Abstract

Background

The role of collagen type XVIII alpha 1 chain (COL18A1) in anti‐tuberculosis drug‐induced hepatotoxicity (ATDH) has not been reported. This study aimed to explore the association between of COL18A1 variants and ATDH susceptibility.

Methods

A total of 746 patients were enrolled in our study from December 2016 to April 2018, and all subjects in the study signed an informed consent form. The custom‐by‐design 2x48‐Plex SNPscanTM kit was used to genotype all selected 11 SNPs. Categorical variables were compared by chi‐square (χ2) or Fisher's exact test, while continuous variables were compared by Mann‐Whitney's U test. Plink was utilized to analyze allelic and genotypic frequencies, and genetic models. Multivariate logistic regression analyses were used to adjust potential factors. The odds ratios (ORs) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were also calculated.

Results

Among patients with successfully genotyping, there were 114 cases and 612 controls. The mutant A allele of rs12483377 conferred the decreased risk of ATDH (OR = 0.13, 95%CI: 0.02–0.98, P = 0.020), and this significance still existed after adjusting age and gender (P = 0.024). The mutant homozygote AA genotype of rs12483377 was associated with decreased total protein levels (P = 0.018).

Conclusion

Our study first revealed that the A allele of COL18A1 rs12483377 was associated with the decreased risk of ATDH in the Western Chinese Han population, providing new perspective for the molecular prediction, precise diagnosis, and individual treatment of ATDH.

Keywords: anti‐tuberculosis drug‐induced hepatotoxicity, COL18A1, genetic polymorphisms, susceptibility

Regarding the heavy burden of ATDH in Western China, we thus conducted a prospective study to explore the association between COL18A1 polymorphisms and the risk of ATDH in the Western Chinese Han population. In this work, we first demonstrated the relationship between COL18A1 rs12483377 and ATDH and put forward the possible function mechanisms, contributing to further understanding of the molecular pathogenesis of ATDH and promoting the development of molecular diagnostics.

1. INTRODUCTION

Anti‐tuberculosis drug‐induced hepatotoxicity (ATDH) is the most serious adverse drug reaction during the course of tuberculosis (TB) therapy. 1 ATDH is defined as the inflammation of hepatocytes caused by idiosyncratic reaction to the anti‐TB drugs. 2 The following 4 mechanisms are considered as the pathogenesis of ATDH: I) the enzymes and pathways about drug metabolizing, such as glutathione S‐transferase (GST) and N‐acetyl transferase 2 (NAT2); II) the accumulation of bile acids, lipids, and heme metabolites; III) the toxicity mediated by immune system; IV) the increasing oxidant stress. 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 It is noted that ATDH can be curable in the early stage, 7 although this disease has high mortality (22.7%) and morbidity (28%) 8 , 9 , 10 and adverse effects on the anti‐TB treatment efficiency. 11 However, the ambiguous diagnostic criteria and atypical symptoms interfere with early prediction and diagnosis of ATDH. Even worse, the delayed diagnosis of ATDH aggravates the severity of the disease and increases the disease burden. 12 , 13 Clearly, it is urgent to explore new biomarkers for diagnosis of ATDH. With the development of molecular detection methods, genetic factors are gradually well‐recognized and considered as the crucial elements in the pathogenesis, prediction, diagnosis and treatment of many diseases. 14 , 15 , 16 Nowadays, a growing body of evidence proves that single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), such as pregnane X receptor (PXR) rs7643645 17 , 18 and phase I cytochrome P450 enzyme (CYP2E1), 8 play important roles in the prediction, diagnosis, and treatment of ATDH. However, these SNPs are not applied in clinic due to limited predictive capacity or reliability. Thus, there is a promising future for exploring the association between more meaningful SNPs and ATDH to achieve precise prediction and treatment of ATDH.

Collagen type XVIII alpha 1 chain (COL18A1) is located on chromosome 21q22.3, encoding the alpha XVIII collagen. The product of alpha XVIII collagen, endostatin (EST), is mainly present in the liver sinusoidal and basement. 19 The close relationship between EST and liver diseases has been reported in many studies. 20 , 21 , 22 Many researchers find that EST can initiate the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase (NOX) redox signaling cascade. 20 , 23 , 24 While the activation of NOX can generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) to increase oxidant stress which is one of the pathogenesis of ATDH as described before, and thus leads to the exacerbation of liver injury. 4 , 23 , 25 Moreover, Wnt/β‐catenin signaling directs multiple liver cell processes and it is the essential signal for protecting hepatocyte from oxidative stress‐induced cell deaths. 26 Moreover, it is has been published that EST can inhibit Wnt/β‐catenin signaling through promoting the degradation of β‐catenin. 27 Hence, we speculated that COL18A1 plays a role in ATDH by involving in the Wnt/β‐catenin signaling, oxidative stress, and other various ways. 28 , 29 , 30

It is a pity that few studies have paid attention to explore the correlation between COL18A1 and ATDH. Regarding the high burden of ATDH in Western China, 31 we conducted this prospective study to evaluate the association between COL18A1 polymorphisms and the risk of ATDH in the Western Chinese Han population for the first time. We aimed to explore novel targets for the pathogenesis and personal treatment of ATDH patients.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study population

In this prospective study, 746 subjects were recruited from the West China Hospital of Sichuan University from December 2016 to April 2018 consecutively. All enrolled patients in the study were unrelated Han ethnicity.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of West China Hospital of Sichuan University (Reference No. 198; 2014), and written informed consents were obtained from all patients.

2.2. Inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria

All recruited patients must meet the following criteria: I) Patients were newly diagnosed as TB patients by 2 experienced respiratory physicians based on National Institute for Heath and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines [NG33]: Tuberculosis 32 ; II) patients should have normal liver function before the anti‐TB treatment. If patients who had (a) immunodeficiency diseases such as HIV; (b) liver dysfunction such as hepatitis B or C infection, fatty liver; (c) received other hepatotoxic drugs; (d) renal dysfunction; (e) other lung or liver disorders such as lung cancer and cirrhosis would be excluded.

