Abstract

Our conscious experience of the world seems to go in lockstep with our attentional focus: we tend to see, hear, taste and feel what we attend to, and vice versa. This tight coupling between attention and consciousness has given rise to the idea that these two phenomena are indivisible. In the late 1950s, the honoree of this special issue, Charles Eriksen, was among a small group of early pioneers that sought to investigate whether a transient increase in overall level of attention (alertness) in response to a noxious stimulus can be decoupled from conscious perception using experimental techniques. Recent years saw a similar debate regarding whether attention and consciousness are two dissociable processes. Initial evidence that attention and consciousness are two separate processes primarily rested on behavioral data. However, the past couple of years witnessed an explosion of studies aimed at testing this conjecture using neuroscientific techniques. Here we provide an overview of these and related empirical studies on the distinction between the neuronal correlates of attention and consciousness, and detail how advancements in theory and technology can bring about a more detailed understanding of the two. We argue that the most promising approach will combine ever evolving neurophysiological and interventionist tools with quantitative, empirically testable theories of consciousness that are grounded in a mathematically formalized understanding of phenomenology.

Introduction

Consciousness and attention are both fascinating and difficult to define. The lack of widely accepted definitions stirs frequent debate in either field of study (Block, 2005; Block et al., 2014; Krauzlis, Bollimunta, Arcizet, & Wang, 2014; Luo & Maunsell, 2019; Maunsell, 2015; Michel et al., 2019). For the purpose of this paper, we will define consciousness as subjective (phenomenal) experience. Note that this definition encompasses both levels and contents of consciousness (Bachmann & Hudetz, 2014; Hohwy, 2009), although we will mainly focus on the latter by examining empirical studies of perceptual experience. Moreover, our definition of consciousness does not rely on behavior, such as whether a particular experience can or does get reported (which some authors have distinguished as “access consciousness” or awareness (Block, 2005)). We will similarly bypass various distinctions of attention by collapsing them into the intuitive notion of mental focus on a particular aspect of information (a wide definition seems justified given recent evidence for a general attention factor (Huang, Mo, & Li, 2012)). By relying on intuition, our definition of attention thus parallels that of the father of American psychology, William James, who famously wrote that “everyone knows what attention is” (James, 1890).

Interestingly, James went on that “focalization, concentration of consciousness are of its essence”, suggesting an intricate link between consciousness and attention. In this view attention is consciousness - just more of it. The notion of attention being identical to consciousness is still favored by some (O’Regan & Noe, 2001). One argument for this view is that attending something seems to amplify consciousness, such as enhancing visual contrast sensitivity and/or perceptual appearance (M. Carrasco, 2011). However, another possible interpretation of this observation is that attention is a different process than consciousness, but interacts with consciousness in a certain way. One such view holds that consciousness is necessary for attention in that attention is a modulation of conscious experience. Thus, some authors argue that attention depends on consciousness. To others it seems similarly intuitive that conscious experience only occurs once we attend to the world around us. In that view, consciousness depends on attention, and not the other way around (M. A. Cohen, Cavanagh, Chun, & Nakayama, 2012). Finally, there is the view that attention and consciousness can be dissociated from each other (Lamme, 2004). This hypothesis is falsifiable in that it comes with several testable predictions (Koch & Tsuchiya, 2007), such as that consciousness and attention can occur independently of each other, that the effects of consciousness and attention might go in opposing directions and that the neural substrates supporting each of the two phenomena are separable. This last point shall be the central focus of this review.

Eriksen’s pioneering contributions

As outlined above, the relationship between attention and consciousness has long been a subject of debate. In some ways, this discussion can be traced back to the scientist honored by this special edition, Charles Eriksen and his seminal work on “subception” in the 1950’s and 60s. Eriksen was interested in studies where volunteers received electric shocks while nonsense syllables were presented for varying amounts of time. The initial data suggested that whether or not subjects consciously perceived the very briefly presented stimuli, repeated presentations of the same stimuli evoked a galvanic skin response, reminiscent of subjects anticipating the pain (Lazarus & McCleary, 1951). This phenomenon coined “subception” was seen as evidence that a heightened “arousal” (which, in this context, means a transient increase in alertness or unfocused attention) can be evoked in the absence of conscious perception of the stimulus that caused it (see (Robbins et al., 1998; Thiele, 2013; Tsuchiya & Koch, 2014) for more on the argument that arousal is closely related to attention; but also see (Otazu, Tai, Yang, & Zador, 2009)). Eriksen was critical of this interpretation and argued that there were shortcomings of the original study (Eriksen, 1956). As we will discuss below, several of Eriksen’s critiques such as that (verbal) reports are limited in determining consciousness (Eriksen, 1960) have re-emerged in recent years.

Behavioral evidence that attention and consciousness are dissociable

More than 40 years after Charles Eriksen’s investigation of alertness changes in the absence of conscious perception, new empirical work re-emerged that raises similar questions. In fact, the original question as to the relation of alertness and unconscious processing has been expanded and dissected in several ways: 1) Can unconscious stimuli still become the target of top-down attentional selection? 2) Can unconscious stimuli still attract attention in a bottom-up manner? And the focus of this review: 3) What are the neural correlates of unconscious stimuli that interact with attention in certain ways?

Dissociations between consciousness and attention have been demonstrated in various ways (for review, see (Cohen, Cavanagh, Chun, & Nakayama, 2012; Dehaene, Changeux, Naccache, Sackur, & Sergent, 2006; Koch & Tsuchiya, 2007; Tsuchiya & Koch, 2016). While manipulation of attention can be objectively verified through behavioral measures (e.g., decreased reaction time, improved performance), there is arguably no widely accepted norm for how to behaviorally assess conscious perception (Ramsøy & Overgaard, 2004; Seth, Dienes, Cleeremans, Overgaard, & Pessoa, 2008). While conscious experience has been largely equated with verbal reports, verbal reports are increasingly recognized as highly limited and methods for capturing richness of conscious experience (Block, 2005; Haun et al., 2017; Sperling, 1960). Recent studies even question the stringent requirement of behavioral reports, as most of our conscious experience is unreported normally and the act of reports can affect phenomenology, attention, and neural activity (M. A. Cohen, Ortego, Kyroudis, & Pitts, 2020; Koch, Massimini, Boly, & Tononi, 2016; Tsuchiya, Wilke, Frassle, & Lamme, 2015). These issues need to be taken into account when comparing results between studies.

The null hypothesis that attention and consciousness are either identical or indivisibly coupled predicts that i) there is no attention outside consciousness and ii) there is no consciousness without attention. Thus, any demonstration of either attention acting on nonconscious stimuli or consciousness occurring in the complete absence of attention are direct evidence for a possible dissociation between attention and consciousness. One evidence for a complete separation between attention and consciousness would take the form of a double dissociation, where both these phenomena (i.e., attention without consciousness and consciousness without attention) are demonstrated. Such double dissociation would suggest that attention and consciousness are two separate phenomena and they can work independently. This most powerful dissociation can be achieved by manipulating conscious visibility and attentional availability in an independent manner (with a 2 × 2 design). Using such a paradigm, several studies demonstrated dissociable behavioral or neuronal effects (Brascamp, vanBoxtel, Knapen, & Blake, 2010; Smout & Mattingley, 2018; J. J. vanBoxtel, Tsuchiya, & Koch, 2010; J. J. A. vanBoxtel, 2017; Watanabe et al., 2011). However, several of these findings have recently been challenged (Travis, Dux, & Mattingley, 2017; Yuval-Greenberg & Heeger, 2013), thus requiring further investigation.

In addition to double dissociation, there are other ways to demonstrate that attention and consciousness can be uncoupled. For example, some studies show that attention can operate outside of consciousness, or vice versa. The most robust dissociation of this kind could be summarized as “attentional effects without conscious visibility”. In these studies, sensory stimuli (typically of attentional cues) are manipulated to be either visible or invisible (Kim & Blake, 2005). Then, attentional effects are measured. If objectively measured (behaviorally or neuronally) attentional effects are constant, regardless of conscious visibility, this kind of dissociation is deemed to be established.

A more controversial dissociation is “conscious visibility regardless of attentional enhancement”. Here, attentional availability or expectation can be manipulated by dual-task designs (Matthews, Schröder, Kaunitz, Van Boxtel, & Tsuchiya, 2018), rapid serial visual presentation (or attentional blink), task instruction, or task set priming (including “inattentional blindness” or “change blindness” (M. A. Cohen, Botch, & Robertson, 2020; M. A. Cohen & Rubenstein, 2020)). If conscious visibility of a stimulus does not depend on the attentional state, the dissociation is thought to be established. A part of the associated controversy stems from the fact that attentional manipulation often accompanies the changes of stimulus input per se. This leaves the possibility that attention could “spill over” to a presumably “unattended” stimulus.

Initial evidence for a dissociation between attention and consciousness was provided by a clinical study which showed that neurological patients lacking large parts of primary visual cortex (V1) respond faster when attention is drawn to a stimulus while being unable to consciously see what evoked the change in attentional state (Kentridge, Heywood, & Weiskrantz, 1999, 2004; Schurger, Cowey, Cohen, Treisman, & Tallon-Baudry, 2008).

