Abstract

Personalized Medicine, or the tailoring of health interventions to an individual’s nuanced and often unique genetic, biochemical, physiological, behavioral and/or exposure profile, is seen by many as a biological necessity given the great heterogeneity of pathogenic processes underlying most diseases. However, testing, and ultimately proving the benefit of, strategies or algorithms connecting the mechanisms of action of specific interventions to patient pathophysiological profiles (referred to here as ‘intervention matching schemes’ (IMS)) is complex for many reasons. We argue that IMS are likely to be pervasive, if not ubiquitous, in future health care, but raise important questions about their broad deployment and the contexts within which their utility can be proven. For example, one could question the need to, the efficiency associated with, and the reliability of, strategies for comparing competing or perhaps complementary IMS. We briefly summarize some of the more salient issues surrounding the vetting of IMS in cancer contexts and argue that IMS are at the foundation of many modern clinical trials and intervention strategies, as in basket, umbrella and adaptive trials. In addition, IMS are at the heart of proposed ‘rapid learning systems’ in hospitals, and implicit in cell replacement strategies such as cytotoxic T-cell therapies targeting patient-specific neo-antigen profiles. We also consider the need for sensitivity to issues surrounding the deployment of IMS and comment on directions for future research.

Keywords: Cancer, Genomics, Treatments, Algorithms, Clinical Trials, Biomarkers

Introduction

The results of most clinical trials suggest that many drugs and medical interventions (e.g., diets, behavioral programs, procedures, etc.) do not work in everyone.[1] This could simply reflect the fact that humans differ with respect to the underlying disease pathologies they have, as well as the ways in which they respond to various interventions, making it unlikely that an intervention designed to specifically correct the pathology underlying one individual’s disease will correct another’s. Although there is debate about the best way to quantify the number of individuals likely to respond to specific interventions,[2, 3] there is little doubt that interventions need to be provided to individuals in a way that better match the pathologies they have. In fact, the application of a number of high-throughput, data-intensive assays and monitoring schemes, such as those rooted in DNA sequencing, imaging protocols and wireless monitoring devices, has revealed a great deal of insight into very specific, often genetically-mediated and nuanced, pathobiological heterogeneity underlying most diseases.[1]

Given that the heterogeneity underlying most diseases is inconsistent with the belief that single interventions will work ubiquitously (ii.e., for every individual suffering from a particular disease), better ways of matching interventions to patient profiles – whether reflecting genetically-mediated pathologies, exposure history, or behavior – will have to be developed. If multiple interventions are designed for a single disease class (e.g., cancers) whose mechanisms of action are specific to certain pathological profiles (e.g., EGFR mutation-positive lung cancer), then providing those interventions to appropriate patient subgroups based on their profiles will require ‘intervention matching schemes (IMS)’ for their deployment and use in clinical settings. Such IMS would basically amount to a set of rules for using one intervention over another depending on what is learned about the underlying pathology of a patient after he or she is profiled appropriately.

The growing literature on ‘personalized,’ ‘individualized,’ and/or ‘precision’ medicines, reinforces the belief that aspects of clinical care in the future will involve the deployment and use of IMS of some sort.[1] However, testing IMS to make sure they work will not necessarily be trivial. This is because a reliable IMS must ensure that: 1. each relevant intervention implicated in it will work in the confined settings in which it was designed to work; 2. the method for profiling the patients to reveal pathologies to be matched to the interventions is appropriate; and 3. the overall matching scheme is optimal relative to other IMS making use of different interventions and/or profiling strategies. This last issue is important since new interventions and profiling strategies are in constant development and could be used to construct alternative IMS whose relative merits could be compared. In this review, we consider some of the challenges associated with proving the value of IMS in a number of settings involving cancers. We note that much of our discussion is relevant to other diseases. We also suggest that whether acknowledged or not, many current cancer therapeutic strategies are rooted in IMS of some sort and therefore may need to be acknowledged as such when they are tested for their clinical utility. We also consider the challenges associated with health ‘learning systems’ designed to simultaneously develop and vet IMS through patient outcome surveillance in medical centers. Finally, we also emphasize that, with the emergence of artificial intelligence, ‘big data’ approaches to biomedical research, and the availability of ultra-high-throughput data-intensive technologies such as DNA sequencing, metabolomics, and wearable monitoring devices that can be used to reveal patient profiles, IMS will continue to grow and hence demand greater attention from regulatory agencies and the scientific community as to their reliability and optimality.

Patient Profiling

As noted, the availability of high-throughput biomedical assays of a wide variety (e.g., genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, epigenomics, imaging, wireless monitoring devices, etc.) has made it possible to identify differences between individuals that likely impact their susceptibilities to disease, the precise molecular mechanisms contributing to diseases they might have, their likely response to various interventions or treatments for those diseases, and the probability that they relapse or develop other diseases.[4] The clinical use of these technologies to expose the potentially unique disease profile a particular patient has and then match an intervention to that pathology (via an IMS) embodies, also as noted, the contemporary vision of precision or personalize medicine.[1, 4] However, vetting or testing an IMS based on these use of such technologies is not trivial.

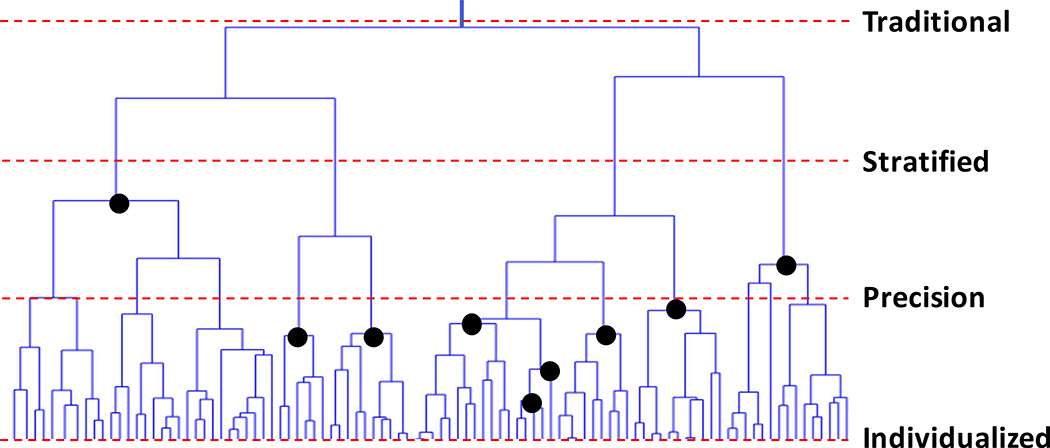

Consider Figure 1, which provides a hypothetical clustering of patients based on their pathophysiologic profiles (e.g., mutation or gene expression profiles exhibited by their tumors) in the form of a tree or dendrogram. Each vertical line in the bottom most levels of the tree represent individual patient profiles. In addition, patient profiles near each other in the tree have similar profiles, and profiles separated by some distance (and reflect the ‘branching’ in the tree) are less similar. Patients with similar profiles thus cluster together. The dashed lines indicate positions in the tree where common interventions could be provided to the subgroup of patients reflected in the clusters below that line since these patients have more in common than with other patients. Terms often used to define intervention strategies (i.e., what amount to IMS) at those places in the tree are provided as well. Note that these strategies make assumptions about how much variation individual patients can exhibit before they must be treated differently from others. Thus, ‘traditional’ (or ‘one size fits all’) interventions are provided to everyone irrespective of differences in their profiles; ‘stratified’ interventions assume that only a few subgroups of patients need to be treated differently. Stratified interventions thus make use of a few indicators (or ‘biomarkers’) to define those subgroups; ‘precision’ interventions leverage multiple indicators and multiple treatments and ultimately assume more refined treatment subgroups; and ‘personalized’ (or ‘individualized’) interventions assume that each patient may require a unique intervention or combination of interventions. The darkened circles indicate that treatments could be crafted for subgroups of patients that are not defined by a single horizontal slice of the tree (e.g., as suggested by the lines associated with stratified and precision medicine). The size of a treatment subgroup will reflect the frequency of patient profiles or, more precisely, the frequency of the biomarker combinations defining that subgroup.

