Abstract

Brain disorders include neurodegenerative diseases (NDs) with different conditions that primarily affect the neurons and glia in the brain. However, the risk factors and pathophysiological mechanisms of NDs have not been fully elucidated. Homeostasis of intracellular Ca2+ concentration and intracellular pH (pHi) is crucial for cell function. The regulatory processes of these ionic mechanisms may be absent or excessive in pathological conditions, leading to a loss of cell death in distinct regions of ND patients. Herein, we review the potential involvement of transient receptor potential (TRP) channels in NDs, where disrupted Ca2+ homeostasis leads to cell death. The capability of TRP channels to restore or excite the cell through Ca2+ regulation depending on the level of plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPase (PMCA) activity is discussed in detail. As PMCA simultaneously affects intracellular Ca2+ regulation as well as pHi, TRP channels and PMCA thus play vital roles in modulating ionic homeostasis in various cell types or specific regions of the brain where the TRP channels and PMCA are expressed. For this reason, the dysfunction of TRP channels and/or PMCA under pathological conditions disrupts neuronal homeostasis due to abnormal Ca2+ and pH levels in the brain, resulting in various NDs. This review addresses the function of TRP channels and PMCA in controlling intracellular Ca2+ and pH, which may provide novel targets for treating NDs.

Keywords: TRP channels, brain pathology, neurodegenerative diseases, calcium, pH, homeostasis, neuron

Introduction

Calcium (Ca2+) is a second messenger involved in numerous signal transduction pathways, including cell proliferation, cell growth, neuronal excitability, metabolism, apoptosis, and differentiation (Berridge et al., 2000; Gleichmann and Mattson, 2011; Maklad et al., 2019). Intracellular Ca2+ has a complex role in brain signaling and regulates brain physiology to maintain neuronal integrity (Marambaud et al., 2009; Bezprozvanny, 2010; Kawamoto et al., 2012). Ca2+ influx across the plasma membrane is important for fundamental brain functions which are mainly mediated by glutamate receptor channels, voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, sodium-calcium exchanger, and transient receptor potential (TRP) channels (Bezprozvanny, 2010; Cross et al., 2010; Gees et al., 2010; Cuomo et al., 2015; Kumar et al., 2016). Thus, Ca2+ signaling affects a variety of neuronal functions in diverse physiological roles, and Ca2+ must be tightly regulated to avoid uncontrolled responses that can lead to pathological conditions (Kumar et al., 2016). However, sustained increase in Ca2+ influx induces endoplasmic reticulum stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and various proteases, resulting in neuronal cell death (Bezprozvanny, 2010; Kawamoto et al., 2012). Indeed, impaired cell function caused by reactive nitrogen (oxygen) species and abnormal pH homeostasis also underpins the pathophysiology of neurodegenerative diseases (NDs) (Piacentini et al., 2008; Bezprozvanny, 2010; Gleichmann and Mattson, 2011; Zundorf and Reiser, 2011; Harguindey et al., 2017, 2019; Popugaeva et al., 2017). In particular, the maintenance of Ca2+ and pH levels is involved in a variety of NDs, including Alzheimer's disease (AD), Parkinson's disease (PD), Huntington's disease (HD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and age-related disorders (Harguindey et al., 2007; Kumar et al., 2009; Smaili et al., 2009; Ruffin et al., 2014; Hong et al., 2020; Thapak et al., 2020). Extensive literature indicates that an excessive increase in cytosolic Ca2+ and H+ constitutes both direct and indirect ND-induced processes (Marambaud et al., 2009; Smaili et al., 2009; Bezprozvanny, 2010; Ruffin et al., 2014; Zhao et al., 2016; Harguindey et al., 2017).

TRP channels constitute a large family of membrane Ca2+ channels involved in a wide range of processes including thermoregulation, osmosis, pH, stretch, and chemical signaling (Kaneko and Szallasi, 2014). Functionally, activation of TRP channels influences Ca2+ signaling by allowing Ca2+ to enter the cell (cell depolarization), which may activate voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (Nilius and Owsianik, 2011; Vennekens et al., 2012). TRP channels in neuronal cells regulate voltage-gated Ca2+, K+, and Na+ channels, whereas TRP channel regulation in glial cells results in reduced Ca2+ entry via ORAI by membrane depolarization, or increased Ca2+ influx through the hyperpolarization of the membrane (Gees et al., 2010). In the central nervous system, TRP channels are widely expressed throughout the brain and play an essential role in regulating Ca2+ homeostasis associated with various cellular functions, including synaptic plasticity, synaptogenesis, and synaptic transmission in a specific region of the brain (Venkatachalam and Montell, 2007; Kaneko and Szallasi, 2014; Jardin et al., 2017; Chi et al., 2018; Hong et al., 2020). In addition, TRP subtype channels are expressed simultaneously or separately in neurons and glia, fulfilling critical roles in cell homeostasis, development, neurogenesis, and synaptic plasticity (Vennekens et al., 2012). Several members of the TRP subtype are highly expressed in neurons and glia (Moran et al., 2004; Butenko et al., 2012; Ho et al., 2014; Ronco et al., 2014; Verkhratsky et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2017; Rakers et al., 2017) (Table 1). Thus, diverse TRP channels expressed in the brain are involved in the progression of NDs such as Parkinson's and Alzheimer's. In particular, increased intracellular Ca2+ via TRP channels contributes to various pathophysiological events (Venkatachalam and Montell, 2007; Kaneko and Szallasi, 2014; Moran, 2018; Hong et al., 2020) as well as brain disorders such as AD, PD, stroke, epilepsy, and migraine (Table 1)(Morelli et al., 2013; Kaneko and Szallasi, 2014; Kumar et al., 2016; Moran, 2018; Hong et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020).

Table 1.

A summary of the transient receptor potential (TRP) subtypes found in distribution of central nervous system (CNS) cell types.

| TRP channels | Expression in brain | Expression in glia | Disorders | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRPC subfamily | TRPC1 | - Cerebellum, hippocampus, forebrain - Dopaminergic neuron (Human/mouse) |

Astrocyte, microglia, | NDs, ADs, PD, HD, | Riccio et al., 2002; Bollimuntha et al., 2005, 2006; Selvaraj et al., 2009, 2012; Hong et al., 2015 |

| TRPC3 | - Cerebellum, hippocampus, forebrain - Dopaminergic neuron (Human) |

Astrocyte, | NDs, ADs, PDs | Rosker et al., 2004; Wu et al., 2004; Yamamoto et al., 2007; Mizoguchi et al., 2014 | |

| TRPC4 | Cerebellum, hippocampus, forebrain | Astrocyte, | Epilepsy | Wang et al., 2007; Wu et al., 2008; Von Spiczak et al., 2010; Tai et al., 2011 | |

| TRPC5 | - Cerebellum, forebrain - Hippocampus (mouse) |

Astrocyte, | NDs, PDs, Epilepsy | Shin et al., 2010; Tai et al., 2011; Kaczmarek et al., 2012 | |

| TRPC6 | Cerebellum, hippocampus, forebrain, striatum | Astrocyte, microglia | NDs, ADs | Lessard et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2017; Lu et al., 2017 | |

| TRPM subfamily | TRPM2 | - Hippocampus, forebrain - Cerebellum (human), cortex (rat) |

Astrocyte, microglia | NDs, ADs, PDs | Fonfria et al., 2005; Kaneko et al., 2006; Hermosura et al., 2008; Ostapchenko et al., 2015 |

| TRPM7 | - Cerebellum, forebrain, - Hippocampus (human) - cortex (mouse) |

Astrocyte, microglia | NDs, ADs, PDs, Epilepsy | Aarts and Tymianski, 2005; Hermosura et al., 2005; Chen X. et al., 2010; Coombes et al., 2011; Oakes et al., 2019 | |

| TRPV subfamily | TRPV1 | - Basal ganglia, hindbrain Cerebellum - Hippocampus (rat/mouse), |

Astrocyte, microglia | NDs, AD, HD, epilepsy | Lastres-Becker et al., 2003; Kim et al., 2005; Gibson et al., 2008; Li et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2011; Balleza-Tapia et al., 2018 |

| TRPV4 | Cerebellum, hippocampus, | Astrocyte, microglia | NDs, AD, | Auer-Grumbach et al., 2010; Chen D. H. et al., 2010; Landoure et al., 2010; Klein et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2019 | |

| TRPA subfamily | TRPA1 | Cerebellum, hippocampus, | Astrocyte, oligodendrocyte | AD | Shigetomi et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2016; Saghy et al., 2016; Bolcskei et al., 2018 |

PMCA, plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPase; AD, Alzheimer's disease; PD, Parkinson's disease; ND, neurodegenerative disease.

