Abstract

The filamentous fungi Trichoderma spp. are widely used for plant growth promotion and disease control. They form stable symbiosis-like relationship with roots. Unlike plant pathogens and mycorrhizae, the molecular events leading to the development of this association is not well understood. Pathogens deploy effector proteins to suppress or evade plant defence. Indirect evidences suggest that Trichoderma spp. can also deploy effector-like proteins to suppress plant defence favouring colonization of roots. Here, using computer simulation, we provide evidence that Trichoderma virens may deploy analogues of host defence proteins to “neutralize” its own effector protein to minimize damage to host tissues, as one of the mechanisms to achieve a stable symbiotic relationship with plants. We provide evidence that T. virens Bys1 protein has a structure similar to plant PR5/thaumatin-like protein and can bind Alt a 1 with a very high affinity, which might lead to the inactivation of its own effector protein. We have, for the first time, predicted a fungal protein that is a competitive inhibitor of a fungal effector protein deployed by many pathogenic fungi to suppress plant defence, and this protein/gene can potentially be used to enhance plant defence through transgenic or other approaches.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13205-021-02652-8.

Keywords: Trichoderma, Bys1, Alt a 1, Symbiosis, Molecular dynamics, Protein–protein docking

Introduction

A plant–microbe interaction is driven by the levels of sophisticated co-evolution and the outcome could be beneficial, pathogenic or resistance (Wiesel et al. 2014). Depending on the lifestyle, pathogens can be classified as necrotrophs (kill the host first), biotrophs (can grow only on living cells) or hemibiotrophs (infect living cells and then switch to necrotrophy). Plants deploy several hormones to modulate defense against invading pathogens. In general, salicylic acid (SA) signalling is involved in defense against biotrophs/hemibiotrophs while jasmonic acid/ethylene (JA/ET) signaling is involved in defense against necrotrophs; these two pathways being antagonistic (Glazebrook 2005). Consequently, necrotrophs try to suppress JA signaling to promote SA signaling and biotrophs/hemibiotrophs act in reverse direction to favour infection. For example, addition of jasmonate to maize seedlings induces susceptibility against the hemibiotroph Colletrichum graminicola (Gorman et al. 2020) and addition of SA induces susceptibility against necrotrophs Botrytis cinerea and Alternaria solani in tomato (Rahman et al. 2012). Establishment of the symbiotic association of mycorrhizal fungi with roots also depends on fine-tuning of hormonal signaling to establish the beneficial interactions (Plett et al. 2014a, b). The arbuscular mycorrhizae are obligate intracellular biotrophs, while ectomycorrhizal fungi extensively colonize roots externally before forming the “Hertig net” intercellularly within root tissue (Liao et al. 2018; Gutjahr and Paszkowski 2009). The establishment of the parasitic relationship largely depends on the outcome of a two-way interaction that involves suppression of defence by effector proteins (predominantly small secreted cysteine-rich proteins, SSCPs), and their recognition by the host machinery to trigger resistance response. Effectors are also secreted by beneficial fungi to facilitate plant colonization (Gutjahr and Paszkowski 2009). Several pathogenesis-related proteins, like PR1, PR2 and PR5, are induced in plants in response to triggering of SA (a defence hormone) signalling. Pathogenic fungi often deploy effector molecules to bind to and inactivate such plant defense proteins. For example, Alt a 1 from several fungi is known to bind to the host defence protein PR5 (pathogenesis-related protein) to facilitate fungal colonization of plants (Gómez-Casado et al. 2014; Zhang et al. 2019; Nie et al. 2019). The ECM fungus Laccaria bicolor secretes mycorrhoza-induced effector protein MiSSP7 (interestingly this protein lacks cysteine residues) that stabilizes Populus JAZ6 (negative regulator of JA biosynthesis) to repress JA responsive genes so as to facilitate root colonization (Plett et al. 2014a). The AM fungi secrete an effector protein (SP7) to attenuate ET-controlled pathway to facilitate colonization (Kloppholz et al. 2011). Trichoderma spp. are plant-beneficial fungi not classified as true mycorrhizae, but are known to form stable interactions with roots (Harman et al. 2004). These fungi also extensively colonize roots externally and penetrate the epidermis and outer cortex to form largely intercellular (also intracellular) hyphal networks (Mendoza-Mendoza et al. 2018). There is only indirect evidence that Trichoderma spp. deploys effector-like proteins to suppress plant defence. Deletion of four root-repressed SSCPs (small secreted cysteine-rich proteins) individually improved systemic defence against Cochliobolus heterostrophus (a necrotroph) in maize (Lamdan et al. 2015). Recently, using computational analysis, we proposed that Trichoderma virens Alt a 1 might interact with a maize PR5/thaumatin-like protein to suppress SA-mediated defence, to gain access to roots (Kumar and Mukherjee 2020). SA-defense is activated when Trichoderma is colonizing roots, and suppressing this defence is required for colonization to be successful (Hermosa et al. 2012). Application of SA reduced the extent of endophytic colonization of tomato roots by T. harzianum, while JA application enhanced colonization (Martínez-Medina et al. 2017). T. harzianum systemically colonized the plant behaving like a pathogen on an SA-deficient Arabidopsis mutant (Alonso‐Ramírez et al. 2014). However, how Trichoderma switches from this initial aggressive colonization phase to a stable “biotrophic-like” relationship is not known. One hypothesis could be that Trichoderma deploys “suppressor” proteins to “neutralize” its own effector proteins, much like what the hemibiotrophic pathogen Magnaporthe oryzae does in its biotrophic phase (Sharpee et al. 2017). In case of ECM (ectomycorrhizae) also, initially JA pathway is suppressed to facilitate entry into roots, but induced late in colonization to limit fungal growth within roots (to achieve a stable symbiotic relationship) (Plett et al. 2014b). An analysis of the T. virens SSCPs for structural orthology revealed the presence of putative PRP-like proteins in the genome (Table S1). Among these, is a Bys1 (Blastomyces Yeast-phase Specific) protein which has structural similarity with plant thaumatin-like proteins. Gene for Bys1 is abundantly detected in the transcriptome/ESTs databases of Trichoderma spp. indicating high level of expression (Lorito et al. 2010; Vizcaíno et al. 2006; Malinich et al. 2019). This gene is upregulated in a mutant of T. virens with improved biocontrol properties, but downregulated in another mutant with a loss of biocontrol potential (Mukherjee et al. 2019; Pachauri et al. 2020). Despite its abundance in fungal genomes, the role of Bys1 in fungal physiology is not known [except for the human pathogenic dimorphic fungus Blastomyces dermatitidis (Krajaejun et al. 2010)]. Using computational analyses, we show here that T. virens Bys1 can bind to its effector protein Alt a 1 with very high affinity, thus contributing to a reduction in its aggressiveness once Trichoderma is inside the roots, in turn, facilitating the formation of a stable symbiotic relationship.

Materials and methods

Sequences and phylogenetic analysis

Bys1 domain containing protein sequences were downloaded from Uniprot database (www.uniprot.org). The entries were verified by NCBI CDD search for the presence of Bys1 domain. Presence of secretion signal was verified by SignalP 5.0 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/). Entries with additional domains and without secretion signal were removed. A total of 422 sequences were retained for analysis. One entry per genus, and all Trichoderma spp. sequences, were taken for phylogenetic tree construction by maximum likelihood method on MegaX server (www.megasoftware.net). For multiple alignment, Clustal Omega tool (www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/) was used.

