Abstract

Senescent cells affect many physiological and pathophysiological processes. While select genetic and epigenetic elements for senescence induction have been identified, the dynamics, epigenetic mechanisms and regulatory networks defining senescence competence, induction and maintenance remain poorly understood, precluding the deliberate therapeutic targeting of senescence for health benefits. Here, we examined the possibility that the epigenetic state of enhancers determines senescent cell fate. We explored this by generating time-resolved transcriptomes and epigenome profiles during oncogenic RAS-induced senescence and validating central findings in different cell biology and disease models of senescence. Through integrative analysis and functional validation, we reveal links between enhancer chromatin, transcription factor recruitment and senescence competence. We demonstrate that activator protein 1 (AP-1) ‘pioneers’ the senescence enhancer landscape and defines the organizational principles of the transcription factor network that drives the transcriptional programme of senescent cells. Together, our findings enabled us to manipulate the senescence phenotype with potential therapeutic implications.

Cellular senescence plays beneficial roles during embryonic development, wound healing and tumour suppression. Paradoxically, it is also considered a significant contributor to ageing and age-related diseases, including cancer and degenerative pathologies1.

Cellular senescence is a cell fate that stably arrests the proliferation of damaged and dysfunctional cells. The most prominent inducers of senescence are hyper-activated oncogenes (oncogene-induced senescence (OIS)) and therapeutic interventions to induce senescence in cancerous cells (therapy-induced senescence (TIS))2. Senescence arrest is accompanied by widespread changes in gene expression, including a senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), which involves the expression and secretion of inflammatory cytokines, growth factors, proteases and other molecules such as stemness factors3–5.

Our knowledge on epigenetic mechanisms underlying senescence has only recently increased6–10. However, critical gene-regulatory aspects of senescence cell fate remain poorly understood. Enhancers are key genomic regions that drive cell-fate transitions11. In mammalian cells, enhancer elements are broadly divided into two categories: active and poised. While active enhancers are characterized by the simultaneous presence of methylation of histone 3 on lysine 4 (H3K4me1) together with acetylation of histone 3 on lysine 27 (H3K27ac) and are associated with actively transcribed genes, poised enhancers are only marked by H3K4me1 and their target genes are generally not expressed12. A subset of enhancers may also be activated de novo from genomic areas devoid of any transcription factor (TF) binding and histone modifications13,14. Recent studies showed a role for enhancer remodelling in driving9,10,15 senescence-associated gene expression . It is currently unknown which enhancer elements, epigenetic marks or TFs render cells competent to respond to senescence-inducing signals.

Pioneer TFs are critical in establishing new cell-fate competence by granting long-term chromatin access to non-pioneer factors and are also crucial determinants of cell identity through their opening and licensing of the enhancer landscape16. The pioneer TFs that bestow senescence potential have not been identified to date.

In this study, we used dynamic analyses of transcriptome and epigenome profiles to show that the epigenetic state of enhancers predetermines their sequential activation during senescence. We demonstrate that activator protein 1 (AP-1) ‘imprints’ the senescence enhancer landscape to effectively regulate transcriptional activities pertinent to the timely execution of the senescence programme. We define and validate a hierarchical TF network model and demonstrate its effectiveness for the design of senescence reprogramming experiments. Together, our findings define the dynamic nature and organizational principles of gene-regulatory elements driving the senescence programme and reveal promising pathways for the therapeutic manipulation of senescent cells.

Results

Time-resolved transcriptome and epigenome profiling to dissect the senescence code.

We employed time-series experiments of human lung fibroblasts (strain WI-38) undergoing OIS using a tamoxifen-inducible ER:RASv12 expression system7 (RAS-OIS). We determined global gene expression profiles by microarrays and mapped the accessible chromatin sites by ATAC-seq (assay for transposase-accessible chromatin using sequencing)17 to deduce TF binding dynamics and hierarchies at six time points (0 (T0), 24, 48, 72, 96 and 144h). Cells intended for ChIP-seq (chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing) were crosslinked at three time points (T0, 72 and 144 h) and used for profiling histone modifications including H3K4me1 (putative enhancers), H3K4me3 (promoters), H3K27ac (active enhancers and promoters) and H3K27me3 (polycomb-repressed chromatin) (Fig. 1a). For comparison, we included WI-38 cells undergoing quiescence (at time points of T0, 12, 24, 48, 72 and 96 h) by withdrawing serum for up to 96h. We validated our approach in two additional senescence models using WI-38 cells: (1) oncogenic RAF-induced senescence (RAF-OIS; at time points of T0, 12, 24, 48, 72 and 96 h for transcriptome and ATAC-seq analysis, and T0, 48 and 96 h for H3K4me1 and H3K27ac ChIP-seq); (2) replicative senescence (RS; at time points of T0, 144, 264, 432, 624, 792, 1,008 and 2,112 h for transcriptome and ATAC-seq analysis, and T0, 264, 1,008 and 2,112h for H3K4me1 and H3K27ac ChIP-seq analysis), and in RAS-OIS of GM21 skin fibroblasts (time points of T0, 192 and 336 h for transcriptome and ATAC-seq analysis). Quiescence and senescence were verified using classical senescence-associated biomarkers (Extended Data Fig. 1).

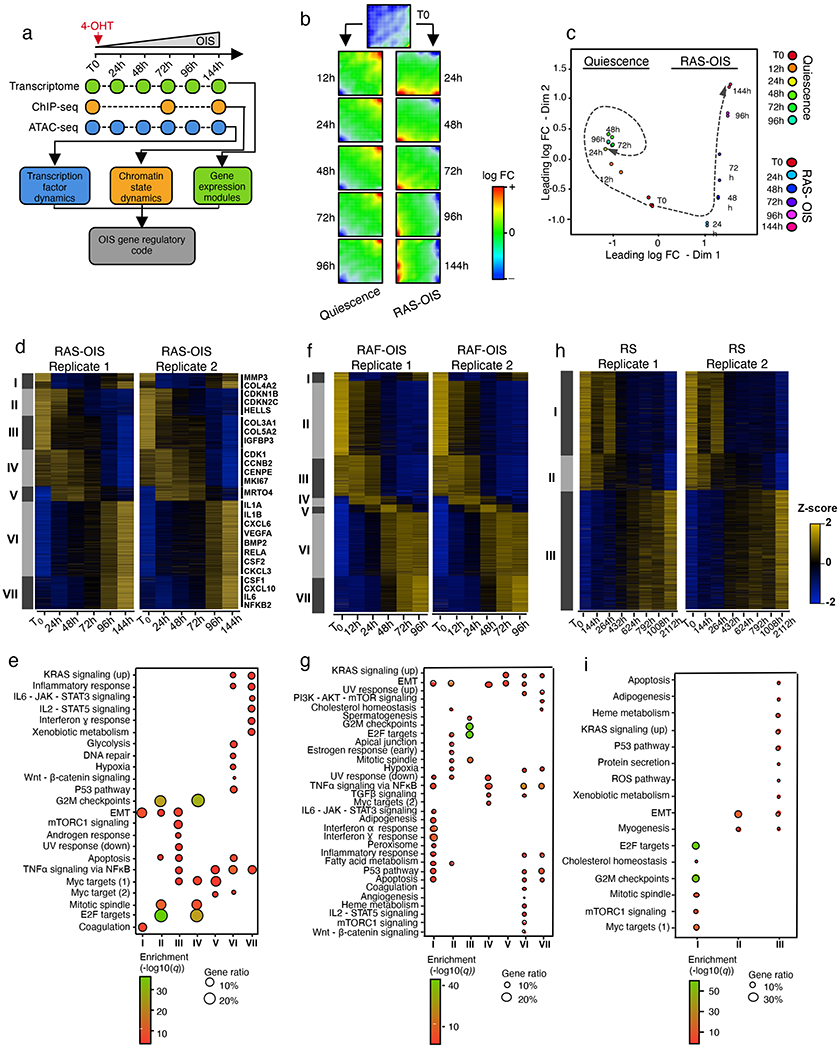

Fig. 1 |. Multistate establishment of the senescence transcriptional programme.

a, Schematic overview of defining the gene-regulatory code of RAS-OIS in WI-38 fibroblasts using time-resolved, high-throughput transcriptome (microarray) and epigenome (ChIP-seq and ATAC-seq) datasets. Quiescence and all other models of senescence followed the same scheme (two biologically independent time-series experiments per condition). b, SOMs of gene expression profiles in WI-38 fibroblasts for quiescence and RAS-OIS time-series experiments as logarithmic fold-change (FC). Red areas mark overexpression, blue areas underexpression. Each map depicts the average SOM profile across two biologically independent experiments per treatment. c, Multidimensional scaling analysis scatter plot visualizing the level of similarity and dissimilarity between normalized quiescence and RAS-OIS time-series transcriptomes in WI-38 fibroblasts. Distances between samples represent leading logarithmic FCs defined as the root-mean-squared average of the logarithmic FCs for the genes best distinguishing each pair of samples collected from two biologically independent experiments for each treatment and time point. d,f,h, Heatmaps showing modules of temporally co-expressed genes specific for RAS-OIS (d), RAF-OIS (f) and RS (h) in WI-38 fibroblasts defined using an unsupervised weighted gene co-expression network analysis clustering approach. Roman numerals refer to different gene clusters defined by WGCNA for each inducer. Data are expressed as row Z-scores collected from two biologically independent experiments per condition. For RAS-OIS, representative genes are depicted for each module. e,g,i, Functional over-representation map depicting Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) hallmark gene sets associated with each transcriptomic cluster for RAS-OIS (e), RAF-OIS (g) and RS (i). Circles are colour coded according to the FDR-corrected P value based on the hypergeometric test. Size is proportional to the percentage of genes in the MSigDB gene set belonging to the cluster. N> 200 genes per transcriptomic module for each senescence inducer.

Multistate establishment of the senescence transcriptional programme.

To visualize dynamic gene expression patterns across the entire quiescence and RAS-OIS time courses in WI-38 fibroblasts, we applied an unsupervised, self-organizing map (SOM) machine-learning technique18 (Fig. 1b) and multidimensional scaling (Fig. 1c) to our transcriptome datasets. Remarkably, serum-deprived fibroblasts rapidly established a quiescent-specific gene expression programme within 24h after serum deprivation, which changed marginally afterwards (Fig. 1b, left column, and Fig. 1c), and mainly involved only upregulated (Fig. 1b, top right corner, red) and downregulated (Fig. 1b, bottom left corner, blue) genes. By contrast, RAS-OIS cells displayed dynamic gene expression trajectories that evolved steadily, both for upregulated (red) and downregulated metagenes (blue) (Fig. 1b,c), which was corroborated by the expression profiles of a selection of senescence-associated genes (Extended Data Fig. 1m). Next, we calculated the diversity and specialization of transcriptomes and gene specificity19 (Extended Data Fig. 2a). RAS-OIS cells exhibited a temporally evolving increase in transcriptional diversity, whereas quiescent cells exhibited a temporally evolving specific gene expression programme.

To further delineate the evolution of the RAS-OIS gene expression programme, we compared the quiescence and RAS-OIS transcriptome datasets. A total of 4,986 genes (corresponding to 2,931 upregulated and 2,055 downregulated genes) were differentially regulated in at least one time point (with a minimal leading log2 fold-change of 1.2; q = 5 × 10−4) and partitioned into seven (I–VII) gene expression modules with distinct functional over-representation profiles in line with the senescence phenotype (Fig. 1d,e; Extended Data Fig. 2b; Supplementary Table 1). The highly reproducible gene expression dynamics and modularity during RAS-OIS transition suggest a high degree of preprogramming of this succession of cell states, which we confirmed in additional senescence models; that is, WI-38 lung fibroblasts undergoing RAF-OIS and RS (Fig. 1f–i), as well as in GM21 skin fibroblasts undergoing RAS-OIS (Extended Data Fig. 2c,d). In particular, cell-cycle-related and SASP-related transcriptional modules were highly similar across all senescence models.

Altogether, our investigation of transcriptome dynamics in different senescence models defined a modular organization and transcriptional diversity of the senescence gene expression programme.

A dynamic enhancer programme shapes the senescence transcriptome.

An unanswered question is how TFs and epigenetic modifications cooperatively shape a transcriptionally permissive enhancer landscape to endow the cell with senescence potential.

To answer this question, we first mapped genomic regulatory elements in WI-38 fibroblasts undergoing RAS-OIS by profiling histone modifications via ChIP-seq (Supplementary Table 2) and transposon-accessible chromatin via ATAC-seq. ChromstaR analysis of the ChIP-seq data identified a total of 16 chromatin states in RAS-OIS cells (Extended Data Fig. 3a). The majority of the genome (~80%) was, irrespective of the time point, either devoid of any of the histone modifications analysed (~62%) or polycomb-repressed (~18%). The fraction of the genome represented by active and accessible chromatin states that is, enhancers and promoters) was comparably lower (~20% combined). Chromatin state transitions occurred most prominently at enhancers, while promoters were modestly affected (Fig. 2a,b; Extended Data Fig. 3a, see insets indicated by arrows) congruent with previous results9. Unexpectedly, many enhancers were activated de novo (that is, acquisition of H3K4me1 and H3K27ac) from unmarked chromatin at the T0–72 h and 72–144-h intervals. This was followed by the more stereotypical enhancer activation state from a poised state (H3K4me1+plus H3K27ac acquisition) and enhancer poised state from the unmarked and polycomb-repressed state at the T0–72 h interval (acquisition of H3K4me1) (Fig. 2a,b). Dynamics of sequential enhancer activation was preserved in WI-38 fibroblasts undergoing RAF-OIS and RS (Extended Data Fig. 3b,c).

