Abstract

Objective:

To examine whether bedtime is associated with usual sleep duration and eating behaviour among adolescents, emerging adults and young adults.

Design:

Cross-sectional multivariable regression models, stratified by developmental stage, to examine: (1) association between bedtime and sleep duration and (2) associations between bedtime and specific eating behaviours at each developmental period, controlling for sleep duration. All models adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics, depressive symptoms and screen time behaviours.

Setting:

National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health, waves I–IV, USA.

Participants:

A national probability sample surveyed in adolescence (aged 12–18 years, wave I: 1994–1995, n 13 048 and wave II: 1996, n 9438), emerging adulthood (aged 18–24 years, wave III: 2001–2002, n 9424) and young adulthood (aged 24–34 years, wave IV: 2008, n 10 410).

Results:

Later bedtime was associated with shorter sleep duration in all developmental stages, such that a 1-h delay in bedtime was associated with 14–33 fewer minutes of sleep per night (Ps < 0·001). Later bedtime was also associated with lower odds of consuming healthier foods (i.e. fruits, vegetables; range of adjusted OR (AOR), 0·82–0·93, Ps < 0·05) and higher odds of consuming less healthy foods and beverages (i.e. soda, pizza, desserts and sweets; range of AOR, 1·07–1·09, Ps < 0·05). Later bedtime was also associated with more frequent fast-food consumption and higher sugar-sweetened beverage consumption (Ps < 0·05).

Conclusions:

Later bedtime was associated with shorter sleep duration and less healthy eating behaviours. Bedtime may be a novel behaviour to address in interventions aiming to improve sleep duration and dietary intake.

Keywords: Sleep, Bedtime, Eating behaviours, Diet, Obesity

More than two-thirds of adolescents(1,2) and one-third of adults(3) do not get the recommended amount of sleep. Poor sleep behaviours increase the risk for a variety of negative outcomes, including poor dietary quality(4–16) and obesity(17–20). Although research has traditionally focused on sleep duration as a key contributor to poor diet and diet-related chronic diseases, there is growing interest in understanding the role of sleep timing, in particular late bedtime(16,21–24). Later bedtime could affect dietary behaviours and diet-related health outcomes through several pathways. For example, later bedtimes may be a driver of shorter sleep duration: individuals who go to bed later may not be able to compensate by sleeping later the next morning due to work, school and social schedules(25,26). In turn, shorter sleep duration has been associated with worse dietary quality(4–16). Later bedtime may also worsen dietary quality independently of its effects on sleep duration(23), as eating late at night is associated with higher energetic intake and lower dietary quality compared with eating at other times of day(16,27,28).

While evidence suggests that later bedtime could contribute to both shorter sleep duration and less-healthy dietary choices, these questions remain understudied. Research has not investigated whether later bedtime is associated with shorter sleep duration. Likewise, only a handful of studies have examined the relationship between bedtime and dietary behaviours in adolescents(23,29–31) or adults(28,32,33), and none has been conducted in probability samples of the US population. These relationships are particularly important to assess in adolescence, emerging adulthood and young adulthood, as these are three key developmental stages for changing sleep patterns(34) and for the development of dietary behaviours and obesity(35–38). Understanding these associations will shed light on whether sleep timing is a potentially promising target for interventions aiming to improve sleep duration, dietary quality and weight.

To address these gaps, we examined cross-sectional associations between bedtime, sleep duration and eating behaviours using a large national probability sample followed in adolescence, emerging adulthood and young adulthood. Our objectives were to: (1) investigate the association between usual bedtime and sleep duration and (2) examine the association between usual bedtime and eating behaviours, independent of sleep duration. We examined cross-sectional associations within development stages, rather than longitudinal associations across these stages, because sleep behaviours are expected to exert relatively immediate impacts on eating behaviours. We hypothesised that: (1) later bedtimes would be associated with shorter sleep duration, and (2) later bedtimes would independently be associated with less healthy eating behaviours.