Tertiary structure prediction and validation

Tertiary structure of Bys1 protein was constructed through both homology as well as de novo modelling approaches using I-TASSER server as previously described (Zhang 2008; Kumar et al. 2019). I-TASSER utilizes threading approach of LOMETS (Local Meta Threading Server) to identify best templates from PDB (Protein Data Bank) (Rose et al. 2010). Five models were generated and the best model having better C (confidence) and TM (Template modelling) scores was sorted. Tertiary structure of Alt a 1 was taken from our previous study (Kumar and Mukherjee 2020). Structure assessment of generated model was carried out by different quality check tools. Initially, structural similarity of Bys1 model was monitored by calculating the RMSD (root mean square deviation) between generated model and template. Further quality of model like stereochemical and geometrical analyses was monitored through SAVES (Structural Analysis and VErification Server), ProSA (Protein Structure Analysis) and QMEAN (Qualitative Model energy Analysis) web servers (Laskowski et al. 1993; Wiederstein and Sippl 2007; Benkert et al. 2008).

Molecular docking

Molecular docking was accomplished using two protein–protein (p–p) docking tools. Initially, p–p docking was carried by ClusPro server (Kozakov et al. 2017). Information about binding residues in both Alt a 1 and Bys1 is not available at both experimental and computational levels, therefore, ClusPro tool was recruited to dock the Alt a 1 and Bys1 proteins which used balance scoring function and predicted the p–p docking by shape complementarities of both partner proteins (Kumar and Saran 2018). Detailed procedure of p–p docking by ClusPro has been described in our previous study (Kumar and Mukherjee 2020). Interacting residues of Alt a 1 and Bys1 proteins were identified by molecular visualization tool from top predicted p–p model obtained through ClusPro docking server. Final docking of Alt a 1 and Bys1 was accomplished through HADDOCK server (Dominguez et al. 2003). HADDOCK is high ambiguity-driven docking program that integrates restraints from nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) chemical shift or mutagenesis data to derive the p–p docking. Binding or active residues identified through ClusPro docking complex were used as constraints to generate ambiguous interaction restrains (AIR) in HADDOCK program. HADDOCK performed p–p docking in three stages: (1) the randomization stage, (2) simulated annealing refinement stage and (3) final refinement with explicit solvent stage. In randomization stage, two partner proteins were placed ~ 150 Å from each other in space and each partner protein was rotated randomly followed by rigid body energy minimisation (EM). Around 1000 complex conformations were calculated out of which best 200 solutions in terms of intermolecular energies were then refined. In second stage, series of three simulating annealing refinements were performed where both backbone and side chains at the interface were allowed to move for allowing some conformational rearrangement. In final stage, a slow refinement in explicit solvent with TIP3P water molecules were performed followed by a series of molecular dynamics (MD) steps. Structures obtained from last stage were clustered based on pair-wise backbone root mean square deviation (RMSD) at the interface. Clusters were then analysed and sorted according to their average interaction energies and buried surface area. HADDOCK scores (E) were calculated in three stages as given in Eqs. (1)–(3).

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

where is the van der Waals energy, is electrostatic energy, is AIR restraint energy, is buried surface area, is the desolvation energy and is energy of other restraints data.

The best p–p docking complex with lowest HADDOCK score and intermolecular energies calculated from last stage was finally selected for further studies.

Molecular dynamics simulation

Apo (Alt a 1 and Bys1) and complex (Alt a 1-Bys1) proteins were subjected to molecular dynamics simulations in GROMACS suite (Van Der Spoel et al. 2005). Initially, GROMACS compatible files (.gro) and topologies for all proteins (apo and complex) were derived by pdb2gmx module with AMBER force field in GROMACS program and all three proteins were solvated in explicit solvent system with TIP3P water model in cubic box (Duan et al. 2003). A buffer zone of ~ 1.2 nm distance was kept in between edge of protein and boundary of box using editconf module. Genion script was used to add sodium and chloride ions to make systems neutral. Hence after, all systems were energy minimised through steepest descent integrated method. Before proceeding to final production run, all systems were equilibrated with constant number of particles, volume and temperature and constant number of particles, pressure and temperature. Temperature and pressure of 300 K and 1 bar were applied for 100 and 500 ps, respectively. Temperature and pressure were maintained by v-scale thermostat and Parrinello–Rahman barostat methods, respectively. Electrostatic interactions were handled through Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method and all bonds were constraints through LINCS (Linear Constraint Solver) algorithm. Production run of 100 ns time for each apo and complex systems were performed by applying 0.002 ps time steps, and MD snapshots were saved at every 10 ps.

Essential dynamics simulation and free energy landscape studies

Essential dynamics simulation also known as principle component analysis (PCA) is used to identify major or concerted motions exhibited by the macromolecules (Amadei et al. 1993). In this process, a series of eigenvectors (or principle components or PCs) with corresponding eigenvalues were produced which encompasses atomic fluctuations. These fluctuations correlate with the motions of particles that are directly related to the function of protein. Generally, first few PCs (PCs 15–20) have largest fluctuations. After removal of rotational and translational motions, a covariance matrix was generated and diagonalized as given in Eq. (4).

| 4 |

where and represent cartesian coordinates of particles i and j, respectively. Our analysis was restricted to backbone atoms to prevent the statistical noise. We have utilized stabled MD simulation trajectory (last 25 ns time) for PCA analysis. Quality of first 3 PCs was monitored through assessing their cosine content. To avoid the interpretation of random motions, cosine content was measured (Eq. 5) which should be < 0.2 (Hess 2000).

| 5 |

where is the projection of coordinates at time t on and T is the total simulation time.

Free energy landscape (FEL) or folding studies was performed on last 25 ns stabled MD simulation trajectory and measured as given in Eq. (6).

| 6 |

where kB, P are the Boltzmann constant and probability distribution, respectively, along some coordinate R. R is order parameters and it could be: RMSD, number of hydrogen bonds and Rg. Typically, free energy is plotted along RMSD and Rg giving rise to a (reduced) free energy surface (FES).

Data analyses and presentation

All MD simulation data were analysed in GROMACS utility. Total energy, root mean square deviation (RMSD), root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) and radius of gyration (Rg), solvent accessible surface area (SASA) and intra and inter H-bonds were measured by gmx energy, gmxrmsd, gmxrmsf, gmx gyrate, gmxsasa and gmxhbond modules, respectively. Secondary structures were derived through dictionary of secondary structure of protein (DSSP) method using do_dsspscript (Kabsch and Sander 1983). Essential dynamics and free energy landscape were analysed by gmxcovar, gmxanalyze, gmxanaeig, gmxtrjconv and gmx sham modules of Gromacs utility. All 3D figures for visualisation were depicted in PyMOL graphical system (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.3 Schrodinger, LLC) and 2D plot of p–p interaction was generated in DIMPLOT module of LigPlot program (Wallace et al. 1995).