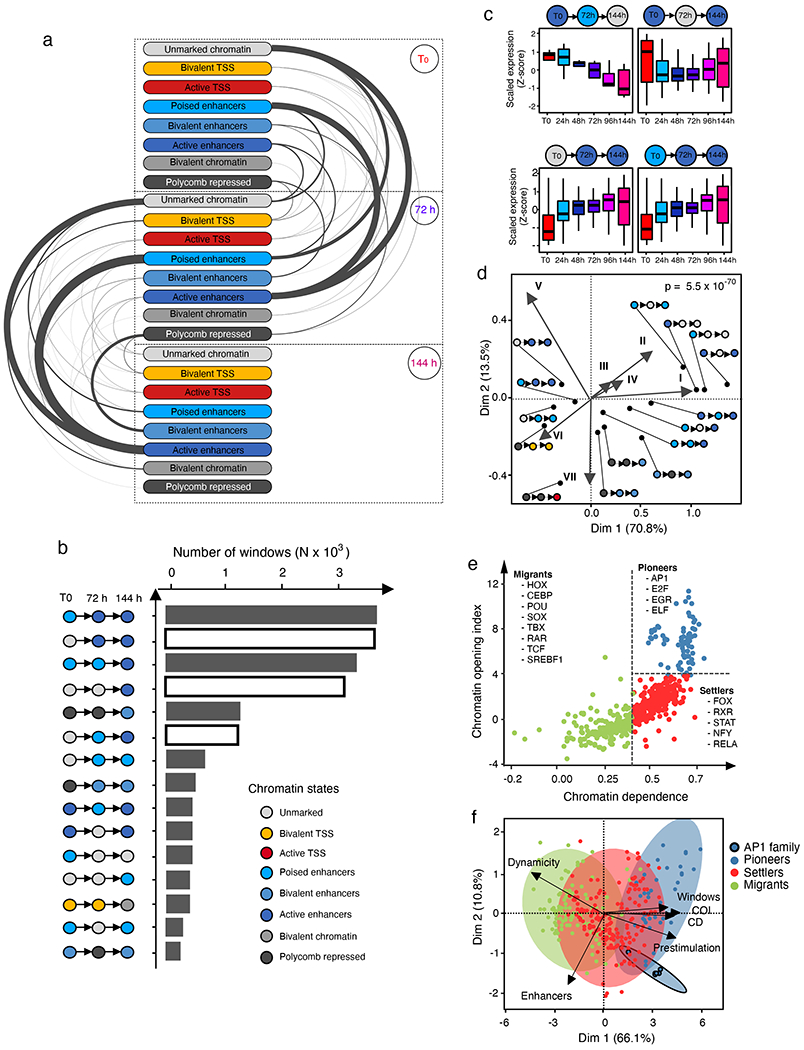

Fig. 2 |. A dynamic enhancer programme shapes the senescence transcriptome.

a, Arc plot visualizing dynamic chromatin state transitions for the indicated intervals during RAS-OIS in WI-38 fibroblasts. The edge width is proportional to the number of transitions. The plot shows the average transition landscape. TSS, transcription start site. b, Histogram showing the total number of windows of top 15 chromatin state transitions during RAS-OIS in WI-38 fibroblasts. Chromatin state transitions corresponding to de novo enhancer activation are highlighted as white bars. c, Boxplots showing time-resolved gene expression profiles (row Z-score) for genes associated with regions undergoing different chromatin state changes. The pictogram at the top of each graph describes the chromatin state transition class. The centre lines depict the median, the lower and upper edges of the boxes correspond to the first and third quartiles. The upper whisker extends from the edge of the box to the largest value up to 1.5× the interquartile range (IQR) from the edge, while the lower whisker extends from the box edge to the smallest value at 1.5× the IQR of the edge (two biologically independent time-series). d, Asymmetric biplot of the CA between changes in chromatin states and gene expression modules. The P value reflects the strength of association as assessed using χ2 test. Only the top 20 contributing and best projected (squared cosine > 0.5) chromatin state changes are shown (see b for the colour code). e, Chromatin dependence (CD) versus chromatin opening index (COI) plotted for high-confidence TF sequence motifs used in our study during RAS-OIS in WI-38 fibroblasts. Pioneer, settler and migrant TFs as defined by their COI and CD property are colour coded, and select members of each TF class are listed. f, Biplot of the PCA performed with select TF-binding parameters during RAS-OIS in WI-38 fibroblasts: dynamicity, total number of bound windows (N), percentage of binding at enhancers, pioneer index, COI and CD. The plot depicts projections of TFs and loading of different covariates for first two PCs explaining 76.9% of total inertia. The ellipses delineate 95% confidence intervals for AP-1 pioneers, non-AP-1 pioneers, settlers and migrants. Data shown in a-e were collected from two biologically independent experiments. For f, all parameters were computed from pooled ATAC-seq datasets from three biologically independent experiments.

The chronology of enhancer activation was highly concordant with the temporal expression pattern of the nearest genes (Fig. 2c). In line with this, correspondence analysis (CA) (Fig. 2d) revealed a strong correlation between gene expression modules (Fig. 1d) and chromatin state transitions (Fig. 2a).

We next determined which TFs are key drivers for the dynamic enhancer remodelling driving the senescence transcriptome. We first intersected ATAC-seq peaks with the identified enhancer coordinates (Fig. 2a,b) and performed a motif over-representation test. This analysis identified AP-1 superfamily members (cJUN, FOS, FOSL1, FOSL2 and BATF) and AP-1-associated TFs (ATF3 and ETS1) as the most enriched motifs at any given time point (Extended Data Fig. 3d). To exclude the possibility that the observed enrichment of AP-1 TFs at enhancers is strictly dependent on oncogenic RAS signalling per se and not a reflection of a specific pioneering role in the enhancer landscape independent of RAS signalling, we compared ATAC-seq peaks for TF binding sites in WI-38 lung fibroblasts undergoing RAS-OIS, RAF-OIS or RS, in GM21 skin fibroblasts undergoing RAS-OIS, and in growth-factor-deprived (and therefore RAS signalling muted) quiescent WI-38 fibroblasts (Extended Data Fig. 3e–i). In all cases, the AP-1 motif was the predominant motif enriched, thus corroborating the notion that AP-1 TFs act as universal pioneers imprinting the senescence enhancer landscape.

We further analysed our time-resolved RAS-OIS ATAC-seq datasets by adapting the protein interaction quantitation (PIQ) algorithm20. PIQ enables the functional hierarchization of TFs into pioneers, settlers and migrants (Supplementary Table 4). PIQ segregated TFs into pioneers (for example, AP-1 TF family members), settlers (for example, NFY and RELA subunit of NF-κB) and migrants (for example, TF RAR family members and SREBF1) (Fig. 2e). We confirmed this TF hierarchization by inspecting a selection of individual TF footprints for their adjacent nucleosomal positioning (Extended Data Fig. 3j). Importantly, there was a high correspondence between PIQ predictions and TF ChIP-seq profiling as exemplified for RELA and the AP-1 members FOSL2 and cJUN (Extended Data Fig. 3k–m; Supplementary Table 5).

Next, we applied a principal component analysis (PCA) that considered several metrics describing TF binding characteristics (Fig. 2f). This analysis revealed two key features. First, pioneer TFs bind statically, extensively and, most importantly, before RAS-OIS induction (that is, prestimulation) along the genome, while settler and migrant TFs bind more dynamically (Fig. 2f, Dynamicity), far less frequently (Fig. 2f, Windows) and on average less often before OIS induction that is, prestimulation) along the genome. Second, AP-1 TFs clearly stand out among other pioneer TFs (highlighted by black circles in Fig. 2f) because they bind exclusively and extensively to enhancers before RAS-OIS induction, whereas most of the remaining pioneer TFs tend to accumulate away from them.

In summary, we identified de novo enhancer activation and AP-1 as key elements that pioneer and shape a transcriptionally permissive enhancer landscape in senescence.

AP-1 pioneer TF bookmarking of enhancers foreshadows the senescence transcriptional programme.

Given our finding that most of the enhancer activation occurred de novo out of unmarked chromatin territories, we explored the role of AP-1 as a general bookmarking agent for future and past enhancer activity.

Quantification of enhancer mark dynamics (Fig. 3a; Extended Data Fig. 4a–c; Supplementary Table 3) unveiled that for windows shifting from the ‘unmarked’ state at T0 to an ‘active enhancer’ state (H3K4me1+H3K27ac+) at either 72 h or 144 h (that is, ‘de novo enhancers’) there is both a gradual increase in H3K4me1 and H3K27ac levels from initial levels (T0) similar to steady-state unmarked regions, but different from poised enhancers, to final levels (144h) indistinguishable from constitutive enhancers (Fig. 3a; Extended Data Fig. 4a,b). By contrast, for windows shifting from an ‘active enhancer’ state at T0 to an unmarked state at either 72h or 144h, which we refer to as ‘remnant enhancers’, there is a progressive decrease both in H3K4me1 and H3K27ac levels from initial levels indistinguishable from constitutive enhancers to final levels similar to unmarked regions and distinct from poised enhancers (Fig. 3a; Extended Data Fig. 4a,c). The dynamic behaviour of each enhancer class, on average, was associated with the expression profile of nearby genes (Extended Data Fig. 4d).

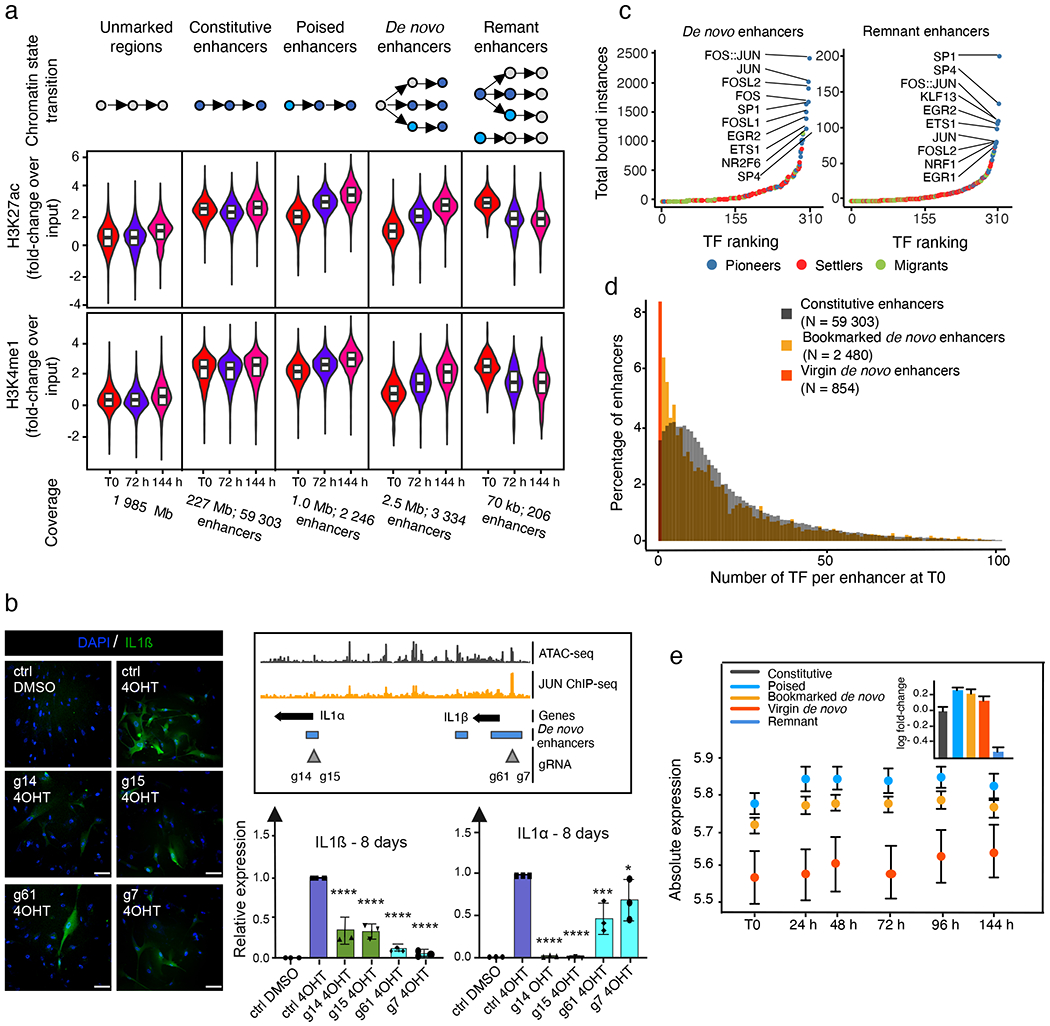

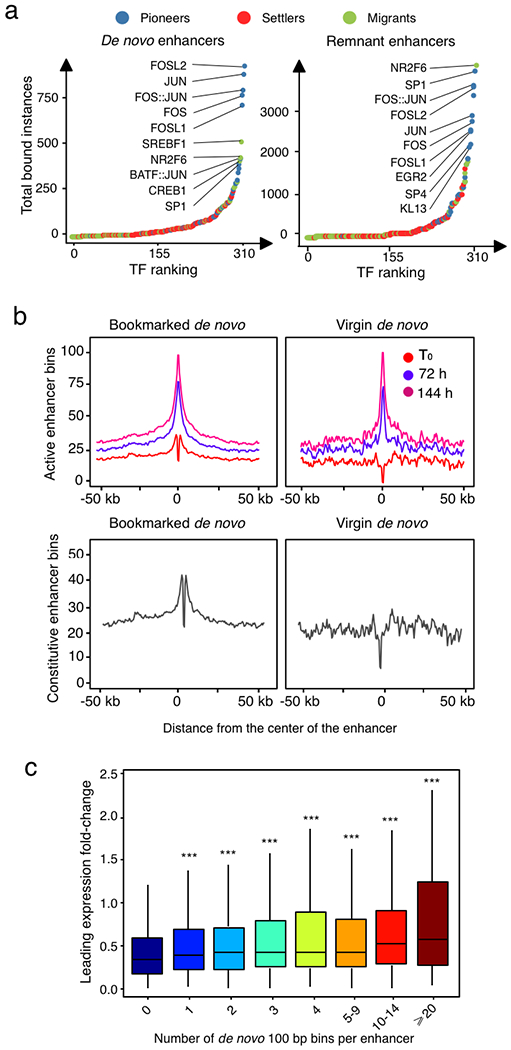

Fig. 3 |. AP-1 pioneer tF bookmarking of the senescence enhancer landscape foreshadows the senescence transcriptional programme.

a, Distribution of the FC in normalized enhancer marks H3K27ac and H3K4me1 ChIP-seq signals over input in genomic bins flagged as unmarked regions, constitutive enhancers, poised enhancers, de novo enhancers and remnant enhancers at indicated time points during RAS-OIS in WI-38 fibroblasts. Text underneath the chart specifies the genomic coverage in mega bases (Mb) for each category and the corresponding number of enhancers. Chromatin states were defined from two biologically independent experiments. Violin plots depict the average distribution of ChIP-seq signals over input across biological replicates. Centre lines depict the medians, and the lower and upper edges correspond to the first and third quartiles, respectively. b, WI-38-ER:RASv12 fibroblasts were super-infected with dCas9-KRAB and individual gRNAs (g14, 15, g61 and g7) targeting two de novo enhancers. Cells were pharmacologically selected and induced into RAS-OIS by 4-OHT. Eight days after RAS-OIS induction, cells were stained by indirect immunofluorescence for IL-1β (left) or analysed by RT-qPCR for IL1A and IL1B expression (lower right). Data represent the mean ± s.d. (n = 3 biologically independent experiments). *P = 0.0440, ***P = 0.0009, ****P < 0.0001. Comparison with control (Ctrl) 4-OHT, one-way ANOVA (one-sided Dunnett’s test). Scale bars, 100 μm. DMSO, dimethylsulfoxide. c, Rank plot depicting the summed occurrences for TF binding in de novo enhancers before RAS-OIS induction (left) and remnant enhancers after RAS-OIS induction (144 h) (right) in WI-38 fibroblasts. The top ten TFs are indicated. d, Distribution of total number (N) of TFs bound per enhancer for constitutive enhancers, bookmarked de novo enhancers and virgin de novo enhancers. e, The average absolute expression level log2 scale) kinetics for genes associated with poised, TF bookmarked de novo and TF virgin de novo enhancers. Circles depict the average absolute expression level, and bars depict the s.e.m. The inset histogram illustrates the average leading log2(FC) in expression (±s.e.m.) for genes associated with constitutive, poised, TF bookmarked de novo, TF virgin de novo and remnant enhancers collected from two biologically independent time series. Source data are provided.

