Abstract

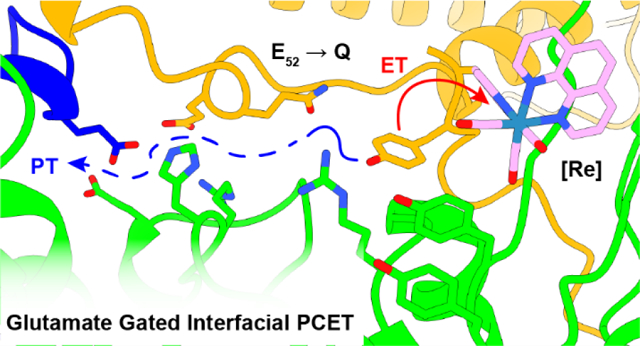

The class Ia ribonucleotide reductase of Escherichia coli requires strict regulation of long-range radical transfer between two subunits, α and β, through a series of redox-active amino acids (Y122•[β] ↔ W48?[β] ↔ Y356[β] ↔ Y731[α] ↔ Y730[α] ↔ C439[α]). Nowhere is this more precarious than at the subunit interface. Here we show that the oxidation of Y356 is regulated by proton release involving a specific residue, E52[β], which is proposed to order a polar channel at the subunit interface for rapid proton transfer to the bulk solvent. An E52Q variant is incapable of Y356 oxidation via the native radical transfer pathway or non-native photochemical oxidation, following photosensitization by covalent attachment of a photooxidant at position 355[β]. Substitution of Y356 for various FnY analogs in an E52Q‒photoβ2, where the sidechain remains deprotonated, recovered photochemical enzymatic turnover. Transient absorption and emission data support the conclusion that Y356 oxidation requires E52 as a proton acceptor, suggesting its essential role in gating radical transport across the protein-protein interface.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

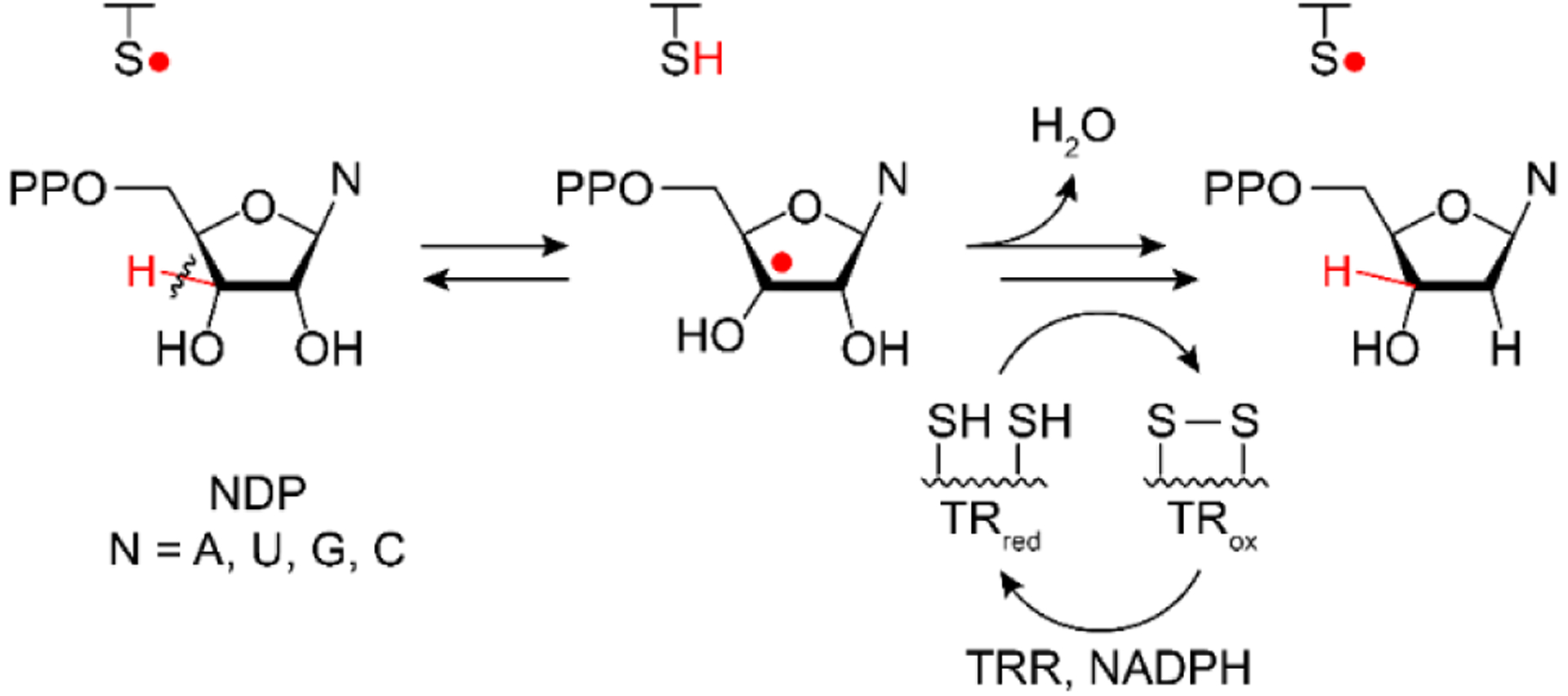

Class Ia ribonucleotide reductases (RNRs) require two subunits (α2 and β2) for the reduction of nucleoside diphosphates (NDPs) to deoxynucleoside diphosphates (dNDPs, Figure 1).1,2 E. coli Ia RNR utilizes an α2β2 complex for activity. Subunit α2 controls the allosteric regulation sites that govern specificity and activity for dNDP formation3 and is the site of the reduction reaction. Subunit β2 houses the essential diferric-tyrosyl radical (Y•) cofactor, which generates the thiyl radical in α that initiates substrate reduction (Figure 1). For the E. coli class Ia RNR, the distance between the stable metallo-cofactor in β2 and the substrate in α2 was proposed to be ~35 Å. This distance was based on a symmetric α2β2 docking model of Uhlin and Eklund using the structures of each subunit4 and pulsed electron-electron double resonance (PELDOR) studies5 using a mechanism based inhibitor of RNR and using site-specifically incorporated unnatural redox active tyrosine analogs (UAA).6 The PELDOR studies revealed an asymmetry within the α2β2 complex, originally suggested by studies of Ehrenberg.7 Efforts to obtain a structure of an “active complex” of any class I RNR remained elusive due to the weak and dynamic interactions of α2 and β2.

Figure 1.

Ribonucleotide reductase function. Nucleotides are “activated” for reduction by a cysteine based thiyl radical mediated H-atom abstraction from the 3′-C. The substrate radical is then reduced, losing water from the 2′-C, by two cysteines in the active site that form a disulfide bond. Re-reduction of disulfide by the thioredoxin (TR), thioredoxin reductase (TRR), and NADPH system regenerates the active site for subsequent turnover. Thiyl radical generation occurs through radical transfer and is the basis for class and sub-class differentiation. Adapted from reference 1.

