Abstract

Over 295,000 patients from 2016 to 2018 in a national database were grouped into normal weight (BMI 18.5 to <25 kg/m2), overweight (25 to <30), type-1 obese (30 to <35), type-2 obese (35 to <40), and type-3 obese (40 or higher). Differences in resource utilization and complication rates across BMI categories were compared. In comparison to normal weight patients, overweight and obese patients undergoing TJA were at risk for increased resource utilization and various early complications. Patients undergoing TKA with a BMI up to 45 kg/m2 are at similar risk for 30-day postoperative complications when compared to type-1 obese patients.

Keywords: Body mass index, BMI, Total knee arthroplasty, Total hip arthroplasty, Obesity, Complications

1. Introduction

In recent years, the average body mass index (BMI) of the adult population has been climbing, with over 30% of the US population categorized as obese.1 The prevalence of obesity is expected to increase in upcoming years, with extreme projections estimating 78.9% of American adults will be overweight or obese by the year 2030.2 The projected rise in the prevalence of obesity is accompanied by rising obesity related health care costs, which may exceed $860 billion and account for 15.8%–17.6% of total health care costs by 2030.2 Increased risk for development of osteoarthritis (OA) is one of the many harmful health effects of obesity.3, 4, 5 The biomechanical loading of joints contributes to the onset and progression of the disease and is affected by obesity. Additionally, the role adipose tissue-derived cytokines play in cartilage and bone function further links obesity and osteoarthritis.3 Adipokines are pleotropic molecules that are upregulated by chondrocytes and other cell types from joints that promote and sustain inflammatory processes and extracellular matrix degradation leading to the development of osteoarthritis.3 The risk of developing hip or knee arthritis increases in a stepwise manner with increasing BMI, as evidenced by a 4.7 fold increase in the risk of developing knee OA with type II obesity (BMI 35–39.9 kg/m2) in comparison to normal weight individuals.5

Total joint arthroplasty (TJA) is one of the most commonly performed procedures in the US and has proved successful in alleviating pain from advanced hip or knee OA.6 Debate regarding the safety of TJA for patients with a high BMI remains. Some studies have found a higher risk of post-operative complications for overweight or obese patients, including increased risk of infection, pulmonary embolism, wound complications, and reoperation.7, 8, 9, 10 In contrast, few studies have found no increased risk of complications associated with performance of surgery on patients with an elevated BMI.11 In response to the evidence linking obesity with postoperative complications after TJA, arthroplasty surgeons are increasingly implementing strict BMI cutoffs for surgical candidates, and requiring weight loss to meet these thresholds prior to surgery. Unfortunately, the mere restriction of access to TJA for obese patients has not proven successful for incentivizing weight loss.12 The aim of this study is to compare postoperative outcomes across various BMI classifications to identify the level of increased risk associated with performance of THA or TKA in obese patients, and to identify procedure specific BMI guidelines that may aid in the selection of surgical candidates.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Data source

This study was deemed institutional review board exempt by the institutional clinical research committee. The American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS-NSQIP) 2016–2018 national database was retrospectively reviewed to identify patients undergoing primary THA or TKA. The ACS-NSQIP database includes patient demographics, comorbidities, preoperative lab values, procedure details, diagnosis codes, and 30-day postoperative outcomes from over 700 private and academic medical centers in the United States.13 The structure of the ACS-NSQIP database has been previously described.7,9,14 In summary, the program uses trained surgical clinical reviewers to collect data on over 150 variables using standardized definitions, and conducts audits to ensure inter-rater reliability.13 Over 3 million total cases across surgical specialties are included in the 2016–2018 ACS-NSQIP national database.13

2.2. Patient population and variables collected

Patients undergoing primary THA (Current Procedural Terminology [CPT] code 27130) or TKA (CPT code 27447) were included in the study. Patients with a BMI less than 18.5 kg/m2 (underweight), disseminated cancer, or infection at the time of surgery were excluded. Patient demographics (BMI, age, gender, race), surgical characteristics (American Society of Anesthesiologists [ASA] score, use of general anesthesia), smoking status, and comorbidities at the time of surgery (partial or total functional dependence, dyspnea at rest or on mild exertion, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD], congestive heart failure [CHF], diabetes mellitus [DM; includes both insulin and non-insulin dependent], renal failure, dialysis, chronic steroid use, and bleeding disorder) were recorded. Thirty-day postoperative outcomes were classified as either measures of resource utilization or complications. Resource utilization included operative time, hospital length of stay (LOS), discharge to a skilled nursing facility (SNF), readmission, and return to the operating room (OR). Complications included mortality, periprosthetic joint infection (defined using the ACS-NSQIP classifications of deep or organ space infection), superficial surgical site infection (SSI), deep vein thrombosis (DVT), pulmonary embolism (PE), pneumonia, urinary tract infection (UTI), renal failure, cerebrovascular accident (CVA), cardiac arrest, myocardial infarction (MI), and bleeding requiring transfusion. Patients were then classified based on whether they experienced any of these 12 complications.

2.3. BMI classifications

Patients were stratified by BMI based on classifications presented by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).15 These included normal weight (BMI 18.5 to <25 kg/m2), overweight (BMI 25 to <30 kg/m2), type 1 obese (BMI 30 to <35 kg/m2), type 2 obese (BMI 35 to <40 kg/m2), and type 3 obese (BMI 40 kg/m2 or higher). Patients within the type 2 and 3 obesity classifications were then grouped by one-point BMI increments, up to BMI 45 kg/m2 for subgroup analysis.

2.4. Study design

Patients were separated based on whether they underwent total hip or knee arthroplasty, and a retrospective, observational cohort study was conducted. Univariate comparison of demographics, surgical characteristics, comorbidities, and patient outcomes was performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and chi-square testing. Multivariate linear and logistic regression was then performed to assess differences in resource utilization and complication rates across BMI categories after controlling for confounding risk factors. Normal weight patients were used as the baseline comparison group for all other BMI classes. Patient demographics, surgical characteristics, and comorbidities that yielded a p-value of <0.1 on univariate comparison were entered into the multivariate regression models for risk adjustment. A subgroup analysis evaluating risk of readmission, return to OR, any complication, and PJI was then conducted using multivariate logistic regression to assess the increased risk associated with one-point BMI increments in type 2 and 3 obese patients after risk adjustment. Type 1 obese patients were used as the baseline for comparison in the subgroup analysis. This group was selected for comparison because our institution considers most type 1 obese patients as eligible candidates for surgery, while high BMI patients (particularly BMI > 40) are typically not considered surgical candidates. All statistical analysis was performed in SPSS version 26 (IBM, Armonk, NY) and R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Statistical significance was assessed at p < 0.05.

