Abstract

Pediatric therapy-related myeloid neoplasms (tMN) occur in children after exposure to cytotoxic therapy and have a dismal prognosis. The somatic and germline genomic alterations that drive these myeloid neoplasms in children and how they arise have yet to be comprehensively described. We use whole exome, whole genome, and/or RNA sequencing to characterize the genomic profile of 84 pediatric tMN cases (tMDS: n = 28, tAML: n = 56). Our data show that Ras/MAPK pathway mutations, alterations in RUNX1 or TP53, and KMT2A rearrangements are frequent somatic drivers, and we identify cases with aberrant MECOM expression secondary to enhancer hijacking. Unlike adults with tMN, we find no evidence of pre-existing minor tMN clones (including those with TP53 mutations), but rather the majority of cases are unrelated clones arising as a consequence of cytotoxic therapy. These studies also uncover rare cases of lineage switch disease rather than true secondary neoplasms.

Subject terms: Cancer genomics, Acute myeloid leukaemia, Myelodysplastic syndrome, Gene expression

Paediatric therapy-related myeloid neoplasms (tMN) have a dismal prognosis and have not been comprehensively profiled. Here the authors characterise the molecular landscape of 84 paediatric tMN patients, and find that, unlike adult tMNs, these do not emerge from pre-existing clones and that MECOM dysregulation is frequent.

Introduction

Although the therapeutic regimens for pediatric cancer have improved with a resultant overall decrease in the incidence of tMN in children1–4, approximately 0.5–1.0% of children continue to develop tMN after therapy for hematological, solid, and CNS malignancies2. Children with tMN have a worse prognosis compared to de novo MDS/AML, with 5-year survival rates of 6–11% if not treated with hematopoietic cell transplant (HCT)1,2. While much effort has focused on tMN in adults5–9, a complete understanding of the pathogenesis of tMN in children is lacking despite well-described associations with alkylating agents (e.g., cyclophosphamide), topoisomerase II inhibitors (e.g., the epipodophyllotoxins etoposide and teniposide), radiation therapy, and HCT10–14. Epipodophyllotoxin-associated tMN is strongly associated with KMT2Ar10,15.

Here, using a comprehensive sequencing approach, we show that Ras/MAPK pathway mutations, alterations in RUNX1 or TP53, and KMT2A rearrangements are frequent somatic drivers in pediatric tMN, and we find that in some cases aberrant MECOM expression is secondary to enhancer hijacking. Additionally, using samples from serial timepoints, we find no evidence of pre-existing minor tMN clones (including those with TP53 mutations) like in adults with tMN5–7, but rather the majority of cases are unrelated clones arising as a consequence of cytotoxic therapy.

Results

Sequencing of pediatric tMN samples

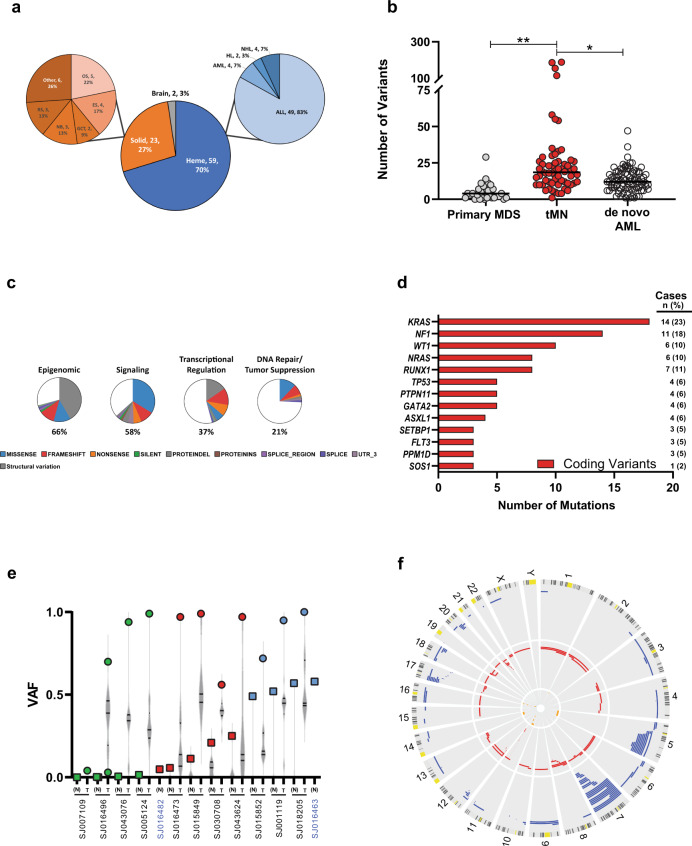

Eighty-four pediatric tMN cases, including tMDS (n = 28) and tAML (n = 56), were profiled, including both tumor and non-tumor tissue for 62 cases and only non-tumor material for 22 cases (Table 1 & Supplementary Data 1). Initial diagnoses included hematologic (70%), solid (27%), and brain (3%) neoplasms (Fig. 1a). The median age at tMN was 13.6 years (range: 1.2–24.6 yrs) (Supplementary Fig. 1a, b, & Supplementary Data 2), and the time to tMN after initial diagnosis varied widely (median: 2.9 yrs; range: 0.7–16.2 yrs) (Supplementary Fig. 1c–e, & Supplementary Data 3). Somatic variants identified from WGS (median coverage: 50x) or WES (112x) were validated by targeted resequencing (641x) (Supplementary Data 4–8).

Table 1.

Sequencing Approach for the Pediatric tMN Cohort.

| Cases | WGS | WES | RNA Seq | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unique patients | 84 | ||||

| Tumor-normal pairs | |||||

| tMDS | 23 | 3 | 23 | 19 | |

| tAML | 39 | 13 | 35 | 37 | |

| Normal only | |||||

| tMDS | 5 | 5 | |||

| tAML | 17 | 17 | |||

| Total | 84 | 16 | 80 | 56 |

Fig. 1. Clinical and genomic features of the pediatric tMN cohort.

a Pie charts depicting the distribution of initial diagnoses within the pediatric tMN cohort. AML acute myeloid leukemia, HL Hodgkin lymphoma, NHL non-Hodgkin lymphoma, ALL acute lymphoblastic leukemia, OS osteosarcoma, ES Ewing sarcoma, GCT germ cell tumor, NB neuroblastoma, RS rhabdomyosarcoma, Other includes: embryonal sarcoma, Wilms tumor, rhabdoid tumor, ovarian carcinoma, and peripheral neuroepithelioma. b Total number of somatic mutations per patient (includes the following mutation types: silent, nonsense, frameshift, indel, splice site, ITD, RNA coding genes, 3′ and 5′ UTR) compared to pediatric primary MDS16 and de novo AML17.*p < 0.001; **p < 0.0001. Black bar indicates the median. Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney non-parametric, two-tailed test used to compare biologically independent samples from n = 62 tMN, n = 32 primary MDS, and n = 87 de novo AML cases. c Pie charts showing the distribution of recurrently mutated pathways in the pediatric tMN cohort and the distribution of mutation types within each pathway. Percentages refer to the frequency of mutations within a pathway amongst all somatic mutations present in the cohort. d The genes most frequently mutated (somatic) in pediatric tMN—Only coding variants are shown. e VAF plot showing the 13 patients with TP53 mutations (SNV or indel). Tumor (T; circles) and normal (N; squares) are shown for each unique patient. Green symbols denote cases with VAFs suggesting somatic variants, blue symbols denote cases with clear germline variants in the normal tissue, and red symbols denote cases with TP53 mosaicism. *p < 0.01 for binomial mosaicism test. Violin plots represent the range of VAFs for all somatic variants in that case. Black bars indicate the median and upper and lower quartiles. Note: SJ016482 and SJ016463 are from the normal only group of patients (blue font). f Circos plot showing copy number alterations found via WES (n = 58) & WGS (n = 4) analysis of 62 tumor/normal pairs. Circumferential numbers indicate chromosome number, blue lines = deletions, red lines = amplifications, and orange lines = CN-LOH.

