Abstract

Background

Malnutrition in mothers as well as in children is a significant public health challenge in most of the developing countries. The triple burden of malnutrition is a relatively new issue on the horizon of health debate and is less explored among scholars widely. The present study examines the prevalence of the triple burden of malnutrition (TBM) and explored various factors associated with the TBM among mother-child pairs in India.

Methods

Data used in this study were drawn from the fourth round of the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-IV) conducted in 2015–16 (N = 168,784). Bivariate and binary logistic regression analysis was used to quantify the results. About 5.7% of mother-child pairs were suffering from TBM.

Results

Age of mother, educational status of the mother, cesarean section delivery, birth size of baby, wealth status of a household, and place of residence were the most important correlates for the triple burden of malnutrition among mother-child pairs in India. Further, it was noted that mothers with secondary education level (AOR: 1.15, CI 1.08–1.23) were having a higher probability of suffering from TBM, and interestingly the probability shattered down for mothers having a higher educational level (AOR: 0.90, CI 0.84–0.95). Additionally, mother-child pairs from rich wealth status (AOR: 1.93, CI 1.8–2.07) had a higher probability of suffering from TBM.

Conclusion

From the policy perspective, it is important to promote public health programs to create awareness about the harmful effects of sedentary lifestyles. At the same time, this study recommends an effective implementation of nutrition programs targeting undernutrition and anemia among children and obesity among women.

Keywords: Triple burden, Malnutrition, Mother-child pairs, NFHS, India

Background

The prevalence of malnutrition is declining around the world. Still, the world is home to around 155 million stunted children and 52 million wasted children [1]. Malnutrition is a major public health concern for the developing world, specifically India [2]. India continues to be the largest contributor to the global prevalence of malnutrition. Malnutrition can critically affect child growth and development, along with child survival. Malnutrition is one of the established causes of morbidity and mortality among children worldwide [3]. In technical terms, malnutrition is understood as “bad nutrition,” and it includes both over and undernutrition [4]. Countries are struggling with malnutrition on the one hand, and on the other hand, obesity is becoming a concern [5]. Since long obesity was considered a concern in a developed country, recently developing countries like India are also observing the high prevalence of obesity among children [5, 6] and mothers [7] due to rapid food habits and lifestyle changes. Previous studies have focused on the coexistence of obesity and undernutrition, i.e., the double burden of malnutrition. Researchers have explored various forms of the double burden of malnutrition; underweight and obesity among mothers [8, 9], obesity and thinness among children [10, 11], underweight and obesity among children [12, 13], underweight and obesity among mothers as well as children [7].

Recently, the double burden of malnutrition was accompanied by micronutrient deficiency [14]. Micronutrient deficiency is studied extensively in relation to anemia among children in India [15]. Anemia among children has been a significant health concern for a long and is one of the significant nutrition-related morbidities in developing countries [16]. It is estimated that 58% of the children aged 6–59 months were anemic in India [15]. As far as developing countries are concerned, India contribute significantly to child anemia [17, 18]. Few studies have highlighted the coexistence of the triple burden of malnutrition (TBM) in children, i.e., undernutrition, micronutrient deficiency, and obesity [19]. TBM has also co-existed at the household level where the mother was obese, and her children were found to be either anemic or undernourished; undernourishment was measured with stunting, underweight, and wasting [20].

Malnutrition in mothers as well as in children is a significant public health challenge in most of the developing countries. The triple burden of malnutrition is a relatively new issue on the horizon of healthy debate and is less explored among scholars widely. The double burden of malnutrition has been studied significantly in the developing world [21, 22], including India [7, 23], but the domain of triple burden is yet to be explored fully. Despite a rising coexistence of various forms of maternal and child malnutrition [1], studies related to the TBM are negligible. Even in the same household, the coexistence of undernutrition and obesity is often seen as paradoxical, but there are quite a few explanations for this paradox. As food resources become meagre, people tend to eat low-cost, unhealthy, and highly energy-dense foods, such choices lead to household members becoming overweight and undernourished at the same time [1]. Most countries experience multiple burdens of malnutrition, that are being expressed as a combination of undernutrition among children and obesity among adults [1]. Therefore, child undernutrition and adult obesity (overweight/obese mothers) form the pair to depict TBM in this paper. This study explores the coexistence of TBM among mother-child pairs residing in the same household. For this study, anemic and undernourished (either stunted or wasted or underweight child) children, along with obese mothers, formed the mother-child pairs for the TBM in a household. In previous studies, the triple burden was measured with a combination of anemic and undernourished children and obese women [20]. This study’s primary objective is to examine the prevalence of TBM and explore various factors associated with TBM in India.

Methods

This study’s data were drawn from the fourth round of the National Family Health Survey (NFHS) conducted in 2015–16, a cross-sectional national representative survey, to estimate the TBM and its associated factors among mother-child pairs. The NFHS 2015–16, conducted under the stewardship of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW) of India, provides detailed information on population, health, and nutrition, for India as a whole, as well as for each state (29) and union territory (7) and district (640). For selecting Primary Sampling Units (PSUs), the 2011 census served as the sampling frame. A more detailed methodology of the NFHS-4 has been published in the report [24]. This study used anthropometric indices such as height-for-age, weight-for-height, and weight-for-age and hemoglobin levels to evaluate children’s nutritional status below 5 years of age (0–59 months). Children suffering from stunting, wasting, and underweight was defined as children with Z-scores below − 2 standard deviation for height-for-age (HAZ), weight-for-height (WHZ), and weight-for-age (WAZ), respectively [20]. For this study, blood hemoglobin level was categorized as anemic (< 11 g/dl) and not anemic (> = 11 g/dl). In addition, the study used body mass index (BMI) of women and according to WHO cut-off values (underweight: < 18.5 kg/ m2; normal BMI: 18.5 to < 24.99 kg/m2 and overweight/obesity: > = 25.0 kg/m2) [24].

Outcome variables

First, this study dichotomized all the dependent variables into two categories: the presence of malnutrition was coded as ‘1’, and the absence of malnutrition was coded as ‘0’. The study made four different combinations of malnutrition, which were: overweight/obese mother and wasted child (OM/WC), overweight/obese mother and stunted child (OM/SC), overweight/obese mother and underweight child (OM/UC), and overweight/obese mother and anemic child (OM/AC) in the same household. Further, these four categories were combined and grouped into a single category: overweight/obese mother and undernourished child (stunting/wasting/underweight) who was also anemic, which was considered as the triple burden of malnutrition (TBM) [20].

