Significance

To perform hardware-based neuromorphic computing, novel materials exhibiting a wide variety of electronic properties are currently being explored. VO2 is well known to exhibit an insulator-to-metal transition as well as volatile resistive switching. Many questions regarding the basic mechanism of the nonvolatile switching in this material are unanswered. In this work, the formation and relaxation of conductive filaments through nonvolatile resistive switching in VO2 devices have been realized. The V5O9 Magnéli phase conductive filament has been identified. Our results demonstrate that both resistive switching behaviors can be achieved in a single material, crucial for future technology like resistive switching memories or neuromorphic logic.

Keywords: nonvolatile switching, transmission electron microscopy, conductive filament, neuromorphic computing

Abstract

Vanadium dioxide (VO2) has attracted much attention owing to its metal–insulator transition near room temperature and the ability to induce volatile resistive switching, a key feature for developing novel hardware for neuromorphic computing. Despite this interest, the mechanisms for nonvolatile switching functioning as synapse in this oxide remain not understood. In this work, we use in situ transmission electron microscopy, electrical transport measurements, and numerical simulations on Au/VO2/Ge vertical devices to study the electroforming process. We have observed the formation of V5O9 conductive filaments with a pronounced metal–insulator transition and that vacancy diffusion can erase the filament, allowing for the system to “forget.” Thus, both volatile and nonvolatile switching can be achieved in VO2, useful to emulate neuronal and synaptic behaviors, respectively. Our systematic operando study of the filament provides a more comprehensive understanding of resistive switching, key in the development of resistive switching-based neuromorphic computing.

The development of smaller, faster, and more energy-efficient resistive switching devices with multifunctions is crucial for realizing neuromorphic computing systems. In these, “neurons” (neuristors) are active components which produce nonlinear electric signals under external excitations, while the “synapses” (synaptors) control the connectivity between active elements (1). The challenge in developing a brainlike computing hardware is to mimic and integrate these active components and their interconnections using electronic devices. Two different classes of materials are generally proposed to emulate neurons and synapses. Correlated insulators with metal–insulator transitions (such as vanadium dioxide [VO2] or NbO2) commonly feature threshold or volatile resistive switching: the transition to the metallic state can be induced by applying a voltage, and the device returns to the insulating state once the stimulus is removed. This makes them ideal candidates for reproducing neural spiking (2). On the other hand, many noncorrelated systems, such as TiO2, HfOx, or phase-change materials, are well known for having reversible nonvolatile resistive switching, very promising for implementing synaptic behavior (3). In the case of oxides, this switching is due to the drift of oxygen vacancies under strong electric fields. Moreover, to improve the processing speed, scalability, device density, and connectivity like those in biological systems, the development of three-dimensional (3D) cross-bar circuit is necessary (4, 5). However, fabrication of 3D stacked arrays is difficult and further studies on vertical resistive switching devices will be required.

Among the different materials, VO2 has attracted much attention because of its threshold switching behavior and its insulator–metal transition (IMT) near room temperature (6–11). The mechanism behind the volatile switching in VO2 is believed to be a combination of thermal and/or electrical field-induced IMT in response to an external voltage/current input (12–15). However, unlike other transition-metal oxides such as TiO2 (16, 17), the microscopic nature of the electroforming process and nonvolatile switching behavior in the Mott insulator VO2 has not yet been explored (18). Interestingly, this provides the opportunity to realize nonvolatile resistive switching (caused by oxygen vacancy migration) coexisting with volatile resistive switching. This is of great potential, since the same material can show both neuronlike and synapselike functionalities. The nanoscale nature of the conductive filament poses a major challenge to the study of the nonvolatile switching mechanism (19). Here, combining operando transmission electron microscopy (TEM), transport measurements, and numerical simulations, we elucidate the electroforming process in Au/VO2/Ge vertical devices. The operando TEM studies allow us to conduct simultaneous structural and transport characterizations. The atomic structure of the nanoscale conductive filament was unambiguously determined and a filament relaxation/recovery mechanism has been demonstrated. Our study unveiled the essential role of oxygen defects in the filament formation and relaxation during resistive switching.