Methods

Study sample

We used data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health), a nationally representative sample of approximately 20 000 individuals recruited from middle and high schools in 1994–1995 and followed into adulthood(39). We used data from wave I (collected in 1994–1995), wave II (1996), wave III (2001–2002) and wave IV (2008). Wave V did not assess sleep timing.

We examined participants in three developmental stages: adolescence (waves I and II, including participants age ≥12 and ≤18 years), emerging adulthood (wave III, age >18 and ≤24 years) and young adulthood (wave IV, age >24 and ≤34 years) (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Figs. 1–4), following previous studies(40).

Measures

Usual bedtime

The main exposure variable was participants’ self-reported usual bedtime. In waves I and II, participants reported their usual bedtime on ‘weeknights’ during the school year (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 1 provides details on key study variables). In waves III and IV, participants reported their usual bedtimes for days when they go to work, school or similar activities (‘weekdays’) and for days when they do not have to wake up at a certain time (‘weekends’). We calculated a weighted average of these variables, following previous studies(41,42). In all waves, we converted bedtimes to decimal hours after 12.00 hours (e.g. we coded a bedtime of 21.30 hours as 9·5), such that larger values indicated later bedtime.

Usual sleep duration

In waves I and II, participants self-reported usual sleep duration in hours/night. In waves III and IV, participants reported their usual bedtime and wake time for weekdays and weekends, as described above. We used responses to those items to calculate usual sleep duration in decimal hours (e.g. 30 min equals 0·5 decimal hours), again calculating a weighted average of sleep duration on weekdays and weekends.

Eating behaviours

We examined participants’ self-reported eating behaviours (online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 1). Different behaviours were assessed in each wave; for each wave, we identified eating behaviours that could be easily defined as ‘healthier’ or ‘less healthy.’ In wave I, data were available on whether the participant had consumed fruits, vegetables and sweets in the past day (coded as yes/no). In wave II, we examined consumption of fruits, vegetables, soda, pizza, desserts and sweets, and French fries in the past day (coded as yes/no), as well as on the frequency of fast-food consumption (days in past week ate fast food). In wave III, we examined frequency of fast-food consumption (days in past week ate fast food). Finally, in wave IV, we examined frequency of fast-food consumption (times in past week ate fast food) and amount of sugar-sweetened beverage consumption (number of sugar-sweetened beverages consumed in the past week).

Covariates

Covariates included potential confounders of the relationship between bedtime, sleep duration and eating behaviours, including sociodemographic characteristics (e.g. age, parental education and income to reflect socio-economic status, nativity), screen time behaviours and depressive symptoms(12,18,23,29–32) (online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 1).

Statistical analysis

Analytic samples included participants with complete information on key variables and valid sampling weights. To reduce the influence of outliers, we decided a priori to remove outlying observations with implausible values on sleep duration and bedtime, excluding from analyses respondents further than 2·576 sd from sample means on these variables (online supplementary material, Supplemental Figs. 1 through 4), similar to previous studies(40). Participants excluded from analysis due to missing or extreme data were similar to included participants in their average sleep duration, bedtime and eating behaviours, but differed slightly in some demographic characteristics (online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 2).

To evaluate the relationship between bedtime and sleep duration within each developmental stage, we estimated multivariable ordinary least squares models stratified by developmental stage, regressing sleep duration on bedtime and covariates. To examine the relationship between bedtime and each eating behaviour within each developmental stage, we regressed each eating behaviour variable on bedtime, stratifying by developmental stage and controlling for both sleep duration and covariates. We used logistic regression for dichotomous eating behaviour variables (e.g. ate fruit yesterday) and negative binomial regression for count variables (e.g. fast food times/week). We report adjusted OR and unstandardised coefficients/marginal effects (Bs). All analyses accounted for Add Health’s complex sampling design.

We conducted analyses using Stata version 15.1 (StataCorp LLC). The University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board granted human subjects’ research approval for this study.