Results

Sequences and phylogenetic analyses

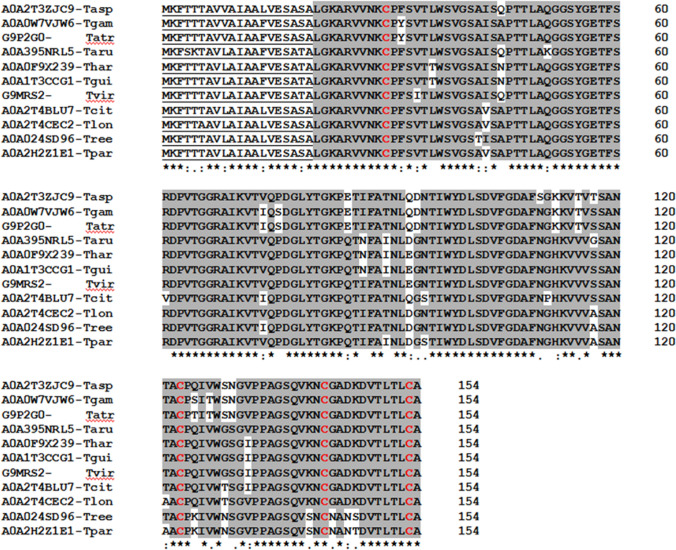

Bys1 protein is present only in Ascomycota and absent in the other three Divisions of fungi. Within Ascomycota, this protein is present in fungi belonging to Sordariomycetes, Eurotiomycetes and Dothideomycetes. Bys1 is present as a single copy gene in Trichoderma genomes, but many fungal genomes harbour two to four paralogues (two being very common, including in Blastomyces dermatitidis). A phylogenetic analysis revealed that Bys1 is highly conserved (including the signal peptide sequence) across species of Trichoderma (Fig. 1, Fig. S1) even though, the protein sequence is not highly conserved within the same genome of fungi harbouring paralogues of Bys1 (Fig. S2). T. virens Bys1 (Protein Id.TRIVIDRAFT_216106) protein is 154 amino acids in length, including 18 amino acid long N-terminal signal peptide.

Fig. 1.

Alignment of Bys1 sequences from Trichoderma spp. The signal peptide sequences are underlined

Tertiary structure of Bys1 mainly consists of β-sheets

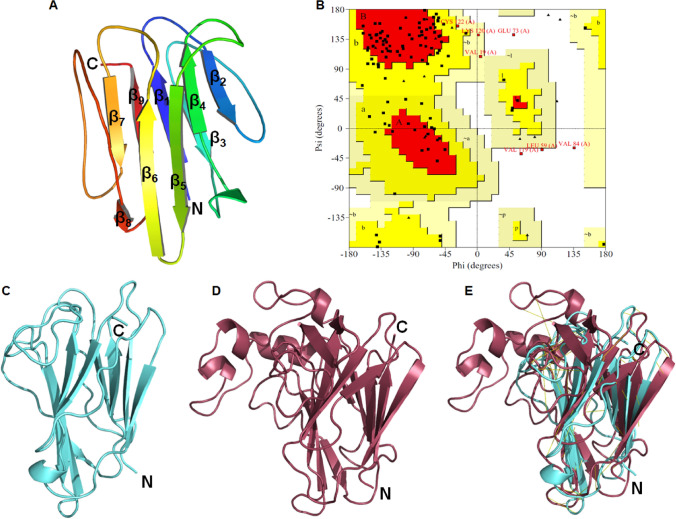

Tertiary structure of Trichoderma virens Bys1 was constructed by I-TASSER server. C- and TM-scores for Bys1 predicted model was 0.78 and 0.82, respectively (Table S2). I-TASSER used tobacco PR-5d protein as a template for building the Trichoderma Bys1 protein model. The crystal structure of PR-5d of tobacco was diffracted at resolution of 1.8 Å (Koiwa et al. 1999). PR-5d comprised of 208 amino acids (length from the crystal structure), and is an antifungal thaumatin-like protein consisting of common motif with negatively charged surface cleft having antifungal activity. It consists of 3 domains which are made up of 10 standard β-sheets, loops and small helix. Unlike PR-5d protein, the Bys1 model protein is 134 amino acid long and made up of 9 β-sheets connected with 8 turns or loops (Fig. 2a). However, like other thaumatin-like protein, Trichoderma Bys1 also formed cleft structure. Predicted 3D structure of Bys1 was validated by different quality check tools. Stereochemistry of Bys1 model was estimated by plotting phi and psi angles on Ramachandran plot and found that 58.3%, 38% and 3.7% of residues were placed in favoured, allowed and disallowed regions (Fig. 2b and Table S2). Overall structural similarities between Bys1 model were also examined through superposing the predicted model (Trichoderma Bys1 protein) with template (PR-5d) and measuring the RMSD. It was found that Bys1 model overlapped to PR-5d protein with 5.1 Å RMSD value (Fig. 2c–e). Overall structure quality of Bys1 protein was also monitored through ERRAT and Vertify3d modules of SAVES server. ERRAT score of Bys1 model was 75.2% indicating model has good overall quality and Verify3D results indicated 99.25% of the residues have 3D-1D compatibility in Bys1 model (Table S2). Further, structural quality of Bys1 model was examined through ProSA and QMEAN servers. ProSA Z-score of Bys1 model was − 5.34 indicating that predicted model has NMR like quality structure (Table S2). QMEAN score of Bys1 model was 0.52 indicating predicted model has good resolution structure as it lied in the range between 0 and 1 (Table S2). Above results indicated that predicted Trichoderma Bys1 protein has good stereochemistry, 3D geometry and overall good quality tertiary structure.

Fig. 2.

Tertiary model of Bys1 protein and its validation. a Tertiary structure of Bys1 protein displayed in publication cartoon mode with N- and C-terminals shown in blue to red colour, respectively. b Ramachandran plot of Bys1 protein whereas red, yellow and white areas of plot denoted favoured, allowed and disallowed regions, respectively and black dot represented amino acid residues, c Bys1 3D model, d Template for Bys1 model construction and e Superposition of Bys1 model and its template. Bys1 and template were shown in cyan and raspberry colour cartoon, respectively