Exposure variables

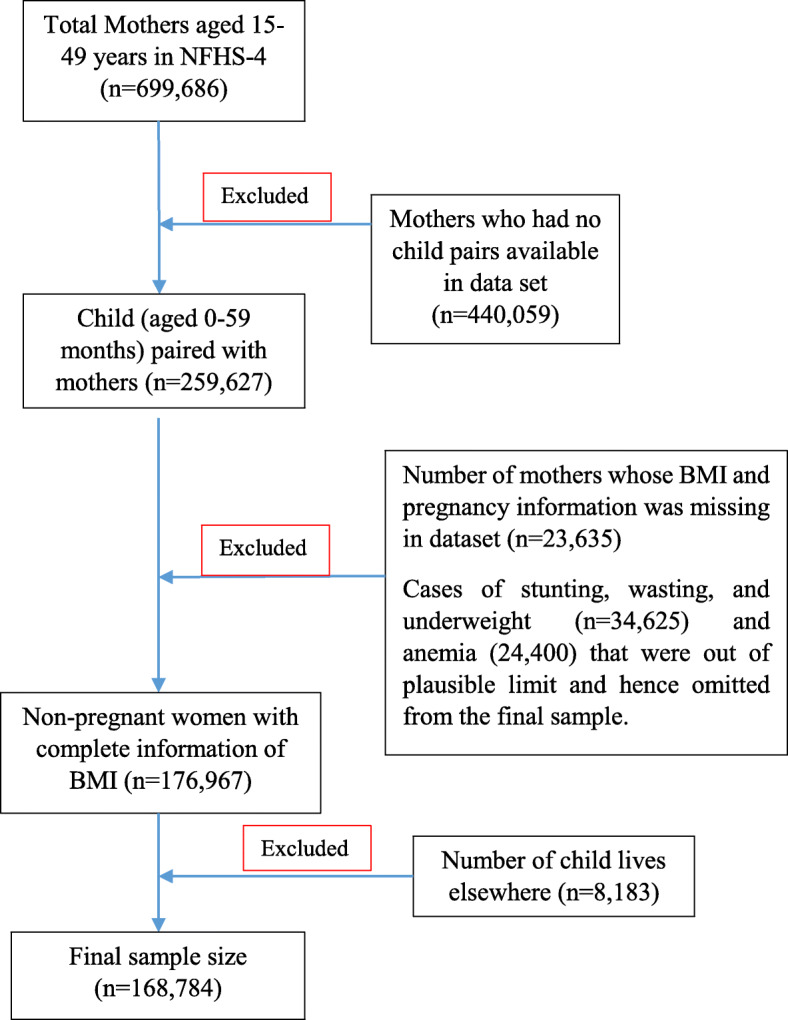

The independent variables included in this study were maternal, child, and household level factors. Mother’s factors included age (15–24, 25–34 and 35 years or more), age at first birth (less than 19, 20–29 and 30 years or more), educational level (no education, primary, secondary and higher), information on breastfeeding and cesarean section. Child level factors included child’s age (≤12, 13–23, 24–35, 36–47, and 48–59 months), sex of the child (male and female), received vitamin A and birth size of the child (average, smaller than average and larger than average). At last, household factors were categorized into the following parts; wealth index (poor, middle, and rich), Caste (Scheduled Caste, Scheduled Tribe, Other Backward Class and others), religion (Hindu, Muslim, and others), place of residence (rural and urban) and geographical regions (North, Central, East, Northeast, West, and South) of India. Figure 1 is showing the flow chart for sample size selection.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart for sample size selection

Statistical analysis

To identify the mother and child pairs in the same household, women and child file data sets were merged for the analysis. Bivariate and binary logistic regression analyses were applied to assess the factors associated with the triple burden of malnutrition [20]. In bivariate analysis, a chi-square test was also performed to assess socio-demographic factors’ association with the triple burden of malnutrition at the household level. This study included only those variables in the multivariate analysis, which were statistically significant (p < 0.05) in bivariate analysis. The adjusted odds ratio with a 95% confidence interval was also presented in the results.

Results

Table 1 represents the socio-demographic and other characteristics of the mother and children, 2015–16. It was found that 4.2%, 3.3%, 2.0%, and 7.8% of mother-child dyads were combinations of overweight and obese women with stunted (OM/SC), underweight (OM/UC), wasted (OMWC), and anemic children (OM/AC) respectively. Additionally, 5.7% of mother-child pairs were suffering from TBM, i.e., pairs were either (OM/SC) or (OM/UC) or (OM/WC) and (OM/AC). Nearly 3 in 10 mothers belong to the age group of 15–24 years. A total of 37% of mothers had age at first birth 19 years or less. Only about 1 in 10 mothers were having higher education. About 57% of mothers did not currently breastfeed, and 2 in 10 mothers went for a C-section method to deliver babies. Almost 22% of children were from the age group 48–59 months, and 14% were from the age group for 12 months or less. Nearly 47% of children were female, and 53% of them were male. Nearly 30% of the children did not receive vitamin A. Nearly 13% of the children were born smaller than the average size at birth. Nearly one-third of the households belonged to the rich wealth quintile.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic profile of mother-child pairs in India, 2015–16