Results

The analytic samples included 9427–13 048 individuals per wave (Table 1). Average sleep duration increased somewhat across waves. Average bedtime was similar in waves I, II and IV (22.30–22.42 hours), and later in wave III (24.06 hours).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics by developmental stage, National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health*

| Adolescents ≥12 and ≤18 years | Emerging adults >18 and ≤24 years | Young adults >24 and ≤34 years | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wave I(n 13 048) | Wave II(n 9438) | Wave III(n 9427) | Wave IV(n 10 410) | |||||

| Characteristics | Mean | sd | Mean | sd | Mean | sd | Mean | sd |

| Sleep duration (h) | 7·8 | 1·2 | 7·7 | 1·2 | 8·1 | 1·5 | 8·9 | 2·0 |

| Bedtime, decimal hours after noon | 10·7 | 1·2 | 10·5 | 1·0 | 12·1 | 1·8 | 10·5 | 2·5 |

| Eating behaviours (%)† | ||||||||

| Ate fruit yesterday | 79 | 66 | – | – | ||||

| Ate vegetables yesterday | 69 | 80 | – | – | ||||

| Ate sweets/desserts yesterday | 55 | 65 | – | – | ||||

| Drank soda yesterday | – | 71 | – | – | ||||

| Ate pizza yesterday | – | 26 | – | – | ||||

| Ate French fries yesterday | – | 33 | – | – | ||||

| Fast food, number of days in last week | – | 2·1 | 1·7 | 2·4 | 2·0 | – | ||

| Fast food, number of times in last week | – | – | – | 2·4 | 3·2 | |||

| SSB, number of drinks in last week | – | – | – | 12·3 | 13·9 | |||

| Age (years) | 15·3 | 1·7 | 15·7 | 1·4 | 21·5 | 1·6 | 28·2 | 1·8 |

| Female (%) | 49 | 50 | 49 | 49 | ||||

| Race/ethnicity (%) | ||||||||

| White | 69 | 69 | 69 | 69 | ||||

| Hispanic | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | ||||

| Black | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | ||||

| Other | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | ||||

| Born in the USA (%) | 95 | 95 | 95 | 97 | ||||

| Parental education (%) | ||||||||

| Less than a high school diploma | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | ||||

| High school diploma or GED | 26 | 26 | 25 | 27 | ||||

| Some college | 32 | 32 | 31 | 32 | ||||

| College or more | 31 | 32 | 33 | 32 | ||||

| Parental income, logged | 3·49 | 0·96 | 3·48 | 1·0 | 3·50 | 0·97 | 3·49 | 0·97 |

| Usual television viewing (%)ठ| ||||||||

| Low (0–14 h/week) | 50 | 54 | 54 | 68 | ||||

| Medium (15–28 h/week) | 28 | 27 | 28 | 22 | ||||

| High (≥29 h/week) | 22 | 19 | 17 | 9 | ||||

| Usual video/computer games (%)§‖ | ||||||||

| Low (0–14 h/week) | 96 | 96 | 91 | 94 | ||||

| Medium (15–28 h/week) | 3 | 3 | 6 | 4 | ||||

| High (≥29 h/week) | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | ||||

| Depressive symptoms¶ | 7·0 | 3·8 | 7·0 | 3·8 | 6·2 | 3·8 | 7·0 | 3·8 |

Means, sd and % adjusted for complex survey features of Add Health. Eating behaviours listed as ‘–’ were not assessed in this survey wave.

See online Supplementary material, Supplemental Table 1 for information on measurement of eating behaviours in each wave.

Participants reported on the usual number of hours per week they spent watching television during the past 30 d.

We trichotomised screen time variables using the categories reported in Kruger et al.(12).

Participants reported on the usual number of hours per week they spent playing video or computer games during the past 30 d.

Sum score on the nine items from Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale(55) that were assessed in all four waves. Score on each item ranged from 0 to 3 yielding a possible sum scores of 0–27, where higher scores indicate more depressive symptoms.

In all developmental stages, later bedtime was associated with shorter sleep duration, independently of demographic characteristics, screen time behaviours and depressive symptoms (range of Bs: –0·55 to –0·23 h/night, all Ps < 0·001, Table 2). Associations between bedtime and sleep duration significantly differed across the four waves (adjusted Wald test F (3,126) = 82·12, P < 0·001). The negative association was strongest among young adults, for whom going to bed 1 h later was associated with a reduction in usual sleep duration of 0·55 h (~33 min) per night.