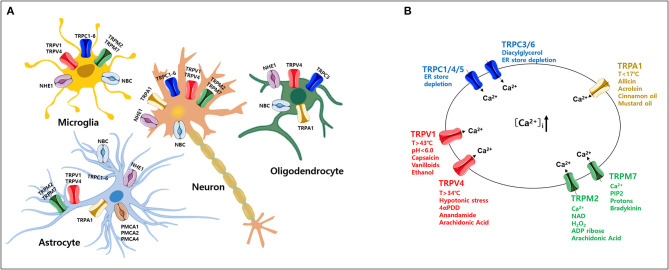

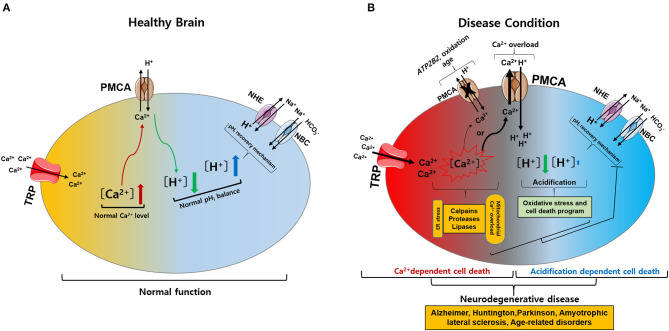

The normal regulation of intracellular Ca2+ levels involves mechanisms that control the specific uptake and extrusion mechanisms across the cell membrane (Kawamoto et al., 2012; Strehler and Thayer, 2018). Ca2+ influx is mediated by several voltage- and ligand-gated channels as well as transporters. Conversely, Ca2+ extrusion is dependent on Ca2+ pumps and Na+/Ca2+ exchangers (Strehler and Thayer, 2018). Among these, plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPases (PMCAs) actively extrude Ca2+ ions out of cells (Boczek et al., 2019). Thus, these pumps are important gatekeepers for maintaining intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis in cells (Stafford et al., 2017; Boczek et al., 2019). However, PMCA dysfunction causes altered Ca2+ homeostasis and leads to a persistent increase in cytosolic Ca2+, which can be neurotoxic and can accelerate the development of NDs and cognitive impairments as the person ages (Strehler and Thayer, 2018; Boczek et al., 2019). In particular, it is possible that the regulation of Ca2+ concentration might be more sensitive in which the cells are expressed both TRP and PMCA in the particular brain region (Figure 1). Thereby, abnormal expression of either TRP or PMCA subtype may be more likely to cause ND than other parts of the brain (Figure 2) (Minke, 2006; Stafford et al., 2017). In addition, PMCA activity is associated with intracellular acidification (Hwang et al., 2011) which is associated with neurological conditions observed among AD patients and other ND patients (Kato et al., 1998; Hamakawa et al., 2004; Mandal et al., 2012; Ruffin et al., 2014; Tyrtyshnaia et al., 2016).

Figure 1.

Expression of various transient receptor potential (TRP) subtypes and calcium (Ca2+) influx by their agonists in the mammalian central nervous system (CNS). (A) Expression profile of various TRP channels, NHE1, and NBC, in mammalian CNS cell types. (B) Ca2+ influx through activation of TRP subtypes by various agonists or activators in the mammalian CNS. TRP, transient receptor potential; PMCA, plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPase; NBC, Na+/ cotransporters; NHE, Na+/H+ exchangers.

Figure 2.

Intracellular calcium (Ca2+) and pH (pHi) signaling by activation of TRP and PMCA in healthy and diseased condition of the brain. (A) Normal physiological function of intracellular Ca2+ and pHi homeostasis. The activation of TRP channels leads to Ca2+ influx into the cytosol. Increased Ca2+ levels are regulated by PMCA. The activation of PMCA can cause acidification. Acidification conditions are mediated by pHi recovery functions regulated by NBC and NHE. (B) Neurodegenerative diseases caused by pathophysiological functions of intracellular Ca2+ and pHi homeostasis. (1) The activation of TRP channels leads to excess Ca2+ influx and overload Ca2+ is maintained due to ATP2B2, oxidation, and age-related downregulation of PMCA: Ca2+-dependent cell death. (2) PMCA overexpression due to cytoplasmic Ca2+ overload cause persistent acidification from inhibition of the pHi recovery mechanism by oxidative stress or cell death program: acidification dependent cell death. Ultimately, abnormal intracellular Ca2+ and pHi levels impair neuronal function, resulting in neurodegenerative diseases. TRP, transient receptor potential; PMCA, plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPase; NBC, Na+/ cotransporters; NHE, Na+/H+ exchangers.

It is crucial to investigate whether increased Ca2+ and (or) acidification are risk factors that affects ND-induced processes (Chesler, 2003; Hwang et al., 2011; Ruffin et al., 2014; Cuomo et al., 2015; Stafford et al., 2017; Boczek et al., 2019). Here, we review the involvement of TRP channels and PMCA in the pathophysiology of NDs.

Brain Disorders

Neurodegenerative Diseases

NDs such as AD, PD, HD, and ALS are age-related conditions characterized by uncontrolled neuronal death in the brain (Hong et al., 2020; Slanzi et al., 2020; Thapak et al., 2020). To date, several studies have reported that NDs are associated with protein aggregation, oxidative stress, inflammation, and abnormal Ca2+ homeostasis (Sprenkle et al., 2017). The impairment of Ca2+ homeostasis is known to result in increased susceptibility to NDs (Kumar et al., 2009; Smaili et al., 2009; Bezprozvanny, 2010; Gleichmann and Mattson, 2011; Kawamoto et al., 2012; Bagur and Hajnoczky, 2017). In particular, this impairment is associated with changes in Ca2+ buffering capacity, deregulation of Ca2+ channel activity, and alteration in other calcium regulatory proteins that occur in some types of neurons and glial cells in certain brain regions (Zundorf and Reiser, 2011; Nikoletopoulou and Tavernarakis, 2012). There is also increased Ca2+ influx mediated by abnormal TRP channel activation (Sawamura et al., 2017). Similarly, Ca2+ extrusion through PMCA has been shown to decrease in aged neurons (Jiang et al., 2012). For this reason, these NDs are associated with Ca2+ channels in neurons and glial cells (astrocytes, microglia, and oligodendrocytes), which are important for neuronal survival, myelin formation, neuronal support, and regulation of local neuron activity (neurons-glial signaling) (Zhang and Liao, 2015; Cornillot et al., 2019; Enders et al., 2020).

Pathophysiological Role of TRP Channels

TRP channels are non-selective, Ca2+-permeable channels that regulate diverse cellular functions in neurons (Nilius, 2007; Venkatachalam and Montell, 2007; Sawamura et al., 2017). Based on functional characterization of TRP channels by a wide range of stimuli (Zheng, 2013), aberrant activity of TRP channels likely initiates and/or propagates ND processes, especially cell death, via increased intracellular Ca2+ in various brain regions (Moran, 2018; Hong et al., 2020; Huang et al., 2020). Here, we focus on the function of TRP channels associated with Ca2+ signaling in neurons and glial cells (Figure 1A) (Nilius, 2007; Bollimuntha et al., 2011; Zheng, 2013; Zhang and Liao, 2015; Jardin et al., 2017; Sawamura et al., 2017; Hasan and Zhang, 2018; Samanta et al., 2018; Cornillot et al., 2019; Enders et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020). Based on sequence homology, the TRP family currently comprises 28 mammalian channels and is subdivided into six subfamilies: TRP canonical (TRPC), TRP vanilloid (TRPV), TRP ankyrin (TRPA), TRP melastatin (TRPM), TRP polycystin (TRPP), and TRP mucolipin (TRPML) (Nilius, 2007; Selvaraj et al., 2010; Nishida et al., 2015; Sawamura et al., 2017). Most TRP channels are non-selective channels with consistent Ca2+ permeability (Samanta et al., 2018) and each TRP subtype responds to various temperatures, ligands, as well as specific agonists and activators (Figure 1B) (Luo et al., 2020). TRP channels are tetramers formed by monomers that share a common structure comprising six transmembrane domains and containing cation-selective pores (Hellmich and Gaudet, 2014). Numerous studies have reported that these TRP channels are related to neuronal cell death that is associated with abnormal Ca2+ homeostasis (Gees et al., 2010; Sawamura et al., 2017).

TRPC (Classic or Canonical)

TRPC was the first TRP group identified in mammals (Selvaraj et al., 2010). The TRPC subfamily contains members: TRPC1-7 (Wang et al., 2020). With the exception of TRPC2, all TRPC channels are widely expressed in the brain from the embryonic period to adulthood (Douglas et al., 2003). TRPC channels can form functional channels by heteromeric interactions, functioning as non-selective Ca2+ entry channels with distinct activation modes (Villereal, 2006). Thus, TRPC channels play an important role in regulating basic neuronal processes. TRPC1 is highly expressed and involved in the early development and proliferation of neurons (Yamamoto et al., 2005; Hentschke et al., 2006) as well as synaptic transmission (Broker-Lai et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2020). TRPC1 and TRPC4 have been reported to regulate neuronal cell death in response to seizures in the hippocampus and septum (Broker-Lai et al., 2017). The TRPC1/4/5 channel has been expressed in the somatosensory cortex, hippocampus, and motor cortex of adult rats (Riccio et al., 2002; Moran et al., 2004; Fowler et al., 2007). In particular, the dense expression of TRPC3 regulates hippocampal neuronal excitability and memory function (Neuner et al., 2015). The abnormal increase in sustained cytosolic Ca2+ by TRPC5 activation causes neuronal damage through the calpain-caspase-dependent pathway and the CaM kinase as seen in HD (Hong et al., 2015). Spinocerebellar ataxia type 14 (SCA14) is an autosomal dominant ND caused by a mutation in protein kinase Cγ (Wong et al., 2018). This mutation of SCA14 has been demonstrated to cause phosphorylation failure in TRPC3 channels, resulting in persistent Ca2+ entry that may contribute to neurodegeneration (Adachi et al., 2008). On the other hand, TRPC3 or TRPC6 promotes neurotrophin action on brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) by improving neuronal survival through Ca2+ influx (Huang et al., 2011). All TRPC channels are expressed in astrocytes and TRPC1 and TRPC3 play a critical role in astrocyte store-operated Ca2+ entry, which is induced by endoplasmic reticulum depletion (Verkhratsky et al., 2014). TRPC1 and TRPC6 are also expressed in rat microglia (Zhang and Liao, 2015). Thus, some TRPC channels exhibit different functions in normal physiological or pathological events, depending on Ca2+ signaling in the brain (Huang et al., 2011; Li et al., 2012; Neuner et al., 2015).

