Abstract

Abstract

One of the most debilitating symptoms of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is breathlessness, which leads to avoidance of physical activities in daily living and hastens clinical deterioration. Treatment of patients with COPD with inhaled long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA)/long-acting β2-agonist (LABA) combination therapy improves airflow limitation, reduces breathlessness compared with LAMA or LABA monotherapies, and improves health status and quality of life. A large clinical trial programme focusing on the effects of tiotropium/olodaterol combination therapy demonstrated that this LAMA/LABA combination improves lung function and reduces hyperinflation (assessed by serial inspiratory capacity measurements) compared with either tiotropium alone or placebo in patients with COPD. Tiotropium/olodaterol also increases exercise endurance capacity and improves patient perception of the intensity of breathlessness compared with placebo. In this narrative review, we focus on the relationship between improving symptoms during activity, the ability to remain active in daily life and how this may impact quality of life. We consider the benefits of therapy optimisation by means of dual bronchodilation with tiotropium/olodaterol, and present new data from meta-analyses/pooled analyses showing that tiotropium/olodaterol improves inspiratory capacity compared with placebo and tiotropium and improves exercise endurance time compared with placebo after 6 weeks of treatment. We also discuss the importance of taking a holistic approach to improving physical activity, including pulmonary rehabilitation and exercise programmes in parallel with bronchodilator therapy and psychological programmes to support behaviour change.

Graphic Abstract

Keywords: Breathlessness, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Dyspnoea, Exercise endurance, Hyperinflation, Inspiratory capacity, Meta-analysis, Physical activity, Pooled analysis, Tiotropium/olodaterol

Key Summary Points

| Breathlessness, one of the most debilitating symptoms of COPD, leads to avoidance of physical activities in daily living and hastens clinical deterioration. |

| Treatment of patients with COPD with the inhaled dual bronchodilator therapy tiotropium/olodaterol reduces breathlessness, decreases hyperinflation (marked by increases in inspiratory capacity) and increases exercise endurance capacity. |

| Overall, dual bronchodilation with tiotropium/olodaterol is associated with positive effects that may help to promote physical activity in patients with COPD. |

| A holistic approach to improving physical activity is important, including pulmonary rehabilitation and exercise programmes in parallel with bronchodilator therapy and psychological programmes to support behaviour change. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a summary slide and graphical abstract, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13160231.

Introduction

Activity-related breathlessness—one of the most common symptoms of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)—is generally noticed and reported by patients from the early stages of COPD progression [1, 2]. Activity-related breathlessness has a severe impact on all aspects of patients’ lives, preventing them from full participation in anything in life that involves physical activity [3, 4]. Patients often adopt a sedentary lifestyle to cope with symptoms, which can lead to underappreciation of the degree of limitation and dyspnoea, and thus prevents them from being further investigated and treated [5]. Reduced levels of physical activity promote deconditioning of muscles, thereby leading to increased ventilation requirement for a given level of activity, more breathlessness during physical activity and further limitation in physical activity level—the so-called “dyspnoea–inactivity vicious cycle” [6] or “downward spiral of disability” [7–10].

Population-based data demonstrate that as little as 2 h of activity per week, either walking or cycling, can have significant positive effects on the course of COPD [11]. Conversely, physical inactivity is a major—indeed, perhaps the strongest—risk factor for poor outcomes in patients with COPD [12]. As well as its association with breathlessness, physical inactivity is also linked to an increased risk of exacerbations, hospitalisations and mortality [11, 13–15]. Owing to the significant burden of breathlessness and activity limitation, and to their impact on the deterioration of patients’ health and future outcomes, improving breathlessness and activity tolerance are important goals in the treatment of COPD [16]. Indeed, reducing the breathlessness experienced by patients during activity may be key to encouraging patients to remain active and improve their quality of life [17].

Symptoms experienced by patients diagnosed with COPD vary, and include chronic progressive breathlessness, cough and sputum production, wheezing and chest tightness [18]. To alleviate these symptoms, inhaled long-acting β2-agonists (LABAs) and long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs) are regularly prescribed as maintenance treatment [16]. Five approved LAMA/LABA combinations (aclidinium/formoterol, glycopyrrolate/formoterol, umeclidinium/vilanterol, glycopyrronium/indacaterol and tiotropium/olodaterol) have demonstrated safety profiles that are consistent with their monocomponents [19].

In this non-systematic narrative review, we focus on evidence supporting the effects of tiotropium/olodaterol on activity-related breathlessness and the capacity to perform physical activity, and how this affects patients’ experience of physical activity. In addition to reviewing previously published studies, we describe new data from meta-analyses/pooled analyses evaluating the effect of tiotropium/olodaterol on inspiratory capacity (IC) and exercise endurance time. We also examine the relationship between reducing activity-related breathlessness, the ability to remain active day-to-day and how this may impact quality of life.

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Tiotropium/Olodaterol Clinical Trial Programme: Overview

A comprehensive set of studies with large study populations (over 16,000 patients combined) investigated the role of tiotropium/olodaterol on lung function and health status/quality of life. Long-term phase III clinical trials established that tiotropium/olodaterol improves airflow obstruction compared with its monocomponents, as well as improving health status/quality of life [20–22]. Improvements in St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire scores (a measure of impact on overall health, daily life and patient-perceived well-being in people with obstructive airways disease) and Mahler Transition Dyspnoea Index focal score (a measure of breathlessness in daily life) provided evidence that the observed improvements with tiotropium/olodaterol translate into patient-reported improvements in health status/quality of life and activity-related breathlessness [20, 22]. Given the importance of these findings, the effects of tiotropium/olodaterol treatment on activity-related breathlessness were studied in more detail in several trials during the tiotropium/olodaterol clinical programme.

Tiotropium/Olodaterol Improves Lung Hyperinflation

In COPD, forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) is a commonly used endpoint as a measure of treatment efficacy [23]. However, the relationship between FEV1 and daily physical activity is relatively modest, suggesting that the decrease in physical activity with COPD does not depend only on the severity of airflow limitation measured at rest, but may also depend on other factors, including dynamic hyperinflation [24]. In clinical practice and research, the degree of hyperinflation at rest and exercise may be tracked by measuring IC [25, 26]. A progressive reduction in IC during exercise is a sign of ongoing gas trapping [26]. There are many studies demonstrating that bronchodilator treatment leading to lung deflation (i.e. an increase in IC) is associated with clinically important improvements in breathlessness and in the level of patients’ exercise endurance [26, 27].