A similarly stunning result was found in split-brain patients whose cerebral hemispheres were surgically separated to treat severe epilepsy (Gazzaniga, 2014). An interesting consequence of the split-brain surgery is that the operated patients seem to report that their visual perception is split in half (but see: (Pinto, de Haan, & Lamme, 2017; Pinto, Lamme, & de Haan, 2017; Pinto, Neville, et al., 2017)). When these patients are asked to report their visual experience using either their left or right hand (which are controlled by the right and left hemispheres, respectively), they can only indicate whatever is shown to the left or right visual hemifields. In other words, everything that is to one side of their nose seems to be perceived by only one half of their brain and this side of their brain is completely unaware of what is shown to the other side of their nose (Volz & Gazzaniga, 2017). And yet, this is not the case for their attentional focus, which can still operate across the entire visual field (Corballis, 1995). For example, attentional cueing experiments found that when spatial cues are presented to either the left or right visual hemifield, performance is identical, suggesting that attention is a unified resource shared between cerebral hemispheres (But also see Alvarez & Cavanagh 2005 Psych Sci). This finding not only suggests that the neural substrates for consciousness and attention are separable, but that attention may be closely tied to subcortical structures.

This finding in human split brain patients are also consistent with a recent surge of primate electrophysiology research, which points to non-cortical structures, such as the superior colliculus, thalamic pulvinar nucleus, and basal ganglia as critical neural substrates for attention (Arcizet & Krauzlis, 2018; Bogadhi, Bollimunta, Leopold, & Krauzlis, 2018; Bollimunta, Bogadhi, & Krauzlis, 2018; Fiebelkorn & Kastner, 2020; Halassa & Kastner, 2017; Krauzlis, Bogadhi, Herman, & Bollimunta, 2018; Krauzlis et al., 2014; Krauzlis, Lovejoy, & Zenon, 2013; Saalmann & Kastner, 2011; Saalmann, Pinsk, Wang, Li, & Kastner, 2012; Zenon & Krauzlis, 2012). Attention thus might have a more expansive subcortical basis than previously appreciated. Accordingly, severing interhemispheric cortical connections in split brain patients may have less of an impact on attention (which in some ways remains intact) than on conscious perception (which appears to be split in half, or otherwise diminished). However, note that there is also emerging evidence that certain subcortical structures, such as higher order nuclei of the thalamus play a crucial role for both levels as well as contents of consciousness (Donoghue et al., 2019; Redinbaugh et al., 2020; Schmid & Maier, 2015; Wilke, Mueller, & Leopold, 2009). Thus, while these novel findings point at dissociable neural processes for attention and consciousness, it is not as simple as attention being a subcortical phenomenon and consciousness a product of the neocortex.

Following up on these seminal studies in the blindsight and split-brain patients, a large number of studies performed on healthy observers established that attention can be captured outside of consciousness (Faivre & Kouider, 2011; Kentridge, Nijboer, & Heywood, 2008; Kiefer & Martens, 2010; Martens, Ansorge, & Kiefer, 2011; Sumner, Tsai, Yu, & Nachev, 2006). Based on these and other evidence (for further recent updates, see (Tsuchiya & Koch, 2016)), largely speaking, there is a strong agreement in the field that consciousness is not necessary for attention, but whether attention is necessary for consciousness continues to be debated (M. A. Cohen et al., 2012; Michael A Cohen, Dennett, & Kanwisher, 2016; Dehaene, Changeux, Naccache, Sackur, & Sergent, 2006; vanBoxtel, Tsuchiya, & Koch, 2010a).

Neuroscientific approaches to study the attention/consciousness divide

One of the most impactful propositions in recent years that was derived from this empirical work has been the hypothesis that neuronal mechanisms that support consciousness and attention can work independently and be dissociated from each other (Koch & Tsuchiya, 2007, 2012; Lamme, 2003, 2004). When originally formulated, this hypothesis mostly rested on behavioral data since there were few studies at the time testing for separate neural substrates (but see (Wyart & Tallon-Baudry, 2008)). This situation has changed drastically during the past years, with several independent groups investigating whether attention and consciousness can be disassociated not only in behavioral terms, but also in their underlying patterns of cortical activation (Nani et al., 2019). This empirical test is important in the attempt to falsify the original dissociation hypothesis: If there were no distinction in the brain activation patterns for attention and consciousness, it seems implausible for attention and consciousness to be supported by distinct neural mechanisms. In what follows, we will review several neuroimaging and neurophysiological studies in order to determine whether or not consensus has emerged across the various experimental approaches taken to date.

fMRI evidence for a separation between consciousness and attention

Functional magnetic resonance imaging non-invasively yields sub-centimeter localization of brain function across the entire brain. However, this fine-grained global coverage comes at the cost of a rather poor temporal resolution of several seconds. Despite these technical limitations, recent fMRI studies have been pivotal in demonstrating that attention can increase neural response to invisible stimuli. And thanks to the spatial resolution of fMRI, such effects could be located in distinct parts of the brain, such as the visual cortex (e.g., V1) (Watanabe et al., 2011).

fMRI even produced evidence pointing at a dissociation between attention and consciousness (Kouider, Barbot, Madsen, Lehericy, & Summerfield, 2016): Whether or not subjects consciously saw a stimulus yielded a larger or smaller fMRI response, respectively. Similarly, whether they attended a stimulus or not (in this particular case, whether they were trying to detect a certain stimulus type or not) produced somewhat smaller changes in fMRI response. Importantly consciousness can have that effect even when keeping attention unaltered, and vice versa (Figure 1a - note the difference in units on the ordinate) (Kouider et al., 2016)).

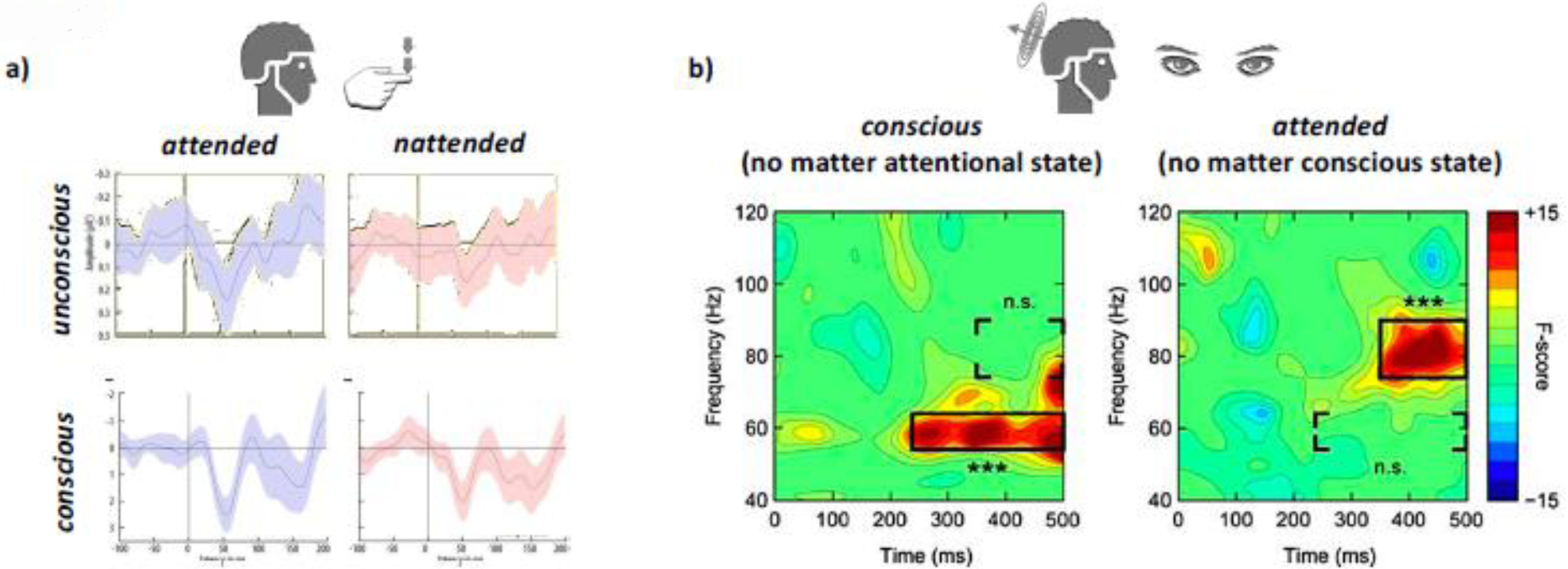

Figure 1.

fMRI and EEG evidence for separate neuronal processes underlying attention and consciousness. a) fMRI study showing that, while attention increases neuronal response magnitudes independently of whether a stimulus reached conscious perception, the larger difference in neuronal activity is related to whether a subject was conscious or unconscious of that stimulus (note the difference in units on the y-axis). b) EEG response magnitudes to conscious and unconscious stimuli in the presence or absence of attention, showing a similar effect as a). c) EEG responses to conscious (magenta) vs. unconscious attentional (cyan) cues. Note that even a cue that is not consciously perceived evokes an elevated (albeit somewhat smaller). EEG response, indicating attentional enhancement of neuronal responses.

An even more striking dissociation was found after distinguishing between different kinds of attention. There are many different ways in which attention can be elicited, such as a subject’s behavioral goals (goal driven, or endogenous attention) or by salient stimulus events (stimulus driven, or exogenous attention). Comparing the whole-brain activation pattern evoked by endogenous attention to the brain activation linked to a threshold stimulus reaching consciousness revealed a surprisingly small overlap; the thalamus was the only part of the brain that showed a statistical interaction between these two phenomena (Chica, Bayle, Botta, Bartolomeo, & Paz-Alonso, 2016).