Results and Discussion

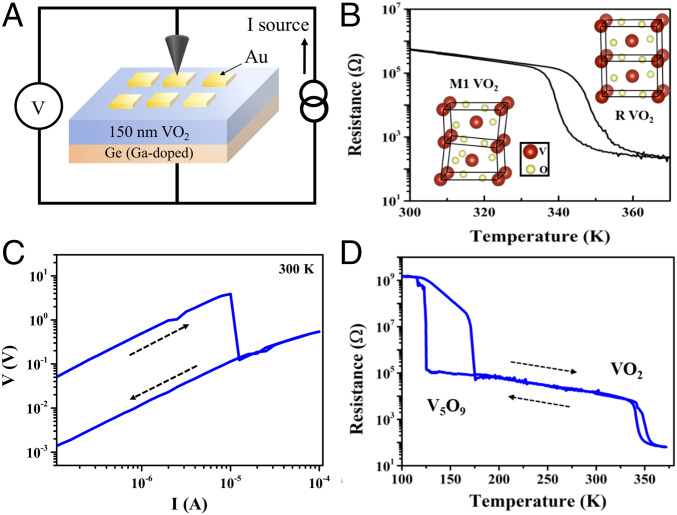

Fig. 1A shows a 150-nm VO2 thin film deposited onto a Ge substrate by magnetron sputtering. The single-phase growth of the (011) VO2 polycrystalline thin film was confirmed by X-ray diffraction (SI Appendix, Fig. S1) (20). The Ga-doped Ge substrate has p-type conductivity with a room temperature resistivity of 0.001 Ohms·cm. To investigate the resistive switching behavior, a VO2 layer sandwiched between two electrodes (Au as top electrode and highly doped Ge as bottom electrode as shown in Fig. 1A) was fabricated. Fig. 1B shows the thermal-induced IMT for one of the Au/VO2/Ge devices with a transition temperature, TIMT ∼345 K. This device exhibits a nearly three order of magnitude resistance change with a 10 K heating–cooling thermal hysteresis. The atomic unit cell of the low-temperature monoclinic insulating phase (noted as M1 phase) and the high-temperature rutile metallic phase are shown in the insets. Volatile resistive switching can be found for the Au/VO2/Ge devices when their temperature is raised close to the TIMT (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). The VO2 returns to the insulating state upon removing the external current. The mechanism of this switching has been studied earlier and is due to a combination of thermal (12–14) and/or nonthermal (15) switching depending on the details of the defects present.

Fig. 1.

Nonvolatile resistive switching in Au/VO2/Ge vertical devices. (A) Schematic illustration of the out-of-plane VO2 device and the measurement setup. The Au and highly doped Ge are top and bottom electrodes, respectively. (B) Resistance as a function of temperature of 150-nm VO2 film. (Inset) Low-temperature insulating VO2 monoclinic phase (M1 VO2) and high-temperature metallic VO2 rutile phase (R VO2). (C) Room-temperature I-V curve. (D) After electroforming, the R-T curve of the VO2 device shows another metal-insulator transition behavior at low temperatures.

Fig. 1C shows the I-V curve measured at room temperature, featuring clear nonvolatile resistive switching. As the current increases to the threshold value, a large drop of the voltage indicates the formation of the low-resistance state between the two electrodes. The subsequent temperature-dependent transport measurement of this device reveals another insulator–metal transition around 140 K with a 50 K-wide thermal hysteresis. Moreover, this IMT shows a resistive asymmetry between the heating and cooling branches. The broadening of the hysteresis and the asymmetry in the R-T curve have been observed in many one-dimensional correlated oxide systems (21, 22). In addition, like other transition-metal oxides (1, 18, 23), oxygen migration in VO2 may lead to the formation of oxygen-deficient filaments. Thus, the pronounced IMT with several orders of magnitude resistance change might be associated with an oxygen-deficient vanadate phase within the VO2 film. Due to the multiple possible vanadium oxidation states, a whole oxide family known as Magnéli (VnO2n−1) and Wadsley phases (VnO2n+1) (24) are stable. Among these compounds, only V2O3, V5O9, and V6O11 have lower oxygen/vanadium ratios than VO2 with an IMT near 140 K. This implies that these VO2−x phases are possibly formed during the resistive switching within the VO2 film.