Table 2.

Association of later bedtime with usual sleep duration, by developmental stage, National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health*

| Adolescents ≥12 and ≤18 years | Emerging adults >18 and ≤24 years | Young adults >24 and ≤34 years | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wave I (n 13 048) | Wave II (n 9438) | Wave III (n 9427) | Wave IV (n 10 410) | ||||||||||

| B | 95 % CI | P | B | 95 % CI | P | B | 95 % CI | P | B | 95 % CI | P | P for differences across waves† | |

| Bedtime, decimal hours after noon | –0·23 | –0·27, –0·19 | <0·001 | –0·50 | –0·53, –0·46 | <0·001 | –0·27 | –0·31, –0·24 | <0·001 | –0·55 | –0·58, –0·52 | <0·001 | <0·001 |

Table shows the association between bedtime and usual sleep duration in hours/night from regressions of sleep duration on bedtime, controlling for age, sex, race/ethnicity, nativity, parental educational attainment, logged parental income, usual time spent watching television, usual time spent playing video/computer games and depressive symptoms. Bedtime was calculated in decimal hours after 12.00 hours, such that larger values indicate later bedtimes. Bs reported are unstandardised regression coefficients. All analyses accounted for complex survey features of Add Health.

P value reported is for an adjusted Wald test examining whether all coefficients were equal in seemingly unrelated estimation, F(3,126) = 82·12.

