Abstract

Introduction

Patients are the most common source of gender-based harassment of resident physicians, yet residents receive little training on how to handle it. Few resources exist for residents wishing to address patient-initiated verbal sexual harassment themselves.

Methods

We developed, taught, and evaluated a 50-minute workshop to prepare residents and faculty to respond to patient-initiated verbal sexual harassment toward themselves and others. The workshop used an interactive lecture and role-play scenarios to teach a tool kit of communication strategies for responding to harassment. Participants completed retrospective pre-post surveys on their ability to meet the learning objectives and their preparedness to respond.

Results

Ninety-one participants (57 trainees, 34 faculty) completed surveys at one of five workshop sessions across multiple departments. Before the workshop, two-thirds (67%) had experienced patient-initiated sexual harassment, and only 28 out of 59 (48%) had ever addressed it. Seventy-five percent of participants had never received training on responding to patient-initiated sexual harassment. After the workshop, participants reported significant improvement in their preparedness to recognize and respond to all forms of patient-initiated verbal sexual harassment (p < .01), with the greatest improvements noted in responding to mild forms of verbal sexual harassment, such as comments on appearance or attractiveness or inappropriate jokes (p < .01).

Discussion

This workshop fills a void by preparing residents and faculty to respond to verbal sexual harassment from patients that is not directly observed. Role-play and rehearsal of an individualized response script significantly improved participants' preparedness to respond to harassment toward themselves and others.

Keywords: Sexual Harassment, Harassment, Gender, Bias, Communication Skills, Gender Issues in Medicine, Professionalism, Diversity, Inclusion, Health Equity

Educational Objectives

By the end of this activity, learners will be able to:

-

1.

Discuss the prevalence and impact of patient-initiated sexual harassment on trainees and the learning environment.

-

2.

Describe the role of supervisors and colleagues in monitoring and responding to sexual harassment by patients and identify potential barriers to this process.

-

3.

Recognize various forms of patient-initiated sexual harassment.

-

4.

Apply at least three practical strategies for responding to sexual harassment from patients.

Introduction

Patients are the most common sources of gender-based discrimination toward medical trainees,1–3 yet most physicians do not receive training on how to handle harassment initiated by patients.4 Institutional training often omits guidance on dealing with sexual harassment from patients,4 and formal reporting procedures do not account for more common forms of discrimination, such as inappropriate sexual remarks and gender-based microaggressions.5 To our knowledge, there is no published resource for resident physicians on how to address patient-initiated sexual harassment themselves.

Residents receive the bulk of their communication skills education in early medical school.6 Although they are trained to obtain informed consent and deliver bad news,7 residents who experience sexual harassment from a patient are often unprepared to respond.8 They may find themselves in fight-or-flight mode9 and default to ignoring the harassment behavior or nervously laughing it off, despite a desire to address it. We encourage all trainees to report instances of severe or pervasive sexual harassment to their appropriate program and institutional resources. However, for the majority of situations that do not meet an official reporting threshold,1 we offer this workshop on communication tools for residents and faculty who wish to respond to patient-initiated verbal sexual harassment.

Previous authors in MedEdPORTAL have described curricula for faculty on responding to patient mistreatment of medical trainees; however, their work has focused on directly observed mistreatment. To our knowledge, there are only two modules5,10 in MedEdPORTAL on addressing patient mistreatment of medical trainees. Like the ERASE curriculum of Wilkins and colleagues,10,11 our module uses an interactive workshop to teach communication tools for responding to discriminatory comments made by patients. However, where the ERASE model trains faculty and senior residents to address directly observed patient mistreatment toward junior medical trainees and the model by Sandoval and colleagues5 encourages junior medical students to enlist supervising faculty in responding to microaggressions, our workshop empowers residents and faculty to respond to inappropriate patient comments themselves. Our module recognizes that many instances of inappropriate patient behavior occur in one-on-one situations, such as during after-hours clinical care, and are unlikely to be witnessed by supervisors. Unlike the ERASE model10 and the module on microaggressions by Sandoval and colleagues,5 this workshop limits its focus to gender-based harassment, though its communication tools are applicable to other forms of identity-based discrimination. We emphasize gender-based discrimination and harassment because they are the most common type experienced by resident physicians8 and the workshop was developed to address resident needs at our institution.