Finally, combined with a refined behavioral control, fMRI can localize a brain region which is involved in either attention or consciousness, but not the other. For example, Webb and colleagues first established behavioral effects induced by visible and invisible attentional cues. Under these equivalent attentional conditions, they demonstrated that the brain area that remains modulated by stimulus visibility was the temporo-parietal junction (TPJ) (Webb, Igelstrom, Schurger, & Graziano, 2016). While Webb’s finding is at odds with previous literature claiming that the TPJ is modulated by attention (e.g. (Han & Marois, 2014)), we would like to point out that most studies performed prior to 2000 rarely made any effort to keep attentional effects constant while changing consciousness. Webb et al.’s findings thus suggests that older neuroscientific studies that reached conclusions regarding either consciousness or attention without varying one of these factors while keeping the other constant, might need to be re-examined.

EEG/MEG evidence for a separation between consciousness and attention

In contrast to fMRI, the electro/magneto-encephalogram (E/MEG) - the other widely used non-invasive technique - does not allow for precise localization of neural activity in space. But E/MEG has an exquisite temporal resolution. It thus can provide complementary evidence to fMRI on the question of attention and consciousness operating independently of each other.

Somatosensory stimulation (touch) of fingers, for example, can be applied to participants right at the threshold of conscious perception. Such weak stimuli are consciously perceived or not, depending on each trial. Under these circumstances, physically identical stimuli evoke a greater EEG response when they produce a conscious touch sensation (Figure 2a). Subjects then can be tasked to either attend the stimulated fingers or attend elsewhere. If the neural mechanisms supporting attention and consciousness were inseparable, there should be no effect of attention on the EEG response when the stimuli went undetected. Yet, attention increases the EEG magnitude even to unconscious stimuli (Forschack, Nierhaus, Muller, & Villringer, 2017). In other words, the somatosensory EEG response follows a 2 × 2 dissociation (conscious/unconscious vs. attended/unattended) matrix (Figure 2a), similar to what was found across behavioural studies (Tsuchiya & Koch, 2016).

Figure 2.

Double dissociations between attention and consciousness demonstrated using E/MEG. a) EEG responses to tactile stimuli that were either consciously perceived or not (y-axis) and at the same time either attended or not (x-axis, red vs. blue). Note that each of these combinations yielded a different EEG response magnitude. b) Spectral profiles of MEG responses to consciously perceived vs. unconscious visual stimuli (left), independent of attentional state and attended vs. unattended stimuli, independent of conscious state (right). Note the difference in frequency and onset for the power maxima of each of the two contrasts.

Analogous work in the visual domain produced similar results (Chica, Lasaponara, Lupianez, Doricchi, & Bartolomeo, 2010; Wyart & Tallon-Baudry, 2008). In the study by Wyart and Tallon-Baudry, participants viewed faint visual patterns that hovered around the perceptual threshold, thus consciously seeing it only about half of the time. Critically, in 50 % of trials subjects attended the screen location where the target images were shown and in the other 50 % of trials they attended elsewhere. The authors then compared instances when subjects attended to stimuli which were either seen or unseen, and stimuli which were visible when attended vs. unattended. This study used magnetoencephalography (MEG), which is believed to be more sensitive to deeper (folded) parts of the cortex than EEG. (Figure 2b). Even more noteworthy, MEG is sensitive for brain activity across a wide range of frequencies. Thus, this study was able to go beyond investigating the mere magnitude of brain responses. The authors found that consciousness was correlated with changes in low gamma activity (55–65Hz) while attention related more to high gamma (75–90Hz) frequencies instead (Wyart & Tallon-Baudry, 2008). A similar spectral dissociation between conscious perception and attention has been found in patients with V1 lesions (Schurger et al., 2008). What is more, there was a difference in onset of the neural activity related to attention and the neural responses correlating with consciousness, with attention lagging conscious perception. Other studies (by the same authors) studying the magnitude of the responses rather than their spectral profile found a similar asynchrony between attention and consciousness, albeit in the reverse order (Wyart, Dehaene, & Tallon-Baudry, 2011).

Attention-related EEG components were also observed both when observers consciously experienced attention-directing cues and when they failed to do so (Travis, Dux, & Mattingley, 2019). However, the magnitude of this attention signal was diminished when the cue was invisible (Figure 1c) (Travis et al., 2019). Several other studies convergingly suggest that attention can modulate EEG responses even if stimuli do not reach consciousness (Kiefer & Brendel, 2006; Koivisto & Revonsuo, 2007, 2008; Koivisto, Revonsuo, & Lehtonen, 2006; Sanchez-Lopez, Savazzi, Pedersini, Cardobi, & Marzi, 2019; Woodman & Luck, 2003).

On the flip side, neural correlates of consciousness have been observed independently of attentional state (Boehler, Schoenfeld, Heinze, & Hopf, 2008; Koivisto et al., 2006). When attention and consciousness of stimuli are independently manipulated, both attention and consciousness of stimuli can enhance brain responses (Figure 1b). Importantly, the general pattern emerging from these studies is that each of these response enhancements can be evoked in the absence of the other or additively superimposed (Figure 3a).

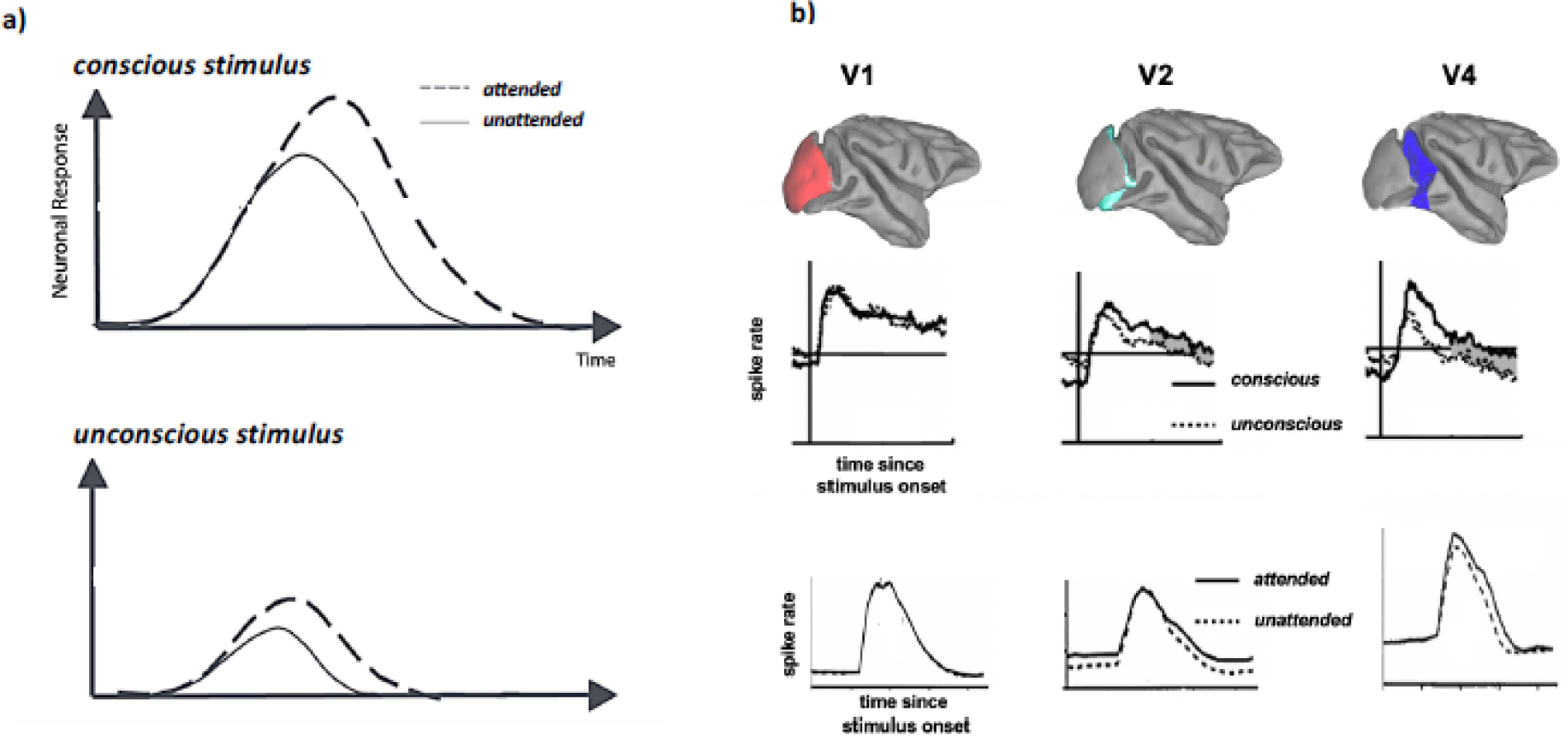

Figure 3.

a) Schematic summary of the effects of attention and conscious state on the magnitude of large-scale sensory brain responses (modified from (Koivisto & Revonsuo, 2008)). b) summary of the effects of attention and conscious state on the magnitude of large-scale sensory brain responses. Specifically, results are depicted from two single-neuron recording studies that measured the effects of conscious perception (from (David A Leopold, Maier, Wilke, & Logothetis, 2005), modified) and attentional selection (from (Luck et al., 1997), modified) in the visual cortex of macaque monkeys. Note the similar pattern of enhanced responses co-varying with either phenomenon. Also note that that the magnitude of these enhanced responses varies considerably between cortical areas (i.e., increasing from early sensory cortex towards associative cortex). What is not shown are other changes at the single-neuron level that have been associated with the phenomena, affecting correlated activity, changes in neural noise, intra- and inter-areal coherence and changes in oscillatory activity, some of which cannot be observed when studying single neurons in isolation. Also note that these data sample neurons across entire cortical areas without regard to differences in cell type or neural circuitry (such as cortical layers) that they are embedded in (see (Maier et al., 2007; Sheinberg & Logothetis, 1997) for a sample of various types of single neuron correlate of consciousness). Thus, the neuronal concomitants of both consciousness and attention are likely more than a simple “boost” in neuronal activity, but rather constitute a complex arrangement of neural mechanisms with distinct regional characteristics.