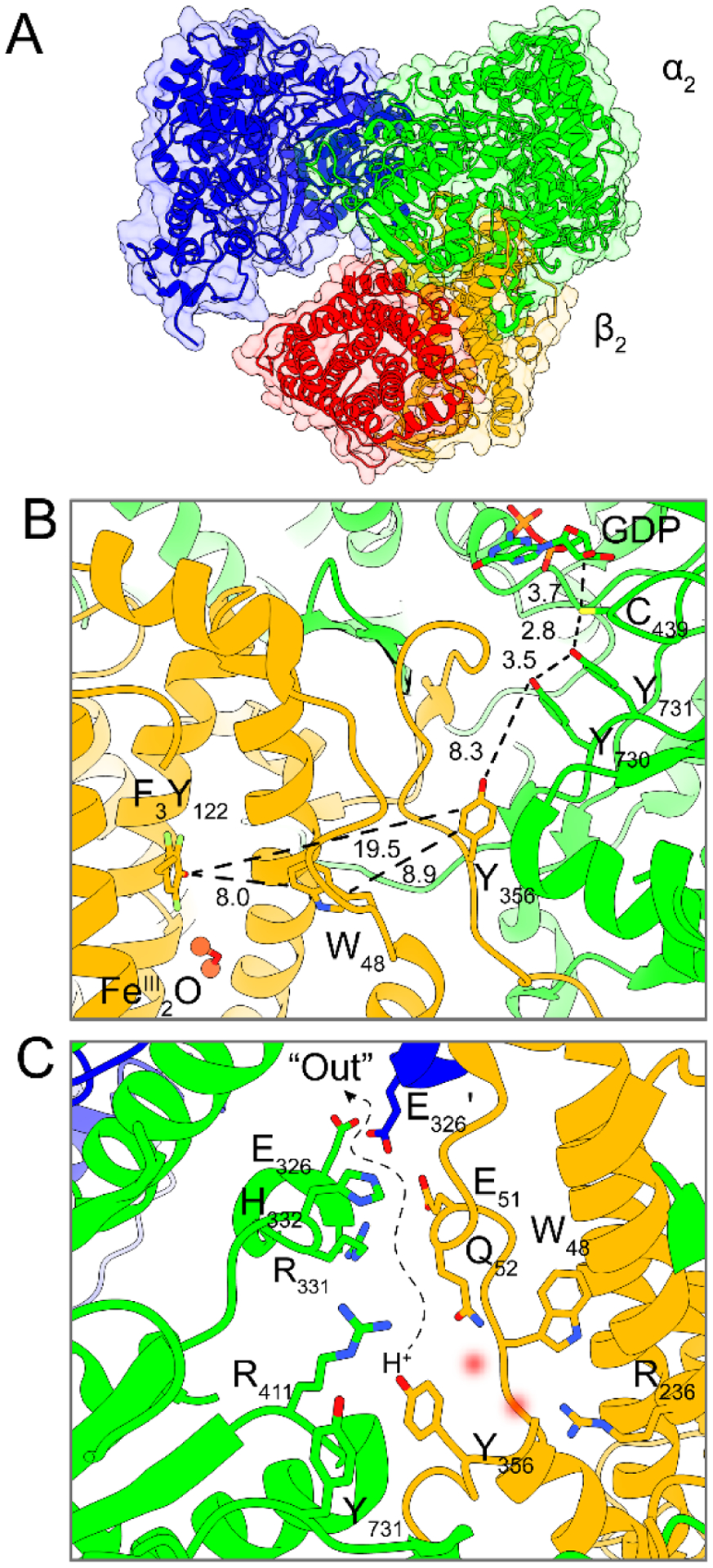

Very recently using a double mutant of β2 (E52Q/2,3,5-F3Y122•) incubated with substrate GDP, specificity effector TTP, and wt-α2, allowed for the trapping of an active asymmetric complex of α2β2, which was structurally characterized by cryo-EM (Figure 2A).8 In this complex the C-terminal tail (residues 341–375) of β was revealed for the first time in one of the two β2s; the second β tail remains disordered. This tail has been shown to be essential in α2β2 subunit interactions9,10 and also to contain several essential residues, including Y356 and E350 proposed to reside at the α/β subunit interface in the proposed 35 Å radical transfer (RT) pathway (Figure 2B). Over such an extended distance, RT proceeds through distinct radical “hopping” events along a pathway of amino acids (Y122•[β] ↔ W48?[β] ↔ Y356[β] ↔ Y731[α] ↔ Y730[α] ↔ C439[α]) in a reversible and conformationally gated manner.11

Figure 2.

Cryo-EM structure of an active, asymmetric RNR α2β2 complex (α2, blue and green; β2, orange and red). A Asymmetric structure of the overall complex showing an ordered α(green)/β(orange) pair and a partially disordered α′(blue)/β′(red) pair where the displaced α′/ β′ pair has already turned over, and the ordered α/β is poised for radical transfer. B Radical transfer pathway residues with distances in Å in the α/β pair. C Proposed pathway for H+ escape following Y356[β] (Y731[α]) oxidation involving several ionizable residues and potentially ordered waters (red blurred circles) from crystallographic structures.

The thermodynamics of tyrosine oxidation necessitate that proton release be coupled to the electron transfer step at physiological pH, i.e., that radical transport occurs by proton-coupled electron transfer (PCET).12,13 In α2, the transport of the radical occurs via a colinear PCET mechanism, wherein both the proton and electron transfer between the same residues of the pathway.14–16 Conversely in β2, the distance between Y122 and the interfacial Y356, suggest orthogonal PCET where the electron transfers through the protein and couples to proton transfer (PT) between nearby water molecule(s) or ionizable residues within H-bonding distance.8,17,18 Spectroscopic investigations of the radical environment at Y356• and pH dependent FnY122•/Y356• (FnYs, fluorinated tyrosines) equilibria have led us to propose that a proton must enter and exit the interface during redox cycling of this residue.18,19 However, on the basis of the original docking model,4 in which the Y356[β] residue is buried within the protein interface, it was not obvious how a proton inventory could be maintained for orthogonal PCET. The asymmetry of the α2β2 interaction unveiled by the cryo-EM structure reveals a path for Y356 to release a proton that escapes the interface through a polar solvated cavity following oxidation (Figure 2C).8 The subunit interface presents a perilous moment during the catalytic cycle of RNR, and an uncontrolled environment here could result in radical reduction by any number of cellular reductants leading to lethal consequences. For this reason, the fidelity of RT across the subunit interface is indeed highly controlled, but the mechanism by which PT and solvation is regulated during PCET at the interface has heretofore remained poorly understood.

Mutation of a surface exposed residue at the subunit interface (E52Q) in β2 strongly inhibits RNR activity (<10−3 the wt rate, lower limit of detection), while decreasing α/β subunit affinity by only 50% (0.18 to 0.12 μM).10,20 Strikingly, substitution of Y122[β] for 2,3,5‒ F3Y122 in the presence of E52Q, strongly increased subunit affinity (Kd < 0.4 nM lower limit of detection) and allowed partial dNDP activity recovery in a single turnover assay (1dGDP/α2). The rate constants, however, for RT and the substrate turnover process remained conformationally gated and slow,20,21 obfuscating the function of E52. Several potential roles for E52 have been proposed, either conferring allosteric information from α to the Y122• site in β and/or in modulating proton release/rebinding during PCET.

