Abstract

Due to the current lack of innovative and effective therapeutic approaches, tissue engineering (TE) has attracted much attention during the last decades providing new hopes for the treatment of several degenerative disorders. Tissue engineering is a complex procedure, which includes processes of decellularization and recellularization of biological tissues or functionalization of artificial scaffolds by active cells. In this review, we have first discussed those conventional steps, which have led to great advancements during the last several years. Moreover, we have paid special attention to the new methods of post-decellularization that can significantly ameliorate the efficiency of decellularized cartilage extracellular matrix (ECM) for the treatment of osteoarthritis (OA). We propose a series of post-decellularization procedures to overcome the current shortcomings such as low mechanical strength and poor bioactivity to improve decellularized ECM scaffold towards much more efficient and higher integration.

Keywords: Cartilage tissue engineering, osteoarthritis, decellularized extracellular matrix, post-decellularization

Introduction

Extracellular matrix (ECM) is the non-cellular component present within all tissues and organs. It provides the essential physical scaffold for the cellular constituents and initiates crucial biochemical and biomechanical signals that are required for tissue morphogenesis, differentiation and homeostasis.1 Cartilage is a hyalin and an avascular tissue that consists of an extensive ECM (about 95% such as proteoglycans, glycoproteins, enzymes, communication peptides, and water) that is produced and maintained by chondrocytes (about 5%).1 Cartilage matrix is composed predominantly of proteoglycans, which are made of a core protein bound to multiple chains of glycosaminoglycans (GAG), such as chondroitin sulfate (CS) and keratan sulfate (KS).2 The large aggregating proteoglycan, aggrecan (ACAN), can bind or aggregate to a backbone of hyaluronic acid (HA) forming larger macromolecules.3 Together, these components help to retain water within the ECM, which is critical to maintain its unique mechanical properties.4 Due to the absence of blood vessels and nerves, healthy adult joints cartilage does not have the ability to self-repair leading to degenerative joint disorders like OA. In this setting, because of the concurrent changes in matrix composition with increasing calcification, the cartilage progressive destruction happens.5 Unfortunately, there is no current consensus regarding the ideal treatment to stop gradual loss of articular cartilage resulting in osteoarthritis (OA).5 However, several treatment methods have been proposed with the aims of pain relief and improvement of patients’ movement abilities. Current treatments are pharmacological methods such as oral, intra-articular injections based on HA and CS and non-pharmacological treatments such as immunotherapy, gene therapy, cellular therapy and eventually surgical interventions. As cartilage ECM is maintained specifically by chondrocytes, their low cell density and avascular properties leads to low cartilage regeneration capacity. Therefore, tissue engineering is considered a promising approach for effective repair of damaged cartilage tissue.6,7 Most often, the procedure used in cartilage tissue engineering involves a suitable combination of seeded cells, a biocompatible scaffold, and biological factors that support cartilage formation.8 The excised tissue must first be decellularized, a process in which the ECM is depleted from its native cells and genetic materials (such as DNA and RNA found in the nucleus, mitochondria, and cytoplasm) to produce a natural scaffold. The ECM, that ideally retains its indispensable structural, biochemical and biomechanical cues, can then be recellularized to produce a functional tissue or organ.

Even though many articles on decellularization of cartilage for tissue engineering purposes have been already published, this is the first comprehensive review that particularly focuses on cartilage post-decellularization methods. In this review, the methods of decellularization have been sorted into three categories: biological, chemical, and physical. In addition, a summary of cartilage decellularzation protocols progressed during several years is also presented. We have summarized different materials and methods concerning the post-decellularization methods that can significantly improve the efficiency of decellularized cartilage ECM. Recellularization is the final step, in which the role of different cell types including stem cells in order to repopulate the acellular ECM scaffolds of cartilage has been discussed. Moreover, a summary of cartilage recellularzation protocoles evolved during the last years has been provided.

Tissue engineering

Tissue engineering aims at replacing or regenerating human tissues or organs in order to renovate or re-establish their normal function. There are three principle axes in the process of tissue engineering: (1) a scaffold that provides structure and substrate for tissue growth and development, (2) cells to improve required tissue formation, (3) growth factors (GFs) or biophysical stimuli to direct the growth and differentiation of cells within the scaffold. Together, these components create what is known as the tissue engineering triad. Although these factors are separately important, understanding their interactions is also crucial for successful tissue engineering.

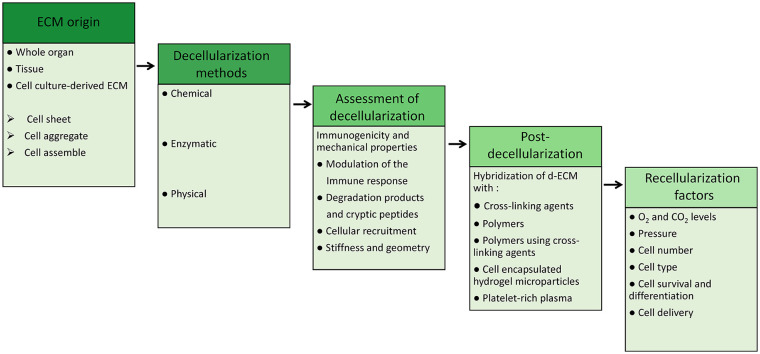

Here, we focus on natural ECM as a scaffold that maintains its original 3D architecture for culturing cells or as a mold for organs. To produce ECM scaffolds, tissue must first be decellularized which is obtained by removing the cells and their genetic materials. Therefore, decellularized ECM (dECM) is expected to be an effective scaffold that has suitable components for the construction of tissues. Compared to other methods that completely destroy the ECM, using it as a natural scaffold maintaining most of its original ECM architecture would be a great advantage. In order to improve the decellularization efficiency, several recent studies suggest a complementary post-decellularization process which will be further discussed in detail. These steps will be finalized via recellularization methods. A summarized procedure is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Summary of ECM based tissue engineering procedure. This figure depicts the succession of different steps including the origin of ECM, decellularization methods, and their efficacy assessment; post-decellularization methods, and finally recellularization factor that are essential in an appropriate ECM-based tissue engineering procedure.

Decellularization

Different kinds of ECM sources such as tissue, whole organ and cell-culture derived ECM have been investigated in research works. Besides, macromolecular crowding (MMC) which is the addition of inert polydispersed macromolecules has been shown effective for the amplification of ECM deposition in vitro and the production of ECM-rich alternatives.9,10 Decellularization is the procedure to maximally remove all cellular and genetic materials from a desired ECM while maintaining its physical structural, biochemical and biomechanical properties including thickness, stiffness, density and 3D configuration.11 During the past decade different human and animal organs and tissues have been utilized as dECM scaffolds, proving their potential application in tissue engineering (Table 1). The progression of decellularization techniques has been advancing for different tissue and organs like heart,12–15 liver,16,17 lung,18–21 kidney,22,23 cornea,24,25 skin,26,27 brain,28 adipose tissue.29

Table 1.

Timeline of decellularization techniques progression during years.

| Years | Tissue origin | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1948 | Muscle samples | Pulverization of tissue samples and preparing acellular homogenates of though tissues.30 |

| 1975 | Bovine blood vessel | Solubilizing blood vessels with 4% SD.31 |

| Rabbit/rat renal tubules | Solubilizing renal tubules with 4% SD.31 | |

| 1980 | Rat liver | Long-term Culture of normal rat hepatocytes on decellularized rat liver ECM.32 |

| 1995 | Porcine-SIS | Using an acellular porcine-SIS, as temporary bioscaffold for treating Achilles tendon defect in the dog. SIS remodeled neotendon and after 8 weeks became degraded.33 |

| 1996 | Cadaveric allograft skin | Acellular allograft dermal matrix used as scaffold and grafted to the excised wound base. After 14 days, neovascularization, neoepithelialization and infiltration were observed.26 |

| 1999 | Cultured BCE-cells and PF-HR9 endodermal cells | Produce decellularized ECMs by culturing BCE and PF-HR9 endodermal cells. ECM coating on plastic surface was uniform and suitable for HS703T human colon carcinoma cells attachment and spreading.24 |

| 2000 | Human and sheep pulmonary valves | Human and sheep pulmonary valves decellularization using the SynerGraft treatment process and implantation in the right ventricular outflow tract of growing sheep. Human pulmonary valves were implanted in human. They became recellularized with recipient cells without provoking antibody response.18 |

| 2001 | Porcine aortic valves | Porcine aortic valves recellularization by human neonatal fibroblasts cells in a novel bioreactor resulted in a heart valve populated with viable human cells.35 |

| 2004 | Porcine dermal matrix | Decellularization of the porcine dermal matrix using trypsin and SDS. Cell component was completely removed.34 |

| 2004 | Peripheral nerve tissue | Decellularization of peripheral nerve tissue with Triton X-200, sulfobetaine-10/16 was suited for studying specific aspect of nerve regeneration.36 |

| 2005 |

Bovine pericardium |

Decellularization of the bovine pericardium with triton-x, SD, SDS, and PLA2, which resulted in removal of xenogeneic antigens.37 |

