Abstract

Background:

People with substance use disorders (SUD) and co-occurring chronic pain report the use of myriad substances, which is concerning due to the heightened risk of overdose associated with polysubstance use. Identifying malleable factors associated with polysubstance use in this population can inform interventions. In this study, we examined whether two pain processes—pain interference and pain catastrophizing—were associated with polysubstance use.

Objectives:

We examined the cross-sectional associations among self-reported pain interference and catastrophizing and polysubstance use. We also determined if sex and primary SUD moderated these associations.

Methods:

Participants were 236 (36% female) adults receiving inpatient treatment for SUD (58% alcohol use disorder, 42% opioid use disorder) who met criteria for chronic pain. We utilized negative binomial regression to examine associations between pain interference and catastrophizing (focal independent variables) and the number of substances used in the month before treatment (i.e., polysubstance use; outcome).

Results:

Participants used three substances, on average, in the month prior to treatment. Neither pain interference (IRR=1.05, p=0.06) nor pain catastrophizing (IRR=1.00, p=0.37) were associated with polysubstance use. The association between pain interference and polysubstance use was moderated by sex and primary SUD (ps<0.01), such that these variables were positively related in men and those with alcohol use disorder.

Conclusion:

Pain interference and catastrophizing were not uniformly associated with polysubstance use, underscoring the need to examine other factors associated with polysubstance use in this population. However, men and those with alcohol use disorder might benefit from interventions targeting pain interference to reduce polysubstance use.

Keywords: chronic pain, pain interference, pain catastrophizing, polysubstance use, alcohol use disorder, opioid use disorder, sex

Introduction

Chronic pain is highly prevalent in people with opioid use disorder (with estimates ranging from 42% to 61%; (1)) and is also prevalent among those with other substance use disorders (SUD), including alcohol, sedative, cannabis, and stimulant use disorders (2,3). The co-occurrence between chronic pain and SUD might be explained by reciprocal relationships, such that substance use can be motivated by pain relief but can also cause acute and prolonged hyperalgesia (4). Indeed, many substances, such as opioids, cannabis, and alcohol, have analgesic properties and are often used or misused (i.e., the use of a prescription drug in larger amounts than prescribed or without a prescription) to relieve pain (2,5,6). However, individuals with SUD and co-occurring chronic pain also demonstrate high rates of use of substances that are not traditional analgesics (e.g., cocaine; (7)) and report substance use for reasons beyond pain relief, including to get high, to modify the effects of other substances, and to relieve negative affective states (8).

Despite the links between pain and the use of myriad substances, little is known about the association between pain and polysubstance use, defined as the use of two or more substances over a defined period (9). Previous cross-sectional studies among those with chronic pain have found that polysubstance use is associated with greater pain severity (10). Moreover, polysubstance use is highly concerning in this population due to its association with overdose in people with chronic pain (11). These findings underscore the importance of identifying malleable factors associated with polysubstance use among those with chronic pain to inform targeted interventions. The aim of the current paper was to investigate whether pain processes other than pain severity itself, pain interference and pain catastrophizing, were associated with greater likelihood of polysubstance use in people with SUD and co-occurring chronic pain.

Pain interference and pain catastrophizing are processes that have been associated with substance use in several populations. Notably, these constructs represent poorer functioning and negative affect in response to pain, beyond the burden of pain severity itself. Pain interference is the extent to which pain affects social, emotional, physical, and recreational functioning (12) and pain catastrophizing is the tendency to magnify the threat of pain and to feel helpless in response to pain (13). Among respondents to the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, pain interference has been associated with the onset of alcohol, nicotine, cannabis, and opioid use disorders from 2001–2002 to 2004–2005 (14–16). Consistent with these findings, those entering treatment for SUD have greater pain interference than community samples (17). Among those with chronic pain, pain interference is associated with cannabis (18) and alcohol use (19) and pain catastrophizing is associated with opioid misuse (20). Pain catastrophizing has also been associated with greater substance craving among those in SUD treatment who met criteria for chronic pain (21).

Many authors have proposed that pain interference and catastrophizing might contribute to greater substance use, above and beyond pain intensity, because individuals use substances to cope with physical pain, which is magnified by increased pain interference and catastrophizing, and related negative affect (4,14,20). Accordingly, these constructs might also be associated with the use of multiple substances to cope with physical pain and negative affect. Indeed, greater polysubstance use has been associated with higher likelihood of endorsing coping motives for substance use among general population and community samples (22,23). The use of multiple substances to cope with physical pain and negative affect might not be limited to analgesic substances, given recent qualitative findings that those with SUD and co-occurring chronic pain use a variety of substances to “numb emotions” and delay awareness of pain (8).

The primary aim of the present study was to examine the associations among pain interference and catastrophizing and polysubstance use among those in SUD treatment who met criteria for chronic pain. We hypothesized that greater pain interference and catastrophizing would be associated with more substances used in the previous month, above and beyond pain intensity, age, sex, primary SUD (i.e., alcohol use disorder vs. opioid use disorder), and co-occurring psychiatric disorders. We chose pain processes as focal independent variables, as opposed to pain intensity, because they can be targeted in cognitive and behavioral treatments (4,24,25). Examining correlates of polysubstance use among those in SUD treatment with co-occurring chronic pain can inform potential treatment targets at a point of intervention.