TRPM (Melastatin)

Of all TRP channels, the TRPM subfamily has the largest and most diverse expression levels and has been strongly implicated in NDs (Samanta et al., 2018). The TRPM channel consists of eight members (TRPM1-8) and shares common structural characteristics with other TRP channels (Huang et al., 2020). However, they have a variety of C-terminal sections with active enzyme domains and a unique N-terminal without ankyrin repeats involved in channel assembly and trafficking (Huang et al., 2020). A distinctive feature of TRPM channels is the regulation of Ca2+ and magnesium (Mg2+) homeostasis, and TRPM (2–7) are mainly expressed in the CNS. In addition, TRPM2 is activated by a wide range of factors including NAD+-related metabolites, adenosine diphosphate-ribose, oxidative stress, and depletion of glutathione (GSH) (Sita et al., 2018). Increased levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) due to GSH depletion causes TRPM2-dependent Ca2+ influx to induce neuronal cell death, suggesting that several neurological disorders, including AD, PD, and bipolar disorder (Akyuva and Naziroglu, 2020). In addition, an increase in intracellular Ca2+ and Aβ induced by TRPM2 activity induces neuronal cell death in the rat striatum (Belrose and Jackson, 2018). Mg2+ is the second most abundant cation and essential cofactor in various enzymatic reactions (Ryazanova et al., 2010). TRPM2 is expressed by both microglia and astrocytes, which regulate gliosis and immune cell function (Wang et al., 2016; Huang et al., 2017). TRPM7 is permeable to Mg2+ and maintains Mg2+ homeostasis (Ryazanova et al., 2010). In mouse cortical neurons, inhibition of TRPM7 expression protects against neuronal cell damage (Asrar and Aarts, 2013; Huang et al., 2020). TRPM7 is also found in astrocytes and microglia to control migration, proliferation, and invasion (Siddiqui et al., 2014; Zeng et al., 2015).

TRPV (Vanilloid)

TRPV channels form homo- or heterotetrameric complexes and are non-selective cation channels (Startek et al., 2019). The TRPV subfamily consists of six members (TRPV1-6) that are located mostly on the plasma membrane (Zhai et al., 2020). Recent studies on pathological TRPV1 expression in the brain have been performed (Mickle et al., 2015). TRPV1 activation induces caspase-3 dependent programmed cell death through Ca2+-mediated signaling, resulting in cell death of cortical neurons (Ho et al., 2012; Song et al., 2013) and also triggers cell death through L-type Ca2+ channels and Ca2+ influx in rat cortical neurons (Shirakawa et al., 2008). The activation of cannabinoid 1 (CB1) receptors stimulates TRPV1 activity, leading to increased intracellular Ca2+ and cell death of mesencephalic dopaminergic neurons (Kim et al., 2005, 2008). TRPV1 activation induces apoptotic cell death in rat cortical neurons, leading to chronic epilepsy distinguished by abnormal brain activity (Fu et al., 2009). TRPV1 activation in microglia plays a positive role in promoting microglial phagocytosis in damaged cells while disrupting mitochondria and increasing ROS production (Kim et al., 2006; Hassan et al., 2014). TRPV1 has been shown to affect the migration of astrocytes (Ho et al., 2014). Abnormal function of TRPV4 leads to neuronal dysfunction and axonal degeneration due to increased Ca2+ via Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) (Woolums et al., 2020). TRPV4 plays a role in regulating the osmotic pressure in the brain and is highly expressed throughout glial cells associated with ND (Liedtke and Friedman, 2003; Rakers et al., 2017). Thus, these channels play an important role in Ca2+ homeostasis and are therapeutic targets for various disorders.

TRPA (Ankyrin)

TRPA1 was first identified as an ankyrin-like transmembrane protein and the solitary member of the mammalian TRPA subfamily (Yang and Li, 2016). TRPA1 is a non-selective cation channel formed by homo- or heterotetramer subunits with a cytosolic N-terminal domain (16 ankyrin repeat sequence) and C-terminal Ca2+-binding domains (Nilius et al., 2011; Fernandes et al., 2012). The TRPA1 channel responds to a variety of ligands, such as temperature, osmotic changes, and endogenous compounds (Nishida et al., 2015). To date, the reported role of TRPA1 in neurons is the mediation of pain, cold, inflammation, and itch sensation (Fernandes et al., 2012). Recent reports indicate that TRPA1 hyperactivation causes Aβ oligomer-mediated rapid Ca2+ signaling (Bosson et al., 2017; Hong et al., 2020). Additionally, ablation of TRPA1 in APP/PS1 transgenic mice attenuated the progression of AD, improved learning and memory conditions, and reduced Aβ plaques and cytokines (Lee et al., 2016). Similarly, TRPA1 channels promote Ca2+ hyperactivity of astrocytes and then contribute to synaptic dysfunction due to the oligomeric forms of Aβ peptide (Lee et al., 2016; Bosson et al., 2017; Logashina et al., 2019; Alavi et al., 2020). In addition, TRPA1 mediates Ca2+ signaling in astrocytes, resulting in dysregulation of synaptic activity in AD (Bosson et al., 2017).

Other Channels

TRPML and TRPP have limited similarity to other TRP family members (Samanta et al., 2018; Huang et al., 2020). TRPML channels (TRPML1-3) are Ca2+ permeable cation channels that each contain six transmembrane segments with helices (S1–S6) and a pore site comprised of S5, S6, and two pore helices (PH1 and PH2) (Schmiege et al., 2018; Tedeschi et al., 2019). TRPML channels are mostly located in intracellular compartments instead of the plasma membrane (Clement et al., 2020). TRPP channels share high protein sequence similarity with TRPML channels and are located in the primary cilia consisting of TRPP1 (also known as PKD1) and TRPP2 (PKD2) (Samanta et al., 2018). To date, evidence indicates that various TRP channels are expressed in the CNS and play important roles in the development of several NDs (Sawamura et al., 2017; Samanta et al., 2018). In particular, TRP channels and Ca2+ homeostasis (Bezprozvanny, 2010) are likely to underpin Ca2+-dependent neuronal death in NDs (Sawamura et al., 2017; Hong et al., 2020).

Pathophysiological Role of Plasma Membrane Calcium ATPases

Of the various proteins involved in Ca2+ signaling, PMCA is the most sensitive Ca2+ detector that regulates Ca2+ homeostasis (Boczek et al., 2019). PMCA exists in four known isoforms (Boczek et al., 2019). In both mice and humans, PMCAs 1–4 exhibit anatomically distinct expression patterns, such that isoforms 1 and 4 are ubiquitously expressed in all tissue types, whereas PMCA2 and PMCA3 are tissue-specific and exclusive in neurons of the brain (Kip et al., 2006). In addition, PMCA1, 2, and 4 were detected in rat cortical astrocytes (Fresu et al., 1999) (Table 2). The general structure of PMCA consists of 10 transmembrane domains (TM) with the N- and C-terminal ends on the cytosolic side (Stafford et al., 2017). The physiological functions of PMCA include the regulation and maintenance of optimal Ca2+ homeostasis (Bagur and Hajnoczky, 2017). PMCA is an ATP-driven Ca2+ pump that maintains low resting intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) to prevent cytotoxic Ca2+overload-mediated cell death through activation of ion channels such as TRP (Zundorf and Reiser, 2011). In addition, PMCA is involved in Ca2+-induced intracellular acidification by countertransport of H+ ions (Vale-Gonzalez et al., 2006; Majdi et al., 2016). Thus, PMCA plays a vital role in controlling cell survival and cell death (Stafford et al., 2017). PMCA expression changes significantly during brain development (Boczek et al., 2019). One of the characteristics of brain aging is a Ca2+ homeostasis disorder, which can result in detrimental consequences on neuronal function (Boczek et al., 2019). Overall, PMCAs have been attributed a housekeeping role in maintaining intracellular Ca2+ levels through precise regulation of Ca2+ homeostasis (Strehler et al., 2007). However, the altered composition of PMCA is associated with a less efficient Ca2+ extrusion system, increasing the risk of neurodegenerative processes (Strehler and Thayer, 2018). ATP2B2 is a deafness-associated gene that encodes PMCA2 (Smits et al., 2019). A recent study reported a link between PMCA2 and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) (Yang et al., 2013). ASD is a group of neurodevelopmental disorders that results in deficits in social interaction (Chaste and Leboyer, 2012; Fatemi et al., 2012). Intracellular Ca2+ levels are crucial for regulating neuronal survival, differentiation, and migration (Bezprozvanny, 2010). Perturbations in these processes underlie the pathogenesis of autism spectrum disorders (Gilbert and Man, 2017). ATP2B3 mutations are associated with X-linked cerebellar ataxia and Ca2+ extrusion disorders in patients with cerebellar ataxia and developmental delay (Zanni et al., 2012; Mazzitelli and Adamo, 2014; Cali et al., 2015). Several neurotoxic agents, such as oxidation and age, downregulate PMCA function and increase susceptibility to NDs (Zaidi, 2010). In particular, the internalization of PMCA2 initiated by protease function in rat hippocampal pyramidal cells after glutamate exposure or kainate-induced seizures, in which loss of PMCA function occurs, may contribute to Ca2+ dysregulation and lead to neuronal cell death (Pottorf et al., 2006; Stafford et al., 2017). A decrease in PMCA activity and increased Ca2+ may cause cell death depending on the degree of cytosolic accumulation of tau and Aβ in AD (Boczek et al., 2019). In addition, PMCA expression is decreased in the cortex of postmortem brains of patients with AD (Berrocal et al., 2019; Boczek et al., 2019).