Tiotropium/olodaterol treatment has been repeatedly found to improve lung function and reduce hyperinflation compared with either of the monocomponents or with placebo in patients with COPD [21, 28–30]. In the VIVACITO incomplete-crossover study, 6 weeks’ treatment with tiotropium/olodaterol increased IC ± standard error (SE) at 2.5 h post treatment (tiotropium/olodaterol 5/5 µg: 0.351 ± 0.038 L; placebo: 0.016 ± 0.040 L; P < 0.0001 for tiotropium/olodaterol versus placebo) (Table 1) [21]. This was further supported by a significant decrease in functional residual capacity with tiotropium/olodaterol versus placebo (tiotropium/olodaterol 5/5 µg: − 0.547 L; placebo: − 0.052 L; P < 0.0001) [21]. Residual volume also decreased significantly with tiotropium/olodaterol (P < 0.0001 versus placebo) [21]. In the MORACTO study, IC prior to exercise was greater after 6 weeks of treatment with tiotropium/olodaterol 5/5 µg compared with placebo (mean ± SD 0.254 ± 0.019 L; P < 0.0001; Table 1); mean IC also increased in TORRACTO with tiotropium/olodaterol compared with placebo after 6 and 12 weeks (descriptive statistics, nominal P < 0.05 at both time points) [28, 29]. More recently, in the OTIVATO study, which was conducted in patients with evidence of hyperinflation and breathlessness during everyday activities, tiotropium/olodaterol 5/5 µg increased mean resting IC ± SE from baseline by 0.489 ± 0.049 L after 6 weeks of treatment, with a treatment difference versus tiotropium monotherapy of 0.218 L (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.121 L, 0.314 L; P < 0.0001) (Table 1) [30].

Table 1.

Summary of inspiratory capacity at rest across tiotropium/olodaterol trials

| Study | Time point | Mean baseline IC at rest, L (SE) | Treatment | Patients (n) | Adjusted mean IC at rest after treatment, L (SE) | Adjusted mean treatment difference, L (SE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T/O vs placebo | T/O vs Tio 5 µg | ||||||

| MORACTO (1) | 6 weeks | 2.533 (0.042) | Placebo | 211 | 2.440 (0.027) |

0.244 (0.027) [95% CI 0.191, 0.298] P < 0.0001 |

0.114 (0.027) [95% CI 0.061, 0.167] P < 0.0001 |

| Tio 5 μg | 213 | 2.571 (0.027) | |||||

| T/O 5/5 μg | 219 | 2.685 (0.027) | |||||

| MORACTO (2) | 6 weeks | 2.589 (0.044) | Placebo | 202 | 2.502 (0.026) |

0.265 (0.025) [95% CI 0.215, 0.315] P < 0.0001 |

0.088 (0.025) [95% CI 0.039, 0.137] P = 0.0005 |

| Tio 5 μg | 208 | 2.679 (0.025) | |||||

| T/O 5/5 μg | 218 | 2.767 (0.025) | |||||

| TORRACTO | 6 weeks | 2.397 (0.036) | Placebo | 119 | 2.402 (0.037) |

0.225 (0.051) [95% CI 0.124, 0.326] P < 0.0001 |

– |

| T/O 5/5 μg | 133 | 2.627 (0.035) | |||||

| 12 weeks | 2.397 (0.036) | Placebo | 119 | 2.390 (0.038) |

0.234 (0.052) [95% CI 0.133, 0.336] P < 0.0001 |

– | |

| T/O 5/5 μg | 133 | 2.624 (0.035) | |||||

| PHYSACTOa | 8 weeks | 2.402 (0.047) | Placebo + SMBM | 64 | 2.452 (0.051) |

T/O 5/5 μg + SMBM + ET vs placebo + SMBM: 0.318 (0.071) [95% CI 0.179, 0.457] P < 0.0001 T/O 5/5 μg + SMBM vs placebo + SMBM: 0.302 (0.070) [95% CI 0.165, 0.439] P < 0.0001 |

T/O 5/5 μg + SMBM vs Tio 5 μg + SMBM: 0.128 (0.069) [95% CI − 0.008, 0.263] P = 0.0642 |

| Tio 5 μg + SMBM | 66 | 2.627 (0.050) | |||||

| T/O 5/5 μg + SMBM | 72 | 2.755 (0.048) | |||||

| T/O 5/5 μg + SMBM + ET | 68 | 2.771 (0.049) | |||||

| 12 weeks | 2.402 (0.047) | Placebo + SMBM | 64 | 2.427 (0.051) |

T/O 5/5 μg + SMBM + ET vs placebo + SMBM: 0.387 (0.071) [95% CI 0.247, 0.526] P < 0.0001 T/O 5/5 μg + SMBM vs placebo + SMBM: 0.311 (0.070) [95% CI 0.174, 0.448] P < 0.0001 |

T/O 5/5 μg + SMBM vs Tio 5 μg + SMBM: 0.196 (0.069) [95% CI 0.060, 0.332] P = 0.0047 |

|

| Tio 5 μg + SMBM | 66 | 2.542 (0.050) | |||||

| T/O 5/5 μg + SMBM | 72 | 2.738 (0.048) | |||||

| T/O 5/5 μg + SMBM + ET | 68 | 2.814 (0.050) | |||||

| OTIVATO | 3 weeks | 2.317 (0.073) | Tio 5 μg | 97 | 2.519 (0.042) | – |

0.219 [95% CI 0.130, 0.308] P < 0.0001 |

| T/O 5/5 μg | 102 | 2.738 (0.041) | |||||

| 6 weeks | 2.312 (0.072) | Tio 5 µg | 100 | 2.590 (0.049) | – |

0.218 [95% CI 0.121, 0.314] P < 0.0001 |

|

| T/O 5/5 μg | 101 | 2.808 (0.049) | |||||

| VIVACITO | 6 weeks | 2.128 (0.049) | Placebo | 86 | 0.016 (0.040) |

0.335 (0.049) [95% CI 0.238, 0.432] P < 0.0001 |

0.100 (0.048) [95% CI 0.006, 0.194] P = 0.0372 |

| Tio 5 μg | 94 | 0.251 (0.038) | |||||

| T/O 5/5 μg | 94 | 0.351 (0.038) | |||||

ET exercise training, IC inspiratory capacity, L litre, SE standard error, SMBM self-management behaviour modification, Tio tiotropium, T/O tiotropium/olodaterol

aAll patients in PHYSACTO entered a behaviour modification programme

In order to summarise previously published data, we also performed a meta-analysis/pooled analysis evaluating the effect of tiotropium/olodaterol on inspiratory capacity at rest in MORACTO 1 and 2, TORRACTO, VIVACITO and OTIVATO (see Box 1 for details).