In exploratory analyses, we examined sex and primary SUD as moderators of these associations. Previous studies among those in the U.S. general population have found that the association between pain interference and substance use is moderated by sex, but the direction of these results has been inconsistent (i.e., stronger associations in both women and men; (14,15)). A recent analysis found that pain-related anxiety, a construct highly related to pain catastrophizing, was associated with greater alcohol consumption and alcohol-related consequences in males with chronic pain, but not females (26). We examined the moderating effect of primary SUD because those with alcohol use and alcohol use disorder generally demonstrate lower levels of pain processes (e.g., catastrophizing and pain-related distress; (21,27)) and polysubstance use (28,29), as compared to those with opioid misuse. Accordingly, the strength or direction of the associations among pain interference and catastrophizing and polysubstance use might differ by primary SUD.

Method

Data Source and Participants

Participants were recruited from the inpatient detoxification and stabilization unit of McLean Hospital as part of a larger survey study characterizing individuals receiving brief (average 4 days) inpatient treatment for SUD. Inclusion criteria for this study required that participants were at least 18 years of age, were receiving treatment for a SUD, were not experiencing an acute medical/psychiatric disorder that would interfere with participation, and were not involuntarily admitted to treatment. During treatment, participants provided informed consent and then completed a battery of self-report questionnaires on a tablet, which took approximately 30 minutes to complete. Study staff could also read the survey to participants, if necessary or requested by the participant. In addition, primary SUD and co-occurring psychiatric diagnoses were extracted from participants’ medical charts. For the present analysis, we recoded information on specific psychiatric disorders to reflect any presence of a co-occurring psychiatric disorder. All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the local Institutional Review Board.

Data collection for the larger study has been ongoing since 2013 (N=995). For the present analysis, we included respondents who reported chronic pain, completed all relevant questionnaires (e.g., pain severity, pain catastrophizing, pain interference, and past-month substance use), were seeking treatment for either alcohol or opioid use disorder, and reported the use of at least one substance in the previous month (n=236).

Measures

Sex and age were self-reported by participants. Participants also self-reported racial/ethnic identity; however, this was not included in the present analysis given that 90.9% of participants identified as non-Hispanic White. As previously reported, we created a dichotomous variable indicating if a co-occurring psychiatric diagnosis was reported in medical charts.

The Brief Addiction Monitor was utilized to assess past-month substance use (30). Participants reported use of the following substances in the previous month: alcohol, benzodiazepines, other tranquilizers/sedatives (e.g., zolpidem, barbiturates), cocaine, other stimulants (e.g., methamphetamine and prescription amphetamines), heroin, opioid analgesics, inhalants, and any other drugs. Participants were instructed to only report illicit use or misuse (i.e., use without a prescription or in greater amounts than prescribed) of prescription substances and cannabis. Importantly, this measure aims to capture recreational cannabis use, even if legally purchased in Massachusetts, but not medicinal cannabis use. Consistent with previous analyses (31), we created a variable representing the number of substances participants used in the month prior to treatment (i.e., polysubstance use; not including nicotine products). Participants also reported frequencies of use, based either on categorical response options (0, 1–3, 4–8, 9–15, or 16–30 days) or as a continuous response, depending on enrollment date. Continuous frequencies of use were recoded into categorical frequencies for the present analysis.

The Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) was used to assess chronic pain, pain severity, and pain interference with daily life (12). Participants were asked whether they had experienced any pain beyond typical aches and pains on the day they completed the survey, excluding pain from withdrawal (i.e., “Throughout our lives, most of us have had pain from time to time, such as minor headaches, sprains, and toothaches. Have you had pain other than these everyday kinds of pain today? Do not include pain associated with alcohol or drug withdrawal.”; (12)). If participants responded affirmatively, they indicated the amount of time they had been experiencing that pain. If participants reported experiencing pain for at least three months, they were categorized as having chronic pain. Pain severity was assessed as pain on average over the preceding 24 hours, with response options ranging from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst pain imaginable). Those with chronic pain then answered seven questions to determine the extent to which pain interferes with daily life, including interference with general activity, mood, walking activity, normal work, relationships, sleep and enjoyment of life. Response options ranged from 0 (no interference) to 10 (complete interference), and total pain interference scores represented a mean of all 7 questions. The pain interference subscale demonstrated excellent internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s α=.91).

The Pain Catastrophizing Scale was utilized to measure the extent to which participants magnify the threat of pain and feel helpless in response to pain (13). Participants answer 13 questions indicating the degree to which they experience certain thoughts when they are in pain (e.g., “I worry all the time about whether the pain will end,” “There’s nothing I can do to reduce the intensity of the pain”). Response options range from “not at all” (rated a 0) to “all the time” (rated a 4) for a possible range of scores from 0 to 52. This measure demonstrated excellent internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s α=.95).

Statistical Analyses

Data were prepared and descriptive statistics were calculated in SPSS version 26; all other analyses were conducted in MPlus version 8 (32). We first assessed skew and univariate outliers to determine appropriate statistical tests; we did not detect univariate outliers.

A series of negative binomial regression analyses were conducted to examine the association between pain interference and pain catastrophizing (focal independent variables) and polysubstance use (outcome). Negative binomial regression was chosen given that the dependent variable, polysubstance use, was skewed and demonstrated a larger variance than mean. In order to utilize a negative binomial distribution (as opposed to a zero-truncated negative binomial distribution), we transformed the polysubstance use variable by subtracting one from all responses. Thus, the polysubstance use variable represented the number of substances greater than one that a participant used in the previous month in negative binomial regression analyses (including participants’ primary substance). When reporting descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations, we utilized the raw, non-transformed polysubstance use variable for ease of interpretation.