Table 2.

A summary of the transient receptor potential (TRP) subtypes found in distribution of central nervous system (CNS) cell types.

| PMCA subfamily | Expression in brain | Expression in glia | Disorders | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PMCA1 | - Ubiquitous in brain (human and rat). - Cerebellum, cerebral cortex, brain stem (Human) |

Rat cortical astrocytes | AD, PD | Stauffer et al., 1995; Fresu et al., 1999; Brini et al., 2013 |

| PMCA2 | - Cerebellar purkinje neurons (human/mouse) - cerebellum, cerebral cortex, brain stem (Human) |

Rat cortical astrocytes | AD, PD, cerebellar ataxias, sensory neuron diseases | Stauffer et al., 1995; Fresu et al., 1999; Kurnellas et al., 2007; Empson et al., 2010; Hajieva et al., 2018; Strehler and Thayer, 2018 |

| PMCA3 | - Cerebellum, cerebral cortex (Human) - Cerebellum and hippocampus (Rat) |

Limited | Cerebellar ataxias, sensory neuron diseases | Stauffer et al., 1995; Zanni et al., 2012; Strehler and Thayer, 2018 |

| PMCA4 | - Ubiquitous in brain (human/rat) - Cerebellum, cerebral cortex, brain stem (Human) |

Rat cortical astrocytes | AD, PD | Stauffer et al., 1995; Fresu et al., 1999; Brini et al., 2013; Zaidi et al., 2018 |

PMCA, plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPase; AD, Alzheimer's disease; PD, Parkinson's disease.

pH Regulation by PMCA in Neurodegenerative Diseases

As mentioned above, PMCAs have a Ca2+ extrusion function on the membrane and another important function, namely H+ uptake (Stafford et al., 2017). Since PMCA is responsible for control of Ca2+ extrusion and H+ uptake rates, it provides an important link between Ca2+ signaling and intracellular pH (pHi) in neurons (Hwang et al., 2011). Mechanisms that maintain strict pH homeostasis in the brain control neuronal excitability, synaptic transmission, neurotransmitter uptake, nociception, and inflammation (Chesler, 2003; Dhaka et al., 2009; Casey et al., 2010; Hwang et al., 2011). Changes in pH caused via pH-sensitive or pH-regulated ion channels are detrimental to brain function and can cause multiple degenerative diseases (Ruffin et al., 2014). Neuronal excitability is particularly sensitive to changes in intracellular and extracellular pH mediated by various ion channels (Parker and Boron, 2013). The activation of TRPV1 has been reported to induce a rise in Ca2+ and cause intracellular acidification via the activation of PMCA in the rat trigeminal ganglion (Hwang et al., 2011). Under normal conditions, acidification conditions are promptly returned to and maintained at normal pH levels through a physiological pHi recovery mechanism involving the regulation of Na+/H+ exchangers (NHE) and Na+- cotransporter (NBCs) in the brain (Chesler, 2003; Sinning and Hubner, 2013; Ruffin et al., 2014; Bose et al., 2015). NHE1 is abundantly expressed in all neuronal cells and astrocytes, regulating cell volume homeostasis and pHi (Song et al., 2020). NBC1 is also widely expressed in astrocytes throughout the brain (Annunziato et al., 2013) (Figure 1A). However, functional inhibition of pHi recovery mechanism in pathological conditions leads to excessive intracellular acidification (Majdi et al., 2016). Therefore, although the exact underlying mechanism that causes intracellular acidification in brain neurons is unknown. However, it appears that persistent intracellular acidification condition promotes irreversible neuronal damage and induces amyloid aggregation in the brains of patients with AD (Xiong et al., 2008; Ruffin et al., 2014).

Conclusion

Intracellular Ca2+ and pH regulation play vital roles in both physiological and pathological conditions. Abnormal changes in Ca2+ or pH typically cause cell death. TRP channels are involved in Ca2+ influx, which affects neuronal and glial functions under normal physiological conditions. However, altered expression of TRP channels can lead to excess Ca2+ influx, and intracellular Ca2+ overload is maintained due to ATP2B2, oxidation, and aging-related downregulation of PMCA, leading to Ca2+-dependent cell death. Alternatively, overexpression of PMCA due to cytoplasmic Ca2+ overload causes continuous acidification from inhibition of the pHi recovery mechanisms by oxidative stress or programmed cell death, resulting in acidification-dependent cell death (Figure 2) (Harguindey et al., 2017, 2019). To date, TRP channels have been investigated for their role in NDs. However, targeting TRP channels and PMCA, including Ca2+ and pH regulation, as a treatment for NDs requires a deeper understanding of their function in both health and disease. This review describes potential therapeutic targets for NDs by discussing TRP channels and PMCA responsible for the disruption of intracellular Ca2+ and pH homeostasis that underpin ND development.

Author Contributions

C-KP and YK conceived and supervised the project. S-MH, JL, C-KP, and YK wrote the paper. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by grants from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2017M3C7A1025602 and NRF-2019R1C1C1010822).

