Abstract

Background

Most U.S. states have legalized cannabis for medical and/or recreational use. In a 6-month prospective observational study, we examined changes in adult cannabis use patterns and health perceptions following broadened legalization of cannabis use from medical to recreational purposes in California.

Methods

Respondents were part of Stanford University’s WELL for Life registry, an online adult cohort concentrated in Northern California. Surveys were administered online in the 10 days prior to state legalization of recreational use (1/1/18) and 1-month (2/1/18–2/15/18) and 6-months (7/1/2018–7/15/18) following the change in state policy. Online surveys assessed self-reported past 30-day cannabis use, exposure to others’ cannabis use, and health perceptions of cannabis use. Logistic regression models and generalized estimating equations (GEE) examined associations between participant characteristics and cannabis use pre- to 1-month and 6-months post-legalization.

Results

The sample (N = 429, 51% female, 55% non-Hispanic White, age mean = 56 ± 14.6) voted 58% in favor of state legalization of recreational cannabis use, with 26% opposed, and 16% abstained. Cannabis use in the past 30-days significantly increased from pre-legalization (17%) to 1-month post-legalization (21%; odds ratio (OR) = 1.28, p-value (p) = .01) and stayed elevated over pre-legalization levels at 6-months post-legalization (20%; OR = 1.28, p = .01). Exposure to others’ cannabis use in the past 30 days did not change significantly over time: 41% pre-legalization, 44% 1-month post-legalization (OR = 1.18, p = .11), and 42% 6-months post-legalization (OR = 1.08, p = .61). Perceptions of health benefits of cannabis use increased from pre-legalization to 6-months post-legalization (OR = 1.19, p = .02). Younger adults, those with fewer years of education, and those reporting histories of depression were more likely to report recent cannabis use pre- and post-legalization. Other mental illness was associated with cannabis use at post-legalization only. In a multivariate GEE adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics and diagnoses, favoring legalization and the interaction of time and positive health perceptions were associated with a greater likelihood of using cannabis.

Conclusions

Legalized recreational cannabis use was associated with greater self-reported past 30-day use post-legalization, and with more-positive health perceptions of cannabis use. Future research is needed to examine longer-term perceptions and behavioral patterns following legalization of recreational cannabis use, especially among those with mental illness.

Keywords: Cannabis, Legalization, Marijuana, Perceptions

Background

In the United States, a majority of states have legalized the use of cannabis for some purposes, and California has been a forerunner in cannabis legalization. California was the first state to legalize medical cannabis use in 1996. To date, 35 states (plus the District of Columbia, Guam, and Puerto Rico) have legalized medical cannabis; 15 of these 35 (plus the District of Columbia and Guam) have also legalized adult recreational cannabis, and another 13 states permit the use of products with low-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC, cannabis’s primary psychoactive ingredient) for medical purposes [1].

Modes of cannabis use include smoking, vaping, and as an edible. Cannabis when smoked may be wrapped in paper (i.e., a joint) or placed within a hollowed-out cigar (i.e., a blunt). In 2018, modes of recent cannabis use among young adults (18–25 years old) in California were reported as 81% smoking (i.e., joint, bong, pipe); 47% vaping; 43% blunt use; and 35% eating/drinking; 78% reported more than one method [2].

Potential mental health harms of cannabis use include increased risk of developing schizophrenia and other psychoses, with heavier cannabis use associated with greater risk [3]. Depression, anxiety, and suicidal thoughts also have been linked to cannabis use [4]. Whether the associations are causal is unknown. Smoking cannabis can affect lung health, with regular use associated with chronic bronchitis [3]. Smoking cannabis during pregnancy is associated with low birthweight; studies of adverse effects of prenatal cannabis use on offspring behavior and cognitive development have been equivocal [5]. Studies of brain structural measures and cannabis use in youth and young adults also have produced mixed results [6].

To characterize the evidence on the health benefits of cannabis use, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine published a comprehensive in-depth review of 10,000 studies [3]. The report found strong evidence from randomized control trials to support the conclusions that cannabis or its constituents (i.e., cannabinoids) are effective for treating chronic pain; as antiemetics in the treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting; and for improving patient-reported multiple sclerosis spasticity symptoms. With regards to mental health, other research has found an anxiolytic-like effect of cannabidiol (CBD) in patients with social anxiety disorder [7]. There also is moderate evidence for cannabinoids, mainly nabiximols, in improving short-term sleep outcomes in those with chronic medical conditions (e.g., fibromyalgia) [8]. Few studies have examined cannabis’s effects on well-being, a construct related to quality of life, and findings have been mixed [9, 10].

Since 1990, there has been an increasing trend in favor of legalizing cannabis in the United States. The Pew Research Center reported that 59% of Americans favor legalizing cannabis for medical and recreational use, while another 32% support cannabis use for medical purposes only; only 8% opposed legalizing cannabis [11]. Since 2002, adult use of cannabis has been increasing. In 2019, 31.6 million Americans reported cannabis use in the past 30 days, with prevalence of 23% among adults aged 18-to-25 and 10.2% among adults 26 years and older [12]. Data from the 2018 California Health Interview Survey showed that among adults 18 years and older, 33% reported cannabis use within the past month [13].

