Abstract

Background:

The treatment of suicidal patients often suffers owing to a lack of integrated care and standardized approaches for identifying and reducing risk. The National Strategy for Suicide Prevention endorsed the Zero Suicide (ZS) model, a multi-component, system-wide approach to identify, engage and treat suicidal patients. The ZS model is a framework for suicide prevention in healthcare systems with the aspirational goal of eliminating suicide in healthcare. While the approach is widely endorsed, it has yet to be evaluated in a systematic manner. This trial evaluates two ZS implementation strategies statewide in specialty mental health clinics.

Methods/Study Design:

This trial is the first large-scale implementation of the ZS model in mental health clinics using the Assess, Intervene, and Monitor for Suicide Prevention (A-I-M) clinical model. Using a hybrid effectiveness-implementation type 1 design, we are testing the effectiveness of ZS implementation in 186 mental health clinics in 95 agencies in New York State. Agencies are randomly assigned to either: “Basic Implementation” (BI; a large group didactic learning collaboratives) or “Enhanced Implementation” (EI; participatory small group learning collaboratives; enhanced consultation for site champions). Primary outcomes include suicidal behaviors, hospitalizations and Emergency Department visits; implementation outcomes include protocol adoption, protocol fidelity and barriers/facilitators to implementation.

Discussion:

This project has the potential to have a significant public health impact by determining the effectiveness of the ZS model in mental health clinics, a setting where suicide attempts and suicides occur at a higher rate than any other healthcare setting. It will also provide guidance on the implementation level required to achieve uptake and sustainability of ZS.

Trial registration:

N/A

Keywords: suicide prevention, zero suicide, outpatient mental health, effectiveness, implementation, hybrid trial, learning collaborative

1. Introduction

Over the past two decades, the US suicide rate has increased dramatically. In 2018, over 48,000 individuals died by suicide [1]. This stands in stark contrast to many other leading causes of death, such as cancer or heart disease, which have decreased 10–15% during the same period [2, 3]. Outpatient mental health clinics are important implementation sites for suicide prevention efforts because the suicide rate in this population is quite high at 1%, approximately 100 times higher than the general population [4]. Over 25% of individuals dying by suicide and >50% of those who attempt suicide receive care in mental health clinics in the year prior to their suicidal behavior [5, 6]. Within New York State, the setting for this trial, Medicaid claims data indicate that nearly 73% (N=1886) of those with suicide attempts or who died by suicide were seen in outpatient mental health <6 months prior to their suicidal behavior and 61% (N=1571) were seen <30 days prior. Of the 201 individuals who died by suicide, 68% (N=136) were seen in outpatient care <6 months prior and 49% (N=99) <30 days prior. In comparison, only 24% (N=624) had an ED visit and 39% (N=1010) had a psychiatric hospitalization less than six months prior to their suicide event [7–8]. Clearly, current strategies to prevent suicide can be improved and, if successful, will help decrease suicide attempt and suicide death rates.

Suicidal individuals often "fall through the cracks" of healthcare systems that are not well-integrated and lack standardized specific approaches to mitigating suicide risk in their patients. To address this problem, the 2012 National Strategy for Suicide Prevention [9] endorsed the Zero Suicide (ZS) model [10], a multi-component, system-wide approach combining individual care and systems-level elements to effectively identify and treat suicidal patients. The ZS model is a strategic framework for suicide prevention in the health care system with the aspirational goal of eliminating all suicide deaths of individuals who are engaged in care. The model offers guidance and resources for administrators and providers to create a systematic approach to quality improvement for suicide prevention. The ZS approach presents the “basics” of good care to prevent suicide within the healthcare system. It identifies seven essential elements of an effective, coordinated system for suicide care. Four of these elements (Identify, Engage, Treat, and Transition) focus on clinical care of the patient, and the remaining three (Lead, Train, Improve) relate to implementation and culture change. According to the ZS approach, three reasons are cited why patients die by suicide despite receiving care: 1) detection of suicide risk in healthcare settings is inadequate; 2) evidenced-based suicide-specific interventions are not being sufficiently deployed; and 3) intensity of care is not increased during high-risk periods.

While strides have been made in the development of "best practices" for suicide screening [11], risk assessment [12], suicide-specific clinical interventions [13–16], and follow-up protocols for suicidal individuals [17,18], there is a significant gap between development of these clinical tools and their widespread implementation in healthcare settings [19]. Further, the field of suicide prevention has only recently begun to incorporate the principles of implementation science when disseminating evidence-based practices into routine clinical practice [20]. Even less attention has been paid to understanding the maintenance of improvements [21]. Despite these obstacles, the few health care systems that have incorporated ZS recommended, evidence-based suicide prevention practices have reported subsequent reductions in suicide deaths [22–25]. While results are promising, these studies have not been randomized trials and the organizations in which the approach was implemented were unified systems of care with a single electronic health records (EHR) and centralized control, in contrast to most mental health clinic settings that are free-standing entities with their own EHRs and decision-making authority [26]. To date, no studies have explored ZS implementation efforts in a large diverse group of mental health clinic provider agencies. Given that the ZS approach is being promoted nationally, it is important to determine factors that maximize its effectiveness and the intensity of implementation required to achieve uptake and sustainability. Earlier work force survey data from NYS indicated that prior to this project, there were low rates of suicide screening, risk assessment and safety planning and high rates of suicidal behavior in psychiatric outpatients [27–29].

2. Aims and Research Questions

This is a large-scale implementation and evaluation of two implementation strategies of the ZS approach in outpatient behavioral health using the Assess, Intervene, and Monitor for Suicide Prevention (A-I-M) clinical model incorporates the four clinical elements of ZS (Identify, Engage, Treat, and Transition), developed by Stanley et al. [30–32] (Figure 1). Using a hybrid effectiveness-implementation type 1 design [33], we are testing the effectiveness of two ZS implementation strategies in 186 mental health clinics in 95 agencies in New York State in collaboration with the NYS Office of Mental Health (NYSOMH) Bureau of Evidence-Based Services and Implementation Science, which routinely conducts quality improvement projects within NYS Office of Mental Health [34] and offers incentives for participation with an increase in the Medicaid claims rate of 3.8%.