References

- Aarts M. M., Tymianski M. (2005). TRPMs and neuronal cell death. Pflugers Arch. 451, 243–249. 10.1007/s00424-005-1439-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adachi N., Kobayashi T., Takahashi H., Kawasaki T., Shirai Y., Ueyama T., et al. (2008). Enzymological analysis of mutant protein kinase Cgamma causing spinocerebellar ataxia type 14 and dysfunction in Ca2+ homeostasis. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 19854–19863. 10.1074/jbc.M801492200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akyuva Y., Naziroglu M. (2020). Resveratrol attenuates hypoxia-induced neuronal cell death, inflammation and mitochondrial oxidative stress by modulation of TRPM2 channel. Sci. Rep. 10:6449. 10.1038/s41598-020-63577-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alavi M. S., Shamsizadeh A., Karimi G., Roohbakhsh A. (2020). Transient receptor potential ankyrin 1 (TRPA1)-mediated toxicity: friend or foe? Toxicol. Mech. Methods 30, 1–18. 10.1080/15376516.2019.1652872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annunziato L., Boscia F., Pignataro G. (2013). Ionic transporter activity in astrocytes, microglia, and oligodendrocytes during brain ischemia. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 33, 969–982. 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asrar S., Aarts M. (2013). TRPM7, the cytoskeleton and neuronal death. Channels (Austin) 7, 6–16. 10.4161/chan.22824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auer-Grumbach M., Olschewski A., Papic L., Kremer H., Mcentagart M. E., Uhrig S., et al. (2010). Alterations in the ankyrin domain of TRPV4 cause congenital distal SMA, scapuloperoneal SMA and HMSN2C. Nat. Genet. 42, 160–164. 10.1038/ng.508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagur R., Hajnoczky G. (2017). Intracellular Ca(2+) Sensing: its role in calcium homeostasis and signaling. Mol. Cell 66, 780–788. 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.05.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balleza-Tapia H., Crux S., Andrade-Talavera Y., Dolz-Gaiton P., Papadia D., Chen G., et al. (2018). TrpV1 receptor activation rescues neuronal function and network gamma oscillations from Abeta-induced impairment in mouse hippocampus in vitro. Elife 7:37703. 10.7554/eLife.37703.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belrose J. C., Jackson M. F. (2018). TRPM2: a candidate therapeutic target for treating neurological diseases. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 39, 722–732. 10.1038/aps.2018.31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge M. J., Lipp P., Bootman M. D. (2000). The versatility and universality of calcium signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 1, 11–21. 10.1038/35036035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrocal M., Caballero-Bermejo M., Gutierrez-Merino C., Mata A. M. (2019). Methylene blue blocks and reverses the inhibitory effect of tau on PMCA function. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20:3521. 10.3390/ijms20143521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezprozvanny I. B. (2010). Calcium signaling and neurodegeneration. Acta Naturae 2, 72–82. 10.32607/20758251-2010-2-1-72-80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boczek T., Radzik T., Ferenc B., Zylinska L. (2019). The puzzling role of neuron-specific PMCA isoforms in the aging process. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20:6338. 10.3390/ijms20246338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolcskei K., Kriszta G., Saghy E., Payrits M., Sipos E., Vranesics A., et al. (2018). Behavioural alterations and morphological changes are attenuated by the lack of TRPA1 receptors in the cuprizone-induced demyelination model in mice. J. Neuroimmunol. 320, 1–10. 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2018.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollimuntha S., Ebadi M., Singh B. B. (2006). TRPC1 protects human SH-SY5Y cells against salsolinol-induced cytotoxicity by inhibiting apoptosis. Brain Res. 1099, 141–149. 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.04.104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollimuntha S., Selvaraj S., Singh B. B. (2011). Emerging roles of canonical TRP channels in neuronal function. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 704, 573–593. 10.1007/978-94-007-0265-3_31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollimuntha S., Singh B. B., Shavali S., Sharma S. K., Ebadi M. (2005). TRPC1-mediated inhibition of 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium ion neurotoxicity in human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 2132–2140. 10.1074/jbc.M407384200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bose T., Cieslar-Pobuda A., Wiechec E. (2015). Role of ion channels in regulating Ca(2)(+) homeostasis during the interplay between immune and cancer cells. Cell Death Dis. 6:e1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosson A., Paumier A., Boisseau S., Jacquier-Sarlin M., Buisson A., Albrieux M. (2017). TRPA1 channels promote astrocytic Ca(2+) hyperactivity and synaptic dysfunction mediated by oligomeric forms of amyloid-beta peptide. Mol. Neurodegener. 12:53. 10.1186/s13024-017-0194-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brini M., Cali T., Ottolini D., Carafoli E. (2013). The plasma membrane calcium pump in health and disease. FEBS J. 280, 5385–5397. 10.1111/febs.12193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broker-Lai J., Kollewe A., Schindeldecker B., Pohle J., Nguyen Chi V., Mathar I., et al. (2017). Heteromeric channels formed by TRPC1, TRPC4 and TRPC5 define hippocampal synaptic transmission and working memory. EMBO J. 36, 2770–2789. 10.15252/embj.201696369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butenko O., Dzamba D., Benesova J., Honsa P., Benfenati V., Rusnakova V., et al. (2012). The increased activity of TRPV4 channel in the astrocytes of the adult rat hippocampus after cerebral hypoxia/ischemia. PLoS ONE 7:e39959. 10.1371/journal.pone.0039959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cali T., Lopreiato R., Shimony J., Vineyard M., Frizzarin M., Zanni G., et al. (2015). A novel mutation in isoform 3 of the plasma membrane Ca2+ pump impairs cellular Ca2+ homeostasis in a patient with cerebellar ataxia and laminin subunit 1alpha mutations. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 16132–16141. 10.1074/jbc.M115.656496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey J. R., Grinstein S., Orlowski J. (2010). Sensors and regulators of intracellular pH. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 50–61. 10.1038/nrm2820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaste P., Leboyer M. (2012). Autism risk factors: genes, environment, and gene-environment interactions. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 14, 281–292. 10.31887/DCNS.2012.14.3/pchaste [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D. H., Sul Y., Weiss M., Hillel A., Lipe H., Wolff J., et al. (2010). CMT2C with vocal cord paresis associated with short stature and mutations in the TRPV4 gene. Neurology 75, 1968–1975. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181ffe4bb [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Numata T., Li M., Mori Y., Orser B. A., Jackson M. F., et al. (2010). The modulation of TRPM7 currents by nafamostat mesilate depends directly upon extracellular concentrations of divalent cations. Mol. Brain 3:38. 10.1186/1756-6606-3-38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesler M. (2003). Regulation and modulation of pH in the brain. Physiol. Rev. 83, 1183–1221. 10.1152/physrev.00010.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi H., Chang H. Y., Sang T. K. (2018). Neuronal cell death mechanisms in major neurodegenerative diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19:3082. 10.3390/ijms19103082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement D., Goodridge J. P., Grimm C., Patel S., Malmberg K. J. (2020). TRP channels as interior designers: remodeling the endolysosomal compartment in natural killer cells. Front. Immunol. 11:753. 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coombes E., Jiang J., Chu X. P., Inoue K., Seeds J., Branigan D., et al. (2011). Pathophysiologically relevant levels of hydrogen peroxide induce glutamate-independent neurodegeneration that involves activation of transient receptor potential melastatin 7 channels. Antioxid. Redox Signal 14, 1815–1827. 10.1089/ars.2010.3549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornillot M., Giacco V., Hamilton N. B. (2019). The role of TRP channels in white matter function and ischaemia. Neurosci. Lett. 690, 202–209. 10.1016/j.neulet.2018.10.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross J. L., Meloni B. P., Bakker A. J., Lee S., Knuckey N. W. (2010). Modes of neuronal calcium entry and homeostasis following cerebral ischemia. Stroke Res. Treat. 2010:316862. 10.4061/2010/316862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuomo O., Vinciguerra A., Cerullo P., Anzilotti S., Brancaccio P., Bilo L., et al. (2015). Ionic homeostasis in brain conditioning. Front. Neurosci. 9:277. 10.3389/fnins.2015.00277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhaka A., Uzzell V., Dubin A. E., Mathur J., Petrus M., Bandell M., et al. (2009). TRPV1 is activated by both acidic and basic pH. J. Neurosci. 29, 153–158. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4901-08.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas R. M., Xue J., Chen J. Y., Haddad C. G., Alper S. L., Haddad G. G. (2003). Chronic intermittent hypoxia decreases the expression of Na/H exchangers and HCO3-dependent transporters in mouse CNS. J. Appl. Physiol. 95, 292–299. 10.1152/japplphysiol.01089.2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Empson R. M., Akemann W., Knopfel T. (2010). The role of the calcium transporter protein plasma membrane calcium ATPase PMCA2 in cerebellar Purkinje neuron function. Funct. Neurol. 25, 153–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders M., Heider T., Ludwig A., Kuerten S. (2020). Strategies for neuroprotection in multiple sclerosis and the role of calcium. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21:1663. 10.3390/ijms21051663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatemi S. H., Aldinger K. A., Ashwood P., Bauman M. L., Blaha C. D., Blatt G. J., et al. (2012). Consensus paper: pathological role of the cerebellum in autism. Cerebellum 11, 777–807. 10.1007/s12311-012-0355-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes E. S., Fernandes M. A., Keeble J. E. (2012). The functions of TRPA1 and TRPV1: moving away from sensory nerves. Br. J. Pharmacol. 166, 510–521. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.01851.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonfria E., Marshall I. C., Boyfield I., Skaper S. D., Hughes J. P., Owen D. E., et al. (2005). Amyloid beta-peptide(1-42) and hydrogen peroxide-induced toxicity are mediated by TRPM2 in rat primary striatal cultures. J. Neurochem. 95, 715–723. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03396.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler M. A., Sidiropoulou K., Ozkan E. D., Phillips C. W., Cooper D. C. (2007). Corticolimbic expression of TRPC4 and TRPC5 channels in the rodent brain. PLoS ONE 2:e573. 10.1371/journal.pone.0000573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fresu L., Dehpour A., Genazzani A. A., Carafoli E., Guerini D. (1999). Plasma membrane calcium ATPase isoforms in astrocytes. Glia 28, 150–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu M., Xie Z., Zuo H. (2009). TRPV1: a potential target for antiepileptogenesis. Med. Hypotheses 73, 100–102. 10.1016/j.mehy.2009.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gees M., Colsoul B., Nilius B. (2010). The role of transient receptor potential cation channels in Ca2+ signaling. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2:a003962. 10.1101/cshperspect.a003962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson H. E., Edwards J. G., Page R. S., Van Hook M. J., Kauer J. A. (2008). TRPV1 channels mediate long-term depression at synapses on hippocampal interneurons. Neuron 57, 746–759. 