Abstract

Breast cancer (BC) risk for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers varies by genetic and familial factors. About 50 common variants have been shown to modify BC risk for mutation carriers. All but three, were identified in general population studies. Other mutation carrier-specific susceptibility variants may exist but studies of mutation carriers have so far been underpowered. We conduct a novel case-only genome-wide association study comparing genotype frequencies between 60,212 general population BC cases and 13,007 cases with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. We identify robust novel associations for 2 variants with BC for BRCA1 and 3 for BRCA2 mutation carriers, P < 10−8, at 5 loci, which are not associated with risk in the general population. They include rs60882887 at 11p11.2 where MADD, SP11 and EIF1, genes previously implicated in BC biology, are predicted as potential targets. These findings will contribute towards customising BC polygenic risk scores for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers.

Subject terms: Breast cancer, Cancer epidemiology, Cancer genetics, Risk factors

Breast cancer risk for BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation carriers varies depending on other genetic factors. Here, the authors perform a case-only genome-wide association study and highlight novel loci associated with breast cancer risk for BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation carriers.

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is the most common cancer in women worldwide1 and BC family history is one of the most important risk factors for the disease. Women with a history of BC in a first-degree relative are about two times more likely to develop BC than women without a family history2. Around 15–20% of the familial risk of BC can be explained by rare mutations in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes3. A recent prospective cohort study estimated the cumulative risk of BC by 80 years to be 72% for BRCA1 mutation carriers and 69% for BRCA2 mutation carriers4. This study also demonstrated that BC risk for mutation carriers varies by family history of BC in first and second degree relatives, suggesting the existence of other genetic factors that modify BC risks4.

A total of 179 common BC susceptibility single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) or small insertions or deletions (INDELs) have been identified through genome-wide association studies (GWAS) in the general population1,5–35. Although risk alleles at individual SNPs (hereafter used as a generic term to refer to common variants, which also includes the small INDELs) are associated with modest increases in BC risk, it has been shown that they combine multiplicatively on risk, resulting in substantial levels of BC risk stratification in the population36–38. Similarly, more than 50 of the common genetic BC susceptibility variants have also been shown to be associated with BC for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers5,6,15,18,20,39–48 and their joint effects, summarised as polygenic risk scores (PRS), result in large differences in the absolute risks of developing BC for mutation carriers at the extremes of the PRS distribution49. BC GWAS for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers have been carried out through the Consortium of Investigators of Modifiers of BRCA1/2 (CIMBA)50. However, despite the large number of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers included, the power to detect genetic modifiers of risk remains limited in comparison to that available in the general population7. To date, no variants specifically associated with BC risk for BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers have been identified.

Here, we apply a novel strategy using a case-only GWAS design51,52, in which SNP genotype frequencies in 7,257 BRCA1 and 5,097 BRCA2 mutation carrier BC cases are compared to those in 60,212 BC cases from the Breast Cancer Association Consortium (BCAC), unselected for mutation status. We aim (1) to identify novel SNPs that modify BC risk for BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers but are not associated with risk in the general population and (2) for the known 179 BC susceptibility SNPs, assess whether there is evidence of an interaction between the SNPs and BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and therefore evaluate whether the SNP effect size estimates applicable to mutation carriers are different.

We identify robust novel associations for 2 variants with BC for BRCA1 and 3 for BRCA2 mutation carriers, P < 10−8, at 5 loci, which are not associated with risk in the general population. They include rs60882887 in 11p11.2 where MADD, SP11 and EIF1, genes previously implicated in BC biology, are predicted as potential targets. These findings will contribute towards customising BC PRS for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers.

Results

Sample characteristics

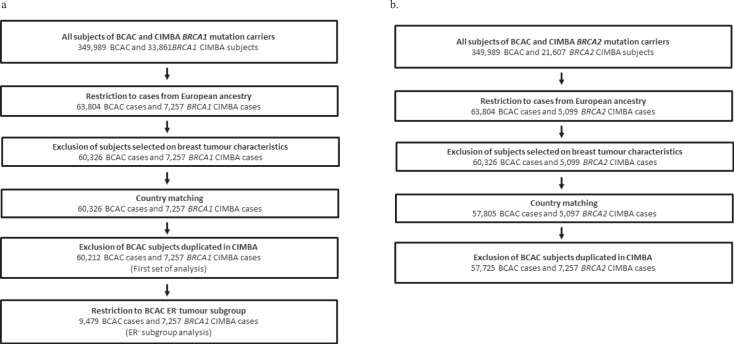

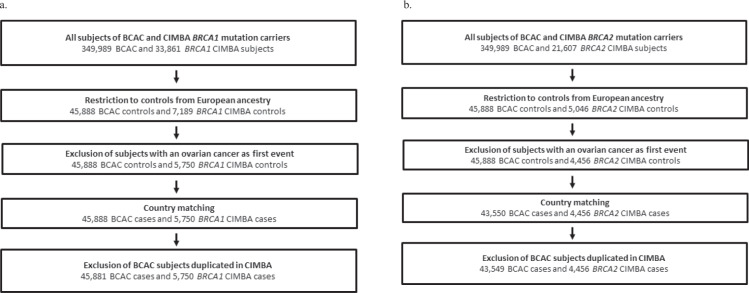

A total of 60,212 BCAC cases and 7,257 BRCA1 mutation carrier cases were available for the BRCA1 case-only analyses and 57,725 BCAC cases and 5,097 BRCA2 mutation carrier cases were available for the BRCA2 case-only analyses (Fig. 1). A total of 45,881 BCAC controls and 5,750 unaffected BRCA1 mutation carriers were available for the BRCA1 control-only analyses and 43,549 BCAC controls and 4,456 unaffected BRCA2 mutation carriers for the BRCA2 control-only analyses (see Fig. 2). Only women of European ancestry were included with 60.9% samples from European countries, 31.1% from the USA, 6.1% from Australia and 1.7% from Israel (Supplementary Tables 1–4). The mean age at BC diagnosis for mutation carrier cases in CIMBA was 42.5 years (40.9 for BRCA1 mutation carriers; 44.1 for BRCA2 mutation carriers) and 58.4 years for cases in BCAC.

Fig. 1. Case-only sample selection.

Sample selection for a BRCA1 and b BRCA2 case-only analysis. *Four studies were excluded because they were included in clinical trials based on breast tumour characteristics as HER-2 receptor status (see Supplementary Table 2).

Fig. 2. Control-only sample selection.

Sample selection for a BRCA1 and b BRCA2 control-only analysis.

