Influenza A virus is the major cause of influenza, a respiratory disease in humans and animals. Different from most other RNA viruses, the transcription and replication of IAV occur in the cell nucleus. Therefore, the vRNPs must be imported into the nucleus for viral transcription and replication, which requires participation of host proteins. However, the mechanisms of the IAV-host interactions involved in nuclear import remain poorly understood. Here, we identified eEF1D as a novel inhibitor for the influenza virus life cycle. Importantly, eEF1D impaired the interaction between NP and importin α5 and the interaction between PB1 and RanBP5, which impeded the nuclear import of vRNP. Our studies not only reveal the molecular mechanisms of the nuclear import of IAV vRNP but also provide potential anti-influenza targets for antiviral development.

KEYWORDS: influenza A virus, vRNP, PA-PB1 heterodimer, NP, eEF1D

ABSTRACT

The viral ribonucleoprotein (vRNP) of the influenza A virus (IAV) is responsible for the viral RNA transcription and replication in the nucleus, and its functions rely on host factors. Previous studies have indicated that eukaryotic translation elongation factor 1 delta (eEF1D) may associate with RNP subunits, but its roles in IAV replication are unclear. Herein, we showed that eEF1D was an inhibitor of IAV replication because knockout of eEF1D resulted in a significant increase in virus yield. eEF1D interacted with RNP subunits polymerase acidic protein (PA), polymerase basic 1 (PB1), polymerase basic 2 (PB2), and also with nucleoprotein (NP) in an RNA-dependent manner. Further studies revealed that eEF1D impeded the nuclear import of NP and PA-PB1 heterodimer of IAV, thereby suppressing the vRNP assembly, viral polymerase activity, and viral RNA synthesis. Together, our studies demonstrate eEF1D negatively regulating the IAV replication by inhibition of the nuclear import of RNP subunits, which not only uncovers a novel role of eEF1D in IAV replication but also provides new insights into the mechanisms of nuclear import of vRNP proteins.

IMPORTANCE Influenza A virus is the major cause of influenza, a respiratory disease in humans and animals. Different from most other RNA viruses, the transcription and replication of IAV occur in the cell nucleus. Therefore, the vRNPs must be imported into the nucleus for viral transcription and replication, which requires participation of host proteins. However, the mechanisms of the IAV-host interactions involved in nuclear import remain poorly understood. Here, we identified eEF1D as a novel inhibitor for the influenza virus life cycle. Importantly, eEF1D impaired the interaction between NP and importin α5 and the interaction between PB1 and RanBP5, which impeded the nuclear import of vRNP. Our studies not only reveal the molecular mechanisms of the nuclear import of IAV vRNP but also provide potential anti-influenza targets for antiviral development.

INTRODUCTION

The influenza virus belongs to the Orthomyxovirus family. The genome of influenza A virus (IAV) is eight-segmented and single-stranded RNAs of negative polarity and exists as a viral ribonucleoprotein (vRNP) complex consisting of multiple copies of the nucleoprotein (NP) and viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) that includes polymerase basic 1 (PB1), polymerase basic 2 (PB2), and polymerase acidic protein (PA). NP binds stoichiometrically to the viral genome (approximately 1 NP molecule per 24 nucleotides) without sequence specificity (1–4). Simultaneously, NP homo-oligomerization occurs to form mini-vRNP complexes for viral transcription and replication (5, 6). The RdRp synthesizes three species of RNA, including viral RNA (vRNA), cRNA, and mRNA, for viral transcription and replication (7, 8). Within a heterocomplex formed by three polymerase subunits, PB2 employs its cap-binding domain to binding to m7G on host RNA (9, 10); then, PA utilizes its endonuclease domain to cleave 10 to 13 nucleotides downstream of the 5′ cap structure of the host RNA (11, 12) as a primer to initiate transcription of viral RNA (13). PB1 has been shown to be essential for synthesized RNA elongation (14, 15). As a core protein of polymerase complex, PB1 interacts with the C-terminal region of PA through its N-terminal region, while the C-terminal region of PB1 is bound to the N-terminal region of PB2. NP interacts with PB1 and PB2 but not PA (16).

To complete viral transcription and replication, the vRNP complexes utilize the nuclear localization signals (NLSs) of NP for its nuclear import through the importin α (IMPα)-IMPβ1 pathway (17–21). So far, two NLSs have been identified in the NP, including an unconventional NLS in the N terminus (NLS1; residues 3 to 13) (20, 22) and a bipartite NLS (NLS2; residues 198 to 216) (23). The major signal essential for the nuclear import of vRNPs is an unconventional NLS (NLS1; residues 3 to 13) despite that it binds to the NLS-binding domain of importin α weakly (24, 25). Influenza A viral RNA binds NP and enters into the nucleus, relying on IMPα-IMPβ1 heterodimers (26). It has been proposed that the new synthesized PB2 is transported into the nucleus alone, while PA and PB1 have to form heterodimers and enter into the nucleus with the assistance of RanBP5 (21, 27, 28). PB2 has been shown to be transported into the nucleus via the classic IMPα-IMPβ1 pathway, and it is mediated by its nuclear localization sequences, amino acids from 448 to 496 and from 736 to 739 (29, 30).

It has been reported that some cellular proteins regulate IAV replication by affecting the nuclear import of vRNP complex or vRNP subunits, such as phospholipid scramblase 1 (PLSCR1), Moloney leukemia virus 10 (MOV10), HAX1, and Hsp40/DnaJB1 (31–34). However, the detailed mechanisms of how host proteins regulate the nuclear import of vRNPs are not fully elucidated, and whether other cellular proteins participate in the nuclear import of viral proteins and what role they play in this process need further exploration. Numerous host proteins have been identified as vRNP subunit-interacting proteins, which have potential roles in the IAV life cycle (35–38). Eukaryotic translation elongation factor 1 delta (eEF1D/eEF1Bδ), a subunit of the eEF1 complex, has been identified as the host factor binding to PA by the yeast two-hybrid method in previous studies (35, 39). The eEF1 complex consists of eEF1A1 and eEF1B complex, while the eEF1B complex is composed of eEF1B2, eEF1D, and eEF1G (40, 41). eEF1A1 is one of the modulators of influenza viral replication among many host factors (42). eEF1D stimulates the exchange of GDP and GTP bound to eEF1A1 in the translation elongation process, and it mediates protein synthesis by assisting eEF1A1 to recruit aminoacylated tRNA molecules to the acceptor site on the small ribosomal subunit (43–45). eEF1G promotes A/WSN/1933 (WSN H1N1) virus replication and is required for viral protein expression (46). Interestingly, eEF1G can bind to eEF1D (47). However, as a protein of the eEF1 complex, the specific role of eEF1D in the influenza virus or other virus life cycle has not been extensively investigated. In this study, we identified eEF1D as a negative regulator for IAV replication. Our studies further demonstrated that eEF1D associated with PA, PB1, PB2, and also with NP but in an RNA-dependent manner, and it impeded the nuclear import of NP by interfering with the interaction between NP and importin α5. Additionally, we also found that eEF1D effectively disrupted the subcellular location of PA-PB1 heterodimers by weakening the interaction between PB1 and RanBP5. Consequently, the subsequent influenza virus life stages, including viral transcription and replication and vRNP nuclear export, were delayed by eEF1D, which finally resulted in inhibition of virus replication. Thus, we propose that eEF1D is a novel IAV restriction factor that reduces virus replication by inhibiting the nuclear import of NP and PA-PB1 heterodimers.

RESULTS

eEF1D negatively modulates the propagation of IAV.

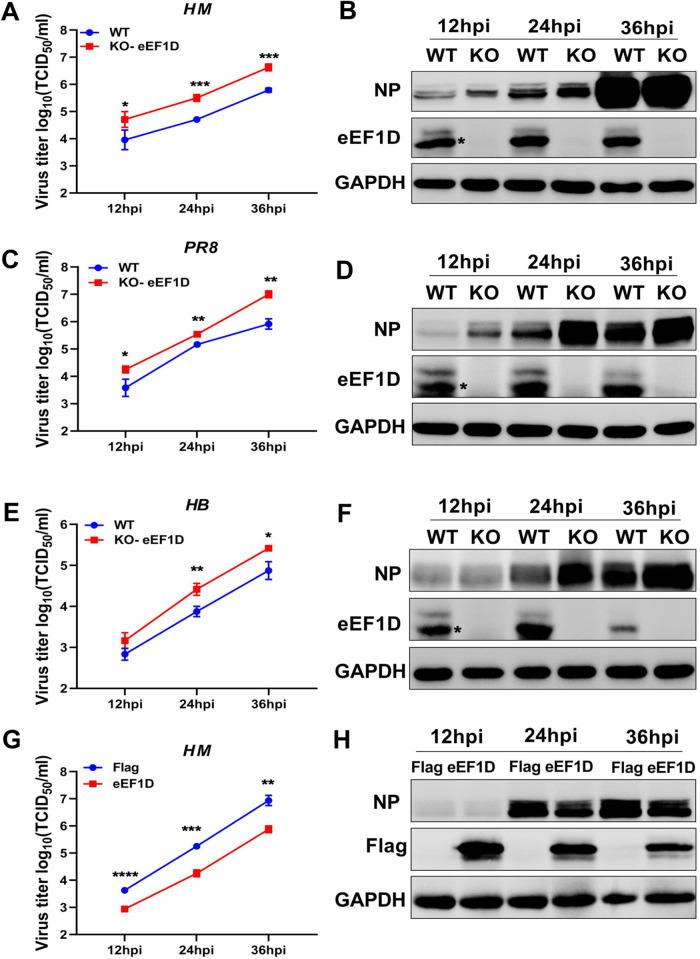

Previous studies have shown that eEF1D had the potential to interact with all of the RNP constituents (35, 36). To determine the relationships of IAV with eEF1D, we established the eEF1D knockout A549 cells by using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. The knockout of eEF1D was confirmed by sequencing the cell genome and Western blotting at the protein level (Fig. S1A in the supplemental material). To examine the effect of eEF1D on virus replication, the growth kinetics of A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 (PR8 H1N1), A/duck/Hubei/Hangmei01/2006 (HM H5N1), and A/swine/Hubei/221/2016 (HB H1N1) viruses in eEF1D knockout and wild-type A549 cells were compared. Samples were collected from the infected cells at 12, 24, and 36 hours postinfection (hpi), and the virus titers were determined by 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID50) assay on MDCK cells. As shown in Fig. 1A, C, and E, the viral loads of PR8 H1N1, HM H5N1, and HB H1N1 virus were significantly increased in eEF1D knockout cells compared to wild-type cells. To further confirm the impact of eEF1D in IAV replication, we carried out Western blotting to detect viral NP in the infected cells. The results showed that more viral NP was found in the eEF1D knockout cells than in wild-type A549 cells infected with each respective virus (Fig. 1B, D, and F), and eEF1D protein was also efficiently knocked out. Moreover, the virus titer of the HM H5N1 virus was dramatically decreased in A549 cells that overexpressed eEF1D compared with that in control cells. The results of Western blotting also showed less viral NP detected in eEF1D-overexpressed cells than in control cells infected with the HM H5N1 virus (Fig. 1G and H). To confirm the above findings, we reconstituted eEF1D plasmid Flag-eEF1D (T) by the synonymous mutation and transfected Flag-eEF1D (T) into knockout (KO)-eEF1D A549 cells, following infection with PR8 H1N1 virus (multiplicity of infection [MOI], 0.1) at 12 hpi. IAV NP protein expression and virus titer significantly reduced after transfection of Flag-eEF1D (T) into the KO-eEF1D, which were demonstrated by both Western blotting and TCID50 assays (Fig. S1B). Taken together, we conclude that eEF1D is a negative modulator of IAV replication.