In California, on November 8, 2016, voters passed Prop 64, the Adult Use of Marijuana Act, supporting the legalization of recreational cannabis use for adults 21 years or older. Prop 64 proposed to create a system to regulate the cannabis market and impose taxes on the retail sale and cultivation of cannabis; and allowed for use in a private home or at a business licensed for on-site consumption, and prohibited use while driving and in public areas including federal areas such as parks, as it is illegal under federal law [14]. On January 1, 2018, California was authorized to begin issuing licenses to operate recreational cannabis businesses, legalizing sales from licensed retail outlets and the purchasing of cannabis for recreational use [15].

States that legalized recreational cannabis use had a higher prevalence of cannabis use and greater use of products such as cannabis edibles, drinks, and high potency concentrate than in those that had not [16]. Among the first four states that legalized cannabis for recreational purposes (Colorado, Washington, Alaska, and Oregon), there were increases in frequent cannabis use (defined as use 20 days or more in the past month) and cannabis use disorder among adults aged 26 and older following recreational cannabis legalization [17]. A recent California study found no increase in cannabis use after legalization of recreational cannabis; however, the study sample was restricted to young adults aged 18–24 who used tobacco, so the findings may not generalize to the broader population [18]. Beliefs on the health benefits of cannabis (i.e., for pain management, relief from stress) was found to be higher in states that had legalized cannabis for recreational use [19]. With expanding legalization and increases in cannabis use, examining patterns of cannabis use and the factors that might drive cannabis use trends over time is needed.

With California’s legalization of recreational cannabis use, we sought to characterize, from pre- to post-policy implementation, adults’ use patterns, exposure to others’ cannabis use, and perceptions of the benefits or harms of cannabis use to physical and mental health and well-being. We hypothesized an increase in adult cannabis use and exposure to others’ use as well as more positive health perceptions of cannabis use over time.

Methods

Study design

California’s broadening of cannabis legalization from medical-only to also include adult recreational use was effective January 1, 2018. In the 10 days prior to the date of state legalization of recreational use (12/21/17–12/31/17), respondents were recruited online from Stanford University’s WELL for Life registry, an online adult cohort concentrated in Northern California, with the mission to accelerate the science to enhance health and well-being. Respondents gave informed consent and were re-assessed 1 month (2/1/18–2/15/18) and 6 months (7/1/18–7/15/18) following the change in state policy. All research activities were approved by Stanford’s Institutional Review Board.

Measures

All measures were completed online with REDCap [20].

Demographic characteristics

Respondents self-reported their gender, age, race/ethnicity, years of education, employment status (employed, home-maker, student, disabled, temporarily laid off, unemployed, retired, other), and marital status (married, living with a partner or significant other, divorced, separated, widowed, single). Gender was coded for analyses as male/trans male and female. Race/ethnicity was coded for analyses as non-Hispanic White and other.

Support for legalizing recreational cannabis use

Policy support was assessed at pre-legalization as “Did you vote in favor or opposition to California Proposition 64 to legalize recreational use of marijuana in the state for persons aged 21 or older?” with response options of “vote in favor”, “vote in opposition”, or “did not vote.”

Cannabis use and exposure to Other’s use

Self-reported cannabis use, mode(s) of use during the past 30 days (i.e., smoked, vaporized, edible, in a blunt) and most recent exposure to others’ cannabis use (today, yesterday, last 3 to 7 days [this week], last 8 to 14 days [last week], last 15 to 30 days [past month], more than a month ago but within the past year, more than a year ago, never) were assessed. Use and exposure variables were dichotomized to reflect past 30-day cannabis use and past 30-day exposure to others’ cannabis use (yes: within the past 30 days, no: greater than 30 days) for analyses.

Health perceptions

Perceptions of cannabis’ effects were assessed with three questions with the same stem: “How harmful or beneficial do you think marijuana is to … physical health / mental health / well-being?” with response options ranging from extremely harmful (− 4) to neither harmful nor beneficial (0) to extremely beneficial (+ 4), with values and anchors of less degree of harm/benefit in between. Participants could also mark “don’t know” and “refused.” “Don’t know” was coded as a 0 and “refused” was coded as missing. The three perception items were averaged to produce a single scale score for analyses with Cronbach alpha = 0.91.

Medical characteristics

Participants self-reported pain for the past 2 weeks (yes/no) and lifetime diagnoses of cancer, depression, and other mental illness (yes/no).

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were run on sample baseline characteristics. Surveys were completed by N = 429 at pre-legalization, N = 323 at 1-month post-legalization, and N = 225 at 6-months post-legalization, with attrition of 24.7% at 1-month and 47.6% at 6-months post-legalization. Compared to those who missed one or two surveys (n = 204, 47.6%), respondents who completed all three surveys (n = 225, 52.4%) were less likely to be employed (odds ratio (OR) = 0.55, p-value (p) = .02). None of the other measured variables predicted attrition (all p-values > 0.06). Employment was included as a covariate in all longitudinal models.