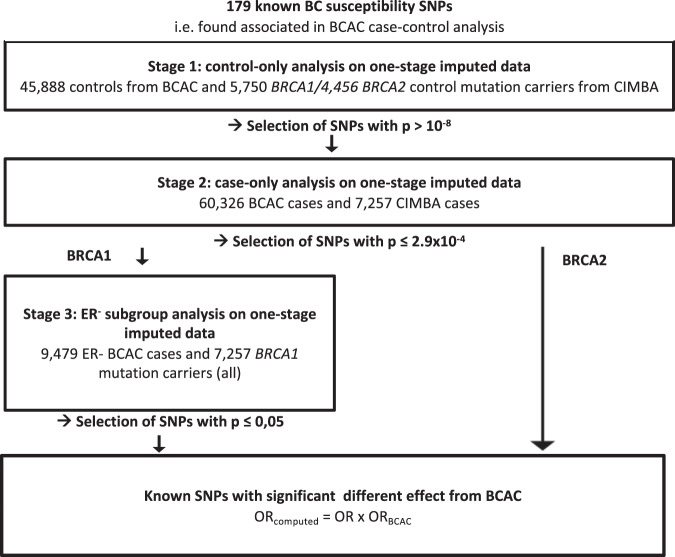

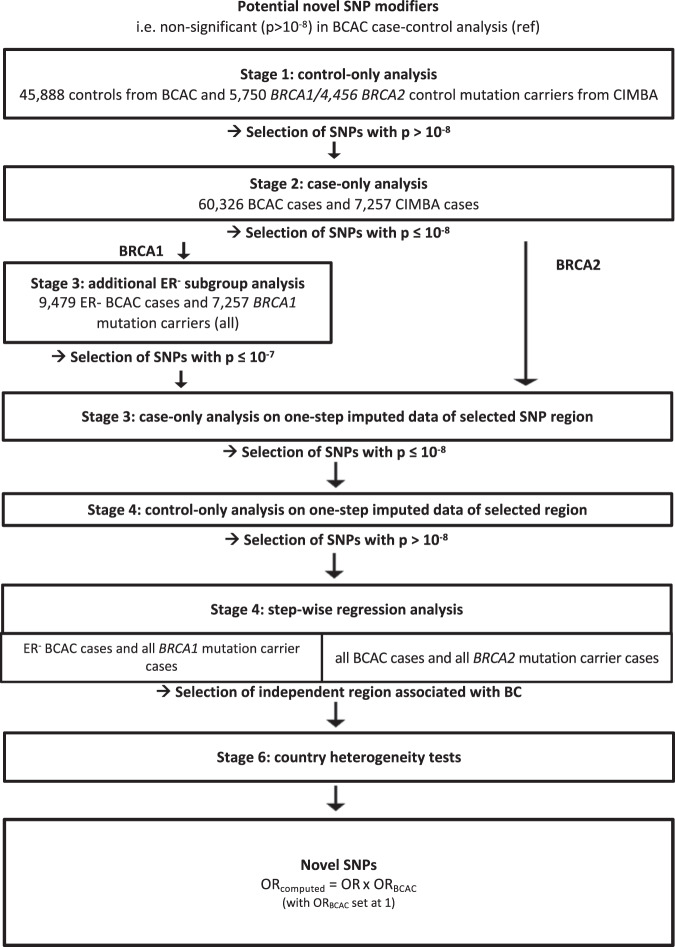

The analytical process for assessing interactions with known BC susceptibility SNP is summarised in Fig. 3 and for the detection of novel modifiers in Fig. 4.

Fig. 3. Analytical process for known BC susceptibility SNPs.

Strategy followed for analysing the associations for the 179 known BC susceptibility SNPs.

Fig. 4. Analytical process for identifying novel modifiers.

Strategy followed for identifying potentially novel SNP modifier.

Independence of SNP frequency with mutation carrier status

Under a case-only study design, it is important to establish independence between the SNPs and BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carrier status53. This was assessed a genome-wide level using a control-only analysis which included controls from BCAC and unaffected mutation carriers from CIMBA with SNP data imputed based on the 1,000 genomes project. Genotypes had been imputed separately by each consortium7,50. In the analysis of BRCA1 mutation carriers, 2,164 SNPs were excluded because they were located in or within 500 kb of BRCA1. 2,070 SNPs were excluded from further analyses because they showed associations at p < 10−8 with BRCA1 mutation carrier status in the control-only analysis (2,012 SNPs located on chromosome 17 and 58 on other chromosomes). In the analysis of BRCA2 mutation carriers, 2,947 SNPs were excluded because they were located in or within 500 kb of BRCA2. A further 626 SNPs were excluded from further analyses because they were found to be associated with BRCA2 mutation carrier status in the control-only analysis (566 SNPs on chromosome 13, and 60 on other chromosomes). A total of 9,068,301 SNPs remained for the BRCA1case-only association analysis and 9,043,830 SNPs for the BRCA2case-only analysis.

Interactions with known BC susceptibility SNPs

Based on published data, 179 SNPs were considered as established BC susceptibility SNPs (Fig. 3); 158 SNPs were associated with overall BC risk35 and 21 additional SNPs were found to be associated through studies in ER-negative breast cancer48 (see Supplementary Table 11 in Milne et al.48). One of the 158 SNPs, rs11571833 located within BRCA2 was excluded from the BRCA2 analysis. The detailed results are shown in Supplementary Data 1–3.

For BRCA1 mutation carriers, previous studies have demonstrated heterogeneity in the associations of the SNPs with ER-positive and ER-negative breast cancer35. Since BRCA1 mutation carriers develop primarily ER-negative BC, to comprehensively assess the evidence of interaction with BRCA1 mutation status, we followed a two-step process; we first assessed the associations using all BC cases from BCAC and then we restricted the comparison to BCAC ER-negative BC cases. Of the 158 SNPs35, 59 were associated with BRCA1 mutation carrier status when compared to all BC cases (P < 0.05, Supplementary Data 1). However, after adjusting for multiple testing, only four of these SNPs were associated (P < 2.7 × 10−4) and also showed evidence of association (P < 0.05) when compared with ER-negative BC cases (Table 1). Two additional SNPs on chromosome 1 and 6 (chr1_10566215_A_G and rs17529111) were associated at P < 2.7 × 10−4 with BRCA1 mutation status only when compared with ER-negative BCAC cases. The OR estimates for association with BRCA1 mutation status for these six SNPs were similar under both case-only analyses (all BC and ER-negative BC cases analyses) and varied from 0.85 to 1.07, suggesting that the magnitude of their associations with BC risk for BRCA1 mutation carriers differs from that observed in the general population. For the other 152 SNPs, there was no evidence of association with BRCA1 mutation status when compared against the ER-negative BC cases from BCAC (Supplementary Data 1), suggesting that the OR estimated using case-control data from BCAC are also applicable to BRCA1 mutation carriers.

Table 1.

Known BC susceptibility SNPs demonstrating associations in the BRCA1 case-only analysis.

| Location | SNP namea | Chrb | Positionc | Nearest gene | Estimated effect allele | Referent allele | Frequencyd | r2 | ORe | Pf | ORER¯g | PER-h | ORBCACi | PBCACj | ORcomputedk | Variation in riskl |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All BC SNPs | ||||||||||||||||

| 1p22.3 | rs17426269 | 1 | 88156923 | – | A | G | 0.16 | 1 | 0.90 | 2.70e−04 | 0.92 | 4.22e−02 | 1.05 | 1.70e−04 | 0.95 | IOD |

| 8q24.21 | rs13281615 | 8 | 128355618 | – | G | A | 0.43 | 1 | 0.91 | 1.20e−05 | 0.94 | 4.14e−02 | 1.11 | 5.00e−28 | 1.01 | TT1 |

| 10q22.3 | chr10_80841148_C_T | 10 | 80841148 | ZMZ1 | T | C | 0.40 | 1 | 0.91 | 2.20e−06 | 0.91 | 1.01e−03 | 0.93 | 1.10e−14 | 0.84 | ISD |

| 16q12.1 | chr16_52599188_C_T | 16 | 52599188 | TOX3 | T | C | 0.29 | 1 | 0.85 | 1.80e−13 | 0.91 | 2.80e−03 | 1.23 | 7.00e−88 | 1.04 | TT1 |

| ER- BC SNPs | ||||||||||||||||

| 1p36.22 | chr1_10566215_A_G | 1 | 10566215 | PEX14 | G | A | 0.32 | 1 | 1.07 | 1.30e−03 | 1.12 | 1.10e−04 | 0.94 | 1.80e−09 | 1.05 | TT1 |

| 6q14.1 | rs17529111 | 6 | 82128386 | – | C | T | 0.23 | 0.96 | 0.92 | 7.70e−04 | 0.86 | 1.96e−05 | 1.02 | 4.20e−02 | 0.88 | IOD |

| 8p23.3 | rs66823261 | 8 | 170692 | RPL23AP53 | C | T | 0.23 | 0.92 | – | – | 0.88 | 2.37e−04 | 1.09 | 5.09e−09 | 0.96 | TT1 |

Considering SNPs with known BC (Michailidou et al.)35 and ER-negative-specific BC (Milne et al.)48 associations in the general population.

All BC SNPs: SNPs associated with all BC in the general population.

N = 67,469 breast cancer cases (60,212 BCAC cases and 7,257 BRCA1 mutation carrier cases).

ER- BC SNPs: SNPs associated with ER-negative BC in the general population.

N = 16,736 breast cancer cases (9,479 BCAC ER- cases and 7,257 BRCA1 mutation carrier cases).

TT1 tends to 1, ISD increase in same direction, IOD increase in opposite direction.

aAfter allowing for multiple testing, α* = 2.7 × 10−4.

bChromosome.

cBuild 37 positions.

dFrequency of the allele for which effect is estimated in BCAC cases (OncoArray dataset).

ePer allele odds ratio estimated in the case-only analysis.

fp-value in the case-only analysis (after allowing for multiple testing, p = 2.7 × 10−4).

gPer allele odds-ratio estimated in the case-only ER-negative subgroup analysis. OR values were computed from a two sided logistic regression using a 1 degree freedom likelihood ratio test (1 df lrtest) adjusted for age at BC diagnosis, country and the first four principal components.

hp-value in the case-only ER-negative subgroup analysis.

iPer allele odds-ratio estimated in BCAC (Michailidou et al.)35, except for * (Milne et al.)48.

jp-value in BCAC (Michailidou et al.)35, except for * (Milne et al.)48. For SNPs with PBCAC > 10−8, significance was attained in merging data of Oncoarray, iCOGS and 11 different breast cancer GWAS in Michailidou et al.35 or Milne et al.48.

kPer allele computed odds-ratio (OR × ORBCAC).

lCompared with Michailidou et al’s OR estimates35.

