Abstract

Background

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), one of the most lethal cancers, is driven by oncogenic KRAS mutations. Farnesyl thiosalicylic acid (FTS), also known as salirasib, is a RAS inhibitor that selectively dislodges active RAS proteins from cell membrane, inhibiting downstream signaling. FTS has demonstrated limited therapeutic efficacy in PDAC patients despite being well tolerated.

Methods

To improve the efficacy of FTS in PDAC, we performed a genome-wide CRISPR synthetic lethality screen to identify genetic targets that synergize with FTS treatment. Among the top candidates, multiple genes in the endoplasmic reticulum-associated protein degradation (ERAD) pathway were identified. The role of ERAD inhibition in enhancing the therapeutic efficacy of FTS was further investigated in pancreatic cancer cells using pharmaceutical and genetic approaches.

Results

In murine and human PDAC cells, FTS induced unfolded protein response (UPR), which was further augmented upon treatment with a chemical inhibitor of ERAD, Eeyarestatin I (EerI). Combined treatment with FTS and EerI significantly upregulated the expression of UPR marker genes and induced apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells. Furthermore, CRISPR-based genetic ablation of the key ERAD components, HRD1 and SEL1L, sensitized PDAC cells to FTS treatment.

Conclusion

Our study reveals a critical role for ERAD in therapeutic response of FTS and points to the modulation of UPR as a novel approach to improve the efficacy of FTS in PDAC treatment.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12885-021-07967-6.

Keywords: Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), Clusters of regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR), Farnesyl thiosalicylic acid (FTS), Salirasib, Endoplasmic reticulum-associated protein degradation (ERAD), Unfolded protein response (UPR)

Background

The most prevalent pancreatic malignancy, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), is among the most aggressive cancers, with a dismal prognosis, and highly refractory to most treatment options [1]. KRAS mutations have been identified as the oncogenic driver in PDAC [2]. RAS is a membrane bound GTPase that functions as a molecular switch, cycling between active GTP-bound state facilitated by guanine nucleotide exchange factors, and inactive GDP-bound state regulated by GTPase-activating proteins [3]. Upon activation of cell-surface receptors, RAS switches to the GTP-bound state to recruit and activate cytoplasmic effectors involved in a variety of signaling networks [4]. Oncogenic mutations impair the ability of KRAS to hydrolyze GTP, and lock the oncoprotein in its constitutively active GTP-bound state, leading to hyperactivation of effector signaling pathways driving tumorigenesis [5].

Given its critical function as an oncogenic driver, extensive efforts have been devoted to the development of specific RAS inhibitors [6–8]. However, the lack of binding sites for small chemical inhibitors on the RAS protein surface has hindered the efforts to directly target RAS. Furthermore, drugging RAS through the use of GTP antagonists has not been feasible due to the extremely high affinity (picomolar) to GTP and GTP abundance (millimolar) in cells. Failure to develop clinically-approved RAS inhibitors has prompted the perception that RAS proteins are “undruggable” [9]. In recent years, exciting progresses have been made in directly targeting the rare KRASG12C mutant [10–14], but not the more prevalent mutations, such as G12D, G12V, and G12R.

RAS proteins undergo a series of post-translational modifications related to their biological functions such as acetylation, ubiquitination, phosphorylation, and farnesylation among many [15]. Localization of KRAS on plasma membrane is crucial to downstream signal transduction, and farnesylation at C-terminal cysteine (CAAX motif) is essential for its localization and activation [16]. Farnesyl thiosalicylic acid (FTS), also known as salirasib, was developed as a pan-RAS inhibitor [17]. FTS mimics the C-terminal farnesyl cysteine carboxymethyl ester of all RAS isoforms and selectively dislodges active RAS proteins from cell membrane, inhibiting their biological functions [18]. Promising findings in preclinical models have prompted several clinical trials in leukemia, lung, and pancreatic cancers [19, 20]. However, FTS alone has shown only modest activity in patients despite minimal side effects [21–23], suggesting further efforts to develop FTS for the treatment of PDAC should be focused on drug combinations to enhance the therapeutic efficacy.

Combinatorial strategies, such as coupled targeting of KRAS and mitochondrial respiration pathways [24], or concomitant suppression of ERK and autophagy [25], have been proposed for PDAC treatment with the goal of achieving better therapeutic responses. The concept of synthetic lethality has been widely exploited in the development of targeted therapeutics and combination therapies. The conceptual framework posits that, two perturbations are considered synthetic lethal if either one acting alone is compatible with viability, but when combined, will lead to cell death [26, 27]. Functional genetic approaches, such as RNAi and CRISPR screens, have been employed to discover novel genetic targets of synthetic lethality and identify combination therapies [28, 29]. In particular, CRISPR-Cas9 genome-wide screens have superior efficiency and increased specificity [30, 31]. We, therefore, set out to identify genetic targets that enhance FTS efficacy in PDAC by performing a genome-wide CRISPR synthetic lethality screen. Among the top candidates, genes related to endoplasmic reticulum-associated protein degradation (ERAD) were highly enriched. Moreover, we showed that FTS induced unfolded protein response (UPR) in murine and human PDAC cells, which was further enhanced by suppression of ERAD to induce apoptosis.

Methods

Cell lines and chemical reagents

4292 murine PDAC cell line, expressing mutant KRASG12D under the control of the Tet-ON system, and p53R172H, was a generous gift from Dr. Marina Pasca di Magliano at the University of Michigan [32, 33]. 4292 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and 1 μg/ml doxycycline. Human PDAC cell lines, PANC-1 and MIA PaCa-2, were purchased from ATCC and cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. FTS, Eeyarestatin I, and GSK2606414 were purchased from Cayman Chemical.

Pooled “synthetic lethal” CRISPR screen and data analysis

The CRISPR library screen was performed following published protocols [34]. The pooled mouse CRISPR lentiviral library containing 78,637 gRNAs targeting 19,674 genes was obtained from Addgene (#73633-LV, lentiviral prep), and the screen was performed in duplicate with two independent viral infections. Briefly, 4292 cells with stable Cas9 expression were infected at low viral titers so that approximately 10% of the cells were infected. The infected cells were selected with puromycin (1 μg/ml) for 2 days. The experimental pool was treated with 100 μM FTS for 12 days. Both experimental and control pools were passaged every 3 days with at least 50 million cells per pool to ensure 500-1000X coverage. Following FTS treatment, the gRNA libraries in the cell populations were isolated by PCR amplification and identified by Hiseq. Computational analysis of the libraries was performed using MAGeCK (version 0.5.9.2). First, cutadapt (version 2.6) was used to trim primer and other technical sequences from paired-end FASTQ files with the specified options: -j 0 --maximum-length 30 --pair-filter = both -e 0.3 -g GCTTTATATATCTTGTGGAAAGGACGAAACACC…GTTTTAGAGCTAGAAATAGCAAGTTAAAATAAGGCTAGTCCGTTATCAACTTGAAAAAGT -G CCGACTCGGTGCCACTTTTTCAAGTTGATAACGGACTAGCCTTATTTTAACTTGCTATTTCTAGCTCTAAAAC…GGTGTTTCGTCCTTTCCACAAGATATATAAAGC. Second, the command, mageck count, was run under default options with the trimmed paired-end FASTQ files supplied in the arguments --fastq and --fastq-2 to collect read counts. Finally, the command, mageck mle, was run, specifying an unpaired design for the biological duplicates, 10 permutation rounds, 2500 genes for mean-variance modeling, the --remove-outliers option, median normalization, FDR p-value adjustment, and a list of the 1000 control sgRNAs in the library supplied to the --control-sgrna option. The resulting beta scores and FDR-adjusted permutation p-values were used in downstream analysis. All samples had a mapping rate of 89–90.2%, gini index (a measure of the evenness of sgRNA read counts) of 0.066–0.072, and 384–502 zero-count sgRNAs. Enrichr was used for gene ontology (GO) analysis of genes with a negative beta score and an FDR < 0.05 (n = 488 genes) [35]. The visualization tool, Clustergrammer, was used to graphically depict the top 20 GO terms (as ranked by p-value) and their associated genes.

IC50 determination and cell viability assay

Cells were seeded at the following concentrations: 4000 cells for 4292, 16,000 cells for PANC-1, 8000 cells for MIA PaCa-2 per well in 24-well plates. Drugs were added the next day in triplicates. Following 5 days of drug treatment, cell viability was assessed using the CellTiter-Glo 2.0 Cell Viability Assay (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Data analysis and calculation of the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) were carried out using GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad).

