Abstract

The present study was designed to ascertain the extent to which dimensions of acculturation would differ across personal identity statuses in a sample of 2,411 first- and second-generation, immigrant, college-attending emerging adults. Participants from 30 colleges and universities around the United States completed measures of personal identity processes, as well as of heritage and American cultural practices, values, and identifications. Cluster-analytic procedures were used to classify participants into personal identity statuses based on the personal identity processes. Results indicated that, across ethnic groups, individuals in the achieved and searching moratorium statuses reported the greatest endorsement of heritage and American cultural practices, values, and identifications; and individuals in the carefree diffusion status reported the lowest endorsement of all the cultural variables under study. These results are discussed in terms of the convergence between personal identity and cultural identity processes.

Keywords: identity status, acculturation, immigrant, personal identity, cultural identity

Two of the most commonly studied dimensions of identity are personal identity and cultural identity (Schwartz, Zamboanga, & Weisskirch, 2008). Identity can be defined as the individual’s cognitive, behavioral, and affective repertoire regarding who she or he is (Vignoles, Schwartz, & Luyckx, 2011), to which groups he or she belongs, and behaviors enacted as a result of these thoughts and beliefs. Drawing from this definition, personal identity refers to the set of goals, values, and beliefs that one develops in areas such as career, relationships, and religious beliefs. Cultural identity refers to the ethnically or culturally based practices, values, and identifications that one maintains. Furthermore, whereas personal identity is salient for most young people, who must decide what they believe and what to do with their lives (Côté & Levine, 2002), cultural identity is most salient for members of immigrant and minority groups (Phinney & Ong, 2007) such as immigrants, children of immigrants, and individuals from visible-minority groups, who must straddle multiple cultural backgrounds (Syed & Azmitia, 2009). Immigrant families, then, represent unique opportunities for studying the confluence and shifting of these two dimensions of identity, which may be changing in tandem (Schwartz, Montgomery, & Briones, 2006). For example, experiencing discrimination or having novel experiences with other members of one’s ethnic group may serve to ignite the processes of personal and cultural identity development (cf. the “encounter” phase of nigrescence theory; Worrell, Cross, & Vandiver, 2001).

When examining identity, acculturation may be viewed as a cultural identity process (Schwartz, Unger, Zamboanga, & Szapocznik, 2010). Acculturation refers to orientation toward one’s cultural heritage and toward the receiving society in which one resides. For first-generation immigrants, acculturation refers to a process of cultural adaptation following migration to a new country (Smith, Bond, & Kağıtçbaşı, 2006). First-generation immigrants are challenged with selectively acquiring the practices, values, and identifications of their new homelands while selectively retaining those of their cultural heritage. For second-generation immigrants, acculturation refers to balancing one’s cultural heritage with influences of the receiving society (Portes & Rumbaut, 2006). Because most second- and later-generation immigrants have lived the majority (or all) of their lives in the receiving country, they know about their family’s countries of origin primarily through stories, travel, interactions with heritage-cultural individuals, and other brief or second-hand accounts. So for many first-generation immigrants, the heritage culture is a primary influence and the receiving culture must be balanced with the heritage culture. In contrast, for many second-generation immigrants, family and community members are the primary source of heritage-cultural influences (Schwartz, Unger et al., 2010), which must be balanced with the receiving culture in which the person has lived for all (or most) of his or her life. Accordingly, the present study is guided by two theoretical models—Luyckx and colleagues’ (Luyckx, Goossens, Soenens, & Beyers, 2006; Luyckx, Schwartz, et al., 2008) personal identity commitment formation and evaluation perspective, and Schwartz, Unger, et al.’s (2010) multidimensional conception of acculturation. Both personal identity commitments and acculturation represent dimensions of identity (Schwartz et al., 2008).

Acculturation as an Identity Process

According to Schwartz, Unger et al.’s (2010) multidimensional conceptualization of acculturation, acculturative processes occur within a number of domains, including practices, values, and identifications. Heritage and receiving cultural influences are assumed to operate somewhat independently within each of these domains. Cultural practices include behaviors such as speaking the languages of one’s heritage and receiving cultural contexts, associating with heritage and receiving-culture friends and romantic partners, and accessing heritage and receiving-culture media. Cultural values include the relative priority that individuals assign to their own personal needs and desires and to those of important others, such as family and friends. Across ethnic groups, cultural values can include (a) individualism and independence, which refer to feeling separate from others and prioritizing one’s own desires and needs ahead of those of others; and (b) collectivism and interdependence, which refer to feeling connected to others and prioritizing their needs over one’s own. Because the majority of contemporary immigrants to the United States and other primarily individualist Western nations come from collectivist-oriented countries or regions in Asia, Africa, Latin America, the Caribbean, and the Middle East (Steiner, 2009; Van de Vijver & Phalet, 2004), the United States may provide a strong contrast against many immigrant-sending countries in terms of cultural values. Lastly, cultural identifications refer to the extent to which individuals feel a sense of belonging and attachment to the United States and to their cultures of origin. These three domains of acculturation are overlapping but distinct (Abraído-Lanza, Armbrister, Flórez, & Aguirre, 2006). For example, one can learn English out of necessity but not hold individualistic values or identify as American.

Following Cross’s (see Worrell et al., 2001) concept of encounters within the racial identity literature, acculturation may stimulate (or represent) personal identity work in first- and second-generation immigrants through contact with members of the heritage-cultural community and receiving-society individuals. However, given the somewhat different cultural identity challenges facing first-versus second-generation immigrants, the confluence between personal and cultural identity may differ across generations. We address this issue in the present study, and we review personal identity in the next subsection.

Personal Identity: The Identity-Status Model and Its Extensions

Identity statuses represent individuals’ typical modes of handling personal life goals and decisions. Grounded in Erikson’s (1950) psychosocial stage theory, Marcia (1966) defined four identity statuses: (a) Achievement: individuals who have considered a number of possible life options and settled on one or more of these; (b) moratorium: people actively searching through potential alternatives; (c) foreclosure: adolescents and young adults who have internalized identity choices and commitments from significant others with little or no consideration of other possibilities; and (d) diffusion: people who have not systematically explored possible life options and do not hold firm commitments.

Luyckx and colleagues (Luyckx, Goossens, Soenens, & Beyers, 2006) extended Marcia’s identity-status model into a commitment formation and evaluation model. Using cluster-analytic methods on several Belgian samples of high school students, college students, and working emerging adults, Luyckx and colleagues (e.g., Luyckx, Duriez, Klimstra, & De Witte, 2010; Luyckx, Schwartz, et al., 2008; Luyckx, Goossens, Soenens, Beyers, & Vansteenkiste, 2005) redefined the identity-status model using five- rather than two-component dimensions. Exploration is divided into two distinct processes—exploration in breadth (sorting through multiple alternative choices) and exploration in depth (thinking and talking more about commitments that have already been enacted). Commitment is divided into two distinct processes—commitment making (choosing a set of goals, values, and beliefs to which to adhere) and identification with commitment (deepening one’s fidelity to a specific set of goals, values, and beliefs). A fifth process, ruminative exploration, refers to a counterproductive process of obsessing over the need to make identity-related choices and becoming “stuck” in the identity-development process.