To show the functional role of de novo enhancers, we used a CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) approach21. The expression of four different guide RNAs (gRNAs) targeting the dCas9-KRAB transcriptional repressor to de novo enhancers in the IL1A (which encodes interleukin-1α (IL-1α)) and IL1B (which encodes IL-1β) locus (g7, g14, g15 and g61) significantly reduced the expression of IL1B and IL1A analysed 8 or 14 days after oncogenic RAS induction, except for a mild reduction in IL1A expression induced by the two gRNAs (g61 and g7) adjacent to the IL1B promoter (Fig. 3b; Extended Data Fig. 4e). As controls, gRNA (g54) targeting a region just downstream of the IL1A/IL1B locus did not affect either expression, and gRNAs (g2 and g48) targeting sequences in between two de novo enhancers had moderate effects (Extended Data Fig. 4f).

We next determined whether TFs bookmark de novo enhancers for future activation and whether TFs bookmark remnant enhancers after their inactivation as part of a molecular memory. Indeed, we found that AP-1 is the predominant TF bookmarking de novo and remnant enhancers (Fig. 3c). Importantly, gRNAs chosen for CRISPRi were either overlapping with AP-1-binding sites (g14, g15 and g61) or in close proximity (g7, ~125 bp outside of it) (Fig. 3b), which highlight the importance of AP-1 in bookmarking de novo enhancers for future activation. Because CRISPRi can control repression over a length of two nucleosomes (~300 bp)22, it is highly probable that g7 also affected this AP-1-binding site. Moreover, a control gRNA (g2) targeting a non-enhancer AP-1 site (Extended Data Fig. 4f) did not affect IL1 expression, which suggests that only enhancer-positioned AP-1 sites are functional. Finally, examination of the positioning of AP-1 TFs in cells undergoing RS validated their importance for de novo and remnant enhancer bookmarking Extended Data Fig. 5a).

We noted that only 2,480 out of 3,334 de novo enhancers were TF bookmarked, while the remainder (n=854) lacked any detectable TF binding activity (Fig. 3d). Thus, de novo enhancers can be further divided into two subclasses, thereby expanding the senescence enhancer landscape: (1) TF bookmarked de novo enhancers and (2) TF virgin de novo enhancers that are reminiscent of previously described latent enhancers13,23. Next, we characterized the chromatin state environment of the two de novo enhancer classes. The chromatin state environment surrounding TF bookmarked and virgin de novo enhancers at T0 (that is, pre-OIS stimulation) were enriched and depleted in constitutive enhancers, respectively. Both AP-1-bookmarked and virgin de novo enhancers became progressively activated and expanded following RAS-OIS induction (Extended Data Fig. 5b). Congruent with this, the nearest genes associated with bookmarked de novo enhancers were already expressed at higher basal levels (as were genes proximal to poised enhancers) and reached significantly higher absolute expression levels with faster kinetics after RAS-OIS induction. By contrast, virgin de novo enhancers showed low-to-background basal expression levels and reached comparatively lower absolute expression levels with slower kinetics after RAS-OIS induction (Fig. 3e). Finally, we plotted leading gene expression fold-changes against the number of de novo enhancers in a given prospective senescence enhancer region. We discovered that a single de novo enhancer element of 100bp can substantially activate the expression of its nearest gene and that there is a positive correlation between the number and size of de novo enhancer elements and the increase in expression of their nearest genes (Extended Data Fig. 5c).

Altogether, our results provide evidence to indicate that de novo and remnant enhancers play critical roles in ensuring that pro-senescence genes are expressed at the correct time and at the correct level and highlight the importance of AP-1 bookmarking for epigenetic memorization of past and future enhancer activity to define the senescence transcriptional programme.

A hierarchical TF network defines the senescence transcriptional programme.

Currently, a TF network regulating senescence is not available, which precludes deliberate therapeutic manipulation of the senescence phenotype.

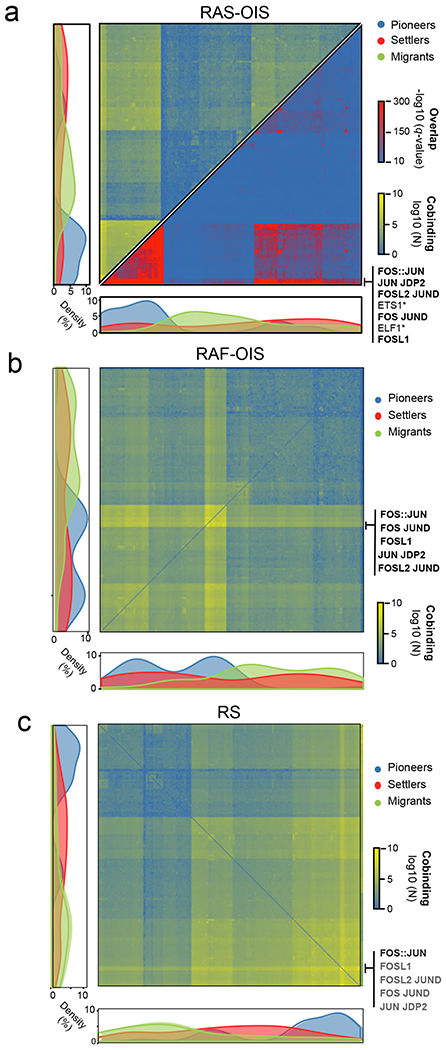

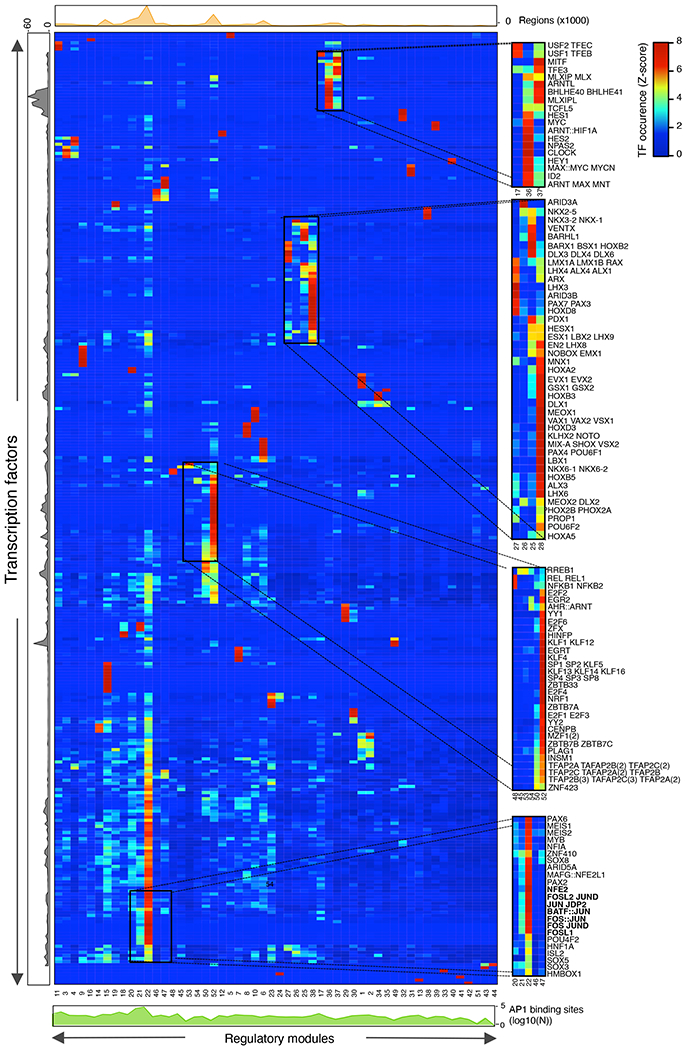

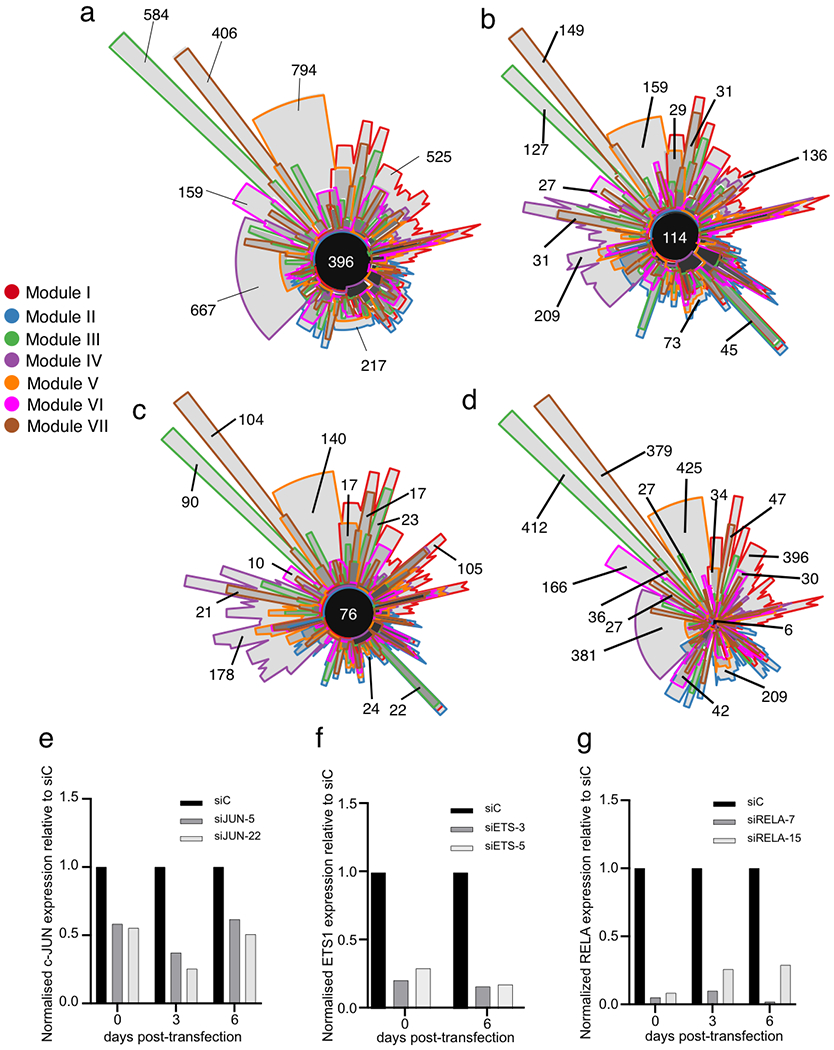

To elucidate the combinatorial and dynamic binding of TFs to enhancers and their organization into TF networks, we first computed co-occurring pairs of TFs in enhancers in WI-38 fibroblasts undergoing RAS-OIS, RAF-OIS or RS (Fig. 4a–c; Extended Data Fig. 6a; Supplementary Data 1). For RAS-OIS, we also applied a topic machine-learning approach that dissects the complexity of the combinatorial binding of many TFs into compact and easily interpretable regulatory modules or TF ‘lexicons’ that form the thematic structures driving the RAS-OIS gene expression programme24,25 (Fig. 5). These analyses illustrated two key points. First, as shown in the co-binding matrices in Fig. 4a–c and the heatmap in Fig. 5, AP-1 pioneer TFs interact genome-wide with most of the remaining non-pioneer TFs (that is, settlers and migrant TFs). Moreover, they have the highest total number of binding sites (Fig. 5, grey curve) and contribute to virtually all of the 54 TF lexicons (Fig. 5, green curve), with lexicon 22 being the most frequently represented lexicon genome-wide (Fig. 5, orange curve). Our interactive heatmap (Fig. 5; Supplementary Data 1) provides a valuable resource for generating hypotheses to functionally dissect TF interactions in cells undergoing RAS-OIS. Second, TF lexicon usage was associated with specific chromatin states (Extended Data Fig. 6b). For example, lexicons 21 and 22 are exclusively used for enhancers with most of the AP-1-binding instances, lexicon 50 is strongly related to polycomb-repressor-complex-repressed regions, and lexicons 44 and 52 predominantly associate with promoters (Extended Data Fig. 6c). Interestingly, among the most prominent TFs in lexicon 50 are the known polycomb-repressor-complex-interacting transcriptional co-repressor complex REST and insulator CTCF26,27. Moreover, the promoter-centric lexicon 52 contains many E2F TFs, which is in line with the primary role of E2Fs at promoters28.

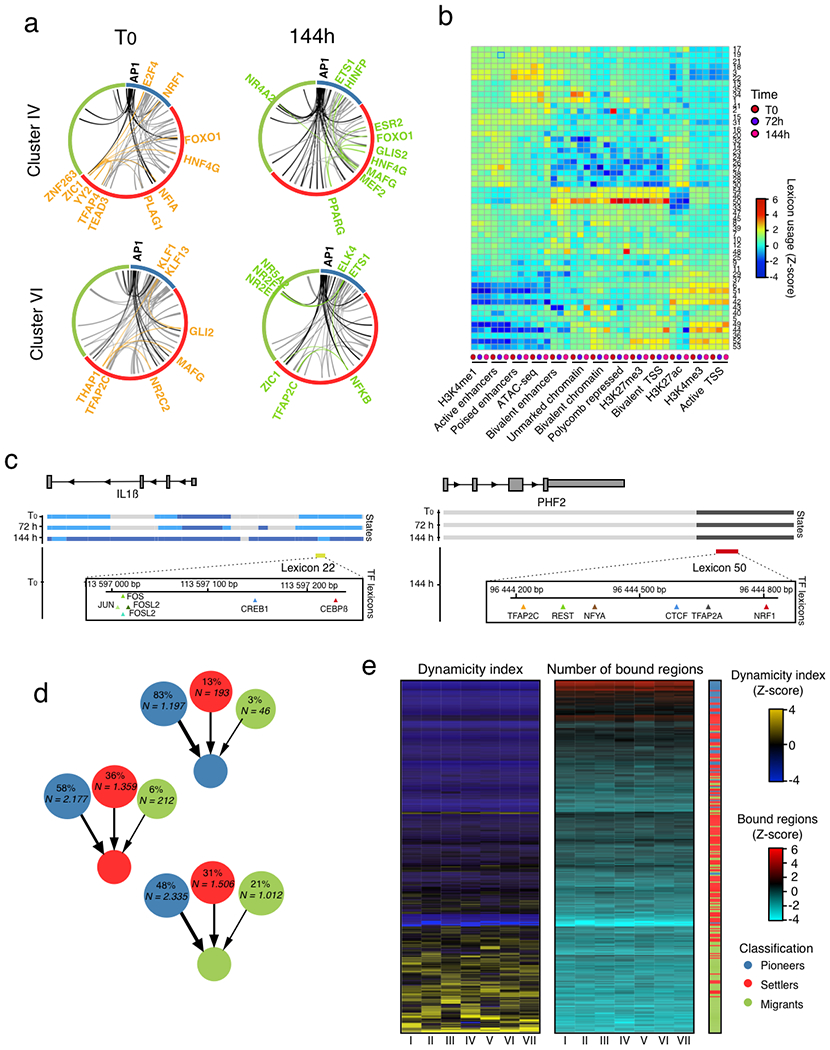

Fig. 4 |. A hierarchical tF network defines the senescence transcriptional programme.

a-c, Genome-wide TF co-binding occurrence matrix summed across all time points in WI-38 fibroblasts undergoing RAS-OIS (a), RAF-OIS (b) and RS (c) (left, shades from blue to yellow, in log10 scale). Overlap significance was calculated by hypergeometric test (right, shades from blue to red, in −log10 scale). The co-binding occurrence matrix was clustered using Ward’s aggregation criterion and corresponding corrected q values were projected on this clustering. Graphs on the left and below the matrix show the density in pioneer, migrant and settler TFs along each axis of the matrix. AP-1 members are indicated. TF footprinting was performed on ATAC-seq datasets pooled from three biologically independent experiments for RAS-OIS, and from two biologically independent experiments for RAF-OIS and RS. Maps show the average temporal co-binding profiles.