Effect of Treatment with Tiotropium/Olodaterol on Exercise Capacity

Exercise endurance tests are often used in clinical trials to evaluate exercise capacity. These tests generally involve walking on a level surface or cycling on a stationary bicycle. In some of the tests, exercise intensity is externally controlled either by imposing a walking speed or by the work rate on a bicycle. Patients are asked to exercise until limited by exhaustion; the outcome variables are the endurance time and symptoms that can be measured at the same exercise intensity and duration each time they undertake the test (“isotime”). Summaries of some of the more commonly used tests and the proposed minimal clinically important difference for each outcome measure can be found in Table 2. Options to evaluate patient endurance include the constant work rate cycle ergometry (CWRCE; cycling conducted at a set resistance for as long as patients can continue or until they are limited by their symptoms) and the endurance shuttle walk test (ESWT; patients walk back and forth between two cones placed 10 m apart at a predefined and constant speed until they are impeded by symptoms) (Table 2) [31, 32]. The 6-min walk test (6MWT; during which patients are asked to walk as far as they can back and forth between two cones placed 100 feet apart in 6 min) is another commonly used exercise test [33]. However, its design differs from the two preceding tests because the walking speed is self-controlled and may vary from one test to another. As such, it is not possible to measure symptoms at the same work intensity with this test. Rather, the outcome variable with the 6MWT is walking distance. In addition, as 6MWT is self-paced, it provides a measure of exercise performance rather than being a maximal test; it is therefore not as responsive to bronchodilator therapy as CWRCE and ESWT [34, 35].

Table 2.

Minimal clinically important differences for outcome measures used in COPD

| Endpoint | MCID (improvement) | Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| Breathlessness (dyspnoea) | ||

| TDI total score [59] | 1 unit | The TDI score is used to measure the severity of breathlessness related to activities of daily living |

| Health status | ||

| SGRQ total score [60] | 4 units | Measure of health-related quality of life |

| CRQ domain scores [61] | 0.5 units (average)a | Measures physical and emotional aspects of respiratory disease |

| Exercise capacity | ||

| 6-min walk distance test [33, 62] | 26 ± 2 m (patients with severe COPD) | Measures the distance that a patient can walk on a flat, hard surface in a period of 6 min |

| Incremental shuttle walking test [31, 63] | 47.5 m | The patient is required to walk around two cones a set distance apart in time to a set of auditory beeps progressively increasing in speed |

| Endurance shuttle walking test [64, 65] | 45–85 s | The patient is required to walk around two cones a set distance apart in time to a set of auditory beeps at a predetermined and constant speed |

| Constant work rate cycling endurance test [32] | 46–105 s | Measures the time patients are able to exercise at a constant work rate on a cycle ergometer, usually set between 75% and 80% of symptom-limited maximal exercise in an incremental test |

| Breathlessness (dyspnoea) during exercise tests | ||

| Modified Borg scale [39, 66, 67] | 1 unit | Patient assesses degree of breathlessness on a 0–10 scale |

CRQ Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire, MCID minimal clinically important difference, SGRQ St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire, TDI Transition Dyspnoea Index

aThe MCIDs for the individual domains differ around this mean estimate

Monitoring exercise capacity in a laboratory setting allows accurate physiological evaluation in a controlled environment. Treatment with tiotropium/olodaterol has been found to improve exercise capacity during walking and cycling tests. Two 6-week, replicate, incomplete-crossover studies, each in approximately 300 patients, found a 20.9% and 13.4% increase in geometric mean exercise endurance time during CWRCE in MORACTO 1 and MORACTO 2, respectively (both P < 0.0001) in patients with COPD treated with tiotropium/olodaterol compared with placebo (Table 3) [28]. More recently, data from TORRACTO demonstrated, in approximately 400 patients, that tiotropium/olodaterol 5/5 µg improved exercise endurance time by 13.8% versus placebo (geometric mean ± SE, tiotropium/olodaterol 5/5 µg: 527.5 ± 20.2 s; placebo: 463.6 ± 18.8 s; P = 0.02 for tiotropium/olodaterol versus placebo) during CWRCE after 12 weeks (Table 3) [29]. This study also included an ESWT outcome in a subset of patients. After 12 weeks of treatment with tiotropium/olodaterol 5/5 µg, walking endurance time increased by 20.9% compared with placebo (geometric mean ± SE, tiotropium/olodaterol 5/5 µg: 376.4 ± 25.0 s; placebo: 311.4 ± 22.5 s; descriptive statistics, nominal P = 0.055 for tiotropium/olodaterol versus placebo) (Table 3) [29].

Table 3.

Summary of endurance time during CWRCE and the ESWT across tiotropium/olodaterol activity trials

| Study | Time point | Common baseline geometric mean endurance time, s (SE) | Treatment | Patients, n | Adjusted geometric mean endurance time after treatment, s (SE)a | Adjusted geometric mean treatment ratio (SE)a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T/O vs placebo | T/O vs Tio 5 µg | ||||||

| Constant work rate cycle ergometry (CWRCE) | |||||||

| MORACTO (1) | 6 weeks | 459.95 (13.94) | Placebo | 209 | 375.45 (12.04) |

1.209 (0.041) [95% CI 1.132, 1.292] P < 0.0001 |

0.993 (0.033) [95% CI 0.930, 1.061] P = 0.8415 |

| Tio 5 μg | 209 | 457.16 (14.65) | |||||

| T/O 5/5 μg | 212 | 454.08 (14.47) | |||||

| MORACTO (2) | 6 weeks | 434.31 (14.16) | Placebo | 205 | 410.77 (12.01) |

1.134 (0.036) [95% CI 1.065, 1.206] P < 0.0001 |

1.043 (0.033) [95% CI 0.981, 1.109] P = 0.1807 |

| Tio 5 μg | 209 | 446.50 (12.96) | |||||

| T/O 5/5 μg | 216 | 465.68 (13.36) | |||||

| TORRACTO | 12 weeks | 443.0 (12.38) | Placebo | 121 | 463.63 (18.81) |

1.138 (0.063) [95% CI 1.020, 1.269] P = 0.0209 |

– |

| T/O 5/5 μg | 135 | 527.51 (20.15) | |||||

| Endurance shuttle walk test (ESWT) | |||||||

| TORRACTO | 12 weeks | 311.2 (13.68) | Placebo | 50 | 311.41 (22.52) |

1.209 (0.119) [95% CI 0.996, 1.467] P = 0.0552 |

– |

| T/O 5/5 μg | 59 | 376.39 (25.03) | |||||

| PHYSACTO | 8 weeks | 242.73 (9.42) | Placebo + SMBM | 65 | 244.07 (17.67) |

T/O 5/5 μg + SMBM + ET vs placebo + SMBM: 1.458 (0.147) [95% CI 1.196, 1.777] P = 0.0002 T/O 5/5 μg + SMBM vs placebo + SMBM: 1.292 (0.129) [95% CI 1.061, 1.573] P = 0.0109 |