Using these cluster-analytic procedures, Luyckx, Schwartz et al. (2008) and Schwartz, Beyers et al. (2011) found that the foreclosure, moratorium, and achievement statuses emerged in accordance with Marcia’s model. However, the moratorium status extracted by Schwartz, Beyers et al. (2011), using a large American college-student sample, was characterized by the presence of commitments—in contrast to Marcia’s moratorium status, yet was associated with elevated levels of psychological distress (see Kroger & Marcia, 2011, for a review). This status was thus relabeled as searching moratorium (see Meeus, van de Schoot, Keijsers, Schwartz, & Branje, 2010).

In addition, Luyckx and colleagues found two new statuses. First, the diffused status was subdivided into two separate statuses. Diffused diffusion represents Marcia’s original diffused status and refers to individuals who attempt to explore various options but do not systematically explore long enough to establish a firm set of commitments. Carefree diffusion refers to individuals who are not interested in engaging in identity work and are happy to remain uncommitted. They are generally uninterested in undertaking identity work and are at highest risk for antisocial and health-compromising behaviors, including fighting, rule breaking, dangerous drug use, unsafe sexual contact, and driving while intoxicated (Schwartz, Beyers, et al., 2011). Second, an undifferentiated status emerged, referring to individuals who scored near the sample mean on all of the identity processes and could not be categorized into any one status. The undifferentiated status has also emerged in earlier identity-status research (e.g., Bennion & Adams, 1986) and is generally the most common identity-status classification.

The Present Study

Given that cultural heritage is part of overall personal identity, it seems reasonable to propose that, for first- and second-generation immigrants, elements of one’s cultural heritage and/or culture of settlement can become a part of the individual’s personal identity. First, if variables indexing acculturation were to differ systematically across personal identity statuses, such consistency would affirm Schwartz et al.’s (2006, 2008, 2010a, 2010b) contention that acculturation is indeed an identity process. Second, if the patterns of identity-status differences were largely consistent across ethnicity and across immigrant generation, such a finding would suggest that acculturation, as an identity process, may also be characterized by a specific structure that cuts across ethnic groups and between first- and second-generation immigrants. Finally, the existence of an association between personal identity status and acculturation-related indices among first- and second-generation immigrants would suggest that each identity status may represent a characteristic way of addressing the challenges of acculturation. For example, the achieved status, which represents exploring options in breadth followed by making and identifying with commitments, might be associated with greater exploration of cultural options as well. Diffused and foreclosed individuals, on the other hand, might be expected to adopt a much less agentic— and more passive—approach to acculturation.

To investigate the associations between personal identity status and acculturation-related processes, we used a sample of first and second generation college students. Immigrant college students represent a rapidly increasing population, comprising approximately 25% of students on United States campuses (Schwartz, Waterman, et al., in press). Likewise, the university experience provides a context for identity development (Montgomery & Côté, 2003; Schwartz, Côté, & Arnett, 2005) with an array of options that may promote a diverse set of identity statuses. Our first hypothesis was that statuses characterized by highest levels of commitment—achievement and foreclosure—would be linked with the highest degrees of heritage-culture retention. Because foreclosure involves acceptance of parental values and ideals without exploration, such individuals might uncritically internalize their cultural heritage with few attachments to American culture. Achieved individuals, on the other hand, might be more likely to synthesize their heritage and American cultures into a combined and unique identity mosaic (cf. Huynh, Nguyen, & Benet-Martínez, 2011).

Second, we hypothesized that the statuses characterized by the highest levels of exploration—achievement and searching moratorium—would be associated with high degrees of heritage-culture retention and American-culture acquisition (i.e., biculturalism). We put forth this hypothesis assuming that (a) heritage-cultural influences offered by parents and other members of the heritage-cultural community and (b) American-cultural influences offered by peers, media influences, et cetera, would provide potential identity alternatives. Exploration, especially as defined within the identity-status model, often involves considering options other than those transmitted by parents (Grotevant, 1987), but it can also involve a deepening and reaffirming of prior commitments (Crocetti, Rubini, & Meeus, 2008; Luyckx, Schwartz, Goossens, Beyers, & Missotten, 2011). The agentic orientation that characterizes the moratorium and achieved statuses may be similar to the agency that underlies biculturalism. We did not advance a specific hypothesis for the undifferentiated status, given that it refers to individuals who are not typical of any of the original identity statuses. Moreover, with the relative recency of the demarcation between diffused and carefree diffusion, we did not advance a prediction regarding which variant of diffusion would be associated with lower degrees of heritage and American cultural orientations.

Method

Participants and Procedures

Data for this study were taken from a larger data collection involving emerging adults at 30 United States colleges and universities (Schwartz, Beyers, et al., 2011; Schwartz, Waterman, et al., 2011). Given the focus on acculturation-related variables, in the present study we included only those individuals who reported that both of their parents were born outside the United States. This sample comprised 2,411 participants (70% women; mean age 19.69 years, SD 1.63 years, range 18 to 25). Regarding ethnicity, 9.2% of participants were non-Hispanic White, 10.5% were non-Hispanic Black, 31.6% were Hispanic, 34.0% were East Asian, 11.1% were South Asian, and 3.5% were Middle Eastern. First-generation immigrants represented 68% of Whites, compared with 38% of Blacks, 34% of Hispanics, 37% of East Asians, 42% of South Asians, and 31% of Middle Easterners. International students were not included in the present sample.

Sites were selected to provide a diverse representation of regions of the United States, types of institutions, and ethnic backgrounds. Six sites were located in the Northeast, seven in the Southeast, seven in the Midwest, three in the Southwest, and seven in the West—representing 20 states in total. We received approval from the institutional review board at each participating site.

Participants were first directed to an online consent form. Participants who provided consent then logged in to the website using university name and student number, which were later replaced with code numbers to ensure confidentiality both for individual participants and for universities. Each participant received research credit. The survey was divided into six pages, and students could save their work and resume later. All measures were in English. Eighty-five percent of participants submitted all pages. Missing data were handled through the use of full-information maximum-likelihood estimation (Schlomer, Bauman, & Card, 2010).

Measures

Identity status.

The Dimensions of Identity Development Scale (DIDS; Luyckx, Schwartz et al., 2008) consists of five-item scales for each of the five identity dimensions proposed by Luyckx, Goossens, Soenens, and Beyers, (2006); Luyckx, Schwartz, et al., 2008): commitment making (α = .91; e.g., “I know what I want to do with my future”), identification with commitment (α = .93; e.g., “My future plans give me self-confidence”), exploration in breadth (α = .84; e.g., “I think a lot about the direction I want to take in my life”), exploration in depth (α = .81; e.g., “I think a lot about the future plans I have made”), and ruminative exploration (α = .85; e.g., “I keep wondering which direction my life has to take”). These reliability coefficients are comparable to those from the Belgian datasets. Studies by Luyckx, Goossens, Soenens, & Beyers, (2006); Luyckx, Schwartz, et al., (2008); Luyckx, Duriez, Klimstra, & De Witte, (2010) have demonstrated the factorial and construct validity of these subscales.

Acculturation-related variables.