3. Results

A total of 299,798 patients undergoing primary THA or TKA from 2016 to 2018 were reviewed. The following patients were excluded: 1648 (0.5%) with no documented BMI, 1384 (0.4%) underweight (BMI <18.5 kg/m2), 641 (0.2%) with disseminated cancer, and 665 (0.2%) with infection at the time of surgery. After exclusions, 295,460 patients (110,382 THA and 185,078 TKA) were included in the study. Across the population, 38,243 patients (12.9%) were normal weight, 86,492 (29.3%) were overweight, 83,505 (28.3%) were type 1 obese, 52,581 (17.8%) were type 2 obese, and 34,639 (11.7%) were type 3 obese.

In patients undergoing THA, significant differences in age, gender, ASA score, use of general anesthesia, smoking status, and all comorbidities except renal failure and dialysis were observed across BMI classes (all p < 0.05). In patients undergoing TKA, the same pattern was observed, with the addition of significant differences in race across BMI classes, and no significant differences in rates of bleeding disorders (Table 1). For both THA and TKA, all demographics, surgical characteristics, and comorbidities other than renal failure and dialysis showed differences across BMI classes at the p < 0.1 significance level and were therefore used as controls for risk adjustment in the multivariate models to isolate the effect of increasing BMI on outcomes.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics, characteristics, and comorbidities of patients undergoing THA and TKA by BMI group.

| Variable | Total Hip Arthroplasty |

Total Knee Arthroplasty |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal Weight n = 21,435 | Over-weight n = 36,823 | Type 1 Obese n = 29,066 | Type 2 Obese n = 15,161 | Type 3 Obese n = 7897 | P-Value | Normal Weight n = 16,808 | Over-weight n = 49,669 | Type 1 Obese n = 54,439 | Type 2 Obese n = 37,420 | Type 3 Obese n = 26,742 | P-Value | |

| BMI (kg/m2) – avg. ± SD | 22.7 ± 1.6 | 27.6 ± 1.4 | 32.3 ± 1.4 | 37.2 ± 1.4 | 43.9 ± 4.2 | <0.001 | 23.1 ± 1.5 | 27.7 ± 1.4 | 32.4 ± 1.4 | 37.3 ± 1.4 | 44.5 ± 4.3 | <0.001 |

| Age (yrs.) – avg. ± SD |

67.5 ± 12.4 | 66.4 ± 11.3 | 64.8 ± 10.6 | 63.0 ± 10.2 | 61.2 ± 9.8 | <0.001 | 70.9 ± 9.8 | 69.3 ± 9.2 | 67.1 ± 8.9 | 65.0 ± 8.6 | 62.5 ± 8.4 | <0.001 |

| Female - % | 69.7 | 50.2 | 48.7 | 52.9 | 59.1 | <0.001 | 69.0 | 54.8 | 57.5 | 64.3 | 72.2 | <0.001 |

| Non-White Race - % | 26.0 | 26.7 | 27.0 | 26.4 | 27.1 | 0.088 | 26.9 | 27.7 | 27.2 | 27.3 | 29.4 | <0.001 |

| ASA - % | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||||

| 1 | 6.3 | 4.8 | 2.4 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 3.8 | 3.1 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 0.3 | ||

| 2 | 57.7 | 58.6 | 53.6 | 40.2 | 20.6 | 59.2 | 58.3 | 52.8 | 41.0 | 20.3 | ||

| 3 | 33.7 | 34.7 | 42.2 | 56.5 | 74.7 | 35.6 | 37.3 | 44.2 | 56.7 | 75.7 | ||

| 4+ | 2.2 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 2.4 | 4.1 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 3.6 | ||

| GA - % | 44.5 | 44.5 | 47.6 | 49.9 | 55.5 | <0.001 | 37.3 | 39.1 | 42.0 | 44.7 | 49.4 | <0.001 |

| Smoker - % | 14.2 | 11.8 | 12.2 | 11.8 | 11.5 | <0.001 | 8.5 | 7.6 | 7.8 | 8.1 | 8.7 | <0.001 |

| Comorbidity - % | ||||||||||||

| Dependent | 2.4 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.8 | 2.4 | <0.001 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.3 | <0.001 |

| Dyspnea | 3.3 | 3.2 | 4.3 | 6.3 | 9.2 | <0.001 | 3.0 | 3.4 | 4.6 | 6.2 | 9.9 | <0.001 |

| COPD | 4.3 | 3.3 | 3.7 | 4.4 | 4.7 | <0.001 | 3.1 | 2.8 | 3.2 | 3.6 | 4.4 | <0.001 |

| CHF | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.002 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.5 | <0.001 |

| HTN | 40.9 | 51.1 | 60.2 | 66.8 | 71.3 | <0.001 | 49.0 | 58.4 | 65.8 | 70.4 | 73.4 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 5.4 | 9.1 | 14.5 | 20.3 | 24.4 | <0.001 | 8.2 | 12.6 | 18.1 | 23.4 | 28.2 | <0.001 |

| Renal Failure | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.278 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.280 |

| Dialysis | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.372 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.654 |

| Steroid Use | 4.5 | 3.7 | 3.3 | 3.5 | 4.0 | <0.001 | 5.0 | 3.5 | 3.2 | 3.4 | 3.4 | <0.001 |

| Bleeding Disorder | 2.2 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 0.002 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 0.093 |

P-values <0.05 in bold.

Normal weight – BMI ≥18.5 to <25.

Overweight – BMI ≥25 to <30.

Type 1 Obese – BMI ≥30 to <35.

Type 2 Obese – BMI ≥35 to <40.

Type 3 Obese – BMI ≥40.

BMI – body mass index.

ASA – American Society of Anesthesiologists Classification.

GA – General anesthesia.

Dependent – partial or total dependent functional status.

Dyspnea – at rest or on mild exertion.

COPD – chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

CHF – congestive heart failure.

HTN – hypertension requiring medication.

Diabetes Mellitus – insulin dependent or non-insulin dependent diabetes.

