Abstract

Introduction

Adipose tissue and adipocytes are primary regulators of insulin sensitivity and energy homeostasis. Defects in insulin sensitivity of the adipocytes predispose the body to insulin resistance (IR) that could lead to diabetes. However, the mechanisms mediating adipocyte IR remain elusive, which emphasizes the need to develop experimental models that can validate the insulin signaling pathways and discover new mechanisms in the search for novel therapeutics. Currently in vitro adipose organ-chip devices show superior cell function over conventional cell culture. However, none of these models represent disease states. Only when these in vitro models can represent both healthy and disease states, they can be useful for developing therapeutics. Here, we establish an organ-on-chip model of insulin-resistant adipocytes, as well as characterization in terms of insulin signaling pathway and lipid metabolism.

Methods

We differentiated, maintained, and induced insulin resistance into primary adipocytes in a microfluidic organ-on-chip. We then characterized IR by looking at the insulin signaling pathway and lipid metabolism, and validated by studying a diabetic drug, rosiglitazone.

Results

We confirmed the presence of insulin resistance through reduction of Akt phosphorylation, Glut4 expression, Glut4 translocation and glucose uptake. We also confirmed defects of disrupted insulin signaling through reduction of lipid accumulation from fatty acid uptake and elevation of glycerol secretion. Testing with rosiglitazone showed a significant improvement in insulin sensitivity and fatty acid metabolism as suggested by previous reports.

Conclusions

The adipose-chip exhibited key characteristics of IR and can serve as model to study diabetes and facilitate discovery of novel therapeutics.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s12195-020-00636-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Insulin resistance, Glucose metabolism, Lipolysis, Microfluidics, Adipocytes, Organ on chips, Diabetes

Introduction

We are in the midst of a world epidemic of obesity and diabetes. Over 2.1 billion people in the world are currently obese or overweight45,77; over one-third of U.S. adults are obese; more than 11% of people aged ≥ 20 years have diabetes,17,77 and the number is projected to increase to 21% by 2050.8 The eventual impact of these metabolic disorders is expected to take a considerable toll on public health.40,65 Therefore, additional work is required to better understand and develop effective therapeutics for these diseases.

Obesity is one of the most common causes of insulin resistance, driving hyperglycemia associated with type 2 diabetes.79 Insulin plays an important role in metabolic homeostasis by stimulating the disposal of postprandial glucose into skeletal muscle and adipose tissue. Insulin has pleiotropic adipose effects mediated by diverse signaling mechanisms, including the path from insulin receptor (IR) to glucose transporter (GLUT4) through the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinasse (PI3K)/Akt pathway.10,33,41,74 This path is mediated by insulin-regulated GLUT4 translocation from intracellular vesicles to the plasma membrane.12,34 Disrupting this process, as mice lacking GLUT4 in adipose tissue caused insulin resistance condition,53 which defined as an impairment of insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in the tissue. Insulin resistance is an important metabolic marker that predisposes an individual for more severe condition in type 2 diabetes patient.29,35 Although the etiology of insulin resistance has been extensively examined,61,71 the mechanisms mediating adipose insulin resistance remain unclear.

To enhance our understanding of the underlying mechanisms mediating insulin resistance (IR), it is imperative to develop better functional adipose (IR) models. Animal models of insulin resistance are greatly useful in type 2 diabetes.3,38 However, to avoid cross-talk among various organ systems, in vitro models are necessary and often complement the in vivo models. One method is to utilize fresh mature isolated adipocytes. However, the buoyancy of these cells introduces difficulties to coperate in cuture model. These cells float to the top of culture medium and rapidly dedifferentiate once attached.2,4,42,69,72,73,78 As a results of technical challenges, in vitro research on adipocytes is often conducted using adipocytes differentiated from their precursors. Several agents are used to develop insulin resistance in adipocytes.30,68,76 The study from Nguyen et al. demonstrated that fatty acid induced insulin resistance in 3T3L1 cells through the JNK pathway disrupted insulin-stimulated glucose GLUT4 translocation.58 Ruan et al. developed an insulin resistant model by inducing TNF-α into differentiated 3T3-L1 cells. This study reported that TNF-α reduced GLUT4 and several insulin signaling proteins. TNF-α also induced changes in gene expression through NF-kB leading to an insulin resistance in adipocytes.64 Victoria et al. developed insulin resistant model by inducing or IL-6 into differentiated 3T3-L1 cells. In contrast to TNF-α, IL-6 does not activate JNK or increase phosphorylation of serine 307 or serine 612 or IRS-1.63 TNF-α overexpression causes insulin resistance in several isolated primary cells.26,70 Recent advances in in vitro technology called organ on chips were established with the promise of better representation of the physiological conditions for the cells.14,28,37,82 Several groups including ours, have created adipose-on-chip devices, which show superior cells function over conventional cell culture devices for both short term culture18,44,45,47,48,55 and long term culture.1,75,81 The devices support homogeneous transport of nutrients and removal of waste1,45,47 as well as modulation of fluidic shear stress.75 As these models become mature, a gap that remains in the field is that the models do not represent disease states. The purpose of this study is to establish an insulin resistant adipose-on-chip device. In this work, we established adipose (IR) model by inducing primary adipocytes with TNF-α and systematically analyzed a range of biological actions of insulin in the insulin signaling pathway and lipid metabolism. Our proposed model would complement the existing rodent model of IR and type 2 diabetes and serve as a novel disease model to strengthen the applicability of drug screening for type2 diabetes treatment. Only when these in vitro models can represent both healthy and disease states, they can be highly benificial in modeling diseases for screening drugs.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Wild-type male mice on C57Bl/6 J (Jackson laboratory, Sacramento, CA), between 6 and 8 weeks old, were treated in accordance with Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) guidelines. Mice were housed in a temperature-controlled environment on a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle at 24 °C for 1 week. They were allowed ad libitum access to standard chow (5001 Rodent Diet, LabDiet, St. Louis, MO) and water.