T/O 5/5 μg + SMBM vs Tio 5 μg + SMBM: 1.241 (0.123) [95% CI 1.021, 1.507] P = 0.0303 |

| Tio 5 µg + SMBM | 67 | 254.18 (18.10) | |||||

| T/O 5/5 μg + SMBM | 72 | 315.32 (21.67) | |||||

| T/O 5/5 μg + SMBM + ET | 70 | 355.73 (24.79) | |||||

| 12 weeks | 241.96 (9.36) | Placebo + SMBM | 62 | 243.30 (18.68) |

T/O 5/5 μg + SMBM + ET vs placebo + SMBM: 1.333 (0.142) [95% CI 1.080, 1.645] P = 0.0077 T/O 5/5 μg + SMBM vs placebo + SMBM: 1.244 (0.131) [95% CI 1.011, 1.530] P = 0.0390 |

T/O 5/5 μg + SMBM vs Tio 5 μg + SMBM: 1.184 (0.123) [95% CI 0.964, 1.453] P = 0.1066 |

|

| Tio 5 μg + SMBM | 64 | 255.67 (19.29) | |||||

| T/O 5/5 μg + SMBM | 71 | 302.61 (21.69) | |||||

| T/O 5/5 μg + SMBM + ET | 66 | 324.21 (24.10) | |||||

SMBM self-management behaviour modification, CWRCE constant work rate cycle ergometry, ESWT endurance shuttle walk test, ET exercise training, s seconds, SE standard error, Tio tiotropium, T/O tiotropium/olodaterol

aData are based on log10 transformation. Mean and 95% confidence intervals were transformed from log10 back to the original scale

Additional insight comes from our meta-analysis/pooled analysis that we performed to evaluate the effect of tiotropium/olodaterol on endurance time during CWRCE in MORACTO 1 and 2 and TORRACTO (see Box 1 for details).

Box 1. Meta-analyses/pooled analyses of tiotropium/olodaterol on hyperinflation and exercise endurance.

To summarise the data from previous studies, we performed new analyses to investigate the effects of tiotropium/olodaterol on hyperinflation (measured by IC) and exercise endurance time in a large population of patients with COPD from MORACTO 1 and 2, TORRACTO, VIVACITO and OTIVATO. Inclusion criteria for patients included a diagnosis of COPD, age ≥ 40 years, a smoking history > 10 pack-years, and FEV1 < 80% predicted in all trials and ≥ 30% predicted in four of the five trials. We examined the effects of once-daily tiotropium/olodaterol 5/5 μg versus tiotropium 5 μg or placebo treatment on IC at rest and endurance time during CWRCE in patients with COPD at 6 weeks. Since the trials had different designs (parallel-group versus crossover), meta-analyses were performed on IC data and endurance time data from the three placebo-controlled studies that were available (MORACTO 1 and 2 and TORRACTO). A fixed-effect meta-analysis using the inverse-variance method [36] was adopted in this analysis. For studies where the study designs were sufficiently similar in terms of endpoint, treatment and duration to warrant pooling of data, pooled analyses were performed on IC data from MORACTO 1 and 2, VIVACITO and OTIVATO and endurance time data from MORACTO 1 and 2 versus tiotropium.

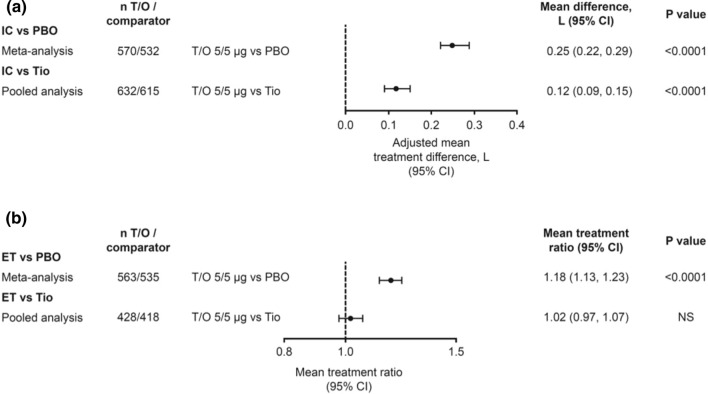

In the meta-analysis of three placebo-controlled trials (MORACTO 1 and 2, and TORRACTO), tiotropium/olodaterol (n = 570) improved IC by 0.25 L (95% CI 0.22, 0.29; P < 0.0001) versus placebo (n = 532) at 6 weeks (Fig. 1a). In the pooled analysis of the four trials that included a comparison with tiotropium (MORACTO 1 and 2, OTIVATO and VIVACITO), tiotropium/olodaterol (n = 632) improved IC by 0.12 L (95% CI 0.09, 0.15; P < 0.0001) compared with tiotropium alone (n = 615) (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

Effects of tiotropium/olodaterol 5/5 µg versus placebo and tiotropium 5 µg after 6 weeks’ treatment on a inspiratory capacity at rest (meta-analysis: MORACTO 1 and 2 and TORRACTO; pooled analysis: MORACTO 1 and 2, VIVACITO and OTIVATO) and b endurance time during CWRCE (meta-analysis: MORACTO 1 and 2 and TORRACTO; pooled analysis: MORACTO 1 and 2). CI confidence interval, CWRCE constant work rate cycle ergometry, ET endurance time, IC inspiratory capacity, L litre, NS not significant, PBO placebo, Tio tiotropium, T/O tiotropium/olodaterol

For endurance time, there were significant improvements during CWRCE with tiotropium/olodaterol (n = 563) compared with placebo (n = 535). Tiotropium/olodaterol increased endurance time by 18% compared with placebo (P < 0.0001) in the meta-analysis of MORACTO 1 and 2 and TORRACTO, but not compared with tiotropium in the pooled analysis of MORACTO 1 and 2 (Fig. 1b).

The results of these meta- and pooled analyses support an overall benefit with combination tiotropium/olodaterol treatment versus placebo or tiotropium alone in terms of IC, and versus placebo for endurance time.