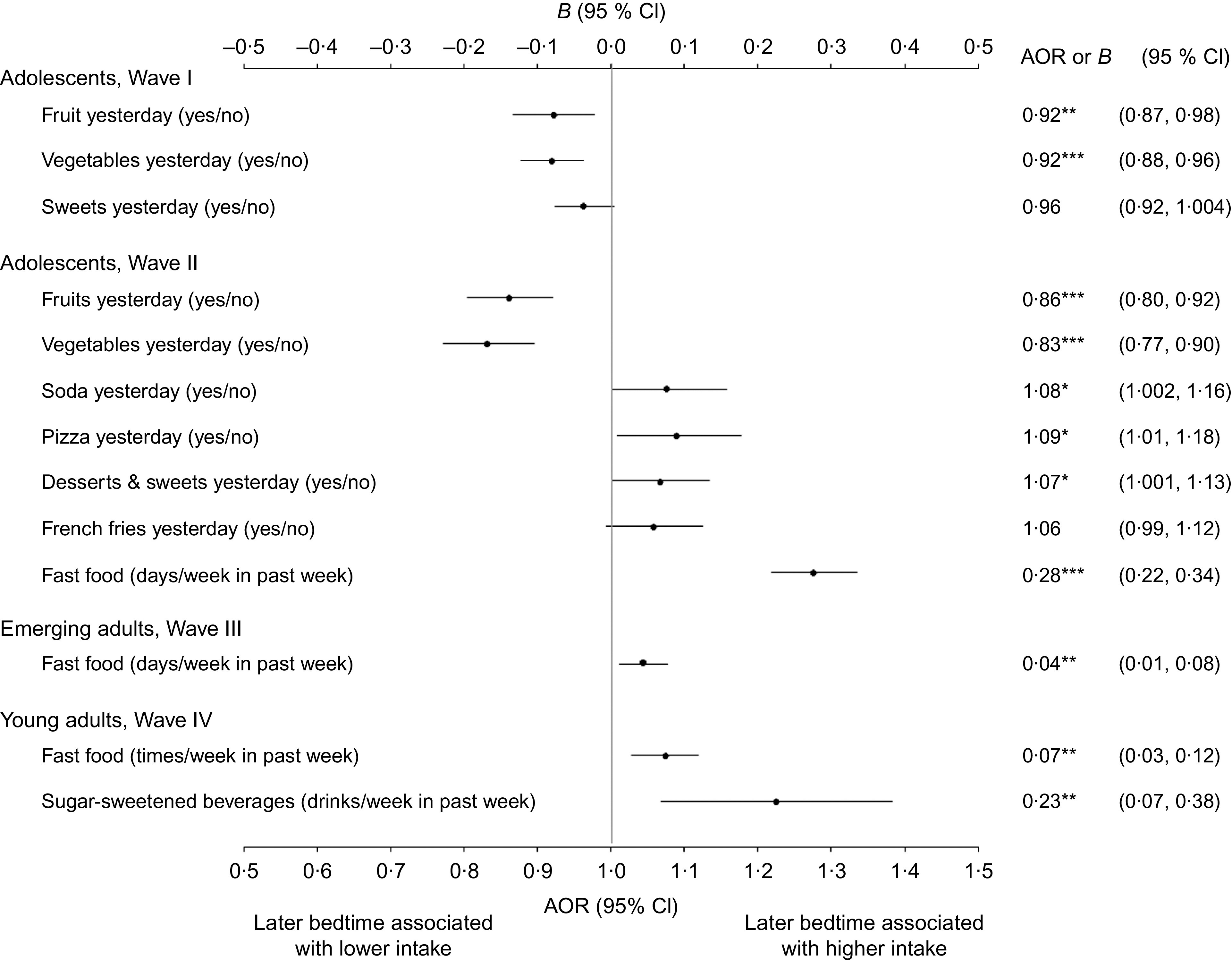

Generally, later bedtime was also associated with less healthy eating behaviours in each development stage, even after controlling for usual sleep duration (Fig. 1). Of the thirteen associations tested, all but two were statistically significant (Ps < 0·05) and all the significant associations were in the expected direction, with later bedtime being associated with less healthy eating behaviours. Only eating sweets yesterday as reported by adolescents in wave 1 (adjusted OR: 0·06, P = 0·08) and eating French fries yesterday as reported by adolescents in wave 2 (adjusted OR: 1·06, P = 0·08) were not significantly associated with bedtime, though the associations were in the expected directions. Stronger associations were seen between bedtime and consumption of fruits and vegetables in adolescents, bedtime and the frequency of fast-food consumption in adolescents, and bedtime and sugar-sweetened beverage consumption in young adults.

Fig. 1.

Associations of later bedtime with eating behaviours, controlling for sleep duration, National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health. Figure shows associations between bedtime and eating behaviours. Bedtime was calculated in decimal hours after 12.00 hours, such that larger values indicate later bedtimes. Figure shows unstandardised regression coefficients (Bs) for continuous outcomes (top horizontal axis) and adjusted OR (AOR) for binary outcomes (bottom horizontal axis), controlling for usual sleep duration, age, sex, race/ethnicity, nativity, parental educational attainment, logged parental income, usual time spent watching television, usual time spent playing video/computer games and depressive symptoms. All analyses accounted for complex survey features of Add Health. *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01, ***P < 0·001

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study with a large national sample, bedtime was negatively associated with sleep duration among adolescents, emerging adults and young adults. Going to bed 1 h later was associated with 14–33 fewer minutes of usual sleep duration per night. This reduction could be clinically meaningful: previous studies have found that a 1-h reduction in usual sleep duration is associated with an 80 % increase in odds of obesity among adolescents(43) and a 0·35 kg/m2 increase in BMI among adults(18).

Across developmental stages, later bedtimes were generally associated with reporting lower consumption of healthier foods and higher consumption of less healthy foods. For example, adolescents who reported later bedtimes had lower odds of fruit and vegetable consumption and higher odds of consuming soda, desserts and pizza. Likewise, later bedtime was associated with greater frequency of fast-food consumption in all developmental stages. These findings are consistent with studies examining bedtime and eating behaviours in non-national samples(23,29,31,32). While some of the observed associations were small, the consistent pattern of results suggests that these small associations could add up to meaningful differences in overall dietary quality and diet-related health outcomes. For example, fruit and vegetable consumption(44) and fast-food intake(45) have been found to be associated with health outcomes such as heart disease and insulin resistance.

