Abstract

Irene Agyepong and colleagues share experiences and ideas to strengthen capacity for health research co-production in low and middle income countries

Ghana’s universal health insurance scheme provides a good example of co-production of research. In 1991, Ghana’s director of medical services asked researchers to determine whether health insurance could be an equitable and feasible health financing option in a low income country, such as Ghana, with a large informal sector. The research team, which had expertise in public health, health policy and systems, and medical anthropology, worked with frontline health workers and managers, local government, community members, and leaders to explore the acceptability, design, and feasibility of a district-wide health insurance scheme. The resulting design embedded principles of equity and social solidarity and ensured financial sustainability in a resource constrained context, and evidence from this research informed the Ghana national health insurance scheme (NHIS), which was launched in 2001.1 2 3 4

This example shows the important role that co-production of health research can have in generating relevant evidence and innovative, context specific solutions for public health and clinical care challenges. Despite this potential and the growing literature, co-production remains relatively limited in low and middle income countries (LMICs).5 6 7 8 9 Globally, researchers in high income countries lead most current work. For example, a rapid PubMed search on 19 October 2020 yielded 2009 articles for the terms “co-production” and “research.” Adding the terms “developing country/countries” or “low- and middle-income country/countries” reduced the results to fewer than 30. This neglect in LMICs is partly because of capacity and funding challenges. In this article we share experiences and ideas for capacity strengthening and resource allocation for health research co-production in LMICs.

Capacity strengthening for health research co-production

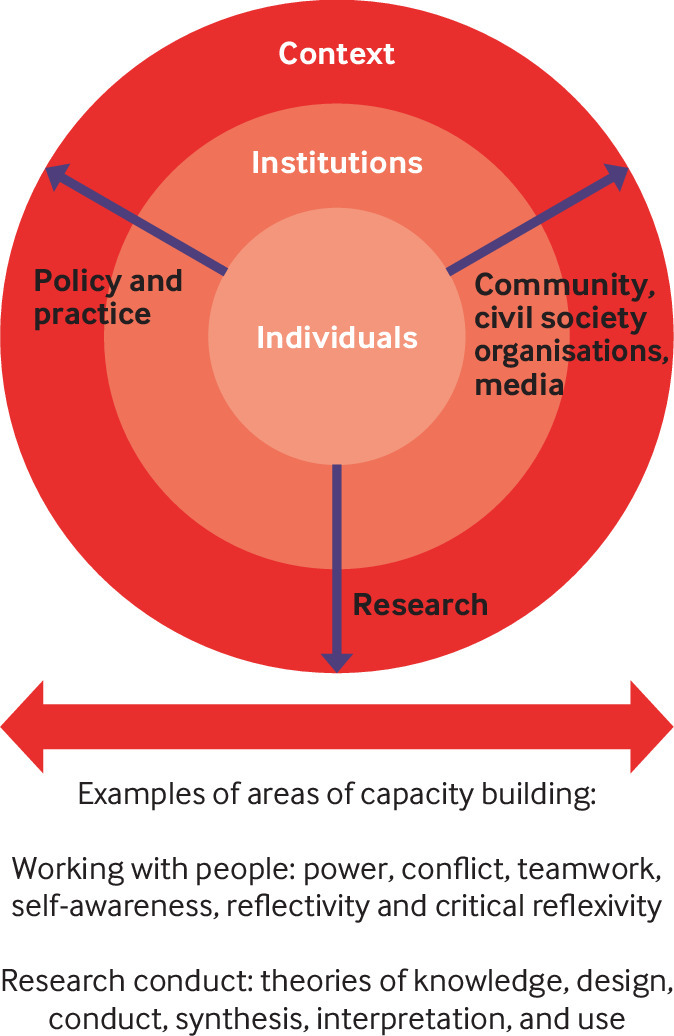

Capacity strengthening for the co-production of health research can enable bottom-up and contextually appropriate policy and programme design, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation, as well as strengthen local ownership and research uptake.10 Drawing on the literature and our experiences, we propose a framework to structure, design, and implement co-production capacity strengthening at inter-related individual, institutional, and contextual levels (fig 1).11 12

Fig 1.

A framework to guide co-production capacity strengthening

The use of concentric circles in the figure shows that individual capacity is embedded within institutions, which are in turn set within the broader context. Individual capacity refers to the skills to design and co-produce research and to engage in research uptake for decision making and implementation. Institutional capacity refers to the capabilities, knowledge, culture, relationships, and resources that support individuals to perform in co-production efforts. Examples include infrastructure, leadership, motivation, and reward systems. Contextual capacity is the wider international, national, and sub-national social, economic, historical, political, structural, and situational factors that support co-production efforts,13 14 15 such as whether a country provides core funding to institutions and departments for co-production research. The arrows emphasise that capacity strengthening needs to occur across all three levels and engage the range of individual stakeholders involved in the health research co-production process. For simplicity, we have clustered these stakeholders into “research”—for example, professional researchers and academics; “policy and practice”—for example, national level policy makers, frontline health workers, and managers; and “community, civil society organisations, and the media.”

