Abstract

Objective:

Indigenous youth often exhibit high rates of alcohol use and experience disproportionate alcohol-related harm. We examined the moderating role that valuing cultural activities has on the relationship between positive alcohol expectancies and alcohol use and heavy drinking in a sample of Indigenous youth.

Method:

First Nation adolescents between ages 11 and 18 living on a reserve in eastern Canada (N = 106; mean age = 14.6; 50.0% female) completed a pencil-and-paper survey regarding their positive alcohol expectancies, alcohol use, and beliefs about the importance of cultural activities.

Results:

A significant interaction was identified between positive alcohol expectancies and valuing cultural activities on past-3-month alcohol use (b = -0.01, SE = 0.001, p < .001) and past-3-month heavy drinking (b = -0.01, SE = 0.001, p < .001). Simple slopes analysis revealed that the association between positive alcohol expectancies and past-3-month alcohol use and heavy drinking was significant for those with low (b = 0.06, SE = 0.007, p < .001; b = 0.07, SE = 0.008, p < .001; respectively) but not high levels of valuing cultural activities (b = 0.01, SE = 0.008, p = .12; b = 0.01, SE = 0.009, p = .08; respectively).

Conclusions:

Highly valuing cultural activities may interrupt the relationship between positive alcohol expectancies and alcohol use. This suggests that community interventions and treatment programs targeting alcohol use among Indigenous adolescents should prioritize increasing the value of cultural activities by perhaps making them more available.

North american indigenous populations include American Indians and Alaska Natives in the United States and First Nations in Canada, among others. Although there is a great deal of heterogeneity among North American Indigenous groups, Indigenous youth often exhibit high rates of alcohol use (Stanley et al., 2014; Swaim & Stanley, 2018; Whitbeck et al., 2014). One epidemiological study found that Indigenous youth living on or near a reservation reported higher lifetime rates of alcohol use and having been drunk compared with a national sample of students from Monitoring the Future (Swaim & Stanley, 2018). Moreover, Indigenous youth tend to initiate alcohol use early (Friese et al., 2011; Henry et al., 2011; Stanley & Swaim, 2015), with an average age of 13–14 years (Spillane et al., 2015; Whitesell et al., 2012). Indigenous youth who drink alcohol until intoxicated before age 14 experience more alcohol-related problems, use alcohol more heavily, and are more likely to be diagnosed with an alcohol use disorder later in life (Henry et al., 2011). In addition, Indigenous youth are disproportionately likely to experience various alcohol-related problems (Indian Health Service, 2018; Landen et al., 2014; Stanley et al., 2014), such as car accidents and relationship problems, when compared with their White peers (Beauvais, 1992).

One factor that is robustly related to alcohol use is positive alcohol expectancies (Cable & Sacker, 2008; Patrick et al., 2010), which are beliefs about positive effects of drinking alcohol (e.g., enhancing social experiences or positive emotions; Fromme & D’Amico, 2000; Settles et al., 2014; Zapolski & Clifton, 2019). Previous literature has found positive alcohol expectancies to positively predict alcohol use in adolescent samples (Smit et al., 2018), including among Indigenous adults (Garcia-Andrade et al., 1996; Looby et al., 2017; Spillane et al., 2012) and adolescents (Dieterich et al., 2013; Mitchell et al., 2006a). Given the robust relationship between alcohol expectancies and alcohol use, it is important to consider what factors may influence this relationship.

Although individual differences are important, research suggests that cultural factors may also contribute to our understanding of alcohol use within Indigenous populations. Culture refers to a system of beliefs, values, customs, and traditions that are transmitted across generations through teachings, ecological knowledge, and time-honored land-based practices (McIvor et al., 2009). For Indigenous populations, culture can take many forms, including, but not limited to, ceremonies; methods of hunting, fishing, and gathering foods; gathering and use of traditional medicines; traditional diet; spiritual journeying; and traditional art forms such as drumming, dancing, and singing (McIvor et al., 2009). Although research has demonstrated promising opportunities to integrate Indigenous culture into contemporary Western substance use treatments (Gone, 2010), studies examining the relationship between culture and alcohol use among Indigenous populations have shown mixed findings. Some studies have found that cultural identity (i.e., ethnic pride and cultural engagement) is unrelated to alcohol use among Indigenous adolescents (Whitesell et al., 2014) and that participation in some cultural activities is positively associated with alcohol dependence among Indigenous youth (Yu & Stiffman, 2007). Other studies have found strong Indigenous cultural identity and placing importance on traditional values and practices (Tingey et al., 2016) to be protective against Indigenous adolescent alcohol use. Moreover, one qualitative study found that Indigenous adults believe that adolescent engagement in cultural activities may provide therapeutic and health-enhancing benefits, decreasing the likelihood that they will participate in self-destructive behaviors such as alcohol use (Brown et al., 2016).

When studying alcohol use among Indigenous populations, it is also vital to consider the historical context in which Indigenous people live and the effects of history. Studies have shown that historical trauma related to colonization of North America—including forced removal from tribal lands, broken treaties, and enforced placement of Indigenous children in boarding schools—has contributed to Indigenous alcohol use (Ross et al., 2015; Whitbeck et al., 2004; Wiechelt et al., 2012). Indigenous people did not have distilled, potent forms of alcohol before European contact (Beauvais, 1998), and thus alcohol consumption was not a traditional part of Indigenous culture. Given this history, the literature has highlighted the importance of integrating traditional culture into alcohol and drug interventions with Indigenous populations (Szlemko et al., 2006; Walters et al., 2020) and calls for clarity on what aspects of culture are protective against alcohol use for Indigenous adolescents (Whitesell et al., 2014). Therefore, our research aims to better understand how valuing cultural activities, or the importance of specific cultural activities, relates to Indigenous adolescent alcohol use.

