Abstract

Background:

The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends that clinicians provide or refer pregnant and postpartum women who are at increased risk of perinatal depression to counseling interventions. However, this prevention goal requires effective interventions that reach women at risk for, but prior to, the development of a depressive disorder.

Objectives:

We describe a pilot efficacy trial of a novel dyadic intervention to prevent common Maternal Mental Health Disorders (MMHDs), Practical Resources for Effective Postpartum Parenting (PREPP), in a sample of women at risk for MMHDs based on poverty status. We hypothesized that PREPP compared to enhanced treatment as usual (ETAU) would reduce MMHD symptoms after birth.

Study Design:

Sixty pregnant women recruited from obstetric practices at Columbia University Medical Center were randomized to the PREPP (n=30) or ETAU (n=30) intervention. The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale, and Patient Health Questionnaire were used to compare maternal mood at 6 weeks, 10 weeks, and 16 weeks postpartum.

Results:

At 6 weeks postpartum, women randomized to PREPP had lower mean Edinburgh Postnatal Depression scores (p=.018), lower mean Hamilton Depression scores (p<.001), and lower mean Hamilton Anxiety scores (p=.041), however incidence of postpartum mental disorders did not differ by treatment group.

Conclusion:

PREPP, an intervention integrated within obstetric care, improves sub-clinical symptomology for at-risk dyads at a crucial time in the early postpartum period, yet our study did not detect reductions in incidence of post-partum mental disorders.

Keywords: Maternal Mental Health Disorders, prevention, postpartum depression

Condensation

A brief, dyadic-focused, perinatal psychotherapy intervention, Practical Resources for Effective Postpartum Parenting (PREPP), reduced sub-clinical depression and anxiety symptoms at 6-weeks postpartum in low-income urban women.

INTRODUCTION

The clinical approach to common perinatal mood and anxiety disorders— preferrably termed Maternal Mental Health Disorders (MMHDs)1 — is shifting from the need to treat to the imperative to prevent. MMHDs are among the most common complications of pregnancy and the postpartum period, affecting 1 in 7 women, and it is well established that they can result in adverse short- and long-term effects on both the woman and child. Negative effects even persist beyond the offspring’s lifecourse, with intergenerational effects clearly demonstrated.2 The national economic costs of not treating these disorders from conception to the first postpartum year is estimated at $7.5 billion.3 The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recently published a systemmatic review of primary care-relevant interventions to prevent perinatal depression, defined as a major or minor depressive episode during pregnancy or up to 1 year after childbirth,4 and recommended that “clinicians provide or refer pregnant and postpartum persons who are at increased risk of perinatal depression to counseling interventions.5”

This prevention goal requires effective interventions that reach women at risk for, but prior to, the development of a depressive disorder. One intervention that was included in the USPSTF systematic review is a novel dyadic prevention intervention, Practical Resources for Effective Postpartum Parenting (PREPP). A previous randomized control trial of PREPP in a sample of 54 pregnant women with sub-threshold symptoms of depression showed that PREPP was associated with a significant reduction in depression and anxiety symptoms at 6 weeks postpartum6.

Rates of depression are higher for those living in poverty, with almost 50% of low-income mothers of infants and young children having depression.7 Women who live in poverty often have a combination of low maternal education, young maternal age at childbirth, single parenthood, minority group status, substance use, increased stressful life situtations, and challenges accessing mental health care, all leading to higher risk of MMHDs, as well as poor developmental outcomes in offspring.8,9 In this second trial of PREPP, reported here, we asked whether PREPP reduces MMHD symptoms in a sample of women living in poverty and subsequently at high risk for MMHDs given the psychosocial context of their lives.

A key challenge of the USPSTF-recommended prevention strategy is access to mental health care, specifically to prevention interventions. Distressed and burdened pregnant women in particular face logistical hurdles and time constraints related to attending an additional specialty health care appointment at another location. Stigma presents anther barrier for some women to seek and accept mental health care. Co-located and collaborative care models, many oriented to embedding mental health care within obstetric (OB) practices, are innovative approaches to addressing these challenges, though to date the focus of these models is on treatment versus prevention.10,11 For this trial of PREPP, intervention sessions were provided in-person and adjunctive to women’s standard OB care.

Typically, specialized services for mothers and newborns are in separate hospitals. Independent foci on the mother or child overlooks the two-generation orientation of the perinatal period and the importance of maternal–infant interactions to maternal well–being.12–15 Several interventions used to treat MMHDs include the bi-directional feedback between maternal mood and fetal/infant behavior: The Nurse Family Partnership (NFP),16 Circle of Security (COS),17,18 and Minding the Baby (MTB)19,20 have shown positive parenting and life course outcomes. However, each is lengthy and demanding, none is integrated into existing OB services, and none specifically targets prevention of MMHDs. Of the few existing MMHD prevention interventions and services for at-risk women in the perinatal period, none incorporate the exceptionally close associations between mother and infant functioning and behavior nor leverage this dyadic, mother-infant orientation to engage women in care. In our view, a dyadic approach conceptualizes maternal depression as a potential disorder of the mother-infant dyad, such that change in one member affects the other — for example, increased ease with parenting strategies leading to better infant sleep and improved maternal sleep.

PREPP enrolls pregnant women at risk for MMHDs late in pregnancy, is integrated within obstetric visits, and considers the mother-fetus/infant as a dyad. The intervention provides psychoeducation, mindfulness and self-reflection skills, and parenting skills. Here we report a pilot efficacy trial of PREPP in a sample of 60 pregnant women living in poverty (Clinicaltrials.gov:NCT02121496). We hypothesized that PREPP would significantly reduce symptoms of MMHDs after birth and would reduce the incidence of Postpartum Depression (PPD) as compared with Enhanced Treatment as Usual (ETAU).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Procedures.