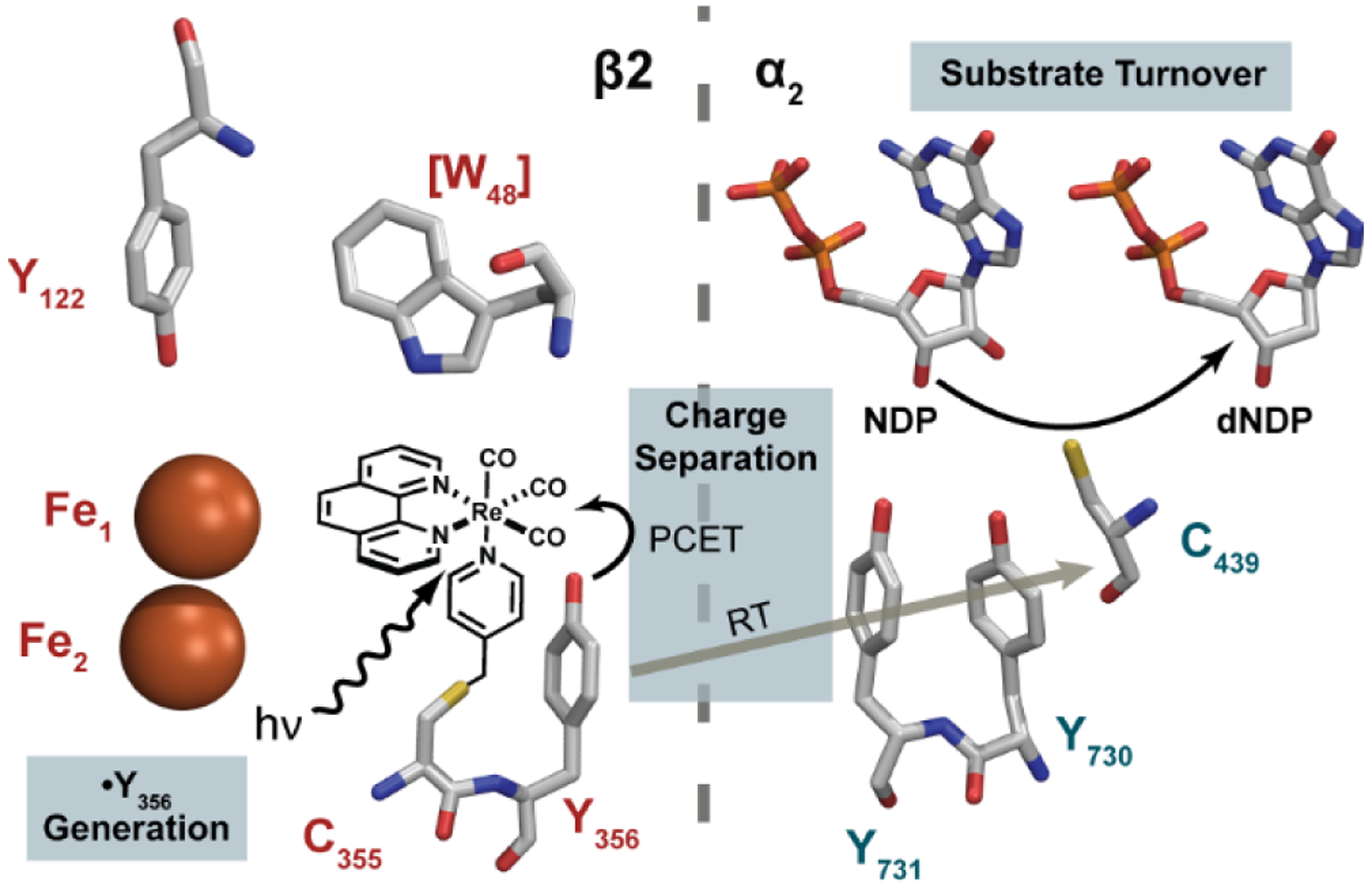

We have developed an approach to trigger radical transport with a photoβ222 that can rescue mutant RNRs inhibited in RT and catalytic activity,23 and that allow examination of PCET dynamics at the subunit interface.16,24,25 The photoβ2 methodology uses a covalently attached photooxidant (tricarbonyl(1,10-phenanthroline)-4-thiomethylpyridine, [Re]) ligated to S355C, directly adjacent to the RT pathway residue Y356. Excitation of the photooxidant produces the [ReI]* excited state, which can directly abstract an electron from Y356 to generate [Re0] and Y356•. This charge transfer process thus reports directly on radical generation, and can be interrogated by [ReI]* emission lifetimes (τ) in the presence of various Y356X substitutions (X = F, FnY) where F serves as the control (τo) that does not participate in charge transfer and FnY are fluorotyrosines. The generation of the [Re0]/Y356• by PCET and the subsequent radical transfer pathway are shown in in Figures 3 and S1(top). The [Re0]/Y356• charge separated state is prone to recombination to reform the closed shell Y356 and [ReI] ground state. However, this recombination reaction may be avoided by oxidatively quenching the [ReI]* excited state with RuIII(NH3)6Cl3 to form [ReII], which in turn oxidizes Y356 to form the more stable [ReI]/Y356•. Following this sequence of events, the Y356• is free to propagate along the RT pathway. Radical transport may be followed by monitoring the Y• absorbance at 410 nm, thus reporting on the kinetics of RT within the pathway. Given the unique insight afforded by the photoβ2 method into the PCET kinetics of RT, with time resolution superseding overall conformational gating steps that obscure PCET in RNR, we employ the methodology to probe the consequences of the asymmetric RNR complex on RT at the α/β interface. The results show that Y356 oxidation requires H+ release that is regulated by E52 and inhibited by the E52Q mutation, providing a rationale for the inactivity of this mutant β2 and a gating mechanism for H+ exchange with solvent thus enabling PCET across the interface of the α2β2 RNR complex.

Figure 3.

Excited-state reaction pathways after excitation of [ReI]* in photoβ2.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Luria Broth, ampicillin trisodium salt, L-arabinose, chloramphenicol, phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), MgSO4, adenosine triphosphate (ATP), deoxycytidine, and cytidine diphosphate (CDP) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was purchased from GoldBio. DEAE and Q-Sepharose resins were obtained from GE Healthcare Life Sciences. Ni-NTA Sepharose resin was purchased from Qiagen. The primers for site-directed mutagenesis was obtained from Integrative DNA Technologies (IDT). BL21(DE3) E. coli competent cells were obtained from New England Biolabs (NEB). Tricarbonyl(1,10-phenanthroline)-(4-bromomethylpyridine)rhenium(I) hexafluorophosphate ([Re]-Br) was available from a previous study.22 [5-3H] CDP was purchased from ViTrax. Alkaline phosphatase (AP, calf intestine) was purchased from Roche. Thioredoxin (TR) and thioredoxin reductase (TRR) were available from a prior study.20

Site directed mutagenesis.

Site directed mutagenesis was used to modify the existing pBAD photoβ2 plasmid (photoβ2 = C268S/C305S/S355C–β2) or Y356F-photoβ2 or Y356Z-photoβ2 to incorporate the additional E52Q mutation. The forward and reverse primers used were:

5´-GGAGACGTCAACCTGTTCCGGACGCC-3´

5´-GGCGTCCGGAACAGGTTGACGTCTCC-3´

and successful incorporation of the point mutation was confirmed via Sanger sequencing performed by Quintara Biosciences.

Enzymatic fluorotyrosine synthesis.

2,3,5-Trifluorotyrosine (2,3,5-F3Y) and 3,5-diflurotyrosine (3,5-F2Y) were synthesized enzymatically from 2,3,6-trifluorophenol or 2,6-difluorophenol via tyrosine phenol lyase (TPL) as previously described.26

Protein expression and purification.

The canonical amino acid photoβ2 variants were expressed, purified, and labeled with the photosensitizer as previously reported.22

The expression and purification of E52Q/FnY356-photoβ2 was accomplished using the E. coli BL21(DE3) expression platform transformed with both a pBAD vector encoding the E52Q/FnY356-photoβ2 gene, and pEVOL-aaRS-FnY for tRNA/tRNA synthetase expression. Successful co-transformants were selected for on LB agar plates containing 100 mg/L ampicillin and 33 mg/L chloramphenicol. A single colony was inoculated into 100 mL LB medium and grown at 37 °C for 8–10 h. The starter culture was diluted into 4 × 2 L LB medium with 100 mg/L ampicillin and 33 mg/L chloramphenicol, and left to grow at 37 °C until the O.D. at 600 nm reached 0.5. pEVOL-aaRS-FnY was then induced with 0.2% L-arabinose and the culture was supplemented with 0.7 mM FnY. The expression of β2 was induced by adding 0.4 mM IPTG when the O.D. attained 0.6. The cells were harvested after 5 h of over-expression, frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. The growth yield was 2.5–3.0 g wet cell weight per liter media.

All protein purification steps were performed at 4 °C unless otherwise stated. The cell pellet (20 g) was thawed and re-suspended in lysis buffer (5 mL per gram of wet cell paste) containing 50 mM Tris pH 7.6, 5% glycerol, and 0.5 mM PMSF and homogenized by French Press at 13,000 psi. The lysate was supplemented with ferrous ammonium sulfate (1 mg/mL of cell lysate) and sodium ascorbate (1 mg/mL of cell lysate) dissolved in 50 mM Tris pH 7.6 and stirred for 30 min on ice prior to removing the cell debris by centrifugation at 25,000 g for 10 min. The supernatant was collected and streptomycin sulfate was added dropwise from a concentrated solution to a final concentration of 1% (w/v) and allowed to equilibrate for 30 min on ice to precipitate DNA, followed by centrifugation at 25,000 g for 10 min. The protein in the supernatant was precipitated with (NH4)2SO4 (39 g per 100 mL of cell lysate) while stirring for 30 min on ice. The protein pellet was collected by centrifugation at 25,000 g for 15 min and re-dissolved in a minimal volume of lysis buffer and desalted by Sephadex G-25 column (100 mL), which was pre-equilibrated with the lysis buffer. The protein fractions were collected and loaded onto a DEAE anion exchange column (80 mL) pre-equilibrated with 50 mM Tris pH 7.6, 5% glycerol, NaCl 100 mM 0.5 mM PMSF pH 7.6, which will be referred to as buffer A hereafter, washed with 10 column volumes of buffer A and eluted with a 300 mL × 300 mL linear gradient of NaCl (100–500 mM). The fractions with absorption at 410 nm were collected and diluted three-fold with lysis buffer and loaded onto Q-Sepharose anion exchange (50 mL) column pre-equilibrated in buffer A, washed with 10 column volumes of buffer A and eluted with a 200 mL × 200 mL linear gradient of NaCl (150–500 mM) in buffer A.

Labeling E52Q/FnY356-photoβ2 with photooxidant.

Labeling was performed as previously described with minor modifications.22 Briefly, E52Q/FnY356-photoβ2 was treated 10 mM DTT and 20 mM hydroxyurea for 30 min to reduce any potential disulfide bonds as well as the endogenous Y122•, and then separated from the reductants over a G-25 column. The labeling of the β2 with the [Re] photooxidant was performed in 50 mM HEPES and 5% glycerol, pH 7.6. Five equivalents of [Re-Br] (50 mM in DMF) was slowly added to the protein solution with stirring. The solution was incubated at 4 °C with gentle shaking for 2 h. The protein solution was centrifuged at 25,000 rpm for 10 min to remove any precipitant and purified with G-25 column. The [Re]-labeled photoβ2 was used for all photochemical experiments.