For this study, we refer to valuing cultural activities based on the Competing Life Reinforcers model (Spillane et al., 2020). This model was developed drawing on Behavioral Theories of Choice and Standard Life Reinforcers (Spillane & Smith, 2007). Behavioral Theories of Choice proposes that substance use varies based on two factors: availability of substances and of substance-free reinforcers (e.g., activities that individuals like engaging in, important relationships), and that engaging in fewer substance-free alternative reinforcers results in more substance use (Khoddam & Leventhal, 2016). Adapting Behavioral Theories of Choice to understand North American Indigenous risk for alcohol misuse, Spillane and Smith (2007) described Standard Life Reinforcers as basic life reinforcers or experiences that people strive for (i.e., housing, family closeness, knowledge, economic security). The Competing Life Reinforcers construct was developed to adapt Standard Life Reinforcers to be developmentally appropriate for adolescents and is defined as things that are available on a First Nation reserve, consistent with values and inconsistent with substance use among adolescents. To qualify as a Competing Life Reinforcer, a reinforcer must be (a) valued (e.g., one’s judgment of what is important in life; Stevenson, 2010), (b) available when the individual is not using substances, and (c) incompatible with substance use (i.e., substance use will change the availability of that particular reinforcer, such that if an individual uses substances, the reinforcer is no longer available; Spillane et al., 2020). In the present study, we assume that this third condition is met given that, during the development of the Competing Life Reinforcers construct, the specific cultural activities currently under investigation were identified by Indigenous youth from the same community as incompatible with substance use (Spillane et al., 2020). Because of the deterioration of traditional culture from historical trauma (Chase, 2012; Szlemko et al., 2006), Indigenous adolescents may have fewer opportunities to engage in cultural activities; yet, these activities survived generations because of their inherited value. Therefore, although the purpose of the present article was to examine the specific construct of valuing cultural activities, we also include the availability of cultural activities into our models to examine their effects due to the importance placed on the availability of reinforcers in the Competing Life Reinforcers model. In particular, we aimed to examine how positive alcohol expectancies relate to alcohol use and heavy drinking and to test the moderating role of valuing cultural activities in this relationship. We hypothesized that valuing cultural activities would be associated with lower positive alcohol expectancies and likelihood of alcohol use and heavy drinking. Further, we hypothesized that valuing cultural activities would moderate the relationship between alcohol expectancies and alcohol use and heavy drinking, such that higher levels of valuing cultural activities would weaken the association between positive alcohol expectancies and alcohol use and heavy drinking.

Method

Participants and procedures

Participants were recruited via snowball sampling through advertisements and announcements in reserve communities as part of a larger study examining risk and protective factors associated with substance use among First Nation adolescents. All research procedures were approved by institutional review board, tribal chief, and council before data collection. Parental permission was obtained before recruiting each child into the study, and then investigators explained the study to the youth, who provided written assent. The questionnaires took approximately 45 minutes to complete and participants were compensated $25. A total of 106 First Nation adolescents from eastern Canadian reserve communities completed pencil-and-paper surveys in spring 2017. Participants ranged in age from 11 to 18 (M = 14.58, SD = 2.15) and were 50.0% female.

Measures

Alcohol expectancies were assessed using eight items chosen by the Voices of Indian Teens survey from the Alcohol Expectancy Questionnaire (Mann et al., 1987), reflecting positive outcomes that individuals believe will happen if they drink alcohol. Participants rate the extent to which they believe each statement is accurate on a Likert-type scale with five possible response options (1 = disagree, 5 = agree). Scores are summed to create a total scale score with possible scores ranging from 8 to 40; higher values reflect more positive alcohol expectancies (M = 19.13, SD = 8.43). Internal consistency in the present sample was excellent (Cronbach’s α = .91).

Alcohol use was assessed using one item from the Adolescent Drinking Questionnaire (Donovan & Jessor, 1978) regarding how frequently adolescents drank alcohol in the past 3 months, with eight possible response options (0 = never, I did not drink any alcohol in the past 3 months, 7 = every day). For analyses examining the likelihood of past-3-month alcohol use, this item was dichotomized such that 0 represented no alcohol use and 1 represented any frequency of alcohol use in the preceding 3 months.

Heavy drinking was assessed using one item from the Adolescent Drinking Questionnaire regarding how often adolescents had drunk five or more alcoholic drinks if they were male and four or more if they were female in the past 3 months, with eight possible response options (0 = never, I did not drink any alcohol in the past 3 months, 7 = every day). For analyses examining the likelihood of past-3-month heavy drinking, this item was dichotomized such that 0 represented no instances of heavy drinking and 1 represented any number of heavy drinking instances in the preceding 3 months. For moderation analyses, we examined the frequency of alcohol use and heavy drinking including all possible response options.

Cultural activities were assessed using five items from the Competing Life Reinforcers measure (Spillane et al., 2020). These items reflect culturally grounded activities, identified by focus groups of First Nation youth, that serve as alternative reinforcers to substance use and include traditional crafts, powwows, talking circles, sweats, and learning about one’s culture. Participants rate how important each item is for them (0 = not at all, 5 = extremely important) and whether each item is available to them (0 = no, 1 = yes). Valuing item scores were summed to create a total scale score, with possible scores ranging from 0 to 25, with higher scores reflecting a greater valuing of cultural activities (M = 16.42, SD = 4.34). Internal consistency in the present sample was good (Cronbach’s α = .90). Availability item scores were also summed to create a total scale score, with possible scores ranging from 0 to 5 and higher scores reflecting a greater number of cultural activities available (M = 3.90, SD = 1.46).

Demographics.

Participants reported their age, gender, and grade in school.