Included subjects would be treated with the WHO standard 6‐months anti‐TB treatment regimens, consisting of isoniazid (INH), rifampicin (RIF), pyrazinamide (PZA), and ethambutol (EMB). Besides, enrolled subjects did not take any other drugs which would cause liver damage.

During the anti‐TB therapy, patients would be tested liver function regularly to monitor their liver function and the baseline levels of laboratory indicators before anti‐TB treatment were tested. ATDH was defined as follows 33 : (a) an increase in alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels more than 2 times upper limit of normal (ULN); (b) an increase in ALT 2 times upper ULN combined a rise in aspartate aminotransferase (AST) or total bilirubin (TB) levels.

2.3. SNP selection

The genetic data of COL18A1 were obtained from 1000 Genomes database. All SNPs should meet the criteria that the minor allele frequency (MAF) was greater than 0.02. The tag SNPs selected by Haploview (version 4.1), the locations of SNPs and relevant reports 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 also needed to be considered. Eventually, 11 SNPs (rs2236455, rs114220916, rs9980080, rs2236467, rs13048803, rs2838942, rs9980525, rs3753019, rs2236483, rs12483377, rs7867) were chosen.

2.4. Genotyping

Peripheral whole blood specimens were collected from each enrolled patient. All these samples were used to extract genomic deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) via QLAamp® DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany). Then, the custom‐by‐design 2x48‐Plex SNPscanTM kit (Genesky Biotechnologies Inc, Shanghai, China) was utilized for genotyping all SNPs. All processes were carried out in accordance with the instructions.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Categorical variables such as gender and drinking statuses were compared by chi‐square (χ2) or Fisher's exact test, whereas continuous variables such as age and serum ALT levels were compared by Mann‐Whitney's U test. The Hardy‐Weinberg equilibrium (HWE), allelic and genotypic frequencies, and genetic models (addictive, dominant and recessive model) were all performed by Plink (version 1.07). Multivariate logistic regression analyses were used to adjust potential impact factors via SPSS (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA; Version 22.0). Linkage disequilibrium (LD) and haplotype association were analyzed by both Haploview (The Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA, USA; Version 4.1) and online tool SNPstats (https://www.snpstats.net/preproc.php). Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for correlations. P valve ≤ 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Statistical Power was calculated by Power and Sample Size Program software. Ordinary one‐way ANOVA was conducted by GraphPad Prism (version 8.0).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Study characteristics

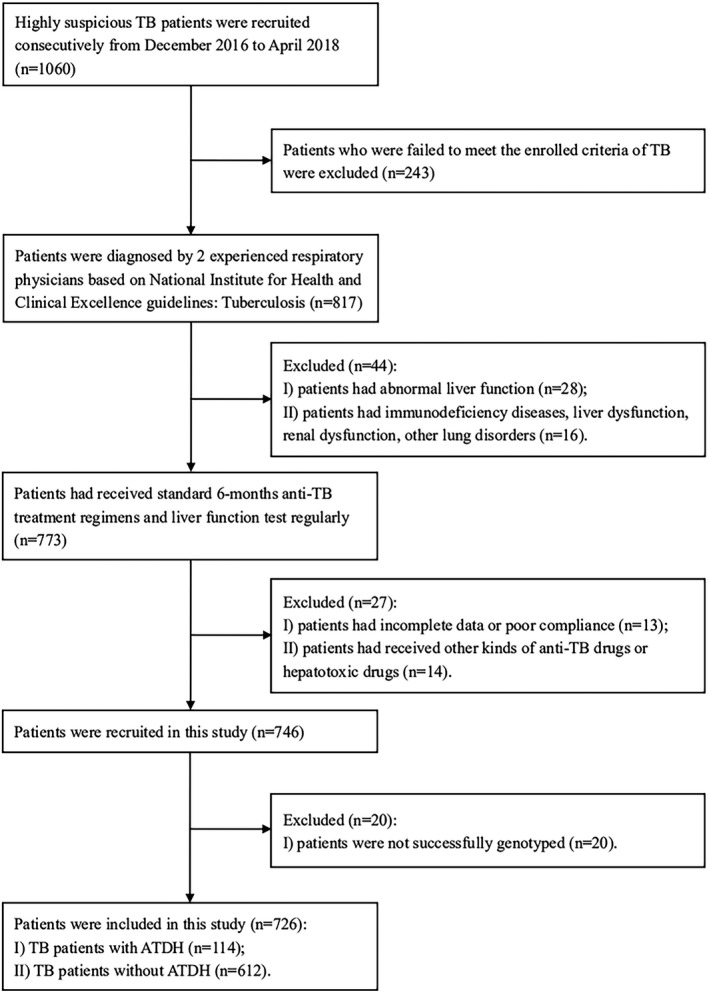

A total of 746 TB patients were included in our study, while 726 patients were successfully genotyped with all selected SNPs (Figure 1). The incidence rate of ATDH was 15.70% (114/726). No differences in age (P = 0.240) and gender (P = 0.752) were found between the cases and the controls. Significant differences in the incidence of fever (P = 0.007), weight loss (P = 0.036), total bilirubin levels (P = 0.003), serum ALT levels (P < 0.001), serum AST levels (P < 0.001), uric acid levels (P = 0.019), alkaline phosphatase (ALP) levels (P = 0.010), and gamma glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) levels (P < 0.001) were observed between these two groups. The demographic and clinical characteristics of all enrolled 726 patients are depicted in Table S1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of selection of patients enrolled. Abbreviations: TB: tuberculosis; ATDH: anti‐tuberculosis drug‐induced hepatotoxicity