Fig. 5 |. A hierarchical tF network defines the senescence transcriptional programme.

Heatmap describing the association of individual TFs (row) with TF lexicons (columns). Four boxed out insets provide detailed information on the TF composition of lexicons. A comprehensive, high-resolution and interactive heatmap is shown in Supplementary Data 1. The right curve shows the total number of binding sites for each TF. The top curve shows the total number of regions for each regulatory module. The bottom curve shows the average proportion of AP-1-binding sites inside each regulatory module.

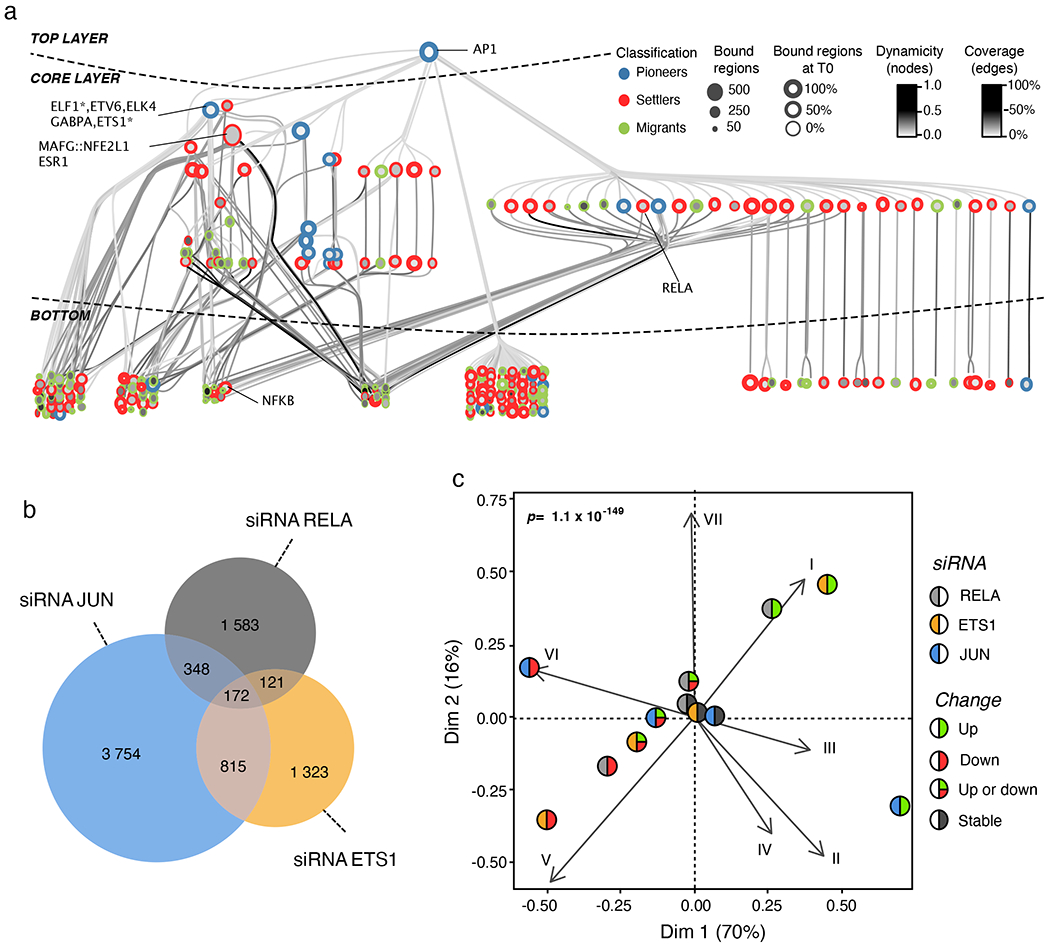

Next, we developed an algorithm, based on our temporal TF co-binding information and a previously published TF networking strategy29, to visualize the hierarchical structure of the senescence TF network. In Fig. 6a, we show a representative example of the TF network of the SASP gene module VI, which has a three-layered architecture: (1) a top layer defined exclusively by the AP-1 family of pioneer TFs, (2) a core layer composed mostly of other pioneer and settler TFs and (3) a bottom layer characterized by settler and igrant TFs. The core layer itself separates into multilevel and single-level core layers depending on the complexity of TF connectivity to the top and bottom layers (Fig. 6a). The organizational logic of the TF network is highly similar for all gene expression modules despite high TF diversity in the core and bottom layers (see the Cytoscape interactive maps hosted on Zenodo, detailed in the Code availability statement). The TF network topology for RAS-OIS is congruent with the biochemical and dynamic properties of each TF category (that is, pioneer, settler or migrant) in each layer of the network. As the interactions flow from the top to the bottom layer, there is an increasing dynamicity and number of TFs and a decreasing number of bound regions (Extended Data Fig. 6d,e). Ranking the dynamicity index and the number of bound regions for all TFs in each network confirmed the hierarchical principles of their organization, with a common core of highly connected TFs from the top and core layers shared across all networks (Extended Data Fig. 7a, black circle at the centre). Variability in the composition of the most dynamic TFs of the core and bottom layers defined the gene expression module specificity for each network and its corresponding specialized transcriptional output (Extended Data Fig. 7b–d), thus refuting the simple rule that co-expression indicates co-regulation30.

Fig. 6 |. A hierarchical tF network defines the senescence transcriptional programme.

a, Graphical representation of the hierarchical TF network for transcriptomic module VI. Nodes (circles) represent TFs and oriented edge (line) connecting TFs A and B means that at least 30% of the regions bound by B were also bound by A at the same time point or before. To simplify visualization, we represent strongly connected components (SCCs) as a single node and performed a transitive reduction (TR). The node colour is based on the average dynamicity of SCC members. The node border colour indicates their classification as pioneer, settler or migrant. The node border thickness encodes the percentage of bound regions before RAS stimulation. The edge colour was calculated according to the relative coverage of outgoing over incoming TF. The network has three layers: top, core and bottom. Nodes in the top layer have no incoming edges and nodes in the bottom layer have no outgoing edges. The core layer comprises TFs that have both incoming and outgoing edges. Interactive Cytoscape graphs are accessible as supplementary data hosted on Zenodo (see the Code availability statement). b, Venn diagram showing the specificities and overlaps in differentially expressed direct target genes after siRNA-mediated cJUN, ETS1 and RELA depletion in RAS-OIS WI-38 fibroblasts at 144 h (fully senescent cells). Genes are considered as direct targets of a given TF when PIQ predicts that the TF bound to an enhancer associates to this gene (see Methods for details). Promoters were excluded from the analysis. c, Asymmetric biplot of the CA between transcriptomic clusters and the number of upregulated, downregulated, up- or downregulated, or nonregulated (stable) genes after siRNA-mediated cJUN, ETS1 or RELA depletion. The P value reflects the strength of association as assessed with a χ2 test. Data shown in b and c were collected from two biologically independent experiments for each siRNA and target gene.

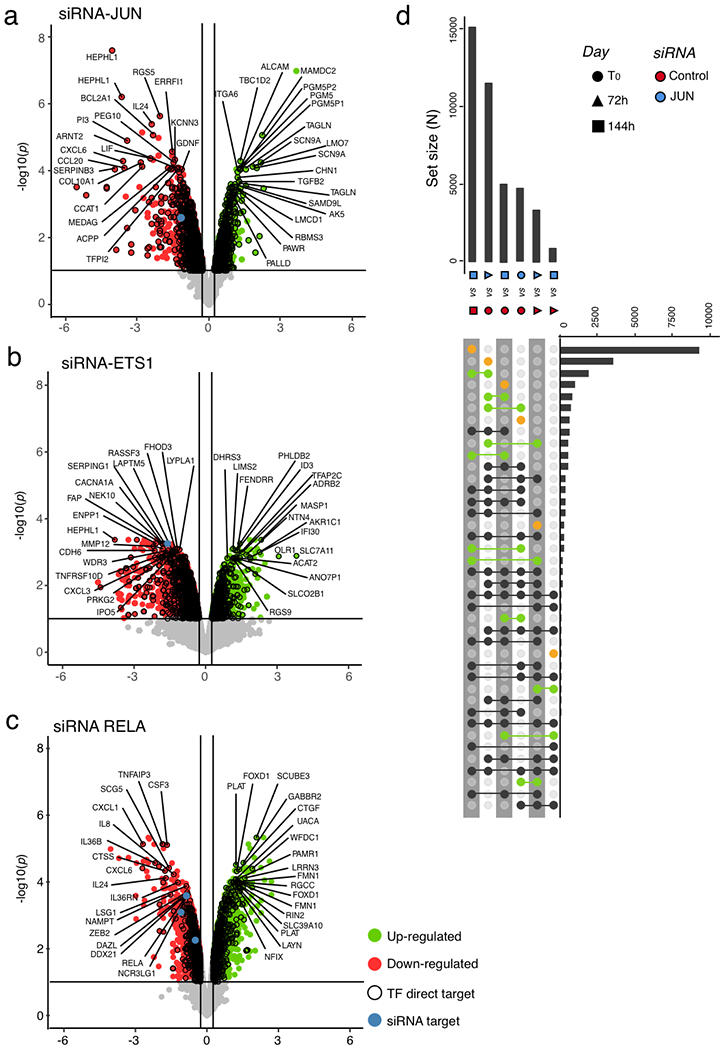

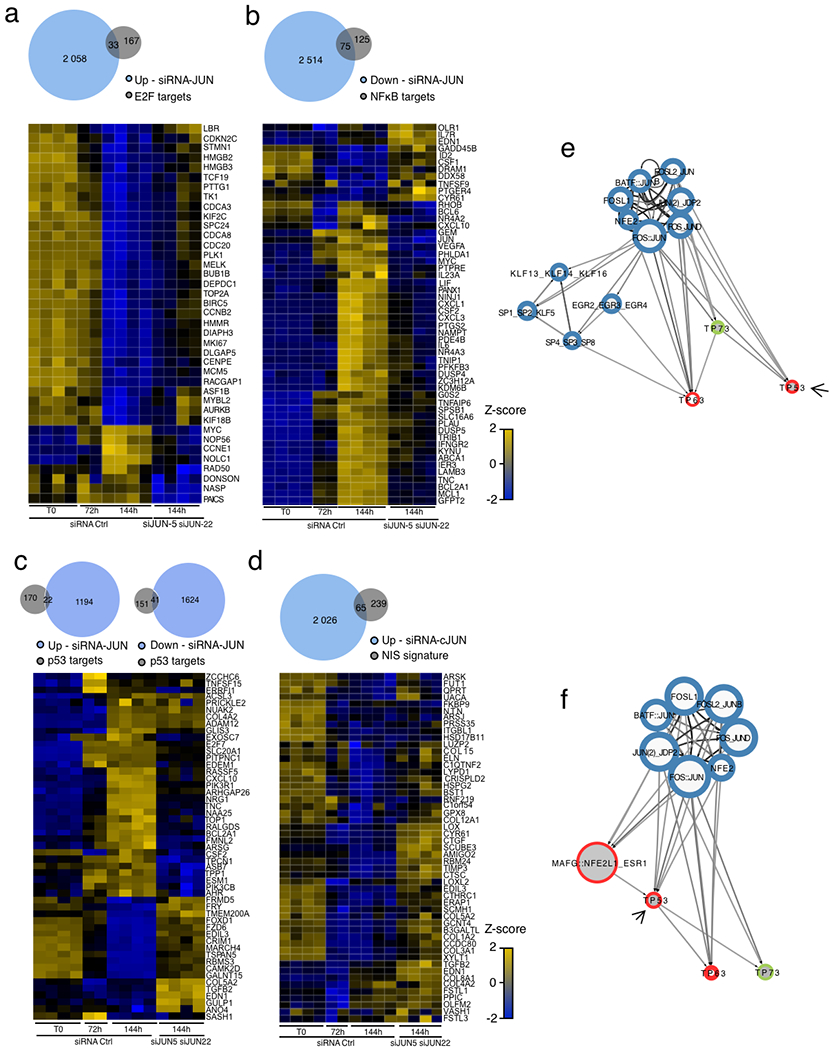

Our hierarchical TF network model for RAS-OIS enhancers predicted that the number of direct target genes regulated by a given TF is determined by its position in the TF network hierarchy. To test this, we performed RNA interference (via short interfering RNA (siRNA)) experiments targeting the AP-1 member cJUN (top layer), ETS1 (multilevel core layer) and RELA (single-level core layer) using two independent siRNAs per TF in fully senescent RAS-OIS cells (144h) (Supplementary Table 6), determined the global transcriptome profiles and compared them to the transcriptomes of cells transfected with a non-targeting siRNA (siControl) (Fig. 6b; Extended Data Fig. 7e–g). Consistent with the TF network hierarchy, silencing of cJUN affected the most substantial number of direct gene targets (n=5,089), followed by ETS1 (n=2,431) and RELA (n=2,224). Specifically, 172 genes were co-regulated by the three TFs, while 987 were co-regulated by cJUN and ETS1, 520 by cJUN and RELA, and 293 by ETS1 and RELA (Fig. 6b). CA revealed that perturbing the function of cJUN, ETS1 or RELA could faithfully separate upregulated (V-VII) from downregulated gene expression modules (I–IV) (Fig. 6c), which aligns with both the CA for chromatin states (Fig. 2d) and the differential impact of the TFs on RAS-OIS-associated enhancer activation as predicted in the TF network analysis (Fig. 6a; see also the Cytoscape interactive maps hosted on Zenodo, Code availability statement).

We conclude that the senescence response is encoded by a universal three-layered TF network architecture and relies strongly on the exploitation of an enhancer landscape implemented by AP-1 pioneer TFs to choreograph the OIS transcriptional programme via local, diverse and dynamic interactions with settler and migrant TFs.

Hierarchy matters: Functional perturbation of the AP-1 pioneer TF, but no other TF, reverts the senescence clock.