Past 30-day cannabis use and exposure to others’ cannabis use were calculated as frequencies and then also modeled over time using generalized estimating equations (GEE) [21], which included all available data, modeled missing responses, and adjusted for variables related to attrition. GEE models also were run to examine cannabis-related health perceptions over time. Linear and binary GEE models were used for continuous and binary outcome variables, respectively.

To examine predictors of cannabis use, initial univariate logistic regression models were run to identify respondent characteristics associated with cannabis use at each time point. Next, a series of multivariate GEE models were run. The initial GEE model controlled for variables related to attrition. The second GEE model added demographic variables significantly associated with cannabis use at any time point at p < .05. The final GEE model added in vote, health perceptions, and 2-way interaction terms for age and health perceptions with time. Interaction terms with p < .10 were dropped from the model. All GEE models used an unstructured correlation structure. Analyses were conducted using SPSS version 25 [22].

Results

Sample description

The sample (N = 429) had a mean age of 56 years (standard deviation (SD) = 14.6, range: 23 to 86); 51.3% identified as female; 55.5% identified as non-Hispanic White/Caucasian; 41.0% were married/cohabitating, 8.2% were divorced/separated, 11.4% were never married, and 2.3% were widowed; 46.6% were employed, 13.5% were retired, and 6.8% were other (e.g., student, unemployed). Years of education ranged from 12 to 20 with a mean of 17.3 years (SD = 2.0). Over half (58.0%) of the sample reported voting in favor of state legalization of recreational cannabis use, 25.9% opposed, and 16.1% abstained. See Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics (N = 429)

| Variables | N | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 83 | 19.3% |

| Female | 220 | 51.3% |

| Trans Male | 1 | 0.2% |

| Missing | 125 | 29.1% |

| Age, Mean (SD) | 56.0 | (14.6) |

| Missing | 146 | 34.0% |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 238 | 55.5% |

| Hispanic | 18 | 4.2% |

| Other | 82 | 19.1% |

| Missing | 91 | 21.2% |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 156 | 36.4% |

| Living with significant other | 20 | 4.7% |

| Divorced | 32 | 7.5% |

| Separated | 3 | 0.7% |

| Widowed | 10 | 2.3% |

| Single | 49 | 11.4% |

| Missing | 159 | 37.1% |

| Employment status | ||

| Currently employed | 200 | 46.6% |

| Homemaker | 8 | 1.9% |

| Student | 3 | 0.7% |

| Disabled | 2 | 0.5% |

| Unemployed | 6 | 1.4% |

| Retired | 58 | 13.5% |

| Other | 10 | 2.3% |

| Missing | 142 | 33.1% |

| Years of education, Mean (SD) | 17.3 | (2.0) |

| Missing | 161 | 37.5% |

Cannabis use, exposure to others’ cannabis use, and mode of use

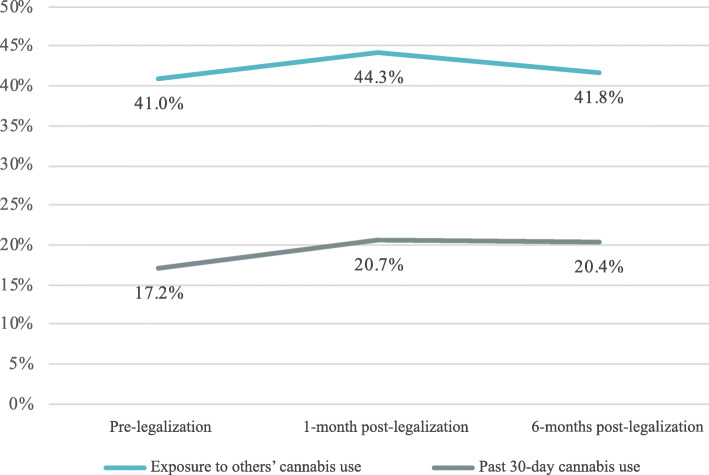

Figure 1 shows the prevalence of reported past 30-day cannabis use over time, which was 17.2% at pre-legalization, 20.7% at 1-month post-legalization, and 20.4% at 6-months post-legalization. In GEE models including all available data, modeling missing responses, and adjusting for employment status, cannabis use significantly increased from pre-legalization to 1-month post-legalization (OR = 1.28, p = .01) and stayed significantly higher over pre-legalization levels at 6-months post-legalization (OR = 1.28, p = .01). Among those reporting past 30-day cannabis use, the mean number of days used was 11 (SD = 9.4) at pre-legalization, 12 (SD = 10.4) at 1-month post-legalization, and 13 (SD = 11) at 6-months post-legalization.

Fig. 1.