As members of the Consortium for Mothers, Children, Adolescents and Health Policy and Systems Strengthening, we have been using this framework since 2018 in strengthening country level co-production research capacity to support improvements in women, newborn, children, and adolescent wellbeing in six countries in west Africa (Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Niger, Senegal, and Sierra Leone). Within the context of these efforts, we critically reflect on two cross cutting challenges to co-production capacity building: how to effectively work with diverse knowledge and expertise; and, in doing so, how to handle power dynamics.16 17

Design of the co-production capacity building effort

In each country, a mix of national and sub-national level health professionals, academic researchers, civil society organisations, and media practitioners make up a small team to design and co-produce research, interventions, and advocacy on an identified health priority: examples include adolescent sexual and reproductive health in Burkina Faso and Sierra Leone, responsive maternity care in Senegal and Côte d’Ivoire, and referral care in Ghana. Up to six team members are selected through dialogue with the leadership of each individual’s organisation, which strengthens organisational engagement and support for the work. The six countries are part of the 15 member Economic Community of West African States, for which the West African Health Organization is the subregional health body. The West African Health Organization provides strong contextual level support and broader institutional engagement for the co-production capacity building efforts, including through its close links with all ministries of health in the sub-region.

Peer-to-peer as well as peer-to-facilitator engagement and learning within and across teams are encouraged using a series of interactive workshops rather than a single engagement. Workshops focus on different topics, including how to work in multidisciplinary teams within complex adaptive systems; leading and managing change; and understanding and effectively using power, communication, and policy processes.18 Email, online forums, and a WhatsApp group enable networking and cross country communication between teams and facilitators. Two years into the implementation of these efforts there are important lessons for co-production capacity building and resource mobilisation in LMICs.

Working with a diversity of knowledge and expertise

Dependent on the specific health problem to be tackled, different stakeholders (fig 1) can bring diverse knowledge and expertise to the co-production of health research. This helps to ensure that research design, data collection, interpretation, and use are appropriate to context and the phenomenon of “travelling models,” where ideas and interventions are inappropriately transferred from one context to another to little effect, are avoided.19 There are, however, challenges to working with diverse knowledge and expertise and to strengthening the capacity of teams instead of individuals. Team members have busy work schedules and require a lot of encouragement and support to engage with all activities beyond their specialised area, such as research, journalism, community advocacy, or service delivery. Differing levels of confidence and skill sets within the team can also lead some members to doubt their ability, while others may lack the motivation to acquire and apply new skills. The capacity building process can help team members to recognise the value of the different skills, experience, and knowledge needed to design and implement health research, without the pressure of having to be the “expert” in everything.

Dealing with power dynamics

Unequal power relationships can weaken co-production efforts and have negative consequences, such as disregard for diverse forms of knowledge.20 Within the process of co-production, attention must therefore be paid to visible as well as invisible power.21 For example, some team members who perceive themselves as lower in the social or professional hierarchy may hesitate to contribute an alternative idea or approach to research design when another member thought to have more visible power—that is, more authority owing to their leadership position or being an “expert” on the topic—is present. Invisible power, such as internalised social roles and stereotypes, can also shape how people think about the issues and affect people’s confidence to engage in the process.

The use of resources, such as humour, stories, cartoons, and pictures, together with the sharing of personal experiences, is critical for engaging team members in open discussions about power dynamics in a relaxed and non-threatening manner. A skilled facilitator helps to encourage every participant to engage so that no one person dominates the discussion. These approaches can help tackle some of the negative perspectives and prejudices that prevent team members from appreciating the importance of diverse “knowledge” and “expertise.” Presenting and discussing different philosophical theories about what can be known (ontology) and how to know (epistemology) in relation to research questions also helps team members to appreciate the contribution of diverse perspectives in the co-production of health research design and implementation. As shown in the figure, self-awareness, critical reflexivity, teamwork, conflict resolution, and collaborative problem solving are essential skills for all stakeholders to engage effectively in co-production processes.