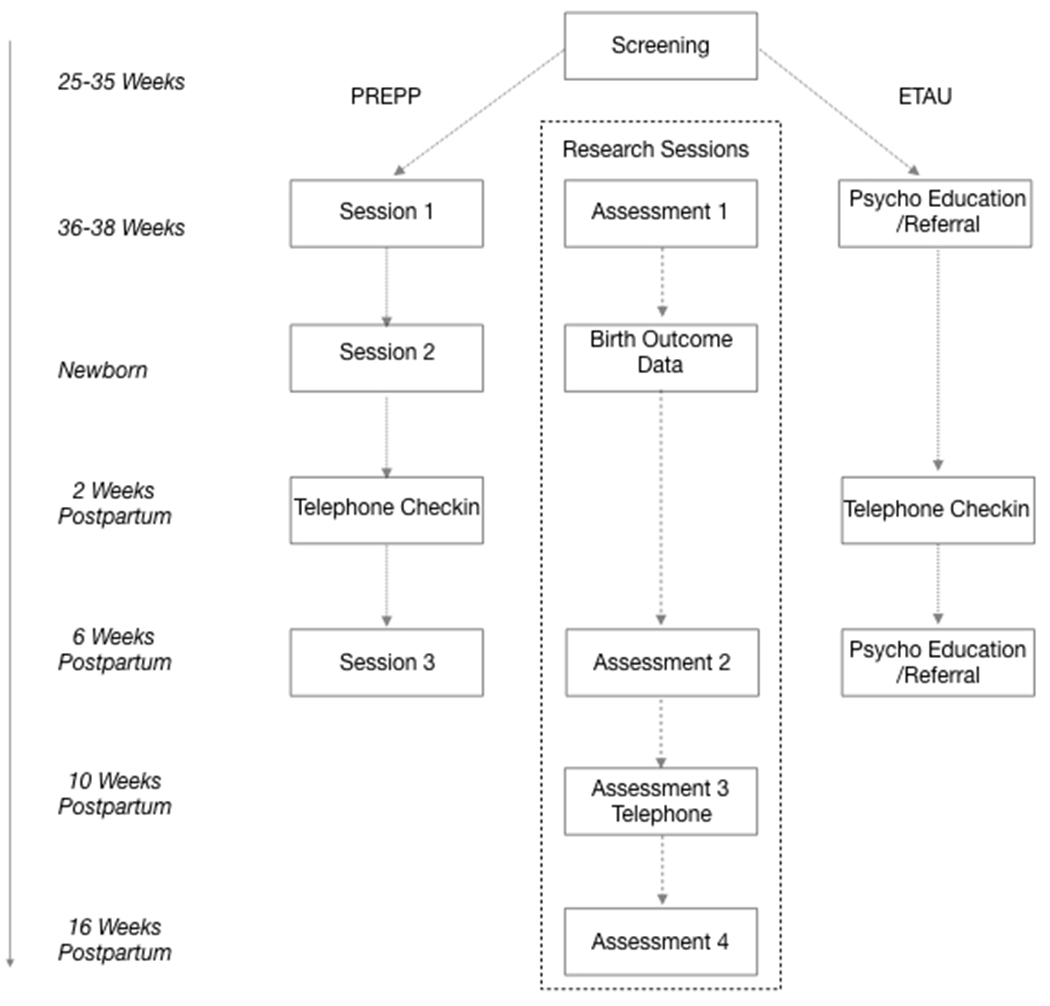

Women were recruited and screened for eligibility for this randomized controlled trial by telephone between 20-28 weeks gestational weeks. Between 34-38 weeks, eligible participants came to a research area in the hospital to provide informed consent and complete mood assessments by self-report and interviewer administration (Assessment 1). Once enrolled, participants also met with the clinical psychologist who informed them of their treatment group assignment as dictated by a computer-generated random assignment schedule. Participants who were assigned to the PREPP group received their first session of PREPP, while those in the ETAU group were given information about PPD, a brief clinical mood assessment, and a referral for treatment if requested by the participant or deemed appropriate by clinical evaluation. Between 18 and 36 hours after giving birth, all participants were visited by a research assistant who collected medical information about their delivery. Those in the PREPP intervention received their second treatment session with the psychologist. At two weeks postpartum, participants in the PREPP group received a check–in telephone call from the psychologist with whom they had been working encouraging use of PREPP skills through motivational interviewing. Those in the ETAU group received a brief check–in call from the research assistant. At six weeks postpartum, all participants returned to the research area in the hospital to complete mood assessments (Assessment 2). Women in the PREPP group received their final PREPP session at this time while those in ETAU were again given information about PPD and were clinically assessed and referred to treatment when appropriate. At 10 weeks postpartum, participants were contacted by telephone and completed mood assessments via telephone (Assessment 3). At 16 weeks postpartum, mood assessments were again administered in person in the research area within the hospital (Assessment 4). Figure 1 provides a schedule of participants’ PREPP intervention sessions, ETAU sessions, and Research Assessment sessions.

Figure 1.

PREPP, ETAU, and Research Sessions

Recruitment.

Participants were drawn from the OB practice at the Audubon clinic, part of the Ambulatory Care Network of the New-York Presbyterian Hospital, part of the Columbia University Irving Medical Center, and other affiliated OB practices. Potential participants were screened by telephone between 20-28 gestational weeks. The screening process was explained to them and oral consent to answer screening questions was documented. Eligible subjects were invited to a face-to-face interview between 28-32 gestational weeks during which they provided informed written consent and completed self-report questionnaires and interviews. Those meeting inclusion/exclusion criteria were randomized into the 3-session trial. Ethical approval for this study was provided by the New York State Psychiatric Institute Institutional Review Board.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria were: 18-45 years old, a healthy, singleton pregnancy, receipt of standard prenatal care, English speaking, and living in poverty as defined by (1) salary indicated to be “Near poor, struggling” (200% of national poverty levels) — ≤ $47,700 annual for a family of 4, based on self-report, — or (2) having met income criteria for Medicaid. Exclusion criteria were: multi-fetal pregnancy, pregnancy or birth complications including any infant NICU admission, giving birth prior to 37 weeks, smoking or alcohol or illicit drug use during pregnancy, and receiving psychological/psychiatric care, including psychopharmacology. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview, a brief structured clinical interview,21 was used to screen out significant comorbidity during the initial in-person screening (meeting criteria for major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, suicidal intent, substance use, psychosis).