Several mechanisms could underlie the observed associations between bedtime and eating behaviours. For example, those who go to bed later may be eating more energy-dense snacks that are convenient for late night eating, contributing to higher energetic intake and lower dietary quality compared with eating during other times of day(16,27,28). Another possibility is that poorer sleep behaviours are a marker for a general profile of riskier behaviours, rather than later bedtime being a driver of less healthy dietary choices, though research on this question is mixed(42,46–49). Additional research should also explore the complex interplay of sleep behaviours, diet, adiposity, and hunger, satiety, and growth hormones(50–52).

Strengths of our study include its use of a large population-based national sample, examination of three developmental stages critical to the development of eating behaviours and obesity(35–38), and inclusion of important potential confounders in analyses, particularly screen time(16) and depressive symptoms(53). By examining the cross-sectional relationships over three developmental periods, we demonstrate that the behaviours co-vary during each developmental stage and that some behavioural patterns are stable across developmental stages.

Limitations of our study include the inconsistency of eating behaviour questions used across the four waves and our inability to examine overall dietary quality. Another limitation is that sleep behaviours were self-reported. While self-reported and objectively measured sleep variables are significantly correlated(54), future research should examine these associations using gold standard measures of sleep whenever possible. Third, we used complete case analysis to account for missing data. While participants included in analysis had similar sleep and eating behaviours as those excluded from analysis, we cannot rule out sample selection bias. Finally, we cannot rule out alternate explanations for the observed associations, including residual confounding and reverse causality (i.e. eating certain foods causes individuals to go to bed later).

Conclusions

In a national probability sample, later bedtime was associated with shorter sleep duration during adolescence, emerging adulthood and young adulthood. Further, later bedtime was generally associated with less healthy eating behaviours, even after controlling for sleep duration. Given the cross-sectional design of this study, future research using longitudinal and experimental designs is needed to clarify the relationships between bedtime, sleep duration and eating behaviours. If bedtime is causally related to eating behaviours and sleep duration, encouraging earlier bedtimes could be a promising strategy to incorporate into interventions aiming to improve eating behaviours, increase sleep duration or prevent obesity.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors thank the Add Health study team at the University of North Carolina. Financial support: General support and training support for A.H.G. were provided by the Carolina Population Center (P2C HD050924 and T32 HD007168), and training support for R.L.S. was provided by the Carolina Consortium for Human Development (T32 HD07376). The funders had no role in the study design; collection, analysis or interpretation of the data; writing of this report; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Conflicts of interest: None. Authorship: A.H.G. conceptualised the study, analysed the data, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. R.L.S. contributed to data preparation analysis, provided intellectual input on study design and interpretation, and critically reviewed the manuscript. L.A.L. provided intellectual input on study design and interpretation and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final content. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by the University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board. This study used de-identified secondary data.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980020002050.