| 2005 | Porcine small bowel | Decellularization of porcine small bowel segments using mechanical, chemical and enzymatic methods. Implantation of tissue in a porcine model after recellularization and vascularization.38 |

| 2006 | Human placenta | Decellularization of human placenta ECM through perfusion via the existing vasculature. An intact vascular network of ECM architecture was preserved.39 |

| 2007 | Chicken tendon | Combining decellularization and chemical oxidation to decellularize chicken Tendon.40 |

| Bone marrow cell-derived ECM | Culturing MSCs on bone marrow cell-derived ECM which perfectly promoted replication and expansion of MSCs.42 | |

| 2008 | Porcine urinary bladder | Enzymatic solubilization of porcine urinary bladder to prepare an Injectable gel form of ECM for culturing smooth muscle cells.41 |

| Rat heart | Rat heart decellularization by coronary detergent perfusion to preserve an acellular and intact matrix with perfusable vascular architecture. Recellularization with cardiac or endothelial cells.14 | |

| 2009 | Yorkshire boar Trachea tubular | Yorkshire boar Trachea tubular decellularization using detergent-enzymatic method and implantation into mice. It was mechanically and structurally comparable to the native ECM with no immune response in animal models.43 |

| Porcine cornea | Decellularization of porcine cornea by ultrahigh hydrostatic pressure method and implantation into rabbit that was successfully a possible corneal scaffold for an artificial cornea.25 | |

| 2010 | Rat liver | Generation of a transplantable rat liver graft by decellularization via portal perfusion with SDS and recellularization of liver matrix with adult hepatocytes.16 |

| 2013 | Pig and human trachea-lung |

Decellularization of pig and human trachea-lung using freezing and SDS washes. Recellularization of scaffold with human adult primary alveolar epithelial type II cells supported cell attachment and cell viability.44 |

| Human kidney | Decellularization of human kidney with SDS in order to obtain human renal ECM scaffold.45 | |

| 2014 | Heart, cartilage and adipose cell-laden ECM | Using decellularized heart, cartilage and adipose cell-laden ECM as a bioink for 3D printing scaffold.46 |

| Tumor tissues | Decellularization of tumor tissues for modeling tumor microenvironment. A549 human pulmonary adenocarcinoma cells implanted into mice were used for decellularization.47 | |

| Human and rat whole-lung | Decellularization of human and rat whole-lung scaffold by perfusion with SDS and recellularization with iPSCs.20 | |

| 2015 | Rat and human lungs | Decellularization of rat and human lungs and Repopulating vascular compartment for regeneration of functional pulmonary vasculature.21 |

| 2015 | Human liver | Decellularization of human liver and repopulation with human hepatic stellate cells (LX2), hepatocellular carcinoma (Sk-Hep-1) and hepatoblastoma (HepG2).48 |

| 2016 | Human heart | Human heart perfusion-decellularization and recellularization with myocytes derived from human iPSCs.13 |

| 2017 | Cardiac tissue | Cardiac tissue regeneration using hCPCs cell-laden dECM bioinks for 3D printing scaffold. Stem cell patch induced vascularization and tissue matrix formation in vivo.12 |

| 2018 | Human brain | Human brain dECM 3D hydrogel facilitates the direct conversion of fibroblasts into induced neuronal cells.28 |

| 2020 | Human liver | Revascularization of decellularized liver scaffold with human umbilical vein endothelial cells HUVECs using perfusion bioreactor culture and implanation into pig.17 |

SD: sodium deoxycholate; ECM: extracellular matrix; SIS: small intestinal submucosa; BCE: bovine corneal endothelial-cell; SDS: sodium dodecyl sulfate, PLA: poly-L-lactic acid; iPSCs: induced pluripotent stem cells; 3D: three dimension; hCPCs: human cardiac progenitor cells; dECM: decellularized ECM.

Decellularization has been performed through chemical, physical, and enzymatic techniques.49 The chemical decellularization methods function by immersing the tissue in a solution containing an acid, alkaline base, alcohol, chelating agent, or detergents. Common acids include peracetic acid and acetic acid which has been shown to disrupt mainly nucleic acids,50 sodium, calcium, and ammonium hydroxide that destroy cellular and nuclear components and induce cellular lysis.51–54 Alcohols such as methanol and ethanol are suggested to use for removal of lipids.49,55 In addition, it has been reported that alcohols disrupt the actin cytoskeleton network which further contributes to cell detachment by breaking interactions with focal adhesions.56 Chelating agents like Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) and Egtazic acid (EGTA) are used with enzymes or detergents to improve cell nuclei removal.53,57 However, these agents can inhibit DNase activity which would reduce the digestion of nucleic acids that is an important step in decellularization process.58 On the other hand, EDTA application promotes cell detachment by reducing cell-matrix and cell-cell adhesion through the chelation of extracellular Ca2+ ions that are necessary for the activation of Ca2+ dependent cell adhesion molecules such as integrins and cadherins.59 Detergents such as sodium deoxycholate (SD) and sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) are used to lyse cell membrane, to solubilize membrane proteins and lipids and also to remove cytosolic and genomic material.11,60 Enzymatic methods are mainly based on the use of proteases (trypsin, collagenase, thermolysin, and dispase) in addition to other enzymes such as lipase acting mostly by cleaving adhesive proteins like collagens and fibronectin, and cell edhesion molecules like integrins and cadherins11,61,62 while others like nucleases (DNase and RNase) digest nucleic acids.49,50

Decellularization protocols also often include a physical decellularization step such as mechanical agitation,63,64 freeze/thaw cycles,65,66 hydrostatic pressure,67 osmotic pressure,68 perfusion/ pressure gradients or exposure to supercritical carbon dioxide (CO2). A summary of various decellularization techniques with their advantages and drawbacks is listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Methods of tissue, organ, and cell-derived ECM decellularization.

| Techniques | Agents | Advantage | Disadvantage | Organ Decellularization | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.Chemical 1.1 Acids |

• Peracetic acid • Acetic acid |

• Disrupting nucleic acids • Removing cytoplasmic components • Used as a disinfectant • Produce a biocompatible scaffold |

• Damage the ECM microarchitecture • Reducing the collagen content • Decrease the tissue tensile strength and elasticity • Alteration of mechanical properties of ECM • Not efficient in cell component removal |

SIS, urinary bladder | Syed et al.69, Gilbert et al.70 and Yamanaka et al.71 |

| 1.2 Alkaline base | • Sodium hydroxide • Calcium hydroxide • Ammonium hydroxide • Sodium sulfide |

• Destroy cellular and nuclear components • Denaturation of the DNA |

• Eliminate growth factors • Decrease ECM stiffness • Degrading collagen fibrils and collagen crosslinks • Change the structure, biomechanical and viscoelastic properties of ECM |

Kidney | Zambon et al.72 |

| 1.3 Alcohol | • Ethanol • Methanol |

• Disinfectant agent • lysing cells and removing nucleic acids and lipids • Adjuvant to remove phospholipids |

Change the collagen 3D structure by crosslinking the ECM | Adipose tissue and cornea | Flynn73 and Du et al.74 |

| 1.4 Chelating agents | • EDTA • EGTA |

• Undermine cell adhesion • Improve the efficacy of cell nuclei content removal |

Undermine cell adhesion causing cell and ECM dissociation | Heart, kidney, liver, and pancreas | Seo et al.,75 Song et al.,76 Kajbafzadeh et al.,77 Mirmalek-Sani et al.78 |

| 1.5 Detergents | I. Ionic detergents • SDS |

• Disrupts the lipid and protein interactions • Lyses cells • Solubilize membrane proteins and lipids • Control protein crystallization • Efficiently cell component remove |

Removes GAGs, GFs, and ECM proteins • Leaves behind residual surfactant • Carcinogenic and cytotoxicity effect • Requires extensive wash process • Disrupts the triple-helical collagen structure • Causes swelling of the elastin network |

Porcine cornea, myocardium, heart valve/small intestine, kidney, human vein, heart, kidney, porcine, human lungs | Pang et al.,79 Wang et al.,80 Zhou et al.,81 Syed et al.,69 Sullivan et al.82, Schaner et al.,83 and Guyette et al.13 |

| • SD | • Denatures the protein interaction • Removal of cellular contents • Non damaging to the ECM |

Agglutination of DNA on the tissue’s surface • Requires washing to reduce immune response • Less harsh and damaging than SDS |

Blood vessels, tracheas, diaphragm, aortic root, and small intestines | Syed et al.,69 Pellegata et al.,84 Baiguera et al.,85 Piccoli et al.,86 and Friedrich et al.87 | |

| • Sodium • N-lauroyl glutamate |

• Short elution time • Retaining the ultrastructure, transparency, and mechanical properties |

• Causing dehydration • Low cell removal alone |

Porcine corneal stromal | Dong et al.88 | |

| II. Zwitterionic detergents • CHAPS |

• Intermediate potency • Greater preservation of ECM Better cell removal efficiency • Non-denaturing agent • Ionic and nonionic detergent |

• Useful for thin tissues • Works at a balanced pH • Less ECM disruption than SDS • Less effect on growth factors • Less cell component removal than SDS |

