Abstract

Adaptation in new environments depends on the amount of genetic variation available for evolution, and the efficacy by which natural selection discriminates among this variation. However, whether some ecological factors reveal more genetic variation, or impose stronger selection pressures than others, is typically not known. Here, we apply the enzyme kinetic theory to show that rising global temperatures are predicted to intensify natural selection throughout the genome by increasing the effects of DNA sequence variation on protein stability. We test this prediction by (i) estimating temperature-dependent fitness effects of induced mutations in seed beetles adapted to ancestral or elevated temperature, and (ii) calculate 100 paired selection estimates on mutations in benign versus stressful environments from unicellular and multicellular organisms. Environmental stress per se did not increase mean selection on de novo mutation, suggesting that the cost of adaptation does not generally increase in new ecological settings to which the organism is maladapted. However, elevated temperature increased the mean strength of selection on genome-wide polymorphism, signified by increases in both mutation load and mutational variance in fitness. These results have important implications for genetic diversity gradients and the rate and repeatability of evolution under climate change.

Keywords: temperature, selection, mutation, climate change, enzyme kinetics, protein stability

1. Background

The strength of natural selection impacts on the rate and repeatability of evolution [1–5], the maintenance of genetic variation [6,7] and extinction risk [8,9]. However, despite being central to predicting the impacts of climate change, there is little information about whether some environmental factors impose stronger selection pressures than others. Mapping of the environment's influence on phenotype and fitness is therefore of paramount importance to understanding species persistence [10–14].

It is widely recognized that environmental change should increase the strength of directional selection on the genes of key ecological traits underlying local adaptation. However, the fitness consequences associated with maladaptation at such genes may be relatively small compared to the genetic load on fitness attributed to the polymorphisms segregating across the entire genome [8,15]. This reservoir of genetic variation is expected to have a fundamental impact on adaptability and extinction risk [8,9,15], but how the environment influences the expression and consequences of genome-wide polymorphism remains poorly understood. For example, it is sometimes argued that fitness effects of genetic variation may become magnified in stressful environments owing to compromised genetic robustness (i.e. decanalization) and the release of ‘cryptic genetic variation' [16,17], suggesting that the fitness load attributed to genetic polymorphisms could increase in new environments. However, alleles with deleterious effects in the ancestral environment will have been removed more efficiently by selection than those alleles with conditional effects limited to the new conditions. Hence, an increase in genetic variation for fitness in new environments may not reflect a general increase in the strength of selection on genetic polymorphisms, but rather more polymorphism at the specific loci that become exposed to selection.

This confounding effect of evolutionary history on the expression of standing genetic variation does not to the same extent apply to new mutations, suggesting that the study of fitness effects of de novo mutations can offer more general insights into how the strength of selection on genetic polymorphism changes across environments. It has been suggested that the loss of genetic robustness in stressful environments also may increase the fitness effects of (and selection on) de novo mutation [16,18,19]. Moreover, theory based on Fisher's geometric model of adaptation [3] predicts that stressful environments should impose directional selection on mutations, resulting in increased mutational variance for fitness [11,20]. However, empirical evidence for increases in genetic variation (standing or de novo) in stressful environments remains ambiguous [11,20–23].

Here, we illustrate how considerations of thermodynamic constraints on proteins can generate predictions about how climate change and regional temperatures affect the strength of selection on DNA sequences. Thermodynamics pose a fundamental constraint on protein function, and although there is room for organismal adaptation to circumvent these deterministic effects [24], there is a strong temperature dependence of ectotherm behaviour, life-history and fitness [25,26]. By adopting previous biophysical models on enzyme kinetics and protein stability [27–30], we first show that elevated temperatures are predicted to increase the fitness effects of de novo mutations in protein-coding genes. We then test this prediction by measuring selection on induced mutations at benign and elevated temperature in experimental evolution lines of the seed beetle, Callosobruchus maculatus, adapted to ancestral or warm temperature. Finally, we analyse 100 published estimates of paired selection coefficients against de novo mutations in benign versus stressful environments from a diverse set of ectothermic organisms. Our analyses suggest that environmental stress per se does not affect the mean strength of selection but provide support for the prediction that elevated temperature leads to an average increase in genome-wide selection and mutational variance in fitness. These results have important implications for global patterns of genetic diversity and extinction risk under future climate change.

2. Methods

(a). Enzyme kinetics theory predicts temperature dependence of mutational fitness effects

Biological rates of ectotherms show a well-characterized empirical relationship with a temperature that closely mirrors the thermodynamic performance of enzymes [24,26]. This is because biological rates are governed at the biochemical level by the enzymatic catalytic rate, kcat. According to the mechanistic understanding of chemical reactions provided by transition state theory [31,32]:

| 2.1 |

where ΔGa is the Gibbs free energy of activation required for the enzymatic reaction (kcal mol−1), R is the universal gas constant (0.002 kcal mol−1), T is temperature measured in Kelvin and k0 = ҡkBT/h, where ҡ is a rate specific constant, kB is the Boltzmann constant and h is Planck's constant. Equation (2.1) thus describes an increase in reaction rate with temperature (figure 1a).

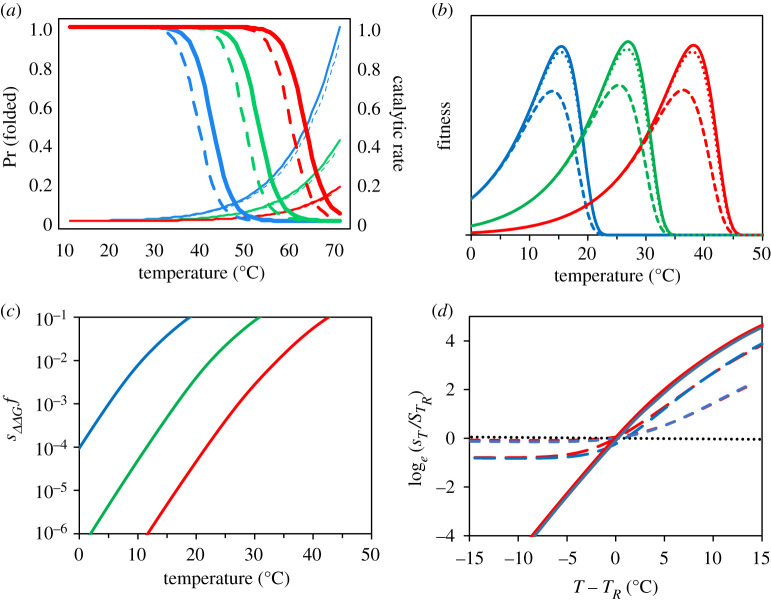

Figure 1.