Given the strong association between pain interference and pain catastrophizing (see Table 1), we tested these focal independent variables in separate models. Overall, we conducted four separate models, using a corrected alpha of p<0.0125 for determining statistical significance. The first model examined the main effects of pain interference on polysubstance use. In the second model, we included two interaction terms (sex × pain interference, primary SUD × pain interference) to determine if these characteristics moderated the association between pain interference and polysubstance use. We then completed these steps with pain catastrophizing as the focal independent variables (i.e., main effects examined in the first model and interaction effects examined in a second model). All models controlled for age, sex, pain severity, co-occurring psychiatric diagnosis, and primary SUD. Covariates were selected prior to conducting analyses, based on factors that have been previously associated with pain-related processes and polysubstance use (9,21). We mean-centered continuous variables (e.g., age, pain severity, pain interference, and pain catastrophizing) to improve interpretation and mitigate unnecessary multicollinearity related to interaction terms. We converted raw regression coefficients into incident rate ratios (IRRs), which represent the proportional change in the dependent variable for every one-unit increase in the independent variable.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) or % | 40.4 (14.0) | 68.2% | 64.8% | 41.5% | 5.7 (1.8) | 4.9 (2.5) | 21.7 (14.0) | 2.9 (2.1) |

| 1. Age | - | |||||||

| 2. Male | −.09 | - | ||||||

| 3. Co-Occurring Psychiatric Diagnosis | .05 | −.22** | - | |||||

| 4. Opioid as Primary SUD | −.52** | .15* | −.12 | - | ||||

| 5. Pain Severity | −.08 | −.02 | −.02 | .08 | - | |||

| 6. Pain Interference | −.004 | −.02 | .11 | .11 | .53** | - | ||

| 7. Pain Catastrophizing | −.13 | .002 | .11 | .16* | .52** | .70** | - | |

| 8. # Substances Used | −.59** | .11 | −.01 | .59** | .14* | .15* | .18** | - |

Note: All correlations with pain catastrophizing only include 233 participants, given that three participants in the study sample were missing Pain Catastrophizing Scale data.

p<.05,

p<.01

Results

Descriptive Results and Bivariate Correlations

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations are reported in Table 1. A majority of participants with chronic pain were male (68.2%), were receiving treatment for alcohol use disorder (58.5%), and had a co-occurring psychiatric disorder (64.8%). The average age of the sample was 40.4 years. On average, participants reported moderate levels of pain severity and pain interference. The average pain catastrophizing score was similar to the score reported by a sample seeking treatment at a pain clinic (13).

Participants with chronic pain used an average of 2.9 (SD=2.1) substances in the previous month. Overall, 41.9% of participants reported using one substance in the month before treatment (defined as “0” for the polysubstance use outcome in negative binomial regression analyses), 8.9% used two substances, 14.8% used three substances, 8.5% used four substances, 13.1% used five substances, 5.1% used six substances, 4.7% used seven substances, 1.7% used eight substances, 0.8% used nine substances, and 0.4% used ten substances. The incidence and frequency of use for each substance category is presented in Table 2. Participants most commonly reported alcohol use (82.2%), followed by opioid analgesics (39.4%), cannabis (36.0%), benzodiazepines (33.5%), heroin (33.1%), cocaine (25.8%), other drugs (16.9%), stimulants (12.7%), other sedative/tranquilizer medications (11.4%), and inhalants (1.3%).

Table 2.

Incidence and frequency of past-month substance use

| No Use | Any Use | 1–3 Days of Use | 4–8 Days of Use | 9–15 Days of Use | 16+ Days of Use | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Alcohol | 42 | 17.8% | 194 | 82.2% | 36 | 15.3% | 24 | 10.2% | 25 | 10.6% | 109 | 46.2% |

| Opioid analgesics | 143 | 60.6% | 93 | 39.4% | 21 | 8.9% | 16 | 6.8% | 10 | 4.2% | 46 | 19.5% |

| Cannabis | 151 | 64.0% | 85 | 36.0% | 24 | 10.2% | 18 | 7.6% | 14 | 5.9% | 29 | 12.3% |

| Benzodiazepines | 157 | 66.5% | 79 | 33.5% | 21 | 8.9% | 21 | 8.9% | 18 | 7.6% | 19 | 8.1% |

| Heroin | 158 | 66.9% | 78 | 33.1% | 8 | 3.4% | 1 | 0.4% | 8 | 3.4% | 61 | 25.8% |

| Cocaine | 175 | 72.2% | 61 | 25.8% | 23 | 9.7% | 15 | 6.4% | 14 | 5.9% | 9 | 3.8% |

| Other drugs | 196 | 83.1% | 40 | 16.9% | 9 | 3.8% | 18 | 7.6% | 4 | 1.7% | 9 | 3.8% |

| Stimulants | 206 | 87.3% | 30 | 12.7% | 16 | 6.8% | 4 | 1.7% | 3 | 1.3% | 7 | 3.0% |

| Other tranquilizers/sedatives | 209 | 88.6% | 27 | 11.4% | 13 | 5.5% | 8 | 3.4% | 4 | 1.7% | 2 | 0.8% |

| Inhalants | 233 | 98.7% | 3 | 1.3% | 3 | 1.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

Both pain interference (r=.15, p=.022) and pain catastrophizing (r=.18, p=.005) were weakly associated with greater polysubstance use in bivariate analyses.