Human and porcine lung, Oesophagus | Gilpin et al.,89, Syed et al.,69 and O’Neill et al.90 | |

| III. Non-ionic detergents • • Triton X-100 |

• Denature the protein interactions • Used in combination with other detergents • Breaking up lipid-lipid and lipid-protein association |

• Less ECM disruption than SDS • High viscosity • Less cell component removal than SDS |

Fibrosis, livers, kidneys and aortic valves | Zambon et al.,72 Xu et al.,91 Ren et al.,92 and Meyer et al.,93 | |

| • Trypsin | • Disrupts the DNA, protein and interactions • High viscosity, no toxicity, and less harmful to ECM • Eliminates cellular contents from thick tissues • Cleaves and hydrolyzes proteins |

• Low potency • Reduces collagen and GAG contents • Disrupts elastin and collagen • Low potency • Not efficient for cell removal • Cleaves and hydrolyzes proteins |

Dermis, cartilage, cornea porcine pulmonary valves, heart valve, trachea | Zhou et al.,81 Dragúňová et al.,94 Rahman et al.,95 Lin et al.,96and Giraldo-Gomez et al.97 | |

| 2. Enzymatic | • Nucleases | • Digest and eliminate cellular and nuclear materials • Prevent the agglutination of DNA |

• Not effective alone • Prolonged exposer alter mechanical stability of ECM • High specificity |

Human lung, porcine heart valves, and kidney | Wagner et al.,98 and Ross et al.99 |

| • Lipase | • Catalyze the hydrolysis of cell lipids and phospholipids | • Depletes GAG content | Human amniotic membrane | Shi et al.100 | |

| 3. Physical 3.1 Freeze/Thaw |

• Disrupt cellular membrane • Maintains collagen and GAG content • Maintain mechanical strength |

• Insufficient removal of genetic materials lead to immune rejection • Ice formation and differences in temperature can destruct tissue structure |

Fibroblast cell sheet | Xing et al.101 | |

| 3.2 Emersion/agitation | • Used when the access to the vasculature is difficult Facilitates cellular content removal • Easy and fast procedure for small organs or tissues • Does not need specific bioreactor equipment |

• Excessive agitation can disrupt ECM • Unreliable for large animal or human whole organs • Usually needs increasing times |

Heart valves, skeletal muscle, urinary bladder, peripheral nerves, skin, cartilage | Tudorache et al.,102 Borschel et al.,103 Brown et al.,104 Karabekmez et al.,105 Reing et al.,51 and Elder et al.106 | |

| 3.3 Perfusion | • Infusion of agents through the organ vasculature • Preferred for large animal or human organs • Facilitates removal of cellular content • Preserves tissue ECM composition and architecture |

• Inappropriate perfusion pressures can disrupt ECM Optimization is required for each tissue/organ • Needs cannulation of the main organ artery • Usually needs specific perfusion bioreactor |

Heart, lung, liver, kidney, and pancreas | Zambon et al.,72 Ott et al.,14 Bonvillain et al.,107 Kajbafzadeh et al.,77 and Goh et al.108 | |

| 3.4 Pressure gradient | • Denatures cells with pressure • Short treatment time • Sterilizing tissue • Maintains the GAG and collagen structure |

• Disrupt the ECM ultrastructure • High pressure can denature ECM proteins • Leaves behind DNA remnants |

Whole organs and porcine blood vessel | Crapo et al.,11 Bolland et al.,109 and Funamoto et al.67 | |

| 3.5 HHP | • Short treatment time • Sterilizing of tissue • Destroying the cells |

Limited efficacy with small probe • Suitable just for soft and loose tissues • Left behind DNA remnants • Denatures ECM proteins in high pressure |

Liver, lung, cornea and blood vessels | Funamoto et al.67, Lin et al.,110, McDermott et al.,111 and Adachi et al.112 | |

| 3.6 Non-thermal electroporation | NA | • Substantial removal of volatile substances • Dehydration of the scaffold • Must be performed in the living species |

Cornea | Hashimoto et al.113 | |

| 3.7 Super critical CO2 | • Non-toxic and non-flammable • Mild critical temperature and detergent-free • Removes cellular and nuclear materials, • Preserve mechanical stability and biochemical contents of the ECM |

• NA | Adipose tissue, aorta and heart ECM hydrogel | Wang et al.,114 Guler et al.,115 and Seo et al.75 | |

ECM: extracellular matrix; SIS: small intestine submucosa; EDTA: ethylene diamine tetra acetic acid; EGTA: ethylene glycol-bis (β-amino ethyl ether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetra-acetic acid; 3D: tridimensional, SDS: sodium dodecyl sulfate; SD: sodium deoxycholate; CHAPS: 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl) dimethyl ammonia]-1-propane sulfonate; GAG: glycosaminoglycan; GFs: growth factors; HHP: high hydrostatic pressure; NA: not available.

Chemical and mechanical decellularization factors can be used to decellularize different kind of tissues, such as small intestine, urinary bladder and dermis, to create planar ECM sheets that can be further processed into ECM hydrogels.52,116 Whole organs can be decellularized for the bioengineering of transplantable organs.11,82,117 Perfusion of decellularization agents could be performed through the native vasculature of organs such as the kidney,82 liver,118 and lung119 which results in a 3D ECM scaffold that can be repopulated with patient-derived cells to engineer transplantable human organs.

Assessment of decellularization

In order to assess the decellularization process several criteria must be taken into account which among them evaluation of the immunogenicity and the mechanical property of dECM are the most essential. In the next section we discuss these points in detail.

Immunogenicity

One of the most important requirements of decellularization is evaluation of scaffold immunocompatibility and eventually reducing their immunogenicity. The immunological concerns have been a halting point for widespread use of dECM as scaffold in clinical applications. Xenogeneic scaffolds might be ideally the first choice to come into mind since they are abundant and easily obtained.120 However, xenogenic options might provoke the host immune reaction and if their immunogenicity is not sufficiently controlled, they may be finally rejected, leading to functional failure and the need for immediate replacement or removal. The two main components capable of inducing an immunogenic response include residual genetic materials such as DNA and RNA and antigenic peptides.121 In this respect, it has been suggested by Crapo et al, and Wendel Q et al, that the dECM containing less than 50 ng dsDNA per mg of ECM and less than 200 bp of DNA in length elicits no significant inflammatory reaction.11,122

Detergents including SDS and Triton X-100 are able to remove more than 90% of residual DNA.123 However, solvent/detergent and 3-cholamidopropyl dimethylammonio 1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS), have been shown less successful in this regard.89 In order to ameliorate this process, endonucleases including DNase and RNase have been used to break down nucleic acid fragments. Although these two enzymes effectively decrease the length of fragments and then prevent significant immunogenic responses, they are not very efficient in separating the fragments from the ECM.55

Native antigens are the other critical remnants that must also be reduced in the scaffolds to prevent immune rejection. Hyper-acute rejection of scaffolds, occurring shortly after implantation and caused mostly by host circulating antibodies, and acute rejection, occurring days to weeks after implantation, are of particular concern.124 Specific components that may be measured are alpha-Gal epitopes, which could potentially activate the immune response and major histocompatibility complexes (MHC) present on the cell membrane, which can consequently lead to T cell and natural killer (NK) cell responses.124 It has been demonstrated that other ECM structural proteins like collagen VI could also cause immunogenic reactions.125

On the contrary, there are some research studies that report lowered immunogenicity of decellularized tissues such as in pericardium implantation of human into mice models,126,127 dermal substitute from human placentas for full-thickness wound healing128 and decellularized human tendons.129 Besides, several other studies have shown that xenogeneic tissues show residual immunogenicity130 and may be contaminated with biological agents like prions and retroviruses that are difficult to detect and eliminate.64,131 The existence of these limitations associated with the use of decellularization and scaffold acellularity as the only standard measurement for the generation of xenogeneic scaffolds proves that further immunological verifications are extremely necessary. This clarifies the primordial need for improving strategies to remove antigens from xenogeneic tissues and organs, and assess the resultant scaffold residual antigenicity as a more specific immunocompatibility measurement. The antigen removal step avoids inaccurate simplification of the immunogenic issue, as observed with decellularization methods that merely target cell removal as a substitute for antigens removal.124

Mechanical properties

One of the most important aspects of tissue or organ regeneration via decellularization techniques is maintaining the mechanical integrity and characteristics of the natural tissue to ensure its proper functionality. Essential properties of interest are elastic modulus, viscous modulus, tensile strength, and yield strength; however, the most crucial properties ultimately depend on the nature of the tissue or organ’s desired function.132 These properties are principally controlled by the ECM structural proteins such as collagen, laminin, elastin and fibronectin.133 ECM proteins regulate cell adhesion and differentiation through integrin (adhesion receptor heterodimers) mediated signal transduction.134 Chondrocytes express several members of the integrin family including α5β1, which is the primary chondrocyte receptor for fibronectin.135,136

Each decellularization strategy has a distinct impact on these proteins. It has been revealed that the mechanical properties of scaffolds can be used to modulate the important aspects of cellular development like adhesion, growth, morphology, signaling, motility, and survival.133,137,138