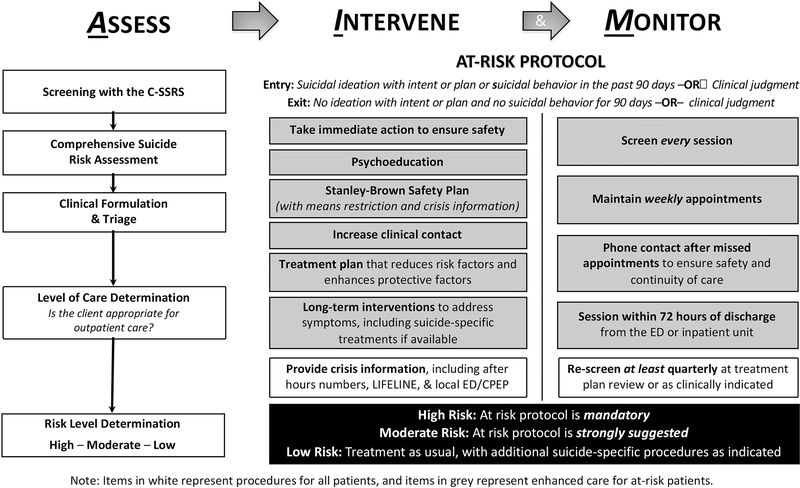

Figure 1.

Clinical procedures for the Assess, Intervene, and Monitor for Suicide Prevention (AI-M) model.

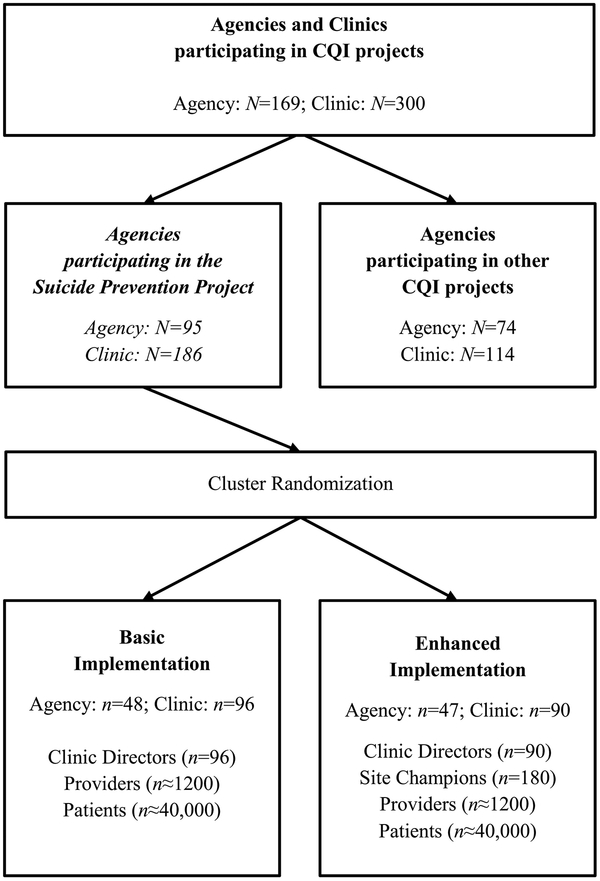

Agencies are randomly assigned to one of two conditions with different levels of implementation support: “Basic Implementation” (BI; a large group learning collaborative with limited interactivity) or “Enhanced Implementation” (EI; small group interactive learning collaboratives with enhanced training/consultation for clinic-identified “site champions”). (See Implementation Conditions section 3.5). In Aim 1, we compare the effectiveness of EI and BI conditions in reducing suicidal behaviors (attempts and deaths), psychiatric hospitalizations and emergency department (ED) visits. We are also conducting cohort (clinics not participating in this project) and historical comparison analyses (period prior to implementation) to determine the effectiveness of EI and BI conditions, separately and combined, versus. In Aim 2, we use a mixed qualitative-quantitative approach to compare the EI and BI conditions on implementation and maintenance of the ZS model. We employ the Precede-Proceed framework [35–36] (Figure 2) (see section 3.6 for detailed information) to evaluate agency- and provider-level predisposing, enabling, and reinforcing factors affecting implementation success, as well as rates and quality of ZS components (process/impact evaluation) during implementation, maintenance, and follow-up periods.

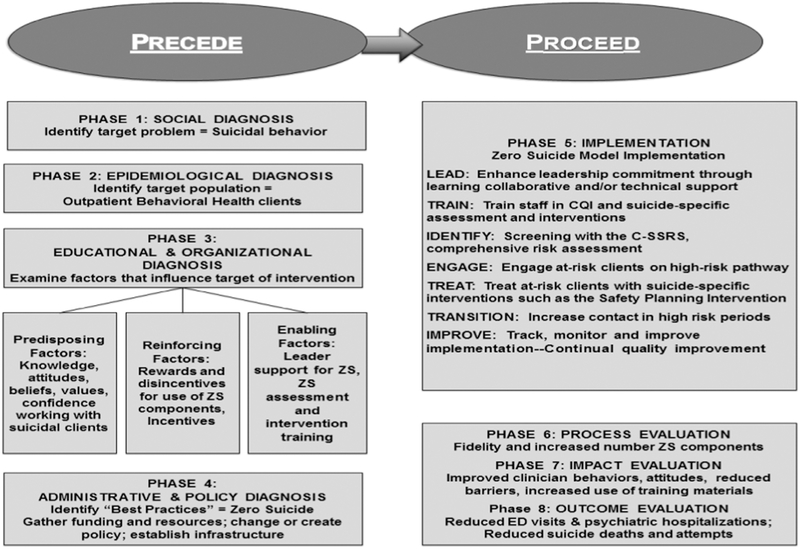

Figure 2.

The Precede-Proceed model applied to Zero Suicide implementation using the Assess, Intervene, and Monitor for Suicide Prevention (A-I-M) model.

Our aims are as follows:

Aim 1: To use a randomized hybrid effectiveness-implementation design to compare the effectiveness of BI and EI of the ZS approach using the A-I-M model in mental health clinics.

Hypotheses:

EI clinics, compared to BI clinics, will have reduced rates of: 1) suicidal behaviors (attempts and deaths); 2) psychiatric hospitalizations; and 3) ED visits for high risk clients during active Implementation, Maintenance (sustainability), and Follow-up phases.

Exploratory Aim 1A.

Using a historical comparison method, we will compare outcomes from participating clinics before and after ZS implementation on rates of: 1) suicidal behaviors (attempts and deaths); 2) psychiatric hospitalizations; and 3) ED visits (suicide-related vs non-suicide-related visits will be explored).

Exploratory Aim 1B.

Using a cohort comparison method, we will compare ZS participating clinics (clinics that are in either EI or BI) with matched non-participating clinics on rates of: 1) suicidal behaviors (attempts and deaths); 2) psychiatric hospitalizations; and 3) ED visits.

Aim 2. To compare BI and EI conditions on implementation and sustainability of the ZS approach in mental health clinics.

Hypotheses:

When compared with BI, EI clinics will have more successful implementation, as measured by: 1) greater protocol adoption (i.e., greater rates of suicide screening for all clients and safety plan creation and follow-up mental health clinic visits for high risk); 2) greater fidelity; and 3) fewer reported barriers to protocol implementation and more positive attitudes and greater confidence working with suicidal clients during implementation, maintenance (sustainability), and follow-up periods.