Among the 21 ER-negative SNPs reported in Milne et al.48, only one (rs66823261) demonstrated significant evidence of association in the ER-negative case-only analysis (OR = 0.88, p < 2.7 × 10−4) (Table 1 and Supplementary Data 2). For the 20 other showing no association, the ORs estimated in Milne et al.48 would be applicable to BRCA1 mutation carriers.

To estimate the association of the seven significant SNPs with BC for BRCA1 mutation carriers (ORcomputed), the OR estimated using case-control data from BCAC (ORBCAC) was multiplied by the OR estimated using the case-only analysis (OR). For three SNPs, rs17426269, chr10_80841148_C_T and rs17529111, the magnitude of the association with BC for BRCA1 mutation carriers was greater than that in the general population (ORBCAC) and for two of these three, the ORcomputed was in the opposite direction than the ORBCAC (Table 1). For the four other SNPs (rs13281615, chr16_52599188_C_T, chr1_10566215_A_G and rs66823261), the estimated interaction OR resulted in the OR for associations with BRCA1 BC risk being closer to 1 (Table 1).

Among the remaining 172 SNPs (152 + 20) that showed no associations with BRCA1 mutation status, the estimated ORcomputed was smaller (i.e., closer to 1) than those estimated in the general population (ORBCAC) for 146 SNPs (85%, Supplementary Data 1 and 2). Based on the analysis of ER− tumours, the proportion of SNPs for which the ORcomputed was closer to 1 than the ORBCAC estimates was 59% (Supplementary Data 1 and 2).

For BRCA2 mutation carriers, among the 157 SNPs known to be associated with BC risk in the general population, 43 were associated with BRCA2 mutation carrier status at P < 0.05 in the case-only analysis that included all BCAC BC cases (Supplementary Data 3). However, only three SNPs (rs62355902, rs10759243 and chr22_40876234_C_T) showed associations after adjusting for multiple testing (P < 2.7 × 10−4) with OR estimates in the range of 0.88 to 0.89 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Known BC susceptibility SNPs demonstrating associations in the BRCA2 case-only analysis.

| Location | SNP namea | Chrb | Positionc | Nearest gene | Estimated effect allele | Referent allele | Frequencyd | r2 | ORe | Pf | ORBCACg | PBCACh | ORcomputedi | Variation in riskj |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5q11.2 | rs62355902 | 5 | 56053723 | MAP3K1 | T | A | 0.18 | 0.98 | 0.89 | 1.10e−04 | 1.18 | 8.50e−42 | 1.05 | TT1 |

| 9q31.2 | rs10759243 | 9 | 110306115 | RP11-438P9.2 | A | C | 0.31 | 1 | 0.89 | 4.60e−06 | 1.06 | 4.20e−10 | 0.95 | TT1 |

| 22q13.1 | chr22_40876234_C_T | 22 | 40876234 | MKL1 | C | T | 0.11 | 1 | 0.88 | 2.8e−04 | 1.12 | 5.70e−16 | 0.98 | TT1 |

N = 62,822 breast cancer cases (57,725 BCAC cases and 5,097 BRCA2 mutation carrier cases).

Considering SNPs with known BC (Michailidou et al.)35 associations in the general population.

TT1 tends to 1, ISD increase in same direction, IOD increase in opposite direction.

aAfter allowing for multiple testing, α* = 2.7 × 10−4.

bChromosome.

cBuild 37 position.

dFrequency of the allele for which effect is estimated in BCAC cases (OncoArray dataset).

ePer allele odds ratio estimated in the case-only analysis. OR values were computed from a two sided logistic regression using a 1 df lrtest adjusted for age at BC diagnosis, country and the first four principal components.

fp-value in the case-only analysis (after allowing for multiple testing, p* = 2.7 × 10−4).

gPer allele odds-ratio estimated in BCAC (Michailidou et al.)35.

hp-value in BCAC (Michailidou et al.)35. For SNPs with PBCAC > 10−8, significance was attained in merging data of Oncoarray, iCOGS and 11 different breast cancer GWAS in Michailidou et al.35.

iPer allele computed odds-ratio (OR × ORBCAC).

jCompared with Michailidou et al’s OR estimates35.

For these three SNPs, the observed interaction resulted in the magnitude of association with BC risk for BRCA2 mutation carriers (ORcomputed) being closer to 1 (Table 2).

Of the 154 SNPs that showed no significant associations with BRCA2 mutation status, 79% had ORs of BC for BRCA2 mutation carriers (ORcomputed) that were closer to 1 when compared to the ORs estimated using data in the general population (ORBCAC) (Supplementary Data 3).

Novel SNP modifiers

To identify novel SNPs that modify BC risks for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers, we used a case-only design to investigate the associations of SNPs that had not been previously shown to be associated with BC in the general population (Fig. 4).

For BRCA1 mutation carriers, a total of 924 SNPs showed associations at P < 10−8 in all BC case-only analysis. To ensure that none of these associations are driven by differences in the distribution of ER-positive and ER-negative tumours in BCAC cases, an intermediate step was applied, in which we re-analysed the associations after restricting the BCAC data to only ER-negative cases. 220 of these SNPs remained significant at P < 10−7 located in 11 distinct genomic regions. SNPs were considered to belong to the same region if they were located within 500 kb of each other.

To ensure that none of these associations was driven by differences in the genotype imputation in the BCAC and CIMBA data (which had been carried out separately), all the SNPs in these 11 distinct genomic regions were re-imputed in the BCAC and CIMBA samples jointly and the associations for all SNPs in the regions were re-assessed in the control-only and case-only analyses. After the exclusion of 614 SNPs (613 on chromosome 17) that showed associations in the control-only analysis, 71 SNPs in two regions remained significant at P < 10–8 (Supplementary Data 4) in the case-only analyses including all BCAC cases. None of these SNPs had been previously reported in GWAS in the general population (p-values of association ranged from 0.51 to 5.9 × 10−5 with effect sizes in the range 0.96–1.04 in BCAC case-control analyses)35,48. A forward step-wise regression analysis within each of these two regions (restricted to the SNPs exhibiting associations at p < 10−8) starting with the most significant SNP and adding sequentially the other SNPs, identified a set of four conditionally independent SNPs (top SNPs) (Table 3): all SNPs were imputed, with r2 > 0.5, and had minor allele frequency (MAF) > 10%. Three of the top SNPs are located in 17q21.2. rs58117746 is an insertion of 16 bp within an exon of KRTAP4-5 leading to a frameshift of the amino acid sequence. rs5820435 and rs11079012 are both intronic and located in LEPREL4 (also named P3H4) and JUP, respectively, while rs80221606 is intronic and located in 11p11.2, within CELF1. The OR estimates of these four top SNPs ranged from 0.78 to 1.22. All showed evidence of heterogeneity in the OR by country (P < 0.05) (Table 3); however, in a leave-one-out analysis, in which each country was left out in turn, the overall associations remained similar (Supplementary Fig. 1 and 2) suggesting that no individual country had a big impact on the observed associations.

Table 3.