The resident-authored, interactive workshop described here uses role-play and script rehearsal to prepare trainees to respond to sexual harassment from patients. It draws on recommendations from previous authors to use strategies like “I” statements, address the behavior rather than the harasser, and set clear boundaries.9,12–14 Peer role-play scenarios were chosen because they have been shown to increase medical trainees' self-confidence in their communication skills.15 Use of a short, standardized script in communicating with patients has also been shown to improve patient understanding of trainees' role in the clinical setting.16 Given the power that faculty and peers have to change or reinforce clinical culture norms,9 the workshop also emphasizes the importance of bystander intervention.9–11 After participating in the workshop, all physicians will have developed and rehearsed a script for responding in their own words to verbal harassment toward themselves and a trainee.

Methods

We designed an interactive workshop aimed at residents and faculty to teach strategies for responding to verbal sexual harassment from patients. The workshop strategies were based on a tool kit17 of communication techniques for both physicians experiencing verbal sexual harassment and those observing harassment toward another person and wishing to intervene.

The development of this workshop emerged from multiple department-wide conversations surrounding residents' lack of preparedness to address verbal sexual harassment from patients. We reviewed existing institution-wide sexual harassment training and found sparse education on dealing with harassment initiated by patients. The harassment tool kit and workshop content were targeted to resident physicians and supervising faculty, though their strategies could certainly be applicable to medical students. The tool kit strategies drew on work by Goodman,12 Wheeler and colleagues,9 and Goldenberg and colleagues11 on strategies for responding to identity-based mistreatment. Faculty experts in medical education guided the development of workshop goals, specific learning objectives, and methods for program assessment and evaluation based on the Kern model.18

The ideal workshop facilitator would be a clinician with an interest in graduate medical education and gender equity in medicine. All our sessions were led by a female resident who had personally experienced verbal sexual harassment by patients. Given the target audience of resident physicians, the preferred facilitator would have at least a resident's level of clinical experience. Personal experience with patient-initiated harassment was not a prerequisite to lead the workshop, but limited facilitator sharing of personal experiences could help encourage participant discussion.

The content of these sessions is contained in Appendices A and B. We began each session with a recitation of eight real patient comments directed toward female physicians at our institution that had been submitted anonymously to us prior to the workshop (see Appendix B, slide 1). Volunteer trainee participants called out the patient comments in sequence, or the facilitator recited them. The comments increased in severity, from “Are you sure you're a doctor?” to “What if I grabbed your breasts?” This was followed by 2 minutes of welcome and introduction, during which the facilitator reminded participants that workplace sexual harassment affects all physicians and encouraged open discussion.

The workshop facilitator then led a brief interactive lecture guided by PowerPoint slides (Appendix B) that focused on four key points: (1) Sexual harassment is highly prevalent among medical trainees, and most is by patients; (2) verbal sexual harassment by patients is underreported by trainees; (3) sexual harassment negatively impacts mental health, work performance, and patient care; and (4) physicians who are sexually harassed feel ill prepared to address it in real time. The facilitator then asked participants to share reasons why physicians do not speak up when sexual harassment by patients occurs. This portion of the workshop lasted 10 minutes.