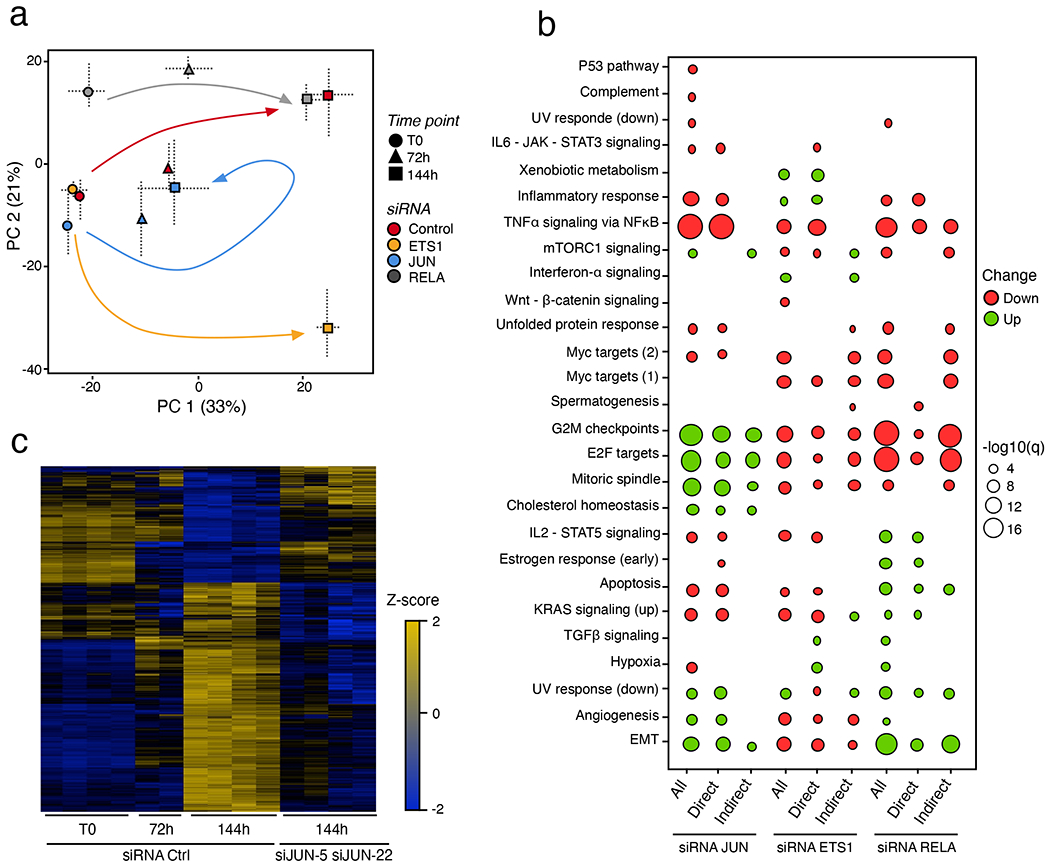

Pioneer TFs represent attractive targets to manipulate cell fate for diverse research and therapeutic purposes31. Accordingly, we depleted the pioneer TF cJUN and the settler TFs ETS1 and RELA at T0, 72 h and 144 h following oncogenic RAS expression using two independent siRNAs per TF (Extended Data Fig. 7e–g) and then compared global gene expression profiles with siControl-treated cells (Fig. 7a–c). Capturing their transcriptional trajectories using PCA (Fig. 7a) illustrated that functional perturbation of ETS1 and RELA shifted trajectories along the second principal component (PC2, which captures siRNA-related variability) at any given time point compared with the control time course. However, it did not affect the timely execution of the RAS-OIS gene expression programme, since there was no shift along the first principal component (PC1, which captures time-related variability). By contrast, perturbing cJUN function shifted trajectories both along PC1 and PC2 and effectively reverted the RAS-OIS transcriptional trajectory to a profile closely related to that of siControl-treated fibroblasts at 72 h after RAS-OIS induction. Silencing cJUN expression at 72 h also pushed the transcriptional profile closer to control-treated cells at T0 (Fig. 7a, blue arrow). Functional over-representation analyses of the target genes (direct and/or indirect) of each TF further supported the siRNA cJUN-mediated reversion of the RAS-OIS transcriptional trajectory, which demonstrates that depletion of cJUN leads to a repression of the inflammatory response (that is, the SASP) and a partial reactivation of pro-proliferation genes (that is, E2F, G2M and mitotic spindle targets) (Fig. 7b; Extended Data Fig. 8a–c).

Fig. 7 |. Hierarchy matters: Functional perturbation of the AP-1 pioneer tF, but no other tF, reverts the senescence clock.

a, PCA of transcriptomes obtained from siRNA-mediated depletion of cJUN, ETS1 or RELA at indicated time points for the RAS-OIS time course in WI-38 fibroblasts. Horizontal and vertical bars show minimal and maximal coordinates for each siRNA and time point on PC1 and PC2. The average of two independent transfections per time point per siRNA are shown. b, Functional over-representation map showing MSigDB hallmark pathways associated with all, direct target and indirect target genes differentially expressed after siRNA-mediated cJUN, ETS1 or RELA depletion. Genes are considered as direct targets when a PIQ prediction for the given TF falls inside an enhancer associated with this specific gene. Promoters are excluded from the analysis. The size of circles is proportional to the −log10 q value based on the hypergeometric test obtained when testing for over-representation, and their colour denote whether the term is enriched for an upregulated or downregulated gene list. N = 5,089 genes for siRNA cJUN, N = 2,431 genes for siRNA ETS1, and N = 2,224 genes for siRNA RELA. c, Heatmap comparing gene expression profiles of siControl-treated cells at indicated time points of siRNA cJUN-treated (siJUN-5 and siJUN-22) RAS-OIS WI-38 fibroblasts at 144 h after RAS induction. Data are expressed as row Z-scores. Data shown in b and c were collected from two biologically independent experiments.

To quantify and visualize the temporal overlaps in differentially expressed genes between siRNA cJUN-treated and siControl-treated cells, we used an UpSet plot (Extended Data Fig. 8d) and expression heatmaps (Fig. 7c; Extended Data Fig. 9a–d). Congruent with a resetting of the senescence clock, a significant number of pro-proliferation E2F target genes (16.5%; for example, CCNB2 and CDCA8) were upregulated (Extended Data Fig. 9a), and NF-κB-regulated SASP target genes (for example, IL1B and IL6) were downregulated (37.5%) (Extended Data Fig. 9b) following cJUN knockdown. A subset of p53 target genes (37.5%) was dysregulated by cJUN knockdown, indicating a functional interaction between AP-1 and p53 (Extended Data Fig. 9c,e–f; Supplementary Table 7). cJUN-depleted RAS-OIS cells also shared a similar expression profile for a subset of genes (21.3%) of the Notch-1-intracellular-domain-induced senescence transcriptional signature32 (Extended Data Fig. 9d).

Altogether, these data identify AP-1 as a master regulator and molecular ‘time-keeper’ of senescence.

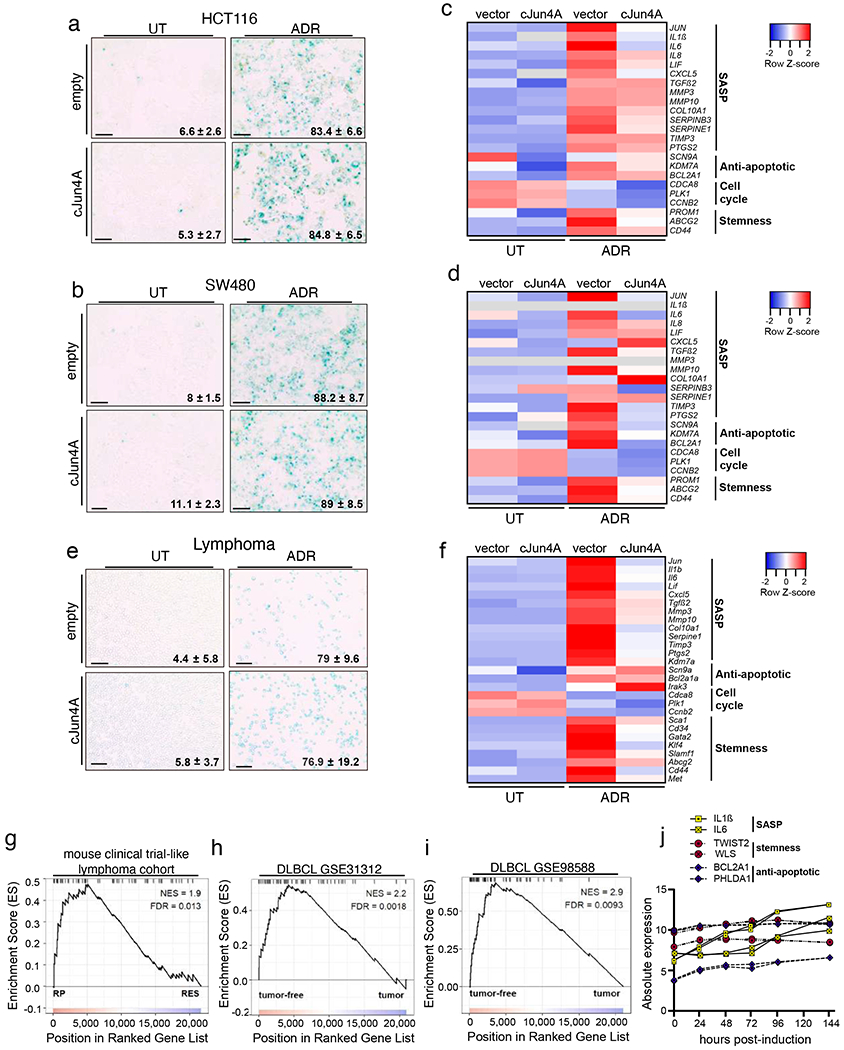

Functional role of AP-1 in TIS.

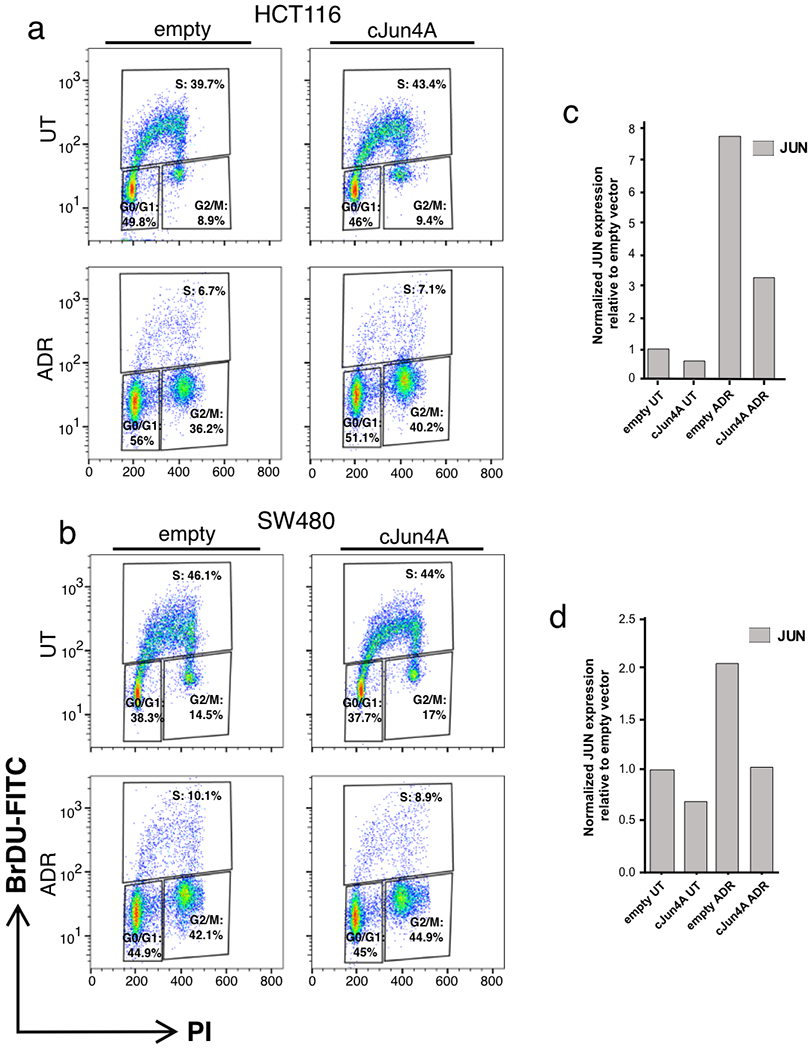

To extend our findings of AP-1 as a pioneering, master regulator of the senescence-associated gene expression programme in RAS-OIS, we investigated whether it also plays a decisive role during chemotherapy-induced senescence (that is, TIS) in vitro and in vivo. Accordingly, we first induced TIS by treating two colorectal cancer (CRC) cell lines, HCT116 and SW480, overexpressing either a non-phosphorylatable, dominant-negative isoform of cJUN (cJUN4A)33 or empty vector control with the chemotherapeutic agent Adriamycin (ADR). Expression of cJUN4A had no measurable effect on senescence inducibility (Fig. 8a,b; Extended Data Fig. 10a,b). However, it significantly blunted TIS-induced transcriptional upregulation of cJUN in both CRC cell lines, which is consistent with the role of cJUN driving its expression34 (Extended Data Fig. 10c,d). Next, we measured the expression of selected AP-1-dependent SASP, stemness-related, apoptosis-related and E2F target genes (Fig. 6b; Supplementary Table 8). This analysis revealed dramatic repression of SASP (for example, IL6, IL1B and MMP10), stemness (for example, LIF, ABCG2 and CD44) and anti-apoptotic (for example, BCL2A1) target genes in cJUN4A-expressing compared with empty vector, control cells (Fig. 8c,d). Of note, E2F target genes (for example, CCNB2 and CDCA8) remained repressed in cJUN4A-expressing CRC cell lines (Fig. 8c,d), which suggests that there are cell-type-dependent differences compared to our findings in RAS-OIS of fibroblasts.