Two noteworthy recent EEG studies are opening exciting new directions towards studying the dissociation of attention and consciousness. The first study focused on the dissociation of attention and consciousness in terms of the temporal rhythms at which they operate. Recent evidence suggests that various measures of task performance tend to oscillate at either theta- (~7Hz) or alpha- (~10Hz) rhythms, implicating a rhythmic structure to perception (VanRullen, 2016), attention (Helfrich et al., 2018; Kienitz et al., 2018; Landau & Fries, 2012) or both. Davidson and colleagues (Matthew J Davidson, Alais, vanBoxtel, & Tsuchiya, 2018) investigated these rhythms in a binocular rivalry paradigm, where each eye’s view is confronted with a drastically different stimulus and perception alternates between them (Blake & Logothetis, 2002; Maier, Panagiotaropoulos, Tsuchiya, & Keliris, 2012). They found that attentional cueing during binocular rivalry induces rhythmicity, around 3.5Hz or 8Hz, in terms of conscious perceptual alternations (see also (Cha & Blake, 2019)). Importantly, the cue was either congruent with the visible or invisible stimulus (Lunghi, Morrone, & Alais, 2014). When the cue was congruent with the visible stimulus, it transiently increased 8Hz rhythms of perceptual alternations, whereas the incongruent cue increased perceptual alternations at 3.5Hz. To explain the latter finding, the authors hypothesized that attentional sampling at 8Hz can be performed between conscious and nonconscious stimuli, resulting in half the attentional sampling speed. This is a novel form of dissociation between attention and consciousness that warrants further investigation.

Furthermore, Davidson et al performed simultaneous EEG recordings during the rivalry task. Their intertrial phase coherence (ITPC) analyses at 3.5Hz and 8Hz at the scalp EEG showed that the strength of the ITPC evoked by the attentional cues was correlated with the behaviorally observed perceptual rhythms. Specifically, parieto-occipital electrodes showed 8Hz ITPC, which correlated with the 8Hz rhythmic perceptual reversals, while fronto-temporal showed 3.5Hz ITPC, which correlated with attentional effects to the invisible stimulus. This finding seems consistent with the recently proposed role of theta activity in the fronto-parietal attention network in exploration and environmental sampling (Fiebelkorn & Kastner, 2019). To date, such dissociation between consciousness and attention in the temporal domain are still relatively scarce (but see: (Naccache, Blandin, & Dehaene, 2002)), but this research line marks a promising future direction, particularly when utilizing the excellent temporal resolution of E/MEG.

The other notable EEG study utilized temporally modulating stimuli to evoke a steady-state visually evoked potential (SSVEP) (Norcia, Appelbaum, Ales, Cottereau, & Rossion, 2015; Smout & Mattingley, 2018; Vialatte, Maurice, Dauwels, & Cichocki, 2010). SSVEP are used to “frequency-tag” stimuli by turning them on an off at distinct flicker frequencies. Since neurons are expected to respond in synchrony with the on- and offsets of flickering stimuli, this frequency tagging improves the stimulus-selectivity of EEG responses by characterizing stimulus-specific neural responses in the frequency-domain. Critically, the strength of SSVEPs have been used extensively as a correlate of both the focus of attention without overt responses (Morgan, Hansen, & Hillyard, 1996; Muller et al., 2006), as well as the contents of consciousness during changes in perception (Brown & Norcia, 1997; Lansing, 1964).

Davidson and colleagues (Matthew J Davidson, Mithen, Hogendoorn, van Boxtel, & Tsuchiya, 2020) adapted a display where SSVEP stimuli faded from view due to visual adaptation (see also (M. J. Davidson, Graafsma, Tsuchiya, & van Boxtel, 2020; Schieting & Spillmann, 1987; Weil, Kilner, Haynes, & Rees, 2007)). Intriguingly, this perceptual fading is known to be enhanced by attention, in that attending to flickering stimuli results in more rapid and more frequent disappearance (DeWeerd, Smith, & Greenberg, 2006; Lou, 1999). This remarkable “negative” effect of attention on consciousness has been also reported for other phenomena, such as motion induced blindness (Geng, Song, Li, Xu, & Zhu, 2007; Scholvinck & Rees, 2009) and negative afterimages (J. W. Brascamp, van Boxtel, Knapen, & Blake, 2010; Lou, 2001; Suzuki & Grabowecky, 2003; vanBoxtel, Tsuchiya, & Koch, 2010b). Davidson et al. found that perceptual fading of the flickering stimulus was accompanied by an increase of the SSVEP signal at the frequency which tagged the disappearing stimulus. At the same time, alpha-band activity (8–12Hz), whose diminishment is commonly seen as an index of the attentional orienting (D’Andrea et al., 2019; Gould, Rushworth, & Nobre, 2011; Horschig, Oosterheert, Oostenveld, & Jensen, 2015; Jensen, Gips, Bergmann, & Bonnefond, 2014; Spaak, Bonnefond, Maier, Leopold, & Jensen, 2012), decreased at the time of target disappearance. This study raises an interesting question regarding two common assumptions about consciousness and attention. First, given that target disappearance increased the strength of stimulus-specific neural responses, the notion that consciousness is always accompanied by enhanced neuronal responses needs to be refined (see also (Merten & Nieder, 2012) and next section). Second, previous SSVEP experiments that aimed to tag the neural correlates of consciousness (Brown & Norcia, 1997; Tononi, Srinivasan, Russell, & Edelman, 1998) might have inadvertently tagged the neural correlates of attention instead (see also (P. Zhang, Jamison, Engel, He, & He, 2011)).

These new advances in empirical studies are prompting a revision of the theoretical models of consciousness (see below).

Single neuronal activity correlates with attention and consciousness in a distinct manner

All of the studies summarized so far were based on non-invasive techniques that can readily be used for human subjects, yet lag either in temporal or spatial resolution. One way to circumvent these methodological constraints is to resort to invasive techniques in animal models. Non-human primates in particular offer phylogenetic (and thus neuroanatomical) closeness (Dougherty, Schmid, & Maier, 2018; Kaas, 2012a, 2012b, 2013), the ability to apply complex (non-verbal) cognitive tasks suited for the study of attention (Bosman et al., 2012; Luck, Chelazzi, Hillyard, & Desimone, 1997; Maunsell, 2015; Mitchell, Sundberg, & Reynolds, 2009; Pooresmaeili, Poort, Thiele, & Roelfsema, 2010) and consciousness (D. A. Leopold, Maier, & Logothetis, 2003) as well as a greater spectrum of invasive techniques, such as the neurophysiological measurement of action potentials that can be linked back to one or more brain cells (Roelfsema & Treue, 2014). One of the downsides of choosing this approach is the associated cost in labor-intensive work that results in long time spans from experimental planning to data collection and analysis (typically years). Perhaps as a result of this, we are not aware of any published neurophysiological studies that examined neuronal activity related to consciousness and attention while manipulating both independently of each other. There is, however, a large body of studies that examined each of these phenomena in isolation (e.g., Figure 3b).

Interestingly, the single neuron data collected in animals parallels the human studies summarized above in that they suggest that i) both attention and consciousness correlate with increased brain activity and ii) consciousness correlates with a bigger increase in brain activity compared to attention (Figure 3b). Indeed, most studies studying either phenomenon in isolation found a similar general trend of enhanced neuronal responses across both cortical and subcortical structures when subjects are conscious (as opposed to unconscious) of a sensory stimulus (Mashour, Roelfsema, Changeux, & Dehaene, 2020; Noy et al., 2015; but also see (Logothetis, 1998). When a stimulus is attended, similar, but more modest boosts in neuronal responses are typically observed. (Maunsell, 2015). However, this is not always the case. Recent work demonstrated that under some circumstances, the exact opposite can be found (Matthew J Davidson, Mithen, Hogendoorn, vanBoxtel, & Tsuchiya, 2020; Merten & Nieder, 2012). One way to explain these apparent discrepancies are regional differences in the brain. For example, while reward tends to elevate spiking responses across most of the neocortex, including most visual cortical areas, area V4 seems to show the inverse pattern. At least during some tasks, whenever subjects learn that they will be receiving reward, V4 neurons undergo profound suppression (the larger the expected reward, the deeper the suppression) (Shapcott et al., 2020). During binocular rivalry, ~20% of recorded neurons in V4 and MT also show decrease of firing rate when the preferred stimuli are consciously experienced by the monkeys (Logothetis, 1998). This see-saw pattern of neuronal responses is also seen on a larger scale for the so-called default mode network. Generally speaking, neuronal activity increases across a wide array of cortical areas when subjects engage in a task (e.g., (Lundqvist, Bastos, & Miller, 2020)). In contrast, the default mode network, a collection of distinct frontal and parietal regions, are more active when a subject is resting idly compared to being actively engaged in a task (Hayden, Smith, & Platt, 2009; Raichle, 2015).

A final consideration is that attention-related increases in spiking magnitude are only part of the story (Luo & Maunsell, 2019). Attentional selection is further accompanied by changing levels of neuromodulators (Thiele, 2013), neural synchrony and/or oscillatory activity (Fries, Reynolds, Rorie, & Desimone, 2001)(Bosman et al., 2012; Ruff & Cohen, 2014) and changes in effective connectivity (vanKempen et al., 2020). While there is some paralleling evidence (Sewards & Sewards, 2001), less is known about the role of these phenomena for consciousness {Gaillard 2008 PLoS Bio}.