Kd determination.

Kd measurements were performed by the competitive inhibition assay previously developed.10 In this assay, reaction mixtures contained 0.15 μM wt α2, 0.3 μM wt β2 (reconstitution yield of 1.1 Y• /β2), 1 mM CDP, 3 mM ATP, 100 μM TR, 1 μM TRR, 0.2 mM NADPH and 0–10 μM E52Q-photoβ2 in standard assay buffer (50 mM HEPES, 1 mM EDTA, 15 mM MgSO4, 5% glycerol adjusted to pH 7.6 by 6 M NaOH). The reaction was monitored continuously at 340 nm for consumption of NADPH over 1 min. The data were fit to:

| (1) |

where E52Q is shorthand notation for E52Q-photoβ2, [E52Q] bound is the concentration of the E52Q-photoβ2: α2 complex, [E52Q]max is the concentration of the E52Q-photoβ2:α complex at maximal [E52Q]free, and Kd is the dissociation constant for E52Q-photoβ2 with α2. This analysis assumes that the α2β2 complex concentration at different concentrations of E52Q-photoβ2 inhibitor scales with activity.

Single-turnover photochemical assay.

Photochemical turnover assays were carried out as previously described27 with minor modification using 10 μM α2, 20 μM E52Q-photoβ2 variants, 1 mM [3H]-CDP (31,506 cpm/nmol), 3 mM ATP, and 10 mM Ru(NH3)6Cl3 in 50 mM HEPES, 15 mM MgSO4, 1 mM EDTA, and 5% glycerol at pH 7.6 (assay buffer). The total volume was 60 μL. The assay mixture was illuminated using a 150 W Xe arc lamp with a 320 nm long pass filter for 10 min at 25 °C. The reaction was quenched by adding 60 μL of 2% ice-cold HClO4. Any precipitate was removed by centrifugation at 25,000 rpm for 5 min. The supernatant was neutralized with 0.4 M KOH, followed by centrifugation at 25,000 rpm for 5 min. 60 μL of the supernatant was supplemented with 12 nmol of deoxycytidine as a carrier and treated with 7 units of AP at 37 °C for 2 h. The [3H]-dCDP was purified from unreacted CDP by the method of Steeper and Steward, and quantified by scintillation counting.28 The reported error represents one standard deviation of triplicate measurements.

[Re]* Emission kinetics.

Time resolved emission and absorption measurements were performed on a home-built nanosecond time resolved instrument described previously and schematically represented in Figure S2.22 Emission lifetime measurements were performed on samples prepared identically as those prepared for steady state emission measurements, and the entire volume (550 μL) was recirculated by a peristaltic pump through a 2 mm × 10 mm cylindrically bored quartz cuvette. Sample excitation was achieved by the frequency tripled output of an Nd:YAG laser (355 nm, 1‒1.5 mJ/pulse) and the emission was collected via a series of lenses, slits and a monochromator directed to a photomultiplier tube. Spectral resolution was determined by spectrophotometer entrance and exit slits at 0.25 nm and collected at 575 nm, with a long pass filter (λ > 375 nm) to reject pump scattering. Data were recorded over 100 shots and measurements were performed in triplicate.

Charge separation rate constant, kCS is determined from:

| (2) |

Here τobs is the observed lifetime for the α2β2 pair of interest, whereas τ0 is the reference lifetime in the absence of Y356[β] (Y356F) and Y731[α] (Y731F). The photophysical schemes that describe τ0, τobs and kCS are presented in Figure S1.

Transient absorption spectroscopy.

Transient absorption spectra were measured essentially as previously described23 with 50 μM α2, 20 μM E52Q-photoβ2 variants, 1 mM CDP, 3 mM ATP, and 10 mM Ru(NH3)6Cl3 in assay buffer. The solution was circulated with a peristaltic pump equipped with an in-line 0.22 μM syringe filter. The spectra were collected on a CCD camera from 1 μs after excitation. The pump and probe exposures were controlled by series of shutters and delay generators and the spectra were calculated by −log[(pump on:probe on)/(pump off:probe off) − (pump off:probe on)/(pump off:probe off)]. The data for each individual sample were collected and averaged over 100 laser shots and inspected for consistency, and 10 such collections per sample were averaged to produce a single TA trace. Spectra reported represent the average of three such experiments on the same photoβ2: α2 complex.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

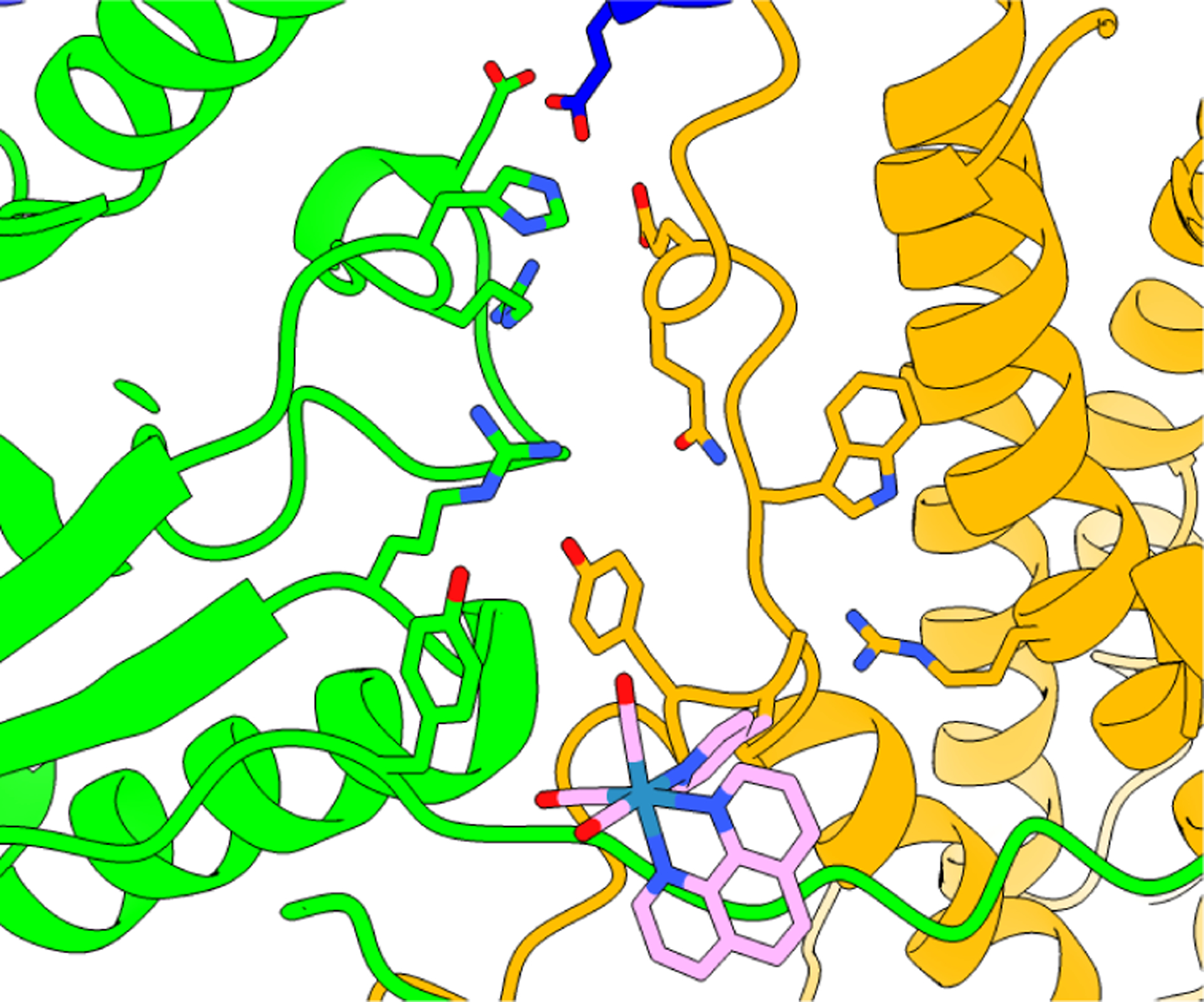

The E52Q-photoβ2 was generated by site-directed mutagenesis of the corresponding photoβ2, followed by reduction of the endogenous Y122• and covalent ligation with [Re] at S355C, directly adjacent to Y356 as previously described.22 Figures 4 and S3 show the [Re] complex modelled in the cryo-EM structure; the [Re] complex resides within a pocket at the interface and is situated on the opposite side of Y356 relative to the E52-flanked channel for H+ release. Binding studies reveal that the [Re] modification does perturb subunit interactions mildly (Kd of 1.06 (7) μM, Figure S4), consistent with all other [Re] labeled photoβ2 variants.16,22–24,29 The Kd for the wt subunit interactions is 0.2 μM. The perturbation in Kd is not surprising given the size and location of the [Re] group on the photoβ2. Notwithstanding, the [Re] modification does not significantly perturb activity of the enzyme (vide infra). The asymmetry of the “active-trapped” structure (Figure 2A) and the partially disordered α′/ β′ interaction including the disordered β′-tail (residues 341 to 375) and partially disordered N-terminal cone domain of α′ (Figure 2A, blue/red subunits) may explain why the [Re]-complex recapitulates many of the defining features of radical transfer at the subunit interface identified by orthogonal methods. For example, the conformational dynamics of Y731 in α2, observed initially by PELDOR spectroscopy in wt and R411A α2 with the 3-aminotyrosine radical trap in place of Y731,30 have also been clearly resolved by the photoβ2 emission kinetic and flash-quenched transient absorption experiments.16 Based on this study and others focused on the role of E350-β at the subunit interface23 and the use of FnY356s-β to understand the role of proton transfer in its oxidation29 as well as the distal location of [Re] to E52(Q), we believe that the E52Q-photoβ2 reports on the interactions between Y356 and E52 with fidelity.