An enzyme kinetic model of temperature-dependent mutational fitness effects. In (a) thin lines show the catalytic rate (equation (2.1)) for three hypothetical wild-type (full lines) and mutant (dashed lines) proteins (from left to right: ; blue = 19.2; green = 19.85; red = 20.6 kcal mol−1, and ΔΔGa = 0.063 kcal mol−1, resulting in s = 0.10). Catalytic rate is shown scaled relative to the blue genotype at 70°C. The relative difference in catalytic rate between wild-type and mutant remains almost unchanged as temperature increases and is the same for all three proteins. Thick lines give the fraction of folded protein (equation (2.2)) for wild-type (full lines) and a mutant (dashed lines) with a single stability mutation ΔΔGf = 1 kcal mol−1. Illustrated for an unstable (blue) intermediate (green) and stable (red) protein ( and –9 kcal mol−1, respectively). The relative difference in folding between wild-type and mutant increases with temperature. In (b), expected mean fitness for three genotypes with an ensemble of 500 multiplicatively acting proteins with different mean stabilities () (blue, green and red lines reflect values of −6, −9 and −12 kcal mol−1 at 298 K, and ΔGa values as in (a). Solid lines = wild-type (equation (2.3)), short-dashed lines = mutant carrying a single-folding mutation, long-dashed lines = mutant carrying 10-folding mutations (equation (2.4)). Mutations were drawn from the empirical normal distribution (ΔΔGf = 1 kcal mol−1 ± 1.7 s.d.). In (c), the expected mean selection coefficient against a single-folding mutation occurring at a random gene for each of the three genotypes (equation (2.6)). Notice the log scale. In (d), ‘warm' and ‘cold’ adapted genotypes experience equivalent strengths of selection when fitness effects are assessed at a temperature standardized relative to each genotype's thermal optimum (TR = TOPT − 10°C, for clarity only reaction norms for Δ and −12 are shown). Mutational fitness effects on catalytic rate (ΔΔGa) show no discernible temperature dependence (black dotted line; here ΔΔGa lowers fitness at Topt by s = 10−2). However, if a mutant lineage carries both ΔΔGf and ΔΔGa mutations, the temperature dependence of selection against the mutant brought about by the folding mutations can be masked (full, long-dash and short-dash lines equate to a s(ΔΔGa) = 0, 10−3 and 10−2 at Topt). All examples used a value of ΔSf = −0.25 kcal mol−1 K−1 and assumed that mutations affected stability and catalytic rate via changes in enthalpy (ΔΔHf and ΔΔHa). (Online version in colour.)

The observed decline in biological rate at temperatures exceeding the organism's thermal optimum is attributed to a reduction in the proportion of functional enzyme due to reversable inactivation via protein unfolding [33–36] (figure 1a). Protein folding can be described by a Boltzmann probability as a function of the Gibbs free energy of folding, ΔGf, which is thus a measure of protein stability [34]:

| 2.2 |

At a benign temperature of 25°C, most natural proteins occur in functional (properly folded) state and the value of the Gibbs energy is negative (mean ΔGf ∼ −7 kcal mol−1; [27,34]. Both ΔGa and ΔGf are however comprised an enthalpy term (ΔH) and a temperature-dependent entropy term (ΔS) [37] that reduces to: ΔG(T) = ΔH − TΔS over the ecologically relevant temperature range of most organisms [28]. Based on values from the literature [28,38], ΔSf ∼ − 0.25 to −0.50 kcal mol−1 K−1 for a protein of typical length. From equation (2.2), it is therefore clear that warm temperatures increase entropy by making ΔGf less negative, which leads to a rapid and nonlinear reduction in the fraction of folded (functional) enzyme (figure 1a).

Following previous models linking protein function to organismal fitness (e.g. [26,27,29,32]), the reaction rate kinetics of equation (2.1) can be combined with the protein folding of equation (2.2) to describe the performance of enzyme, i, as a function of temperature and the Gibbs energies for activation and folding [28,29]:

| 2.3 |

Here, we use equation (2.3) to explore the effect of temperature on the strength of selection on de novo mutations that impact catalytic rate and protein folding stability (figure 1a,b). While doing so, our model, as previous models (reviewed in: [33,36]), equate protein function with natural selection at the organismal level. This assumes that the fitness of an individual is proportional to the rate at which it generates functional enzyme, which is clearly simplistic considering (i) the molecular complexity of protein–protein interactions and resulting genetic epistasis, and (ii) the ecological complexity affecting the link between rates of biochemical reactions and offspring production. Yet, this simplicity allows building general and testable predictions and is supported qualitatively by the fact that biological rates scale predictably with temperature [25,26]. Hence, we introduce a mutational change in the Gibbs free energy of activation (ΔΔGa = ΔΔHa − TΔΔSa) and folding (ΔΔGf = ΔΔHf − TΔΔSf), respectively:

| 2.4 |

Antagonistic pleiotropy between folding stability and catalytic rate is likely to underlie protein adaptation [24,26], but is rare for de novo mutations [33,36,39]; mutational effects on folding and catalytic rate were therefore assumed to be uncorrelated on average. We further assumed that new mutations do not occur more than once in the same metabolic pathway, and that fitness is the product of metabolic flux through several independent pathways, so that mutational fitness effects are multiplicative. We calculate the Darwinian selection coefficient against a de novo mutation:

| 2.5 |

where and ωT is the fitness of the mutant and the wild-type protein at temperature T. Substituting equations (2.3) and (2.4) into equation (2.5) yields:

| 2.6 |

We here note that corresponding solutions for Malthusian fitness, which is a more accurate currency for microorganisms, produce the same qualitative results. We applied equation (2.6) in numerical simulations to calculate selection on mutation in a random protein with its original stability drawn from a truncated gamma distribution(k = 5.50, θ = 1.89)) derived from empirical data from bacteria, yeast and nematodes [29]. We compared the resulting temperature dependence of selection in three enzyme ensembles with different hypothetical distributions of protein stabilities by shifting the empirical gamma distribution so that mean kcal mol−1, respectively (figure 1b–d). In the example presented in figure 1, we set ΔSf = −0.25 kcal mol−1. In electronic supplementary material, S1, we show results for different values of ΔSf.

De novo mutations commonly affect folding as any change in a protein's three-dimensional structure has potential to affect stability [34,35]. Mutational effects on protein folding (ΔΔGf) are more often destabilizing [33,34,40,41] and the mean impact of a mutation has been estimated to ΔΔGf ≈ 1 kcal mol−1 (s.d. =1.7) [35,42], a value more or less independent of the original protein stability (ΔGf) [27]. Hence, a protein was mutated by sampling a single-folding mutation from this empirically estimated normal distribution. Estimates of mutational effects on the activation energy are probably biased [33] (electronic supplementary material, S1.1). In the simulations, we therefore chose parameter values of ΔΔGa that yielded negative selection coefficients at benign temperature corresponding to empirical observations (sT=298K = 0–10–2).

Mutational effects on the Gibbs energy (ΔΔGa or ΔΔGf) can derive from a combination of both enthalpic (ΔΔH) and entropic (ΔΔS) terms. In the examples in figure 1, we assumed that mutational effects are enthalpic in origin. However, qualitative conclusions hold when mutational effects are modelled through only the entropic term or enthalpic and entropic terms combined (electronic supplementary material, S1.2).