We assessed heritage-cultural and American-cultural practices, values, and identifications. To measure cultural practices, we used the 32-item Stephenson (2000) Multigroup Acculturation Scale, consisting of 15 items (α = .85) indexing use of English, association with American friends and romantic partners, and engagement with American media; 17 items (α = .90) measure use of one’s heritage language, association with friends and romantic partners from one’s cultural group, and engagement with heritage-cultural media.

We indexed cultural values as individualism–collectivism and self-construal. Individualism and collectivism are subdivided into horizontal and vertical variants, resulting in three sets of cultural values: horizontal individualism–collectivism, vertical individualism–collectivism, and self-construal. Horizontal individualism refers to competing against (or otherwise feeling separate from) friends and coworkers. Vertical individualism refers to feeling separate from, and not required to defer to, parents or authority figures. Horizontal collectivism refers to feeling connected to, and responsible for the welfare of friends and coworkers. Vertical collectivism refers to having respect for hierarchical relationships, such as parent–child, teacher–student, or boss–employee.

Individualism and collectivism were assessed using corresponding 4-item scales developed by Triandis and Gelfand (1998): Horizontal individualism, α = .78 (sample item: “I’d rather depend on myself than on others”); vertical individualism, α = .77 (“Winning is everything”); horizontal collectivism, α = .74 (“I feel good when I collaborate with others”); and vertical collectivism, α = .74 (“It is my duty to take care of my family, even when I have to sacrifice what I want”). Triandis and Gelfand report results of analyses demonstrating the factorial and construct validity of these subscales.

Self-construal was measured using the 24-item Self-Construal Scale (Singelis, 1994). Twelve items measure independence (α = .74; sample item “I prefer to be direct and forthright in dealing with people I have just met”) and 12 assess interdependence (α = .77; “My happiness depends on the happiness of those around me”). An in-depth psychometric analysis of this measure (Guo, Schwartz, & McCabe, 2008) supported the factor structure proposed by Singelis (1994).

Versions of the Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure (MEIM; Phinney, 1992) were used to assess both heritage and United States cultural identifications. To assess heritage-culture identifications, we used the original version of the MEIM, which consists of 12 items (α = .90) that assess the extent to which one (a) has considered the subjective meaning of one’s ethnicity and (b) feels positively about one’s ethnic group. Sample items include “I think a lot about how my life will be affected by my ethnic group membership” and “I am happy that I am a member of the ethnic group I belong to.” Although the MEIM was originally designed to yield separate subscales for ethnic identity exploration and affirmation, Phinney and Ong (2007) have reviewed studies supporting a single-factor structure.

To assess American identity, we adapted the MEIM so that “the U.S.” was inserted into each item in place of “my ethnic group” (Schwartz et al., 2012). This adapted measure was highly internally consistent (α = .90). As an index of construct validity, United States identity scores were moderately and significantly correlated (r = .56, p < .001) with scores on United States cultural practices. Schwartz et al. (2012) found that the factor structure of the adapted MEIM items was consistent across ethnicity and immigrant generation.

Results

Plan of Analysis

Analyses consisted of five steps. First, we used cluster-analytic methods with the five personal identity dimensions as continuous input variables to test the hypothesis that the clusters from the Belgian datasets would emerge in the present data. We used cluster analysis, rather than latent-class analysis, because latent-class analysis assumes that the clustering variables are uncorrelated with one another (the identity dimensions are significantly intercorrelated; Ritchie et al., in press). Second, we examined the extent to which the identity-status cluster solution would relate to ethnicity, gender, and immigrant generation. Third, we compared continuous scores for the cultural processes across personal identity statuses to test the hypothesis that moratorium and achieved individuals would be bicultural, that foreclosed individuals would be most likely to retain their cultural heritage, and that diffused individuals would score lowest on all of the cultural variables. Fourth, we examined intraclass correlations to determine whether multilevel modeling (participants within universities) would be required. Finally, we used structural invariance testing to examine the extent to which the patterns of differences identified in the third step of analysis would be consistent across ethnicity and immigrant generation.

Creation of the Identity-Status Clusters

In the larger sample, to create identity-status categories and to classify participants into these categories, scores on each DIDS subscale were standardized according to their placement along the range of possible scores (Steinley & Brusco, 2008). We then split the sample randomly in half and conducted a two-step clustering procedure within each half sample (Gore, 2000). First, a hierarchical cluster analysis using Ward’s method with squared Euclidean distances (Steinley & Brusco, 2007) was conducted, requesting a six-cluster solution as previously found in several Belgian studies (e.g., Luyckx, Schwartz, et al., 2008; Luyckx, Seiffge-Krenke, et al., 2008). This six-cluster solution provided a significantly better fit to the data than did four-, five-, and seven-cluster solutions (see Schwartz, Beyers, et al., 2011, for statistical details). Second, to classify participants into identity statuses for the present sample, we then entered the cluster centers from the full sample (Schwartz, Beyers, et al., 2011) into a noniterative, k-means cluster analysis (Breckenridge, 2000) using only the cases included in the present sample. We compared the two solutions within each half sample using the Hubert-Arable Adjusted Rand Index (Steinley, 2004). Values for this index range from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating greater agreement between the two cluster solutions and underscoring the conclusion that the obtained clustering does not depend on the specific sample involved. Provided that the replicability of the cluster solution was high, we then used the clusters extracted from the full sample for the present study.