| Variables | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| OM/SC | |

| Not stunted | 162,286 (95.8) |

| Stunted | 6498 (4.2) |

| OM/UC | |

| Not underweight | 163,988 (96.7) |

| Underweight | 4796 (3.3) |

| OM/WC | |

| Not wasted | 165,927 (98.0) |

| Wasted | 2857 (2.0) |

| OM/AC | |

| Not anemic | 156,702 (92.2) |

| Anemic | 12,082 (7.8) |

| TBM | |

| Normal | 160,198 (94.3) |

| OM/SC/WC/UC & AC | 8586 (5.7) |

| Mother level factors | |

| Age of the women (in years) | |

| 15–24 | 51,072 (32.6) |

| 25–34 | 101,665 (59.4) |

| > =35 | 16,047 (8.1) |

| Age at first birth (in years) | |

| < =19 | 58,881 (36.7) |

| 20–29 | 104,788 (61.0) |

| > =30 | 5115 (2.4) |

| Educational level | |

| No education | 49,762 (28.3) |

| Primary | 24,297 (13.9) |

| Secondary | 78,192 (46.9) |

| Higher | 16,533 (10.9) |

| Currently breastfeeding | |

| No | 94,147 (56.9) |

| Yes | 74,637 (43.1) |

| C-section delivery | |

| No | 144,101 (82.0) |

| Yes | 24,683 (18.0) |

| Child level factors | |

| Child’s age (in months) | |

| < =12 | 22,801 (13.5) |

| 13–23 | 33,654 (19.9) |

| 24–35 | 35,965 (21.4) |

| 36–47 | 38,725 (23.0) |

| 48–59 | 37,639 (22.3) |

| Sex of the child | |

| Male | 89,311 (53.0) |

| Female | 79,473 (47.0) |

| Received Vitamin A | |

| No | 54,891 (29.6) |

| Yes | 113,893 (70.4) |

| Size at birth | |

| Average | 117,136 (67.9) |

| Larger than average | 28,890 (19.3) |

| Smaller than average | 22,758 (12.8) |

| Household level factors | |

| Wealth index | |

| Poor | 80,427 (45.2) |

| Middle | 34,276 (20.1) |

| Rich | 54,081 (34.7) |

| Caste | |

| Scheduled Caste | 32,101 (21.7) |

| Scheduled Tribe | 31,922 (10.1) |

| Other Backward Class | 66,957 (44.1) |

| Others | 37,804 (24.1) |

| Religion | |

| Hindu | 124,060 (79.4) |

| Muslim | 25,541 (15.8) |

| Others | 19,183 (4.9) |

| Place of residence | |

| Urban | 42,041 (29.1) |

| Rural | 126,743 (70.9) |

| Region | |

| North | 32,733 (13.4) |

| Central | 48,169 (26.3) |

| East | 35,225 (25.6) |

| Northeast | 23,235 (3.5) |

| West | 12,001 (12.8) |

| South | 17,421 (18.4) |

OM/SC Overweight/obese mother and stunted child, OM/WC overweight/obese mother and wasted child, OM/UC overweight/obese mother and underweight child, OM/AC overweight/obese mother and anemic child and Trible burden of Malnutrition (OM/SC/WC/UC &AC), TBM Triple Burden of Malnutrition, C-section Caesarean section

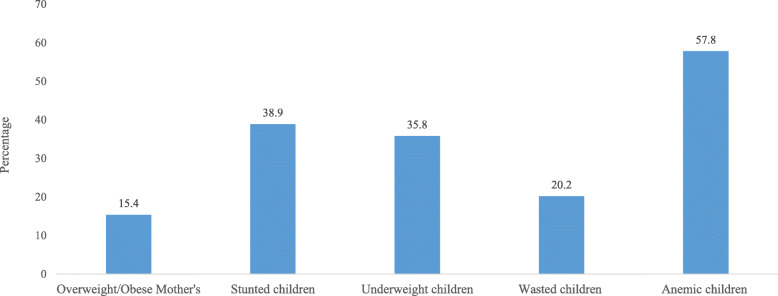

Figure 2 represents the percentage of the nutritional status of mothers and children in India. It was found that about 15.4% of women were overweight/obese. Nearly 38.9, 35.8, and 20.2% of children were stunted, underweight, and wasted, respectively. Almost 57.8% of children were anemic in India.

Fig. 2.

Percentage of nutritional status of the mothers and children in India, 2015–16

Table 2 presents results for the bivariate associations of background characteristics with TBM among mother-child pairs in India. TBM was highest among women who were more than 35 years (8.5%) of age than women in any other age group. Bivariate association indicates that TBM increases with age at first birth of mother, education level of mothers, child’s age, and wealth index. Among mothers with higher education levels, 8% of TBM was recorded. Current breastfeeding was another predictor of TBM; mothers who were currently breastfeeding had a lower prevalence of TBM. Cesarean-section (C-section) delivery is another predictor of TBM. The prevalence of TBM is nearly double when mothers had C-section delivery (9.8%) than when mothers had normal delivery (4.8%). TBM is lowest (4.2%) when the child’s age is equal to or less than a year than a child of any age group. Male children (5.8%) were having a higher burden of TBM than female children. Children whose birth size was larger than average were having a higher prevalence of TBM (6%) than children with any other birth size. Mother-child pairs which belong to the rich wealth quintile had the highest percentage of TBM (8.5%) than mother-child pairs of any other wealth quintile category. Mother-child pairs from another caste category (6.8%) and mother-child pairs that belong to the Muslim religion (7.8%) had a higher percentage of TBM than any other caste and religion category. Mother-child pairs from the urban place of residence had a higher prevalence of TBM (9%) than mother-child pairs from rural areas (4.3%). Mother-child pairs that belong to the southern region (8.6%) had the highest prevalence of TBM than mother-child pairs residing in any other region.

Table 2.

Bivariate associations of background characteristics with triple burden of malnutrition among mother-child pairs in India