3.2. Single selected SNP association with ATDH

All of the 11 SNPs genotypes from the controls did not deviate from the HWE. The mutant A allele frequency of rs12483377 was 0.46% and 3.29% in the cases and the controls, respectively. The mutant A allele conferred the decreased risk of ATDH (OR = 0.13, 95%CI: 0.02–0.98, P = 0.020). Logistic regression showed that this significance still existed after adjusting age and gender (P = 0.024), and the statistical power is 0.77 (Table 1). No case harbored AA genotype of rs12483377, while there were 2 patients with AA genotype in the controls. For the AG genotype of rs12483377, there was 1 and 35 subjects in the ATDH group and non‐ATDH group, respectively. However, as shown in Table 2, comparable risk of ATDH was identified in these 3 genetic models of rs12483377. As for the genetic models of the other 10 selected SNPs, none of them reach the threshold value of statistical significance.

Table 1.

The distributions of allelic and genotypic frequency between non‐ATDH a and ATDH b for the selected 11 SNPs

| SNP | Allele | Group | Allele | Genotype | PHWE | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 b /2 b | OR (95% CI) | P | P * | Power | 11 b /12 b /22 b | P | P * | ||||

| rs2236455 | A>G | ATDH a | 56/172 | 0.92 (0.67–1.29) | 0.653 | 0.449 | 9/38/67 | 0.829 | 0.543 | 0.311 | |

| Non‐ATDH a | 318/906 | 48/222/342 | 0.171 | ||||||||

| rs114220916 | G>A | ATDH a | 15/213 | 1.11 (0.63–2.00) | 0.721 | 0.821 | 0/15/99 | NA | 0.752 | 1.000 | |

| Non‐ATDH a | 73/1151 | 0/73/539 | 0.157 | ||||||||

| rs9980080 | G>A | ATDH a | 40/188 | 1.07 (0.74–1.56) | 0.722 | 0.785 | 3/34/77 | 0.635 | 0.590 | 1.000 | |

| Non‐ATDH a | 203/1021 | 22/159/431 | 0.143 | ||||||||

| rs2236467 | G>A | ATDH a | 16/212 | 1.09 (0.63–1.91) | 0.752 | 0.980 | 0/16/98 | NA | 0.790 | 1.000 | |

| Non‐ATDH a | 79/1145 | 0/79/533 | 0.166 | ||||||||

| rs13048803 | G>A | ATDH a | 39/189 | 1.10 (0.75–1.60) | 0.635 | 0.705 | 2/35/77 | 0.763 | 0.578 | 0.521 | |

| Non‐ATDH a | 194/1030 | 13/168/431 | 0.546 | ||||||||

| rs2838942 | A>G | ATDH a | 16/212 | 1.09 (0.63–1.91) | 0.752 | 0.963 | 0/16/98 | NA | 0.792 | 1.000 | |

| Non‐ATDH a | 79/1145 | 0/79/533 | 0.166 | ||||||||

| rs9980525 | G>A | ATDH a | 39/189 | 1.12 (0.77–1.64) | 0.547 | 0.631 | 2/35/77 | 0.777 | 0.528 | 0.521 | |

| Non‐ATDH a | 190/1034 | 11/168/533 | 0.284 | ||||||||

| rs3753019 | G>A | ATDH a | 108/120 | 1.11 (0.84–1.48) | 0.456 | 0.455 | 27/54/33 | 0.460 | 0.869 | 0.578 | |

| Non‐ATDH a | 547/677 | 115/317/180 | 0.253 | ||||||||

| rs2236483 | G>A | ATDH a | 93/135 | 0.82 (0.61–1.09) | 0.168 | 0.199 | 18/57/39 | 0.322 | 0.364 | 0.846 | |

| Non‐ATDH a | 560/664 | 134/292/186 | 0.330 | ||||||||

| rs12483377 | G>A | ATDH a | 1/227 | 0.13 (0.02–0.98) c | 0.020 | 0.024 | 0.77 | 0/1/113 | NA | 0.055 | 1.000 |

| Non‐ATDH a | 39/1185 | 2/35/575 | 0.119 | ||||||||

| rs7867 | A>G | ATDH a | 98/130 | 0.86 (0.65–1.15) | 0.32 | 0.262 | 23/52/39 | 0.592 | 0.298 | 0.450 | |

| Non‐ATDH a | 570/654 | 139/292/181 | 0.330 | ||||||||

Abbreviations: CI, Confidence interval; HWE, Hardy‐Weinberg equilibrium; NA, Non‐available; OR, Odd ratio; SNP, Single nucleotide polymorphisms.

Non‐ATDH and ATDH refer to patients without and with anti‐tuberculosis drug‐induced hepatotoxicity, respectively;

“1”: mutant allele; “2”: wild allele; “11”: mutant homozygote; “12”: heterozygote; “22”: wild homozygote;

Statistically significant data will be highlighted in bold.

P value after adjusting the age and gender.

Table 2.

