Abstract

Background

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a potentially fatal disease that is of great global public health concern.

Objective

We explored the clinical management of inpatients with COVID-19 in Italy.

Methods

A self-administered survey was sent by email to Italian physicians caring for adult patients with COVID-19. A panel of experts was selected according to their clinical curricula and their responses were analyzed.

Results

A total of 1,215 physicians completed the survey questionnaire (17.4% response rate). Of these, 188 (15.5%) were COVID-19 experts. Chest computed tomography was the most used method to detect and monitor COVID-19 pneumonia. Most of the experts managed acute respiratory failure with CPAP (56.4%), high flow nasal cannula (18.6%), and non-invasive mechanical ventilation (8%), while an intensivist referral for early intubation was requested in 17% of the cases. Hydroxychloroquine was prescribed as an antiviral in 90% of cases, both as monotherapy (11.7%), and combined with protease inhibitors (43.6%) or azithromycin (36.2%). The experts unanimously prescribed low-molecular-weight heparin to patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia, and half of them (51.6%) used a dose higher than standard. The respiratory burden in patients who survived the acute phase was estimated as relevant in 28.2% of the cases, modest in 39.4%, and negligible in 9%.

Conclusions

In our survey some major topics, such as the role of non-invasive respiratory support and drug treatments, show disagreement between experts, likely reflecting the absence of high-quality evidence studies. Considering the significant respiratory sequelae reported following COVID-19, proper respiratory and physical therapy programs should be promptly made available.

Keywords: COVID-19, Acute respiratory failure, Pandemic, Pneumonia, Mechanical ventilation, Rehabilitation, Steroid, Pandemic

Introduction

In December 2019, a novel coronavirus (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; Sars-CoV-2) emerged in China and has since spread globally, creating a pandemic [1]. Italy was severely affected and soon became the first most affected nation among Western countries [2]. The pandemic represents a particular burden for physicians, who are faced with making crucial clinical decisions for a novel disease, whilst balancing risk management in the context of a lack of sufficient resources and equipment [3]. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) creates high rates of hospitalization among infected patients, with frequent need for respiratory support consisting of oxygen supplementation and non-invasive or invasive mechanical ventilation [4]. Gattinoni et al. [5] recently challenged the previous recommendation that COVID-19 pneumonia be treated as acute respiratory distress syndrome (Surviving Sepsis Campaign COVID) due to the little to no reductions in respiratory system compliance displayed by these patients, suggesting COVID-19 be considered a distinct disease. Along with Tobin [6], he endorsed a more parsimonious use of intubation and mechanical ventilation, especially in the early stages of the disease, in which oxygen supplementation, or non-invasive options [high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC), continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), non-invasive ventilation (NIV)] should be considered, and with fewer complications [5, 6].

From a pharmaceutical standpoint, there are several treatments currently being evaluated for COVID-19. Some of these regimens are available for other indications, and have therefore been implemented in clinical practice, despite their use for COVID-19 remaining investigational. To date, no therapies undergoing testing have proven to be clearly effective, and likewise, data regarding the safety of these medications are still lacking [7]. If the clinical treatment of COVID-19 patients were not challenging enough, it is sadly only one of the aspects clinicians have to face daily.

First amid Western countries, the Italian healthcare system was stretched beyond capacity by the demands of increasing COVID-19 caseloads [8]. The rapid surge in hospitalization rates demanded a rethinking of hospital structures, with the creation of dedicated COVID-19 units comprised of both acute and intensive care units (ICUs) from pre-existing surgical and medical services, along with their equipment and staffing [9].

In a situation in which, under such improper conditions, physicians are required to make the most appropriate choices for their patients, according to the guidelines proposed by the national health system, we feel a need to define the current best treatment for COVID-19 starting from the actual experience of the front-line hospitals that dealt with the pandemic. To this aim, we designed a survey regarding the real-life clinical management of inpatients with COVID-19 infection, which was proposed to all the physicians involved in the treatment of patients affected by COVID-19 infections. Here we report their answers, with special interest in those given by the physicians with the highest expertise in order to identify and describe the best clinical practice.

Materials and Methods

Survey Development

Here, we report a physician self-administered cross-sectional survey conducted during the pandemic. Data were collected in Italy from April 14–24, 2020. The questionnaire (online suppl. material; see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000509007 for all online suppl. material) comprised 34 questions. Similar to a recent study performed by some of the authors, it was developed through item generation/reduction as recommended in the guidelines of clinicians' self-administered surveys [10, 11]. We aimed to collect the experience of Italian physicians from a variety of hospital settings on the pivotal clinical issues that were encountered in caring for COVID-19 patients. Questions were defined after discussion among coauthors from the hospitals of Lodi and Milan, two cities severely affected by the outbreak.