Figure 4.

Docking model for the [Re] photooxidant within the α2:β2 interface based on the crystal structure of the [Re] complex and the cyro-EM structure of the active α2β2 E. coli RNR.8 Docking and structural refinement were performed by moving the [Re] unit so as to minimize steric contact of the chromophore and protein sidechains as much as possible, yet steric clashes do exist. This docking model is not intended to be an authentic representation of the actual structure of the complex, but it does provide a general perspective on the location of the S355C labeling site relative to the E52(Q) residue. The [Re] chromophore resides on the opposite side of Y356 relative to the proposed polar channel of H+ release.

Using this photoβ2 construct, three types of experiments have been used to assess the role of E52 in the radical transfer process: (1) activity assays with E52Q/3,5-F2Y356-photoβ2 and E52Q/Y356-photoβ2 (2) emission quenching decay kinetics [ReI]* (Figure S1) and (3) transient absorption spectroscopic experiments with E52Q/FnY356-photoβ2 (n = 2,3) to detect the FnY356• generation and radical transport (Figure 3).

Activity.

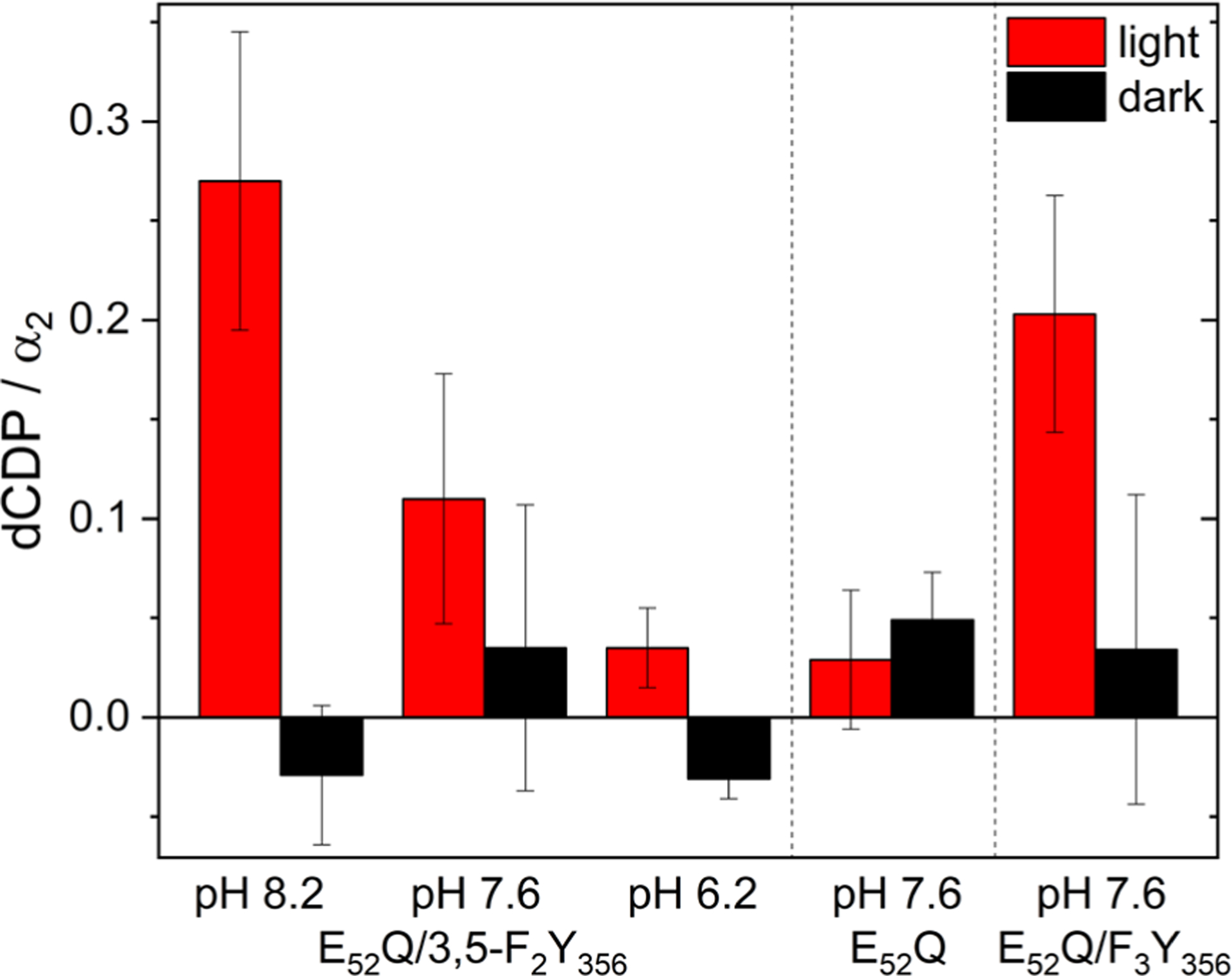

The flash quench technique with Ru(NH3)6Cl3 was used to examine dCDP formation with E52Q-photoβ2 and E52Q/Y356F2Y-photoβ2 (Figure 5). With Y356, no statistically significant dCDP production is observed after 10 min of illumination with respect to non-illuminated control. Thus, as with the wt-β2 (that has a Y122•), E52 is essential for catalysis with photo-β2 where Y122 is bypassed. This inactivity suggests that either no radical is formed at Y356 photochemically, or that the photogenerated radical is not competent for RT and/or nucleotide reduction. This behavior is distinct on mutants (E350D, E350N) from analogously conserved interfacial residue, E350(β), for which E350Q or E350D mutations are also completely inactive with α2/β2/substrate and effector. These same mutations in the photoβ2 construct, however, showed substantial photochemical recovery of activity.23,31

Figure 5.

Single turnover photochemical assays of the E52Q-photoβ2:α2 and E52Q/Y356F2Y-photoβ2:α2 complex with 10 μM α2, 10 μM photoβ2, 0.2 mM [3H]-CDP substrate, 3 mM ATP effector, and 10 mM Ru(NH3)6Cl3 in assay buffer with (red) and without (black) 10 min exposure to light (λ > 320 nm). Error bars represent one standard deviation among triplicate measurements.

Our previous pH-dependent activity studies using FnY356 analogs,32,33 synthesized by native protein ligation methods, and wt-β231 have shown that dNDP activity is maintained when F2Y is in the protonated or deprotonated state. Thus radical transfer can occur across the subunit interface by a PCET mechanism below the pKa of the FnY and by ET above its pKa. We thus prepared F2Y356-photo-β2, which our previous studies have shown has a pKa of 7.0,29 and examined its activity as well. The results of Figure 5 reveal that E52Q-photo-β2 under light irradiation can make dCDP when the tyrosine is deprotonated and thus can support ET-mediated radical transfer.

Emission Quenching.