Future research promises a more granular dissection of consciousness and attention

By focusing on tractable questions, the neuroscience of consciousness has made tremendous advances during the past two decades (Boly et al., 2013; Koch, Massimini, Boly, & Tononi, 2016; Mashour et al., 2020). One of these questions that seems close to consensus is whether conscious perception and selective attention are supported by two distinct brain mechanisms. Both the behavioral as well as the neuroscientific evidence, as reviewed in this article, leans increasingly towards the affirmative. The neural responses related to attention and consciousness seem distinct in magnitude, spectral properties and at least to some degree in their spatial extent across the brain. This consensus opens more questions. Among these questions is how the neural correlates of consciousness and attention differ between different parts of the brain. Exactly which neural structures are involved in giving rise to consciousness and attention is still unclear, especially when moving from a more global perspective to the scale of neural circuits and cell types. This question is unlikely to be answered using only non-invasive techniques which are limited in either spatial or temporal resolution.

Outlook1: Technological developments for further refining our understanding of the neuronal substrates of consciousness and attention

Two recent developments are particularly promising in that regard. First, thanks to the success of deep brain stimulation, there is an ever-increasing number of people who live for extended periods of time with chronic electrode implants in their brains. This development goes hand-in-hand with invasive neurophysiological recordings that provide resolution at the level of single neurons becoming increasingly commonplace in human neurological patients (Aquino et al., 2020; Isik, Singer, Madsen, Kanwisher, & Kreiman, 2018; Kreiman, Koch, & Fried, 2000; Pryluk, Kfir, Gelbard-Sagiv, Fried, & Paz, 2019; Rees, Kreiman, & Koch, 2002; Rutishauser et al., 2013; Rutishauser et al., 2015). Given this trend, it seems increasingly likely that we are facing a future where neurophysiological implants are used in healthy individuals (Musk, 2019).

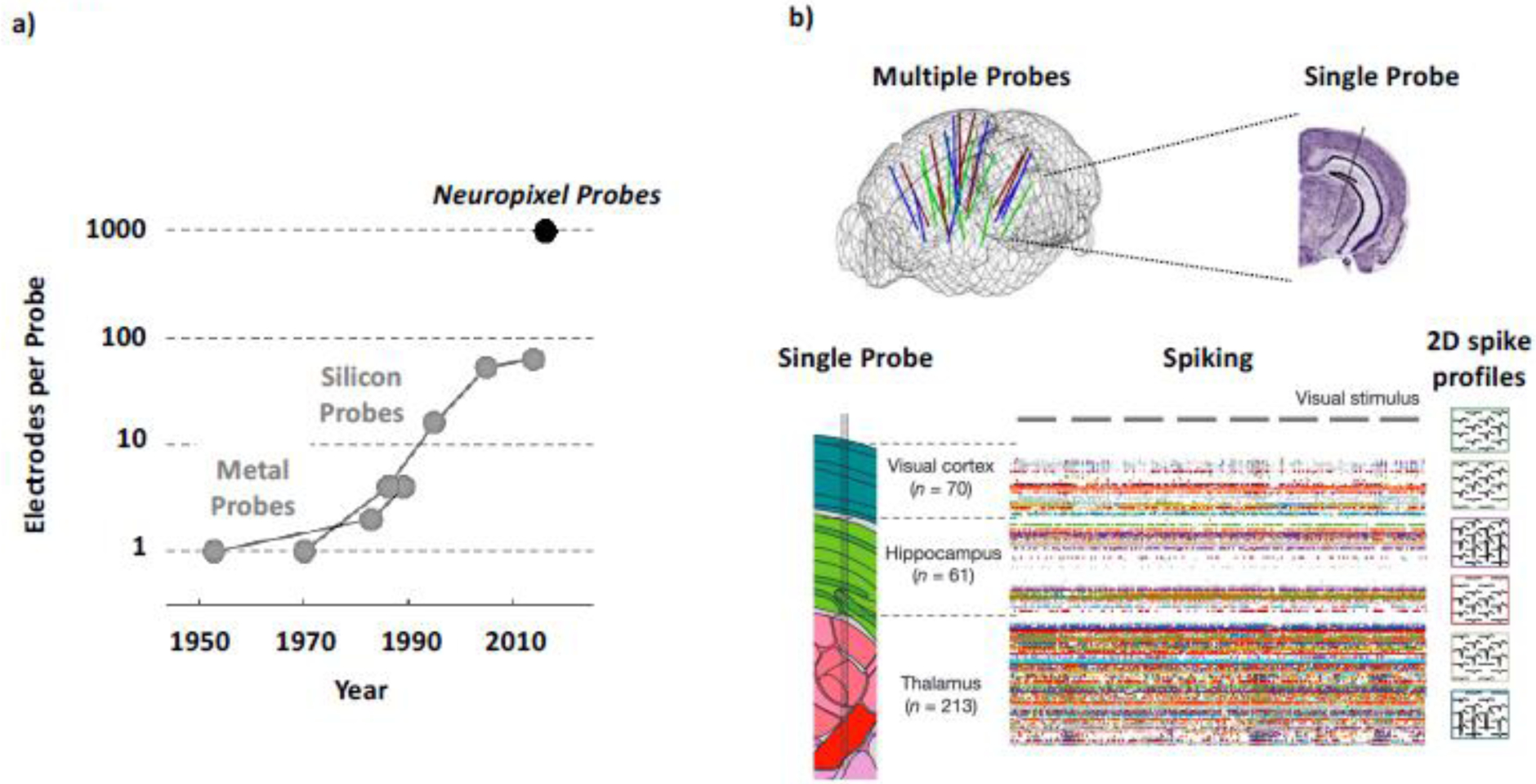

A second, related, technological breakthrough is the rapid ascent of silicone-based microelectrode arrays that provide real-time microscopic (i.e., single-neuron) resolution across several centimeters (Jun, Steinmetz, Siegle, Denman, Bauza, Barbarits, Lee, Anastassiou, Andrei, Aydin, Barbic, Blanche, Bonin, Couto, Dutta, Gratiy, Gutnisky, Hausser, Karsh, Ledochowitsch, Lopez, Mitelut, Musa, Okun, Pachitariu, Putzeys, Rich, Rossant, Sun, Svoboda, Carandini, Harris, Koch, O’Keefe, et al., 2017; Musk, 2019; Steinmetz, Koch, Harris, & Carandini, 2018). In other words, thanks to modern electrode design and technology together with advances in computing power, big data storage and machine learning-based analyses (Pachitariu, Steinmetz, Kadir, Carandini, & Harris, 2016), it has become feasible to simultaneously record thousands of neurons across a wide array of subcortical and cortical areas (Jun, Steinmetz, Siegle, Denman, Bauza, Barbarits, Lee, Anastassiou, Andrei, Aydin, Barbic, Blanche, Bonin, Couto, Dutta, Gratiy, Gutnisky, Hausser, Karsh, Ledochowitsch, Lopez, Mitelut, Musa, Okun, Pachitariu, Putzeys, Rich, Rossant, Sun, Svoboda, Carandini, Harris, Koch, O’Keefe, et al., 2017; Musk, 2019; Steinmetz et al., 2018; Steinmetz, Zatka-Haas, Carandini, & Harris, 2019; Stringer, Pachitariu, Steinmetz, Carandini, & Harris, 2019). It is hard to overestimate the quantum leap that has been achieved using this approach (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Promising new technological developments. a) Recent years witnessed a “quantum leap” in the count of simultaneously placed microelectrodes used in animal studies (from (Steinmetz et al., 2018), modified). b) This massive increase in the simultaneously measured activity of single neurons allows for more global (across-the-brain) measures at a sub-millisecond and sub-millimeter resolution. Given the spatio-temporal complexities associated with the neural concomitants of consciousness and attention (Figure 3), this unprecedented combination of macroscopic scale and microscopic resolution promises a host of new insights beyond current methodological constraints from (Stringer, Pachitariu, Steinmetz, Reddy, et al., 2019) and (Jun, Steinmetz, Siegle, Denman, Bauza, Barbarits, Lee, Anastassiou, Andrei, Aydin, Barbic, Blanche, Bonin, Couto, Dutta, Gratiy, Gutnisky, Hausser, Karsh, Ledochowitsch, Lopez, Mitelut, Musa, Okun, Pachitariu, Putzeys, Rich, Rossant, Sun, Svoboda, Carandini, Harris, Koch, OKeefe, et al., 2017), modified.

Up until now, as we reviewed in the above sections for E/MEG and fMRI, neuroimaging techniques have sacrificed either spatial or temporal resolution when trying to cover the entire brain. Only by substantially limiting the spatial coverage, electrophysiological measures were able to get to the resolutions of single neurons. Thanks to these new electrode arrays, we can now study single neuron activity across large parts of the brain with sub-millisecond resolution. More than that, due to the large number (hundreds to thousands) and high spatial resolution (less than tens of microns) of electrodes on these silicon probes, the spiking activity of hundreds of neurons recorded simultaneously can now be sampled in a 2D spatial mosaic consisting of multiple adjacent microelectrodes. The resulting spatial profile of action potentials can be used to create an “electromorphological” fingerprint to identify and classify different neuron types using in vivo extracellular neurophysiology in a previously unprecedented way (Jia et al., 2019).