A mean of 28 (range: 1–188) somatic mutations per patient were identified, which is significantly greater than the mutational burden found in pediatric primary MDS (5 mutations/patient, p < 0.001) and pediatric de novo core-binding factor AML (13 mutations/patient, p < 0.001)(Fig. 1b)16,17. Four patients had mutation burdens greater than 2 standard deviations above the mean, ranging from 115 to 188 mutations/patient (Supplementary Fig. 2a). We detected DNA repair pathway gene (PMS2; n = 2, MSH6; n = 1) alterations in 3 of these hypermutated cases (Supplementary Data 9). In the fourth case (SJ016473), the hypermutation status appears to be driven by variants with variant allele frequency (VAF) < 0.2 (Supplementary Fig. 2b), and the corresponding driver alteration could have escaped detection due to limited depth. Including multiple modes of somatic alterations (SNV, CNV, & fusions), we used the Genomic Random Interval (GRIN) model18 to identify 91 genes that were significantly altered in this cohort (Supplementary Data 10). The most common altered functional pathways were epigenomic (n = 57 of 62, 92%) and cell signaling (n = 46 of 62, 74%), with mutations in the Ras/MAPK pathway, including KRAS and NF1, and mutations or structural alterations involving RUNX1 and KMT2A being the most frequent (Fig. 1c,d, & Supplementary Data 11).

Putative germline variants in pediatric tMN

Fourteen pathogenic or likely pathogenic presumed germline sequence alterations were identified in 13 of 84 patients (15%, 95% exact binomial CI: 8.5–25.0%) (Table 2 & Supplementary Data 12–14), indicating that germline alterations may be more common in tMN than the published prevalence of 8.5–10% in other groups of children with cancer19–22. This includes 4 patients with germline TP53 mutations. There was also evidence of TP53 mosaicism in the non-tumor tissue in 5 additional patients (Fig. 1e & Supplementary Data 15). Collectively, 15 patients (18%) had somatic (mutation and/or copy number alteration) or germline alterations in TP53 (Supplementary Fig. 3). There was a significant enrichment of complex cytogenetics in patients with TP53 alterations (11 of 13) versus wild-type TP53 patients when considering those with comprehensive sequencing (n = 62, 85% vs. 12%; Fisher’s p < 0.0001) (Supplementary Fig. 3e). Three other patients had low VAF somatic truncating mutations in exon 6 of PPM1D (Supplementary Fig. 4)23,24. Despite the fact that deletions or CN-LOH involving chromosome 7 (del(7)) were the most common copy number alteration (22 of 62, 35%) (Fig. 1f, Supplementary Fig. 5, & Supplementary Data 16), germline mutations in SAMD9, SAMD9L, GATA2, or RUNX1 were not present16,25–27. The comprehensive mutational profile of pediatric tMN is shown in Fig. 2a.

Table 2.

Pathogenic and Likely Pathogenic Germline Variants Present in the Pediatric tMN Cohort.

| Case | 1° Diagnosis | 2° Dx | Gene | RefSeq accession | Mutation type | Amino acid change | VAF | REVEL score | ACMG classification (criteria) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SJ016504 | NHL | tAML | ARID2 | NM_152641 | nonsense | p.R1272X | 0.53 | LP (PVS1, PM2) | |

| SJ016509 | ALL | tMDS | CREBBP | NM_004380 | missense | p.R1446C | 0.35 | 0.952 | LP (PS2, PM2, PP3) |

| SJ043618 | ALL | tAML | ETV6 | NM_001987 | nonsense | p.R359X | 0.56 | P (PVS1, PS3, PM2, PP1) | |

| SJ021960 | ALL | tMDS | ETV6 | NM_001987 | frameshift | p.N386fs | 0.30 | P (PVS1, PS3, PM2) | |

| SJ004031 | ALL | tMDS | EZH2 | NM_001203247 | missense | p.R685H | 0.43 | 0.907 | LP (PM2, PP2, PP3) |

| SJ016496 | ALL | tAML | NF1 | NM_000267 | nonsense | p.R2496X | 0.50 | P (PVS1, PM2, PP1) | |

| SJ016519 | ALL | tAML | PMS2 | NM_000535 | missense | p.S46I | 0.34 | 0.939 | LP (PS3, PP1, PM3, PP3) |

| SJ004031 | ALL | tMDS | PTPN11 | NM_002834 | missense | p.S502L | 0.39 | 0.976 | LP (PM1, PM2, PP2, PP3) |

| SJ043615 | ALL | tAML | RPL22 | NM_000983 | splice | E40_E3splice | 0.44 | LP (PVS1, PM2) | |

| SJ016463 | Osteosarcoma | tMDS | TP53 | NM_000546 | missense | p.R337C | 0.58 | 0.715 | P (PS3, PM1, PM2, PP2, PP3) |

| SJ001119 | Osteosarcoma | tAML | TP53 | NM_000546 | missense | p.R337L | 0.58 | 0.765 | P (PS3, PM1, PM2, PM5, PP3) |

| SJ015852 | ALL | tMDS | TP53 | NM_000546 | nonsense | p.W53X | 0.52 | P (PVS1, PM2, PP4) | |

| SJ018205 | Anaplastic Astrocytoma | tMDS | TP53 | NM_000546 | missense | p.H179Y | 0.50 | 0.948 | P (PS2, PS3, PM1, PM2, PP1, PP3) |

| SJ016486 | ALL | tAML | TRIP11 | NM_004239 | frameshift | p.Q1367fs | 0.40 | LP (PVS1, PM2) |

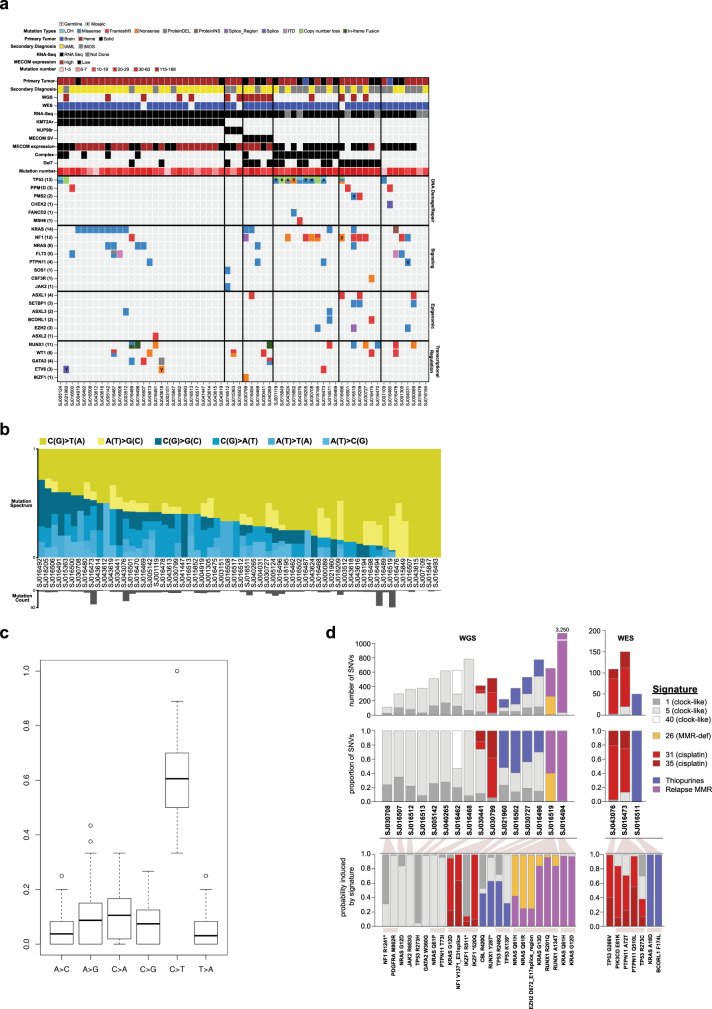

Fig. 2. Comprehensive mutational spectrum of pediatric tMN.

a Heat map showing the integrated analysis of the pediatric tMN cohort with tumor and non-tumor material (n = 62). b Mutational spectrum of 62 tumor/normal pairs. Yellow and blue bars show the relative contribution of transitions and transversion. Gray bars at bottom indicate number of mutations present for each patient. c Bar graph showing the mean relative contribution of each transition or transversion. C > T transitions are the most common transition or transversion in 60 of 62 patients (96.7%; 95% CI: 88.8–99.6%; p = 2.7 × 10−44 by exact binomial test). Boxes delineate the upper and lower quartiles and the black bar indicates the median. d Mutation signature analysis on 16 cases with available WGS and 3 cases with WES with >30 SNVs. Top: absolute number of SNVs and the contribution of specific COSMIC, thiopurine, and relapse MMR signatures. Middle: relative contribution of specific COSMIC, thiopurine, and relapse MMR signatures. Bottom: select disease relevant mutations present in each patient and the probability that each is induced by the indicated mutational process.