To determine whether Y356 can be photochemically oxidized by the [Re] photooxidant in the presence of the E52Q mutation, we performed [ReI]* emission quenching experiments on the E52Q‒photoβ2 in complex with either wt or Y731F α2. Table 1 lists the emission quenching results for the E52Q‒photoβ2 systems and their respective controls (Figure S5 shows representative decay traces from which kinetics were extracted). The quenching of [ReI]* by Y356 oxidation leads to the formation of a transient [Re0]-Y356•, occurring with a rate constant kCS = 3.3 × 105 s−1 (Entry 2), reflecting efficient charge separation. Oxidation of Y356 in E52Q-photoβ2 is significantly retarded as reflected by a kCS = ~0.5 × 105 s−1 (Entries 3 and 4) using the control E52Q/Y356F-photoβ2 to determine τo (Entry 5), where Y356 has been replaced with the redox inert F. Furthermore, the quenching of [ReI]* cannot bypass Y356 as evidenced by the similarity of quenching lifetimes for E52Q/Y356F-photoβ2 paired with Y731-α2 and wt-α2 (Entries 5 and 6, respectively). To provide further insight into the direct photooxidation of Y356 in an E52Q-photoβ2: α2 complex, we employed flash-quench transient absorption spectroscopy, which is sensitive to the long-lived [ReI]‒Y356• state resulting from oxidative quenching of [ReI]*. No additional absorption is observed in the characteristic Y• absorption region relative to the control E52Q/Y356F-photoβ2 (Figure S6). These data show Y356 oxidation to be inhibited by the E52Q mutation.

Table 1.

Emission lifetime data (τobs) for various photoβ2:α2 combinations and calculated kCS rates of FnY356 oxidation relative to Y356 of E52Q-photoβ2 in complex with either wt or Y731F-α2.

| Entry | photoβ2 | α2 | pH | τobs (ns)a | kCS (105 s–1)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Y356F | Y731F | 7.6 | 730 (10)b, c | k0 |

| 2 | Y356 | Y731F | 7.6 | 590 (20)c | 3.3 (1) |

| 3 | E52Q | Y731F | 7.6 | 617(5) | 0.6(3) |

| 4 | E52Q | wt | 7.6 | 622(2) | 0.5(3) |

| 5 | E52Q/Y356F | Y731F | 7.6 | 642(6) | k0 |

| 6 | E52Q/Y356F | wt | 7.6 | 632(8) | n.a.d |

| 7 | E52Q/ 3,5-F2Y356 | Y731F | 8.2 | 590(1) | 1.4(2) |

| 8 | E52Q/ 3,5-F2Y356 | wt | 8.2 | 553(2) | 2.5(3) |

| 9 | E52Q/ 3,5-F2Y356 | Y731F | 7.6 | 596(4) | 1.2(4) |

| 10 | E52Q/ 3,5-F2Y356 | wt | 7.6 | 572(5) | 1.9(4) |

| 11 | E52Q/2,3,5-F3Y356 | Y731F | 7.6 | 602(1) | 1.0(2) |

| 12 | E52Q/2,3,5-F3Y356 | wt | 7.6 | 543(3) | 2.8(3) |

We have previously leveraged fluorinated tyrosine analogs (FnYs, n = 1–3) as mechanistic probes that depress the fluorophenolic pKa sufficiently such that FnY oxidation occurs through ET rather than PCET at pHs above the fluorophenolic pKa.29,33 Generation of a 3,5‒F2Y356 and 2,3,5‒F3Y356 substituted E52Q-photoβ2 (E52Q/Y356F2Y-photoβ2 and E52Q/Y356F3Y-photoβ2, respectively) was accomplished by amber codon suppression and these variants were used to interrogate whether radical generation could be enhanced by decoupling it from proton transfer.24,34 Whereas 3,5‒F2Y356 (pKa = 7.0) is partially deprotonated at pH 7.6, it is fully deprotonated at pH = 8.2; the more acidic F3Y356 (pKa = 6.2) is fully deprotonated at pH = 7.6.29 For E52Q/3,5-F2Y356-photoβ2, the emission quenching rates (Entries 7–10) are enhanced with regard to the E52Q/Y356-photoβ2 control (Entry 5). Moreover, the quenching rate of E52Q/3,5-F2Y356-photoβ2 increases with 3,5-F2Y356 deprotonation (Entries 7 vs 9 and Entries 8 vs 10). At pH 8.2, where the 3,5‒F2Y356 is completely deprotonated, the kCS = 2.5 × 105 s–1 (Entry 8) is nearly equivalent to that of E52Q/2,3,5-F3Y356-photoβ2 (Entry 12) at pH = 7.6. Hence, the charge separation kinetics of mutants where the proton is absent approaches that of the photoβ2 where E52 is not mutated (Entry 2, kCS = 3.3 (1) × 105 s–1), consistent with proton decoupling and effective radical generation and injection within the E52Q background. Finally, we note that in comparing the [ReI]* emission kinetics of E52Q/Y356FnY-photoβ2s in complex with wt α2 containing an intact radical transport pathway, the rate enhancement is more pronounced (Entries 8 vs 7, 10 vs 8 and 12 vs 11), suggesting that radicals are injected into the RT pathway in α on a timescale competitive with [ReI]* decay (i.e. RT is competitive with PCET quenching of [ReI]* shown in Figure 3).

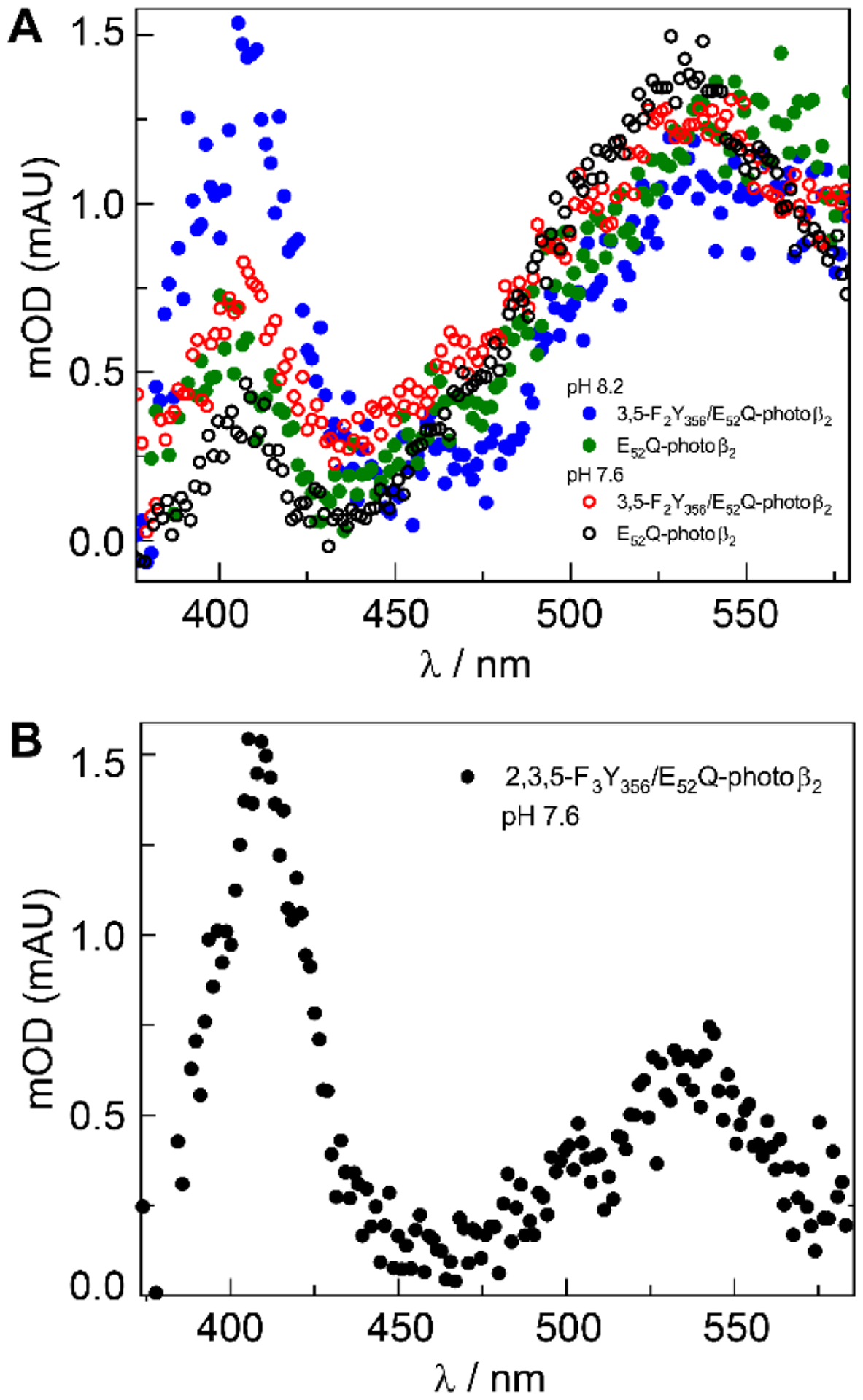

Transient Absorption.