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.12.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert J., Man H. Y. (2017). Fundamental elements in autism: from neurogenesis and neurite growth to synaptic plasticity. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 11:359. 10.3389/fncel.2017.00359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleichmann M., Mattson M. P. (2011). Neuronal calcium homeostasis and dysregulation. Antioxid. Redox Signal 14, 1261–1273. 10.1089/ars.2010.3386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajieva P., Baeken M. W., Moosmann B. (2018). The role of Plasma Membrane Calcium ATPases (PMCAs) in neurodegenerative disorders. Neurosci. Lett. 663, 29–38. 10.1016/j.neulet.2017.09.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamakawa H., Murashita J., Yamada N., Inubushi T., Kato N., Kato T. (2004). Reduced intracellular pH in the basal ganglia and whole brain measured by 31P-MRS in bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 58, 82–88. 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2004.01197.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harguindey S., Polo Orozco J., Alfarouk K. O., Devesa J. (2019). Hydrogen ion dynamics of cancer and a new molecular, biochemical and metabolic approach to the etiopathogenesis and treatment of brain malignancies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20:4278. 10.3390/ijms20174278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harguindey S., Reshkin S. J., Orive G., Arranz J. L., Anitua E. (2007). Growth and trophic factors, pH and the Na+/H+ exchanger in Alzheimer's disease, other neurodegenerative diseases and cancer: new therapeutic possibilities and potential dangers. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 4, 53–65. 10.2174/156720507779939841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harguindey S., Stanciu D., Devesa J., Alfarouk K., Cardone R. A., Polo Orozco J. D., et al. (2017). Cellular acidification as a new approach to cancer treatment and to the understanding and therapeutics of neurodegenerative diseases. Semin. Cancer Biol. 43, 157–179. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2017.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan R., Zhang X. (2018). Ca(2+) regulation of TRP ion channels. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19:1256. 10.3390/ijms19041256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan S., Eldeeb K., Millns P. J., Bennett A. J., Alexander S. P., Kendall D. A. (2014). Cannabidiol enhances microglial phagocytosis via transient receptor potential (TRP) channel activation. Br. J. Pharmacol. 171, 2426–2439. 10.1111/bph.12615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellmich U. A., Gaudet R. (2014). Structural biology of TRP channels. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 223, 963–990. 10.1007/978-3-319-05161-1_10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hentschke M., Wiemann M., Hentschke S., Kurth I., Hermans-Borgmeyer I., Seidenbecher T., et al. (2006). Mice with a targeted disruption of the Cl-/HCO3- exchanger AE3 display a reduced seizure threshold. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 182–191. 10.1128/MCB.26.1.182-191.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermosura M. C., Cui A. M., Go R. C., Davenport B., Shetler C. M., Heizer J. W., et al. (2008). Altered functional properties of a TRPM2 variant in Guamanian ALS and PD. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105, 18029–18034. 10.1073/pnas.0808218105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermosura M. C., Nayakanti H., Dorovkov M. V., Calderon F. R., Ryazanov A. G., Haymer D. S., et al. (2005). A TRPM7 variant shows altered sensitivity to magnesium that may contribute to the pathogenesis of two Guamanian neurodegenerative disorders. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102, 11510–11515. 10.1073/pnas.0505149102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho K. W., Lambert W. S., Calkins D. J. (2014). Activation of the TRPV1 cation channel contributes to stress-induced astrocyte migration. Glia 62, 1435–1451. 10.1002/glia.22691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho K. W., Ward N. J., Calkins D. J. (2012). TRPV1: a stress response protein in the central nervous system. Am. J. Neurodegener. Dis. 1, 1–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong C., Jeong B., Park H. J., Chung J. Y., Lee J. E., Kim J., et al. (2020). TRP channels as emerging therapeutic targets for neurodegenerative diseases. Front. Physiol. 11:238. 10.3389/fphys.2020.00238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong C., Seo H., Kwak M., Jeon J., Jang J., Jeong E. M., et al. (2015). Increased TRPC5 glutathionylation contributes to striatal neuron loss in Huntington's disease. Brain 138, 3030–3047. 10.1093/brain/awv188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J., Du W., Yao H., Wang Y. (2011). TRPC channels in neuronal survival, in TRP Channels, ed Zhu M. X. (Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press/Taylor & Francis; ), 1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S., Turlova E., Li F., Bao M. H., Szeto V., Wong R., et al. (2017). Transient receptor potential melastatin 2 channels (TRPM2) mediate neonatal hypoxic-ischemic brain injury in mice. Exp. Neurol. 296, 32–40. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2017.06.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Fliegert R., Guse A. H., Lu W., Du J. (2020). A structural overview of the ion channels of the TRPM family. Cell Calcium 85:102111. 10.1016/j.ceca.2019.102111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang S. M., Koo N. Y., Jin M., Davies A. J., Chun G. S., Choi S. Y., et al. (2011). Intracellular acidification is associated with changes in free cytosolic calcium and inhibition of action potentials in rat trigeminal ganglion. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 1719–1729. 10.1074/jbc.M109.090951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jardin I., Lopez J. J., Diez R., Sanchez-Collado J., Cantonero C., Albarran L., et al. (2017). TRPs in pain sensation. Front. Physiol. 8:392. 10.3389/fphys.2017.00392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L., Bechtel M. D., Galeva N. A., Williams T. D., Michaelis E. K., Michaelis M. L. (2012). Decreases in plasma membrane Ca(2)(+)-ATPase in brain synaptic membrane rafts from aged rats. J. Neurochem. 123, 689–699. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2012.07918.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczmarek J. S., Riccio A., Clapham D. E. (2012). Calpain cleaves and activates the TRPC5 channel to participate in semaphorin 3A-induced neuronal growth cone collapse. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109, 7888–7892. 10.1073/pnas.1205869109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko S., Kawakami S., Hara Y., Wakamori M., Itoh E., Minami T., et al. (2006). A critical role of TRPM2 in neuronal cell death by hydrogen peroxide. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 101, 66–76. 10.1254/jphs.FP0060128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko Y., Szallasi A. (2014). Transient receptor potential (TRP) channels: a clinical perspective. Br. J. Pharmacol. 171, 2474–2507. 10.1111/bph.12414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato T., Murashita J., Kamiya A., Shioiri T., Kato N., Inubushi T. (1998). Decreased brain intracellular pH measured by 31P-MRS in bipolar disorder: a confirmation in drug-free patients and correlation with white matter hyperintensity. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 248, 301–306. 10.1007/s004060050054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamoto E. M., Vivar C., Camandola S. (2012). Physiology and pathology of calcium signaling in the brain. Front. Pharmacol. 3:61. 10.3389/fphar.2012.00061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. R., Bok E., Chung Y. C., Chung E. S., Jin B. K. (2008). Interactions between CB(1) receptors and TRPV1 channels mediated by 12-HPETE are cytotoxic to mesencephalic dopaminergic neurons. Br. J. Pharmacol. 155, 253–264. 10.1038/bjp.2008.246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. R., Kim S. U., Oh U., Jin B. K. (2006). Transient receptor potential vanilloid subtype 1 mediates microglial cell death in vivo and in vitro via Ca2+-mediated mitochondrial damage and cytochrome c release. J. Immunol. 177, 4322–4329. 10.4049/jimmunol.177.7.4322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. R., Lee D. Y., Chung E. S., Oh U. T., Kim S. U., Jin B. K. (2005). Transient receptor potential vanilloid subtype 1 mediates cell death of mesencephalic dopaminergic neurons in vivo and in vitro. J. Neurosci. 25, 662–671. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4166-04.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kip S. N., Gray N. W., Burette A., Canbay A., Weinberg R. J., Strehler E. E. (2006). Changes in the expression of plasma membrane calcium extrusion systems during the maturation of hippocampal neurons. Hippocampus 16, 20–34. 10.1002/hipo.20129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein C. J., Shi Y., Fecto F., Donaghy M., Nicholson G., Mcentagart M. E., et al. (2011). TRPV4 mutations and cytotoxic hypercalcemia in axonal Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathies. Neurology 76, 887–894. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31820f2de3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A., Bodhinathan K., Foster T. C. (2009). Susceptibility to calcium dysregulation during brain aging. Front. Aging Neurosci. 1:2. 10.3389/neuro.24.002.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P., Kumar D., Jha S. K., Jha N. K., Ambasta R. K. (2016). Ion channels in neurological disorders. Adv. Protein Chem. Struct. Biol. 103, 97–136. 10.1016/bs.apcsb.2015.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurnellas M. P., Lee A. K., Szczepanowski K., Elkabes S. (2007). Role of plasma membrane calcium ATPase isoform 2 in neuronal function in the cerebellum and spinal cord. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1099, 287–291. 10.1196/annals.1387.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landoure G., Zdebik A. A., Martinez T. L., Burnett B. G., Stanescu H. C., Inada H., et al. (2010). Mutations in TRPV4 cause Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 2C. Nat. Genet. 42, 170–174. 10.1038/ng.512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lastres-Becker I., De Miguel R., De Petrocellis L., Makriyannis A., Di Marzo V., Fernandez-Ruiz J. (2003). Compounds acting at the endocannabinoid and/or endovanilloid systems reduce hyperkinesia in a rat model of Huntington's disease. J. Neurochem. 84, 1097–1109. 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01595.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K. I., Lee H. T., Lin H. C., Tsay H. J., Tsai F. C., Shyue S. K., et al. (2016). Role of transient receptor potential ankyrin 1 channels in Alzheimer's disease. J. Neuroinflammation 13:92. 10.1186/s12974-016-0557-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee T. H., Lee J. G., Yon J. M., Oh K. W., Baek I. J., Nahm S. S., et al. (2011). Capsaicin prevents kainic acid-induced epileptogenesis in mice. Neurochem. Int. 58, 634–640. 10.1016/j.neuint.2011.01.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lessard C. B., Lussier M. P., Cayouette S., Bourque G., Boulay G. (2005). The overexpression of presenilin2 and Alzheimer's-disease-linked presenilin2 variants influences TRPC6-enhanced Ca2+ entry into HEK293 cells. Cell. Signal 17, 437–445. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2004.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. B., Mao R. R., Zhang J. C., Yang Y., Cao J., Xu L. (2008). Antistress effect of TRPV1 channel on synaptic plasticity and spatial memory. Biol. Psychiatry 64, 286–292. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.02.