Mutational signatures of pediatric tMN

C > T transitions were the predominant mutation type (Fig. 2b, c). Mutational signature analysis on the 16 WGS cases and 3 WES cases with a sufficient quantity of SNVs (>30) identified drug signatures in 9 cases, including 4 with the cisplatin signature (COSMIC 31 & 35), and 5 with the thiopurine signature28, consistent with the prior treatment history (Supplementary Data 17). Eight cases did not have a detectable drug signature but rather clock-like signatures 1, 5, and 40 (Fig. 2d)29,30, while 2 additional patients had a signature similar to one of unknown etiology recently reported in relapsed mismatch repair (MMR)-deficient ALL31 which we term the “relapse MMR” signature. Both had germline (SJ016519) or somatic (SJ016494) pathogenic PMS2 mutations. The relapse MMR signature bore similarities to the thiopurine signature (Supplementary Fig. 6), had similar strand bias to the thiopurine signature28 (Supplementary Fig. 7), and occurred in patients with previous thiopurine exposure, thus suggesting it was a variant of the thiopurine signature that occurs under MMR-deficient conditions. We determined the probability that driver SNVs were caused by each signature as reported previously28 (Fig. 2d, bottom), and found that 2 TP53 mutations were most likely (>50% probability) induced by cisplatin or thiopurines along with several Ras pathway and other variants. Example calculations showing the probability that specific driver mutations were caused by individual signatures are shown in Supplementary Fig. 8. These calculations are based on the signatures present in each sample and their mutation preference at specific trinucleotide contexts; thus, two KRAS G12D mutations in two different patients (SJ030799 and SJ016494) were likely caused by different mutational processes due to the presence of different signatures in the two samples.

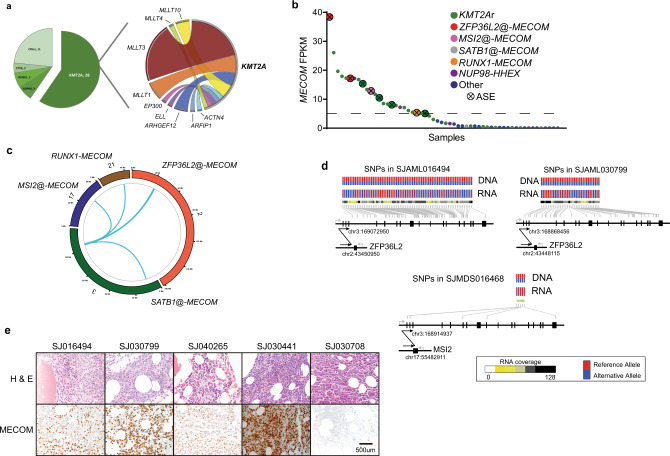

Chromosomal rearrangements present in pediatric tMN

Chromosomal rearrangements encoding fusion oncoproteins were identified by RNA-seq in 70% of cases (39 of 56 with available RNA). KMT2A fusions were the most common (n = 28, 60%, GRIN p = 1.86 × 10−74)(Fig. 3a, Supplementary Data 18–20, & Supplementary Fig. 9) and other in-frame fusions previously reported in myeloid malignancies involving NUP98 (n = 3) and ETV6 (n = 2) were also observed32–34. Likewise, 3 in-frame RUNX1 fusions (RUNX1-MTAP, RUNX1-LYPD5, and RUNX1-MECOM) were identified (Supplementary Figs. 10 & 11). In addition to the RUNX1-MECOM fusion, we noted variable expression levels of MECOM across the cohort (FPKM range: 0.004–38.4), and 24 cases (43%) had an FPKM > 5 (MECOMHigh) (Fig. 3b). Elevated MECOM expression has been associated with myeloid neoplasms, particularly tMN and those with KMT2Ar, and is associated with a poor prognosis in both adult and pediatric myeloid neoplasms34–39. KMT2Ar was significantly enriched in the MECOMhigh cases (KMT2Ar: 18 vs. no KMT2Ar: 6, Fisher’s p < 0.01) (Supplementary Fig. 12) while another MECOMhigh patient had a NUP98 fusion (NUP98-HHEX)(Fig. 3b & Supplementary Fig. 10b), a previously reported association with high MECOM expression40–42. WGS on 3 of the 4 remaining MECOMhigh cases revealed structural variations (SV) involving the MECOM locus on chromosome 3 (Fig. 3c). Two cases involved noncoding regions of chromosome 2 adjacent to ZFP36L2, a gene encoding an RNA binding protein that is highly expressed in hematopoietic cells and is involved in hematopoiesis, and the other involved noncoding regions of chromosome 17 adjacent to MSI2, another gene encoding an RNA binding protein that has been found to be recurrently rearranged in hematological malignancies (Fig. 3d)43–47. The existing ENCODE data and similar studies in human CD34 cells support that these regions of the genome are super-enhancers in hematopoietic cells, suggesting a proximity effect in which these enhancers have been hijacked to drive high levels of MECOM expression (Supplementary Fig. 13)48,49. Furthermore, despite the lack of in-frame fusions in the RNA-seq data, these cases demonstrate allele-specific MECOM expression50, further suggesting a cis-regulatory element may be driving this aberrant expression (Fig. 3d). WGS also identified a MECOM SV in SJ030441 (SATB1@-MECOM), but elevated MECOM RNA levels were not present in this case (Fig. 3b); however, immunohistochemical studies on the patient material demonstrated high MECOM protein expression in the blasts (Fig. 3e). Similar MECOM protein expression was detected in the other MECOM altered cases51, but not in tMN cases without a MECOM SV (Fig. 3e). Contrary to pediatric de novo AML studies, there was not a statistically significant association between higher MECOM expression and disease-related deaths within this pediatric tMN cohort (Supplementary Fig. 14)36. Rather, a multivariable analysis shows that the presence of complex cytogenetics does significantly impact disease-related mortality risk (Fine-Gray model HR = 2.17; p = 0.04).

Fig. 3. Structural variations and MECOM dysregulation in pediatric tMN.

a Pie chart showing the distribution of in-frame fusions (n = 47) found in the pediatric tMN cohort (left). Ribbon plot showing the KMT2A binding partners found in pediatric tMN (right). The weight of the ribbon correlates to the frequency of the fusion. b MECOM FPKM plot for cases with RNA-Seq (n = 56). Dashed line indicates the level above which cases were classified as MECOMHigh. ASE allele specific expression. c Circos plot indicting the MECOM SVs found in the pediatric tMN cohort. Chromosome number and specific SV is listed around outside of ring. d Allele-specific RNA expression resulting from structural variants50. Heterozygous SNPs (genomic positions indicated by gray lines; red: reference allele; blue: alternative allele) detected in tumor DNA exhibited mono-allelic expression in tumor RNA. Structural alterations are indicated by arrows with breakpoints listed. Sequencing depth for each SNP in RNA-Seq are indicated as a heatmap. e Photomicrographs of bone marrow core biopsy of 4 cases with high MECOM expression (right panels: MECOM (Evi-1) IHC: 1C50E12, Cell Signaling Technology, dilution: 1:500) and a control case (SJ030708) with low/absent MECOM expression. Immunohistochemistry was performed once on the patient material available. All images are at equal magnification (20x).