Cannabis use and exposure at pre- and 1-month post- and 6-months post-legalization. Exposure to other’s cannabis use increased from pre- to post-legalization but was not statistically significant. Past 30-day cannabis use significantly increased from pre-legalization to 1-month post-legalization and stayed significantly higher over pre-legalization levels at 6-months post-legalization

Figure 1 also shows the prevalence of past 30-day exposure to others’ cannabis use, which was 41.0% at pre-legalization, 44.3% at 1-month post-legalization, and 41.8% at 6-months post-legalization. In GEE models including all available data, modeling missing responses, and adjusting for employment status, exposure to others’ cannabis use in the past 30 days did not change significantly from pre-legalization to 1-month post-legalization (OR = 1.18, p = .11) or 6-months post-legalization (OR = 1.08, p = .61).

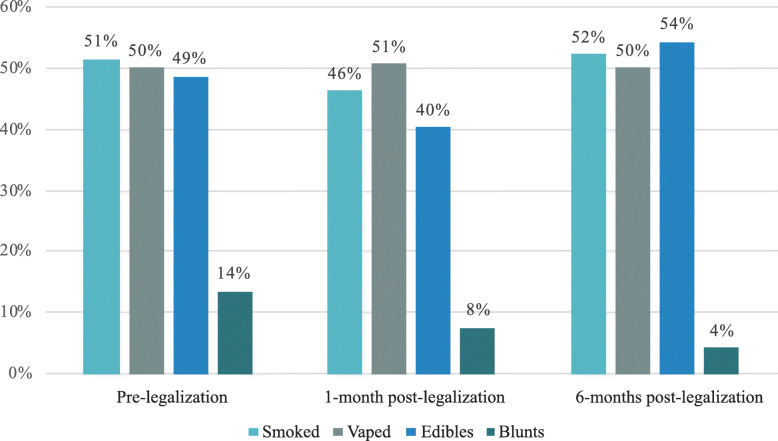

Figure 2 shows the modes of cannabis use over time among recent users, with multiple response options possible. Most frequent modes of cannabis use were smoked, vaped, and edibles. Blunts were reported by a minority and declined over time from 13.5% at pre-legalization to 4.3% at 6-months post-legalization.

Fig. 2.

Reported modes of cannabis use over time among recent users. Most frequent modes of cannabis use were smoked, vaped, and edibles. Blunts were reported by a minority and declined over time

Health perceptions of cannabis over time

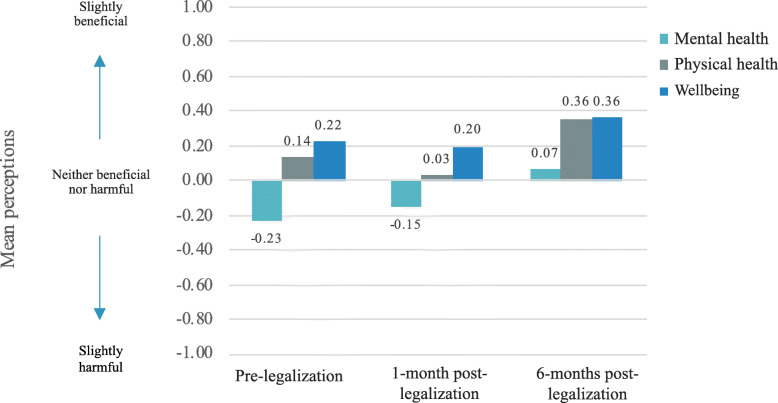

Figure 3 shows change over time in the sample’s mean health perceptions of cannabis. Mental health perceptions of cannabis use increased over time from slightly harmful at pre-legalization to slightly beneficial at 6-months post-legalization. Physical health perceptions of cannabis were positive overtime but decreased from pre-legalization to 1-month post-legalization, and then increased to levels above pre-legalization at 6-months-post-legalization. Well-being perceptions of cannabis use had the highest means overtime and remained similar at pre-legalization and 1-month post-legalization and then increased at 6-months post-legalization.

Fig. 3.

Mean perceptions over time. Perceptions of mental health, physical health, and wellbeing of cannabis use increased over time. Possible responses for each scale ranged from extremely harmful (− 4) to neither harmful nor beneficial (0) to extremely beneficial (+ 4), with values and anchors of less degree of harm/benefit in between

Estimated marginal means for the combined health perceptions of cannabis use item, with a potential range of − 4 to + 4, were 0.039 at pre-legalization, 0.005 at 1-month post-legalization, and 0.231 at 6-months post-legalization. That is, they were near zero at pre and 1-month post-legalization (i.e., neutral) and showed more positive health perceptions by 6-months post-legalization. In GEE models including all available data, modeling missing responses, and adjusting for employment status, cannabis use was perceived to be more beneficial at 6-months post-legalization than pre-legalization (OR = 1.19, p = .02), with no significant difference between pre-legalization and 1-month post-legalization (OR = 0.95, p = .40).