The facilitator next asked participant volunteers to read aloud two brief clinical conversations between a physician and patient—one featuring gender-based microaggressions and the second an instance of verbal sexual harassment. She asked participants to raise their hands if they had experienced or observed similar scenarios. The facilitator then gave participants 2 minutes to share their initial reactions to the example of verbal sexual harassment. She stated that common reactions included disbelief that the patient had made the harassing comment and wonder at whether the comments were worth addressing.12,13 The participating physicians were encouraged to consider whether responding would affect their physical safety or relationship with the patient, whether they would regret not calling out the verbal harassment, and whether ignoring the behavior would convey that they accepted it.13

Next, the facilitator formally introduced the tool kit of communication strategies for addressing verbal sexual harassment from patients (Appendix B, slides 23–32). Volunteer participants helped distribute white-coat pocket-sized tool kit cards (7.00 inches by 3.75 inches) to all participants (Appendix C).17 The tool kit strategies were targeted to two audiences: first, physicians experiencing harassment by patients; second, those observing sexual harassment toward a trainee or peer. The facilitator read aloud a sample response statement using multiple tool kit strategies: “I'm sure you didn't mean to be hurtful, but I feel uncomfortable when you comment on my appearance. I want to give you the best care that I can, so let's keep our conversation professional.”

We devoted the subsequent 20 minutes of the workshop to clinical role-play scenarios and response rehearsal. The facilitator asked participants to read aloud three physician-patient scenarios depicting verbal sexual harassment. Two scenarios featured patient-initiated harassment experienced by the physicians themselves, and the third introduced direct observation of harassment of a medical student. The facilitator then gave all participants 3 minutes to rehearse their responses to the patient comments in pairs using the tool kit. Participants shared responses that they felt worked well and those that seemed ineffective. Workshop participants rehearsed their own response scripts at least three times. The facilitator emphasized that there was no single correct way to respond to each scenario.

The facilitator then led a 5-minute wrap-up in which she summarized take-home points and shared helpful resources, including the online version of the tool kit card.17 Following the workshop, she encouraged participants to promote open dialogue within their programs, encourage bystander intervention, and empower trainees and faculty to call out verbal sexual harassment with specific tools.

The lead author-facilitator delivered the workshop in five sessions (approximately 50 minutes in duration) at a single academic institution in mid-late 2019 and early 2020. The participants were as follows:

-

•

Sessions 1 and 2: Department of Ophthalmology faculty, residents, and integrated interns during education rounds.

-

•

Session 3: faculty representing each residency program at our institution during a Graduate Medical Education Program Director Development Seminar.

-

•

Session 4: Department of Surgery residents during education rounds.

-

•

Session 5: Department of Family Medicine residents and their faculty leaders during a resident retreat.

No participant preparation was required prior to the sessions.

We modified the workshop content very little between the five sessions. The flow of the sessions was consistent among all groups. Each group received the same workshop introduction with real patient comments, interactive lecture material, and discussion of tool kit strategies. The only content that was subtly edited was language between surgical and nonsurgical subspecialties. For example, in the statement “I'll be assisting Dr. Y with your procedure today,” “procedure” was changed to “surgery” for the general surgery session.

To evaluate the workshop, we surveyed participants using a retrospective questionnaire on their ability to complete the stated learning objectives and their preparedness to respond to sexual harassment immediately before and after the workshop (Appendix D). The retrospective pretest-posttest evaluation19 was completed only once, at the end of the workshop, to minimize the impact of participants incorrectly assessing their abilities due to not knowing what they did not know before the workshop and to maximize time for workshop content during a limited time window without the ability to run late into clinical time. Participants rated their preparedness on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = totally unprepared, 5 = totally prepared). They also characterized their experiences with patient-initiated verbal sexual harassment prior to the workshop and indicated whether they had previously received training on response techniques. We analyzed the survey responses from all workshop sessions in the aggregate. Responses to each matched question of the retrospective pre- and postsurveys were analyzed using a paired t test. We also invited participants to write comments about their workshop experience.

We were granted an exemption by the University of Iowa Institutional Review Board to collect and analyze survey data.