Microfluidic Device Fabrication

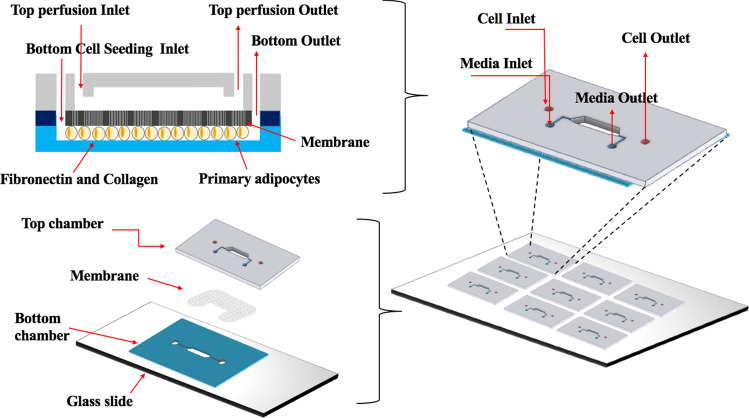

A dual-layer, membrane-based microfluidic devices (Fig. 1) were fabricated as described previously.60 Briefly, a negative photoresist silicon wafer was used as a mold to fabricate a top chamber in Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS, Sylgard 184, Down Corning, Midland, MI) via standard soft-lithography protocols.52 Both inlet and outlet ports were punched into the top PDMS chamber using a 0.75 mm dermal punch (World precision instruments, Sarasota, FL). A 1.0 μm pore-sized polycarbonate (PC) membrane (3 × 106 pores cm−2, 24 μm thickness; AR Brown-US, Pittsburgh, PA) were cut to the patterned shape using laser cutter. The bottom chamber was created from ∼ 250 μm thick silicone (Rogers Corporation, Carol Stream, IL) by laser cutter. The top chamber was first bonded to the membrane using spin coated PDMS pre-polymer. Then, the bottom chamber was boned to the glass slide using air plasma treatment. The membraned-bound top layer and bottom chamber were finally aligned and firmly bonded prior baking at 70 °C for 30 min. All microfluidic devices were UV-sterilized for 30 min and bottom chamber was coated with 50 μg ml−1 collagen and fibronectin bovine protein (ThermoFisher Scientific, Grand Island, NY) before inducing primary murine preadipocytes.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of dual-layer device fabrication.

Model of Insulin Resistance

Subcutaneous white adipose tissues of 6–8 week-old male C57BL/6 mice were excised to isolate precursor cells according to the protocol5 and differentiated into mature adipocytes using a protocol we have published.75 In brief, a suspension of purified primary murine preadipocytes at 4 million cells (M) ml−1 was loaded into the bottom cell chamber in basal media (DMEM/F12 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum and 2% antibiotic–antimycotic). After 24 h culture, adipogenic differentiation was initiated under perfusion at at 5 μl h−1 using induction media (basal media supplemented with 5 μg ml−1 of insulin, 125 μM of Indomethacin, 2 μg ml−1 of Dexamethasone, and 0.5 mM of 3-Isobutyl-1-methylxan- thine [IBMX]). After 48 h, the cells were cultured in maintenance media (basal media supplemented with 5 μg ml−1 of insulin, 125 μM) under perfusion. Prior to the treatment (day 14), cells were starved for 18–20 h in treatment medium (DMEM/F12, 0.02% BSA, and 2% antibiotic–antimycotic). The differentiated cells were submitted to two different treatments under perfusion. First, the cells were induced to insulin resistance by treated with 20 ng ml−1 TNF-α for 24 h.21 Second, the cells were induced to insulin resistance and treated with 10 μM rosiglitazone for 24 h.32 After the above treatments, the cells were pretreated as following prior assessment of insulin-regulated process. For non-insulin stimulation, the cells were washed with PBS and perfused with basal medium for 30 min. For insulin stimulation, the cells were washed with PBS and perfused with 100 nM insulin in basal medium for 30 min.

Lipid Droplets Staining

After adipogenic differentiation, adipocytes were washed with PBS 1×, stained with AdipoRed™ (1:20), Hoechst (1:1000), and incubated at 37 °C for 40 min. After incubation, the cells were rinsed with PBS 1× and imaged using Niko n Ti inverted fluorescent microscope. Lipid accumulation were characterized via Image J-NIH using intensity analysis tool and normalized with cells number.

Western Blotting Analysis

After adipogenic differentiation or TNF-α or rosiglitazone treatment, adipocytes were washed twice with cold PBS before harvesting with cell lysis buffer (ThermoFischer Scientific, Grand Island, NY). Lysates were centrifuged at 14,000×g for 15 min. Protein content in the supernatants was quantified using bicinchoninic acid protein (BCA) assay kit (ThermoFischer Scientific, Grand Island, NY). pAkt ser 473, Akt, and β-actin protein content was analyzed by auto-western blot at Ray Biotech live (Norcross, GA).

Glucose Uptake

Prior glucose uptake analysis, the cells were incubated with serum free media (DMEM/F12 containing 0.02% BSA and 2% antibiotic–antimycotic) overnight. The cells, were then washed twice with Krebs–Ringer phosphate buffer (0.6 mM Na2 HPO4, 0.4 mM NaH2PO4, 120 mM NaCl, 6 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 12.5 mM HEPES, pH 7.4) supplemented with 0.2% BSA. The cells were later incubated with 200 μg ml−1 2-NBDG for 1 h. Then, the cells were washed with PBS. Glucose uptake by mature adipocytes was detected via glucose uptake cell-based assay kit (Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI). The fluorescence was detected at an excitation/emission wavelength of 485 nm/535 nm.

GLUT-4 Transporter Localization

Prior GLUT-4 detection, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde aqueous solution (Sigma-Aldrich, Milwaukee, WI). The cells were then permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X 100 in PBS. After blocking with Image-iT FX Signal Enchancer (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), the cells were incubated with GLUT4 antibody (1:200, Fabgennix International Inc, Frisco, TX) overnight. The cells were later washed with PBS and stained with Hoechst (1:1000) and incubated for 40 min. After incubation, the cells were rinsed with PBS and imaged using Nikon Ti inverted fluorescent microscope. The fluorescent intensity of total GLUT-4 expression was quantified using intensity analysis via Image J-NIH. Total number of cells from Hoechst staining was determined by quantification of number of nuclei with particles analysis via Image J-NIH. Total intensity of GLUT4 expression was normalized by cells number.

Fatty Acid Uptake

To observe fatty acid uptake in mature adipocytes, the cells were perfused with fluorescently-labeled fatty acid analog. Briefly, the cells were perfused with basal media supplemented with 4 μM 4,4-difluoro-5-methyl-4-bora-3a,4a-diaza-s-indacene-3-dodecanoic acid (BODIPY D-3823, Molecular Probes) for 24 h. The cells were then washed with PBS and stained with Hoechst (1:1000) and incubated for 40 min. Quantification of fatty acid uptake were characterized using Image J-NIH using intensity analysis tool and normalized with cells number.

Lipolysis Assay

The cells were washed twice with PBS and incubated with 0.1 μM isoproterenol in Hanks’ Balanced Salt solution (HBSS) at 37 °C for 2 h. After incubation, media samples were collected and stored at − 80 °C until the assays were performed. Frozen samples were thawed and immediately analyzed using picoprobe free glycerol fluoro- metric assay kit (BioVision, Milpitas, CA) according to manufacturer’s protocol.