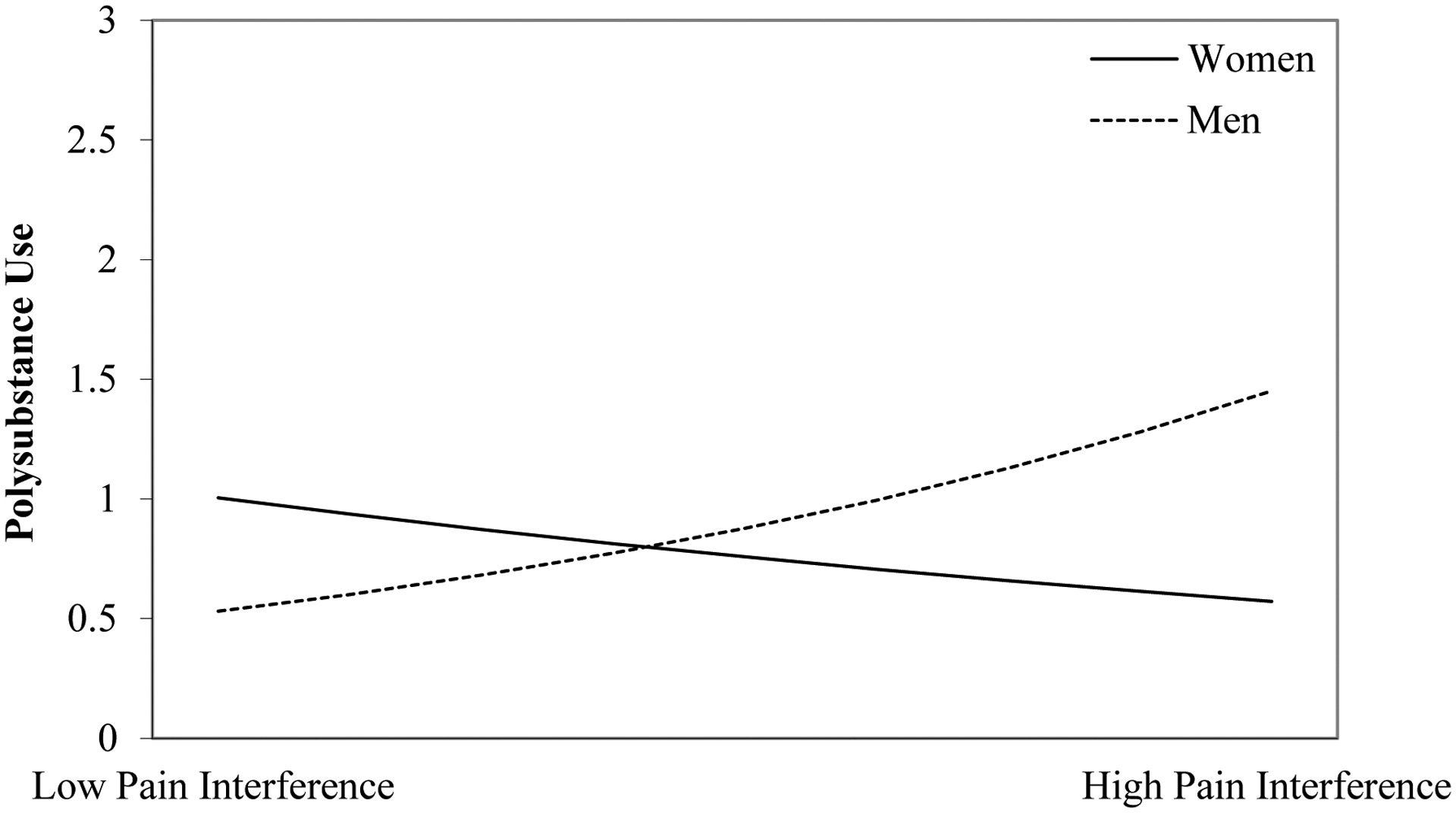

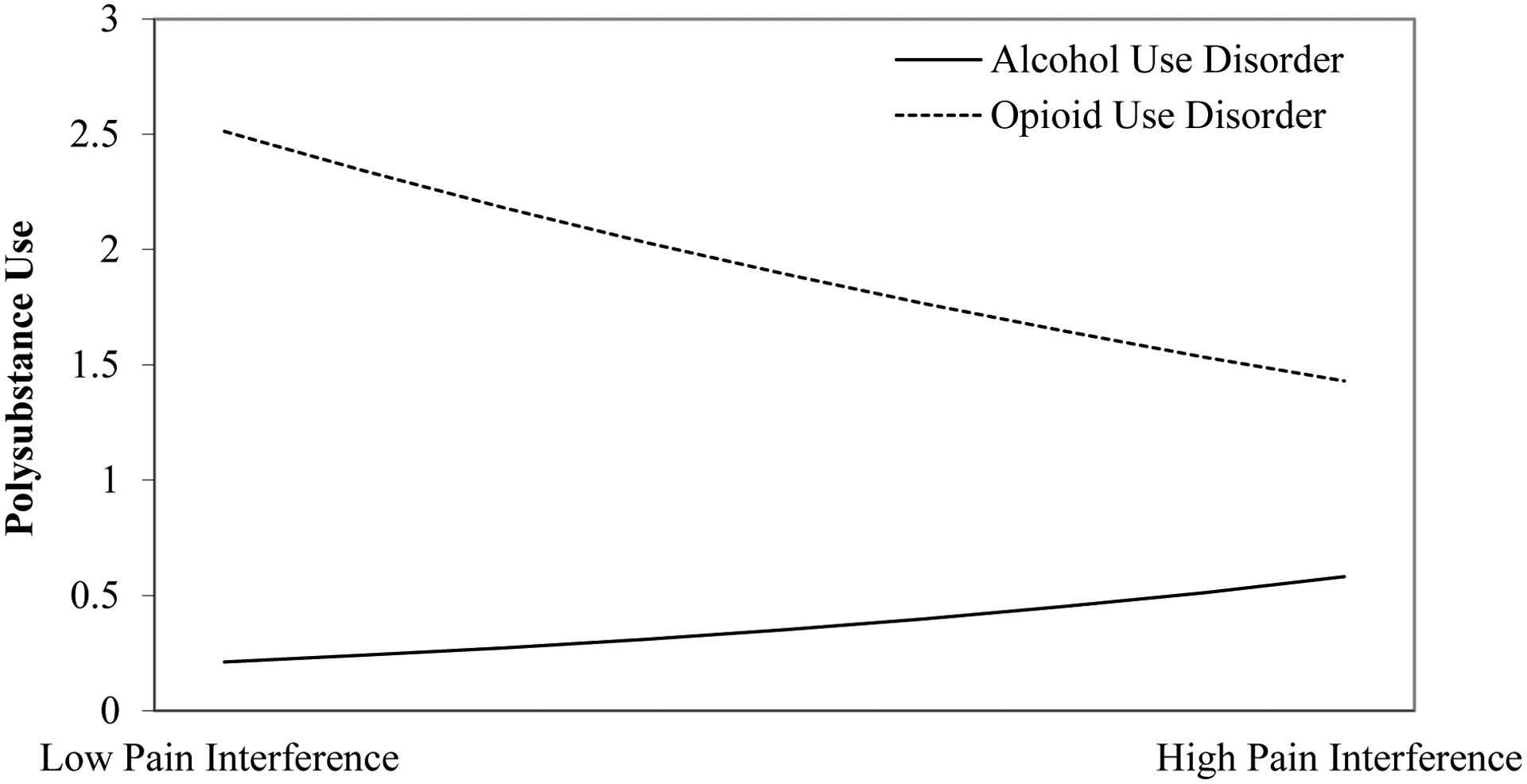

Pain Interference and Polysubstance Use

Results of the negative binomial regression models examining main effects of pain interference on polysubstance use (Model 1) and the interactions between sex and pain interference and between primary SUD and pain interference (Model 2) are presented in Table 3. Greater pain interference was not associated with past-month polysubstance use (IRR=1.05, 95% CI=0.997, 1.12, p=0.059) after controlling for age, sex, pain severity, co-occurring psychiatric diagnoses, and primary SUD. However, sex moderated the association between pain interference and polysubstance use (IRR=1.17, 95% CI=1.06, 1.23, p=0.001). Simple slopes analysis revealed that males exhibited a positive and stronger relationship between pain interference and polysubstance use (n=161; b=0.08, 95% CI=0.02, 0.14), whereas females demonstrated no association (n=75; b=−0.02, 95% CI=−0.13, 0.10). The adjusted interaction effect is presented in Figure 1, with the outcome variable of polysubstance use representing the number of substances greater than one used in the previous month. Primary SUD also moderated the association between pain interference and polysubstance use (IRR=0.86, 95% CI=0.78, 0.93, p=0.001), such that this association was marginally stronger in those with alcohol use disorder (n=138; b=0.12, 95% CI=−0.03, 