List of potential novel SNP modifiers associated in the case-only analysis for BRCA1 mutation carriers.

| Location | SNP namea | Chrb | Positionc | Nearest gene | Localisation | Estimated effect allele | Referent allele | r² d | Frequencye | ORf | Pg | ORERh | PER¯i | HRCIMBAj | PCIMBAk | ORBCACl | PBCACm | Phetn | Target geneo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11p11.2 | rs80221606 | 11 | 47560211 | CELF1 | Intronic | AT | A | 0.76 | 0.10 | 0.78 | 1.12e−10 | 0.76 | 6.36e−07 | 0.98 | 7.60e−01 | 1.04 | 0.01 | 1.39e−03 | Level 2 |

| 17q21.2 | rs58117746 | 17 | 39305775 | KRTAP4-5 | Pepshift | TGGCAGCAGCTGGGGC | T | 0.60 | 0.39 | 1.18 | 4.33e−10 | 1.15 | 7.71e−05 | 1.05 | 2.20e−02 | 1.02 | 0.26 | 4.60e−04 | – |

| 17q21.2 | rs5820435 | 17 | 39961558 | LEPREL4 | Intronic | A | C | 0.51 | 0.45 | 0.82 | 9.55e−12 | 0.85 | 7.71e−05 | 1.01 | 9.00e−01 | 1.02 | 0.07 | 1.06e−08 | – |

| 17q21.2 | rs11079012 | 17 | 39912880 | JUP | Intronic | G | C | 0.66 | 0.31 | 1.17 | 7.06e−09 | 1.18 | 2.35e−05 | 0.98 | 3.10e−01 | 1.01 | 0.51 | 1.15e−07 | Level 2 |

N = 67,469 breast cancer cases (60,212 BCAC cases and 7,257 BRCA1 mutation carrier cases)

aThe most significant SNP of each region after allowing for multiple testing, α* = 10−8

bChromosome.

cBuild 37 position.

dImputation accuracy.

eFrequency of the allele for which effect is estimated in BCAC cases (OncoArray dataset).

fPer allele odds ratio estimated in the case-only analysis. OR values were computed from a two sided logistic regression using a 1 df lrtest adjusted for age at BC diagnosis, country and the first four principal components.

gp-value in the case-only analysis.

hPer allele odds-ratio estimated in the case-only ER-negative subgroup analysis.

ip-value in the case-only ER-negative subgroup analysis.

jPer allele hazard ratio estimated in CIMBA cohort analysis.

kp-value found in CIMBA cohort analysis.

lPer allele odds-ratio estimated in BCAC (Michailidou et al.)35.

mp-value in BCAC (Michailidou et al.)35. For SNPs with PBCAC > 10−8, significance was attained in merging data of Oncoarray, iCOGS and 11 different breast cancer GWAS in Michailidou et al.35.

np-value of the heterogeneity test by country.

oINQUISIT score level: 1 = most functional evidence supporting a potential link between CCVs and target gene.

For BRCA2 mutation carriers, the case-only analysis identified 273 SNPs, located across 22 regions, with evidence of association at P < 10−8. After the joint re-imputation of the SNPs in these 22 regions, only 102 SNPs located in four regions (2p14, 13q13.1, and 13q13.2) remained associated at P < 10–8 (Supplementary Data 5). The step-wise regression analysis suggested that associations in each of the four regions were driven by a single variant (top SNPs) (Table 4). All four variants were imputed (with r2 > 0.5) and had MAF higher than 5%. At 2p14, rs12470785 (r2 = 0.98) is within an intron of ETAA1. At 13q13.1, rs79183898 (r2 = 0.84) is located between B3GALTL and RXFP2 and rs736596 (r2 = 0.66) is within an intron of STARD13. At 13q13.2, rs4943263 (r2 = 0.99) is located between RP11-266E6.3 and RP11-307O13.1. None of these SNPs had been previously reported to be associated with BC risk in BCAC studies in the general population (p-values from 0.01 to 0.90 in BCAC case-control analyses)35,48. The OR estimates of these four SNPs ranged from 0.85 to 1.37. All showed evidence of heterogeneity in the OR by country at p = 0.05 (Table 4). In the leave-one-country-out sensitivity analysis the two intergenic SNPs, rs79183898 and rs736596 were no longer significant at P < 10−4 when studies from the USA were excluded from the analysis and the OR estimates were substantially attenuated (Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4).

Table 4.

List of potential novel SNP modifiers associated in the case-only analysis for BRCA2 mutation carriers.

| Location | SNP namea | Chrb | Positionc | Nearest gene | Localisation | Estimated effect allele | Referent allele | r² d | Frequencye | ORf | Pg | HRCIMBAh | PCIMBAi | ORBCACj | PBCACk | PHETl | Target genem |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2p14 | rs12470785 | 2 | 67634003 | ETAA1 | Intron | G | A | 0.98 | 0.30 | 0.84 | 2.83e−11 | 0.89 | 1.69e−05 | 0.98 | 0.03 | 2.18e−07 | Level 2 |

| 13q13.1 | rs79183898 | 13 | 32221794 | B3GALTL - RXFP2 | Intergenic | A | T | 0.84 | 0.07 | 1.33 | 2.88e−10 | 1.04 | 3.55e−01 | 1.01 | 0.54 | 1.12e−08 | – |

| 13q13.1 | rs736596 | 13 | 33776506 | STARD13 | Intron | T | G | 0.66 | 0.09 | 1.37 | 3.44e−12 | 0.94 | 2.54e−01 | 0.98 | 0.45 | 4.99e−11 | Level 1 |

| 13q13.2 | rs4943263 | 13 | 35376357 | RP11-266E6.3 - RP11-307O13.1 | Intergenic | T | C | 0.99 | 0.27 | 1.17 | 8.33e−11 | 1.01 | 9.83e−01 | 1.00 | 0.47 | 6.94e−03 | Level 2 |

N = 62,822 breast cancer cases (57,725 BCAC cases and 5,097 BRCA2 mutation carrier cases).

aThe most significant SNP of each region after allowing for multiple testing, α* = 10−8

bChromosome.

cBuild 37 position.

dImputation accuracy.

eFrequency of the allele for which effect is estimated in BCAC cases (OncoArray dataset).

fPer allele odds ratio estimated in the case-only analysis. OR values were computed from a two sided logistic regression using a 1 df lrtest adjusted for age at BC diagnosis, country and the first four principal components.

gp-value in the case-only analysis.

hPer allele hazard ratio estimated in CIMBA cohort analysis.

ip-value found in CIMBA cohort analysis.

jPer allele odds-ratio estimated in BCAC (Michailidou et al.)35.

kp-value in BCAC (Michailidou et al. 2017). For SNPs with PBCAC > 10−8, significance was attained in merging data of Oncoarray, iCOGS and 11 different breast cancer GWAS in Michailidou et al.35.

lp-value of the heterogeneity test by country.

mINQUISIT score level: 1 = most functional evidence supporting potential link between CCVs and target gene.

In silico analyses on credible causal variants (CCV)

In order to determine the likely target genes of each region of the eight novel mutation carriers’ BC risk-associated SNPs, we first defined credible set of SNPs candidates to be causal (credible causal variants [CCVs]) (see “Methods”).

Sets of CCVs were sought for the two regions found in the previous step-wise analyses to be associated with risk in BRCA1 mutation carriers. In the region located at 11p11.2, only one signal composed of 74 CCVs was found (Table 5). All these 74 CCVs were imputed with a r2 higher than 0.92 (Supplementary Data 6). In the region located in 17q21.2, we found nine signals which contained from one to 13 CCVs (Table 5). Two of these CCVs were genotyped and the others had an r2 between 0.50 and 0.98 (Supplementary Data 6).

Table 5.

List of most significant SNPs in the CCV analysis for BRCA1 mutation carriers.

| Fine mapping regiona | Signalb | #CCVc | Location | SNP named | Chre | Positionf | Nearest gene | Localisation | Estimated effect allele | Referent Allele | Frequency g | r² h | Pi | ORj | PERk | ORl | PCIMBAm | HRCIMBAn |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| chr11:46773616-47773616 | 1 | 74 | 11p11.2 | rs60882887 | 11 | 47475675 | RAPSN, CELF1 | Intergenic | A | G | 0.14 | 0.95 | 2.20e−10 | 0.82 | 3.20e−06 | 0.82 | 7.00e−01 | 0.99 |

| chr17:39141815-40141815 | 1 | 2 | 17q21.2 | rs5820435 | 17 | 39961558 | LEPREL4 | Intronic | A | C | 0.45 | 0.51 | 1.10e−11 | 0.82 | 2.80e−05 | 0.85 | 9.10e−01 | 1.00 |

| 2 | 2 | 17q21.2 | rs7222250 | 17 | 39938469 | JUP | Intronic | C | T | 0.44 | 0.66 | 5.50e−14 | 1.23 | 3.90e−07 | 1.20 | 8.70e−01 | 1.00 | |

| 3 | 6 | 17q21.2 | rs9901834 | 17 | 39926811 | JUP | Intronic | A | G | 0.10 | 0.55 | 7.20e−10 | 0.72 | 3.90e−06 | 0.72 | 7.40e−01 | 1.02 | |

| 4 | 3 | 17q21.2 | rs58117746 | 17 | 39305775 | KRTAP4-5 | Intronic | TGGCAGCAGCTGGGGC | T | 0.39 | 0.60 | 5.50e−09 | 1.17 | 4.60e−04 | 1.13 | 2.20e−02 | 1.06 | |