Figure 1.

Graphical depiction of the similarity of patient profiles in the form of a dendrogram or tree. Patients with similar profiles cluster together. The dashed lines indicate positions in the tree where common interventions could be provided to the subgroup of patients reflected in the clusters below the line and the terms often used to define treatments at those positions: ‘traditional’ (or ‘one size fits all’ interventions), ‘stratified’ interventions where a few biomarkers are used to group patients into different treatment baskets, ‘precision’ interventions where multiple markers are used, and ‘personalized’ (or ‘individualized’) interventions where each patient is given a unique intervention or combination of interventions. The darkened circles indicate that treatments could be crafted for subgroups of patients that are not defined by a single slice of the tree. The question is what slices of the tree are practical given available interventions and the insights matching those interventions to patient profiles.

With Figure 1 in mind, it is arguable that the goal of modern medicine is to determine the optimal cut-points for treating individuals and developing interventions, if not currently available, where needed; i.e., do we need 2–3 drugs to successfully treat everyone based on what is revealed by profiling the pathology patients possess (i.e., stratified medicine) or does everyone need their own drug (i.e., personalized or individualized medicine)? Note that the costs and logistical hurdles associated with the deployment of the interventions and the assays for assessing patient profiles could be important considerations in determining these optimal cut-points. In addition, it is possible that different profiling techniques meant to expose relevant pathologies (e.g., genomic DNA sequencing of a tumor vs. transcriptomic profiling via RNA-sequencing) could result in different subgroupings of patients and hence different IMS. In addition, there may be multiple interventions whose mechanisms of action are similar enough that one may want to determine if one is better than another or could be used with a unique subgroup of patients. What is more, consideration of different combinations of profiling techniques, as well as different combinations of interventions, could result in many alternative IMS whose value would need to be assessed, raising important questions on how this could be pursued efficiently and with appropriate scientific rigor. All this raises another important facet or challenge of modern medicine: the need to not only stratify the patient population based on a set of biomarkers to identify subgroups of patients likely to benefit from specific treatments, but also the need to vet the biomarkers themselves. Currently, the vetting and approval processes for multiplex or multi-parameter biomarker platforms (like DNA sequencing and transcriptomic profiling) are complex and often focus on single biomarkers as a result (e.g., EGFR gene overexpression). The challenges associated with proving the reliability of a set of biomarkers to stratify a patient population will obviously add to the challenges to identifying better ways of treating patients.

Intervention Matching Schemes: Overt or Implicit?

Matching interventions to patient profiles can be pursued in complex and often subtle ways. In fact, it is arguable that IMS form the basis of a number of widely-used and emerging interventions. Table I provides a list of relevant interventions and intervention strategies that are actually rooted in an IMS. Note that although Table I is of greater relevance to cancer, many of the concepts behind the various strategies have relevance to all diseases. As an example of the complexities surrounding the IMS implicit in a few of the entries in Table 1, consider autologous cytotoxic T-cell therapy. Essentially, batches of replacement cells to be infused in a patient are first grown in vitro from a set of T-cells harvested from that patient. These cells are then made to be sensitive to a possibly unique set of neo-antigens identified in that patient’s tumor and thereby designed to kill the cancer cells. No two patients may have the same set of neo-antigens. Thus, although the overall constructs used as part of the therapy – i.e., modified T-cells – are the same, the actual individual replacement cells made are unique by making them ‘match’ the patient’s tumor neo-antigen profile.[5] The cells made are also unique given that they came from an individual patient, unlike ‘allogenic’ T-cell therapy where cells derived from one patient are infused in another. Different technical strategies and protocols for both identifying the targeted neo-antigens and creating infused cytotoxic T-cells could result in different matches for a patient, creating further variation among potential IMS underlying the strategy. Note that we also include physician intuition-guided choice and physician-assisted choice of interventions as rooted in IMS of a sort. Consider the fact that physicians are trained according to different styles, criteria, curricula, social circumstances, etc. across different medical schools, both national and international, despite advocacy for specific standards in training and established licensing practices. The different training programs and post-training physician experience will undoubtedly influence the way physicians choose interventions for their patients and could warrant tests of their effects on patient outcomes.

Table 1.

Cancer interventions that assume strategies for matching interventions to patient characteristics.

| Technology/Strategy | Example Reference | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Tumor Perturbation Rules | Simon and Roychowdhury (2013)[69] | Rules for choosing specific Rx based on patient profile |

| Combination Drug Rules | Lazar et al. (2015)[70] | Rules to pick out >1 Rx based on patient profile |

| Connectivity Map | Lamb et al. (2006)[8] | Choose drugs ‘reversing’ disease GEx signature |

| Network Analysis | Barabasi et al. (2011)[71] | Find best drug targets from interaction maps |

| Sequential Administration | Koopman et al. (2011)[72] | Provide drugs in sequence (via biomarkers?) |

| Multitarget Therapies | Galloway et al. (2015)[73] | Single compounds known to hit > 1 target |

| Immunotherapeutics | Kreiter et al. (2015)[5] | Neo-antigen targeting via cytotoxic T-cell therapy |

| RNAi/Antisense Therapies | Haussecker et al. (2015)[74] | Repress GEx via constructs that bind to DNA |

| In Vivo Tumor Implants | Jonas et al. (2015)[75] | Test drug effects on tumor in vivo |

| Tumorgraft Models | Stebbing et al. (2014)[76] | Test drug effects on tumor engrafted mice |

| In Vitro/Ex Vivo Assays | Crystal et al. (2014)[77] | Test tumor drug sensitivity in vitro |

| Engineered Cell Replacement | Golchin and Farahany (2019)[78] | Modify patient-unique defects in replacement cells |

| Dosing via Biomarkers | Schuck et al. (2016)[79] | Set treatment dose per, e.g., patient genotype |

| Delivery Schedule via Biomarkers | Innominato et al. (2014)[80] | Time of drug administration is based on diurnal patterns |

| Physician Intuition | - | Decisions based on physician training and experience |

| Physician-Assisted Choice | - | Decision support by external data and publications |

Key: GEx = Gene expression signature.

The entries in Table I raise questions about how such IMS can be vetted and compared appropriately to prove their ultimate utility. Many of the entries in Table I also involve complex manufacturing needs for the reagents and profiling technologies they exploit. For example, for some entries in Table 1, their deployment assumes real-time patient profiling and tailored intervention manufacturing and thus may require a departure from a traditional ‘officinal’ mode of production (where interventions are created, stockpiled and then chosen for use by a physician) to a ‘magistral’ mode of production (where the interventions are created in real time as close to the bedside as possible), which raises questions about the need to vet this aspect of their deployment (see the Discussion section below). Unfortunately, testing, and ultimately proving the value of, IMS so that they can be deployed with confidence into the health care system is not trivial, as argued throughout this review. One could imagine situations in which different IMS have been used on, or are available for, a patient that suggest different intervention choices. For example, consider the rules-based intervention recommendations produced by IBM’s Watson computing system[6, 7] vs. those derived from the Connectivity Map (CMap)[8]. These situations may motivate or warrant studies to see which of these IMS outperforms the other. Although this activity is consistent with the historical pursuit of large-scale comparative trials of various interventions (e.g., Atorvastatin vs. Simvastatin[9]; or Golimumab vs. Adalimumab[10]), relevant comparative studies may be complex and time-consuming for many reasons, not the least of which is the pace at which new strategies for linking interventions to individual patient profiles is accumulating, as reflected in Table 1. This complexity would be very pronounced if one wanted to compare the effects of different disease-specific IMS on overall health care metrics in the population at large (e.g., lower mortality rates).