| Variables | Triple Burden of Malnutrition (%) | Chi-square value (p-value) |

|---|---|---|

| Mother level factors | ||

| Age of the mother (in years) | ||

| 15–24 | 3.87 | 278.48 (0.0001) |

| 25–34 | 6.26 | |

| > =35 | 8.50 | |

| Age at first birth (in years) | ||

| < =19 | 4.71 | 101.82 (0.0001) |

| 20–29 | 6.10 | |

| > =30 | 9.26 | |

| Educational level | ||

| No education | 3.88 | 150.17 (0.0001) |

| Primary | 4.91 | |

| Secondary | 6.43 | |

| Higher | 7.97 | |

| Currently breastfeeding | ||

| No | 6.15 | 12.90 (0.0001) |

| Yes | 5.02 | |

| C-section delivery | ||

| No | 4.76 | 616.19 (0.0001) |

| Yes | 9.79 | |

| Child level factors | ||

| Child’s age (in months) | ||

| < =12 | 4.23 | 54.72 (0.0001) |

| 13–23 | 5.14 | |

| 24–35 | 5.60 | |

| 36–47 | 6.68 | |

| 48–59 | 6.01 | |

| Sex of the child | ||

| Male | 5.81 | 9.70 (0.0020) |

| Female | 5.50 | |

| Received Vitamin A | ||

| No | 4.93 | 35.60 (0.0001) |

| Yes | 5.98 | |

| Birth size | ||

| Average | 5.57 | 7.23 (0.0270) |

| Larger than average | 5.96 | |

| Smaller than average | 5.72 | |

| Household level factors | ||

| Wealth index | ||

| Poor | 3.04 | 1000 (0.0001) |

| Middle | 6.60 | |

| Rich | 8.55 | |

| Caste | ||

| Scheduled Caste | 5.34 | 292.21 (0.0001) |

| Scheduled Tribe | 2.88 | |

| Other Backward Class | 5.83 | |

| Others | 6.82 | |

| Religion | ||

| Hindu | 5.17 | 329.61 (0.0001) |

| Muslim | 7.80 | |

| Others | 6.82 | |

| Place of residence | ||

| Urban | 9.01 | 803.37 (0.0001) |

| Rural | 4.30 | |

| Region | ||

| North | 5.83 | 687.55 (0.0001) |

| Central | 5.02 | |

| East | 3.63 | |

| Northeast | 3.29 | |

| West | 7.33 | |

| South | 8.59 | |

C-section delivery Cesarean section delivery

Table 3 presents the result of multivariate logistic regression. Mothers whose age was 35 years and above were having a significantly higher likelihood of experiencing TBM than mothers from age group 15–24 years [AOR: 2.56, p < 0.01]. Mothers whose age at first birth was 30 years and above were 14% significantly less likely to suffer from TBM than mothers whose age at first birth was 19 years or less [AOR: 0.86, p < 0.01]. Mothers with educational status up to secondary level were 15% [AOR: 1.15, p < 0.01] more likely to suffer from TBM than mothers who had no education. Mothers who delivered through C-section had higher odds for suffering from TBM than mothers who had normal delivery [AOR: 1.57, p < 0.01]. Children aged 36–47 months had 67% more likely to suffer from TBM than children aged 1 year or less. Sex of the child and Vitamin A status did not have any significant association with TBM. Children whose birth size was smaller than average were 12% more likely to suffer from TBM than children with average birth size [AOR: 1.12, p < 0.01]. Mother-child pairs from the rich wealth quintile were 93% more likely to suffer from TBM than mother-child pairs from the poor wealth quintile [AOR: 1.93, p < 0.01]. Mother-child pairs from Scheduled Tribe were 25% less likely to suffer from TBM than mother-child pairs from other castes. Mother-child pairs from the Muslim religion were 58% more likely to suffer from TBM than mother-child pairs from the Hindu religion [AOR: 1.58, p < 0.01]. Women-child pairs from rural areas were 28% less likely to suffer from TBM than mother-child pairs from urban areas [AOR: 0.72, p < 0.01]. Mother-child pairs from the southern region were 41% more likely to suffer from TBM than mother-child pairs from the northern region [AOR: 1.41, p < 0.01].

Table 3.

Odds ratio for triple burden of malnutrition by background characteristic for mother-child pairs in India, 2015–16

| Variables | AOR (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Mother level factors | |

| Age of the mother (in years) | |

| 15–24® | |

| 25–34 | 1.65***(1.56–1.76) |

| > =35 | 2.56***(2.34–2.80) |

| Age at first birth (in years) | |

| < =19® | |

| 20–29 | 0.90***(0.85–0.95) |

| > =30 | 0.86**(0.76–0.97) |

| Educational level | |

| No education® | |

| Primary | 1.12***(1.04–1.22) |

| Secondary | 1.15***(1.08–1.23) |

| Higher | 1.04 (0.95–1.14) |

| Currently breastfeeding | |

| No | 0.90***(0.84–0.95) |

| Yes® | |

| C-section delivery | |

| No® | |

| Yes | 1.57***(1.49–1.66) |

| Child level factors | |

| Child’s age (in months) | |

| < =12® | |

| 13–23 | 1.24***(1.13–1.36) |

| 24–35 | 1.40***(1.28–1.54) |

| 36–47 | 1.67***(1.52–1.84) |

| 48–59 | 1.54***(1.39–1.70) |

| Sex of the child | |

| Male® | |

| Female | 0.97 (0.93–1.01) |

| Received Vitamin A | |

| No® | |

| Yes | 1.02 (0.97–1.07) |

| Birth size | |

| Average® | |

| Larger than average | 1.00 (0.95–1.06) |

| Smaller than average | 1.12***(1.04–1.19) |

| Household level factors | |

| Wealth index | |

| Poor® | |

| Middle | 1.79***(1.68–1.92) |

| Rich | 1.93***(1.8–2.07) |

| Caste | |

| Scheduled Caste | 1.11***(1.04–1.20) |

| Scheduled Tribe | 0.75***(0.68–0.82) |

| Other Backward Class | 1.04 (0.98–1.10) |

| Others® | |

| Religion | |

| Hindu® | |

| Muslim | 1.58***(1.49–1.67) |

| Others | 1.34***(1.24–1.46) |

| Place of residence | |

| Urban® | |

| Rural | 0.72***(0.68–0.76) |

| Region | |

| North® | |

| Central | 1.07**(1.04–1.15) |

| East | 0.83***(0.76–0.90) |

| Northeast | 0.86***(0.78–0.94) |

| West | 1.20***(1.10–1.31) |

| South | 1.41***(1.31–1.53) |

® References, AOR Adjusted Odds Ratio, CI confidence Interval

***if p < 0.01, **if p < 0.05, *if p < 0.1

C-section delivery Cesarean section delivery

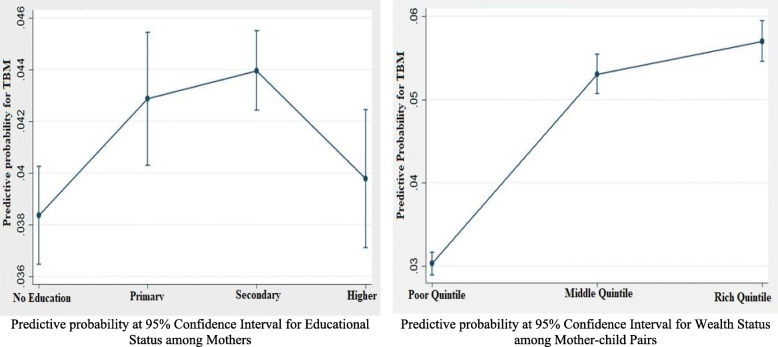

Figure 3 represents the predictive probability for selected socioeconomic covariates for TBM among mother-child pairs in India. The estimates were presented after controlling all the other background variables at their mean values (the estimates are obtained after the post-estimation command). It was found that mothers with secondary education level were having a higher probability of suffering from TBM, and interestingly the probability shattered down for mothers having a higher educational level. Additionally, mother-child pairs from rich wealth status had a higher probability of suffering from TBM.

Fig. 3.