Treatment Conditions: PREPP and ETAU.

PREPP intervention:

PREPP enrolls pregnant women at risk for MMHDs and consists of 3 sessions carried out within OB prenatal and postnatal appointments by a Ph.D.-level study psychologist called a ‘coach’. The sessions’ content is described below:

Mindfulness and self-reflection skills (sessions 1-3).

Two mindfulness-based tools aim to (1) aid women in returning to sleep after waking at night, and (2) help them to cope better when their babies are distressed or inconsolable. Specifically, adapted from Dimidjian,22–24 we provide iPod Touches with recordings of Progressive Muscle Relaxation and other mindfulness exercises as well as instructing participants in taking a mindful walk, using all of one’s senses for observation. PREPP uses supportive psychological interviewing to explore women’s past and current social relationships and consider how these impact the woman’s thoughts and reactions to the fetus and baby. In this way, the intervention harnesses the mother-fetus/infant dyadic orientation of the childbearing period, facilitating the capacity to reflect on one’s own and other’s states, which has been associated with more sensitive caregiving.19,25

Parenting skills (sessions 1-3).

Following Pinilla and Birch, as well as Barr, coaches teach and engage women in using five specific infant behavioral techniques to reduce infant fuss/cry behavior and promote sleep:26,27 (1) ‘focal feeds,’ (2) accentuating differences between day and night, (3) lengthening latency to middle of the night feeding time, (4) carrying infants for at least 3 hours a day, and (5) learning to swaddle the baby.27–30 In session two, participants practice the caregiving techniques with a life-size doll and receive a carrier and swaddling blanket to use with their babies.

Psycho-education (sessions 1-3).

Coaches review childbearing hormone level changes, Baby Blues, and infant cry patterns. This knowledge is meant to inform realistic expectations and focus on fostering positive infant attributions and caregiving sensitivity.

To increase accessibility for patients, the three in-person sessions are scheduled to coincide with standard medical visits: (1) 34-38 weeks (3rd trimester ultrasound), (2) in the hospital post-delivery (delivery), and (3) 6 weeks postpartum (6-Week Well Baby visit). The psychologist also contacts participants by telephone at 2 weeks postpartum and, using motivational interviewing techniques, encouraged the use of PREPP skills and answered specific participant questions. Table 1 summarizes the sessions’ content, and more details are included in the PREPP manual available from the authors upon request.

Table 1.

PREPP Session Overview

| PREPP Sessions | Components |

|---|---|

|

Session #1 34-38 weeks’ gestation (In person in clinic) 60 minutes |

•Establish alliance •Self-reflection practice in context of learning about patient’s unique history and life circumstances •Sleep skills, Mindfulness •Psychoeducation •Infant carrying techniques (use infant doll to practice swaddling and carrying) •Distribute materials: PREPP pamphlet, iPod Touch with Mindfulness audio files, infant carrier, swaddling blanket |

|

Session #2 18-36 hours post-delivery (In person in hospital) 30 minutes |

•Review PREPP pamphlet •Practice relevant techniques/skills: ○Swaddling ○Carrying ○Mindfulness |

|

Motivational Interviewing 2 weeks’ postpartum (On the phone) 15-30 minutes |

•Inquire about mother and infant well-being and maternal mood •Assess use of specific skills •Discuss challenges of caring for newborn |

|

Session #3 6 weeks’ postpartum (In person at clinic) 60 minutes |

•Practice self-reflection through inquiry about maternal mood and mother and baby well-being •Assess use of skills •Review of skills where necessary |

Control condition: Enhanced Treatment as Usual (ETAU):

ETAU participants meet with the research personnel three times (aligned with PREPP sessions 1, 2 and 3), receiving ‘usual care’ with enhanced support for finding treatment. At the first contact, lasting 30 minutes, they are given information about PPD, a brief clinical assessment, and a referral for treatment if requested or deemed necessary by the psychologist. At two weeks postpartum they receive a 10-15 minute check-in call during which they receive a refresher in the psychoeducation they receive about postpartum depression, and at 6 weeks postpartum, another 30 minute in-person meeting during which they again are given information about PPD and referred to treatment when appropriate. Out of the 30 women in ETAU, three were referred for mental health treatment. None of these three took up treatment, although one of the three engaged in three treatment sessions with a psychologist she had seen previously.

Outcome Measures.

Women’s depression levels were evaluated at enrollment in the study and at 6 weeks, 10 weeks, and 16 weeks postpartum using the interviewer-administered Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD),31 self-report Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS),32 and Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9).33 Anxiety symptoms were evaluated at the same timepoints using the Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety (HRSA)34 given that some data, though not all,35 suggest that postpartum depression is characterized by significant anxiety.36,37 Each depression scale has strengths and weaknesses relevant to the study aims and is reliable for prenatal/postpartum research,38 and the four scales have been used together in previous research.6,39,40 The HRSD provides observer ratings; in some studies the self-report EPDS has demonstrated greater reliability than the PHQ-9 for postpartum women,41–43 while the PHQ-9 has robust evidence for use in primary care settings.42 The following cutoffs were used to test PPD outcomes, which have been used in previous research as cutoffs for depression diagnosis:38 EPDS: 9 (A cutoff value found to be optimal among low-income, urban women):44 HRSD: 7;38 HRSA: 14;45,46 PHQ-9: 10.41,43

Analyses.