Decellularizion of cartilage

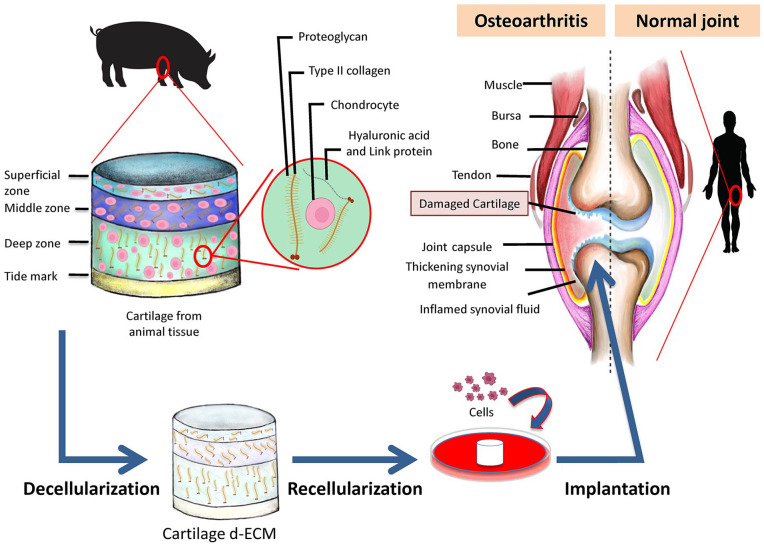

OA is a progressive degenerative joint disease affecting articular cartilage, bone and supporting ligaments leading to pain and loss of mobility.139 Several treatment methods have been used with the aim of pain relief and improvement of patients’ functional abilities. These treatments could be divided into two subcategories: (1) non-pharmacological methods such as physiotherapy, occupational therapy, weight loss and exercise, and (2) pharmacological and innovative methods with a particular aim of cartilage repair like oral and intra-articular administrations, immunotherapy, gene therapy, and cellular therapy including stem cell-based therapies.140 Nevertheless, current best evidence does not support any of these treatments superior to surgical interventions to repair initial cartilage lesions. Some of the surgical methods are microfracture (MF) (a marrow stimulation technique), autologous and allogeneic chondrocyte implantation (ACI), matrix-associated chondrocyte implantation (MACI), autologous matrix-induced chondrogenesis (AMIC), osteochondral autograft transplantation (OAT), osteochondral allograft transplantation (OCA) and direct cartilage suture repair. In general, MF and OAT are the best choices for smaller lesions (<2 cm2), OAT or ACI treatment options have been shown to be more effective for the intermediate lesions (2–4 cm2) and ACI or OCA were proven to be the better choices for larger lesions (>4 cm2).141 Due to the limitation of current treatments including complexity and high expenses of surgical interventions, lesions size, patients’ age and etc, the repair of cartilage lesions using tissue-engineering approaches is being extensively explored. To this goal, cartilage ECM could be one of the main candidates providing a natural scaffold for further applications. In order to use its potentials, cartilage ECM should be first decullularized (Figure 2). The presence of cells and cellular components such as antigens within the ECM that are derived from allogenic and xenogenic sources might induce the host inflammatory response leading to abnormal tissue remodeling and eventually graft failure.142 Further non-biological advantages of ECM decellularization are (a) decreased difficulties triggered by the living nature of the grafts, (b) elevated potential to be industrialized and commercialized and to achieve a ready to use product, and (c) potentially increased storage time that all together expand the operation maneuver for patients.143,144

Figure 2.

Summary of extracellular matrix decellularization procedures. Articular cartilage obtained from the animal knee is first decellularized. Acellular ECM maintains the structural and chemical integrity of the original tissue. Afterwards, the acquired dECM is used as a scaffold to reproduce a functional articular cartilage tissue by introducing different cell types, notably mesenchymal stem cells. The final engineered tissue can be transplanted into the knee joint of the OA patient.

Nevertheless, no standard method for cartilage decellularization is yet proposed. Previous studies demonstrated that the decellularization process itself could affect the residual matrix components, micro-architecture and micromechanical properties.145 Among them, decrease in sulfated GAGs,146,147 loss of inherent collagen content148, as well as reduced biomechanical properties146 of dECMs have been reported. Optimal decellularization methods that can effectively remove cellular components with only minimal disruption to other components, such as collagen, GAGs, and GFs, can help maintain ECM ultra-structure and micromechanical properties (Figure 2). For instance, chondrocytes grown in collagen microspheres produce GAG-rich ECM leading to promoted chondrogenic differentiation of MSCs upon decellularization.149 Furthermore, it was reported that dECM derived from chondrocytes plays a crucial role during the chondrogenic differentiation of human MSCs.150 Since harvesting chondrocytes from the healthy cartilage is a narrow procedure, other cellular sources including synovial derived stem cells (SDSCs), MSCs and co-culture of chondrocytes and MSCs were also largely studied.151,152 It has been shown that dECM derived from human MSCs maintain stem cell niche and enhance the MSC proliferation capacity.42 Others studies showed that MSC-derived dECM increases cell adhesion, matrix secretion, and chondrogenesis of marrow clots after microfracture.153–155 In addition, Guo et al.156 and Jingting Li et al.157 reported that dECM derived from SDSCs increases MSC proliferation and chondrogenic differentiation leading to a better cartilage repair.

As we have already mentioned, elimination of cells, preservation of ECM components, removal of genetic material and maintenance of mechanical properties are the main goals of decellularization procedure which are achieved by a wide variety of techniques such as physical (freeze/thaw cycles), chemical (detergents notably SDS and Triton X-100) and enzymatic treatments (trypsin, DNAse) (Table 2). Cartilage ECM represents more than 90% of the tissue volume and chondrocytes are the only cell type in the cartilage, therefore, for the most efficient preservation of ECM components and optimal cell removal, the most commonly used methods for cartilage decellularization are based on a combination of all those three techniques, which are evaluated and summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Articular Cartilage decellularization and recellularization protocols. The efficacy of cell removal, preservation of biochemical components, and mechanical properties has been evaluated by attributing the following scores: (++++) very effective, (+++) effective, (++) intermediate effective and (+) low effective.

| ECM origin | Decellularization protocol | Cell removal | ECM biochemical component | ECM mechanical properties | Recellularization protocol | Result | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Porcine articular cartilage | Chemical and enzyme treatment, Freeze-thaw • Combination with synthetic polymers for cell printing |

+ + + + | + + + | + + + | • hTMSCs • Suspended cells mixed with the ECM pre-gel supplemented with αMEM fetal bovine serum and antibiotics |

• Supported chondrogenesis differentiation and cell viability • Did not cause stress-induced apoptosis of the encapsulated cell |

Pati et al.46 |

| Porcine CMS | Carbon dioxide laser technique • SDS, DNase-I |

+ + + + | + + | + + + | • Rabbit-derived chondrocytes • Cultured for 8 weeks in vitro • Transplanted into rabbit |

• Formed cartilage-like tissue in vitro • Induced neocartilage and structural restoration in vivo |

Li et al.158 |

| hBMSC-derived ECM | Triton X-100 • Ammonium Hydroxide |

+ + | + + + + | + + + | • Human chondrocyte • Culture in chondrogenic medium • Implanted into SCID mice |

• Increased proliferation, chondrogenic differentiation, and chondrocytic phenotype • Cartilage formation with high sGAG deposition in vivo |

Yang et al.159 |

| Porcine knee articular cartilage | Physical pulverization • SDS • ribonuclease A |

+ + + + | + + | + + | • Rabbit ACs or ASCs • Cultured under microgravity condition in a rotary cell culture system bioreactor or static condition • Implanted into rabbit |

• Enhanced chondrogenic phenotypes without exogenous growth factors • Microgravity bioreactor induced more significantly the chondrogenicity • AC- and ASC displayed equal levels of hyaline cartilage repair |

Yin et al.160 |

| Porcine articular cartilage | Freeze-thaw cycles • Chondroitinase ABC • SDS |

+ + + | + + | + | • Porcine synovium-derived MSCs • Cultured for up to 28 days |

• Seeded cells infiltrated into the cartilage deep zone after 28 days | Bautista et al.161 |

| Bovine articular cartilage | Freeze-thaw cycles • Trypsin-EDTA • Osmotic shock • Supercritical CO2 |

+ + | + + | + + | • Bovine chondrocytes • Cultured in DMEM |

• Most of the cellular material was removed • Preservation of Sample structure and biocompatibility • Reduced cartilage elastic modulus • Cells adhered to the surface of scaffolds |

Antons et al.162 |

| Porcine articular cartilage | Deionized water or SDS • Sonication • Freeze-dried |

+ + + | + | + + | • Human MSCs • Cultured in high glucose DMEM with fetal bovine serum and Glutamax |

• Complete removal of cells • Comparable with native ultrastructure and biochemical contents • Cells adhered to the scaffold • Better preservation of matrix proteins in water decellularized cartilage |