The questionnaire was composed of several sections: (1) questions 1–9 aimed to characterize responders, to define them as “COVID experts” or not, and to assess their views on the care of inpatients with COVID-19; (2) the survey ended at question 9 for non-experts as their answer did not meet the primary aim; (3) questions 10–34 explored the respiratory support, including mechanical ventilation, and overall clinical management of inpatients with COVID-19 infection; (4) questions 11–25 explored the clinical role of the nasopharyngeal swab in diagnosis, imaging/monitoring modalities, and therapeutic options, with special regard to the use of NIV in the treatment of acute respiratory failure; (5) questions 26–34 explored the risk management for healthcare staff, vulnerability of the staff to mental health issues, the use of experimental therapy (e.g., tocilizumab), and the evaluation of the possible consequences of the disease. We defined as “experts” the physicians who completed their fellowship more than 5 years ago and had treated at least 20 hospitalized patients with COVID-19, while “sufficiently experts” were the physicians who had treated less than 20 inpatients with COVID-19 infection.

Survey Sample and Administration

We identified 7,000 physicians who provide direct patient care from the Med Stage database (http://www.medstage.it/) and the professional network PleuralHub [12]. Physicians received an initial email that included a cover letter and the survey. The questionnaire was mainly distributed by email over a 10-day period. Non-respondents were contacted by email with one reminder after 72 h from the survey submission to increase participation. Furthermore, the questionnaire was also distributed using a quicker mode of communication, including Facebook and WhatsApp. Anonymous responses were recorded and no ethical approval was required for this survey.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analyses were conducted and the data are reported as counts and percentages. Pearson's χ2 test for count data was used to compare answers among “Expert Physicians” and “Sufficiently Expert Physicians,” and a post-hoc analysis based on χ2 residuals was performed according to Beasley and Schumacker [13].

The customary 0.05 type I error probability was chosen. Due to the large number of comparisons, the experiment-wise error rate was corrected according to Holm-Bonferroni [14], both for the Chi square and the post hoc tests. All analyses were run in R 3.6.2 (Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Core Team, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2019; https://www.R-project.org/).

Results

A total of 1,215 physicians completed the survey questionnaire, representing a 17.4% response rate. The sociodemographic and professional characteristics of all of the responders are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the responders

| All physicians (n = 1,215) | Sufficiently expert physicians (n = 297) | Expert physicians (n = 188) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| What is your age group? | ns | |||

| <30 years | 15 (12.0) | 3 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 31–40 years | 223 (18.4) | 66 (22.2) | 37 (19.7) | |

| 41–50 years | 296 (24.4) | 77 (25.9) | 77 (41.0) | |

| 51–60 years | 357 (29.4) | 95 (32.0) | 47 (25.0) | |

| 61–70 years | 285 (23.5) | 51 (17.2) | 27 (14.4) | |

| >70 years | 39 (3.2) | 5 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Since how many years have you completed your specialization? | ns | |||