Radical generation can be directly observed by transient absorption (TA) spectroscopy following flash quenching. Figure 6 compares the TA spectrum obtained for the single mutant E52Q-photoβ2:Y731F-α2 construct (Figure 6A, open black circles, pH 7.6 and green dots, pH 8.2) and double mutants E52Q/Y356F2Y-photoβ2 (Figure 6A, open red circles, pH 7.6 and blue dots, pH 8.2) and E52Q/Y356F3Y-photoβ2 (Figure 6B, black dots). As we have previously observed, when Y356 cannot be oxidized, the hole equivalent is diverted to tryptophan residues, akin to pathway arguments made for ET proteins,35,36 and the broad feature at 525 to 550 nm associated with a deprotonated tryptophan radical is observed. This is the case for E52Q-photoβ2 where Y356 is protonated and the E52Q mutation appears to inhibit release of the phenolic proton. The tyrosine residue cannot be oxidized and a W• signal prevails relative to only a minor signal appearing for Y•. We note that this off-pathway oxidation is likely responsible for a significant fraction of lost activity in photochemical turnover experiments.37 For E52Q/Y356F2Y-photoβ2 at pH 7.6, a modest increase in FnY• absorbance is observed with a concomitant decrease in W• congruent with a partially deprotonated F2Y356. However, when the tyrosine exists entirely as phenolate, which is the case for E52Q/Y356F2Y-photoβ2 at pH 8.2 and E52Q/Y356F3Y-photoβ2 (pKa 6.2) at pH 7.6, a pronounced Y• signal is observed upon photoexcitation (Figure 6A, blue dots and Figure 6B, black dots), constituting a >3‒fold increase in Y• with the correlated loss in the relative W• intensity. We interpret these results to suggest that the putative water channel is blocked by E52Q, thus interfering with interfacial PCET. The corresponding activity data for the 3,5-F2Y356 mutant shown in Figure 5 is consistent with these PCET kinetics results; E52Q-photoβ2 is able to turnover only when tyrosinate is present. The collective observations support a model where E52 participates in the obligate proton release from Y356 during oxidation, regulating radical transfer by PCET.

Figure 6.

TA spectra of A E52Q‒photoβ2:Y731F‒α2 (○, pH 7.6; ● pH 8.2) and E52Q/Y356F2Y‒photoβ2:Y731F‒α2 complex (○, pH 7.6; ● pH 8.2) and B E52Q/Y356F3Y‒photoβ2:Y731F‒α2 complex at pH = 7.6. All spectra were collected at 2 μs delay from the excitation pulse. The peak at λmax ~ 540 nm is that of W• and λmax ~ 410 nm is that of Y•.

Role of E52.

A model for the role of E52-β is now possible based on the cryo-EM structure (Figure 2C) highlighting the subunit interface in the ordered α/β pair (green/orange Figure 2A). The α2β2 subunit interaction increases in affinity when radicals are trapped in the pathway. The Kd in the cryo-EM radical-trapped structure is <0.4 nM20 vs 0.2 μM for wt.10 The Y356• generated in this environment reveals that E52 is >7 Å removed from its phenolic oxygen and >8 Å removed from Y731-α, the next residue in the pathway to be oxidized. Figure 2C also reveals that charged residues line an empty cavity, as the resolution of the structure is insufficient for water detection. The E326-α(green) and E326-α′(blue) residues in Figure 2C provide direct access to the bulk solvent at the α/α′ interface. This model is consistent with the data reported herein using photoβ2 as well as additional perturbative experiments that show Y731 to be flexible and Y356 to participate in hydrogen-bonding. PELDOR experiments30 and photoβ2 experiments16 show Y731 movement with rate constants much faster than RNR turnover. In addition, 94 GHz 1H-ENDOR experiments with a trapped Y356• using a 2,3,5-F3Y122•-β2, revealed two equivalent H bonds to its oxygen assigned to waters and high-field 263 GHz EPR experiments revealed the largest perturbation of the gx component of the g-tensor of a tyrosyl radical reported to date. Computational modelling, as well,38 suggests that E52 can move relative to Y356 to form a H-bonding pathway, which allows access of Y356 through a water channel.

Based on the results shown here, we propose that the E52Q mutation perturbs the H+ release from Y356, following oxidation, indirectly through a water network, and ultimately to the bulk solvent. In all photoβ2s, the [Re] unit does perturb the subunit interface to some extent, as evidenced by the elevated Kd, but the fidelity of PCET with respect to wt RNR is preserved. Although alternative mechanisms of H+ release through water channels that do not involve E52 may exist in the absence of the [Re] unit, the water channel involving E52 is critical as its mutation yields inactive enzyme in both photoβ2 and wt-β2. We also note that photoβ2 without the E52Q mutation exhibits a similar kCS rate constant when the proton is decoupled from the RT pathway (i.e., kCS = 2.8(3) × 105 s−1 for E52Q/2,3,5-F3Y356 (Entry 12 in Table 1) as compared to kCS = 3.3 × 105 s−1 for photoβ2 (Entry 2 in Table 1). Though the conservative E52Q mutation may potentially perturb water channels, its distal position relative to the RT pathway suggests otherwise. Cryo-EM structures using alternative trapping methods are in progress in an effort to reveal waters and the structure of E52 itself relative to Y356.

CONCLUSION

Direct kinetics measurements reveal that E52 plays a critical role in managing the PCET of radical transport across the α:β interface of RNR. As opposed to the symmetric and buried interface predicted by the traditional docking model of the α2β2 complex, a recent cryo-EM structure of an active RNR α2β2 complex reveals an asymmetric interface in which E52 is a constituent of a critical pathway for H+ to connect to a water network, and ultimately to the bulk solvent. The insight provided by this structure-function correlation rationalizes previously quizzical observations of interfacial residues possessing pKas consistent with that observed in aqueous solution and efficient PCET across the α:β interface. As we show herein, when E52 is mutated so as not to accommodate proton transfer, RT across the α:β interface of RNR is shut down. Perturbation of proton transfer within water clusters/channels via single amino acid sites is not unique to RNR. Cytochrome c oxidase (CcO) performs redox-coupled proton pumping to generate the proton motive force necessary for ATP synthesis.39 During proton pumping in the D‒channel, E242 (bovine heart CcO) serves to gate PT through a channel of conserved waters in a redox coupled manner.40,41 We suggest a similar mechanism is functional in the class Ia RNR of E. coli to protect the RT interface, while allowing for facile PT to the external solvent environment. Owing to the central role of RNRs in nucleic acid metabolism, therapeutics that inhibit distinct steps in the radical transport and chemistry of RNR lead to cytotoxicity, resulting in effective treatments of cancer.1,42–44 The studies reported herein show the fidelity of PCET in controlling RT across the α:β asymmetric interface and reveal an access point to disrupt RT, thus offering a potential new target for future drug design.

Supplementary Material

Funding Sources

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation under grant CHE-1855531. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grants GM047274 (D.G.N.), GM029595 (J.S.), and R35 GM126982 (C.L.D). C.L.D is an HHMI Investigator and a fellow of the Bio-inspired Solar Energy Program, Canadian Institute for Advanced Research. G.K. is supported by a David H. Koch Graduate Fellowship.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

PCET quenching and Radical transport model, photophysical schemes describing rate constants, schematic of laser set-up, [Re] docking model, Kd measurement of E52Q‒photoβ2, emission kinetic traces and fits, E52Q‒photoβ2 vs. E52Q/Y356F‒photoβ2 transient absorption spectra. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org/