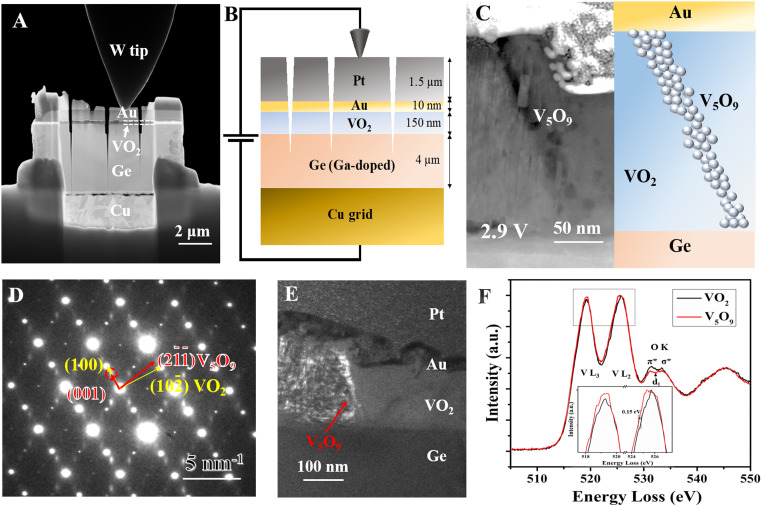

To understand the nonvolatile switching mechanism and gain insights into the filament formation, in situ biasing TEM experiments were carried out. The experimental setup is shown in Fig. 2A. All the experimental images in Fig. 2 are scanning transmission electron microscopy high-angle annular dark-field (STEM-HAADF) images, which are sensitive to the atomic weight in the sample (25). As illustrated in Fig. 2B, the top Au and Pt layers are the protection layers deposited during FIB (focused ion beam) process and used as top electrode in the biasing experiments. The sample was separated into two independent out-of-plane devices by three vertical FIB cuts. The piezocontrolled W tip was grounded and made a contact with the top Pt layer. A live view of the device with different applied voltages was captured and is shown in Movie S1. While sweeping the voltage from 0 to 3 V, the conductive filament becomes visible as the dark regions in the image. The STEM images showing the changes of the sample are in SI Appendix, Fig. S3. Fig. 2C depicts the morphology of the conductive filament and the corresponding schematic representation of the conductive filament is shown. The selected area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern acquired from the filament area (the actual selected area on the sample is about 100 nm in diameter) is shown in Fig. 2D. Together with the electron diffraction peaks from the M1 VO2 phase (the electron diffraction pattern for the pure M1 VO2 can be found in SI Appendix, Fig. S4), an additional set of diffraction peaks with about 1/3 of the reciprocal lattice spacing of VO2 along the a axis (indicated by red arrows) is observed. This is identified as the V5O9 phase. The simulated SAED patterns captured along M1 VO2 [010] and [102], as well as V5O9 [120] directions, are shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S5, which match well with the experimental diffraction pattern in Fig. 2D. Considering the lattice symmetry, both the M1 VO2 and V5O9 phases have structural variants, i.e., twinning. A diffraction mirror plane can be identified. Using the diffraction spot from the V5O9 phase, as indicated by the red circle in Fig. 2D, a dark-field TEM image was acquired (Fig. 2E), showing the distribution of the newly formed V5O9 phase. The shape of the conductive filament is consistent with that shown in Fig. 2C, showing that the conductive filament is composed of V5O9 phase. The high-resolution TEM image acquired from the filament area is shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S6. The dark-field TEM image also shows some isolated V5O9 nanograins (within tens of nanometer in size) near the conductive filament formed during the electroforming process. The region identified as conductive filament is within a VO2 matrix. It is noteworthy to mention that V5O9 phase also shows a first-order IMT (the transition temperature is about 135 K), consistent with the low-temperature IMT shown in Fig. 1D (26, 27). Electron energy-loss spectroscopy (EELS) results also reveal the change of V valence state in the conductive filament area (28). Since the L2,3 edges of V are very close to the O K edge, L3 and L2 area ratios cannot be used to extract the valence state of V (10). However, the change of valence states could affect the number of screening electrons around the nucleus, thus resulting in a change in the onsite energy of the L3 edge. Furthermore, considering the VO6 octahedral coordination, the lowest unoccupied state should change as well, which should be reflected in the oxygen K edge. Fig. 2F shows a 0.15 eV redshift in energy for the V5O9 phase, which is an indication for the decrease of the V valence state and the stoichiometry change (27). The energy positions for π*, σ*, d// orbitals in the VO2 EELS spectrum can be identified in oxygen K edge, which is consistent with X-ray results (29). In V5O9 phase, the formation of oxygen vacancy increases the occupation of the π* orbital and thus the first peak in the oxygen K edge should decrease. Since V5O9 is conductive at room temperature, its orbital diagram can be deduced from an analysis of the orbital hybridization (see SI Appendix, Fig. S7 for details) (10).