FIG 1.

eEF1D suppresses influenza A virus replication. (A to F) Effect of eEF1D knocked out on IAV replication. KO-eEF1D A549 cells were obtained by using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. WT-A549 cells and KO-eEF1D A549 cells were infected with PR8 H1N1 virus (MOI, 0.01), HM H5N1 virus (MOI, 0.01), or HB H1N1 virus (MOI, 0.1). Cell supernatants and lysates were harvested at 12 hpi, 24 hpi, and 36 hpi. Virus titers were determined by TCID50 assay on MDCK cells, as shown in panels A, C, and E. eEF1D protein expression and viral proteins expression were detected by Western blotting, as shown in panels B, D, and F (mean ± SD of three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; two-tailed Student's t test). (G and H) Effect of eEF1D overexpressed on IAV replication. A549 cells were transfected with Flag-eEF1D or vector as negative control for 24 h followed by infection with HM H5N1 virus (MOI, 0.01). Cell supernatants and lysates were harvested at 12 hpi, 24 hpi, and 36 hpi. Virus titers were determined by TCID50 assay on MDCK cells (mean ± SD of three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; two-tailed Student's t test).

To examine whether eEF1D specifically regulated IAV replication, we explored the effect of eEF1D on vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) virus. VSV is an RNA virus that replicates in the cytoplasm of infected cells. Results showed that eEF1D knockout strongly inhibited virus replication of a recombinant (VSV-green fluorescent protein [GFP]), which was evidenced by fewer GFP signals (Fig. S2A), and less GFP protein and viral RNA of VSV were detected than those detected in wild-type cells (Fig. S2B and C). These data indicate that eEF1D plays a different role in regulating virus replication of VSV.

eEF1D binds to IAV RNP subunits.

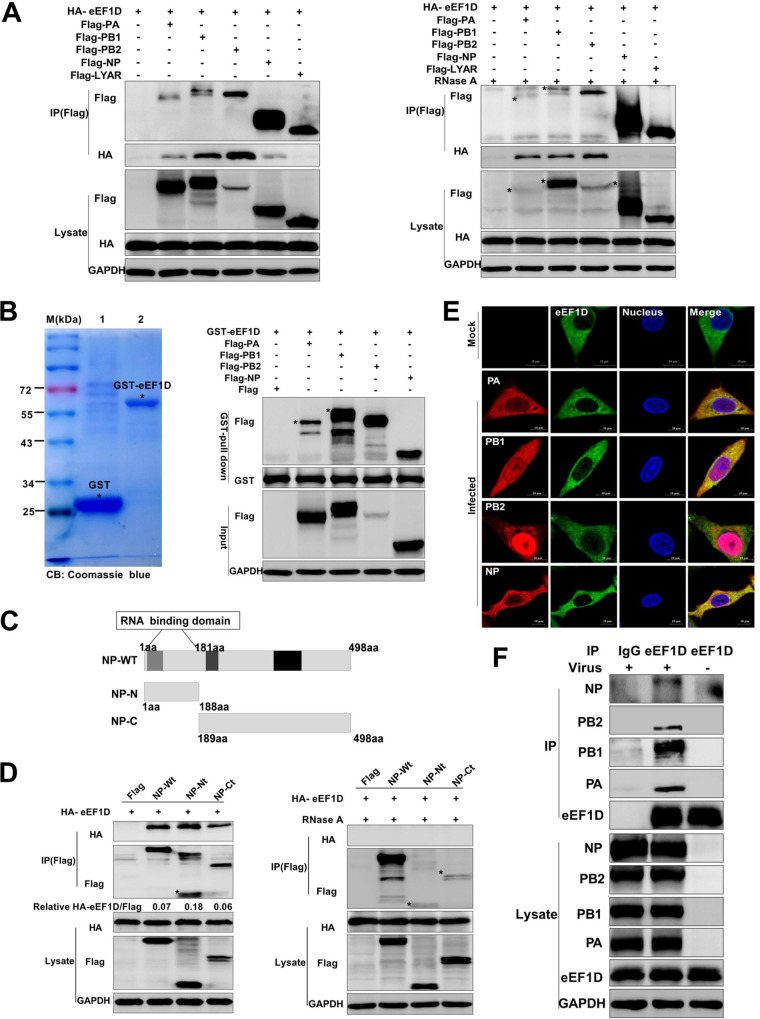

To determine the associations of eEF1D and RNP subunits, Flag-PA, Flag-PB1, Flag-PB2, or Flag-NP and hemagglutinin (HA)-eEF1D were cotransfected in HEK293T cells; then, coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) was performed at 24 h posttransfection. Results showed that eEF1D was coprecipitated with PA, PB1, PB2, and NP but not with the Flag vector and a negative-control Flag-LYAR, indicating that eEF1D interacted with all the components of RNP under transfection (Fig. 2A). Since all the RNP subunits were the RNA-binding proteins, we also performed the same co-IP assay under RNase A treatment. Results showed that HA-eEF1D was still coprecipitated with PA, PB1, and PB2, but not with NP and Flag-LYAR under the RNase A treatment (Fig. 2A), suggesting that eEF1D bound to NP in an RNA-dependent manner. The interactions of PA, PB1, PB2, or NP with eEF1D were further confirmed by using a glutathione S-transferase (GST) pulldown assay. Results showed that the purified GST-eEF1D was detected by Coomassie blue staining (Fig. 2B) and that Flag-PA, Flag-PB1, Flag-PB2, and Flag-NP expressed in HEK293T cells were pulled down by GST-eEF1D but not by the Flag vector (Fig. 2B). Moreover, endogenous eEF1D was also coprecipitated by the PA, PB1, PB2, and NP in PR8 H1N1 virus-infected HEK293T (12 hpi) cells using an anti-eEF1D mouse antibody (Fig. 2F). All these results demonstrate interactions between eEF1D and RNP components during IAV infection.

FIG 2.

Interactions between eEF1D and RNP subunits. (A) HEK293T cells were cotransfected with HA-eEF1D and Flag-PA, Flag-PB1, Flag-PB2,Flag-NP, or Flag-LYAR followed by lysing at 24 h posttransfection. Cell lysates were treated with RNase A (100 U) at 37°C for 1 h or no treatment before being mixed together. The co-IP assay was carried out using an anti-Flag antibody followed by Western blotting. (B) GST pulldown assay of purified GST-eEF1D and lysates of HEK293T cells expressing Flag-PA, Flag-PB1, Flag-PB2, or Flag-NP. Purified GST (lane 1) and GST-eEF1D (lane 2) proteins were detected by using Coomassie blue (CB) staining. (C) Schematic diagram of the NP truncated segments. (D) HEK293T cells in 6-well plates were cotransfected with empty vector, NP-Wt, NP-Nt, or NP-Ct, along with HA-eEF1D using Lipofectamine 2000. At 24 h posttransfection, the cells were lysed, and the collected lysates were untreated or treated with the RNase A (100 U) at 37°C for 1 h. The co-IP assay using an anti-Flag antibody followed by Western blot analyses. (E) Colocalization of endogenous eEF1D and RNP components in infected cells. A549 cells were mock infected or infected with the PR8 H1N1 virus (MOI, 2) for 12 hpi, and confocal microscopy was performed using an anti-eEF1D mouse antibody (green) and anti-PA, anti-PB1, anti-PB2, and anti-NP rabbit antibody (red). DAPI was used to stain for the nucleus (blue). Samples were examined with a confocal microscope (LSM 880; Zeiss). Images are representative of three independent experiments. Scale bar, 10 μM. (F) Interactions between endogenous eEF1D and RNP components during infection. HEK293T cells in 10-cm dishes were infected and mock infected with the PR8 H1N1 virus (MOI, 2) for 12 hpi. The HEK293T cells were lysed by 500 μl IP lysis buffer and immunoprecipitated using an anti-eEF1D mouse antibody or mouse control IgG.

To further validate the interaction of eEF1D with IAV RNP subunits, HA-eEF1D and either Flag-PA, Flag-PB1, Flag-PB2, or Flag-NP were cotransfected in HeLa cells, and an indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA) was carried out to detect their spatial distribution. The results showed that eEF1D localized in the cytoplasm when it expressed alone (Fig. S3B). PA and PB1 both localized in the cytoplasm and the nucleus when they expressed alone, while PB2 and NP predominantly localized in the nucleus (Fig. S3A). In cotransfected cells, the colocalization between eEF1D and PA, PB1, or NP in the cytoplasm was detected (Fig. S3B). Interestingly, the distribution of NP in the cytoplasm was increased when coexpressed with eEF1D, indicating eEF1D might affect the nuclear distribution of NP. However, the distribution of PA, PB1, and PB2 did not change when coexpressed with eEF1D (Fig. S3B). The endogenous colocalizations between eEF1D and RNP components were also examined by using immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy. The subcellular location of endogenous eEF1D did not change in the PR8 H1N1 virus-infected A549 cells at 12 hpi compared with the subcellular location of eEF1D in uninfected cells, while eEF1D colocalized with PA, PB1, PB2, and NP in the cytoplasm (Fig. 2E).

It has been reported that the RNA-binding domain of NP was 1 to 180 amino acids, which was an important but not essential RNA-binding activity of NP (48, 49). To elucidate the mechanism of interaction between NP and eEF1D, we generated two truncated NP segments, NP-Nt (RNA-binding domain, N terminus) and NP-Ct (C terminus) as depicted in Fig. 2C and determined their interactions with HA-eEF1D. Interestingly, HA-eEF1D could bind to both N terminus and C terminus of NP without RNase A treatment, and the interaction with the N terminus of NP was the strongest among NP, NP-Nt, and NP-Ct (Fig. 2D). Most likely, some amino acid residues at the C terminus of NP were also associated with NP RNA binding despite that the main RNA-binding domain was located in the N terminus of NP (50), so we also determined the interactions of HA-eEF1D with Flag-NP-Nt and Flag-NP-Ct under RNase A treatment. Results showed that HA-eEF1D lost the ability to bind to both Flag-NP-Nt and Flag-NP-Ct after RNase A treatment, just like Flag-NP wild type (Wt) (Fig. 2D). We also found that RNase A treatment also disrupted the interaction between eEF1D and NP under virus infection (Fig. S4A), which further verified the association between eEF1D and NP was mediated by RNAs. To further confirm that the interaction between NP and eEF1D is mediated by RNAs, we also employed fluorescence in situ hybridization using Quasar 570 (red)-labeled vRNA-specific probes targeting the M gene in combination with immunofluorescence (IF) (fluorescent in situ hybridization [FISH]/IF) to detect the colocalization between eEF1D and NP or vRNA. The results of confocal microscopy showed that the vRNA probe could colocalize with NP of PR8 virus in the cytoplasm at 8 hpi in infected cells, and no vRNA probe was detected in mock-infected cells and VSV-GFP-infected cells. Furthermore, eEF1D was obviously observed to colocalize with NP and vRNA in the cytoplasm in IAV-infected cells at 8 hpi (Fig. S4B).Taken together, these results demonstrate that eEF1D binds to all IAV RNP subunits and interacts with NP in an RNA-dependent manner.

eEF1D disrupts the nucleocytoplasmic distribution of IAV vRNP.