Genetic models analyses of the selected 11 SNPs

| SNP | Model | OR (95% CI) | P | P *, a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs2236455 (A>G) | Add | 0.93 (0.68–1.28) | 0.663 | 0.845 |

| Dom | 0.89 (0.59–1.33) | 0.568 | 0.538 | |

| Rec | 1.01 (0.48–2.12) | 0.985 | 0.950 | |

| rs114220916 (G>A) | Add | 1.12 (0.62–2.03) | 0.712 | NA |

| Dom | 1.12 (0.62–2.03) | 0.712 | 0.752 | |

| Rec | NA (NA– NA) | NA | NA | |

| rs9980080 (G>A) | Add | 1.07 (0.74–1.54) | 0.728 | 0.752 |

| Dom | 1.14 (0.75–1.76) | 0.538 | 0.571 | |

| Rec | 0.72 (0.21–2.46) | 0.606 | 0.590 | |

| rs2236467 (G>A) | Add | 1.10 (0.62–1.97) | 0.743 | NA |

| Dom | 1.10 (0.62–1.97) | 0.743 | 0.790 | |

| Rec | NA (NA–NA) | NA | NA | |

| rs13048803 (G>A) | Add | 1.10 (0.75–1.62) | 0.629 | 0.859 |

| Dom | 1.14 (0.75–1.76) | 0.538 | 0.571 | |

| Rec | 0.82 (0.18–3.70) | 0.799 | 0.819 | |

| rs2838942 (A>G) | Add | 1.10 (0.62–1.97) | 0.743 | NA |

| Dom | 1.10 (0.62–1.97) | 0.743 | 0.792 | |

| Rec | NA (NA–NA) | NA | NA | |

| rs9980525 (G>A) | Add | 1.13 (0.77–1.67) | 0.537 | 0.998 |

| Dom | 1.16 (0.76–1.79) | 0.492 | 0.525 | |

| Rec | 0.98 (0.21–4.46) | 0.975 | 0.938 | |

| rs3753019 (G>A) | Add | 1.12 (0.84–1.49) | 0.448 | 0.416 |

| Dom | 1.02 (0.66–1.59) | 0.920 | 0.951 | |

| Rec | 1.13 (0.83–2.16) | 0.228 | 0.213 | |

| rs2236483 (G>A) | Add | 0.82 (0.62–1.09) | 0.174 | 0.140 |

| Dom | 0.84 (0.55–1.23) | 0.419 | 0.420 | |

| Rec | 0.67 (0.39–1.15) | 0.143 | 0.132 | |

| rs12483377 (G>A) | Add | 0.14 (0.02–1.04) | 0.054 | 0.999 |

| Dom | 0.14 (0.02–1.01) | 0.051 | 0.055 | |

| Rec | NA (NA–NA) | NA | 0.999 | |

| rs7867 (A>G) | Add | 0.87 (0.66–1.15) | 0.330 | 0.337 |

| Dom | 0.81 (0.53–1.23) | 0.323 | 0.308 | |

| Rec | 0.86 (0.52–1.41) | 0.551 | 0.522 |

Abbreviations: Add, Addictive model; CI, Confidence interval; Dom, Dominant model; NA, Non‐available; OR, Odd ratio; Rec, Recessive model; SNP, Single nucleotide polymorphisms.

P value after adjusting the age and gender.

3.3. Haplotype construction

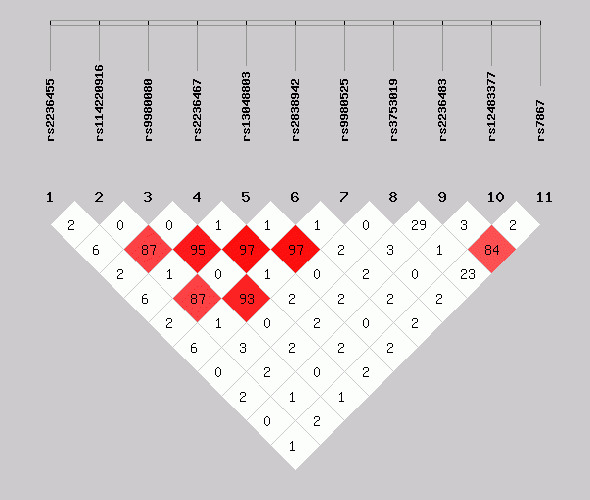

With a threshold of pairwise r 2 value ≥ 0.80, 3 SNPs (rs114220916, rs9980080, and rs2236467) were in a LD block as well as 3 SNPs (rs2236467, rs13048803, and rs2838942), 5 SNPs (rs114220916, rs9980080, rs2236467, rs13048803, and rs2838942), 5 SNPs (rs9980080, rs2236467, rs13048803, rs2838942, and rs9980525) and 3 SNPs (rs2236483, rs12483377, and rs7867). However, none of the constructed haplotypes of COL18A1 showed the significant associations with the risk of ATDH (Table 3). The LD plot of selected SNPs are presented in the Figure 2.

Table 3.

| Haplotype | OR (95% CI) | P | Frequency | Cumulative | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALL(n = 726) | ATDH * , a (n = 112) | Non‐ATDH * , a (n = 614) | Frequency | ||||

| Rs114220916‐ rs2236467 | GGG | 1.00 (NA–NA) | NA | 0.77 | 0.76 | 0.78 | 0.77 |

| GAG | 0.87 (0.59–1.29) | 0.49 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.93 | |

| AGA | 0.79 (0.42–1.49) | 0.47 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.99 | |

| Rs2236467‐ rs2838942 | GGA | 1.00 (NA–NA) | NA | 0.77 | 0.76 | 0.78 | 0.77 |

| GAA | 0.89 (0.60–1.31) | 0.55 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.93 | |

| AGG | 0.87 (0.48–1.57) | 0.65 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 1.00 | |

| Rs114220916‐ rs2838942 | GGGGA | 1.00 (NA–NA) | NA | 0.77 | 0.76 | 0.78 | 0.77 |

| GAGAA | 0.86 (0.58–1.28) | 0.46 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.93 | |

| AGAGG | 0.79 (0.42–1.49) | 0.46 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.99 | |

| Rs9980080‐ rs9980525 | GGGAG | 1.00 (NA–NA) | NA | 0.77 | 0.76 | 0.78 | 0.77 |

| AGAAA | 0.84 (0.56–1.26) | 0.39 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.93 | |

| GAGGG | 0.82 (0.45–1.53) | 0.54 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.99 | |

| Rs2236483‐ rs7867 | GGA | 1.00 (NA–NA) | NA | 0.52 | 0.55 | 0.52 | 0.52 |

| AGG | 1.14 (0.85–1.53) | 0.38 | 0.41 | 0.39 | 0.41 | 0.93 | |

| GGG | 0.58 (0.27–1.25) | 0.17 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.96 | |

| AAG | 6.69 (0.92–48.87) | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.98 | |

| AGA | 0.75 (0.24–2.31) | 0.61 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 1.00 | |

Abbreviations: Add, Addictive model; CI, Confidence interval; NA, Non‐available; OR, Odd ratio.