Testing Intervention Matching Schemes

A number of novel clinical trial designs have been proposed that test the effects of multiple drugs matched to patient tumor genomic profiles. The overarching hypothesis behind many of these designs is that by guiding patients to specific drugs (e.g., Herceptin) based on their tumor genomic profile (e.g., HER2 gene overexpression) they will have better outcomes than providing drugs to those patients in a way that is not based on the use of patient tumor genomic profile information (e.g., based on standard-of-care practices without the use of genomic information).[11, 12] This overarching hypothesis could be tested in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) by having patients randomized to a group who would be provided drugs based on their genomic profiles or to a group that would be provided drugs not based on their genomic profile.[12] Interestingly, the fraction of individuals that would currently benefit from a specific drug given their genomic profile – essentially the fraction of the population whose tumor mutation profile matches or suggests a link to the activities of specific drugs – has been estimated to be less than 15%, suggesting that more comprehensive insights into how drugs can be tailored to specific genomic profiles needs to occur.[13] We note, however, that improvements in matching drugs to patient profiles is ongoing, so this estimate of 15% is likely an underestimate at this time. The number and type of matches (i.e., treatment arms) in a trial designed to vet multiple drugs simultaneously is not trivial to determine and therefore often very assumption-laden, especially in the light of the recognition of the realities of intra-tumor heterogeneity (i.e., the fact that the cells making up a tumor may themselves be more or less responsive to a particular treatment).[12, 14] In fact, the specific rules for matching drugs to individual patient genomic profiles in relevant trials (e.g., such as in the case of many proposed, ongoing or completed basket, umbrella or certain adaptive trials[12]) ultimately define an IMS, but these rules could be questioned and alternative rules invited whose benefits relative to an original IMS may require vetting. In addition, testing the IMS itself against an alternative such as standard of care in an RCT setting raises important design, analysis and interpretation issues.

To expose some of these issues, suppose there are 10 different features that often occur independently (e.g., tumor mutations) that, when identified in individual patients’ tumors, suggest one of 10 different drugs should be used (i.e., one unique drug for each mutation). The resulting IMS can be tested for producing better outcomes than standard of care. However, what if there are alternative drugs that could treat the pathology associated with one or more of the features used to match the drugs? What if there are more than 10 reasonable features that could be used to match drugs, or what if one of the features is less well documented as likely to indicate a drug? Should the fraction of patients getting the drug matched to the less well-characterized features in a trial be downweighted in the final analysis comparing the IMS to standard of care? What if there are other features beyond those considered in the original IMS that may reliably indicate which drugs should be matched to a patient’s tumor profile (e.g., gene expression levels and not just the presence or absence of a mutation)? What if there are combinations of drugs that may better combat (and hence match) a patient’s tumor’s features? Should each of the alternative IMS resulting from these possibilities have to be tested against the original IMS? If more than one of these possibilities arose, how complicated would the resulting IMS derived from their combined use be?

Another issue in testing IMS involves the efficacies of the individual drugs. What if one or some subset of the 10 drugs used to formulate the IMS are simply not effective whereas the other drugs are? Could the individuals exhibiting poor outcomes in the trial because they received the less efficacious drugs reduce the overall efficacy of the IMS to the point where it does not show overall improvement relative to standard of care? One could pursue post-hoc analyses of each drug in a trial comparing an IMS to an alternative like standard of care, but such analyses raise concerns about false positive and negative findings and power issues since a study like this would probably be powered to test the overall difference in efficacy exhibited by the group of individuals receiving drugs based on the IMS and those receiving drugs based on the alternative and not the efficacy of each individual drug. The SHIVA trial, that included 10 drug treatment-genomic profile matches, resulted in the acceptance of the null hypothesis that the IMS would produce no better outcomes than standard of care, suggesting that the IMS would not benefit patients over-and-above standard of care.[15] However, questions about the number of patients provided specific treatments, the drugs used, and the confidence in the matching scheme have been raised,[16, 17] especially in the light of re-analyses of the original trial’s data.[18] Note that in this vein, it is entirely possible that the drugs considered in an IMS are all efficacious, and the profiling used to match patients to those drugs does indeed identify treatment-relevant phenomena in patients’ tumors, but the way drugs are matched to the profiles is problematic.

The upfront design of a trial seeking to test the utility of an IMS against an alternative using, e.g., randomization, can be problematic for many reasons, including those that have been debated in the context of standard RCTs.[19, 20] The use of randomization could also raise ethical concerns about the conduct of a trial. Consider a trial testing an IMS against standard-of-care. Individuals could be randomized when enrolled in the trial into a group receiving IMS-guided drugs or a group receiving standard of care. However, if individuals enrolled into the IMS arm do not have any of the features in their tumors that the IMS is based on, they could not contribute to the trial as they would likely be given standard of care or an alternative to the IMS. Worse yet, they could be included in the trial evaluation and attenuate the true efficacy of the IMS, as it may be the case that individuals without one of the profiles implicated in the IMS are generally more difficult to treat and have poorer outcomes. Depending on how frequently the tumor profiles are implicated in the IMS, this could result in a wasted profiling effort as well. An alternative strategy would be to profile individuals at the start of the trial, prior to randomization. If an individual does not have a relevant profile, then they are not enrolled in the trial. If they do, then they are randomized to either the IMS group or standard of care group. However, for patients with a profile implicated in the IMS, there may be a belief that the drug they get will be superior to what they would have received under standard of care given what is known about the mechanism of action of the drug and its role in the IMS. Randomizing these patients to standard of care would thus relegate them to a treatment strategy that is likely inferior to what they would have received had they been randomized to the IMS group. This issue creates ethical concerns, and revolves around beliefs about equipoise; i.e., the state in which there is no a priori reason to believe that the IMS will result in better outcomes than standard of care).[21] In addition, although not without problems, one could try to make relevant trials of IMS more efficient by foregoing randomization by comparing a group of patients being prospectively treated based on an IMS against historical control patients treated with standard of care but for whom relevant follow-up data are available from, e.g., Electronic Medical Records (EMR).[22]

Another dilemma associated with testing IMS in an RCT framework is the need to ‘lock down’ the rules implicated in the IMS at the start of the study and not change them throughout. Although not unreasonable, this can be complicated if new information about, e.g., the match between a specific profile and drug emerges after the trial is initiated, or a new drug or profile is identified that could complement those implicated in the initial IMS. One could imagine few people enrolling in a study of an IMS if it does not consider new and compelling insights about a match that could conflict with one in the initial IMS. Although this issue arises in tests of any drug or intervention irrespective of its being considered as part of an IMS, since IMS embrace multiple drugs and patient profiles they run a greater risk of having one arm in them being compromised by new insights developed after the trial was initiated. Aspects of this issue were at play in the conduct of the BATTLE trial.[23, 24] If allowance were made to adapt the rules implicated in the IMS as the trial unfolds, then one could ask if the patients enrolled later in the trial should be weighted more heavily in the analysis of the outcomes since they would effectively be treated with a more sophisticated version of the IMS than those at the start of the trial. Although some adaptive designs can accommodate changes in the way in which individuals are treated throughout a trial based on accumulating data as part of the trial,[12, 25] such designs do not often consider information arising outside the trial while it is being pursued (e.g., a new publication describing a new match between a drug and relevant tumor profile). Issues surrounding the vetting of IMS that change over time are discussed in the section on ‘Real-World Data Learning Systems’ below.