(b). Temperature-dependent fitness effects of mutations in seed beetles adapted to contrasting thermal regimes

To test the model predictions about how elevated temperatures should affect the strength of selection on de novo mutation, we measured fitness effects of induced random mutations at benign (30°C) and elevated (36°C) temperature in seed beetles, C. maculatus, evolved at either 30°C (three control lines) or 36°C (three warm-adapted lines) for more than 70 generations (description of experimental evolution lines in electronic supplementary material, S2). All data on seed beetles can be downloaded from the Dryad Digital Repository: https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.12jm63xx6 [43].

(i). Quantifying thermal adaptation

We first detailed thermal adaptation across the two evolution regimes by analysing differences in offspring production at the two assay temperatures in the current experiment (see below). Second, following 100 generations of experimental evolution and two generations of common-garden acclimation at 30°C (removing non-genetic parental effects), we measured thermal reaction norms for juvenile survival and development rate for two technical replicates per line and a total of 2755 offspring across five temperatures (23, 29, 34.5, 36 and 38°C). Survival was analysed using dead/alive as the binomial response and development rate (1/development time) as a normally distributed response using linear mixed-effects models in the lme4 package [44] for R. Assay temperature and evolution regime, and their interaction, were included as fixed effects, and line identity crossed by assay temperature was added as random effect terms. (Full model-specification and additional methods are in the electronic supplementary material, S2.)

(ii). Quantifying temperature-dependent mutational fitness effects

We reanalysed data from [45] to compare heterozygous fitness effects of induced mutations at 30°C and 36°C for each line. Extended methods and a graphical depiction of the design can be found in the electronic supplementary material, S2 and [45]. All six lines were maintained at 36°C for two generations of common-garden acclimation. The emerging virgin adult offspring of the second generation were used as the F0 individuals of the experiment. We induced mutations by exposing half of the F0 males to gamma radiation at a dose of 20 Grey (20 min treatment), with the other half kept as controls. The dose of radiation was chosen based on a previous experiment that studied mutational fitness effects across three generations in C. maculatus [46]. Gamma radiation causes mutagenic reactive oxygen species as well as double- and single-stranded DNA-breaks, with point mutations arising owing to errors during their repair [47]. Single-base substitutions represent the most common form of mutation while short insertions and deletions are more rare but do commonly occur [47]. However, offspring in the next generation carry an excess of substitutions as the other forms of mutation are often lethal and eliminated [48,49]. Hence, the mutational effects we study here should mostly be ascribed to single-base substitutions, but we cannot exclude effects from structural variants.

All F0 males were mated with virgin females from their own line at benign 30°C. The mated females were immediately placed on beans presented ad libitum and randomized to a climate cabinet set to either 30°C or 36°C (50% relative humidity) and allowed to lay eggs. To exclude non-genetic effects of the irradiation treatment, we measured heterozygous mutational effects in the F2 generation. To this end we applied a middle-class neighbourhood breeding design [50] to nullify selection on all but the unconditionally lethal mutations among F1 juveniles. In brief, we selected two F1 male and female offspring from each F0 family and then performed crosses within treatment and evolution line while avoiding inbreeding. Hence, this procedure made sure that each F0-male contributed the same number of offspring to the next generation, irrespective of the mutations it passed on. From treatment:line combinations with lower numbers of F0-males set-up, we did this procedure twice for a few (randomly selected) F0-males, to get a more balanced sample size.

We quantified the cumulative deleterious fitness effect of the induced mutations (i.e. de novo mutation load) by comparing the production of F2 adults in irradiated lineages, relative to that of corresponding non-irradiated lineages (electronic supplementary material, figure S2.2 ). We also used F1 adult counts to derive an estimate of load, acknowledging that it may include non-trivial paternal effects from the irradiation treatment (specifically, protein damage in the ejaculate caused by ionizing radiation [51]). However, results based on F1 and F2 estimates were qualitatively consistent (figure 2). We analysed the number of offspring produced as a Poisson response, using Bayesian generalized linear mixed-effects models in the MCMCglmm package [52] for R. To estimate the effect of elevated temperature on mutational fitness effects in the two evolution regimes, we tested for statistical interactions between the effects of radiation treatment, assay temperature and evolution regime. We included the six replicate lines crossed with radiation treatment and assay temperature as random effect terms. We also included the date of irradiation as another random effect, crossed with radiation treatment. Full specification of priors, model and output are in the electronic supplementary material, table S2.2.

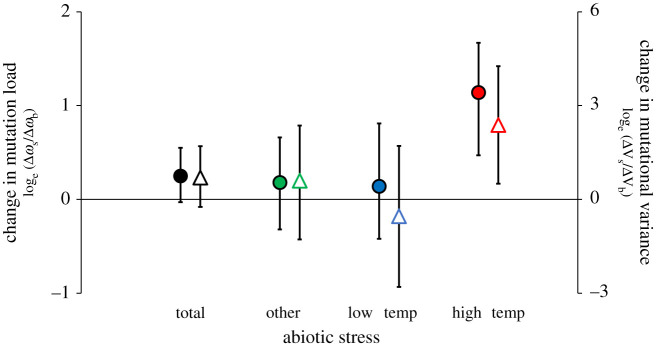

Figure 2.

Temperature-dependent mutational fitness effects in seed beetles. Mutation load (Δω) (Bayesian posterior modes ± 95% credible intervals) measured for (a) F1 and (b) F2 adult offspring production. There was an overall significant increase in Δω at hot temperature. This effect was similar across the three control (blue) and three warm-adapted (red background, black border) lines. (Online version in colour.)

(c). A meta-analysis of temperature-dependent mutational fitness effects

To more generally test if elevated temperatures affect selection on DNA polymorphisms, we updated the datasets presented in the previous reviews by Martin & Lenormand [20] and Agrawal & Whitlock [11] on the environmental-specificity of mutational fitness effects in ectothermic organisms. Specifically, we were able to (i) add significantly more studies including temperature, and (ii) include estimates of sampling error variance from each original study, to enable formal meta-analysis of the effects. In total, we retrieved 100 paired estimates comparing selection on de novo mutations across a benign and stressful environment, from 28 studies on 11 organisms spanning viruses and unicellular bacteria and fungi, to multicellular plants and animals (see further details in the electronic supplementary material, S3 with a full summary of studies and selection estimates in table S3.1). The original studies measured effects of mutations accrued by mutation accumulation/mutagenesis, or engineered substitutions/insertions/deletions. Fitness was estimated in the form of relative growth rate, survival or reproduction in mutants and wild-types. Hence, the strength of selection against mutants in each environment (i.e. environment-specific de novo mutation load) could be estimated as: Δωi = 1 − ωi*/ωi, where ωi* and ωi is the fitness in environment i of mutants and wild-type, respectively. An estimate controlling for between-study variation was retrieved by taking the log-ratio of mutation load in the stressful relative to benign environment in each study: loge[Δωstress/Δωbenign], with a log-ratio above (below) 0 indicating stronger (weaker) selection against mutations under environmental stress. We explored any potential publication bias by plotting the precision of each estimated log-ratio (1/standard error) against its mean. This showed no clear evidence for such bias (electronic supplementary material, figure S3.5)