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- (1).Greene BL; Kang G; Cui C; Bennati M; Nocera DG; Drennan CL; Stubbe J Ribonucleotide Reductases: Structure, Chemistry, and Metabolism Suggest New Therapeutic Targets. Annu. Rev. Biochem 2020, 89, 45–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Jordan A; Reichard P Ribonucleotide Reductases. Annu. Rev. Biochem 1998, 67, 71–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Hofer A; Crona M; Logan DT; Sjöberg BM DNA Building Blocks: Keeping Control of Manufacture. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol 2012, 47, 50–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Uhlin U; Eklund H Structure of Ribonucleotide Reductase Protein R1. Nature 1994, 370, 533–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Bennati M; Robblee JH; Mugnaini V; Stubbe J; Freed JH; Borbat P EPR Distance Measurements Support a Model for Long-Range Radical Initiation in E. coli Ribonucleotide Reductase. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2005, 127, 15014–15015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Seyedsayamdost MR; Chan CTY; Mugnaini V; Stubbe J; Bennati M PELDOR Spectroscopy with DOPA-β2 and NH2Y-α2s: Distance Measurements between Residues Involved in the Radical Propagation Pathway of E. coli Ribonucleotide Reductase. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2007, 129, 15748–15749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Roy B; Decout J-L; Béguin C; Fontecave M; Allard P; Kuprin S; Ehrenberg A NMR-Studies of Binding of 5-FdUDP and dCDP to Ribonucleotide-Diphosphate Reductase from Escherichia coli. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1995, 1247, 284–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Kang G; Taguchi AT; Stubbe J; Drennan CL Structure of a Trapped Radical Transfer Pathway within a Ribonucleotide Reductase Holocomplex. Science 2020, 368, 424–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Climent I; Sjöberg BM; Huang CY Site-Directed Mutagenesis and Deletion of the Carboxyl Terminus of Escherichia coli Ribonucleotide Reductase Protein R2 - Effects on Catalytic Activity and Subunit Interaction. Biochemistry 1992, 31, 4801–4807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Climent I; Sjöberg BM; Huang CY Carboxyl-Terminal Peptides as Probes for Escherichia coli Ribonucleotide Reductase Subunit Interaction: Kinetic Analysis of Inhibition Studies. Biochemistry 1991, 30, 5164–5171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Minnihan EC; Nocera DG; Stubbe J Reversible, Long-Range Radical Transfer in E. coli Class Ia Ribonucleotide Reductase. Acc. Chem. Res 2013, 46, 2524–2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Irebo T; Reece SY; Sjödin M; Nocera DG; Hammarström L Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer of Tyrosine Oxidation: Buffer Dependence and Parallel Mechanisms. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2007, 129, 15462–15464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Irebo T; Zhang M-T; Markle TF; Scott AM; Hammarström L Spanning Four Mechanistic Regions of Intramolecular Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer in a Ru(bpy)32+‒Tyrosine Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 16247–16254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Stubbe J; Nocera DG; Yee CS; Chang MCY Radical Initiation in the Class I Ribonucleotide Reductase: Long Range Proton Coupled Electron Transfer? Chem. Rev 2003, 103, 2167–2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Nick TU; Lee W; Koβmann S; Neese F; Stubbe J; Bennati M Hydrogen Bond Network between Amino Acid Radical Intermediates on the Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer Pathway of E. coli α2 Ribonucleotide Reductase. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 137, 289–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Greene BL; Taguchi AT; Stubbe J; Nocera DG Conformationally Dynamic Radical Transfer within Ribonucleotide Reductase. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 16657–16665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Wörsdörfer B; Conner DA; Yokoyama K; Livada J; Seyedsayamdost M; Jiang W; Silakov A; Stubbe J; Bollinger JM Jr.; Krebs C Function of the Diiron Cluster of Escherichia coli Class Ia Ribonucleotide Reductase in Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 8585–8593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Nick TU; Ravichandran KR; Stubbe J; Kasanmascheff M; Bennati M Spectroscopic Evidence for a H Bond Network at Y356 Located at the Subunit Interface of Active E. coli Ribonucleotide Reductase. Biochemistry 2017, 56, 3647–3656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Ravichandran KR; Taguchi AT; Wei Y; Tommos C; Nocera DG; Stubbe JA >200 meV Uphill Thermodynamic Landscape for Radical Transport in Escherichia coli Ribonucleotide Reductase Determined Using Fluorotyrosine-Substituted Enzymes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 13706–13716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Lin Q; Parker MJ; Taguchi AT; Ravichandran K; Kim A; Kang G; Shao J; Drennan CL; Stubbe J Glutamate 52-β at the α/β Subunit Interface of Escherichia coli Class Ia Ribonucleotide Reductase is Essential for Conformational Gating of Radical Transfer. J. Biol. Chem 2017, 292, 9229–9239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Ravichandran K; Olshansky L; Nocera DG; Stubbe J Subunit Interaction Dynamics of Class Ia Ribonucleotide Reductases: In Search of a Robust Assay. Biochemistry, 2020, 59, 1442–1453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Pizano AA; Lutterman DA; Holder PG; Teets TS; Stubbe J; Nocera DG Photo-Ribonucleotide Reductase β2 by Selective Cysteine Labeling with a Radical Phototrigger. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2012, 109, 39–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Greene BL; Stubbe J; Nocera DG Photochemical Rescue of a Conformationally Inactivated Ribonucleotide Reductase. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 15744–15752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Olshansky L; Pizano AA; Wei Y; Stubbe J; Nocera DG Kinetics of Hydrogen Atom Abstraction from Substrate by an Active Site Thiyl Radical in Ribonucleotide Reductase. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 16210–16216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Greene BL; Stubbe J; Nocera D Selenocysteine Substitution into a Class Ia Ribonucleotide Reductase. Biochemistry 2019, 58, 5074–5084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Seyedsayamdost MR; Yee CS; Stubbe J Site-Specific Incorporation of Fluorotyrosines into the R2 Subunit of E. coli Ribonucleotide Reductase by Expressed Protein Ligation. Nat. Protocol 2007, 2, 1225–1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Pizano AA; Olshansky L; Holder PG; Stubbe J; Nocera DG Modulation of Y356 Photooxidation in E. coli Class Ia Ribonucleotide Reductase by Y731 Across the α2:β2 Interface. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 13250–13253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Steeper JR; Steuart CD A Rapid Assay for CDP Reductase Activity in Mammalian Cell Extracts. Anal. Biochem 1970, 34, 123–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Olshansky L; Stubbe J; Nocera DG Charge-Transfer Dynamics at the α/β Subunit Interface of a Photochemical Ribonucleotide Reductase. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 1196–1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Kasanmascheff M; Lee W; Nick TU; Stubbe J; Bennati M Radical Transfer in E. coli Ribonucleotide Reductase: A NH2Y731/R411A-α Mutant Unmasks a New Conformation of the Pathway Residue 731. Chem. Sci 2016, 7, 2170–2178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Ravichandran KR; Minnihan EC; Lin Q; Yokoyama K; Taguchi AT; Shao J; Nocera DG; Stubbe J Glutamate 350 Plays an Essential Role in Conformational Gating of Long-Range Radical Transport in Escherichia coli Class Ia Ribonucleotide Reductase. Biochemistry 2017, 56, 856–868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Seyedsayamdost MR; Yee CS; Reece SY; Nocera DG Stubbe J pH Rate Profiles of FnY356-R2s (n = 2, 3, 4) in Escherichia coli Ribonucleotide Reductase: Evidence that Y356 is a Redox Active Amino Acid Along the Radical Propagation Pathway. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2006, 128, 1562–1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Seyedsayamdost MR; Reece SY; Nocera DG Stubbe, J. Mono, Di, Tri, and Tetra Substituted Fluorotyrosines: New Probes for Enzymes that use Tyrosyl Radicals in Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2006, 128, 1569–1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Minnihan EC; Young DD; Schultz PG; Stubbe J Incorporation of Fluorotyrosines into Ribonucleotide Reductase Using an Evolved, Polyspecific Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetase. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 15942–15945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Olshansky L; Greene BL; Finkbiener C; Stubbe J; Nocera DG Photochemical Generation of a Tryptophan Radical within the Subunit Interface of Ribonucleotide Reductase. Biochemistry 2016, 55, 3234–3240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Gray HB; Winkler JR Living with Oxygen. Acc. Chem. Res 2018, 51, 1850–1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Reece SY; Seyedsayamdost MR; Stubbe J; Nocera DG Photoactive Peptides for Light-Initiated Tyrosyl Radical Generation and Transport into Ribonucleotide Reductase. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2007, 129, 8500–8509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Reinhardt CR; Li P; Kang G; Stubbe J; Drennan CL; Hammes-Schiffer S Conformational Motions and Water Networks at the α/β Interface in E. coli Ribonucleotide Reductase. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 13768–13778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Wikström M; Krab K; Sharma V Oxygen Activation and Energy Conservation by Cytochrome c Oxidase. Chem. Rev 2018, 118, 2469–2490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Kaila VRI; Verkhovsky MI; Hummer G; Wikström M Glutamic Acid 242 is a Valve in the Proton Pump of Cytochrome c Oxidase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2008, 105, 6255–6259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Schmidt B; McCracken J; Ferguson-Miller S A Discrete Water Exit Pathway in the Membrane Protein Cytochrome c Oxidase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2003, 100, 15539–15542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Mannargudi MB; Deb S Clinical Pharmacology and Clinical Trials of Ribonucleotide Reductase Inhibitors: Is It a Viable Cancer Therapy? J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol 2017, 143, 1499–1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Aye Y; Li M; Long MJ; Weiss RS Ribonucleotide Reductase and Cancer: Biological Mechanisms and Targeted Therapies. Oncogene 2015, 34, 2011–2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Shao J; Zhou B; Chu B; Yen Y Ribonucleotide Reductase Inhibitors and Future Drug Design. Curr. Cancer Drug Tar 2006, 6, 409–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.