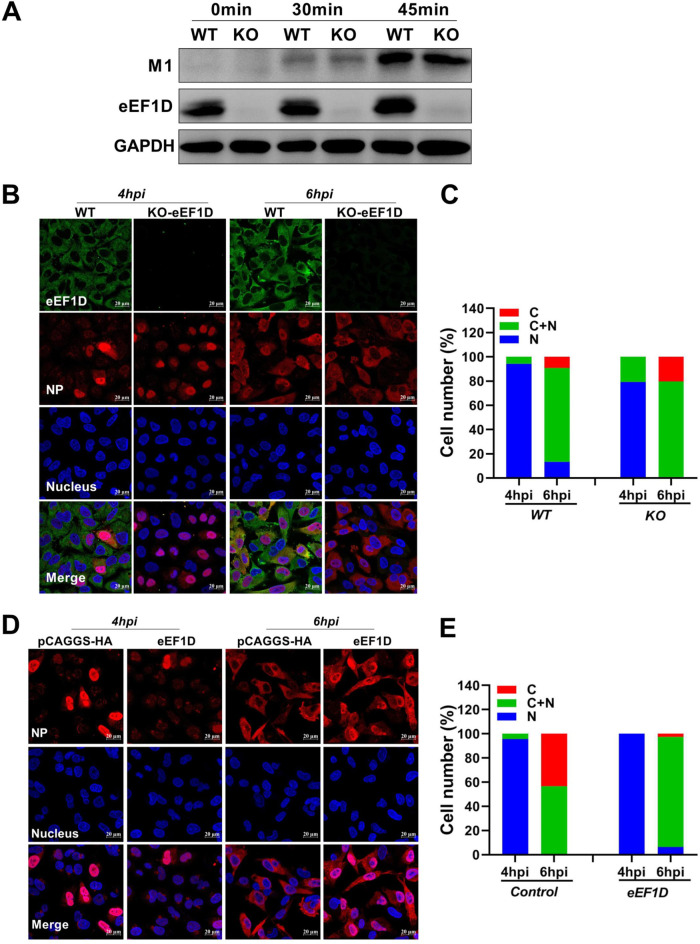

To examine the effect of eEF1D on the virus life cycle, the internalization of IAV, a process that occurs earlier than nuclear import, was studied by detecting the marker M1 of internalization using Western blot analysis. Results showed that the level of IAV internalization in KO-eEF1D cells was similar to that in wild-type A549 cells infected with the PR8 H1N1 virus at 0, 30, and 45 min, indicating that eEF1D could not affect the internalization of IAV (Fig. 3A).

FIG 3.

eEF1D affects the nucleocytoplasmic distribution of vRNP. (A) Effect of eEF1D on IAV internalization. WT-A549 cells or KO-eEF1D A549 cells were incubated with PR8 H1N1 virus at an MOI of 10 for 0, 30, and 45 min (at 37°C) without trypsin in the medium. Then, cells were washed with PBS-HCl (pH 1.3) to remove attached virions from the surface and lysed for Western blotting. (B) Localization of the NP proteins in PR8-infected WT-A549 cells and KO-eEF1D A549 cells. WT-A549 cells and KO-eEF1D A549 cells were infected with PR8 H1N1 at an MOI of 5. At 4 and 6 hpi, cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained with rabbit anti-NP (red), mouse anti-eEF1D (green), and DAPI (blue). (D) Localization of the NP proteins in PR8-infected control cells and eEF1D-overexpressed cells. Coverslips coated with A549 cells were cotransfected vector (pCAGGS-HA) or eEF1D. At 24 h posttransfection, cells were infected with PR8 virus at an MOI of 5. At 4 and 6 hpi, cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained with rabbit anti-NP (red) and DAPI (blue). (C and E) Quantitative analysis of NP localization in infected cells. At least 100 cells in each group were scored. N, predominantly nuclear; N+C, nuclear and cytoplasmic; C, predominantly cytoplasmic.

Next, we performed a time course experiment to monitor the distribution of NP in both eEF1D knockout and wild-type A549 cells. In PR8-infected WT-cells, vRNPs could be detected in the nucleus at 4 hpi, but few cells were infected (Fig. 3B and C); the vRNPs distributed in the cytoplasm as well as in the nucleus at 6 hpi (Fig. 3B and C). In contrast, in PR8-infected eEF1D knockout cells, most cells were infected, and vRNP was predominantly located in the nucleus at 4 hpi; more vRNPs were exported from the nucleus than in WT cells at 6 hpi (Fig. 3B and C). We further analyzed the localization of vRNPs in eEF1D-overexpressed cells. Results showed that vRNPs were mainly detected in the nuclei of infected cells without eEF1D overexpression, while cells were barely infected with overexpression of eEF1D at 4 hpi (Fig. 3D and E). At 6 hpi, the localization of vRNPs in the cytoplasm had increased significantly in control cells, while the vRNPs localized simultaneously at both the edge of the nucleus and the cytoplasm in eEF1D-overexpressed cells (Fig. 3D and E). These results collectively indicate that eEF1D inhibits the nuclear import of vRNPs, leading to retardation of the virus life cycle.

eEF1D inhibits the nuclear import of vRNP.

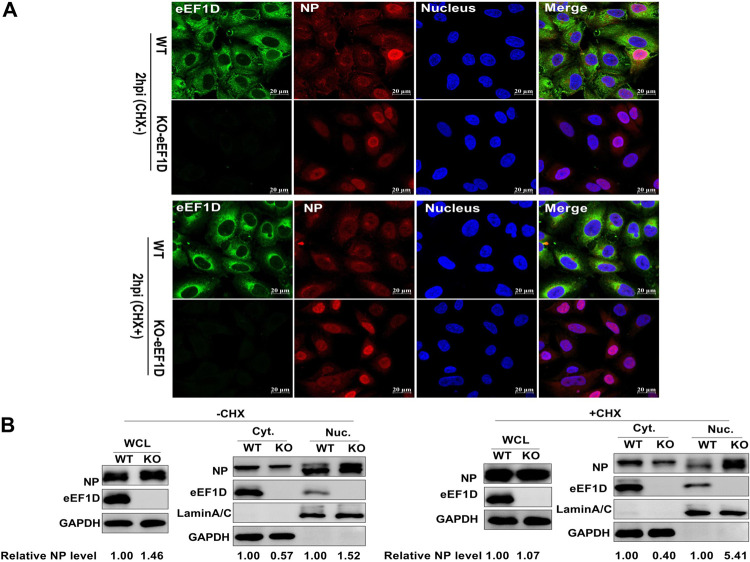

Since eEF1D interacted with NP and impeded its nuclear import and the nuclear transport of vRNP was predominantly mediated by NP (3, 22), eEF1D might regulate the nuclear import of vRNP during virus infection. Immunofluorescence assays were performed in wild-type A549 cells or KO-eEF1D A549 cells. These cells were infected with PR8 H1N1 virus in the absence or the presence of cycloheximide (CHX) for 2 h. The results showed that NP entered the nucleus in some wild-type cells without treatment of CHX, while no NP was detected in the nucleus in wild-type cells treated with CHX (Fig. 4A). This might be due to CHX inhibition of protein synthesis, and IAV cannot synthesize new viral proteins. Interestingly, nuclear localization of NP was significantly increased in knockout eEF1D cells, regardless of CHX treatment or not. We then validated the inhibitory effect of eEF1D on the nuclear import of NP with cellular fractionation and Western blot analysis. Consistently, the cytoplasmic localization of NP was shown to be significantly reduced in knockout eEF1D cells in contrast to the wild-type cells, regardless of the presence or absence of CHX. The purity of fractions was confirmed by immunoblotting of lamin A/C (a nuclear marker) and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (a cytoplasmic marker). The results, using grayscale analysis by ImageJ software, showed that the relative NP protein levels in the nucleus were also remarkably raised when eEF1D was knocked out (Fig. 4B). Meanwhile, the analysis results of whole-cell lysis were further showed that the relative protein levels of NP were promoted in knockout eEF1D cells without CHX treatment (Fig. 4B), illustrating that the viral protein synthesis was increased after eEF1D was knocked out. Taken together, these results indicate that eEF1D impedes nuclear import of vRNP.

FIG 4.

Knockout of endogenous eEF1D facilitates nuclear import of vRNPs. (A) Increased translocation of NP to nuclear in eEF1D knockout cells during infection using confocal microscopy. WT-A549 cells and KO-eEF1D A549 cells were infected with PR8 H1N1 virus (MOI, 10) at the same time. Cells were fixed at 2 h postinfection with CHX or without CHX treatment followed by immunostaining the NP (red), eEF1D (green), and nucleus (blue). The images were acquired under a confocal microscope with ×63 oil lens. Scale bar, 20 μM. For these experiments, fluorescence was examined with a confocal microscope (LSM 880; Zeiss). Images are representative of three independent experiments. (B) Western blot analysis of the distribution of NP in the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions in virus-infected WT- and KO-eEF1D cells. WT-A549 and KO-eEF1D A549 cells were infected with PR8 H1N1 virus (MOI = 10) at the same time. Cells were harvested at 2 hpi and subjected to cellular fraction and Western blotting. Western densitometry analysis was performed using ImageJ. Lamin A/C and GAPDH were used as a loading control for nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions, respectively. The relative NP levels (NP/GAPDH or lamin A/C) are shown at the bottom of panel B. The relative expression levels of NP (NP/GAPDH) were also detected in the whole-cell lysates (WCLs).

eEF1D blocks the nuclear import of viral NP and PA-PB1 heterodimer.