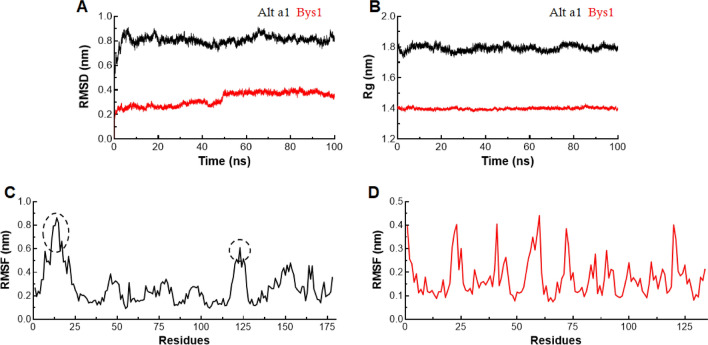

RMSD, RMSF and Rg analyses of apo proteins

Bys1 and Alt a 1 (previously optimised) 3D structures were subjected to MD simulations for 100 ns time. MD simulation is widely used to optimise the predicted models, to assess the stabilities of homology models and to examine the structure and conformational properties of protein (Kumar and Saran 2018). Here, long run MD simulations (100 ns each) were performed for Alt a 1 and Bys1 apo proteins and measured RMSD, RMSF and Rg values. Secondary structural properties such as secondary structures formation, surface area measurement and monitoring protein or protein–ligand interactions were also carried out. To assess the stabilities of apo proteins (Alt a 1 and Bys1), we calculated RMSD of backbone atoms at function of time for entire MD trajectories. RMSD of Alt a 1 showed consistent behaviour throughout the simulation period with an average RMSD value of ~ 0.82 nm except minor drifting at the end of simulation (Fig. 3a). Initially, RMSD of Bys1 protein showed consistent pattern up to 50 ns with an average value ~ 0.27 nm, but suddenly raised after 50 ns and showed equilibrium up to end of simulation period with ~ 0.39 nm RMSD (Fig. 3a). Protein globularity and compactness of Alt a 1 and Bys1 were measured by radius of gyration (Rg). Rg of both proteins showed consistent and constant behaviour with average Rg values for Alt a 1 and Bys1 proteins were ~ 1.8 and ~ 1.4 nm, respectively (Fig. 3b). Further, residual flexibilities of Alt a 1 and Bys1 proteins were checked through measuring RMSF. Residues located on N-terminal side showed high fluctuations up to ~ 0.6–0.8 nm in case of Alt a 1 while no noticeable fluctuations were observed in Bys1 protein (Fig. 3c, d). Further, residues or structural level RMSF inspection were monitored and it was found that Asn11 (Asparagine), Tyr12 (Tyrosine), Pro13 (Proline), Tyr14 (Tyrosine) and Pro17 occupied turn or loop region displaying higher mobilities in Alt a 1 while residues like Ala22 (Alanine), Ile23 (Isoleucine), Arg41 (Arginine), Leu59 (Leucine), Tyr60 (Tyrosine) Leu72 and Lys120 (Lysine) occupied turns connecting β-sheets showed moderate fluctuations in case of Bys1 protein (Fig. S3A, B). RMSD, RMSF and Rg results suggested that both Alt a 1 and Bys1 apo protein systems were stabled with consistent pattern.

Fig. 3.

MD simulation of Alt a 1 and Bys1 proteins. a Root mean square deviation in nanometer at y-axis and time in nanosecond at x-axis. b Radius of gyration in nanometer at y-axis and time in nanosecond at x-axis. c Root mean square fluctuation in nanometer at y-axis and amino acid residues at x-axis of Alt a 1 protein, and d Root mean square fluctuation in nanometer at y-axis and amino acid residues at x-axis of Bys1 protein. Alt a 1 and Bys1 proteins were labelled in black and red colour, respectively. Black dotted circles in lower graph represented highly fluctuated residues

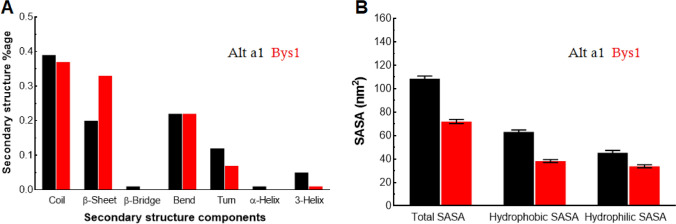

Secondary structure properties

Secondary structure components such as coils, helices, sheets, turns and bends of both Alt a 1 and Bys1 were measured during MD simulation. Alt a 1 exhibited 39%, 20%, 22%, and 12% of coils, β-sheets, bends and turns with minor percentage of β-bridges and helices (Fig. 4a). While, Bys1 exhibited 37%, 33%, 22%, and 7% of coils, β-sheets, bends and turns with negligible number of helices and no β-bridge (Fig. 4a). Pattern of secondary structure formation during MD simulation was examined through DSSP plot and it was found that α-helix of Alt a 1 occupied about 120–130 residues long get converted into bend and turn after ~ 30 ns time period while β-sheets showed consistent behaviour during entire period of simulation (Fig. S4A, B). The decreased composition of helix concomitantly increased the random moieties such as bends and turns which results in an increase in Alt a 1 protein flexibility. On the other hand, β-sheets of Bys1 protein showed consistent patterns with alterations in their length which get converted into coil and turns (Fig. S4C, D) resulting in decreased sheets content accompanied with increased coil and turn contents. Increasing coil and turn moieties make the Bys1 protein flexible too which results in formation of unstable secondary structures. Protein and protein–ligand stabilities of Alt a 1 and Bys1 proteins were monitored through measuring the protein–protein and protein-water hydrogen bonding (H-bond). As expected, Alt a 1 formed higher number of average protein–protein and protein–ligand H-bonds (91.7 ± 5.8 and 379.3 ± 13.6) as compared to Bys1 protein (73.6 ± 5.1 and 264 ± 11.9) due to larger size of Alt a 1 protein; the pattern of H-bond formation remained consistent throughout the simulation period (Fig. S5A, B). SASA is the ability of protein to interact with surrounding solvent or any other molecule like partner protein. This is further categorised into hydrophilic and hydrophobic SASA (Fig. 4b). Hydrophilic and hydrophobic SASAs of Alt a 1 and Bys1 showed consistent and stable behaviour throughout the MD simulation period (Fig. S5 C–E). Total SASA of Alt a 1 (108.5 ± 2.2) was higher than the SASA of Bys1 (72 ± 1.7) protein (Fig. 4b). Total SASA was mainly contributed by hydrophobic SASA of both Alt a 1 (63 ± 1.5) and Bys1 (38.2 ± 1.3) proteins, while hydrophilic SASA has less contribution and comparatively similar values (Alt a 1: 45 ± 1.9 and Bys1: 33 ± 1.3). Higher hydrophobic SASA is due to the occurrence of β-sheets that form hydrophobic cores in both Alt a 1 and Bys1 proteins.

Fig. 4.

Secondary structure and solvent accessible surface area (SASA) analyses. a Secondary structure components of Alt a 1 and Bys1 proteins and b Total, hydrophobic and hydrophilic SASAs of Alt a 1 and Bys1 proteins. Alt a 1 and Bys1 proteins were labelled in black and red colour, respectively