Statistics

The data was presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of at least three devices from each independent experiment. Statistical analyses were performed using t tests, one-way analysis of variance or two-way analysis of variance using SPSS (IBM, Armonk, NY). Significant differences were defined as p < 0.05.

Results

Adipose-on-Chip Construct

To establish in vivo-like cellular microenvironments for adipocytes, we developed a dual-layer microfluidic device (Fig. 1) that contains three compartments: media chamber (top chamber), micro porous membrane, and cell chamber (bottom chamber). The porous membrane acts as a cell barrier which allows only diffusive transport through small pores (1 μm). That cell barrier mimics in vivo endothelial cell and extracellular matrix-barrier by allowing fresh nutrients diffuse to the cells while protecting the cells from direct shear stress.

Lipid Droplets Staining

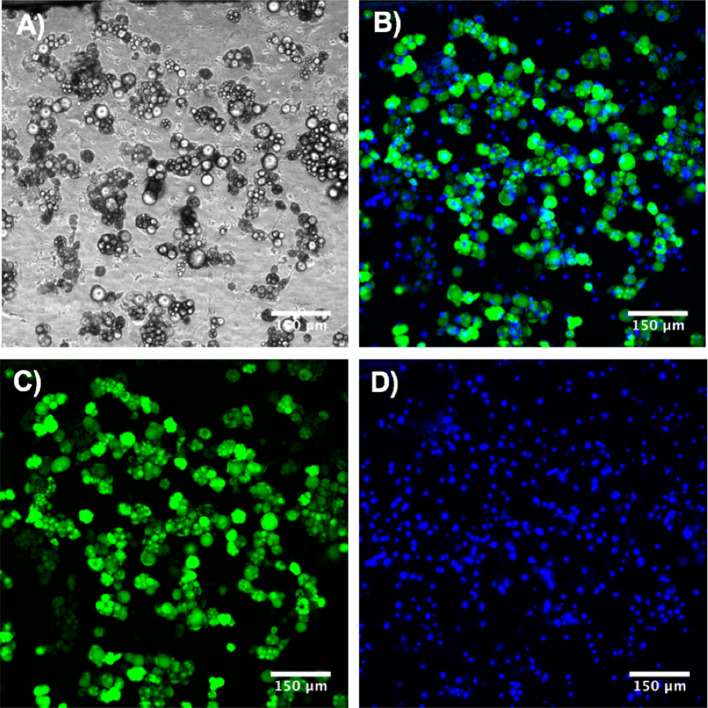

In this study, we culture and differentiate adipocytes into mature adipocytes under perfusion system before starting to induce adipocytes into insulin resistant state. To confirm differentiation of primary adipocytes into mature adipocytes, we use a lipophilic dye, AdipoRed™, to stain the lipid droplets and a nuclear dye to stain nucleus of the cells. After adipogenic differentiation, lipid droplets could clearly be seen accumulating in the mature adipocytes and about 70–80% of the cells differentiated into mature adipocytes were observed (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Adipogenic differentiation of preadipocytes in chip model. (a) Bright field image. (b–d) Fluorescence microscopy image. Cells were stained with a lipophilic dye (AdipoRed™, green = lipids) and nuclear dye (Hoechst, blue = nuclei).

Akt Signaling in Adipose Insulin Resistant Chip Model

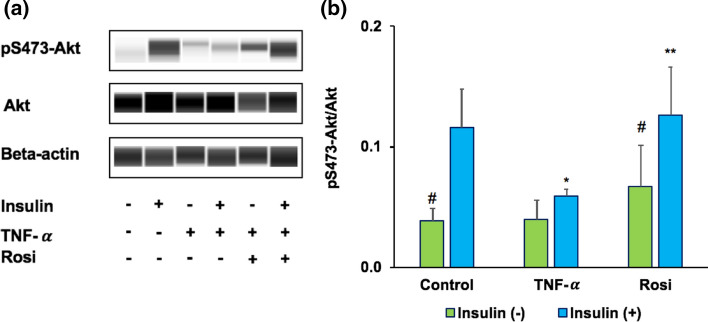

The metabolic action of insulin is largely mediated through the activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) and its downstream effectors, the Akt kinases.80 Consistent with a central role of PI3K/Akt pathway in insulin action, deregulation of downstream Akt phosphorylation is proposed as a hallmark of insulin-resistant tissues.13 TNF-α is considered as a link between adiposity and insulin resistance due to its highly expression in obese and type 2 diabetes patients.54 Consistent with this, over exposure of adipocytes to TNF-α led to an insulin resistant state.25,70 In our proposed model, insulin resistance was induced in the adipocytes with TNF-α perfusion. In TNF-α treated adipocytes, insulin-stimulated phosphorylation of Akt at Ser473 was significantly impaired (47.07% ± 14; p < 0.05), while rosiglitazone (Rosi) treated cells, the insulin-induced phosphorylation of Akt was significantly upregulated (49.99% ± 17; p < 0.05) (Fig. 3). These results confirm disruption of insulin signaling pathway and insulin resistant state in our adipose (IR) chip model.

Figure 3.

Phosphorylation of the Akt signaling in adipose insulin resistant chip model. (a) Control, TNF-α, and Rosi groups were treated with or without 100 nM insulin. Cell lysates were immunoblotted using indicated phospho and total antibodies. (b) Quantification of the blots depicted in n = 3 independent experiments. *p < 0.05 TNF-α vs. control group within the same treatment of insulin. **p < 0.05 Rosi vs. TNF-α group within the same treatment of insulin. #p < 0.05 insulin (−) vs. insulin (+).