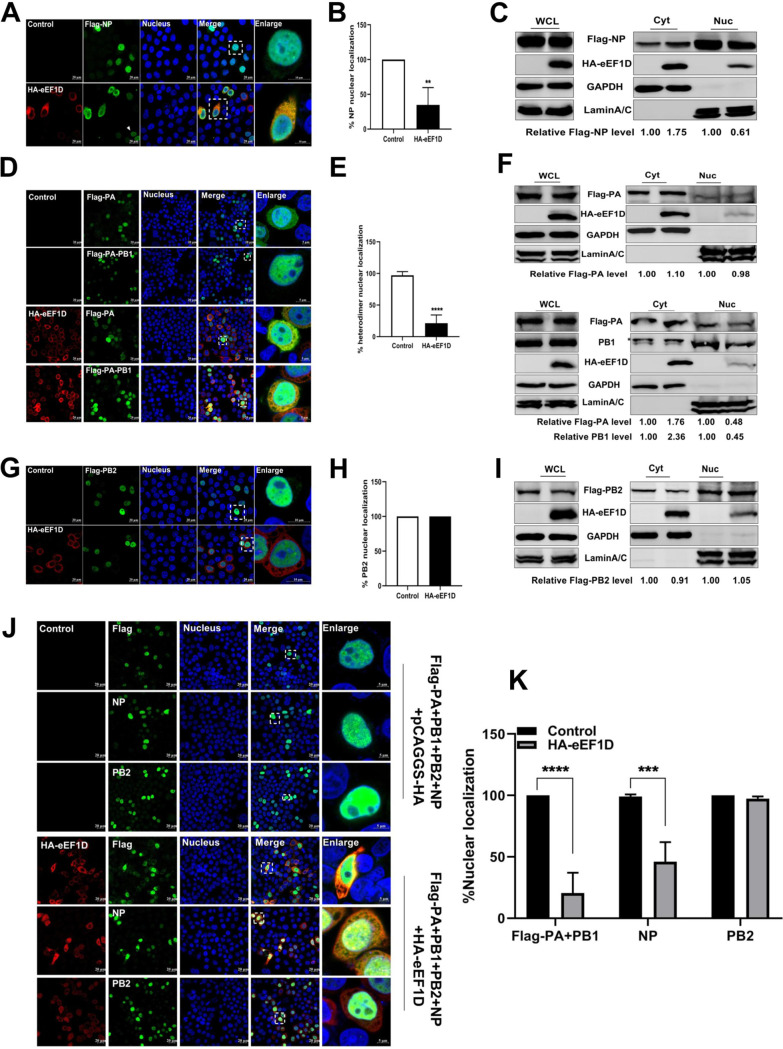

We further examined the effect of eEF1D on nuclear import of RNP subunits using confocal microscopy to detect the distribution of RNP subunits when coexpressed with eEF1D. Results showed that Flag-NP was mainly distributed in the nucleus without eEF1D overexpression (Fig. 5A), which was consistent with previous reports (51, 52), while it was largely retained in the cytoplasm when eEF1D was overexpressed (Fig. 5A). We also noted that when the expression of eEF1D was low, Flag-NP could be transported into the nucleus as shown in Fig. 5A (white arrow). In contrast to the control cells, the percentage of nuclear localization of Flag-NP in eEF1D-overexpressed cells was nearly decreased to 35% (Fig. 5B). The results of nuclear and cytoplasmic fractionation showed that overexpressed eEF1D impeded the nuclear import of Flag-NP; the relative Flag-NP gray intensity is shown (Fig. 5C). To find out whether eEF1D also regulates other RNP subunits, we further investigated the effect of eEF1D on the nuclear import of viral PA-PB1 heterodimer and PB2. IFA results showed that Flag-PA was localized in the cytoplasm and nucleus, while PA-PB1 heterodimers were transported into the nucleus effectively without overexpression of eEF1D (Fig. 5D and F). However, PA-PB1 heterodimers were retained in the cytoplasm, while Flag-PA was not when eEF1D was overexpressed (Fig. 5D and F). In addition, the percentage of nuclear localization of the viral PA-PB1 heterodimer in eEF1D-overexpressed cells was almost decreased by 80% in contrast to control cells (Fig. 5E). However, we found that eEF1D did not influence the nuclear import of PB2 (Fig. 5G, H, and I). We further determined the effect of eEF1D on the localization of each subunit of vRNP when cotransfected with Flag-PA, PB1, PB2, and NP. Results exhibited that eEF1D could block the nuclear import of Flag-PA-PB1 heterodimer (Flag antibody indication) and NP (NP antibody indication), but it could not block the nuclear import of PB2 (PB2 antibody indication) (Fig. 5J). Then, we counted the cells that were cotransfected with Flag-PA, PB1, PB2, and NP successfully in four randomly selected fields. The percentages of Flag-PA-PB1 heterodimer, NP, and PB2 nuclear localization in the whole counted cells are shown in Fig. 5K; results further demonstrated that eEF1D interfered with the nuclear import of viral NP and the PA-PB1 heterodimer, but not PB2.

FIG 5.

eEF1D affects the nucleocytoplasmic distribution of viral NP and PA-PB1 heterodimer. (A) Confocal analysis confirmed the inhibition of nuclearimport of Flag-NP (green) in eEF1D- (red) overexpressed cells. HeLa cells were treated as described in Fig. 3B. The squared marked region was enlarged and is shown on the right. (B) Percentage of stained cells with mainly nuclear localized NP among total cells was calculated in randomly selected four fields of view (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; unpaired two-tailed Student's t test). (C) Western blot analysis of the nucleocytoplasmic distribution of Flag-NP in HeLa cells cotransfected with HA-eEF1D or vector. (D) HeLa cells were grown on coverslips and cotransfected with Flag-PA, nontagged-PB1 (green), and HA-eEF1D (red) or vector (pCAGGS-HA), or HeLa cells were cotransfected with Flag-PA alone (green) and HA-eEF1D (red) used as a control. The squared marked region was enlarged and is shown on the right. (E) Percentage of stained cells with mainly nuclear localized PA-PB1 heterodimer among total cells was calculated in four random fields of view (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; unpaired two-tailed Student's t test). (F) Western blot analysis of the nucleocytoplasmic distribution of Flag-PA and PA-PB1 heterodimer in HeLa cells cotransfected with HA-eEF1D or vector. (G) Coverslips coated with HeLa cells were cotransfected with a plasmid expressing PR8-Flag-PB2 (green) and an empty vector (pCAGGS-HA) or HA-eEF1D (red). The squared marked region was enlarged and is shown on the right. (H) Percentage of stained cells with mainly nuclear localized PB2 among total cells was calculated in four random fields of view (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; unpaired two-tailed Student's t test). (I) Western blot analysis of the nucleocytoplasmic distribution of Flag-PB2 in HeLa cells cotransfected with HA-eEF1D or vector. (J) Confocal analysis of the nucleocytoplasmic distribution of Flag-PA-PB1 heterodimer, NP, and PB2 when HeLa cells were cotransfected with Flag-PA, PB1, PB2, and NP (green), HA-eEF1D (red), or vector. (K) Percentage of stained cells with mainly nuclear localized Flag-PA-PB1 heterodimer, NP, and PB2 among total cells was calculated in randomly selected four fields of view (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; unpaired two-tailed Student's t test). For indirect immunofluorescence experiments, samples were examined with a confocal microscope (LSM 880; Zeiss). Images are representative of three independent experiments. Scale bar, 20 μM. Western densitometry analysis was performed using software ImageJ. Lamin A/C and GAPDH were used as loading controls for nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions, respectively. The relative viral protein levels (viral protein/GAPDH or lamin A/C) are shown at the bottom of panels C, F, and I.

eEF1D weakens the binding of NP to importin α5 and the binding of the PA-PB1 dimer to RanBP5.

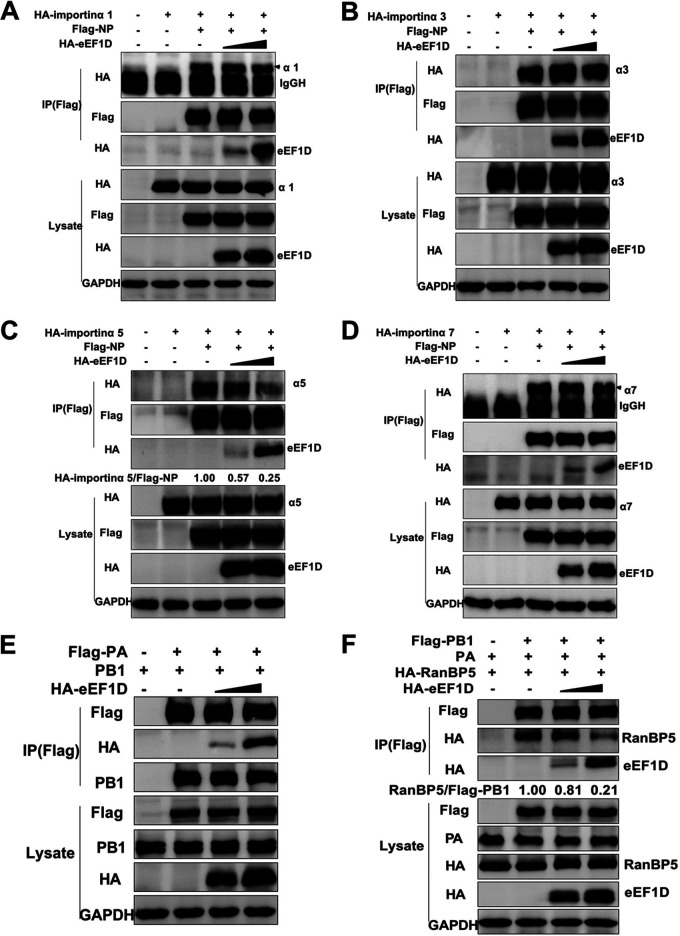

Previous studies have already reported that importin α1, α3, α5, and α7 associated with NP to mediate its nuclear import (3, 53–55). Based on our observations, we hypothesized that eEF1D might disrupt the interaction between NP and importin α, resulting in the retention of NP in the cytoplasm. To this end, HEK293T cells were cotransfected with Flag-NP and HA-importin α together with increasing amounts of HA-eEF1D. The results of coimmunoprecipitation showed that NP bound to all four isoforms of importin α (Fig. 6A to D), and the amounts of importin α5 coimmunoprecipitated with NP were significantly reduced by eEF1D (Fig. 6C), but eEF1D did not affect the interactions of other three members of importin α family with NP (Fig. 6A, B, and D), indicating that eEF1D only interfered with the interaction between NP and importin α5. These results suggest that eEF1D inhibits the nuclear import of NP by impairing the interaction of NP with importin α5.

FIG 6.

Overexpression of eEF1D blocks IAV NP-importin α5 and PB1-RanBP5 interactions. (A to D) Interaction of NP with importin α family members, importin α1 (A), importin α3 (B), importin α5 (C), and importin α7 (D) in the presence or absence of gradually increasing amounts (0 to 0.3 μg) of HA-eEF1D. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with a mouse anti-Flag antibody, and the bound proteins were detected by Western blotting with a mouse anti-HA antibody or a mouse anti-Flag antibody to detect importin α family members, eEF1D, NP, and GAPDH, respectively. (E) Effect of eEF1D on the interaction between PA and PB1. HEK293T cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids for 24 h. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag antibody for the co-IP assay. Flag-PA and PB1 levels were checked via immunoprecipitation by Western blotting. (F) Effect of eEF1D on the interaction between RanBP5 in PB1 upon the PA, PB1, and RanBP5 complex. HEK293T cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids for 24 h. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag antibody for co-IP assay. RanBP5 and Flag-PB1 levels were detected via immunoprecipitation by Western blotting.

As described above that eEF1D associated with PA and PB1, it was important to ascertain whether eEF1D would affect the interaction between PA and PB1. Results of cotransfection with eEF1D, PA, and PB1, as depicted in Fig. 6E, show that no reduction in the amount of PB1 immunoprecipitated with Flag-PA was observed with an increasing amount of HA-eEF1D. Next, we further explored the mechanism of how eEF1D affected the entry of the viral PA-PB1 heterodimer into the nucleus. Viral PA-PB1 heterodimers entered the nucleus via a nonclassical transport pathway mediated by RanBP5. As RanBP5 interacts with PB1 alone or PA-PB1 complex but not with PA alone (56), Flag-PB1, HA-RanBP5, and PA were cotransfected together with increasing amounts of HA-eEF1D in HEK293T cells. The results of coimmunoprecipitation showed that PB1 bound to RanBP5 as reported previously, but the amount of PB1 binding to RanBP5 was significantly decreased when eEF1D was overexpressed (Fig. 6F). Additionally, we did not observe the interaction between RanBP5 and eEF1D (Fig. S5C). Therefore, we conclude that eEF1D impairs the interaction between viral PA-PB1 heterodimer and RanBP5.

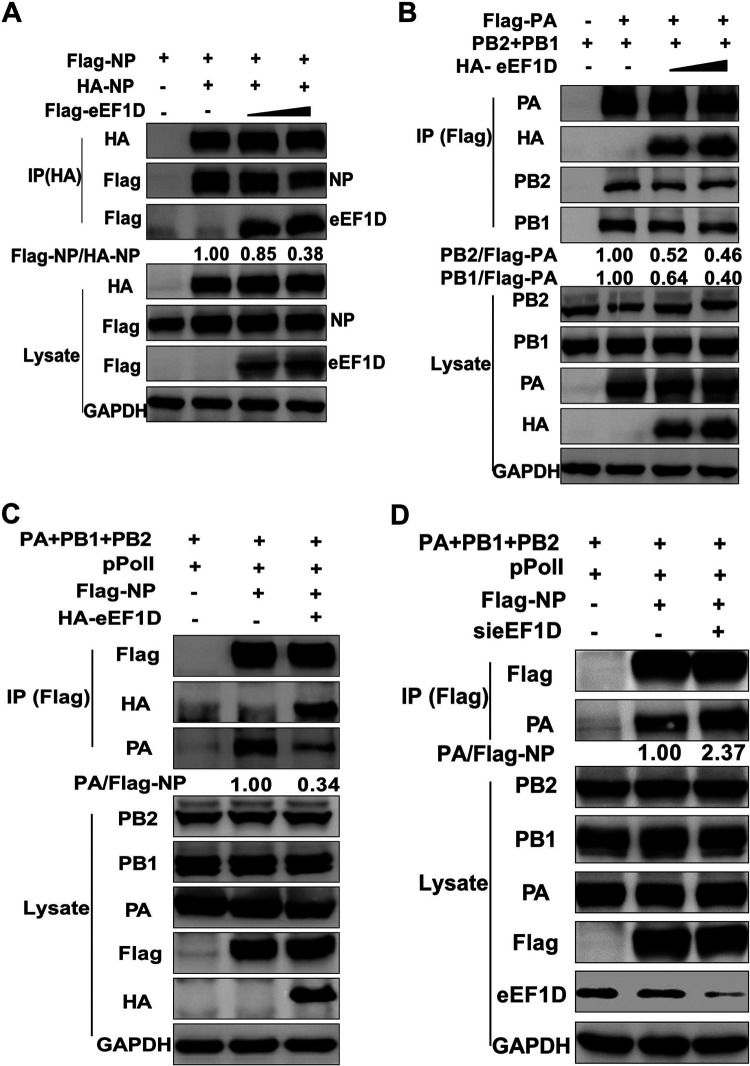

eEF1D impairs viral RNP assembly.

We further determined the effect of eEF1D on NP oligomerization. NP homo-oligomerization was apparently responsible for the higher-order structure of RNPs by direct interaction with NP monomers (57, 58). HEK293T cells were cotransfected with the plasmids expressing HA-NP and Flag-NP together with increasing the amount of HA-eEF1D. Results showed that the levels of Flag-NP associated with HA-NP were obviously decreased with eEF1D overexpression (Fig. 7A). As eEF1D interacted with PA and PB1 and inhibited the nuclear import of PA-PB1 heterodimers, we investigated the impact of eEF1D on the formation of the polymerase (PA, PB1, and PB2) complex of IAV. The results of coimmunoprecipitation of cotransfected PA, PB1, and PB2 showed that the levels of PB1 and PB2 immunoprecipitated by PA were decreased in a dose-dependent manner with overexpression of eEF1D (Fig. 7B), suggesting that eEF1D did exert its effect on the polymerase complex assembly. Then, we investigated whether the eEF1D could affect viral RNP assembly, a process that occurred in the nucleus. Results showed that immunoprecipitated PA was remarkably reduced in the reconstituted minigenome system by using Flag-NP as bait in the eEF1D-overexpressed cells (Fig. 7C). Conversely, Flag-NP immunoprecipitated more PA in the reconstituted minigenome system in the eEF1D-knockdown cells than in the control cells (Fig. 7D). We therefore conclude that eEF1D disrupts the NP self-association and RNA polymerase complexes formation, thereby inhibiting viral RNP assembly.

FIG 7.

eEF1D impairs viral RNP complex formation. (A) eEF1D inhibited NP oligomerization. HEK293T cells were transfected with Flag-NP, HA-NP, and HA-eEF1D (0, 0.25, and 0.5 μg) or vector. Cells were harvested at 24 h posttransfection for a co-IP assay and Western blot assay. Densitometry analysis was done using ImageJ, and relative precipitated Flag-NP/HA-NP ratios are shown at the bottom. (B) eEF1D reduced 3P complex association. HEK293T cells were transfected with Flag-PA, PB1, and PB2 plasmids along with increasing amounts of HA-eEF1D plasmids. Cells were then lysed for the co-IP assay using anti-Flag antibody. The immune complexes were analyzed by performing a Western blot assay using antibodies against PA, PB1, PB2, and HA, respectively. The band intensities were quantified, and relative precipitated PB1/Flag-PA and PB2/Flag-PA ratios are shown at the bottom. (C) eEF1D decreased influenza virus RNP assembly. HEK293T cells were transfected with plasmids containing PA, PB1, PB2, Flag-NP, and pPolI along with HA-eEF1D or vector. Cells were lysed at 24 h posttransfection, and co-IP was performed by using anti-Flag antibody followed by Western blotting. The band intensities were quantified, and relative precipitated PA/Flag-NP ratios are shown at the bottom. (D) Knockdown of eEF1D stimulated RNP assembly. HEK293T cells transfected with the plasmids containing PA, PB1, PB2, Flag-NP, and pPolI along with si-eEF1D or si-NC. The remaining procedures are also the same as in panel C.

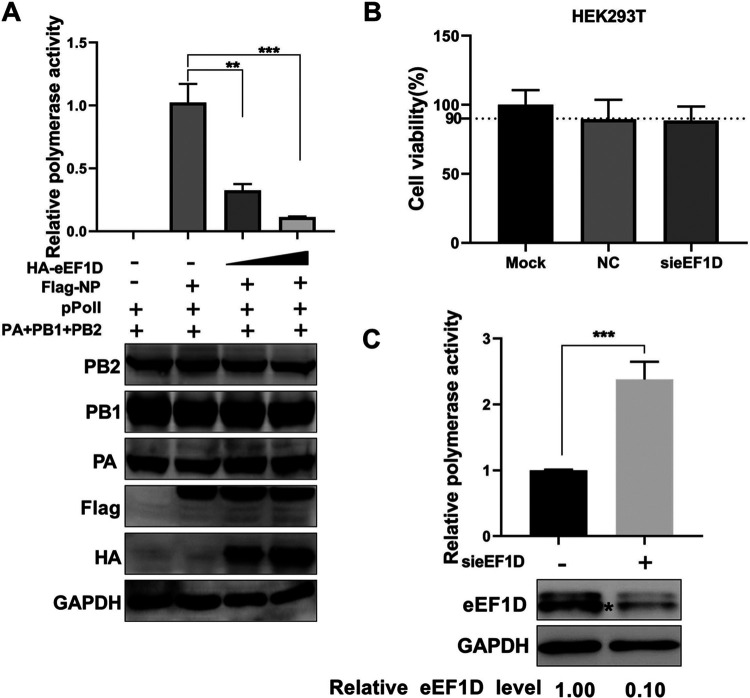

eEF1D decreases polymerase activity.

Given that vRNP assembly was required for the polymerase activity of IAV, we attempted to explore the impact of eEF1D on the polymerase activity. HEK293T cells were cotransfected with the RNP reconstitution plasmids (pcDNA-PB1, pcDNA-PB2, pcDNA-PA, pcDNA-NP, and polI-firefly) and RL-TK, together with increasing amounts of HA-eEF1D or small interfering RNA (siRNA)-targeted eEF1D. The relative polymerase activity was reduced by eEF1D in a dose-dependent manner, as shown in Fig. 8A. Meanwhile, we found that eEF1D overexpression did not affect the expression levels of PA, PB1, PB2, and NP (Fig. 8A), indicating that eEF1D inhibited polymerase activity without affecting the expression levels of RNP components. In contrast, eEF1D silencing was performed and showed no cytotoxic effect on HEK293T cells (Fig. 8B) in which the polymerase activity was significantly promoted (Fig. 8C). These data indicate that eEF1D decreases viral polymerase activity.

FIG 8.

eEF1D reduces the polymerase activity of IAV. (A) Effect of eEF1D on the expression of RNP components in HEK293T cells. HEK293T cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids as described above (Fig. 7C). Protein expression of individual RNP components and eEF1D were detected by Western blotting. GAPDH was used as loading control. For all experiments above, the data are presented as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; two-tailed Student's t test). (B) Cell viability upon si-eEF1D transfection. HEK293T cells were treated with siRNA against eEF1D and control nontarget siRNA. The cell viability was measured by CCK-8 assay at the indicated time points posttransfection (mean ± SD of three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; two-tailed Student's t test). (C) Cells were cotransfected with plasmids containing PA, PB1, PB2, Flag-NP, and pPolI along si-eEF1D or si-NC. The silencing efficiency of si-eEF1D was measured by Western blotting. GAPDH served as loading control. Band intensities were quantified with ImageJ, and the relative eEF1D levels are shown at the bottom (mean ± SD of three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; two-tailed Student's t test).

eEF1D reduces viral RNA synthesis.

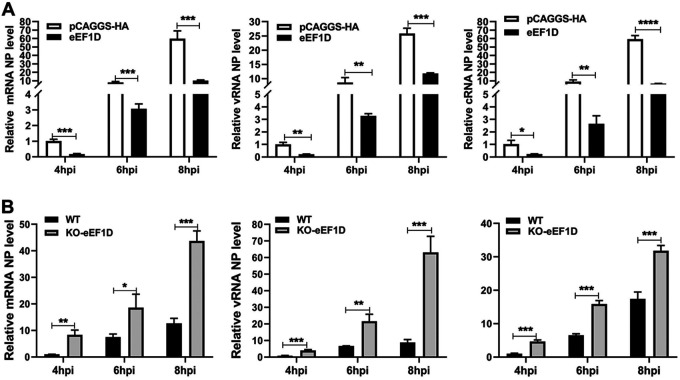

To determine whether eEF1D affected viral genome replication, A549 cells were transfected with eEF1D expression plasmid, followed by infection of PR8 H1N1 virus at 24 h posttransfection, and the viral RNAs were detected at 4 h, 6 h, and 8 hpi. The levels of three viral RNAs (vRNA, cRNA, and mRNA) were obviously lower in the eEF1D-overexpressed cells than those in control cells (Fig. 9A). To validate the reduction in viral RNA synthesis caused by eEF1D, the wild-type and KO-eEF1D A549 cells were infected PR8 H1N1 virus in parallel. As expected, the levels of all three viral RNAs showed a significant increase in eEF1D knockout cells infected with the PR8 H1N1 virus (Fig. 9B). These findings demonstrate that eEF1D inhibits viral RNA synthesis.

FIG 9.

eEF1D restricts RNA synthesis during IAV infection. (A) A549 cells were transfected with eEF1D or vector for 24 h and were infected with PR8 H1N1 virus at an MOI of 1.0. Samples were collected at 4 hpi, 6 hpi, and 8 hpi. The vRNA, cRNA, and mRNA levels of NP were detected by qRT-PCR. The viral RNA levels were normalized to the 18S rRNA level (mean ± SD of three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001; two-tailed Student’s t test). (B) WT-A549 cells and KO-eEF1D A549 cells were seeded in 12-well plates and then infected with the PR8 H1N1 virus at an MOI of 1.0. Other procedures were the same as described in panel A (mean ± SD of three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001; two-tailed Student’s t test).

DISCUSSION

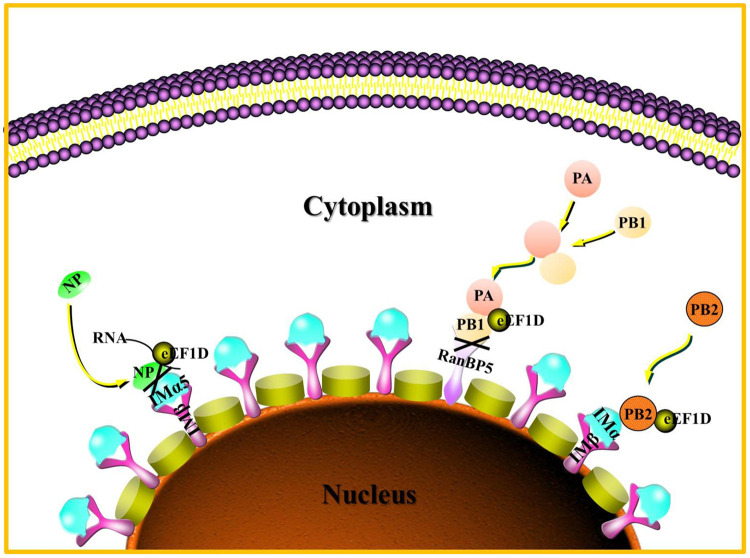

The influenza viral life cycle begins with virus entry into the cell via endocytosis. Then, the vRNPs are released into the cytoplasm and then transported into the nucleus for the primary transcription (7). After completion of the primary transcription, the mRNA transcripts are exported into the cytoplasm for translation in ribosomes. The newly formed viral proteins, such as PB2, NP monomers, and PA-PB1 heterodimers, traffic back into the nucleus for transcription and replication (28, 59). The transcription and replication of IAV are performed by the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (60). Next, the mature vRNPs are exported into the cytoplasm via the CRM1 pathway mediated by nuclear export protein (NEP) and M1 (61, 62). Following the nuclear export, mature vRNPs are transported into the cell membrane for the progeny virions assembly and budding (63). Finally, the released progeny virions infect adjacent cells for a new life cycle. Our study demonstrated that eEF1D interacted with all the components of RNPs in both transfected and virus-infected cells. Interestingly, the interaction between eEF1D and NP was mediated by RNAs, while the interactions with PA, PB1, and PB2 were not. The partial viral NP and PA-PB1 heterodimer were hijacked by eEF1D in the cytoplasm, and eEF1D weakened the interactions of NP with importin α5 as well as of PB1 with RanBP5. Therefore, eEF1D suppressed viral RNP assembly virus genome transcription and replication and negatively regulated the propagation of IAV as proposed in a model depicted in Fig. 10.