Exploratory Aim 2A.

Using mixed qualitative-quantitative approaches, we will examine differences between EI and BI clinics in implementation processes, such as facilitators and barriers of implementation, experiences of clinic leadership and staff, and utilization/uptake of intervention training materials.

Exploratory Aim 2B.

To explore mediators, we will examine whether more successful implementation, i.e. better adoption and fidelity and more positive implementation climate, is associated with greater effectiveness (i.e., fewer suicidal behaviors, psychiatric hospitalizations, and ED visits).

3. Methods

3.1. Participating Clinics

One hundred eighty-six mental health clinics in New York State (NYS) from 95 agencies, enrolled in this project (48.6% of 383 invited clinics). Participating clinics were very diverse in terms of census size (M=983 clients; Range=18–3300), number of providers (M=26 providers; Range=9–162), and geographic location (approximately 45% New York City and 55% rest of state, with participating clinics in 55 of 62 counties). Approximately 27% of the clientele served were youth (<18 years; Range=0–98%); 65% of clients used Medicare/Medicaid (Range=0–80%) and 35% used private insurance (Range=20–100%).

All clinicians and clients in participating clinics were included in the project (Figure 3). The participating mental health clinics report serving approximately 80,000 patients (Figure 3). Based on the New York State Office of Mental Health Patient Characteristics Survey [37] approximately 30% of clinic patients at participating agencies are youth (<18), 63% adults (18–64), and 7% are elderly (65+). Approximately 42% of patients in participating clinics are racial minorities, and 24% identify as Hispanic/Latinx. Agencies in New York City or Long Island represent 55% of the sample, with the remaining 45% of agencies from western, central, or Hudson River regions of New York.

Figure 3.

ZS study flow chart

3.2. Study Design

In this project, we employ an effectiveness-implementation Type 1 design [33] and cluster randomization with stratification to assign agencies to either BI or EI (see Implementation Conditions section 3.5) to determine the implementation level required for effectiveness and sustainability of the ZS approach using A-I-M. Agencies are randomly assigned to the BI or EI condition using a clustered randomization procedure. Randomization was conducted by the study statistician using a computer program that randomly assigns implementation type by clusters (agencies) and stratified by geographic region (upstate vs. downstate) and agency size (based on patient census higher vs. lower than 1,000). Additionally, a historical control comparison analysis will examine outcomes within agencies before and after A-I-M implementation. Third, a matched-cohort comparison analysis will compare outcomes between agencies that are in this project and those not choosing to participate

A hybrid effectiveness-implementation type 1 design was selected because it allows for the evaluation of the effectiveness of implementation conditions for both process and outcome indicators. The decision to randomize by agencies, instead of clinics, was made because it was not feasible to control diffusion of EI and BI knowledge, training, and procedures between clinics within the same agency. BI was chosen as a comparator because this is the standard approach used by the Bureau of Evidence-Based Services and Implementation Science to support large scale and statewide practice implementations [34, 38–43].

3.3. Study Phases

The study has a 6-month Preparation Phase, during which materials are prepared, sites randomized, leadership engaged, clinics complete self-assessments, and clinic point persons/site champions attend monthly learning collaborative webinars that provide the information required for A-I-M implementation, the rationale for the ZS model and A-I-M interventions, reporting requirements and procedures, the project timeline, and training resources. In addition, clinic leadership and all clinical staff complete training for the interventions, consisting of three modules, via an online management system: 1) suicide screening and comprehensive risk assessment; 2) the safety planning intervention for suicide prevention; and 3) procedures for the at-risk protocol. Training was offered via online, interactive, distance learning modules and training videos administered by the Center for Practice Innovations Learning Management System (LMS). The New York State (NYS) Office of Mental Health provides access to this LMS free-of-charge for any provider working in a NYS-licensed or state-operated facility. Trainings ranged in length from 45 minutes (Risk Assessment module, Safety Planning module) to an hour and a half (Adaptations for Youth video). Trainings were developed by the research team and are considered standard training for those interventions and are widely disseminated as a core component of the NYS Suicide Prevention strategy, As part of the preparation phase, a workforce survey was administered prior to the implementation of any project activities and annually thereafter for the duration of the project. This survey assesses both organizational readiness for change (e.g., staffing, leadership engagement, supervision, barriers and facilitators, etc.) as well as provider-level indicators of clinical preparedness (e.g., suicide prevention knowledge, training, attitudes, self-efficacy, confidence and comfort working with suicidal clients and utilization of evidence-based practices).

The 6-month preparation period is followed by three 12-month active phases: implementation; maintenance, and follow-up. During the Implementation phase, the A-I-M assessments and interventions are initially deployed for all new patients during the clinic admission process, then extended to all patients at quarterly treatment plan reviews after the first three months, with the goal of having all patients screened and assessed by six months after the start of Implementation. In this phase, clinics are to make efforts to improve implementation of the A-I-M procedures. Quality improvement (QI) information, technical support, and clinical/implementation assistance is to be provided to agencies. The 12 months after implementation is the Maintenance phase, during which clinics continue improving and sustaining performance with reduced external technical or clinical/implementation support. The Follow-up phase is the 12 months after Maintenance concludes and is used to assemble suicide data, query the National Death Index, if feasible, for suicide deaths that were not obtained in the New York State Integrated Mandated Reporting System (NIMRS) [44], and examine extended sustainability.

During the 12-month Implementation Phase, clinics implement the A-I-M model, collect data on their delivery of A-I-M model components, and review data to improve processes. Clinic QI data is aggregated by the project team and fed back to participating clinics. Ongoing monthly learning collaborative webinars address administrative, implementation and clinical issues. One-to-one consultation is available, via email or phone, and the project team reaches out to clinics to support engagement based on participation and performance tracking as needed. In the Maintenance Phase, monthly learning collaborative calls end and are replaced by individual agency quarterly consultation calls with a multi-disciplinary QI team; monthly QI data reporting and aggregation continues.

3.4. The A-I-M Intervention

This project implements and evaluates the effectiveness of the ZS model in outpatient behavioral health using the A-I-M model of suicide-safer care. The model was developed and implemented for New York State suicide prevention training of clinicians [30–32]. The A-I-M model includes two levels of intervention: 1) basic suicide prevention strategies for all outpatients irrespective of risk level and 2) assessment and intervention strategies for patients at elevated risk for suicide. A-I-M includes assessment, intervention, and monitoring of all patients in order to detect suicide risk and engages elevated risk patients in a specialized at-risk protocol. In this project, at-risk patients remain in the specialized protocol while at elevated risk and for at least 90 days after resolution of elevated risk, or at clinical discretion. This at-risk protocol, the “Suicide Care Pathway” includes: 1) routine assessment of suicide risk at each outpatient visit; 2) suicide-specific interventions including development of a safety plan using the Safety Planning Intervention (SPI) [13], psychoeducation about suicide risk and the at-risk protocol, and treatment planning that specifically targets reducing suicide risk; and 3) increased clinical contact (i.e., at least weekly sessions) and monitoring with assertive outreach to ensure safety and continuity of care after care transitions or missed appointments.