Associations with cannabis use over time

Table 2 summarizes univariate associations between respondent characteristics and past 30-day cannabis use. At pre-legalization, correlates of recent cannabis use were younger age (OR = 0.98, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.96, 0.999); less years of education (OR = 0.82, 95% CI: 0.70, 0.95); depression diagnosis (OR = 2.70, 95% CI: 1.38, 5.31); voting in favor of legalizing recreational cannabis use (OR = 8.74, 95% CI: 3.08, 24.81) or abstaining from voting (OR = 5.34, 95% CI: 1.62, 17.60) relative to those who opposed; and perceiving greater health benefits of cannabis (OR = 2.19, 95% CI: 1.80, 2.67).

Table 2.

Univariate tests of associations with cannabis use at pre-legalization and 1- and 6-months post-legalization

| Cannabis use | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-legalization | 1-month post-legalization | 6-months post-legalization | ||||||||||

| Variables | n | OR | 95% CI | p | n | OR | 95% CI | p | n | OR | 95% CI | p |

| Female | 278 | 1.11 | 0.56, 2.22 | .77 | 269 | 0.90 | 0.48, 1.71 | .76 | 183 | 0.83 | 0.38, 1.79 | .63 |

| Age (years) | 260 | 0.98 | 0.96, 0.999 | .04 | 251 | 0.97 | 0.95, 0.99 | .009 | 167 | 0.96 | 0.94, 0.99 | .001 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 309 | 0.56 | 0.31, 1.02 | .06 | 301 | 0.74 | 0.41, 1.31 | .30 | 201 | 0.77 | 0.38, 1.56 | .47 |

| Education (years) | 245 | 0.82 | 0.70, 0.95 | .01 | 251 | 0.87 | 0.75, 0.999 | .05 | 169 | 0.85 | 0.72, 1.01 | .07 |

| Married/cohabitating | 247 | 0.56 | 0.29, 1.07 | .08 | 253 | 0.74 | 0.40, 1.37 | .34 | 169 | 0.54 | 0.26, 1.12 | .10 |

| Currently employed | 262 | 1.18 | 0.59, 2.39 | .64 | 268 | 0.82 | 0.44, 1.53 | .54 | 181 | 0.78 | 0.38, 1.62 | .51 |

| Medical condition | ||||||||||||

| Pain | 243 | 0.90 | 0.43, 1.86 | .78 | 249 | 0.69 | 0.34, 1.40 | .30 | 166 | 0.56 | 0.24, 1.33 | .19 |

| Cancer | 244 | 0.80 | 0.31, 2.05 | .65 | 250 | 0.94 | 0.40, 2.18 | .88 | 167 | 0.34 | 0.10, 1.21 | .10 |

| Depression | 242 | 2.70 | 1.38, 5.31 | .004 | 248 | 2.29 | 1.20, 4.36 | .01 | 166 | 3.00 | 1.40, 6.46 | .005 |

| Other mental illness | 242 | 1.99 | 0.85, 4.67 | .12 | 248 | 1.56 | 0.64, 3.78 | .33 | 166 | 3.38 | 1.21, 9.49 | .02 |

| Vote | 391 | 302 | 202 | |||||||||

| Oppose (ref) | ||||||||||||

| Abstain | 5.34 | 1.62, 17.60 | <.01 | 2.33 | 0.73, 7.45 | .15 | 4.09 | 0.94, 17.83 | .06 | |||

| Favor | 8.74 | 3.08, 24.81 | <.001 | 5.10 | 2.09, 12.45 | <.001 | 6.74 | 1.97, 23.04 | .002 | |||

| Health Perceptionsa | 390 | 2.19 | 1.80, 2.67 | <.001 | 300 | 2.34 | 1.86, 2.93 | <.001 | 201 | 2.03 | 1.59, 2.59 | <.001 |

a Health perceptions at pre-legalization

As seen at pre-legalization, a depression diagnosis had a 2- to 3-fold greater likelihood of cannabis use at 1- and 6-months post-legalization. Age and voting in favor of legalizing recreational cannabis use also remained associated with a greater likelihood of cannabis use at both post-legalization assessments. Less years of education was associated with a greater likelihood of cannabis use at 1-month but not 6-months post-legalization. Lastly, at 6-months post-legalization, other mental illness had a 3-fold greater likelihood of cannabis use.

In GEE analyses modeling cannabis use over time and adjusting for age, years of education, employment status, depression, and other mental illness, initial vote in favor of legalizing cannabis for recreational use (OR = 4.62, p < .01) and positive health perceptions (OR = 1.38, p < .001) remained significant correlates. There was a significant interaction effect of time at 6-months post-legalization and positive health perceptions (OR = 1.22, p = .01), suggesting that from pre-legalization to 6-months post-legalization, there was a greater increase in cannabis use among those with beneficial perceptions than those with harmful health perceptions of cannabis use. The interaction between health perceptions at 1-month post-legalization was not significant (OR = 1.08, p = .27) (Table 3). The interaction between time and age, was not significant (p > .19), and therefore was dropped from the model.

Table 3.