Western blot analysis

Cells were lysed on ice in CelLytic MT Cell Lysis Reagent (Sigma) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Protein concentration was determined with Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher). Protein lysates were resolved on SDS-PAGE gels and transferred to PVDF membranes [36]. The following antibodies were used for the western blot analysis: phospho-eIF2α (#9721, 1:1000), eIF2α (#9722, 1:1000), ATF4 (#11815, 1:1000), BIM (#2819, 1:1000), SYVN1 (#14773, 1:1000) from Cell Signaling Technology; phospho-PERK (Thr980) (MA5–15033, 1:1000, Thermo Fisher); SEL1L (S3699, 1:1000, Sigma); β-tubulin (10094–1-AP, 1:5000, Proteintech).

RNA extraction and quantitative real-time PCR

RNA was extracted with the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). cDNA was synthesized using the Verso cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. qPCR analysis was performed on a 7500 Real-Time PCR System using SYBR Green (Applied Biosystems). Primer sequences are available in Supplementary Table 3. Transcripts were normalized to human GAPDH or mouse UBC, and relative gene expression was determined with ddCt method as previously reported [36].

Flow cytometry

PE Annexin-V Apoptosis Detection Kit (BD Biosciences) was used to detect apoptosis following manufacturer’s instruction [36]. Briefly, cells were suspended in 100 μl of 1X binding buffer and mixed with 5 μl of PE-conjugated annexin-V and 7-AAD respectively, followed by incubation at room temperature for 15 min in the dark. The stained cells were analyzed using a BD FACS Fortessa flow cytometer (BD Bioscience). All flow cytometric data were analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star).

CRISPR sgRNA generation, transfection and single-cell sorting

For construction of sgRNA-expressing vectors, DNA oligonucleotides were annealed and cloned in BbsI-digested pSpCas9(BB)-2A-GFP (PX458) plasmid (Addgene #48138). Target sgRNA oligonucleotide sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 4. MIA PaCa-2 cells were seeded in 6-well plates at 0.5 million/well the day before transfection. PX458 empty vector or pooled sgRNA plasmids (2.5 μg/well) were transfected into MIA PaCa-2 cells using lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen). Three days after transfection, cells were collected and GFP-positive cells were sorted in 96-well plate using a BD FACS Fortessa flow cytometer (BD Bioscience).

Retrovirus packaging and transduction

Retroviral vectors for the expression of fluorescent markers were combined with pCL-10A1 retrovirus packaging vector at 1:1 ratio and transfected into HEK293FT cells using lipofectamine 3000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen). Supernatants containing the viral particles were collected at 48 h post-transfection and passed through a sterile 0.45 μm syringe filter (VWR). Wild type, SYVN1 KO1, and SEL1L KO1 cells were infected by viral supernatant supplemented with 6 μg/ml polybrene in 6-well plate by centrifugation at 1000 g for 90 min. Infected cells were selected by growing in DMEM medium containing 3 μg/ml puromycin for 2 days.

Multicolor competition assay

pBabe puro IRES-mCherry (Addgene #128038) and pBabe puro IRES-EGFP (Addgene #128037) were used for labeling. MIA PaCa-2-derived single clones labeled with mCherry (wild type) and GFP (SYVN1 KO1 or SEL1L KO1) were mixed at 1:1 ratio. Mixed cell populations were seeded in T25 flasks at 0.2 million cells per cell line. One day after seeding (D0) wells were imaged with Leica DMi8 with a 5X objective and mCherry and GFP positive cells were counted from three different images. Cells were treated with DMSO or FTS for 2 weeks. Relative cell fitness was calculated from the percentage of GFP-positive cells normalized to the D0 value.

Statistical analysis

Cell viability and apoptotic cell percentage among different treatment groups were analyzed using ANOVA with Tukey’s test. Other viability assays and transcript levels were analyzed using two-tailed student’s t test. Statistical significance of multicolor competition assay was assessed using unpaired two-sample t test. Results were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

Results

CRISPR screen identifies ERAD as a cellular process modulating FTS efficacy

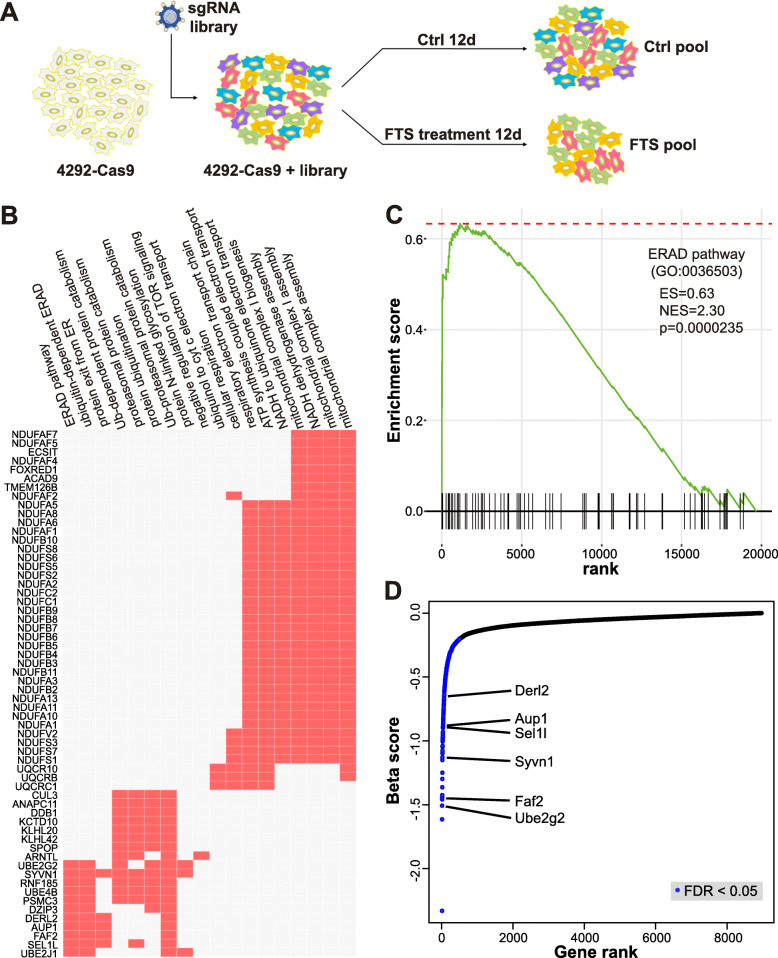

To discover potential genetic targets that modify sensitivity to FTS, we performed a genome-wide CRISPR library screen utilizing a murine pooled sgRNA library [37]. Cas9 nuclease was introduced in the murine PDAC cell line 4292 by lentiviral infection, followed by the sgRNA library, which contains 78,637 gRNAs targeting 19,674 genes. Following puromycin selection, the cell population containing the gRNA library was further expanded and split into control and FTS pools. FTS pool was treated with the drug for 12 days, while the control pool was maintained in culture. At the end of the treatment, genomic DNA from both pools was collected for PCR amplification of sgRNA libraries and further analysis of sgRNA frequency by deep-sequencing (Fig. 1a). A “beta score” was calculated for each gene to measure the degree of selection using MAGeCK’s maximum likelihood estimation algorithm (Supplementary Table 1) [38]. The beta score quantifies the effect size with negative values suggesting sgRNA depletion and positive values suggesting sgRNA enrichment [38].

Fig. 1.

CRISPR screening identifies ERAD as a target modulating the efficacy of FTS. a Basic flow of the genome-wide CRISPR screen for genes modulating FTS sensitivity. b Gene Ontology (GO) pathway analysis of genes with gRNA dropouts upon FTS treatment. c Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) showing enrichment of genes in the ERAD pathway indicated by the enrichment score and p-value. d Gene dropout rank based on beta score. Top ERAD pathway genes were labeled. Blue color depicted gene dropouts with FDR < 0.05

To identify mutations that specifically enhance FTS efficacy, we searched for sgRNAs that were further depleted (with a negative beta score) upon FTS treatment. Gene Ontology (GO) pathway analysis based on false discovery rate (FDR) adjusted p-values of less than 0.05 pointed to several pathways in regulating the FTS response, including mitochondrial respiratory chain, protein retrograde transport from ER to cytosol, and proteasome-mediated ubiquitin-dependent protein catabolic processes (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Table 2). In particular, sgRNAs targeting various ERAD-related genes, including Ube2g2, Faf2, Syvn1, Sel1l, Aup1, and Derl2, were significantly depleted from the FTS pool (Fig. 1c-d) [39, 40]. These molecules are essential components of ERAD, a process responsible for the clearance of misfolded proteins in the ER through cytosolic translocation and proteasomal degradation [41]. Retro-translocation of ERAD substrates across the ER membrane is mediated by the HRD1-SEL1L complex, representing the most conserved ERAD machinery. The E3 ligase HRD1 (encoded by Syvn1) forms a translocation channel while SEL1L functions as the adaptor protein [42, 43]. A member of Derlin family of proteins, DERL2, is an essential functional partner of HRD1-SEL1L complex [44]. Another ERAD-related protein, AUP1, recruits the E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme UBE2G2 during the ubiquitination of substrates [45]. Following retro-translocation and polyubiquitination, substrates are extracted from the ER membrane by the AAA ATPase VCP/p97 complex and transferred to the cytosolic proteasome for degradation [46, 47]. Another component, UBXD8 (encoded by Faf2) is an ER membrane-embedded recruitment factor for VCP/p97 [48]. Thus, our CRISPR screen identifies multiple key components of ERAD, pointing to ERAD as a major pathway affecting the therapeutic efficacy of FTS.