3.4.1. Assess.

The Assess component of AIM maps onto the Zero Suicide element, Identify. All patients are screened for suicide risk at intake, quarterly treatment review, or as clinically-indicated (i.e., whenever there is an abrupt change in clinical status or if the clinician is concerned) using the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) Lifetime/Recent screening version [11]. At intake, the C-SSRS queries both lifetime and recent suicidal thoughts and behaviors; subsequently, it only asks about suicidal thoughts or behaviors since the last administration of the C-SSRS. In addition, all patients receive a comprehensive suicide risk assessment (at intake or when clinically-indicated for existing patients), which provides a broader case conceptualization and creates an individualized profile of both risk and protective factors that may be chronic/distal or acute/proximal, modifiable or not modifiable. Depending on clinic policies, a comprehensive risk assessment should be completed in the same session as a positive C-SSRS screen unless the screening indicates that emergency care is required immediately. In these circumstances, comprehensive suicide risk assessment is conducted at the higher level of care.

A client is considered high-risk based on the result of a comprehensive suicide risk assessment and clinical judgment; typically, clients endorsing suicidal ideation with intent or plan or suicidal behavior in the past three months are considered high risk, though clinicians are permitted to “opt in” clients with less severe symptoms if they determined it was clinically-indicated based on their risk assessment. Moderate risk clients are those not meeting high-risk criteria but who may still benefit from some enhanced, suicide-specific interventions (e.g., suicidal ideation without intent or plan or suicidal ideation or behavior more distal than the last three months, numerous risk factors and few protective factors where the clinician feels concerned about the potential for a future crisis, etc.). Low risk clients are those with few risk factors, numerous protective factors, and no recent suicidal ideation or behavior.

If patients are deemed to be at high-risk, they are likely appropriate for the at-risk protocol. Patients are automatically placed in the at-risk protocol if they endorse suicidal ideation with plan or intent or suicidal behavior within the past 90 days (i.e., a "Yes" response to questions 4, 5, or 6 on the C-SSRS). Patients may also be placed on or removed from the protocol based on clinical judgment; if clinical judgment is used to add or remove a patient from the protocol, the rationale must be clearly documented. Patients placed in the at-risk protocol are denoted as such in the medical record.

All clients were required to be screened at intake and quarterly treatment plan review, and receive a comprehensive suicide risk assessment at intake and after any positive screen. After risk assessment, clinicians were encouraged to consult with supervisors before making risk level and level of care determinations.

3.4.2. Intervene.

The Intervene element of A-I-M maps onto the Zero Suicide components of Engage and Treat. Initial clinical contact is used to determine which actions need to be taken immediately to maintain patient safety. This includes determining whether hospitalization is required. High risk clients that needed a higher level of care are referred either to mobile crisis, psychiatric emergency programs, emergency departments, and inpatient units as necessary to maintain safety; upon returning to the clinic after discharged, they are considered high-risk and follow all Suicide-Safer Care Pathway requirements. High risk clients who are appropriate to retain in outpatient settings are required to receive all aspects of the Suicide-Safer Care Pathway for at least 90 days, including: the safety planning intervention including provision of crisis information and means reduction counseling; a treatment plan that directly targeted suicidality, reduced risk factors, and enhanced protective factors; increased clinical contact including at least weekly sessions; suicide screening at each session; prioritization for outpatient appointments within 72 hours of discharge from an acute care setting; and follow-up phone contact after missed appointments and care transitions to maintain safety and continuity of care. Moderate risk clients are strongly recommended to receive these interventions, but clinicians could use their clinical judgment as to which interventions are most appropriate to select and for what duration. If patients are deemed to be at-risk but safe to maintain as outpatients, completing the 6-step Stanley-Brown Safety Planning Intervention (including provision of crisis information and means reduction) is required. It may also involve including friends or family in the safety planning and means reduction process, if appropriate. Means reduction counseling is a critical step of safety planning. Expectations include that clinicians assess access to means across the client’s environments (e.g., home, school/work, etc.), develop a collaborative plan to reduce or remove access to available means (including both those endorsed as part of planning as well as other accessible dangerous means), and then follow-up with the client to ensure that the plan was enacted.

The clinician should also provide psychoeducation about the nature of suicide risk and brief the patient regarding the requirements of treatment on the at-risk protocol and the rationale for these interventions. In subsequent sessions, the clinician constructs a treatment plan that directly addresses reducing suicide risk. If the clinician is trained in suicide-specific interventions, such as Cognitive Therapy for Suicide Prevention (CT-SP) [14], the Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicidality (CAMS) [16], or Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) [15], these approaches may be used. Alternatively, regardless of clinician orientation or training, a treatment plan must be developed that directly aims to reduce modifiable risk factors and enhance modifiable protective factors, as informed by the risk assessment. Moderate and low risk clients are required to receive crisis information (e.g., psychoeducation about suicide risk and warning signs, hotline and local emergency contacts) and be re-screened at least quarterly.

3.4.3. Monitor.

Monitor in AIM maps onto Transition in Zero Suicide. The clinician should maintain weekly sessions with all patients in the at-risk protocol. If the intake and risk assessment are not conducted by the treating clinician, patients in the protocol should be prioritized to be assigned to a treating clinician within a week and should not be placed on a waitlist. Patients should be rescreened weekly at each session using the C-SSRS — Since Last Contact screening version. The clinician should also assess whether the patient has used their safety plan, problem-solve any barriers to its use, and revise the safety plan based on the patienťs feedback.

If the patient misses a scheduled appointment, the clinician should make outreach contact to ensure safety and maintain continuity of care. This contact will likely consist of a phone call, but could take the form of text messaging, emails or home visits based on clinic policies. When making outreach contact, the purpose is to show the clinician’s concern over the patienťs absence, assess their mood state and current suicide risk, orient them to the safety plan and crisis resources, problem-solve barriers to using the safety plan and attending treatment, and re-engage them in treatment by re-scheduling an appointment as soon as possible. If a patient in the at-risk protocol has a behavioral health emergency department visit or inpatient hospitalization, they should be prioritized to receive a mental health clinic appointment within 72 hours of discharge from acute care settings. Clinicians should also strive for contact with other treatment providers, if possible, to ensure "warm handoffs" and continuity of care during acute care transitions.