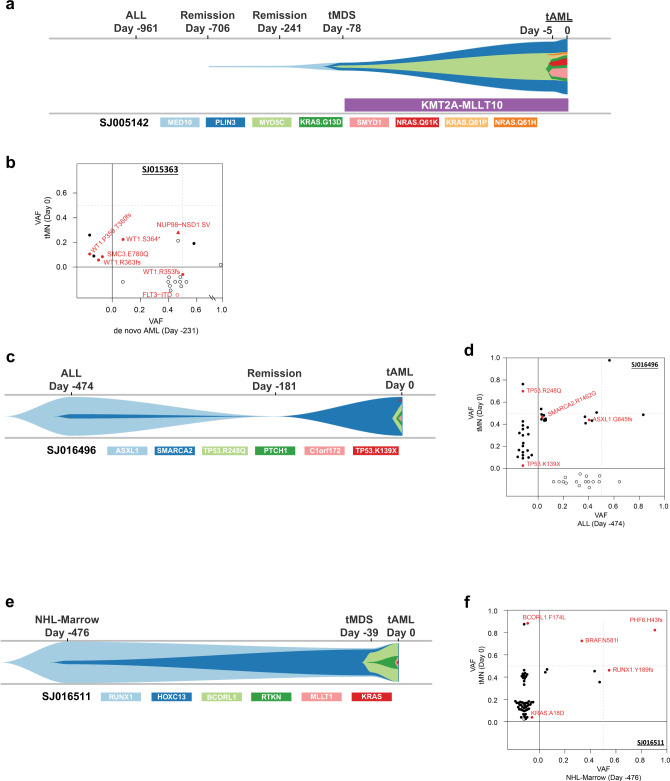

Clonal evolution of pediatric tMN

Finally, using a combination of targeted capture resequencing and a bioinformatic error suppression approach52 we described the timing of acquisition and evolution of the somatic mutations for 37 cases using samples from interval time points prior to the development of tMN, including 26 cases in which material for the primary malignancy was available for analysis (Supplementary Data 21). We demonstrated that the somatic variants most commonly arose after the introduction of cytotoxic therapy (n = 23 of 26, 88%), and we could detect these acquired mutations up to 748 days (mean: 405 days; range: 118–748) prior to morphologic evidence of tMN (Fig. 4a & Supplementary Figs. 15 & 16). Three cases were found to be clonally related to the original malignancy. These included a tMDS that developed 8 months after AML and both were found to harbor a NUP98-NSD1 fusion (Fig. 4b) with multiple discrete WT1mut subclones, and 2 cases where the initial lymphoid malignancy (ALL or NHL) and tMN developed from a common clone that subsequently underwent a lineage switch (Fig. 4c–f). Unlike adult tMN5, the somatic TP53 variants could not be detected with ultra-deep amplicon sequencing (72,000x) and bioinformatic error suppression in pre-treatment samples52 (Supplementary Data 22 & Supplementary Fig. 17).

Fig. 4. Clonal evolution of pediatric tMN.

a A river plot showing a representative case where tMN variants occurred only after exposure to cytotoxic therapy. In this case the founding tMN clone was detectable 628 days prior to morphologic diagnosis of tMDS. b A 2-dimensional VAF plot showing that the tMN and de novo AML were actually related via a NUP98-NDS1 fusion (red triangle) and a subclonal WT1 variant. c, d River- and 2d-plots showing an ALL related to the subsequent tMN through an ASXL1-mutant founding clone with a SMARCA2 subclone, and following chemotherapy an outgrowth of the SMARCA2 clone with subsequent acquisition of 2 TP53 subclones. e, f River- and 2d-plots showing staging bone marrow collected at time of NHL diagnosis related to the subsequent tMN through a RUNX1 founding clone with eventual acquisition BCORL1 and KRAS subclones, which paralleled the development of tMDS and tAML, respectively. 2-d plot NOTE: upper right-hand quadrant contains shared variants between the 2 time-points (X and Y axes). Open symbols indicate variants with WGS or WES only. Closed symbols indicate variants validated via capture resequencing.

Discussion

Here we show the results of our comprehensive sequencing of pediatric tMN which reveals that KMT2Ar are the most common driver alterations in our pediatric tMN cohort along with Ras/MAPK pathway mutations. Somatic TP53 alterations were also frequent, but these mutations appeared to arise after chemotherapy, unlike adult tMN5. Additionally, we identified MECOM overexpression to be frequent, and in some of these cases the overexpression was driven by enhancer hijacking. Finally, we show that pediatric tMN-defining variants arise most commonly as a consequence of cytotoxic therapy, and that these malignant clones can be identified, on average, >1 year before morphologic evidence of neoplasm. While these studies reflect the experience of a single institution, the findings highlight the diverse nature of genomic alterations in pediatric tMN and suggest that genomic screening approaches may be able to identify at risk patients prior to tMN development.

Methods

Patient sample details

Patient material was obtained with written informed consent using a protocol approved by the St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital Institutional Review Board. All patients with a diagnosis of tMN (either tMDS or tAML) with appropriate consent for genomic studies and available tumor or normal samples banked in the St. Jude Tissue Biorepository were included. Diagnoses were reviewed by a hematopathologist (J.M.K.) and classified according to the WHO 2016 classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia53. Supplementary Data 1 contains clinicopathological information for all samples included in our analyses. Samples were de-identified before nucleic acid extraction and analysis. The study cohort is comprised of 84 total patients (tMDS = 28, tAML = 56). Sixty-two patients had available tumor and normal tissue for characterization, while the remaining 22 lacked sufficient tumor material for comprehensive sequencing (Table 1). For the 62 tumor/normal pairs, flow sorted lymphocytes from the diagnostic tMN samples were used as the source of normal comparator genomic DNA in 53 cases, while bone marrow (n = 4) or peripheral blood (n = 5) from alternate timepoints was used for the remainder. Cryopreserved bulk bone marrow cells were thawed in a 37 °C water bath and transferred to 20% FBS in PBS to remove residual DMSO according to standard approaches54. Cells were lysed with ACK lysing buffer (ThermoFisher A1049201) and washed with PBS prior to staining. The following antibodies were used to immunophenotype the cells and facilitate flow sorting of myeloid and lymphoid populations: CD15-FITC (eBioscience, clone HI98), CD71-BV711 (BD Biosciences, clone M-A712), CD34-PE (Beckman, clones QBEnd10, Immu133, Immu409), CD45R-PerCP-Cy5.5 (eBioscience, clone RA3-6B2), CD235a-PE-Cy7 (BD Biosciences, clone GA-R2), CD3-APC-Cy7 (BD Biosciences, clone SK7), CD33-APC (eBioscience, clone WM-53). For the 23 normal only cases, bulk sequencing was completed on interval remission samples.