Analytic plan

All study analyses were conducted using SPSS Version 24 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). As recommended by Tabachnick and Fidell (2007), all variables of interest were assessed for assumptions of normality. Pearson product-moment correlations were then calculated between relevant study variables to explore their bivariate associations. All primary study variables were missing data in less than 10% of cases, and missing data were handled using multiple imputation. Next, we conducted two binary logistic regression models to assess the effect of alcohol expectancies and valuing cultural activities on the log odds of having drunk alcohol in the past 3 months and of having a heavy drinking episode in the past 3 months, controlling for the effects of age, gender, and availability of cultural activities. Last, to address the question of whether alcohol expectancies, valuing cultural activities, and/or their interaction were associated with the frequency of past-3-month alcohol use and of past-3-month heavy drinking controlling for the effects of age, gender, and availability of cultural activities, moderation analyses were conducted using the SPSS PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2012). Predictor variables were mean centered before constructing the interaction term to aid in interpretation of parameter estimates and to lessen the correlation between the interaction term and its component variables. The PROCESS procedures use ordinary least squares regression and bootstrapping methodology, which confer more statistical power than do standard approaches to statistical inference and do not rely on distributional assumptions (Hayes, 2012). Bootstrapping was done with 5,000 random samples generated from the observed covariance matrix to estimate bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and significance values. Following the methods described by Aiken, West, and Reno (1991), we followed up significant interactions with simple slopes analysis and plotted regression slopes of differences in alcohol expectancies in participants with high (1 SD above the mean) and low (1 SD below the mean) levels of valuing cultural activities.

Results

Preliminary analyses

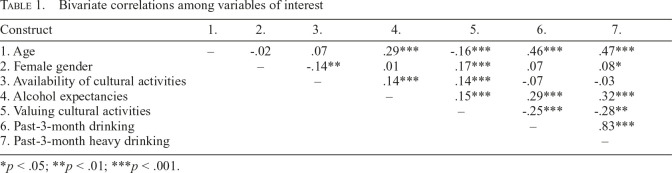

In this sample, 37.7% of adolescents (n = 40) reported past-3-month alcohol use and 31.1% (n = 33) reported having at least one past-3-month heavy drinking episode. Pearson product-moment correlations revealed significant positive associations between alcohol expectancies and availability of cultural activities (r = .14, p < .001) and the frequency of both past-3-month drinking (r = .29, p < .001) and heavy drinking (r = .32, p < .001). Valuing cultural activities was significantly positively associated with alcohol expectancies (r = .15, p < .001) but was significantly negatively associated with the frequency of past-3-month drinking (r = -.25, p < .001) and heavy drinking (r = -.28, p = .001). Availability of cultural activities was not significantly associated with past-3-month drinking or heavy drinking. See Table 1 for bivariate correlations among primary variables of interest. Although not presented in our main correlation table, we examined the correlations among each cultural activity assessed and both alcohol use outcomes. We found that each individual cultural activity was significantly negatively associated with both the frequency of past-3-month alcohol use (rs = -17 to -.27, ps < .001) and past-3-month heavy drinking (rs = -.21 to -.30, ps < .001).

Table 1.

Bivariate correlations among variables of interest

| Construct | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. |

| 1. Age | – | -.02 | .07 | .29*** | -.16*** | .46*** | .47*** |

| 2. Female gender | – | -.14** | .01 | .17*** | .07 | .08* | |

| 3. Availability of cultural activities | – | .14*** | .14*** | -.07 | -.03 | ||

| 4. Alcohol expectancies | – | .15*** | .29*** | .32*** | |||

| 5. Valuing cultural activities | – | -.25*** | -.28** | ||||

| 6. Past-3-month drinking | – | .83*** | |||||

| 7. Past-3-month heavy drinking | – |

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Regression analyses

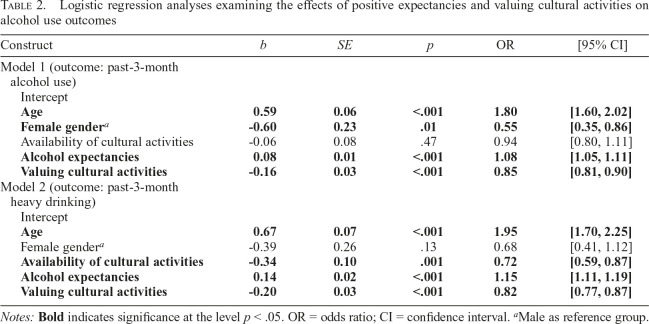

We conducted two logistic regression analyses to examine the effect of alcohol expectancies and valuing cultural activities on the log odds of having drunk alcohol in the past 3 months and having at least one heavy drinking episode in the past 3 months, controlling for the effects of age, gender, and availability of cultural activities. Logistic regression analyses are summarized in Table 2. Higher endorsement of positive alcohol expectancies was associated with significantly higher odds of having drunk alcohol (odds ratio [OR] = 1.08, 95% CI [1.05, 1.11]) and having at least one heavy drinking episode (OR = 1.15, 95% CI [1.11, 1.19]) in the past 3 months. On the other hand, higher endorsement of valuing cultural activities was associated with significantly lower odds of having drunk alcohol (OR = 0.85, 95% CI [0.81, 0.90]) and having at least one heavy drinking episode (OR = 0.82, 95% CI [0.77, 0.87]) in the past 3 months. The availability of cultural activities was not significantly associated with the odds of having drunk alcohol (OR = 0.94, 95% CI [0.80, 1.11]) but was significantly associated with decreased odds of having at least one heavy drinking episode (OR = 0.72, 95% CI [0.59, 0.87]) in the past 3 months.

Table 2.