All patients in the protocol will receive these enhanced interventions and monitoring procedures for a minimum of 90 days. A patient is eligible to exit the protocol after 90 days without a positive screen (i.e., no endorsement of suicidal ideation with intent or plan or suicidal behavior on questions 4, 5, or 6 of the C-SSRS) or behavioral health ED visit or inpatient hospitalization. A patient can be removed from the protocol prior to 90 days or maintained in the protocol longer based on clinical judgment; if clinical judgment is used, the rationale must be clearly documented.

Only patients evaluated as high risk are required to receive at-risk protocol procedures; however, it is recommended that patients at moderate risk receive clinically-indicated at-risk protocol interventions, and even patients at low risk receiving "treatment as usual" may benefit from certain additional suicide-specific interventions based on the clinician's judgment. However, given the intensity of the “full package” of at-risk protocol interventions, effort should be targeted toward those at highest risk in order to maintain vigilance and prioritize resources. The clinician should utilize their clinical judgment when treatment planning and incorporate those interventions as appropriate with their patients not in the at-risk protocol.

Patients not in the at-risk protocol are re-screened at least quarterly at treatment plan review. A positive screen should trigger comprehensive suicide risk assessment and determination of whether the patient requires a higher level of care and is appropriate for inclusion in the protocol. All patients should be provided with 24-hour crisis information during their intake and again at each quarterly treatment review, including the clinic's off-hour/crisis numbers if this service is available, crisis support services such as mobile crisis, local emergency departments, and the national suicide prevention hotline.

3.5. Implementation Conditions

The Basic Implementation (BI) condition procedures follow usual procedures for Bureau of Evidence-Based Services and Implementation Science quality improvement projects and include the following steps: prior to project launch an expert panel is convened to plan the collaborative content; and participating sites are required to commit to project participation and identify a point person/site champion responsible for project requirements [38–39, 42]. Responsibilities of the point person include attending monthly learning collaborative calls, overseeing staff training and all aspects of implementation and data collection.

The Enhanced Implementation (EI) procedures include all activities in the BI condition. Additional enhancements provided to EI clinics include: 1) consultation on selection and implementation of clinical point persons or “site champions”; 2) implementation of monthly small-group learning collaborative webinars to facilitate implementation for clinic site champions and quality improvement; and 3) advanced training on the C-SSRS, risk assessment, SPI, and at-risk protocol procedures for site champions during small-group learning collaborative webinars. EI clinics are provided consultation to identify their site champions who, in turn, have the critical role of providing consultation, information about ZS clinical intervention resources, and support to their clinic providers. These site champions become part of a small-group Learning Collaborative allowing for dialogue between clinics, go-around for individual clinic progress review, group problem-solving for implementation challenges, and action plans that are followed-up on in the next month’s call. Additional advanced training on the C-SSRS, risk assessment, safety planning, and at-risk protocol is also provided for site champions during small-group learning collaborative calls.

3.6. The Implementation Framework: Precede-Proceed

Implementation is guided by the Precede-Proceed (P-P) implementation model [35,36]. When implementing new procedures into a system of care, a guiding implementation model enhances consistency, integration into practice, and intervention adherence. We selected the P-P implementation model [35,36] as most appropriate because of its focus on prevention. The P-P model delineates three categories of factors that influence behavior: 1) predisposing (e.g., organizational climate, knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs of management/staff); 2) enabling (organizational context, requisite skills, and environmental resources/support); and 3) reinforcing (feedback, reminders, and rewards). The presence of a supportive culture and enabling environmental resources (e.g., commitment to increased screening, safety planning, and increased contact; availability of tools; and clinician training) influence implementation of a structural intervention and, in turn, influence clinic- and clinician-level factors. In this framework, our target problem (suicide attempts and deaths) and population (mental health clinic patients) are clearly identified as an initial step, along with the rationale for focusing on suicide prevention in mental health clinics and factors contributing to high rates of suicidal behavior (i.e., lack of specialized clinician training, systematic protocols, and universal system for documentation/systematic sharing of information) [35,36] (Figure 2).

Two mechanisms of action examined across implementation and maintenance phases are: 1) organizational characteristics and 2) enabling infrastructure. Organizational characteristics are defined as qualities that affect the ability of an organization to successfully change processes or staff behaviors, such as incorporation of screening and safety planning. We are focusing on personnel factors, including clinician knowledge, attitudes, and confidence in working with suicidal patients, and leadership support for A-I-M implementation. Enabling infrastructure is defined as technical, organizational, or process support for a given clinician behavior. Examples include integrating the C-SSRS and safety planning templates into the EHR and incentivizing these behaviors. These factors were chosen because they are intrinsic to many implementation science models [45,46]. The BI condition is designed to target all factors, with the EI condition providing additional training, support, and consultation to ease implementation, address barriers, and increase sustainability.

3.7. Data Sources

Four sources of quantitative and qualitative data are used in the project:

Medicaid claims data. Patient demographic, diagnostic, suicidal behavior outcomes, inpatient, emergency, and outpatient mental health services are to be extracted from the New York State OMH Medicaid data warehouse. This data warehouse includes all paid Medicaid claims and encounters for individuals in the behavioral health population and is refreshed weekly [46].

NIMRS [44]. This electronic reporting system includes mandated reports of suicide attempts and suicide deaths by OMH licensed providers.

Clinic-level reporting data. Clinic level reporting data are used to assess clinic level of participation and implementation, including clinic attendance at learning collaborative calls, content of learning collaborative calls, clinic monthly reporting on implementation of project interventions, clinic feedback surveys, clinician workforce surveys, and technical support delivered (individual emails, phone calls).

Psychiatric Services and Clinical Knowledge Enhancement System (PSYCKES). The Bureau of Evidence-Based Services and Implementation Science developed an application, the Psychiatric Services and Clinical Knowledge Enhancement System (PSYCKES), for use by clinicians, administrators and patients throughout NYS. PSYCKES is a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)-compliant, web-based portfolio of tools designed to support quality improvement and clinical decision-making in the State Medicaid population. PSYCKES includes a Suicide Care Pathway Registry, which participating clinics used to store clinical data for at-risk patients (e.g., C-SSRS and safety plans). Additional patient level data extracted from this PSYCKES Registry includes dates and duration of patients on the suicide care pathway [34].

3.7. Measures

Three types of measures are used: measures for characterization of the sample; effectiveness measures; and implementation measures.

3.7.1. Characterization of the sample.

Demographic (i.e. age, gender, race/ethnicity), diagnostic information (i.e. all primary psychiatric diagnoses and suicide-related T and X codes) are to be obtained from administrative databases and from clinician and clinic director surveys.

3.7.2. Outcome measures.

Outcomes measures include suicide deaths, suicide attempts/intentional self-harm episodes, psychiatric hospitalizations and ED visits for suicide-related reasons. These measures are obtained from administrative databases.