| 5 | 13 | 17q21.2 | rs2239711 | 17 | 39633317 | KRT35 | Intronic | A | G | 0.29 | 0.93 | 4.90e−11 | 0.85 | 2.90e−04 | 0.88 | 5.00e−01 | 0.98 | |

| 6 | 4 | 17q21.2 | rs10708222 | 17 | 40137437 | DNAJC7 | Intronic | T | TA | 0.17 | 0.60 | 8.40e−07 | 1.18 | 6.10e−04 | 1.17 | 2.28e−01 | 0.95 | |

| 7 | 4 | 17q21.2 | rs41283425 | 17 | 39925713 | JUP | Intronic | T | C | 0.06 | 0.54 | 4.30e−07 | 0.73 | 1.30e−05 | 0.69 | 4.82e−01 | 0.95 | |

| 8 | 15 | 17q21.2 | rs56291217 | 17 | 39858199 | JUP | Intronic | AT | A | 0.44 | 0.76 | 6.70e−08 | 0.88 | 1.20e−06 | 0.85 | 4.06e−01 | 1.03 | |

| 9 | 1 | 17q21.2 | rs111637825 | 17 | 40134782 | DNAJC7 | Intronic | A | G | 0.06 | 0.89 | 3.60e−07 | 0.74 | 3.50e−04 | 0.75 | 4.47e−01 | 0.96 |

N = 67,469 breast cancer cases (60,212 BCAC cases and 7,257 BRCA1 mutation carrier cases).

aSignificant region in the main analysis used to look for credible causal variants (CCV).

bSignal number (the first one corresponds to the CCV set without any adjustment and the following are those with adjustment on each most significant SNP of the previous signals).

cNumber of credible causal variants at each signal (SNP with p-value at 2 order of magnitude of the most significant one).

dThe most significant SNP after adjustment on the most significant SNPs of the previous signals (except for these of the signal 1).

eChromosome.

fBuild 37 position.

gFrequency of the allele for which effect is estimated in BCAC cases (OncoArray dataset).

hImputation accuracy.

ip-value in the case-only analysis after adjustment on the most significant SNPs of the previous signals (except for these of the signal 1).

jPer allele odds ratio estimated in the case-only analysis. OR values were computed from a two sided logistic regression using a 1df lrtest adjusted for age at BC diagnosis, country, the first four principal components and the most significant SNPs of the previous signals (except for these of the signal 1).

kP-value in the case-only analysis restricted to ER-negative BCAC cases and after adjustment with the most significant SNP of the previous signals (except for these of the signal 1).

lPer allele odds ratio estimated in the case-only analysis restricted to ER-negative BCAC cases and after adjustment with the most significant SNP of the previous signals (except for these of the signal 1).

mp-value found in CIMBA cohort analysis.

n Per allele hazard ratio estimated in CIMBA cohort analysis.

We used INQUISIT35,54 to prioritize target genes by intersecting each CCV with publicly available annotation data from breast cells and tissues (see “Methods”). The results for BRCA1 mutation carriers are summarized in Supplementary Data 7. For BRCA1 mutation carriers, we predicted 38 unique target genes for six of the 10 independent signals. Seven target genes in two regions (MTCH2, MADD, PSMC3, RP11-750H9.5, SLC39A13, SPI1, and EIF1) were predicted with high confidence (designated Level 1, scoring range between Level 1 [highest confidence] to Level 3 [lowest confidence]). All seven Level 1 genes were predicted to be distally regulated by CCVs.

Similarly, sets of CCVs were sought from the four regions found in the previous step-wise analyses to be associated with risk in BRCA2 mutation carriers. A total of 17 signals were found. One signal composed of 78 CCVs was found in the region located at 2p14 (Table 6). One CCV was genotyped and the others were imputed with r2 between 0.95 and 0.99 (Supplementary Data 8). Twelve signals were found from the two regions previously found in 13q13.1 which contained from one to 46 CCVs. The analysis in the region of rs79183898 in 13q13.1 found three signals out of the 12, which are located in 13q12.3 (with top SNPs: rs71434801, rs77197167, rs114300732). Finally, four signals in the previously identified region located in 13q13.2 containing from three to 40 CCVs were found. Among all CCVs, 11 are genotyped and the imputed ones have an r2 higher than 0.58 (Table 6 and Supplementary Data 8).

Table 6.

List of most significant SNPs in the CCV analysis for BRCA2 mutation carriers.

| Fine mapping regiona | Signalb | #CCVc | Location | SNP named | Chre | Positionf | Nearest gene | Localisation | Estimated effect allele | Referent allele | Frequency g | r² h | Pi | ORj | PCIMBAk | HRCIMBAl |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| chr2:67099466-68099466 | 1 | 78 | 2p14 | rs12470785 | 2 | 67634003 | ETAA1 | Intronic | G | A | 0.30 | 0.98 | 4.20e−11 | 0.85 | 7.70e−05 | 0.89 |

| chr13:31015494-32515494 | 1 | 8 | 13q13.1 | rs79183898 | 13 | 32221794 | B3GALTL, RXFP2 | Intergenic | A | T | 0.07 | 0.84 | 1.10e−10 | 1.33 | 3.60e−01 | 1.04 |

| 2 | 23 | 13q12.3 | rs71434801 | 13 | 31249461 | USPL1, ALOX5AP | Intergenic | G | C | 0.13 | 0.76 | 3.40e−08 | 1.22 | 8.40e−01 | 0.99 | |

| 3 | 35 | 13q12.3 | rs77197167 | 13 | 31693513 | WDR95P, HSPH1 | Intergenic | C | T | 0.09 | 0.76 | 1.80e−07 | 1.25 | 4.00e−01 | 1.04 | |

| 4 | 7 | 13q12.3 | rs114300732 | 13 | 31662987 | WDR95P | Intronic | T | C | 0.07 | 0.90 | 1.70e−08 | 0.67 | 8.80e−02 | 1.09 | |

| 5 | 12 | 13q13.1 | 13:32231513:CAA:C | 13 | 32231513 | B3GALTL, RXFP2 | Intergenic | CAA | C | 0.25 | 0.92 | 8.40e−07 | 0.86 | 1.70e−02 | 1.08 | |

| 6 | 6 | 13q13.1 | rs1623189 | 13 | 32232683 | B3GALTL, RXFP2 | Intergenic | G | T | 0.26 | 0.95 | 1.30e−31 | 2.70 | 6.60e−01 | 1.01 | |

| chr13:33395975-34395975 | 1 | 1 | 13q13.1 | rs736596 | 13 | 33776506 | STARD13 | Intronic | T | G | 0.09 | 0.66 | 1.20e−12 | 1.37 | 2.50e−01 | 0.95 |

| 2 | 1 | 13q13.1 | rs77889880 | 13 | 33776161 | STARD13 | Intronic | T | A | 0.10 | 0.80 | 3.00e−21 | 0.51 | 1.90e−02 | 1.12 | |

| 3 | 1 | 13q13.1 | rs67776313 | 13 | 33934343 | RP11-141M1.3 | Intronic | A | AT | 0.33 | 0.70 | 7.70e−12 | 0.81 | 4.60e−01 | 0.98 | |

| 4 | 42 | 13q13.1 | rs71196514 | 13 | 33800572 | STARD13 | Intronic | C | CT | 0.38 | 0.67 | 1.00e−07 | 0.86 | 6.20e−01 | 1.01 | |

| 5 | 52 | 13q13.1 | rs2555605 | 13 | 33833810 | STARD13 | Intronic | C | T | 0.36 | 1.00 | 4.60e−08 | 0.87 | 2.00e−01 | 1.03 | |

| 6 | 46 | 13q13.1 | rs74796280 | 13 | 33700860 | STARD13 | Intronic | C | A | 0.06 | 0.96 | 4.70e−07 | 0.77 | 3.10e−02 | 0.89 | |

| chr13:34793902-35793902 | 1 | 18 | 13q13.2 | rs4943263 | 13 | 35376357 | RP11-266E6.3, RP11-307O13.1 | intergenic | T | C | 0.27 | 0.99 | 6.30e−11 | 1.18 | 9.80e−01 | 1.00 |

| 2 | 3 | 13q13.2 | rs2202781 | 13 | 35292372 | RP11-266E6.3, RP11-307O13.1 | Intergenic | G | A | 0.24 | 0.93 | 3.10e−11 | 1.20 | 6.00e−01 | 0.98 | |

| 3 | 40 | 13q13.2 | rs55675572 | 13 | 35315594 | RP11-266E6.3, RP11-307O13.1 | intergenic | A | T | 0.40 | 0.77 | 5.60e−08 | 0.86 | 7.50e−01 | 0.99 | |

| 4 | 21 | 13q13.2 | rs17755120 | 13 | 35270340 | RP11-266E6.3, RP11-307O13.1 | intergenic | T | A | 0.20 | 0.98 | 6.30e−07 | 0.76 | 4.80e−01 | 0.98 |