0.27) than those with opioid use disorder (n=98; b=0.00, 95% CI=−0.05, 0.05). The adjusted interaction effect is presented in Figure 2, and reveals that those with opioid use disorder had higher rates of polysubstance use than those with alcohol use disorder across levels of pain interference; however, there was a weak positive relationship between pain interference and polysubstance use among those with alcohol use disorder. Primary opioid use disorder and younger age were also associated with greater polysubstance use.

Table 3.

Negative binomial regression models examining the association between pain interference and polysubstance use

| Variable | b (SE) | IRR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | |||

| Age | −0.04 (0.01) | 0.96 (0.95, 0.97) | <0.001 |

| Sex (Male=1) | 0.13 (0.13) | 1.14 (0.86, 1.42) | 0.304 |

| Co-occurring Psychiatric Diagnosis (Yes=1) | 0.10 (0.12) | 1.10 (0.84, 1.36) | 0.425 |

| Primary SUD (Opioid Use Disorder=1) | 0.77 (0.14) | 2.16 (1.57, 2.75) | <0.001 |

| Pain Severity | 0.03 (0.04) | 1.03 (0.96, 1.10) | 0.439 |

| Pain Interference | 0.05 (0.03) | 1.05 (1.00, 1.12) | 0.059 |

| Model 2 | |||

| Sex × Pain Interference | 0.16 (0.05) | 1.17 (1.06, 1.23) | 0.001 |

| Primary SUD × Pain Interference | −0.16 (0.05) | 0.86 (0.78, 0.93) | 0.001 |

Note: Model 2 included all variables in Model 1, as well as interaction terms shown in the table.