Generalized estimating equation (GEE) models predicting cannabis use

| Model 1 (N = 282) | Model 2 (N = 252) | Model 3 (N = 252) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | AOR | 95% CI | p | AOR | 95% CI | p | AOR | 95% CI | p |

| Time | |||||||||

| Pre-legalization (ref) | |||||||||

| 1-month post-legalization | 1.28 | 1.07, 1.53 | 0.01 | 1.23 | 1.02, 1.48 | 0.03 | 1.27 | 0.99, 1.63 | 0.06 |

| 6-months post-legalization | 1.28 | 1.06, 1.55 | 0.01 | 1.18 | 0.98, 1.41 | 0.08 | 0.94 | 0.71, 1.23 | 0.63 |

| Currently employeda | 0.91 | 0.51, 1.64 | 0.76 | 0.53 | 0.25,1.13 | 0.10 | 0.52 | 0.25, 1.09 | 0.09 |

| Age | 0.97 | 0.94, 0.99 | < 0.01 | 0.96 | 0.94, 0.98 | 0.01 | |||

| Years of education | 0.88 | 0.75, 1.02 | 0.08 | 0.86 | 0.73, 1.01 | 0.06 | |||

| Depression | 2.39 | 1.22, 4.68 | 0.01 | 1.90 | 0.92, 3.92 | 0.08 | |||

| Other mental illness | 1.08 | 0.42, 2.76 | 0.88 | 1.55 | 0.58, 4.15 | 0.38 | |||

| Vote | |||||||||

| Oppose (ref) | |||||||||

| Abstain | 1.57 | 0.41, 6.02 | 0.51 | ||||||

| Favor | 4.62 | 1.55, 13.8 | < 0.01 | ||||||

| Health Perceptions | 1.38 | 1.16, 1.64 | <.001 | ||||||

| Time x health perceptions | |||||||||

| Pre-legalization x health perceptions (ref) | |||||||||

| 1-month post-legalization x health perceptions | 1.08 | 0.95, 1.23 | 0.27 | ||||||

| 6-months post-legalization x health perceptions | 1.22 | 1.04, 1.42 | 0.01 | ||||||

Note. Adjusted odds ratios (AOR), confidence interval (CI), reference group (ref)

The age x time interaction was not significant and therefore dropped from the model

a All models adjusted for employment status, due to its association with attrition

Discussion

In this prospective observational study on cannabis policy changes in California, legalized recreational cannabis use was associated with greater self-reported past 30-day use one-month post-legalization, and in the univariate model, remained significantly higher at 6-months post-legalization. Compared to California state data, our study sample had a lower frequency of past 30-day cannabis use [13]. Likely related, the sample had more harmful perceptions of cannabis use: 43% of respondents at baseline and 42% at 1-month post-legalization perceived cannabis use to be harmful, whereas United States data from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration estimated 12% of young adults 18 to 25 years old and 29% of adults 26 years or older perceived great risk from smoking cannabis monthly [23].

Surprisingly, exposure to others’ use of cannabis did not change from pre- to post-legalization of recreational cannabis use in our study timeframe; however, it is possible that exposure to cannabis smoke may have increased earlier among our study population. A California Department of Public Health survey found that the rate of cannabis exposure in 2016 among adults aged 18 to 64 years was 21.5%, and by 2018 had doubled to 40%, which is similar to our findings on cannabis exposure [24]. In late-2016, Prop 64 was voted on and approved by voters of California and could explain the increase of secondhand cannabis exposure from 2016 to 2018.

Significant correlates of cannabis use at all time points included depression diagnosis, while having an other mental illness diagnosis was significantly associated with cannabis use only 6-months post-legalization. A recent study found that from 2005 to 2017, the prevalence of cannabis use among people in the United States with depression was increasing and that those with depression experienced a rapid decrease in perception of risk of cannabis use [25]. While not tested in our study, it is possible those with depression or other mental illness experienced decreasing perceptions of risk of cannabis use. Despite the growing evidence of cannabis use as an effective treatment in chronic pain [3, 26] and its use in mitigating side effects of cancer therapies, our study showed that those with pain and those with a history of cancer were not significantly more likely to use cannabis.

Among our California study sample of adults between the ages of 23 to 86 with a mean age of 56 years, we found younger age associated with cannabis use pre- and post-legalization. These findings are consistent with previous national studies on adults in the United States where cannabis use decreased with increasing age [27].

By 6-months post-legalization, perceived health benefits of cannabis use significantly increased, and in the multivariate model, health perceptions were associated with cannabis use over time. Notably, perceptions of health benefits of cannabis use for mental health showed the largest increase. The literature suggests potential anxiolytic effects of CBD [7], but also points to the association of mental health harms with high-potency cannabis use [28]. Though our sample had an overall positive perception of cannabis use in benefiting physical health and wellbeing, there was no significant association between cannabis use with pain or cancer, common conditions for which cannabis has been used to treat. Mass marketing and health promotions from cannabis dispensaries also may have contributed to the increase in perceived health benefits of cannabis. Since the legalization of recreational cannabis in California, which includes the selling of cannabis, dispensary ads and mass marketing campaigns promoting uses of cannabis have proliferated [29, 30]. Endorsements from social media influencers and celebrities, may also be adding to overall positive perception of cannabis use. As a response to the mass marketing, Los Angeles and San Diego counties have proposed restrictions on where cannabis ads and billboards can be placed [31]. Much is to be learned on whether these restrictions will impact perceptions and use. To ensure health harms are not ignored, public health interventions such as educational programs and health communications are needed to increase awareness.

