funnel plots of overall effect size were run to determine the existence of publication bias by visual inspection. Also, the Egger’s test was used to assess the occurrence of small size effect. The level of significance was maintained at 0.05.

Supplementary Information

Author contributions

E.N. designed and supervised the project. E.N. wrote the manuscript text and prepared all figures and Tables. E.N. performed the systematic database search. L.T.Q.L., and C.S.L., supervised the preliminary project proposal. E.N. extracted the data with assistance from J.K., T.H., L.A.O.D., L.D., N.A.N., and C.A.J. E.N. performed statistical analysis on JBI SUMARI. J.K., performed the statistical analysis on Stata with assistance from T.H., and E.N. T.H., L.T.Q.L., C.A.J., J.K., and C.S.L. read and provided feedback on the manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Karolinska Institute.

Data availability

Data related to the manuscript is available upon request to corresponding author.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-82693-4.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Antibiotic Resistance. (2020).

- 2.Tanwir, F. & Khiyani, F. Antibiotic resistance: A global concern. J. Coll. Phys. Surg. -Pak. JCPSP21, 127–129 (2011). [PubMed]

- 3.Rogers BA, Sidjabat HE, Paterson DL. Escherichia coli O25b-ST131: A pandemic, multiresistant, community-associated strain. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2011;66:1–14. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pitout JD, Laupland KB. Extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae: An emerging public-health concern. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2008;8:159–166. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70041-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rice LB. The clinical consequences of antimicrobial resistance. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2009;12:476–481. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eliopoulos GM, Cosgrove SE, Carmeli Y. The impact of antimicrobial resistance on health and economic outcomes. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2003;36:1433–1437. doi: 10.1086/375081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghebreyesus TA. Making AMR history: A call to action. Glob. Health Action. 2019;12:1638144. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2019.1638144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dyar OJ, et al. High prevalence of antibiotic resistance in commensal Escherichia coli among children in rural Vietnam. BMC Infect. Dis. 2012;12:92. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-12-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laxminarayan R, et al. The Lancet Infectious Diseases Commission on antimicrobial resistance: 6 years later. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020;20:e51–e60. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hernando-Amado S, Coque TM, Baquero F, Martínez JL. Defining and combating antibiotic resistance from one health and global health perspectives. Nat. Microbiol. 2019;4:1432–1442. doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0503-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization. High Levels of Antibiotic Resistance Found Worldwide, New Data Shows. (2018).

- 12.The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. The Bacterial Challenge: Time to React. (Stockholm, 2009).

- 13.Cassini A, et al. Attributable deaths and disability-adjusted life-years caused by infections with antibiotic-resistant bacteria in the EU and the European Economic Area in 2015: A population-level modelling analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2019;19:56–66. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30605-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Kraker MEA, Stewardson AJ, Harbarth S. Will 10 million people die a year due to antimicrobial resistance by 2050? PLOS Med. 2016;13:e1002184. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U.S.). Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 10.15620/cdc:82532 (2019).

- 16.Jim, O. Tackling Drug-Resistant Infections Globally: Final Report and Recommendations. (2016).

- 17.Balkhy, H. H. et al. Antimicrobial resistance: One world, one fight! Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control4 (2015).

- 18.Nkansa-Gyamfi NA, Kazibwe J, Traore DAK, Nji E. Prevalence of multidrug-, extensive drug-, and pandrug-resistant commensal Escherichia coli isolated from healthy humans in community settings in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Glob. Health Action. 2019;12:1815272. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2020.1815272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bryce A, Costelloe C, Hawcroft C, Wootton M, Hay AD. Faecal carriage of antibiotic resistant Escherichia coli in asymptomatic children and associations with primary care antibiotic prescribing: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2016;16:359. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-1697-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malik B, Bhattacharyya S. Antibiotic drug-resistance as a complex system driven by socio-economic growth and antibiotic misuse. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:9788. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-46078-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanchez GV, Fleming-Dutra KE, Roberts RM, Hicks LA. Core elements of outpatient antibiotic stewardship. MMWR Recomm. Rep. 2016;65:1–12. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr6506a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alekshun MN, Levy SB. Commensals upon us. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2006;71:893–900. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Global Priority List of Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria to Guide Research, Discovery, and Development of New Antibiotics. (2017).