Resourcing capacity building for co-production

In our experience, capacity building takes time and reinforcement through practice. Teams progress at different rates and need to be supported at the pace that works for them. Coproduction capacity building also needs sustained medium to long term investment to demonstrate value to policy and programme decision making and implementation for improved health outcomes. For example, the co-production research effort for the district health insurance scheme in Ghana occurred in the context of a long term effort to build research capacity in the Ghana Health Service to generate evidence in support of policy and programme decision making. Initiated in 1989 with senior Ministry of Health support, institutional capacity strengthening included the development of what is now the research and development directorate with establishment of researcher positions within the health service.22 Capacity strengthening entailed training new academic researchers in qualitative and quantitative disciplines. At the same time, health workers worked in partnerships with academic researchers and gained a better understanding of how to design and interpret research for use in policy and practice. This investment has influenced many health policies and programmes in Ghana beyond the NHIS, such as the community based health planning and services programme.23 24

Co-production capacity building can be resource intensive, requiring sustained stakeholder interest as well as facilitator expertise. Ensuring sufficient financing and skilled human resources for research capacity building continues to be a challenge in LMICs faced with chronic resource constraints in health service delivery.25 26 Advocacy for core funding to co-production approaches is critical for challenging this status quo in many LMICs and for showing the value of research co-production, which includes the development of innovative solutions to complex health challenges and the achievement of health improvement goals.

Given the domestic funding challenges to strengthening health research capacity in many LMICs, external donors remain an important source of funding. However, international research funding priorities do not necessarily prioritise co-production capacity building or co-production research support. In addition, stakeholders in research co-production may not have international competitive grant writing skills or even know where and how to look for such opportunities. For example, in Ghana the health financing research agenda was set in 1991. After two years of formative research on the feasibility of an experimental district health insurance scheme, the co-production process to design, implement, monitor, and evaluate such a scheme took place between 1995 and early 2000. The gap of almost a decade between agenda setting and generating the evidence to inform the Ghana NHIS was partly due to the challenges of mobilising resources for a co-production approach that was not widely understood. The locally driven co-production research agenda did not fit the priorities of many open funding calls, while research funding made available by the Ghana Health Service was for the design of a classic social insurance scheme, using consultants and “experts.” Furthermore, because the Ghana Health Service research capacity building efforts were in their first decade, researchers were still at the start of their careers and did not have the expertise to compete with more experienced grant writers.

In conclusion, health research co-production has the potential to make a difference to health outcomes in LMICs. Capacity strengthening and sustainable resourcing for medium to long term co-production efforts are needed to realise this potential. Co-production capacity building needs to target multiple stakeholders, including patients and communities, practitioners, policy makers, and academics, to develop their skills and confidence to contribute as equal participants in the process.

Key messages.

Strengthening health research co-production capacity is a relatively neglected but important area of work in low and middle income countries

Adequate human and financial resources are needed to strengthen capacity for the co-production of health research

Strengthening co-production capacity requires creating space for and allowing a diversity of knowledge and expertise and paying attention to power dynamics between team members

Capacity building also requires medium to long term rather than short term efforts to establish and institutionalise a culture of health research co-production

Acknowledgments

The Consortium for Mothers, Children, Adolescents and Health Policy and Systems Strengthening and Women, Newborn, Children, and Adolescent Wellbeing projects are funded by International Development Research Centre grants. We thank Rachael Hinton at The BMJ for her editorial review of the various drafts of this manuscript.

Contributors and sources:IAA is a public health physician and a part time consultant with the Dodowa Health Research Centre of the research and development division of the Ghana Health Service. She is a foundation fellow of the Public Health Faculty of the Division of Physicians of the Ghana College of Physicians and Surgeons; and trainer, supervisor, coach, and mentor for its public health membership and fellowship training programmes. IS is an epidemiologist and the principal officer in charge of research and grants in the West Africa Health Organization based in Bobo Dioulasso, Burkina Faso. VO is executive director of the Alliance for Reproductive Health Rights, a civil society organisation based in Ghana. CB is executive director of Women Media and Change, a civil society organisation based in Ghana. M-G I is responsible for International Development Research Centre health programmes in west Africa. SG was formerly the International Development Research Centre programme officer responsible for health programmes in west Africa and is now completing her doctorate in policy research and practice at the University of Bath. IAA led the writing of the paper. All authors contributed to the conceptualisation of the paper and review of the drafts. Our sources of data are from the literature and our experiences.

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and have no relevant interests to declare.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

This article is part of a series produced in conjunction with WHO and the Alliance for Health Policy Systems and Research with funding from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. The BMJ peer reviewed, edited, and made the decision to publish.