N = 62,822 breast cancer cases (57,725 BCAC cases and 5,097 BRCA2 mutation carrier cases).

aSignificant region in the main analysis used to look for credible causal variants (CCV).

bSignal number (the first one corresponds to the CCV set without any adjustment and the following are those with adjustment on each most significant SNP of the previous signals).

cNumber of credible causal variants at each signal (SNP with p-value at 2 order of magnitude of the most significant one).

dThe most significant SNP after adjustment on the most significant SNPs of the previous signals (except for these of the signal 1).

eChromosome.

fBuild 37 position.

gFrequency of the allele for which effect is estimated in BCAC cases (OncoArray dataset).

hImputation accuracy.

ip-value in the case-only analysis after adjustment on the most significant SNPs of the previous signals (except for these of the signal 1).

jPer allele odds ratio estimated in the case-only analysis. OR values were computed from a two sided logistic regression using a 1df lrtest adjusted for age at BC diagnosis, country, the first four principal components and the most significant SNPs of the previous signals (except for these of the signal 1).

kp-value found in CIMBA cohort analysis.

lPer allele hazard ratio estimated in CIMBA cohort analysis.

For BRCA2 mutation carriers, we predicted 24 unique target genes for 10 of the 17 independent signals, including one high confidence target gene, STARD13 at chr13:33395975-34395975. STARD13 was also predicted to be targeted by three independent signals. All results are presented in Supplementary Data 9.

Discussion

To identify novel genetic modifiers of BC risk for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers and to further clarify the effects of known BC susceptibility SNPs on BC risk for carriers, a novel case-only analysis strategy was used based on GWAS data from unselected BC cases in BCAC and mutation carriers with BC from CIMBA. This strategy provides increased statistical power for detecting new associations and for clarifying the risk associations of known BC susceptibility SNPs in mutation carriers55.

Of the 179 known BC susceptibility SNPs identified through GWAS in the general population5–35, only 10 showed evidence of interaction with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carrier status after taking the tumour ER-status into account. None of these 10 SNPs was among the fifty SNPs previously shown to be associated with BC for mutation carriers5,6,15,18,20,39–48. However, 82% of all 179 known susceptibility SNPs showed a predicted OR point estimate for mutation carriers closer to 1 than that estimated in the general population. The effect sizes in the general population may be somewhat exaggerated as the BCAC dataset used here contributed to the discovery of most of the loci, although this effect is likely to be small as most loci are highly significant and the effects have been replicated in independent datasets7. Taken together, these results suggest that, while most SNPs associated with risk in the general population are associated with risk for mutation carriers, the average effect sizes for mutation carriers are smaller. These findings are in line with previous results by Kuchenbaecker et al.49 and suggest that a PRS built using data from the general population will have a smaller effect size for BRCA1/2 mutation carriers.

For 10 SNPs, an interaction was observed with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carrier status, suggesting that these SNPs have different effect sizes in BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers compared to the general population (seven for BRCA1 mutation carriers and three for BRCA2 mutation carriers). Specifically, for seven SNPs the confidence intervals were consistent with no effect on BC risk for mutation carriers, one SNP was associated with a larger OR for mutation carriers compared to the general population and two were associated in the opposite direction to that observed in the general population. However, distinguishing between a smaller effect size for mutation carriers compared to the general population OR estimates and no association for mutation carriers is very challenging since, even with the large sample size here, it is not possible to estimate precisely the effect sizes for individual variants. Larger sample sizes will be required for this purpose. Determining the precise effects of the SNPs in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers will provide insights for understanding the biological basis of cancer development associated with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations.

We also identified eight novel conditionally independent common SNPs associated with BC risk (four for BRCA1 mutation carriers, four for BRCA2 mutation carriers). These have not been reported in previous association studies5,6,15,18,20,39–47. The case-only OR estimates for these SNPs varied from 0.85 to 1.37 for BRCA2 mutation carriers and from 0.78 to 1.22 for BRCA1 mutation carriers. For five of these SNPs the estimated ORs from the case-only analysis results were in the same direction as the estimated HRs from previously reported GWAS using cohort analyses restricted in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers in CIMBA56. Two of these five SNPs also demonstrated some evidence of association in mutation carriers (p = 2.2 × 10−2 for rs58117746 for BRCA1 mutation carriers; and p = 7.7 × 10−5 for rs12470785 in ETAA1 for BRCA2 mutation carriers; Tables 3 and 4). For the remaining three variants, rs5820435 and rs11079012 at 17q21.2 and rs736596 at 13q13.1, the associations in BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers in the CIMBA data were not consistent with the observed interactions and might be artefactual. One possibility is that the associations with SNPs on 17q and 13q in BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers respectively, reflect confounding due to linkage disequilibrium (LD) with specific mutations. Although we excluded variants with evidence of association in the control only analyses, it is possible that residual confounding due to specific mutations was still present.

Seven genes at a locus at 11p11.2 marked by rs60882887, were predicted with high confidence as targets, including MADD, SP11 and EIF1 which have previously been reported to be associated with BC biology57–59. However, no likely target genes were predicted at the 17q21.2 region. The lack of target gene predictions may be due to reliance on breast cell line data which does not represent the in vivo tissue of interest or due to the fact that the target transcripts are not annotated.

Only one gene, STARD13, was predicted as a potential target of SNPs at 13q13.1. This tumour suppressor gene has been previously implicated in metastasis, cell proliferation and development of BC60. However, rs736596, localized at 13q13.1, showed no association in CIMBA analyses and the association observed in our case-only analysis showed heterogeneity by country.

At the 2p14 locus, INQUISIT-predicted target genes included ETAA1 with lower confidence. The OR estimates obtained in the case-only analysis for the SNPs located in this gene were consistent with the HR estimated in previously reported CIMBA analyses56. Moreover, around one hundred correlated SNPs, were associated with BRCA2 mutation carrier status at p < 10−8, including the genotyped SNP chr2_67654113_C_T.

The validity of the case-only analysis as evidence of interaction relies on the assumption of independence between the mutation status and the SNPs under investigation61. Therefore, based on the control-only analyses, we excluded ~2,000 SNPs which were associated with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carrier status and also showed an association with risk in the case-only analyses (Supplementary Fig. 5). While most of these associations are probably spurious, due to (intra- or inter-chromosomal) LD with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations, it is possible that some may reflect true associations and that the higher frequency in unaffected BRCA1/2 may be because they are relatives of BC cases. These associations may warrant further evaluation using other study designs. A recent publication using data from the Framingham Heart Study suggested that interchromosomal LD can be caused by bio-genetic mechanisms possibly associated with favourable or unfavourable epistatic evolution62. SNPs for which no association with mutation carrier status was found at the significance level of 10−8 were assumed to be independent of the mutation status. However, this does not necessarily rule out residual LD between the novel SNPs on chromosomes 13 and 17 and BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. Therefore, the OR estimates for these SNPs might be biased and may further explain the lack of evidence of association in the CIMBA only analyses.

Our findings highlight the importance of imputation in GWAS. The imputed genome-wide genotype data used in the main case-only association analyses were based on carrying out the imputation separately for the BC cases from BCAC and CIMBA. We found that 28 out of the 33 regions associated with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carrier status were no longer associated with risk after re-imputing all samples together. By re-imputing all the data together we ensured that the associations observed for the remaining regions are robust to potential differences in the imputation accuracy between the BCAC and CIMBA samples.

Under our analytical strategy, only the regions for which evidence of associated with BC risk was observed were re-imputed using all BCAC and CIMBA samples combined. This re-imputation was not done at genome-wide level due to computational constraints and this may have led to false-negative associations being excluded for further evaluation as potential novel modifiers. Future analyses should aim to analyse the genome-wide associations after the genome-wide re-imputation across the combined BCAC and CIMBA dataset. However, our approach using joint one-step imputation should have ensured that associations we report (all of which are common SNPs with imputation scores > 0.5) are not driven by inaccuracies in imputation.