A final comment about vetting IMS is that they can be conceived of broadly, as Table 1 and the discussion so far make clear. For example, it is now routine for physicians to recommend that patients participate in specific clinical trials – trials that possibly only test a single drug – on the basis of profiling they may have pursued during a clinical office visit (e.g., via an order of a standard laboratory or commercial tumor profiling assay). In fact, there are now various resources and commercial entities that can facilitate such matching. These resources use what amounts to an IMS in the process, though not as part of a single study.[26] A reasonable question is whether the schemes used to match patients to individual trials (i.e., the implicit IMS) has merit or is flawed. Addressing this question could be further motivated because different profiling techniques might be used to recommend different trials, different trials could test different drugs for the same conditions, or some drugs have less well-documented matches to a patient profile obtained in a certain way. Testing the outcomes of a trial exploring an IMS implicated in an overall patient-trial matching scheme to, e.g., standard of care would be complicated and likely filled with all sorts of potential biases, such as patient pre-existing conditions, prior treatments, etc.

Prevention and Screening

Strategies for testing IMS in cancer treatment settings could be extended to cancer prevention settings. Few, if any, such prevention-based IMS have been proposed that are undergoing testing. Part of the reason for this is the belief that, despite the fact that there are some promising chemopreventive drugs that could motivate studies of their effectiveness, efforts would be better spent getting people to adopt lifestyles that are proven to reduce cancer risk.[27] However, although cancer related mortality is decreasing due to improved treatments, cancer incidence has not changed dramatically over the past 50 years,[28] highlighting the need for further development of effective prevention strategies.[29, 30] Unfortunately, outside the known behavioral modifications that can reduce risk, there are currently no clinically proven medications that clearly show greater benefits than risks for prevention in the general population, suggesting a need to quickly assess the utility of candidate chemopreventive agents, if any. In addition, the routine use in unaffected individuals of chemopreventive interventions, such as aspirin for colorectal cancer and tamoxifen for breast cancer, is usually limited to those deemed higher risk based on, e.g., genetic profiles, family history, or comorbid illness, raising questions about the utility of the interventions in the general population.[31] Compounding this issue is the fact that the uptake of chemoprevention regimens in high risk populations is poor due to anticipated negative side effects of their long term use.[32] As a result, recent clinical trials for chemopreventive drugs have focused on altering the dose of the various chemopreventive agents and medications - so called short term intermittent therapy[33] - to decrease the associated toxicities.

Testing chemopreventive agents on high risk individuals further requires a means for identifying those high risk individuals, and thus is where parallels between cancer prevention and cancer treatment studies can be drawn. For example, the development of polygenic risk scores (PRS) to identify individuals with elevated lifetime risks of various diseases has been shown to have the potential to inform prevention strategies for individuals with cardiovascular or metabolic diseases,[34, 35] and one could imagine a more comprehensive analysis of an individual’s risk for multiple genetically-correlated diseases leading to more refined and personalized risk mitigation strategies for which an IMS could be constructed.[36] In fact, the potential for exploiting multiple assays to profile patients (e.g., genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, etc.), combined with machine learning algorithms to identify patterns that could shape different chemoprevention strategies that could form an IMS, is being considered for metabolic diseases.[37, 38] In this light, it has been proposed recently that cancer screening programs could be optimized by having individuals even at ‘average’ risk enter into national screening programs where they are randomized to different arms of a study involving different screening tests, different intervals between tests, different profiling assays to assess risks, and different thresholds for declaring tests as consistent with a positive or negative result – all consistent with the construction of an IMS.[39]

Implementation and The Role of Tumor Boards

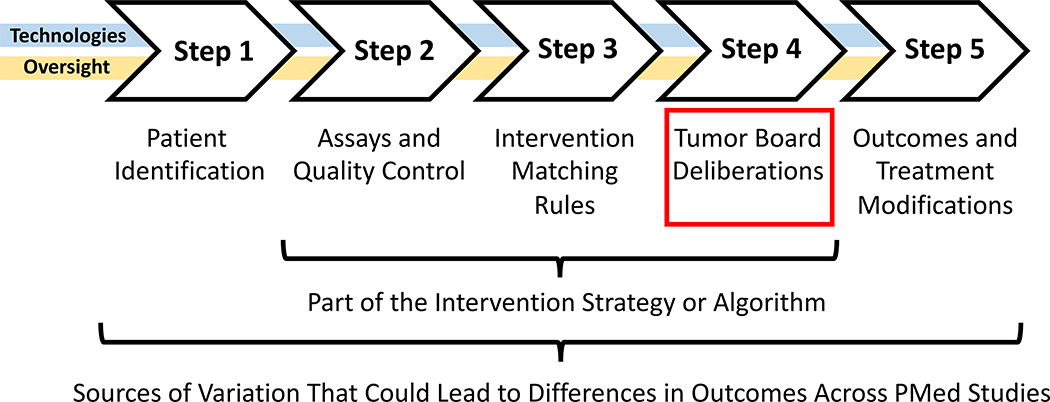

In order to conduct a clinical trial investigating the utility of an IMS – say via a basket or bucket trial like the SHIVA, BATTLE and related trials[12, 15, 23], or a trial of anyone one of the intervention strategies list in Table 1 – safeguards need to be put in place to avoid any untoward consequences of the use of different interventions as each may have its own unique safety profile. This is especially true if the trial is to have buy-in or approval from regulatory agencies (e.g., as with trials registered on www.clinictrials.gov). In addition, workflows for processing patient profiling data, determining which intervention a patient should receive, tracking the outcomes of the patients, etc. all need to be in place, each of which could contribute to, be encompassed by, or confound if not put together well, the IMS being tested. Figure 2 provides a basic schematic that depicts the needed elements for testing a cancer-based IMS. We discuss three of the more salient issues in the implementation of tests of an IMS below, arguing that greater sensitivity needs to be given to these issues to maximize generalizability, comparability, and ‘deployability’ of their results.

Figure 2.

Paradigmatic workflow for advancing information in a typical basket trial in cancer settings. Note that the ‘algorithm’ matching interventions to patient profiles is one part of the workflow, with the assays being used to probe elements that could connect the interventions to the drugs as well as the tumor board deliberations having important roles to play in the outcomes of the trials. Note ‘PMed’ = ‘Precision Medicine.’

First, after a patient has been identified who might benefit from the IMS or meet criteria for testing the utility of the IMS, they have to be profiled (Steps 1 and 2 of Figure 2). This can involve different enrollment criteria, assays, standards, and quality control methods that might be unique to the IMS being tested, which could compromise generalizability of the results of the study. In addition, the time it takes to profile the patient and determine a treatment based on the IMS could require elaborate infrastructure that may make generalizability difficult. As an example, the G.E.M.M. trial investigating the utility of an IMS for individuals with BRAF wild type melanoma who had failed other treatments raised important questions and discussions with the US Food and Drug Administration.[40] Essentially, there was a need to minimize any potential for inaccuracies involving the assays used to profile the patients by using strict standards and quality control (QC) measures (i.e., to avoid the proverbial ‘garbage-in, garbage-out’ issue). This need for quality was compounded by the need for speed, since most BRAF wild-type melanoma patients who have failed other treatments have only a few months to live.