FIG 10.

Proposed model for eEF1D-mediated inhibition of the nuclear import of NP and PA-PB1 heterodimer. In the cytoplasm, eEF1D inhibits the binding of newly synthesized NP to importin α5 and reduces the affinity of PB1 with RanBP5 in the PA-PB1 heterodimer, thereby suppressing the nuclear import of vRNPs.

During the nuclear import of vRNP, importin α mainly recognizes the NLSs of NP for its transportation through the nuclear pore. The nuclear import of the newly synthesized NP also relies on the classical cellular IMPα-IMPβ pathway (21, 22, 32). The nuclear import of vRNPs or RNP subunits is an active process that needs host factors and energy (3). eEF1D, which is a nonribosomal protein known as elongation factor, has two functional domains, including leucine-zipper motif for proteins interactions (64) and guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) domain for catalyzing the exchange of GDP for GTP (65, 66). Therefore, eEF1D may affect the exchange of GDP for GTP in the process of the nuclear import of vRNPs or RNP subunits. To date, several host proteins have been reported to affect the nuclear import process. On one hand, some host proteins can inhibit the nuclear import of vRNP subunits of IAV. For example, PLSCR1 has been shown to impede the NP nuclear import by disrupting the interaction between importin α1 and importin β (31); MOV10 inhibits the NP nuclear import by impairing the interaction between NP and importin α (32). Interestingly, MOV10 binds to NP in an RNA-dependent manner, while the interaction between PLSCR1 and NP is not mediated by RNAs. On the other hand, there is also the host factor that can promote the nuclear import process, such as Hsp40/DnaJB1. Hsp40/DnaJB1 promotes the nuclear import of vRNP by binding to the N-terminal domain of NP (34) and assists NP to interact with importin α. Our study revealed that eEF1D only impaired the association of NP and importin α5 by interacting with NP in an RNA-dependent manner. In contrast to PLSCR1, MOV10, and Hsp40/DnaJB1, eEF1D could bind to all the RNP subunits, while PLSCR1, MOV10, and Hsp40/DnaJB1 only interacted with NP. Therefore, eEF1D is a novel host factor that can affect the NP nuclear entry. Intriguingly, importin α isoforms did not interact with eEF1D, as shown in Fig. S5A in the supplemental material. It was also unexpected that eEF1D did not affect the interactions between importin α1, importin α3, or importin α7 and NP. Importin α recognizes the simian virus 40 (SV40) NLS with similar affinity but show different preferences to other NLS sequence (67–69). The SV40 NLS is PKKKRKV, while an unconventional nuclear localization signal of NP is S/TxGTKRSYxxM (22, 70), which plays a crucial role in the nuclear import of NP and vRNP (24). Different importin α isoforms can bind to the same substrate, but the import efficiencies of the substrate are different. Importin α5 shows the strongest effect on nuclear import of nucleoplasmin, while the import efficiency of importin α1 is mildly weaker (68, 71). NP can bind to importin α1, importin α3, importin α5, and importin α7 at the same time; the importin α proteins may be different in NP import efficiencies. In addition, NP of PR8 H1N1 virus showed strikingly different affinities in the interactions with importin α1, α3, α5, and α7 (Fig. S5B). Importin α1 and importin α5 belong to different subfamilies, while importin α5 belongs to the clade α1, and importin α1 belongs to the clade α2 (72). Importin α3 and importin α7 both bind to PB2 and NP and are closely related to host adaption and cell tropism. Avian influenza viruses depend on importin α3, whereas mammalian influenza viruses depend on importin α7 (73). Our results also show that eEF1D cannot affect the interactions between importin α3 or importin α7 and NP. The previous studies and our results suggest that the subunits of importin α isoforms that play dominant roles in regulating the different types of IAV are different, although these subunits have a high homology. In this study, eEF1D suppresses IAV via interfering with the interaction between NP and importin α5. Why it is importin α5 may be due to that the sequence of NP binding to eEF1D can overlap the sequence of NP recognized by importin α5, thereby blocking the interaction between NP and importin α5.

When the newly synthesized NP enters the nucleus, PA and PB1 also are transported into the nucleus in the form of heterodimers with the assistance of RanBP5. RanBP5, also named importin β3, belongs to the importin superfamily, just like importin α1, α3, α5, and α7 (72). It has been reported that some host proteins can participate in the nuclear import of the polymerase subunits. For instance, HAX1 can impede nuclear transport of PA by interacting with the nuclear localization signal domain of PA, and the inhibition of HAX1 is alleviated by PB1 (33). HSP90 is a molecular chaperone for the nuclear import of PB2 (74); DnaJA1 is a PA-PB1 dimers chaperone which enhances the RNA polymerase activity of IAV. Although DnaJA1 interacts with all the RNP subunits, it cannot affect viral RNP assembly (75). However, it is barely reported that the host proteins can disrupt the associations of the polymerase subunits and transport factors known such as importins. Our studies showed that eEF1D bound to PA and PB1 and impeded the nuclear import of the viral PA-PB1 heterodimer by impairing the bindings of PB1 and RanBP5. Different from HAX1, eEF1D did not affect the subcellular localization of PA and had no effect on the formation of PA and PB1 heterodimers. Additionally, eEF1D could not interact with RanBP5, as shown in Fig. S5C. The domain of eEF1D binds to PB1 and may overlay the domain of RanBP5 that interacts with PB1, leading to disrupt the binding of PB1 and RanBP5. The underlying mechanisms need to be further investigated. These results demonstrate that eEF1D impairs the interactions between the importins and IAV RNP subunits, thus affecting the nuclear import of IAV. Our studies reveal the important roles of eEF1D in a negative manner to regulate replication of IAVs. Moreover, a previous study has shown that eEF1A1, eEF1D, and eEF1G bound to RNA-dependent RNA polymerase L of the vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) for supporting its activity (76). Our results further demonstrate that eEF1D promotes the replication of VSV. Different from IAVs, the transcription and replication of VSV occurs in the cytoplasm rather than in the nucleus. This may be one of the reasons why opposite impacts of eEF1D on both viruses were observed. Whether the eEF1D has the same impacts on other RNA viruses that replicate in the cytoplasm and the same mechanisms used need to be investigated in future studies. The eEF1 complex plays a role in HIV-1 early replication by supporting efficient reverse transcription (77). However, the role of how the eEF1 complex regulates the life cycle of IAV remains unclear. As components of the eEF1 complex, the roles of eEF1A1 and eEF1B2 in IAV propagation remain unknown. Although eEF1G and eEF1D both can interact with PA, PB1, PB2, and NP, their impacts on the proliferation of IAV are very different. eEF1G promotes IAV replication in a strain-specific manner (46), while eEF1D inhibits the replication of IAV without species specificity. Therefore, further studies focused on the differences of regulating IAV among eEF1B2, eEF1A1, eEF1G, and eEF1D are required and would help us to figure out the mechanism of the eEF1 complex in IAV replication.

In summary, our data show that eEF1D is a novel vRNP-binding protein that is pivotal for IAV replication. eEF1D impedes the nuclear import of viral NP and PA-PB1 heterodimers, thus retarding the virus life cycle of IAV. Importantly, we uncover the underlying mechanisms of how eEF1D impairs the formation of a complex of viral NP and importin α5 and of a complex of viral PA-PB1 heterodimer and RanBP5. These will advance our understanding that host proteins regulate the vRNP nuclear import of IAV.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) and human embryonic kidney 293T cells (HEK293T) were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA) and were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (HyClone, Beijing, China). The human lung epithelial cells (A549) and the human cervix epithelial cells (HeLa) were purchased from ATCC and maintained in Ham’s F-12 medium and RPMI 1640 medium (HyClone, Beijing, China), respectively. All media were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (PNA-Biotech, Germany), and all cells were cultured at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere.

IAVs used in experiments were A/swine/Hubei/221/2016 (HB H1N1), A/duck/Hubei/Hangmei01/2006 (HM H5N1), and A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 (PR8 H1N1). All viruses were amplified in 10-day-old specific-pathogen-free (SPF) embryonic chicken eggs (Sparfas, Jinan, China) and then titrated via TCID50 assay on MDCK cells. All experiments with the H5N1 virus were performed in a biosafety level 3 laboratory (BSL3). This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of BSL3 laboratory at Huazhong Agricultural University (HZAU). All procedures were approved by the Intuitional Biosafety Committee of HZAU. The recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus expressing green fluorescent protein (VSV-GFP) was a gift from Harbin Veterinary Research Institute (Harbin, China).

Antibodies and reagents.

The antibodies used were anti-eEF1D mouse monoclonal antibody (catalog no. 60085-2-Ig and 60085-1-Ig,; Proteintech, USA); anti-Flag mouse monoclonal antibody (catalog no. F1804; Sigma, USA); anti-HA, anti-GFP, and anti-GAPDH mouse monoclonal antibodies (catalog no. PMK013C, PKM009S, and PMK043F, respectively; PMK Bio, China); anti-GST mouse monoclonal antibody (catalog no. AE001; Abclonal, China); anti-lamin A/C rabbit polyclonal antibody (catalog no. 10298-1-AP; Proteintech, USA); anti-IAV PA, PB1, PB2, NP, and M1 rabbit polyclonal antibodies (catalog no. GTX118991, GTX125923, GTX125926, GTX125989, and GTX125928, respectively; GeneTex, USA); and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated AffiniPure goat anti-mouse (catalog no. GM200G-02C; Sungene Biotech) and Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated AffiniPure goat rabbit (catalog no. GR200G-43C; Sungene Biotech) secondary antibodies. The small-molecule compounds used in this study were: DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; 1:1,000) (catalog no. C1002; Beyotime, China) and CHX (cycloheximide; 100 μg/ml) (catalog no. 66819; Sigma, USA).

Plasmids and small interfering RNAs.