| Not yet specialized | 40 (3.3) | 9 (3.0) | − | |

| <5 years | 104 (8.6) | 29 (9.8) | − | |

| 5–10 years | 133 (10.9) | 40 (13.5) | 37 (19.7) | |

| 11–15 years | 182 (15.0) | 40 (13.5) | 45 (23.9) | |

| 16–20 years | 184 (15.1) | 55 (18.5) | 36 (19.1) | |

| >20 years | 572 (47.1) | 124 (4.8) | 70 (37.2) | |

| What is your area of specialization? | 0.012 | |||

| Cardiology | 292 (24.0) | 73 (24.6) | 26 (13.8) | |

| Internal medicine | 205 (16.9) | 70 (23.6) | 56 (29.8) | |

| Pulmonology | 154 (12.7) | 45 (15.2) | 48 (25.5) | |

| General practitioners | 44 (3.6) | 2 (0.7) | 2 (1.1) | |

| Infectious disease | 29 (2.4) | 9 (3.0) | 9 (4.8) | |

| Anesthesia and resuscitation | 38 (3.1) | 15 (5.1) | 11 (5.9) | |

| Emergency medicine | 28 (2.3) | 7 (2.4) | 10 (5.3) | |

| Other medical specialty | 339 (27.9) | 64 (21.5) | 18 (9.6) | 0.010* |

| Other surgical specialty | 86 (7.1) | 12 (4.0) | 8 (4.3) | |

| In which macro-area of Italy do you work? | 0.003 | |||

| North | 628 (51.7) | 165 (55.6) | 142 (75.5) | <0.001* |

| Center | 311 (25.6) | 77 (25.9) | 32 (17.0) | |

| South | 185 (15.2) | 42 (14.1) | 12 (6.4) | |

| Islands | 91 (7.5) | 13 (4.4) | 2 (1.1) | |

| In which type of hospital do you work? | 0.012 | |||

| Community hospital | 459 (37,8) | 119 (40.0) | 79 (42.0) | |

| University hospital | 150 (12.3) | 54 (18.2) | 43 (22.9) | |

| COVID center | 195 (16.1) | 76 (25.8) | 59 (31.4) | |

| Other | 411 (33.8) | 48 (16.0) | 7 (3.7) | |

| How do you define your workplace? | <0.001 | |||

| COVID | 647 (53.3) | 224 (75.4) | 179 (95.2) | |

| Non-COVID | 551 (45.3) | 71 (23.9) | 9 (4.8) | |

| Other/not defined | 17 (1.4) | 2 (0.7) | − | |

| In which main setting do you work? | ns | |||

| Department of Medicine | 295 (24.3) | 93 (31.3) | 63 (33.5) | |

| Pulmonology Department | 65 (5.3) | 22 (7.4) | 22 (11.7) | |

| Department of Infectious Diseases | 18 (1.5) | 9 (3.0) | 4 (2.1) | |

| Department of Emergency Medicine | 123 (10.1) | 52 (17.5) | 28 (14.9) | |

| Intensive care unit | 71 (58.0) | 25 (8.4) | 13 (6.9) | |

| Semi-intensive care unit | 138 (11.4) | 50 (16.8) | 46 (24.5) | |

| Other surgical department | 50 (4.1) | 5 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Other medical department | 455 (37.4) | 41 (13.8) | 12 (6.4) | |

| Do you have experience in the application of CPAP and NIV? | <0.001 | |||

| No, I do not have experience | 526 (43.3) | 48 (16.2) | 11 (5,.9) | |

| Yes, experience of <1 year | 482 (39.7) | 39 (13.1) | 15 (8.0) | |

| Yes, from 1 to 3 year's experience | 109 (9.0) | 46 (15.5) | 14 (7.4) | |

| Yes, experience of >3 years | 98 (8.1) | 164 (55.2) | 148 (78.7) | 0.005* |

| Do you consider yourself an “expert” in the management of patients with acute respiratory failure caused by COVID-19? | ||||

| Yes, I consider myself as “very expert” | 223 (18.4) | − | 188 (100) | |

| Yes, I consider myself as “quite expert” | 297 (24.4) | 297 (100) | − | |

| No, I do not consider myself as “expert” | 695 (57.2) | − | − | |

Values are presented as n (%). p values are from Pearson's χ2 test after correction with the Holm-Bonferroni method, comparing “expert physicians” versus “sufficiently expert physicians.” Bold values indicate p < 0.05.

p value from post hoc χ2 test. COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; CPAP; continuous positive airway pressure; NIV; non-invasive ventilation; ns, not significant.

In total, 188 participants (i.e., 15.5% of the total sample) were COVID-19 experts. Among the study experts, more than half were internal medicine specialists or pulmonologists, were older than 40 years, and had completed their fellowship more than 15 years previously. Among the experts, 75.5% worked in Northern Italy, 17.0% in Central Italy, and 6.4% in Southern Italy, in adequate representation of the spread of SARS-CoV-2 in Italy. Overall, 42.0% of the experts worked in community hospitals, and 22.9% in university hospitals. Nearly all of the experts (95.8%) worked in a COVID center. Detailed clinical management according to the level of physician expertise is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Knowledge of the management of COVID-19 infection disease

| Sufficiently expert physicians (n = 294) | Expert physicians (n = 188) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| What do you consider to be the likelihood of COVID-19 pneumonia in a patient with suggestive symptoms and 1 or more negative NPS?1 | ns | ||

| Very likely | 238 (80.1) | 163 (86.7) | |

| Less likely | 56 (18.9) | 21 (11.2) | |

| Unlikely | 3 (1.0) | 4 (2.1) | |

| Which imaging method do you use to diagnose COVID-19 pneumonia? | ns | ||

| Chest CT | 136 (45.8) | 92 (48.9) | |

| Thorax X-ray | 106 (35.7) | 69 (36.7) | |

| LUS | 55 (18.5) | 27 (14.4) | |

| Which imaging method do you use to monitor COVID-19 respiratory consequences? | ns | ||

| Chest CT | 147 (49.5) | 81 (43.1) | |

| LUS | 86 (29.0) | 67 (35.6) | |

| Thorax X-ray | 64 (21.5) | 40 (21.3) | |

| What do you recommend as a first-line treatment in a patient with COVID-19 pneumonia associated with moderate/severe ARDS?1 | ns | ||

| CPAP | 137 (46.1) | 106 (56.4) | |

| HFNC | 44 (14,8) | 35 (18.6) | |

| Urgent endotracheal intubation | 85 (28.6) | 32 (17.0) | |

| NIV | 31 (10.4) | 15 (8.0) | |

| When do you request and/or perform endotracheal intubation if respiratory failure does not improve/worsens after using CPAP/NIV? | ns | ||

| 1–8 h | 177 (59.6) | 106 (56.4) | |

| Within 1 h | 101 (34.0) | 62 (33.0) | |

| >8 h | 19 (6.4) | 20 (10.6) | |

| Do you use LMWH in high-risk patients with COVID-19 pneumonia without contraindications? | ns | ||

| Yes, always | 270 (91.0) | 185 (98.4) | |

| Yes, most of the time | 25 (8.4) | 2 (1.1) | |

| No | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.5) | |

| If yes, what dose do you use? | 0.018 | ||

| Higher dosages than standard dosages | 105 (35.4) | 97 (51.6) | 0.002* |

| Standard dosages | 192 (64.6) | 91 (48.4) | |

| Do you use corticosteroids in the treatment of acute moderate/severe ARDS?1 | ns | ||

| Yes, since the early phases | 137 (46.1) | 90 (47,9) | |

| Yes, in select cases (resolution of fever ≥72 h or absence of symptoms ≥7 days) | 120 (40.4) | 79 (42.0) | |

| No | 40 (13.5) | 19 (10.1) | |

| Do you use antiviral experimental therapy? | ns | ||

| Chloroquine/hydroxychloroquine + PI | 106 (35.7) | 82 (43.6) | |

| Chloroquine/hydroxychloroquine + AZT | 120 (40.4) | 68 (36.2) | |

| Chloroquine/hydroxychloroquine | 34 (11.4) | 22 (11.7) | |

| Remdesivir | 4 (1.4) | 8 (4.3) | |

| Other | 12 (4.0) | 6 (3.1) | |

| No therapy | 21 (7.1) | 2 (1.1) | |

| Do you request physiotherapy for patients with COVID-19? | ns | ||

| No, the service is not available | 126 (42.4) | 59 (31.4) | |

| No, I don't find it useful | 5 (1.7) | 4 (2.1) | |

| Yes, both | 93 (31.3) | 70 (37.2) | |

| Yes, motor physiotherapy | 39 (13.1) | 29 (15.4) | |

| Yes, respiratory physiotherapy | 34 (11.5) | 26 (13.8) | |

| Do you use the anti-IL6 monoclonal antibody in patients with COVID-19?1 | 0.001 | ||

| In the initial phases of the infection in the presence of risk factors | 86 (29.0) | 77 (41.0) | 0.045* |

| In the advanced phases of the infection <24 h from intubation | 53 (17.8) | 49 (26.1) | |

| In the advanced phases of the infection > 24 h from intubation | 22 (7.4) | 17 (9.0) | |

| I do not use it | 136 (45.8) | 45 (23.9) | |

| Is psychological support for the medical personnel offered in your workplace? | ns | ||

| Yes | 196 (66.0) | 130 (69.1) | |

| No | 101 (34.0) | 58 (30.9) | |

| If yes, did you use it? | |||

| No, I didn't feel the need for it | 165 (55.6) | 103 (54.8) | |

| No, I had no time to attend it | 109 (36.7) | 70 (37.2) | |

| Yes, and it was useful | 19 (6.4) | 12 (6.4) | |

| Yes, but it was useless | 4 (1.3) | 3 (1.6) | |

| Is there a follow-up program for inpatients with pneumonia after discharge?1 | ns | ||

| Yes, by specific territorial outsourcing | 93 (31.3) | 49 (26.1) | |

| Yes, by evaluation of the general practitioner | 80 (27.0) | 36 (19.1) | |

| Yes, by outpatient clinical evaluation shortly | 39 (13.1) | 35 (18.6) | |

| Yes, by telephone service | 26 (8.8) | 19 (10.1) | |

| Yes, by telemedicine | 6 (2.0) | 8 (4.3) | |

| No, it was not expected | 53 (17.8) | 41 (21.8) | |

| Have you reported “sequelae” in hospitalized patients with pneumonia after discharge?1 | ns | ||