Logistic regression analyses examining the effects of positive expectancies and valuing cultural activities on alcohol use outcomes

| Construct | b | SE | p | OR | [95% CI] |

| Model 1 (outcome: past-3-month alcohol use) | |||||

| Intercept | |||||

| Age | 0.59 | 0.06 | <.001 | 1.80 | [1.60, 2.02] |

| Female gendera | -0.60 | 0.23 | .01 | 0.55 | [0.35, 0.86] |

| Availability of cultural activities | -0.06 | 0.08 | .47 | 0.94 | [0.80, 1.11] |

| Alcohol expectancies | 0.08 | 0.01 | <.001 | 1.08 | [1.05, 1.11] |

| Valuing cultural activities | -0.16 | 0.03 | <.001 | 0.85 | [0.81, 0.90] |

| Model 2 (outcome: past-3-month heavy drinking) | |||||

| Intercept | |||||

| Age | 0.67 | 0.07 | <.001 | 1.95 | [1.70, 2.25] |

| Female gendera | -0.39 | 0.26 | .13 | 0.68 | [0.41, 1.12] |

| Availability of cultural activities | -0.34 | 0.10 | .001 | 0.72 | [0.59, 0.87] |

| Alcohol expectancies | 0.14 | 0.02 | <.001 | 1.15 | [1.11, 1.19] |

| Valuing cultural activities | -0.20 | 0.03 | <.001 | 0.82 | [0.77, 0.87] |

Notes: Bold indicates significance at the level p < .05. OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval.

Male as reference group.