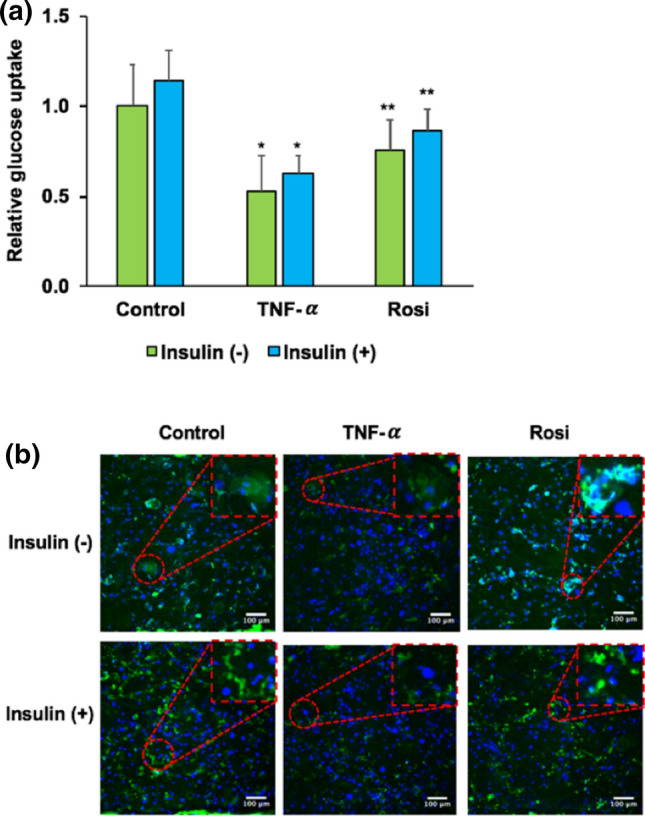

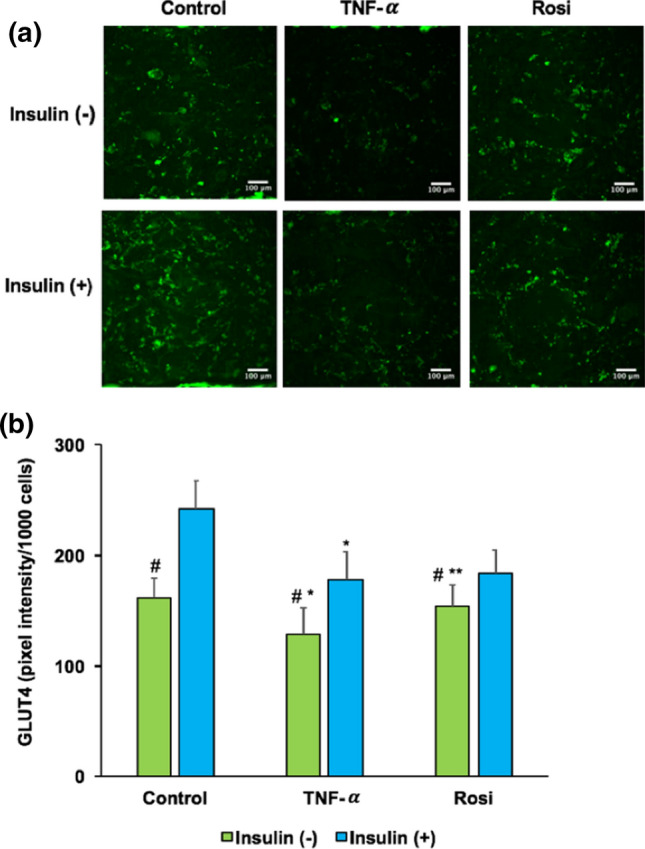

Insulin Stimulated Glucose Transport in Adipose Insulin Resistant Chip Model

Impaired glucose uptake has been suggested as a mechanism of insulin resistance in adipocytes. In this study, we observed glucose uptake in adipocytes by employing 2-NBDG, a fluorescently-labeled deoxyglucose analog. Glucose uptake was significantly reduced in TNF-α treated cells while significantly increased in rosiglitazone treated cells (p < 0.05) (Fig. 4a). No significant changes in glucose uptake was observed between insulin and non-insulin stimulation groups. Then, we further evaluated the presence of insulin resistance and treatment via insulin simulated GLUT4 translocation. We observed lower GLUT4 translocation to plasma membrane in TNF-α treated cells and a consistent restoration of GLUT4 translocation upon treatment with rosiglitazone (Fig. 4b). To confirm the presence of insulin resistance and the effect of rosiglitazone treatment in the adipose-chip model, we next investigated total GLUT4 expression via fluorescence microscopy of immunocytochemically stained cells and quantified by ImageJ. Total GLUT4 expression was determined by total GLUT4 intensity normalized to the nuclear fluorescence number. As shown in Fig. 5a, lower total GLUT4 transporters were clearly observed in TNF-α treated cells while higher total GLUT4 transporters were observed in rosiglitazone treated cells. This data was confirmed by the quantification of total GLUT4 expression in Fig. 5b (p < 0.05). Strikingly, we observed the significant change in total GLUT4 expression between insulin and non-insulin stimulation groups. These results confirm insulin resistance in the adipose-chip and the potential of glucose uptake restoration via rosiglitazone treatment.

Figure 4.

Insulin stimulated glucose up take and GLUT4 translocation in adipose insulin resistant chip model. Control, TNF-α, and Rosi groups were treated with or without 100 nM insulin. (a) Relative 2-NBDG uptake in primary adipocytes. (b) Immunostaining of GLUT 4 (green color) and nuclei (blue color). Data shown here are normalized to control without insulin stimulation group. *p < 0.05 TNF-α vs. control group within the same treatment of insulin. **p < 0.05 Rosi vs. TNF-α group within the same treatment of insulin. #p < 0.05 insulin (−) vs. insulin (+).

Figure 5.

Insulin stimulated glucose transporter GLUT4 expression in adipose insulin resistant chip model. Control, TNF-α, and Rosi groups were treated with or without 100 nM insulin. (a) Immunolocalization by inverted fluorescent microscopy of glucose transporter GLUT4 (green color). (b) Quantitative analysis of total GLUT4 expression. *p < 0.05 TNF-α vs. control group within the same treatment of insulin. **p < 0.05 Rosi vs. TNF-α group within the same treatment of insulin. #p < 0.05 insulin (−) vs. insulin (+).

Fatty Acid Uptake in Adipose Insulin Resistant Model on Chip

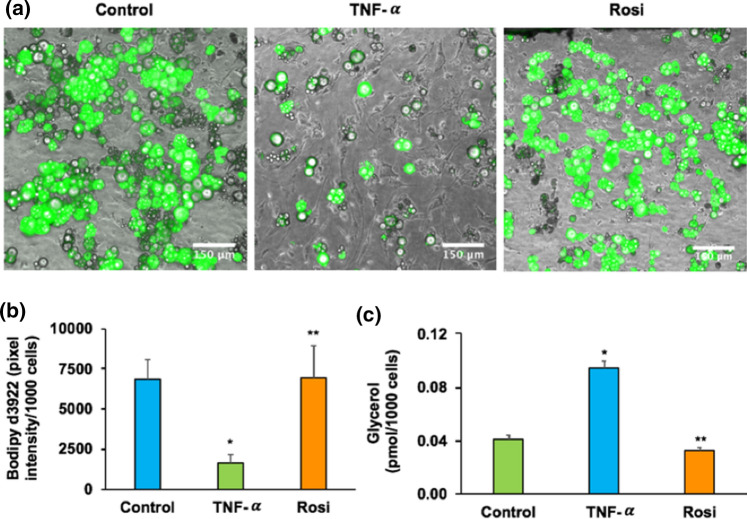

Intriguingly, insulin resistant state does not only impair glucose metabolism in adipose, but also fatty acids uptake and lipolysis.9,66 To assess fatty acid uptake, we next perfused the adipocytes in chip model with medium containing BSA-bound fluorescently-labeled fatty acid analog (D-3823). The expression and quantification of fatty acid uptake was conducted via fluorescence microscopy. As shown in Figs. 6a and 6b, fatty acid uptake was significantly reduced in TNF-α treated cells but significantly increased in rosiglitazone treated cells (p < 0.05). Isoproterenol-stimulated glycerol secretion was significantly enhanced in TNF-α treated cells but significantly reduced in rosiglitazone treated cells (p < 0.05) (Fig. 6c).