| Very serious for both | 16 (5.4) | 12 (6.4) | |

| Modest respiratory consequences | 106 (35.7) | 74 (39.4) | |

| Relevant respiratory consequences | 84 (28.3) | 53 (28.2) | |

| Modest motor consequences | 17 (5.7) | 20 (10.6) | |

| Relevant motor consequences | 33 (11.1) | 12 (6.4) | |

| Negligible | 41 (13.8) | 17 (9.0) |

Values are presented as absolute n (%). p values are from Pearson's χ2 test after correction with the Holm-Bonferroni method. Bold values indicate p < 0.05.

p value from the post hoc χ2 test. COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; NPS, nasopharyngeal swabs; LUS, lung ultrasound; CT, computed tomography; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; HFNC, high-flow nasal cannula; NIV, non-invasive ventilation; LMWH, low-molecular-weight heparin; PI, protease inhibitors; AZT, azithromycin; ns, not significant.

The whole question is explained in the questionnaire in the online supplementary material.

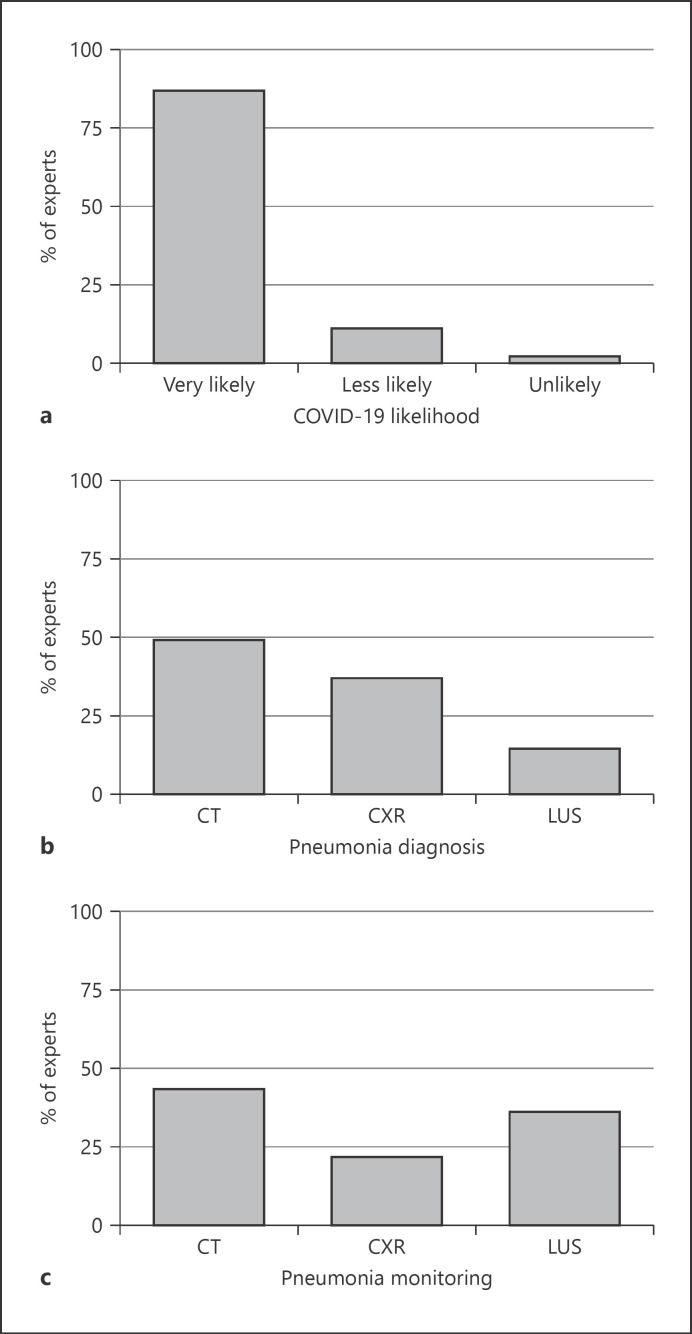

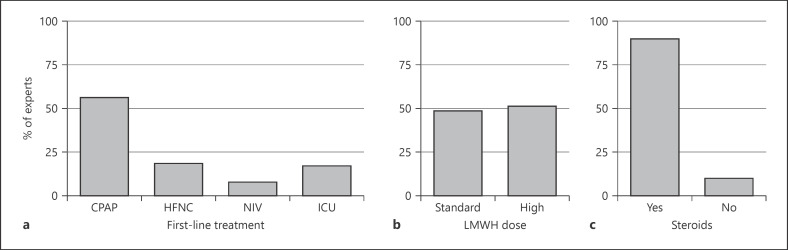

When asked if they considered a diagnosis of COVID-19 infection in a patient with suggestive pneumonia for COVID-19 and one or more negative nasopharyngeal swabs, 86.7% of the experts considered the diagnosis of COVID-19 very likely (Fig. 1a). About half of the experts (48.9%) used chest computed tomography (CT) scan and 36.7% of them used chest X-ray to diagnose COVID-19 pneumonia in hospitalized patients (Fig. 1b). Furthermore, chest CT scan (43.1%) and lung ultrasound (LUS; 35.6%) were the preferred imaging methods for follow-up (Fig. 1c). When asked about the management of COVID-19 pneumonia associated with moderate/severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), 56.4% of the experts reported using CPAP as first-line treatment, while 18.6% used HFNC and only 8% bilevel NIV. An ICU specialist's evaluation for early intubation was requested in only 17% of the cases (Fig. 2a). When CPAP was the preferred treatment, most of the experts (67%) set the positive end-expiratory pressure between 10 and 12 cm H20, whilst 17.5% of them set it at 8 cm H2O, and 13.5% at values higher than 12 cm H2O. About 60% of the experts considered endotracheal intubation within a timeframe between 1 and 8 h if initial treatment with CPAP or NIV failed to improve respiratory failure; 34% considered early intubation within 1 h and only 6% postponed intubation by >8 h.

Fig. 1.

The distribution of the expert physicians' attitudes toward the interventions for the management of COVID-19 inpatients. a Expert physicians' attitudes toward the likelihood of COVID-19 diagnosis in a patient with suggestive pneumonia for COVID-19 and one or more negative nasopharyngeal swabs. b Expert physicians' attitudes toward the type of imaging method firstly used to diagnose COVID-19 pneumonia. c Expert physicians' attitudes toward the type of imaging method firstly used to monitor COVID-19 pneumonia. CXR, chest X-ray; LUS, lung ultrasound.

Fig. 2.

The distribution of the expert physicians' attitudes toward the clinical treatment for the management of COVID-19 inpatients. a Expert physicians' attitudes toward the type of respiratory support as a first-line treatment in a patient with COVID-19 pneumonia associated with moderate/severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS; P/F ratio <200 mm Hg). b Expert physicians' attitudes toward the use of LMWH in high-risk patients with COVID-19 pneumonia (i.e., abnormal coagulation). c Expert physicians' attitudes toward the use of steroids in the treatment of moderate/severe ARDS (P/F ratio <200 mm Hg).

Virtually all the experts prescribed low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) for deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis in high-risk (i.e., abnormal coagulation) COVID-19 pneumonia patients; specifically, about half of them (51.6%) used a dose higher than standard (Fig. 2b). In regard to experimental antiviral options, more than 90% of the experts used chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine. In combination with the above, 43.6% of the experts prescribed protease inhibitors (i.e., lopinavir, ritonavir, or darunavir) and 36.2% used azithromycin. Furthermore, 41.0% of the experts prescribed tocilizumab in patients with risk factors (i.e., comorbidities, older age, male) in the early phases of COVID-19 infection, while 26.1% did so in patients within 24 h after endotracheal intubation. Corticosteroids were prescribed in 90% of COVID-19 pneumonia cases and early use of steroids was preferred by about half of the experts (46.1%; Fig. 2c).