We analysed the log-ratios in a meta-analysis using Bayesian mixed-effects models in the MCMCglmm package [52] for R. Using the Bayesian posterior estimates, we tested if log-ratios differed from 0 for three levels of environmental stress: cold temperature, warm temperature and other types of stress pooled, and for the total effect of stress averaged across all studies. We also tested if log-ratios differed between the three types of abiotic stress. Each estimated log-ratio's contribution to the final meta-analytic result was weighted by its standard error (sampling variance), calculated by the propagation of measurement errors from the original studies. All models included stress-type (cold, hot or other), the type of mutations studied (generated via mutation accumulation, known substitution or insertion/deletion) and fitness measure (relative growth rate, reproduction or survival) as main effects, although effects of the latter two were never significant and dropped from final models. We included study organism crossed with stress-type and study identity as random effects. We also performed an analysis including a fixed factor encoding uni- or multicellularity, which was crossed with stress type, allowing us to test for differences in selection between the two groups. (See the electronic supplementary material, table S3.2 for full specification of priors, models and output.)

3. Results

(a). Enzyme kinetics theory predicts temperature dependence of mutational fitness effects

Selection against mutations affecting enzymatic reaction rate (ΔΔGa) is expected to be independent of the original catalytic rate of the wild-type (ΔGa) and to, on average, remain largely unaffected by any ecologically relevant (i.e. 283–313°K) change in temperature (figure 1a,d; electronic supplementary material, S1.1). Note, however, from equations (2.2–2.4) and figure 1a, how mutations affecting folding (ΔΔGf) and temperature-driven increases in the entropy of folding have synergistic nonlinear effects on protein stability. This synergism causes the mean strength of selection against folding mutations to increase with temperature (figure 1c). This also leads to increased mutational variance in fitness and a larger fraction of both highly deleterious and beneficial mutations (electronic supplementary material, S1.2 and 1.3). The evolution of increased protein thermostability is predicted to produce enzymes that are more robust to mutational perturbation (figure 1a,c), and hence, mutations in proteins with low stability are predicted to contribute disproportionally to temperature-dependent mutational fitness effects (electronic supplementary material, S1.3, see also: [29,30]). If differences in protein stability evolve in response to environmental temperatures, cold- and warm-adapted ecotypes are predicted to experience the same strength of selection on de novo mutations at an environmental temperature standardized relative to the ecotypes' respective thermal optima (figure 1d). We note here, however, that while individual proteins isolated from mesophilic and thermophilic organisms do show evolved differences in stabilities, this pattern seems not to hold for the organismal-wide repertoires of proteins measured in vitro [29,38,53].

Variation in the temperature dependence of mutational effects might be generated by differences in ΔSf, governing the temperature sensitivity of protein stability (i.e. ΔGf(T)) (electronic supplementary material, S1.4, see also [54]). Hence, this could contribute to systematic variability in the temperature dependence of selection across genes or between organisms. Moreover, while the mean mutational effect on the catalytic rate (ΔΔGa) is predicted to be largely independent of temperature (electronic supplementary material, S1.1), ΔΔGa mutations may weaken the overall temperature dependence of mutation load. The extent to which they do depends on their effect size and frequency relative to that of folding mutations (ΔΔGf) (figure 1d).

These predictions arise from two established principles: (i) enzymes show disproportionate unfolding at high temperatures, and (ii) mutations with effect on protein stability are very common and more likely to decrease the fraction of properly folded (functional) protein, than to increase it [33–36,39,40]. The qualitative results are therefore robust to the particular mathematical formulation of the enzyme kinetic model. While we here have focused on the very essential features of protein fitness in terms of the fraction of active enzyme and its catalytic rate, the modelled thermodynamics may encompass a broader scope of temperature-dependent processes leading to reductions in fitness [55], including effects from protein toxicity and aggregation arising from misfolded proteins in the cell [34,56] and RNA misfolding [57]. To illustrate this point, we show in the electronic supplementary material, S1.5 that a model of metabolic flux theory incorporating protein toxicity [33,58] makes the same qualitative predictions as outlined above. This model makes the additional prediction that the temperature dependence should, all else equal, be stronger for more abundant proteins. This is in line with documented greater fitness costs of folding mutations in more expressed genes, which has been postulated as a reason for why such genes evolve more slowly [56,58].

(b). Temperature-dependent fitness effects of mutations in seed beetles adapted to contrasting thermal regimes

There was clear evidence for thermal adaptation across the evolution regimes of seed beetle. Offspring production decreased at 36°C relative to 30°C, but this decrease was less pronounced in warm-adapted lines (electronic supplementary material, table S2.2 and figure S2.1a). Moreover, warm-adapted lines survived slightly better (although marginally non-significant: electronic supplementary material, table S2.1 and figure S2.1b) and developed slightly slower (electronic supplementary material, figure S2.1c) across temperatures (23–38°C), a sign of counter-gradient adaptation [24,26] (i.e. counter to the effect of elevated temperature on phenotype).

Qualitatively consistent with model predictions (compare figures 1c and 2), elevated temperature increased mutation load in both the F1 (PMCMC = 0.002, total n = 713; figure 2a; electronic supplementary material, table S2.2a) and F2 generation (PMCMC = 0.030, total n = 1449; figure 2b; electronic supplementary material, table S2.2b). Despite the observed thermal adaptation, there was no obvious difference in the temperature dependence of mutational fitness effects seen in control and warm-adapted lines (interaction: PMCMC.F1 = 0.38, PMCMC.F2 = 0.99; figure 2), suggesting that high temperature, rather than thermal stress per se, may be the underlying reason for the increase in selection. We note that, while the greater mutational effects seen overall in control relative to warm-adapted lineages also are consistent with model predictions (compare figures 1c and 2), this difference most likely has another explanation (discussed further in the electronic supplementary material, S2 and in [44]).