Shen et al.163 |

| Bovine cartilage | Freeze-thaw • Triton X-100 • DNase and RNase • Pepsin and HCl or 3 M urea dissolved in water |

+ + | + + | + + | • Human MSCs • Suspension of cells in growth medium with or without additional supplementation |

• Pepsin-digestion provided medium supplement or 3Dhydrogels but did not promote differentiation • Urea-extraction promote chondrogenicity • TGF-β was not sufficient for urea-extraction • Incorporated urea-extracted cartilage within GelMA hydrogel enhanced chondrogenesis |

Rothrauff et al.164 |

| Human cartilage | Physical pulverization • EDTA • TritonX-100 • DNase and RNase |

+ | + + | + + | • Rabbit ADSCs • Chondrogenic medium • Implanted into rabbit models |

• Rabbit knees defects were filled 100% mostly with hyaline cartilage • Mechanical properties and biochemical components comparable to native tissue |

Kang et al.165 |

| Goat knee joint cartilage | Physical pulverization • SDS • DNase and RNase |

+ + + + | + + | + + | • Rat BMSCs • Co-cultured with cartilage ECM-derived particles in a microgravity rotary cell culture system • Implantation into trochlear cartilage defects rat model |

• Chondrogenic differentiated after 21 days without the use of exogenous growth factors • Obtained significant and rapid joint function recovery and superior hyaline-like articular cartilage repair in vivo • Supported MSC attachment and proliferation |

Yin et al.166 |

ECM: extracellular matrix; HCL: hydrochloride; hTMSCs: human turbinate mesenchymal stromal cells; MEM: minimum essential medium; SDS: sodium dodecyl sulfate; CMS: cartilage matrix scaffold; hBMSC: human bone marrow stem cell; SCID: severe combined immunodeficiency; GAGs: glycosaminoglycans; ACs: articular chondrocytes; ASCs: adipose-derived stem cells; MSCs: mesenchymal stem cells; DMEM: Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium; ADSCs: adipose-derived stem cells; TGF-β: transforming growth factor beta 1.

In several studies, scaffolds were prepared from cartilage which was shattered prior to decellularization.167 The first step of decellularization consists in cell lysis followed by the extraction of various cellular debris by using detergents like SDS and SD, which can solubilize membrane proteins and lipids and also control protein crystallization.168 Some research works utilized Triton X-100 as a type of non-ionic detergents, which are able to denaturate protein-protein interactions. Similarly, it can break up lipid-lipid and lipid-protein association.52,169 J. Antons et al.162 used supercritical CO2 technique to decellularize high density of articular cartilage. They showed that most of the cellular material was removed, while the tissue structure and biocompatibility was preserved. Furthermore, the DNA content was reduced in cartilage in comparison to the native tissue.

Other studies have tried to use decellularized cartilage tissue in the form of small particles rather than whole tissue to enhance chondrogenesis referred to as cartilage extracellular matrix-derived particles (CEDPs). They used decellularized cartilage microparticles with an average diameter of 263 μm to evaluate their in vitro and in vivo chondrogenic potential using BM-MSCs. They showed those MSCs were differentiated into mature chondrocytes after 21 days of culture without the use of exogenous GFs. Further, induction of hyaline-like articular cartilage repair was performed by the direct use of functional cartilage microtissue of MSC-laden CEDP aggregates for cartilage repair in vivo.166 Likewise, others developed CEDPs, for cell proliferation of articular chondrocytes (ACs) and adipose-derived stem cells (AD-MSCs), which improved the maintenance of chondrogenic phenotype of ACs, and induced chondrogenesis of AD-MSCs. Moreover, the functional microtissue aggregates of AC- or AD-MSCs-laden CEDPs induced equal levels of hyaline cartilage repair in a rabbit model.160

Cartilage tissue engineering, involving the combination of stem/progenitor cells with scaffolds, which serve as artificial ECMs, provides another promising strategy for cartilage regeneration. Recently, thermosensitive hydrogels due to their unique injectable property, no organic solvent, good biocompatibility, and biodegradability analogous to the native ECM have attracted much attention as scaffolds for cartilage tissue engineering.

Several advantages of thermosensitive hydrogels in cartilage tissue engineering have been reported. For instance, (1) seed cells can be easily embedded in the gel; (2) thermosensitive hydrogels could fill the irregular cartilage defects and prevent undesirable diffusion of precursor solutions; (3) their gelation can be simply triggered under mild physiological conditions, which avoid any organic solvents and harsh environment compared to other injectable hydrogels.170,171 In this setting, He Liu et al.,172 demonstrated that the introduction of phenylalanine which is a hydrophobic amino acid, into polyalanine-based thermosensitive hydrogel leads to the enhanced gelation behaviors and upregulated mechanical properties. Moreover, this process led to the enlarged pore size and enhanced mechanical strength of thermogel, followed by the regeneration of hyaline-like cartilage with reduced fibrous tissue formation. More recently, Chenyu Wang et al.,173 reported that the addition of injectable cholesterol to thermogel results in an elevated cartilage repair function such as lower gelation temperature, higher mechanical strength, larger pore size, better chondrocyte adhesion, and slower degradation.

Based on the promising outcomes of these tissue engineering methods, many different devices, scaffolds and injectable solutions has been developed for OA treatment during the last years in which some of them have already received the FDA approval. Table 4 summarizes these devises and their advantages and disadvantages in OA treatment.

Table 4.

FDA-approved and commercially available devices for OA treatment. This table describes the advantages, disadvantages and applications of different devices, scaffolds and injectable solutions for OA treatment. CS: chondroitin sulfate; AC: articular cartilage; OA: osteoarthritis; HA: hyaluronic acid; ACI: autologous chondrocyte implantation; MSCs: mesenchymal stem cells.

| Device type | Trade name | Company | Components | Device indication to use | Advantage | Disadvantage | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GENVISC 850, HYMOVISa | Orthogenrx INC, Fidia Farmaceutici | HA | Pain relief in knee OA | Doros et al.174 and Henrotin et al.175 | |||

| Natural injectable scaffolds |

TRILURON™a | Fidia Farmaceutici S.p.A. | Sodium hyaluronate | Pain relief in knee OA | • Absorbable • Easy to use • Easily accessible |

• Low mechanical stability • Low chondrogenisity |

Berenbaum et al.176 |

| TriVisca | OrthogenRx, Inc. | Sodium hyaluronate | Supplement the viscous fluid in the knee and relieve knee pain due to OA | Becker et al.177 | |||

| CaReS | Arthro Kinetics | Collagen type I gel matrix | Chondral knee defects | Roessler et al.178 | |||

| Natural non-injectable scaffolds |

Chondro-Gide | Geistlich Biomaterial |

Bilayer collagen type I/III scaffold |

Scaffold-associated chondrocyte implantation |

• Biocompatible • Easily accessible Bio-derived • Cell-free • Biodegradable • Full-thickness repair |

• Low mechanical stability • Invasive surgical procedures |

Steinwachs et al.179 |

| DeNovo®NT | Zimmer | Juvenile cartilaginous allograft tissue | AC repair and cartilage restoration. | Yanke et al.180 | |||

| ChondroGide | Geistlich | Porcine Collagen bilayer I/III | Cartilage regeneration with a smooth, compact top layer, and a rough, porous bottom layer | Haddo et al.181 | |||

| HyloFast | Anika | Single 3D fibrous layer HA-based scaffold |

Entraps MSCs to arthroscopically treat chondral and osteochondral lesions | Gobbi et al.182 | |||

| Natural non-injectable scaffold + cells | NeoCart | Histogenix | ACI on 3D Collagen scaffold | Rebuild knee cartilage | • Biodegradable • Biocompatible • Strong safety profile • No rejection |

• Not easy available • Invasive surgical procedures |

DeBerardino183 |

| Hyaff-11 | Fida advanced biopolymer | ACI on HA based polymer scaffold | Chondral knee defects | Turner et al.184 | |||

| Macia | Vericel Corporation | ACI porcine collagen scaffold | Repair of symptomatic, full-thickness cartilage defects of the knee in adult patients | Nixon et al.185 | |||

| Novocart 3D | Tetec | ACI on Collagen—CS Scaffold | Treatment of chondral knee defects | Zak et al.186 | |||

| Chondron | Sewon CellOnTech | Autologous chondrocyte implantations | Chondral knee defects | Choi et al.187 | |||

| Carticel | Genzyme | Expanded chondrocytes from patient’s knee | Repair of symptomatic cartilage defects of the femoral condyle, caused by acute or repetitive trauma | Manfredini et al.188 | |||

| Synthetic injectable scaffolds | Augment Bone Grafta | Biomimetic therapeutics, LLC | Beta-Tricalcium Phosphate + bovine collagen + human platelet-derived growth factor | Alternative autograft in arthrodesis of the ankle and hind foot due to OA | • Easily handled • (for hydrogel) • Easily available • Mechanical stability |

• Low chondrogenisity • Donor site morbidity • Invasive surgical procedures (scaffolds) Risk of allergy |

Solchaga et al.189 |

| Synthetic non-injectable scaffolds | R3 delta ceramic hip system | SMITH & NEPHEW, INC. | Ceramic-on-ceramic hip prosthesis | Use in skeletally mature patients requiring primary total hip arthroplasty due to non-inflammatory OA | Lee et al.190 | ||

| Cartiva® | Cartiva, Inc. | Polyvinyl alcohol and saline synthetic implant | Treatment of patients with degenerative or post-traumatic OA | Chang et al.191 | |||

| Synthetic non-injectable scaffolds + cells | BioSeed-C | Biotissue | ACI on 3D synthetic polymer scaffold | AC defects treatment in the knee | Kreuz et al.192 |

FDA-approved devices.