WGS, WES, and RNA-Seq analysis

DNA and RNA material was isolated from bulk myeloid or isolated lymphocytes by standard phenol:chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. Whole genome sequencing libraries were constructed using the TruSeq DNA PCR-Free sample preparation kit (Illumina, Inc., CA) following the manufacturer’s instructions and whole-exome sequencing was completed using the Nextera Rapid Capture Expanded Exome reagent (Illumina). After library quality and quantity assessment, WGS, WES, or RNASeq samples were sequenced on various Illumina platforms (HiSeq 2500, HiSeq 4000, or NovaSeq 6000). Mapping, coverage, quality assessment, single-nucleotide variant (SNV) and indel detection, and tier annotation for sequence mutations (SNVs discovered by WGS were classified as tier 1, tier 2, tier 3, or tier 4) have been described previously55–57 and briefly described here. DNA reads were mapped using BWA58,59 (WGS: v0.7.15-r1140; WES: v0.5.9-r26-dev and v0.7.12-r1039 since data were generated over a period of time) to the GRCh37/hg19 human genome assembly. Aligned files were merged, sorted and de-duplicated using Picard tools 1.65 (broadinstitute.github.io/picard/). SNVs and Indels in WGS and WES were detected using Bambino60. For WGS data, sequence variants were classified into the following four tiers: (i) tier 1: coding synonymous, nonsynonymous, splice-site and noncoding RNA variants; (ii) tier 2: conserved variants (conservation score cutoff of greater than or equal to 500, based on either the phastConsElements28way table or the phastConsElements17way table from the UCSC Genome Browser) and variants in regulatory regions annotated by UCSC (regulatory annotations included are targetScanS, ORegAnno, tfbsConsSites, vistaEnhancers, eponine, firstEF, L1 TAF1 Valid, Poly(A), switchDbTss, encodeUViennaRnaz, laminB1 and cpgIslandExt); (iii) tier 3: variants in non-repeat masked regions; and (iv) tier 4: the remaining SNVs. Structural variations in whole-genome sequencing data were analyzed using CREST61 (v1.0). RNA-sequencing was performed using TruSeq Stranded Total RNA library kit (Illumina) and analyzed, as previously described16,17. Briefly, RNA reads were mapped using our StrongARM pipeline (internal pipeline, described by Wu et al.62). Paired-end reads from RNA-seq were aligned to the following four database files using BWA: (i) the human GRCh37-lite reference sequence, (ii) RefSeq, (iii) a sequence file representing all possible combinations of non-sequential pairs in RefSeq exons and, (iv) the AceView database flat file downloaded from UCSC representing transcripts constructed from human ESTs. Additionally, they were mapped to the human GRCh37-lite reference sequence using STAR. The mapping results from databases (ii)–(iv) were aligned to human reference genome coordinates. The final BAM file was constructed by selecting the best of the five alignments. Chimeric fusion detection was carried out using CICERO63 (v0.3.0) and Chimerascan64 (v0.4.5). All identified fusions were validated by either RT-PCR, cytogenetics, manual review of CREST data, or a combination of these methods (Supplementary Data 18, 20, & Supplementary Figs. 9 and 18). Mapping statistics and coverage data are described in Supplementary Data 6–8 & 15. Recurrent SNV’s identified by WGS or WES were validated by custom capture resequencing (Supplementary Data 2, 3, and 19). Custom capture baits were designed (Twist Biosciences) to be 80 nucleotides long covering the provided hg19 target region consisting of 1,006,633 unique base pairs (bp). A total target region of 904,622 bp is directly covered by 11,455 probes. BWA58,59 (v0.7.12) MEM algorithm was used to map the TWIST sequencing reads to the GRCh37/hg19 human genome assembly. Rsamtools65 (v1.30.0) was used to retrieve read counts from BAM files for the SNV/Indels called in WES, requiring MAPQ > = 1 and base quality Phred score > = 20. We also performed de novo mutation calling in an attempt to catch canonical low variant allele frequency (VAF) cancer gene mutations missed by WES using VarScan 266 (v2.3.5) on the TWIST data with the following criteria: MAPQ > = 1; base quality Phred score > = 20; VAF > = 0.01 and variant call p-value < = 0.05. Selected somatic variants (WES read count <5 and targeted capture read count <10) and all somatic TP53 variants identified via WES were validated by custom amplicon sequencing. PCR primers (Supplementary Data 22) were designed to flank the putative variants. Amplicon sizes were approximately 200 base pairs. PCR was performed using KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix (Roche), 100 nM of each primer (IDT) and 20 ng of gDNA in a 40uL reaction volume. Thermocycling was performed using the following parameters: 95 °C for 3 min; 98 °C for 20 s, 62 °C for 15 s, and 72 °C for 15 s for a total of 30 cycles; and 72 °C for 1 min. All amplicons were quality checked on a 2% agarose gel. Primers were designed to incorporate Illumina overhang adapter sequences which allowed for indexing using the Nextera XT Index kit (Illumina) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Libraries were normalized, pooled, and sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq instrument using a 2 × 150 paired-end version 2 sequencing kit. We used the CleanDeepSeq52 approach with default settings for error suppression in this ultra-deep amplicon sequencing.

Copy number analysis using NGS data

Copy number analysis of the WGS (n = 4) cases was done using CONSERTING67. Copy number analysis of the WES (n = 58) cases was done following these steps: Samtools68 (v1.2) mpileup command was used to generate an mpileup file from matched normal and tumor BAM files with duplicates removed; VarScan266 (v2.3.5) was then used to take the mpileup file to call somatic CNAs after adjusting for normal/tumor sample read coverage depth and GC content; Circular Binary Segmentation algorithm69 implemented in the DNAcopy R package70 was used to identify the candidate CNAs for each sample; B-allele frequency info for all high quality dbSNPs heterozygous in the germline sample was also used to assess allele imbalance.

Germline analysis

Whole exome sequencing data were analyzed using internal workflows that were previously described19. Briefly, the sequencing data were analyzed for the presence of single-nucleotide variants and small insertions and deletions (Indels) and for evidence of germline mosaicism. Germline copy-number variations and structural variations were identified with the use of the Copy Number Segmentation by Regression Tree in Next Generation Sequencing (CONSERTING)67 and Clipping Reveals Structure (CREST)61 algorithms. For all SNPs and Indels, functional prediction (e.g., SIFT, CADD, and Polyphen) scores and population minor allele frequency (MAF) were annotated. In this work, 3 databases were used for population MAF annotation: (i) NHLBI GO Exome Sequencing Project (http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/); (ii) 1000 genomes (http://www.internationalgenome.org); and (iii) ExAC non-TCGA version (http://exac.broadinstitute.org/). For missense mutations, REVEL (rare exome variant ensemble learner) score was also determined to help predict pathogenicity71. A gene list of 631 genes were composed from various resources: (i) literature review of genes that are potentially involved in AML, MDS, inherited bone marrow failure syndromes, as well as other cancer types5,19,72–74 (ii) genes that were involved in splicing from predefined pathways (e.g., splicing) in KEGG, GeneOntology, Reactome, Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA), and NCBI (Supplementary Data 14). The following filtering criteria were applied: VAF ≥ 0.2, coverage >20x, ExAC MAF < 0.001 (or not present in ExAC), REVEL score >0.5 (for missense mutations), NHLBI and 1000 genomes MAF < 0.001. One TP53 variant that was lost through this filtering was manually recovered because the patient was clinically diagnosed with Li Fraumeni syndrome. Given this finding, all germline TP53 mutations were manually reviewed and analyzed as described below for mosaicism. Of note, the germline ETV6 p.N386fs in case SJ021960 was previously reported75. All non-synonymous mutations were comprehensively reviewed and classified as pathogenic, likely pathogenic, of uncertain significance, likely benign, or benign based on recommendations from the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology76 by members of the Cancer Predisposition Division at St. Jude (J.L.M and K.E.N).