click here to view supplementary material

References

- 1.Eaton DK, McKnight-Eily LR, Lowry R et al. (2010) Prevalence of insufficient, borderline, and optimal hours of sleep among high school students: United States, 2007. J Adolescent Health 46, 399–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wheaton AG, Jones SE, Cooper AC et al. (2018) Short sleep duration among middle school and high school students: United States, 2015. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 67, 85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu Y (2016) Prevalence of healthy sleep duration among adults: United States, 2014. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 65, 137–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Córdova FV, Barja S & Brockmann PE (2018) Consequences of short sleep duration on the dietary intake in children: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Sleep Med Rev 42, 68–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kjeldsen JS, Hjorth MF, Andersen R et al. (2013) Short sleep duration and large variability in sleep duration are independently associated with dietary risk factors for obesity in Danish school children. Int J Obes 38, 32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaput J-P, Tremblay MS, Katzmarzyk PT et al. (2018) Sleep patterns and sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among children from around the world. Public Health Nutr 21, 2385–2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sampasa-Kanyinga H, Hamilton HA & Chaput J-P (2018) Sleep duration and consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and energy drinks among adolescents. Nutrition 48, 77–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Franckle RL, Falbe J, Gortmaker S et al. (2015) Insufficient sleep among elementary and middle school students is linked with elevated soda consumption and other unhealthy dietary behaviors. Prev Med 74, 36–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rangan A, Zheng M, Olsen NJ et al. (2017) Shorter sleep duration is associated with higher energy intake and an increase in BMI z-score in young children predisposed to overweight. Int J Obes 42, 59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weiss A, Xu F, Storfer-Isser A et al. (2010) The association of sleep duration with adolescents’ fat and carbohydrate consumption. Sleep 33, 1201–1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martinez SM, Tschann JM, Butte NF et al. (2016) Short sleep duration is associated with eating more carbohydrates and less dietary fat in Mexican American children. Sleep 40, zsw057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kruger AK, Reither EN, Peppard PE et al. (2014) Do sleep-deprived adolescents make less-healthy food choices? Br J Nutr 111, 1898–1904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cespedes EM, Hu FB, Redline S et al. (2016) Chronic insufficient sleep and diet quality: contributors to childhood obesity. Obesity 24, 184–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prather AA, Leung CW, Adler NE et al. (2016) Short and sweet: associations between self-reported sleep duration and sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among adults in the United States. Sleep Health 2, 272–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dashti HS, Ordovás JM, Jacques PF et al. (2015) Short sleep duration and dietary intake: epidemiologic evidence, mechanisms, and health implications. Adv Nutr 6, 648–659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chaput J-P (2014) Sleep patterns, diet quality and energy balance. Physiol Behav 134, 86–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Magee L & Hale L (2012) Longitudinal associations between sleep duration and subsequent weight gain: a systematic review. Sleep Med Rev 16, 231–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cappuccio FP, Taggart FM, Kandala N-B et al. (2008) Meta-analysis of short sleep duration and obesity in children and adults. Sleep 31, 619–626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen X, Beydoun MA & Wang Y (2008) Is sleep duration associated with childhood obesity? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity 16, 265–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li L, Zhang S, Huang Y et al. (2017) Sleep duration and obesity in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. J Paed Child Health 53, 378–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fleig D & Randler C (2009) Association between chronotype and diet in adolescents based on food logs. Eat Behav 10, 115–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thind H, Davies SL, Lewis T et al. (2015) Does short sleep lead to obesity among children and adolescents? Current understanding and implications. Am J Lifestyle Med 9, 428–437. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Golley RK, Maher CA, Matricciani L et al. (2013) Sleep duration or bedtime? Exploring the association between sleep timing behaviour, diet and BMI in children and adolescents. Int J Obes 37, 546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jarrin DC, McGrath JJ & Drake CL (2013) Beyond sleep duration: distinct sleep dimensions are associated with obesity in children and adolescents. Int J Obes 37, 552–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gibson M & Shrader J (2018) Time use and labor productivity: the returns to sleep. Rev Econ Stat 100, 783–798. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giuntella O & Mazzonna F (2016) If You Don’t Snooze You Lose Health and Gain Weight: Evidence from a Regression Discontinuity Design. Bonn, Germany: IZA. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spaeth AM, Dinges DF & Goel N (2013) Effects of experimental sleep restriction on weight gain, caloric intake, and meal timing in healthy adults. Sleep 36, 981–990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baron KG, Reid KJ, Kern AS et al. (2011) Role of sleep timing in caloric intake and BMI. Obesity 19, 1374–1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thellman KE, Dmitrieva J, Miller A et al. (2017) Sleep timing is associated with self-reported dietary patterns in 9- to 15-year-olds. Sleep Health 3, 269–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adamo KB, Wilson S, Belanger K et al. (2013) Later bedtime is associated with greater daily energy intake and screen time in obese adolescents independent of sleep duration. J Sleep Disord Ther 2, 2167–0277. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Agostini A, Lushington K, Kohler M et al. (2018) Associations between self-reported sleep measures and dietary behaviours in a large sample of Australian school students (n = 28,010). J Sleep Res 27, e12682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ogilvie RP, Lutsey PL, Widome R et al. (2018) Sleep indices and eating behaviours in young adults: findings from Project EAT. Public Health Nutr 21, 689–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mossavar-Rahmani Y, Weng J, Wang R et al. (2017) Actigraphic sleep measures and diet quality in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos Sueno ancillary study. J Sleep Res 26, 739–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maslowsky J & Ozer EJ (2014) Developmental trends in sleep duration in adolescence and young adulthood: evidence from a National United States sample. J Adoles Health 54, 691–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lawlor DA & Chaturvedi N (2006) Treatment and prevention of obesity: are there critical periods for intervention? Int J Epidemiol 35, 3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dietz WH (1994) Critical periods in childhood for the development of obesity. Am J Clin Nutr 59, 955–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nelson MC, Story M, Larson NI et al. (2008) Emerging adulthood and college-aged youth: an overlooked age for weight-related behavior change. Obesity 16, 2205–2211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alberga A, Sigal R, Goldfield G et al. (2012) Overweight and obese teenagers: why is adolescence a critical period? Pediatr Obes 7, 261–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harris K, Halpern C, Whitsel E et al. (n.d.) The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health: Research Design. The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health. http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/design (accessed March 2018).