Predictive probability for selected background characteristics for TBM among Mother-child pairs in India

Discussion

This study attempted to explore the coexistence of TBM among mother-child pairs in India. Overall, the TBM prevalence was 5.7% among mother-child pairs, which was lower than the 7% prevalence of TBM in Nepal [20]. The burden of malnutrition at the household level among mother-child pairs was 4.2% compared to pairing overweight or obese mothers with the stunted child only, which is higher than Nepal and Pakistan, lower than Myanmar, and equal to Bangladesh [25]. Another study found that the double burden of overweight/obese mothers and stunted children was 11 and 4% in rural Indonesia and rural Bangladesh, respectively [26]. Further, this study found that the burden of overweight/obese mothers and underweight children was 3.3%, overweight/obese mothers and wasted children were 2%, and overweight/obese mothers and anemic children were 7.8% in the same household.

Numerous studies have highlighted the risk factors for the double burden of malnutrition [25–28]; however, minimal literature is available in the public domain for TBM among mother-child pairs [20].

The study found that various maternal, child, and household factors were associated with TBM among mother-child pairs in India. The rising age of the mother is one of the prominent risk factors for TBM. Various studies have noted a positive association between increasing women’s age and the rise in obesity [29]. The high prevalence of obesity among mothers in the higher age group is the plausible reason for higher TBM among mothers of higher age. During later age, physical activity among women declines, along with the metabolic rate, leading to an increase in obesity. Furthermore, the energy requirement decreases; therefore, even regular or routine eating may lead to weight gain among women at later ages [30]. Moreover, newly-married women at a young age are more health-conscious and involved in more physical activity than women at older ages with children, which may further be attributed to obesity among women at later ages [31]. Increasing age in mothers is correlated with higher parity, which is another contributory factor for overweight and obesity [32]. Women gain weight during pregnancy, and weight loss does not occur in the post-partum period, which is another cause of obesity among women in a higher age group [33]. Another important finding relates TBM to the age of the mother at first birth. As age at first birth increases, the TBM among mother-child pairs decreases. Previous studies noticed an association between increasing the mother’s age at first birth and improving child undernutrition [34]. Child development has been linked to the mother’s age in various settings [35]. Studies have found that an increase in a mother’s age is associated with an increase in women’s autonomy, which positively affects child growth [36–38]. However, a study found that decision-making among women does not improve stunting or wasting among children [39]. Another study revealed that women with low acceptance in couple relations were less likely to have stunted or wasted children [40].

Mother’s education is another prominent covariate that has an association with TBM. Results concluded that primary and secondary level educated mothers were more likely to have a higher risk for TBM than uneducated mothers. However, anemia among children decreases with an increase in education among mothers [18], it is increasing in obesity prevalence with an increase in mother’s education [41] that is contributing to the higher levels of TBM among mother-child pairs [20]. The prevalence of obesity was higher among educated women than in uneducated women [42], contributing to increased TBM among highly educated women. Women with high education levels generally have higher wealth status than less-educated women [43], and higher wealth in a household is positively linked with higher odds of obesity among women [4]. C-section delivery is another contributory factor for TBM among mother-child pairs. Results showed that mothers who delivered a baby through C-section were more likely to suffer from TBM. It is widely studied that children born through C-section deliveries are less likely to be breastfed [44–46] and suffer from undernutrition [47]. It is further noted that mothers with C-section have difficulties with breastfeeding (Hobbs et al., 2016). Moreover, previous studies have commented that children who got delivered via C-section face early breastfeeding cessation [45, 46]. Furthermore, it is explored through previous studies that late initiation of breastfeeding due to C-section promotes poor child growth [45]. Few other studies have associated C-section deliveries with poor developmental growth outcomes among children [27, 47]. Moreover, C-section is also attributed to the increased risk of obesity among women [48]. All the above factors lead to higher TBM among mother-child pairs when the mother goes through C-section delivery.

Child’s age and birth size are the two child-related factors that were found to be significantly associated with the risk of TBM. Higher child age is associated with a high risk of TBM. Malnutrition among children increases with age [31] and can be attributed to higher TBM among them. Previous studies also highlighted that growth faltering among children is higher later [17]. A higher prevalence of stunting, wasting, and underweight at later ages is the plausible cause of the high risk of TBM among children at later ages. Not only undernutrition, but anemia is also higher among children in the high age group than children with lower age [49], thus confirming the high risk of TBM among children with a high age group. It is clearly understood that children aged above 1 year are at high risk of TBM than children below 1 year. As a child continues to grow after birth, the body grows rapidly and requires nutritious food that may not be fulfilled by regular diet, and hence children are more anemic, stunted, and underweight as they grow [49]. Smaller than average birth size is positively associated with the risk of TBM. Previous studies have attributed the low birth weight to stunting, wasting, and underweight [50, 51]. A study found that children with low birth weight were at 20% higher risk of being stunted [52]. Low size at birth is associated with a smaller amount of fundamental development supplements; nutrients A, zinc, and iron [53]. Thus, low birth weight babies were more malnourished as compared to high birth weight babies.

This study found that the TBM is higher among wealthier households than in poor households. As TBM was measured by creating mother-child pairs, it is crucial to understand what contributes to higher TBM in more affluent households; is it undernutrition and anemia among children or obesity among mothers? Studies have concluded that obesity is higher among richer women than in poor women [54, 55], and undernutrition and anemia among children are higher among poor children than in richer children [56]. Therefore, it is understood from the available literature that a higher prevalence of obesity among women in richer households is contributing to the TBM among mother-child pairs. It is a well-established notion that people in wealthier households tend to follow a sedentary lifestyle and are engaged in less labour intensive work, and consume more energy due to greater purchasing power; all of these lead to higher rates of obesity among them [57]. Contrary, it was also confirmed that low socioeconomic status might be related to limited food intake and combined with high manual labor, leading to a negative energy intake contributing to low TBM among women from poor households [58]. Consuming high energy-dense foods among mother-child pairs from wealthier households may be another reason for higher TBM among them than mother-child pairs from poor households, as previous studies have indicated that consuming high energy-dense food may well be attributed to obesity among women [59]. Results elaborated that TBM was lower among mother-child pairs belonging to Scheduled Tribes. Previous studies are also in line with noticing a higher prevalence of underweight and lower prevalence of overweight/obesity among the ST groups [59]. This may be explained by the situation of the tribe population, being primarily exposed to discrimination and a socioeconomically disadvantaged group [60].

The study found that TBM is higher among mother-child pairs in urban areas than in rural areas. Urban women have higher levels of obesity than their rural counterparts [29]; thus, TBM is higher among mother-child pairs in urban areas than in rural areas. Urbanization impacts the way of life, thus increasing the obesity levels among women in urban areas [61]. Sedentary behaviors and inadequate physical activity have been documented as risk factors for overweight/obesity among women residing in urban areas [62]. Moreover; western culture has long lasted impacts on obesity in urban India because of the opening of several fast-food chains and stalls across the cities [29]. The result noted a higher prevalence of TBM in Southern and Western regions than in India’s Northern region. It is evident from previous studies that education and wealth status in the Southern and Western regions are higher than in the Northern region (Chandra, 2019). Higher wealth and education, as discussed above, can explain the high risk of TBM among mother-child pairs in Southern and Western regions.