Determination of mosaicism versus tumor-in-normal contamination

Because the normal samples used were hematopoietic specimens (sorted lymphocytes or remission bulk marrow), the mosaic mutations can be a result of incomplete remission. To rule out this possibility, we performed a previously developed statistical analysis that can model residual disease burden19. Briefly, we first determined purity (denoted as f) of the tMN tumor sample by clustering allele fractions of somatic SNVs/Indels by using R package “Mclust,” where the cluster with the highest mean (denoted as u) center under 0.5 was used to estimate tumor purity (multiplied by 2 to account for diploid status, f = 2*u). To account for clonal evolution, we also calculated tumor purity by using heterozygous loss and copy neutral loss of heterozygosity (CN-LOH) regions with the highest magnitude of scores. For heterozygous loss regions, the purity is estimated as f = 2–2(log.ratio+1),while for CN-LOH region the purity is estimated as f = 2*AI where AI = | B-allele fraction – 0.5 | . The maximum of the SNV/Indel and CNV/LOH-based purity estimate was used as the final purity estimate (f) for a given tumor. We then defined an SNV/Indel as diploid clonal if its allele fraction is > f*0.5*80% = u*80% and <0.6. The sum of mutant allele counts of these markers was denoted as M, and the sum of depth of these markers as T, thus the tumor-in-normal contamination level of the germline sample is then estimated as c = M/T. The expected allele fraction of TP53 mutation is estimated by considering its local ploidy and contamination level c. In our dataset, the TP53 mutations are either 1-copy loss-LOH or CN-LOH (Supplementary Data 1, 4, and 16). For 1-copy-LOH, the expected allele fraction of TP53 under contamination is e = c*(2-c)−1, while for CN-LOH the expected allele fraction of TP53 is simply e = c. We then tested the hypothesis that the observed TP53 allele counts in germline sample are due to contamination by using a binomial test. A significant p value (<0.01), after Bonferroni correction, would indicate that the observed allele counts are unlikely to be explained by contamination. To rule out the possibility of germline inheritance, we also tested the allele counts against inheritance (i.e., e = 0.5). A TP53 mutation with significant p values (<0.01) for both the contamination test and the inheritance test is called a mosaic mutation. For normal only samples, variants with a VAF of ≥0.2 were classified as germline, but variants with a VAF of <0.2 and with a supportive clinical history were classified as mosaic. We are unable to distinguish germline versus somatic mosaicism.

Mutational signature analysis

The trinucleotide context of each somatic SNV was identified using an in-house script, and mutations were assigned to one of each of the 96 trinucleotide mutation types77. To detect whether any novel signatures were present in the dataset, we ran SigProfiler version 2.3.178 on the SNV catalogs from the 16 WGS samples and extracted 3 signatures. One of the extracted signatures resembled the cisplatin signature (SBS-31); one represented a combination of clock-like signatures 1 and 5 (SBS-1, SBS-5)77, and the third resembled a signature recently reported in relapsed ALL of unknown cause which was only present in patients with germline or somatic PMS2 alterations. This third signature (termed the “relapse MMR” signature) was also similar to the thiopurine signature we recently reported28, with similar strand bias, and is potentially therefore a modified thiopurine signature in samples with MMR defects. We tested for the presence of the 60+ COSMIC v3 signatures in each WGS sample using SigProfilerSingleSample (version 1.3) and the COSMIC v3 signature definitions provided with that version of the software. From this analysis, signatures never exceeding 150 mutations in any one sample were identified and excluded from our final analysis in order to avoid likely spurious signatures. Based on these data, our finalized WGS signature data were obtained by testing for the presence of only the following signatures in each sample using SigProfilerSingleSample: COSMIC signatures 1, 5, and 40 (clock-like), COSMIC signature 26 (MMR deficiency), COSMIC signatures 31 and 35 (cisplatin), the experimental thiopurine signature we recently reported, generated by treating MCF10A cells with thioguanine28, and the relapse MMR signature. We used a required cosine increase of 0.02 or more for a signature to be detected in a single sample, and default parameters otherwise. For exome samples, we likewise tested for these signatures using SigProfilerSingleSample, but excluded from our analysis exome samples that had cosine reconstruction scores of less than 0.9 (comparing the sample’s SNV catalog profile with the profile as reconstructed by signatures) or less than 30 SNVs total, or which already had WGS data, resulting in only 3 exome samples with usable signature data. We calculated the probability that individual SNVs were caused by a signature as done by others79 and as we reported previously28. The probability that a variant was caused by a specific signature was calculated as follows. Let sk represent the signature strength vector for a given sample (measured in number of SNVs caused by the signature), where k = 1, 2, …, 8 is one of 8 signatures we identified, such that s1 equals the number of specific SNVs caused by signature 1 in the sample, and ∑sk equals the total number of SNVs in the sample. Let c = 1, 2, …, 96 represent each of the 96 possible trinucleotide mutation types. Each of the k signatures mutates each of these 96 trinucleotide mutation types c with a probability Pc,k (ranging from 0 to 1.0) where the sum of the probabilities for a given signature across all 96 trinucleotide mutation types is 1.0. The probability that a mutation of interest m (at trinucleotide mutation type c) was caused by a specific signature i is calculated as shown in Eq. 1:

| 1 |

GRIN analysis

The genomic random interval (GRIN) method18 was used to evaluate the statistical significance for the prevalence of SNVs, heterozygous deletions, fusion breakpoints, copy-neutral loss-of-heterozygosity, and amplification in each gene. For each gene, a p-value for each of these genomic alterations was computed. Also, for each gene, an overall p-value was computed by finding the minimum p-value across the five lesion types and comparing it to the beta distribution corresponding to the distribution of the minimum of five id uniform (0,1) realizations. For each set of p-values (one for each lesion type and the overall p-value), a robust method80 was used to compute false discovery rate estimates, which are reported with the symbol q. A total of 91 genes were identified as statistically significant with an overall q < 0.05. Additionally, MutSigCV81 analysis was used to determine driver status of SNVs and indels.

Super enhancer analysis in CD34+ cells

H3K27ac ChIP-seq data were downloaded from GEO accession GSE10457982. Raw reads were adapter-trimmed and subject to quality filtering using Trim Galore (v0.4.4), retaining reads with a quality score >20. Reads were mapped to the human genome (GRCh37) using BWA (v0.7.12)58, converted to bam format, and duplicate reads were marked using biobambam2 (v2.0.87)83 and removed using samtools (v1.10)68. H3K27ac peaks were called using macs2 (v2.1.1)84 in BEDPE mode with a p-value cutoff of 1 × 10−5. ROSE was run using the de-duplicated H3K27ac and input bam files and the macs2 peak file with default parameters. For additional visualization of the chromatin landscape in human CD34 + cells, three additional datasets were included in IGV snapshots. The CTCF bigwig file was downloaded from GEO accession GSE104579. The “CD34 + H3K27ac (Roadmap)” wiggle file was downloaded from GEO accession GSM77288585 and converted to bigwig. CD34+ ATAC-seq data were downloaded from GEO accession GSE7491286 and all biological replicates for CD34+ samples were merged into a single bedGraph file and converted to bigwig format for visualization. All RNA-seq tracks are normalized read coverage.

Statistical methods

The Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney non-parametric test, two-tailed, was used to compare means of quantitative variables across two experimental groups or diagnostic groups. The Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the frequency of complex karyotype between patients with and without TP53 mutations. Survival analysis of cause-specific death was performed with a Fine-Gray model87 that accounts for different causes of death as competing events and adjusts for hematopoietic stem cell transplant as a time-dependent outcome predictor variable.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

We thank all the patients and their families at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital (SJCRH) for their contribution of biological specimens used in this study. We also thank the Biorepository, the Flow Cytometry and Cell Sorting Core, and the Hartwell Center for Bioinformatics and Biotechnology at SJCRH for their essential services. Julie Justice in the Anatomic Pathology lab established the immunohistochemistry for MECOM. J.R.S. is supported by the NHLBI (1K08HL150282-01) and Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation Young Investigator Award. This work was funded by the American Lebanese and Syrian Associated Charities of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital and grants from the US National Institutes of Health (P30 CA021765, Cancer Center Support Grant; R01 HL144653 to J.M.K.). J.M.K. holds a Career Award for Medical Scientists from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund. Support was also provided by the Edward P. Evans Foundation (J.M.K). This research content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author contributions

J.R.S., J.M., J.K., S.W.B., L.M., X.M., and J.M.K. prepared the manuscript. J.R.S., T.W., R.H., J.K., T.G., X.M., and J.M.K. were responsible for experimental design and analysis. T.W. prepared DNA and RNA from all patient samples. J.M., M.P.W., J.R.M., X.C., G.S., G.W., Y.L., J.E., S.N, and J.Z. were responsible for bioinformatic data analysis. L.M. performed the super-enhancer analysis of CD34+ cells. K.E.N., M.F.W., J.L.M., J.K., J.R.S., T.G., and J.M.K. analyzed germline variants and determined their likely pathogenicity. S.W.B. performed and analyzed the mutational signatures present in the tMN cohort. J.R.S., J.K., and C.B. assembled all clinical data for the tMN cohort. P.K. performed MECOM immunohistochemistry. S.P. and H.W were responsible for all statistical analyses. C.G.M. and J.E.R. assisted with data analysis and acquisition of patient cases.