(c). A meta-analysis of temperature-dependent mutational fitness effects

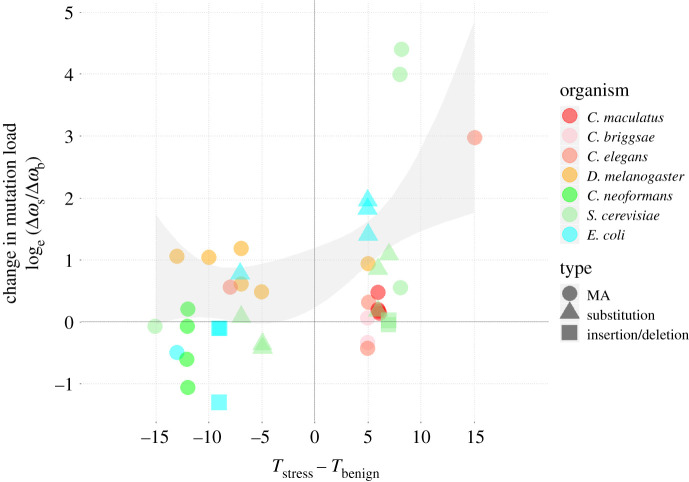

Analysing all collated log-ratios together showed that selection against de novo mutation was not greater under stressful abiotic conditions on average (log-ratio = 0.25, 95% credible interval (CI): −0.03; 0.55, PMCMC = 0.09; figure 3). We continued by analysing the 40 estimates derived at high and low temperature stress separately from the 60 estimates derived from various other stressful environments (summarized in the electronic supplementary material, table S3.1). This revealed that selection on de novo mutation increases at elevated temperature (log-ratio = 1.14, 95% CI: 0.47; 1.67, PMCMC = 0.002, n = 21, studies = 10), whereas there was no increase at low temperature (log-ratio = 0.14, 95% CI: −0.42; 0.81, PMCMC = 0.62, n = 19, studies = 11) or for the other stressors pooled (log-ratio = 0.18, 95% CI: −0.32; 0.66, PMCMC = 0.47, n = 54, removing six estimates where s in each environment approx. 0, studies = 22) (figure 3). Elevated temperature led to a larger increase in selection relative to both cold stress (difference in log-ratios = −1.08, 95% CI: −1.85; −0.25, PMCMC = 0.006) and the other stressors (difference in log-ratios = −1.07, 95% CI: −1.82; −0.44, PMCMC = 0.010) (figure 3; electronic supplementary material, table S3.2a). There was a tendency for cold stress to decrease selection in unicellular species and increase it in multicellular species (interaction: PMCMC = 0.048). However, five of the six estimates at cold stress for multicellular species derive from survival data on Drosophila melanogaster and drive this trend (figure 4; electronic supplementary material, table S3.2b). We found no statistically significant difference in the effect of elevated temperature on selection between the four multicellular and three unicellular species (PMCMC = 0.45) and both multicellular (PMCMC = 0.02) and unicellular (PMCMC < 0.001) species showed significant increases in selection at elevated temperature when analysed separately (i.e. the mean log-ratio was significantly greater than 0 in both cases). Notably, all the 12 log-ratios that were significantly different from 0 (greater than 1.96 s.e.) at elevated temperature were positive, signifying increased selection (two-sided binomial test, p = 0.0005). The 64 paired estimates of mutational variance followed the same general pattern as mutation load (figure 3; electronic supplementary material, table S3.3).

Figure 3.

Meta-analysis of mutational fitness effects in stressful environments. Meta-analysis of the effect of abiotic stress on the mean strength of selection against de novo mutations (filled points) and mutational variance (open triangles) analysed by log-ratios (Bayesian posterior modes ± 95% credible intervals): Δωstress/Δωbenign and ΔVstress/ΔVbenign > 0 correspond to greater mutational fitness effects under environmental stress. Selection is not greater in stressful environments overall and highly variable across the 25 studies analysed (filled circles). However, estimates of Δω at high temperature are greater than their paired estimates at benign temperature. Results were similar when analysing the fewer available estimates of mutational variance (ΔV: open triangles). (Online version in colour.)

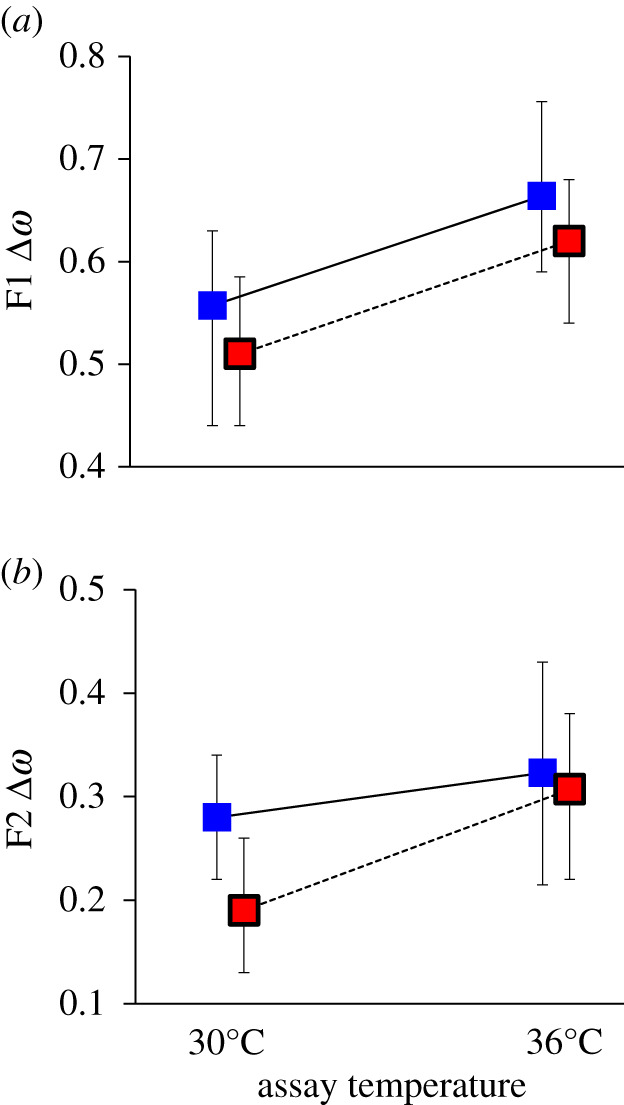

Figure 4.

Meta-analysis of temperature-dependent mutational fitness effects. The strength of selection on de novo mutations as a function of the direction and magnitude of the temperature shifts between the benign and stressful temperature. The seven species and the type of mutations studied are depicted (MA = mutation accumulation resulting in a set of unspecified mutations). Two studies (five estimates) using insertions or deletions (squares) were excluded from formal analysis as effects of these mutations are not captured by the biophysical model. Selection generally increases with temperature whereas stress per se did not affect the strength of selection. The grey-shaded area represents the 95% CI from a second-degree polynomial fit of the log-ratios on temperature, weighted by the statistical significance of each estimate. Points are jittered for illustrative purposes. (Online version in colour.)

Using the 40 log-ratios derived from contrasting temperatures, we partitioned effects on the strength of selection from (i) stress per se; quantified as the reduction in mean fitness at the stressful temperature relative to the benign temperature ), and (ii) that of the temperature shift itself; quantified as the magnitude and direction of the temperature shift: Tstress – Tbenign. Before analysis, we removed five estimates (two studies) based on insertions/deletions (electronic supplementary material, table S3.1), as the applied biophysical model only makes explicit predictions about mutations leading to changes in protein sequences, and not about more severe gene knockout effects likely to follow from insertions or deletions. Four out of these five estimates showed essentially no change in selection with temperature (log-ratio approx. 0, figure 4) and retaining them in the analyses had little effect on model results. The strength of selection was not related to stress (PMCMC = 0.91). However, a shift towards warmer assay temperature per se caused a substantial increase in mutation load (PMCMC < 0.001; figure 4; electronic supplementary material, table S3.2c). There was also a nonlinear effect of temperature (PMCMC = 0.006; figure 4; electronic supplementary material, table S3c). The temperature dependence of selection seemed to differ between the unicellular and multicellular species studied (interaction: PMCMC = 0.018; figure 4; electronic supplementary material, table S3d). However, again, this pattern is driven almost solely by the five estimates from D. melanogaster at cold temperature.