Non‐ATDH and ATDH refer to patients without and with anti‐tuberculosis drug‐induced hepatotoxicity, respectively.

Figure 2.

Linkage disequilibrium (LD) map of all single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in Collagen type XVIII alpha 1 chain (COL18A1). The threshold was set at pairwise r 2 > 0.80. The color of diamonds, paired with the percentages in diamonds, indicates the pairwise r 2 of all selected SNPs. Namely, the darker the color is, the higher the percentage is

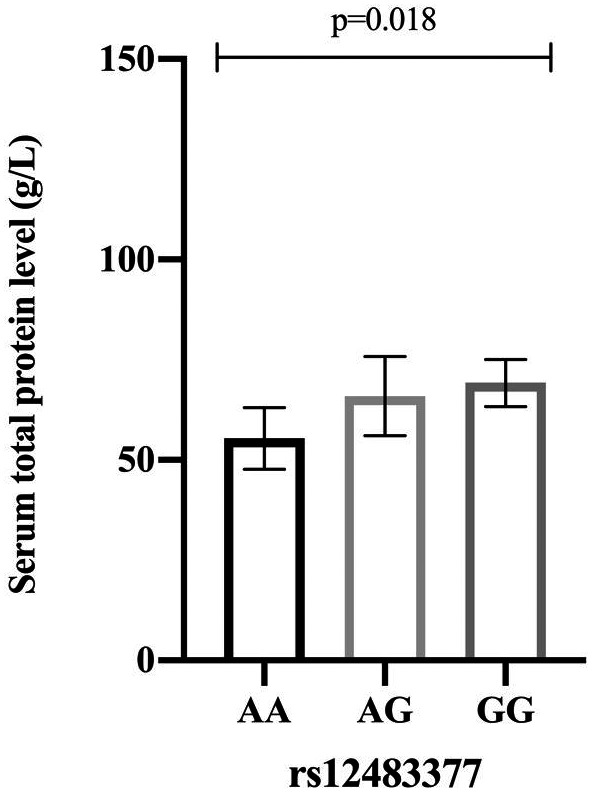

3.4. The correlation within SNPs and laboratory indicators

For rs12483377, mutant homozygote AA genotype was associated with lower total protein (P = 0.018). However, no significant findings on the relationship between rs12483377 and other clinical characteristics were observed (Figure 3). The total protein levels under different genotypes were displayed in Table 4.

Figure 3.

The association between rs12483377 and serum total protein level (g/L) among enrolled patients

Table 4.

The correlation within rs12483377 and total protein

| Genotype | Number | Median (percent 25%–75%) |

|---|---|---|

| AA | 2 | 55.40 (51.55–59.25) |

| AG | 36 | 69.10 (59.70–72.50) |

| GG | 688 | 69.65 (63.90–75.30) |

4. DISCUSSION

In this present study, we investigated the relationship between COL18A1 polymorphisms and the risk of ATDH in the Western Chinese Han population. We revealed that the mutant A allele of CLO18A1 rs12483377 was associated with decreased risk of ATDH. Furthermore, the statistical significance of rs12483377 on total protein had been identified.

COL18A1, highly expressing in the liver (http://biogps.org/#goto=genereport&id=80781), is closely related to liver diseases. 25 , 42 , 43 Musso et al 44 have reported the relationship between COL18A1 and liver fibrosis. Type XVIII collagen, encoded by COL18A1, can increase before and during the fibrotic stages of liver fibrosis. 45 , 46 The increased type XVIII collagen upregulates its own product, EST. EST is able to resist liver fibrosis by inhibiting the expression of TGF‐β1 mRNA through RhoA/ROCK signal pathways in hepatic stellate cells (HSCs). 47 , 48 In addition, liver fibrosis refers to the progression of extracellular matrix excessive deposition, which is often promoted by the activation of HSCs. HSCs can transdifferentiate into cells which can secrete extracellular matrix. 49 , 50 , 51 Therefore, COL18A1 is associated with liver fibrosis via regulating the expression of EST COL18A1 is also related to hepatic carcinoma by EST. 52 EST can inhibit endogenous angiogenesis by suppressing the production of angiogenic factors, while angiogenesis is a common physiological and pathological process in liver cancer. 53 , 54 Besides, the relationship between COL18A1 polymorphisms and liver cancer is also reported. Wu et al 36 have suggested that COL18A1 rs7499, located in the 3’‐UTR region, increases the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in Chinese Han population by negatively working in the binding site for has‐mir‐328. Based on these relationships, both COL18A1 and its product, EST, are considered as targets of liver cancer due to their function of restricting of endothelial proliferation and inhibiting the growth and metastasis of tumors. 55 , 56 , 57 Furthermore, Duncan et al 30 have revealed that type XVIII collagen is vital to preserve the integrity of liver during hepatotoxic injury through α1β1 integrin, integrin linked kinase and the Akt pathway. COL18A1 is thus identified as a necessary survival factor of acute liver injury from carbon tetrachloride.