The study has several strengths. The anthropometric measures such as height and weight used to calculate BMI for mothers were measured with standard procedures by a team of highly trained investigators. Since the survey has a large sample size, the findings can be generalized to all households in India. As studies have highlighted the issue of post-pregnancy weight gain among mothers [63], this study dropped those mothers from the sample who delivered a baby in the last 2 months. Moreover, this study also dropped pregnant mothers’ cases with previous birth histories as weight gain during pregnancy is a well-researched phenomenon [64]. Despite several strengths, this study has some noteworthy limitations. Firstly, this study could not establish a plausible causal pathway of the association between explanatory and dependent variables and add only to the studies related to TBM’s prevalence and factors. Furthermore, the nutritional status of the mother was assessed using BMI only. Methods such as waist-hip ratio, bioelectrical impedance technique, DESA, and skinfold thickness are more accurate than BMI to assess overweight/obesity [20].

Conclusion

The study is important in highlighting the risk factors for TBM among mother-child pairs in India. This study highlights the issue of TBM by measuring undernourishment (stunting, wasting, and underweight) and anemia among children and overweight/obesity among women in the same households. At first, further research is needed to identify the causes and associated risk factors of TBM. On one side, a household is suffering from undernutrition and anemia among children, while on the other side, the same household is also suffering from overweight/obesity among mothers. The study found that the TBM exists among mother-child pairs in India. Various factors were associated with TBM among mother-child pairs, namely: age of the mother, age at first birth, education level of the mother, Child age, wealth index, place of residence, and regions of residence. There is a need for policies and scaled-up programs to provide nutritional education so that people start understanding the value of nutritious food and start investing in nutritious food choices. Food security and nutrition policies and programs must consider the specific needs and priorities of mother and children separately and target interventions in a gender-responsive way that leaves no one behind. Nutrition programs shall target undernutrition and anemia among children and obesity among women in the same household. It is important to promote public health programs that aim to create awareness about the harmful effects of sedentary lifestyles. Isolated focus on either undernourished children or overweight/obese women may not be adequate, and it is suggested to tackle different nutritional problems at the same time. There is a pressing need to implement nation-wide maternal health promotion interventions and nutrition education programs, which would be a good strategy to prevent overweight/obesity among women and undernutrition among children under 5 years of age in India. Promoting mutually inclusive nutrition interventions shall be the priority as TBM is higher among the wealthier families.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- TBM

Triple Burden of Malnutrition

- NFHS

National Family Health Survey

- FAO

Food and Agriculture Organization

- UNICEF

United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund

- MoHFW

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare

- PSU

Primary Sampling Unit

- CEB

Census Enumeration Block

- PPS

Probability Proportional to Size

- IIPS

International Institute for Population Sciences

- HAZ

Height-for-Age

- WHZ

Weight-for-Height

- WAZ

Weight-for-Age

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- WHO

World Health Organization

- OM

Overweight/Obese Mother

- SC/UC/WC/AC

Stunted Child/Underweight Child/ Wasted Child/ Anemic Child

- C-Section

Cesarean Section

- AOR

Adjusted Odds Ratio

Authors’ contributions

The concept was drafted by SS; PK and SS contributed to the analysis design. PK, SC, and SS advised on the paper and assisted in paper conceptualization. SC and RP contributed to the comprehensive writing of the article. This work was carried out under the supervision of DWB. DWB edited the manuscript and revised it critically. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Author’s information

Pradeep Kumar completed his M.Phil in Population studies and currently pursuing his PhD in Population studies from International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai, India. His area of interest is Ageing, maternal and child health, and adolescent health issues in India.

Shekhar Chauhan completed his MA in Population studies and currently pursuing his Ph.D. in Population studies from International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai, India. His area of interest is early marriage among men and public health issues in India.

Ratna Patel completed her M.Phil in Population studies and currently pursuing her Ph.D. in Population studies from International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai, India. Her area of interest is adolescent health and public health issues in India.

Shobhit Srivastava completed his M.Phil in Population studies and currently pursuing his PhD in Population studies from International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai, India. His area of interest is ageing and Mental Health issues including issues of malnutrition among older adults.

Dr. Dhananjay W. Bansod is professor at International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai, India. His area of Interest is Population Ageing, Public Health and Large Scale Survey Research.

Funding

Authors did not receive any funding to carry out this research.

Availability of data and materials

The study utilizes secondary sources of data that are freely available in the public domain through https://dhsprogram.com/methodology/survey/survey-display-355.cfm. Those who wish to access the data may register at the above link and thereafter can download the required data free of cost.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The data is freely available in the public domain. Survey agencies that conducted the field survey for the data collection have collected prior consent from the respondent. The local ethics committee of the International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS), Mumbai, ruled that no formal ethics approval was required to carry out research from this data source.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Pradeep Kumar, Email: pradeepiips@yahoo.com.

Shekhar Chauhan, Email: shekhariips2486@gmail.com.

Ratna Patel, Email: ratnapatelbhu@gmail.com.

Shobhit Srivastava, Email: shobhitsrivastava889@gmail.com.

Dhananjay W. Bansod, Email: dhananjay@iips.net

References

- 1.FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP W . The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2017. Rome FAO: Building resilience for peace and food security; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pal A, Pari AK, Sinha A, Dhara PC. Prevalence of undernutrition and associated factors: a cross-sectional study among rural adolescents in West Bengal, India. Int J Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2017;4(1):9-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Lahariya C. State of the world’s children 2008. Indian Pediatr:2008. [PubMed]

- 4.Patel R, Srivastava S, Kumar P, Chauhan S. Factors associated with double burden of malnutrition among mother-child pairs in India: A study based on National Family Health Survey 2015–16. Child Youth Serv Rev [Internet] 2020;116:105256. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pathak S, Modi P, Labana U, Khimyani P, Joshi A, Jadeja R, et al. Prevalence of obesity among urban and rural school going adolescents of Vadodara, India: a comparative study. Int J Contemp Pediatr [Internet] 2018;5(4):1355. doi: 10.18203/2349-3291.ijcp20182480. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jomi J, Sushama B, Vijayaraghavan R. Dietary pattern and prevalence of overweight & obesity among children aged 6–11 years in southern part of Kerala, India-a pilot study. Int J Nurs Educ. 2018;10(4):68-72.