Figure 1.

The association between pain interference and polysubstance use is stronger in men than in women

Note: The polysubstance use variable represents the number of substances greater than one that a participant used in the previous month (e.g., a value of zero for polysubstance use is equivalent to one substance used in the previous month). Low pain interference = −1 standard deviation of the pain interference scores; high pain interference = +1 standard deviation of the pain interference scores.

Figure 2.

The association between pain interference and polysubstance use is positive in those with alcohol use disorder but not those with opioid use disorder

Note: The polysubstance use variable represents the number of substances greater than one that a participant used in the previous month (e.g., a value of zero for polysubstance use is equivalent to one substance used in the previous month). Low pain interference = −1 standard deviation of the pain interference scores; high pain interference = +1 standard deviation of the pain interference scores.

Pain Catastrophizing and Polysubstance Use

Results of the negative binomial regression models examining main effects of pain catastrophizing on polysubstance use (Model 1) and the interactions between sex and pain catastrophizing and between primary SUD and pain catastrophizing (Model 2) are presented in Table 4. We did not identify an association between pain catastrophizing and polysubstance use (IRR=1.00, 95% CI=0.995, 1.01, p=0.367), and this association was not moderated by either sex (IRR=1.01, 95% CI=0.996, 1.03, p=0.127) or primary SUD (IRR=0.66, 95% CI=0.30, 1.02, p=0.131). As with pain interference analyses, primary opioid use disorder and younger age were associated with greater polysubstance use.

Table 4.

Negative binomial regression models examining the association between pain catastrophizing and polysubstance use

| Variable | b (SE) | IRR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | |||

| Age | −0.04 (0.01) | 0.96 (0.95, 0.97) | <0.001 |

| Sex (Male=1) | 0.13 (0.13) | 1.14 (0.85, 1.42) | 0.311 |

| Co-occurring Psychiatric Diagnosis (Yes=1) | 0.12 (0.12) | 1.13 (0.87, 1.40) | 0.299 |

| Primary SUD (Opioid Use Disorder=1) | 0.78 (0.14) | 2.19 (1.60, 2.78) | <0.001 |

| Pain Severity | 0.05 (0.04) | 1.05 (0.97, 1.13) | 0.194 |

| Pain Catastrophizing | 0.004 (0.01) | 1.00 (0.995, 1.01) | 0.367 |

| Model 2 | |||

| Sex × Pain Catastrophizing | 0.01 (0.01) | 1.01 (0.996, 1.03) | 0.127 |

| Primary SUD × Pain Catastrophizing | −0.42 (0.28) | 0.66 (0.30, 1.02) | 0.131 |

Note: These models only included 233 participants, given that three participants in the study sample were missing Pain Catastrophizing Scale data. Model 2 included all variables in Model 1, as well as interaction terms shown in the table.

Discussion

Previous work has found those with SUD and co-occurring chronic pain report the use of myriad substances (7), and polysubstance use is associated with greater pain severity (10) and risk of overdose (11) among those with chronic pain. In the current study, participants with SUD and chronic pain reported concurrent use of three substances, on average, in the previous month, with 58% of participants using at least two substances. The most commonly used substances were alcohol, opioid analgesics, cannabis, benzodiazepines, and heroin. These findings are concerning given that co-use of substances, particularly alcohol, opioids, and benzodiazepines, is associated with increased risk of overdose (33).

Contrary to our hypotheses, neither pain interference nor pain catastrophizing were associated with polysubstance use in the month prior to SUD treatment in the current sample. However, pain interference was associated with greater polysubstance use among men. There was also a weak positive association between pain interference and polysubstance use among those with alcohol use disorder, but no association between pain interference and polysubstance use among those with opioid use disorder. Neither sex nor primary SUD moderated the association between pain catastrophizing and polysubstance use.

As previously reviewed, pain interference has been associated with the development of SUD among adults in the U.S. general population (14–16). Pain catastrophizing has been associated with pain medication misuse among those with chronic pain (20) and greater craving and psychiatric severity among those with SUD (21). It has been suggested that these associations may be attributable to the use of substances to cope with physical and emotional pain (14,20). Consistent with these prior findings, pain interference and catastrophizing were associated with polysubstance use in bivariate analyses; however, these variables were not significant when controlling for other covariates in the present analysis. The relatively high level of substance use severity of our present sample (i.e., individuals seeking inpatient detoxification treatment) might have limited the associations between pain processes and polysubstance use. Future studies should examine the impact of pain interference and catastrophizing on polysubstance use among individuals with chronic pain but lower levels of substance use severity. In addition, environmental and intrapersonal stress in the month prior to treatment admission might have affected substance use more than pain processes, thus rendering null associations between pain processes and polysubstance use in the present sample.