Decrease in Breathlessness During Exercise Tests in Patients Treated with Tiotropium/Olodaterol

Improving breathlessness and physical activity are important goals in the treatment of COPD, and considered a valuable component of COPD assessment, particularly in response to treatment [16]. Exercise studies have demonstrated that bronchodilator treatment improves activity-related breathlessness in patients with COPD [28, 29, 37]. The 1-year, replicate, parallel-group, multicentre TONADO trials demonstrated that dual bronchodilation with tiotropium in combination with olodaterol in patients with moderate to very severe COPD improves lung function and reduces breathlessness compared with the monocomponents [20].

It is important to understand how reducing hyperinflation with tiotropium/olodaterol treatment can help to decrease activity-related breathlessness. Measuring patient perception of symptoms is very informative in understanding how the information arising from the exercising locomotor and respiratory muscles is integrated by the central nervous system [38]. One approach used is to ask patients to rate their breathlessness during controlled in-clinic exercise tests using a scale such as the modified Borg scale (Table 2) [38, 39]. This scale is a simple numerical list from which patients are asked to rate their symptoms during exertion [40].

Treatment with tiotropium/olodaterol has consistently been found to decrease breathing discomfort, measured using the Borg dyspnoea scale during CWRCE. In the 6-week replicate MORACTO trials, tiotropium/olodaterol reduced breathing discomfort at isotime during CWRCE by 0.693 Borg units (P = 0.0001) compared with placebo [28]. The 12-week TORRACTO clinical trial found that treatment with tiotropium/olodaterol decreased breathing discomfort versus placebo at isotime during the CWRCE at week 6 (− 0.600 Borg units; 95% CI − 1.180, − 0.019; P = 0.0429) and a trend for decreased breathing discomfort at week 12 (− 0.348 Borg units; 95% CI − 0.936, 0.239; P = 0.2451) [29].

The 3-min constant speed shuttle test is an exercise test specifically designed to measure the effect of interventions on breathlessness during activity. Patients are asked to score their perception of breathlessness before, after and at prespecified time points during the shuttle test using the Borg scale [41, 42]. In contrast to the 6MWT, the walking speed is fixed, allowing breathlessness perception at the same exercise intensity to be compared before and after treatment. In a recent two-period crossover study, 6 weeks of treatment with tiotropium/olodaterol and tiotropium alone reduced the intensity of breathlessness at the end of the 3-min constant speed shuttle test (mean improvement − 1.325 units [95% CI − 1.594, − 1.056] and − 0.968 units [95% CI − 1.238, − 0.698], respectively) compared with baseline [30]. In this trial, a statistically significantly greater reduction in the intensity of breathlessness was observed with tiotropium/olodaterol versus tiotropium (treatment difference − 0.357 units; 95% CI − 0.661, − 0.053; P = 0.0217) [30]. Despite the between-treatment difference in dyspnoea score being relatively small, it was calculated that a number needed to treat (NNT) of 7 was necessary to achieve a clinically relevant improvement in activity-related breathlessness (at least a 1-point improvement in the modified Borg dyspnoea score) for tiotropium/olodaterol compared with tiotropium in one patient [30]. Considering the favourable safety profile of tiotropium/olodaterol, this NNT was felt to be clinically relevant [43].

Decrease in Breathlessness During Activities of Daily Life with Tiotropium/Olodaterol

Another approach to measure activity-related breathlessness is to use questionnaires that require patients to recall their symptoms during daily life [17]. The PHYSACTO trial utilised the Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire (CRQ), modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) questionnaire and Functional Performance Inventory Short Form questionnaire to assess the impact of interventions on breathlessness or their effect on daily activities. In this study, all patients were enrolled in a self-management behaviour modification programme and treated once daily with tiotropium/olodaterol (either alone or in combination with exercise training), placebo or tiotropium alone (Fig. 2) [44]. Treatment with tiotropium/olodaterol, with or without exercise training, reduced physical activity-related breathlessness, and patients reported less difficulty while performing physical activity of daily living compared with placebo [17].

Fig. 2.

PHYSACTO study design (NCT02085161) [44]. AM activity monitoring, BM behavioural monitoring, ExT exercise training, T tiotropium, T/O tiotropium/olodaterol, SMBM self-management behaviour modification.

Reproduced with permission from Troosters et al. [44]

As shown by improvements in the dyspnoea domain of the CRQ (CRQ-SAS dysp), tiotropium/olodaterol reduced breathlessness during activity versus baseline after 12 weeks, with adjusted mean changes ± SE in CRQ-SAS dysp of 0.71 ± 0.10 or 0.59 ± 0.10 either with or without exercise training, respectively (both P < 0.05 versus baseline) [17]. This was confirmed by an improvement in mMRC score observed at 12 weeks with tiotropium/olodaterol with or without exercise training (adjusted mean change ± SE versus placebo – 0.44 ± 0.13 [P = 0.001] and – 0.36 ± 0.13 [P = 0.007], respectively) [17]. Improving patients’ overall experience of physical activity by decreasing breathlessness and perceived difficulty of activity could be an important contributor to long-term adherence to an active lifestyle for patients with COPD, resulting in an improved quality of life [45].

Holistic Approach to Improving Physical Activity

COPD is a complex disease with multiple effects beyond the respiratory system. It is becoming apparent that increasing physical activity and reducing discomfort during physical activity requires a more holistic approach than solely providing adequate bronchodilation. Treatment should consider all aspects of the disease, including mental, physical and emotional health. Pulmonary rehabilitation and exercise programmes can improve patients’ physiology [46, 47], while counselling or psychological programmes support the change in behaviour that is needed for patients to be more active [48]. Increasing and maintaining physical activity has been demonstrated to have a positive impact not only on breathlessness but also on poor outcomes in patients with COPD, including risk of exacerbations, hospitalisation and mortality [11, 13–15].

Improving lung function and limb muscle function is expected to result in increased capacity to perform exercise and, potentially, in increased physical activity as measured by steps per day, average daily walking time and walking intensity [17]. Pulmonary rehabilitation, defined by the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society as ‘a comprehensive intervention based on a thorough patient assessment followed by patient-tailored therapies’ [46] plays an important role in the management of patients with COPD. The core of pulmonary rehabilitation includes exercise training, education and behaviour change, which are designed to improve the physical and psychological condition of people with chronic respiratory disease and to promote the long-term adherence to health-enhancing behaviours [46]. Rehabilitation programs help to decrease breathlessness, improve health-related quality of life and reduce healthcare utilisation [16, 49, 50]. However, although rehabilitation has been shown to enhance exercise tolerance in patients with COPD [51], this does not always guarantee the adoption of a more active lifestyle, particularly in the long term.