3.7.3. Implementation measures.

We are obtaining information on the number of completed C-SSRS measures, risk assessments and safety plans for high risk clients. Safety plans are to be coded and scored for completion and quality of the plan by trained study staff. In addition, implementation measures relating to each component of the Precede-Proceed model will be obtained. Specifically, a clinician work force survey is administered at baseline and end of Implementation, Maintenance and Follow-up phases. This survey provides information on several predisposing and enabling factors from the Precede-Proceed model, i.e. suicide-specific knowledge, attitudes, comfort, beliefs about suicide, and training experiences. In order to assess the predisposing factor of general organizational climate, we are using subscales from the Organizational Readiness for Change measure [48] including the stress subscale; the organizational climate subscale; and the motivation for change subscale, adapted for this project to reflect motivation to adopt the ZS model. We are assessing provider intent to implement ZS protocol components by obtaining provider ratings of their likelihood of implementing each ZS component at baseline and after implementation. Qualitative surveys with open-ended, free response questions to assess barriers and facilitators to implementation of the ZS model are also administered. We are administering an organizational characteristics survey to obtain descriptive information from participating clinics. The survey includes queries on services offered, staffing levels, number of patients served, staff/patient ratio and staff turnover. To conduct process evaluation, we maintain detailed records of all technical support provided to clinics. We are recording the content of learning collaborative calls including: 1) implementation action plans if developed; 2) aspects of the implementation plan that were and were not implemented; 3) challenges to implementation, including provider-, clinic-, and client-related factors; 4) factors that facilitated implementation; 5) perceived response of clients; 6) additional resources/skills requested or required; 7) perceived satisfaction with technical support, which will serve as an indicator of its reinforcing value; and 8) recommendations for other Directors/Providers. We also record dates and duration of contacts and follow-up required and executed. During the Follow-up phase, we will conduct qualitative analysis of these data to elaborate dominant themes pertinent to each area assessed.

3.8. Statistical Analysis

3.8.1. Quantitative analyses.

In Aim 1, we propose to test the hypotheses that EI (compared to BI) agencies will have: 1) reduced rates of suicidal behavior 2) reduced rates of inpatient psychiatric hospitalizations; and 3) reduced rates of ED visits during the implementation, maintenance and follow-up phases for high-risk patients. Patients will be included in the sample regardless of treatment adherence or drop-out, thereby making these intent-to-treat analyses. For each phase, we will use separate mixed-effect logistic regression analyses with implementation condition as the fixed effect and agency-specific random intercept. In secondary analyses, the model will be adjusted for relevant patient and clinic-level covariates. Implementation condition by covariate interactions will be explored to determine moderators. In Exploratory Aim 1A, using a historical comparison method, we will compare outcomes from participating clinics in the one year before ZS preparation and during ZS implementation on rates of: 1) suicidal behaviors; 2) psychiatric hospitalizations; and 3) ED visits. Mixed-effect logistic regression will be performed to determine if there is a significant interaction testing whether the suicidal behavior rate decreased more in the EI group.

In Exploratory Aim 1B, using a cohort comparison method, we will compare ZS agencies with matched non-ZS agencies on rates of: 1) suicidal behaviors (attempts and deaths); 2) psychiatric hospitalizations; and 3) ED visits during the implementation, maintenance and follow-up phases. Participating agencies will be matched with non-participating agencies on the basis of region, agency size, and demographic indicators of the area served, using the function “optmatch” [49] from the statistical language R [50]. Outcomes will be tested in separate mixed effect logistic regression models with a three-level group variable (Control, BI, EI) as predictor.

In Aim 2, we compare BI to EI on implementation and sustainability of the ZS model. We hypothesize that EI will have: 1) greater adoption, specifically greater rates of suicide screening for all patients and greater rates of safety plan creation and follow-up mental health clinic visits for high risk patients; 2) greater fidelity as indicated by better quality of safety plans; and 3) more positive attitudes and greater confidence in working with suicidal patients, and fewer reported barriers during implementation, maintenance and follow-up periods. The two implementation conditions will be compared using mixed effects logistic regression and mixed effect regression analysis. In our exploratory Aim 2A, using mixed qualitative-quantitative approaches, we will examine differences between EI and BI clinics in implementation processes, such as facilitators and barriers of implementation, experiences of clinic leadership and staff, and utilization/uptake of intervention training materials. Using agency- and provider-level data, quantitative measures describing implementation processes between the two implementation conditions will be compared using t-tests and non-parametric Wilcoxon tests on the agency level and mixed effect regression on the provider level. In addition, in repeated measures mixed effect models, the effect of agency and provider-level factors on the outcomes in Hypothesis 2.1 will be tested. Analyses will be repeated with lagged versions of the predictors. In exploratory Aim 2B, we will examine whether more successful implementation (as determined by Aim 2 measures) is associated with greater effectiveness (as determined by Aim 1 measures). The agency-level implementation measures assessed in Aim 2 will be added as fixed effects to the patient-level mixed effect logistic regression models described in Aim 1 with suicidal behavior, ED visits, and psychiatric hospitalization as outcomes. The analysis will be repeated on the agency level with lagged predictors.

3.8.2. Qualitative data analysis.

Analysis of qualitative information is guided by the “grounded theory” approach described by Strauss and Corbin [43, 44]. First, narratives from the learning collaboratives will be reviewed to identify analytic thematic categories that emerge in response to the topics covered during consultation based on the key elements of the ZS model [10]. and open-coding will allow for the emergence of new theoretical constructs. Qualitative material will be tracked and coded for major categories and sub-categories independently by research team members using Nvivo version 13 [https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivoqualitative-data-analysis-software/home].

Second, initial codes will be revised and refined through re-reading of textual data and discussion by the research team, and a codebook will be created. Following revision of codes, we will apply the new coding system to allow for an iterative analytic process. Data that do not fit the categories will be reviewed systematically over the course of the study for the purpose of adding other codes. The research team will explore how constructs are related and differ in frequency or meaning, summarizing the data in matrices to compare patterns of responses across participants. A final coding scheme will be achieved through consensus of the research team. To check the reliability of codes, inter-rater reliability will be calculated using kappa-coefficients. The validity of our qualitative material will be derived from analytic induction by searching for deviant cases and using the constant comparative method.

Qualitative data, collected directly from providers and clinic leadership and coded from transcripts of learning collaborative calls, will be used in concert with quantitative data for a number of purposes, including: hypothesis generation regarding barriers and facilitators of implementation and training uptake; providing richness and depth to the discussion of barriers and facilitators throughout the project, thereby complementing quantitative data; and affording an opportunity for course corrections throughout the project to improve implementation uptake, ZS fidelity, and sustainability.