Data were analyzed on an intention to treat basis. Generalized Estimating Equations with poisson distribution were used for continuous outcomes. For dichotomous outcomes, Glimmix logistic models were used. For all models, multiple imputation was used to account for missing data. SAS version 9.4 was used for all analyses.

RESULTS

Screening and Eligibility.

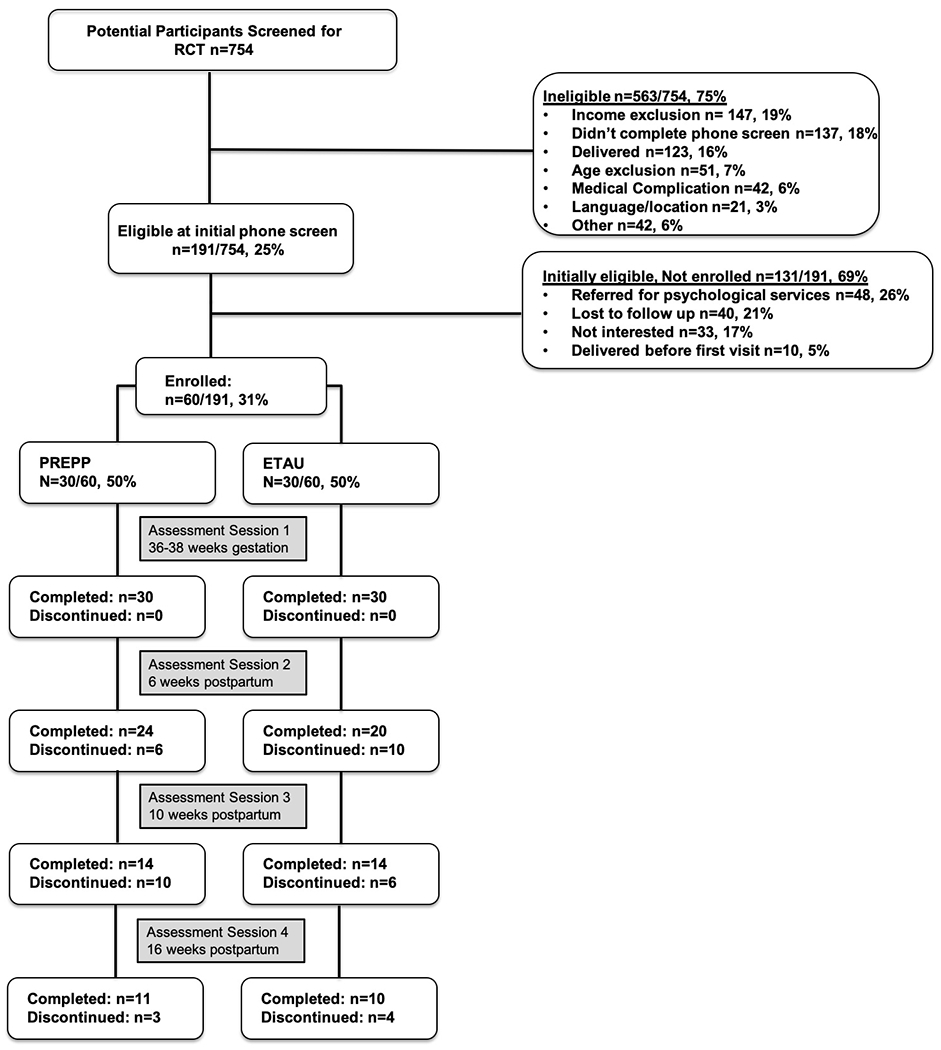

Of the 754 women who were screened for the study between July 2016 and February 2018, 60 were enrolled, approximately 8% (see Figure 2). Nearly 75% (n=563) of women screened over the phone for the intervention were not eligible for the study. The majority of these either did not meet the study’s income criteria (n=147, 19%), did not complete the phone screen (n=137, 18%), or had delivered their child prior to being screened for the study (n=123, 16%). Additionally n=51, 7% were ineligible because they did not meet the age criterion, n= 42, 6% were excluded due to medical complications, n=21, 3% were either out of the study area or didn’t speak English. Of the 191 women who were eligible after the phone screen and came in for an in-person screening, 131 (69%) were not ultimately enrolled. Of the 191 eligible, 48 (26%) were referred for more intensive psychological/psychiatric services— 8 women due to meeting MINI criteria for Major Depressive Disorder, and 40 women because of self-reporting psychiatric diagnoses or significant stress in pregnancy, 40 were lost to follow up (21%), 33 were not interested in participating in the intervention (17%), and 10 additional women delivered their babies before the first study visit (5%). The 60 enrolled participants were randomized to either the PREPP intervention or the ETAU groups.

Figure 2.

CONSORT Diagram for Research Study

Intervention Adherence.

Eighty-three percent (83% 25 out of 30) of participants randomized to PREPP completed the entire treatment protocol. All participants (100%) underwent the first two sessions— the prenatal session and the session immediately after delivery. Of those 5 who did not complete the intervention protocol, two women could not be reached for the 2-week postnatal phone check in, and three additional participants did not return to the clinic for the final PREPP session 6 weeks after birth.

Research Session Attrition.

All participants in the intervention and control groups completed the prenatal and newborn postnatal research assessments. Of the 60 women randomized to PREPP or ETAU, sixteen women (26.6%) did not complete the 6-week postnatal assessment (6 randomized to PREPP and 10 ETAU). At 10 weeks postpartum, 32 participants (53.3%) did not complete assessments (16 randomized to PREPP and 16 to ETAU). At 16 weeks postpartum 39 participants (65%) did not complete assessments (19 randomized to PREPP and 20 to ETAU). Women who were lost to follow-up did not differ significantly on key demographic variables or symptom severity at screening (Table 1 in supplementary materials). The CONSORT diagram of screening, enrollment, and research attrition is presented in Figure 2.

Demographics and Baseline Mood Measures.