Data availability

The genomic data generated in this study have been deposited in the European Genome-Phenome Archive (EGA), which is hosted by the European Bioinformatics Institute (EBI), under accession EGAS00001004850 and through St. Jude Cloud [https://pecan.stjude.cloud/permalink/tMN]. All other remaining data are available within the article and supplementary files or available from the authors upon request. Other publicly available datasets used for CD34+ cell super-enhancer analysis are deposited in Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO): H3K27ac and CTCF ChIP-seq data are available under accession number GSE104579, CD34 + H3K27ac Roadmap ChIP-seq data are available under accession number GSM772885, and CD34+ ATAC-seq data are available under accession number GSE74912.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Tomas Radivoyevitch, Goro Sashida and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Jason R. Schwartz, Jing Ma, Jennifer Kamens.

Contributor Information

Tanja Gruber, Email: tagruber@stanford.edu.

Xiaotu Ma, Email: xiaotu.Ma@stjude.org.

Jeffery M. Klco, Email: jeffery.klco@stjude.org

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-021-21255-8.

References

- 1.Tsurusawa M, et al. Therapy-related myelodysplastic syndrome in childhood: a retrospective study of 36 patients in Japan. Leuk. Res. 2005;29:625–632. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2004.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown CA, Youlden DR, Aitken JF, Moore AS. Therapy-related acute myeloid leukemia following treatment for cancer in childhood: a population-based registry study. Pediatr. Blood Cancer. 2018;65:e27410. doi: 10.1002/pbc.27410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Imamura T, et al. Nationwide survey of therapy-related leukemia in childhood in Japan. Int. J. Hematol. 2018;108:91–97. doi: 10.1007/s12185-018-2439-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aguilera DG, et al. Pediatric therapy-related myelodysplastic syndrome/acute myeloid leukemia: the MD Anderson Cancer Center experience. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2009;31:803–811. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3181ba43dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong TN, et al. Role of TP53 mutations in the origin and evolution of therapy-related acute myeloid leukaemia. Nature. 2015;518:552–555. doi: 10.1038/nature13968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berger G, et al. Early detection and evolution of preleukemic clones in therapy-related myeloid neoplasms following autologous SCT. Blood. 2018;131:1846–1857. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-09-805879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gibson CJ, et al. Clonal hematopoiesis associated with adverse outcomes after autologous stem-cell transplantation for lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017;35:1598–1605. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.71.6712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Renneville A, et al. Genetic analysis of therapy-related myeloid neoplasms occurring after intensive treatment for acute promyelocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 2018;32:2066–2069. doi: 10.1038/s41375-018-0137-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ganser A, Heuser M. Therapy-related myeloid neoplasms. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2017;24:152–158. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0000000000000316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barnard DR, Woods WG. Treatment-related myelodysplastic syndrome/acute myeloid leukemia in survivors of childhood cancer–an update. Leuk. Lymphoma. 2005;46:651–663. doi: 10.1080/10428190500051042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pui CH, et al. Epipodophyllotoxin-related acute myeloid leukemia: a study of 35 cases. Leukemia. 1995;9:1990–1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pui CH, et al. Acute myeloid leukemia in children treated with epipodophyllotoxins for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 1991;325:1682–1687. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199112123252402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Winick NJ, et al. Secondary acute myeloid leukemia in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated with etoposide. J. Clin. Oncol. 1993;11:209–217. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.2.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rodriguez-Galindo C, et al. Hematologic abnormalities and acute myeloid leukemia in children and adolescents administered intensified chemotherapy for the Ewing sarcoma family of tumors. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2000;22:321–329. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200007000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blanco JG, et al. Molecular emergence of acute myeloid leukemia during treatment for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:10338–10343. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181199898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwartz JR, et al. The genomic landscape of pediatric myelodysplastic syndromes. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:1557. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01590-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Faber ZJ, et al. The genomic landscape of core-binding factor acute myeloid leukemias. Nat. Genet. 2016;48:1551–1556. doi: 10.1038/ng.3709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pounds S, et al. A genomic random interval model for statistical analysis of genomic lesion data. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:2088–2095. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang J, et al. Germline mutations in predisposition genes in pediatric cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;373:2336–2346. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1508054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parsons DW, et al. Diagnostic yield of clinical tumor and germline whole-exome sequencing for children with solid tumors. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:616–624. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.5699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ripperger T, et al. Childhood cancer predisposition syndromes-A concise review and recommendations by the Cancer Predisposition Working Group of the Society for Pediatric Oncology and Hematology. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2017;173:1017–1037. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.38142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mody RJ, et al. Integrative clinical sequencing in the management of refractory or relapsed cancer in youth. JAMA. 2015;314:913–925. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.10080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsu JI, et al. PPM1D mutations drive clonal hematopoiesis in response to cytotoxic chemotherapy. Cell Stem Cell. 2018;23:700–713 e6. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2018.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kahn JD, et al. PPM1D-truncating mutations confer resistance to chemotherapy and sensitivity to PPM1D inhibition in hematopoietic cells. Blood. 2018;132:1095–1105. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-05-850339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwartz JR, et al. Germline SAMD9 mutation in siblings with monosomy 7 and myelodysplastic syndrome. Leukemia. 2017;31:1827–1830. doi: 10.1038/leu.2017.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wong JC, et al. Germline SAMD9 and SAMD9L mutations are associated with extensive genetic evolution and diverse hematologic outcomes. JCI Insight. 2018;3:e121086. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.121086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wlodarski MW, et al. Prevalence, clinical characteristics, and prognosis of GATA2-related myelodysplastic syndromes in children and adolescents. Blood. 2016;127:1387–1397. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-09-669937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li B, et al. Therapy-induced mutations drive the genomic landscape of relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2020;135:41–55. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019002220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alexandrov LB, et al. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature. 2013;500:415–421. doi: 10.1038/nature12477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alexandrov LB, et al. Clock-like mutational processes in human somatic cells. Nat. Genet. 2015;47:1402–1407. doi: 10.1038/ng.3441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Waanders E, et al. Mutational landscape and patterns of clonal evolution in relapsed pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood Cancer Discov. 2020;1:96–111. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.BCD-19-0041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gough SM, Slape CI, Aplan PD. NUP98 gene fusions and hematopoietic malignancies: common themes and new biologic insights. Blood. 2011;118:6247–6257. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-07-328880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stengel A, et al. Detection of recurrent and of novel fusion transcripts in myeloid malignancies by targeted RNA sequencing. Leukemia. 2018;32:1229–1238. doi: 10.1038/s41375-017-0002-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rubin CM, et al. t(3;21)(q26;q22): a recurring chromosomal abnormality in therapy-related myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 1990;76:2594–2598. doi: 10.1182/blood.V76.12.2594.2594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hinai AA, Valk PJ. Review: aberrant EVI1 expression in acute myeloid leukaemia. Br. J. Haematol. 2016;172:870–878. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ho PA, et al. High EVI1 expression is associated with MLL rearrangements and predicts decreased survival in paediatric acute myeloid leukaemia: a report from the children’s oncology group. Br. J. Haematol. 2013;162:670–677. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Balgobind BV, et al. EVI1 overexpression in distinct subtypes of pediatric acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2010;24:942–949. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li S, et al. Myelodysplastic syndrome/acute myeloid leukemia with t(3;21)(q26.2;q22) is commonly a therapy-related disease associated with poor outcome. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2012;138:146–152. doi: 10.1309/AJCPZRRL2DGC2ODA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ottema S, et al. Atypical 3q26/MECOM rearrangements genocopy inv(3)/t(3;3) in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2020;136:224–234. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019003701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eguchi-Ishimae M, Eguchi M, Ohyashiki K, Yamagata T, Mitani K. Enhanced expression of the EVI1 gene in NUP98/HOXA-expressing leukemia cells. Int. J. Hematol. 2009;89:253–256. doi: 10.1007/s12185-009-0267-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Burillo-Sanz S, et al. NUP98-HOXA9 bearing therapy-related myeloid neoplasm involves myeloid-committed cell and induces HOXA5, EVI1, FLT3, and MEIS1 expression. Int. J. Lab. Hematol. 2016;38:64–71. doi: 10.1111/ijlh.12435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takeda A, Goolsby C, Yaseen NR. NUP98-HOXA9 induces long-term proliferation and blocks differentiation of primary human CD34+ hematopoietic cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:6628–6637. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stumpo DJ, et al. Targeted disruption of Zfp36l2, encoding a CCCH tandem zinc finger RNA-binding protein, results in defective hematopoiesis. Blood. 2009;114:2401–2410. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-04-214619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barbouti A, et al. A novel gene, MSI2, encoding a putative RNA-binding protein is recurrently rearranged at disease progression of chronic myeloid leukemia and forms a fusion gene with HOXA9 as a result of the cryptic t(7;17)(p15;q23) Cancer Res. 2003;63:1202–1206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saleki R, et al. A novel TTC40-MSI2 fusion in de novo acute myeloid leukemia with an unbalanced 10;17 translocation. Leuk. Lymphoma. 2015;56:1137–1139. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2014.947611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aly RM, Ghazy HF. Prognostic significance of MSI2 predicts unfavorable outcome in adult B-acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Int J. Lab. Hematol. 2015;37:272–278. doi: 10.1111/ijlh.12284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Duggimpudi S, et al. Transcriptome-wide analysis uncovers the targets of the RNA-binding protein MSI2 and effects of MSI2’s RNA-binding activity on IL-6 signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2018;293:15359–15369. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.002243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Consortium EP. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature. 2012;489:57–74. doi: 10.1038/nature11247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Davis CA, et al. The encyclopedia of DNA elements (ENCODE): data portal update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D794–D801. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu Y, et al. Discovery of regulatory noncoding variants in individual cancer genomes by using cis-X. Nat. Genet. 2020;52:811–818. doi: 10.1038/s41588-020-0659-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lewen M, et al. Pediatric chronic myeloid leukemia with inv(3)(q21q26.2) and T lymphoblastic transformation: a case report. Biomark. Res. 2016;4:14. doi: 10.1186/s40364-016-0069-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ma X, et al. Analysis of error profiles in deep next-generation sequencing data. Genome Biol. 2019;20:50. doi: 10.1186/s13059-019-1659-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Arber DA, et al. The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood. 2016;127:2391–2405. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-03-643544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Klco JM, et al. Genomic impact of transient low-dose decitabine treatment on primary AML cells. Blood. 2013;121:1633–1643. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-09-459313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang J, et al. The genetic basis of early T-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nature. 2012;481:157–163. doi: 10.1038/nature10725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang J, et al. A novel retinoblastoma therapy from genomic and epigenetic analyses. Nature. 2012;481:329–334. doi: 10.1038/nature10733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rusch M, et al. Clinical cancer genomic profiling by three-platform sequencing of whole genome, whole exome and transcriptome. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:3962. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06485-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:589–595. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Edmonson MN, et al. Bambino: a variant detector and alignment viewer for next-generation sequencing data in the SAM/BAM format. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:865–866. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang J, et al. CREST maps somatic structural variation in cancer genomes with base-pair resolution. Nat. Methods. 2011;8:652–654. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wu G, et al. The genomic landscape of diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma and pediatric non-brainstem high-grade glioma. Nat. Genet. 2014;46:444–450. doi: 10.1038/ng.2938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tian L, et al. CICERO: a versatile method for detecting complex and diverse driver fusions using cancer RNA sequencing data. Genome Biol. 2020;21:126. doi: 10.1186/s13059-020-02043-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Iyer MK, Chinnaiyan AM, Maher CA. ChimeraScan: a tool for identifying chimeric transcription in sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:2903–2904. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Morgan M., Pagès H., Obenchain V. & N, H. Binary alignment (BAM), FASTA, variant call (BCF), and tabix file import. 1.30.0 edn (2020).