So, what do these technological advances offer for our understanding of the neural basis of consciousness and attention? The massive increase in electrode count currently underway in the field of neurophysiology is more than just a quantitative advance, but it marks the dawn of a qualitatively new advance in assessing brain activity. The implications are manifold, but immediately apparent for the question at the heart of this review. Both consciousness and attention arise from the activity of neurons that are widely dispersed across the brain. Whether neurons that support these phenomena differ biochemically (or not (Maier, Logothetis, & Leopold, 2007)), morphologically, or in any other physical characteristic from neighboring neurons is still unknown, as is the question of how far the neural populations supporting consciousness and attention overlap. More importantly, rather than being limited to studying isolated neurons, neurophysiology is now entering a phase where entire neural circuits, spanning cortical layers, areas and nuclei are measured without sacrificing either spatial or temporal resolution (i.e., we are now studying brain activity at the macro- and mesoscale with microscale resolution).

With this technological advance, comes increased need for a quantitative theory of consciousness and attention. We particularly need a theory that not only manages to explain the conceptual advances outlined above, but that can also provide empirically testable and non-trivial (e.g., counterintuitive) predictions on consciousness and attention. Such theoretical guidance will promote the targeted and theory-driven data collection to specifically test hypotheses on the brain mechanisms of consciousness and attention. With a successful marriage of theory and empirical experiments, we are poised to gain unprecedented new insight in these phenomena at the neuronal circuit-level (see below).

Outlook 2: Developments towards an empirically-testable quantitative science of phenomenology

Along with the above-mentioned technological breakthroughs, we also need to make conceptual breakthroughs to make real progress in our understanding of the neural basis of consciousness and attention.

First of all, the full potential of these new invasive neuroscientific techniques will be at least initially primarily available in animals. Therefore, we urgently need to develop improved experimental paradigms that can distinguish consciousness and attention in the absence of verbal communication, such as no-report paradigms (Frassle, Sommer, Jansen, Naber, & Einhauser, 2014; D. A. Leopold et al., 2003; Tsuchiya, Wilke, Frassle, & Lamme, 2015; Wilke et al., 2009). Indeed, studies that eliminated overt behavioral reports during experimental investigations of conscious perception have revealed that part of what have previously been deemed the neural correlates of consciousness (NCC) may actually be brain activity related to the planning and execution of behavioral reports (Aru, Bachmann, Singer, & Melloni, 2012; DeGraaf, Hsieh, & Sack, 2012; Tsuchiya et al., 2015). This has been an important step in narrowing down which neural responses are truly consciousness-related, as there are arguably many additional processes that are engaged in the brain, once, and only if, consciousness has changed (attention being one of them). The no-report approach to eliminating downstream processes of the NCC thus is in some way comparable to the use of bistable (also called multistable) stimuli, which allows researchers to keep sensory stimulation constant while perception varies in order to eliminate low-level responses upstream of the NCC (J. Brascamp, Sterzer, Blake, & Knapen, 2018; Frith, Perry, & Lumer, 1999; Lumer, Friston, & Rees, 1998).

No report paradigms have raised interesting questions regarding the relationship between attention and consciousness (M. A. Cohen, Ortego, Kyroudis, & Pitts, 2020; Frassle et al., 2014; Montemayor & Haladjian, 2019; Wilke et al., 2009). For example, eliminating report also challenges whether the (low frequency) gamma activity that has been associated with consciousness might be related to post-perceptual decision making and/or motor planning instead (Pitts, Padwal, Fennelly, Martinez, & Hillyard, 2014). No report paradigms pose certain challenges for experiments that seek to dissociate attention from consciousness in that report is often used to control attentional state. It thus has been difficult so far to combine both approaches. Future experiments will likely fill this increasingly pressing knowledge gap.

While animal studies with massive neural recordings and more sophisticated behavioral paradigms will undoubtedly play a critical role in advancing our understanding of the neural mechanisms of consciousness and attention, human studies will also need to become more quantitatively sophisticated to promote our understanding of the structure of conscious phenomenology. In general, consciousness researchers painfully know how little we understand the structure of consciousness, but this issue has been largely neglected in the last decades due to the immense advance in the side of neuroscience of consciousness. Indeed, we foresee further developments of psychophysics. For example, studies of consciousness and attention based on the phenomenon of “change blindness” can benefit from powerful sensory manipulations using virtual reality (M. A. Cohen, Botch, & Robertson, 2020). The relationship between consciousness and attention in everyday life could be probed with wearable devices used for experiential sampling (Kahneman, Krueger, Schkade, Schwarz, & Stone, 2004; Killingsworth & Gilbert, 2010) that are combined with wearable devices that take neural measurements (Casson, 2019). Another direction of future psychophysical work might utilize big data analysis and massive scale recruitment of participants online (Bridges, Pitiot, MacAskill, & Peirce, 2020; Crump, McDonnell, & Gureckis, 2013; Sheehan, 2018). These techniques can overcome limitations of traditional “button press” psychophysical experiments that are too restrictive to fully characterize the rich nature of conscious phenomenology (Varela, 1996; Zahavi & Gallagher, 2008). While richer descriptions of conscious phenomenology through extensive verbal reports or subjects’ drawings have been utilized in important case reports, as in neglect patients (Bisiach & Luzzatti, 1978), this approach has not been fully utilized in various research domains pertaining to consciousness and attention (Haun, Tononi, Koch, & Tsuchiya, 2017; Fei-Fei, Iyer, Koch, & Perona, 2007).

A particularly exciting promising development in this regard is the rapidly emerging research program that aims to uncover and mathematically formalize isomorphisms between the structure of conscious phenomenology and the structure of information that is inherent in neuronal activity (Figure 5). While there is a surface resemblance to studies that aim to uncover the NCC, this new line of research adds emphasis on structure (i.e., relative distances of states in both experiential and neuronal space). For example, a common approach to test whether a particular set of neurons belonged to the NCC is to keep sensory inputs constant while phenomenology is changing (Frith et al., 1999). This paradigm has been successfully applied to determine whether certain neurons and what aspect of neuronal responses correlate with consciousness (see (D. A. Leopold & Logothetis, 1999; Michel et al., 2019; Parker & Newsome, 1998) for review). The promising next step is to focus on the structural relations that exist within phenomenology, such as the phenomenon that tones of certain frequency ratios (e.g., musical notes of the same chroma (Shepard, 1982)) sound more similar than other tones or the fact that visual stimuli are located relative to each other in visual space. This novel approach subsumes prior work on the NCC, and extends that line of research to study different sensory inputs that evoke similar phenomenology, such as short and long wavelengths of light evoking the perception of purple and red, which are phenomenologically more similar than the colors evoked by physically more similar wavelengths.

Figure 5.

Promising new theoretical directions. A possible research program for the search of an isomorphism between the structure of consciousness and the structure of information derived from the activity and structure of the neuronal activity. First, phenomenological structure needs to be precisely mapped out. As one possible mapping strategy, we can start with characterizing phenomenological relationships between various sounds (e.g., C major chords), as shown here, as well as conscious sensations in other modalities. Attention can be used here as a way to “perturb” phenomenology. These relationships can be quantified and mathematically expressed (e.g., in a multidimensional space through large-scale similarity rating experiments or in other ways using topology or category theory). Here, relationships among variously pitched tones are represented as a helix of musical “chroma” (Shepard, 1982), which captures the essential phenomenological feature of two tones that sound “similar but different”. At the neuronal side, connectivity and activity states of the neural networks are measured, and mathematically abstracted to propose physical structures (e.g., informational structure in IIT) that are supposed to give rise to the specific conscious experience. A search for an isomorphism starts with a unidirectional correspondence from one structure to the other (see main text). When both directions converge, we get closer to an isomorphic law that bridges between consciousness and brain activity. Attentional manipulation should preserve this isomorphism. That is, attention cannot change phenomenal structure without changing the information structure set up by neuronal activity, and vice versa. Brain icon is modified from James.mcd.nz, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International, 3.0 Unported, 2.5 Generic, 2.0 Generic and 1.0 Generic license (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Brain_Surface_Gyri.SVG). The icon representing the information structure is modified from Takemori39, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Network_self-organization_stages.png).

Figure 5 provides a conceptual schematic for this approach. For example, the phenomenological relationship between two types of sounds (e.g., C major chords), and the relationships among various other sounds (as well as conscious sensations in other modalities) can be quantified and mathematically expressed in a multidimensional space through large-scale similarity rating experiments and other yet-to-be developed techniques. The derived mathematical structure of certain types of phenomenological experience (here the helix of musical “chroma” that symbolizes the relationship between sounds of different pitch that makes them appear “similar but different”) will serve as a reference (Figure 5, upper row). At the same time, connectivity and activity states of the neural networks that give rise to this conscious experience need to be measured, mathematically quantified and characterized (Figure 5, bottom row).

It seems parsimonious to assume that a close relationship between two phenomenological states arises from similar closeness of underlying neuronal states. In other words, on some level there should be an isomorphic relationship between the (differences in) neuronal space and the (differences in) phenomenological space - two sounds that sound similar are accompanied by similar neural activity. However, neither of these two spaces seem to be simple, Euclidian vector spaces. Phenomenological space does not seem to follow the rules of geometric space: Even just considering these similarity relations, the abstracted phenomenological structure of consciousness may not be sufficiently represented by a simple geometric model (e.g., a multi-dimensional vector space)(Gärdenfors, 2000) as similarity relations are known to violate axioms of distances. One example of this phenomenon is an asymmetrical relationship in similarity judgements (Hodgetts & Hahn, 2012; Palmer, 1999; Polk, Behensky, Gonzalez, & Smith, 2002; Pothos, Busemeyer, & Trueblood, 2013; Tversky, 1977). Such asymmetry in relationships violates the axioms of distances, suggesting that underling phenomenal structure cannot be captured by a simple geometric model. In that sense, the phenomenological structure mapped by this new approach might necessitate more flexible and abstract mathematical tools, such as topology and category theory (A. Haun & Tononi, 2019; Prentner, 2019; Tsuchiya & Saigo, 2020).