Variation in not only the assays used (e.g., expression profiling vs. genomic sequencing), the technology used for the assays as each may have their own performance metrics (e.g., Illumina sequencing vs. Pacific Biosciences sequencing technologies[41]), as well as the QC procedures used, could ultimately contribute to variation in outcomes that may impact their generalizability and comparability. This is also consistent with another point made earlier: the actual rules encompassed in a particular IMS (Step 3 of Figure 2) might differ from other IMS designed for the same disease setting, raising the question as to whether the community might benefit from comparing the outcomes associated with these different IMS. Of course one could expose variation in the rules used by each IMS by looking at them and simply comparing them, but some rules might be complicated if a number of conditionals (i.e., ‘if-then’ propositions) are used or they are determined by complicated machine learning strategies (See the section on ‘Learning Systems’ below).[14, 42, 43]

Second, treatment decisions for patients must be made in as ethically and clinically sound a way as possible, and to ensure this at some level in cancer settings, many treatment decisions are made after a ‘tumor board,’ made up of physicians, researchers and patient support staff, deliberates on the best course of action (Step 4 of Figure 2). This is usually the case even in settings in which an individual is enrolled in a clinical trial and expected to receive an experimental treatment. Most IMS are designed to support or inform the decision-making abilities of physicians, not necessarily replace them, so incorporating tumor boards in studies vetting IMS makes sense and helps enlighten physicians about the mechanics and bases for an IMS. In this light, how the tumor board functions within the context of a study vetting an IMS, especially in terms of its composition (e.g., the experience and credentials of the members), timelines under which the trial is operating, rules about the need for a quorum for each decision, etc., could create variation between institutions evaluating an IMS or between outcomes associated with different IMS tested at different institutions.

An important question regarding studies investigating an IMS involves how tumor board recommendations are factored into the analysis of the results, if at all. For example, if the IMS suggests one drug for a patient but the tumor board decides to use on another, problems in how to incorporate or remove this patient’s outcome from the analysis arise. It may be the case that the individual enrolled in the study in this situation is simply withdrawn from the study, but the insights about why the tumor board’s recommendation was not to go with the intervention chosen by the IMS could be invaluable for refining the IMS going forward (e.g., the individual in question had an another condition that could have been exacerbated by use of the intervention chosen by the IMS and this connection between the secondary condition and the drug chosen by the IMS was not factored into its underlying rules). In addition, if the IMS merely ranks interventions in terms of their applicability to an individual based on his or her profile, ultimately providing the tumor board with options, as in the G.E.M.M. trial, then an important question is how the variation in the ranks of the interventions chosen by the tumor board is factored into the analysis of the outcomes is important (e.g., one patient is given the third ranked drug and another is given the first ranked drug). One could ask, for example, if the individuals should be weighted in the analysis of the trial outcomes by the degree of discrepancy between the IMS-dictated outcome and the tumor board decisions. In this light, the tumor board deliberations themselves, given that they might vary from study setting to study setting, are part of an IMS (as reflected in the last row of Table 1).

A third overarching issue involves the choice of patient outcomes used to evaluate the utility of the IMS (e.g., progression free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS), RECIST criteria, etc.[44]). Variation in the criteria used to evaluate the utility of an IMS can create challenges for comparing different IMS. In addition, it is quite clear that reliable surrogate endpoints for evaluating tumor response would be better than using survival-based endpoints. PFS ratio,[45] circulating tumor DNA,[46] tumor shrinkage evaluation involving imaging endpoints, etc.[47] all have potential in this regard, but could create yet another source of variation in comparing the utility of various IMS if these different outcomes and protocols for measuring are them are used in different studies.

Real-World Data Learning Systems

As an alternative to standard prospective RCTs investigating the utility of IMS, there is growing consensus on the value of leveraging ‘real-world data’ (i.e., data collected during the course of routine clinical practice that includes appropriate outcome monitoring) to identify patterns in intervention responses that might inform clinical practice going forward.[48–50] How real-world data is actually analyzed and incorporated into studies is important, as there are a number of strategies for this. For example, as mentioned previously, it might possible to use real-world data as part of a control arm in testing an experimental intervention or IMS.[22] Of even greater interest with respect to the use of real-world data to vet IMS is the proposed development of infrastructure and metrics for creating ‘rapid learning systems (RLS)’ that systematically collect data on patients treated with different interventions who have been profiled in various ways. By examining trends in the data and finding associations between patient profiles, interventions and outcomes, then predictive rules and an IMS can be created that could inform care going forward. As new data are collected, the IMS can be re-evaluated, updated, modified, parts of it abandoned or replaced, etc. in order to create better IMS that are themselves constantly updated in perpetuity.[51–53]

The infrastructure to create RLS, whether at a single hospital or across the entire US health system, would be complicated but a very laudable vision or goal.[54] At least one largely successful test of a prototype RLS has been reported.[55] However, the metrics used to evaluate an RLS and show that its updates are leading to improvements could be based on a number of important health care goals. For example, would overall survival, reduced side-effects, patient satisfaction, reduced costs, or some combination of all of these, be used to guide the system? If such metrics could be identified with appropriate consensus, the use of RLS may actually lead to less reliance on expensive, often highly-contrived and logistically-complex phase III clinical trials for determining the utility of IMS.[56] Thus, if specific drugs or interventions are found to be non-toxic in pre-clinical studies and Phase I trials, and exhibit efficacy in Phase II studies, then it is arguable that they should be approved for use within the confines of an RLS. This would allow the profiles of patients likely to benefit most from the use of these drugs can be determined quickly and empirically with real-world data encompassed by, and contributing to, a broader ever-evolving IMS.

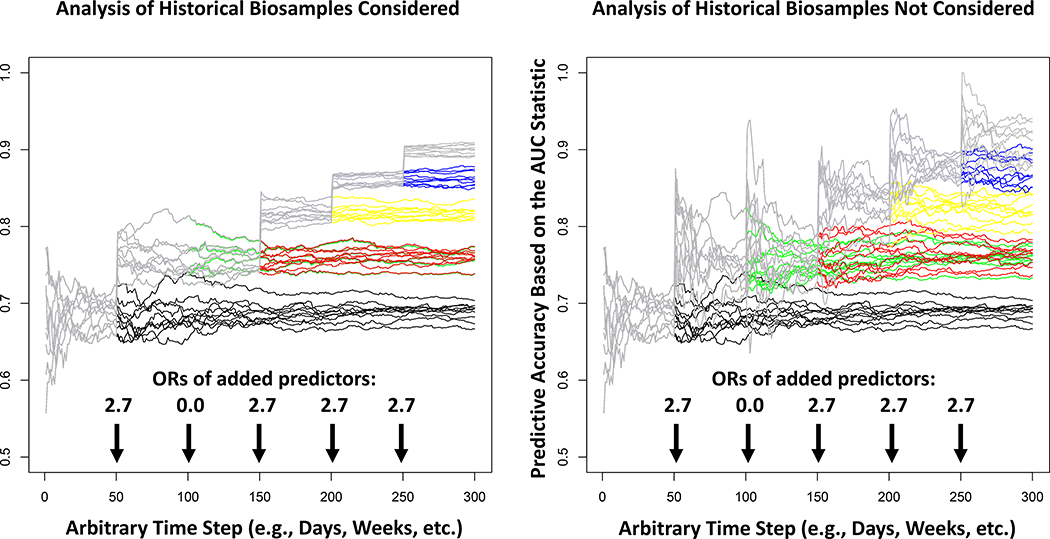

The analysis of the data obtained from an RLS could also pose challenges. For example, since the predictions of which individual patients should be provided each intervention based on their profile (i.e., the IMS) would be based on patient data and outcomes collected over time, any updates to the IMS would be evaluated with data on future patients. After the evaluation of the predictions, the data on the outcomes of the new patients would be combined with the legacy patients’ data used to construct the initial IMS to build a more refined IMS. This practice would create serial correlations between the underlying rules and predictive models governing the IMS over time, as depicted in the results of the rudimentary RLS simulation studies in Figure 3 (details about how the simulations were pursued are provided in the Supplemental Material). Serial correlations could create statistical analysis issues in comparisons of, or combining, information across, e.g., different hospitals, especially if patients with different backgrounds (e.g., ancestral, treatment history, etc.) are evaluated at those hospitals. Serial correlation must also be accommodated in inference and hypothesis testing strategies for evaluating improvements in the IMS over time.[57] In addition, as new profiling techniques are added to the system to expand and improve the underlying IMS, their impact on outcomes will need to be contrasted with outcomes obtained with the previously used techniques in order to determine how well they improve the system and its underlying IMS (e.g. consider the improvement in performance of the system simulated in Figure 3 when a new profiling assay or biomarker of treatment response is introduced). Finally, if legacy biomaterials (e.g., biopsied tumor material) are not saved for the evaluation of new profiling assays (e.g., proteomic or metabolomic assays developed in the future that might indicate an intervention match) then one would conceivably have to start from scratch in order to evaluate the utility of an IMS that includes them (contrast the left and right panels of Figure 3). Ultimately, the design, analysis and behavior of RLS will be good research topics for the applied mathematics and bioinformatics community.