Univariate comparison of resource utilization and complication rates across BMI classes revealed significant differences in 13 of the 18 endpoints evaluated in THA and in 14 of 18 endpoints in TKA patients. For patients undergoing THA, resource utilization appeared relatively consistent across normal, overweight, and type 1 obese patients, with greater increases in resource utilization rates (particularly readmissions and return to OR) occurring in type 2 and 3 obese patients. The overall complication rate in THA patients was significantly different across BMI classes, with type 3 obese and normal weight patients having the highest complication rates at 7.9% and 7.8%, respectively, while the lowest complication rate of 5.9% was observed in type 1 obese patients. There were statistically significant differences in complication rates for mortality, PJI, superficial SSI, PE, pneumonia, renal failure, and transfusions (all p < 0.05). Notably, both PJI and superficial SSI rates increased in a stepwise fashion as BMI increased (range 0.2% in normal weight patients for both outcomes to 1.6% for type 3 obese PJI and 1.4% for type 3 obese superficial SSI) while transfusion rates decreased from 5.7% in normal weight patients to 3.5% in type 3 obese patients (p < 0.001). In TKA patients, resource utilization was significantly different across BMI classes for all measures. No direct positive relationships between increased BMI and resource utilization were observed, with the exception of longer operative times as BMI increased. For both discharge to SNF and readmissions, the highest rates occurred in type 3 obese patients, with normal weight patients demonstrating the second highest rates. Overall complication rates were highest in the normal weight population (5.1%) and decreased with each BMI class until they reached 3.7% in type 2 obese patients and rose to 4.5% in type 3 obese patients (p < 0.001). For both PJI and superficial SSI, rates increased from 0.2% to 0.4%, respectively, in normal weight patients, and to 0.5% and 0.9% in type 3 obese patients (both p < 0.001). Similar to THA, transfusion rates decreased from 2.4% in normal weight patients to 1.0% in type 3 obese patients (p < 0.001). All resource utilization and complication outcomes are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

30-day postoperative outcomes of patients undergoing THA and TKA by BMI group.

| Outcome | Total Hip Arthroplasty |

Total Knee Arthroplasty |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal Weight n = 21,435 |

Over-weight n = 36,823 |

Type 1 Obese n = 29,066 |

Type 2 Obese n = 15,161 |

Type 3 Obese n = 7897 |

P-Value | Normal Weight n = 16,808 | Over-weight n = 49,669 | Type 1 Obese n = 54,439 | Type 2 Obese n = 37,420 |

Type 3 Obese n = 26,742 |

P-Value | |

| Resource Utilization | ||||||||||||

| Operative Time (min).– avg. ± SD | 87.1 ± 36.7 | 87.9 ± 36.2 | 91.3 ± 36.6 | 95.9 ± 38.8 | 100.8 ± 42.4 | <0.001 | 86.8 ± 34.3 | 88.3 ± 34.3 | 90.1 ± 35.7 | 92.1 ± 36.2 | 93.8 ± 36.6 | <0.001 |

| LOS (days) – avg. ± SD |

2.3 ± 3.2 | 2.1 ± 3.8 | 2.1 ± 3.5 | 2.2 ± 3.4 | 2.5 ± 3.8 | <0.001 | 2.3 ± 3.0 | 2.2 ± 3.3 | 2.2 ± 3.2 | 2.3 ± 3.9 | 2.5 ± 3.2 | <0.001 |

| SNF - % | 16.8 | 12.9 | 12.7 | 14.2 | 19.1 | <0.001 | 16.2 | 13.8 | 13.9 | 15.1 | 19.9 | <0.001 |

| Readmission - % | 3.3 | 2.8 | 3.1 | 4.0 | 5.3 | <0.001 | 3.4 | 2.9 | 3.0 | 2.9 | 3.5 | <0.001 |

| Return to OR - % | 1.6 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 2.6 | 3.6 | <0.001 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.5 | <0.001 |

| Complications - % | ||||||||||||

| Any Complication | 7.8 | 6.0 | 5.9 | 6.7 | 7.9 | <0.001 | 5.1 | 4.2 | 4.0 | 3.7 | 4.5 | <0.001 |

| Mortality | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.050 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.215 |

| PJI | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 1.6 | <0.001 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.5 | <0.001 |

| Superficial SSI | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 1.4 | <0.001 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.9 | <0.001 |

| DVT | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.362 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.012 |

| PE | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.001 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.001 |

| Pneumonia | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.021 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.3 | <0.001 |

| UTI | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.053 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.925 |

| Renal Failure | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.002 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.004 |

| CVA | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.620 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.630 |

| Cardiac Arrest | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.686 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.475 |

| MI | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.833 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.018 |

| Transfusion | 5.7 | 3.8 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 3.5 | <0.001 | 2.4 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.0 | <0.001 |

P-values <0.05 in bold.

Normal weight – BMI ≥18.5 to <25.

Overweight – BMI ≥25 to <30.

Type 1 Obese – BMI ≥30 to <35.

Type 2 Obese – BMI ≥35 to <40.

Type 3 Obese – BMI ≥40.

BMI – Body mass index.

SNF- Skilled nursing facility.

OR – Operating room.

PJI – Periprosthetic joint infection (deep or organ space wound infection).

SSI – Surgical site infection.

DVT – Deep vein thrombosis.

PE – Pulmonary embolism.

UTI – Urinary tract infection.

CVA – Cerebrovascular accident.

MI – Myocardial infarction.

After controlling for confounding factors, THA patients with type 2 and 3 obesity demonstrated higher risk of readmission and return to OR when compared to normal weight patients (both p < 0.001). Risk of any complication was significantly lower for all THA patients overweight or heavier, when compared to normal weight patients (all p < 0.001). However, the risk of PJI and superficial SSI increased with heavier BMIs, reaching over 5 times the risk in type 3 obese patients (PJI OR: 5.381, p < 0.001; Superficial SSI OR: 5.807, p < 0.001). There were significant increases in risk of PE in type 1 and 2 obese, UTI in type 1–3 obese, and renal failure in type 3 obese patients, while significantly lower risk of transfusion was observed in all BMI classes above normal weight (all p < 0.05). In TKA patients, overweight, type 1, and type 2 patients were at increased risk of readmission, and there were no differences in risk of return to OR across BMI classes (all p > 0.05). All TKA BMI classes above normal weight were at decreased risk for any complication (all p < 0.001), with only type 3 obese patients demonstrating increased risk for PJI (OR: 1.775, p = 0.003) or superficial SSI (OR: 1.917, p < 0.001). Significant increases in risk for PE and UTI were observed in type 3 obese patients, while significantly lower risk of transfusion and pneumonia were observed in all BMI classes above normal weight in patients undergoing TKA (all p < 0.05) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Risk adjusted outcomes of overweight and obese patients compared to normal weight patients.