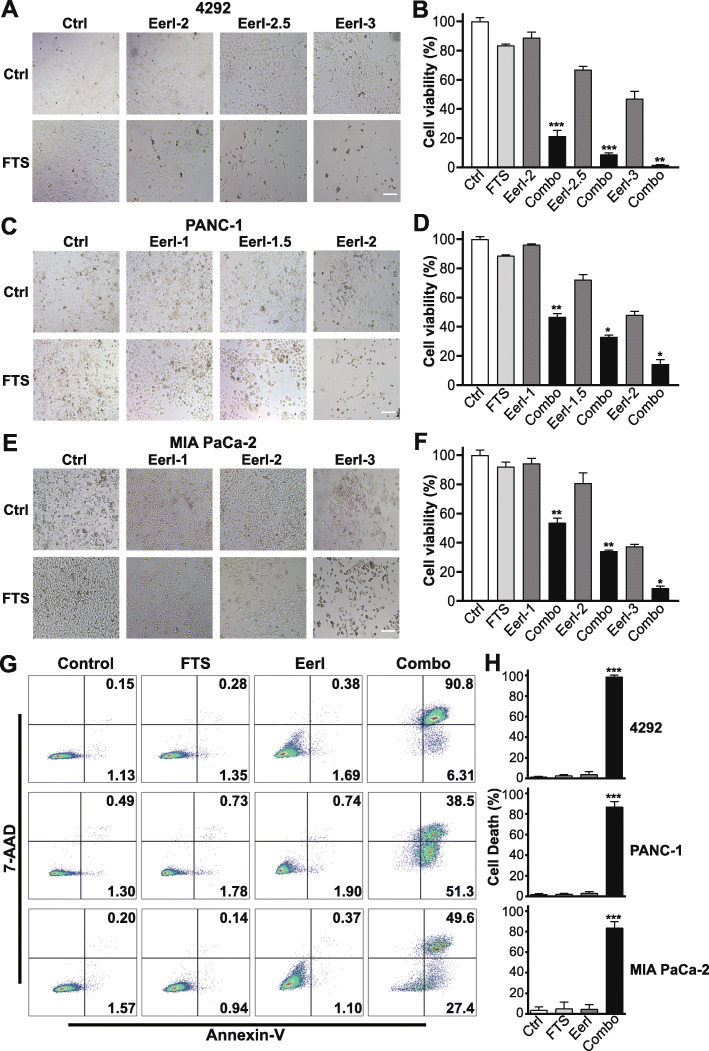

ERAD inhibition synergizes with FTS to activate ER stress and induce apoptosis

To determine whether inhibition of ERAD could synergize with FTS treatment to induce cell death in PDAC cells, we combined an ERAD inhibitor, Eeyarestatin I (EerI), with FTS. EerI acts through the inhibition of VCP/p97, which mediates the translocation of misfolded proteins from ER to cytosol for proteasomal degradation [49, 50]. We treated three PDAC cell lines (murine 4292, human PANC-1 and MIA PaCa-2) with FTS, EerI, or both for 5 days, and assessed cell survival by microscopic observation and viability assay. While FTS only modestly reduced the viability of PDAC cells, combined treatment with EerI and FTS drastically decreased cell viability (Fig. 2). Berenbaum combination index (CI) [51] showed CI values of less than 1 for all the cell lines, confirming a synergistic effect on combined treatment (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Fig. 2.

EerI synergizes with FTS to kill PDAC cells through apoptosis induction. a, c, e Bright field images (200X) of 4292, PANC-1, and MIA PaCa-2 cells treated with 100 μM FTS, EerI, or both for five days. EerI (μM) concentrations were indicated above each figure. Scale bar, 25 μm. b, d, f Relative cell viability following five days of treatment with FTS, EerI, or both. ANOVA with Tukey’s test compares the viability difference between combination and single treatments or controls. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001; data are presented as mean ± SD; n = 3). g Representative flow cytometric analysis of PDAC cell apoptosis following treatments with 100 μM FTS, EerI (3 μM for 4292, 2.5 μM for PANC-1 and MIA PaCa-2), or both for five days. Cells were stained with annexin-V and 7-AAD. Percentages of apoptotic cells were indicated in the quadrants. h PDAC cell death analysis following different treatments with Annexin V/7-AAD apoptosis assay. ANOVA with Tukey’s test compares difference treatment groups. ***P < 0.001; data presented as mean ± SD; n = 3.

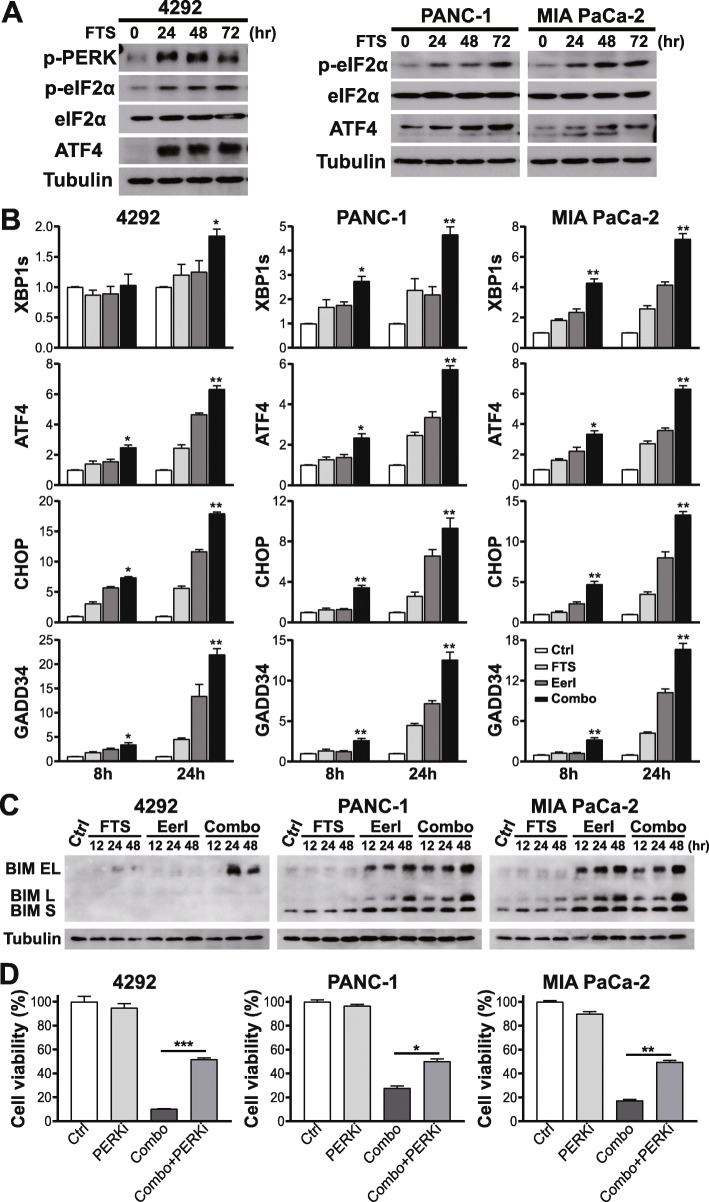

Tumor cells are exposed to intrinsic and environmental factors, such as oncogene activation, hypoxia, glucose deprivation, and lactic acidosis, which perturb protein homeostasis and lead to endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress. To relieve ER stress and restore proteostasis, tumor cells have adopted a specific stress response pathway, UPR, that includes three main branches initiated by IRE1α, PERK, and ATF6 [52]. The signaling pathways in the three branches cooperate to reduce protein translation and enhance the ER-folding capacity. Additionally, the ERAD pathway is activated to translocate and degrade the misfolded proteins accumulated in the ER. Notably, ERAD and UPR are engaged in a crosstalk, in which, UPR triggers ERAD, while impaired ERAD activates UPR [53]. FTS has been reported to induce ER stress in MYC-amplified cancer cells as indicated by upregulation of UPR markers [54]. Analysis of gene expression profiles in FTS-treated cancer cells points to the upregulation of stress response genes, such as ATF3 and ATF4 [55]. We demonstrated that inhibition of ERAD, a downstream cellular process triggered by UPR, enhanced FTS efficacy, suggesting that FTS likely induces UPR in the KRAS-driven PDAC tumor cells. Therefore, we examined UPR in these PDAC cells. Intriguingly, FTS treatment induced sustained UPR in all three PDAC cell lines, shown by increased levels of phospho-PERK (p-PERK), phospho-eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α (p-eIF2α), and ATF4 (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Fig. S2).