Figure 6.

Fatty acid uptake and lipolysis analysis in adipose insulin resistant chip model. (a) Fluorescent microscopy image of labeled fatty acids analog C1-Bodipy-C12 taken by primary adipocytes. (b) Quantitative analysis of total fatty acids uptake. (c) Isoproterenol-stimulated glycerol release. *p < 0.05 TNF-α vs. control group within the same treatment of insulin. **p < 0.05 Rosi vs. TNF-α group within the same treatment of insulin.

Discussion

Even though insulin resistance has been considered as one of the earlier indicators of metabolic diseases including obesity and type 2 diabetes, the insight molecular mechanism mediating adipose insulin resistance remains elusive. Therefore, development of methodology to investigate adipocytes and their metabolic status under insulin resistance is highlighted. The recent observation of selective insulin resistance in adipocytes under static culture24,43,74 has been added to exemplify the complexity of selectivity of insulin resistance in glucose metabolism. However, dynamic in vitro cultures have significant advantages over static cultures. Cell function is improved under in vitro dynamic culture compared to conventional static culture.31,45 The dynamics emulate in vivo interactions by allowing dynamic control of nutrient supply via perfusion, waste removal, and offer the integation of multiple cell types towards human beings to study the interaction between organs.37,62

Insulin regulates a variety of cellular processes in adipocytes, such as glucose transport, fatty acid uptake, and lipolysis.11,16,50 Several actions of insulin are mediated through PI3K/Akt pathway. Akt is a key marker for most metabolic actions of insulin, and its activity is regulated by phosphorylation at Ser-473.13 Deregulation of Akt phosphorylation has been considered as a hall mark of insulin resistant models.13 TNF-α is highly pro-inflammatory cytokine that highly expressed in obese and type 2 diabetes patients.54 Over exposure of TNF-α to adipocytes developed an insulin resistant state.25,70 Consistent with this, our data highlighted the reduction of Akt phosphorylation at Ser 473 in mature adipocytes after 24 h of TNF-α treatment under dynamic system. This finding was similar to previous reports.19,24,57,59,67 Corresponding to the IR status of the adipocytes, we further observed reduction of glucose uptake, reduction of total GLUT4 expression and impaired insulin stimulated GLUT4 translocation after TNF-α treatment. This data was consistent with the previous studies.24,74 Notably, this result suggests the potential consequence of chronic exposure to TNF-α and confirmed defects of PI3K/Akt in our adipose (IR) chip model. It is likely that such defects contributed to reduce the total GLUT4 expression, limit GLUT4 translocation into the membrane39 and led to a reduction of glucose entry into target tissues.53 We further observed reduction of fatty acid uptake and an increase of glycerol secretion after TNF-α treatment. One possible explanation for these data is that TNF-α stimulates lipolysis, which led to a reduction of lipid accumulation form fatty acid uptake in adipocytes IR group. This result supports these previous findings20,27 and the literature that lipolysis is elevated during obesity and insulin resistance.22,56

To observe adipocytes IR response to diabetic drugs. Rosiglitazone at concentration 10 μM was tested on our IR cells. Rosiglitazone, in particular, is an insulin-sensitizing agent that maintains the glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes.49 After 24 h of rosiglitazone treatment, we observed fully reversed of Akt phosphorylation, an increase of glucose uptake, higher GLUT4 expression and translocation, an elevated of fatty acid uptake, and a reduction of glycerol secretion. Our data are also in agreement with the previous studies.23,32,36,51 Collectively, these results suggest the potential of rosiglitazone for insulin resistant treatment and confirm a capability of our adipose (IR) chip model for drug screening.

After adipogenic differentiation, we observed about 70–80% of mature adipocytes with lipid droplets (Fig. 2). We also confirmed that the cells those have nuclei presented without lipid accumulation are viable (Fig. 1S). In this study, the pre-adipocytes were isolated from stromal vascular fraction as described previously.5 Since we did not further purify the cell population by cell sorting, it is possible that that the isolated cells population does not consist of purely adipocytes, and the other cells likely would not respond to the adipogenic differentiation.

Even though the heterogenous cell population may represent the adipose-tissue better than pure-population of adipocytes, we will purify the cell population in the future. We used 100 nM insulin following prior published work.24,46,74 Exposing the cells to a lower insulin level will be more physiological, although the effects could take much longer to manifest. Our results show that all different insulin treatments showed similar results as before that TNF-α suppressed Akt phosphorylation while rosiglitazone upregulated Akt phosphorylation (Fig. 2S). Glucose can be taken up by adipocytes through multiple transporters including GLUT1, GLUT 2, and GLUT4. However, only GLUT4 is insulin-dependent. Our results only indicate the changes in glucose uptake due to insulin-dependent transporter, GLUT4. The other glucose transporters are still functional. Our results support previous work that there is insulin has limited effect in glucose uptake in adipocytes.45

Our current model has effectively expanded the knowledge related to adipocytes metabolic function under normal and disease stage which can be further used to study adipogeneis, disease development and diabetic drug screening. In the future, macrophages could be added to the adipocytes to mimic the macrophage-induced insulin resistance which is seen in obese patients6,7,15 and lower physiological doses of insulin could be added to observe insulin signaling pathway.

Conclusion

We have established an in vitro organ-on-chip model for insulin resistant adipose. We have confirmed a reduction of Akt phosphorylation, GLUT4 expression, and glucose uptake in the IR cells. We also confirmed defects of disrupted insulin signaling through reduction of fatty acid synthase and elevation of glycerol secretion. Testing a known diabetic drug, rosiglitazone, showed a significant improvement in insulin sensitivity and lipid metabolism. In conclusion, these data demonstrate that our insulin resistant adipose-chip model exhibits key characteristics of insulin resistance and can serve as a novel disease model to complement the existing rodent model of type 2 diabetes for drug screening. These in vitro models can be highly beneficial only for drug screening when they can represent both healthy and disease states.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge support from the Diabetes Research and Training Center (DRTC) at the University of Chicago. We gratefully acknowledge Dr. Nick Menhart and the Idea shop at Illinois Institute of Technology for technical assistance. We thank Dr. Gokhan Dalgin at University of Chicago for assistance with qPCR.