| Total Hip Arthroplasty |

Total Knee Arthroplasty |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome (BMI Group) | Odds Ratio (β where specified) | 95% CI | P-Value | Odds Ratio (β where specified) | 95% CI | P-Value |

| Operative Time (β) | ||||||

| Overweight | −0.342 | −0.965–0.281 | 0.282 | −0.343 | −0.957–0.270 | 0.273 |

| Type 1 Obese | 1.941 | 1.278–2.603 | <0.001 | 0.554 | −0.060–1.168 | 0.077 |

| Type 2 Obese | 5.555 | 4.763–6.346 | <0.001 | 2.092 | 1.434–2.750 | <0.001 |

| Type 3 Obese | 9.243 | 8.251–10.236 | <0.001 | 3.254 | 2.532–3.976 | <0.001 |

| LOS (β) | ||||||

| Overweight | −0.126 | −0.186 to −0.066 | <0.001 | −0.021 | −0.080–0.038 | 0.477 |

| Type 1 Obese | −0.143 | −0.207 to −0.079 | <0.001 | −0.006 | −0.065–0.053 | 0.838 |

| Type 2 Obese | −0.115 | −0.192 to −0.039 | 0.003 | 0.018 | −0.045–0.082 | 0.568 |

| Type 3 Obese | 0.047 | −0.048–0.143 | 0.332 | 0.231 | 0.162–0.301 | <0.001 |

| SNF | ||||||

| Overweight | 0.865 | 0.822–0.911 | <0.001 | 0.958 | 0.911–1.009 | 0.103 |

| Type 1 Obese | 0.888 | 0.840–0.939 | <0.001 | 1.035 | 0.984–1.089 | 0.184 |

| Type 2 Obese | 1.009 | 0.945–1.078 | 0.779 | 1.184 | 1.121–1.250 | <0.001 |

| Type 3 Obese | 1.410 | 1.306–1.523 | <0.001 | 1.717 | 1.621–1.820 | <0.001 |

| Readmission | ||||||

| Overweight | 0.884 | 0.801–0.977 | 0.015 | 0.860 | 0.778–0.950 | 0.003 |

| Type 1 Obese | 0.973 | 0.877–1.079 | 0.602 | 0.859 | 0.777–0.949 | 0.003 |

| Type 2 Obese | 1.198 | 1.066–1.347 | 0.002 | 0.836 | 0.751–0.932 | 0.001 |

| Type 3 Obese | 1.521 | 1.331–1.737 | <0.001 | 0.965 | 0.859–1.083 | 0.542 |

| Return to OR | ||||||

| Overweight | 0.945 | 0.824–1.084 | 0.417 | 0.849 | 0.715–1.008 | 0.062 |

| Type 1 Obese | 1.078 | 0.936–1.242 | 0.295 | 0.883 | 0.745–1.047 | 0.152 |

| Type 2 Obese | 1.568 | 1.346–1.826 | <0.001 | 0.918 | 0.766–1.099 | 0.350 |

| Type 3 Obese | 2.091 | 1.764–2.478 | <0.001 | 1.134 | 0.938–1.371 | 0.193 |

| Any Complication | ||||||

| Overweight | 0.827 | 0.773–0.886 | <0.001 | 0.854 | 0.786–0.928 | <0.001 |

| Type 1 Obese | 0.763 | 0.709–0.821 | <0.001 | 0.790 | 0.727–0.859 | <0.001 |

| Type 2 Obese | 0.774 | 0.710–0.843 | <0.001 | 0.726 | 0.662–0.795 | <0.001 |

| Type 3 Obese | 0.789 | 0.711–0.875 | <0.001 | 0.829 | 0.751–0.914 | <0.001 |

| Mortality | ||||||

| Overweight | 0.637 | 0.343–1.183 | 0.153 | 1.141 | 0.418–3.115 | 0.796 |

| Type 1 Obese | 0.484 | 0.233–1.007 | 0.052 | 0.618 | 0.207–1.842 | 0.388 |

| Type 2 Obese | 0.573 | 0.252–1.304 | 0.185 | 0.899 | 0.295–2.740 | 0.852 |

| Type 3 Obese | 0.622 | 0.236–1.637 | 0.336 | 1.600 | 0.523–4.899 | 0.410 |

| PJI | ||||||

| Overweight | 1.496 | 1.078–2.075 | 0.016 | 0.883 | 0.612–1.273 | 0.504 |

| Type 1 Obese | 1.789 | 1.286–2.489 | 0.001 | 1.083 | 0.758–1.546 | 0.661 |

| Type 2 Obese | 3.082 | 2.202–4.314 | <0.001 | 1.223 | 0.845–1.771 | 0.285 |

| Type 3 Obese | 5.381 | 3.810–7.598 | <0.001 | 1.775 | 1.216–2.591 | 0.003 |

| Superficial SSI | ||||||

| Overweight | 1.680 | 1.210–2.332 | 0.002 | 0.952 | 0.724–1.251 | 0.722 |

| Type 1 Obese | 2.592 | 1.878–3.578 | <0.001 | 1.070 | 0.818–1.400 | 0.622 |

| Type 2 Obese | 3.920 | 2.804–5.481 | <0.001 | 1.103 | 0.831–1.465 | 0.497 |

| Type 3 Obese | 5.807 | 4.082–8.261 | <0.001 | 1.917 | 1.442–2.548 | <0.001 |

| DVT | ||||||

| Overweight | 1.268 | 0.934–1.721 | 0.128 | 0.958 | 0.781–1.175 | 0.682 |

| Type 1 Obese | 1.203 | 0.868–1.666 | 0.267 | 1.020 | 0.832–1.175 | 0.850 |

| Type 2 Obese | 1.388 | 0.960–2.007 | 0.082 | 0.927 | 0.742–1.159 | 0.506 |