Fig. 8 |. Functional role of AP-1 in tIS.

a,b, Representative SABG staining of HCT116 (a) and SW480 (b) CRC cell lines overexpressing cJUN4A or an empty vector as control and treated with ADR (100 ng ml−1) to undergo TIS or left untreated (UT). Indicated in each image is the mean percentage of SABG-positive cells ± s.e.m (n = 3 biologically independent lymphomas). Scale bars, 100 μm. c,d, Select AP-1 target gene expression (Supplementary Table 8) representative heatmap from two independent experiments, as determined by RT-qPCR, in HCT116 (c) and SW480 (d) CRC cell lines as in Fig. 8a,b. Grey blocks indicate transcript levels below detection. Data are expressed as row Z-scores. e, Representative SABG staining in primary lymphomas from Eμ-myc transgenic mice overexpressing cJun4A or an empty vector as control and treated with ADR (50 ng ml−1) to undergo TIS or left untreated. Indicated in each image is the mean percentage of SABG-positive cells ± s.d. (n = 3 independent experiments). Scale bars, 50 μm. f, Representative heatmap of transcript levels for select AP-1 target genes (Supplementary Table 8), as determined by RT-qPCR, under the conditions indicated in Fig. 8e. Data are expressed as row Z-scores. g-i, GSEA showing normalized enrichment score (NES) plots and FDR values for AP-1 senescence gene signature (Supplementary Table 9) enrichment in transcriptomes (GSE134751) of therapy-naive, initially therapy-sensitive, but destined to fail lymphomas (RP group, n = 19 mice) and their matched relapses (RES group, n = 16 mice) after three repetitive CTX treatments (300 mg per kg, intraperitoneally) (g), and in transcriptomes of samples from patients with DLBCL (GSE31312 (h) and GSE98588 (i)), profiled at diagnosis and classified into tumour-free and progressive-disease categories that is, tumour) based on disease status at last follow-up after standard (R)-CHOP treatment. For GSE31312, n = 293 tumour-free and n = 178 tumour samples. For GSE98588, n = 63 tumour-free and n = 37 tumour samples. Statistical evaluation of GSEA results was based on nonparametric Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, with FDR < 0.05 considered as statistically significant. j, Expression profiles of representative genes from the RAS-OIS time series used as input for GSEA (g-i). Data for the genes were collected from two biologically independent experiments (shown in Fig. 1e). Source data for f are provided.

To extend our findings to a primary tumour of different origin, we assessed the role of AP-1 in a well-established Eμ-myc transgenic mouse model of B cell lymphoma5. Consistent with the results in CRC cell lines, overexpression of cJun4A in primary murine B cell lymphomas (stably expressing Bcl2 to block apoptosis) did not affect TIS establishment in response to ADR treatment (Fig. 8e). By contrast, it actively repressed the expression of selected AP-1 target genes, similar to what we had observed in CRC cell lines undergoing ADR TIS (Fig. 8f).

Next, we probed the role of AP-1-dependent senescence in long-term outcome after anticancer therapy in vivo. To this end, we performed gene set enrichment analyses (GSEA), using an AP-1 senescence gene expression signature (Supplementary Table 9), first in a patient-reminiscent, primary Eμ-myc-lymphoma-based clinical-trial-like mouse cohort exposed to cyclophosphamide (CTX) in vivo. The AP-1 senescence gene expression signature was significantly enriched at diagnosis (that is, before any drug encounter) in lymphomas that initially responded to CTX treatment before eventually relapsing (designated ‘relapse-prone’ (RP)), which discriminated them clearly from the same set of lymphomas subsequently presenting as full-blown resistance to repetitive administrations of CTX (designated ‘resistant’ (RES)) (Fig. 8g). We then investigated whether a humanized version of this AP-1 senescence gene expression signature would be enriched in human diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) material obtained at diagnosis from patients achieving lasting tumour control tumour-free) in response to standard-care induction therapy with R-CHOP (CD20-specific antibody Rituximab plus CTX, ADR, vincristine and prednisone). Remarkably, two publicly available independent datasets (GSE31312 and GSE98588), comprising data on lymphoma transcriptomes at diagnosis and the clinical courses of patients with DLBCL, exhibited a highly significant enrichment for the AP-1 senescence gene signature in long-term tumour-free patients with DLBCL compared with those who relapsed after R-CHOP therapy Fig. 8h,i).

Collectively, our data emphasize the physiological importance of the AP-1-governed senescence-associated gene expression programme and highlight its contribution to the long-term outcome after anticancer therapy in vivo.

Exploiting senescence targeting for treating age-related diseases and cancer requires a detailed knowledge of the transcriptional, epigenetic and signalling mechanisms defining the basis and execution of the senescence programme, which is currently missing. To fill this critical gap in our knowledge, we used a dynamic, multidimensional approach at high resolution to define the gene-regulatory code driving senescence cell fate. A central finding of our study is that the senescence programme is defined and driven by a predetermined enhancer landscape that is sequentially (in)activated during the senescence process. AP-1 is instrumental for this predetermination by imprinting a prospective senescence enhancer landscape that, in the absence of traditional enhancer histone-modification marks, foreshadows future transcriptional activation. We stipulate that the senescence programme is preserved through AP-1 binding to enhancer chromatin as part of epigenetic memory of the developmental (stress) history of the cell. The pristine specificity of the identified prospective and remnant enhancers can be used as urgently needed specific, rather than associated, senescence biomarkers and to predict the potential of a cell to undergo senescence. Based on the data presented here and work in progress, we predict that the organizational principles of the senescence programme we defined here hold for all cell types and inducers.

Discussion

Another key finding is the reversibility of senescence by an informed intervention on network topology. Indeed, silencing the function of a single TF sitting on top of the TF network hierarchy, AP-1, is sufficient to partially revert the senescence clock. We surmise that AP-1 depletion does not lead to full cell cycle re-entry and proliferation because AP-1 plays important roles in proliferation35. However, we provide compelling evidence to indicate that AP-1 is critical for the expression of SASP genes both in different cell biology models of senescence and in an in vivo model of TIS (Figs. 7 and 8; Extended Data Figs. 8–10). Importantly, we demonstrated that an AP-1 senescence gene expression signature positively correlates with disease outcome after TIS in lymphomas, both in mouse and humans, thus emphasizing the importance of AP-1 in endowing cancer cells with the ability to undergo TIS in vivo. In summary, we believe that AP-1 is an actionable drug target for the therapeutic modulation of the senescence phenotype in vivo.

We showed that a highly flexible, combinatorial TF interactome establishes the senescence programme, which is in line with TF network dynamics during haematopoietic and stem cell differentiation36,37. In addition, we demonstrated that targeted engineering of specific nodes at different layers of the TF network disrupts gene expression with a corresponding magnitude, which suggests a path for the manipulation of the senescent phenotype in vivo. Pharmacological inhibition of TFs (see above for AP-1), signal transduction molecules, such as kinases or acetylases that converge in the activation of TFs, could represent a viable approach for manipulating the senescent phenotype in vivo38. Alternatively, small molecules that prevent TF-TF combinatorial interactions could also be envisioned39.

In conclusion, the present work emphasizes the advantages of integrating time-resolved genome-wide profiles to describe and interrogate the senescence cell fate, and provides inroads for the diagnosis and manipulation of the senescence state in age-related diseases and cancer.

Methods

Cell culture.

WI-38 fibroblasts (purchased from the European Collection of Authenticated Cell Cultures) were cultured in DMEM medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1× Primocin (Invivogen) at 37 °C and 3% oxygen. WI-38-ER:RASv12 fibroblasts were generated by retroviral transduction as previously described7. Senescence was induced by the addition of 400 nM 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT) to the culture medium, and samples were collected and processed at the time points indicated in the main text. GM21 skin fibroblasts were cultured using the same protocols as for WI-38 fibroblasts. GM21 skin fibroblasts constitutively expressing RASv12 or empty vector control were generated by retroviral transduction as previously described7. A doxycycline-inducible oncogenic BRAFV600E retroviral construct was a gift from C. Mann (CEA, Gif-sur-Yvette, France). RAF-OIS was induced in WI-38 fibroblasts with 100 ng ml−1 doxycycline, and cells were collected and processed at the time points indicated in the text. Replicative senescent cells were generated by proliferative exhaustion under 21% oxygen and were subsequently collected and processed at the indicated times in the main text. For the induction of quiescence, WI-38 fibroblasts were cultured in DMEM containing 0.2% FBS for up to four consecutive days, and samples were collected and processed as described in the main text. The CRC cell lines HCT116 (provided by A. Relogio) and SW480 (DSMZ, ACC-313) were transduced either with cJUN4A complementary DNA subcloned into MSCV-puro or empty vector control. HCT116 cells were cultured in DMEM (Gibco) and SW480 cells in RPMI-1640 (Gibco), supplemented with 10% FBS (Sigma) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Biochrom).

ATAC-seq.

The transposition reaction and library construction were performed as previously described17. Briefly, 50,000 cells from each time point of the senescence time course (two biological replicates) were collected, washed in 1× in PBS and centrifuged at 500 × g at 4 °C for 5 min. Nuclei were extracted by incubating cells in nuclear extraction buffer (containing 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 10 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 0.1% IGEPAL CA-630) and immediately centrifuging at 500 × g at 4 °C for 5 min. The supernatant was carefully removed by pipetting, and the transposition was performed by resuspending nuclei in 50 μl of Transposition Mix containing 1× TD Buffer (Illumina) and 2.5 μl Tn5 (Illumina) for 30 min at 37 °C. DNA was extracted using a Qiagen MinElute kit. Libraries were produced by PCR amplification (12–14 cycles) of tagmented DNA using a NEB Next High-Fidelity 2× PCR Master Mix (New England Biolabs). Library quality was assessed using an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100. Paired-end sequencing was performed in an Illumina Hiseq 2500. Typically, 30–50 million reads per library were required for downstream analyses.

Histone modification and TF ChIP-seq.

WI-38-ER:RASv12 fibroblasts were treated with 400 nM 4-OHT for 0, 72 and 144 h. Doxycycline-inducible BRAFV600E-expressing WI-38 fibroblasts were treated with 100 ng ml−1 doxycycline for 0, 48 and 96 h, and replicative senescent cells (0, 264, 1,008, 2,112 h) were generated as described above. A total of 1 × 107 cells (per time point, minimum two biological replicates) were fixed in 1% formaldehyde for 15 min, quenched in 2 M glycine for an additional 5 min and pelleted by centrifugation at 2,000 r.p.m., 4 °C for 4 min.

For histone modification ChIP-seq, nuclei were extracted in extraction buffer 2 (0.25 M sucrose, 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 10 mM MgCl2, 1% Triton X-100 and proteinase inhibitor cocktail) on ice for 10 min followed by centrifugation at 3,000 × g at 4 °C for 10 min. The supernatant was removed and nuclei were resuspended in nuclei lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 10 mM EDTA, 1% SDS and proteinase inhibitor cocktail). Sonication was performed using a Diagenode Picoruptor until the desired average fragment size (100–500 bp) was obtained. Soluble chromatin was obtained by centrifugation at 11,500 r.p.m. for 10 min at 4 °C, and chromatin was diluted tenfold. Immunoprecipitation was performed overnight at 4 °C with rotation using 1–2 × 106 cell equivalents per immunoprecipitation using antibodies (5 μg) against H3K4me1 (Abcam), H3K27ac (Abcam), H3K4me3 (Millipore; only used for RAS-OIS), H3K27me3 (Millipore; only used for RAS-OIS; antibodies are listed in the reporting summary). Subsequently, 30 μl of Ultralink Resin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was added and allowed to tumble for 4 h at 4 °C. The resin was pelleted by centrifugation and washed three times in low-salt buffer (150 mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 20 mM EDTA, 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0), one time in high-salt buffer (500 mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 20 mM EDTA, 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0), two times in lithium chloride buffer (250 mM LiCl, 1% IGEPAL CA-630, 15 sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0) and two times in TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA). For TF ChIP-seq, fibroblasts were treated as described above except that chromatin was isolated using an enzymatic SimpleChIP kit (Cell Signaling) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, obtaining chromatin with an average fragment length of four to five nucleosomes. Immunoprecipitation was performed overnight at 4 °C with rotation using 6–10 × 106 cell equivalents per immunoprecipitation using antibodies (5 μg) against cJUN, FOSL2 and RELA (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies; antibodies are listed in the reporting summary) and processed as described above. Washed beads were resuspended in elution buffer (10 mM Tris-Cl pH 8.0, 5 mM EDTA, 300 mM NaCl, 0.5% SDS) treated with RNAse H (30 min, 37 °C) and Proteinase K (2 h, 37 °C), 1 μl glycogen ( 20 mg ml−1, Ambion) was added and decrosslinked overnight at 65 °C. For histone modifications, DNA was recovered by mixing the decrosslinked supernatant with 2.2× SPRI beads followed by 4 min of incubation at room temperature. The SPRI beads were washed twice in 80% ethanol, allowed to dry, and DNA was eluted in 35 μl of 10 mM Tris-Cl pH 8.0. For TFs, DNA was eluted by phenolchloroform extraction (twice) followed by ethanol precipitation overnight at −20 °C. The DNA pellet was washed with 70% ethanol, allowed to dry, and DNA was resuspended in 35 μl of 10 mM Tris-Cl pH 8.0. Histone modification libraries were constructed using a NextFlex ChIP-seq kit (Bioo Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Libraries were amplified for 12 cycles. TF libraries were constructed using a modified protocol from the Accel-NGS 2S Plus DNA Library kit (21024), where we performed DNA extraction at each step using 25:24:1 phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol followed by overnight ethanol precipitation of DNA at each step of the protocol. Additionally, we enriched for small DNA fragments using AMPure-XP beads (Beckman-Coulter, A63881). Libraries were then resuspended in 20 μl of low EDTA-TE buffer. Libraries were quality controlled in an Agilent Technologies 4200 Tapestation (G2991-90001) and quantified using an Invitrogen Qubit DS DNA HS Assay kit (Q32854). Libraries were sequenced using an Illumina High-Seq 2500. Typically, 30–50 million reads were required for downstream analyses.

RNA and microarrays.

RNA from each time point from the different senescence models and quiescence time series, as well RAS-OIS cells treated with siControl and siRNAs targeting ETS1, RELA and cJUN (two biological replicates) was purified using the a Qiagen RNeasy Plus kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A total of 100 ng RNA per sample was analysed using Affymetrix Human Transcriptome Arrays 2.0, according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

EdU staining and senescence-associated beta galactosidase activity.

Representative samples from the senescent and quiescent time series were evaluated for EdU incorporation using a Click-iT EdU Alexa Fluor Imaging kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Senescence-associated beta galactosidase (SABG) activity was assessed as previously described40. Cells were imaged using a Zeiss confocal fluorescence microscope and images analysed using the ZEN suite.

RNA interference.

siRNAs (20 μM) targeting cJUN (Dharmacon), ETS1 (Qiagen) and RELA (Qiagen) as well as non-targeting controls were transfected into WI-38-ER:RASv12 using siIMPORTER reagent (Millipore) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (two biological replicates per TF per time course experiment). Transfections were performed in triplicate wells, and cells from each siRNA treatment were pooled for RNA purification. RAS-OIS was induced with 400 nM 4-OHT concomitantly with the addition of DMEM containing 20% FBS 4 h after transfection and incubated overnight. Sixteen hours after transfection, cells were replenished with new media containing 10% FBS and 400 nM 4-OHT, and RNA was isolated at indicated time points and analysed in Affymetrix Human Transcriptome Arrays 2.0.