Pulmonary rehabilitation has been shown to be more effective when given in combination with bronchodilator therapy. In combination with tiotropium, pulmonary rehabilitation improved treadmill walking endurance time compared with pulmonary rehabilitation alone, and these improvements lasted up to 3 months after completion of the pulmonary rehabilitation programme [52]. Patient-reported involvement in physical activities was also significantly improved in patients taking tiotropium and participating in pulmonary rehabilitation compared with those taking placebo and pulmonary rehabilitation [53]. Pulmonary rehabilitation does have some limitations, one of which is that the effects diminish over time if the exercise training component of the intervention is not maintained. Long-term maintenance of the benefits of pulmonary rehabilitation require changes in patient health behaviour, taking into account personal needs, preferences and personal goals [16].

Behaviour-change interventions such as self-management behaviour modification programmes are designed to train and support patients, in collaboration with physicians and other healthcare professionals, via increased patient engagement and maintenance of exercise and physical activity [54]. The PHYSACTO study was the first COPD trial in which all patients received a self-management behaviour modification programme to examine the effect of bronchodilator therapy and exercise training on exercise capacity and physical activity (Fig. 2) [17]. In this study, tiotropium/olodaterol 5/5 µg significantly improved endurance time during an ESWT after 8 weeks of treatment compared with placebo, either with exercise training (treatment ratio versus placebo 1.46; 95% CI 1.20, 1.78; P = 0.0002) or without exercise training (treatment ratio versus placebo 1.29; 95% CI 1.06, 1.57; P = 0.0109) (Table 3) [17]. Tiotropium/olodaterol 5/5 µg also significantly improved IC compared with placebo, either with or without exercise training (Table 1) [17]. Furthermore, patients in this study showed significant improvement in adjusted mean distance walked ± SE during the 6MWT when treated with tiotropium/olodaterol 5/5 µg, with or without exercise training, after 8 weeks compared with placebo (27.33 ± 10.06 m [P = 0.007] and 21.03 ± 9.89 m [P = 0.034], respectively) [17]. After 12 weeks, self-management behaviour modification alone resulted in a clinically meaningful increase in physical activity, both in terms of steps per day (adjusted mean change from baseline ± SE, 1098 ± 325 steps per day, representing a 20% increase from baseline) and daily walking time (adjusted mean change from baseline ± SE, 10.86 ± 3.53 min/day, representing a 16% increase from baseline). These observed improvements in physical activity were not further increased with additional interventions [17]. Importantly, patients also perceived less breathing discomfort during physical activities of daily living when bronchodilation with tiotropium/olodaterol and exercise training were added to self-management behaviour modification [17]. This study highlights the need for combining behavioural interventions with optimal bronchodilation and pulmonary rehabilitation while improving and maintaining comfort during physical activities, with the hope of affecting long-term change.

The combination of self-management behaviour modification, exercise training and tiotropium/olodaterol demonstrated the largest effect on physical activity experience (assessed using the amount and difficulty domains of the daily version of the PROactive Physical Activity in COPD instrument) and breathlessness during daily life in patients with COPD [17]. This supports the concept that improving airflow, symptoms and the experience of physical activity, providing physical reconditioning with exercise training and addressing psychological factors are all important components to provide patients with the best chance of increasing and maintaining their physical activity.

Supporting Real-World Evidence

Several clinical trials have consistently demonstrated that treatment with tiotropium/olodaterol can make it easier for people with COPD to stay active by reducing symptoms and the difficulties related to physical activity [20, 22, 28, 29, 37]. However, data from clinical trials can be difficult to extrapolate to the general population because of the stringent inclusion criteria used to select participants for clinical trials. Real-world data complement evidence from clinical trials and help us to understand the effects of therapies in everyday clinical practice. With physical activity becoming more and more important in the management of patients with COPD, seeking to understand the best way to address this in everyday clinical practice has resulted in many observational studies. For example, an observational study carried out in a very large population from practices spread throughout Germany, including both urban and rural areas, investigated the effect of tiotropium/olodaterol on physical functioning using the 10-item Physical Functioning Questionnaire, which provides a measure of physical activity in daily living [55]. This study found that tiotropium/olodaterol improved physical function and health-related quality of life within 6 weeks of treatment over a broad range of disease severities in patients with COPD [55]. In a similar observational study evaluating tiotropium in a large German population, the observed improvements in physical function with tiotropium also had a positive effect on patients’ general condition, a physician-assessed measure of a patient’s overall clinical condition evaluated using the Physician’s Global Evaluation score [56]. More recently, patients receiving tiotropium/olodaterol in the OTIVACTO observational studies have, across several European countries, reported improvements in their general condition and ability to better manage their daily routines [57, 58]. These tiotropium/olodaterol observational studies complement the existing body of long-acting bronchodilator clinical trial data on which to base the choice of therapy to help improve quality of life for patients with COPD.

Conclusion

Overall, the tiotropium/olodaterol programme demonstrates that the introduction of dual bronchodilation with tiotropium/olodaterol reduces breathlessness during physical activity versus the monocomponents alone in patients with COPD, by reducing airway resistance and helping to increase the expiratory flow rate, therefore reducing the degree of hyperinflation [26, 28]. Tiotropium/olodaterol also improves lung function and reduces hyperinflation (marked by increases in IC) compared with tiotropium alone or placebo and increases exercise endurance capacity compared with placebo in patients with COPD, both in individual trials and in meta-analyses/pooled analyses. Although these changes do not always lead by themselves to an increase in the level of physical activity that patients perform in their daily lives, the data suggest that combining these positive effects of long-acting dual bronchodilation with behavioural and exercise training interventions offers the best chance for the adoption of an active lifestyle. These findings support the body of data showing consistent benefits of dual bronchodilation with tiotropium/olodaterol compared with tiotropium alone across a variety of endpoints and a wide range of patient groups.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Alan Hamilton of Boehringer Ingelheim (Canada) Ltd. and Wenqiong Xue of Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc, USA for their contributions to the development of the manuscript.

Funding

This analysis was funded by Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH (BI). The costs associated with its publication (Rapid Service Fee and Open Access Fee) were also covered by BI.