| Type 3 Obese | 1.027 | 0.630–1.672 | 0.915 | 0.782 | 0.606–1.009 | 0.059 |

| PE | ||||||

| Overweight | 1.217 | 0.819–1.809 | 0.331 | 1.290 | 0.944–1.763 | 0.109 |

| Type 1 Obese | 1.759 | 1.183–2.614 | 0.005 | 1.773 | 1.308–2.405 | <0.001 |

| Type 2 Obese | 2.310 | 1.498–3.561 | <0.001 | 1.947 | 1.415–2.679 | <0.001 |

| Type 3 Obese | 1.591 | 0.906–2.794 | 0.106 | 1.853 | 1.312–2.618 | <0.001 |

| Pneumonia | ||||||

| Overweight | 0.871 | 0.656–1.157 | 0.341 | 0.612 | 0.460–0.813 | 0.001 |

| Type 1 Obese | 0.695 | 0.505–0.958 | 0.026 | 0.648 | 0.488–0.861 | 0.003 |

| Type 2 Obese | 0.745 | 0.509–1.089 | 0.128 | 0.520 | 0.376–0.718 | <0.001 |

| Type 3 Obese | 0.657 | 0.402–1.0714 | 0.094 | 0.635 | 0.450–0.897 | <0.010 |

| UTI | ||||||

| Overweight | 1.089 | 0.893–1.329 | 0.401 | 1.173 | 0.945–1.456 | 0.147 |

| Type 1 Obese | 1.342 | 1.092–1.649 | 0.005 | 1.186 | 0.954–1.475 | 0.124 |

| Type 2 Obese | 1.481 | 1.167–1.881 | 0.001 | 1.247 | 0.987–1.575 | 0.064 |

| Type 3 Obese | 1.443 | 1.076–1.936 | 0.014 | 1.340 | 1.040–1.727 | 0.023 |

| Renal Failure | ||||||

| Overweight | 1.533 | 0.622–3.774 | 0.353 | 1.131 | 0.421–3.042 | 0.807 |

| Type 1 Obese | 1.932 | 0.773–4.833 | 0.159 | 2.143 | 0.837–5.489 | 0.112 |

| Type 2 Obese | 2.648 | 0.992–7.071 | 0.052 | 1.088 | 0.385–3.072 | 0.873 |

| Type 3 Obese | 4.728 | 1.723–12.974 | 0.003 | 2.160 | 0.779–5.991 | 0.139 |

| CVA | ||||||

| Overweight | 0.974 | 0.579–1.637 | 0.920 | 1.497 | 0.772–2.903 | 0.233 |

| Type 1 Obese | 1.044 | 0.595–1.829 | 0.882 | 1.271 | 0.644–2.509 | 0.490 |

| Type 2 Obese | 1.177 | 0.605–2.288 | 0.631 | 1.343 | 0.649–2.781 | 0.427 |

| Type 3 Obese | 0.591 | 0.198–1.768 | 0.347 | 1.410 | 0.638–3.119 | 0.396 |

| Cardiac Arrest | ||||||

| Overweight | 0.863 | 0.485–1.536 | 0.616 | 1.522 | 0.739–3.136 | 0.255 |

| Type 1 Obese | 1.055 | 0.579–1.923 | 0.862 | 1.130 | 0.537–2.380 | 0.747 |

| Type 2 Obese | 0.675 | 0.299–1.527 | 0.346 | 1.341 | 0.617–2.915 | 0.459 |

| Type 3 Obese | 1.102 | 0.461–2.635 | 0.826 | 1.623 | 0.718–3.670 | 0.244 |

| MI | ||||||

| Overweight | 1.068 | 0.760–1.499 | 0.706 | 0.875 | 0.602–1.270 | 0.482 |

| Type 1 Obese | 1.011 | 0.699–1.462 | 0.952 | 1.032 | 0.712–1.496 | 0.866 |

| Type 2 Obese | 0.856 | 0.539–1.359 | 0.510 | 0.682 | 0.441–1.054 | 0.085 |

| Type 3 Obese | 0.950 | 0.539–1.675 | 0.860 | 0.919 | 0.577–1.462 | 0.721 |

| Transfusion | ||||||

| Overweight | 0.711 | 0.656–0.771 | <0.001 | 0.648 | 0.572–0.735 | <0.001 |

| Type 1 Obese | 0.553 | 0.505–0.606 | <0.001 | 0.419 | 0.366–0.479 | <0.001 |

| Type 2 Obese | 0.444 | 0.396–0.498 | <0.001 | 0.323 | 0.276–0.377 | <0.001 |

| Type 3 Obese | 0.406 | 0.352–0.467 | <0.001 | 0.320 | 0.270–0.380 | <0.001 |

P- Values < 0.05 in bold.

Both THA and TKA risk adjusted for the following patient characteristics (all p < 0.1 on univariate comparison): age, non-white race, gender, ASA Score, general anesthesia, smoker, partial or total functional dependence, dyspnea at rest or on moderate exertion, COPD, CHF, HTN, DM, steroid use, bleeding disorder.

Normal weight – BMI ≥18.5 to <25.

Overweight – BMI ≥25 to <30.

Type 1 Obese – BMI ≥30 to <35.

Type 2 Obese – BMI ≥35 to <40.

Type 3 Obese – BMI ≥40.

BMI – Body mass index.

SNF- Skilled nursing facility.

OR – Operating room.

PJI – Periprosthetic joint infection (deep or organ space wound infection).

SSI – Surgical site infection.

DVT – Deep vein thrombosis.

PE – Pulmonary embolism.

UTI – Urinary tract infection.

CVA – Cerebrovascular accident.

MI – Myocardial infarction.