At the same time, the similarity in neural activation giving rise to similar experiences cannot simply be measured in physical space (including transformations such as the Talairach reference brain space): Two observers having the same conscious experience will not have the exact same 3D activation pattern in their brains (even monozygotic twins have anatomically distinct brains, with different gyri and sulci (Lohmann, Von Cramon, & Steinmetz, 1999)). Thus, some kind of abstraction is necessary to find the specific aspect of brain activity that is isomorphic to the structure of phenomenology. One promising idea is to mathematically extract the informational structure that is inherent in neuronal activity (Figure 5, bottom row). A particularly promising analytical approach in this regard is provided by the Integrated Information Theory (IIT) of consciousness proposed by Tononi (Tononi, 2004). IIT rests on a small set of axioms that are based on the first-person experience of consciousness. For example, any conscious experience is integrated. That is, we have a singular experience that incorporates all senses. Further, any conscious experience is informative in that it uniquely specifies what we experience among all possible experiences. The key argument of IIT is that consciousness is integrated information. That is, any integrated information is a form of consciousness. This definition excludes most information in the universe since it is not integrated to a unified whole. In order for information to turn into consciousness, it has to become integrated by a system such as our brains. Importantly, this key aspect of integration is well defined and measurable, and doing so shows that most information-processing systems do not feature this property. Most importantly, IIT is both a mathematically formalized framework and allows for quantitative assessments. Specifically, IIT defines the amount of integrated information as the amount of causal constraints of a system that is specified by all combinations of its parts - that is, how much the whole is more than the sum of parts.

Recent advances of IIT have culminated in the development of algorithms to empirically derive (accurate proxies of) informational structures from neural recordings (Barrett & Seth, 2011; A. M. Haun et al., 2017; Leung, Cohen, Van Swinderen, & Tsuchiya, 2020; Mayner et al., 2018; Oizumi, Albantakis, & Tononi, 2014; Oizumi, Amari, Yanagawa, Fujii, & Tsuchiya, 2016; Tegmark, 2016).

IIT-based analyses rest on a solid theoretical foundation in that IIT successfully explains various properties of conscious phenomenology and known neural physiology such as why we can lose consciousness due to brain lesions, general anesthesia, certain types of epilepsy, and deep sleep while our brains remain highly active. IIT suggests that in all these cases, loss of consciousness is caused by disruptions of the structure of integrated information that is otherwise carried by the brain. IIT also explains why certain brain lesions, such as in the cerebellum, basal ganglia and even in prefrontal cortex seem to have relatively minor impact on consciousness while those in posterior cortical areas are much more severe with regard to consciousness (Boly et al., 2017)(but see: (Odegaard, Knight, & Lau, 2017)). IIT suggests that this difference is due to the causal structures that are readily available in posterior cortex in the form of lateral connections between cortical columns (A. Haun & Tononi, 2019; Tononi, Boly, Massimini, & Koch, 2016).

In addition to this ad hoc explanatory power, IIT also makes various testable counterintuitive predictions about conscious phenomenology and its neuronal substrates. For example, IIT predicts that “inactivating” already “inactive” neurons in retinotopic visual areas (such as V1/V2) should completely change how we visually perceive space (A. Haun & Tononi, 2019; Song, Haun, & Tononi, 2017). This prediction is based on IIT’s notion that lateral connectivity in the retinotopic areas should support topological features of space (such as inclusion, connection, and overlap). Thus, removing the possibility of causal interactions via “inactivation” is sufficient to disrupt these causal properties of the neuronal network underlying the phenomenology of visual space. Importantly, IIT predicts that the warped perception of space following such localized intervention would come about completely independent of other neural mechanisms, such as (top-down) attention. Combined with the novel, massively sampling neurophysiological techniques and sophisticated causal tools such as optogenetics (X. Han & Boyden, 2007; F. Zhang et al., 2007), neural dust (Seo et al., 2016), non-invasive ultrasound deep brain stimulation (UDBS) (Folloni et al., 2019), ultrasound-based localized drug uncaging (microbubbles) (McDannold, Zhang, & Vykhodtseva, 2011) and designer receptors exclusively activated by designer drugs (DREADDS) (Roth, 2016), this prediction becomes increasingly empirically testable. Future success rests on this type of strong theoretical guidance on how to link the formalized structure of phenomenology with precise whole brain-scale neurophysiology.

Lastly, when we can estimate the structure of information that is set up by neuronal activity together with the corresponding phenomenal structure, we can address the question of the exact relationship between the two. In this context, an exact isomorphism between neuronally construed information and phenomenology might prove too high a bar to be tested empirically. Rather, we propose a step-by-step one-directional test of correspondence (Tsuchiya, Taguchi, & Saigo, 2016). This test distinguishes IIT’s position of assuming identity between the two abstracted structures. For example, we can ask if the structure of phenomenology (e.g., the helical chromatic structure of musical) is preserved in the structure of information derived from neural activity. In the other direction, when we manipulate the brain’s connectivity in early visual cortex (Song et al 2017 eNeuro), will the spatial structure of consciousness change as predicted while maintaining the properties of the space? These are feasible tests that approach the overarching quest for isomorphism between phenomenal and neuronal information structures. Through multiple iterations of these tests, it is feasible to incrementally approach the ultimate, underlying isomorphism, which promises to bridge the gap between mind and brain.

In the current context of the division between attention and consciousness, for example, it seems feasible to manipulate attention (Marisa Carrasco, Ling, & Read, 2004; Matthews, Schröder, Kaunitz, Van Boxtel, & Tsuchiya, 2018; Prinzmetal, Nwachuku, Bodanski, Blumenfeld, & Shimizu, 1997) to perturb phenomenology in an attempt to better characterize the phenomenological structure (e.g., does the helical structure of musical chroma morph or even collapse if attention is withdrawn?).

Concluding remarks

Since Eriksen’s seminal work on the impact of unconscious stimuli on heightening one’s state of vigilance, much has happened in the science of consciousness and attention. One of Eriksen’s major contributions to experimental psychology includes his extensive studies on the flanker task (also known as Eriksen’s flanker task (Eriksen & Eriksen, 1974) as a tool to study attention. In this task, participants are asked to report the identity of a central letter (e.g., “H” or “S”) that is surrounded by task-irrelevant, congruent or incongruent letters. The degree of interference from the task-irrelevant incongruent letters is often taken as evidence of inefficient attentional filtering (Sumner, Tsai, Yu, & Nachev, 2006). Recent studies have investigated whether the attentional filtering of flankers depends on the visibility of flankers (as well as targets). These studies produced some discordant findings (Silva et al., 2018; Ho & Cheung, 2011; Wu et al., 2015; Boy, Husain, & Sumner, 2010), warranting further study.

Eriksen concluded from his own studies that visual stimuli that are presented too briefly to reach consciousness also fail to affect arousal or vigilance. And yet, Eriksen also found that multiple visual stimuli can evoke parallel, competitive or facilitative, influences on both neural and behavioral responses, suggesting that attention spreads beyond task-relevant items. In other words, Eriksen’s was among the first to indicate that neural processes outside the immediate focus of attention can influence neural responses to attended stimuli. The more recent research reviewed here goes even further by suggesting that attention can operate on visual stimuli that remain outside consciousness.

We are now at the edge of a new breakthrough regarding the neuronal dissection of consciousness and attention. Using methodological advances that were unavailable to Eriksen at the time, recent years witnessed a surging amount of convergent evidence that attention and consciousness are dissociable neuronal processes. At the same time, we are witnessing theoretical breakthroughs in our understanding of the formal, relational structure of consciousness. It is exciting to anticipate the insights that will be gained from symbiotically combining these theoretical and technological advances, and yet we realize how much work still needs to be done to truly understand how certain properties of our conscious experiences are supported by neuronal mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank Matthew Davidson for comments on an earlier version of the manuscript. AM is supported by a research grant from the US National Eye Institute (1R01EY027402-03). NT is supported by Australian Research Council (DP180104128 and DP180100396) and National Health and Medical Research Council (APP1183280).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