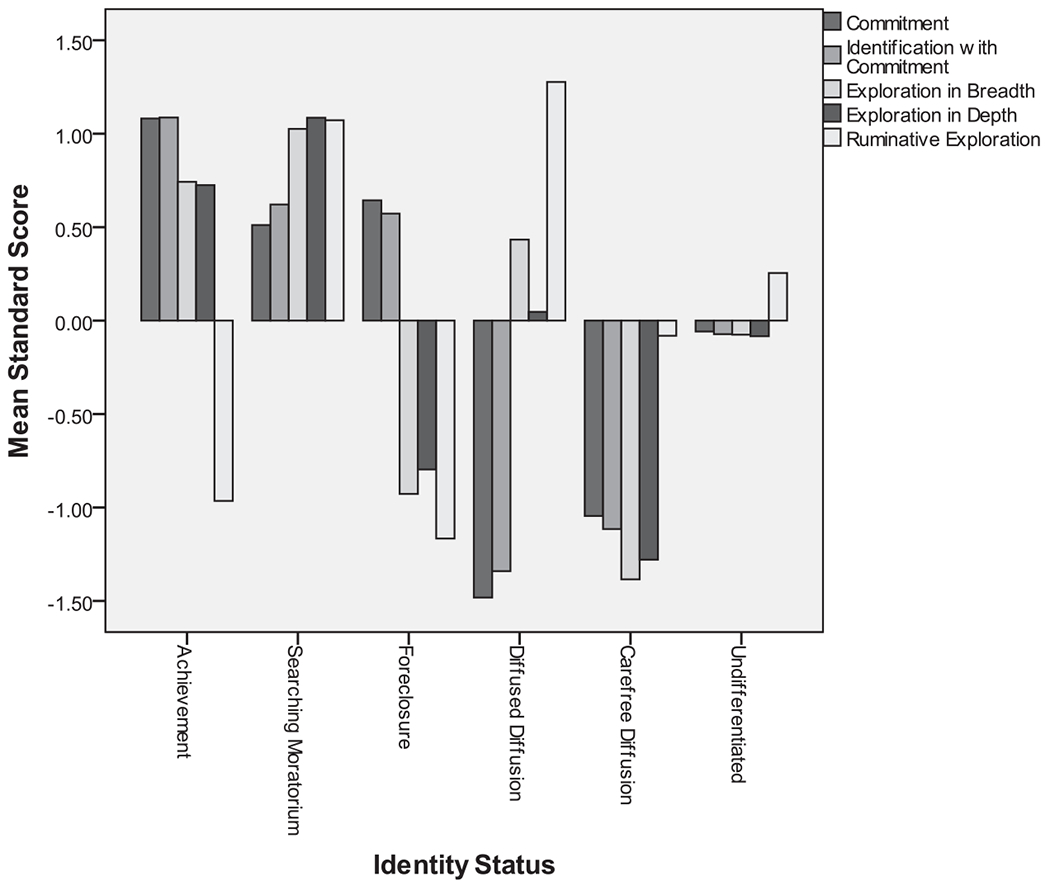

The cluster solution was highly reliable across randomly selected half samples (Hubert-Arable Adjusted Rand Index = .98). We therefore retained the cluster solution from the full sample. The six identity statuses were labeled Achievement (n = 321), Diffused Diffusion (n = 257), Carefree Diffusion (n = 444), Searching Moratorium (n = 345), Foreclosure (n = 304), and Undifferentiated (n = 740). The Achievement cluster was above the mean on exploration in breadth, exploration in depth, commitment making, and identification with commitment, but below the mean on ruminative exploration. The Diffused Diffusion cluster was below the mean on commitment making and identification with commitment and well above the mean on ruminative exploration. The Carefree Diffusion cluster was below the mean on all five identity processes. The Searching Moratorium cluster was approximately 1 SD above the mean on all three exploration dimensions, and somewhat elevated on commitment making and identification with commitment. The Foreclosed cluster was high on both commitment dimensions and low on all three exploration dimensions. The Undifferentiated cluster was very close to the sample mean on all five identity processes. The cluster solution is displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Identity-status cluster solution.

Identity Statuses by Ethnic Groups

As a descriptive analysis, we examined the distribution of identity statuses across the six ethnic groups, as well as across immigrant generation (first vs. second). The identity-status distribution differed significantly and moderately across ethnicity, χ2(25) = 106.18, p < .001, Cramér’s V = .09 (see Table 1). Hispanics were overrepresented in the achieved status, Middle Eastern participants in the undifferentiated status, and East and South Asians in the carefree diffusion status. Black and Middle Eastern participants were underrepresented in both diffusion statuses. The identity-status distribution did not differ significantly between first- and second-generation immigrants, χ2(5) = 7.59, p = .18, Cramér’s V = .06.

Table 1.

Number and Percentage of Participants in Each Identity Status by Ethnic Group

| Identity status | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnic group | Achievement | Undifferentiated | Foreclosed | Searching moratorium | Diffused diffusion | Carefree diffusion |

| White | 29 (13.2%) | 59 (26.9%) | 36 (16.4%) | 33 (15.1%) | 23 (10.5%) | 39 (17.8%) |

| Black | 33 (13.1%) | 86 (34.3%) | 38 (15.1%) | 40 (15.9%) | 17 (6.8%) | 37 (14.7%) |

| Hispanic | 141(18.7%) | 218 (28.9%) | 114 (15.1%) | 119 (15.8%) | 77 (10.2%) | 86 (11.4%) |

| East Asian | 76 (9.3%) | 259 (31.8%) | 81 (10.0%) | 100 (12.3%) | 95 (11.7%) | 203 (24.9%) |

| South Asian | 29 (10.9%) | 74 (27.8%) | 26 (9.8%) | 40 (15.0%) | 37 (13.9%) | 60 (22.6%) |

| Middle Eastern | 13 (15.5%) | 34 (40.5%) | 5 (6.0%) | 11 (13.1%) | 6 (7.1%) | 15 (7.9%) |

Examination of Intraclass Correlations

Because of the complex sampling method that we used, with participants nested within data-collection sites, the first step of analysis was to examine the intraclass correlations (ICC). ICC values indicate the percentage of variability in a given variable that is due to between-sites differences rather than to between-participants differences. Raudenbush and Bryk (2002) suggest that, in cases where the ICC is greater than about .05, multilevel nesting must be accounted for in the statistical analyses.

To obtain ICC values, we estimated unconditional multilevel models using Mplus release 5.0 (Muthén & Muthén, 2007). Unconditional models do not contain any predictor variables and are used only to ascertain the percentage of variability at the level of the individual case versus at the aggregate (site) level. ICC values for the cultural variables ranged from .016 to .219, with a mean of .085. As a result, we concluded that it was essential to control for the effects of multilevel nesting in our analyses.

Cultural Variables by Identity Status

Because we were interested only in controlling for multilevel nesting, and not explicitly in between-site differences, we used the sandwich covariance estimator (Kauermann & Carroll, 2001), which adjusts model parameters, standard errors, and fit indices for the effects of nesting, but does not explicitly model between-sites variability as part of the analysis. Multilevel models are estimated in regression form, so omnibus statistics (such as F and η2) are not available. However, pairwise differences between and among statuses on each dependent variable were estimated using the sandwich estimator, and using an alpha level of .001 to adjust for the number of comparisons conducted for each cultural variable.

We estimated a series of models to identify pairwise differences between statuses on each cultural variable. Within each model, one of the statuses was used as a reference group and compared with all of the other statuses on each dependent variable. Results are displayed in Table 2. Such an approach is analogous to pairwise comparisons in analysis of variance.

Table 2.

Mean Levels of Acculturation-Related Variables by Personal Identity Status

| Variable | Achievement | Searching moratorium |

Foreclosure | Diffused diffusion |

Carefree diffusion |

Undifferentiated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| American practices | 62.52a (7.65) | 62.73a (7.45) | 60.41b (7.42) | 59.66b (8.38) | 54.53c (10.44) | 59.24b (8.17) |

| Heritage practices | 60.11a (13.69) | 59.95a (14.09) | 55.88ab (13.31) | 53.42b (12.46) | 53.79b (13.64) | 57.19a (13.29) |

| Horizontal individualism | 17.34a (2.64) | 17.50a (2.53) | 16.51b (2.68) | 15.98b (2.75) | 14.33c (3.04) | 16.03b (2.53) |

| Vertical individualism | 13.03a (3.51) | 14.32b (3.59) | 11.84c (3.43) | 12.49ac (3.60) | 12.04c (2.90) | 12.76a (3.17) |

| Independence | 46.51a (6.42) | 46.81a (6.31) | 44.06b (6.50) | 41.82c (5.91) | 39.69c (6.68) | 43.08b (5.98) |

| Horizontal collectivism | 16.03a (2.71) | 16.23a (2.49) | 15.12b (2.74) | 15.14b (2.82) | 13.79c (2.85) | 14.94b (2.45) |

| Vertical collectivism | 16.21a (3.12) | 16.62a (2.76) | 15.26b (2.76) | 15.33b (2.90) | 13.86c (3.03) | 15.40b (2.67) |

| Interdependence | 44.38a (7.04) | 46.88b (6.68) | 42.18c (6.51) | 44.24a (5.65) | 41.40c (7.30) | 43.73a (6.14) |

| American identity | 46.64a (9.66) | 48.09a (9.20) | 43.20b (8.52) | 43.65b (9.27) | 38.67c (8.47) | 43.64b (7.88) |

| Ethnic identity | 47.04a (9.73) | 49.40a (8.58) | 43.78b (9.33) | 42.64b (9.31) | 40.19c (8.63) | 45.32a (8.29) |

Note. Within each row, means with the same subscript do not differ from one another at p < .001.