Recellularization of cartilage

Recellularization of the dECM must be performed in order to produce a functional tissue or organ before their administration (Figure 2). The cell type used to repopulate the matrix and recellularization methods are largely dependent on the complexity of the cell sheet, tissue, or organ. Stem/progenitor cells for this aspect can be generally classified as fetal cells, adult-derived stem/progenitor cells, adult-derived inducible pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and umbilical cord blood cells. Non-stem/progenitor cells used for organ engineering are usually parenchymal and supportive cells such as fibroblasts obtained from the organ of interest via biopsy or surgical harvest. Other cell sources can include endothelial cells (ECs) obtained from easily accessible sources such as peripheral blood or bone marrow.64 A summary of cartilage recellularization methods is listed in Table 3.

Cellularization of cell sheets can be accomplished by simply applying the cell suspension onto the monolayer surface, and 3D constructs can be created through shifting between the cell suspension and additional cell sheets as in the “sandwich model” for cartilage construction.193,194 High numbers of cells are required for the recellularization to produce a functional tissue or organ. In the joint cartilage, there are not enough resident cells available to invade the cell-free scaffold and to colonize it homogeneously. Thus, the cells mostly used in cartilage tissue engineering are MSCs which are multipotent and characterized by a high proliferative activity.195

BM-MSCs, AD-MSCs, infrapatellar fat pad stem cells (FP-SCs) and synovium have been proposed for cartilage tissue engineering in order to recellularize the cartilage dECM. AD-MSCs and BM-MSCs are easily and abundantly accessible.66 BM-MSCs and AD-MSCs have been seeded in a variety of 3D culture systems in an effort to generate cartilage-like tissue, including natural biopolymers such as collagen,196 silk fibroin and chitosan,197 hydrogels such as alginate, gelatin, agarose,198 silk fibroin,199 hyaluronan,200 and hybrids of synthetic and natural materials.201 It is important to mention that some of these culture systems are composed of synthetic materials that have never been exposed to a cellular environment. Therefore, the addition of cells will lead to neo-cellularization rather than re-cellularization. Cartilage-like tissue formation can be induced using these MSCs as evidenced by type II collagen, ACAN expression and accumulation of both cartilage markers in vitro and in vivo.202 Moreover, it has been observed that chondrogenic differentiation and ECM deposition are superior in BM-MSCs compared to expanded and de-differentiated chondrocytes.203 The addition of GFs such as transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGF-β1) or TGF-β3, fibroblast growth factors (FGFs) and Wnts superfamily members facilitates the expression of cartilaginous ECM and chondrogenesis, mediated by the transcription factor Sox9.204–206 BM-MSCs have a high proliferative activity, plasticity and release many trophic and bioactive factors.207 In addition, they synthesize stimulatory ECM components, which are critical for the use of in vitro produced MSC-derived cell- free ECM,208,209 mediating the capacity to differentiate into connective tissue cells (chondrogenic, osteogenic, adipogenic, and tenogenic lineage).209,210 Due to the lack of expression of co-stimulatory molecules and the production of several anti-inflammatory mediators, MSCs are immunoprivileged, immunosuppressive and possess immunomodulatory properties.211–213 Both immunomodulatory capacity and low immunogenicity are highly advantageous regarding MSCs as a cell source for reseeding decellularized scaffolds. MSCs cultured on the dECM scaffolds could enhance the biocompatibility of the constructs. In addition, the localized, sustained GF release of MSCs should promote cell proliferation, differentiation and ECM production in the scaffolds. The native cartilage ECM might still contain factors and structural stimuli inducing them into a specific and appropriate chondrogenic lineage.166,196 Furthermore, they can be harvested, enriched and seeded directly on the implanted ECM in a one-step surgical procedure.214

Post-decellularization procedures to improve cartilage dECM scaffold performance

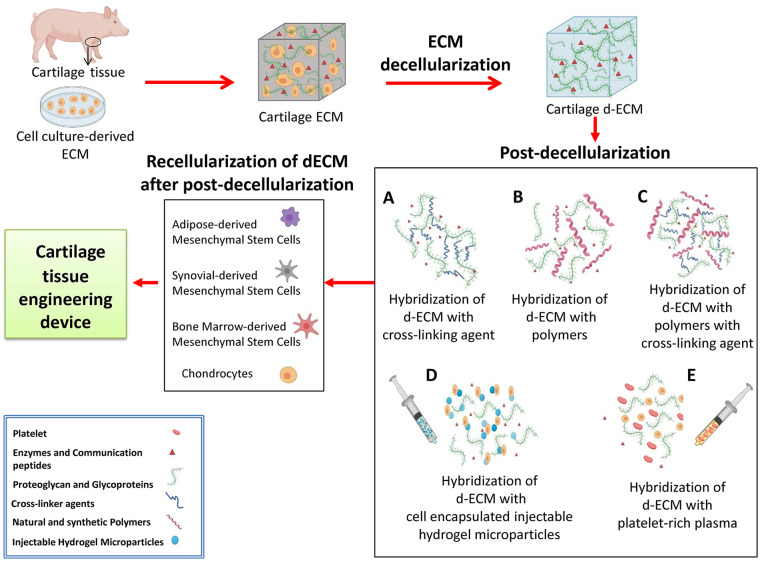

Conventional cartilage tissue engineering procedure consists of a scaffold decellularization and recellularization steps. However, lack of mechanical properties, load bearing capacity, rapid biodegradation, and contraction of these scaffolds in culture limits further applications.215 In this review we propose a series of post-decellularization procedures to overcome these shortcomings of each biomaterial including low mechanical strength and poor bioactivity to improve dECM scaffold towards much more efficient and higher integration. To achieve this aim, ECM-derived biomaterials can be crosslinked via different factors such as: cross-linking agents, natural and synthetic polymers, new synthetic polymers, cell-encapsulating injectable hydrogel microparticles, and platelet-rich plasma (PRP) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Cartilage tissue engineering process. In the first step, cartilage ECM is selected from different sources such as cartilage tissue or cell-culture-derived ECM. Thereafter, the decellularization process is performed to remove cells and their genetic materials. (a) dECM content is mixed with cross-linking agents, (b) polymers, (c) polymers via cross-linking agents, (d) cell encapsulated injectable hydrogel microparticles, and (e) platelet-rich plasma. After the post-decellularization procedures, cells are implanted into the final scaffold in a recellularization process. In the end, the cartilage tissue engineering product is ready for application.

Hybridization of dECM with cross-linking agents

One of the approaches to ameliorate ECM-derived biomaterials is crosslinking by physical and chemical methods (Figure 3(a)) which includes irradiation,216 dehydrothermal treatment (DHT),217 and chemical crosslinkers such as carbodiimide218 and genipin.219 Each of these methods can provide different crosslinking density and protein denaturation,220 which affect scaffold contraction,218 cell infiltration and cell-matrix interactions, mechanical properties221 and enzymatic degradation.222 A common method for cross-linking of proteins such as collagen and also some polymeric materials such as polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) is the DHT treatment.220 In this techniques, water molecules in polymer chains are removed by increasing temperature under reduced pressure. However, denaturation of biological components such as collagen chains during heating process, that may induce immunogenicity, is considered as an undesirable outcome in the DHT treatment.223 UV irradiation has also been performed to crosslink PVA hydrogel224 and as well as ECM based materials225 to function as vitreous implants or scaffolds for biomedical applications. To generate soft hydrogels; physical cross-linking of PVA has been also obtained by freezing and thawing cycles.226 Genipin is a natural crosslinker with cytotoxicity about 10,000 times lower than glutaraldehyde.227 Many studies explored the use of genipin in biomedical applications such as a crosslinker of tissue engineering scaffolds,228 to decrease immunogenicity of the scaffolds previous to implantation,229 for its anti-inflammatory properties,230 and for controlled release of GFs.231 The crosslinking mechanism of genipin is mediated via linking to primary amine groups of hydroxylysine or lysine residues on the polypeptide or proteoglycan chains, which results in the dark blue pigments formed in the matrix.232

Some studies showed that genipin is able to decrease Interleukin 1 beta (IL-1β) production in inflammatory diseases.233 Also, it has been demonstrated that genipin cross-linked tracheae can reduce inflammatory reactions in the xenograft models.234 Wang et al. reported that the natural genipin crosslinking could lower the immunogenic potential of xenogeneic decellularized porcine whole-liver ECM scaffolds by reducing the proliferation of lymphocytes and their subsets, accompanied by a decreased release of both Th1 and Th2 cytokines.235

Hybridization of dECM with natural and synthetic polymers

Biomaterials must be biocompatible, biodegradable, and mechanically stable to be used for tissue engineering perposes.236 Generally, synthetic and natural polymers are used to engineer biomedical scaffolds (Figure 3(b)).237 Synthetic polymers such as polyesters, polyglycolic acid, polylactic acid, and polycaprolactone (PCL) provide a wide range of benefits including high mechanical properties, controllable degradation, and high reproducibility.238 However, lack of biological properties is a widely known disadvantage of synthetic polymers.239 On the other hand, natural polymers such as fibrin, collagen, alginate, hydrogels and gelatin provide proper biological features, but their inadequate mechanical properties are recognized as major shortcomings.237

Based on the fact that the dECM provides outstanding cellular activities, it has been widely applied in cell-activating components in hybrid scaffolds or biocomposites,240 however, it lacks sufficient mechanical properties. In the following paragraphs, we mention some research studies that used biocomposite consisting of natural and synthetic polymers, which can be combined to dECM, to enhance post-decellularization techniques.