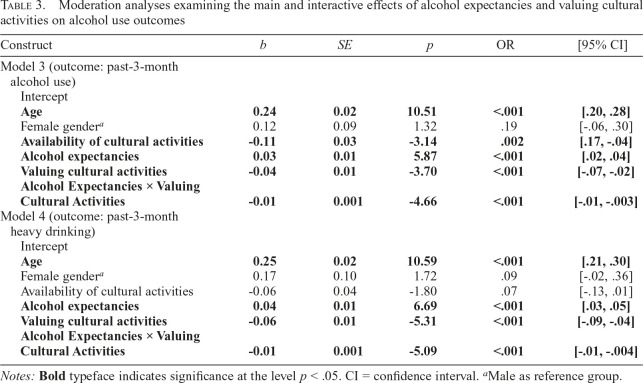

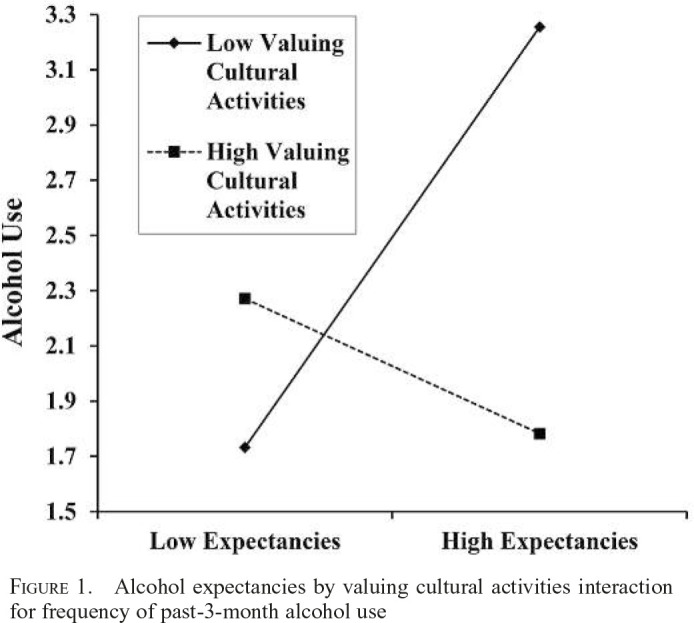

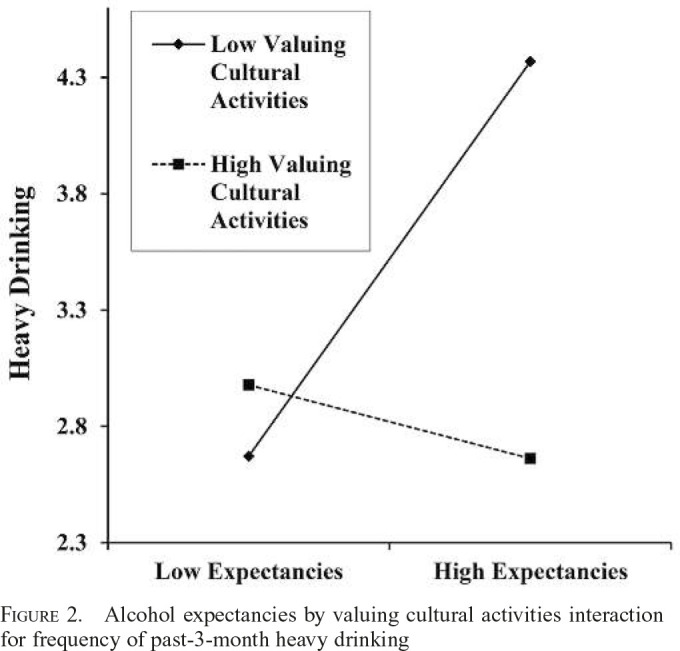

Last, we conducted two moderation analyses to examine whether alcohol expectancies, valuing cultural activities, and/or their interaction were significantly associated with the frequency of past-3-month alcohol use and heavy drinking. These analyses are summarized in Table 3. Regarding the frequency of past-3-month alcohol use, significant main effects were found for alcohol expectancies (b = 0.03, SE = 0.01 p < .001) and valuing cultural activities (b = -0.04, SE = 0.01 p < .001). The availability of cultural activities was also significantly associated with the frequency of past-3-month alcohol use (b = -0.11, SE = 0.03, p = .002). Further, the interaction between alcohol expectancies and valuing cultural activities was significant (b = -0.01, SE = 0.001, p < .001). As illustrated in Figure 1, analysis of simple slopes revealed that alcohol expectancies were significantly positively associated with the frequency of past-3-month alcohol consumption when participants endorsed low (b = 0.06, SE = 0.007 p < .001) but not high levels of valuing cultural activities (b = 0.01, SE = 0.008, p = .12). Regarding the frequency of past-3-month heavy drinking, significant main effects were found for alcohol expectancies (b = 0.04, SE = 0.01, p < .001) and valuing cultural activities (b = -0.06, SE = 0.01, p < .001). The availability of cultural activities was not significantly associated with the frequency of past-3-month heavy drinking (b = -0.06, SE = 0.04, p = .07). Further, the interaction between alcohol expectancies and valuing cultural activities was significant (b = -0.01, SE = 0.001, p < .001). As illustrated in Figure 2, analysis of simple slopes revealed that alcohol expectancies was also significantly positively associated with the frequency of past-3-month heavy drinking when participants endorsed low (b = 0.07, SE = 0.008 p < .001) but not high levels of valuing cultural activities (b = 0.01, SE = 0.009, p = .08).

Table 3.

Moderation analyses examining the main and interactive effects of alcohol expectancies and valuing cultural activities on alcohol use outcomes

| Construct | b | SE | p | OR | [95% CI] |

| Model 3 (outcome: past-3-month alcohol use) | |||||

| Intercept | |||||

| Age | 0.24 | 0.02 | 10.51 | <.001 | [.20, .28] |

| Female gendera | 0.12 | 0.09 | 1.32 | .19 | [-.06, .30] |

| Availability of cultural activities | -0.11 | 0.03 | -3.14 | .002 | [.17, -.04] |

| Alcohol expectancies | 0.03 | 0.01 | 5.87 | <.001 | [.02, .04] |

| Valuing cultural activities | -0.04 | 0.01 | -3.70 | <.001 | [-.07, -.02] |

| Alcohol Expectancies × Valuing Cultural Activities | -0.01 | 0.001 | -4.66 | <.001 | [-.01, -.003] |

| Model 4 (outcome: past-3-month heavy drinking) | |||||

| Intercept | |||||

| Age | 0.25 | 0.02 | 10.59 | <.001 | [.21, .30] |

| Female gendera | 0.17 | 0.10 | 1.72 | .09 | [-.02, .36] |

| Availability of cultural activities | -0.06 | 0.04 | -1.80 | .07 | [-.13, .01] |

| Alcohol expectancies | 0.04 | 0.01 | 6.69 | <.001 | [.03, .05] |

| Valuing cultural activities | -0.06 | 0.01 | -5.31 | <.001 | [-.09, -.04] |

| Alcohol Expectancies × Valuing Cultural Activities | -0.01 | 0.001 | -5.09 | <.001 | [-.01, -.004] |

Notes: Bold typeface indicates significance at the level p < .05. CI = confidence interval.

Male as reference group.

Figure 1.

Alcohol expectancies by valuing cultural activities interaction for frequency of past-3-month alcohol use

Figure 2.

Alcohol expectancies by valuing cultural activities interaction for frequency of past-3-month heavy drinking

Discussion

Current literature calls for clarity on what aspects of culture are protective against alcohol use for Indigenous adolescents (Whitesell et al., 2014). Accordingly, the aim of this study was to examine how positive alcohol expectancies relate to alcohol use and heavy drinking for Indigenous adolescents and to test whether valuing cultural activities moderates this relationship.

Our finding that greater positive alcohol expectancies are significantly associated with higher odds of having drunk and having at least one heavy drinking episode aligns well with prior literature (Cable & Sacker, 2008; Dieterich et al., 2013; Mitchell et al., 2006a, 2006b; Mitchell et al., 2006b; Patrick et al., 2010; Smit et al., 2018). Furthermore, our results, which suggest that highly valuing cultural activities may interrupt the relationship between positive alcohol expectancies and alcohol use, is of great importance and contributes a novel finding to the literature with implications that advance theory, research, and practice.

Further, our results are consistent with extant literature finding culture to be protective against alcohol use for Indigenous adolescents (Brown et al., 2016; McIvor et al., 2009; Spillane et al., 2020; Spillane et al., under review), such that it aligns well with research finding adolescents’ sense of pride and belonging to Indigenous culture, in and of itself, is protective (Brown et al., 2021), as well as with studies suggesting that those who identify less with Indigenous culture are more likely to drink heavily compared with those who identify more with Indigenous culture (Herman-Stahl et al., 2003). Adolescents who value cultural activities may experience protective benefits because they offer alternative reinforcement to drinking (Spillane et al., 2020; Spillane et al., under review; Spillane & Smith, 2007). Because of the deterioration of traditional culture from historical trauma (Chase, 2012; Szlemko et al., 2006) and a history of communities being legally barred from engaging in important traditional activities, Indigenous adolescents may have fewer opportunities to engage in cultural activities. However, these activities have survived across generations through communication of their importance and thus remain valuable. Our results suggest that, independent of availability, the increasing value of those activities may still be protective for these youth. Indigenous cultural traditions may provide individuals with role demands and rewards beyond the immediate social reinforcements of alcohol use (Herman-Stahl et al., 2003). Nevertheless, historical trauma and the significant loss of cultural reinforcements may account for high alcohol use and alcohol-related consequences among Indigenous youth. Given the association between historical trauma and alcohol use (Brave Heart, 2003), it may be true that adolescents living in communities still struggling with alcohol (e.g., such as the community in this study; Spillane et al., 2015) develop positive alcohol expectancies while still valuing cultural activities. This aligns with our finding that positive alcohol expectancies were positively associated with valuing cultural activities. It is likely that future healing from historical trauma and revitalization of culture will affect this relationship.