Fig. 2.

Operando TEM studies showing the formation of conductive filament. (A and B) HAADF image and schematic diagram of the experimental setup of the VO2 device. Each FIB sample has three vertical cuts, making two out-of-plane devices. (C) Experimental image and the corresponding schematic of the conductive filament. (D) SAED acquired from the conductive filament area. (E) Dark-field image using the diffraction spot marked by red circle ((001) of V5O9) in D. (F) Core-loss EELS for VO2 and V5O9. Approximately 0.15-eV energy shift is found for the V5O9.

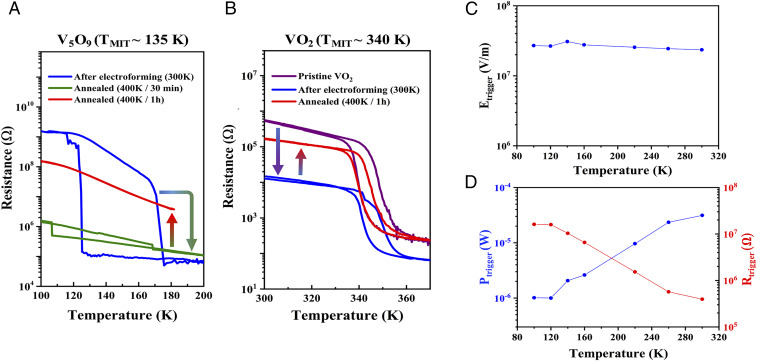

The mechanism of oxygen migration and the switching reversibility can be further studied by thermally annealing the device after the nonvolatile filament formation. Transport properties of strongly correlated oxides, such as VO2 and V5O9, are extremely sensitive to the variation in oxygen content, carrier density, and structural disorder (30). Fig. 3A shows the R-T curve of the V5O9 filament after the IV switching (blue curve), after annealing in air for 30 min (green) and 1 h (red) at 400 K. The R-T curve changes dramatically, showing the recovery from V5O9 to the original VO2 state as a result of the reoxidation of the filament during annealing. The resistance in the low-temperature region increases with longer annealing time associated with a degradation of the V5O9 IMT, indicating the disappearance of this Magnéli phase. It may be worthwhile to mention that small change along the filament length could result in a large change in the total resistance, making the low-temperature IMT signal appear to be strong. The R-T measurements at high temperature reveal the VO2 IMT, as shown in Fig. 3B. After the V5O9 filament forming, the magnitude of the VO2 IMT is slightly reduced. This electroforming process is likely to increase the density of oxygen vacancies and lead to oxygen loss from the VO2 monoclinic structure. These vacancies behave as electron donors in the original VO2, thereby increasing the number of free-charge carriers and reducing the magnitude of the IMT. After annealing, the VO2 will partially recover to the original state. The reduced resistive change and the decrease in the hysteresis loop width across the IMT indicate further the presence of the oxygen-deficient phase.

Fig. 3.

Relaxation of the nanoscale filament in VO2. (A) R vs. T for a device at low temperatures: after the nonvolatile resistive switching (blue); after thermal annealing for 30 min at 400 K in air (green); after thermal annealing for 1 h at 400 K in air (red). (B) R vs. T curve for a device at high temperature: pristine VO2 device (purple); after nonvolatile resistive switching (blue); after thermal annealing for 1 h at 400 K in air (red). (C) Breakdown electrical field as a function of device temperature. (D) Power dissipation (Ptrigger) and switching resistance (Rtrigger) as a function of device temperature for VO2 nonvolatile switching.

The breakdown electric field of the nonvolatile filamentary switching is temperature independent at nearly ∼28 MV/m (Fig. 3C). Moreover, the power needed to induce nonvolatile switching increases with increasing device temperature (Fig. 3D). This is inconsistent with pure Joule heating-triggered behavior and indicates the presence of oxygen migration, as described before (31). On the other hand, triggering the volatile resistive switching at high temperature (∼TIMT) may be dominated by local Joule heating. In this case, the power dissipation and threshold voltage are expected to decrease with increasing device temperature (32). The temperature dependence of the breakdown electric field will be significant. These results show that both volatile and nonvolatile resistive switching can be realized, but as evidenced by the very different T dependence, caused by different mechanisms in the Au/VO2/Ge vertical geometry.