The finding that primary SUD moderated the association between pain interference and polysubstance use might support our hypothesis that high levels of substance use severity limited the associations among pain processes and the use of multiple substances. A week positive association between pain interference and polysubstance use among those with alcohol use disorder and no association among those with opioid use disorder characterized this moderation effect. Those with opioid use disorder generally have higher levels of polysubstance use than those with alcohol use disorder (28,29), and opioid use disorder was strongly associated with greater polysubstance use in the present analysis (see Tables 3 and 4). Given the weak association between pain interference and polysubstance use among those with alcohol use disorder, future research examining reasons for polysubstance use in this subgroup will determine if pain interference is a viable target to decrease the use of multiple substances.

Further, the association between pain interference and polysubstance use was positive and statistically significant among men, but not women. Prior studies examining sex differences in the impact of pain interference on substance use behaviors have demonstrated mixed findings. For example, some studies in general population samples have found that the association between pain interference and nicotine dependence is stronger in women (15) whereas others have reported a strong association among men (14). Likewise, the association between pain interference and alcohol use disorder has been shown to be stronger in women in some studies (15) and men in others (14). Some evidence suggests that men might be more likely to use substances to cope with physical pain than women (34), thus potentially explaining a stronger association between pain interference and polysubstance use among men in the present analysis. Nonetheless, more research is needed to clarify these mixed findings, including studies that consider variables such as hormone fluctuations.

There are several limitations to the present analysis. First, neither causality nor temporality can be inferred from the present results given that this was a cross-sectional analysis. Second, individuals in the present analysis were receiving inpatient detoxification and stabilization treatment, and therefore findings might not generalize to non-treatment-seeking individuals. In particular, pain severity, interference, and catastrophizing scores might have been influenced by acute detoxification, even though participants were instructed not to report pain due to withdrawal. Similarly, substance use in the month prior to detoxification, including polysubstance use, might not be representative of typical substance use patterns. These findings might also have limited generalizability to racial and ethnically diverse populations, give than over 90% of the present sample identified as Non-Hispanic White.

In addition, information was not collected on factors that might help explain findings of the present analysis, such as motives for substance use. Furthermore, we did not collect information on types of chronic pain (i.e., locations or medical diagnoses). Although specific psychiatric diagnoses were extracted from patient’s charts, there was substantial variability in the coding of diagnosis based on the treating clinician, with some using specific diagnoses (e.g., major depressive disorder) and others using broad categories (e.g., mood disorder) or provisional/tentative diagnoses (e.g., major depressive disorder, provisional, rule out bipolar disorder). Thus, although we are confident in the broad designation of co-occurring psychiatric disorder, the precision of specific diagnoses and variability in language limits our ability to conduct disorder-specific analyses. The associations among pain interference and catastrophizing and polysubstance use might be stronger and statistically significant among certain subgroups, such as those with specific types of chronic pain and specific psychiatric diagnoses, which should be investigated in future studies. We also did not assess medicinal cannabis use, which may have limited the proportion of respondents endorsing cannabis use, including those who used medical cannabis in combination with other substances. Lastly, polysubstance use captured in the present analysis reflects the concurrent use of these substances, as opposed to co-ingestion. Given that co-ingestion contributes to drug overdose, future studies are needed to determine if pain interference and catastrophizing are associated with co-ingestion of substances among those with chronic pain.

In conclusion, polysubstance use was common among those with SUD and co-occurring chronic pain. We did not identify a main effect of either pain interference or catastrophizing on polysubstance use in this sample. However, pain interference had a strong positive association with polysubstance use among men and a weak positive association with polysubstance use among those with alcohol use disorder. These subgroups might benefit from intervention efforts targeting pain interference to reduce the concurrent use of multiple substances. A number of psychological treatments for pain, including mindfulness-based treatments and acceptance and commitment therapy, have demonstrated efficacy in reducing pain interference among those with chronic pain (24). Future studies should continue exploring explanations of findings in the present analysis (e.g., using multiple substances to cope with pain and related negative affect), as well as correlates of polysubstance use among women with chronic pain and those with opioid use disorder and chronic pain. It will also be important to consider more nuanced patterns of polysubstance use among this population in future work, including accounting for different combinations of substance use and frequencies of substance use. Addressing polysubstance use among those with chronic pain might have the potential to reduce pain-related distress and risk of overdose in this population.

Disclosure/Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse of the National Institutes of Health, award number T32AA018108, and the Charles Engelhard Foundation. The content is the sole responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Weiss has served as a consultant to Analgesic Solutions, Cerevel Therapeutics, and Janssen Pharmaceuticals. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.McDermott KA, Griffin ML, McHugh RK, Fitzmaurice GM, Jamison RN, Provost SE, et al. Long-term naturalistic follow-up of chronic pain in adults with prescription opioid use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;205:107675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zale EL, Maisto SA, Ditre JW. Interrelations between pain and alcohol: An integrative review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2015;37:57–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.John W, Wu L-T. Chronic non-cancer pain among adults with substance use disorders: prevalence, characteristics, and association with opioid overdose and healthcare utilization. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;209:107902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ditre JW, Zale EL, LaRowe LR. A reciprocal model of pain and substance use: Transdiagnostic considerations, clinical implications, and future directions. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2019;15(1):503–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hill KP, Palastro MD, Johnson B, Ditre JW. Cannabis and pain: A clinical review. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2017;2(1):96–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vowles KE, McEntee ML, Julnes PS, Frohe T, Ney JP, van der Goes DN, et al. Rates of opioid misuse, abuse, and addiction in chronic pain : A systematic review and data synthesis. Pain. 2015;156(4):569–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barry DT, Beitel M, Garnet B, Joshi D, Rosenblum A, Schottenfeld RS. Relations among psychopathology, substance use, and physical pain experiences in methadone-maintained patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(9):1213–1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dassieu L, Kaboré J-L, Choinière M, Arruda N, Roy É. Understanding the link between substance use and chronic pain: A qualitative study among people who use illicit drugs in Montreal, Canada. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;202:50–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Connor JP, Gullo MJ, White A, Kelly AB. Polysubstance use: diagnostic challenges, patterns of use and health. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2014;27(4):269–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paulus DJ, Rogers AH, Bakhshaie J, Vowles KE, Zvolensky MJ. Pain severity and prescription opioid misuse among individuals with chronic pain: The moderating role of alcohol use severity. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;204:107456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fernandez AC, Bush C, Bonar EE, Blow FC, Walton MA, Bohnert ASB. Alcohol and drug overdose and the influence of pain conditions in an addiction treatment sample. J Addict Med. 2019;13(1):61–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cleeland CS, Ryan KM. Pain assessment: global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1994;23(2):129–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sullivan MJL, Bishop SR, Pivik J. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale: Development and validation. Psychol Assess. 1995;7(4):524–532. [Google Scholar]