Collagen is known as the most abundant protein in mammalian tissues, such as bone, cartilage, tendon, and skin241 and it has been broadly applied in tissue engineering because of its exceptional biocompatibility. However, due to its low mechanical properties, collagen is not the optimal choice for bone and cartilage tissue regeneration; thus it has been a challenge to build a desired 3D porous structure with appropriate mechanical strength. Unlike collagen, silk fibroin (SF) has relatively high mechanical properties. SF was shown to be highly biocompatible and biodegradable.242 However, it is difficult to process SF solution due to its low viscosity. In recent, hybridization (or composite) of two or more types of biomaterials has been extensively studied to overcome the shortcomings of each biomaterial including low mechanical strength and poor bioactivity.243

Lee et al. used a low temperature printing process to create a 3D porous scaffold consisting of collagen, dECM to induce high cellular activities, and SF to reach the proper mechanical strength.244 O’Brien et al. developed a porous collagen/ hydroxyapatite (HA) composite and immersed it in SBF to increase the mechanical stiffness by 3.9-fold.245 Zhang et al. enhanced the mechanical strength (3.7-fold) of the alginate scaffold by adding chitosan.246 Furthermore, in order to provide cell friendly environment to synthetic polymers, Cheng et al.247 and Sousa et al.248 immobilized collagen on the surface of the hydrophobic PCL surface.

Hye Sung Kim et al. showed that cartilaginous dECM-decorated nanofibrils induced in vitro differentiation of AD-MSCs into chondrogenic lineage even without any additional exogenous GFs and cytokines.249 Another study investigated 3D bioprinting scaffolds for cartilage tissue by combining collagen type I or Agarose (AG) with sodium alginate (SA) incorporated with chondrocytes.250 The results showed that the addition of collagen or AG had a little impact on the gelling behavior and can improve the mechanical strength when compared to SA alone. Furthermore, the presence of collagen facilitated cell adhesion, accelerated cell proliferation, and enhanced the expression of the cartilage specific genes, namely Acan, Sox9, and Col2a1.250

Hydrogels are other natural biopolymers having a great potential, due to their structural resemblance to the ECM and their spongy framework, which enables cell transplantation, adhesion, differentiation and proliferation.251 Combination of hydrogels, dECM and other types of structures can therefore enhance their functionality and significantly improve the overall features of a 3D system.252

Gels of cytoskeletal proteins display particular mechanical responses (stress stiffening) that until now have been absent in synthetic polymeric and low-molar-mass gels. In one study, synthetic gels mimic in nearly all aspects gels prepared from intermediate filaments. They are prepared from polyisocyanopeptides grafted with oligo (ethylene glycol) side chains. These responsive polymers possess a stiff and helical architecture, and show a tunable thermal transition where the chains bundle together to generate transparent gels at extremely low concentrations. Polyisocyanide polymers are readily modified, giving a starting point for functional biomimetic hydrogels with potentially a wide variety of applications253 in particular in the biomedical field.

Kim et al. demonstrated that the surface-decorated polymeric nanofibrils with cartilage-derived dECM can render a synergistic effect on mimicking cartilage-specific microenvironment.249 They prepared polymeric electrospun nanofibrils decorated with cartilage-derived dECM as a chondro-inductive scaffold material for cartilage repair. To introduce cartilage-derived dECM into synthetic scaffolds, dECM powders or solutions were mixed with synthetic polymers formed a scaffold. Furthermore, chondrocytes or chondrogenically primed MSCs were seeded to prepare scaffolds for deposition of the cartilage-related ECM and then removed for cell reseeding or implantation.

Hybridization of dECM with new synthetic polymers using cross- linking agents

Polymeric materials used to design hybrid and composite scaffolds in cartilage tissue engineering most frequently consist of poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), poly-L-lactic acid (PLA), PCL, polyethylene glycol (PEG), PVA and methacrylamide modification (MA) (Figure 3(c)).254 Synthetic scaffolds are known to display adequate mechanical properties to match those of cartilage tissues, but their lack of appropriate biological cues reflect a main drawback.255 Accordingly, dECM-new synthetic polymers using crosslinking agents could improve this limitation of biological signals. For example, Setayeshmehr et al. investigated the fabrication of novel scaffolds based on devitalized costal cartilage matrix (DCM) and PVA, using genipin as a natural crosslinker. For this purpose, PVA was modified to expose amine groups (PVA-A), which crosslinked with DCM powder via the lowest genipin percentage of 0.04%. These findings suggest that genipin-crosslinked DCM-PVA-A/fibrin can be considered as an appealing hybrid scaffold for cartilage tissue engineering applications.215

Hybridization of dECM with cell incapsulated injectable hydrogel microparticles

A variety of biomaterials, both natural and synthetic, have been exploited to prepare injectable hydrogels; these biomaterials include chitosan,256 collagen or gelatin,257 alginate,258 hyaluronic acid,259 heparin,260 CS,261 PEG, and PVA (Figure 3(d)).262

Hydrogel microparticles (HMPs) are promising tools for biomedical applications, ranging from the therapeutic delivery of cells and drugs to the production of scaffolds for tissue repair and bioinks for 3D printing. Cells and drugs can be encapsulated into HMPs of predefined shapes and sizes. HMPs can be formulated in suspensions to deliver therapeutics, as aggregates of particles (granular hydrogels) to form microporous scaffolds that promote cell infiltration or embedded within a bulk hydrogel to obtain multiscale behaviors. HMP suspensions and granular hydrogels can be injected for minimally invasive delivery of active products, and they exhibit modular properties when composed of mixtures of distinct HMP populations. One major advantage of using HMPs for cell delivery is that cells are protected during the delivery process. Although bulk hydrogels may be injectable by exploiting shear thinning (decreasing the viscosity to increase shear rate), shear forces during injection may impact cells viability.263 Owing to their high water content and similarity to the native ECM, hydrogels are used as substrates for cell culture,264 biomaterials for tissue engineering265 and vehicles for drug and protein delivery.266 Traditionally, hydrogels are crosslinked into continuous volumes (bulk hydrogels) with external dimensions at the millimeter scale or larger and a mesh size at the nanometer scale that permits molecule diffusion.267

Hybridization of dECM with Platelet-Rich Plasma

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) is a blood product, which contains a high concentration of platelets268 with the ratio between two and eight folds compared to normal platelet concentration in adult peripheral blood.269 PRP was first introduced in regenerative medicine in the 1980s and 1990s, with the earliest documented uses for treatment of cardiac disease, dental damage, and maxillofacial surgery.270 Since then, it has also been used as a cell culture supplement for the expansion of stem and progenitor cells for tissue engineering applications in the context of muscule,271 bone,272 cartilage,273 skin,274 and soft tissue repair.275

PRP contains a mix of different cytokines and GFs, including platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) which is a protein that stimulates the proliferation and synthesis of new collagen formation; TGFβ-1 that counteracts the catabolic effects of IL-1 on tissues such as cartilage, by increasing chondrocyte synthesis as well as by increasing ECM production; FGF that is able to promote tissue healing by activating anabolic pathways; and finally hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) which increases tissue repair by promoting angiogenesis, as well as chemotaxis of MSCs, along with subchondral progenitor cells to promote chondral matrix formation and remodeling.269 Due to their high GFs content in platelet, PRP has been shown to improve cell growth in different research studies. Pham et al. showed an increased AD-MSC proliferation treated with PRP in standard medium after 24 h, compare to customary medium alone.276 In addition, Lucarelli et al.277 investigated the ex vivo influence of 1% and 10% PRP as platelet gel on BM-MSCs, showing a dose-dependent effect of PRP on cell proliferation.

Moreover, PRP has been utilized for the delivery of GFs and /or cells within tissue-engineered constructs, often in combination with biomaterials. For example, in bone tissue engineering, El Backly et al.272 reported that the combination of rabbit PRP with biodegradable freeze-dried gelatin hydrogels had the potential to increase bone repair in vivo.