Results

A total of 91 physicians participated in the workshop and completed the evaluations (57 trainees, 34 faculty; 45 females, 44 males, two no response). (For further demographics, see Table 1.) Prior to workshop participation, two-thirds of participants (59 out of 91, 67%) had experienced patient-initiated harassment, and of those, less than half (28 out of the 59, 48%) had ever directly responded to it. Most participants (46 out of 91, 52%) reporting having observed harassment toward another person, but fewer (35 out of the 46, 76%) said they had ever intervened on another person's behalf. Seventy-five percent of physicians (69 out of 91) had never received training on responding to sexual harassment initiated by patients.

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of Study Sample (N = 91).

Workshop participants demonstrated significant improvements in their ability to complete all stated workshop learning objectives (Table 2). Participants reported significantly improved preparedness to respond directly to patient-initiated sexual harassment toward themselves (mean difference = −1.2; 95% CI, −1.4 to −1.0; p < .01) and toward a trainee (mean difference = −1.2; 95% CI, −1.4 to −1.1; p < .01). Participants were also asked to rate their preparedness to respond to varying levels of harassment severity. Among the severity levels,3 the greatest improvements were noted in preparedness to respond to milder forms of verbal sexual harassment, such as comments about appearance, attractiveness, or inappropriate jokes (mean difference = −1.1; 95% CI, −1.2 to −0.9; p < .01) and comments about age, gender, and marital status (mean difference −1.0; 95% CI, −1.2 to −0.9; p < .01).

Table 2. Participants' Self-Rated Abilities Pre- and Postworkshop Participation (N = 91).

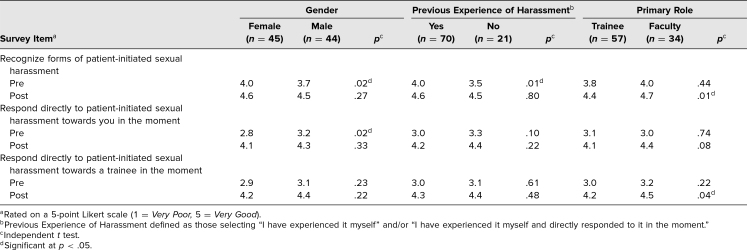

We performed subgroup analyses based on gender, previous experiences with patient-initiated sexual harassment, and trainee versus faculty role (Table 3). Female participants rated themselves as being significantly more prepared (4.0) than male participants (3.7) to recognize sexual harassment before the workshop (95% CI, −0.7 to −0.1; p = .02). This difference was no longer significant after workshop participation (men = 4.5 vs. women = 4.6; 95% CI, −0.3 to 0.1; p = .27). Before workshop participation, men rated themselves as significantly more prepared to respond to patient-initiated harassment toward themselves than women (3.2 vs. 2.8; 95% CI, 0.1 to 0.7; p = .02). Men continued to rate themselves as more prepared to respond after workshop participation; however, this difference was no longer significant (men = 4.3 vs. women = 4.1; 95% CI, −0.2 to 0.4; p = .33).

Table 3. Comparison of Self-Rated Abilities Pre- and Postworkshop Participation by Gender, Previous Experience of Harassment, and Primary Role.

Participants who had experienced harassment rated themselves more prepared to recognize sexual harassment before the workshop (4.0) than those who had not (3.5; 95% CI, −0.8 to −0.1; p = .01). This difference in perceived preparedness was nearly eliminated following workshop participation (4.6 vs. 4.5; 95% CI, −0.3 to 0.2; p = .80). Before the workshop, trainees and faculty did not significantly differ in their self-rated ability to recognize (p = .44) or respond to patient-initiated harassment toward themselves (p = .74) or toward a trainee (p = .22). Following workshop participation, faculty were more prepared than trainees to recognize sexual harassment (4.7 vs. 4.4; 95% CI, −0.5 to −0.1; p = .01) and respond to patient-initiated harassment towards a trainee (4.5 vs. 4.2; 95% CI, −0.5 to 0.0; p = .04).