- 14.McDermott KA, Joyner KJ, Hakes JK, Okey SA, Cougle JR. Pain interference and alcohol, nicotine, and cannabis use disorder in a national sample of substance users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;186:53–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barry DT, Pilver CE, Hoff RA, Potenza MN. Pain interference and incident mood, anxiety, and substance-use disorders: Findings from a representative sample of men and women in the general population. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47(11):1658–1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blanco C, Wall MM, Okuda M, Wang S, Iza M, Olfson M. Pain as a predictor of opioid use disorder in a nationally representative sample. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(12):1189–1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wiest KL, Colditz JB, Carr K, Asphaug VJ, McCarty D, Pilkonis PA. Pain and emotional distress among substance-use patients beginning treatment relative to a representative comparison group. J Addict Med. 2014;8(6):407–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Degenhardt L, Lintzeris N, Campbell G, Bruno R, Cohen M, Farrell M, et al. Experience of adjunctive cannabis use for chronic non-cancer pain: Findings from the Pain and Opioids IN Treatment (POINT) study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;147:144–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larance B, Campbell G, Peacock A, Nielsen S, Bruno R, Hall W, et al. Pain, alcohol use disorders and risky patterns of drinking among people with chronic non-cancer pain receiving long-term opioid therapy. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;162:79–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martel MO, Wasan AD, Jamison RN, Edwards RR. Catastrophic thinking and increased risk for prescription opioid misuse in patients with chronic pain. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;132(1–2):335–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kneeland ET, Griffin ML, Taghian N, Weiss RD, McHugh RK. Associations between pain catastrophizing and clinical characteristics in adults with substance use disorders and co-occurring chronic pain. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2019;45:488–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Votaw VR, McHugh RK, Witkiewitz K. Alcohol use disorder and motives for prescription opioid misuse: A latent class analysis. Subst Use Misuse. 2019;54:1558–1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nattala P, Leung KS, Abdallah A Ben, Murthy P, Cottler LB. Motives and simultaneous sedative-alcohol use among past 12-month alcohol and nonmedical sedative users. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2012;38(4):359–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Veehof MM, Trompetter HR, Bohlmeijer ET, Schreurs KMG. Acceptance- and mindfulness-based interventions for the treatment of chronic pain: a meta-analytic review. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2016;45:5–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Turner JA, Holtzman S, Mancl L. Mediators, moderators, and predictors of therapeutic change in cognitive-behavioral therapy for chronic pain. Pain. 2007;127(3):276–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zale EL, LaRowe LR, Boissoneault J, Maisto SA, Ditre JW. Gender differences in associations between pain-related anxiety and alcohol use among adults with chronic pain. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2019;45:479–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vowles KE, Witkiewitz K, Pielech M, Edwards KA, McEntee ML, Bailey RW, et al. Alcohol and opioid use in chronic pain: A cross-sectional examination of differences in functioning based on misuse status. J Pain. 2018;19(10):1181–1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Votaw VR, Witkiewitz K, Valeri L, Bogunovic O, McHugh RK. Nonmedical prescription sedative/tranquilizer use in alcohol and opioid use disorders. Addict Behav. 2019;88:48–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bhalla IP, Stefanovics EA, Rosenheck RA. Clinical epidemiology of single versus multiple substance use disorders. Med Care. 2017;55(9):S24–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cacciola JS, Alterman AI, Dephilippis D, Drapkin ML, Valadez C, Fala NC, et al. Development and initial evaluation of the Brief Addiction Monitor (BAM). J Subst Abuse Treat. 2013;44(3):256–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McHugh RK, Geyer R, Karakula S, Griffin ML, Weiss RD. Nonmedical benzodiazepine use in adults with alcohol use disorder: The role of anxiety sensitivity and polysubstance use. Am J Addict. 2018;27(6):485–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus users guide (Version 8). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gudin JA, Mogali S, Jones JD, Comer SD. Risks, management, and monitoring of combination opioid, benzodiazepines, and/or alcohol use. Postgrad Med. 2013;125(4):115–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Riley JL, King C Self-report of alcohol use for pain in a multi-ethnic community sample. J Pain 2009;10(9):944–952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]