Due to the recruitment of participants in CIMBA studies primarily through genetic counselling, the mean age at diagnosis of mutation carriers was 16 years younger than the BC cases participating in BCAC. Although all analyses were adjusted for age, the observed associations might be related to the ageing process instead of interactions with mutation carrier status. Another source of bias could be related to the fact that there are 1.5 times more prevalent cases among CIMBA (68.1%) than BCAC (42.3%) with a delay between diagnosis and study recruitment of 6.83 years and 2.07 years respectively. An observed association might be due to a differential survival between CIMBA and BCAC cases. However, none of the identified SNPs has been found to be associated with BC survival63.

The majority (92.5%) of cases and controls in BCAC were not tested for BRCA1/2 mutations at the time of enrolment, potentially leading to some attenuation in the interaction OR (as some BCAC cases will be carriers). However, most BCAC studies were population-based case-control studies and the proportion of cases and controls that carry pathogenic BRCA1/2 mutations will be small (<5%), hence any attenuation is likely to be negligible.

Despite heterogeneity in the interaction ORs by country for some SNPs, results were generally robust to the exclusion of each country sequentially except, for two SNPs (rs79183898 and rs736596) found associated with BRCA2 mutation carrier status; for these, the association seemed to be driven by data from the USA. For the other SNPs, the observed heterogeneity may be due to random error, given the relatively small sample sizes of each country. However, if these differences are real, future PRS for BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers should consider the country-specific differences.

This is the first analysis of genetic modifiers of BC risk that investigated the differences in the association of common genetic variants with BC risk in the general population and in women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. The inclusion of unselected BC cases resulted in increased sample size and hence a gain in statistical power for identifying novel SNPs. These represent the largest currently available datasets, but it is important to replicate these observations in independent samples. This should be possible through the ongoing CONFLUENCE (https://dceg.cancer.gov/research/cancer-types/breast-cancer/confluence-project) large-scale genotyping experiment. More detailed fine mapping and functional analysis will be required to elucidate the role of the novel variants identified in BC development for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Our findings should contribute to the improved performance of BC PRS for absolute risk prediction for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers, which will help inform decisions on the best timing for risk-reducing surgery, risk reduction medication, or the start of surveillance.

Methods

Study sample

We used data from two international consortia, BCAC64 and CIMBA56. BCAC included data from 108 studies of BC from 33 countries in North America, Europe and Australia, the majority (88%) of which were case-control studies. The majority of BCAC cases/controls were not tested for BRCA1/2 mutations at the time of enrolment. However, most studies were population-based, hence the proportion of cases and controls that carry pathogenic BRCA1/2 mutations will be small. CIMBA participants were women with pathogenic mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2. All participants were at least 18 years old. The majority of mutation carriers were recruited through cancer genetics clinics and enroled into national or regional studies. Data were available on 30,500 BRCA1 mutation carriers and 20,500 BRCA2 mutation carriers from 77 studies in 32 countries. A total of 188,320 BC cases and 161,669 controls were available from both consortia. All studies provided information on disease status, age at diagnosis or at interview. Oestrogen receptor status was available for 72% of BCAC cases and 71% of CIMBA cases. All subjects provided written informed consent and participated in studies with protocols approved by ethics committees at each participating institution.

Sample selection

BCAC cases were women diagnosed with BC7. To define disease status in CIMBA participants, women were censored at the first of the following events: age at BC diagnosis, age at ovarian cancer diagnosis, other cancer, bilateral prophylactic mastectomy or age at study recruitment. Subjects censored at a BC diagnosis were considered as cases.

A control-only analysis was carried out to test the independence between the SNPs and the BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carrier status. In BCAC, controls were defined as individuals unaffected by BC at study recruitment35. In CIMBA, participants were considered as controls if they were unaffected at recruitment.

Only women of European ancestry were included. To minimise the chance of observing spurious associations due to differences in the distribution of BC cases in the population by tumour characteristics (defined as unselected BC cases), 3,478 BCAC cases from four studies were excluded because they were included in clinical trials based on breast tumour characteristics as HER-2 receptor status (see Supplementary Table 2). Because all the analyses were adjusted for country, to ensure that the number of subjects in each country stratum was large enough, we excluded the CIMBA data from any country for which there were less than ten BC cases with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. Consequently, data from Poland and Russia were excluded from the BRCA2 analyses (Supplementary Table 3). Finally, duplicate subjects between BCAC and CIMBA were excluded from the BCAC data (114 and 80 subjects from the BRCA1 and BRCA2 case-only analyses, respectively; eight subjects from control-only analyses).

A total of 60,212 BCAC cases and 7,257 BRCA1 mutation carrier cases were available for the BRCA1 case-only analyses and 57,725 BCAC cases and 5097 BRCA2 mutation carrier cases were available for the BRCA2 case-only analyses (Fig. 1). A total of 45,881 BCAC controls and 5,750 BRCA1 mutation carrier controls were available for the BRCA1 control-only analyses and 43,549 BCAC controls and 4,456 BRCA2 mutation carrier controls for the BRCA2 control-only analyses (Fig. 2).

Genotype data

All the study samples were genotyped using the OncoArray Illumina beadchip65. The array includes a backbone of ~260,000 SNPs that provide genome-wide coverage of most common variants, together with markers of interest for breast and other cancers identified through GWAS, fine-mapping of known susceptibility regions, and other approaches65.

A standard genotype quality control process was followed for both the BCAC and CIMBA samples which have been described in detail elsewhere35,48. Briefly, this involved excluding SNPs located on chromosome Y; SNPs with call rates <95%; SNPs with MAF < 0.05 and call rate <98%; monomorphic SNPs; and SNPs for which evidence of departure from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium was observed (P < 10−7 based on a country-stratified test).

Genotypes for ~21 million SNPs were imputed for all subjects using the 1000 Genomes Phase III data (released October 2014) as reference panel, as described previously66. Briefly, the number of reference haplotypes used as templates when imputing missing genotypes was fixed to 800 (-k_hap = 800). A two-stage imputation approach was used: phasing with SHAPEIT67,68 and imputation with IMPUTE269 using 5 Mb non-overlapping intervals. Genotypes were imputed for all SNPs that were found polymorphic (MAF > 0.1%) in either European or Asian populations.

The genome-wide imputation process described above was carried out separately for the BCAC and CIMBA samples. However, this may potentially lead to spurious associations if there are differences in the quality of the imputation (measured using the imputation accuracy r² metric70) for a given SNP between the two datasets. To address this, a stringent approach was employed which involved including only SNPs for which the difference in r² between the BCAC and CIMBA SNP imputations (Δr²) was minimal relative to their r² values. SNPs with r² > 0.9 in both BCAC and CIMBA were kept in the analyses only if Δr² < 0.05; SNPs with 0.8 < r² ≤ 0.9 in both BCAC and CIMBA were kept if Δr² < 0.02 and, SNPs with 0.5 < r² ≤ 0.8 in both BCAC and CIMBA were kept if Δr² < 0.01. All SNPs with r² < 0.5 in either CIMBA or BCAC were excluded. Only SNPs with a MAF > 0.01 in BCAC cases were included.

Consequently, 9,072,535 SNPs were included in the BRCA1 analyses (402,336 genotyped and 8,670,199 imputed SNPs) and 9,047,403 SNPs in the BRCA2 analyses (402,397 genotyped and 8,645,006 imputed SNPs).

Case-only and control-only analyses

The comparison of SNP frequency between CIMBA cases and BCAC cases (case-only analyses), or between unaffected CIMBA subjects and BCAC controls (control-only analyses), was performed using logistic regression adjusted for age at BC diagnosis in the case-only analyses and for age at interview for BCAC controls or at censure for CIMBA unaffected subjects in the control-only analyses, as well as for country and principal components (PCs) to account for population structure. Separate analyses were carried out for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. To define the number of PC for inclusion in the models, the principal component analysis was carried out using 35,858 uncorrelated genotyped SNPs on the OncoArray and purpose-written software (http://ccge.medschl.cam.ac.uk/software/pccalc/). The inflation statistic was calculated and converted to an equivalent statistic for a study of 1,000 subjects for each outcome (λ1,000) by adjusting for effective study size:

where n and m are the numbers of BCAC and CIMBA subjects respectively. The models were adjusted with the first four PCs (λ1,000 with and without PCs in the model = 1.03 and 1.21, respectively) since additional PCs did not result in further reduction in the inflation of the test statistics.