Funding

This work was supported by DRTC Grant P30 DK020595 and student scholarships from the Armor College of Engineering.

Conflict of interest

Authors Nida Tanataweethum, Franklin Zhong, Allyson Trang, Chaeeun Lee, Ronald N. Cohen, Abhinav Bhushan declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

The studies were conducted with the approval and in accordance with Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) guidelines. This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Abbott RD, Raja WK, Wang RY, Stinson JA, Glettig DL, Burke KA, Kaplan DL. Long term perfusion system supporting adipogenesis. Methods. 2015;84:84–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2015.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adebonojo FO. Studies on human adipose cells in culture: relation of cell size and multiplication to donor age. Yale J. Biol. Med. 1975;48(1):9–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Awar A, Kupai K, Veszelka M, Szucs G, Attieh Z, Murlasits Z, Torok S, Posa A, Varga C. Experimental diabetes mellitus in different animal models. J. Diabetes Res. 2016;2016:9051426. doi: 10.1155/2016/9051426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asada S, Kuroda M, Aoyagi Y, Fukaya Y, Tanaka S, Konno S, Tanio M, Aso M, Satoh K, Okamoto Y, Nakayama T, Saito Y, Bujo H. Ceiling culture-derived proliferative adipocytes retain high adipogenic potential suitable for use as a vehicle for gene transduction therapy. Am. J. Physiol. 2011;301(1):C181–C185. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00080.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aune UL, Ruiz L, Kajimura S. Isolation and differentiation of stromal vascular cells to beige/brite cells. J. Visual. Exp. 2013;73:e50191. doi: 10.3791/50191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bjorndal B, Burri L, Staalesen V, Skorve J, Berge RK. Different adipose depots: their role in the development of metabolic syndrome and mitochondrial response to hypolipidemic agents. J. Obes. 2011;2011:490650. doi: 10.1155/2011/490650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boutens L, Stienstra R. Adipose tissue macrophages: going off track during obesity. Diabetologia. 2016;59(5):879–894. doi: 10.1007/s00125-016-3904-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyle JP, Thompson TJ, Gregg EW, Barker LE, Williamson DF. Projection of the year 2050 burden of diabetes in the us adult population: dynamic modeling of incidence, mortality, and prediabetes prevalence. Popul. Health Metr. 2010;8(1):29. doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-8-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cawthorn WP, Sethi JK. Tnf-alpha and adipocyte biology. FEBS Lett. 2008;582(1):117–131. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.11.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen FC, Shen KP, Chen JB, Lin HL, Hao CL, Yen HW, Shaw SY. Pgbr extract ameliorates tnf-alpha induced insulin resistance in hepatocytes. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2018;34(1):14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.kjms.2017.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi SM, Tucker DF, Gross DN, Easton RM, DiPilato LM, Dean AS, Monks BR, Birnbaum MJ. Insulin regulates adipocyte lipolysis via an akt-independent signaling pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2010;30(21):5009–5020. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00797-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cong LN, Chen H, Li Y, Zhou L, McGibbon MA, Taylor SI, Quon MJ. Physiological role of akt in insulin-stimulated translocation of glut4 in transfected rat adipose cells. Mol. Endocrinol. 1997;11(13):1881–1890. doi: 10.1210/mend.11.13.0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cusi K, Maezono K, Osman A, Pendergrass M, Patti ME, Pratipanawatr T, DeFronzo RA, Kahn CR, Mandarino LJ. Insulin resistance differentially affects the pi 3-kinase- and map kinase-mediated signaling in human muscle. J. Clin. Invest. 2000;105(3):311–320. doi: 10.1172/JCI7535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edington CD, Chen WLK, Geishecker E, Kassis T, Soenksen LR, Bhushan BM, Freake D, Kirschner J, Maass C, Tsamandouras N, Valdez J, Cook CD, Parent T, Snyder S, Yu J, Suter E, Shockley M, Velazquez J, Velazquez JJ, Stockdale L, Papps JP, Lee I, Vann N, Gamboa M, LaBarge ME, Zhong Z, Wang X, Boyer LA, Lauffenburger DA, Carrier RL, Communal C, Tannenbaum SR, Stokes CL, Hughes DJ, Rohatgi G, Trumper DL, Cirit M, Griffith LG. Interconnected microphysiological systems for quantitative biology and pharmacology studies. Sci. Rep. 2018;8(1):4530. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-22749-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Engin AB. Adipocyte-macrophage cross-talk in obesity. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017;960:327–343. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-48382-5_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fain JN, Kovacev VP, Scow RO. Antilipolytic effect of insulin in isolated fat cells of the rat. Endocrinology. 1966;78(4):773–778. doi: 10.1210/endo-78-4-773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Finkelstein EA, Khavjou OA, Thompson H, Trogdon JG, Pan L, Sherry B, Dietz W. Obesity and severe obesity forecasts through 2030. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2012;42(6):563–570. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Godwin LA, Brooks JC, Hoepfner LD, Wanders D, Judd RL, Easley CJ. A microfluidic interface for the culture and sampling of adiponectin from primary adipocytes. Analyst. 2015;140(4):1019–1025. doi: 10.1039/c4an01725k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gonzalez E, Flier E, Molle D, Accili D, McGraw TE. Hyperinsulinemia leads to uncoupled insulin regulation of the glut4 glucose transporter and the foxo1 transcription factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108(25):10162–10167. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019268108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Green A, Rumberger JM, Stuart CA, Ruhoff MS. Stimulation of lipolysis by tumor necrosis factor-alpha in 3t3-l1 adipocytes is glucose dependent: implications for long-term regulation of lipolysis. Diabetes. 2004;53(1):74–81. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.1.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guedes JAC, Esteves JV, Morais MR, Zorn TM, Furuya DT. Osteocalcin improves insulin resistance and inflammation in obese mice: participation of white adipose tissue and bone. Bone. 2018;115:68–82. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2017.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guilherme A, Virbasius JV, Puri V, Czech MP. Adipocyte dysfunctions linking obesity to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;9(5):367–377. doi: 10.1038/nrm2391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hernandez R, Teruel T, de Alvaro C, Lorenzo M. Rosiglitazone ameliorates insulin resistance in brown adipocytes of wistar rats by impairing tnf-alpha induction of p38 and p42/p44 mitogen-activated protein kinases. Diabetologia. 2004;47(9):1615–1624. doi: 10.1007/s00125-004-1503-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoehn KL, Hohnen-Behrens C, Cederberg A, Wu LE, Turner N, Yuasa T, Ebina Y, James DE. Irs1-independent defects define major nodes of insulin resistance. Cell. Metab. 2008;7(5):421–433. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hotamisligil GS, Murray DL, Choy LN, Spiegelman BM. Tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibits signaling from the insulin receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91(11):4854–4858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.4854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hotamisligil GS, Peraldi P, Budavari A, Ellis R, White MF, Spiegelman BM. Irs-1-mediated inhibition of insulin receptor tyrosine kinase activity in tnf-alpha- and obesity-induced insulin resistance. Science. 1996;271(5249):665–668. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5249.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hube F, Hauner H. The role of tnf-alpha in human adipose tissue: prevention of weight gain at the expense of insulin resistance? Horm. Metab. Res. 1999;31(12):626–631. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-978810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huh D, Hamilton GA, Ingber DE. From 3d cell culture to organs-on-chips. Trends Cell Biol. 2011;21(12):745–754. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hupfeld, C. J., C. H. Courtney, and J. M. Olefsky. Type 2 diabetes mellitus: etiology, pathogenesis, and natural history. In: Endocrinology, edited by L.J. DeGroot. 2010, pp. 765–787