- 7.Malik R, Puri S, Adhikari T. Double burden of malnutrition among mother-child DYADS in urban poor settings in India. Indian J Community Health. 2018;30(2).

- 8.Kulkarni VS, Kulkarni VS, Gaiha R. “Double Burden of Malnutrition” Reexamining the Coexistence of Undernutrition and Overweight Among Women in India. Int J Health Serv. 2017;47(1):108-133. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Sengupta A, Angeli F, Syamala TS, Van Schayck CP, Dagnelie P. State-wise dynamics of the double burden of malnutrition among 15–49 year-old women in India: how much does the scenario change considering Asian population-specific BMI cut-off values? Ecol Food Nutr. 2014;53(6):618-38. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Mondal N, Basumatary B, Kropi J, Bose K. Prevalence of double burden of malnutrition among urban school going bodo children aged 5–11 years of Assam, Northeast India. Epidemiol Biostat Public Health. 2015;12(4).

- 11.Bisai S, Khongsdier R, Bose K, Mahalanabis D. Double burden of malnutrition among urban Bengalee adolescent boys in Midnapore, West Bengal, India. Nat Preced. 2012;1-1.

- 12.Darling AM, Fawzi WW, Barik A, Chowdhury A, Rai RK. Double burden of malnutrition among adolescents in rural West Bengal, India. Nutrition. 2020;110809. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Ahmad S, Shukla N, Singh J, Shukla R, Shukla M. Double burden of malnutrition among school-going adolescent girls in North India: a cross-sectional study. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2018;7(6):1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Awasthi S, Reddy NU, Mitra M, Singh S, Ganguly S, Jankovic I, Ghosh A. Micronutrient-fortified infant cereal improves hemoglobin status and reduces iron deficiency anemia in Indian infants: an effectiveness study.. Br J Nutr. 2020;1-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Sharma H, Singh SK, Srivastava S. Socio-economic inequality and spatial heterogeneity in anaemia among children in India: Evidence from NFHS-4 (2015–16). Clin Epidemiol Glob Heal [Internet]. 2020.

- 16.Khanal V, Karkee R, Adhikari M, Gavidia T. Moderate-to-severe anaemia among children aged 6-59 months in Nepal: An analysis from Nepal Demographic and Health Survey, 2011. Clin Epidemiol Glob Heal. 2016;4(2):57-62.

- 17.Headey D, Menon P, Nguyen P. The timing of growth faltering in India has changed significantly over 1992–2016, with variations in prenatal and postnatal improvement (P10-005-19). Curr Dev Nutr. 2019;3(Supplement_1):nzz034-P10.

- 18.Bharati S, Pal M, Bharati P. Prevalence of anaemia among 6- to 59-month-old children in India: the latest picture through the NFHS-4. J Biosoc Sci. 2020;52(1):97-107. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Jain A, Agnihotri SB. Assessing inequalities and regional disparities in child nutrition outcomes in India using MANUSH - a more sensitive yardstick. Int J Equity Health. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Sunuwar DR, Singh DR, Pradhan PMS. Prevalence and factors associated with double and triple burden of malnutrition among mothers and children in Nepal: Evidence from 2016 Nepal demographic and health survey. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Kadiyala S, Aurino E, Cirillo C, Srinivasan C, Zanello G. Rural transformation and the double burden of malnutrition among rural youth in low and middle-income countries. 2019.

- 22.Prentice AM. The double burden of malnutrition in countries passing through the economic transition. Ann Nutr Metab. 2018;72(3):47-54. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Constantinides S, Blake C, Frongillo E, Avula R, Thow AM. Double burden of malnutrition: the role of framing in development of political priority in the context of rising diet-related non-communicable diseases in Tamil Nadu, India (P22-005-19). Curr Dev Nutr. 2019;3(Supplement_1):nzz042-P22.

- 24.International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) & ICF. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4), 2015-16: India. Mumbai: IIPS. 2017.

- 25.Anik AI, Rahman MM, Rahman MM, Tareque MI, Khan MN, Alam MM. Double burden of malnutrition at household level: a comparative study among Bangladesh, Nepal, Pakistan, and Myanmar. PLoS One. 2019;14(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Oddo VM, Rah JH, Semba RD, Sun K, Akhter N, Sari M, Kraemer K. Predictors of maternal and child double burden of malnutrition in rural Indonesia and Bangladesh. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95(4):951-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Das S, Fahim SM, Islam MS, Biswas T, Mahfuz M, Ahmed T. Prevalence and sociodemographic determinants of household-level double burden of malnutrition in Bangladesh. Public Health Nutr. 2019;22(8):1425-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Onyeji GN, Sanusi RA. Prevalence of stunted child overweight mother pair in some communities south-East Nigeria. Niger J Nutr Sci. 2019;40(2):94-8.