Figure 3.

The behavior of the accuracy, in the form of the traditional area-under-the-receiver-operator-curve (AUC; y-axis), of the logistic regression-based predictions of patient response to an intervention over time for 10 simulated learning systems. The logistic regression models underlying the predictions are continuously updated based on 100 new patients’ worth of data every hypothetical day (x-axis). New predictors of response are added at the times indicated by the arrows with the odds ratios (ORs) of response associated with those predictors reflected by the numbers above those arrows. The left panel assumes that patients have stored biospecimens that can be assessed when a new assay is introduced and the right panel assumes that this is not the case, so the new models must be seeded with 100 patient’s worth of data that include the new assay and then allowed to evolve with new patient data going forward. The gray lines depict the behavior of the 10 simulated systems if all 5 predictors are used as they come online (note: the second predictor was assumed to have a 0 effect size and all others were assumed to have an OR of 2.7). The different colored lines indicate how the system would behave if the additional predictors were not added to the predictive models over time as they come online.

An even more complicated set of issues surrounding the development of an RLS involves the nature of the rules that govern the underlying (yet evolving) IMS. Consider that the IBM Watson system can be seen as a potential engine for an IMS underlying an RLS, as IBM Watson leverages the continually expanded medical literature to formulate its rules. Ultimately, IBM Watson and related systems take in patient data, extract profiles of relevance for potential interventions, and then ‘recommend’ an intervention or clinical trial. IBM Watson has been shown to compare favorably with physician-guided treatment decisions, although there is debate about the merits of the results of relevant studies.[6, 7] However, there are alternatives to IBM Watson that leverage different algorithms or strategies for automating intervention decisions, so a good question is whether or not these alternatives could outperform IBM Watson in a head-to-head comparison. Thus, the need to vet different underlying strategies governing an RLS might be an issue in the future, if an RLS was not created that evaluated the rules underlying each in an all-encompassing IMS.

There are also a number of thorny ethical questions that surround the use of an RLS and its underlying and evolving IMS. For example, if the rules used in the IMS are very complicated – as, say, the use of deep learning techniques might entail, as the input-output relationships underlying the rules many not be easily explainable – then how much faith the community might put into them could become an open question. This would especially be the case if these rules conflict with consensus physician intuitions about the utility of, and use settings associated with, various interventions.[58] Finally, relying on automated systems to recommend interventions in complicated ways may invoke sensitivities surrounding the avoidance or prevention of any undesirable behavior they might exhibit.[59]

N-of-1 Trials

There is a growing literature on N-of-1 or single subject clinical trials.[2, 20] N-of-1 trials are designed to draw inferences about a specific individual’s response to a particular intervention, or set of interventions. They are considered the epitome of investigations seeking to ‘personalize’ interventions (i.e., conducted to find out what works for each individual, rather than a group of individuals with a common profile, as reflected in the lowest horizontal line in Figure 1). N-of-1 trials can, and often do, make use of many standard statistical and design techniques used routinely in clinical trials of all sorts (e.g., randomization, cross-over periods, blinding, the use of washout periods to minimize carry over effects, etc.).[60] Unlike standard population-based clinical trials, however, which focus on the utility of an intervention in the population at large – and hence do not collect detailed information on any one subject in those trials – N-of-1 trials focus on collecting as much information about a response to an intervention on an individual as possible to maximize power to determine if that individual is an unequivocal responder or non-responder to a particular intervention. Most N-of-1 trials make use of cross-over designs in which individuals are provided alternative interventions (possibly including a placebo) in order to contrast responses to those interventions. This makes them less than ideal for use in settings in which an acute, life-threatening condition is of interest, since there will not likely be enough time to try out different interventions for the sake of generating scientific contrasts. However, N-of-1 trials can be used with great effect to identify and help define potential IMS in appropriate settings, can be used to vet IMS, and can also be considered an IMS when conducted more broadly, as explained in the following.

Because they focus on individual responses to interventions and are powered to do so, N-of-1 studies can be used to identify individuals that unequivocally respond and do not respond to a particular intervention. The individuals who have participated in N-of-1 trials of the same intervention and found to respond to that intervention can then be scrutinized for characteristics they have in common (e.g., a specific genotype). The common characteristic can in turn be used in future studies to profile and identify individuals likely to respond to the relevant intervention. Gathering response information in this manner has been suggested in the evaluation of off-label use of cancer drugs, although sophisticated designs vetting these off-label drugs have not often been pursued.[61] Of course, the nature of the response phenotype is crucial to such studies. For example, as was pointed out, some settings may complicate the use of N-of-1 trials because of their acute and life-threatening nature. For cancer, standard PFS and OS measures would not make sense to use, although the PFS ratio – a measure of the effects of two drugs administered sequentially on an individual patient – may have utility.[18, 45] In addition, other phenotypes mentioned earlier, such as circulating tumor DNA[46] or imaging-based markers of tumor shrinkage might be used.[47] In addition, studies focusing on easily measured cancer-related phenotypes, as well as associated treatment effects, such as pain, mood, sleep or cognitive abilities, could be pursued in N-of-1 settings using wearable digital health monitoring devices or apps.[60]

N-of-1 trials can be pursued to vet IMS. For example, if individuals with different profiles are thought to benefit from specific interventions, then N-of-1 trials could be pursued to test the individual responses, and the results could be aggregated to draw broader inferences about the utility of the underlying IMS.[62] The pursuit of N-of-1 trials in contexts like this could be made efficient by considering adaptive designs.[25, 63] Finally, the very idea of using N-of-1 trials to determine the best treatments for individuals can be considered an IMS and tested as such. Thus, patients could be potentially randomized to a group being evaluated for response to an intervention in an N-of-1 trial based on various profiles, or to a group receiving standard of care. In this way, one could see if the pursuit of N-of-1 trials led to the choice interventions that in turn led to better outcomes than standard of care. In this way, not only could one determine an optimal course of treatment for individual patients, but also seek to justify the expense associated with conducting N-of-1 trials in the first place. A study like this was pursued as part of a global effort to evaluate health care costs for a number of neuropsychiatric conditions.[64, 65]

Conclusions and Future Directions

The future of cancer care will involve interventions that are tailored to individual patient profiles at some level (e.g., Table 1). How those interventions will be vetted, given that they may only benefit a small fraction of the population possessing relevant profiles indicating their appropriateness, is not trivial, but it is quite likely that they will be imbedded in broader IMS that can be tested as such. We have described some strategies for vetting IMS, including a need to possibly compare different IMS, but admit that focused work on the merits of each strategy is called for. This is especially the case in designing real-world data-based infrastructure for testing IMS, such as RLS. We close with just a few comments on some related issues.