Strategy for determining significant associations

The analytical process is summarised in Figs. 3 and 4. A fundamental assumption when using a case-only design in this context is that the SNPs and mutation carrier status are independent61. To confirm independence, SNPs likely to be in linkage disequilibrium (LD) with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations, i.e., those located in or within 500 kb of either gene, were excluded. However, LD also exists between variants at long-distance on the same chromosome or even on a different chromosome (interchromosomal LD)62,71. Therefore, control-only analyses were performed to further exclude SNPs associated with mutation carrier status in unaffected women72, using a stringent statistical significance level of 10−8).

After excluding SNPs in LD or in interchromosomal LD with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations, case-only analyses were performed to assess the association between SNPs and BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carrier status. We considered two categories of SNPs depending on whether they had been previously found to be associated with BC in published BCAC studies35,48. For known BC susceptibility SNPs (Fig. 3) we used a significance threshold of 2.7 × 10−4 (applying Bonferroni correction to 179 tests) and for potential novel SNP modifier (Fig. 4) a stringent significance threshold of 10−8 was used.

Because BRCA1mutation-associated tumours are more often ER-negative than those in the general population73, a subsequent case-only analysis was performed restricting the BCAC cases to those with ER-negative disease. We used this strategy for two reasons. First, we wished to exclude associations driven by differences in the tumour ER-status distributions between BRCA1 carriers and BCAC cases. Therefore, in the BRCA1 analysis, SNPs were considered to be associated with mutation carrier status only if they were also associated in the ER-negative case-only analysis at a prior defined significance threshold of 10−7 for novel SNP modifiers (Fig. 4) and of 0.05 for the established BC susceptibility SNPs after a pre-selection at P < 2.7 × 10−4 in the BRCA1 overall case-only analysis (Fig. 3). The second reason we applied this strategy was to identify novel SNP modifiers specific to BRCA1/ER-negative tumours that had not been detected in the overall analysis; for this we applied a significance threshold of 10−8.

To confirm that potentially novel associations in the case-only analysis were not driven by differences in the imputation accuracy between the CIMBA and BCAC data, each of the regions defined as ±500 kb around the associated SNP, were re-imputed for the combined CIMBA and BCAC samples. The more accurate one-stage imputation was carried out, using IMPUTE2 without pre-phasing. Associations with all the SNPs in the re-imputed regions were then re-evaluated using the control-only and case-only analytical approaches described above. Finally, we used a step-wise regression analysis using a significance threshold of 10−8 in order to determine whether associations with SNPs in the same region are independent and to define the conditionally independent SNPs (top SNPs).

Among the 179 established BC susceptibility SNPs, 107 were genotyped and 71 were imputed. As previously, although none of these 71 SNPs were excluded based on their Δr², to exclude potentially spurious associations, regions around these 71 SNPs were re-imputed using the one-stage imputation applied to BCAC and CIMBA data combined, and before performing the control-only and case-only analyses.

Determining the magnitude of association

For the potentially novel SNP modifiers the risk ratio of BC applicable to mutation carriers was assumed to be equal to the OR estimate from the case-only analysis (with the hypothesis that their relative risk equals 1 in the general population, given that none of them was found to be associated with BC in BCAC)55.

For the known BC susceptibility SNPs, a significant association in the case-only analysis implies that the magnitude of association is different for BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers than for the general population. Therefore, the risk ratio of BC for mutation carriers was computed as the product of OR × ORBCAC where OR was obtained from the case-only analysis, and ORBCAC was the odds ratio of association obtained from either Michailidou et al.35 for the SNPs associated with overall BC risk and from Milne et al.48 for the SNPs associated with ER-negative BC.

For all associated SNPs in case-only analyses, heterogeneity by country was assessed using likelihood ratio tests that compared models with and without an SNP by country interaction term. When the heterogeneity test was significant at P < 0.05, a leave-one-out analysis was performed, by excluding each country in turn to assess the influence of a data from a specific country on the overall association.

Credible causal variants

For each novel region, we defined sets of credible causal variants (CCVs) to use in the prediction of the likely target genes. For this purpose, we defined a first set of CCVs including the top SNP of the region of interest and the SNPs with p-values of association within two orders of magnitude of the top SNP association. Then, we sequentially performed logistic regression analyses using all other SNPs in the region, adjusted for the top SNP. We defined a second set of CCVs which included the most significant SNP after adjusting for the top SNP and the SNPs with p-values within two orders of magnitude of the most significant SNP association. This was repeated (conditioning on the previously found most significant SNPs) to define additional sets of CCVs as long as at least one p-value remained <10−6.

eQTL analysis

Data from BC tumours and adjacent normal breast tissue were accessed from The Cancer Genome Atlas74 (TCGA). Germline SNP genotypes (Affymetrix 6.0 arrays) from individuals of European ancestry were processed and imputed to the 1000 Genomes reference panel (October 2014)35. Tumour tissue copy number was estimated from the Affymetrix 6.0 and called using the GISTIC2 algorithm75. Complete genotype, RNA-seq and copy number data were available for 679 genetically European patients (78 with adjacent normal tissue). Further, RNA-seq for normal breast tissue and imputed germline genotype data were available from 80 females from the GTEx Consortium76. Genes with a median expression level of 0 RPKM across samples were removed, and RPKM values of each gene were log2 transformed. Expression values of samples were quantile normalized. Genetic variants were evaluated for association with the expression of genes located within ±2 Mb of the lead variant at each risk region using linear regression models, adjusting for ESR1 expression. Tumour tissue was also adjusted for copy number variation77. eQTL analyses were performed using the MatrixEQTL program in R78.

INQUISIT analyses

Candidate target genes were evaluated by assessing each CCV’s potential impact on regulatory or coding features using a computational pipeline, INtegrated expression QUantitative trait and In SIlico prediction of GWAS Targets (INQUISIT)35,54. Briefly, genes were considered as potential targets of candidate causal variants through effects on: (1) distal gene regulation, (2) proximal regulation, or (3) a gene’s coding sequence. We intersected CCV positions with multiple sources of genomic information chromatin interaction analysis by paired-end tag sequencing (ChIA-PET79) in MCF7 cells and genome-wide chromosome conformation capture (Hi-C) in HMECs. We used breast cell line computational enhancer–promoter correlations (PreSTIGE80, IM-PET81, FANTOM582) breast cell super-enhancer83, breast tissue-specific expression variants (eQTL) from multiple independent studies (TCGA (normal breast and breast tumour) and GTEx breast—see eQTL methods), transcription factor and histone modification chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) from the ENCODE and Roadmap Epigenomics Projects together with the genomic features found to be significantly enriched for all known breast cancer CCVs54, gene expression RNA-seq from several breast cancer lines and normal samples (ENCODE) and topologically associated domain (TAD) boundaries from T47D cells (ENCODE84). To assess the impact of intragenic variants, we evaluated their potential to alter primary protein coding sequence and splicing using Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor85 using MaxEntScan and dbscSNV modules for splicing alterations based on ada and rf scores. Nonsense and missense changes were assessed with the REVEL ensemble algorithm, with CCVs displaying REVEL scores >0.5 deemed deleterious.

Each target gene prediction category (distal, promoter or coding) was scored according to different criteria. Genes predicted to be distally regulated targets of CCVs were awarded points based on physical links (for example ChIA-PET), computational prediction methods, or eQTL associations. All CCVs were considered as potentially involved in distal regulation. Intersection of a putative distal enhancer with genomic features found to be significantly enriched54 were further upweighted. Multiple independent interactions were awarded an additional point. CCVs in gene proximal regulatory regions were intersected with histone ChIP-Seq peaks characteristic of promoters and assigned to the overlapping transcription start sites (defined as −1.0 kb – +0.1 kb). Further points were awarded to such genes if there was evidence for eQTL association, while a lack of expression resulted in down-weighting as potential targets. Potential coding changes including missense, nonsense and predicted splicing alterations resulted in addition of one point to the encoded gene for each type of change, while lack of expression reduced the score. We added an additional point for predicted target genes that were also breast cancer drivers (278 genes35,54). For each category, scores potentially ranged from 0 to 8 (distal); 0 to 4 (promoter) or 0 to 3 (coding). We converted these scores into ‘confidence levels’: Level 1 (highest confidence) when distal score > 4, promoter score ≥3 or coding score >1; Level 2 when distal score ≤ 4 and ≥1, promoter score = 1 or = 2, coding score = 1; and Level 3 when distal score <1 and >0, promoter score <1 and >0, and coding <1 and >0. For genes with multiple scores (for example, predicted as targets from multiple independent risk signals or predicted to be impacted in several categories), we recorded the highest score.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements