ABSTRACT

Background

Age-related declines in taste and smell function are widely assumed to contribute to the decrease in appetite and the development of undernutrition in older adults.

Objectives

Here we aim to assess the associations of both taste and smell function with several nutrition-related outcomes in a single study, with poor appetite and undernutrition as primary outcomes.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional cohort study of 359 community-dwelling Dutch older adults, aged 65–93 y. Taste function was measured for all 5 basic tastes. Smell function was assessed with 3 tests: for odor identification, discrimination, and threshold. Self-reported taste and smell, appetite, energy (kcal/d) and macronutrient (% energy) intake, and covariates were assessed with extensive questionnaires. Dietary quality was calculated using the Dutch Healthy Diet index 2015, Alternative Healthy Eating Index 2010, and Mediterranean Diet Score. Body measurements included body weight (current and 2 y prior), height, and body impedance analysis. Data were analyzed via multiple logistic and linear regression.

Results

Of our sample, 9.2% had poor taste and 17.0% poor smell, 6.1% had poor appetite, and 21.4% were undernourished. Self-reported poor taste (OR: 8.44; 95% CI: 1.56, 45.56; P = 0.013) was associated with poor appetite, but no other taste or smell score was associated with either poor appetite or undernutrition. Some associations were found of individual taste and smell scores with macronutrient intake and dietary quality. Self-reported poor taste and smell were both consistently associated with poorer dietary quality.

Conclusions

In community-dwelling older adults, specific taste and smell impairments may have diverse consequences for appetite, food intake, or dietary quality. However, this does not necessarily result in undernutrition. The consistent associations of self-reported poor taste and smell with poor dietary quality do underline the usefulness of this information when screening for nutritional risk.

Keywords: gustatory function, olfactory function, appetite, undernutrition, macronutrient intake, dietary quality, older adults

Introduction

The risk of undernutrition increases with age. It affects 9%–28% of older adults in Europe (1) and is associated with increased morbidity, mortality, and health care costs (2). Important roles in nutritional health are fulfilled by taste (gustatory) and smell (olfactory) functions (3). Taste and smell guide individuals toward nutritious foods and away from harmful, spoiled foods or environmental hazards (4, 5). Moreover, depending on previous experiences, they help to assign positive or negative attributions to certain foods or situations (5, 6), possibly directing future food-related behavior (4). However, an age-related decline has been demonstrated for both olfactory and gustatory function (7–10). This sensory decline is thought to cause decreased food enjoyment, poor appetite, decreased or altered food intake, and ultimately contribute to the increased risk of undernutrition in older adults (3).

Many studies have investigated the association of poor olfactory and gustatory function with undernutrition, but literature on this topic remains inconclusive. Whereas some studies found poor olfactory function to be associated with low BMI (8, 11–13), poor appetite (11, 14), altered macronutrient intake (15, 16), or poor dietary quality (13), others did not (14, 17–19). In this context, poor olfactory function is often operationalized by low scores on odor identification tests (e.g., the Sniffin’ Sticks test, the San Diego Odor Identification test, or the University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test) (8, 11–14, 17, 18), whereas other studies also included threshold tests (16, 19) or self-reported poor smell (15). Studies on the association of gustatory function with nutritional status are limited. In 1 study, gustatory impairment, measured by the Burghart Taste Strip test, tended to be associated with diminished eating pleasure (18), and a second study found thresholds >0.003% wt:wt for bitter taste to be associated with having a BMI (in kg/m2) <18.5 (20). However, 2 other studies did not observe any association between poor gustatory function and BMI (14, 21), energy intake, or appetite (14). Although overall gustatory impairments may not affect total food or energy intake, impairments of specific tastes have been shown to alter food preferences, and thus influence dietary quality: for instance, the increased preference for salty foods in case of diminished salty taste (22). The inconsistency in the literature on sensory impairments and nutrition is likely due to the wide range in study methods, study populations, sensory assessments, and outcome measures across studies. Moreover, a discrepancy between self-reported and observed sensory impairments exists (10, 12, 17, 18).

Here, we present a comprehensive cross-sectional cohort study of 359 Dutch community-dwelling older adults on the association of sensory impairments with nutritional status. We assessed multiple aspects of gustatory and olfactory function, including odor identification, discrimination, and threshold scores, as well as scores for all 5 basic tastes, and self-reported poor taste and smell. As outcome measures we included those most commonly reported on in the literature with poor appetite and undernutrition as the primary outcomes. Because poor appetite is thought to contribute to undernutrition through altered food intake and poor dietary quality, these 2 were used as secondary outcomes. We hypothesize that poor taste and smell scores, as well as self-reported poor taste and smell, are associated with poor appetite, decreased food intake, poorer dietary quality, and increased risk of undernutrition.

Methods

Design

This cross-sectional study was embedded within the ongoing Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam (LASA), which included 3107, 1002, and 1023 Dutch community-dwelling older adults in 1992/1993, 2002/2003, and 2012/2013, respectively. Data on physical, social, emotional, and cognitive functioning are collected in waves every 3 y by means of medical and general interviews, the former also including body measurements. The most recent wave took place in 2015/2016.

The design of the LASA has been described more elaborately elsewhere (23–25). For the current substudy, data were used from the regular LASA cycle 2015/2016 and from an extra home visit, which took place in between regular data-collection waves in 2017/2018. LASA participants who took part in the LASA medical interview of 2015/2016 were prescreened on in- and exclusion criteria based on LASA data. Those who were found eligible were contacted by phone in 2017/2018 and screened on the remainder of the in- and exclusion criteria before the extra home visit was planned. Inclusion criteria for our substudy were age >65 y, valid measurement of body weight in the most recent LASA examination wave (2015/2016), community-dwelling, and living in the Netherlands. Exclusion criteria were overnutrition established either by a BMI >30 or by >2% body weight gain between the 2 latest LASA examination waves (from 2011/2013 to 2015/2016), diagnosed active malignancy, and poor cognitive status defined as a Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) score <18. Because this study was designed to also evaluate differences in oral and gut microbiota between undernourished and well-nourished older adults, participants were also excluded if there were microbiota-disturbing factors like antibiotic use in the previous 3 mo.

Informed consent and all measurements for this ancillary study were obtained during a single home visit. This study was approved by the local ethics committee in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (updated version 2013).

Anthropometrics and undernutrition

Body weight was measured during the home visit using a calibrated scale (Seca, model 100, Lameris), with participants wearing only undergarments or indoors clothing without shoes, in which case 1 kg was subtracted (26). BMI was calculated using the earliest LASA height measurement available, which was obtained with a stadiometer using a standardized protocol. Weight change averaged over the last 2 y (% body weight) was calculated. Undernutrition was defined as low BMI (BMI <20 if age <70 y or BMI <22 if ≥70 y) according to the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism guidelines (27), or >5% body weight loss averaged over 2 y. Body composition was measured by body impedance analysis using the Bodystat 1500MDD device (Bodystat Ltd). Body impedance analysis was done in the supine position. Appendicular Skeletal Muscle Mass Index (ASMMI) was calculated using the formula of Sergi et al. (28) as recommended by the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (29).

Appetite

Appetite was assessed by the 8-item Council of Nutrition Appetite Questionnaire (CNAQ), its score ranging from 8 (worst) to 40 (best). A CNAQ score <28 was considered representative of having a poor appetite (30).

Dietary intake and quality

Energy intake (kcal/d) and macronutrient intake (En%) were measured with the 238-item Dutch version of the FFQ from the HELIUS (Healthy Life in an Urban Setting) study, inquiring into average intake of specific foods and drinks over the previous 4 wk (31). FFQ data were excluded from analyses if unlikely energy intakes of <500 kcal/d or >3500 kcal/d for women, and <800 kcal/d or >4000 kcal/d for men were reported (31).

Three dietary quality indexes were calculated from the FFQ data. First, the Dutch Healthy Diet index 2015 (DHD) has been used previously in the HELIUS study (32) and assesses adherence to Dutch dietary guidelines, scoring the consumption of 15 dietary components from 0 to 10 (33). Because our FFQ does not adequately measure the intake of salt or type of coffee, these components were left out, leaving a potential score from 0 to 130 (32). Second, the Alternative Healthy Eating Index 2010 (AHEI) was previously used in the LASA (34) and scores 11 dietary components from 0 to 10 based on their predictive power for chronic disease (35). Again, the AHEI sodium component was excluded from our study, leaving a total score of 0–100 (34). Third, the Mediterranean Diet Score (MDS), also previously used in the LASA (34), scores 11 dietary components from 0 to 5 to assess the adherence to a typical Mediterranean diet (total score: 0–55) (36). A higher score for all indexes indicates better adherence to a healthy diet (33, 35, 36).

Gustatory function

Gustatory function was assessed using taste strips (Burghart Messtechnik GmbH). This taste test commonly consists of 18 paper taste strips, of which 2 are tasteless and 16 are impregnated with 4 increasing concentrations of sweet, sour, salty, and bitter tastes (37). Upon request, 4 umami taste strips were specially added by Burghart to their standard test, reproducing the taste strip test validated by Mueller et al. (38). The same test design, tastant concentrations, and sequence in which taste strips were presented were used. Participants received 1 point for each correctly identified taste, with each individual taste score ranging from 0 to 4, and the total score ranging from 0 to 20. A total taste score <6, sweet score <2, sour score <2, salty score <2, bitter score <1, or umami score <1 were considered poor taste, thus indicating hypogeusia. Participants were asked not to smoke, chew gum, eat, or drink anything other than water in the hour preceding the taste test. Self-reported taste function was assessed with a single question: “How is your taste function in general?” with the following answering possibilities: “very poor/poor/average/good/very good.” The answers “very poor” and “poor” were considered poor self-reported taste function.

Olfactory function

Olfactory function was measured with Sniffin’ Sticks (Burghart Messtechnik GmbH). The smell test consists of 3 parts: an odor identification test (score: 0–16), an odor discrimination test (score: 0–16), and an odor threshold test (score: 0–16). The scores can be summed to form the Threshold-Discrimination-Identification (TDI) score (39). Each odorant was presented to participants in a felt-tip pen. The test and order in which odors were presented were done according to the manufacturer's directions (39). An identification score ≤9, discrimination score ≤7, threshold score ≤2.5, or TDI score ≤19.5 were considered poor smell, indicating hyposmia (39). Only the smell identification test was performed in all visits and therefore used as our overall measurement for olfactory function, which is common practice (8, 12–14, 17, 18). The additional odor discrimination and threshold tests were not performed in all visits because some participants thought them too burdensome or time-consuming. Moreover, not all researchers conducting the home visits were equipped to perform these tests. Whether participants would take part in the discrimination and threshold tests was decided before the visit based on the participant's preference and researcher available. Self-reported smell function was assessed in all participants with the question: “How is your smell function in general?” The same answering possibilities and cutoff as for self-reported taste function were used.

Covariates

Data on sociodemographics (age, sex, educational status), lifestyle factors (smoking status), health (depression symptoms, medication use), and cognitive status were obtained from the previous LASA examination wave. Educational status was categorized as high, medium, or low. Depressive symptoms were scored using the Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) Scale (40) and cognitive status was assessed with the MMSE (41). Number of medications used was categorized as 0, 1–4, or >4.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SD, median [IQR], or n (%). For univariate analyses, participants were divided into 2 groups according to smell identification score (normosmia and hyposmia) and according to total taste score (normogeusia and hypogeusia). Differences in characteristics were tested using the unpaired Student's t test, Mann–Whitney U test, Fisher's exact test, ANOVA test, or Kruskal–Wallis test, as appropriate.

Then, logistic regression models were run to test the associations of poor total taste score and poor smell identification score with our primary outcomes of undernutrition and poor appetite. These models were tested for effect modification by age, sex, BMI, and smoking status. Next, similar linear models were built to test the associations with the secondary outcomes of food intake and dietary quality. All models were also run for all individual taste and smell scores, as well as self-reported poor taste and smell. Because the taste test was originally designed without the umami flavor, the models were also run using the total taste score excluding umami. Because the individual taste scores are part of the overall taste test, Bonferroni correction for multiple testing was carried out for models with the taste test scores as determinants (total taste, total taste excluding umami, sweet, salty, sour, bitter, and umami). The same was done for models with the smell scores as determinants (TDI, threshold, discrimination, and identification). The Bonferroni-corrected α-levels used for statistical significance were 0.007 (= 0.05/7) and 0.013 (= 0.05/4), respectively. Bonferroni-corrected P values are reported. All regression models were adjusted for age, sex, education, smoking status, medication use, CES-D score, and MMSE score. Finally, to check for selection bias, those unwilling to partake in an extra home visit were compared with those willing based on age, sex, recent weight change, and BMI using the Mann–Whitney U test and Fisher's exact test.

A 2-tailed (corrected) P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS statistics software version 26 (SPSS Inc.).

Results

Study population

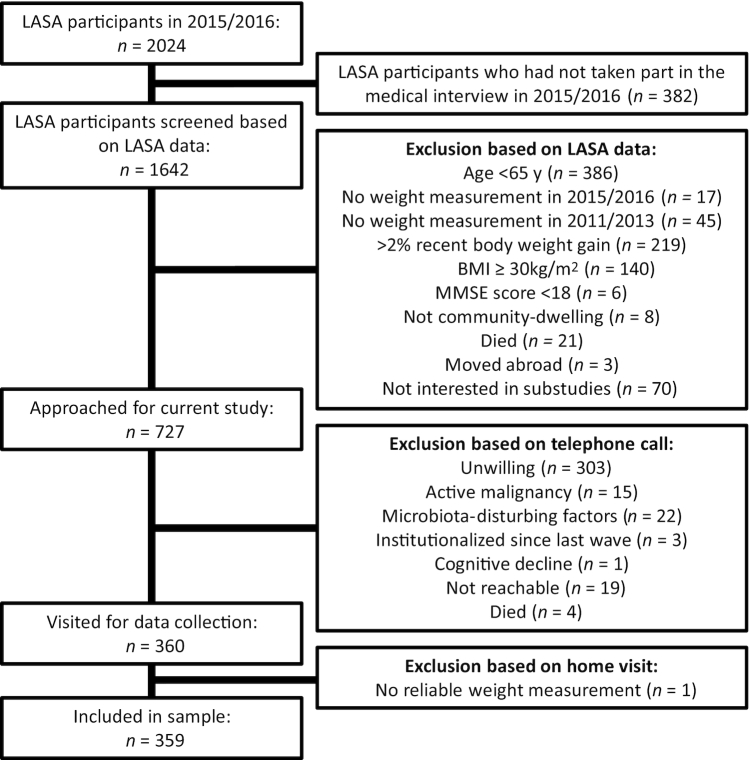

Figure 1 depicts a flowchart of participant inclusion. A total of 360 participants were visited for data collection. However, because 1 participant turned out to be wheelchair-bound and paralytic with highly unreliable weight measurements—which was not revealed before the home visit—359 participants were included in the analytic sample. Table 1 features participant characteristics. The participants’ mean age was 73 y, ranging from 65 to 93 y, and 58.2% were men. A total of 66 participants (18.4%) had poor smell identification score and 33 (9.2%) had poor total taste score. According to our definitions, 77 (21.4%) were undernourished and 22 (6.1%) had poor appetite. Mean ± SD energy intake was 2117 ± 530 kcal/d. Of the LASA participants contacted by phone (n = 727), 303 were unwilling to partake in an extra home visit, whereas 401 were (of whom 41 were later excluded based on the remaining exclusion criteria) (Figure 1). Those unwilling were significantly older (73 compared with 70 y, P < 0.001) and more often male (43.2% compared with 42.9%, P < 0.001) than those willing. BMI and recent weight change were comparable (24.8 compared with 24.9, and −2.6%/3 y compared with −2.0%/3 y).

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart for inclusion of participants. LASA, Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics for all participants and stratified by olfactory and gustatory function1

| n | All | Hyposmia (n = 66) | Normosmia (n = 292) | P value | Hypogeusia (n = 33) | Normogeusia (n = 325) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||||||

| Age, y | 359 | 73 [69–77] | 75 [71–81] | 72 [69–77] | <0.001 | 72 [69–77] | 73 [69–77] | 0.96 |

| Male | 359 | 209 (58.2) | 40 (60.6) | 169 (57.9) | 0.68 | 27 (81.8) | 182 (56.0) | <0.01 |

| Nutritional status | ||||||||

| BMI, kg/m2 | 359 | 24.8 ± 2.5 | 25.0 ± 2.5 | 24.7 ± 2.5 | 0.39 | 25.3 ± 2.8 | 24.7 ± 2.5 | 0.11 |

| Weight difference, %/2 y | 359 | −0.5 ± 4.4 | −1.4 ± 3.9 | −0.3 ± 4.4 | 0.05 | −0.5 ± 4.1 | −0.4 ± 4.5 | 0.94 |

| ASMMI, kg/m2 | 344 | 6.8 ± 0.9 | 6.8 ± 0.9 | 6.8 ± 0.8 | 0.79 | 7.1 ± 0.8 | 6.8 ± 0.9 | 0.04 |

| Undernutrition2 | 359 | 77 (21.4) | 19 (28.8) | 58 (19.9) | 0.10 | 6 (18.2) | 71 (21.8) | 1.00 |

| Poor appetite3 | 358 | 22 (6.1) | 7 (10.6) | 15 (5.2) | 0.24 | 2 (6.1) | 20 (6.2) | 1.00 |

| Food intake | ||||||||

| Energy, kcal/d | 355 | 2117 ± 530 | 2137 ± 643 | 2113 ± 504 | 0.77 | 2210 ± 585 | 2106 ± 525 | 0.30 |

| Carbohydrates, En% | 355 | 41.1 ± 6.7 | 42.7 ± 7.6 | 40.8 ± 6.4 | 0.04 | 42.5 ± 8.1 | 41.0 ± 6.6 | 0.25 |

| Protein, En% | 355 | 14.6 ± 2.3 | 14.0 ± 2.5 | 14.8 ± 2.2 | 0.01 | 14.5 ± 2.1 | 14.6 ± 2.3 | 0.76 |

| Fat, En% | 355 | 34.9 ± 5.7 | 35.2 ± 6.9 | 34.9 ± 5.4 | 0.69 | 33.3 ± 6.7 | 35.1 ± 5.6 | 0.10 |

| Alcohol, En% | 355 | 3.1 [0.6–6.9] | 1.9 [0.3–4.6] | 3.4 [0.8–7.1] | 0.03 | 2.8 [1.0–7.6] | 3.1 [0.5–6.9] | 0.34 |

| DHD | 355 | 83.9 ± 16.2 | 81.6 ± 16.1 | 84.4 ± 16.1 | 0.21 | 78.4 ± 17.9 | 84.5 ± 15.9 | 0.05 |

| AHEI | 355 | 60.8 ± 10.7 | 57.8 ± 10.3 | 61.5 ± 10.7 | 0.01 | 58.6 ± 10.4 | 61.0 ± 10.8 | 0.24 |

| MDS index | 355 | 33.0 ± 4.6 | 32.0 ± 4.9 | 33.2 ± 4.5 | 0.05 | 32.7 ± 4.1 | 33.0 ± 4.7 | 0.69 |

| Taste and smell | ||||||||

| Poor total taste score4 | 358 | 33 (9.2) | 7 (10.6) | 26 (8.9) | 0.81 | — | — | — |

| Poor sweet | 358 | 55 (15.4) | 12 (18.2) | 43 (14.8) | 0.70 | 17 (51.5) | 38 (11.7) | <0.001 |

| Poor sour | 358 | 113 (31.6) | 23 (34.8) | 90 (30.9) | 0.66 | 27 (81.8) | 86 (26.5) | <0.001 |

| Poor salty | 358 | 134 (37.4) | 30 (45.5) | 103 (35.3) | 0.16 | 25 (75.8) | 109 (33.5) | <0.001 |

| Poor bitter | 358 | 28 (7.8) | 9 (13.6) | 19 (6.5) | 0.07 | 14 (42.4) | 14 (4.3) | <0.001 |

| Poor umami | 358 | 116 (32.4) | 25 (37.9) | 91 (31.3) | 0.31 | 21 (63.6) | 95 (29.2) | <0.001 |

| Self-reported poor taste | 359 | 10 (2.8) | 6 (9.1) | 4 (1.4) | <0.01 | 1 (3.0) | 9 (2.8) | 1.00 |

| Poor TDI score5 | 141 | 24 (17.0) | 22 (68.8) | 2 (1.8) | <0.001 | 1 (8.3) | 23 (17.8) | 0.21 |

| Poor T score | 144 | 34 (23.6) | 19 (57.6) | 15 (13.5) | <0.001 | 3 (25.0) | 31 (23.5) | 1.00 |

| Poor D score | 144 | 29 (20.1) | 18 (56.3) | 11 (9.8) | <0.001 | 1 (8.3) | 28 (21.2) | 0.46 |

| Poor I score | 358 | 66 (18.4) | — | — | — | 7 (21.2) | 59 (18.2) | 0.81 |

| Self-reported poor smell | 359 | 21 (5.8) | 11 (16.7) | 10 (3.4) | <0.001 | 4 (12.1) | 17 (5.2) | 0.12 |

| Covariates | ||||||||

| Current smoking | 359 | 27 (7.5) | 4 (6.1) | 23 (7.9) | 0.80 | 4 (12.1) | 23 (7.1) | 0.28 |

| MMSE score | 359 | 29 [28–30] | 28 [27–29] | 29 [28–30] | 0.11 | 29 [27–29] | 29 [28–30] | 0.77 |

| CES-D score | 357 | 4 [2–8] | 6 [3–11] | 4 [2–8] | 0.41 | 4 [1–8] | 5 [2–8] | 0.32 |

| Number of medications | 359 | 0.31 | 0.82 | |||||

| 0 | 98 (27.3) | 13 (19.7) | 85 (29.1) | 7 (21.2) | 90 (27.7) | |||

| 1–4 | 191 (53.2) | 38 (57.6) | 152 (52.1) | 19 (57.6) | 172 (52.9) | |||

| ≥5 | 70 (19.5) | 15 (22.7) | 55 (18.8) | 7 (21.2) | 63 (19.4) | |||

| Education | 359 | 0.04 | 0.70 | |||||

| Low | 39 (10.9) | 7 (10.6) | 32 (11.0) | 5 (15.2) | 34 (10.5) | |||

| Medium | 187 (52.1) | 43 (65.2) | 143 (49.0) | 17 (51.5) | 169 (52.0) | |||

| High | 133 (37.0) | 16 (24.2) | 117 (40.1) | 11 (33.3) | 122 (37.5) | |||

Values are mean ± SD, median [IQR], or n (%) unless otherwise indicated. AHEI, Alternative Healthy Eating Index 2010; ASMMI, Appendicular Skeletal Muscle Mass Index; CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression; DHD, Dutch Healthy Diet index 2015; En%, percentage energy intake; MDS, Mediterranean Diet Score; MMSE, Mini Mental State Examination; TDI, Threshold Discrimination Identification.

Undernutrition: >5% body weight loss averaged over 2 y or BMI <20 (if age <70 y) or BMI <22 (if age >70 y).

Poor appetite: Council of Nutrition Appetite Questionnaire score <28.

Poor taste: total taste score <6, sweet score <2, sour score <2, salty score <2, bitter score <1, or umami score <1.

Poor smell: TDI score ≤19.5, T score ≤2.5, D score ≤7, or I score ≤9.

Hypogeusia compared with normogeusia

Table 1 depicts characteristics stratified by hypogeusia and normogeusia. We found no age difference between participants with hypogeusia and those with normogeusia. BMI and weight change were similar for both gustatory groups, as were the proportions of undernutrition and poor appetite. Participants with hypogeusia were more often male (P < 0.01), which could explain the higher ASMMI in this group (P = 0.04). There was no significant difference in food intake, but hypogeusic participants had a lower DHD score (P = 0.046), indicating worse adherence to Dutch dietary guidelines. There was no difference in the other dietary quality indexes. There was also no difference in the proportion of self-reported poor taste or smell between participants with and without measured hypogeusia. Participants with hypogeusia were not more likely to have hyposmia as well; only 7 participants had both hypogeusia and hyposmia.

Hyposmia compared with normosmia

Table 1 also depicts differences in participant characteristics between hyposmic and normosmic participants. Participants with hyposmia were significantly older (P < 0.001) and lower educated (P = 0.04) than those with normosmia. Hyposmia tended to be associated with more weight loss in the previous 2 y (P = 0.052). There was no statistically significant difference in undernutrition or poor appetite between hyposmic and normosmic participants, although the proportion of poor appetite was double in the hyposmic participants (10.6% compared with 5.2%). Interestingly, even though the total energy intake was similar in both groups, the hyposmic participants consumed significantly less protein (P = 0.01), less alcohol (P = 0.03), and more carbohydrates (P = 0.04) expressed in En% than the normosmic participants. Moreover, participants with hyposmia had worse adherence to healthy diets based on the AHEI (P = 0.01) and tended to have worse adherence to the MDS index (P = 0.051), but not the DHD. Contrary to participants with hypogeusia, participants with hyposmia were more likely to report poor smell (P < 0.001) as well as poor taste (P < 0.01).

Gustatory function

Table 2 shows the associations of taste and smell with poor appetite and undernutrition. After adjustment for potential confounders (i.e., age, sex, education, smoking status, medication use, CES-D score, and MMSE score), there was no association of poor total taste score or any of the individual taste scores with poor appetite or undernutrition. There was no effect modification of age, sex, BMI, or smoking status. Table 3 depicts the associations of taste and smell scores with macronutrient intake. Poor bitter taste score tended to be associated with a higher carbohydrate intake after correction for multiple testing (P = 0.07) and was associated with a lower fat intake expressed in En% (P = 0.02). Poor bitter was, however, not associated with total energy intake. Table 4 depicts the associations of taste and smell scores with dietary quality indexes. Poor umami score tended to be associated with a lower MDS (P = 0.07). No associations were observed with the DHD or AHEI score. Self-reported poor taste was associated with increased risk of poor appetite (P = 0.01) (Table 2), lower protein intake (P = 0.02), higher fat intake (P = 0.04) (Table 3), and with lower scores on all 3 dietary quality indexes (Table 4).

TABLE 2.

Associations of poor taste and smell with poor appetite and undernutrition1

| Poor appetite2 | P value3 | Undernutrition4 | P value3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poor total taste score5 | 1.04 (0.19, 5.76) | 1.00 | 1.15 (0.43, 3.05) | 1.00 |

| Poor total taste score (no umami) | 1.78 (0.33, 9.60) | 1.00 | 1.58 (0.58, 4.31) | 1.00 |

| Poor sweet score | 0.64 (0.14, 2.96) | 1.00 | 0.83 (0.38, 1.83) | 1.00 |

| Poor sour score | 0.90 (0.29, 2.79) | 1.00 | 0.80 (0.44, 1.46) | 1.00 |

| Poor salty score | 1.78 (0.62, 5.07) | 1.00 | 1.27 (0.73, 2.23) | 1.00 |

| Poor bitter score | 0.25 (0.02, 2.78) | 1.00 | 0.71 (0.22, 2.31) | 1.00 |

| Poor umami score | 0.68 (0.21, 2.19) | 1.00 | 0.84 (0.46, 1.53) | 1.00 |

| Self-reported poor taste | 8.44 (1.56, 45.56) | 0.01 | 2.11 (0.49, 9.04) | 0.32 |

| Poor smell identification score6 | 1.50 (0.48, 4.71) | 1.00 | 1.35 (0.69, 2.62) | 1.00 |

| Poor TDI score | 3.67 (0.78, 17.19) | 0.40 | 2.02 (0.73, 5.58) | 0.68 |

| Poor smell threshold score | 4.71 (1.11, 19.91) | 0.16 | 1.85 (0.77, 4.44) | 0.68 |

| Poor smell discrimination score | 0.15 (0.02, 1.26) | 0.32 | 0.99 (0.38, 2.57) | 1.00 |

| Self-reported poor smell | 2.31 (0.50, 10.74) | 0.29 | 0.85 (0.27, 2.68) | 0.78 |

Values are ORs (95% CIs) or P values. All models adjusted for age, sex, educational status, smoking status, medication, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression score, and Mini Mental State Examination score. TDI, threshold-discrimination-identification.

Poor appetite: Council of Nutrition Appetite Questionnaire score <28.

P values for the individual taste and smell scores are adjusted according to Bonferroni correction; P values for self-reported taste and smell are unadjusted.

Undernutrition: >5% body weight loss averaged over 2 y or BMI (in kg/m2) <20 (if age <70 y) or <22 (if age >70 y).

Poor taste: total taste score <6, total taste score (umami excluded) <5, sweet score <2, sour score <2, salty score <2, bitter score <1, or umami score <1.

Poor smell: TDI score ≤19.5, T score ≤2.5, D score ≤7, or I score ≤9.

TABLE 3.

Associations of poor taste and smell with energy and macronutrient intake1

| Energy intake, kcal/d | Carbohydrate intake, En% | Protein intake, En% | Fatty acid intake, En% | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (95% CI) | P value2 | β (95% CI) | P value2 | β (95% CI) | P value2 | β (95% CI) | P value2 | |

| Poor total taste score3 | 34.32 (−153.59, 222.23) | 1.00 | 1.52 (−0.93, 3.97) | 1.00 | 0.14 (−0.70, 0.98) | 1.00 | −1.72 (−3.86, 0.42) | 0.77 |

| Poor total taste score (no umami) | 7.00 (−196.30, 210.30) | 1.00 | 1.54 (−1.11, 4.19) | 1.00 | 0.12 (−0.79, 1.03) | 1.00 | −1.19 (−3.50, 1.13) | 1.00 |

| Poor sweet score | 23.28 (−125.03, 171.58) | 1.00 | −0.47 (−2.40, 1.47) | 1.00 | −0.61 (−1.27, 0.05) | 0.49 | 0.78 (−0.91, 2.47) | 1.00 |

| Poor sour score | 94.52 (−19.44, 208.48) | 0.70 | 0.83 (−0.67, 2.32) | 1.00 | 0.32 (−0.19, 0.83) | 1.00 | −1.21 (−2.51, 0.09) | 0.49 |

| Poor salty score | −96.97 (−206.79, 12.84) | 0.56 | 0.63 (−0.81, 2.06) | 1.00 | 0.08 (−0.42, 0.57) | 1.00 | −0.57 (−1.83, 0.69) | 1.00 |

| Poor bitter score | −97.81 (−301.16, 105.54) | 1.00 | 3.39 (0.75, 6.02) | 0.07 | 0.57 (−0.34, 1.48) | 1.00 | −3.45 (−5.76, −1.17) | 0.02 |

| Poor umami score | −99.02 (−214.55, 16.52) | 0.63 | −0.91 (−2.42, 0.60) | 1.00 | 0.38 (−0.14, 0.90) | 1.00 | 0.26 (−1.07, 1.58) | 1.00 |

| Self-reported poor taste | −251.40 (−578.77, 75.97) | 0.13 | −0.36 (−4.64, 3.92) | 0.87 | −1.71 (−3.16, −0.26) | 0.02 | 3.89 (0.17, 7.61) | 0.04 |

| Poor smell identification score4 | 23.82 (−116.68, 164.31) | 1.00 | 1.37 (−0.46, 3.20) | 0.56 | −0.70 (−1.32, −0.08) | 0.12 | 0.51 (−1.09, 2.10) | 1.00 |

| Poor TDI score | 187.52 (−48.21, 423.25) | 0.48 | 0.18 (−2.81, 3.16) | 1.00 | −0.34 (−1.44, 0.76) | 1.00 | 0.55 (−2.32, 3.43) | 1.00 |

| Poor smell threshold score | −60.00 (−259.87, 139.87) | 1.00 | 0.95 (−1.61, 3.50) | 1.00 | −0.65 (−1.58, 0.28) | 0.68 | −0.58 (−2.99, 1.83) | 1.00 |

| Poor smell discrimination score | 85.49 (−120.30, 291.29) | 1.00 | −0.41 (−3.00, 2.18) | 1.00 | −0.47 (−1.43, 0.48) | 1.00 | 0.19 (−2.31, 2.69) | 1.00 |

| Self-reported poor smell | −79.50 (−307.09, 148.09) | 0.49 | −0.02 (−2.99, 2.95) | 0.99 | −0.81 (−1.82, 0.20) | 0.12 | 1.05 (−1.54, 3.64) | 0.43 |

Values are regression coefficients (β), 95% CIs, or P values. All models adjusted for age, sex, educational status, smoking status, medication, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression score, and Mini Mental State Examination score. En%, percentage energy intake; TDI, threshold-discrimination-identification.

P values for the individual taste and smell scores are adjusted according to Bonferroni correction; P values for self-reported taste and smell are unadjusted.

Poor taste: total taste score <6, total taste score (umami excluded) <5, sweet score <2, sour score <2, salty score <2, bitter score <1, or umami score <1.

Poor smell: TDI score ≤19.5, T score ≤2.5, D score ≤7, or I score ≤9.

TABLE 4.

Associations of poor taste and smell with dietary quality indexes1

| Dutch Healthy Diet index | Alternative Healthy Eating Index | Mediterranean Diet Score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (95% CI) | P value2 | β (95% CI) | P value2 | β (95% CI) | P value2 | |

| Poor total taste score3 | −2.51 (−8.17, 3.14) | 1.00 | −0.57 (−4.44, 3.30) | 1.00 | 0.17 (−1.50, 1.84) | 1.00 |

| Poor total taste score (no umami) | −0.46 (−6.58, 5.66) | 1.00 | 1.46 (−2.73, 5.64) | 1.00 | 0.30 (−1.51, 2.11) | 1.00 |

| Poor sweet score | 0.09 (−4.38, 4.56) | 1.00 | 1.59 (−1.46, 4.64) | 1.00 | 1.41 (0.10, 2.72) | 0.28 |

| Poor sour score | 1.03 (−2.43, 4.50) | 1.00 | 0.45 (−1.91, 2.80) | 1.00 | 1.00 (−0.01, 2.01) | 0.35 |

| Poor salty score | −1.65 (−4.99, 1.69) | 1.00 | −0.78 (−3.05, 1.49) | 1.00 | −0.53 (−1.51, 0.45) | 1.00 |

| Poor bitter score | −1.18 (−7.32, 4.95) | 1.00 | −1.98 (−6.17, 2.21) | 1.00 | −0.84 (−2.65, 0.97) | 1.00 |

| Poor umami score | −3.39 (−6.88, 0.10) | 0.42 | −1.57 (−3.95, 0.81) | 1.00 | −1.39 (−2.41, −0.37) | 0.07 |

| Self-reported poor taste | −14.75 (−24.55, −4.95) | <0.01 | −7.27 (−13.97, −0.57) | 0.03 | −3.44 (−6.33, −0.55) | 0.02 |

| Poor smell identification score4 | −0.56 (−4.80, 3.67) | 1.00 | −2.25 (−5.12, 0.62) | 0.48 | −0.58 (−1.82, 0.66) | 1.00 |

| Poor TDI score | 0.40 (−7.30, 8.10) | 1.00 | −1.17 (−6.13, 3.79) | 1.00 | 0.32 (−2.11, 2.75) | 1.00 |

| Poor smell threshold score | −5.73 (−12.16, 0.71) | 0.32 | −3.14 (−7.24, 0.96) | 0.52 | −0.91 (−2.91, 1.10) | 1.00 |

| Poor smell discrimination score | −3.30 (−10.08, 3.49) | 1.00 | −2.73 (−7.07, 1.62) | 0.88 | −0.38 (−2.49, 1.73) | 1.00 |

| Self-reported poor smell | −8.60 (−15.42, −1.79) | 0.01 | −6.05 (−10.68, −1.42) | 0.01 | −2.25 (−4.25, −0.24) | 0.03 |

Values are regression coefficients (β), 95% CIs, or P values. All models adjusted for age, sex, educational status, smoking status, medication, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression score, and Mini Mental State Examination score. TDI, threshold-discrimination-identification.

P values for the individual taste and smell scores are adjusted according to Bonferroni correction; P values for self-reported taste and smell are unadjusted.

Poor taste: total taste score <6, total taste score (umami excluded) <5, sweet score <2, sour score <2, salty score <2, bitter score <1, or umami score <1.

Poor smell: TDI score ≤19.5, T score ≤2.5, D score ≤7, or I score ≤9.

Olfactory function

None of the smell scores, nor self-reported poor smell, were associated with either poor appetite or undernutrition (Table 2). There was no effect modification by age, sex, BMI, or smoking status. There was also no association with daily energy intake, macronutrient intake (Table 3), or dietary quality scores (Table 4). Poor smell identification score seemed to be associated with lower protein intake, but this association was rendered nonsignificant after Bonferroni correction for multiple testing. However, similarly to self-reported poor taste, self-reported poor smell was consistently associated with lower scores on all 3 dietary quality indexes (Table 4).

Discussion

In this study we evaluated the relations of both self-reported and measured olfactory and gustatory function with poor appetite, food intake, dietary quality, and undernutrition. As for our primary outcomes, we only found an association of self-reported poor taste with poor appetite. None of the other taste or smell scores were associated with either poor appetite or undernutrition. We did find some associations for individual scores, as well as self-reported poor taste and smell function, with macronutrient intake and dietary quality. However, several associations lost statistical significance after adjustment for confounders or correction for multiple testing. Our results are discussed in more detail in the following sections.

Gustatory function

Poor overall gustatory function was not associated with any of our outcome measures, nor with older age. This is in agreement with earlier studies (14, 18), but contradicts the widely accepted assumption that overall poor gustatory function contributes to the age-related decline in appetite and increased risk of undernutrition (3). Possibly, hypogeusia was not associated with age because the population consisted of older adults only. Furthermore, poor overall gustatory function may not be associated with any of the outcomes because the order and severity in which the 5 basic tastes are affected can vary widely across hypogeusic participants. However, generally, umami seems to be affected most, followed by salty or sour, and sweet or bitter (7). This trend was somewhat present in our population with the exception of salty taste being more often affected than umami (in 37.4% of participants compared with 32.4%). Implications for food intake or dietary behavior will depend on the tastes that are most affected in an individual (42). Moreover, taste-related shifts in food preference may not be perceived as having poor appetite per se, or affect total energy content of the diet and result in undernutrition.

We found that poor bitter taste tended to be associated with higher carbohydrate intake and was associated with lower fatty acid intake. Still, neither poor bitter taste nor any of the other taste scores were associated with total daily energy intake. Participants with poor umami taste tended to score 1.4 points lower on the MDS index (P = 0.07), meaning they had lower adherence to a typical Mediterranean diet than did participants with normal umami taste. Contrarily, participants with poor sweet taste scored on average 1.4 points higher on the MDS index, but this was rendered nonsignificant after adjustment for multiple testing (P = 0.28). The umami flavor is highly abundant in many components of the Mediterranean diet, like vegetables, potatoes, and seafood (43). A diminished umami taste could make these foods taste bland and less attractive, thus explaining the trend toward a lower MDS. As such, our findings do support the hypothesis that umami is important for compliance to a healthy diet (42, 44).

Olfactory function

In our univariate analyses, hyposmia (i.e., poor smell identification) was associated with various nutritional variables. Participants with hyposmia were ∼3 y older and tended to have more weight loss. Moreover, they had lower protein and alcohol and higher carbohydrate intake. They also scored lower on the AHEI and MDS diet indexes. Although the association with less protein intake was moderate (0.8 En% less protein in hyposmic than in normosmic participants, P = 0.01), this finding must not be underestimated because lower protein intake may contribute to the risk of frailty and disability in older adults (45–47). In our multivariate models, however, significance was lost after correction for multiple testing. Finally, in a previous study, we hypothesized that perceiving an odor (i.e., odor threshold function) is more important for food-related behavior and appetite than being able to identify it (12). On first glance, this hypothesis did not hold true because poor threshold score was not associated with any of our outcomes. However, the association of poor threshold score with poor appetite (OR: 4.7; 95% CI: 1.11, 19.91) was only rendered nonsignificant after adjustment for multiple testing (P = 0.16). The relatively large OR, combined with the relatively wide 95% CI, does suggest the analysis was underpowered, possibly owing to the low number of participants with poor appetite (n = 22).

Self-reported taste and smell impairments

An important finding of this study was that poor self-reported taste and smell were both consistently associated with lower scores on all 3 dietary quality indexes, which are related to nutrition-related health conditions (33, 35, 36). For future research, it would be interesting to evaluate whether specific food components of the dietary quality scores are responsible for these associations. Poor self-reported taste was in addition associated with poor appetite, lower protein intake, and higher fat intake. In prior studies, the prevalence of self-reported sensory impairments was consistently lower than that of objectively assessed sensory impairments. It was therefore suggested that self-reported measures suffer from underreporting and are of limited clinical importance (12, 17, 18). Our study challenges this assumption. Possibly, a participant will only report impaired olfactory or gustatory function if the impairment is of a certain severity, which may not correlate to the epidemiological cutoffs used in the definitions for measured sensory impairments (37, 39). The clinical relevance of subjective assessments is further emphasized by the fact that many clinicians lack access to expensive sensory tests. Our results suggest that asking older adults for sensory impairments can be of added value in screening for nutritional risk. Once identified, impairments may then be addressed by appropriate dietary counselling or the implementation of taste enhancers, which was shown to increase body weight and hunger feelings in some (48, 49) but not all studies (50).

Strengths and limitations

The most important strength of this study is the various aspects of taste and smell assessed, which gave us a comprehensive view of our participants’ sensory status. Similarly, we assessed various nutrition-related outcomes. Our study enabled us to consider all these associations simultaneously in a single population, without needing to consider the comparability of several populations or studies. Owing to the richness of the LASA data set, we could adjust for numerous covariates in our multivariate models, although residual confounding cannot be excluded. Finally, we extended our taste test with the relatively newly discovered umami flavor, which is a novel aspect in comparison with earlier gustatory studies.

There are some limitations to consider. First, this was a cross-sectional study and no causal relations can be demonstrated. Second, we did not have information on how long any sensory impairments had been present. Possibly, long-term sensory impairments would not have affected our outcomes because participants may have adjusted to these impairments for many years. Conversely, if sensory declines were more recent, undernutrition may not have manifested itself yet. Longitudinal studies are needed to elucidate this. Third, our taste test could not distinguish between hypogeusia and dysgeusia (i.e., distorted, rather than diminished, taste function). These 2 taste disorders may have contrary effects on an individual. Fourth, because our FFQ did not assess the amount of salt added to foods by participants, the sodium components of the DHD and AHEI were left out of the dietary quality scores. Therefore, the associations between poor salty taste and these dietary quality scores may be underestimated. Moreover, even though the HELIUS FFQ was recently validated in 88 older adults of the LASA cohort and found acceptable for use (51), precise estimations of food intake remain prone to measurement error. Fifth, in our study the prevalence of self-reported poor taste, self-reported poor smell, and poor appetite was rather low. Some of the analyses concerning these variables may have been underpowered. We also cannot exclude the possibility of selection bias because LASA participants who were willing to partake in our ancillary study were younger and more often women than those unwilling. Because age and sex are associated with hyposmia and hypogeusia, respectively, chemosensory impairments may have been underrepresented in our analytic sample compared with the general LASA population. However, BMI and recent weight change were comparable. Based on our definition of undernutrition, we also cannot say for certain that participants were truly undernourished (e.g., participants may have had healthy BMIs of ∼20 for most their lives and then turned 70 y old). However, those who were undernourished had a mean ± SD BMI of 22.7 ± 2.3, 2-y weight difference of −4.0 ± 5.7, and ASMMI of 6.2 ± 0.7. Those who were not undernourished had a higher BMI, less weight loss, and higher ASMMI of 25.3 ± 2.3, 0.5 ± 3.5, and 7.0 ± 0.8, respectively. These do constitute significant differences (Student's t test P values < 0.001). Future studies may benefit from a more elaborate undernutrition assessment.

Conclusion

Self-reported poor taste and smell were both consistently associated with poor dietary quality. Self-reported poor taste was in addition associated with poor appetite, lower protein intake, and higher fat intake. None of the objective taste and smell scores were associated with poor appetite or undernutrition, although some trends and associations with food intake and dietary quality could be found. Our results suggest that poor taste or smell in older adults do have some consequences for food preference or intake, but this may not necessarily be perceived as poor appetite, or result in decreased energy intake and subsequent development of undernutrition. The consistent associations of self-reported sensory impairments with poor dietary quality do underline the usefulness of this information when screening for nutritional risk.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—KSF, MN, BJFK, and MV: designed the research; KSF, ACH, and RFK: conducted the research; KSF, RGI, and MV: analyzed the data; KSF: wrote the paper; and all authors: read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

The data underlying this article cannot be shared publicly due to the privacy of individuals that participated in the study. The data will be shared on reasonable request to the LASA cohort (https://lasa-vu.nl).

Notes

Supported by European Union Horizon 2020 PROMISS project “PRevention Of Malnutrition In Senior Subjects in the EU” grant agreement 678732 (to MV). The content only reflects the authors’ view and the Commission is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains. The Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam is supported by a grant from the Netherlands Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport, Directorate of Long-Term Care.

Author disclosures: the authors report no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations used: AHEI, Alternative Healthy Eating Index 2010; ASMMI, Appendicular Skeletal Muscle Mass Index; CES-D, Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; CNAQ, Council of Nutrition Appetite Questionnaire; DHD, Dutch Healthy Diet index 2015; En%, percentage energy intake; HELIUS, Healthy Life in an Urban Setting; LASA, Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam; MDS, Mediterranean Diet Score; MMSE, Mini Mental State Examination; TDI, Threshold-Discrimination-Identification score.

Contributor Information

Kristina S Fluitman, Department of Internal Medicine, Amsterdam University Medical Centers, Amsterdam, Netherlands; Amsterdam Public Health Research Institute, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Anne C Hesp, Department of Internal Medicine, Amsterdam University Medical Centers, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Rachel F Kaihatu, Department of Internal Medicine, Amsterdam University Medical Centers, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Max Nieuwdorp, Department of Internal Medicine, Amsterdam University Medical Centers, Amsterdam, Netherlands; Department of Vascular Medicine, Amsterdam University Medical Centers, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Bart J F Keijser, Department of Microbiology and Systems Biology, TNO Earth, Life and Social Sciences, Zeist, Netherlands; Department of Preventive Dentistry, Academic Center for Dentistry Amsterdam, University of Amsterdam and VU University, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Richard G IJzerman, Department of Internal Medicine, Amsterdam University Medical Centers, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Marjolein Visser, Amsterdam Public Health Research Institute, Amsterdam, Netherlands; Department of Health Sciences, Faculty of Science, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

References

- 1. Leij-Halfwerk S, Verwijs MH, van Houdt S, Borkent JW, Guaitoli PR, Pelgrim T, Heymans MW, Power L, Visser M, Corish CA et al. Prevalence of protein-energy malnutrition risk in European older adults in community, residential and hospital settings, according to 22 malnutrition screening tools validated for use in adults ≥65 years: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Maturitas. 2019;126:80–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Correia MI, Waitzberg DL. The impact of malnutrition on morbidity, mortality, length of hospital stay and costs evaluated through a multivariate model analysis. Clin Nutr. 2003;22(3):235–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wysokinski A, Sobow T, Kloszewska I, Kostka T. Mechanisms of the anorexia of aging—a review. Age (Dordr). 2015;37(4):81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hummel T, Nordin S. Olfactory disorders and their consequences for quality of life. Acta Otolaryngol. 2005;125(2):116–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Breslin PA. An evolutionary perspective on food and human taste. Curr Biol. 2013;23(9):R409–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sarafoleanu C, Mella C, Georgescu M, Perederco C. The importance of the olfactory sense in the human behavior and evolution. J Med Life. 2009;2(2):196–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Methven L, Allen VJ, Withers CA, Gosney MA. Ageing and taste. Proc Nutr Soc. 2012;71(4):556–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Karpa MJ, Gopinath B, Rochtchina E, Jie Jin W, Cumming RG, Sue CM, Mitchell P. Prevalence and neurodegenerative or other associations with olfactory impairment in an older community. J Aging Health. 2010;22(2):154–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rawal S, Hoffman HJ, Bainbridge KE, Huedo-Medina TB, Duffy VB. Prevalence and risk factors of self-reported smell and taste alterations: results from the 2011–2012 US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Chem Senses. 2016;41(1):69–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Murphy C, Schubert CR, Cruickshanks KJ, Klein BE, Klein R, Nondahl DM. Prevalence of olfactory impairment in older adults. JAMA. 2002;288(18):2307–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Seubert J, Laukka EJ, Rizzuto D, Hummel T, Fratiglioni L, Bäckman L, Larsson M. Prevalence and correlates of olfactory dysfunction in old age: a population-based study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017;72(8):1072–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fluitman KS, Nadar HJ, Roos DS, Berendse HW, Keijser BJF, Nieuwdorp M, IJzerman RG, Visser M. The association of olfactory function with BMI, appetite, and prospective weight change in Dutch community-dwelling older adults. J Nutr Health Aging. 2019;23(8):746–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gopinath B, Russell J, Sue CM, Flood VM, Burlutsky G, Mitchell P. Olfactory impairment in older adults is associated with poorer diet quality over 5 years. Eur J Nutr. 2016;55(3):1081–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. de Jong N, Mulder I, de Graaf C, van Staveren WA. Impaired sensory functioning in elders: the relation with its potential determinants and nutritional intake. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1999;54(8):B324–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kong IG, Kim SY, Kim M-S, Park B, Kim J-H, Choi HG. Olfactory dysfunction is associated with the intake of macronutrients in Korean adults. PLoS One. 2016;11(10):e0164495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Duffy VB, Backstrand JR, Ferris AM. Olfactory dysfunction and related nutritional risk in free-living, elderly women. J Am Diet Assoc. 1995;95(8):879–84.; quiz 885–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Smoliner C, Fischedick A, Sieber CC, Wirth R. Olfactory function and malnutrition in geriatric patients. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68(12):1582–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Arganini C, Sinesio F. Chemosensory impairment does not diminish eating pleasure and appetite in independently living older adults. Maturitas. 2015;82(2):241–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Toussaint N, de Roon M, van Campen JP, Kremer S, Boesveldt S. Loss of olfactory function and nutritional status in vital older adults and geriatric patients. Chem Senses. 2015;40(3):197–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fuchida S, Yamamoto T, Takiguchi T, Kandaudahewa G, Yuyama N, Hirata Y. Association between underweight and taste sensitivity in middle- to old-aged nursing home residents in Sri Lanka: a cross-sectional study. J Oral Rehabil. 2013;40(11):854–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liu G, Zong G, Doty RL, Sun Q. Prevalence and risk factors of taste and smell impairment in a nationwide representative sample of the US population: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(11):e013246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sergi G, Bano G, Pizzato S, Veronese N, Manzato E. Taste loss in the elderly: possible implications for dietary habits. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2017;57(17):3684–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hoogendijk EO, Deeg DJ, Poppelaars J, van der Horst M, Broese van Groenou MI, Comijs HC, Pasman HR, van Schoor NM, Suanet B, Thomese F et al. The Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam: cohort update 2016 and major findings. Eur J Epidemiol. 2016;31(9):927–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Huisman M, Poppelaars J, van der Horst M, Beekman AT, Brug J, van Tilburg TG, Deeg DJ. Cohort profile: the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40(4):868–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hoogendijk EO, Deeg DJH, de Breij S, Klokgieters SS, Kok AAL, Stringa N, Timmermans EJ, van Schoor NM, van Zutphen EM, van der Horst M et al. The Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam: cohort update 2019 and additional data collections. Eur J Epidemiol. 2020;35(1):61–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Whigham LD, Schoeller DA, Johnson LK, Atkinson RL. Effect of clothing weight on body weight. Int J Obes. 2013;37(1):160–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cederholm T, Bosaeus I, Barazzoni R, Bauer J, Van Gossum A, Klek S, Muscaritoli M, Nyulasi I, Ockenga J, Schneider SM et al. Diagnostic criteria for malnutrition – an ESPEN Consensus Statement. Clin Nutr. 2015;34(3):335–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sergi G, De Rui M, Veronese N, Bolzetta F, Berton L, Carraro S, Bano G, Coin A, Manzato E, Perissinotto E. Assessing appendicular skeletal muscle mass with bioelectrical impedance analysis in free-living Caucasian older adults. Clin Nutr. 2015;34(4):667–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J, Boirie Y, Bruyère O, Cederholm T, Cooper C, Landi F, Rolland Y, Sayer AA et al. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing. 2019;48(1):16–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hanisah R, Suzana S, Lee FS. Validation of screening tools to assess appetite among geriatric patients. J Nutr Health Aging. 2012;16(7):660–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Beukers MH, Dekker LH, de Boer EJ, Perenboom CW, Meijboom S, Nicolaou M, de Vries JH, Brants HA. Development of the HELIUS food frequency questionnaires: ethnic-specific questionnaires to assess the diet of a multiethnic population in The Netherlands. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2015;69(5):579–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mackenbach JD, Dijkstra SC, Beulens JWJ, Seidell JC, Snijder MB, Stronks K, Monsivais P, Nicolaou M. Socioeconomic and ethnic differences in the relation between dietary costs and dietary quality: the HELIUS study. Nutr J. 2019;18(1):21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Looman M, Feskens EJ, de Rijk M, Meijboom S, Biesbroek S, Temme EH, de Vries J, Geelen A. Development and evaluation of the Dutch Healthy Diet index 2015. Public Health Nutr. 2017;20(13):2289–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Elstgeest LEM, Winkens LHH, Penninx B, Brouwer IA, Visser M. Associations of depressive symptoms and history with three a priori diet quality indices in middle-aged and older adults. J Affect Disord. 2019;249:394–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chiuve SE, Fung TT, Rimm EB, Hu FB, McCullough ML, Wang M, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC. Alternative dietary indices both strongly predict risk of chronic disease. J Nutr. 2012;142(6):1009–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Panagiotakos DB, Pitsavos C, Arvaniti F, Stefanadis C. Adherence to the Mediterranean food pattern predicts the prevalence of hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes and obesity, among healthy adults; the accuracy of the MedDietScore. Prev Med. 2007;44(4):335–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Landis BN, Welge-Luessen A, Bramerson A, Bende M, Mueller CA, Nordin S, Hummel T. “Taste Strips” – a rapid, lateralized, gustatory bedside identification test based on impregnated filter papers. J Neurol. 2009;256(2):242–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mueller CA, Pintscher K, Renner B. Clinical test of gustatory function including umami taste. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2011;120(6):358–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hummel T, Kobal G, Gudziol H, Mackay-Sim A. Normative data for the “Sniffin’ Sticks” including tests of odor identification, odor discrimination, and olfactory thresholds: an upgrade based on a group of more than 3,000 subjects. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;264(3):237–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Radloff L. The CES-D scale: a self-reported depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Imoscopi A, Inelmen EM, Sergi G, Miotto F, Manzato E. Taste loss in the elderly: epidemiology, causes and consequences. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2012;24(6):570–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kurihara K, Kashiwayanagi M. Physiological studies on umami taste. J Nutr. 2000;130(4S Suppl):931S–4S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sasano T, Satoh-Kuriwada S, Shoji N, Iikubo M, Kawai M, Uneyama H, Sakamoto M. Important role of umami taste sensitivity in oral and overall health. Curr Pharm Des. 2014;20(16):2750–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mendonça N, Kingston A, Granic A, Hill TR, Mathers JC, Jagger C. Contribution of protein intake and its interaction with physical activity to transitions between disability states and to death in very old adults: the Newcastle 85+ Study. Eur J Nutr. 2020;59(5):1909–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mendonça N, Kingston A, Granic A, Jagger C. Protein intake and transitions between frailty states and to death in very old adults: the Newcastle 85+ study. Age Ageing. 2020;49(1):32–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Houston DK, Tooze JA, Garcia K, Visser M, Rubin S, Harris TB, Newman AB, Kritchevsky SB. Protein intake and mobility limitation in community-dwelling older adults: the Health ABC Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017:65(8):1705–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Mathey MF, Siebelink E, de Graaf C, Van Staveren WA. Flavor enhancement of food improves dietary intake and nutritional status of elderly nursing home residents. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(4):M200–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bautista EN, Tanchoco CC, Tajan MG, Magtibay EV. Effect of flavor enhancers on the nutritional status of older persons. J Nutr Health Aging. 2013;17(4):390–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Essed NH, van Staveren WA, Kok FJ, de Graaf C. No effect of 16 weeks flavor enhancement on dietary intake and nutritional status of nursing home elderly. Appetite. 2007;48(1):29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Visser M, Elstgeest LEM, Winkens LHH, Brouwer IA, Nicolaou M. Relative validity of the HELIUS food frequency questionnaire for measuring dietary intake in older adult participants of the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam. Nutrients. 2020;12(7):1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]