Participants were 84% Hispanic/Latina, mean 28 years of age, and 40% primiparous. Those randomized to PREPP or ETAU did not differ on any baseline demographic factors or mood measures (Table 2). Overall depression symptom levels at baseline were relatively low (e.g., average 4.8 on the EPDS).

Table 2.

Demographic information by treatment condition: PREPP intervention or Enhanced Treatment as Usual (ETAU) (n=60)

| Treatment | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Sample | PREPP | ETAU | Diff between groups | ||||

| (n=60) | (n=30) | (n=30) | |||||

| Variables | n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | p-valuea |

| or % | or % | or % | |||||

| Demographics | |||||||

| Number of children | 0.55 | ||||||

| = 0 | 23 | 40.40% | 12 | 44.40% | 11 | 36.70% | |

| > 0 | 34 | 59.60% | 15 | 55.60% | 19 | 63.30% | |

| Age | 57 | 28.2 (5.9) | 27 | 27.4 (5.7) | 30 | 28.9 (6.1) | 0.374 |

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.358 | ||||||

| Hispanic / Latina | 48 | 84.20% | 24 | 88.90% | 24 | 80.00% | |

| Not Hispanic / Latina | 9 | 15.80% | 3 | 11.10% | 6 | 20.00% | |

| Baby sex | 0.781 | ||||||

| Male | 25 | 48.10% | 13 | 50.00% | 12 | 46.20% | |

| Female | 27 | 51.90% | 13 | 50.00% | 14 | 53.80% | |

| Baseline symptom scores | |||||||

| EPDS | 54 | 4.8 (3.6) | 27 | 4.5 (3.7) | 27 | 5.2 (3.6) | 0.418 |

| HRSD | 59 | 5.6 (4.5) | 30 | 5 (3.9) | 29 | 6.2 (5) | 0.28 |

| HRSA | 59 | 5.3 (3.8) | 30 | 4.6 (3.7) | 29 | 6.1 (3.9) | 0.134 |

| PHQ-9 | 53 | 4.8 (3.7) | 27 | 4.6 (3.8) | 26 | 5 (3.6) | 0.664 |

| Baseline disorders | |||||||

| EPDS | 1 | ||||||

| >= 9 | 9 | 16.70% | 5 | 18.50% | 4 | 14.80% | |

| HRSD | 0.792 | ||||||

| >= 7 | 23 | 39.00% | 11 | 36.70% | 12 | 41.40% | |

| HRSA | 0.612 | ||||||

| >= 14 | 3 | 5.10% | 1 | 3.30% | 2 | 6.90% | |

| PHQ-9 | 0.669 | ||||||

| >= 10 | 6 | 11.30% | 4 | 14.80% | 2 | 7.70% | |

Baseline differences are assessed using Wilcoxon for continuous measures and Fisher’s Exact test for categorical measures

Treatment Effects: Prevalence of Clinically Significant Postpartum Depression And Anxiety Symptoms.

Across the whole sample, 16.7% of women were depressed at baseline, 6.8% of women were depressed at 6 weeks postpartum, and 10.5% were depressed at 16 weeks postpartum based on the EPDS cutoff of 9.44 The percentage of women classified as evidincing depressive symptoms at 6 weeks postpartum was lower in the group randomized to PREPP versus ETAU at 6 weeks postpartum (4.2% vs 10.0%), 10 weeks (0% vs 13.3%), and 16 weeks (9.1% vs 12.5%), though these differences were not statistically significant. For the HRSD the pattern showed some similarity at 6 weeks though not at later time points: 8.3% vs 20.0% at 6 weeks, 28.6% vs 21% at 10 weeks, and 18.2% vs 10.0% at 16 weeks based on a score of 7.38 Again, these results were not statistically significant. On the PHQ-9 (cutoff 10)41,43 the results were as follows with no statistically significant differences: 0% in both groups at 6 weeks, 0% in PREPP vs 6.7% in ETAU at 10 weeks, and 10.0% vs 0% at 16 weeks. Percentage of women meeting cutoff for anxiety on the HRSA (based on a cutoff score of 14)45,46 did not differ significantly between PREPP and ETAU: 2.3% vs 4.8% at 6 weeks, 3.4% vs 3.2% at 10 weeks, and 4.4% vs 4.0% at 16 weeks.

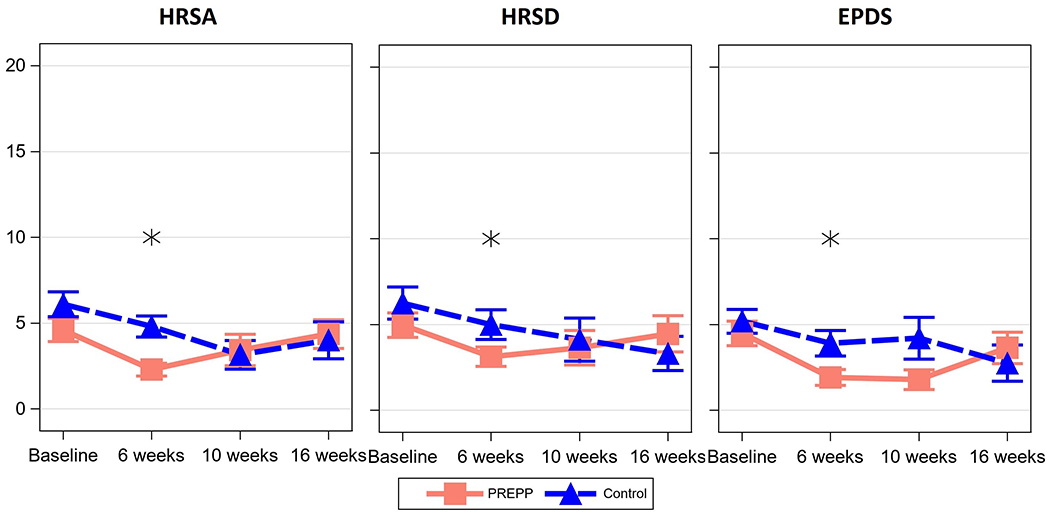

Treatment Effects: Change in Maternal Mood

Depression and anxiety symptoms were relatively low across the whole sample at baseline (average EPDS score 4.8, HRSA score 5.3, PHQ-9 score 4.8, and HRSD score 5.6), 6 weeks (average EPDS score 2.8, HRSA score 3.4, PHQ-9 score 2.9, and HRSD score 4.0), 10 weeks postpartum (average EPDS score 3.0, HRSA score 3.3, PHQ-9 score 2.6, and HRSD score 3.9) and 16 weeks postpartum (average EPDS score 3.3, HRSA score 4.2, PHQ-9 score 2.9, and HRSD score 3.9).