In the electronic supplementary material, S3.4, we show that, in line with model predictions, increases in the average fitness effects of the induced mutations, more so than increases in the number of induced mutations with fitness effects, probably explain the observed increase in Δω at elevated temperature.

4. Discussion

Here we have presented empirical evidence suggesting that elevated temperature increases the mean strength of genome-wide selection and mutational variance in fitness, an observation qualitatively consistent with the applied biophysical model of enzyme kinetics which ascribes these increases to magnified mutational effects on protein folding at elevated temperature. However, the existing data also hint at there being variation between organismal groups in the effect (figure 4). The exact strength of the temperature dependence is also predicted to vary considerably between genes and mutations (figure 1; electronic supplementary material, S1).

It is important to point out that even though there is a qualitative agreement between empirical data and the theoretical predictions, further in-depth studies are needed to prove causality and evaluate model assumptions. While the modelled temperature dependence of protein folding is supported by empirical observation and theory based on first principles, and the common impact of mutation on folding has been empirically verified [33–35], our results do not rule out that other thermodynamic processes that we have not modelled here can generate temperature-dependent mutational fitness effects [24,55]. For example, RNA-folding is predicted to be similarly affected by temperature [57], and one of our analysed studies [59] did indeed find increased selection on mutations in a transfer RNA gene at elevated temperature. Perhaps the strongest simplifying assumption of biophysical models predicting protein evolution (reviewed in: [33,36]) is the proportional relationship between the amount of enzyme product and whole-organism fitness. Model predictions therefore need to be interpreted only in the more qualitative sense. It follows that systematic differences in the strength of the temperature dependence could be explained by the link between fitness and enzymatic rates being more direct in some organismal groups than others. Such a difference could possibly exist between unicellular and multicellular organisms—consistent with the tendency for the strong temperature dependence observed for Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Escherichia coli in the empirical data. The link between fitness and enzyme performance may also be stronger in experimental settings than in nature owing to the presumed reduction in ecological complexity in the former. Experiments linking whole-organism fitness across different ecological settings to reliable estimates of protein performance (e.g. [60]) are needed to explore these questions further.

The observed increase in mutational fitness effects at warm temperature is predicted to influence regional patterns of evolutionary potential. Previous studies have highlighted a range of possible consequences of temperature on the evolutionary potential in tropical versus temperate regions [61,62], including faster generation times [63], higher maximal growth rates [64,65], higher mutation rates [45] and more frequent recombination [66] in the former. Our results imply that also the efficacy of selection on DNA sequences may be greater in the tropics, which together with the aforementioned factors could result in more rapid evolution and diversification, in line with the greater levels of biodiversity in this area [62,67]. However, implications for species persistence under climate change will crucially depend on demographic parameters [9], and given that most mutations are deleterious and act to destabilize proteins, greater purifying selection in tropical areas under climate warming may result in increased genetic loads and extinction rates if evolutionary potential is limited [65,68,69].

The observed temperature dependence builds a scenario in which climate warming may lead to molecular signatures of increased purifying selection and genome-wide convergence in taxa experiencing climate warming. In support of this claim, Sabath et al. [70] showed that growth temperatures across thermophilic bacteria tend to be negatively correlated to the non-synonymous to synonymous nucleotide substitution-rate. Effects could possibly extend to other aspects of genome architecture. For example, Drake [71] showed that two thermophilic microbes have lower mutation rates than their seven mesophilic relatives and suggested that increased fitness consequences of mutation at hot temperature selects for decreased mutation rate. Increased selection in warm climates could also result in increased mutational robustness [16] via mechanisms not explicitly considered by our model, for example via upregulation of chaperones such as heat-shock proteins, known to assist protein folding [24,40].

In contrast with the effect of elevated temperature, environmental stress per se did not influence the strength of selection in any analysis, implying that mutational robustness is not compromised in environments to which organisms are maladapted. This result is in agreement with conclusions from two previous studies [11,20] using a subset of the data we used here, finding no general increase in mutation load in stressful environments. However, Martin & Lenormand [20] did find an increase in mutational variance under stress, a result consistent with their prediction based on Fisher's geometric model of adaptation [3]. As in Martin & Lenormand's [20] version of Fisher's model, environmental tolerance has classically been conceptualized by a stabilizing (quadratic) selection function mapping organismal fitness to an environmental gradient (e.g. [9]). In this framework, phenotypic effects of mutations remain constant across environments, and the increase in variance in fitness under stress is solely ascribed to directional selection becoming stronger as the organism is moved further from its phenotypic optimum. This prediction was not generally upheld in our meta-analysis. One explanation for this might be that experimentally induced changes in ecological variables typically affect selection at only a limited set of genes, and that the studied mutations happen to miss those key loci. This discussion is ultimately related to the genetic basis for environmental adaptation and how environmental effects on the genotype-phenotype map relate to the core assumptions of Fisher's geometric model (such as that of universal pleiotropy).

In contrast with the generally weak effect of environmental stress, both model and data suggest a significant effect of elevated temperature on mutation load and variance in fitness. This result may be explained by two features. First, the applied biophysical model does not assume that phenotypic variance remains constant across thermal environments; mutation and temperature have synergistic effects on protein stability, causing mutational effects on protein (un)folding to increase with temperature. Second, the results imply that a non-trivial fraction of mutations affects protein folding stability. These two features are supported by a number of targeted studies on mutant proteins [33–36,40,60] and collectively suggest that selection has the potential to be temperature dependent at most protein-coding genes. Yet, it remains less clear how these features affect genetic variance and selection at the level of physiological, morphological and life-history phenotypes [17,21,22]. It also remains to be explored how the unveiled temperature dependence interacts with other features expected to influence the distribution of fitness effects of segregating genetic variants, such as thermal niche width, genome size, phenotypic complexity and population size. These questions are central to understanding how temperature-dependent mutational fitness effects will affect regional and taxonomic patterns of genetic diversity and evolutionary potential under climate change.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank J. Liljestrand-Rönn and R. Augusto for help in the laboratory, and B. Rogell, A. Husby and C. Rueffler for input on previous drafts.

Data accessibility

Raw data for seed beetles is available from the Dryad Digital Repository: https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.12jm63xx6 [43]. Meta-analysis data in the electronic supplementary material, S3.

Authors' contributions

D.B. performed the experiments on seed beetles together with J.S. R.J.W. and D.B. performed the modelling, and D.B. and J.B. performed the meta-analysis. D.B. wrote the manuscript with considerable input from R.J.W. All authors commented on manuscript drafts.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was supported by grant nos. 2015-05223 and 2019-05024 from the Swedish Research Council (VR) to D.B.