- 30.Jager J, Gremeaux T, Cormont M, Le Marchand-Brustel Y, Tanti JF. Interleukin-1beta-induced insulin resistance in adipocytes through down-regulation of insulin receptor substrate-1 expression. Endocrinology. 2007;148(1):241–251. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jang M, Neuzil P, Volk T, Manz A, Kleber A. On-chip three-dimensional cell culture in phaseguides improves hepatocyte functions in vitro. Biomicrofluidics. 2015;9(3):034113. doi: 10.1063/1.4922863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jiang G, Dallas-Yang Q, Biswas S, Li Z, Zhang BB. Rosiglitazone, an agonist of peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptor gamma (ppargamma), decreases inhibitory serine phosphorylation of irs1 in vitro and in vivo. Biochem. J. 2004;377(Pt 2):339–346. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jiang ZY, Zhou QL, Coleman KA, Chouinard M, Boese Q, Czech MP. Insulin signaling through akt/protein kinase b analyzed by small interfering rna-mediated gene silencing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100(13):7569–7574. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1332633100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kahn BB, Horton ES, Cushman SW. Mechanism for enhanced glucose transport response to insulin in adipose cells from chronically hyperinsulinemic rats: increased translocation of glucose transporters from an enlarged intracellular pool. J. Clin. Invest. 1987;79(3):853–858. doi: 10.1172/JCI112894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kahn SE, Hull RL, Utzschneider KM. Mechanisms linking obesity to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2006;444(7121):840–846. doi: 10.1038/nature05482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karlsson HK, Hallsten K, Bjornholm M, Tsuchida H, Chibalin AV, Virtanen KA, Heinonen OJ, Lonnqvist F, Nuutila P, Zierath JR. Effects of metformin and rosiglitazone treatment on insulin signaling and glucose uptake in patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled study. Diabetes. 2005;54(5):1459–1467. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.5.1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kimura H, Sakai Y, Fujii T. Organ/body-on-a-chip based on microfluidic technology for drug discovery. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2018;33(1):43–48. doi: 10.1016/j.dmpk.2017.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.King AJ. The use of animal models in diabetes research. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2012;166(3):877–894. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.01911.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kohn AD, Summers SA, Birnbaum MJ, Roth RA. Expression of a constitutively active akt ser/thr kinase in 3t3-l1 adipocytes stimulates glucose uptake and glucose transporter 4 translocation. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271(49):31372–31378. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.49.31372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lahey R, Khan SS. Trends in obesity and risk of cardiovascular disease. Curr. Epidemiol. Rep. 2018;5(3):243–251. doi: 10.1007/s40471-018-0160-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Laviola L, Perrini S, Cignarelli A, Natalicchio A, Leonardini A, De Stefano F, Cuscito M, De Fazio M, Memeo V, Neri V, Cignarelli M, Giorgino R, Giorgino F. Insulin signaling in human visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue in vivo. Diabetes. 2006;55(4):952–961. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.55.04.06.db05-1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lessard J, Pelletier M, Biertho L, Biron S, Marceau S, Hould FS, Lebel S, Moustarah F, Lescelleur O, Marceau P, Tchernof A. Characterization of dedifferentiating human mature adipocytes from the visceral and subcutaneous fat compartments: fibroblast-activation protein alpha and dipeptidyl peptidase 4 as major components of matrix remodeling. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(3):e0122065. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li S, Brown MS, Goldstein JL. Bifurcation of insulin signaling pathway in rat liver: Mtorc1 required for stimulation of lipogenesis, but not inhibition of gluconeogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107(8):3441–3446. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914798107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li X, Easley CJ. Microfluidic systems for studying dynamic function of adipocytes and adipose tissue. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2018;410(3):791–800. doi: 10.1007/s00216-017-0741-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu Y, Kongsuphol P, Gourikutty SBN, Ramadan Q. Human adipocyte differentiation and characterization in a perfusion-based cell culture device. Biomed. Microdevices. 2017;19(3):18. doi: 10.1007/s10544-017-0164-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu T, Yu B, Kakino M, Fujimoto H, Ando Y, Hakuno F, Takahashi S-I. A novel irs-1-associated protein, dgkζ regulates glut4 translocation in 3t3-l1 adipocytes. Sci. Rep. 2016;6(1):35438. doi: 10.1038/srep35438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Loskill P, Sezhian T, Tharp KM, Lee-Montiel FT, Jeeawoody S, Reese WM, Zushin PH, Stahl A, Healy KE. Wat-on-a-chip: a physiologically relevant microfluidic system incorporating white adipose tissue. Lab. Chip. 2017;17(9):1645–1654. doi: 10.1039/c6lc01590e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lu S, Dugan CE, Kennedy RT. Microfluidic chip with integrated electrophoretic immunoassay for investigating cell–cell interactions. Anal. Chem. 2018;90(8):5171–5178. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b05304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Malinowski JM, Bolesta S. Rosiglitazone in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a critical review. Clin Ther. 2000;22(10):1151–1168. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(00)83060-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marshall S. Kinetics of insulin action on protein synthesis in isolated adipocytes. Ability of glucose to selectively desensitize the glucose transport system without altering insulin stimulation of protein synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264(4):2029–2036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Martinez L, Berenguer M, Bruce MC, Le Marchand-Brustel Y, Govers R. Rosiglitazone increases cell surface glut4 levels in 3t3-l1 adipocytes through an enhancement of endosomal recycling. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2010;79(9):1300–1309. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McDonald JC, Chabinyc ML, Metallo SJ, Anderson JR, Stroock AD, Whitesides GM. Prototyping of microfluidic devices in poly(dimethylsiloxane) using solid-object printing. Anal Chem. 2002;74(7):1537–1545. doi: 10.1021/ac010938q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Minokoshi Y, Kahn CR, Kahn BB. Tissue-specific ablation of the glut4 glucose transporter or the insulin receptor challenges assumptions about insulin action and glucose homeostasis. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278(36):33609–33612. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R300019200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mishima Y, Kuyama A, Tada A, Takahashi K, Ishioka T, Kibata M. Relationship between serum tumor necrosis factor-alpha and insulin resistance in obese men with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2001;52(2):119–123. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(00)00247-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moraes C, Labuz JM, Leung BM, Inoue M, Chun TH, Takayama S. On being the right size: scaling effects in designing a human-on-a-chip. Integr. Biol. 2013;5(9):1149–1161. doi: 10.1039/c3ib40040a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Morigny P, Houssier M, Mouisel E, Langin D. Adipocyte lipolysis and insulin resistance. Biochimie. 