The eEF1D gene was cloned into eukaryotic expression vector pCAGGS-HA at ClaI and XhoI sites and into the vector p3×FLAG-CMV-14 at EcoRI and XbaI sites, respectively. eEF1D cDNA was also cloned into prokaryotic expression vector pGEX-KG with GST at the N terminus through EcoRI and XhoI sites. The Flag-tagged and nontagged plasmids encoding PA (GenBank accession no. CY147539), PB1 (GenBank accession no. CY147540), PB2 (GenBank accession no. CY147541), and NP (GenBank accession no. CY147537) of the PR8 H1N1 virus and Flag-LYAR (GenBank accession no. NM_017816.3) were constructed previously in our laboratory. The RanBP5 (importin 5) gene was cloned into eukaryotic expression vector pCAGGS-HA at KpnI and XhoI sites, and the full-length open reading frames (ORFs) of human importin α1 (GenBank accession no. BC005978.1), importin α3 (AK291041), importin α5 (CR456743.1), and importin α7 (AF060543 ) were constructed by our laboratory. The PCR primers were designed by Primer 5, and the sequences are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. All plasmid constructs were confirmed by sequencing. eEF1D small interfering RNA (si-eEF1D) and a validated negative control (NC) were purchased from GenePharma (Shanghai, China). The knockdown efficiency was examined by Western blotting.

Generation of the KO-eEF1D A549 cells.

KO-eEF1D A549 cells were generated by using the CRISPR/Cas9 system as described previously (78, 79). The single guide RNA (sgRNA) sequence targeting the human eEF1D gene (5′-CACCGTCCGGACGACGAGCTCACCG-3′) was cloned into lentiCRISPR v2 vector and used to produce the recombined lentivirus. After 24 h postinfection of the eEF1D lentiCRISPR v2 lentivirus or the empty-vector lentiCRISPR v2 lentivirus (negative control), the puromycin (2.5 μg/ml) was added to select the positive clones. The selected monoclonal cells obtained by the serially diluted method were then grown. At last, the knockout of eEF1D was confirmed by sequencing at the genome level and Western blotting at the protein level.

Transfection and virus titration.

Plasmids and siRNAs transfections were done using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) in all cells maintained in Opti-MEM. The culture medium was replaced with fresh medium supplemented with 10% FBS after 6 h posttransfection. For virus titration of IAV, A549 cells in 12-well plates were infected with IAV as indicated at an MOI of 0.01 or 0.1. After virus adsorption for 1 h, cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then incubated in Ham’s F-12 medium with or without 0.25 μg/ml tosylsulfonyl phenylalanyl chloromethyl ketone-treated trypsin (TPCK) (Sigma) at 37°C. Viral supernatants were harvested at the indicated time points postinfection and diluted serially in DMEM and adsorbed onto MDCK cell monolayers seeded in 96-well plates. After 1 h of adsorption, the inoculum was removed, and cells were washed with PBS and overlaid with DMEM containing trypsin-TPCK (Sigma) or not. The plates were incubated for 72 h at 37°C. Virus titers were determined by calculating log10 TCID50/milliliter on MDCK cells using the Spearman-Karber method (80). WT- and KO-eEF1D A549 cells were infected with VSV-GFP at an MOI of 0.1 in the serum-free medium for 2 h for virus entry. Then, the infection medium was removed by washing twice by PBS. Cells were maintained within the fresh medium with 1% FBS. Infected cells were analyzed by fluorescence microscopy, reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR), and Western blotting using a GFP antibody.

Quantitative RT-PCR assay.

Total cellular RNAs were extracted from cells using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNAs were treated with DNase before generating cDNA using reverse transcriptase (AMV XL; TaKaRa, Tokyo, Japan). The acquired cDNA was then used as the template in an SYBR green-based RT-PCR with the ABI ViiA 7 PCR system (Applied Biosystems). The levels of IAV NP vRNA, cRNA, and mRNA were determined by using a strand-specific real-time RT-PCR as described previously (81, 82). The relative mRNA, vRNA, and cRNA levels of IAV were normalized to 18S rRNA and analyzed by the threshold cycle calculation method (2−△△CT). The relative N mRNA level of VSV-GFP was normalized to GAPDH mRNA. All qRT-PCR primers are listed in Table S2.

Minigenome assay.

HEK293T cells were cotransfected with pcDNA3.1-PB1, pcDNA3.1-PB2, pcDNA3.1-PA, pcDNA3.1-NP, and pPolI-luc that contains the firefly luciferase gene flanked by the noncoding regions of the influenza nonstructural (NS) gene segment (83) and a Renilla expression control. At 24 h posttransfection, the relative polymerase activity (firefly normalized to Renilla) was measured using the dual-luciferase assay kit (Promega, USA). The Renilla luciferase activity was used as an internal control and to normalize transfection efficiency.

Indirect immunofluorescence assay.

A549 or HeLa cells were grown on coverslips and transfected with indicated plasmids or infected with an indicated influenza A virus. Then, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 15 min, permeabilized using 0.2% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 for 15 min, and blocked with 1% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 30 min. Coverslips were incubated with primary antibodies for 2 h and then the appropriate Alexa Fluor conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h, and nuclei were stained with DAPI for 15 min at room temperature. These samples were observed by using a confocal microscope (LSM 880; Zeiss, Germany).

Immunoprecipitation assay.

HEK293T cells were transfected with the abovementioned plasmids using Lipofectamine 2000 according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After 24 h or 36 h transfection, the cells were lysed in immunoprecipitation (IP) lysis buffer (Beyotime, China) plus protease inhibitor cocktail (BioTool, USA) on ice for Western blotting and IP. Subsequently, the partially cleared cell lysates were used to set up an immunoprecipitation assay using anti-HA, anti-Flag, or anti-eEF1D antibodies or mouse IgG, respectively. The reaction mix was incubated at 4°C overnight. The next day, pretreated protein A/G agarose (Santa Cruz, USA) was added to the mixtures and incubated at 4°C for another 2 h with rotation. The immunoprecipitated proteins and remaining cell lysates were separated on SDS-PAGE followed by transferring to nitrocellulose for Western blotting. Images were obtained using an ECL detection system (Amersham Biosciences, USA).

GST pulldown.

Glutathione S-transferase (GST)-fused eEF1D or GST proteins were expressed from Escherichia coli and were purified by glutathione-Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare). Purified GST and GST-eEF1D proteins were detected by using Coomassie blue (CB) staining. HEK293T cells grown in 10-cm dishes were transfected with 10 μg of each plasmid (Flag-PA, Flag-PB1, Flag-PB2, or Flag-NP). At 36 h posttransfection, cells were lysed with 500 μl of IP lysis buffer. The purified GST-eEF1D was mixed with 40 μl of glutathione-Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare) and rocked for 3 h at 4°C. After five washes with buffer, the lysates of HEK293T cells were added and incubated for 2 h at 4°C. After five more washes, the bound proteins were analyzed by performing a Western blot assay.

Nuclear and cytoplasmic fractionation.

Subcellular fractions were extracted as described previously (84). In brief, cells were harvested in ice-cold PBS and collected by centrifugation at 1,000 rpm for 5 min. Cell pellets were resuspended in hypotonic lysis buffer (10 mM HEPES-NaOH [pH 7.9], 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, and 0.5 mM beta-mercaptoethanol) supplemented with protease inhibitors and phosphatase inhibitors, vortexed, and then incubated on ice for 15 min followed by the addition of 3 μl 10% NP-40 for another 5 min. Samples were centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 10 min, the supernatants were cytoplasmic proteins, and the pellets were for nuclear protein extraction. Pellets were washed with cold PBS twice with radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer added (catalog no. V900854; Sigma, USA) as nuclear lysis buffer, and they were then dispersed and incubated on ice for 20 min. The extractions were centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 10 min for nuclear proteins. The proteins were collected and stored at −80°C.

IAV internalization assay.

Wild-type or eEF1D knockout A549 cells were infected with the PR8 H1N1 virus at an MOI of 10 at 37°C for 0, 30, and 45 min and then washed with PBS (pH 1.3 at 4°C) to remove the attached but not-yet-internalized virions. Next, the cells were collected and lysed by M-PER (mammalian protein extraction reagent) (Thermo Scientific, USA). The extracted proteins were quantified by a Bradford assay and subjected to Western blotting.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization.

FISH probes in our study were produced using the PR8 H1N1 virus M-segment to detect vRNA as previously described (82) and resuspended in TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0). For FISH analysis, A549 cells in a 24-well plate were infected with PR8 H1N1 virus at an MOI of 2 at 37°C. At 8 h postinfection, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.2% (vol/vol) Triton X-100. Cells were washed three times with PBS and equilibrated with buffer A (catalog no. SMF-WA1-60; Biosearch Technologies, USA) for 5 min before the FISH procedure. To detect vRNA, 2 μl labeled probes (final concentration, 125 nM) were mixed in hybridization buffer. Hybridization was carried out in humidified chambers at 37°C for 16 h. Then, the cells were washed with buffer A for 30 min at 37°C. DAPI was added to counterstain the nuclei, and cells were incubated with buffer B (Biosearch Technologies) for 5 min at room temperature. Images were acquired using a confocal microscope (LSM 880; Zeiss).

Cell viability assay.

Cell viability was assessed using a colorimetric-based cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) assay (Dojindo Molecular Technologies). Briefly, HEK293T cells in 96-well plates were transfected with si-eEF1D or si-NC, and the cell viability was measured at 24 h posttransfection. We added 10 μl of CCK-8 reagent to each well of the plates, and cells were incubated at 37°C for 4 h; the absorbance at 450 nm was measured by a microplate reader.

Statistical analysis.

Data are expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD) of three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed by determining P values using unpaired two-tailed Student's t test (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001).

Data availability.

Data for the eEF1D and RanBP5 genes were deposited in GenBank under accession no. NM_001960 and NM_002271.6, respectively.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Xiao Xiao for critically proofreading the manuscript.

This work was partially supported by funds from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31761133005 and 31772752) and the National Key Research and Development Program (2016YFD0500205).