First, many strategies for treating cancer patients based on profiles they possess could require new ways of manufacturing and deploying the constructs used in the relevant treatments. For example, as noted, the development of autologous cytotoxic T-cells requires that a patient’s own cells are harvested, sensitized to target the possibly unique tumor neo-antigen profile the patient possesses, and then infused back into that patient’s body. This means that the constructs used in the treatment cannot be taken off a shelf and administered to the patient in the way a patient might obtain a traditional prescribed medicine from their local pharmacy. Rather they must be created in real time as information about the patient’s neo-antigen profile is evaluated and the cells are harvested for sensitization. This form of production for a medicine falls under the definition of ‘magistral’ (i.e., real time) production of medicines as opposed to the more traditional ‘officinal’ (i.e. stockpiled and to be taken off-the-shelf) production of medicines.[66] If magistral production of medicines will become the norm, a shift away from many legacy production, supply chain and distribution methods will have to occur. This could raise questions about the engineering and manufacturing units responsible for the real-time production of the interventions, since each may have their own unique properties and need to be vetted, potentially as a component of a broader IMS.[67]

Second, also mentioned previously, IMS are more or less ubiquitous but not often seen as such, and many implicit IMS are even less likely to be thought of as needing vetting. For example, although not without controversy, hospitals and clinics across the United States coordinate an activity with medical schools designed to ‘match’ graduating students with their residency and fellowship programs.[68] The mechanics behind the match, such as the metrics used, the interview evaluations of the graduates, the criteria used for ranking individuals, etc. all have more global, albeit potentially subtle, effects on the way treatments (and health care generally) are provided to patients. Thus, the system for matching graduates to fellowships can itself be seen as an IMS worthy of investigation. Although probably too vague to be formalized in a trial testing its utility, this example exposes just how broadly the concept of an IMS can be taken and raises further questions about how we can determine their utility.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial Disclosures

Aspects of this work were supported in part by: National Institute on Aging (NIA) grant UH2 AG064706 (NJS); NIA grant U19 AG023122 (NJS); NIA grant U24 AG051129 (NJS); and grants from The Ottesen Foundation (NJS; LHG); Dell, Inc. (NJS, LHG, JL, and JT) and the Ivy Foundation (NJS).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

All authors have declared no competing interests for this work.

Contributor Information

Nicholas J. Schork, The Translational Genomics Research Institute (TGen), Phoenix, AZ Department of Population Sciences, The City of Hope National Medical Center, Duarte, CA; Department of Molecular and Cell Biology, The City of Hope National Medical Center, Duarte, CA.

Laura H. Goetz, The Translational Genomics Research Institute (TGen), Phoenix, AZ Department of Medical Oncology, The City of Hope National Medical Center, Duarte, CA.

James Lowey, The Translational Genomics Research Institute (TGen), Phoenix, AZ.

Jeffrey Trent, The Translational Genomics Research Institute (TGen), Phoenix, AZ; Department of Medical Oncology, The City of Hope National Medical Center, Duarte, CA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ginsberg GS and Willard HF, eds. Essentials of Genomic and Personalized Medicine. 2010, Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schork NJ, Personalized medicine: Time for one-person trials. Nature, 2015. 520(7549): p. 609–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Senn S, Statistical pitfalls of personalized medicine. Nature, 2018. 563(7733): p. 619–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Apweiler R, et al. , Whither systems medicine? Exp Mol Med, 2018. 50(3): p. e453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kreiter S, et al. , Mutant MHC class II epitopes drive therapeutic immune responses to cancer. Nature, 2015. 520(7549): p. 692–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tian Y, et al. , Concordance Between Watson for Oncology and a Multidisciplinary Clinical Decision-Making Team for Gastric Cancer and the Prognostic Implications: Retrospective Study. J Med Internet Res, 2020. 22(2): p. e14122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Somashekhar SP, et al. , Watson for Oncology and breast cancer treatment recommendations: agreement with an expert multidisciplinary tumor board. Ann Oncol, 2018. 29(2): p. 418–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lamb J, et al. , The Connectivity Map: using gene-expression signatures to connect small molecules, genes, and disease. Science, 2006. 313(5795): p. 1929–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stoekenbroek RM, et al. , High-dose atorvastatin is superior to moderate-dose simvastatin in preventing peripheral arterial disease. Heart, 2015. 101(5): p. 356–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomas SS, et al. , Comparative Immunogenicity of TNF Inhibitors: Impact on Clinical Efficacy and Tolerability in the Management of Autoimmune Diseases. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BioDrugs, 2015. 29(4): p. 241–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Le Tourneau C, et al. , Treatment Algorithms Based on Tumor Molecular Profiling: The Essence of Precision Medicine Trials. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2016. 108(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Biankin AV, Piantadosi S, and Hollingsworth SJ, Patient-centric trials for therapeutic development in precision oncology. Nature, 2015. 526(7573): p. 361–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marquart J, Chen EY, and Prasad V, Estimation of the Percentage of US Patients With Cancer Who Benefit From Genome-Driven Oncology. JAMA Oncol, 2018. 4(8): p. 1093–1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schork NJ, Artificial Intelligence and Personalized Medicine. Cancer Treat Res, 2019. 178: p. 265–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Le Tourneau C, et al. , Molecularly targeted therapy based on tumour molecular profiling versus conventional therapy for advanced cancer (SHIVA): a multicentre, open-label, proof-of-concept, randomised, controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol, 2015. 16(13): p. 1324–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Le Tourneau C and Kurzrock R, Targeted therapies: What have we learned from SHIVA? Nat Rev Clin Oncol, 2016. 13(12): p. 719–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Le Tourneau C, et al. , Precision medicine: lessons learned from the SHIVA trial - Authors’ reply. Lancet Oncol, 2015. 16(16): p. e581–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Belin L, et al. , Randomized phase II trial comparing molecularly targeted therapy based on tumor molecular profiling versus conventional therapy in patients with refractory cancer: cross-over analysis from the SHIVA trial. Ann Oncol, 2017. 28(3): p. 590–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deaton A and Cartwright N, Understanding and misunderstanding randomized controlled trials. Soc Sci Med, 2018. 210: p. 2–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schork NJ, Randomized clinical trials and personalized medicine: A commentary on deaton and cartwright. Soc Sci Med, 2018. 210: p. 71–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Freedman B, Equipoise and the ethics of clinical research. N Engl J Med, 1987. 317(3): p. 141–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carrigan G, et al. , Using Electronic Health Records to Derive Control Arms for Early Phase Single-Arm Lung Cancer Trials: Proof-of-Concept in Randomized Controlled Trials. Clin Pharmacol Ther, 2020. 107(2): p. 369–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim ES, et al. , The BATTLE trial: personalizing therapy for lung cancer. Cancer Discov, 2011. 1(1): p. 44–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu S and Lee JJ, An overview of the design and conduct of the BATTLE trials. Chin Clin Oncol, 2015. 4(3): p. 33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chakraborty B and Murphy SA, Dynamic Treatment Regimes. Annu Rev Stat Appl, 2014. 1: p. 447–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.CAN. An Overview of Cancer Clinical Trial Matching Services. 2020; Available from: https://www.fightcancer.org/sites/default/files/CT_MatchingServicesWhitepaper_ACSCAN_May2018Web_0.pdf.

- 27.Weller D and Wender RC, Should we stop investing in chemoprevention trials in oncology? Lancet Oncol, 2019. 20(6): p. 766–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Institute, N.C. Registry Groupings in SEER Data and Statistics. 2020; Available from: (http://seer.cancer.gov/registries/terms.html)

- 29.Albini A, et al. , Cancer Prevention and Interception: A New Era for Chemopreventive Approaches. Clin Cancer Res, 2016. 22(17): p. 4322–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rashid S, Cancer and Chemoprevention: An Overview. 2017, Sinapore: Springer [Google Scholar]

- 31.USPSTF. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.. 2020; Available from: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/.