Lastly, given our interest in examining ethnic and immigrant-generation variations in patterns of identity-status differences in acculturation-related variables, we conducted invariance tests on the pairwise differences across ethnicity and across immigrant generation. We compared (a) a model with the magnitude of each pairwise comparison free to vary across ethnic groups or immigrant generations with (b) a model with the magnitude of each pairwise comparison constrained to be equal across ethnic groups or immigrant generations. The form of invariance that we examined here is therefore a combination of metric invariance (factor loading and path-coefficient equivalence) and scalar invariance (mean and intercept equivalence).

For comparisons across ethnicity and across immigrant generation, the unconstrained and constrained models were compared using differences in the two models’ χ2, comparative fit index (CFI), and nonnormed fit index (NNFI) values. The null hypothesis of invariance across ethnic groups or across immigrant generations would be rejected if two or more of the following three criteria were met: Δχ2 significant at p < .05 (Byrne, 2009), ΔCFI > .01 (Cheung & Rensvold, 2002), and ΔNNFI > .02 (Vandenberg & Lance, 2000). These invariance tests were therefore designed to ascertain the extent to which the magnitudes of pairwise differences were equivalent across ethnic groups and across immigrant generations.

The pairwise comparisons differed significantly across ethnic groups, Δχ2(250) = 402.62, p < .001; ΔCFI = .019; ΔNNFI = .044, and across immigrant generations, Δχ2(50) = 146.14, p < .001; ΔCFI = .005; ΔNNFI = .021. As a result, separately for ethnicity and for immigrant generation, we followed a procedure outlined by Byrne (2009) and constrained one comparison at a time (e.g., moratorium vs. achievement for American practices) to identify the sources of the variance. With regard to ethnicity, the lack of invariance was due to ethnic differences in the comparison between the achieved and carefree-diffused statuses with regard to heritage practices, American practices, and independent self-construal. For heritage practices, the difference between the achieved and carefree-diffused statuses was largest for Middle Eastern participants and smallest for East Asian participants. For American practices, this difference was largest for South Asian participants and smallest for Hispanic participants. For independent self-construal, this difference was largest for Black participants and smallest for Middle Eastern participants. No other sources of significant variance were identified among the 150 comparisons tested—suggesting that the three paths characterized by significant variance may have occurred by chance. None of the status comparisons were significantly different across immigrant generation. We therefore concluded that the identity-status differences in acculturation-related variables were largely consistent across ethnicity and across generation.

Discussion

The present study was designed to examine associations between personal identity-status and acculturation-related variables in first- and second-generation immigrant college students. The identity-status distribution that emerged is consistent with those obtained from college (Luyckx, Schwartz, et al., 2008) and noncollege (Luyckx, Seiffge-Krenke, et al., 2008) emerging adults. As was the case in the Belgian samples, the undifferentiated status represented approximately one third of the present sample, and the other five statuses each represented between 11% and 18% of the sample. Indeed, the undifferentiated status refers to individuals who score near the sample means on the various personal identity dimensions, and given that most of the scores in a normal distribution fall near the mean, the undifferentiated status would be expected to be well-represented (see Jones, Akers, & White, 1994, for further discussion). The undifferentiated status appears to represent individuals who exhibit characteristics of more than one status and could not be safely placed into one of the other statuses. It is noteworthy that the present study is one of the first to use the Luyckx, Schwartz, et al., (2008) identity-status model with a sample of first- and second-generation immigrants and found largely the same identity-status distribution as has been found in past work.

The present sample differed from the Belgian samples in two primary ways. First, although some of the Belgian samples (e.g., Luyckx et al., 2005) were comprised of college students, these samples were gathered at a single university. The present sample was gathered at 30 colleges and universities across the United States. Second, whereas the Belgian samples were primarily White and native-born, the present sample consisted exclusively of first and second-generation immigrants and more than 90% were ethnic minorities. The similarities between the identity-status distributions in the present sample and in the Belgian samples suggest that personal identity development in immigrant United States college students is characterized by the same identity processes and statuses as is personal identity development in other emerging-adult populations.

Across the various indices of acculturation, a consistent pattern of differences emerged across personal identity statuses. Individuals in the searching moratorium and achieved statuses scored highest, and those in carefree diffusion lowest, on nearly all acculturation-related variables. This suggests that acculturation is closely linked to personal identity exploration, which is a defining dimension of both achievement and searching moratorium. As immigrants explore potential personal identity alternatives, they are also likely to endorse both heritage and American cultural elements. It seems, therefore, that acculturation may be, at least in part, a process of exploration in which the individual is able to examine cultural choices (heritage, receiving, or both) to which she or he might commit.

Given the multiculturalism present in many areas in the United States, it is not surprising that immigrants are likely to encounter cultural identity elements as they search for personal goals, values, and beliefs. Alternatively, it is possible that the distinction between personal and cultural identity is artificial (cf. Usborne & Taylor, 2010), especially in today’s globalized world. Exploring personal identity might also mean exploring cultural identity, and vice versa, especially for individuals from immigrant and ethnic minority backgrounds. At an individual level, such a parallel between personal and cultural identity exploration may be similar to—and reliant upon—the exchange of ideas between and among cultures as a result of globalization and international migration (Arnett, 2002; Jensen, Arnett, & McKenzie, 2011).

Moreover, achievement is marked by strong commitments, and searching moratorium is marked by maintenance of at least some commitments that the person retains even as she or he evaluates new identity choices. Similar to personal identity formation, acculturation involves both considering potential cultural orientations and adopting one or more of these orientations. The concept of selective acculturation (Portes & Rumbaut, 2006) suggests that, at least to some extent, immigrants and their children can decide which elements of American culture to incorporate into their identities. The same may be true of the heritage culture. Immigrants and their children may decide to retain or not to retain specific components of their cultures of origin (Weinreich, 2009). The results suggest that selective acculturation may operate in a similar fashion as does personal identity development—that is, through processes of exploration and commitment. First- and second-generation immigrant students may respond to cultural and personal identity challenges in many of the same ways.