2016;125:259–266. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2015.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ng Y, Ramm G, James DE. Dissecting the mechanism of insulin resistance using a novel heterodimerization strategy to activate akt. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285(8):5232–5239. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.060632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nguyen MT, Satoh H, Favelyukis S, Babendure JL, Imamura T, Sbodio JI, Zalevsky J, Dahiyat BI, Chi NW, Olefsky JM. Jnk and tumor necrosis factor-alpha mediate free fatty acid-induced insulin resistance in 3t3-l1 adipocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280(42):35361–35371. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504611200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Park SY, Cho YR, Kim HJ, Higashimori T, Danton C, Lee MK, Dey A, Rothermel B, Kim YB, Kalinowski A, Russell KS, Kim JK. Unraveling the temporal pattern of diet-induced insulin resistance in individual organs and cardiac dysfunction in c57bl/6 mice. Diabetes. 2005;54(12):3530–3540. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.12.3530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Prodanov L, Jindal R, Bale SS, Hegde M, McCarty WJ, Golberg I, Bhushan A, Yarmush ML, Usta OB. Long-term maintenance of a microfluidic 3d human liver sinusoid. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2016;113(1):241–246. doi: 10.1002/bit.25700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Qatanani M, Lazar MA. Mechanisms of obesity-associated insulin resistance: many choices on the menu. Genes Dev. 2007;21(12):1443–1455. doi: 10.1101/gad.1550907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rothbauer M, Zirath H, Ertl P. Recent advances in microfluidic technologies for cell-to-cell interaction studies. Lab. Chip. 2018;18(2):249–270. doi: 10.1039/c7lc00815e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rotter V, Nagaev I, Smith U. Interleukin-6 (il-6) induces insulin resistance in 3t3-l1 adipocytes and is, like il-8 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha, overexpressed in human fat cells from insulin-resistant subjects. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278(46):45777–45784. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301977200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ruan H, Hacohen N, Golub TR, Van Parijs L, Lodish HF. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha suppresses adipocyte-specific genes and activates expression of preadipocyte genes in 3t3-l1 adipocytes: nuclear factor-kappab activation by tnf-alpha is obligatory. Diabetes. 2002;51(5):1319–1336. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.5.1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ruban A, Stoenchev K, Ashrafian H, Teare J. Current treatments for obesity. Clin. Med. (Lond.) 2019;19(3):205–212. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.19-3-205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ryden M, Arner P. Tumour necrosis factor-alpha in human adipose tissue – from signalling mechanisms to clinical implications. J. Intern. Med. 2007;262(4):431–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2007.01854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sabio G, Das M, Mora A, Zhang Z, Jun JY, Ko HJ, Barrett T, Kim JK, Davis RJ. A stress signaling pathway in adipose tissue regulates hepatic insulin resistance. Science. 2008;322(5907):1539–1543. doi: 10.1126/science.1160794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sakoda H, Ogihara T, Anai M, Funaki M, Inukai K, Katagiri H, Fukushima Y, Onishi Y, Ono H, Fujishiro M, Kikuchi M, Oka Y, Asano T. Dexamethasone-induced insulin resistance in 3t3-l1 adipocytes is due to inhibition of glucose transport rather than insulin signal transduction. Diabetes. 2000;49(10):1700–1708. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.10.1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shen JF, Sugawara A, Yamashita J, Ogura H, Sato S. Dedifferentiated fat cells: an alternative source of adult multipotent cells from the adipose tissues. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2011;3(3):117–124. doi: 10.4248/IJOS11044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shibasaki M, Takahashi K, Itou T, Bujo H, Saito Y. A ppar agonist improves tnf-alpha-induced insulin resistance of adipose tissue in mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003;309(2):419–424. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shulman GI. Cellular mechanisms of insulin resistance. J. Clin. Investig. 2000;106(2):171–176. doi: 10.1172/JCI10583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sugihara H, Yonemitsu N, Miyabara S, Toda S. Proliferation of unilocular fat cells in the primary culture. J. Lipid Res. 1987;28(9):1038–1045. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sugihara H, Yonemitsu N, Miyabara S, Yun K. Primary cultures of unilocular fat cells: characteristics of growth in vitro and changes in differentiation properties. Differentiation. 1986;31(1):42–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.1986.tb00381.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tan SX, Fisher-Wellman KH, Fazakerley DJ, Ng Y, Pant H, Li J, Meoli CC, Coster AC, Stockli J, James DE. Selective insulin resistance in adipocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290(18):11337–11348. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.623686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tanataweethum N, Zelaya A, Yang F, Cohen RN, Brey EM, Bhushan A. Establishment and characterization of a primary murine adipose tissue-chip. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2018;115(8):1979–1987. doi: 10.1002/bit.26711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Thomson MJ, Williams MG, Frost SC. Development of insulin resistance in 3t3-l1 adipocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272(12):7759–7764. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.12.7759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tremmel M, Gerdtham UG, Nilsson PM, Saha S. Economic burden of obesity: a systematic literature review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2017;14(4):435. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14040435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wei S, Bergen WG, Hausman GJ, Zan L, Dodson MV. Cell culture purity issues and dfat cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013;433(3):273–275. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wellen KE, Hotamisligil GS. Obesity-induced inflammatory changes in adipose tissue. J. Clin. Investig. 2003;112(12):1785–1788. doi: 10.1172/JCI20514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Whiteman EL, Cho H, Birnbaum MJ. Role of akt/protein kinase b in metabolism. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2002;13(10):444–451. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(02)00662-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zambon A, Zoso A, Gagliano O, Magrofuoco E, Fadini GP, Avogaro A, Foletto M, Quake S, Elvassore N. High temporal resolution detection of patient-specific glucose uptake from human ex vivo adipose tissue on-chip. Anal. Chem. 2015;87(13):6535–6543. doi: 10.1021/ac504730r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zhao Y, Kankala RK, Wang SB, Chen AZ. Multi-organs-on-chips: towards long-term biomedical investigations. Molecules. 2019;24(4):675. doi: 10.3390/molecules24040675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.