3.9. Power Analysis

This study was powered for Aim 1 Hypothesis 1, suicidal behavior; adjustments for multiple testing were not included due to the low rate of suicidal behavior. Patients nested within the same agencies are correlated rather than independent; thus the classical sample size calculations need to be adjusted [53,54] by the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) or Design Effect. The following estimates were used: high-risk population was estimated as 25% of the full yearly census [55], and baseline rate of suicide attempts and deaths in the high-risk sample was estimated as 5% [34]; the % of participating agencies was estimated between 50–60% [56], the average number of patients per agency as 1111 [57], out of which m=278 high-risk, and for the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) based on the literature [58] as well as our preliminary analysis of data from previous years, we used three scenarios: ρ = 0 (equivalent to the individual randomization design), 0.01 and 0.05. Two effect sizes were considered for the EI vs. BI suicide rate reduction: 35% and 40%. We conclude that we have sufficient power (>80%) for all but one of the 12 scenarios considered.

4. Discussion

This is the first large-scale statewide implementation trial evaluating the ZS model in outpatient behavioral healthcare. The results of this project can have a significant, sustained public health impact by providing evidence of the effectiveness of the ZS model with suicidal patients in outpatient behavioral health, a setting where suicide attempts and deaths occur at a higher rate than any other healthcare setting [4, 59–60]. Furthermore, it will provide guidance on the level of implementation required to achieve maximal uptake and sustainability in outpatient behavioral health settings. It will employ rigorous models of evaluating CQI efforts and study mechanisms of action rooted in implementation science. Given that a significant percentage of individuals who die by suicide are seen in outpatient behavioral health clinics either at the time of their death or in the prior year [6, 61–63], improving care in outpatient settings offers the very real possibility to decrease the suicide rate in the United States.

This study has several innovations. First, the large-scale scope of this study enables for analysis of low base-rate behavior, i.e. suicidal behavior. This project represents the largest mental health clinic implementation of the ZS model, in NYS clinics serving upward of 80,000 patients. This enormous sample will provide meaningful effectiveness data on low base-rate suicidal behavior outcomes, as well as obtain a substantial dataset to evaluate the training and implementation process. Secondly, this project will use widespread implementation across mental health clinics that are not part of an integrated system. Most data regarding the effectiveness of ZS “pathway to care” interventions are from integrated healthcare delivery systems [22–25]. The proposed study extends beyond a single healthcare delivery system by implementing the ZS model in diverse, unrelated clinics, enhancing generalizability. Third, the project uses a hybrid effectiveness-implementation approach not previously utilized in the field of suicide prevention. This approach allows for the evaluation of the effectiveness of empirically-supported best practices for suicide prevention, as well as the extent to which training intensity and implementation support affect implementation success. Currently, the handful of stand-alone behavioral health programs who have incorporated suicide prevention best practices report mostly on effectiveness [22–25] and provide little data regarding implementation. This innovative study design enhances the ability to control for quality of implementation while evaluating effectiveness, as well as explore relationships between training, implementation, and intervention effectiveness for future dissemination. Lastly, this study uses two innovative linked administrative databases, PSYCKES and NIMRS, which will allow for the inclusion of patient-level treatment data and mandated reporting (independent of claims reporting) for all suicide deaths and attempts. This study will be the largest implementation and evaluation of the ZS implementation strategies in outpatient mental health clinics ever conducted and will provide crucial insight regarding broader dissemination. Results will inform how to best adopt empirically-supported, suicide-safe care, thereby reducing tragic and preventable loss of life. This project will help to address the need to innovate suicide prevention efforts in health care systems [64].

Acknowledgements

Funding: NIMH R01 MH112139 (PI: B Stanley), New York State Office of Mental Health contract, Supporting Science — PSYCKES (PI: M Finnerty)

Footnotes

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Drs. Brown and Stanley receive royalties for the commercial use of the C-SSRS from the Research Foundation for Mental Hygiene, Inc.

Trial status This study is not registered with ClinicalTrials.gov as NIH and institutional IRBs ruled that the project was not human subjects research.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDCP). 2017. Fatal Injury Data. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/fatal.html..

- 2.CDCP, National Program of Cancer Registries (NCPR). CDC WONDER – United States Cancer Statistics http://wonder.cdc.gov/cancer.html..

- 3.CDCP, Division for Heart Disease and Stroke (DHDSP). Data and Statistics http://www.cdc.gov/dhdsp/data_statistics/index.htm..

- 4.Brown GK, Beck AT, Steer RA, Grisham JR. Risk factors for suicide in psychiatric outpatients: A 20-year prospective study. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000; 68: 371–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stanley IH, Hom MA, Joiner TE. Mental health service use among adults with suicide ideation, plans, or attempts: results from a national survey. Psychiatr Serv. 2015; 66: 1296–1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luoma JB, Martin CE, Pearson JL. Contact with mental health and primary care providers before suicide: A review of the evidence. Am J Psychiatry. 2002; 159: 909–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.New York State Office of Mental Health (NYS-OMH) Suicide Prevention Office. 1,700 Too Many: New York State’s Suicide Prevention Plan 2016–17 https://www.omh.ny.gov/omhweb/resources/publications/suicde-prevention-plan.pdf Accessed March 20, 2020.

- 8.New York State Department of Health. Vital Statistics of New York State https://www.health.ny.gov/statistics/vital_statistics..

- 9.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General, and the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention (NAASP). National Strategy for Suicide Prevention Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services; 2012. https://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports/national-strategy-suicide-prevention/full-report.pdf.. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zero Suicide. Suicide Prevention Resource Center website http://zerosuicide.sprc.org..

- 11.Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, et al. The Columbia—Suicide Severity Rating Scale: Initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry 2011; 168: 1266–1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fowler JC. Suicide risk assessment in clinical practice: Pragmatic guidelines for imperfect assessments. Psychotherapy 2012; 49: 81–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stanley B, Brown GK. Safety planning intervention: A brief intervention to mitigate suicide risk. Cogn Behav Pract. 2012; 19: 256–264. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown GK, Ten Have T, Henriques GR, et al. Cognitive therapy for the prevention of suicide attempts: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005; 294: 563–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Linehan MM, Comtois KA, Murray AM, et al. Two-year randomized controlled trial and follow-up of dialectical behavior therapy vs therapy by experts for suicidal behaviors and borderline personality disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006; 63: 757–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jobes DA, Wong SA, Conrad AK, et al. The collaborative assessment and management of suicidality versus treatment as usual: A retrospective study with suicidal outpatients. Suicide Life-Threat Behav. 2005; 35: 483–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luxton DD, June JD, Comtois KA. Can post discharge follow-up contacts prevent suicide and suicidal behavior? Crisis. 2013; 34: 32–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Currier GW, Brown GK, Brenner LA, et al. Rationale and study protocol for a two-part intervention: Safety planning and structured follow-up among veterans at risk for suicide and discharged from the emergency department. Contemp Clin Trials. 2015; 43: 179–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.NAASP, Clinical Care and Interventions Task Force. Suicide Care in a Systems Framework http://actionallianceforsuicideprevention.org/sites/actionallianceforsuicideprevention.org/files/taskforces/ClinicalCareInterventionReport.pdf.