- 24.Allocati N, Masulli M, Alexeyev M, Di Ilio C. Escherichia coli in Europe: An Overview. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 2013;10:6235–6254. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10126235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salyers AA, Gupta A, Wang Y. Human intestinal bacteria as reservoirs for antibiotic resistance genes. Trends Microbiol. 2004;12:412–416. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blake DP, Hillman K, Fenlon DR, Low JC. Transfer of antibiotic resistance between commensal and pathogenic members of the Enterobacteriaceae under ileal conditions. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2003;95:428–436. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2003.01988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li B, Qiu Y, Song Y, Lin H, Yin H. Dissecting horizontal and vertical gene transfer of antibiotic resistance plasmid in bacterial community using microfluidics. Environ. Int. 2019;131:105007. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2019.105007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lamikanra A, Ako-Nai AK, Ogunniyi DA. Transferable antibiotic resistance in Escherichia coli isolated from healthy Nigerian school children. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 1996;7:59–64. doi: 10.1016/0924-8579(96)00011-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li B, et al. Antimicrobial resistance and integrons of commensal Escherichia coli strains from healthy humans in China. J. Chemother. Florence Italy. 2014;26:190–192. doi: 10.1179/1973947813Y.0000000113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lambrecht, E. et al. Commensal E. coli rapidly transfer antibiotic resistance genes to human intestinal microbiota in the mucosal simulator of the human intestinal microbial ecosystem (M-SHIME). Int. J. Food Microbiol.311, 108357 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Massot M, et al. Phylogenetic, virulence and antibiotic resistance characteristics of commensal strain populations of Escherichia coli from community subjects in the Paris area in 2010 and evolution over 30 years. Microbiology. 2016;162:642–650. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.000242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McInnes RS, McCallum GE, Lamberte LE, van Schaik W. Horizontal transfer of antibiotic resistance genes in the human gut microbiome. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2020;53:35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2020.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marshall BM, Levy SB. Food animals and antimicrobials: Impacts on human health. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2011;24:718–733. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00002-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Founou, L. L., Founou, R. C. & Essack, S. Y. Antibiotic resistance in the food chain: A developing country-perspective. Front. Microbiol.7 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Gómez-Gómez C, et al. Infectious phage particles packaging antibiotic resistance genes found in meat products and chicken feces. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:13281. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-49898-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ingle DJ, Levine MM, Kotloff KL, Holt KE, Robins-Browne RM. Dynamics of antimicrobial resistance in intestinal Escherichia coli from children in community settings in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. Nat. Microbiol. 2018;3:1063–1073. doi: 10.1038/s41564-018-0217-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Isenbarger DW, et al. Comparative antibiotic resistance of diarrheal pathogens from Vietnam and Thailand, 1996–1999. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2002;8:175–180. doi: 10.3201/eid0802.010145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Duerink DO, et al. Determinants of carriage of resistant Escherichia coli in the Indonesian population inside and outside hospitals. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2007;60:377–384. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nguyen TTH, et al. Antibiotic sensitivity of enteric pathogens in Vietnam. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 1991;1:121–126. doi: 10.1016/0924-8579(91)90006-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Furuya EY, Lowy FD. Antimicrobial-resistant bacteria in the community setting. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2006;4:36–45. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tayler E, Gregory R, Bloom G, Salama P, Balkhy H. Universal health coverage: An opportunity to address antimicrobial resistance? Lancet Glob. Health. 2019;7:e1480–e1481. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30362-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hernando-Amado S, Coque TM, Baquero F, Martínez JL. Antibiotic resistance: Moving from individual health norms to social norms in one health and global health. Front. Microbiol. 2020;11:1914. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shakya P, et al. Antibiotic resistance among Escherichia coli isolates from stool samples of children aged 3 to 14 years from Ujjain, India. BMC Infect. Dis. 2013;13:477. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nys S, et al. Antibiotic resistance of faecal Escherichia coli from healthy volunteers from eight developing countries. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2004;54:952–955. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.DeFrancesco, A. S., Tanih, N. F., Samie, A., Guerrant, R. L. & Bessong, P. O. Antibiotic resistance patterns and beta-lactamase identification in Escherichia coli isolated from young children in rural Limpopo Province, South Africa: The MAL-ED cohort. South Afr. Med. J. Suid-Afr. Tydskr. Vir Geneeskd.107, 205–214 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Oguttu JW, Veary CM, Picard JA. Antimicrobial drug resistance of Escherichia coli isolated from poultry abattoir workers at risk and broilers on antimicrobials. J. S. Afr. Vet. Assoc. 2008;79:161–166. doi: 10.4102/jsava.v79i4.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hoang PH, et al. Antimicrobial resistance profiles and molecular characterization of Escherichia coli strains isolated from healthy adults in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2017;79:479–485. doi: 10.1292/jvms.16-0639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gulay Z, Bicmen M, Amyes SG, Yulug N. Beta-lactamase patterns and betalactam/clavulanic acid resistance in Escherichia coli isolated from fecal samples from healthy volunteers. J. Chemother. Florence Italy. 