- Aquino TG, Minxha J, Dunne S, Ross IB, Mamelak AN, Rutishauser U, & ODoherty JP (2020). Value-Related Neuronal Responses in the Human Amygdala during Observational Learning. J Neurosci, 40(24), 4761–4772. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2897-19.2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arcizet F, & Krauzlis RJ (2018). Covert spatial selection in primate basal ganglia. PLoS Biol, 16(10), e2005930. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2005930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aru J, Bachmann T, Singer W, & Melloni L (2012). Distilling the neural correlates of consciousness. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 36(2), 737–746. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachmann T, & Hudetz AG (2014). It is time to combine the two main traditions in the research on the neural correlates of consciousness: C = L × D. Front Psychol, 5, 940. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett AB, & Seth AK (2011). Practical measures of integrated information for time-series data. PLoS Comput Biol, 7(1), e1001052. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1001052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisiach E, & Luzzatti C (1978). Unilateral neglect of representational space. Cortex, 14(1), 129–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake R, & Logothetis N (2002). Visual competition. Nat Rev Neurosci, 3(1), 13–21. doi: 10.1038/nrn701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block N (2005). Two neural correlates of consciousness. Trends Cogn Sci, 9(2), 46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2004.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block N, Carmel D, Fleming SM, Kentridge RW, Koch C, Lamme VA, Rosenthal D (2014). Consciousness science: real progress and lingering misconceptions. Trends Cogn Sci, 18(11), 556–557. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2014.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehler CN, Schoenfeld MA, Heinze HJ, & Hopf JM (2008). Rapid recurrent processing gates awareness in primary visual cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 105(25), 8742–8747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801999105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogadhi AR, Bollimunta A, Leopold DA, & Krauzlis RJ (2018). Brain regions modulated during covert visual attention in the macaque. Sci Rep, 8(1), 15237. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-33567-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollimunta A, Bogadhi AR, & Krauzlis RJ (2018). Comparing frontal eye field and superior colliculus contributions to covert spatial attention. Nat Commun, 9(1), 3553. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06042-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boly M, Massimini M, Tsuchiya N, Postle BR, Koch C, & Tononi G (2017). Are the Neural Correlates of Consciousness in the Front or in the Back of the Cerebral Cortex? Clinical and Neuroimaging Evidence. J Neurosci, 37(40), 9603–9613. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3218-16.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boly M, Seth AK, Wilke M, Ingmundson P, Baars B, Laureys S, Tsuchiya N (2013). Consciousness in humans and non-human animals: recent advances and future directions. Front Psychol, 4, 625. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosman CA, Schoffelen JM, Brunet N, Oostenveld R, Bastos AM, Womelsdorf T, Fries P (2012). Attentional stimulus selection through selective synchronization between monkey visual areas. Neuron, 75(5), 875–888. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.06.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boy F, Husain M, & Sumner P (2010). Unconscious inhibition separates two forms of cognitive control. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(24), 11134–11139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brascamp J, Sterzer P, Blake R, & Knapen T (2018). Multistable Perception and the Role of the Frontoparietal Cortex in Perceptual Inference. Annu Rev Psychol, 69, 77–103. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010417-085944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brascamp JW, van Boxtel JJ, Knapen TH, & Blake R (2010). A dissociation of attention and awareness in phase-sensitive but not phase-insensitive visual channels. J Cogn Neurosci, 22(10), 2326–2344. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2009.21397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges D, Pitiot A, MacAskill MR, & Peirce JW (2020). The timing mega-study: comparing a range of experiment generators, both lab-based and online. PeerJ, 8, e9414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RJ, & Norcia AM (1997). A method for investigating binocular rivalry in real-time with the steady-state VEP. Vision research, 37(17), 2401–2408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco M (2011). Visual attention: the past 25 years. Vision Res, 51(13), 1484–1525. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2011.04.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco M, Ling S, & Read S (2004). Attention alters appearance. Nature neuroscience, 7(3), 308–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casson AJ (2019). Wearable EEG and beyond. Biomedical engineering letters, 9(1), 53–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha O, & Blake R (2019). Evidence for neural rhythms embedded within binocular rivalry. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 116(30), 14811–14812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1905174116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chica AB, Bayle DJ, Botta F, Bartolomeo P, & Paz-Alonso PM (2016). Interactions between phasic alerting and consciousness in the fronto-striatal network. Sci Rep, 6, 31868. doi: 10.1038/srep31868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chica AB, Lasaponara S, Lupianez J, Doricchi F, & Bartolomeo P (2010). Exogenous attention can capture perceptual consciousness: ERP and behavioural evidence. Neuroimage, 51(3), 1205–1212. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MA, Botch TL, & Robertson CE (2020). The limits of color awareness during active, real-world vision. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 117(24), 13821–13827. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1922294117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MA, Cavanagh P, Chun MM, & Nakayama K (2012). The attentional requirements of consciousness. Trends Cogn Sci, 16(8), 411–417. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2012.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MA, Dennett DC, & Kanwisher N (2016). What is the bandwidth of perceptual experience? Trends in cognitive sciences, 20(5), 324–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MA, Ortego K, Kyroudis A, & Pitts M (2020). Distinguishing the Neural Correlates of Perceptual Awareness and Postperceptual Processing. J Neurosci, 40(25), 4925–4935. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0120-20.2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MA, & Rubenstein J (2020). How much color do we see in the blink of an eye? Cognition, 200, 104268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corballis MC (1995). Visual integration in the split brain. Neuropsychologia, 33(8), 937–959. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(95)00032-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crump MJ, McDonnell JV, & Gureckis TM (2013). Evaluating Amazon’s Mechanical Turk as a tool for experimental behavioral research. PloS one, 8(3), e57410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Andrea A, Chella F, Marshall TR, Pizzella V, Romani GL, Jensen O, & Marzetti L (2019). Alpha and alpha-beta phase synchronization mediate the recruitment of the visuospatial attention network through the Superior Longitudinal Fasciculus. Neuroimage, 188, 722–732. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.12.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson MJ, Alais D, vanBoxtel JJ, & Tsuchiya N (2018). Attention periodically samples competing stimuli during binocular rivalry. Elife, 7, e40868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson MJ, Graafsma IL, Tsuchiya N, & van Boxtel J (2020). A multiple-response frequency-tagging paradigm measures graded changes in consciousness during perceptual filling-in. Neurosci Conscious, 2020(1), niaa002. doi: 10.1093/nc/niaa002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson MJ, Mithen W, Hogendoorn H, van Boxtel JJA, & Tsuchiya N (2020). A neural representation of invisibility: when stimulus-specific neural activity negatively correlates with conscious experience. bioRxiv, 2020.2004.2020.051334. doi: 10.1101/2020.04.20.051334 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson MJ, Mithen W, Hogendoorn H, vanBoxtel JJA, & Tsuchiya N (2020). A neural representation of invisibility: when stimulus-specific neural activity negatively correlates with conscious experience. bioRxiv, 2020.2004.2020.051334. doi: 10.1101/2020.04.20.051334 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeGraaf TA, Hsieh P-J, & Sack AT (2012). The ‘correlates’ in neural correlates of consciousness. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 36(1), 191–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehaene S, Changeux JP, Naccache L, Sackur J, & Sergent C (2006). Conscious, preconscious, and subliminal processing: a testable taxonomy. Trends Cogn Sci, 10(5), 204–211. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2006.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWeerd P, Smith E, & Greenberg P (2006). Effects of selective attention on perceptual filling-in. J Cogn Neurosci, 18(3), 335–347. doi: 10.1162/089892906775990561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donoghue J, Bastos AM, Yanar J, Kornblith S, Mahnke M, Brown EN, & Miller EK (2019). Neural signatures of loss of consciousness and its recovery by thalamic stimulation. bioRxiv, 806687. [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty K, Schmid MC, & Maier A (2018). Binocular Response Modulation in the Lateral Geniculate Nucleus. Journal of Comparative Neurology. doi: 10.1002/cne.24417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen CW (1956). An experimental analysis of subception. The American journal of psychology, 69(4), 625–634. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen CW (1960). Discrimination and learning without awareness: a methodological survey and evaluation. Psychological review, 67(5), 279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen CW, Coles MG, Morris L, & O’hara WP (1985). An electromyographic examination of response competition. Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society, 23(3), 165–168. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen BA, & Eriksen CW (1974). Effects of noise letters upon the identification of a target letter in a nonsearch task. Perception & psychophysics, 16(1), 143–149. [Google Scholar]

- Faivre N, & Kouider S (2011). Multi-feature objects elicit nonconscious priming despite crowding. J Vis, 11(3). doi: 10.1167/11.3.2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fei-Fei L, Iyer A, Koch C, & Perona P (2007). What do we perceive in a glance of a real-world scene? Journal of vision, 7(1), 10–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiebelkorn IC, & Kastner S (2019). A Rhythmic Theory of Attention. Trends Cogn Sci, 23(2), 87–101. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2018.11.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiebelkorn IC, & Kastner S (2020). Functional Specialization in the Attention Network. Annu Rev Psychol, 71, 221–249. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-103429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folloni D, Verhagen L, Mars RB, Fouragnan E, Constans C, Aubry JF, Sallet J (2019). Manipulation of Subcortical and Deep Cortical Activity in the Primate Brain Using Transcranial Focused Ultrasound Stimulation. Neuron, 101(6), 1109–1116 e1105. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.01.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forschack N, Nierhaus T, Muller MM, & Villringer A (2017). Alpha-Band Brain Oscillations Shape the Processing of Perceptible as well as Imperceptible Somatosensory Stimuli during Selective Attention. J Neurosci, 37(29), 6983–6994. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2582-16.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frassle S, Sommer J, Jansen A, Naber M, & Einhauser W (2014). Binocular rivalry: frontal activity relates to introspection and action but not to perception. J Neurosci, 34(5), 1738–1747. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4403-13.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fries P, Reynolds JH, Rorie AE, & Desimone R (2001). Modulation of oscillatory neuronal synchronization by selective visual attention. Science, 291(5508), 1560–1563. doi: 10.1126/science.1055465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frith C, Perry R, & Lumer E (1999). The neural correlates of conscious experience: An experimental framework. Trends in cognitive sciences, 3(3), 105–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazzaniga MS (2014). The split-brain: rooting consciousness in biology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 111(51), 18093–18094. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1417892111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng H, Song Q, Li Y, Xu S, & Zhu Y (2007). Attentional modulation of motion-induced blindness. Chinese Science Bulletin, 52(8), 1063–1070. [Google Scholar]

- Gould IC, Rushworth MF, & Nobre AC (2011). Indexing the graded allocation of visuospatial attention using anticipatory alpha oscillations. J Neurophysiol, 105(3), 1318–1326. doi: 10.1152/jn.00653.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gärdenfors P (2000). Conceptual spaces: The geometry of thought A Bradford book. MIT Press, 3, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Halassa MM, & Kastner S (2017). Thalamic functions in distributed cognitive control. Nat Neurosci, 20(12), 1669–1679. doi: 10.1038/s41593-017-0020-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]