Some studies have investigated the effect of PRP in osteochondral and cartilage repair. In this setting, most studies utilized PRP as a carrier for chondrocytes, progenitor cells or stem cells such as MSCs. For instance, Xie et al.273 published a testing PRP-delivered BM-MSCs and AD-MSCs in terms of their regenerative potential for osteochondral repair. PRP has been shown to induce MSCs to specially differentiate into chondrocytes and osteocytes in vitro via increasing chondrogenic (SOX9 and ACAN) and osteogenic (type I and type II collagen) markers in synovial tissue.278 Injections of PRP over 3 months in one study showed significant decreases in synovial fluid volume, as well as pro-inflammatory markers including apolipoprotein A1 (apo-A1), haptoglobin, immunoglobulin kappa constant (IGKC), matrix metallopeptidases (MMPs), notably MMP-13, and transferrin in mild to moderate OA.279 Besides, PRP has been shown to significantly reduce chondrocyte hypertrophy, a known step in the pathophysiologic degeneration of cartilage in OA.280 As part of its anti-inflammatory effects, PRP-rich environments have been shown to reduce IL-1β expression in chondrocytes, a known inhibitor of type II collagen and ACAN gene expression, as well as an inducer of MMP and nuclear factor kappa-light chain enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB), a major contributor to inflammation and the pathogenesis of OA.281

PRP has been also locally applied by means of scaffolds. Several pre-clinical evidences have shown a positive effect of PRP in association with different materials. Besides its application as an augmentation procedure, PRP itself has been modified to become a scaffold with the purpose of vehiculating cells and providing biological stimulation at the same time. Low immunogenicity and optimal biocompatibility, together with the clotting properties of PRP, make this product an interesting carrier for tissue engineering.282 Qi et al. have tested autologous PRP vehiculated by a collagen matrix for the treatment of patellar groove osteochondral lesions in the rabbit knee; they achieved better histological and mechanical results compared to collagen matrix alone.283 A further trial by Sun et al. evaluated the contribution of PRP added to a microporous PLGA scaffold to treat osteochondral defects created in the patellar groove in the rabbit model. This PRP-augmented scaffold was tested against the scaffold alone and results were quite significant.284

PRP can be utilized as an injection, or as a matrix adhered to a scaffold which can be introduced directly to damaged tissues.285 It has shown efficacy in treating many knee conditions, but by far has been studied most extensively in the treatment of OA of the knee. When compared with hyaluronic acid286 and CS,287 PRP shows improved clinical effects as well as a longer duration of action, potentially delaying the need for total joint replacement.

Post-decellularization procedures to improve dECM scaffold performance in other tissues

The interesting advantages of post-decellularization methods are not limited to cartilage tissue and OA treatment. Several other studies have demonstrated the promising impact of post-decellularization procedures on other tissues that are briefly discussed in this section.

In case of heart failure, individually alginate hydrogels and myocardial matrix-based therapies have been shown an interesting option for myocardial infarction (MI) treatment. Clive J Curley et al.,288 have successfully developed a production method for hybridization of dECM with alginate hydrogels. They demonstrated that the minimally invasive delivery of dual acting alginate-based hydrogels to heart results in appropriate rheological and mechanical properties.

In addition, in a model of tissue-engineered tracheal replacement, Yi Zhong et al.,289 have shown that the trachea of rabbit that was decellularized by detergent-enzymatic method (DEM) had better biocompatibility and lower immunogenicity than that by Triton-X 100-processed method, and the structural and mechanical characteristics of the acellular matrix were effectively improved after cross-linking by genipin. Furthermore, in a study comparing the ECM derived from human umbilical cord, crosslinked by genipin and N-(3-Dimethylaminopropyl)-N-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC) for neural tissue application, authors demonstrated that genipin, rather than EDC, improved the bio-stability of injectable ECM hydrogel in biocompatible concentration.290

In another example, Yizhong Peng et al.,291 established an injectable genipin-crosslinked decellularized annulus fibrosus (dAF) hydrogels and showed that they are better in case of formability, biocompatibility, bioactivity, and mechanical strength in comparison to non-crosslinked dAF.

Amnion is another tissue with potentially interesting properties to be used as scaffold.292 While it has a high risk of immunological rejection and infection, its decellularized form showed better compatibility. Amnion scaffold post-decellularization with PRP and calcium chloride composition has been shown to support better adherence to the wound than amnion alone. They can release GFs including VEGF, TGF, PDGF, and EGF, which increase the bioactive properties of PRP and thus amnion scaffold. Hybridization of amnion scaffold with PRP successfully interfered with the immune barrier and decreased the chances of immune rejection.293 The same positive effect was reported for decellularized bone matrix scaffolds (DBMs) showing that its hybridization with PRP can serve as a promising bone regeneration material such as improved cell adhesion and the capacity of DBMs for osseointegration with reduced immune rejection probability.294

Conclusion and perspective

In the absence of satisfying outcome by classical treatments, tissue engineering has emerged as a very attractive approach for cartilage repair utilizing natural and synthetic biomaterial scaffolds as well as xenogenic, allogeneic and autologous sources of cells and chondro-inductive GFs. In this review, we have highlighted the important considerations that have to be taken into account for a successful application of these highly variable and challenging techniques and products. Conventional procedures such as decellularization and recellularization have been already reported as standard methods for cartilage regeneration. Decellularization employs detergents, salts, enzymes, and/or physical means to remove cells from tissues or organs while preserving the ECM composition, architecture, bioactivity, and mechanics.

Here, we have mentioned in detail, specific roles, advantages and adverse effects of many agents and physical methods for using in decellularization protocols (Table 2).

These protocols are mostly a combination of several agents and physical methods; therefore, their efficacy for decellularization is severely dependent on the combinations of materials and methods, duration of exposure, type of tissue and organ, temperature and different other factors. Thus, we believe that it is more reliable to assess the general effects of these protocols on the main and comprehensive results of decellularization such as ECM alteration, cell removal, immunogenicity and ECM mechanical properties, rather than proposing the best-established method. It is also important to note that the optimal procedure may be different for each organ due to their unique anatomy.

In the case of cartilage tissue engineering, plenty of decellularization methods exist for different applications. The Supercritical CO2 physical technique, however, is one of the best methods for tissue decellularization. Because CO2 is diffusive, the commonly used solvents such as surfactants can be released quietly fast and does not remain in ECM, preventing the need for extensive wash procedures.295 Supercritical CO2 is even more efficient in cell removal by addition of ethanol avoiding harsh detergents’ application. Hence, instead of using SDS as detergent which can cause immense ECM damage and requires extensive wash process, we suggest emplying other kind of mild detergent such as SD and CHAPS to reduce the elimination of GAGs, GFs, and ECM proteins and consequently mechanical properties alteration. The key criteria for comparing cartilage decellularization methods are the efficiency of cell removal and the adequacy of ECM retention including its biochemical components and mechanical properties (Table 3).

Nevertheless, lacking a complete satisfaction using classical decellularization methods, we propose here, five complementary approaches including the hybridization of dECM with cross-linking agents, natural and synthetic polymers, new synthetic polymers using cross-linking agents, cell incapsulated injectable hydrogel microparticles and finally PRP for post-decellularization of ECM scaffolds that has been shown to have improving impact on cartilage tissue engineering outcome.

The introduction of post-decellularization methods including their hybridization with different agents turns back to very recent research studies most of them in their initial in vitro phases. Therefore, except for the hybridization of dECM with cross-linking agents such as genipin and some natural and synthetic polymers like hydrogel and the hybridization of dECM with PRP, no further clinical studies with improved cartilage repair outcome have been reported yet. Among the clinically assessed post-decellularization methods, however, we believe that PRP has much greater clinical potential since its administration was shown to be very effective in cartilage repair and eventually the treatment of OA and other inflammatory joint disorders. Due to its high concentration of platelets, PRP is a saturated source of important GFs and cytokines including but not limited to PDGF, TGFβ, HGF, and FGF that counteract the catabolic effects of IL-1 and other inflammatory mediators that contribute to the OA progress and at the same time increases chondrocyte synthesis. Besides, PRP has been used as a natural scaffold for vehiculating cells and providing biological stimulation at the same time. The interesting point to use PRP in comparison to other post-decellularization techniques is that PRP is considered as a non-modified blood product that according to medical regulatory authorities does not need many regulatory steps and procedures before its administration to the patients.

In the end, PRP has been administered for various tissue-engineering applications with encouraging outcomes. We believe that according to different important PRP effects such as anti-inflammatory properties, cell proliferation induction, differentiation induction, regeneration potentials, protective effects on chondrocytes, delivery of GFs, as well as in anabolic/ anti-catabolic pathways and ability to have a positive effect with other biomaterials, it will be an optimal choice to add to the dECM for future cartilage tissue engineering.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Mr Asghar NASERIAN, the head of the board of directors of SivanCell Company for the financial support.

Footnotes

Authors’ contribution: M.N.B, S.N and S.SH wrote the manuscript. S.N, S.SH and G.U reviewed and revised the manuscript.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Dr Sina NASERIAN is the CEO of CellMedEx company.

The rest of authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Miss Mahsa NOURI BARKESTANI was supported by a grant from SivanCell Company with the grant number: SC_FR-010919.