- 66.Koboldt DC, et al. VarScan 2: somatic mutation and copy number alteration discovery in cancer by exome sequencing. Genome Res. 2012;22:568–576. doi: 10.1101/gr.129684.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chen X, et al. CONSERTING: integrating copy-number analysis with structural-variation detection. Nat. Methods. 2015;12:527–530. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li H, et al. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Olshen AB, Venkatraman ES, Lucito R, Wigler M. Circular binary segmentation for the analysis of array-based DNA copy number data. Biostatistics. 2004;5:557–572. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxh008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Seshan, V. & A, O. DNAcopy: DNA copy number data analysis. R package version 1.52.0 edn (2017).

- 71.Ioannidis NM, et al. REVEL: an ensemble method for predicting the pathogenicity of rare missense variants. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2016;99:877–885. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhang MY, et al. Genomic analysis of bone marrow failure and myelodysplastic syndromes reveals phenotypic and diagnostic complexity. Haematologica. 2015;100:42–48. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2014.113456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Keel SB, et al. Genetic features of myelodysplastic syndrome and aplastic anemia in pediatric and young adult patients. Haematologica. 2016;101:1343–1350. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2016.149476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cancer Genome Atlas Research, N. Genomic and epigenomic landscapes of adult de novo acute myeloid leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;368:2059–2074. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Topka S, et al. Germline ETV6 mutations confer susceptibility to acute lymphoblastic leukemia and thrombocytopenia. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1005262. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Richards S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015;17:405–424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Alexandrov LB, et al. The repertoire of mutational signatures in human cancer. Nature. 2020;578:94–101. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-1943-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Alexandrov LB, Nik-Zainal S, Wedge DC, Campbell PJ, Stratton MR. Deciphering signatures of mutational processes operative in human cancer. Cell Rep. 2013;3:246–259. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Morganella S, et al. The topography of mutational processes in breast cancer genomes. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:11383. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pounds S, Cheng C. Robust estimation of the false discovery rate. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:1979–1987. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lawrence MS, et al. Mutational heterogeneity in cancer and the search for new cancer-associated genes. Nature. 2013;499:214–218. doi: 10.1038/nature12213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zhang X, et al. Large DNA methylation nadirs anchor chromatin loops maintaining hematopoietic stem cell identity. Mol. Cell. 2020;78:506–521 e6. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tischler G, Leonard S. biobambam: tools for read pair collation based algorithms on BAM files. Source Code Biol. Med. 2014;9:13. doi: 10.1186/1751-0473-9-13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhang Y, et al. Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS) Genome Biol. 2008;9:R137. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-9-r137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kundaje A, et al. Integrative analysis of 111 reference human epigenomes. Nature. 2015;518:317–330. doi: 10.1038/nature14248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Corces MR, et al. Lineage-specific and single-cell chromatin accessibility charts human hematopoiesis and leukemia evolution. Nat. Genet. 2016;48:1193–1203. doi: 10.1038/ng.3646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1999;94:496–509. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1999.10474144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

The genomic data generated in this study have been deposited in the European Genome-Phenome Archive (EGA), which is hosted by the European Bioinformatics Institute (EBI), under accession EGAS00001004850 and through St. Jude Cloud [https://pecan.stjude.cloud/permalink/tMN]. All other remaining data are available within the article and supplementary files or available from the authors upon request. Other publicly available datasets used for CD34+ cell super-enhancer analysis are deposited in Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO): H3K27ac and CTCF ChIP-seq data are available under accession number GSE104579, CD34 + H3K27ac Roadmap ChIP-seq data are available under accession number GSM772885, and CD34+ ATAC-seq data are available under accession number GSE74912.