- 40.Sokol RL, Grummon AH & Lytle LA (2020) Sleep duration and body mass: direction of the associations from adolescence to young adulthood. Int J Obes 44, 852–856. doi: 10.1038/s41366-019-0462-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krueger PM, Reither EN, Peppard PE et al. (2015) Cumulative exposure to short sleep and body mass outcomes: a prospective study. J Sleep Res 24, 629–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Larson N, Dewolfe J, Story M et al. (2014) Adolescent consumption of sports and energy drinks: linkages to higher physical activity, unhealthy beverage patterns, cigarette smoking, and screen media use. J Nutr Educ Behav 46, 181–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gupta NK, Mueller WH, Chan W et al. (2002) Is obesity associated with poor sleep quality in adolescents? Am J Hum Biol 14, 762–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aune D, Giovannucci E, Boffetta P et al. (2017) Fruit and vegetable intake and the risk of cardiovascular disease, total cancer and all-cause mortality: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Int J Epidemiol 46, 1029–1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pereira M, Kartashov A, Ebbeling C et al. (2005) Fast-food habits, weight gain, and insulin resistance (the CARDIA study): 15-year prospective analysis. Lancet 365, 36–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dumuid D, Olds T, Lewis LK et al. (2017) Health-related quality of life and lifestyle behavior clusters in school-aged children from 12 countries. J Pediatr 183, 178–183.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ding D, Rogers K, Macniven R et al. (2014) Revisiting lifestyle risk index assessment in a large Australian sample: should sedentary behavior and sleep be included as additional risk factors? Preven Med 60, 102–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nuutinen T, Lehto E, Ray C et al. (2017) Clustering of energy balance-related behaviours, sleep, and overweight among Finnish adolescents. Int J Public Health 62, 929–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kaar JL, Schmiege SJ, Vadiveloo M et al. (2018) Sleep duration mediates the relationship between health behavior patterns and obesity. Sleep Health 4, 442–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Beccuti G & Pannain S (2011) Sleep and obesity. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 14, 402–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Prinz P (2004) Sleep, appetite, and obesity – what is the link? PLoS Med 1, e61. Public Library of Science. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Spiegel K, Tasali E, Leproult R et al. (2009) Effects of poor and short sleep on glucose metabolism and obesity risk. Nat Rev Endocrinol 5, 253–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chang PP, Ford DE, Mead LA et al. (1997) Insomnia in young men and subsequent depression: the Johns Hopkins Precursors Study. Am J Epidemiol 146, 105–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lauderdale DS, Knutson KL, Yan LL et al. (2008) Self-reported and measured sleep duration: how similar are they? Epidemiology 19, 838–845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eaton WW, Smith C, Ybarra M et al. (2004) Center for epidemiologic studies depression scale: review and revision (CESD and CESD-R). In The Use of Psychological Testing for Treatment Planning and Outcomes Assessment: Instruments for Adults, pp. 363–377 [Maruish ME, editor]. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980020002050.

click here to view supplementary material