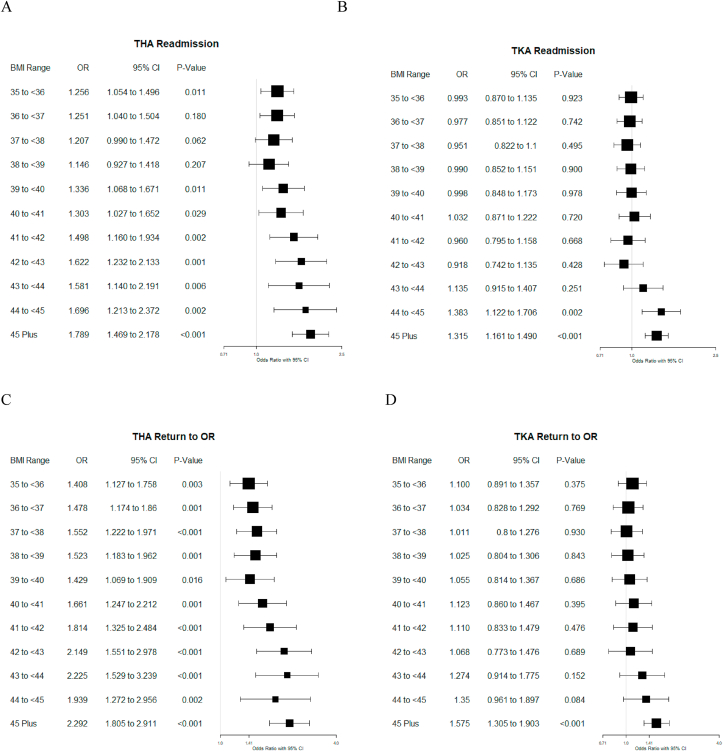

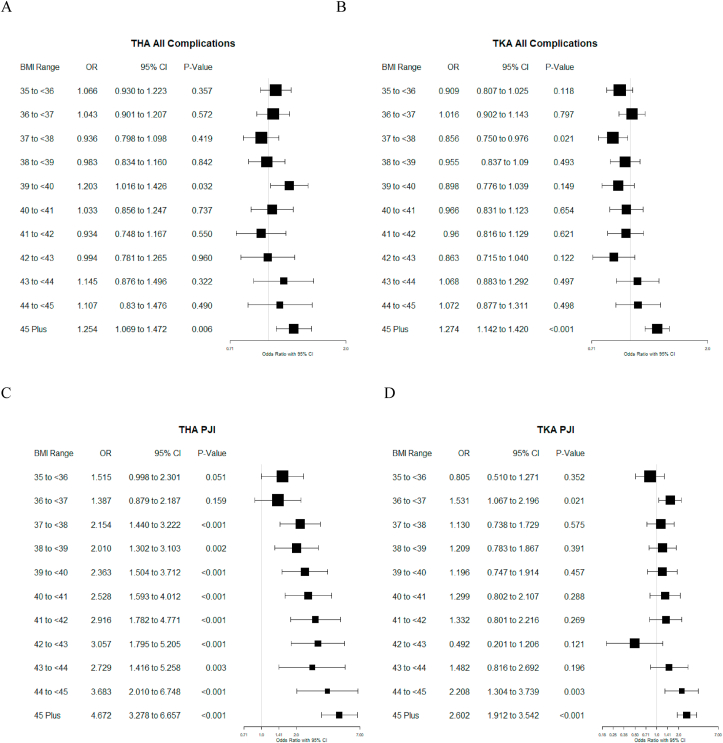

Risk adjusted subgroup analyses comparing risk of readmissions, return to OR, any complication, and PJI between type 1 obese patients and type 2 and 3 obese patients in one-point BMI increments were performed to attempt to identify appropriate BMI cutoffs for surgical candidates, and are presented in Fig. 1, Fig. 2. In comparison to type 1 obese patients, for patients undergoing THA, significant increases in risk for readmission appear to occur at BMI over 39 kg/m2, return to OR at 35 kg/m2, and PJI at 37 kg/m2, while overall risk of any complication does not appear to significantly increase until a BMI of 45 kg/m2, with the exception of the 39–40 kg/m2 group. In patients undergoing TKA, risk of readmission appears to increase at a BMI over 44 kg/m2, risk of return to OR at 45 kg/m2, PJI at 44 kg/m2, and any complication at 45 kg/m2 or higher.

Fig. 1.

Risk Adjusted Forest Plots of Type 2 and 3 Obese Patient Resource Utilization Compared to Type 1 Obese Patients (BMI ≥ 30 to < 35 kg/m2)

The figure depicts the risk of 30-day readmission (A,B) and return to the operating room (C,D) for type 2 and 3 patients undergoing THA and TKA in comparison to type 1 obese patients. Odds ratios are presented in 1-kg/m2 intervals until the 45 plus BMI category. Sample sizes for each one-BMI point classification (top bound only quoted): <36: 12,883; <37: 11,735; <38: 10,634; <39: 9487; <40: 7842; <41: 6869; <42: 5587; <43: 4479; <44: 3463: 45+: 11,187.

Fig. 2.

Risk Adjusted Forest Plots of Type 2 and 3 Obese Patient Complication Rates Compared to Type 1 Obese Patients (BMI ≥ 30 to < 35 kg/m2)

The figure depicts the risk of any complication (A, B) and periprosthetic joint infection (C, D) for type 2 and 3 patients undergoing THA and TKA in comparison to type 1 obese patients. Odds ratios are presented in 1-kg/m2 intervals until the 45 plus BMI category. Sample sizes for each one-BMI point classification (top bound only quoted): <36: 12,883; <37: 11,735; <38: 10,634; <39: 9487; <40: 7842; <41: 6869; <42: 5587; <43: 4479; <44: 3463: 45+: 11,187.

4. Discussion

Our findings demonstrate an increased risk of a variety of postoperative complications for obese patients undergoing TJA, which can impact not only the physical recovery process but also adversely impact quality of life. Further, resource utilization measured by length of stay, readmission, return to OR, and operative time increases with elevated BMI. Beyond the direct adverse effect on patient outcomes, this change in resource utilization translates to an increased cost of care for obese patients. There have been many studies investigating the connection between risk of postoperative complications and BMI, however to our knowledge this is the first study to evaluate risk in the type 2 and 3 obese populations in granular, one-BMI point increments. These results may guide surgeons in selecting patients to operate on based on their risk tolerance, and in counseling patients as to the risks involved in undergoing surgery.

Multiple studies have established obesity as an independent risk factor for various post-operative complications.16, 17, 18 Infection, both periprosthetic and superficial, is associated with elevated BMI in both TKA and THA patients. Zusmanovich et al.7 stratified 268,663 patients from the 2008–2015 ACS-NSQIP database by BMI to examine rates of complications following TJA. Both TKA and THA patients with a BMI >40 kg/m2 demonstrated significantly increased rates of superficial and deep infections compared to patients classified as normal weight. There was also a significantly increased risk of developing infection for THA patients classified as class 1 and class 2 obese. Similar trends emerged for TKA patients, however, the results were not significant. While this study demonstrated a trend of increasing infection with increasing BMI, they did not further stratify patients with a BMI> 40 to determine a more exact cutoff point for significantly increased risk of complications. In a similar study, Pugely et al.19 analyzed 25,235 patients from the 2005–2010 ACS-NSQIP database who underwent TJA, however, this study included both primary and revision surgeries. On multivariate analysis, patient BMI, especially >40 kg/m2, was a risk factor for 30-day surgical site infection for both primary and revision THA and TKA. Our findings are similar to both of these studies in that we found both PJI and superficial SSI rates increased in a stepwise fashion as BMI increased on univariate analysis. However, after controlling for potentially confounding comorbidities this trend existed only in THA patients, with TKA patients demonstrating similar levels of risk for both PJI and superficial SSI until the type 3 obese cutoff. A strength of our study is the use of more recent ACS-NSQIP data (2016–2018), and our stratification of BMI into smaller categories to pinpoint a more exact measurement of increased risk of postoperative complications. In comparison to type 1 obese patients, who are commonly considered as appropriate surgical candidates, we demonstrated significant increases in risk of PJI for primary THA patients at 37 kg/m2 and at 44 kg/m2 for primary TKA patients. Independent risk factors for infection such as diabetes and smoking status were controlled for in our multivariate analysis.20, 21, 22, 23

Similar to previous findings, our study found a decreased rate of transfusions for patients with a higher BMI.24,25 Walsh et al.25 showed a 46% decrease in the risk of transfusion in patients with an elevated BMI who underwent THA, while Frisch et al.24 showed a significantly reduced rate of transfusions in patients who underwent TKA with an elevated BMI. The transfusion rate decreased from 17.3% for normal, 11.4% for overweight, and 8.3% for obese patients. Although our overall transfusion rates were lower than both of these studies, the overall trend of reduced transfusion risk in BMI categories above normal for patient undergoing THA or TKA remained consistent. Elevated BMI has been correlated with increased estimated blood loss (EBL) which could be explained by the longer operative time or increased thickness of soft tissue causing increased bleeding during initial dissection.24 Despite the increased EBL, the protective effect of BMI on risk of transfusion may be related to the increased estimated blood volume (EBV) associated with an increased BMI. According to Frisch et al.24 the increased EBV in obese patients allows for a lower final percentage of EBV lost during surgery which accounts for the decreased risk of transfusion.