Fig. 3.

Activation of UPR by FTS is further enhanced upon ERAD inhibition to elicit ER stress-induced apoptosis. a Protein expression of UPR markers (p-PERK, p-eIF2α, ATF4) in PDAC cells treated with 100 μM FTS for 72 h. b Changes in transcript levels of UPR marker genes (XBP1s, ATF4, CHOP, and GADD34) following treatment with 100 μM FTS, EerI (3 μM for 4292 and MIA PaCa-2, 2 μM for PANC-1), or both for 8 and 24 h. All mRNA values were normalized to human GAPDH or mouse UBC. Two-tailed student’s t test compares transcriptional difference between combination and single treatments or control at the same timepoint, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01; data presented as mean ± SD; n = 3. c Protein expression of BIM isoforms in PDAC cells in response to treatments with FTS, EerI, or the combination for 48 h. d Pretreatment with PERKi (2.5 μM GSK2606414) for two hours partially blocked the cell death induced by the combined FTS and EerI treatment for five days. Two-tailed student’s t test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001; relative cell viability are presented as mean ± SD; n = 3

EerI was reported to induce accumulation of misfolded proteins and UPR in cancer cells by blocking ERAD [56] and/or inhibiting Sec61 complex-mediated translocation of newly synthesized chaperones from cytosol to the ER [57]. To determine the effect of combined FTS-Eer1 treatment on UPR, we examined the mRNA levels of multiple UPR marker genes. Compared to treatment with FTS or EerI alone, combined treatment elicited UPR hyperactivation through IRE1α and PERK branches, as indicated by the dramatic increase in XBP1s, ATF4, CHOP, and GADD34 transcripts (Fig. 3b) [56, 58]. Notably, ATF4/CHOP signaling, known to induce apoptotic cell death [59–61], was significantly enhanced by the combined treatment.

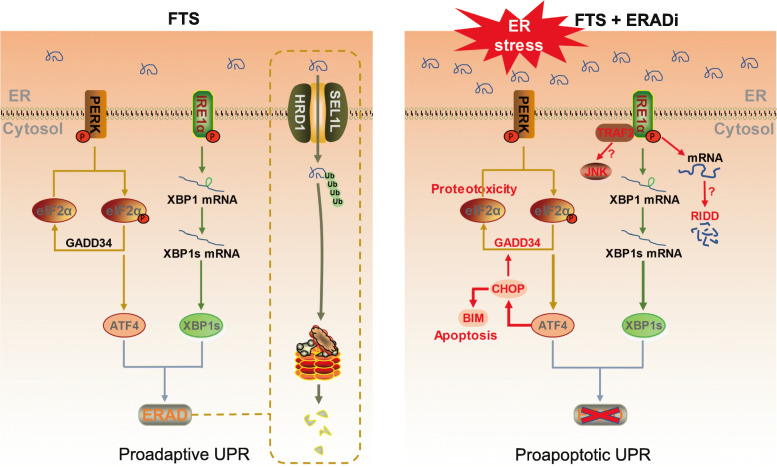

Current data support proadaptive as well as proapoptotic roles for UPR. Homeostatic UPR signaling may promote tumor progression by supporting tumor cell survival and resistance to chemotherapy and radiation therapy [62, 63]. However, in cases where ER stress remains overwhelmingly unresolved, activation of a terminal UPR program will lead to cell death [64–66]. Apoptosis following ER stress can be mediated by multiple mechanisms [67–69]. In particular, hyperactivation of the PERK/eIF2α/ATF4 pathway induces apoptosis through the regulation of proapoptotic transcription factor CHOP and Bcl-2 family proteins [70–76]. Consistent with the upregulation of ATF4/CHOP upon combined treatment with FTS and EerI, significant apoptosis was observed in murine and human PDAC cell lines as detected by the Annexin V/7-AAD apoptosis assay (Fig. 2g-h). Thus, we show that combined treatment synergizes to induce apoptosis in PDAC tumor cells. Bcl-2 homology 3 (BH3)-only proapoptotic proteins, such as BIM and NOXA, are regulated by ATF4/CHOP signaling and mediate ER stress-induced apoptosis [56, 73, 77]. Indeed, BIM protein was significantly upregulated upon combination treatment in PDAC cells (Fig. 3c, Supplementary Fig. S2). Pretreatment of PDAC cells with a PERK inhibitor (PERKi), GSK2606414, partially blocked the induction of cell death by the combined treatment (Fig. 3d), suggesting that activation of PERK/eIF2α/ATF4/CHOP proapoptotic pathway contributes to the synergistic cell death.

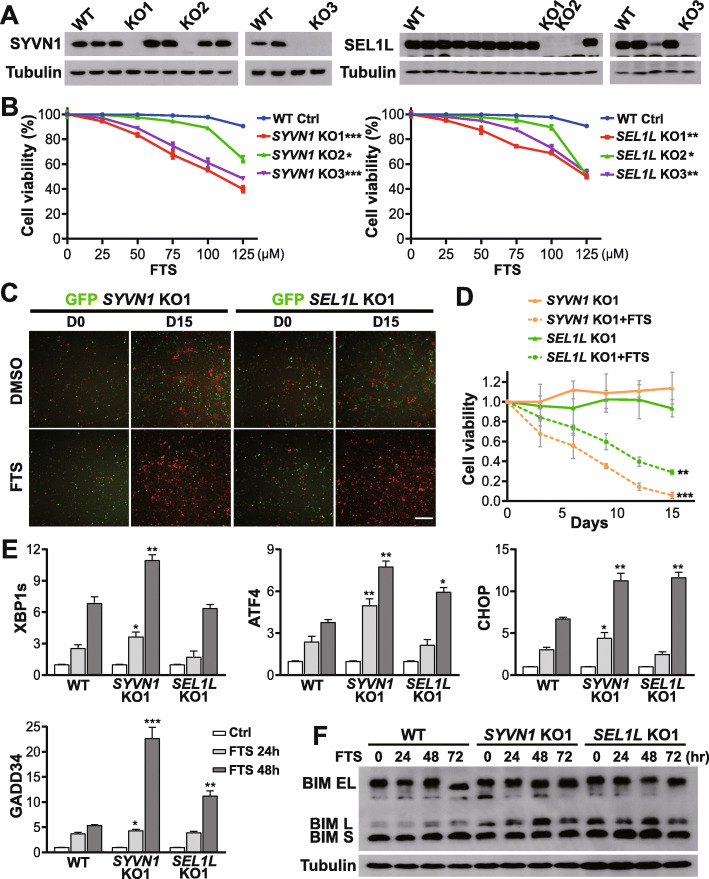

Genetic knockout of SYVN1 and SEL1L sensitizes PDAC cells to FTS treatment

HRD1-SEL1L complex is an essential component of ERAD pathway. HRD1, encoded by SYVN1 gene, is an E3 ubiquitin ligase involved in processing of misfolded proteins. SEL1L is an HRD1 adaptor protein, and indispensable for ERAD [78]. To demonstrate genetically that inhibition of ERAD indeed enhances the FTS therapeutic efficacy, we knocked out SYVN1 and SEL1L genes in MIA PaCa-2 cells utilizing the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Complete loss of SYVN1 and SEL1L expression was confirmed by Western blot analysis and genomic DNA sequencing (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Fig. S3–4). We tested three individual knockout (KO) clones for each gene (Fig. 4a) and demonstrated that these clones exhibited increased sensitivity to FTS treatment (Fig. 4b). To further examine the drug sensitivity in the knockout clones, we performed a multicolor competition assay (MCA), in which the mCherry-labeled wild type control clone was co-cultured with GFP-labeled SYVN1 KO1 or SEL1L KO1 clones at a 1:1 ratio, and treated with either vehicle or FTS for 2 weeks [79]. Compared to the non-treated population, the FTS-treated cells showed predominance of mCherry-labeled wild type cells, indicating increased vulnerability of SYVN1 and SEL1L deficient cells (Fig. 4c-d). Thus, PDAC cells with genetic defects in the ERAD machinery are more sensitive to FTS treatment.