- 29.Chaurasiya D, Gupta A, Chauhan S, Patel R, Chaurasia V. Age, period and birth cohort effects on prevalence of obesity among reproductive-age women in India. SSM - Popul Heal. 2019;9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Gouda J, Prusty RK. Overweight and obesity among women by economic stratum in urban India. J Health Popul Nutr. 2014;32(1):79–88. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Sinha RK, Dua R, Bijalwan V, Rohatgi S, Kumar P. Determinants of stunting, wasting, and underweight in five high-burden pockets of four Indian states. Indian journal of community medicine: official publication of Indian Association of Preventive & Social Medicine. 2018;43(4):279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Li W, Wang Y, Shen L, Song L, Li H, Liu B, et al. Association between parity and obesity patterns in a middle-aged and older Chinese population: a cross-sectional analysis in the Tongji-Dongfeng cohort study. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2016;13:72. 10.1186/s12986-016-0133-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Bhavadharini B, Anjana RM, Deepa M, Jayashree G, Nrutya S, Shobana M, Rekha K. Gestational weight gain and pregnancy outcomes in relation to body mass index in Asian Indian women. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2017;21(4):588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Singh SK, Srivastava S, Chauhan S. Inequality in child undernutrition among urban population in India: a decomposition analysis. BMC Public Health [Internet] 2020;20(1):1852. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09864-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hanly M, Falster K, Banks E, Lynch J, Chambers GM, Brownell M, Jorm L. Role of maternal age at birth in child development among indigenous and non-indigenous Australian children in their first school year: a population-based cohort study. Lancet Child Adolesc Heal. 2020;4(1):46-57. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Ziaei S, Contreras M, Zelaya Blandón E, Persson LÅ, Hjern A, Ekström EC. Women’s autonomy and social support and their associations with infant and young child feeding and nutritional status: community-based survey in rural Nicaragua. Public Health Nutr. 2015;18(11):1979-90. 10.1017/S1368980014002468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Cunningham K, Ruel M, Ferguson E, et al. Women’s empowerment and child nutritional status in South Asia: a synthesis of the literature. Matern Child Nutri. 2015;11:1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Shroff MR, Griffiths PL, Suchindran C, et al. Does maternal autonomy influence feeding practices and infant growth in rural India? Soc Sci Med. 2011;73:447–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.McKenna CG, Bartels SA, Pablo LA, Walker M. Women’s decision-making power and undernutrition in their children under age five in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2019;14(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Agu N, Emechebe N, Yusuf K, Falope O, Kirby RS. Predictors of early childhood undernutrition in Nigeria: the role of maternal autonomy. Public Health Nutr. 2019;22(12):2279-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Rai RK, Jaacks LM, Bromage S, Barik A, Fawzi WW, Chowdhury A. Prospective cohort study of overweight and obesity among rural Indian adults: Sociodemographic predictors of prevalence, incidence and remission. BMJ Open. 2018;8(8):e021363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Luhar S, PAC M, Clarke L, Kinra S. Trends in the socioeconomic patterning of overweight/obesity in India: A repeated cross-sectional study using nationally representative data. BMJ Open [Internet] 2018;8(10):23935. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bloomberg L, Meyers J, Braverman MT. The Importance of Social Interaction: A New Perspective on Social Epidemiology, Social Risk Factors, and Health. Health Educ Quarterly. 1994;21(4):447-63. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Belachew A. Timely initiation of breastfeeding and associated factors among mothers of infants age 0-6 months old in Bahir Dar City, Northwest, Ethiopia, 2017: A community based cross-sectional study. Int Breastfeed J. 2019;14(1):5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Saaka M, Hammond AY. Caesarean section delivery and risk of poor childhood growth. J Nutr Metab. 2020;2020:6432754. 10.1155/2020/6432754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Chehab R, Nasreddine L, Zgheib R, Forman M. C-section delivery is a barrier to and demographic-maternal-child factors have mixed effects on the length of exclusive breastfeeding under nutrition transition in Lebanon (P11-058-19). Curr Dev Nutr. 2019;3(Supplement_1):nzz048-P11.

- 47.Islam MS, Biswas T. Prevalence and correlates of the composite index of anthropometric failure among children under 5 years old in Bangladesh. Matern Child Nutr. 2019;e12930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Turner D, Monthé-Drèze C, Cherkerzian S, Gregory K, Sen S. Maternal obesity and cesarean section delivery: additional risk factors for neonatal hypoglycemia? J Perinatol. 2019;39(8):1057-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Behera S, Bulliyya G. Magnitude of Anemia and hematological predictors among children under 12 years in Odisha, India. Anemia. 2016;2016:1729147. 10.1155/2016/1729147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Rahayu Diah Kusumawati M, Marina R, Endah Wuryaningsih C. Low Birth Weight As the Predictors of Stunting in Children under Five Years in Teluknaga Sub District Province of Banten 2015. KnE Life Sci. 2019;4(10):284–93. 10.18502/kls.v4i10.3731.

- 51.Aryastami NK, Shankar A, Kusumawardani N, Besral B, Jahari AB, Achadi E. Low birth weight was the most dominant predictor associated with stunting among children aged 12-23 months in Indonesia. BMC Nutr. 2017;3(1):16.

- 52.Black RE, Victora CG, Walker SP, Bhutta ZA, Christian P, de Onis M, Ezzati M, Grantham-McGregor S, Katz J, Martorell R, Uauy R, Maternal and Child Nutrition Study Group. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2013;382(9890):427-51. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60937-X. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Peter D. Gluckman, Catherine S. Pinal, Regulation of Fetal Growth by the Somatotrophic Axis. The Journal of Nutrition. 2003;133(5):1741S–6S. 10.1093/jn/133.5.1741S. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Al Kibria GM, Swasey K, Hasan MZ, Sharmeen A, Day B. Prevalence and factors associated with underweight, overweight and obesity among women of reproductive age in India. Glob Heal Res Policy. 2019;4(1):24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Neupane S, Prakash KC, Doku DT. Overweight and obesity among women: analysis of demographic and health survey data from 32 sub-Saharan African countries. BMC Public Health. 2015;16(1):30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Singh S, Srivastava S, Upadhyay AK. Socio-economic inequality in malnutrition among children in India: an analysis of 640 districts from National Family Health Survey (2015-16). Int J Equity Health. 2019;18(1):203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Bhurosy T, Jeewon R. Overweight and obesity epidemic in developing countries: a problem with diet, physical activity, or socioeconomic status? ScientificWorldJournal. 2014;2014:964236. 10.1155/2014/964236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Little M, Humphries S, Patel K, Dewey C. Factors associated with BMI, underweight, overweight, and obesity among adults in a population of rural South India: a cross-sectional study. BMC Obes. 2016;3:12. 10.1186/s40608-016-0091-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Pengpid S, Peltzer K. Prevalence and correlates of underweight and overweight/obesity among women in India: Results from the National Family Health Survey 2015–2016. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes Targets Ther [Internet] 2019;12:647–653. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S206855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Patel ML, Deonandan R. Factors associated with body mass index among slum dwelling women in India: An analysis of the 2005-2006 Indian national family health survey. Int J Gen Med. 2017;10:27–31. 10.2147/IJGM.S82912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 61.Nagarkar A, Kulkarni S. Obesity and its effects on health in middle-aged women from slums of Pune. J Midlife Health. 2018;9(2):79–84. 10.4103/jmh.JMH_8_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62.Ghose B. Frequency of TV viewing and prevalence of overweight and obesity among adult women in Bangladesh: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e014399. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Danilack VA, Brousseau EC, Phipps MG. The effect of gestational weight gain on persistent increase in body mass index in adolescents: A longitudinal study. J Womens Heal [Internet] 2018;27(12):1456–1458. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2017.6635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Asefa F, Nemomsa D. Gestational weight gain and its associated factors in Harari regional state: institution based cross-sectional study, Eastern Ethiopia. Reprod Health. 2016;13(1):101. 10.1186/s12978-016-0225-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The study utilizes secondary sources of data that are freely available in the public domain through https://dhsprogram.com/methodology/survey/survey-display-355.cfm. Those who wish to access the data may register at the above link and thereafter can download the required data free of cost.