References

- 1.Kimura M 1968. Evolutionary rate at the molecular level. Nature 217, 624–626. ( 10.1038/217624a0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Orr HA 2005. The probability of parallel evolution. Evolution 59, 216–220. ( 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2005.tb00907.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fisher RA 1930. The genetical theory of natural selection, xiv, 272 p Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haldane JBS 1927. A mathematical theory of natural and artificial selection, part V: selection and mutation. Math. Proc. Camb. Phil. Soc. 23, 838–844. ( 10.1017/S0305004100015644) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Svensson EI, Berger D. 2019. The role of mutation bias in adaptive evolution. Trends Ecol. Evol. 34, 422–434. ( 10.1016/j.tree.2019.01.015) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lande R 1975. The maintenance of genetic variability by mutation in a polygenic character with linked loci. Genet. Res. 26, 221–235. ( 10.1017/S0016672300016037) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turelli M 1984. Heritable genetic variation via mutation-selection balance: Lerch's zeta meets the abdominal bristle. Theor. Popul. Biol. 25, 138–193. ( 10.1016/0040-5809(84)90017-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haldane JBS 1937. The effect of variation of fitness. Am. Nat. 71, 337–349. ( 10.1086/280722) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bürger R, Lynch M. 1995. Evolution and extinction in a changing environment: a quantitative-genetic analysis. Evol. Int. J. Org. Evol. 49, 151–163. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1995.tb05967.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kingsolver JG, Hoekstra HE, Hoekstra JM, Berrigan D, Vignieri SN, Hill CE, Hoang A, Gibert P, Beerli P. 2001. The strength of phenotypic selection in natural populations. Am. Nat. 157, 245 ( 10.1086/319193) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agrawal AF, Whitlock MC. 2010. Environmental duress and epistasis: how does stress affect the strength of selection on new mutations? Trends Ecol. Evol. 25, 450–458. ( 10.1016/j.tree.2010.05.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chevin L-M, Lande R, Mace GM. 2010. Adaptation, plasticity, and extinction in a changing environment: towards a predictive theory. PLoS Biol. 8, e1000357 ( 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000357) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siepielski AM, et al. 2017. Precipitation drives global variation in natural selection. Science 355, 959–962. ( 10.1126/science.aag2773) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Husby A, Visser ME, Kruuk LEB. 2011. Speeding up microevolution: the effects of increasing temperature on selection and genetic variance in a wild bird population. PLoS Biol. 9, e1000585 ( 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000585) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agrawal AF, Whitlock MC. 2012. Mutation load: the fitness of individuals in populations where deleterious alleles are abundant. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 43, 115–135. ( 10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-110411-160257) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Visser JAGM, et al. 2003. Perspective: evolution and detection of genetic robustness. Evolution 57, 1959–1972. ( 10.1554/02-750R) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paaby AB, Rockman MV. 2014. Cryptic genetic variation: evolution's hidden substrate. Nat. Rev. Genet. 15, 247–258. ( 10.1038/nrg3688) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Landry CR, Lemos B, Rifkin SA, Dickinson WJ, Hartl DL. 2007. Genetic properties influencing the evolvability of gene expression. Science 317, 118–121. ( 10.1126/science.1140247) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones AG, Bürger R, Arnold SJ. 2014. Epistasis and natural selection shape the mutational architecture of complex traits. Nat. Commun. 5, 3709 ( 10.1038/ncomms4709) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin G, Lenormand T. 2006. The fitness effect of mutations across environments: a survey in light of fitness landscape models. Evolution 60, 2413–2427. ( 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2006.tb01878.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoffmann AA, Merilä J. 1999. Heritable variation and evolution under favourable and unfavourable conditions. Trends Ecol. Evol. 14, 96–101. ( 10.1016/S0169-5347(99)01595-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rowiński PK, Rogell B. 2017. Environmental stress correlates with increases in both genetic and residual variances: a meta-analysis of animal studies. Evolution 71, 1339–1351. ( 10.1111/evo.13201) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arbuthnott D, Whitlock MC. 2018. Environmental stress does not increase the mean strength of selection. J. Evol. Biol. 31, 1599–1606. ( 10.1111/jeb.13351) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hochachka PW, Somero GN. 2002. Biochemical adaptation: mechanism and process in physiological evolution, 482 p Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown JH, Gillooly JF, Allen AP, Savage VM, West GB. 2004. Toward a metabolic theory of ecology. Ecology 85, 1771–1789. ( 10.1890/03-9000) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Angilletta MJ 2009. Thermal adaptation: a theoretical and empirical synthesis, 304 p Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen P, Shakhnovich EI. 2009. Lethal mutagenesis in viruses and bacteria. Genetics 183, 639–650. ( 10.1534/genetics.109.106492) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen P, Shakhnovich EI. 2010. Thermal adaptation of viruses and bacteria. Biophys. J. 98, 1109–1118. ( 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.11.048) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ghosh K, Dill K. 2010. Cellular proteomes have broad distributions of protein stability. Biophys. J. 99, 3996–4002. ( 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.10.036) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Agozzino L, Dill KA. 2018. Protein evolution speed depends on its stability and abundance and on chaperone concentrations. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 115, 9092–9097. ( 10.1073/pnas.1810194115) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Evans MG, Polanyi M. 1935. Some applications of the transition state method to the calculation of reaction velocities, especially in solution. Trans. Faraday Soc. 31, 875–894. ( 10.1039/tf9353100875) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eyring H 1935. The activated complex in chemical reactions. J. Chem. Phys. 3, 107–115. ( 10.1063/1.1749604) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Echave J, Wilke CO. 2017. Biophysical models of protein evolution: understanding the patterns of evolutionary sequence divergence. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 46, 85–103. ( 10.1146/annurev-biophys-070816-033819) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.DePristo MA, Weinreich DM, Hartl DL. 2005. Missense meanderings in sequence space: a biophysical view of protein evolution. Nat. Rev. Genet. 6, 678–687. ( 10.1038/nrg1672) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tokuriki N, Tawfik DS. 2009. Stability effects of mutations and protein evolvability. Curr. Opin Struct. Biol. 19, 596–604. ( 10.1016/j.sbi.2009.08.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bershtein S, Serohijos AW, Shakhnovich EI. 2017. Bridging the physical scales in evolutionary biology: from protein sequence space to fitness of organisms and populations. Curr. Opin Struct. Biol. 42, 31–40. ( 10.1016/j.sbi.2016.10.013) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eyring H, Polanyi M. 2013. On simple gas reactions. Z Für. Phys. Chem. 227, 1221–1246. ( 10.1524/zpch.2013.9023) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dill KA, Ghosh K, Schmit JD. 2011. Physical limits of cells and proteomes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 108, 17 876–17 882. ( 10.1073/pnas.1114477108) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goldstein RA 2011. The evolution and evolutionary consequences of marginal thermostability in proteins. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinforma. 79, 1396–1407. ( 10.1002/prot.22964) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sikosek T, Chan HS. 2014. Biophysics of protein evolution and evolutionary protein biophysics. J. R. Soc. Interface 11, 20140419 ( 10.1098/rsif.2014.0419) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Drummond DA, Wilke CO. 2008. Mistranslation-induced protein misfolding as a dominant constraint on coding-sequence evolution. Cell 134, 341–352. ( 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.042) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zeldovich KB, Chen P, Shakhnovich EI. 2007. Protein stability imposes limits on organism complexity and speed of molecular evolution. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 104, 16 152–16 157. ( 10.1073/pnas.0705366104) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Berger D, Stångberg J, Baur J, Walters RJ. 2021. Elevated temperature increases genome-wide selection on de novo mutations Dryad Digital Repository. ( 10.5061/dryad.12jm63xx6) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, Walker S. 2014. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. ArXiv14065823 Stat [Internet], [cited 2018 Feb 19]; See http://arxiv.org/abs/1406.5823.