Medical Writing, Editorial and Other Assistance

Medical writing assistance, in the form of the preparation and revision of the draft manuscript, was supported financially by Boehringer Ingelheim and provided by Cindy Macpherson, PhD, of MediTech Media Ltd under the authors’ conceptual direction and based on feedback from the authors.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

François Maltais reports grants from AstraZeneca and GlaxoSmithKline, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi and Novartis during the conduct of this study, and personal fees for serving on speaker bureaus and consultation panels from Boehringer Ingelheim, Grifols and Novartis outside the submitted work. He is financially involved with Oxynov, a company which is developing an oxygen delivery system. Alberto de la Hoz is an employee of Boehringer Ingelheim. Richard Casaburi reports grants and personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca, Regeneron and Genetech outside the submitted work. Denis O’Donnell reports grants to his institution from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim and GlaxoSmithKline during the conduct of the study; and personal fees for serving on speaker bureaus, consultation panels and advisory boards from Almiral, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis and Pfizer outside the submitted work.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

References

- 1.Troosters T, Sciurba F, Battaglia S, et al. Physical inactivity in patients with COPD, a controlled multi-center pilot-study. Respir Med. 2010;104(7):1005–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marchetti N, Kaplan A. COPD in primary care: key considerations for optimized management: dyspnea and hyperinflation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: impact on physical activity. J Fam Pract. 2018;67(2 Suppl):S3–S10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanania NA, O'Donnell DE. Activity-related dyspnea in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: physical and psychological consequences, unmet needs, and future directions. Int J Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2019;14:1127–1138. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S188141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dekhuijzen R, Hass N, Liu J, Dreher M. Daily impact of COPD in younger and older adults: global online survey results from over 1300 patients. COPD. 2020;17(4):419–28. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Hutchinson A, Barclay-Klingle N, Galvin K, Johnson MJ. Living with breathlessness: a systematic literature review and qualitative synthesis. Eur Respir J. 2018;51(2):1701477. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01477-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramon MA, Ter Riet G, Carsin AE, et al. The dyspnoea-inactivity vicious circle in COPD: development and external validation of a conceptual model. Eur Respir J. 2018;52(3):1800079. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00079-2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palange P, Ward SA, Carlsen KH, et al. Recommendations on the use of exercise testing in clinical practice. Euro Respir J. 2007;29(1):185–209. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00046906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casaburi R. Activity promotion: a paradigm shift for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease therapeutics. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2011;8(4):334–337. doi: 10.1513/pats.201101-001RM. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gea J, Pascual S, Casadevall C, Orozco-Levi M, Barreiro E. Muscle dysfunction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: update on causes and biological findings. J Thorac Dis. 2015;7(10):E418–E438. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.08.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moxham J, Jolley C. Breathlessness, fatigue and the respiratory muscles. Clin Med. 2009;9(5):448–452. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.9-5-448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garcia-Aymerich J, Lange P, Benet M, Schnohr P, Antó JM. Regular physical activity reduces hospital admission and mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a population based cohort study. Thorax. 2006;61(9):772–778. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.060145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.ZuWallack R, Esteban C. Understanding the impact of physical activity in COPD outcomes: moving forward. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(5):1107–1109. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00151014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waschki B, Kirsten A, Holz O, et al. Physical activity is the strongest predictor of all-cause mortality in patients with COPD: a prospective cohort study. Chest. 2011;140(2):331–342. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-2521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mullerova H, Lu C, Li H, Tabberer M. Prevalence and burden of breathlessness in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease managed in primary care. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e85540. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Albarrati AM, Gale NS, Munnery MM, Cockcroft JR, Shale DJ. Daily physical activity and related risk factors in COPD. BMC Pulm Med. 2020;20(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12890-020-1097-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (2020 report). 2019. https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/GOLD-2020-REPORT-ver1.0wms.pdf. Accessed 15 June 2020.