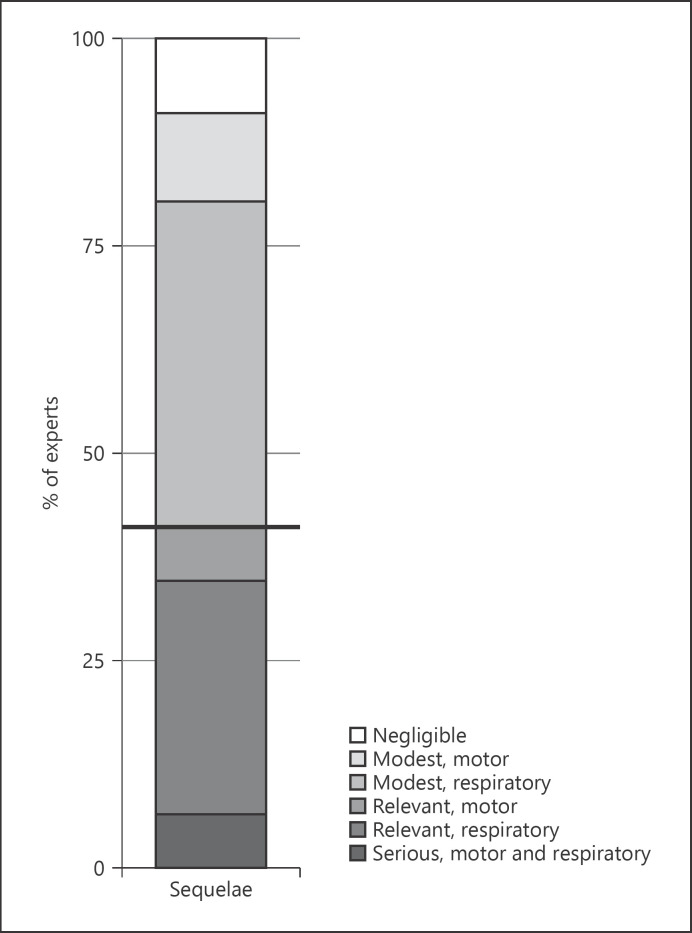

Regarding “respiratory sequelae” in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia after hospital discharge, more than half of the experts (68%) suggested they might be moderate or even severe. Ninety-eight percent of the experts considered respiratory and motor physiotherapy useful for COVID-19, but only 58% of them could offer this option to their patients (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

The distribution of expert physicians' responses toward the evaluation of the sequelae in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 pneumonia after discharge.

In response to the question: “Do you feel the need for the psychological support made available by your hospital?” 6.4% of the experts responded “yes, and it was useful” and 1.6% of the participants responded “yes, but it was useless.” However, the service was significantly underutilized, as 92% of the experts did not access it.

Regarding the safety of the workplace, only 67% of the experts worked in facilities with a triage for healthcare personnel at the entrance of hospital/ward. Detailed information regarding the clinical management of COVID-19 patients according to physician expertise is displayed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Knowledge of the management of COVID-19 infection disease

| Sufficiently expert physicians (n = 294) | Expert physicians (n = 188) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Did you receive training regarding PPE utilization for COVID-19 disease in your workplace? | ns | ||

| Yes | 161 (54.2) | 120 (63.8) | |

| No, I had no time to attend it | 120 (40.4) | 58 (30.9) | |

| No, I considered it useless | 16 (5.4) | 10 (5.3) | |

| Did you receive educational training regarding COVID-19 disease in your workplace? | ns | ||

| Yes | 113 (38.0) | 63 (33.5) | |

| No, I considered it useless | 18 (6,1) | 10 (5.3) | |

| No, I had no time to attend it | 166 (55.9) | 115 (61.2) | |

| Do you follow a standard protocol for patient's discharge consisting of two consecutive negative NPS?1 | 0.004 | ||

| No | 50 (16.8) | 54 (28.7) | 0.013* |

| No, I only obtain 1 negative swab vs. clinical improvement | 32 (10.8) | 33 (17.6) | |

| Yes, always | 169 (56.9) | 70 (37.2) | <0.001* |

| Yes, but it is often hard to follow through due to lack of resources | 46 (15.5) | 31 (16.5) | |

| Which PEEP values during CPAP do you start with in a patient with moderate/severe ARDS? | ns | ||

| Low values (e.g., 8 cm H2O) | 52 (17.5) | 42 (22.3) | |

| Intermediate values (10–12 cm H2O) | 205 (69.0) | 126 (67.0) | |

| High values (>12 cm H2O) | 40 (13.5) | 20 (10.6) | |

| Do you use HFNC to treat hypoxia in patients with COVID-19? | ns | ||

| No | 83 (27.9) | 35 (18.6) | |

| Yes, rarely | 73 (24.6) | 40 (21.3) | |

| Yes, often | 141 (47.5) | 113 (60.1) | |

| If yes, what is the most common outcome? | ns | ||

| Positive | 157 (52.9) | 98 (64.1) | |

| Negative with need for therapy upgrade | 57 (19.2) | 55 (35.9) | |

| How are patients receiving CPAP/NIV fed in your ward? | ns | ||

| CPAP/NIV is not suspended and total parenteral nutrition is used | 104 (35.0) | 60 (31.9) | |

| CPAP/NIV is not suspended and enteral nutrition with NGT is used | 40 (13.5) | 33 (17.6) | |