Alt a 1 and Bys1 protein–protein docking and interaction analysis

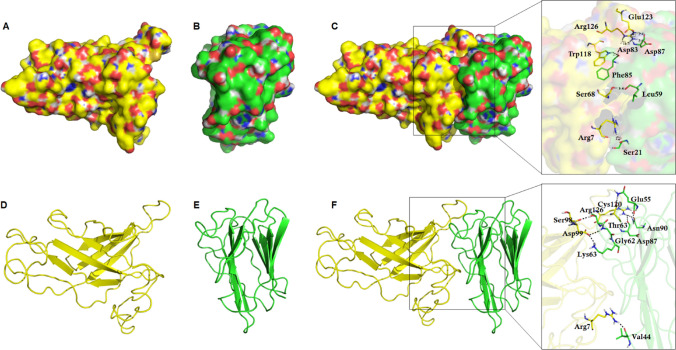

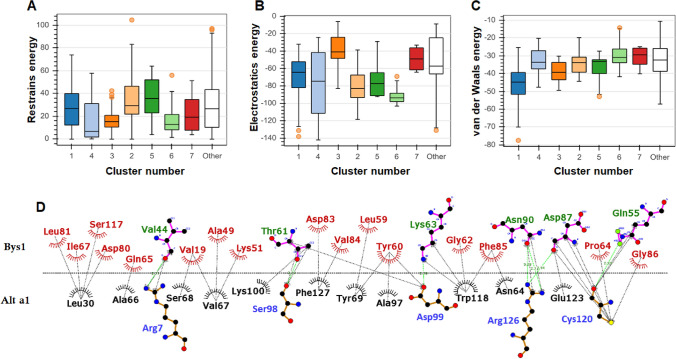

Alt a 1-Bys1 protein–protein (p–p) docking was performed by ClusPro and HADDOCK servers. Initially, ClusPro was recruited to predict the binding mode of Alt a 1 and Bys1 protein, where it performed docking on the basis of shape complementarity of both the partner proteins. Alt a 1 protein has two clefts on N-terminal and a turn connecting 5th and 6th β-sheets, respectively, which provide binding surface for the interaction of other protein such as Bys1 (Fig. 5a, d). A cleft formed by the turn connecting 5th and 6th β-sheets of Bys1 provides binding surface for the interaction of partner protein such as Alt a 1 (Fig. 5b, e). Thus, both proteins formed appropriated binding surfaces. Using shape morphology of both proteins and Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) approach, ClusPro predicted 26 clusters of Alt a 1-Bys1 docking complex, where each having different members or cluster size with different energy values (Table S3). Out of 26 clusters, top cluster was having maximum members with lowest energy (− 845.7) (Fig. 5c). p–p complex predicted by ClusPro server exhibited nine hydrogen bonds between Alt a 1 and Bys1 proteins (Table S4). Later, simulation-based protein–protein docking of Alt a 1 and Bys1 proteins were performed through HADDOCK server. HADDOCK used series of steps (discussed in “Materials and methods”) where best docking pose was predicted which was having minimum HADDOCK score (Fig. 5f). HADDOCK used 186 structures to construct 7 clusters, topmost cluster had largest cluster size and lowest HADDOCK score. HADDOCK score, desolvation, vander Waals and electrostatic energies versus interface RMSDs were calculated and cluster 1 was found to behaving − 118.0 ± 8.9, − 67.0 ± 7.1, − 116.8 ± 19.4, − 29.5 ± 2.3 and 18.0 ± 10.39 of HADDOCK score, Vander Waals, electrostatic, desolvation and restraints violation energies, respectively (Fig. S6, Table 1 and Fig. 6a–c). Electrostatic energy was major binding forces during protein–protein interaction (Table 1 and Fig. 6b). Furthermore, the binding strength of Alt a 1 and Bys1 proteins was calculated by measuring the hydrophobic and hydrophilic interactions through 2D plot of p–p complex (Fig. 6d). During p–p complex, Arg7 (Arginine), Ser98 (Serine), Asp99 (Aspartate), Cys120 (Cysteine) and Arg126 of Alt a 1 formed hydrophilic interactions with Val44 (Valine), Thr61 (Threonine), Lys63 (Lysine), Asn90 (Asparagine), Asp87 and Gln55 (Glutamine) of Bys1 protein. In addition, p–p complex formation was also bonded with fair number of hydrophobic bonds (Fig. 6d). Lowest values of HADDOCK score and large numbers of hydrophilic and hydrophobic bonds suggested that Alt a 1 formed stabled complex with partner protein such as Bys1.

Fig. 5.

Protein–protein docking of Alt a 1 and Bys1 proteins. a, d Tertiary structure of Alt a 1 protein in surface and cartoon modes, b, e Tertiary structure of Bys1 protein in surface and cartoon modes and c, f Protein–protein docking complex predicted from ClusPro and HADDOCK server, respectively. Residues involved in p–p interactions were shown in rectangular boxes. Alt a 1 and Bys1 proteins were labelled in yellow and green colour, respectively. Interacting residues were shown in stick mode with three letter amino acid code and hydrogen bonds were depicted in black dotted lines

Table 1.

Alt a 1 and Bys1 protein–protein interaction energies

| Cluster # | HADDOCK score | Cluster size | Vander Waal energy | Electrostatic energy | Desolvation energy | Restraints violation energy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | − 118.0 ± 8.9 | 70 | − 67.0 ± 7.1 | − 116.8 ± 19.4 | − 29.5 ± 2.3 | 18.0 ± 10.39 |

| 2 | − 85.5 ± 1.3 | 51 | − 42.9 ± 1.5 | − 92.6 ± 5.7 | − 25.7 ± 0.8 | 15.6 ± 8.53 |

| 3 | − 87.9 ± 3.1 | 19 | − 47.0 ± 2.0 | − 62.0 ± 15.6 | − 30.0 ± 1.3 | 14.8 ± 6.34 |

| 4 | − 88.2 ± 1.7 | 18 | − 38.1 ± 2.5 | − 111.8 ± 12.1 | − 29.7 ± 1.9 | 19.5 ± 18.45 |

| 5 | − 80.4 ± 9.5 | 11 | − 45.6 ± 5.7 | − 91.5 ± 0.8 | − 19.7 ± 3.7 | 31.9 ± 21.70 |

| 6 | − 77.8 ± 6.4 | 6 | − 34.6 ± 4.4 | − 96.2 ± 5.7 | − 24.8 ± 2.5 | 8.5 ± 4.74 |

| 7 | − 65.9 ± 10.7 | 4 | − 31.0 ± 6.1 | − 48.6 ± 13.7 | − 27.5 ± 2.4 | 23.4 ± 18.67 |

Fig. 6.

Protein–protein interaction analysis. a Restrains energy of seven clusters, b Electrostatic energy, c Van der Waals energy and d 2D interaction plot of p–p complex. In 2D plot, interacting residues involved in hydrophobic bonding of Alt a 1 and Bys1 were represented in black and red colour, respectively, while interacting residues involved in hydrophilic bonding of Alt a 1 and Bys1 were represented in blue and green colour, respectively. Hydrophobic and hydrophilic bonds were labelled as black and green colour, respectively

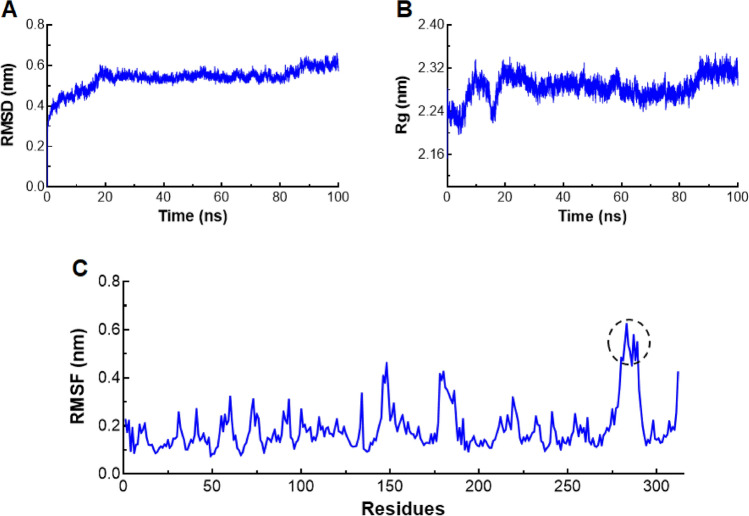

RMSD, RMSF and Rg analyses of Alt a 1-Bys1 complex protein

Stability of p–p complex (Alt a 1-Bys1) was further examined through measuring the RMSD, RMSF and Rg in 100 ns time of MD simulation. RMSD of backbone of p–p complex was measured with respect to equilibrium structure and plotted as function of time. RMSD of p–p complex stabilized after ~ 25 ns with an average value ~ 0.58 nm until slight uplift at the end of simulation period (after ~ 90 ns) with consistent and an average RMSD value of 0.61 nm (Fig. 7a). Similar pattern of Rg was also observed as consistent behaviour was noticed after ~ 30 ns time with an average value ~ 2.28 nm and slightly upraised after ~ 90 ns time with an average Rg of ~ 2.30 nm (Fig. 7b). RMSF at function of amino acid residues were plotted and found that no major fluctuation was observed except for the amino acids present at the end of p–p complex with an average RMSF value > 0.5 nm (Fig. 7c). Structural level inspection indicated that turns connecting 1, 2 and 7 sheets of Alt a 1 which were located at the opposite end of interacting interface fluctuated more as compared to the rest of p–p complex (Fig. S7). However, this fluctuation was not observed during apo Alt a 1 protein, indicating that this region might play an important role during protein–protein interaction. Consistent and stable behaviour of RMSD, RMSF and Rg results demonstrated that Alt a 1-Bys1 formed a stable p–p complex.