- 45.Berger D, Stångberg J, Grieshop K, Martinossi-Allibert I, Arnqvist G. 2017. Temperature effects on life-history trade-offs, germline maintenance and mutation rate under simulated climate warming. Proc. R. Soc. B 284, 20171721. ( 10.1098/rspb.2017.1721) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grieshop K, Stångberg J, Martinossi-Allibert I, Arnqvist G, Berger D. 2016. Strong sexual selection in males against a mutation load that reduces offspring production in seed beetles. J. Evol. Biol. 29, 1201–1210. ( 10.1111/jeb.12862) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Friedberg EC, Walker GC, Siede W, Wood RD. 2005. DNA repair and mutagenesis, 2nd edn. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology Press. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jo YD, Kim J-B. 2019. Frequency and spectrum of radiation-induced mutations revealed by whole-genome sequencing analyses of plants. Quantum Beam Sci. 3, 7 ( 10.3390/qubs3020007) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tindall KR, Stein J, Hutchinson F. 1988. Changes in DNA base sequence induced by Gamma-ray mutagenesis of lambda phage and prophage. Genetics 118, 551–560. ( 10.1093/genetics/118.4.551) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shabalina SA, Yampolsky LY, Kondrashov AS. 1997. Rapid decline of fitness in panmictic populations of Drosophila melanogaster maintained under relaxed natural selection. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 94, 13 034–13 039. ( 10.1073/pnas.94.24.13034) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Daly MJ 2012. Death by protein damage in irradiated cells. DNA Repair 11, 12–21. ( 10.1016/j.dnarep.2011.10.024) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hadfield JD 2010. MCMC methods for multi-response generalized linear mixed models: the MCMCglmm R package. J. Stat. Softw. 33, 1–22. ( 10.18637/jss.v033.i02)20808728 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Leuenberger P, Ganscha S, Kahraman A, Cappelletti V, Boersema PJ, von Mering C, Claassen M, Picotti P. 2017. Cell-wide analysis of protein thermal unfolding reveals determinants of thermostability. Science 355, eaai7825 ( 10.1126/science.aai7825) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sawle L, Ghosh K. 2011. How do thermophilic proteins and proteomes withstand high temperature? Biophys. J. 101, 217–227. ( 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.05.059) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Puurtinen M, Elo M, Jalasvuori M, Kahilainen A, Ketola T, Kotiaho JS, Mönkkönen M, Pentikäinen OT. 2016. Temperature-dependent mutational robustness can explain faster molecular evolution at warm temperatures, affecting speciation rate and global patterns of species diversity. Ecography 39, 1025–1033. ( 10.1111/ecog.01948) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Drummond DA, Bloom JD, Adami C, Wilke CO, Arnold FH. 2005. Why highly expressed proteins evolve slowly. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 102, 14 338–14 343. ( 10.1073/pnas.0504070102) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang J, Yang J-R. 2015. Determinants of the rate of protein sequence evolution. Nat. Rev. Genet. 16, 409–420. ( 10.1038/nrg3950) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Serohijos AWR, Rimas Z, Shakhnovich EI. 2012. Protein biophysics explains why highly abundant proteins evolve slowly. Cell Rep. 2, 249–256. ( 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.06.022) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li C, Zhang J. 2018. Multi-environment fitness landscapes of a tRNA gene. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1, 1025–1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dandage R, Pandey R, Jayaraj G, Rai M, Berger D, Chakraborty K. 2018. Differential strengths of molecular determinants guide environment specific mutational fates. PLoS Genet. 14, e1007419 ( 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007419) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mayhew PJ, Bell MA, Benton TG, McGowan AJ. 2012. Biodiversity tracks temperature over time. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 109, 15 141–15 145. ( 10.1073/pnas.1200844109) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tittensor DP, Mora C, Jetz W, Lotze HK, Ricard D, Berghe EV, Worm B. 2010. Global patterns and predictors of marine biodiversity across taxa. Nature 466, 1098–1101. ( 10.1038/nature09329) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gillooly JF, Charnov EL, West GB, Savage VM, Brown JH. 2002. Effects of size and temperature on developmental time. Nature 417, 70–73. ( 10.1038/417070a) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Frazier MR, Huey RB, Berrigan D. 2006. Thermodynamics constrains the evolution of insect population growth rates: ‘Warmer Is Better’. Am. Nat. 168, 512–520. ( 10.1086/506977) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Walters RJ, Blanckenhorn WU, Berger D. 2012. Forecasting extinction risk of ectotherms under climate warming: an evolutionary perspective. Funct. Ecol. 26, 1324–1338. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2012.02045.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lloyd A, Morgan C, Franklin FCH, Bomblies K. 2018. Plasticity of meiotic recombination rates in response to temperature in arabidopsis. Genetics 208, 1409–1420. ( 10.1534/genetics.117.300588) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jablonski D, Roy K, Valentine JW. 2006. Out of the tropics: evolutionary dynamics of the latitudinal diversity gradient. Science 314, 102–106. ( 10.1126/science.1130880) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hoffmann AA, Sgrò CM. 2011. Climate change and evolutionary adaptation. Nature 470, 479–485. ( 10.1038/nature09670) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kellermann V, van Heerwaarden B, Sgrò CM, Hoffmann AA. 2009. Fundamental evolutionary limits in ecological traits drive Drosophila species distributions. Science 325, 1244–1246. ( 10.1126/science.1175443) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sabath N, Ferrada E, Barve A, Wagner A. 2013. Growth temperature and genome size in bacteria are negatively correlated, suggesting genomic streamlining during thermal adaptation. Genome Biol. Evol. 5, 966–977. ( 10.1093/gbe/evt050) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Drake JW 2009. Avoiding dangerous missense: thermophiles display especially low mutation rates. PLoS Genet. 5, e1000520 ( 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000520) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Berger D, Stångberg J, Baur J, Walters RJ. 2021. Elevated temperature increases genome-wide selection on de novo mutations Dryad Digital Repository. ( 10.5061/dryad.12jm63xx6) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Raw data for seed beetles is available from the Dryad Digital Repository: https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.12jm63xx6 [43]. Meta-analysis data in the electronic supplementary material, S3.