- 32.Smith SG, et al. , Factors affecting uptake and adherence to breast cancer chemoprevention: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Oncol, 2016. 27(4): p. 575–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu X and Lippman SM, An intermittent approach for cancer chemoprevention. Nat Rev Cancer, 2011. 11(12): p. 879–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khera AV, et al. , Genome-wide polygenic scores for common diseases identify individuals with risk equivalent to monogenic mutations. Nat Genet, 2018. 50(9): p. 1219–1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khera AV, et al. , Polygenic Prediction of Weight and Obesity Trajectories from Birth to Adulthood. Cell, 2019. 177(3): p. 587–596 e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schork AJ, Schork MA, and Schork NJ, Genetic risks and clinical rewards. Nat Genet, 2018. 50(9): p. 1210–1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schussler-Fiorenza Rose SM, et al. , A longitudinal big data approach for precision health. Nat Med, 2019. 25(5): p. 792–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Westerman K, et al. , Longitudinal analysis of biomarker data from a personalized nutrition platform in healthy subjects. Sci Rep, 2018. 8(1): p. 14685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kalager M and Bretthauer M, Improving cancer screening programs. Science, 2020. 367(6474): p. 143–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.LoRusso PM, et al. , Pilot Trial of Selecting Molecularly Guided Therapy for Patients with Non-V600 BRAF-Mutant Metastatic Melanoma: Experience of the SU2C/MRA Melanoma Dream Team. Mol Cancer Ther, 2015. 14(8): p. 1962–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reuter JA, Spacek DV, and Snyder MP, High-throughput sequencing technologies. Mol Cell, 2015. 58(4): p. 586–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Babic B, et al. , Algorithms on regulatory lockdown in medicine. Science, 2019. 366(6470): p. 1202–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Holzinger A, et al. , Causability and explainability of artificial intelligence in medicine. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Data Min Knowl Discov, 2019. 9(4): p. e1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aykan NF and Ozatli T, Objective response rate assessment in oncology: Current situation and future expectations. World J Clin Oncol, 2020. 11(2): p. 53–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Von Hoff DD, et al. , Pilot study using molecular profiling of patients’ tumors to find potential targets and select treatments for their refractory cancers. J Clin Oncol, 2010. 28(33): p. 4877–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Siravegna G, et al. , Integrating liquid biopsies into the management of cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol, 2017. 14(9): p. 531–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Subbiah V, et al. , Defining Clinical Response Criteria and Early Response Criteria for Precision Oncology: Current State-of-the-Art and Future Perspectives. Diagnostics (Basel), 2017. 7(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Khozin S, et al. , Real-World Outcomes of Patients with Metastatic Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Treated with Programmed Cell Death Protein 1 Inhibitors in the Year Following U.S. Regulatory Approval. Oncologist, 2019. 24(5): p. 648–656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Agarwala V, et al. , Real-World Evidence In Support Of Precision Medicine: Clinico-Genomic Cancer Data As A Case Study. Health Aff (Millwood), 2018. 37(5): p. 765–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rudrapatna VA and Butte AJ, Opportunities and challenges in using real-world data for health care. J Clin Invest, 2020. 130(2): p. 565–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Etheredge LM, A rapid-learning health system. Health Aff (Millwood), 2007. 26(2): p. w107–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Abernethy AP, et al. , Rapid-learning system for cancer care. J Clin Oncol, 2010. 28(27): p. 4268–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shah A, et al. , Building a Rapid Learning Health Care System for Oncology: Why CancerLinQ Collects Identifiable Health Information to Achieve Its Vision. J Clin Oncol, 2016. 34(7): p. 756–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Adam T and Aliferis C, eds. Personalized and Precision Medicine Informatics: A Workflow-Based View. 2020, Springer: Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Norgeot B, et al. , Assessment of a Deep Learning Model Based on Electronic Health Record Data to Forecast Clinical Outcomes in Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis. JAMA Netw Open, 2019. 2(3): p. e190606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Abernethy A and Khozin S, Clinical Drug Trials May Be Coming to Your Doctor’s Office: Electronic medical records make possible a new research model based on real-world evidence., in Wall Street Journal. 2017, Dow Jones Publications: New York, New York. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhao J, et al. , Learning from Longitudinal Data in Electronic Health Record and Genetic Data to Improve Cardiovascular Event Prediction. Sci Rep, 2019. 9(1): p. 717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Piasecki J and Dranseika V, Research versus practice: The dilemmas of research ethics in the era of learning health-care systems. Bioethics, 2019. 33(5): p. 617–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thomas PS, et al. , Preventing undesirable behavior of intelligent machines. Science, 2019. 366(6468): p. 999–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lillie EO, et al. , The n-of-1 clinical trial: the ultimate strategy for individualizing medicine? Per Med, 2011. 8(2): p. 161–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nikfarjam A, et al. , Profiling off-label prescriptions in cancer treatment using social health networks. JAMIA Open, 2019. 2(3): p. 301–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rodon J, et al. , Challenges in initiating and conducting personalized cancer therapy trials: perspectives from WINTHER, a Worldwide Innovative Network (WIN) Consortium trial. Ann Oncol, 2015. 26(8): p. 1791–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yauney G and Shah P, Reinforcement Learning with Action-Derived Rewards for Chemotherapy and Clinical Trial Dosing Regimen Selection. Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, 2018. 85: p. 161–226. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Scuffham PA, et al. , Using N-of-1 trials to improve patient management and save costs. J Gen Intern Med, 2010. 25(9): p. 906–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Larson EB, Ellsworth AJ, and Oas J, Randomized clinical trials in single patients during a 2-year period. JAMA, 1993. 270(22): p. 2708–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schellekens H, et al. , Making individualized drugs a reality. Nat Biotechnol, 2017. 35(6): p. 507–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Arnold C, Who shrank the drug factory? Briefcase-sized labs could transform medicine. Nature, 2019. 575(7782): p. 274–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dewan MJ and Norcini JJ, We Must Graduate Physicians, Not Doctors. Acad Med, 2020. 95(3): p. 336–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Simon R and Roychowdhury S, Implementing personalized cancer genomics in clinical trials. Nat Rev Drug Discov, 2013. 12(5): p. 358–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lazar V, et al. , A simplified interventional mapping system (SIMS) for the selection of combinations of targeted treatments in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncotarget, 2015. 6(16): p. 14139–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Barabasi AL, Gulbahce N, and Loscalzo J, Network medicine: a network-based approach to human disease. Nat Rev Genet, 2011. 12(1): p. 56–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Koopman M, et al. , Sequential versus combination chemotherapy with capecitabine, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin in advanced colorectal cancer (CAIRO): a phase III randomised controlled trial. Lancet, 2007. 370(9582): p. 135–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Galloway TJ, et al. , A Phase I Study of CUDC-101, a Multitarget Inhibitor of HDACs, EGFR, and HER2, in Combination with Chemoradiation in Patients with Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res, 2015. 21(7): p. 1566–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Haussecker D and Kay MA, RNA interference. Drugging RNAi. Science, 2015. 347(6226): p. 1069–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jonas O, et al. , An implantable microdevice to perform high-throughput in vivo drug sensitivity testing in tumors. Sci Transl Med, 2015. 7(284): p. 284ra57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Stebbing J, et al. , Patient-derived xenografts for individualized care in advanced sarcoma. Cancer, 2014. 120(13): p. 2006–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Crystal AS, et al. , Patient-derived models of acquired resistance can identify effective drug combinations for cancer. Science, 2014. 346(6216): p. 1480–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Golchin A and Farahany TZ, Biological Products: Cellular Therapy and FDA Approved Products. Stem Cell Rev, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Schuck RN and Grillo JA, Pharmacogenomic Biomarkers: an FDA Perspective on Utilization in Biological Product Labeling. AAPS J, 2016. 18(3): p. 573–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Innominato PF, et al. , The circadian timing system in clinical oncology. Ann Med, 2014. 46(4): p. 191–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.