Study limitations include that the data were self-reported by a relatively small convenience sample, and thus may not be generalizable to other populations. The sample was more non-Hispanic White (55.5% vs 36.5%) than the general population in California [32]; however, a similar percentage of Californians voted in favor for Proposition 64 (58% vs 57.1%) [33]. Another limitation is the high level of missing demographic data and high attrition rate. Rather than remove respondents who did not complete all the surveys and conduct a complete-case analysis that could lead to less power and biased results, we used GEE analyses, which is useful in dealing with missing data and does not require imputation [34]. Missingness was not associated with cannabis use, and therefore consistent with the assumption that outcome data were missing completely at random [35]. To account for missing data, we did adjust for employment, which was associated with attrition, in all models.

If perceptions of the health benefits of cannabis use increase over time and become more widespread (i.e., normative), cannabis use may increase further. Cannabis dependency may also increase, which has been linked to other substance use, depression and low satisfaction with life [36]. We found the number of days of cannabis use increased on average from 11 days pre-legalization to 13 days post-legalization, which may reflect movement toward cannabis abuse and dependency. A study in California found a link between the density of cannabis dispensaries and neighborhood ecology on cannabis abuse and dependency before the legalization of recreational cannabis [37]. Of interest is whether the density of dispensaries in California overall, and particularly in economically disadvantaged neighborhoods, occurred post-legalization and if cannabis use and dependency has risen disproportionately in some areas.

Further research examining the long-term effects of legalized recreational cannabis on health outcomes, perceptions, and use, especially among young people and those with depression and other mental illness, is warranted. Studies should also focus on the characteristics of cannabis used such as potency, as well as the environmental and social impacts. Public health communications and evidence-based interventions on the potential health benefits and consequences of cannabis use are needed.

Conclusions

The current study provides novel insight into changes in reported cannabis use and health perceptions over time in relation to state policy change. Policy change in recreational cannabis use was associated with greater perceptions of health benefits of cannabis use over time. In a fully adjusted longitudinal model, factors related to cannabis use other than time were younger age, voting in favor of cannabis use, and positive health perceptions. Further research on the long-term patterns of health perceptions, exposures, and behaviors following the legalization of adult recreational cannabis use is warranted to inform future public health policies, interventions and educational initiatives.

Acknowledgements

This work was made possible thanks to Dr. Ann Hsing and the WELL for Life team at Stanford University School of Medicine and the study participants.

Abbreviations

- THC

Tetrahydrocannabinol

- CBD

Cannabidiol

- GEE

Generalized estimating eqs.

- OR

Odds ratio

- SD

Standard deviation

- CI

Confidence interval

Authors’ contributions

KG: Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing- original draft, Writing- review & editing, Visualization. SJW: Project administration, Resources, Writing- review & editing. NJA: Data curation, Resources, Writing- review & editing. EF: Writing- review & editing. JJP: Conceptualization, Writing- review & editing, Visualization, Supervision. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Initial foundational funding for the Stanford Wellness Living laboratory (WELL) was provided by Amway via an unrestricted gift through the Nutrilite Health Institute Wellness Fund to Stanford University. Dr. Frank’s work is supported by the Canada Research Chair Program at the University of British Columbia, as well as research funding from the Annenberg Physician Training Program in Addiction Medicine. This work was also supported by a postdoctoral fellowship training grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [grant T32HL007034]. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study can be requested from Dr. Ann Hsing, the PI of the Stanford WELL for Life Study, at annhsing@stanford.edu.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All research activities were approved by Stanford’s Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was obtained from all respondents.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