In our study, we firstly reported the relationship between COL18A1 variants and ATDH susceptibility. We found that rs12483377 is associated with decreased risk of ATDH. It has been verified that the mutant A allele of rs2483377 could decrease the ability of EST to bind other molecules and the function to inhibit angiogenesis. 58 Considering the role of EST in the occurrence of ATDH as we described before, we deduced that rs12483377 may influence ATDH by regulating the expression of EST which participates in oxidative stress. 20 , 26 , 27 In addition, it is well‐recognized that expression quantitative trait locus (eQTL) regulates the expression level of mRNA and protein specifically, and the expression level of mRNA/protein is proportional to the quantitative character. 59 , 60 Rs12483377 has 2 hits of cis eQTL hits (http://pubs.broadinstitute.org/mammals/haploreg/detail_v4.1.php?query=&id=rs12483377). It is reported that rs12483377 involved in regulating the expression of both COL18A1 and solute carrier family 19 member 1 (SLC19A1). 61 , 62 Thus, we speculated that rs12483377 might reduce the expression of EST through eQTL, and thus functioned in the occurrence of ATDH.

Besides, in our study, there were significant differences in fever, weight loss, total bilirubin levels, serum ALT levels, serum AST levels, uric acid levels, ALP levels, and GGT levels between the case and control group. Fever and weight loss are the common symptoms of tuberculosis poisoning. 63 After Mycobacterium tuberculosis infected the body, it will produce toxins and metabolites, which can not only cause allergic reactions such as fever, fatigue, and so on, but also will stimulate the central nervous system, resulting in dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system which lead to night sweats. 63 , 64 Bilirubin, ALT, AST, ALP, and GGT are all associated with the liver metabolism. 65 , 66 As is stated before, anti‐TB treatment can result in liver injury through four mechanisms. 3 As for uric acid levels, all patients enrolled were treated with INH, RIF, PZA, and EMB, in which INH, PZA, EMB, and their metabolites could compete with uric acid for the organic acid excretion pathway, reducing the excretion of uric acid, thus causing the increase of uric acid y. 67 In this study, a statistical significance on the relationship between mutant homozygote AA and total protein was found. However, after reviewing the relevant literature, it is found that the current reports are not enough to explain the two situations, so it may just be a statistical correlation and may not be of any clinical significance. Meanwhile, after reviewing the specific circumstances of these cases, the impact of the low number of homozygote AA on the analysis in this study can not be ruled out. Furthermore, this may also be an innovative finding, so the recruitment of people for the function verification and larger population verification and so on aiming for rs12483377 is under way.

4.1. Strengths and limitations

We firstly investigated the relationship between COL18A1 polymorphisms and ATDH susceptibility in Western Chinese Han population. Based on available evidence, we also speculated the potential mechanisms that how COL18A1 polymorphisms affect ATDH susceptibility, contributing to the deep understanding of ATDH etiology to some extent. Besides, our finding is beneficial to explore more novel biomarkers of ATDH and decrease the burden brought by ATDH to some degree. Nevertheless, there were still some limitations in our study. The design of single center study restricts us to verify our findings in different ethnicities. Functional experiment about rs12483377 should have been further performed to validate our speculation. More high‐quality studies with lager cohorts are warranted.

5. CONCLUSION

Collectively, our study revealed that CLO18A1 rs12483377 is related to the risk and specific characteristic of ATDH in the Western Chinese Han population, mining and further emphasizing the role of CLO18A1 variants in ATDH.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Author Yuhui Cheng, Author Lin Jiao, Author Weixiu Li, Author Jialing Wang, Author Zhangyu Lin, Author Hongli Lai, Author Binwu Ying declare that they have no conflict of interest.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Research design: Binwu Ying. Data collection: Yuhui Cheng, Lin Jiao, Weixiu Li, Jialing Wang, Zhangyu Lin. Data analysis: Yuhui Cheng, Lin Jiao, Weixiu Li, Jialing Wang, Zhangyu Lin, Hongli Lai. Project administration: Binwu Ying. Writing‐original draft: All authors. Writing‐revision: All authors.

Supporting information

Table S1

Cheng Y, Jiao L, Li W, et al. Collagen type XVIII alpha 1 chain (COL18A1) variants affect the risk of anti‐tuberculosis drug‐induced hepatotoxicity: A prospective study. J Clin Lab Anal.2021;35:e23630 10.1002/jcla.23630

Yuhui Cheng and Lin Jiao, contributed equally to this work.

Funding informationThis work was supported by the National Science & Technology Pillar Program during the 13th Five‐year Plan Period [Grant 2018ZX10715003].