A contemporary and recurrent theme in the acculturation literature is that biculturalism is often the most favorable approach to acculturation (Coatsworth, Maldonado-Molina, Pantin, & Szapocznik, 2005; Sam & Berry, 2010). Within bidimensional models of acculturation, biculturalism represents high levels of both heritage and American cultural practices, values, and identifications (Castillo & Caver, 2009; Schwartz, Unger, et al., 2010). In the present results, individuals in the achieved status and those in searching moratorium reported the highest levels of both heritage and American cultural indices, and therefore, would likely be classified as bicultural. Because biculturalism represents an individualized and agentic orientation, individuals must select aspects of their heritage and receiving cultural streams and integrate them into a bicultural identity (Huynh et al., 2011). Similarly, moratorium and achievement represent sorting through potential life choices and selecting one or more to which to adhere. An agentic and creative approach to cultural identity is therefore linked with an agentic and creative approach to personal identity.

In contrast, individuals in carefree diffusion reported the lowest scores on all of the cultural identity indices. For immigrants who adopt a carefree-diffused approach, acculturation may represent a task to be avoided. Because it represents an identity transition, acculturation may be somewhat distressing and disequilibrating for some individuals (e.g., Kasinitz, Mollenkopf, Waters, & Holdaway, 2008; Suárez-Orozco, Suárez-Orozco, & Todorova, 2008). One of the hallmarks of carefree diffusion is a desire to avoid identity work by any means necessary (Luyckx, Goossens, Soenens, Beyers, & Vansteenkiste, 2005; Luyckx, Schwartz, et al., 2008; Schwartz, Beyers, et al., 2011). However, such an approach may come with costs. Immigrants who are not strongly attached to either their heritage or receiving cultures would fall into Berry’s (1980) marginalized category, which is equated with “cultural identity confusion” (Schwartz & Zamboanga, 2008) or with rejecting (or feeling rejected by) both one’s heritage and receiving cultural communities (Sam & Berry, 2010). Thus, a carefree-diffuse approach to personal and cultural identity may have been preceded by a sense of cultural rejection. The same individuals may avoid both cultural identity issues and personal identity development—and this may lead them to become “stuck” in both of these areas.

It is interesting to note that the foreclosed status did not map onto low levels of endorsement of American cultural practices, values, and identifications. Although it appears to make sense that foreclosed individuals should retain their cultural heritage without considering American cultural options, this may not have been the only form of foreclosure present in our sample. It is also possible that some “1.5-generation” or second-generation immigrants (Portes & Rumbaut, 2006) may foreclose on American culture without considering the possibility of retaining elements of their cultural heritage. Indeed, some immigrant groups, such as Chinese and Russians, tend to discard aspects of their heritage (particularly language) following arrival in the United States (Kasinitz et al., 2008; Portes & Rumbaut, 2001). In contrast, Hispanics are more likely than other immigrant groups to retain their heritage language into the second and even third generations (Suárez-Orozco et al., 2008). Therefore, participants identified as foreclosed may represent a mixture of those who foreclosed on their heritage culture and those who foreclosed on American culture. Because we did not ask about the ways in which participants developed their cultural identities, we were not able to provide a definitive verdict on this possibility in the present study.

In addition, the presence of commitments did not necessarily guarantee maximal retention of heritage-cultural practices, values, and identifications. Indeed, for nine of the 10 cultural identity variables, individuals in the foreclosed status scored significantly lower than their achieved and searching-moratorium counterparts. Foreclosed emerging adults from immigrant families may therefore be less likely to hold onto their cultural heritage than anticipated—or, alternatively, the achieved and searching moratorium statuses may involve a creative “deepening” of heritage-cultural affiliations. Supporting this contention, Schwartz and Zamboanga (2008) found that Hispanic emerging adults endorsing the most agentic form of biculturalism were more strongly attached to their cultural heritage than participants classified as separated (i.e., those who retain their cultural heritage and reject the receiving culture). Further, Benet-Martínez and Haritatos (2005) found that bicultural individuals high in bicultural identity integration—a creative and agentic approach to acculturation—endorsed their cultural heritage more strongly than those who did not utilize such an agentic and creative approach. The heritage culture may therefore not be a static entity that is either retained or rejected, but rather a cultural stream that can be personalized through processes of exploration and creativity. Again, this finding represents a parallel between cultural identity and personal identity. Achieved individuals, who maintain flexible and agentic commitments, are more likely to enact commitments that resonate with their personal potentials than are foreclosed individuals, who internalize their commitments from others (Schwartz, Beyers, et al., 2011; Waterman, 2007). Although we did not assess biculturalism directly in the present study, biculturalism may be inferred from high levels of endorsement of both heritage and American cultural elements (Sam & Berry, 2010).

The present findings are also bolstered by consistency across ethnicity. Of the 150 potential ethnic differences in patterns of pairwise comparisons, only three were statistically significant. Further, although all three significant differences were found between the achieved and carefree-diffused statuses, no clear pattern emerged. These differences may therefore be due to chance—especially given that only 2% (3 of 150) of the comparisons conducted yielded significant results. Moreover, results appeared to be fully consistent across immigrant generation, suggesting that between-status differences in patterns of acculturation are similar for first-generation and second-generation individuals. Carefree diffusion was characterized by the lowest mean on all 10 acculturation-related variables for all six ethnic groups examined. Similarly, either achievement or searching moratorium was associated with the highest means for all five heritage-cultural indices and for all five American-cultural indices— and this pattern held for all six ethnic groups. This suggests that Whites, Blacks, Hispanics, East Asians, South Asians, and Middle Easterners who adopt an agentic approach to personal identity development are also likely to adopt a bicultural approach to acculturation. So, although levels of American-cultural acquisition and heritage-cultural retention may differ between or among ethnic groups, the structure of the intersection between personal and cultural identity is likely similar across ethnicity.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

The present results should be considered in light of at least two important limitations. First, the cross-sectional design does not permit examination of directionality or change processes across time. As a result, although the present findings indicate that personal and cultural identities are systematically related, the direction of effects cannot be ascertainedhere. Longitudinal studies are needed to better understand the mechanics underlying the interplay of personal and cultural identity development.

Second, the exclusion of noncollege-attending emerging adults from the present sample does not allow us to examine whether the present results generalize to all emerging adults. Given that more than 15% of Blacks and 25% of Hispanics do not complete high school or an equivalent degree (Gerald & Hussar, 2010, p. 9), the Black and Hispanic participants in the present sample may be less representative of their respective populations compared with the other ethnic groups.

Despite these and other limitations, the present study has generated important new knowledge concerning the convergence of personal and cultural identity development. Specifically, biculturalism—an agentic and creative approach to acculturation—is most likely to be undertaken by individuals who may have purposefully explored personal identity alternatives. Therefore, an agentic and creative approach to acculturation is likely to be linked with an agentic and creative approach to personal identity development. Conversely, individuals who do not engage in much personal identity work are also unlikely to engage in much cultural identity work. These results support prior theoretical (Schwartz et al., 2008) and empirical (Syed, 2010; Usborne & Taylor, 2010) work linking personal and cultural dimensions of identity, and they reinforce the contention that acculturation is in fact an identity process. The task of promoting agentic identity exploration may be doubly important for immigrants—who must define themselves within two cultural worlds, as well as in terms of their personal goals—and it is essential for intervention work to target immigrants who are struggling with (or unwilling to engage in) personal and cultural identity issues. We hope that the present results help to contribute to the well-being and development of first- and second-generation immigrant adolescents and emerging adults, who are one of the fastest growing segments of the United States population.