At six weeks postpartum, women randomized to PREPP as compared to those randomized to ETAU had lower mean EPDS score (1.9 vs 3.9, p=.018), lower mean HRSD scores (3.0 vs 5.0, p< .001), and lower mean HRSA score (2.3 vs 4.8, p=.041). These differences did not remain significant at later time points. Differences between treatment groups on the PHQ-9 and HRSD were not significant. Results are presented without adjusting for relevant covariates— maternal age, infant sex, and baseline EPDS score— becaues these factors did not differ between groups, as presented in Table 2.

COMMENT

Principal Findings:

Consistent with prior results of PREPP6— a novel, dyadic approach to preventing MMHDs delivered within OB clinical care— this study found that PREPP reduced postnatal depressive and anxiety symptoms at 6 weeks postpartum in a sample of women at risk for PPD based on poverty status. Similar to the previous trial of PREPP, we did not see symptom reductions at later postpartum time points. Because this was a small pilot study with participant attrition for research sessions greater once the intervention ended, our analyses may have been underpowered to detect effects over time. Alternatively, a central component of PREPP, parenting tools that enhance maternal confidence and potentially facilitate infant regulation and thereby maternal well-being as well, may need to be augmented to include tools geared towards parenting older infants.

Results in the context of what is known:

The USPSTF recommends providing or referring pregnant women who are at increased risk of perinatal depression to counseling interventions. However, few evidence-based interventions for preventing, rather than treating, perinatal MMHD exist. In addition, criteria for which women should be considered at increased risk for perinatal mental disorders, and which interventions are effective for preventing MMHDs in at-risk groups, has not been demonstrated. This is the second small pilot study showing that PREPP is associated with modest reductions in sub-clinical anxiety and depression symptoms in women at risk for postpartum mental health disorders. Neither study found effects at timepoints later than 6 weeks postpartum, although larger sample sizes could provide more power to detect such effects.

Clinical implications:

The psychiatric Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) 47 specifies that the symptoms of PPD must first occur within the first 4 weeks postpartum; our findings indicate that PREPP is a useful tool to reduce depression symptoms consistent with the clinical focus on this early postpartum time period for mothers, as well as their infants.

The 17% attrition rate for the PREPP clinical intervention falls at the lower end of the 6% to 70% range of attrition rates reported in a meta-analysis of interventions for treating postpartum depression in primary care.48 (Attrition for the research assessment sessions in both the PREPP and ETAU groups was greater, as displayed in the CONSORT diagram in Figure 2). The context of PREPP within OB care, as well as the brief format, and its focus on the mother-baby unit — so salient in this life phase — likely account for its success in engaging and maintaining pregnant and postpartum women in treatment. While this study used a psychologist to deliver PREPP, clinical work in Women’s Mental Health @Ob/Gyn — an embedded service within the department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Columbia University —suggests that the intervention can be easily incorporated into an obstetric practice without a psychologist present. Authors Werner and Monk have successfully trained social workers and psychiatric nurse practitioners to deliver PREPP and are currently in the process of training community mental health workers to provide PREPP in OB community clinics

Research implications:

The varying results related to which mood measure was used are consistent with other reports in the literature showing significance of identified symptoms can range based on measures used, the timing of the measurement, and the population in which the measure is used.44,49–51 More research is needed to identify which tool has greatest specificity and sensitivity in identifying clinically relevant mood systems in disadvantaged pregnant women.

Overall, participants had very low levels of depression and anxiety in contrast to other studies with low-income women indicating that they have up to 11 times the risk of having clinically elevated depression symptoms postpartum.52 The inclusion and exclusion criteria for this randomized control trial aimed at women living in poverty may have resulted in a very specific sample of women being included, as evidenced in the nearly three quarters of women who were screened being deemed ineligible to participate. Specifically, women with medical complications, women younger than 18 years of age, women who didn’t speak English, and women who required more intensive psychological care were excluded. Additionally, those eligible but choosing not to participate may have been those with the most logistical or psychological challenges. Therefore, potentially only the most resilient and with fewest problems, may have met inclusion criteria and successfully enrolled in the study. Excluding from clinical trials those with additional conditions beyond the study focus is a common problem, one that contributed to the establishment of the US National Institutes of Health’s Collaboratory on Pragmatic Clinical Trials. There is a growing concern that the results obtained from clinical research may not apply to “real world” clinical situations and is inadequate to inform clinical service decisions.53 In contrast, pragmatic clinical trials aim to enroll a sample representative of the patient population and in a clinical setting relevant to the patients in need of care.54

Strengths and limitations:

This study’s findings should be considered in light of its limitations. The small sample size increases the possibility of both type I and type II errors. The low baseline levels of MMHD symptoms and the large percentage of women ineligible for the study also may challenge the generalizability of the findings, as does the predominance of Latina women, although the previous trial of PREPP yielded similar results with a different sample.6 In light of the null findings in terms of depression incidence, the brief format of PREPP could be considered a limitation, particularly for depression onset beyond the early postpartum period. However, we consider the accessibility of PREPP as a major strength; its brief format and co-location in obstetric care increase its potential to be implemented widely. We believe that the most significant limitation to the study was the stringent inclusion/exclusion criteria, implemented in part in order to make it a more uniform sample and in part because of ethical considerations (e.g. age). These restrictions, as well as the loss-to-follow-up for the research assessments, limited the sample size and power to detect effects at later time points. It is plausible to think that PREPP could contribute to reducing incidence of PPD at later time points if early sources of stress were removed and positive patterns of dyadic interaction were established in the early postpartum period. A more pragmatic trial approach with limited exclusion criteria might help us answer that question. Additionally, providing better incentives for participation or allowing participants to complete assessments remotely could have increased the sample size at later time points. Still, this study is unique in testing the efficacy of a prevention intervention for perinatal MMHD in at risk women, here based on poverty status.