- 17.Troosters T, Maltais F, Leidy N, et al. Effect of bronchodilation, exercise training, and behavior modification on symptoms and physical activity in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;198(8):1021–1032. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201706-1288OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anzueto A, Miravitlles M. The role of fixed-dose dual bronchodilator therapy in treating COPD. Am J Med. 2018;131(6):608–622. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rogliani P, Calzetta L, Braido F, et al. LABA/LAMA fixed-dose combinations in patients with COPD: a systematic review. Int J Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2018;13:3115–3130. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S170606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buhl R, Maltais F, Abrahams R, et al. Tiotropium and olodaterol fixed-dose combination versus mono-components in COPD (GOLD 2–4) Eur Respir J. 2015;45(4):969–979. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00136014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beeh KM, Westerman J, Kirsten AM, et al. The 24-h lung-function profile of once-daily tiotropium and olodaterol fixed-dose combination in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2015;32:53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2015.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh D, Ferguson GT, Bolitschek J, et al. Tiotropium + olodaterol shows clinically meaningful improvements in quality of life. Respir Med. 2015;109(10):1312–1319. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2015.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones P, Miravitlles M, van der Molen T, Kulich K. Beyond FEV1 in COPD: a review of patient-reported outcomes and their measurement. Int J Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2012;7:697–709. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S32675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garcia-Rio F, Lores V, Mediano O, et al. Daily physical activity in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is mainly associated with dynamic hyperinflation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180(6):506–512. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200812-1873OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Glaab T, Vogelmeier C, Buhl R. Outcome measures in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): strengths and limitations. Respir Res. 2010;11:79. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-11-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomas M, Decramer M, O'Donnell DE. No room to breathe: the importance of lung hyperinflation in COPD. Primary Care Respir J. 2013;22(1):101–111. doi: 10.4104/pcrj.2013.00025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Langer D, Ciavaglia CE, Neder JA, Webb KA, O'Donnell DE. Lung hyperinflation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: mechanisms, clinical implications and treatment. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2014;8(6):731–749. doi: 10.1586/17476348.2014.949676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'Donnell DE, Casaburi R, Frith P, et al. Effects of combined tiotropium/olodaterol on inspiratory capacity and exercise endurance in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2017;49(4):1601348. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01348-2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maltais F, O'Donnell D, Galdiz Iturri JB, et al. Effect of 12 weeks of once-daily tiotropium/olodaterol on exercise endurance during constant work-rate cycling and endurance shuttle walking in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2018;12:1–13. doi: 10.1177/1753465818755091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maltais F, Aumann JL, Kirsten A-M, et al. Dual bronchodilation with tiotropium/olodaterol further reduces activity-related breathlessness versus tiotropium alone in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2019;53(3):1802049. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02049-2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vilaró J, Resqueti VR, Fregonezi GAF. Clinical assessment of exercise capacity in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Brazil J Phys Ther. 2008;12(4):249–259. doi: 10.1590/S1413-35552008000400002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cazzola M, MacNee W, Martinez FJ, et al. Outcomes for COPD pharmacological trials: from lung function to biomarkers. Eur Respir J. 2008;31(2):416–469. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00099306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.ATS Committee on Proficiency Standards for Clinical Pulmonary Function Laboratories ATS statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166(1):111–117. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.166.1.at1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Celli B, Tetzlaff K, Criner G, et al. The 6-minute-walk distance test as a chronic obstructive pulmonary disease stratification tool. Insights from the COPD Biomarker Qualification Consortium. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194(12):1483–1493. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201508-1653OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Puente-Maestu L, Palange P, Casaburi R, et al. Use of exercise testing in the evaluation of interventional efficacy: an official ERS statement. Eur Respir J. 2016;47(2):429–460. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00745-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Borenstein M, Hedges L, Higgins J, Rothstein H. Introduction to meta-analysis. Chichester: Wiley; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 37.O'Donnell DE, Fluge T, Gerken F, et al. Effects of tiotropium on lung hyperinflation, dyspnoea and exercise tolerance in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2004;23(6):832–840. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00116004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Borg G. Psychophysical scaling with applications in physical work and the perception of exertion. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1990;16(Suppl 1):55–58. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hareendran A, Leidy NK, Monz BU, Winnette R, Becker K, Mahler DA. Proposing a standardized method for evaluating patient report of the intensity of dyspnea during exercise testing in COPD. Int J Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2012;7:345–355. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S29571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Williams N. The Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) scale. Occup Med. 2017;67(5):404–405. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqx063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sava F, Perrault H, Brouillard C, et al. Detecting improvements in dyspnea in COPD using a three-minute constant rate shuttle walking protocol. COPD. 2012;9(4):395–400. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2012.674164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perrault H, Baril J, Henophy S, Rycroft A, Bourbeau J, Maltais F. Paced-walk and step tests to assess exertional dyspnea in COPD. COPD. 2009;6(5):330–339. doi: 10.1080/15412550903156317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Citrome L, Ketter TA. When does a difference make a difference? Interpretation of number needed to treat, number needed to harm, and likelihood to be helped or harmed. Int J Clin Pract. 2013;67(5):407–411. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Troosters T, Bourbeau J, Maltais F, et al. Enhancing exercise tolerance and physical activity in COPD with combined pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions: PHYSACTO randomised, placebo-controlled study design. BMJ Open. 2016;6(4):e010106. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jones GL. Quality of life changes over time in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2016;22(2):125–129. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spruit MA, Singh SJ, Garvey C, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: key concepts and advances in pulmonary rehabilitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(8):e13–e64. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201309-1634ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McCarthy B, Casey D, Devane D, Murphy K, Murphy E, Lacasse Y. Pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2:CD003793. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003793.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leidy NK, Kimel M, Ajagbe L, Kim K, Hamilton A, Becker K. Designing trials of behavioral interventions to increase physical activity in patients with COPD: insights from the chronic disease literature. Respir Med. 2014;108(3):472–481. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2013.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Corhay JL, Dang DN, Van Cauwenberge H, Louis R. Pulmonary rehabilitation and COPD: providing patients a good environment for optimizing therapy. Int J Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2014;9:27–39. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S52012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ries AL, Bauldoff GS, Carlin BW, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation: joint ACCP/AACVPR evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2007;131(5):4S–42S. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Osadnik CR, Loeckx M, Louvaris Z, et al. The likelihood of improving physical activity after pulmonary rehabilitation is increased in patients with COPD who have better exercise tolerance. Int J Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2018;13:3515–3527. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S174827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Casaburi R, Kukafka D, Cooper CB, Witek TJ, Jr, Kesten S. Improvement in exercise tolerance with the combination of tiotropium and pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with COPD. Chest. 2005;127(3):809–817. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.3.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kesten S, Casaburi R, Kukafka D, Cooper CB. Improvement in self-reported exercise participation with the combination of tiotropium and rehabilitative exercise training in COPD patients. Int J Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2008;3(1):127–136. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S2389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bourbeau J, Lavoie KL, Sedeno M. Comprehensive self-management strategies. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;36(4):630–638. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1556059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sauer R, Hansel M, Buhl R, Rubin RA, Frey M, Glaab T. Impact of tiotropium + olodaterol on physical functioning in COPD: results of an open-label observational study. Int J Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2016;11:891–898. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S103023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rau-Berger H, Mitfessel H, Glaab T. Tiotropium Respimat® improves physical functioning in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2010;5:367–373. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S14082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Steinmetz KO, Abenhardt B, Pabst S, et al. Assessment of physical functioning and handling of tiotropium/olodaterol Respimat® in patients with COPD in a real-world clinical setting. Int J Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2019;14:1441–1453. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S195852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Valipour A, Tamm M, Kociánová J, et al. Improvement of self-reported physical functioning with tiotropium/olodaterol in Central and Eastern European COPD patients. Int J Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2019;14:2343–2354. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S204388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mahler DA, Witek TJ., Jr The MCID of the transition dyspnea index is a total score of one unit. COPD. 2005;2(1):99–103. doi: 10.1081/COPD-200050666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jones PW. St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire: MCID. COPD. 2005;2(1):75–79. doi: 10.1081/COPD-200050513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schunemann HJ, Puhan M, Goldstein R, Jaeschke R, Guyatt GH. Measurement properties and interpretability of the Chronic Respiratory disease Questionnaire (CRQ) COPD. 2005;2(1):81–89. doi: 10.1081/COPD-200050651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Puhan MA, Chandra D, Mosenifar Z, et al. The minimal important difference of exercise tests in severe COPD. Eur Respir J. 2011;37(4):784–790. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00063810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Singh SJ, Jones PW, Evans R, Morgan MDL. Minimum clinically important improvement for the incremental shuttle walking test. Thorax. 2008;63(9):775–777. doi: 10.1136/thx.2007.081208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pepin V, Laviolette L, Brouillard C, et al. Significance of changes in endurance shuttle walking performance. Thorax. 2011;66(2):115–120. doi: 10.1136/thx.2010.146159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Revill SM, Morgan MDL, Singh SJ, Williams J, Hardman AE. The endurance shuttle walk: a new field test for the assessment of endurance capacity in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 1999;54:213–222. doi: 10.1136/thx.54.3.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ries AL. Minimally clinically important difference for the UCSD Shortness of Breath Questionnaire, Borg Scale, and Visual Analog Scale. COPD. 2005;2(1):105–110. doi: 10.1081/COPD-200050655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jones PW, Beeh KM, Chapman KR, Decramer M, Mahler DA, Wedzicha JA. Minimal clinically important differences in pharmacological trials. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189(3):250–255. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201310-1863PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]