Conversely, our finding that culture is protective is in contrast with studies finding participation in cultural activities to be positively associated with alcohol dependence among Indigenous youth (Yu & Stiffman, 2007). However, these conflicting results may be a consequence of prior studies measuring engagement in cultural activities, whereas instead we measured valuing cultural activities. Future research should clarify these constructs by measuring both engagement and valuing of cultural activities to determine if they are uniquely and differentially related to alcohol use. In addition, future studies should investigate the potential interaction between positive alcohol expectancies and engagement in cultural activities.

Our findings have important implications for alcohol use interventions for Indigenous populations. Indigenous communities have called for interventions to be culturally centered since “culture is medicine” (Bassett et al., 2012; Walters et al., 2020). Specifically, Walters et al. (2020) describe prioritizing culturally centered approaches rooted in Indigenous epistemologies and their corresponding core values and actions, going beyond simply adding cultural practices into existing interventions. Our results suggest that interventions targeting alcohol use should be developed within communities to align with their values (Walters et al., 2020), focusing on individual alcohol use while also accounting for community-level influence, context, and support (Blue Bird Jernigan et al., 2020; Dickerson et al., 2016; Whitesell et al., 2020) and strengthening the connection between individuals and cultural reinforcers. Accordingly, communities should prioritize engaging adolescents in the selection and incorporation of specific cultural activities that are more highly valued, as this will likely confer a protective effect against alcohol use. This is in line with suggestions from the literature, which propose that mental health promotion programs be aimed at restoring a strong sense of cultural identity by giving youth an active role in designing and implementing programs that meet their needs (Kirmayer et al., 2003). Furthermore, although we found that the availability of activities was less consistently related to drinking outcomes, it was significant in some of our models, indicating some protective effects. Therefore, increasing the availability of important cultural activities valued by the community may strengthen the inherited value adolescents place on those activities, as the availability of cultural activities may be cyclically related to valuing those activities. Individuals may be inclined to value activities that are available to them; therefore, communities should try to increase the availability of cultural reinforcers that are important to youth. Increasing the availability of cultural activities may increase their value, which then may encourage communities to increase their availability.

Limitations and future directions

The findings of this study should be considered within the context of its limitations. First, data were collected from one band of reserve-dwelling First Nation adolescents in eastern Canada. There is great variability between North American Indigenous communities; thus results may not be applicable to communities in other geographic regions, to other Indigenous groups, or to First Nation adolescents living off reserves. Moreover, although our sample represents approximately one third of adolescents within this age range from this cultural group (Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada, 2016), our relatively small sample size should be noted as a limitation. Furthermore, the cross-sectional nature of these data precludes determination of temporality among the observed relationship. Future research should study the association between valuing cultural activities and alcohol use as well as their relationship with positive alcohol expectancies with Indigenous youth in an urban setting and in other geographic regions. In addition, it should be noted that perhaps there is an interconnected nature between valuing and participating in cultural activities and that adolescents may be more likely to value activities in which they can participate. Thus, future studies should measure participation in addition to importance and availability to further parse out these associations.

Consideration of valuing cultural activities may aid in reducing the alcohol-related health disparities seen with Indigenous youth. Future research should consider the relationship between alcohol expectancies, valuing cultural activities, and the association with alcohol-related problems. Further, given the nature of the data, we were unable to account for other known predictors of adolescent alcohol use, including depression (Clark et al., 2003; Ganz & Sher, 2009), family caring (Resnick et al., 1997), parental monitoring (Rodgers-Farmer, 2001; Whitesell et al., 2014), and cultural identity (Spillane et al., 2015). Future research should consider how other factors relate to valuing cultural activities and their association with alcohol use and alcohol expectancies.

Our study, which found valuing cultural activities to be protective against drinking in Indigenous youth, has promising implications for future research, treatment, and prevention approaches. Assessing for and incorporating cultural activities that are valued by Indigenous youth may be a promising avenue for reducing adolescent alcohol use.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participants for their time and contributions and for sharing this information. The authors also thank Peter Barbagallo for his contributions to the manuscript.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse Grant K08DA029094 to Nichea S. Spillane.

References

- Aiken L. S., West S. G., Reno R. R. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bassett D., Tsosie U., Nannauck S. “Our culture is medicine”: Perspectives of Native healers on posttrauma recovery among American Indian and Alaska Native patients. The Permanente Journal. 2012;16:19–27. doi: 10.7812/tpp/11-123. doi:10.7812/TPP/11-123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauvais F. The consequences of drug and alcohol use for Indian youth. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research. 1992;5:32–37. doi: 10.5820/aian.0501.1992.32. doi:10.5820/aian.0501.1992.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauvais F. American Indians and alcohol. Alcohol Health and Research World. 1998;22:253–259. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blue Bird Jernigan V., D’Amico E. J., Duran B., Buchwald D. Multilevel and community-level interventions with Native Americans: Challenges and opportunities. Prevention Science. 2020;21(Supplement 1):65–73. doi: 10.1007/s11121-018-0916-3. doi:10.1007/s11121-018-0916-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brave Heart M. Y. H. The historical trauma response among natives and its relationship with substance abuse: A Lakota illustration. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2003;35:7–13. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2003.10399988. doi:10.1080/02791072.2003.10399988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown R. A., Dickerson D. L., D’Amico E. J. Cultural identity among urban American Indian/Alaska Native youth: Implications for alcohol and drug use. Prevention Science. 2016;17:852–861. doi: 10.1007/s11121-016-0680-1. doi:10.1007/s11121-016-0680-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown R. A., Dickerson D. L., Klein D. J., Agniel D., Johnson C. L., D’Amico E. J. Identifying as American Indian/Alaska Native in urban areas: Implications for adolescent behavioral health and well-being. Youth & Society. 2021;53:54–75. doi: 10.1177/0044118x19840048. doi:10.1177/0044118X19840048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cable N., Sacker A. Typologies of alcohol consumption in adolescence: Predictors and adult outcomes. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2008;43:81–90. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agm146. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agm146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase J. A. Native American elders’ perceptions of the boarding school experience on Native American parenting: An exploratory study. Dissertation; Smith College, Northampton, MA: 2012. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.smith.edu/theses/390/ [Google Scholar]