References

- 1.Dangme West Health Insurance Scheme (Dangme Hewaminami Kpee). Annual report of the1st insurance year (1st October 2000—30th September 2001). 2002. http://www.panafricandrph.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/DWHIS-1st-Year-Insurance-Annual-Report.pdf

- 2.Dangme West Health Insurance Scheme (Dangme Hewaminami Kpee) Annual report of the 2nd insurance year (2001/2002). 2003. http://www.panafricandrph.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/DWHIS-2nd-Year-Insurance-Annual-Report.pdf

- 3. Agyepong IA, Adjei S. Public social policy development and implementation: a case study of the Ghana National Health Insurance scheme. Health Policy Plan 2008;23:150-60. 10.1093/heapol/czn002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Agyepong IA, Orem JN, Hercot D. Viewpoint: when the “non-workable ideological best” becomes the enemy of the “imperfect but workable good”. Trop Med Int Health 2011;16:105-9. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02639.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tembo D, Morrow E, Worswick L, Lennard D. Is co-production just a pipe dream for applied health research commissioning? An exploratory literature review. Frontiers in Sociology 2019;4:50 10.3389/fsoc.2019.00050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farr M, Davies R, Davies P, Bagnall D, Brangan E, Andrews H. A map of resources for co-producing research in health and social care. National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) ARC West and People in Health West of England; University of Bristol and University of West of England. Version 1.2, May 2020. https://arc-w.nihr.ac.uk/Wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Map-of-resources-Web-version-v1.2.pdf

- 7.Davies R, Andrews H, Farr M, Davies P, Brangan E, Bagnall D. Reflective questions to support co-produced research Version 1.2. National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) ARC West and People in Health West of England; University of Bristol and University of West of England, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Oliver K, Kothari A, Mays N. The dark side of coproduction: do the costs outweigh the benefits for health research? Health Res Policy Syst 2019;17:33. 10.1186/s12961-019-0432-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Williams O, Sarre S, Papoulias SC, et al. Lost in the shadows: reflections on the dark side of co-production. Health Res Policy Syst 2020;18:43. 10.1186/s12961-020-00558-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vanyoro KP, Hawkins K, Greenall M, Parry H, Keeru L. Local ownership of health policy and systems research in low-income and middle-income countries: a missing element in the uptake debate. BMJ Glob Health 2019;4:e001523. 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Potter C, Brough R. Systemic capacity building: a hierarchy of needs. Health Policy Plan 2004;19:336-45. 10.1093/heapol/czh038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. LaFond AK, Brown L, Macintyre K. Mapping capacity in the health sector: a conceptual framework. Int J Health Plan Manage 2002;17:3-22. 10.1002/hpm.649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Potter C, Brough R. Systemic capacity building: a hierarchy of needs. Health Policy Plan 2004;19:336-45. 10.1093/heapol/czh038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. United Nations Development Programme Capacity development practice Note. UNDP, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Brown L, Lafond A, Macintyre K. Measuring capacity building. Measure Evaluation, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wyborn C, Datta A, Montana J, et al . Co-producing sustainability: reordering the governance of science, policy, and practice. Annu Rev Environ Resour 2019;44:319-46 10.1146/annurev-environ-101718-033103 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pohl C, Rist R, Zimmermann A, et al. Researchers roles in knowledge co-production: experience from sustainability research in Kenya, Switzerland, Boliva and Nepal. Sci Public Policy 2010;37:267-81 10.3152/030234210X496628 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Consortium for Mothers, Children, Adolesecents,and Health Policy abd Systems Strengthening Secretariat. 2020 new year school report. 2020. http://www.comcahpss.org/2020-new-year-school-report-english /

- 19. Olivier de Sardan JP, Diarra A, Moha M. Travelling models and the challenge of pragmatic contexts and practical norms: the case of maternal health. Health Res Policy Syst 2017;15(suppl 1):60. 10.1186/s12961-017-0213-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mintzberg H. Power in and around organizations. Prentice-Hall, 1983.

- 21. VeneKlasen L, Miller V. A new weave of people. Power and politics: the action guide for advocacy and citizen participation. World Neighbors, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ghana Health Service. Research and Development Division. About us. 2014. https://www.ghanahealthservice.org/division-cat.php?ghsdid=11&ghscid=61

- 23. Binka FN, Nazzar A, Phillips JF. The Navrongo community health and family planning project. Stud Fam Plan 1995;26:121-39. 10.2307/2137832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nyonator FK, Awoonor-Williams JK, Phillips JF, Jones TC, Miller RA. The Ghana community-based health planning and services initiative for scaling up service delivery innovation. Health Policy Plan 2005;20:25-34. 10.1093/heapol/czi003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gonzalez Block MA, Mills A. Assessing capacity for health policy and systems research in low and middle income countries. Health Res Policy Syst 2003;1:1. 10.1186/1478-4505-1-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Defor S, Kwamie A, Agyepong IA. Understanding the state of health policy and systems research in west Africa and capacity strengthening needs: scoping of peer-reviewed publications trends and patterns 1990-2015. Health Res Policy Syst 2017;15(suppl 1):55. 10.1186/s12961-017-0215-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]