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Calfa G., Larimore J., Pozzo-Miller L. (2012). Activity-dependent BDNF release and TRPC signaling is impaired in hippocampal neurons of Mecp2 mutant mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109, 17087–17092. 10.1073/pnas.1205271109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liedtke W., Friedman J. M. (2003). Abnormal osmotic regulation in trpv4-/- mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100, 13698–13703. 10.1073/pnas.1735416100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N., Wu J., Chen Y., Zhao J. (2020). Channels that cooperate with TRPV4 in the brain. J. Mol. Neurosci. 70, 1812–1820. 10.1007/s12031-020-01574-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N., Zhuang Y., Zhou Z., Zhao J., Chen Q., Zheng J. (2017). NF-kappaB dependent up-regulation of TRPC6 by Abeta in BV-2 microglia cells increases COX-2 expression and contributes to hippocampus neuron damage. Neurosci. Lett. 651, 1–8. 10.1016/j.neulet.2017.04.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logashina Y. A., Korolkova Y. V., Kozlov S. A., Andreev Y. A. (2019). TRPA1 channel as a regulator of neurogenic inflammation and pain: structure, function, role in pathophysiology, and therapeutic potential of ligands. Biochemistry Mosc. 84, 101–118. 10.1134/S0006297919020020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu R., He Q., Wang J. (2017). TRPC channels and Alzheimer's disease. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 976, 73–83. 10.1007/978-94-024-1088-4_7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo L., Song S., Ezenwukwa C. C., Jalali S., Sun B., Sun D. (2020). Ion channels and transporters in microglial function in physiology and brain diseases. Neurochem. Int. 142:104925. 10.1016/j.neuint.2020.104925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majdi A., Mahmoudi J., Sadigh-Eteghad S., Golzari S. E., Sabermarouf B., Reyhani-Rad S. (2016). Permissive role of cytosolic pH acidification in neurodegeneration: a closer look at its causes and consequences. J. Neurosci. Res. 94, 879–887. 10.1002/jnr.23757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maklad A., Sharma A., Azimi I. (2019). Calcium signaling in brain cancers: roles and therapeutic targeting. Cancers 11:145. 10.3390/cancers11020145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal P. K., Akolkar H., Tripathi M. (2012). Mapping of hippocampal pH and neurochemicals from in vivo multi-voxel 31P study in healthy normal young male/female, mild cognitive impairment, and Alzheimer's disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 31, S75–86. 10.3233/JAD-2012-120166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marambaud P., Dreses-Werringloer U., Vingtdeux V. (2009). Calcium signaling in neurodegeneration. Mol. Neurodegener. 4:20. 10.1186/1750-1326-4-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzitelli L. R., Adamo H. P. (2014). Hyperactivation of the human plasma membrane Ca2+ pump PMCA h4xb by mutation of Glu99 to Lys. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 10761–10768. 10.1074/jbc.M113.535583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mickle A. D., Shepherd A. J., Mohapatra D. P. (2015). Sensory TRP channels: the key transducers of nociception and pain. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 131, 73–118. 10.1016/bs.pmbts.2015.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minke B. (2006). TRP channels and Ca2+ signaling. Cell Calcium 40, 261–275. 10.1016/j.ceca.2006.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizoguchi Y., Kato T. A., Seki Y., Ohgidani M., Sagata N., Horikawa H., et al. (2014). Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) induces sustained intracellular Ca2+ elevation through the up-regulation of surface transient receptor potential 3 (TRPC3) channels in rodent microglia. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 18549–18555. 10.1074/jbc.M114.555334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran M. M. (2018). TRP channels as potential drug targets. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 58, 309–330. 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010617-052832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran M. M., Xu H., Clapham D. E. (2004). TRP ion channels in the nervous system. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 14, 362–369. 10.1016/j.conb.2004.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morelli M. B., Amantini C., Liberati S., Santoni M., Nabissi M. (2013). TRP channels: new potential therapeutic approaches in CNS neuropathies. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 12, 274–293. 10.2174/18715273113129990056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuner S. M., Wilmott L. A., Hope K. A., Hoffmann B., Chong J. A., Abramowitz J., et al. (2015). TRPC3 channels critically regulate hippocampal excitability and contextual fear memory. Behav. Brain Res. 281, 69–77. 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.12.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikoletopoulou V., Tavernarakis N. (2012). Calcium homeostasis in aging neurons. Front. Genet. 3:200. 10.3389/fgene.2012.00200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilius B. (2007). TRP channels in disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1772, 805–812. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2007.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilius B., Owsianik G. (2011). The transient receptor potential family of ion channels. Genome Biol. 12:218. 10.1186/gb-2011-12-3-218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilius B., Prenen J., Owsianik G. (2011). Irritating channels: the case of TRPA1. J. Physiol. 589, 1543–1549. 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.200717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida M., Kuwahara K., Kozai D., Sakaguchi R., Mori Y. (2015). TRP channels: their function and potentiality as drug targets, in Innovative Medicine: Basic Research and Development, eds Nakao K., Minato N., Uemoto S. (Tokyo: Springer; ), 195–218. 10.1007/978-4-431-55651-0_17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakes M., Law W. J., Komuniecki R. (2019). Cannabinoids stimulate the trp channel-dependent release of both serotonin and dopamine to modulate behavior in C. elegans. J. Neurosci. 39, 4142–4152. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2371-18.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostapchenko V. G., Chen M., Guzman M. S., Xie Y. F., Lavine N., Fan J., et al. (2015). The Transient Receptor Potential Melastatin 2 (TRPM2) channel contributes to beta-amyloid oligomer-related neurotoxicity and memory impairment. J. Neurosci. 35, 15157–15169. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4081-14.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker M. D., Boron W. F. (2013). The divergence, actions, roles, and relatives of sodium-coupled bicarbonate transporters. Physiol. Rev. 93, 803–959. 10.1152/physrev.00023.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piacentini R., Gangitano C., Ceccariglia S., Del Fa A., Azzena G. B., Michetti F., et al. (2008). Dysregulation of intracellular calcium homeostasis is responsible for neuronal death in an experimental model of selective hippocampal degeneration induced by trimethyltin. J. Neurochem. 105, 2109–2121. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05297.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popugaeva E., Pchitskaya E., Bezprozvanny I. (2017). Dysregulation of neuronal calcium homeostasis in Alzheimer's disease - a therapeutic opportunity? Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 483, 998–1004. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.09.053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pottorf W. J., II., Johanns T. M., Derrington S. M., Strehler E. E., Enyedi A., Thayer S. A. (2006). Glutamate-induced protease-mediated loss of plasma membrane Ca2+ pump activity in rat hippocampal neurons. J. Neurochem. 98, 1646–1656. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04063.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakers C., Schmid M., Petzold G. C. (2017). TRPV4 channels contribute to calcium transients in astrocytes and neurons during peri-infarct depolarizations in a stroke model. Glia 65, 1550–1561. 10.1002/glia.23183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riccio A., Medhurst A. D., Mattei C., Kelsell R. E., Calver A. R., Randall A. D., et al. (2002). mRNA distribution analysis of human TRPC family in CNS and peripheral tissues. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 109, 95–104. 10.1016/S0169-328X(02)00527-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronco V., Grolla A. A., Glasnov T. N., Canonico P. L., Verkhratsky A., Genazzani A. A., et al. (2014). Differential deregulation of astrocytic calcium signalling by amyloid-beta, TNFalpha, IL-1beta and LPS. Cell Calcium 55, 219–229. 10.1016/j.ceca.2014.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosker C., Graziani A., Lukas M., Eder P., Zhu M. X., Romanin C., et al. (2004). Ca(2+) signaling by TRPC3 involves Na(+) entry and local coupling to the Na(+)/Ca(2+) exchanger. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 13696–13704. 10.1074/jbc.M308108200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruffin V. A., Salameh A. I., Boron W. F., Parker M. D. (2014). Intracellular pH regulation by acid-base transporters in mammalian neurons. Front. Physiol. 5:43. 10.3389/fphys.2014.00043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryazanova L. V., Rondon L. J., Zierler S., Hu Z., Galli J., Yamaguchi T. P., et al. (2010). TRPM7 is essential for Mg(2+) homeostasis in mammals. Nat. Commun. 1:109. 10.1038/ncomms1108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saghy E., Sipos E., Acs P., Bolcskei K., Pohoczky K., Kemeny A., et al. (2016). TRPA1 deficiency is protective in cuprizone-induced demyelination-a new target against oligodendrocyte apoptosis. Glia 64, 2166–2180. 10.1002/glia.23051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samanta A., Hughes T. E. T., Moiseenkova-Bell V. Y. (2018). Transient receptor potential (TRP) channels. Subcell. Biochem. 87, 141–165. 10.1007/978-981-10-7757-9_6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawamura S., Shirakawa H., Nakagawa T., Mori Y., Kaneko S. (2017). TRP channels in the brain: what are they there for?, in Neurobiology of TRP Channels, ed Emir T. L. R. (Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; ), 295–322. 10.4324/9781315152837-16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmiege P., Fine M., Li X. (2018). The regulatory mechanism of mammalian TRPMLs revealed by cryo-EM. FEBS J. 285, 2579–2585. 10.1111/febs.14443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selvaraj S., Sun Y., Singh B. B. (2010). TRPC channels and their implication in neurological diseases. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 9, 94–104. 10.2174/187152710790966650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selvaraj S., Sun Y., Watt J. A., Wang S., Lei S., Birnbaumer L., et al. (2012). Neurotoxin-induced ER stress in mouse dopaminergic neurons involves downregulation of TRPC1 and inhibition of AKT/mTOR signaling. J. Clin. Invest. 122, 1354–1367. 10.1172/JCI61332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selvaraj S., Watt J. A., Singh B. B. (2009). TRPC1 inhibits apoptotic cell degeneration induced by dopaminergic neurotoxin MPTP/MPP(+). Cell Calcium 46, 209–218. 10.1016/j.ceca.2009.07.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigetomi E., Tong X., Kwan K. Y., Corey D. P., Khakh B. S. (2011). TRPA1 channels regulate astrocyte resting calcium and inhibitory synapse efficacy through GAT-3. Nat. Neurosci. 15, 70–80. 10.1038/nn.3000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin H. Y., Hong Y. H., Jang S. S., Chae H. G., Paek S. L., Moon H. E., et al. (2010). A role of canonical transient receptor potential 5 channel in neuronal differentiation from A2B5 neural progenitor cells. PLoS ONE 5:e10359. 10.1371/journal.pone.0010359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirakawa H., Yamaoka T., Sanpei K., Sasaoka H., Nakagawa T., Kaneko S. (2008). TRPV1 stimulation triggers apoptotic cell death of rat cortical neurons. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 377, 1211–1215. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.10.152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui T., Lively S., Ferreira R., Wong R., Schlichter L. C. (2014). Expression and contributions of TRPM7 and KCa2.3/SK3 channels to the increased migration and invasion of microglia in anti-inflammatory activation states. PLoS ONE 9:e106087. 10.1371/journal.pone.0106087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinning A., Hubner C.A. (2013). Minireview: pH and synaptic transmission. FEBS Lett. 587, 1923–1928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sita G., Hrelia P., Graziosi A., Ravegnini G., Morroni F. (2018). TRPM2 in the brain: role in health and disease. Cells 7:82. 10.3390/cells7070082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slanzi A., Iannoto G., Rossi B., Zenaro E., Constantin G. (2020). In vitro models of neurodegenerative diseases. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 8:328. 10.3389/fcell.2020.00328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smaili S., Hirata H., Ureshino R., Monteforte P. T., Morales A. P., Muler M. L., et al. (2009). Calcium and cell death signaling in neurodegeneration and aging. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 81, 467–475. 10.1590/S0001-37652009000300011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits J. J., Oostrik J., Beynon A. J., Kant S. G., De Koning Gans P. a. M., et al. (2019). De novo and inherited loss-of-function variants of ATP2B2 are associated with rapidly progressive hearing impairment. Hum. Genet. 138, 61–72. 10.1007/s00439-018-1965-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J., Lee J. H., Lee S. H., Park K. A., Lee W. T., Lee J. E. (2013). TRPV1 activation in primary cortical neurons induces calcium-dependent programmed cell death. Exp. Neurobiol. 22, 51–57. 10.5607/en.2013.22.1.51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song S., Luo L., Sun B., Sun D. (2020). Roles of glial ion transporters in brain diseases. Glia 68, 472–494. 10.1002/glia.23699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprenkle N. T., Sims S. G., Sanchez C. L., Meares G. P. (2017). Endoplasmic reticulum stress and inflammation in the central nervous system. Mol. Neurodegener. 12:42. 10.1186/s13024-017-0183-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafford N., Wilson C., Oceandy D., Neyses L., Cartwright E. J. (2017). The plasma membrane calcium ATPases and their role as major new players in human disease. Physiol. Rev. 97, 1089–1125. 10.1152/physrev.00028.2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Startek J. B., Boonen B., Talavera K., Meseguer V. (2019). TRP channels as sensors of chemically-induced changes in cell membrane mechanical properties. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20:371. 10.3390/ijms20020371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stauffer T. P., Guerini D., Carafoli E. (1995). Tissue distribution of the four gene products of the plasma membrane Ca2+ pump. A study using specific antibodies. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 12184–12190. 10.1074/jbc.270.20.12184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strehler E. E., Caride A. J., Filoteo A. G., Xiong Y., Penniston J. T., Enyedi A. (2007). Plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPases as dynamic regulators of cellular calcium handling. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1099, 226–236. 10.1196/annals.1387.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strehler E. E., Thayer S. A. (2018). Evidence for a role of plasma membrane calcium pumps in neurodegenerative disease: recent developments. Neurosci. Lett. 663, 39–47. 10.1016/j.neulet.2017.08.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tai C., Hines D. J., Choi H. B., Macvicar B. A. (2011). Plasma membrane insertion of TRPC5 channels contributes to the cholinergic plateau potential in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. Hippocampus 21, 958–967. 10.1002/hipo.20807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi V., Petrozziello T., Sisalli M. J., Boscia F., Canzoniero L. M. T., Secondo A. (2019). The activation of Mucolipin TRP channel 1 (TRPML1) protects motor neurons from L-BMAA neurotoxicity by promoting autophagic clearance. Sci. Rep. 9:10743. 10.1038/s41598-019-46708-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thapak P., Vaidya B., Joshi H. C., Singh J. N., Sharma S. S. (2020). Therapeutic potential of pharmacological agents targeting TRP channels in CNS disorders. Pharmacol. Res. 159:105026. 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.105026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyrtyshnaia A. A., Lysenko L. V., Madamba F., Manzhulo I. V., Khotimchenko M. Y., Kleschevnikov A. M. (2016). Acute neuroinflammation provokes intracellular acidification in mouse hippocampus. J. Neuroinflammation 13:283. 10.1186/s12974-016-0747-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vale-Gonzalez C., Alfonso A., Sunol C., Vieytes M. R., Botana L. M. (2006). Role of the plasma membrane calcium adenosine triphosphatase on domoate-induced intracellular acidification in primary cultures of cerebelar granule cells. J. Neurosci. Res. 84, 326–337. 10.1002/jnr.20878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatachalam K., Montell C. (2007). TRP channels. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 76, 387–417. 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vennekens R., Menigoz A., Nilius B. (2012). TRPs in the brain. Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 163, 27–64. 10.1007/112_2012_8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkhratsky A., Reyes R. C., Parpura V. (2014). TRP channels coordinate ion signalling in astroglia. Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 166, 1–22. 10.1007/112_2013_15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villereal M. L. (2006). Mechanism and functional significance of TRPC channel multimerization. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 17, 618–629. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2006.10.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Spiczak S., Muhle H., Helbig I., De Kovel C. G., Hampe J., Gaus V., et al. (2010). Association study of TRPC4 as a candidate gene for generalized epilepsy with photosensitivity. Neuromolecular Med. 12, 292–299. 10.1007/s12017-010-8122-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Cheng X., Tian J., Xiao Y., Tian T., Xu F., et al. (2020). TRPC channels: structure, function, regulation and recent advances in small molecular probes. Pharmacol. Ther. 209:107497. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Jackson M. F., Xie Y. F. (2016). Glia and TRPM2 channels in plasticity of central nervous system and Alzheimer's diseases. Neural Plast. 2016:1680905. 10.1155/2016/1680905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Lu R., Yang J., Li H., He Z., Jing N., et al. (2015). TRPC6 specifically interacts with APP to inhibit its cleavage by gamma-secretase and reduce Abeta production. Nat. Commun. 6:8876. 10.1038/ncomms9876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M., Bianchi R., Chuang S. C., Zhao W., Wong R. K. (2007). Group I metabotropic glutamate receptor-dependent TRPC channel trafficking in hippocampal neurons. J. Neurochem. 101, 411–421. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04377.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Zhou L., An D., Xu W., Wu C., Sha S., et al. (2019). TRPV4-induced inflammatory response is involved in neuronal death in pilocarpine model of temporal lobe epilepsy in mice. Cell Death Dis. 10:386 10.1038/s41419-019-1691-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong M. M. K., Hoekstra S. D., Vowles J., Watson L. M., Fuller G., Nemeth A. H., et al. (2018). Neurodegeneration in SCA14 is associated with increased PKCgamma kinase activity, mislocalization and aggregation. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 6:99. 10.1186/s40478-018-0600-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolums B. M., Mccray B. A., Sung H., Tabuchi M., Sullivan J. M., Ruppell K. T., et al. (2020). TRPV4 disrupts mitochondrial transport and causes axonal degeneration via a CaMKII-dependent elevation of intracellular Ca(2). Nat. Commun. 11:2679. 10.1038/s41467-020-16411-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D., Huang W., Richardson P. M., Priestley J. V., Liu M. (2008). TRPC4 in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons is increased after nerve injury and is necessary for neurite outgrowth. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 416–426. 10.1074/jbc.M703177200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X., Zagranichnaya T. K., Gurda G. T., Eves E. M., Villereal M. L. (2004). A TRPC1/TRPC3-mediated increase in store-operated calcium entry is required for differentiation of H19-7 hippocampal neuronal cells. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 43392–43402. 10.1074/jbc.M408959200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Z. G., Pignataro G., Li M., Chang S. Y., Simon R. P. (2008). Acid-sensing ion channels (ASICs) as pharmacological targets for neurodegenerative diseases. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 8, 25–32. 10.1016/j.coph.2007.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto S., Wajima T., Hara Y., Nishida M., Mori Y. (2007). Transient receptor potential channels in Alzheimer's disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1772, 958–967. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2007.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T., Swietach P., Rossini A., Loh S. H., Vaughan-Jones R. D., Spitzer K. W. (2005). Functional diversity of electrogenic Na+-HCO3- cotransport in ventricular myocytes from rat, rabbit and guinea pig. J. Physiol. 562, 455–475. 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.071068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H., Li S. (2016). Transient Receptor Potential Ankyrin 1 (TRPA1) channel and neurogenic inflammation in pathogenesis of asthma. Med. Sci. Monit. 22, 2917–2923. 10.12659/MSM.896557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W., Liu J., Zheng F., Jia M., Zhao L., Lu T., et al. (2013). The evidence for association of ATP2B2 polymorphisms with autism in Chinese Han population. PLoS ONE 8:e61021. 10.1371/journal.pone.0061021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaidi A. (2010). Plasma membrane Ca-ATPases: targets of oxidative stress in brain aging and neurodegeneration. World J. Biol. Chem. 1, 271–280. 10.4331/wjbc.v1.i9.271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaidi A., Adewale M., Mclean L., Ramlow P. (2018). The plasma membrane calcium pumps-the old and the new. Neurosci. Lett. 663, 12–17. 10.1016/j.neulet.2017.09.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanni G., Cali T., Kalscheuer V. M., Ottolini D., Barresi S., Lebrun N., et al. (2012). Mutation of plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPase isoform 3 in a family with X-linked congenital cerebellar ataxia impairs Ca2+ homeostasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109, 14514–14519. 10.1073/pnas.1207488109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Z., Leng T., Feng X., Sun H., Inoue K., Zhu L., et al. (2015). Silencing TRPM7 in mouse cortical astrocytes impairs cell proliferation and migration via ERK and JNK signaling pathways. PLoS ONE 10:e0119912. 10.1371/journal.pone.0119912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai K., Liskova A., Kubatka P., Busselberg D. (2020). Calcium entry through TRPV1: a potential target for the regulation of proliferation and apoptosis in cancerous and healthy cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21:4177. 10.3390/ijms21114177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang E., Liao P. (2015). Brain transient receptor potential channels and stroke. J. Neurosci. Res. 93, 1165–1183. 10.1002/jnr.23529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]