Given the trend towards value-based payment models, evaluation of the impact of obesity on complications after TJA is essential to maximize the economic value of these procedures. While bundled payment models are designed to enhance the quality of patient care while controlling cost, increased resource utilization through extended hospital stays and complications are cost drivers that can be influenced by appropriate patient selection.26 Doran et al.26 demonstrated how cost of TJA could be mitigated through reductions in LOS and readmission rates. While direct economic analysis was outside the scope of our study, the positive relationship between increasing LOS and BMI observed in our population suggests high-BMI patients are at risk for incurring additional acute care costs after surgery. In addition, heavier patients in our study had increased rates of return to the OR, infection, and longer operative times—all factors that have been previously demonstrated to lead to increased cost.27 Finally, in our patient population, increasing BMI was associated with increased rate of readmission for both TKA and THA patients which is a common driver of elevated episodic cost.28,29 The significant impact of readmissions on the value of TJA is demonstrated by cost estimates of $22,775 and $11,682 for medically related readmission of THA and TKA patients, respectively, while readmission for surgical complications cost $36,038 for THA and $27,979 for TKA.28 The significant costs associated with increased resource utilization, and the link between BMI and these cost drivers further necessitates identification of appropriate surgical candidates from a societal perspective.

A BMI of 40 kg/m2 is a commonly cited threshold for safe performance of TJA, however few studies have proposed separate points for TKA and THA based on relative risks associated with each procedure.30,31 Demik et al.9 compared the effect of the magnitude of obesity on post-operative outcomes for both procedures using 64,648 THA and 97,137 TKA patients from the 2010–2014 ACS-NSQIP database. The THA cohort had significantly higher rates of wound complications, deep infection, reoperation rate, and total complications when compared with obese TKA patients. These trends remained consistent for morbidly obese patients. In addition, the study was able to conclude a stepwise increase in the odds of each outcome measure as BMI increased for both procedure cohorts. Similarly, while we did not directly compare THA and TKA patients, our findings indicated a difference in the effect of BMI on complication rates following each procedure. In THA patients, when compared to type 1 obese patients, we observed significant increases in risk for key resource utilization measures and PJI at BMIs over 35 kg/m2, suggesting that both type 2 and 3 obese patients present an increased risk profile. Conversely, TKA patients had a significant increase in risk for these complications at BMIs over 44 kg/m2, suggesting that a strict BMI cutoff of 40 kg/m2 may limit access to surgery for some type 3 obese patients at similar risk to those commonly considered appropriate surgical candidates.

BMI cutoffs for performance of TJA is are commonly used to recommend surgery or nonoperative treatment for patients struggling with advanced knee or hip osteoarthritis. It is of the upmost importance to strike a balance between mitigating risk of post-operative complications and providing treatment that will improving quality of life for patients suffering from the debilitating pain associated with this condition. Preoperative weight loss is commonly recommended for obese patients with advanced osteoarthritis, however the impact of postponing TJA is not well studied. Springer et al.12 prospectively studied 289 morbidly obese patients with end-stage osteoarthritis and a mean BMI of 46.9 kg/m2. All patients received education about the risk of TJA with morbid obesity and were referred to a bariatric clinic to pursue medically managed weight loss. The majority of the patients in the cohort were unable to achieve a BMI <40 kg/m2 and did not undergo TJA. Additionally, 29% of the patients became disengaged with the program and had no further follow-up appointments and refused surveys or phone calls relating to their attempted weight loss. The researchers concluded that restricting TJA for morbidly obese patients did not incentivize weight loss prior to surgery. This study highlights the need for additional resources and coordinated care designed to help obese patients with advanced osteoarthritis achieve their weight loss goals and gain access to surgery. This care should be guided by an understanding of the risks of complications associated with increasing BMI. However, our findings suggest these risks may be lower for patients undergoing TKA at high BMI levels, and may expand access to patients not previously considered to be surgical candidates.

The ACS-NSQIP database only measures thirty-day postoperative outcomes making it difficult to assess the long-term negative consequences of obesity on recovery from TJA. There have been very few studies to investigate this long-term relationship.32,33 Jones et al.32 conducted a prospective observational study of 520 patients who underwent primary TJA analyzing six month and three year functional outcomes measured by the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities (WOMAC) Osteoarthritis Index. The cohort was divided into four BMI classifications; normal (<25.0 kg/m2); overweight (25.0–29.9 kg/m2); obese Class 1 (30.0–34.9 kg/m2); and severe obese Class 2&3 (>35.0 kg/m2). Baseline pain and functional scores were similar across all groups. At the six-month postoperative mark, severely obese patients reported worse pain and functional outcomes, however there were no significant differences between groups in these outcomes at the three year follow-up. Although these findings indicate no relationship between BMI and long-term postoperative outcomes, further research is required to determine the impact of obesity on additional long-term outcomes such as rate of revision and time to revision compared across BMI classifications.

The main limitation of our study is the retrospective nature of the data and that only hospitals participating in the ACS-NSQIP program are included, which may not be a representative sample of all TJAs performed nationally. Since this database is not orthopedic specific, it does not directly measure some variables of interest such as peri-prosthetic joint infection. We used composite metrics to analyze this variable and included deep infection and organ space infection as a surrogate for PJI. An additional limitation of the study design is the inability to analyze functional outcomes or patient reported outcomes, which prevents us from commenting on the long term positive gains of surgical intervention. Despite the limitations of the ACS-NSQIP database, its large sample size derived from multiple sites enables examination of relatively infrequent complications after TJA.

5. Conclusion

In comparison to normal weight patients, overweight and obese patients undergoing TJA were at risk for increased resource utilization and various early complications. Patients undergoing TKA with a BMI up to 45 kg/m2 are at similar risk for 30-day postoperative complications when compared to type 1 obese patients. Patient selection must continue to be tailored to the individual, and further evaluation of the impact of BMI on patient reported outcomes and physical function in this population is required.

Footnotes

All work performed at Anne Arundel Medical Center.