We also analyzed the effect of gender on preparedness to respond to forms of verbal sexual harassment by severity. No gender differences were noted in preparedness to respond to milder forms of sexual harassment before or after the workshop (Table 4). Male participants felt significantly more prepared than female participants to respond to comments about a specific body part, sexual jokes, or gestures both before (3.3 vs. 2.9; 95% CI, 0.1 to 0.8; p = .01) and after (4.3 vs. 3.9; 95% CI, 0.2 to 0.7; p < .01) the workshop. Male participants also felt significantly more prepared to respond to threats of physical assault or harassment (4.2 vs. 3.8; 95% CI, 0.1 to 0.7; p = .01) and sexual comments about a body part or asking to touch (4.4 vs. 3.9; 95% CI, 0.2 to 0.8; p < .01) after workshop participation only.

Table 4. Preparedness to Respond to Forms of Verbal Sexual Harassment by Gender.

Participant comments on the workshops were overwhelmingly positive. Many participants expressed an interest in expanding the workshop to include other types of identity-based harassment, such as discrimination based on race, ethnicity, religion, or sexual orientation. Such comments included the following:

-

•General comments:

-

○“Awesome workshop; much needed. I do feel more prepared, but already realize I need more practice.”

-

○“Very helpful discussion. Talking it out with other person gives you an indication of the difficulty of formulating the right words.”

-

○“I had no idea how prevalent this was.”

-

○“Let's introduce this to the nursing staff/leadership as well.”

-

○“I'm a woman and I'm used to unwanted comments. It's interesting to hear the males being shocked by comments (because many times they don't experience that type of behavior). Innocently, the men don't see it.”

-

○“Much of the cases of harassment do not get conveyed to all faculty and staff. These sessions should be continued to increase communication about this.”

-

○“Exceptional workshop. The is the best/most actionable I have ever been part of.”

-

○

-

•Suggestions for improvement:

-

○“Even more pertinent simulations would be helpful. They prompted good discussion.”

-

○“For more aggressive encounters, what strategies should be used (e.g. threat of violence and how to deescalate)?”

-

○“It should be longer with more exercises.”

-

○“Consider scenarios where the patient isn't the harasser, but their caregiver is. Consider expanding to include racial/ethnic discrimination—I see this as frequently and use similar skills.”

-

○“I recommend diversifying your examples to include comments targeting male trainees and age discrimination as these are equally prevalent and may sometimes be overlooked.”

-

○“Since personal experiences with this can be so impactful, you may need more emphasis to ensure faculty/supervising residents adequately consider when/how to intervene when with a trainee.”

-

○“Incorporate how to recognize when the culture is supporting or encouraging harassment.”

-

○

Discussion

The workshop built on previous authors' work on faculty response to mistreatment of trainees11 by teaching residents communication tools for responding to verbal sexual harassment. We focused on common forms of verbal sexual harassment that may fall below many physicians' threshold for reporting. This 50-minute workshop significantly increased participants' preparedness to respond to patient-initiated verbal sexual harassment toward themselves and others.

During these sessions, we found that opening with actual patient comments from our own institution was particularly effective in encouraging participant buy-in. Some participants expressed surprise and concern that some of the more severe comments had been said by patients at their own institution, whereas others shared similar experiences. The emotional impact of these statements seemed especially significant for male faculty who had never personally experienced gender-based harassment from patients.

Delivering the workshop to different groups highlighted the fact that the communication tools it contains could be applied to other forms of identity-based harassment described by previous authors.11 Several participants of color shared how their experiences with gender-based harassment were often compounded by discrimination based on race or religion. Most participants commented that the same communication strategies could be used for other types of identity-based harassment but that specific training examples would help them feel more prepared to address them.