Conclusions:

There is increasingly strong evidence supporting a public health initiative to prevent perinatal mood disorders.55 We report a pilot efficacy trial of PREPP, a postpartum depression prevention intervention for at risk pregnant women that is (1) integrated into OB care to increase accessibility, (2) brief, (3) designed with the mother-infant dyad in mind. PREPP shows high levels of patient engagement and relatively low attrition in sample of women living in poverty and provides modest reductions in sub-clinical depression and anxiety symptoms in the early fourth trimester.56

Supplementary Material

Figure 3.

Mean symptom scale scores by PREPP intervention and control

*Mean Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety (HRSA), Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSA), and Edinburgh Postnatal Deprssion (EPDS) scale scores in the third trimester of pregnancy (baseline), and 6, 10, and 16 weeks postpartum.

AJOG AT A GLANCE:

A. Why was this study conducted?

The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends that clinicians provide or refer pregnant and postpartum women who are at increased risk of perinatal depression to counseling interventions. This report tests the efficacy of a dyadic-focused preventive perinatal psychotherapy intervention, Practical Resources for Effective Postpartum Parenting (PREPP), in women at high risk for perinatal mental health disorders based on poverty status.

B. What are the key findings?

PREPP reduced depression and anxiety symptoms at 6-weeks postpartum in low-income urban women— a key timepoint for identifying postpartum depression (PPD) during the postpartum visit. Overall depression and anxiety symptomology was low across the sample, and no differences were found in incidence of frank PPD or anxiety across the groups.

C. What does this study add to what is already known?

Consistent with previous findings, PREPP, a brief psychotherapy intervention integrated into obstetric care, leads to modest reductions in sub-diagnostic symptomatology in women at risk for maternal mental health disorders based on income level.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Robinhood Foundation.