Members of Underrepresented Groups: Reviewers for Journal Manuscripts Wanted.

If you are interested in reviewing manuscripts for APA journals, the APA Publications and Communications Board would like to invite your participation. Manuscript reviewers are vital to the publications process. As a reviewer, you would gain valuable experience in publishing. The P&C Board is particularly interested in encouraging members of underrepresented groups to participate more in this process.

If you are interested in reviewing manuscripts, please write APA Journals at Reviewers@apa.org. Please note the following important points:

To be selected as a reviewer, you must have published articles in peer-reviewed journals. The experience of publishing provides a reviewer with the basis for preparing a thorough, objective review.

To be selected, it is critical to be a regular reader of the five to six empirical journals that are most central to the area or journal for which you would like to review. Current knowledge of recently published research provides a reviewer with the knowledge base to evaluate a new submission within the context of existing research.

To select the appropriate reviewers for each manuscript, the editor needs detailed information. Please include with your letter your vita. In the letter, please identify which APA journal(s) you are interested in, and describe your area of expertise. Be as specific as possible. For example, “social psychology” is not sufficient—you would need to specify “social cognition” or “attitude change” as well.

Reviewing a manuscript takes time (1–4 hours per manuscript reviewed). If you are selected to review a manuscript, be prepared to invest the necessary time to evaluate the manuscript thoroughly.

APA now has an online video course that provides guidance in reviewing manuscripts. To learn more about the course and to access the video, visit http://www.apa.org/pubs/authors/review-manuscript-ce-video.aspx.

Acknowledgments

The present article was prepared as part of the Multi-Site University Study of Identity and Culture (MUSIC). All members of this collaborative are gratefully acknowledged.

Contributor Information

Seth J. Schwartz, University of Miami

Su Yeong Kim, The University of Texas at Austin.

Susan Krauss Whitbourne, University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Byron L. Zamboanga, Smith College

Robert S. Weisskirch, California State University, Monterey Bay

Larry F. Forthun, University of Florida

Alexander T. Vazsonyi, University of Kentucky

Wim Beyers, Ghent University.

Koen Luyckx, Catholic University of Leuven.

References

- Abraído-Lanza AF, Armbrister AM, Flórez KR, & Aguirre AN (2006). Toward a theory-driven model of acculturation in public health research. American Journal of Public Health, 96, 1342–1346. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.064980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ (2002). The psychology of globalization. American Psychologist, 57, 774–783. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.57.10.774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benet-Martínez V, & Haritatos J (2005). Bicultural identity integration (BII): components and psychosocial antecedents. Journal of Personality, 73, 1015–1050. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00337.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennion LD, & Adams GR (1986). A revision of the extended version of the Objective Measure of Ego Identity Status: An identity instrument for use with late adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research, 1, 183–198. doi: 10.1177/074355488612005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW (1980). Acculturation as varieties of adaptation In Padilla A (Ed.), Acculturation: Theory, models, and some new findings (pp. 9–25). Boulder, CO: Westview Press. [Google Scholar]

- Breckenridge JN (2000). Validating cluster analysis: Consistent replication and symmetry. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 35, 261–285. doi: 10.1207/S15327906MBR3502_5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM (2009). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Philadelphia, PA: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo LG, & Caver KA (2009). Expanding the concept of acculturation in Mexican American rehabilitation psychology research and practice. Rehabilitation Psychology, 54, 351–362. doi: 10.1037/a0017801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung GW, & Rensvold RB (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 9, 233–255. doi: 10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coatsworth JD, Maldonado-Molina M, Pantin H, & Szapocznik J (2005). A person-centered and ecological investigation of acculturation strategies in Hispanic immigrant youth. Journal of Community Psychology, 33, 157–174. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Côté JE, & Levine CG (2002). Identity formation, agency, and culture: A social psychological synthesis. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Crocetti E, Rubini M, & Meeus W (2008). Capturing the dynamics of identity formation in various ethnic groups: Development and validation of a three-dimensional model. Journal of Adolescence, 31, 207–222. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH (1950). Childhood and society. New York, NY: Norton [Google Scholar]