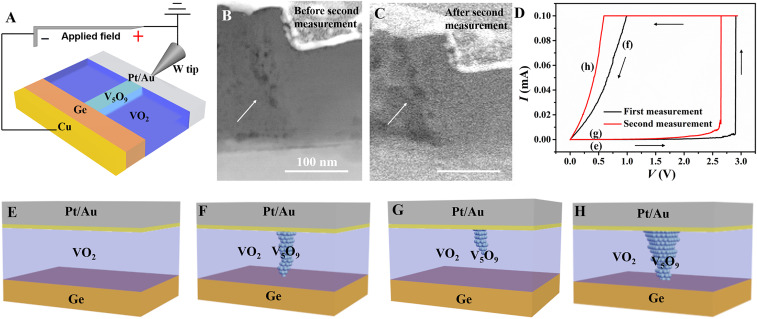

Using the experimental setup shown in Fig. 4A, the reversibility of the conductive filament in Au/VO2/Ge vertical device was studied in TEM. The compliance current was limited to 0.1 mA and the first “set process” is shown in black in Fig. 4D. The IV curve was measured simultaneously while recording the TEM images, as shown in Fig. 2. The device has high resistance initially and the current increases sharply with the application of 2.8 V. The sample resistance decreases markedly with the formation of the conductive filament as illustrated in Fig. 4 E and F. This in situ biasing measurement agrees well with the ex situ device measurement shown in Fig. 1C. After the biasing experiments, the sample was annealed in air at 400 K for 30 min to test its reversibility. Fig. 4B shows the morphology of conductive filament after partial recovery. The dark areas clearly decreased compared with those shown in Fig. 2C. The V5O9 phase returns to VO2 during annealing in air, showing the reversibility of the nonvolatile resistive switching. The second test was applied under the same condition on the recovered sample, and the IV curve is shown in red in Fig. 4D. Similar to the first measurement, the sample shows high-resistance state and changes to low-resistance state at 2.6 V. The change of voltage decreases slightly, due to the remaining V5O9 phase in the recovered sample, as illustrated in Fig. 4G. The snapshot after the second switching experiment (videos can be found in Movie S2) is shown in Fig. 4C, showing the formation of the conductive filament. The new filament appears at the same position of the old one, indicating that the filament has a “memory effect.” However, the diameter of the filament becomes bigger, as illustrated in Fig. 4H, which is consistent with the lower-resistance state in the second measurement. From the TEM measurements, we found that the conductive filaments form in a randomly fashion between the top and bottom parallel electrodes. It is possible that the local defects, such as oxygen vacancies, grain boundaries, domain boundaries may facilitate filament formation, and further exploration is needed. Based on our He+ ions injection simulations, it is also possible to control the formation of Magnéli phase and create conductive filaments (details of which can be found in SI Appendix).

Fig. 4.

Reversibility of the nonvolatile resistive switching. (A) The schematic showing the formation of V5O9 conductive filament under external bias. (B) HAADF-STEM showing the morphology of the conductive filament after recovery. (C) Formation of the conductive filament at the same position after second biasing experiment. (D) IV curve measured in situ in the TEM. The black and red curves show the IV results for the first and second measurement, respectively. For the first measurement, the initial state is illustrated in E. The low-resistance state after electroforming process is shown in F. After the recovery, the partially survived filament is plotted in G, which is the starting state for the second measurement. The final state with the formation of thicker conductive filament after second switching is demonstrated in H.

To deepen the understanding about the formation and relaxation of the conductive filament in the volatile and nonvolatile switching (11, 33), numerical simulations using Mott resistors network model were performed as illustrated in SI Appendix, Fig. S8. A load resistance Rload is making a voltage divider circuit with a resistor network, where each resistor takes the resistance values of rutile VO2, M1 VO2, or V5O9. At different temperatures, the competition between two insulator–metal transitions produces a volatile transition driven by Joule heating predominant when T approaches TIMT and a nonvolatile transition associated with a structural transition that dominates at T well below TIMT, activated by the local electric field. Near the IMT (338 K), the system shows volatile switching and the conductive filament is mainly formed by rutile VO2 as shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S9. At low temperature (280 K) shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S10, the system exhibits nonvolatile switching and the conductive filament is made of V5O9 phase. Vth is the threshold voltage that triggers volatile switching.