Fig. 7.

MD simulation Alt a 1-Bys1 p–p complex. a Root mean square deviation in nanometer at y-axis and time in nanosecond at x-axis. b Radius of gyration in nanometer at y-axis and time in nanosecond at x-axis, and c root mean square fluctuation in nanometer at y-axis and amino acid residues at x-axis of p–p complex. Black dotted circles in lower graph represented highly fluctuated residues

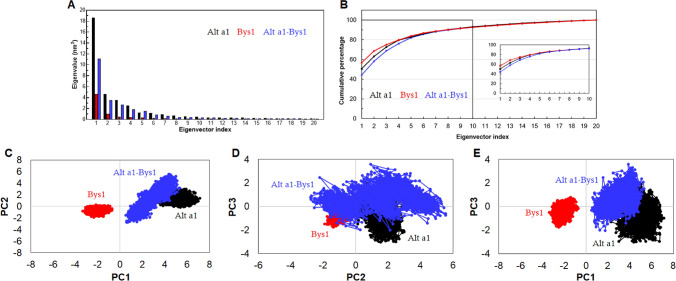

Collective mode of motions of apo and complex proteins

Collective or concerted motions of apo and complex proteins were studied by essential dynamics or principle component analysis. Collective motions were obtained during simulations which are likely to be significant for the biological function (Maurya et al. 2020). Dominant modes and conformational changes occurred during apo and complex proteins, elucidated by utilizing the stable MD simulation trajectories of ~ 75–100 ns. First 20 eigenvectors were plotted, out of which, first 3 eigenvectors displayed higher eigen values (Fig. 8a, b). Quality of first three eigenvectors or principle components (PCs) were measured through cosine content analysis and it was found that first 2 PCs (PC1 and PC2) of ~ 75–100 ns time-simulated trajectories showed low cosine content (< 0.2) and used for further analysis (Table 2). Cumulative percentage of root mean square fluctuations for first three eigenvectors were 72.6% for Alt a 1, 74.9% for Bys1 and 68.8% for Alt a 1-Bys1 complex proteins(Fig. 8b, Fig. S8A–C). Conformational sampling of apo Alt a 1 and Bys1 along with Alt a 1-Bys1 complex were examined through plotting the first 3 PCs (PC1, PC2 and PC3) in phase space. It was observed that sampling in phase space of Alt a 1 and Bys1 apo proteins for all three PCs occupied less subspace than Alt a 1-Bys1 complex (Fig. 8c–e). PCA results suggested that first three PCs of Alt a 1-Bys1 complex exhibited major motions with larger conformational space. Furthermore, major motions occurred at binding cleft of apo Alt a 1 protein as compared to Bys1 protein as depicted in porcupine structures (Fig. S9A, B). In contrast, the region opposite to binding cleft of Alt a 1 exhibited similar motion when bonded with partner protein (Alt a 1-Bys1) implying that this region might be involved in the formation of p–p complex as also observed in MD simulation of complex protein (Fig. S9C).

Fig. 8.

Principle component analysis of apo and p–p complex proteins. a Projection of first 20 eigenvectors with corresponding eigenvalues, b Cumulative percentage of first 20 and 10 eigenvectors or PCs, c projection of eigenvector 1 (PC1) and eigenvector 2 (PC2) in phase space, d Projection of eigenvector 2 (PC2) and eigenvector 3 (PC3) in phase space and e projection of eigenvector 1 (PC1) and eigenvector 3 (PC3) in phase space. Alt a 1 and Bys1 apo proteins were represented as black and red colour while Alt a 1-Bys1 complex protein represented as blue colour, respectively

Table 2.

Cosine content analyses of first three PCs

| 0–25 ns | 25–50 ns | 50–75 ns | 75–100 ns | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alt a 1 | ||||

| PC1 | 0.07 | 0.21 | 0.32 | 0.0037 |

| PC2 | 0.59 | 0.000087 | 0.34 | 0.05 |

| Bys1 | ||||

| PC1 | 0.024 | 0.28 | 0.37 | 0.00045 |

| PC2 | 0.087 | 0.0002 | 0.68 | 0.025 |

| Alt a 1-Bys1 | ||||

| PC1 | 0.24 | 0.15 | 0.016 | 0.069 |

| PC2 | 0.069 | 0.001 | 0.000007 | 0.043 |

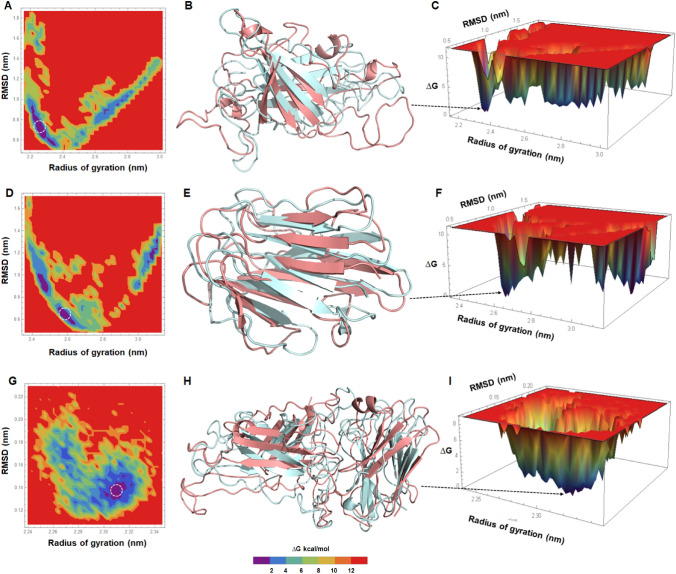

Conformational and folding studies

Stable conformation at minimum energy level of apo Alt a 1, Bys1 and Alt a 1-Bys1 complex was elucidated by free energy landscape studies where minimum values of ∆G were obtained and structural changes were monitored. Different energy barriers for each apo and complex proteins were examined through 2D and 3D plots by taking RMSD and Rg values for each protein systems (Fig. 9). FEL plots of apo protein showed many clusters dispersed with shallow basins while FEL plot of the complex displayed very few clusters with deep and narrow basin (Fig. 9a, c, d, f, g, i). Alt a 1 and Bys1 apo protein showed minimum energy values (∆G = 0) at RMSD and Rg of ~ 0.7, ~ 2.22, ~ 0.62 and ~ 2.26 nm, respectively (Fig. 9a, d), while Alt a 1-Bys1 complex showed minimum energy at RMSD and Rg of ~ 0.14, ~ 2.31 nm, respectively (Fig. 9g). Structures obtained from minimum energy state for each apo and complex proteins and superimposed with initial structure, found that major structural changes were accompanied in loop and turn moieties of each protein (Fig. 9b, e, h). This is possible because loop and turn regions of protein are flexible in nature and they help in folding and bring the protein at stable conformation at minimum energy state. FEL results suggested that Alt a 1-Bys1 complex protein formed stable complex with most favourable conformation as compared to Alt a 1 and Bys1 protein alone.