References

- 1.Yeaton-Massey A, Herrero T. Recognizing maternal mental health disorders: beyond postpartum depression. Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2019;31(2):116–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weissman MM, Berry OO, Warner V, et al. A 30-year study of 3 generations at high risk and low risk for depression. JAMA psychiatry. 2016;73(9):970–977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luca DL, Garlow N, Staatz C, Margiotta C, Zivin K. Societal Costs of Untreated Perinatal Mood and Anxiety Disorders in the United States. Mathematica Policy Research;2019. [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Connor E, Senger CA, Henninger ML, Coppola E, Gaynes BN. Interventions to Prevent Perinatal Depression: Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Jama. 2019;321(6):588–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, et al. Interventions to Prevent Perinatal Depression. JAMA. 2019;321(6):580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Werner EA, Gustafsson HC, Lee S, et al. PREPP: postpartum depression prevention through the mother–infant dyad. Archives of women’s mental health. 2016;19(2):229–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knitzer J, Theberge S, Johnson K. Reducing maternal depression and its impact on young children: Toward a responsive early childhood policy framework. New York, NY: National Center for Children in Poverty;2008. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cyr C, Euser EM, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Van Ijzendoorn MH. Attachment security and disorganization in maltreating and high-risk families: A series of meta-analyses. Development and psychopathology. 2010;22(1):87–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petterson SM, Albers AB. Effects of poverty and maternal depression on early child development. Child development. 2001;72(6):1794–1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grote NK, Katon WJ, Lohr MJ, et al. Culturally relevant treatment services for perinatal depression in socio-economically disadvantaged women: the design of the MOMCare study. Contemporary clinical trials. 2014;39(1):34–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grote NK, Katon WJ, Russo JE, et al. Collaborative care for perinatal depression in socioeconomically disadvantaged women: a randomized trial. Depression and anxiety. 2015;32(11):821–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kochanska G, Murray KT. Mother–child mutually responsive orientation and conscience development: From toddler to early school age . Child development. 2000;71(2):417–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aksan N, Kochanska G, Ortmann MR. Mutually responsive orientation between parents and their young children: Toward methodological advances in the science of relationships. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42(5):833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feldman R From biological rhythms to social rhythms: Physiological precursors of mother-infant synchrony. Developmental psychology. 2006;42(1):175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feldman R Parent–infant synchrony and the construction of shared timing; physiological precursors, developmental outcomes, and risk conditions. Journal of Child psychology and Psychiatry. 2007;48(3-4):329–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olds DL, Kitzman H, Hanks C, et al. Effects of nurse home visiting on maternal and child functioning: age-9 follow-up of a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2007;120(4):e832–e845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cassidy J, Ziv Y, Stupica B, et al. Enhancing attachment security in the infants of women in a jail-diversion program. Attachment & Human Development. 2010;12(4):333–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huber A, McMahon C, Sweller N. Improved parental emotional functioning after circle of security 20-week parent–child relationship intervention. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2016;25(8):2526–2540. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sadler LS, Slade A, Close N, et al. Minding the baby: Enhancing reflectiveness to improve early health and relationship outcomes in an interdisciplinary home-visiting program. Infant mental health journal. 2013;34(5):391–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Slade A, Holland ML, Ordway MR, et al. Minding the Baby®: Enhancing parental reflective functioning and infant attachment in an attachment-based, interdisciplinary home visiting program. Development and psychopathology. 2019:1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dimidjian S, Goodman SH, Felder JN, Gallop R, Brown AP, Beck A. An open trial of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for the prevention of perinatal depressive relapse/recurrence. Archives of women’s mental health. 2015;18(1):85–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dimidjian S, Goodman SH, Felder JN, Gallop R, Brown AP, Beck A. Staying well during pregnancy and the postpartum: a pilot randomized trial of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for the prevention of depressive relapse/recurrence. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2016;84(2):134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tragea C, Chrousos GP, Alexopoulos EC, Darviri C. A randomized controlled trial of the effects of a stress management programme during pregnancy. Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 2014;22(2):203–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meins E, Fernyhough C, Wainwright R, Das Gupta M, Fradley E, Tuckey M. Maternal mind–mindedness and attachment security as predictors of theory of mind understanding. Child development. 2002;73(6):1715–1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barr RG, Rivara FP, Barr M, et al. Effectiveness of educational materials designed to change knowledge and behaviors regarding crying and shaken-baby syndrome in mothers of newborns: a randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2009;123(3):972–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Sleuwen BE, Engelberts AC, Boere-Boonekamp MM, Kuis W, Schulpen TW, L’Hoir MP. Swaddling: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2007;120(4):e1097–e1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pinilla T, Birch LL. Help Me Make It Through the Night: Behavirol Entrainment Breast-Fed Infants’ Sleep Patterns. Pediatrics. 1993;91(2):436–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hunziker UA, Barr RG. Increased carrying reduces infant crying: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. 1986;77(5):641–648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.James-Roberts IS, Hurry J, Bowyer J, Barr RG. Supplementary carrying compared with advice to increase responsive parenting as interventions to prevent persistent infant crying. Pediatrics. 1995;95(3):381–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hamilton M A rating scale for depression. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 1960;23(1):56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression: development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. The British journal of psychiatry. 1987;150(6):782–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of general internal medicine. 2001;16(9):606–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hamilton M The assessment of anxiety states by rating. British journal of medical psychology. 1959;32(1):50–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hoertel N, López S, Peyre H, et al. Are symptom features of depression during pregnancy, the postpartum period and outside the peripartum period distinct? Results from a nationally representative sample using item response theory (IRT). Depression and anxiety. 2015;32(2):129–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller ES, Hoxha D, Wisner KL, Gossett DR. Obsessions and compulsions in postpartum women without obsessive compulsive disorder. Journal of Women’s Health. 2015;24(10):825–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Battle CL, Zlotnick C, Miller IW, Pearlstein T, Howard M. Clinical characteristics of perinatal psychiatric patients: a chart review study. The Journal of nervous and mental disease. 2006;194(5):369–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ji S, Long Q, Newport DJ, et al. Validity of depression rating scales during pregnancy and the postpartum period: impact of trimester and parity. Journal of psychiatric research. 2011;45(2):213–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chabrol H, Teissedre F, Saint-Jean M, Teisseyre N, Roge B, Mullet E. Prevention and treatment of post-partum depression: a controlled randomized study on women at risk. Psychological medicine. 2002;32(6):1039–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Evans LM, Myers MM, Monk C. Pregnant women’s cortisol is elevated with anxiety and depression—but only when comorbid. Archives of women’s mental health. 2008;11(3):239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hanusa BH, Scholle SH, Haskett RF, Spadaro K, Wisner KL. Screening for depression in the postpartum period: a comparison of three instruments. Journal of Women’s Health. 2008;17(4):585–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF III, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry research. 1989;28(2):193–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pettersson A, Boström KB, Gustavsson P, Ekselius L. Which instruments to support diagnosis of depression have sufficient accuracy? A systematic review. Nordic journal of psychiatry. 2015;69(7):497–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chaudron LH, Szilagyi PG, Tang W, et al. Accuracy of depression screening tools for identifying postpartum depression among urban mothers. Pediatrics. 2010;125(3):e609–e617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Suri R, Burt V, Altshuler L. Nefazodone for the treatment of postpartum depression. Archives of women’s mental health. 2005;8(1):55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Matza LS, Morlock R, Sexton C, Malley K, Feltner D. Identifying HAM-A cutoffs for mild, moderate, and severe generalized anxiety disorder. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2010;19(4):223–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.First MB, France A, Pincus HA. DSM-IV-TR guidebook. American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stephens S, Ford E, Paudyal P, Smith H. Effectiveness of psychological interventions for postnatal depression in primary care: a meta-analysis. The Annals of Family Medicine. 2016;14(5):463–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ukatu N, Clare CA, Brulja M. Postpartum depression screening tools: a review. Psychosomatics. 2018;59(3):211–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.O’Connor E, Rossom RC, Henninger M, Groom HC, Burda BU. Primary care screening for and treatment of depression in pregnant and postpartum women: evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Jama. 2016;315(4):388–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tandon SD, Cluxton-Keller F, Leis J, Le H-N, Perry DF. A comparison of three screening tools to identify perinatal depression among low-income African American women. Journal of affective disorders. 2012;136(1–2):155–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goyal D, Gay C, Lee KA. How much does low socioeconomic status increase the risk of prenatal and postpartum depressive symptoms in first-time mothers? Women’s Health Issues. 2010;20(2):96–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ioannidis JP. Why most clinical research is not useful. PLoS medicine. 2016;13(6):e1002049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weinfurt KP, Hernandez AF, Coronado GD, et al. Pragmatic clinical trials embedded in healthcare systems: generalizable lessons from the NIH Collaboratory. BMC medical research methodology. 2017;17(1):144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.O’Connor E, Senger CA, Henninger ML, Coppola E, Gaynes BN. Interventions to Prevent Perinatal Depression. JAMA. 2019;321(6):588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tully KP, Stuebe AM, Verbiest SB. The fourth trimester: a critical transition period with unmet maternal health needs. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2017;217(1):37–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.