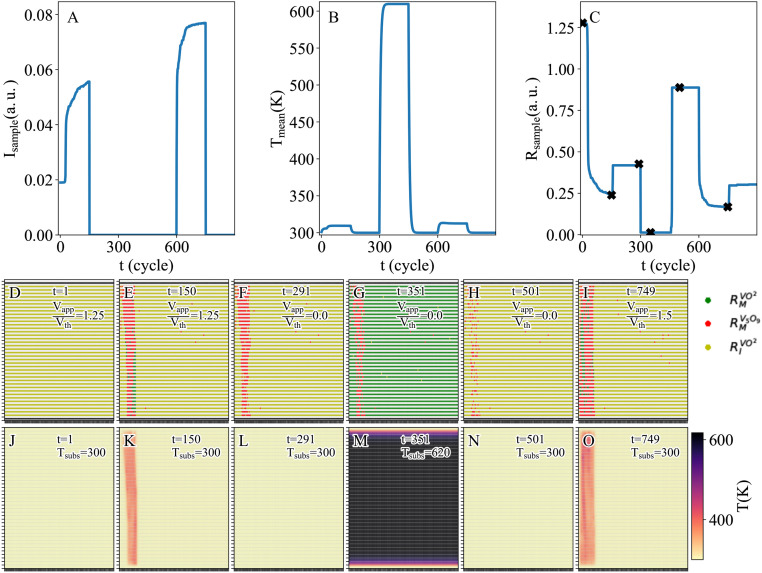

In Fig. 5, we present the room-temperature simulations. Applying an above-threshold pulse (the applied voltage is 1.25 times of threshold voltage, i.e., Vapp/Vth = 1.25), a V5O9 (red color in Fig. 5E) filament is created by voltage activation together with a partially metallic VO2 (green in Fig. 5E) produced by Joule heating. The threshold voltage (Vth) is the minimum value able to let the transition from the metallic to the insulating state beginning from a given temperature and letting the voltage act for long time. While rutile VO2 fraction relaxes back to its insulating state (11), after the pulse ends, the V5O9 persists unchanged (Fig. 5F). The annealing process can be simulated by increasing the substrate temperature to 620 K after the creation of the filament. The V5O9 gradually turns back into metallic rutile VO2 (Fig. 5G), so by cooling back the system to the initial value the conductive filament is partially recovered due to the thermal transition from rutile VO2 to M1 VO2 (Fig. 5H). The timescale for the annealing process of the V5O9 filament depends on the substrate temperature, i.e., a lower temperature leads to a longer relaxation time. If a second pulse below threshold (Vappl/Vth = 0.85) is applied after the annealing process, a V5O9 filament forms at the same position. This “subthreshold” effect (11) is in good agreement with earlier experimental results. The full simulated movie can be found in Movie S3.

Fig. 5.

Numerical simulations showing the formation and relaxation processes of conductive filaments at room temperature. (A) Electric current of the resistor network as a function of time. A first voltage pulse of Vapp/Vth = 1.25 is applied from t = 1 to t = 150 and a second one of Vapp/Vth = 0.85 is applied from t = 600 to t = 750. (B) Average temperature through the network as a function of time. The small variation in the sample temperature at 300 K is due to the applied voltage that induces local Joule heating. The substrate temperature is increased up to 620 K for annealing purpose at 300 < t < 450 and 750 < t < 1200. (C) Resistivity of the resistor network as a function of time. (D–I) Distributions of metallic rutile VO2 (green), V5O9 phase (red), and insulator M1 VO2 (yellow) at different stages: (D) t = 1 (starting position); (E) t = 150 (during first pulse voltage of Vapp/Vth = 1.25); (F) t = 291 (after relaxation of the first pulse); (G) t = 351 (during the first annealing process); (H) t = 501 (after the first annealing process); (I) t = 749 (the second pulse with smaller stimuli). These different stages are marked as stars in C. Note, the t is the simulation step. (J–O) The corresponding temperature distributions in degrees Kelvin. The whole simulation is shown in Movie S3.

Unlike TiO2 (16), VO2 exhibits a metal–insulator transition above room temperature. In TiO2, a large reset current can be used to disrupt the conductive filament by Joule heating. However, for VO2, it is not possible to reset the conductive path using electrical stimuli after the electroforming process. The surrounding areas of V5O9 conductive filament will be heated up by the current, leading to the formation of metallic rutile-phase VO2. The large current will flow through the metallic rutile-phase VO2 rather than accumulating enough heat for oxygen migration, which can be inferred from our simulation results shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S11.