- Gerald DE, & Hussar WJ (2000). Projections of education statistics to 2010. Education Statistics Quarterly, 2, 7–13. Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/pubs2000/2000071.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Gore PA (2000). Cluster analysis In Tinsley HEA & Brown SD (Eds.), Handbook of applied multivariate statistics and mathematical modeling (pp. 297–321). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. doi: 10.1016/B978-012691360-6/50012-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grotevant HD (1987). Toward a process model of identity formation. Journal of Adolescent Research, 2, 203–222. doi: 10.1177/074355488723003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X, Schwartz SJ, & McCabe BE (2008). Aging, gender, and self: Dimensionality and measurement invariance analysis on self-construal. Self and Identity, 7, 1–24. doi: 10.1080/15298860600926873 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh Q-L, Nguyen A-MD, & Benet-Martínez V (2011). Bicultural identity integration In Schwartz SJ, Luyckx K, & Vignoles VL (Eds.), Handbook of identity theory and research (pp. 827–842). New York, NY: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-7988-9_35 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen LA, Arnett JJ, & McKenzie J (2011). Globalization and cultural identity In Schwartz SJ, Luyckx K, & Vignoles VL (Eds.), Handbook of identity theory and research (pp. 285–301). New York, NY: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-7988-9_13 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RM, Akers JF, & White JM (1994). Revised classification criteria for the Extended Objective Measure of Ego Identity Status (EOM-EIS). Journal of Adolescence, 17, 533–549. doi: 10.1006/jado.1994.1047 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kasinitz P, Mollenkopf J, Waters M, & Holdaway J (2008). Inheriting the city: The children of immigrants come of age. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kauermann G, & Carroll RJ (2001). A note on the efficiency of sandwich covariance matrix estimation. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 96, 1387–1396. doi: 10.1198/016214501753382309 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kroger J, & Marcia JE (2011). The identity statuses: Origins, meanings, and interpretations In Schwartz SJ, Luyckx K, & Vignoles VL (Eds.), Handbook of identity theory and research (pp. 31–53). New York, NY: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-7988-9_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luyckx K, Duriez B, Klimstra TA, & De Witte H (2010). Identity statuses in young adult employees: Prospective relations with work engagement and burnout. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 77, 339–349. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2010.06.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luyckx K, Goossens L, & Soenens B (2006). A developmental contextual perspective on identity construction in emerging adulthood: Change dynamics in commitment formation and commitment evaluation. Developmental Psychology, 42, 366–380. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luyckx K, Goossens L, Soenens B, & Beyers W (2006). Unpacking commitment and exploration: Preliminary validation of an integrative model of late adolescent identity formation. Journal of Adolescence, 29, 361–378. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2005.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luyckx K, Goossens L, Soenens B, Beyers W, & Vansteenkiste M (2005). Identity statuses based on 4 rather than 2 identity dimensions: Extending and refining Marcia’s paradigm. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 34, 605–618. doi: 10.1007/s10964-005-8949-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luyckx K, Schwartz SJ, Berzonsky MD, Soenens B, Vansteenkiste M, Smits I, & Goossens L (2008). Capturing ruminative exploration: Extending the four-dimensional model of identity formation in late adolescence. Journal of Research in Personality, 42, 58–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2007.04.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luyckx K, Schwartz SJ, Goossens L, Beyers W, & Missotten L (2011). Processes of personal identity formation and evaluation In Schwartz SJ, Luyckx K, & Vignoles VL (Eds.), Handbook of identity theory and research (pp. 77–98). New York, NY: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-7988-9_4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luyckx K, Seiffge-Krenke I, Schwartz SJ, Goossens L, Weets I, Hendrieckx C, & Groven C (2008). Identity development, coping, and adjustment in emerging adults with a chronic illness: The sample case of Type 1 diabetes. Journal of Adolescent Health, 43(5), 451–458. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcia JE (1966). Development and validation of ego-identity status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 3, 551–558. doi: 10.1037/h0023281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeus W, van de Schoot R, Keijsers L, Schwartz SJ, & Branje S (2010). On the progression and stability of adolescent identity formation: A five-wave longitudinal study in early-to-middle and middle-to-late adolescence. Child Development, 81, 1565–1581. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01492.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery MJ, & Côté JE (2003). College as a transition to adulthood In Adams GR & Berzonsky MD, (Eds.), Blackwell handbook of adolescence (pp. 149–172). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (2007). Mplus user’s guide. Los Angeles, CA: Authors. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS (1992). The multigroup ethnic identity measure: A new scale for use with diverse groups. Journal of Adolescent Research, 7, 156–176. doi: 10.1177/074355489272003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, & Ong AD (2007). Conceptualization and measurement of ethnic identity: Current status and future directions. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54, 271–281. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.54.3.271 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Portes A, & Rumbaut RG (2001). Legacies: The story of the immigrant second generation. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Portes A, & Rumbaut RG (2006). Immigrant America: A portrait. Berkley, CA: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, & Bryk AS (2002). Hierarchical linear models (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie RA, Meca A, Madrazo VL, Schwartz SJ, Hardy SA, Zamboanga BL, … Lee RM (in press). Identity dimensions and related processes in emerging adulthood: Helpful or harmful? Journal of Clinical Psychology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sam DL, & Berry JW (2010). Acculturation: When individuals and groups of different cultural backgrounds meet. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5, 472–481. doi: 10.1177/1745691610373075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlomer GL, Bauman S, & Card NA (2010). Best practices for missing data management in counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 57, 1–10. doi: 10.1037/a0018082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Beyers W, Luyckx K, Soenens B, Zamboanga BL, Forthun LF,... Waterman AS (2011). Examining the light and dark sides of emerging adults’ identity: A study of identity status differences in positive and negative psychosocial functioning. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40, 839–859. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9606-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Côté JE, & Arnett JJ (2005). Identity and agency in emerging adulthood: Two developmental routes in the individualization process. Youth & Society, 37, 201–229. doi: 10.1177/0044118X05275965 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Montgomery MJ, & Briones E (2006). The role of identity in acculturation among immigrant people: Theoretical propositions, empirical questions, and applied recommendations. Human Development, 49, 1–30. doi: 10.1159/000090300 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Park IJK, Huynh Q-L, Zamboanga BL, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Lee RM, … Agocha VB (2012). The American Identity Measure: Development and validation across ethnic subgroup and immigrant generation. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research, 12, 93–128. doi: 10.1080/15283488.2012.668730 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Zamboanga BL, & Szapocznik J (2010). Rethinking the concept of acculturation: Implications for theory and research. American Psychologist, 65, 237–251. doi: 10.1037/a0019330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Waterman AS, Vazsonyi AT, Zamboanga BL, Whitbourne SK, Weisskirch RS, … Ham LS (2011). The association of well-being with health risk behaviors in college-attending young adults. Applied Developmental Science, 15, 20–36. doi: 10.1080/10888691.2011.538617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Weisskirch RS, Hurley EA, Zamboanga BL, Park IK, Kim S, & Greene AD (2010). Communalism, familism, and filial piety: Are they birds of a collectivist feather? Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 16, 548–560. doi: 10.1037/a0021370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Zamboanga BL, & Weisskirch RS (2008). Broadening the study of the self: Integrating the study of personal identity and cultural identity. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2, 635–651. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2008.00077.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singelis TM (1994). The measurement of independent and interdependent self-construals. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 20, 580–591. doi: 10.1177/0146167294205014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PB, Bond MH, & Kağıtçıbaşı Ҫ (2006). Understanding social psychology across cultures. London, UK: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner N (2009). International migration and citizenship today. New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Steinley D (2004). Properties of the Hubert-Arable adjusted Rand index. Psychological Methods, 9, 386–396. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.9.3.386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinley D, & Brusco MJ (2007). Initializing K-means batch clustering: A critical evaluation of several techniques. Journal of Classification, 24, 99–121. doi: 10.1007/s00357-007-0003-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steinley D, & Brusco MJ (2008). A new variable weighting and selection procedure for K-means cluster analysis. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 43, 77–108. doi: 10.1080/00273170701836695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson M (2000). Development and validation of the Stephenson Multigroup Acculturation Scale (SMAS). Psychological Assessment, 12, 77–88. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.12.1.77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Orozco C, Suárez-Orozco MM, & Todorova I (2008). Learning a new land: Immigrant students in American society. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Syed M (2010). Developing an integrated self: Academic and ethnic identities among ethnically diverse college students. Developmental Psychology, 46, 1590–1604. doi: 10.1037/a0020738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syed M, & Azmitia M (2009). Longitudinal trajectories of ethnic identity during the college years. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 19, 601–624. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00609.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Triandis HC, & Gelfand MJ (1998). Converging measurement of horizontal and vertical individualism and collectivism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 118–128. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.74.1.118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Usborne E, & Taylor DM (2010). The role of cultural identity clarity for self-concept clarity, self-esteem, and subjective well-being. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36, 883–897. doi: 10.1177/0146167210372215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberg RJ, & Lance CE (2000). A review and synthesis of the measurement invariance literature: Suggestions, practices, and recommendations for organizational research. Organizational Research Methods, 3, 4–70. doi: 10.1177/109442810031002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Vijver FJR, & Phalet K (2004). Assessment in multicultural groups: The role of acculturation. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 53, 215–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2004.00169.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vignoles VL, Schwartz SJ, & Luyckx K (2011). Introduction: Toward an integrative view of identity In Schwartz SJ, Luyckx K, & Vignoles VL (Eds.), Handbook of identity theory and research (pp. 1–27). New York, NY: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-7988-9_1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Waterman AS (2007). Doing well: The relationship of identity status to three conceptions of well-being. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research, 7, 289–308. [Google Scholar]

- Weinreich P (2009). ‘Enculturation’, not ‘acculturation’: Conceptualising and assessing identity processes in migrant communities. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 33, 124–139. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2008.12.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Worrell FC, Cross WE Jr., & Vandiver BJ (2001). Nigrescence theory: Current status and challenges for the future. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 29, 201–213. doi: 10.1002/j.2161-1912.2001.tb00517.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]