CRISPRi.

hU6-gRNA-hUbc-dCas9-KRAB plasmid was a gift from C. Gerbach (Addgene, 71236). gRNA cloning was performed as previously published22. Briefly, the plasmid was digested with BsmBI and dephosphorylated before ligation with phosphorylated oligonucleotide pairs. The following gRNA sequences were used: Ctrl-caccgGTATTACTGATATTGGTGGG, aaacCCCACCAATATCAGTAATACc; 2-caccgAGATGAGGTGTTGCGTGTCT, aaacAGACACGCAACACCTCATCTc; 7-caccgTCTGCTCATTGGGGATCGGA, aaacTCCGATCCCCAATGAGCAGAc; 14-caccgAAGGCGAAGAAGACTGACTC, aaacGAGTCAGTCTTCTTCGCCTTc; 15-caccgCAATGAAATGACTCCCTCTC, aaacGAGAGGGAGTCATTTCATTGc; 48-caccgGGAGAACAGTCGCATGAACA, aaacTGTTCATGCGACTGTTCTCCc; 54-caccgTTCCAGGGAGTCACCTGTCC, aaacGGACAGGTGACTCCCTGGAAc; 61-caccgTTGAAGCAGCACTAGTATCC, aaacGGATACTAGTGCTGCTTCAAc. The plasmid was then transfected into HEK293T cells, together with the packaging plasmids psPAX2 and pMD2.G. After 24 h, fresh medium was added and the medium containing the lentivirus was collected and subsequently filtered. Cells were infected for 3 h. Three days after infection, cells were passaged and selected with puromycin and used for analyses.

Immunofluorescence staining and imaging of CRISPR-modified cells.

Immunofluorescence staining was performed as previously described41. Cells grown in 96-well plates were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton-X in PBS. After blocking, the cells were incubated with primary antibody (IL-1α, dilution 1:100, R&D MAB200; IL-1β, dilution 1:100, R&D MAB201; antibodies are listed in the reporting summary) for 1 h, and then Alexa Fluor secondary antibody for 30 min. Nuclei were counterstained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Imaging was carried out using IN Cell Analyzer 2000 (GE Healthcare) with the ×20 objective, and quantification was processed using IN Cell Investigator 3.7.2 software.

Quantitative reverse transcription PCR.

RNA was extracted with TRIzol (Ambion) and a RNAeasy Mini kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Reverse transcription was carried out using a SuperScript II RT kit (Invitrogen). Samples were analysed with SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) in a CFX96 Real-Time PCR Detection system (Bio-Rad). Ribosomal protein S14 (RPS14) was used as the housekeeping gene.

Quantitative PCR primers used in CRISPRi experiments were as follows: RPS14-CTGCGAGTGCTGTCAGAGG, TCACCGCCCTACACATCAAACT; IL1A-AGTGCTGCTGAAGGAGATGCCTGA, CCCCTGCCAAGCACACCCAGTA; IL1B-GGAGATTCGTAGCTGGATGC, AGCTGATGGCCCTAAACAGA. For RAS-OIS, RAF-OIS and RS gene expression profiling in WI-38 fibroblasts, Qiagen Quantitect primers were used using GAPDH expression as the housekeeping gene. For quantitative reverse transcription PCR (RT-qPCR) of CRC lines and lymphomas, RNA was transcribed into cDNA using SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) and oligo (dT) primers. RT-qPCR was performed using Taqman Gene Expression Master Mix and Taqman assays both Thermo Fisher Scientific), listed in Supplementary Table 8, on a StepOnePlus cycler (Applied Biosystems). GAPDH was used as the housekeeping gene.

Mouse strains and lymphoma generation.

All animal protocols used in this study were approved by the governmental review board (Landesamt Berlin), and conformed to the appropriate regulatory standards. C57BL/6 (wild type; 6–8 weeks old) female mice were used as recipients for in vivo lymphoma propagation. We generated Eμ-myc transgenic lymphomas with or without defined genetic defects in the Suv39h1 locus and with or without retroviral Bcl2 overexpression as previously described5,42,43. Eμ-myc/Bcl2 lymphomas were further stably transduced either with empty vector control or cJun4A mutant (murine cJun with non-phosphorylatable JNK target sites S63A, S73A, T91A and T93A)33,44. cJun4A was cloned by primer-extension-based site-directed mutagenesis from a wild-type murine cJun sequence, which was obtained by RT-PCR from lymphoma cDNA and subsequently subcloned into MSCV-IRES-GFP or empty vector control.

TIS protocol.

For TIS, ADR, a topoisomerase II inhibitor widely used in the clinic to treat lymphomas and other malignancies, was added once at a concentration of 0.05 μg ml−1 for Eμ-myc;Bcl2 lymphomas for a duration of 3 days and 0.1 μg ml−1 for CRC cell lines for a duration of 5 days. Senescence was assessed via SABG activity 2 days after drug removal, and standard cell cycle analysis was assessed using 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (FITC mouse anti-BrdU antibody, clone B44, BD Biosciences)/propidium iodide (BrdU/PI)-based flow cytometry measurement (FACS Calibur, BD Biosciences) as previously described40,42.

In vivo lymphoma drug treatment.

Individual lymphomas were propagated in up to two strain-matched, non-transgenic, fully immune-competent 6–8-week-old wild-type mice via the tail-vein injection of 1 × 106 viable cells. Recipient mice were treated with a single intraperitoneal dose of CTX (Sigma, 300 mg per kg body weight) when their lymphadenopathy became clearly palpable that is, about 8–10 mm in diameter). Treatment responses were monitored by inspection and lymph-node palpation at least twice a week for a maximum of a 100-day observation period, and documented as previously described43.

Gene expression profiling and data availability for mouse lymphomas.

RNA was isolated from lymphoma cells using a RNAeasy Mini kit (Qiagen) and hybridized to Affymetrix Mouse Gene 1.0 ST or Genome 430 2.0 microarrays according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Arrays were hybridized, washed and scanned according to standard Affymetrix protocols. The mouse model-derived raw microarray data—from our previously published control, Bcl2, Suv39h1−/−, Bcl2 and Suv39h1−/−, and Bcl2 transduced with 4OHT-inducible Suv39h1 (Suv39h1:ER/Bcl2) lymphomas5,43 were deposited into the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository of the National Center for Biotechnology Information under accession number GSE134753. Data from our clinical-trial-like model were deposited under accession number GSE134751. For assessing long-term outcome after in vivo treatments, seven or more tumour-bearing animals per group were used. Survival analysis was done using the survival package in R. Differential gene expression analysis was performed using limma and empirical Bayes statistics. To focus on single genes, probe sets without annotations were removed, and probe sets collapsed to the gene level using the probe set with highest statistical difference between senescent and non-senescent groups by an unpaired t-test before the analysis. P values were corrected for multiple testing using the Benjamini-Hochberg method to control for the false discovery rate FDR).

GSEA.

The “TIS_up_siJUN_down” gene list, referred to as the AP-1 senescence gene expression signature, was generated by intersecting genes downregulated by siRNA-mediated cJUN depletion in RAS-OIS fibroblasts (Supplementary Table 6; Fig. 6b; Extended Data Fig. 8a) and genes specific for TIS in Eμ-myc lymphomas (defined as differentially expressed genes in ADR-treated TIS-competent lymphomas, but not in equally treated TIS-incompetent lymphomas (GSE134753, GSE44355, and GSE31099)43, fold-change > 2.0; adjusted P < 0.01). The resulting list of 50 genes (Supplementary Table 9) was used to perform GSEA45 for three independent transcriptome settings: the transcriptome of native Eμ-myc lymphomas with known clinical outcome GSE134751) and cohorts of patients with DLBCL (GSE31312 and GSE98588)46,47. For the mouse transcriptome, the enrichment for the gene list was compared between therapy-naive, initially therapy-sensitive, but destined to fail lymphomas (RP group) and their matched relapses (RES group) after after three consecutive CTX treatments (300 mg per kg, intraperitoneally per relapse cycle). Samples from patients with DLBCL (all profiled at diagnosis) were classified into tumour-free and progressive-disease categories based on disease status at last follow-up after standard R-CHOP treatment. GSEA was performed using the R package clusterProfiler. Probe sets were collapsed to the gene level using the correlation-based approach48, whereby the correlation of probe sets representing the same gene was computed to decide whether to average probe sets (c > 0.2) or to use the probe set with the highest average expression across samples (c ≤ 0.2). Probe sets without known annotation were removed. The signal-to-noise ratio (μA - μB)/(σA + σB) (μ represents the mean, σ the standard deviation) was used as ranking metric and statistics based on gene set permutations. FDR q values of 0.05 were considered significant.

Statistics and reproducibility.

Quantitative data in graphs are presented as the mean ± s.d. or mean ± s.e.m. unless indicated otherwise in the figure legends. Statistical tests used in this study include unpaired bilateral Student’s t-test, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with associated one-sided Dunnett’s test, hypergeometric test, χ2 test and nonparametric Kolmogorov-Smirnov test as indicated in the figure legends. Significant differences are reported as P or FDR-corrected q values as indicated in the figure legends, and the exact values are indicated where appropriate. No statistical method was used to predetermine the sample size. Data derived from time-series microarray, ChIP-seq and ATAC-seq, siRNA microarray, primary lymphomas and CRC lines were highly reproducible. All transcriptomic and ChIP-seq assays were performed in biological duplicates (WI38 quiescence, RAS, RAF, RS and GM21 RAS). RAS-OIS ATAC-seq was performed in biological triplicates, and other ATAC-seq experiments were performed in biological duplicates.

Extended Data

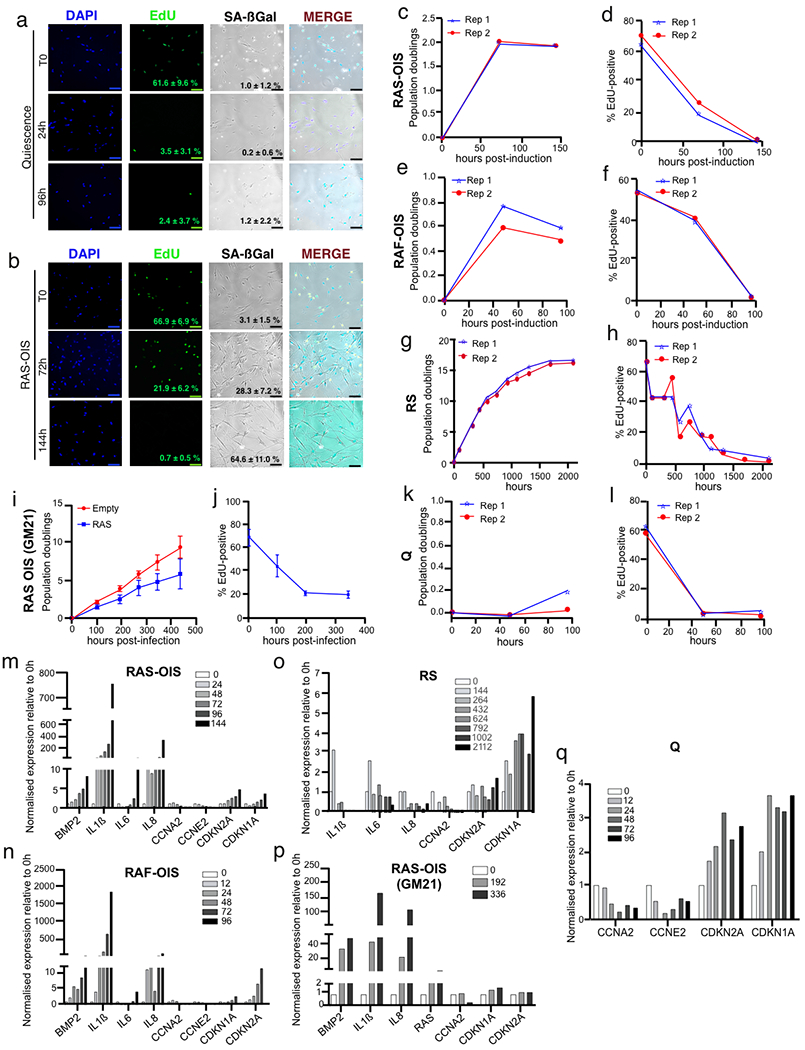

Extended Data Fig. 1 |. Multi-state establishment of the senescence transcriptional program.

a-b, Representative DAPI, EdU, SABG indirect fluorescence and phase contrast (from left to right) microscopy images of WI-38 fibroblasts undergoing RAS-OIS or quiescence at indicated time-points. Insets, mean percentage of SABG positive cells ± SD and proliferative capacity expressed as percent EdU-positive staining cells ± SD (biologically independent time-series). Scale bar, 100 μm. c-l, Growth and EdU incorporation curves for RAS-OIS (c-d), RAF-OIS (e-f), RS (g-h) in W38-, and RAS-OIS in GM21 skin fibroblasts (i-j) and quiescence in W38 fibroblasts (k-l) at indicated time-points (c-h, k-l; data shown represent average from 2 biologically independent experiments). For i-j, average + /− s.e.m. of n = 3 biologically independent experiments. m-q, RT-qPCR profiles for select target genes for each condition as in (c-l) (the experiment has been performed once). Statistical source data are presented in Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1.

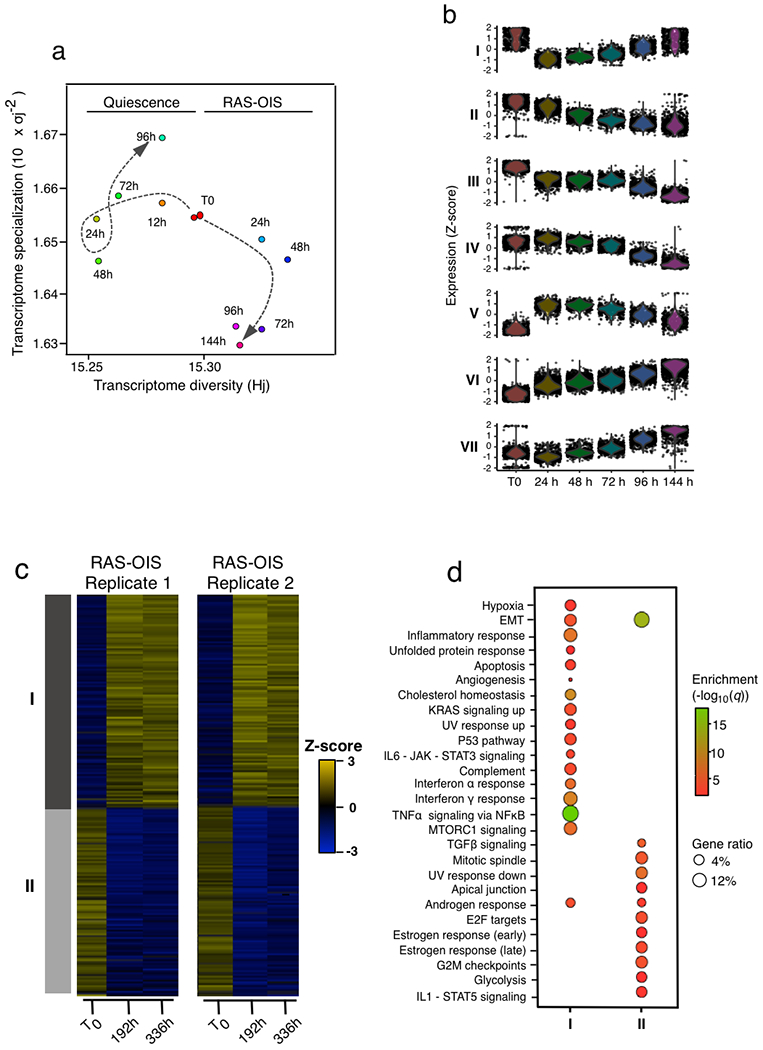

Extended Data Fig. 2 |. Multi-state establishment of the senescence transcriptional program.

a, Scatter plot depicting evolution of transcriptome diversity (Hj) vs. transcriptome specialization (σj) in cells undergoing Q or RAS-OIS in WI-38 fibroblasts. For each time-point and treatment, average Hj and σj values are given. T0 is start of time-course. b, Violin plots depicting gene expression profiles for each of RAS-OIS transcriptomic modules in WI-38 fibroblasts. Note the sharp transitions of modules I and V. Data are expressed as row Z-score. Data shown in (a) and (b) are from 2 biologically independent experiments. Single gene expression values are over-plotted. c-d, Heatmap of temporally co-expressed differentially regulated genes and associated functional overrepresentation of MSigDB hallmark gene sets for RAS-OIS in GM21 skin fibroblasts. Data shown represent 3 biologically independent experiments (c). N > 200 genes per transcriptomic module (d).