Participant comments also indicated that discussion between trainees and faculty about discrimination from patients led to more open conversation about gender-based discrimination within the departments themselves. We found that breaking into pairs for the role-play scenarios worked well in group sizes that ranged from 20 to 50 participants. Focusing on discrimination from an external group (i.e., patients) helped avoid triggering defensive responses like “This doesn't apply to my colleagues and me because we are not harassers” among male physician participants. Furthermore, the facilitator for all workshops was a female resident who shared that she had personally experienced harassment from patients and that it had made it difficult for her to care for patients to the best of her ability. Confronted with this personal testimony, most participants acknowledged that the harassment behaviors described were offensive and could negatively affect trainee performance.

This tool kit and workshop can be used with clinicians at various levels of training, including medical students. Due to institutional interest, the workshop has been incorporated into the transition to clinical rotations curriculum for second-year medical students (a group of about 120 students per cohort). Again, the workshop flow and content have been unchanged for this group. One of the strengths of the workshop seemed to be the inclusion of actual institution-specific patient comments. Future facilitators might find collecting these comments before the workshop to be helpful in encouraging buy-in from participants. A similar strategy could be used for adapting the workshop content to other health care professionals, such as nursing staff and patient care technicians.

Overall, subgroup analyses of survey results suggest that male and female participants benefited equally from workshop participation. Differences based on gender in preparedness to respond to harassment toward oneself or a trainee were less significant following workshop participation. When analyzed by harassment severity, men felt more prepared than women to respond to more severe harassment forms, such as threats of physical assault and explicit sexual comments, after workshop participation. We were encouraged that these differences were not significant in addressing milder forms of gender-based harassment more likely to be encountered in daily practice, such as comments about appearance or attractiveness.

The two most common comment themes in our workshop evaluations were that there should be a greater number of role-play scenarios and that these additional scenarios should include other types of identity-based harassment. A workshop duration of 50 minutes was chosen for this module because it allowed us to deliver the workshop during department grand rounds and thus address residents and faculty together. If more time is allowed, inclusion of one to two additional role-play examples with participant discussion may better prepare participants to deal with patient-initiated harassment in clinical practice. Similarly, a greater time allocation for the workshop could permit separate distribution of a pretest before the workshop and a posttest after it, rather than use of a retrospective pretest-posttest survey, to better assess participants' self-rated ability to meet the workshop learning objectives. It could also allow for more robust evaluation of participant knowledge acquisition by asking content-based questions about the workshop.

Our findings are not generalizable to all physicians and trainees. All workshops were facilitated by the same female trainee, and we do not know whether this approach would work with other audiences or institutions. Furthermore, most participants self-identified as White, and their experiences with gender-based harassment likely did not represent those experienced by participants of color. Another limitation of the study is that we do not know whether this intervention improves participants' ability to handle harassment from patients in the clinical setting. While patient confidentiality limits our ability to observe these encounters, future work could assess trainees' clinical experiences with responding to patient-initiated harassment themselves or as a bystander. Specifically, participants could be surveyed 6–12 months after the workshop to see how its tools have translated into their own encounters with patient-initiated harassment. Trainees could give specific examples of how they have intervened in harassment toward themselves or as a bystander. Such a survey could be done anonymously or as a confidential follow-up study.

We are grateful for the work of previous authors on training faculty to respond to patient-initiated mistreatment of medical trainees.10,11 We hope that the additional tools described in this workshop can help demystify the awkwardness many trainees feel surrounding sexual harassment from patients and empower them to respond to these situations with confidence.

Appendices

- Facilitator Guide.docx

- Presentation.pptx

- Harassment Tool Kit.pdf

- Pre- and Postworkshop Survey.docx

All appendices are peer reviewed as integral parts of the Original Publication.

Disclosures

None to report.

Funding/Support

None to report.

Ethical Approval

The University of Iowa Institutional Review Board approved this study.