Based on our experimental data and the simulation results, filament formation process can be understood by this scenario: 1) During the initial switching stage (electroforming), the oxygen vacancies start moving under the external field. Above certain oxygen vacancy level, the isolated V5O9 nanograins will form in some part of the VO2 thin film. 2) Once the V5O9 nanograins connect between two electrodes, large current will naturally flow through the conductive pathway. The filament is shorting the rest parts of the VO2 film which are highly insulating. The voltage/electric field will be significantly reduced after the switching and prevent further formation of other V5O9 conductive filament.

In conclusion, coordinated in situ and ex situ experiments using voltage bias of VO2 show the formation of V5O9 conductive filaments. Besides the intrinsic volatile switching of VO2, the nonvolatile switching can be attributed to the appearance and disappearance of the V5O9 Magnéli phase. These behaviors are well captured by numerical simulations of a theoretical model which provides support to the idea that two electric field-induced insulator–metal transitions are competing in VO2. Our study identified the essential role played by the Magnéli filament within the VO2 device. This is supported with detailed characterizations of the insulator–metal transition, phase composition, lattice structure, and its relation to the surrounding VO2. We demonstrated that two different resistive switching behaviors can be induced using Au/VO2/Ge vertical resistive switching device. This is of great interest to emulate both neuronal and synaptic behaviors on the same material. Moreover, we have identified a filament relaxation effect that allows the system to forget. This could have crucial implications in the implementation of oxide-based devices for neuromorphic computing. Our findings could be applied to a broad range of interdisciplinary fields, including strongly correlated materials, complex oxides with IMT behavior. Also, the second IMT of the Magnéli V5O9 filaments is an excellent candidate for low-temperature applications. We believe this work is likely to be of great interest to researchers exploring new resistive switching oxide devices with different memory effects and modulating transport properties across metal–insulator transitions in oxide-based technology. Thus, another route for realizing neuromorphic computing has been found.

Materials and Methods

TEM Studies.

The TEM studies were carried out on an FEI Talos microscope at 200 kV accelerating voltage. The in situ biasing study was carried out with an STM Nanofactory in situ biasing holder. TEM samples were fabricated by an FEI Helios dual-beam system. The samples were polished at low voltages to remove the surface damage layers at the last step of the sample preparation. A 10 µm selective-area aperture was used for acquiring electron diffraction patterns. The EELS was acquired with 0.1 eV/ch dispersion. To satisfy the selection rule, the convergence angle was 19.1 mrad and the collection angle was 39.6 mrad. The energy resolution was estimated to be 0.7 eV.

Thin-Film Growth and Device Fabrication.

Polycrystalline VO2 thin films, 150 nm thick, were grown on (100)-oriented P-type Ga-doped Ge substrates by radio frequency magnetron sputtering from a V2O3 target. The growth of VO2 was done at a substrate temperature of 445 °C using an Ar/O2 mixture (8% O2) at 3.7 mTorr. Single-phase growth of VO2 was confirmed by room-temperature θ-2θ X-ray diffraction using Rigaku SmartLab with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.54 Å) and TEM. Using e-beam evaporation and a shadow mask, 100 nm Au top electrodes for electrical transport measurements were fabricated.

Electrical Measurements.

Temperature-dependent electrical transport of Au/VO2/Ge devices were performed in a Lakeshore TTPX probe station with a Keithley 6221 current source and a Keithley 2182A nanovoltmeter in a two-point probe configuration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The structural characterization, transport, operando TEM, and collaboration among University of California San Diego (UCSD), Brookhaven National Laboratory (BNL), and CNRS were supported through an Energy Frontier Research Center program funded by the US Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences, under Grant DE-SC0019273. Electron microscopy work at BNL and the use of BNL’s Center for Functional Nanomaterials were supported by DOE-BES, the Division of Materials Science and Engineering, and the Division of Science User Facility, respectively, under Contract no. DE-SC0012704. The thin-film deposition and device fabrication were funded by the Vannevar Bush Faculty Fellowship program sponsored by the Basic Research Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering, and by the Office of Naval Research through Grant N00014-15-1-2848.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2013676118/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability

All study data are included in the article and/or supporting information.