Fig. 4.

Knockout of SYVN1 and SEL1L sensitizes PDAC cells to FTS treatment through proapoptotic UPR. a Validation of SYVN1 and SEL1L CRISPR knockouts by western blot analysis of single clones derived from MIA PaCa-2 cells. b Relative cell viability of wild type control and SYVN1 and SEL1L KO clones treated with 25-125 μM FTS for five days. Two-tailed student’s t test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001; data are presented as mean ± SD; n = 3. c Representative images of multicolor competition assay (50X) in the presence of 125 μM FTS. Scale bar, 100 μm. d Quantitative analysis of MCA for SYVN1 KO1 and SEL1L KO1 cell following FTS treatment. Unpaired two-sample t test, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001; data are presented as mean ± SD; n = 3. e Changes in transcript levels of UPR markers (XBP1s, ATF4, CHOP, and GADD34) in wild type control, SYVN1 KO1 and SEL1L KO1 cells following treatment with 100 μM FTS for 48 h. All mRNA values were normalized to human GAPDH. Two-tailed student’s t test compares transcriptional difference between KO clones and WT control at the same timepoint, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001; data are presented as mean ± SD; n = 3. (F) BIM protein expression in wild type control, SYVN1 KO1, and SEL1L KO1 cells following treatment with 100 μM FTS for 72 h

In SYVN1 and SEL1L KO cells, increased sensitivity to FTS coincided with increased level of ER stress. SYVN1 KO1 and SEL1L KO1 cells treated with FTS showed dramatic upregulation of UPR marker genes, including XBP1s, ATF4, CHOP, and GADD34 (Fig. 4e), suggesting that cells with genetic defects in ERAD are more prone to proapoptotic UPR. Furthermore, expression of the pro-apoptotic protein BIM, in particular the BIM L isoform, was strongly induced in these clones following FTS treatment (Fig. 4f, Supplementary Fig. S4), pointing to the induction of apoptosis by the hyperactive ER stress. In summary, using both pharmacological and genetic approaches, we demonstrate that targeting ERAD improves the therapeutic efficacy of FTS through increased activation of ER stress and the subsequent induction of apoptosis (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Schematic model of the synthetic lethal effects of FTS and ERAD inhibition. Following FTS treatment, UPR is drastically enhanced by ERAD inhibition, eliciting unresolved ER stress and apoptosis

Discussion

Using a genome-wide CRISPR synthetic lethal screen, we have identified ERAD as a key cellular target to enhance FTS efficacy. We show that FTS treatment induces ER stress, which is further amplified by inhibition of ERAD, resulting in synergistic induction of apoptosis in PDAC cells (Fig. 5). In pancreatic cancer, a highly desmoplastic stroma leads to hypoxia and nutrients deprivation [80]. Therefore, pancreatic cancer is more vulnerable to the induction of ER stress. Consequently, therapeutic options that promote ER stress and activate apoptosis may be exploited for PDAC treatment. We have identified one such therapeutic approach by combining FTS and ERAD inhibitors, the efficacy of which, may be examined in vivo for the treatment of PDAC. Similarly, FTS may be combined with other ER stress inducers, such as proteasome inhibitors [81], to generate severe ER stress and tumor cell apoptosis. Combined use of FTS and gemcitabine has been empirically examined for clinical pancreatic cancer treatment [22]. Our study on the mechanisms of drug synergy will provide new options for future PDAC treatments. Recent studies suggest that resolution of ER stress leads to tumor proliferation and formation of metastases from the disseminated PDAC cells [82]. Under constitutive ER stress, metastatic cells may remain dormant and fail to develop overt tumor masses. In this light, the combined use of FTS and ERAD inhibitors, may serve as a novel therapeutic option against metastatic PDAC.

Regulation of tumor cell survival following ER stress is complicated [62, 63, 83]. Our study argues that FTS-induced ER stress is relieved by activation of proadaptive UPR and ERAD, while ERAD inhibition through induction of ER stress, leads to hyperactivation of PERK/eIF2α/ATF4/CHOP/BIM proapoptotic pathway and massive cell death. Additionally, activation of IRE1α signaling pathway can recruit TRAF2 and JNK to induce cell death, or contribute to apoptosis through regulation of IRE1-dependent decay (RIDD) [84, 85]. On the other hand, proapoptotic mediators, such as ATF4 and CHOP, have been shown to activate multiple autophagy genes as a pro-survival response to counteract the ER stress [86]. Thus, cell fate control following ER stress may depend on the fine-tuning of UPR, and the crosstalk between UPR, ERAD, autophagy, and apoptosis [53, 87, 88].

Our CRISPR screen has identified additional targets that may enhance the FTS therapeutic efficacy. In a transgenic mouse model of pancreatic cancer, cell survival following KRAS ablation depends on mitochondrial function, especially oxidative phosphorylation [35]. In this regard, our study has identified several genes encoding mitochondria complex I subunits, mitochondria complex II subunits, as well as the mitochondrial iron-sulfur cluster assembly machinery [89–91]. Additionally, we identified Sptlc1, Sptlc2, and Kdsr genes, encoding the serine palmitoyltransferase (SPT) and 3-ketodihydrosphingosine reductase (KDHR), among the top candidates. SPT and KDHR serve as essential enzymes in the initial steps of de novo sphingolipid synthesis [92]. As sphingolipids are structural components of plasma membrane, inhibition of sphingolipid metabolism may mislocalize oncogenic KRAS and abolish its signaling [93]. Our findings suggest that multiple approaches to dislodge KRAS from plasma membrane may be combined to abrogate oncogenic KRAS signaling. Other candidate genetic targets in our screen are involved in apoptosis, mTOR signaling, and fatty acids and selenoprotein metabolism [94, 95]. Further studies will examine the role of these genetic targets in modulating FTS efficacy in the treatment of PDAC.

Conclusion

Using both genetic and pharmacological approaches, we have demonstrated a critical role for ERAD in enhancing the FTS therapeutic response. The combined use of FTS and ERAD inhibitors may be an effective therapeutic option for the treatment of PDAC.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplementary Fig. S1. Combination indexes show synergistic effect between EerI and FTS (A) Berenbaum combination index (CI). CI value of lower than 1 indicates synergy. (B) Cell viability tests presented as mean ± SD. Data analysis and calculation of IC50 was performed using GraphPad Prism 8. (C) The CI values of FTS and EerI in 4292, PANC-1, and MIA PaCa-2 cells, indicating synergistic effect. Supplementary Fig. S2. Original images of the Western blot presented in Fig. 3a and c. Supplementary Fig. S3. Validation of SYVN1 and SEL1L CRISPR knockouts by PCR and Sanger sequencing (A) Map of SYVN1 and SEL1L and their respective sgRNAs. Half-arrows indicate the primer sets used to for PCR amplification. Primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 5. (B) PCR amplicons of wild type control and the knockouts using primer sets depicted in S3A. (C) Sanger sequencing of SYVN1 exon3 PCR products. In SYVN1 KO1, one allele shows 40 nt deletion between the targeting sites of sg2 and sg3, and mutations/frameshift around sg3 targeting site in the other allele. (D) Sanger sequencing of SEL1L 1F-3R PCR product from SEL1L KO1 validating a 106 nucleotide deletion between the targeting sites of sg1 and sg3. Supplementary Fig. S4. Original images of the Western blot presented in Fig. 4a and f

Additional file 2: Supplementary Table 1. Genes rank based on their beta scores in ascending order from the FTS screen. Supplementary Table 2. GO pathway analysis of top candidate genes from FTS screen. Supplementary Table 3. The sequences of primers used in qPCR assay. Supplementary Table 4. sgRNA oligonucleotide sequences for SYVN1/SEL1L knockout. Supplementary Table 5. PCR primers used to validate genomic knockout of SYVN1 and SEL1L

Acknowledgments

The authors greatly appreciate Dr. Marina Pasca di Magliano for generously providing the murine pancreatic cancer cell line (4292).