JPP has provided consultation to pharmaceutical and technology companies that make medications and other treatments for quitting tobacco smoking and has served as an expert witness in lawsuits against the tobacco companies. EF is on the Stanford Prevention Research Center’s WELL Advisory Board. The other authors declare they have no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.National Conference of State Legislatures . State medical marijuana laws. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meng Y, Ponce N. The changing landscape: tobacco and marijuana use among young adults in California UCLA Center for health policy Reseach. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine . The health effects of cannabis and cannabinoids: the current state of evidence and recommendations for research. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Marijuana and public health. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huizink A. Prenatal cannabis exposure and infant outcomes: overview of studies. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2014;52:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2013.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scott JC, Rosen AFG, Moore TM, Roalf DR, Satterthwaite TD, Calkins ME, et al. Cannabis use in youth is associated with limited alterations in brain structure. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2019;44(8):1362–1369. doi: 10.1038/s41386-019-0347-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schier ARM, Ribeiro NPO, Hallak JEC, Crippa JAS, Nardi AE, Zuardi AW. Cannabidiol, a Cannabis sativa constituent, as an anxiolytic drug. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2012;34:104–110. doi: 10.1016/S1516-4446(12)70057-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whiting PF, Wolff RF, Deshpande S, Di Nisio M, Duffy S, Hernandez AV, et al. Cannabinoids for medical use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;313(24):2456–2473. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.6358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmid K, Schönlebe J, Drexler H, Mueck-Weymann M. The effects of cannabis on heart rate variability and well-being in young men. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2010;43(04):147–150. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1248314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jetly R, Heber A, Fraser G, Boisvert D. The efficacy of nabilone, a synthetic cannabinoid, in the treatment of PTSD-associated nightmares: a preliminary randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled cross-over design study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;51:585–588. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daniller A. Two-thirds of Americans support marijuana legalization. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2019 National Survey on drug use and health. Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 13.UCLA Center for Health Policy Research. Adults who have ever tried marijuana or hashish. AskCHIS 2018. http://ask.chis.ucla.edu. Accessed 11 Feb 2020.

- 14.California General Election Voter Information Guide. 2018. https://vig.cdn.sos.ca.gov/2018/general/pdf/complete-vig.pdf. Accessed 1 Jul 2019.

- 15.California Legislative Information . SB-94 cannabis: medicinal and adult use. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goodman S, Wadsworth E, Leos-Toro C, Hammond D. Prevalence and forms of cannabis use in legal vs illegal recreational cannabis markets. Int J Drug Policy. 2020;76:102658. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.102658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cerdá M, Mauro C, Hamilton A, Levy NS, Santaella-Tenorio J, Hasin D, et al. Association between recreational marijuana legalization in the United States and changes in marijuana use and cannabis use disorder from 2008 to 2016. JAMA Psychiat. 2020;77(2):165–171. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.3254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doran N, Strong D, Myers MG, Correa JB, Tully L. Post-legalization changes in marijuana use in a sample of young California adults. Addict Behav. 2021;115:106782. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steigerwald S, Cohen BE, Vali M, Hasin D, Cerda M, Keyhani S. Differences in opinions about marijuana use and prevalence of use by state legalization status. J Addict Med. 2020;14(4):337–344. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liang K-Y, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73(1):13–22. doi: 10.1093/biomet/73.1.13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corp IBM. IBM SPSS statistics for windows. Armonk: IBM Corp; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2017 National Survey on drug use and health. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vuong TD, Zhang X, Roeseler A. California tobacco facts and figures 2019. Sacramento: California Department of Public Health; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pacek LR, Weinberger AH, Zhu J, Goodwin RD. Rapid increase in the prevalence of cannabis use among people with depression in the United States, 2005-17: the role of differentially changing risk perceptions. Addiction. 2020;115(5):935–943. doi: 10.1111/add.14883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takakuwa KM, Hergenrather JY, Shofer FS, Schears RM. The impact of medical cannabis on intermittent and chronic opioid users with Back pain: how cannabis diminished prescription opioid usage. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2020;5(3):263–270. doi: 10.1089/can.2019.0039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dai H, Richter KP. A National Survey of marijuana use among US adults with medical conditions, 2016–2017. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(9):e1911936-e. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.11936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hines LA, Freeman TP, Gage SH, Zammit S, Hickman M, Cannon M, et al. Association of High-Potency Cannabis use with mental health and substance use in adolescence. JAMA Psychiat. 2020;77(10):1044–1051. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.D’Amico EJ, Rodriguez A, Tucker JS, Pedersen ER, Shih RA. Planting the seed for marijuana use: changes in exposure to medical marijuana advertising and subsequent adolescent marijuana use, cognitions, and consequences over seven years. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;188:385–391. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.May P. ‘The Apple Store of Weed’: Marijuana marketing is often far from mellow. The Mercury News. 2019. May 22, 2019.

- 31.Garrick D. San Diego advances ban on marijuana billboards near schools, parks and youth centers. Los Angeles Times. 2019. October 5, 2019.

- 32.United States Census Bureau. QuickFacts California. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/CA/PST040219. Accessed 15 July 2020.

- 33.Statement of Vote: November 8 2016 General Election. https://elections.cdn.sos.ca.gov/sov/2016-general/sov/2016-complete-sov.pdf. Accessed 2 Apr 2020.

- 34.Twisk J, de Vente W. Attrition in longitudinal studies: how to deal with missing data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55(4):329–337. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(01)00476-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schneider KL, Hedeker D, Bailey KC, Cook JW, Spring B. A comment on analyzing addictive behaviors over time. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12(4):445–448. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Looby A, Earleywine M. Negative consequences associated with dependence in daily cannabis users. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2007;2(1):3. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-2-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mair C, Freisthler B, Ponicki WR, Gaidus A. The impacts of marijuana dispensary density and neighborhood ecology on marijuana abuse and dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;154:111–116. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study can be requested from Dr. Ann Hsing, the PI of the Stanford WELL for Life Study, at annhsing@stanford.edu.