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All data to this article can be found at the end of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Lee LN, Huang CT. Mitochondrial DNA variants in patients with liver injury due to anti‐tuberculosis drugs. J Clin Med. 2019;8:1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yang LX, Liu CY, Zhang LL, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients with drug‐induced liver injury. Chin Med J (Engl). 2017;130(2):160‐164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bao Y, Ma X, Rasmussen TP, Zhong XB. Genetic variations associated with anti‐tuberculosis drug‐induced liver injury. Curr Pharmacol Rep. 2018;4(3):171‐181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jia ZL, Cen J, Wang JB, et al. Mechanism of isoniazid‐induced hepatotoxicity in zebrafish larvae: activation of ROS‐mediated ERS, apoptosis and the Nrf2 pathway. Chemosphere. 2019;227:541‐550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ramachandran A, Visschers RGJ, Duan L, Akakpo JY, Jaeschke H. Mitochondrial dysfunction as a mechanism of drug‐induced hepatotoxicity: current understanding and future perspectives. J Clin Transl Res. 2018;4(1):75‐100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kim JH, Nam WS, Kim SJ, et al. Mechanism investigation of rifampicin‐induced liver injury using comparative toxicoproteomics in mice. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(7):1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yew WW, Chang KC, Chan DP. Oxidative stress and first‐line antituberculosis drug‐induced hepatotoxicity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018;62(8):e02637‐17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yang S, Hwang SJ, Park JY, Chung EK, Lee JI. Association of genetic polymorphisms of CYP2E1, NAT2, GST and SLCO1B1 with the risk of anti‐tuberculosis drug‐induced liver injury: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. BMJ Open. 2019;9(8):e027940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yee D, Valiquette C, Pelletier M, Parisien I, Rocher I, Menzies D. Incidence of serious side effects from first‐line antituberculosis drugs among patients treated for active tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167(11):1472‐1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Huai C, Wei Y, Li M, et al. Genome‐wide analysis of DNA methylation and antituberculosis drug‐induced liver injury in the han Chinese population. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2019;106(6):1389‐1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bouazzi OE, Hammi S, Bourkadi JE, et al. First line anti‐tuberculosis induced hepatotoxicity: incidence and risk factors. Pan Afr Med J. 2016;25:167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Huang YS. Recent progress in genetic variation and risk of antituberculosis drug‐induced liver injury. J Chin Med Assoc. 2014;77(4):169‐173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhang J, Zhao Z, Bai H, et al. Genetic polymorphisms in PXR and NF‐kappaB1 influence susceptibility to anti‐tuberculosis drug‐induced liver injury. PLoS One. 2019;14(9):e0222033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chen S, Yang P, Chen SP, Wu C, Zhu QX. Association between genetic polymorphisms of NRF2, KEAP1, MAFF, MAFK and anti‐tuberculosis drug‐induced liver injury: a nested case‐control study. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):14311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhang M, Wu SQ, He JQ. Are genetic variations in glutathione S‐transferases involved in anti‐tuberculosis drug‐induced liver injury? A meta‐analysis. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2019;44(6):844‐857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Khan S, Mandal RK, Elasbali AM, et al. Pharmacogenetic association between NAT2 gene polymorphisms and isoniazid induced hepatotoxicity: trial sequence meta‐analysis as evidence. Biosci Rep. 2019;39(1):BSR20180845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lamba J, Lamba V, Strom S, Venkataramanan R, Schuetz E. Novel single nucleotide polymorphisms in the promoter and intron 1 of human pregnane X receptor/NR1I2 and their association with CYP3A4 expression. Drug Metab Dispos. 2008;36(1):169‐181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wang JY, Tsai CH, Lee YL, et al. Gender‐dimorphic impact of PXR genotype and haplotype on hepatotoxicity during antituberculosis treatment. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(24):e982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Karsdal MA, Nielsen SH, Leeming DJ, et al. The good and the bad collagens of fibrosis ‐ their role in signaling and organ function. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2017;121:43‐56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Boodhwani M, Nakai Y, Mieno S, et al. Hypercholesterolemia impairs the myocardial angiogenic response in a swine model of chronic ischemia: role of endostatin and oxidative stress. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81(2):634‐641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yan M, Dongmei B, Jingjing Z, et al. Antitumor activities of Liver‐targeting peptide modified Recombinant human Endostatin in BALB/c‐nu mice with Hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):14074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bao Y, Feng WM, Tang CW, et al. Endostatin inhibits angiogenesis in hepatocellular carcinoma after transarterial chemoembolization. Hepatogastroenterology. 2012;59(117):1566‐1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jin S, Zhang Y, Yi F, Li PL. Critical role of lipid raft redox signaling platforms in endostatin‐induced coronary endothelial dysfunction. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28(3):485‐490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kimura K, Shirabe K, Yoshizumi T, et al. Ischemia‐reperfusion injury in fatty liver is mediated by activated NADPH Oxidase 2 in rats. Transplantation. 2016;100(4):791‐800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chau YP, Lin SY, Chen JH, Tai MH. Endostatin induces autophagic cell death in EAhy926 human endothelial cells. Histol Histopathol. 2003;18(3):715‐726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tao GZ, Lehwald N, Jang KY, et al. Wnt/beta‐catenin signaling protects mouse liver against oxidative stress‐induced apoptosis through the inhibition of forkhead transcription factor FoxO3. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(24):17214‐17224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Seppinen L, Pihlajaniemi T. The multiple functions of collagen XVIII in development and disease. Matrix Biol. 2011;30(2):83‐92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Park WB, Kim W, Lee KL, et al. Antituberculosis drug‐induced liver injury in chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis. J Infect. 2010;61(4):323‐329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Abramavicius S, Velickiene D, Kadusevicius E. Methimazole‐induced liver injury overshadowed by methylprednisolone pulse therapy: case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(39):e8159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Duncan MB, Yang C, Tanjore H, et al. Type XVIII collagen is essential for survival during acute liver injury in mice. Dis Model Mech. 2013;6(4):942‐951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mijiti P, Yuehua L, Feng X, et al. Prevalence of pulmonary tuberculosis in western China in 2010–11: a population‐based, cross‐sectional survey. Lancet Glob Health. 2016;4(7):e485‐e494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Turnbull L, Bell C, Child F. Tuberculosis (NICE clinical guideline 33). Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2017;102(3):136‐142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ho CC, Chen YC, Hu FC, et al. Safety of fluoroquinolone use in patients with hepatotoxicity induced by anti‐tuberculosis regimens. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48(11):1526‐1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Locke AE, Dooley KJ, Tinker SW, et al. Variation in folate pathway genes contributes to risk of congenital heart defects among individuals with Down syndrome. Genet Epidemiol. 2010;34(6):613‐623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Castro‐Giner F, Bustamante M, Ramon González J, et al. A pooling‐based genome‐wide analysis identifies new potential candidate genes for atopy in the European Community Respiratory Health Survey (ECRHS). BMC Med Genet. 2009;10:128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wu X, Wu J, Xin Z, et al. A 3' UTR SNP in COL18A1 is associated with susceptibility to HBV related hepatocellular carcinoma in Chinese: three independent case‐control studies. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e33855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yip SP, Leung KH, Fung WY, et al. A DNA pooling‐based case‐control study of myopia candidate genes COL11A1, COL18A1, FBN1, and PLOD1 in a Chinese population. Mol Vis. 2011;17:810‐821. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Defago MD, Gu D, Hixson JE, et al. Common genetic variants in the endothelial system predict blood pressure response to sodium intake: the GenSalt study. Am J Hypertens. 2013;26(5):643‐656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17(5):405‐424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Schalkwyk LC, Meaburn EL, Smith R, et al. Allelic skewing of DNA methylation is widespread across the genome. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;86(2):196‐212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Metayer C, Scélo G, Chokkalingam AP, et al. Genetic variants in the folate pathway and risk of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Causes Control. 2011;22(9):1243‐1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Jia JD, Bauer M, Sedlaczek N, et al. Modulation of collagen XVIII/endostatin expression in lobular and biliary rat liver fibrogenesis. J Hepatol. 2001;35(3):386‐391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hsieh MY, Lin ZY, Chuang WL. Serial serum VEGF‐A, angiopoietin‐2, and endostatin measurements in cirrhotic patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated by transcatheter arterial chemoembolization. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2011;27(8):314‐322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Akhdar H, El Shamieh S, Musso O, et al. The rs3957357C>T SNP in GSTA1 is associated with a higher risk of occurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma in european individuals. PLoS One. 2016;11(12):e0167543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Schuppan D, Cramer T, Bauer M, Strefeld T, Hahn EG, Herbst H. Hepatocytes as a source of collagen type XVIII endostatin. Lancet. 1998;352(9131):879‐880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Jia J, Bauer M, Boigk G, Ruehl M, Schuppan D, Wang B. Expression of collagen XVIII mRNA in rat liver fibrosis. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi. 2000;8(5):274‐275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ren H, Li Y, Chen Y, Wang L. Endostatin attenuates PDGF‐BB‐ or TGF‐beta1‐induced HSCs activation via suppressing RhoA/ROCK1 signal pathways. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2019;13:285‐290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Chen J, Liu DG, Yang G, et al. Endostar, a novel human recombinant endostatin, attenuates liver fibrosis in CCl4‐induced mice. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2014;239(8):998‐1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Cheng Q, Li C, Yang CF, et al. Methyl ferulic acid attenuates liver fibrosis and hepatic stellate cell activation through the TGF‐beta1/Smad and NOX4/ROS pathways. Chem Biol Interact. 2019;299:131‐139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Friedman SL. Molecular regulation of hepatic fibrosis, an integrated cellular response to tissue injury. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(4):2247‐2250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tsuchida T, Friedman SL. Mechanisms of hepatic stellate cell activation. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14(7):397‐411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Walia A, Yang JF, Huang YH, Rosenblatt MI, Chang JH, Azar DT. Endostatin's emerging roles in angiogenesis, lymphangiogenesis, disease, and clinical applications. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1850(12):2422‐2438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Chamani R, Asghari SM, Alizadeh AM, et al. Engineering of a disulfide loop instead of a Zn binding loop restores the anti‐proliferative, anti‐angiogenic and anti‐tumor activities of the N‐terminal fragment of endostatin: Mechanistic and therapeutic insights. Vascul Pharmacol. 2015;72:73‐82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Li T, Kang G, Wang T, Huang H. Tumor angiogenesis and anti‐angiogenic gene therapy for cancer. Oncol Lett. 2018;16(1):687‐702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Bao D, Jin X, Ma Y, Zhu J. Comparison of the structure and biological activities of wild‐type and mutant liver‐targeting peptide modified recombinant human endostatin (rES‐CSP) in human hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells. Protein Pept Lett. 2015;22(5):470‐479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Poluzzi C, Iozzo RV, Schaefer L. Endostatin and endorepellin: a common route of action for similar angiostatic cancer avengers. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2016;97:156‐173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ding RL, Xie F, Hu Y, et al. Preparation of endostatin‐loaded chitosan nanoparticles and evaluation of the antitumor effect of such nanoparticles on the Lewis lung cancer model. Drug Deliv. 2017;24(1):300‐308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Lurje G, Husain H, Power DG, et al. Genetic variations in angiogenesis pathway genes associated with clinical outcome in localized gastric adenocarcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(1):78‐86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Verta JP, Landry CR, MacKay J. Dissection of expression‐quantitative trait locus and allele specificity using a haploid/diploid plant system ‐ insights into compensatory evolution of transcriptional regulation within populations. New Phytol. 2016;211(1):159‐171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Tian J, Keller MP, Broman AT, et al. The dissection of expression quantitative trait locus hotspots. Genetics. 2016;202(4):1563‐1574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Fehrmann RS, Jansen RC, Veldink JH, et al. Trans‐eQTLs reveal that independent genetic variants associated with a complex phenotype converge on intermediate genes, with a major role for the HLA. PLoS Genet. 2011;7(8):e1002197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Westra HJ, et al. Systematic identification of trans eQTLs as putative drivers of known disease associations. Nat Genet. 2013;45(10):1238‐1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Singer‐Leshinsky S. Pulmonary tuberculosis: Improving diagnosis and management. JAAPA. 2016;29(2):20‐25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Fealey RD. Interoception and autonomic nervous system reflexes thermoregulation. Handb Clin Neurol. 2013;117:79‐88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Kietzmann T. Metabolic zonation of the liver: The oxygen gradient revisited. Redox Biol. 2017;11:622‐630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Reinke H, Asher G. Circadian clock control of liver metabolic functions. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(3):574‐580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Louthrenoo W, Hongsongkiat S, Kasitanon N, et al. Effect of antituberculous drugs on serum uric acid and urine uric acid excretion. J Clin Rheumatol. 2015;21(7):346‐348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1

Data Availability Statement

All data to this article can be found at the end of this manuscript.