Fig. 9.

Free energy landscape studies. a 2D plot of Alt a 1, b tertiary structure extracted from initial time point (cyan) and superimposed with minimum ∆G structure (salmon), c 3D FEL plot of Alt a 1 apo protein, d 2D plot of Bys1, e tertiary structure extracted from initial time point (cyan) and superimposed with minimum ∆G structure (salmon), f 3D FEL plot of Bys1 apo protein, g 2D plot of Alt a 1-Bys1, h Tertiary structure extracted from initial time point (cyan) and superimposed with minimum ∆G structure (salmon) and i 3D FEL plot of Alt a 1-Bys1 complex protein. ∆G was measured in kilocalorie per mol

Discussion

Bys1 gene was discovered in the dimorphic human pathogenic fungus Blastomyces dermatitidis as a transcript induced during shift from 25 °C (mycelial form) to 37 °C (yeast form) (Burg and Smith 1994). Silencing of this gene using RNAi did not impair the virulence, but altered the morphology (pseudohyphal cells on prolonged culture) at 37 °C (Krajaejun et al. 2010). However, since this fungal genome harbours two paralogues, a functional redundancy cannot be ruled out. The function of this small, cysteine-rich, secreted protein is not known in any other fungus. A survey of the sequenced fungal genomes revealed that this gene is restricted to three classes of Ascomycotina, i.e., Sordariomycetes, Eurotiomycetes and Dothideomycetes. Interestingly, these three groups of fungi harbour most of the pathogenic, toxigenic and allergenic fungi. Ubiquitous presence, and in many cases, presence of multiple paralogues are indicative of important roles of Bys1 in the physiology of fungi. In the plant-beneficial fungi Trichoderma, the gene is present as a single copy, but very high level of conservancy (near 100% across species) and transcription is indicative of a biological role, which is not known yet.

Trichoderma spp. colonize plant roots and impart induced defence against invading pathogens (Mendoza-Mendoza et al. 2018). However, since these fungi are not considered as typical mycorrhizae, not much research has been diverted to understand this plant–fungal association at the molecular level. Especially lacking is the information on how Trichoderma breaches plant defence and then forms a stable relationship with plants. Several small, secreted, cysteine-rich, effector-like proteins are downregulated after 96 h of co-incubation of T. virens with maize roots (Lamdan et al. 2015). Deletion of four of them resulted in an enhanced induced defence against a plant pathogen, when compared with the wild type (Lamdan et al. 2015). One such protein Alt a 1 is known to be secreted by plant pathogens to suppress host defence by binding with PR5, a defence protein (Gómez-Casado et al. 2014; Zhang et al. 2019; Nie et al. 2019). Using computer simulation, we predicted that Trichoderma Alt a 1 also can bind to plant PR5, and we proposed that this could be one strategy deployed by T. virens to suppress plant defence during colonization (Kumar and Mukherjee 2020). However, how Trichoderma switches from breaching of the plant defence to a stable symbiont, is not known yet. Here we propose a hypothesis that Trichoderma may deploy orthologues of plant defence proteins to neutralize its own effectors to stabilize the symbiosis. Using molecular modelling and docking analysis, we predict here that Trichoderma Bys1 protein is a structural orthologue of plant PR5 protein and that it can bind to Alt a 1 with a very high affinity, forming a stable structure. Our hypothesis is supported by the fact that several pathogen-derived SSCPs favour biotrophic growth phase by blocking the host cell death reaction induced by Nep1 [inducer of cell death, secreted by the hemibiotrophic pathogen Magnaporthe oryzae (Sharpee et al. 2017)]. The physical interaction of Trichoderma Alt a 1 with Bys1 needs to be verified using laboratory tools like yeast 2-hybrid system or co-immunoprecipitation. Nevertheless, using computational tool, we propose here a novel hypothesis on plant–microbe interactions, and also indicate a possible biological role of the abundantly expressed Bys1 gene. Our analysis shows that Bys1 protein can act as an inhibitor of one of the most common effector proteins Alt a 1 that are secreted by plant-beneficial and pathogenic fungi to suppress host defense. It might thus be possible to make use of the Bys1 protein/gene to improve plant defense, e.g., through generation of transgenic plants expressing this gene. Expression of several Trichoderma genes in plants has proven to be a viable strategy for imparting tolerance to biotic and abiotic stresses (Nicolás et al. 2014).

Conclusion

Using computational analysis, we predicted that the Bys1 protein from the plant-beneficial fungus T. virens has a structure similar to that of the pathogenesis-related plant defence protein PR5. We also provide in silico evidence that T. virens Bys1 binds with a Trichoderma effector protein Alt a 1 with high affinity. We thus hypothesize that Bys1 of T. virens is involved in stabilizing the symbiosis-like relationship by neutralizing its own effector protein, once the fungus had successfully colonized the roots. Bys1 is thus a biotechnologically relevant fungal protein that can be used for plant disease management by reducing susceptibility to a common effector protein Alt a 1.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

P.K.M. thanks Dr. S.K. Ghosh, Associate Director, Bioscience Group, BARC, for encouragement and support.

Funding

The work was supported by institutional funding in the absence of any externally funded projects.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

None to declare.

Contributor Information

Rakesh Kumar, Email: rakeshkapoor.jnu@gmail.com.