References

- 1.Ng M., Fleming T., Robinson M. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384(9945):766–781. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang Y., Beydoun M.A., Liang L., Caballero B., Kumanyika S.K. Will all Americans become overweight or obese? estimating the progression and cost of the US obesity epidemic. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16(10):2323–2330. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Francisco V., Pérez T., Pino J. Biomechanics, obesity, and osteoarthritis. The role of adipokines: when the levee breaks. J Orthop Res. 2018;36(2):594–604. doi: 10.1002/jor.23788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grotle M., Hagen K.B., Natvig B., Dahl F.A., Kvien T.K. Obesity and osteoarthritis in knee, hip and/or hand: an epidemiological study in the general population with 10 years follow-up. BMC Muscoskel Disord. 2008;9:132. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-9-132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reyes C., Leyland K.M., Peat G., Cooper C., Arden N.K., Prieto-Alhambra D. Association between overweight and obesity and risk of clinically diagnosed knee, hip, and hand osteoarthritis: a population-based cohort study. Arthritis Rheum. 2016;68(8):1869–1875. doi: 10.1002/art.39707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kurtz S., Ong K., Lau E., Mowat F., Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(4):780–785. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zusmanovich M., Kester B.S., Schwarzkopf R. Postoperative complications of total joint arthroplasty in obese patients stratified by BMI. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(3):856–864. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.09.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.George J., Piuzzi N.S., Ng M., Sodhi N., Khlopas A.A., Mont M.A. Association between body mass index and thirty-day complications after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(3):865–871. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeMik D.E., Bedard N.A., Dowdle S.B. Complications and obesity in arthroplasty-A hip is not a knee. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(10):3281–3287. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2018.02.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roth A., Khlopas A., George J. The effect of body mass index on 30-day complications after revision total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34(7s):S242–s248. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2019.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suleiman L.I., Ortega G., Ong'uti S.K. Does BMI affect perioperative complications following total knee and hip arthroplasty? J Surg Res. 2012;174(1):7–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2011.05.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Springer B.D., Roberts K.M., Bossi K.L., Odum S.M., Voellinger D.C. What are the implications of withholding total joint arthroplasty in the morbidly obese? A prospective, observational study. Bone Joint Lett J. 2019;101-b(7_Supple_C):28–32. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.101B7.BJJ-2018-1465.R1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Surgeons ACo . 2018. User Guide for the 2018 ACS NSQIP Participant Use Data File American College of Surgeons American College of Surgeons Web Site.https://www.facs.org/-/media/files/quality-programs/nsqip/nsqip_puf_userguide_2018.ashx Accessed. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ingraham A.M., Richards K.E., Hall B.L., Ko C.Y. Quality improvement in surgery: the American College of surgeons national surgical quality improvement program approach. Adv Surg. 2010;44:251–267. doi: 10.1016/j.yasu.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . 2020. Defining Adult Obesity Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/adult/defining.html Accessed2020. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Friedman R.J., Hess S., Berkowitz S.D., Homering M. Complication rates after hip or knee arthroplasty in morbidly obese patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(10):3358–3366. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-3049-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deakin A.H., Iyayi-Igbinovia A., Love G.J. A comparison of outcomes in morbidly obese, obese and non-obese patients undergoing primary total knee and total hip arthroplasty. Surgeon. 2018;16(1):40–45. doi: 10.1016/j.surge.2016.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wagner E.R., Kamath A.F., Fruth K., Harmsen W.S., Berry D.J. Effect of body mass index on reoperation and complications after total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98(24):2052–2060. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.16.00093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pugely A.J., Martin C.T., Gao Y., Schweizer M.L., Callaghan J.J. The incidence of and risk factors for 30-day surgical site infections following primary and revision total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(9 Suppl):47–50. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2015.01.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Namba R.S., Paxton L., Fithian D.C., Stone M.L. Obesity and perioperative morbidity in total hip and total knee arthroplasty patients. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20(7 Suppl 3):46–50. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2005.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dowsey M.M., Choong P.F. Obese diabetic patients are at substantial risk for deep infection after primary TKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467(6):1577–1581. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0551-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jämsen E., Nevalainen P., Eskelinen A., Huotari K., Kalliovalkama J., Moilanen T. Obesity, diabetes, and preoperative hyperglycemia as predictors of periprosthetic joint infection: a single-center analysis of 7181 primary hip and knee replacements for osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(14) doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liabaud B., Patrick D.A., Geller J.A. Higher body mass index leads to longer operative time in total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(4):563–565. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2012.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frisch N., Wessell N.M., Charters M. Effect of body mass index on blood transfusion in total hip and knee arthroplasty. Orthopedics. 2016;39(5):e844–849. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20160509-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walsh M., Preston C., Bong M., Patel V., Di Cesare P.E. Relative risk factors for requirement of blood transfusion after total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22(8):1162–1167. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2006.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Doran J.P., Zabinski S.J. Bundled payment initiatives for Medicare and non-Medicare total joint arthroplasty patients at a community hospital: bundles in the real world. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(3):353–355. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2015.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peel T.N., Cheng A.C., Liew D. Direct hospital cost determinants following hip and knee arthroplasty. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2015;67(6):782–790. doi: 10.1002/acr.22523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clair A.J., Evangelista P.J., Lajam C.M., Slover J.D., Bosco J.A., Iorio R. Cost analysis of total joint arthroplasty readmissions in a bundled payment care improvement initiative. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(9):1862–1865. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2016.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kurtz S.M., Lau E.C., Ong K.L., Adler E.M., Kolisek F.R., Manley M.T. Which clinical and patient factors influence the national economic burden of hospital readmissions after total joint arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2017;475(12):2926–2937. doi: 10.1007/s11999-017-5244-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ward D.T., Metz L.N., Horst P.K., Kim H.T., Kuo A.C. Complications of morbid obesity in total joint arthroplasty: risk stratification based on BMI. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(9 Suppl):42–46. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2015.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Foreman C.W., Callaghan J.J., Brown T.S., Elkins J.M., Otero J.E. Total joint arthroplasty in the morbidly obese: how body mass index ≥40 influences patient retention, treatment decisions, and treatment outcomes. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35(1):39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2019.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones C.A., Cox V., Jhangri G.S., Suarez-Almazor M.E. Delineating the impact of obesity and its relationship on recovery after total joint arthroplasties. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2012;20(6):511–518. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2012.02.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yeung E., Jackson M., Sexton S., Walter W., Zicat B., Walter W. The effect of obesity on the outcome of hip and knee arthroplasty. Int Orthop. 2011;35(6):929–934. doi: 10.1007/s00264-010-1051-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]