H.Z. and Q.G. designed the study; Q.G., C.Y., C.R., S.Z., and X.G. conducted the experiments; Q.G., C.Y., M.J., H.C., W.M., and H.Z. analyzed the data; and Q.G., W.M., C.Y., and H.Z. wrote the paper. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zheng W, Tao YJ. 2013. Structure and assembly of the influenza A virus ribonucleoprotein complex. FEBS Lett 587:1206–1214. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Resa-Infante P, Jorba N, Coloma R, Ortin J. 2011. The influenza virus RNA synthesis machine: advances in its structure and function. RNA Biol 8:207–215. doi: 10.4161/rna.8.2.14513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eisfeld AJ, Neumann G, Kawaoka Y. 2015. At the centre: influenza A virus ribonucleoproteins. Nat Rev Microbiol 13:28–41. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Honda A, Ueda K, Nagata K, Ishihama A. 1988. RNA polymerase of influenza virus: role of NP in RNA chain elongation. J Biochem 104:1021–1026. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a122569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elton D, Medcalf E, Bishop K, Digard P. 1999. Oligomerization of the influenza virus nucleoprotein: identification of positive and negative sequence elements. Virology 260:190–200. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ye Q, Krug RM, Tao YJ. 2006. The mechanism by which influenza A virus nucleoprotein forms oligomers and binds RNA. Nature 444:1078–1082. doi: 10.1038/nature05379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Te Velthuis AJ, Fodor E. 2016. Influenza virus RNA polymerase: insights into the mechanisms of viral RNA synthesis. Nat Rev Microbiol 14:479–493. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valles SM, Oi DH, Becnel JJ, Wetterer JK, LaPolla JS, Firth AE. 2016. Isolation and characterization of Nylanderia fulva virus 1, a positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus infecting the tawny crazy ant, Nylanderia fulva. Virology 496:244–254. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2016.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guilligay D, Tarendeau F, Resa-Infante P, Coloma R, Crepin T, Sehr P, Lewis J, Ruigrok RW, Ortin J, Hart DJ, Cusack S. 2008. The structural basis for cap binding by influenza virus polymerase subunit PB2. Nat Struct Mol Biol 15:500–506. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blaas D, Patzelt E, Kuechler E. 1982. Identification of the cap binding protein of influenza virus. Nucleic Acids Res 10:4803–4812. doi: 10.1093/nar/10.15.4803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yuan P, Bartlam M, Lou Z, Chen S, Zhou J, He X, Lv Z, Ge R, Li X, Deng T, Fodor E, Rao Z, Liu Y. 2009. Crystal structure of an avian influenza polymerase PA(N) reveals an endonuclease active site. Nature 458:909–913. doi: 10.1038/nature07720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dias A, Bouvier D, Crepin T, McCarthy AA, Hart DJ, Baudin F, Cusack S, Ruigrok RW. 2009. The cap-snatching endonuclease of influenza virus polymerase resides in the PA subunit. Nature 458:914–918. doi: 10.1038/nature07745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Plotch SJ, Bouloy M, Ulmanen I, Krug RM. 1981. A unique cap(m7GpppXm)-dependent influenza virion endonuclease cleaves capped RNAs to generate the primers that initiate viral RNA transcription. Cell 23:847–858. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90449-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Argos P. 1988. A sequence motif in many polymerases. Nucleic Acids Res 16:9909–9916. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.21.9909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Biswas SK, Nayak DP. 1994. Mutational analysis of the conserved motifs of influenza A virus polymerase basic protein 1. J Virol 68:1819–1826. doi: 10.1128/JVI.68.3.1819-1826.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Biswas SK, Boutz PL, Nayak DP. 1998. Influenza virus nucleoprotein interacts with influenza virus polymerase proteins. J Virol 72:5493–5501. doi: 10.1128/JVI.72.7.5493-5501.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Enenkel C, Blobel G, Rexach M. 1995. Identification of a yeast karyopherin heterodimer that targets import substrate to mammalian nuclear pore complexes. J Biol Chem 270:16499–16502. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.28.16499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weis K, Mattaj IW, Lamond AI. 1995. Identification of hSRP1 alpha as a functional receptor for nuclear localization sequences. Science 268:1049–1053. doi: 10.1126/science.7754385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stewart M. 2007. Molecular mechanism of the nuclear protein import cycle. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8:195–208. doi: 10.1038/nrm2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neumann G, Castrucci MR, Kawaoka Y. 1997. Nuclear import and export of influenza virus nucleoprotein. J Virol 71:9690–9700. doi: 10.1128/JVI.71.12.9690-9700.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hutchinson EC, Fodor E. 2012. Nuclear import of the influenza A virus transcriptional machinery. Vaccine 30:7353–7358. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.04.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang P, Palese P, O'Neill RE. 1997. The NPI-1/NPI-3 (karyopherin alpha) binding site on the influenza a virus nucleoprotein NP is a nonconventional nuclear localization signal. J Virol 71:1850–1856. doi: 10.1128/JVI.71.3.1850-1856.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weber F, Kochs G, Gruber S, Haller O. 1998. A classical bipartite nuclear localization signal on Thogoto and influenza A virus nucleoproteins. Virology 250:9–18. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cros JF, Garcia-Sastre A, Palese P. 2005. An unconventional NLS is critical for the nuclear import of the influenza A virus nucleoprotein and ribonucleoprotein. Traffic 6:205–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2005.00263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakada R, Hirano H, Matsuura Y. 2015. Structure of importin-alpha bound to a non-classical nuclear localization signal of the influenza A virus nucleoprotein. Sci Rep 5:15055. doi: 10.1038/srep15055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'Neill RE, Jaskunas R, Blobel G, Palese P, Moroianu J. 1995. Nuclear import of influenza virus RNA can be mediated by viral nucleoprotein and transport factors required for protein import. J Biol Chem 270:22701–22704. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.39.22701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huet S, Avilov SV, Ferbitz L, Daigle N, Cusack S, Ellenberg J. 2010. Nuclear import and assembly of influenza A virus RNA polymerase studied in live cells by fluorescence cross-correlation spectroscopy. J Virol 84:1254–1264. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01533-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fodor E, Smith M. 2004. The PA subunit is required for efficient nuclear accumulation of the PB1 subunit of the influenza A virus RNA polymerase complex. J Virol 78:9144–9153. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.17.9144-9153.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tarendeau F, Boudet J, Guilligay D, Mas PJ, Bougault CM, Boulo S, Baudin F, Ruigrok RW, Daigle N, Ellenberg J, Cusack S, Simorre JP, Hart DJ. 2007. Structure and nuclear import function of the C-terminal domain of influenza virus polymerase PB2 subunit. Nat Struct Mol Biol 14:229–233. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mukaigawa J, Nayak DP. 1991. Two signals mediate nuclear localization of influenza virus (A/WSN/33) polymerase basic protein 2. J Virol 65:245–253. doi: 10.1128/JVI.65.1.245-253.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luo W, Zhang J, Liang L, Wang G, Li Q, Zhu P, Zhou Y, Li J, Zhao Y, Sun N, Huang S, Zhou C, Chang Y, Cui P, Chen P, Jiang Y, Deng G, Bu Z, Li C, Jiang L, Chen H. 2018. Phospholipid scramblase 1 interacts with influenza A virus NP, impairing its nuclear import and thereby suppressing virus replication. PLoS Pathog 14:e1006851. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang J, Huang F, Tan L, Bai C, Chen B, Liu J, Liang J, Liu C, Zhang S, Lu G, Chen Y, Zhang H. 2016. Host protein Moloney leukemia virus 10 (MOV10) acts as a restriction factor of influenza A virus by inhibiting the nuclear import of the viral nucleoprotein. J Virol 90:3966–3980. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03137-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hsu WB, Shih JL, Shih JR, Du JL, Teng SC, Huang LM, Wang WB. 2013. Cellular protein HAX1 interacts with the influenza A virus PA polymerase subunit and impedes its nuclear translocation. J Virol 87:110–123. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00939-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Batra J, Tripathi S, Kumar A, Katz JM, Cox NJ, Lal RB, Sambhara S, Lal SK. 2016. Human heat shock protein 40 (Hsp40/DnaJB1) promotes influenza A virus replication by assisting nuclear import of viral ribonucleoproteins. Sci Rep 6:19063. doi: 10.1038/srep19063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tafforeau L, Chantier T, Pradezynski F, Pellet J, Mangeot PE, Vidalain PO, Andre P, Rabourdin-Combe C, Lotteau V. 2011. Generation and comprehensive analysis of an influenza virus polymerase cellular interaction network. J Virol 85:13010–13018. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02651-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Watanabe T, Kawakami E, Shoemaker JE, Lopes TJ, Matsuoka Y, Tomita Y, Kozuka-Hata H, Gorai T, Kuwahara T, Takeda E, Nagata A, Takano R, Kiso M, Yamashita M, Sakai-Tagawa Y, Katsura H, Nonaka N, Fujii H, Fujii K, Sugita Y, Noda T, Goto H, Fukuyama S, Watanabe S, Neumann G, Oyama M, Kitano H, Kawaoka Y. 2014. Influenza virus-host interactome screen as a platform for antiviral drug development. Cell Host Microbe 16:795–805. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Konig R, Stertz S, Zhou Y, Inoue A, Hoffmann HH, Bhattacharyya S, Alamares JG, Tscherne DM, Ortigoza MB, Liang Y, Gao Q, Andrews SE, Bandyopadhyay S, De Jesus P, Tu BP, Pache L, Shih C, Orth A, Bonamy G, Miraglia L, Ideker T, Garcia-Sastre A, Young JA, Palese P, Shaw ML, Chanda SK. 2010. Human host factors required for influenza virus replication. Nature 463:813–817. doi: 10.1038/nature08699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karlas A, Machuy N, Shin Y, Pleissner KP, Artarini A, Heuer D, Becker D, Khalil H, Ogilvie LA, Hess S, Maurer AP, Muller E, Wolff T, Rudel T, Meyer TF. 2010. Genome-wide RNAi screen identifies human host factors crucial for influenza virus replication. Nature 463:818–822. doi: 10.1038/nature08760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Riis B, Rattan SI, Clark BF, Merrick WC. 1990. Eukaryotic protein elongation factors. Trends Biochem Sci 15:420–424. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(90)90279-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carvalho MD, Carvalho JF, Merrick WC. 1984. Biological characterization of various forms of elongation factor 1 from rabbit reticulocytes. Arch Biochem Biophys 234:603–611. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(84)90310-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Janssen GM, Moller W. 1988. Kinetic studies on the role of elongation factors 1 beta and 1 gamma in protein synthesis. J Biol Chem 263:1773–1778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Chassey B, Aublin-Gex A, Ruggieri A, Meyniel-Schicklin L, Pradezynski F, Davoust N, Chantier T, Tafforeau L, Mangeot PE, Ciancia C, Perrin-Cocon L, Bartenschlager R, Andre P, Lotteau V. 2013. The interactomes of influenza virus NS1 and NS2 proteins identify new host factors and provide insights for ADAR1 playing a supportive role in virus replication. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003440. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dever TE, Green R. 2012. The elongation, termination, and recycling phases of translation in eukaryotes. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 4:a013706. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a013706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sanders J, Raggiaschi R, Morales J, Moller W. 1993. The human leucine zipper-containing guanine-nucleotide exchange protein elongation factor-1 delta. Biochim Biophys Acta 1174:87–90. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(93)90097-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Andersen GR, Pedersen L, Valente L, Chatterjee I, Kinzy TG, Kjeldgaard M, Nyborg J. 2000. Structural basis for nucleotide exchange and competition with tRNA in the yeast elongation factor complex eEF1A:eEF1Balpha. Mol Cell 6:1261–1266. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00122-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sammaibashi S, Yamayoshi S, Kawaoka Y. 2018. Strain-specific contribution of eukaryotic elongation factor 1 gamma to the translation of influenza A virus proteins. Front Microbiol 9:1446. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mansilla F, Friis I, Jadidi M, Nielsen KM, Clark BF, Knudsen CR. 2002. Mapping the human translation elongation factor eEF1H complex using the yeast two-hybrid system. Biochem J 365:669–676. doi: 10.1042/BJ20011681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Albo C, Valencia A, Portela A. 1995. Identification of an RNA binding region within the N-terminal third of the influenza A virus nucleoprotein. J Virol 69:3799–3806. doi: 10.1128/JVI.69.6.3799-3806.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Portela A, Digard P. 2002. The influenza virus nucleoprotein: a multifunctional RNA-binding protein pivotal to virus replication. J Gen Virol 83:723–734. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-4-723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Elton D, Medcalf L, Bishop K, Harrison D, Digard P. 1999. Identification of amino acid residues of influenza virus nucleoprotein essential for RNA binding. J Virol 73:7357–7367. doi: 10.1128/JVI.73.9.7357-7367.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Loucaides EM, von Kirchbach JC, Foeglein A, Sharps J, Fodor E, Digard P. 2009. Nuclear dynamics of influenza A virus ribonucleoproteins revealed by live-cell imaging studies. Virology 394:154–163. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ketha KM, Atreya CD. 2008. Application of bioinformatics-coupled experimental analysis reveals a new transport-competent nuclear localization signal in the nucleoprotein of influenza A virus strain. BMC Cell Biol 9:22. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-9-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Melen K, Fagerlund R, Franke J, Kohler M, Kinnunen L, Julkunen I. 2003. Importin alpha nuclear localization signal binding sites for STAT1, STAT2, and influenza A virus nucleoprotein. J Biol Chem 278:28193–28200. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303571200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gabriel G, Herwig A, Klenk HD. 2008. Interaction of polymerase subunit PB2 and NP with importin alpha1 is a determinant of host range of influenza A virus. PLoS Pathog 4:e11. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0040011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Goldfarb DS, Corbett AH, Mason DA, Harreman MT, Adam SA. 2004. Importin alpha: a multipurpose nuclear-transport receptor. Trends Cell Biol 14:505–514. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]