- Clark D. B., De Bellis M. D., Lynch K. G., Cornelius J. R., Martin C. S. Physical and sexual abuse, depression and alcohol use disorders in adolescents: Onsets and outcomes. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2003;69:51–60. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00254-5. doi:10.1016/S0376-8716(02)00254-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson D. L., Brown R. A., Johnson C. L., Schweigman K., D’Amico E. J. Integrating motivational interviewing and traditional practices to address alcohol and drug use among urban American Indian/Alaska Native youth. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2016;65:26–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2015.06.023. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2015.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieterich S. E., Stanley L. R., Swaim R. C., Beauvais F. Outcome expectancies, descriptive norms, and alcohol use: American Indian and white adolescents. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2013;34:209–219. doi: 10.1007/s10935-013-0311-6. doi:10.1007/s10935-013-0311-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan J. E., Jessor R. Adolescent problem drinking. Psychosocial correlates in a national sample study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1978;39:1506–1524. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1978.39.1506. doi:10.15288/jsa.1978.39.1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friese B., Grube J. W., Seninger S., Paschall M. J., Moore R. S. Drinking behavior and sources of alcohol: Differences between Native American and White youths. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011;72:53–60. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.53. doi:10.15288/jsad.2011.72.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromme K., D’Amico E. J. Measuring adolescent alcohol outcome expectancies. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2000;14:206–212. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.14.2.206. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.14.2.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganz D., Sher L. Suicidal behavior in adolescents with comorbid depression and alcohol abuse. Minerva Pediatrica. 2009;61:333–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Andrade C., Wall T. L., Ehlers C. L. Alcohol expectancies in a Native American population. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1996;20:1438–1442. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01146.x. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gone J. P. Psychotherapy and traditional healing for American Indians: Exploring the prospects for therapeutic integration. The Counseling Psychologist. 2010;38:166–235. doi:10.1177/0011000008330831. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A. F. PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf.

- Henry K. L., McDonald J. N., Oetting E. R., Walker P. S., Walker R. D., Beauvais F. Age of onset of first alcohol intoxication and subsequent alcohol use among urban American Indian adolescents. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2011;25:48–56. doi: 10.1037/a0021710. doi:10.1037/a0021710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman-Stahl M., Spencer D. L., Duncan J. E. The implications of cultural orientation for substance use among American Indians. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research. 2003;11:46–66. doi: 10.5820/aian.1101.2003.46. doi:10.5820/aian.1101.2003.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indian Health Service. Fact Sheet: Disparities. 2018 Retrieved from https://www.ihs.gov/newsroom/factsheets/disparities/

- Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada. First Nation Profiles. 2016 Retrieved from https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/ref/guides/009/98-500-x2016009-eng.cfm.

- Khoddam R., Leventhal A. M. Alternative and complementary reinforcers as mechanisms linking adolescent conduct problems and substance use. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2016;24:376–389. doi: 10.1037/pha0000088. doi:10.1037/pha0000088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirmayer L., Simpson C., Cargo M. Healing traditions: Culture, community and mental health promotion with Canadian Aboriginal peoples. Australasian Psychiatry. 2003;11(Supplement 1):S15–S23. [Google Scholar]

- Landen M., Roeber J., Naimi T., Nielsen L., Sewell M. Alcohol-attributable mortality among American Indians and Alaska Natives in the United States, 1999-2009. American Journal of Public Health. 2014;104(Supplement 3):S343–S349. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301648. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2013.301648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Looby A., Luger E. J., Guartos C. S. Positive expectancies mediate the link between race and alcohol use in a sample of Native American and Caucasian college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2017;73:53–56. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.04.019. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann L. M., Chassin L., Sher K. J. Alcohol expectancies and the risk for alcoholism. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1987;55:411–417. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.55.3.411. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.55.3.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIvor O., Napoleon A., Dickie K. M. Language and culture as protective factors for at-risk communities. International Journal of Indigenous Health. 2009;5:6. doi:10.18357/ijih51200912327. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell C. M., Beals J., Kaufman C. the Pathways of Choice Team. Alcohol use, outcome expectancies, and HIV risk status among American Indian youth: A latent growth curve model with parallel processes. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2006a;35:726–737. doi:10.1007/s10964-006-9103-0. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell C. M., Beals J. the Pathways of Choice Team. The development of alcohol use and outcome expectancies among American Indian young adults: A growth mixture model. Addictive Behaviors. 2006b;31:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.04.006. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick M. E., Wray-Lake L., Finlay A. K., Maggs J. L. The long arm of expectancies: Adolescent alcohol expectancies predict adult alcohol use. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2010;45:17–24. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agp066. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agp066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick M. D., Bearman P. S., Blum R. W., Bauman K. E., Harris K. M., Jones J., Udry J. R. Protecting adolescents from harm: Findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. JAMA. 1997;278:823–832. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.10.823. doi:10.1001/jama.1997.03550100049038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers-Farmer A. Y. Parental monitoring and peer group association: Their influence on adolescent substance use. Journal of Social Service Research. 2001;27:1–18. doi:10.1300/J079v27n02_01. [Google Scholar]