- 20.Brenner LA, Breshears RE, Betthauser LM, et al. Implementation of a suicide nomenclature within two VA healthcare settings. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2011; 18: 116–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chambers DA, Glasgow RE, Stange KC. The dynamic sustainability framework: Addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change. Implement Sci 2013; 8: article# 117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centerstone website. https://www.centerstone.org/about/zero-suicide..

- 23.Hampton T. Depression care effort brings dramatic drop in large HMO population’s suicide rate. JAMA. 2010; 303: 1903–1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knox KL, Pflanz S, Talcott GW, et al. The US Air Force suicide prevention program: Implications for public health policy. Am J Public Health 2010; 100: 2457–2463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Katz I Lessons learned from mental health enhancement and suicide prevention activities in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Public Health 2012; 102(S1), S14–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Croft B, Parish SL. Care integration in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act: Implications for behavioral health. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2013; 40: 258–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carruthers Jay, Director of the New York State Office of Suicide Prevention. NYS-OMH Quality Management Internal Survey. Personal communication, Unpublished data; 2016.

- 28.NYS-OM H. Zero Suicide Workforce Survey — Aggregate Results. Washington, DC: National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 29.NYS-OM H. Hudson River suicide-specific licensing requirements review. Unpublished data.

- 30.Stanley BS, Labouliere CD, Brown G, et al. Preliminary effectiveness of “Zero Suicide” implementation in a statewide outpatient behavioral health system. Symposium presented at: The Annual Conference of the American Association for Suicidology; April 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brodsky BS, Spruch-Feiner A, Stanley B. The Zero Suicide model: Applying evidence-based suicide prevention practices to clinical care. Front Psychiatry 2018; 9: article #33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Labouliere CD, Vasan P, Kramer A, et al. “Zero Suicide” — A model for reducing suicide in United States behavioral healthcare. Suicidologi. 2018; 23: 22–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, et al. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: Combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med Care. 2012; 50: 217–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.NYS-OM H. Psychiatric Services and Clinical Knowledge Enhancement System (PSYCKES) http://www.omh.ny.gov/omhweb/psyckes_medicaid..

- 35.Green LW, Kreuter MW. Health Promotion Planning: An Educational and Ecological Approach. 4th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice 4th ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 37.NYS-OMH. Patient Characteristics Survey (PCS) https://omh.ny.gov/omhweb/pcs/submissions..

- 38.Nadeem E, Olin SSS, Hill LC, et al. Understanding the components of quality improvement collaboratives: A systematic literature review. Milbank Q 2013; 91(2): 354–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nadeem E, Olin SS, Hill LC, et al. A literature review of learning collaboratives in mental health care: Used but untested. Psychiatr Serv 2014; 65(9): 1088–1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ebert L, Amaya-Jackson L, Markiewicz JM, et al. Use of the Breakthrough Series Collaborative to support broad and sustained use of evidence-based trauma treatment for children in community practice settings. Adm Policy Ment Health 2012; 39(3): 187–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kilo CM. A framework for collaborative improvement: lessons from the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s Breakthrough Series. Qual Manag Health Care. 1998; 6: 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ayers LR, Beyea SC, Godfrey MM, et al. Quality improvement learning collaboratives. Qual Manag Health Care. 2005; 14(4): 234–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.The Breakthrough Series: IHI’s collaborative model for achieving breakthrough improvement. IHI Innovation Series White Paper Cambridge, Mass: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 44.NYS-OMH. New York State Incident Management & Reporting System (NIMRS) https://www.omh.ny.gov/omhweb/dqm/bqi/nimrs.

- 45.Feldstein AC, Glasgow RE. A practical, robust implementation and sustainability model (PRISM). Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008; 34: 228–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, et al. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci 2009; 4: article #50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.NYS-OMH. NYS-OMH Medicaid Claim and Encounter Datamart. 2019.

- 48.Lehman WE, Greener JM, Simpson D Assessing organizational readiness for change. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2002; 22:197–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hansen BB, Klopfer SO. Optimal full matching and related designs via network flows. J Comput Graph Stat. 2006; 15, 609–627. [Google Scholar]

- 50.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Strauss A, Corbin J. Grounded theory methodology In Denzin NK, Lincoln YS. eds. Handbook of Qualitative Research Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publishing; 1994: 273–285. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Corbin JM, Strauss A. Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qual Sociol. 1990; 13: 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rutterford C, Copas A, Eldridge S. Methods for sample size determination in cluster randomized trials. Int J Epidemiol. 2015; 44: 1051–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Donner A, Birkett N, Buck C. Randomization by cluster. Sample size requirements and analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 1981; 114: 906–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Harkavy-Friedman JM. Suicidal behaviors in adult psychiatric outpatients, I: Description and prevalence. Am J Psychiatry. 1993; 150: 108–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.NYS-OMH. Assessment of interest in continuous quality improvement projects in the Psychiatric Services and Clinical Knowledge Enhancement System. Unpublished data; 2016.

- 57.NYS-OMH. Descriptive data on agencies participating in the PSYCKES project. Unpublished data; 2016.

- 58.Thompson DM, Fernald DH, Mold JW. Intraclass correlation coefficients typical of cluster-randomized studies: Estimates from the Robert Wood Johnson Prescription for Health projects. Ann Fam Med 2012; 10: 235–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Asnis GM, Friedman TA, Sanderson WC, et al. Suicidal behaviors in adult psychiatric outpatients, I: Description and prevalence. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(1):108–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Trivedi MH, Morris DW, Wisniewski SR, et al. Clinical and sociodemographic characteristics associated with suicidal ideation in depressed outpatients. Can J Psychiatry. 2013; 58(2): 113–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wenzel A, Berchick ER, Tenhave T, et al. Predictors of suicide relative to other deaths in patients with suicide attempts and suicide ideation: A 30-year prospective study. J Affect Disord. 2011; 132(3): 375–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ahmedani BK, Simon GE, Stewart C, et al. Health care contacts in the year before suicide death. J Gen Intern Med. 2014; 29(6): 870–877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ilgen MA, Conner KR, Roeder KM, et al. Patterns of treatment utilization before suicide among male veterans with substance use disorders. Am J Public Health. 2012; 102 Suppl 1(Suppl 1): S88–S92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stanley B, Mann JJ. The Need for Innovation in Health Care Systems to Improve Suicide Prevention. JAMA Psychiatry 2020;77(1):96–98. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.2769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]