References

- 1.Valle J. D., Ramírez J. G., Rozenberg M. J., Schuller I. K., Challenges in materials and devices for resistive-switching-based neuromorphic computing. J. Appl. Phys. 124, 211101 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yi W., et al., Biological plausibility and stochasticity in scalable VO2 active memristor neurons. Nat. Commun. 9, 4661 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ielmini D., Wong H.-S. P., In-memory computing with resistive switching devices. Nat. Electron. 1, 333–343 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pickett M. D., Medeiros-Ribeiro G., Williams R. S., A scalable neuristor built with Mott memristors. Nat. Mater. 12, 114–117 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang J. J., Strukov D. B., Stewart D. R., Memristive devices for computing. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 13–24 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shao Z., Cao X., Luo H., Jin P., Recent progress in the phase-transition mechanism and modulation of vanadium dioxide materials. NPG Asia Mater. 10, 581–605 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morin F., Oxides which show a metal-to-insulator transition at the Neel temperature. Phys. Rev. Lett. 3, 34 (1959). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumar S., et al., Sequential electronic and structural transitions in VO2 observed using X-ray absorption spectromicroscopy. Adv. Mater. 26, 7505–7509 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wall S., et al., Ultrafast disordering of vanadium dimers in photoexcited VO2. Science 362, 572–576 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aetukuri N. B., et al., Control of the metal-insulator transition in vanadium dioxide by modifying orbital occupancy. Nat. Phys. 9, 661–666 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Del Valle J., et al., Subthreshold firing in Mott nanodevices. Nature 569, 388–392 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zimmers A., et al., Role of thermal heating on the voltage induced insulator-metal transition in VO2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 056601 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar S., et al., Local temperature redistribution and structural transition during joule-heating-driven conductance switching in VO2. Adv. Mater. 25, 6128–6132 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Madan H., Jerry M., Pogrebnyakov A., Mayer T., Datta S., Quantitative mapping of phase coexistence in Mott-Peierls insulator during electronic and thermally driven phase transition. ACS Nano 9, 2009–2017 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kalcheim Y., et al., Non-thermal resistive switching in Mott insulator nanowires. Nat. Commun. 11, 2985 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kwon D.-H., et al., Atomic structure of conducting nanofilaments in TiO2 resistive switching memory. Nat. Nanotechnol. 5, 148–153 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang K., et al., Distinguishing oxygen vacancy electromigration and conductive filament formation in TiO2 resistance switching using liquid electrolyte contacts. Nano Lett. 17, 4390–4399 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wong H.-S. P., et al., Metal-Oxide RRAM. Proc. IEEE 6, 1951–1970 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun W., et al., Understanding memristive switching via in situ characterization and device modeling. Nat. Commun. 10, 3453 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang Z., Ko C., Ramanathan S., Metal-insulator transition characteristics of VO2 thin films grown on Ge (001) single crystals. J. Appl. Phys. 108, 073708 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 21.del Valle J., et al., Resistive asymmetry due to spatial confinement in first-order phase transitions. Phys. Rev. B 98, 045123 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fan W., et al., Large kinetic asymmetry in the metal-insulator transition nucleated at localized and extended defects. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 83, 235102 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Waser R., Aono M., Nanoionics-based resistive switching memories. Nat. Mater. 6, 833–840 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schwingenschlögl U., Eyert V., The vanadium Magnéli phases VnO2n‐1. Ann. Phys. 13, 475–510 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheng S., et al., Interface reconstruction with emerging charge ordering in hexagonal manganite. Sci. Adv. 4, eaar4298 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fisher B., Genossar J., Reisner G. M., Systematics in the metal-insulator transition temperatures in vanadium oxides. Solid State Phys. 226, 29–32 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marezio M., Dernier P. D., McWhan D. B., Kachi S., Structural Aspects of the metal-insulator transition in V5O9. J. Solid State Chem. 11, 301–313 (1974). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tan H., Verbeeck J., Abakumov A., Tendeloo G. V., Oxidation state and chemical shift investigation in transition metal oxides by EELS. Ultramicroscopy 116, 24–33 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koethe T. C., et al., Transfer of spectral weight and symmetry across the metal-insulator transition in VO(2). Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 116402 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu K., Lee S., Yang S., Delaire O., Wu J., Recent progresses on physics and applications of vanadium dioxide. Mater. Today 21, 875–896 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 31.del Valle J., et al., Electrically induced multiple metal-insulator transitions in oxide nanodevices. Phys. Rev. Appl. 8, 054041 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vitale W. A., et al., Steep-slope metal–insulator-transition VO2 switches with temperature-stable high ION. IEEE Electron. Device Lett. 36, 972–974 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Janod E., et al., Resistive switching in Mott insulators and correlated systems. Adv. Funct. Mater. 25, 6287–6305 (2015). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and/or supporting information.