- Ross A., Dion J., Cantinotti M., Collin-Vézina D., Paquette L. Impact of residential schooling and of child abuse on substance use problem in Indigenous Peoples. Addictive Behaviors. 2015;51:184–192. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.07.014. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settles R. E., Zapolski T. C., Smith G. T. Longitudinal test of a developmental model of the transition to early drinking. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2014;123:141–151. doi: 10.1037/a0035670. doi:10.1037/a0035670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit K., Voogt C., Hiemstra M., Kleinjan M., Otten R., Kuntsche E. Development of alcohol expectancies and early alcohol use in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2018;60:136–146. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2018.02.002. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2018.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spillane N. S., Cyders M. A., Maurelli K. Negative urgency, problem drinking and negative alcohol expectancies among members from one First Nation: A moderated-mediation model. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37:1285–1288. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.06.007. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spillane N. S., Greenfield B., Venner K., Kahler C. W. Alcohol use among reserve-dwelling adult First Nation members: Use, problems, and intention to change drinking behavior. Addictive Behaviors. 2015;41:232–237. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.10.015. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spillane N. S., Kirk-Provencher K. T., Schick M. R., Nalven T., Goldstein S. C., Kahler C. W. Identifying competing life reinforcers to substance use in First Nation adolescents. Substance Use & Misuse. 2020;55:886–895. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2019.1710206. doi:10.1080/10826084.2019.1710206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spillane N. S., Schick M. R., Nalven T., Goldstein S. C., Hill D., Khaler C. W. Importance and availability of alternative reinforcers is associated with substance use behaviors in First Nation youth under review [Google Scholar]

- Spillane N. S., Smith G. T. A theory of reservation-dwelling American Indian alcohol use risk. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133:395–418. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.3.395. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.133.3.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley L. R., Harness S. D., Swaim R. C., Beauvais F. Rates of substance use of American Indian students in 8th, 10th, and 12th grades living on or near reservations: Update, 2009-2012. Public Health Reports. 2014;129:156–163. doi: 10.1177/003335491412900209. doi:10.1177/003335491412900209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley L. R., Swaim R. C. Initiation of alcohol, marijuana, and inhalant use by American-Indian and white youth living on or near reservations. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2015;155:90–96. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.08.009. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson A., editor. Oxford Dictionary of English. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Swaim R. C., Stanley L. R. Substance use among American Indian youths on reservations compared with a national sample of US adolescents. JAMA Network Open. 2018;1:e180382. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0382. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szlemko W. J., Wood J. W., Thurman P. J. Native Americans and alcohol: Past, present, and future. Journal of General Psychology. 2006;133:435–451. doi: 10.3200/GENP.133.4.435-451. doi:10.3200/GENP.133.4.435-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick B. G., Fidell L. S. 5th Edition. Needham Height, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 2007. Using multivariate statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Tingey L., Cwik M. F., Rosenstock S., Goklish N., Larzelere-Hinton F., Lee A., Barlow A. Risk and protective factors for heavy binge alcohol use among American Indian adolescents utilizing emergency health services. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2016;42:715–725. doi: 10.1080/00952990.2016.1181762. doi:10.1080/00952990.2016.1181762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters K. L., Johnson-Jennings M., Stroud S., Rasmus S., Charles B., John S., Boulafentis J. Growing from our roots: Strategies for developing culturally grounded health promotion interventions in American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian Communities. Prevention Science. 2020;21:54–64. doi: 10.1007/s11121-018-0952-z. doi:10.1007/s11121-018-0952-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitbeck L. B., Adams G. W., Hoyt D. R., Chen X. Conceptualizing and measuring historical trauma among American Indian people. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2004;33:119–130. doi: 10.1023/b:ajcp.0000027000.77357.31. doi:10.1023/B:AJCP.0000027000.77357.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitbeck L. B., Sittner Hartshorn K. J., Crawford D. M., Walls M. L., Gentzler K. C., Hoyt D. R. Mental and substance use disorders from early adolescence to young adulthood among indigenous young people: Final diagnostic results from an 8-year panel study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2014;49:961–973. doi: 10.1007/s00127-014-0825-0. doi:10.1007/s00127-014-0825-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitesell N. R., Asdigian N. L., Kaufman C. E., Big Crow C., Shangreau C., Keane E. M., Mitchell C. M. Trajectories of substance use among young American Indian adolescents: Patterns and predictors. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2014;43:437–453. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-0026-2. doi:10.1007/s10964-013-0026-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitesell N. R., Kaufman C. E., Keane E. M., Crow C. B., Shangreau C., Mitchell C. M. Patterns of substance use initiation among young adolescents in a Northern Plains American Indian tribe. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2012;38:383–388. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2012.694525. doi:10.3109/00952990.2012.694525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitesell N. R., Mousseau A., Parker M., Rasmus S., Allen J. Promising practices for promoting health equity through rigorous intervention science with indigenous communities. Prevention Science. 2020;21:5–12. doi: 10.1007/s11121-018-0954-x. doi:10.1007/s11121-018-0954-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiechelt S. A., Gryczynski J., Johnson J. L., Caldwell D. Historical trauma among urban American Indians: Impact on substance abuse and family cohesion. Journal of Loss and Trauma. 2012;17:319–336. doi:10.1080/15325024.2011.616837. [Google Scholar]

- Yu M., Stiffman A. R. Culture and environment as predictors of alcohol abuse/dependence symptoms in American Indian youths. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2253–2259. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.01.008. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zapolski T. C. B., Clifton R. L. Cultural socialization and alcohol use: The mediating role of alcohol expectancies among racial/ethnic minority youth. Addictive Behaviors Reports. 2019;9:100145. doi: 10.1016/j.abrep.2018.100145. doi:10.1016/j.abrep.2018.100145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]