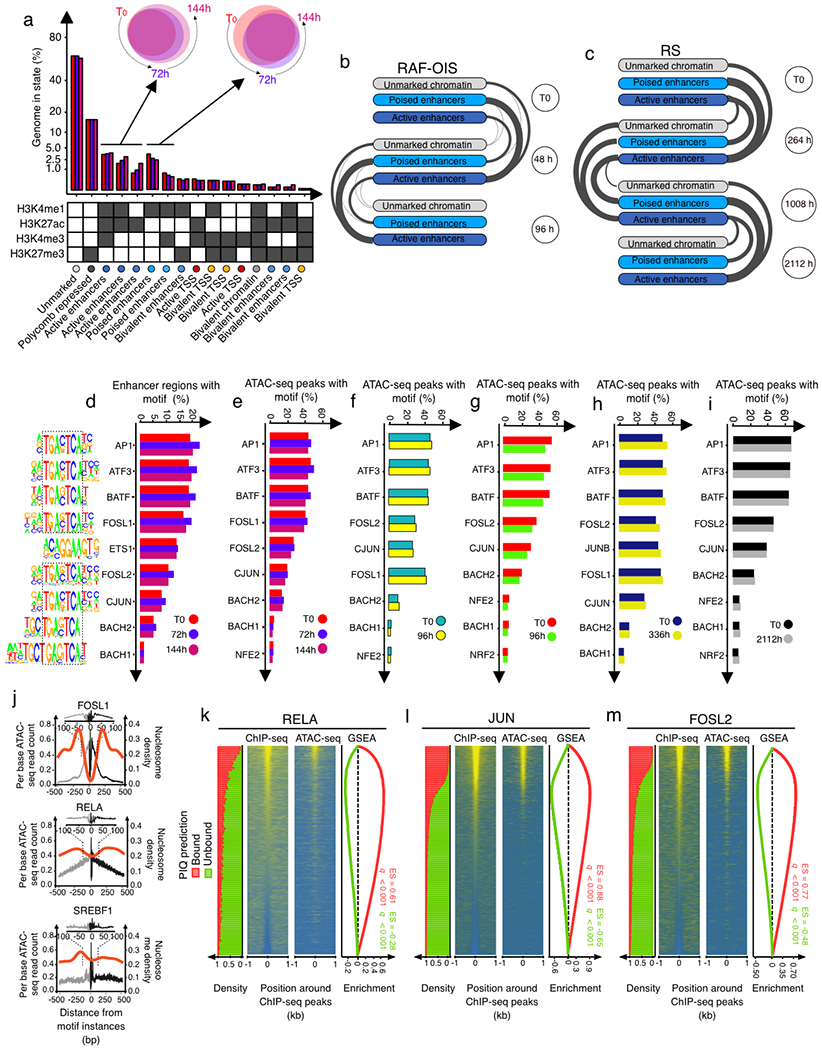

Extended Data Fig. 3 |. A dynamic enhancer program shapes the senescence transcriptome.

a, Genome Percentage covered by each chromatin state at indicated time-point. Bottom table assigns histone modification combinations (grey: presence, white: absence) to biologically meaningful mnemonics. Venn diagrams highlight specificities and overlaps in chromatin states associated with active (left) and poised enhancers (right) at indicated time points. Histogram depicts average state coverage across biological replicates collected from 2 biologically independent experiments. b-c, Arc plots visualizing dynamic chromatin state transitions for RAF-OIS and replicative senescence at indicated intervals. Edge width is proportional to number of transitions. Each arc plot depicts average transition landscape. d-i, Enriched sequence motifs in active enhancers for RAS-OIS in WI-38 fibroblasts (d) and (e-i) ATAC-seq peaks for RAS-OIS (WI-38) (e), RAF-OIS (WI-38) (f), RS (WI-38) (g), RAS-OIS (GM21 skin fibroblasts) (h) and quiescence (WI-38) (i) time-courses. Motif logos are shown. Black, dotted boxes highlight core AP-1 TF-motif. Note that transcriptional repressor BACH shares AP1-motif. Data in (b-i) are collected from 2 biologically independent experiments. j, ATAC-seq (grey lines-forward, black lines-reverse reads) and nucleosome density (red line) for AP-1 FOSL1 (pioneer), RELA (settler), and SREBF1 (migrant) in WI-38 fibroblasts undergoing RAS-OIS. Average footprints and nucleosome density collected from 3 biologically independent experiments are shown. k-m, Comparison between PIQ predictions and RELA (k), AP-1-JUN (l), and AP-1-FOSL2 (m) ChIP-seq profiles. Two density heatmaps at center of each panel illustrate ChIP-seq and ATAC-seq signals computed in 10 bp non-overlapping windows at selected bound- (25%) and unbound- (75%) predicted PWM hits ± 1 kb ranked according to ChIP-seq signal in the most central 100 bp. Stack histogram on left shows distribution of bound (red) and unbound (green) PWM hits as defined by PIQ along ranking. Curves on right depict evolution of enrichment score (ES) along ranking as defined with a Set Enrichment Analysis (SEA) comparing ChIP-seq signal and bound (red) and unbound (green) status of the PWM hit. 1,000 permutations were performed and the associated Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted p-value and ES score is provided (2 biologically independent experiments per condition).

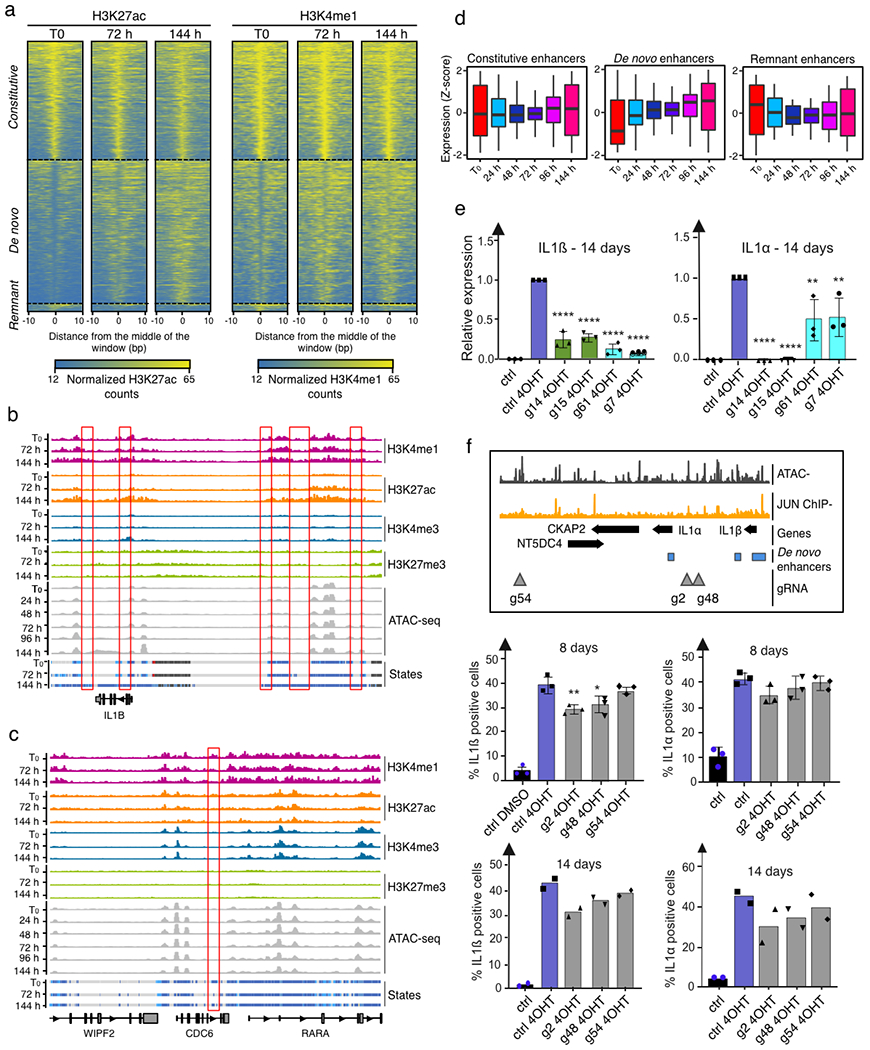

Extended Data Fig. 4 |. AP-1 pioneer tF bookmarking of senescence enhancer landscape foreshadows the senescence transcriptional program.

a, Density heatmaps of normalized H3K27ac and H3K4me1 ChIP-seq signals computed in 10 bp non-overlapping windows at enhancers + /− 10 kb grouped by enhancer status (constitutive, de novo or remnant) at indicated time-points after RAS-OIS induction in W38 fibroblasts. Each heatmap depicts average profile across replicates from 2 biologically independent experiments per histone modification and time-point. b-c, Representative genome browser screenshots of normalized H3K4me1 (pink), H3K27ac (orange), H3K4me3 (blue) and H3K27me3 (green) ChIP-seq and ATAC-seq (light grey) profiles and chromatin states at IL1β (b) and CDC6 (c) gene loci. Red boxes single-out IL1β de novo and CDC6 remnant enhancers. Each track depicts the average profile across replicates from 2 biologically independent experiments (ChIP-seq and ATAC-seq). d, Boxplots depicting distribution of relative gene expression (row Z-score) through time for genes associated with constitutive (left), de novo (middle) and remnant (left) enhancer windows. Thick horizontal lines depict medians. Lower and upper hinges correspond to first and third quartiles. Upper whisker extends from hinge to largest value no further than 1.5 * IQR from hinge (where IQR is inter-quartile range, or distance between first and third quartiles). Lower whisker extends from hinge to smallest value at most 1.5 * IQR of hinge. Each box depicts average expression distribution across replicates from 2 biologically independent experiments per time-point. e, RAS-OIS WI-38 fibroblasts at day 14 infected with dCas9-KRAB and individual guides (g14, g15, g61, and g7) and analyzed by RT-qPCR for IL1α or IL1β expression as described in Fig. 3b. Data represent mean ± SD (n = 3 biologically independent experiments). **p = 0.0037 (g61); p = 0.0069 (g7), ****p < 0.0001. Comparison with ctrl 4OHT, one-way ANOVA (one-sided Dunnett’s test). f, RAS-OIS WI-38 fibroblasts were infected with dCas9-KRAB and individual guides (g2, g48 and g54) for non-enhancer regions (outside de novo enhancers) as described in Fig. 3b. 8 or 14 days after infection, cells were stained for IL1α or IL1β by indirect immunofluorescence and percentage positive cells were quantified (n = 3 biologically independent experiments for 8 days and 2 biologically independent experiments for 14 days. Data represent mean ± SD. *p = 0.0107, **p = 0.0021. Comparison with ctrl 4OHT, one-way ANOVA (one-sided Dunnett’s test). Statistical source data are presented in Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4.

Extended Data Fig. 5 |. AP-1 pioneer tF bookmarking of senescence enhancer landscape foreshadows the senescence transcriptional program.

a, Rank plot depicting the summed occurrences for TFs binding in proliferating cells (T0) in de novo enhancers (left) and after replicative senescence in remnant enhancers (right). Top ten TFs are highlighted. TF footprinting was performed on pooled ATAC-seq datasets from 2 biologically independent time experiments. b, Metaprofiles showing density in “active enhancer”-flagged genomic bins (top) and “constitutive enhancer”-flagged genomic bins (bottom) in vicinity (± 50 kb) of TF bookmarked de novo (left) and TF virgin de novo enhancers (right). Density in “active enhancer”-flagged genomic bins is provided for indicated time-points. Chromatin states were defined from 2 biologically independent ChIP-seq. c, Boxplot showing correlation between absolute leading log2 expression fold-change and number of genomic bins flagged as “de novo” enhancers per enhancer. ***: p-value < 0.001, Student’s unpaired bilateral t-test considering regions with 0 “de novo” enhancers bins as a control. Thick horizontal lines depict medians. Lower and upper hinges correspond to first and third quartiles. Upper whisker extends from hinge to largest value no further than 1.5 * IQR from hinge (where IQR is the inter-quartile range, or distance between the first and third quartiles). Lower whisker extends from hinge to smallest value at most 1.5 * IQR of hinge. Each box depicts average absolute leading log2 expression fold-change distribution across 2 biologically independent time series. Statistics was derived for N > 200 genes per box.

Extended Data Fig. 6 |. A hierarchical tF network defines the senescence transcriptional program.

a, Circos plots summarizing pairwise transcription factor co-binding at enhancers for transcriptomic modules IV and VI at indicated time-points. Co-interactions involving AP-1 are shown in black. Selected examples of gained (green) and lost (orange) interactions are highlighted. Pioneer TFs (blue), settler TFs (red), migrant TFs (green). See also dynamic Circos plot movies in Supplementary Data (see under Code availability in Material and Methods). TF footprinting was performed on pooled ATAC-seq datasets from 3 biologically independent experiments. Plots show the average co-binding profiles across replicates. b, Heatmap showing the overlap between TF lexicons (rows) and chromatin states, ChIP-seq and ATAC-seq peaks (columns) collected from 2 biologically independent experiments. Dendrograms were computed by applying hierarchical clustering on the fraction matrix with Pearson’s correlation and average linkage. c, Representative genome browser screenshots for lexicons 22 and 50 as described in Fig. 5. Chromatin states are color-coded as in Fig. 2. Transcription factor binding instances constituting each lexicon are highlighted in inset. Representative of two independent ChIP-seq and ATAC-seq time-series with similar results. d, Ratio of incoming edges based on classification of TF source node. Relative and absolute number of edges corresponding to all seven modules are displayed inside nodes, which are colored accordingly to TF classification as in previous panels. Thickness of links is proportional to relative number of TF hierarchy edges connecting nodes with corresponding classification. e, Dynamicity index and number of bound regions for each TF (rows) across all gene modules (columns). Left heatmap depicts dynamicity index scaled by column, middle heatmap depicts the square root of number of bound regions scaled by column, and right single-column heatmap illustrates TF classification.

Extended Data Fig. 7 |. A hierarchical tF network defines the senescence transcriptional program.