2000;12:208–215. doi: 10.1179/joc.2000.12.3.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Riccobono E, et al. Carriage of antibiotic-resistant Escherichia coli among healthy children and home-raised chickens: a household study in a resource-limited setting. Microb. Drug Resist. Larchmt. N. 2012;18:83–87. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2011.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Newman MJ, Seidu A. Carriage of antimicrobial resistant Escherichia coli in adult intestinal flora. West Afr. J. Med. 2002;21:48–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Al-Dweik MR, Shehabi AA. Common antimicrobial resistance phenotypes and genotypes of fecal Escherichia coli isolates from a single family over a 6-month period. Microb. Drug Resist. Larchmt. N. 2009;15:103–107. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2009.0876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Powis, K. M. et al. Cotrimoxazole prophylaxis was associated with enteric commensal bacterial resistance among HIV-exposed infants in a randomized controlled trial, Botswana. J. Int. AIDS Soc.20 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Salinas, L. et al. Diverse commensal Escherichia coli clones and plasmids disseminate antimicrobial resistance genes in domestic animals and children in a semirural community in Ecuador. mSphere4 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Thi Quynh Nhi, L. et al. Excess body weight and age associated with the carriage of fluoroquinolone and third-generation cephalosporin resistance genes in commensal Escherichia coli from a cohort of urban Vietnamese children. J. Med. Microbiol.67, 1457–1466 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 55.Pathak A, et al. Factors associated with carriage of multi-resistant commensal Escherichia coli among postmenopausal women in Ujjain, India. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 2012;44:973–977. doi: 10.3109/00365548.2012.697635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chirindze, L. M. et al. Faecal colonization of E. coli and Klebsiella spp. producing extended-spectrum beta-lactamases and plasmid-mediated AmpC in Mozambican university students. BMC Infect. Dis.18, 244 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Sahoo KC, et al. Geographical variation in antibiotic-resistant Escherichia coli isolates from stool, cow-dung and drinking water. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 2012;9:746–759. doi: 10.3390/ijerph9030746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Purohit, M. R., Lindahl, L. F., Diwan, V., Marrone, G. & Lundborg, C. S. High levels of drug resistance in commensal E. coli in a cohort of children from rural central India. Sci. Rep.9, 6682 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Bartoloni A, et al. High prevalence of acquired antimicrobial resistance unrelated to heavy antimicrobial consumption. J. Infect. Dis. 2004;189:1291–1294. doi: 10.1086/382191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bartoloni A, et al. Patterns of antimicrobial use and antimicrobial resistance among healthy children in Bolivia. Trop. Med. Int. Health. 1998;3:116–123. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1998.00201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Aworh MK, Kwaga J, Okolocha E, Mba N, Thakur S. Prevalence and risk factors for multi-drug resistant Escherichia coli among poultry workers in the Federal Capital Territory, Abuja, Nigeria. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0225379. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0225379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Singh AK, et al. Prevalence of antibiotic resistance in commensal Escherichia coli among the children in rural hill communities of Northeast India. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0199179. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0199179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Phongpaichit S, Liamthong S, Mathew AG, Chethanond U. Prevalence of class 1 integrons in commensal Escherichia coli from pigs and pig farmers in Thailand. J. Food Prot. 2007;70:292–299. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-70.2.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Namboodiri SS, Opintan JA, Lijek RS, Newman MJ, Okeke IN. Quinolone resistance in Escherichia coli from Accra, Ghana. BMC Microbiol. 2011;11:44. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-11-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kalter HD, et al. Risk factors for antibiotic-resistant Escherichia coli carriage in young children in Peru: Community-based cross-sectional prevalence study. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2010;82:879–888. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mamun KZ, Shears P, Hart CA. The prevalence and genetics of resistance to commonly used antimicrobial agents in faecal Enterobacteriaceae from children in Bangladesh. Epidemiol. Infect. 1993;110:447–458. doi: 10.1017/S0950268800050871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.van de Mortel HJ, et al. The prevalence of antibiotic-resistant faecal Escherichia coli in healthy volunteers in Venezuela. Infection. 1998;26:292–297. doi: 10.1007/BF02962250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shanahan PM, et al. The prevalence of antimicrobial resistance in human faecal flora in South Africa. Epidemiol. Infect. 1993;111:221–228. doi: 10.1017/S0950268800056922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lamikanra A, Fayinka ST, Olusanya OO. Transfer of low level trimethoprim resistance in faecal isolates obtained from apparently healthy Nigerian students. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1989;59:275–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1989.tb03124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bartoloni A, et al. Multidrug-resistant commensal Escherichia coli in children, Peru and Bolivia. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2006;12:907–913. doi: 10.3201/eid1206.051258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Purohit M, et al. Antibiotic resistance in an Indian rural community: A ‘one-health’ observational study on commensal coliform from humans, animals, and water. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 2017;14:386. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14040386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pallecchi L, et al. Quinolone resistance in absence of selective pressure: The experience of a very remote community in the Amazon forest. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2012;6:e1790. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G. & for the PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ339, b2535–b2535 (2009). [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 74.Storberg V. ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Africa—A non-systematic literature review of research published 2008–2012. Infect. Ecol. Epidemiol. 2014;4:20342. doi: 10.3402/iee.v4.20342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hedin A, Källestål C. Knowledge-Based Public Health Work Part 2. Stockholm: National Institute of Public Health; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Qiu J, et al. Molecular and phenotypic characteristics of Escherichia coli isolates from farmed minks in Zhucheng, China. BioMed Res. Int. 2019;2019:3917841. doi: 10.1155/2019/3917841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Roca I, et al. The global threat of antimicrobial resistance: Science for intervention. New Microbes New Infect. 2015;6:22–29. doi: 10.1016/j.nmni.2015.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chokshi A, Sifri Z, Cennimo D, Horng H. Global contributors to antibiotic resistance. J. Glob. Infect. Dis. 2019;11:36–42. doi: 10.4103/jgid.jgid_110_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Iskandar, K. et al. Drivers of antibiotic resistance transmission in low- and middle-income countries from a ‘one health’ perspective-A review. Antibiot. Basel Switz.9 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 80.Nadimpalli M, et al. Combating global antibiotic resistance: Emerging one health concerns in lower- and middle-income countries. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018;66:963–969. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pormohammad A, Nasiri MJ, Azimi T. Prevalence of antibiotic resistance in Escherichia coli strains simultaneously isolated from humans, animals, food, and the environment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect. Drug Resist. 2019;12:1181–1197. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S201324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mbanga J, Dube S, Munyanduki H. Prevalence and drug resistance in bacteria of the urinary tract infections in Bulawayo province, Zimbabwe. East Afr. J. Public Health. 2010;7:229–232. doi: 10.4314/eajph.v7i3.64733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Guyatt, G. H. et al. GRADE guidelines: 7. Rating the quality of evidence-inconsistency. J. Clin. Epidemiol.64, 1294–1302 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 84.Iorio A, et al. Use of GRADE for assessment of evidence about prognosis: Rating confidence in estimates of event rates in broad categories of patients. BMJ. 2015;350:h870. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.World Health Organization. Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance. (2015). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 86.Cooke P, et al. What is ‘antimicrobial resistance’ and why should anyone make films about it? Using ‘participatory video’ to advocate for community-led change in public health. New Cine. J. Contemp. Film. 2020;17:85–107. doi: 10.1386/ncin_00006_1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Okba, N. M. A. et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2-specific antibody responses in coronavirus disease 2019 patients. Emerg. Infect. Dis.26 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 88.Retsas S. Clinical trials and the COVID-19 pandemic. Hell. J. Nucl. Med. 2020;23:4–5. doi: 10.1967/s002449912014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hashem AM, et al. Therapeutic use of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in COVID-19 and other viral infections: A narrative review. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Li Z, et al. Rapid review for the anti-coronavirus effect of remdesivir. Drug Discov. Ther. 2020;14:73–76. doi: 10.5582/ddt.2020.01015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Department of Biotechnology, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan et al. COVID-19: Review of epidemiology and potential treatments against 2019 novel coronavirus. Discoveries. 10.15190/d.2020.5 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 92.Poland GA. SARS-CoV-2: A time for clear and immediate action. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020;20:531–532. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30250-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Meo SA, Klonoff DC, Akram J. Efficacy of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in the treatment of COVID-19. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2020;24:4539–4547. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202004_21038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mitjà O, Clotet B. Use of antiviral drugs to reduce COVID-19 transmission. Lancet Glob. Health. 2020;8:e639–e640. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30114-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Morens DM, Taubenberger JK, Fauci AS. Predominant role of bacterial pneumonia as a cause of death in pandemic influenza: Implications for pandemic influenza preparedness. J. Infect. Dis. 2008;198:962–970. doi: 10.1086/591708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Bonten MJM, Prins JM. Antibiotics in pandemic flu. BMJ. 2006;332:248–249. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7536.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Reardon S. Antibiotic treatment for COVID-19 complications could fuel resistant bacteria. Science. 2020 doi: 10.1126/science.abc2995. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z. & Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev.5 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 99.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 16. (2019).

- 100.The System for the Unified Management, Assessment and Review of Information (SUMARI). (Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI)).

- 101.Nyaga VN, Arbyn M, Aerts M. Metaprop: A Stata command to perform meta-analysis of binomial data. Arch. Public Health. 2014;72:39. doi: 10.1186/2049-3258-72-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data related to the manuscript is available upon request to corresponding author.