Abbreviations

- PDAC

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- CRISPR

Clusters of regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats

- FTS

Farnesyl thiosalicylic acid

- EerI

Eeyarestatin I

- UPR

Unfolded protein response

- ERAD

Endoplasmic reticulum-associated protein degradation

- IC50

Half-maximal inhibitory concentration

- qPCR

Quantitative real-time PCR

- GFP

Green fluorescent protein

- MCA

Multicolor competition assay

- GO

Gene Ontology

- GSEA

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis

- CI

Combination index

- p-eIF2α

Phospho-eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α

- p-PERK

Phospho-PERK

- PERKi

PERK inhibitor

- KO

Knockout

- SPT

Serine palmitoyltransferase

- KDHR

3-ketodihydrosphingosine reductase

Authors’ contributions

R.D., N.G.A, and Y.L. developed the study. R.D. performed the molecular and cell biology experiments. N.G.A. carried out the CRISPR FTS synthetic lethal screens. D.K.S. analyzed the CRISPR screening data. R.D. and Y.L. wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by NIH/NCI K22CA207598 (Y.L.), CPRIT RP200472 (Y.L.), and NIH GM008042 (D.K.S.; UCLA-Caltech Medical Scientist Training Program).

Availability of data and materials

CRISPR screen data is available at GEO accession number GSE162065.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Consent for publication is not needed as no patient data are included in this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kamisawa T, Wood LD, Itoi T, Takaori K. Pancreatic cancer. Lancet. 2016;388(10039):73–85. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00141-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Waters AM, Der CJ. KRAS: The Critical Driver and Therapeutic Target for Pancreatic Cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2018;8(9):a031435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Bos JL, Rehmann H, Wittinghofer A. GEFs and GAPs: critical elements in the control of small G proteins. Cell. 2007;129(5):865–877. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pylayeva-Gupta Y, Grabocka E, Bar-Sagi D. RAS oncogenes: weaving a tumorigenic web. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(11):761–774. doi: 10.1038/nrc3106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vigil D, Cherfils J, Rossman KL, Der CJ. Ras superfamily GEFs and GAPs: validated and tractable targets for cancer therapy? Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10(12):842–857. doi: 10.1038/nrc2960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cox AD, Fesik SW, Kimmelman AC, Luo J, Der CJ. Drugging the undruggable RAS: Mission possible? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13(11):828–851. doi: 10.1038/nrd4389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh H, Longo DL, Chabner BA. Improving prospects for targeting RAS. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(31):3650–3659. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marín-Ramos NI, Ortega-Gutiérrez S, López-Rodríguez ML. Blocking Ras inhibition as an antitumor strategy. Semin Cancer Biol. 2019;54:91–100. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2018.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stephen AG, Esposito D, Bagni RK, McCormick F. Dragging ras back in the ring. Cancer Cell. 2014;25(3):272–281. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ostrem JM, Peters U, Sos ML, Wells JA, Shokat KM. K-Ras(G12C) inhibitors allosterically control GTP affinity and effector interactions. Nature. 2013;503(7477):548–551. doi: 10.1038/nature12796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lim SM, Westover KD, Ficarro SB, Harrison RA, Choi HG, Pacold ME, Carrasco M, Hunter J, Kim ND, Xie T, et al. Therapeutic targeting of oncogenic K-Ras by a covalent catalytic site inhibitor. Angew Chem Int Ed Eng. 2014;53(1):199–204. doi: 10.1002/anie.201307387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lito P, Solomon M, Li LS, Hansen R, Rosen N. Allele-specific inhibitors inactivate mutant KRAS G12C by a trapping mechanism. Science. 2016;351(6273):604–608. doi: 10.1126/science.aad6204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janes MR, Zhang J, Li LS, Hansen R, Peters U, Guo X, Chen Y, Babbar A, Firdaus SJ, Darjania L, et al. Targeting KRAS Mutant Cancers with a Covalent G12C-Specific Inhibitor. Cell. 2018;172(3):578–589.e517. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Canon J, Rex K, Saiki AY, Mohr C, Cooke K, Bagal D, Gaida K, Holt T, Knutson CG, Koppada N, et al. The clinical KRAS(G12C) inhibitor AMG 510 drives anti-tumour immunity. Nature. 2019;575(7781):217–223. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1694-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahearn I, Zhou M, Philips MR. Posttranslational Modifications of RAS Proteins. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2018;8(11):a031484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Wang M, Casey PJ. Protein prenylation: unique fats make their mark on biology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2016;17(2):110–122. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2015.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marom M, Haklai R, Ben-Baruch G, Marciano D, Egozi Y, Kloog Y. Selective inhibition of Ras-dependent cell growth by farnesylthiosalisylic acid. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(38):22263–22270. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.38.22263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rotblat B, Ehrlich M, Haklai R, Kloog Y. The Ras inhibitor farnesylthiosalicylic acid (Salirasib) disrupts the spatiotemporal localization of active Ras: a potential treatment for cancer. Methods Enzymol. 2008;439:467–489. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)00432-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zundelevich A, Elad-Sfadia G, Haklai R, Kloog Y. Suppression of lung cancer tumor growth in a nude mouse model by the Ras inhibitor salirasib (farnesylthiosalicylic acid) Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6(6):1765–1773. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haklai R, Elad-Sfadia G, Egozi Y, Kloog Y. Orally administered FTS (salirasib) inhibits human pancreatic tumor growth in nude mice. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2008;61(1):89–96. doi: 10.1007/s00280-007-0451-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Riely GJ, Johnson ML, Medina C, Rizvi NA, Miller VA, Kris MG, Pietanza MC, Azzoli CG, Krug LM, Pao W, et al. A phase II trial of Salirasib in patients with lung adenocarcinomas with KRAS mutations. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6(8):1435–1437. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318223c099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laheru D, Shah P, Rajeshkumar NV, McAllister F, Taylor G, Goldsweig H, Le DT, Donehower R, Jimeno A, Linden S, et al. Integrated preclinical and clinical development of S-trans, trans-Farnesylthiosalicylic acid (FTS, Salirasib) in pancreatic cancer. Investig New Drugs. 2012;30(6):2391–2399. doi: 10.1007/s10637-012-9818-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Badar T, Cortes JE, Ravandi F, O'Brien S, Verstovsek S, Garcia-Manero G, Kantarjian H, Borthakur G. Phase I study of S-trans, trans-farnesylthiosalicylic acid (salirasib), a novel oral RAS inhibitor in patients with refractory hematologic malignancies. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2015;15(7):433–438.e432. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2015.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Viale A, Pettazzoni P, Lyssiotis CA, Ying H, Sánchez N, Marchesini M, Carugo A, Green T, Seth S, Giuliani V, et al. Oncogene ablation-resistant pancreatic cancer cells depend on mitochondrial function. Nature. 2014;514(7524):628–632. doi: 10.1038/nature13611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bryant KL, Stalnecker CA, Zeitouni D, Klomp JE, Peng S, Tikunov AP, Gunda V, Pierobon M, Waters AM, George SD, et al. Combination of ERK and autophagy inhibition as a treatment approach for pancreatic cancer. Nat Med. 2019;25(4):628–640. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0368-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaelin WG., Jr The concept of synthetic lethality in the context of anticancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5(9):689–698. doi: 10.1038/nrc1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Topatana W, Juengpanich S, Li S, Cao J, Hu J, Lee J, Suliyanto K, Ma D, Zhang B, Chen M, et al. Advances in synthetic lethality for cancer therapy: cellular mechanism and clinical translation. J Hematol Oncol. 2020;13(1):118. doi: 10.1186/s13045-020-00956-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chan SM, Thomas D, Corces-Zimmerman MR, Xavy S, Rastogi S, Hong WJ, Zhao F, Medeiros BC, Tyvoll DA, Majeti R. Isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 and 2 mutations induce BCL-2 dependence in acute myeloid leukemia. Nat Med. 2015;21(2):178–184. doi: 10.1038/nm.3788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang C, Jin H, Gao D, Lieftink C, Evers B, Jin G, Xue Z, Wang L, Beijersbergen RL, Qin W, et al. Phospho-ERK is a biomarker of response to a synthetic lethal drug combination of sorafenib and MEK inhibition in liver cancer. J Hepatol. 2018;69(5):1057–1065. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shalem O, Sanjana NE, Hartenian E, Shi X, Scott DA, Mikkelson T, Heckl D, Ebert BL, Root DE, Doench JG, et al. Genome-scale CRISPR-Cas9 knockout screening in human cells. Science. 2014;343(6166):84–87. doi: 10.1126/science.1247005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Evers B, Jastrzebski K, Heijmans JP, Grernrum W, Beijersbergen RL, Bernards R. CRISPR knockout screening outperforms shRNA and CRISPRi in identifying essential genes. Nat Biotechnol. 2016;34(6):631–633. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Collins MA, Bednar F, Zhang Y, Brisset JC, Galbán S, Galbán CJ, Rakshit S, Flannagan KS, Adsay NV, Pasca di Magliano M. Oncogenic Kras is required for both the initiation and maintenance of pancreatic cancer in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(2):639–653. doi: 10.1172/JCI59227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Collins MA, Brisset JC, Zhang Y, Bednar F, Pierre J, Heist KA, Galbán CJ, Galbán S, di Magliano MP. Metastatic pancreatic cancer is dependent on oncogenic Kras in mice. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e49707. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Joung J, Konermann S, Gootenberg JS, Abudayyeh OO, Platt RJ, Brigham MD, Sanjana NE, Zhang F. Genome-scale CRISPR-Cas9 knockout and transcriptional activation screening. Nat Protoc. 2017;12(4):828–863. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2017.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuleshov MV, Jones MR, Rouillard AD, Fernandez NF, Duan Q, Wang Z, Koplev S, Jenkins SL, Jagodnik KM, Lachmann A, et al. Enrichr: a comprehensive gene set enrichment analysis web server 2016 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(W1):W90–W97. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu Y, Azizian NG, Dou Y, Pham LV, Li Y. Simultaneous targeting of XPO1 and BCL2 as an effective treatment strategy for double-hit lymphoma. J Hematol Oncol. 2019;12(1):119. doi: 10.1186/s13045-019-0803-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Doench JG, Fusi N, Sullender M, Hegde M, Vaimberg EW, Donovan KF, Smith I, Tothova Z, Wilen C, Orchard R, et al. Optimized sgRNA design to maximize activity and minimize off-target effects of CRISPR-Cas9. Nat Biotechnol. 2016;34(2):184–191. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li W, Köster J, Xu H, Chen CH, Xiao T, Liu JS, Brown M, Liu XS. Quality control, modeling, and visualization of CRISPR screens with MAGeCK-VISPR. Genome Biol. 2015;16:281. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0843-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Christianson JC, Olzmann JA, Shaler TA, Sowa ME, Bennett EJ, Richter CM, Tyler RE, Greenblatt EJ, Harper JW, Kopito RR. Defining human ERAD networks through an integrative mapping strategy. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;14(1):93–105. doi: 10.1038/ncb2383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leto DE, Morgens DW, Zhang L, Walczak CP, Elias JE, Bassik MC, Kopito RR. Genome-wide CRISPR Analysis Identifies Substrate-Specific Conjugation Modules in ER-Associated Degradation. Mol Cell. 2019;73(2):377–389.e311. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Berner N, Reutter KR, Wolf DH. Protein quality control of the endoplasmic reticulum and ubiquitin-proteasome-triggered degradation of aberrant proteins: yeast pioneers the path. Annu Rev Biochem. 2018;87:751–782. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-062917-012749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kikkert M, Doolman R, Dai M, Avner R, Hassink G, van Voorden S, Thanedar S, Roitelman J, Chau V, Wiertz E. Human HRD1 is an E3 ubiquitin ligase involved in degradation of proteins from the endoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(5):3525–3534. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307453200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vasic V, Denkert N, Schmidt CC, Riedel D, Stein A, Meinecke M. Hrd1 forms the retrotranslocation pore regulated by auto-ubiquitination and binding of misfolded proteins. Nat Cell Biol. 2020;22(3):274–281. doi: 10.1038/s41556-020-0473-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang CH, Hsiao HT, Chu YR, Ye Y, Chen X. Derlin2 protein facilitates HRD1-mediated retro-translocation of sonic hedgehog at the endoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(35):25330–25339. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.455212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Klemm EJ, Spooner E, Ploegh HL. Dual role of ancient ubiquitous protein 1 (AUP1) in lipid droplet accumulation and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) protein quality control. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(43):37602–37614. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.284794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Qi L, Tsai B, Arvan P. New insights into the physiological role of endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation. Trends Cell Biol. 2017;27(6):430–440. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2016.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu X, Rapoport TA. Mechanistic insights into ER-associated protein degradation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2018;53:22–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2018.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schuberth C, Buchberger A. UBX domain proteins: major regulators of the AAA ATPase Cdc48/p97. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65(15):2360–2371. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8072-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang Q, Li L, Ye Y. Inhibition of p97-dependent protein degradation by Eeyarestatin I. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(12):7445–7454. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708347200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang Q, Shinkre BA, Lee JG, Weniger MA, Liu Y, Chen W, Wiestner A, Trenkle WC, Ye Y. The ERAD inhibitor Eeyarestatin I is a bifunctional compound with a membrane-binding domain and a p97/VCP inhibitory group. PLoS One. 2010;5(11):e15479. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Menachem A, Bodner O, Pastor J, Raz A, Kloog Y. Inhibition of malignant thyroid carcinoma cell proliferation by Ras and galectin-3 inhibitors. Cell Death Dis. 2015;1:15047. doi: 10.1038/cddiscovery.2015.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Karagöz GE, Acosta-Alvear D, Walter P. The Unfolded Protein Response: Detecting and Responding to Fluctuations in the Protein-Folding Capacity of the Endoplasmic Reticulum. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2019;11(9):a033886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Hwang J, Qi L. Quality control in the endoplasmic reticulum: crosstalk between ERAD and UPR pathways. Trends Biochem Sci. 2018;43(8):593–605. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2018.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yaari-Stark S, Shaked M, Nevo-Caspi Y, Jacob-Hircsh J, Shamir R, Rechavi G, Kloog Y. Ras inhibits endoplasmic reticulum stress in human cancer cells with amplified Myc. Int J Cancer. 2010;126(10):2268–2281. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Blum R, Elkon R, Yaari S, Zundelevich A, Jacob-Hirsch J, Rechavi G, Shamir R, Kloog Y. Gene expression signature of human cancer cell lines treated with the ras inhibitor salirasib (S-farnesylthiosalicylic acid) Cancer Res. 2007;67(7):3320–3328. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang Q, Mora-Jensen H, Weniger MA, Perez-Galan P, Wolford C, Hai T, Ron D, Chen W, Trenkle W, Wiestner A, et al. ERAD inhibitors integrate ER stress with an epigenetic mechanism to activate BH3-only protein NOXA in cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(7):2200–2205. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807611106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cross BC, McKibbin C, Callan AC, Roboti P, Piacenti M, Rabu C, Wilson CM, Whitehead R, Flitsch SL, Pool MR, et al. Eeyarestatin I inhibits Sec61-mediated protein translocation at the endoplasmic reticulum. J Cell Sci. 2009;122(Pt 23):4393–4400. doi: 10.1242/jcs.054494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ron D, Walter P. Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8(7):519–529. doi: 10.1038/nrm2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Han J, Back SH, Hur J, Lin YH, Gildersleeve R, Shan J, Yuan CL, Krokowski D, Wang S, Hatzoglou M, et al. ER-stress-induced transcriptional regulation increases protein synthesis leading to cell death. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15(5):481–490. doi: 10.1038/ncb2738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hetz C, Papa FR. The unfolded protein response and cell fate control. Mol Cell. 2018;69(2):169–181. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Almanza A, Carlesso A, Chintha C, Creedican S, Doultsinos D, Leuzzi B, Luís A, McCarthy N, Montibeller L, More S, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress signalling - from basic mechanisms to clinical applications. FEBS J. 2019;286(2):241–278. doi: 10.1111/febs.14608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Urra H, Dufey E, Avril T, Chevet E, Hetz C. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and the hallmarks of Cancer. Trends Cancer. 2016;2(5):252–262. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2016.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cubillos-Ruiz JR, Bettigole SE, Glimcher LH. Tumorigenic and immunosuppressive effects of endoplasmic reticulum stress in Cancer. Cell. 2017;168(4):692–706. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Oakes SA. Endoplasmic reticulum stress signaling in Cancer cells. Am J Pathol. 2020;190(5):934–946. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2020.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hetz C. The unfolded protein response: controlling cell fate decisions under ER stress and beyond. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13(2):89–102. doi: 10.1038/nrm3270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Urra H, Dufey E, Lisbona F, Rojas-Rivera D, Hetz C. When ER stress reaches a dead end. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1833(12):3507–3517. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sano R, Reed JC. ER stress-induced cell death mechanisms. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1833(12):3460–3470. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.06.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tabas I, Ron D. Integrating the mechanisms of apoptosis induced by endoplasmic reticulum stress. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13(3):184–190. doi: 10.1038/ncb0311-184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Iurlaro R, Muñoz-Pinedo C. Cell death induced by endoplasmic reticulum stress. FEBS J. 2016;283(14):2640–2652. doi: 10.1111/febs.13598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.McCullough KD, Martindale JL, Klotz LO, Aw TY, Holbrook NJ. Gadd153 sensitizes cells to endoplasmic reticulum stress by down-regulating Bcl2 and perturbing the cellular redox state. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21(4):1249–1259. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.4.1249-1259.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Oyadomari S, Mori M. Roles of CHOP/GADD153 in endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell Death Differ. 2004;11(4):381–389. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li G, Mongillo M, Chin KT, Harding H, Ron D, Marks AR, Tabas I. Role of ERO1-alpha-mediated stimulation of inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptor activity in endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 2009;186(6):783–792. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200904060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Puthalakath H, O'Reilly LA, Gunn P, Lee L, Kelly PN, Huntington ND, Hughes PD, Michalak EM, McKimm-Breschkin J, Motoyama N, et al. ER stress triggers apoptosis by activating BH3-only protein Bim. Cell. 2007;129(7):1337–1349. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Marciniak SJ, Yun CY, Oyadomari S, Novoa I, Zhang Y, Jungreis R, Nagata K, Harding HP, Ron D. CHOP induces death by promoting protein synthesis and oxidation in the stressed endoplasmic reticulum. Genes Dev. 2004;18(24):3066–3077. doi: 10.1101/gad.1250704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yamaguchi H, Wang HG. CHOP is involved in endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis by enhancing DR5 expression in human carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(44):45495–45502. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406933200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ohoka N, Yoshii S, Hattori T, Onozaki K, Hayashi H. TRB3, a novel ER stress-inducible gene, is induced via ATF4-CHOP pathway and is involved in cell death. EMBO J. 2005;24(6):1243–1255. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pihán P, Carreras-Sureda A, Hetz C. BCL-2 family: integrating stress responses at the ER to control cell demise. Cell Death Differ. 2017;24(9):1478–1487. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2017.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sun S, Shi G, Han X, Francisco AB, Ji Y, Mendonça N, Liu X, Locasale JW, Simpson KW, Duhamel GE, et al. Sel1L is indispensable for mammalian endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation, endoplasmic reticulum homeostasis, and survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(5):E582–E591. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1318114111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.MacLeod G, Bozek DA, Rajakulendran N, Monteiro V, Ahmadi M, Steinhart Z, Kushida MM, Yu H, Coutinho FJ, Cavalli FMG, et al. Genome-Wide CRISPR-Cas9 Screens Expose Genetic Vulnerabilities and Mechanisms of Temozolomide Sensitivity in Glioblastoma Stem Cells. Cell Rep. 2019;27(3):971–986.e979. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Neesse A, Michl P, Frese KK, Feig C, Cook N, Jacobetz MA, Lolkema MP, Buchholz M, Olive KP, Gress TM, et al. Stromal biology and therapy in pancreatic cancer. Gut. 2011;60(6):861–868. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.226092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lamothe B, Wierda WG, Keating MJ, Gandhi V. Carfilzomib triggers cell death in chronic lymphocytic leukemia by inducing Proapoptotic and endoplasmic reticulum stress responses. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(18):4712–4726. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pommier A, Anaparthy N, Memos N, Kelley ZL, Gouronnec A, Yan R, Auffray C, Albrengues J, Egeblad M, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, et al. Unresolved endoplasmic reticulum stress engenders immune-resistant, latent pancreatic cancer metastases. Science (New York, NY). 2018;360(6394):eaao4908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 83.Wang M, Kaufman RJ. The impact of the endoplasmic reticulum protein-folding environment on cancer development. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14(9):581–597. doi: 10.1038/nrc3800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Han D, Lerner AG, Vande Walle L, Upton JP, Xu W, Hagen A, Backes BJ, Oakes SA, Papa FR. IRE1alpha kinase activation modes control alternate endoribonuclease outputs to determine divergent cell fates. Cell. 2009;138(3):562–575. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Urano F, Wang X, Bertolotti A, Zhang Y, Chung P, Harding HP, Ron D. Coupling of stress in the ER to activation of JNK protein kinases by transmembrane protein kinase IRE1. Science. 2000;287(5453):664–666. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5453.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.B'Chir W, Maurin AC, Carraro V, Averous J, Jousse C, Muranishi Y, Parry L, Stepien G, Fafournoux P, Bruhat A. The eIF2α/ATF4 pathway is essential for stress-induced autophagy gene expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(16):7683–7699. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Senft D, Ronai ZA. UPR, autophagy, and mitochondria crosstalk underlies the ER stress response. Trends Biochem Sci. 2015;40(3):141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bhardwaj M, Leli NM, Koumenis C, Amaravadi RK. Regulation of autophagy by canonical and non-canonical ER stress responses. Semin Cancer Biol. 2020;66:116–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 89.Sharma LK, Lu J, Bai Y. Mitochondrial respiratory complex I: structure, function and implication in human diseases. Curr Med Chem. 2009;16(10):1266–1277. doi: 10.2174/092986709787846578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kluckova K, Bezawork-Geleta A, Rohlena J, Dong L, Neuzil J. Mitochondrial complex II, a novel target for anti-cancer agents. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1827(5):552–564. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sheftel AD, Wilbrecht C, Stehling O, Niggemeyer B, Elsässer HP, Mühlenhoff U, Lill R. The human mitochondrial ISCA1, ISCA2, and IBA57 proteins are required for [4Fe-4S] protein maturation. Mol Biol Cell. 2012;23(7):1157–1166. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e11-09-0772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Gault CR, Obeid LM, Hannun YA. An overview of sphingolipid metabolism: from synthesis to breakdown. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;688:1–23. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-6741-1_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.van der Hoeven D, Cho KJ, Zhou Y, Ma X, Chen W, Naji A, Montufar-Solis D, Zuo Y, Kovar SE, Levental KR, et al. Sphingomyelin Metabolism Is a Regulator of K-Ras Function. Mol Cell Biol. 2018;38(3):e00373–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 94.Yoo MH, Xu XM, Carlson BA, Gladyshev VN, Hatfield DL. Thioredoxin reductase 1 deficiency reverses tumor phenotype and tumorigenicity of lung carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(19):13005–13008. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600012200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Padanad MS, Konstantinidou G, Venkateswaran N, Melegari M, Rindhe S, Mitsche M, Yang C, Batten K, Huffman KE, Liu J, et al. Fatty acid oxidation mediated by acyl-CoA Synthetase long chain 3 is required for mutant KRAS lung tumorigenesis. Cell Rep. 2016;16(6):1614–1628. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Supplementary Fig. S1. Combination indexes show synergistic effect between EerI and FTS (A) Berenbaum combination index (CI). CI value of lower than 1 indicates synergy. (B) Cell viability tests presented as mean ± SD. Data analysis and calculation of IC50 was performed using GraphPad Prism 8. (C) The CI values of FTS and EerI in 4292, PANC-1, and MIA PaCa-2 cells, indicating synergistic effect. Supplementary Fig. S2. Original images of the Western blot presented in Fig. 3a and c. Supplementary Fig. S3. Validation of SYVN1 and SEL1L CRISPR knockouts by PCR and Sanger sequencing (A) Map of SYVN1 and SEL1L and their respective sgRNAs. Half-arrows indicate the primer sets used to for PCR amplification. Primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 5. (B) PCR amplicons of wild type control and the knockouts using primer sets depicted in S3A. (C) Sanger sequencing of SYVN1 exon3 PCR products. In SYVN1 KO1, one allele shows 40 nt deletion between the targeting sites of sg2 and sg3, and mutations/frameshift around sg3 targeting site in the other allele. (D) Sanger sequencing of SEL1L 1F-3R PCR product from SEL1L KO1 validating a 106 nucleotide deletion between the targeting sites of sg1 and sg3. Supplementary Fig. S4. Original images of the Western blot presented in Fig. 4a and f

Additional file 2: Supplementary Table 1. Genes rank based on their beta scores in ascending order from the FTS screen. Supplementary Table 2. GO pathway analysis of top candidate genes from FTS screen. Supplementary Table 3. The sequences of primers used in qPCR assay. Supplementary Table 4. sgRNA oligonucleotide sequences for SYVN1/SEL1L knockout. Supplementary Table 5. PCR primers used to validate genomic knockout of SYVN1 and SEL1L

Data Availability Statement

CRISPR screen data is available at GEO accession number GSE162065.