References

- 1.McKinley SK, Wang LJ, Gartland RM, et al; Massachusetts General Hospital Gender Equity Task Force. “Yes, I'm the doctor”: one department's approach to assessing and addressing gender-based discrimination in the modern medical training era. Acad Med. 2019;94(11):1691–1698. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hu YY, Ellis RJ, Hewitt DB, et al. Discrimination, abuse, harassment, and burnout in surgical residency training. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(18):1741–1752. 10.1056/NEJMsa1903759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scruggs BA, Hock LE, Cabrera MT, et al. A U.S. survey of sexual harassment in ophthalmology training using a novel standardized scale. J Acad Ophthalmol. 2020;12(1):e27–e35. 10.1055/s-0040-1705092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Warsame RM, Hayes SN. Mayo Clinic's 5-step policy for responding to bias incidents. AMA J Ethics. 2019;21(6):521–529. 10.1001/amajethics.2019.521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sandoval RS, Afolabi T, Said J, Dunleavy S, Chatterjee A, Ölveczky D. Building a tool kit for medical and dental students: addressing microaggressions and discrimination on the wards. MedEdPORTAL. 2020;16:10893 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.King A, Hoppe RB “Best practice” for patient-centered communication: a narrative review. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(3):385–393. 10.4300/JGME-D-13-00072.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Association of American Medical Colleges. Recommendations for Clinical Skills Curricula for Undergraduate Medical Education. Association of American Medical Colleges; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 8.March C, Walker LW, Toto RL, Choi S, Reis EC, Dewar S. Experiential communications curriculum to improve resident preparedness when responding to discriminatory comments in the workplace. J Grad Med Educ. 2018;10(3):306–310. 10.4300/JGME-D-17-00913.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wheeler DJ, Zapata J, Davis D, Chou C. Twelve tips for responding to microaggressions and overt discrimination: when the patient offends the learner. Med Teach. 2019;41(10):1112–1117. 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1506097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilkins KM, Goldenberg MN, Cyrus KD. ERASE-ing patient mistreatment of trainees: faculty workshop. MedEdPORTAL. 2019;15:10865 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldenberg MN, Cyrus KD, Wilkins KM. ERASE: a new framework for faculty to manage patient mistreatment of trainees. Acad Psychiatry. 2019;43(4):396–399. 10.1007/s40596-018-1011-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goodman DJ Promoting Diversity and Social Justice: Educating People From Privileged Groups. 2nd ed Routledge; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nadal KL A guide to responding to microaggressions. CUNY Forum. 2014;2(1):71–76. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whitgob EE, Blankenburg RL, Bogetz AL. The discriminatory patient and family: strategies to address discrimination towards trainees. Acad Med. 2016;91(11):S64–S69. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bosse HM, Schultz JH, Nickel M, et al. The effect of using standardized patients or peer role play on ratings of undergraduate communication training: a randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;87(3):300–306. 10.1016/j.pec.2011.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bryan AF, Bryan DS, Matthews JB, Roggin KK. Toward autonomy and conditional independence: a standardized script improves patient acceptance of surgical trainee roles. J Surg Educ. 2020;77(3):534–539. 10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hock LE, Scruggs B, Oetting TA, Abràmoff MD, Shriver EM. Tools for responding to patient-initiated verbal sexual harassment. EyeRounds.org. Updated August 20, 2019. Accessed August 2, 2020. https://EyeRounds.org/tutorials/sexual-harassment-toolkit/index.htm

- 18.Khamis NN, Satava RM, Alnassar SA, Kern DE. A stepwise model for simulation-based curriculum development for clinical skills, a modification of the six-step approach. Surg Endosc. 2016;30(1):279–287. 10.1007/s00464-015-4206-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pratt CC, McGuigan WM, Katzev AR. Measuring program outcomes: using retrospective pretest methodology. Am J Eval. 2000;21(3):341–349. 10.1016/S1098-2140(00)00089-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

- Facilitator Guide.docx

- Presentation.pptx

- Harassment Tool Kit.pdf

- Pre- and Postworkshop Survey.docx

All appendices are peer reviewed as integral parts of the Original Publication.