Prasun K. Mukherjee, Email: prasunmukherjee1@gmail.com

References

- Alonso-Ramírez A, Poveda J, Martín I, Hermosa R, Monte E, Nicolás C. Salicylic acid prevents Trichoderma harzianum from entering the vascular system of roots. Mol Plant Pathol. 2014;15:823–831. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amadei A, Linssen AB, Berendsen HJ. Essential dynamics of proteins. Proteins Struct Funct Bioinform. 1993;17:412–425. doi: 10.1002/prot.340170408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benkert P, Tosatto SC, Schomburg D. QMEAN: a comprehensive scoring function for model quality assessment. Proteins Struct Funct Bioinform. 2008;71:261–277. doi: 10.1002/prot.21715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burg EF, Smith LH. Cloning and characterization of bys1, a temperature-dependent cDNA specific to the yeast phase of the pathogenic dimorphic fungus Blastomyces dermatitidis. Infect Immun. 1994;62:2521–2528. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.6.2521-2528.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez C, Boelens R, Bonvin AM. HADDOCK: a protein–protein docking approach based on biochemical or biophysical information. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:1731–1737. doi: 10.1021/ja026939x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan Y, Wu C, Chowdhury S, et al. A point-charge force field for molecular mechanics simulations of proteins based on condensed-phase quantum mechanical calculations. J Comp Chem. 2003;24:1999–2012. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glazebrook J. Contrasting mechanisms of defense against biotrophic and necrotrophic pathogens. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2005;43:205–227. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.43.040204.135923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Casado C, Murua-García A, Garrido-Arandia M, et al. Alt a 1 from Alternaria interacts with PR5 thaumatin-like proteins. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:1501–1508. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.02.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman Z, Christensen SA, Yan Y, et al. Green leaf volatiles and jasmonic acid enhance susceptibility to anthracnose diseases caused by Colletotrichum graminicola in maize. Mol Plant Pathol. 2020;21:702–715. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutjahr C, Paszkowski U. Weights in the balance: jasmonic acid and salicylic acid signaling in root-biotroph interactions. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2009;22:763–772. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-22-7-0763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harman GE, Howell CR, Viterbo A, Chet I, Lorito M. Trichoderma species—opportunistic, avirulent plant symbionts. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:43–56. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermosa R, Viterbo A, Chet I, Monte E. Plant-beneficial effects of Trichoderma and of its genes. Microbiology. 2012;158:17–25. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.052274-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess B. Similarities between principal components of protein dynamics and random diffusion. Phys Rev E. 2000;62:8438. doi: 10.1103/physreve.62.8438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabsch W, Sander C. Dictionary of protein secondary structure: pattern recognition of hydrogen-bonded and geometrical features. Biopolym Orig Res Biomol. 1983;22:2577–2637. doi: 10.1002/bip.360221211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloppholz S, Kuhn H, Requena N. A secreted fungal effector of Glomus intraradices promotes symbiotic biotrophy. Curr Biol. 2011;21:1204–1209. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koiwa H, Kato H, Nakatsu T, Oda JI, Yamada Y, Sato F. Crystal structure of tobacco PR-5d protein at 1.8 Å resolution reveals a conserved acidic cleft structure in antifungal thaumatin-like proteins. J Mol Biol. 1999;286:1137–1145. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozakov D, Hall DR, Xia B, et al. The ClusPro web server for protein–protein docking. Nat Prot. 2017;12:255. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2016.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krajaejun T, Wüthrich M, Gauthier GM, Warner TF, Sullivan TD, Klein BS. Discordant influence of Blastomyces dermatitidis yeast-phase-specific gene BYS1 on morphogenesis and virulence. Infect Immun. 2010;78:2522–2528. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01328-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R, Mukherjee PK. Trichoderma virens Alt a 1 protein may target maize PR5/thaumatin-like protein to suppress plant defence: an in silico analysis. Physiol Mol Plant Path. 2020;112:101551. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R, Saran S. Structure, molecular dynamics simulation, and docking studies of Dictyostelium discoideum and human STRAPs. J Cell Biochem. 2018;119:7177–7191. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R, Maurya R, Saran S. Introducing a simple model system for binding studies of known and novel inhibitors of AMPK: a therapeutic target for prostate cancer. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2019;37:781–795. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2018.1441069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamdan NL, Shalaby S, Ziv T, Kenerley CM, Horwitz BA. Secretome of Trichoderma interacting with maize roots: role in induced systemic resistance. Mol Cell Prot. 2015;14:1054–1063. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M114.046607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski RA, MacArthur MW, Moss DS, Thornton JM. PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J Appl Crystallogr. 1993;26:283–291. [Google Scholar]

- Liao D, Wang S, Cui M, Liu J, Chen A, Xu G. Phytohormones regulate the development of arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:3146. doi: 10.3390/ijms19103146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorito M, Woo SL, Harman GE, Monte E. Translational research on Trichoderma: from 'omics to the field. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2010;48:395–417. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-073009-114314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malinich EA, Wang K, Mukherjee PK, Kolomiets M, Kenerley CM. Differential expression analysis of Trichoderma virens RNA reveals a dynamic transcriptome during colonization of Zea mays roots. BMC Genom. 2019;20(1):280. doi: 10.1186/s12864-019-5651-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Medina A, Appels FV, van Wees SC. Impact of salicylic acid-and jasmonic acid-regulated defences on root colonization by Trichoderma harzianum T-78. Plant Signal Behav. 2017;12(8):e1345404. doi: 10.1080/15592324.2017.1345404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurya R, Kumar R, Saran S. AMPKα promotes basal autophagy induction in Dictyostelium discoideum. J Cell Physiol. 2020;235:4941–4953. doi: 10.1002/jcp.29373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza-Mendoza A, Zaid R, Lawry R, Hermosa R, et al. Molecular dialogues between Trichoderma and roots: role of the fungal secretome. Fun Biol Rev. 2018;32:62–85. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee PK, Mehetre ST, Sherkhane PD, et al. A novel seed-dressing formulation based on an improved mutant strain of Trichoderma virens, and its field evaluation. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:1910. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolás C, Hermosa R, Rubio B, Mukherjee PK, Monte E. Trichoderma genes in plants for stress tolerance-status and prospects. Plant Sci. 2014;228:71–78. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie HZ, Zhang L, Zhuang HQ, et al. The secreted protein MoHrip1 is necessary for the virulence of Magnaporthe oryzae. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(7):1643. doi: 10.3390/ijms20071643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachauri S, Sherkhane PD, Kumar V, Mukherjee PK. Whole genome sequencing reveals major deletions in the genome of M7, a gamma ray-induced mutant of Trichoderma virens that is repressed in conidiation, secondary metabolism, and mycoparasitism. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:1030. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plett JM, Daguerre Y, Wittulsky S, et al. Effector MiSSP7 of the mutualistic fungus Laccaria bicolor stabilizes the Populus JAZ6 protein and represses jasmonic acid (JA) responsive genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2014;111:8299–8304. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1322671111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plett JM, Khachane A, Ouassou M, Sundberg B, Kohler A, Martin F. Ethylene and jasmonic acid act as negative modulators during mutualistic symbiosis between Laccaria bicolor and Populus roots. New Phytol. 2014;202:270–286. doi: 10.1111/nph.12655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman TA, Oirdi ME, Gonzalez-Lamothe R, Bouarab K. Necrotrophic pathogens use the salicylic acid signaling pathway to promote disease development in tomato. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2012;25:1584–1593. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-07-12-0187-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose PW, Beran B, Bi C, et al. The RCSB Protein Data Bank: redesigned web site and web services. Nucl Acids Res. 2010;9(suppl_1):D392–D401. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpee W, Oh Y, Yi M, et al. Identification and characterization of suppressors of plant cell death (SPD) effectors from Magnaporthe oryzae. Mol Plant Pathol. 2017;18:850–863. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Spoel D, Lindahl E, Hess B, Groenhof G, Mark AE, Berendsen HJ. GROMACS: fast, flexible, and free. J Comp Chem. 2005;26:1701–1718. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vizcaíno JA, González FJ, Suárez MB, et al. Generation, annotation and analysis of ESTs from Trichoderma harzianum CECT 2413. BMC Genom. 2006;7(1):193. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace AC, Laskowski RA, Thornton JM. LIGPLOT: a program to generate schematic diagrams of protein-ligand interactions. Prot Eng Des Sel. 1995;8:127–134. doi: 10.1093/protein/8.2.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiederstein M, Sippl MJ. ProSA-web: interactive web service for the recognition of errors in three-dimensional structures of proteins. Nucl Acids Res. 2007;35(suppl_2):W407–W410. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiesel L, Newton AC, Elliott I, et al. Molecular effects of resistance elicitors from biological origin and their potential for crop protection. Front Plant Sci. 2014;5:655. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. I-TASSER server for protein 3D structure prediction. BMC Bioinform. 2008;9(1):40. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Gao Y, Liang Y, Dong Y, Yang X, Qiu D. Verticillium dahliae PevD1, an Alt a 1-like protein, targets cotton PR5-like protein and promotes fungal infection. J Exp Bot. 2019;70:613–626. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ery351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.