| CPAP/NIV is not suspended and IRT is used | 39 (13.1) | 21 (11.2) | |

| CPAP/NIV is suspended and the patient eats | 114 (38.4) | 74 (39.4) | |

| How do you manage the communication between patient and family members in your ward? | ns | ||

| Telephone calls | 171 (57.6) | 95 (50.5) | |

| Video calls (e.g., tablet or smartphone) | 113 (38.0) | 91 (48.4) | |

| None of the above | 13 (4.4) | 2 (1.1) | |

| Which interface do you prefer for the purpose of reducing aerosolization of droplets during CPAP/NIV treatment? | ns | ||

| Helmet | 166 (55.9) | 108 (57.4) | |

| Facial mask with double tube circuit and antiviral filter | 81 (27.3) | 52 (27.7) | |

| Single-tube face mask with antiviral filter and whisper | 40 (13.5) | 28 (14.9) | |

| Other | 10 (3.3) | − | |

| Are patients receiving CPAP/NIV monitored in your ward? | ns | ||

| Yes, each patient is under monitoring not connected to the control panel | 120 (40.4) | 76 (40.4) | |

| Yes, there is a telemetry center | 87 (29.3) | 60 (31.9) | |

| No | 90 (30.3) | 52 (27.7) | |

| Do you think that the medical and/or nursing staff is numerically appropriate to satisfy the job request? | ns | ||

| Yes, for both | 115 (38.7) | 78 (41.5) | |

| No, for both | 125 (42.1) | 69 (36.7) | |

| No, inappropriate medical staff | 29 (9.8) | 23 (12.2) | |

| No, inappropriate nursing staff | 28 (9.4) | 18 (9.6) | |

| Are there filter/control systems for healthcare personnel at the entrance of your hospital and/or ward? | ns | ||

| Yes | 197 (66.3) | 126 (67.0) | |

| No | 100 (33.7) | 62 (33.0) |

Values are presented as absolute n (%). p values are from Pearson's χ2 test after correction with the Holm-Bonferroni method for multiple testing problems. Bold values indicate p <0.05.

p value from the post hoc χ2 test. PPE, personal protective equipment; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; NPS, nasopharyngeal swabs; CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; HFNC, high-flow nasal cannula; NIV, non-invasive ventilation; NGT, nasogastric tube; IRT, intravenous rehydration therapy; ns, not significant.

The whole question is explained in the questionnaire in the online supplementary material.

Comparisons between Expert Physicians and Sufficiently Expert Physicians

Two-hundred ninety-seven physicians (24.4%) were defined as sufficiently expert in the management of the inpatients with COVID-19 infections. Comparing “sufficiently experts” and “experts,” we found statistically significant differences in the type of specialty, geographical provenance, hospital type (community vs. university), workplace definition (COVID vs. non-COVID), and ventilatory skills (p = 0.012, p = 0.003, p = 0.012, p < 0.001, and p < 0.001, respectively). No differences emerged for age-group, years since specialization, and hospital unit type (p = 0.191, p = 0.907, and p = 0.596, respectively). Specifically, we showed that, compared with the “sufficiently experts,” the “experts” worked in Northern Italy, in a COVID hospital, and had more than 3 years of the experience in the application of CPAP/NIV (p < 0.001, p < 0.001, and p = 0.005, respectively). Furthermore, regarding physicians' attitudes toward the interventions in the treatment of the COVID-19 infection, we found a statistically significant difference for the LMWH dosage and the use of tocilizumab (p = 0.018 and p = 0.001, respectively). It is noteworthy that the expert physicians used higher doses of LMWH than the “sufficiently experts” in high-risk (i.e., abnormal coagulation) patients with COVID-19 pneumonia (p = 0.002). Regarding the anti-IL6 monoclonal antibody, in addition to the finding that the “experts” prescribed it more frequent than the “sufficiently experts,” they mostly used it in the early phase of COVID-19 infection in hospitalized patients with risk factors (p = 0.045).

Discussion

Here, we report the largest survey of physicians caring for hospitalized patients with COVID-19 to date. Our questionnaire was the result of clinical discussions among physicians working in highly affected hospitals. Respondents were primarily employed in community hospitals and different specialties, thus reflecting the multidisciplinary approach to the pandemic; among expert physicians, internal medicine specialists and pulmonologists were the most represented (29.8 and 25.5%, respectively).

Pneumonia is the leading cause of death in COVID-19. Preliminary data highlight the role of imaging in the detection of pneumonia in these patients [15, 16]. Half of the expert physicians (48.9%) relied on the chest CT scan as the primary test, and chest CT scan (43.1%) and LUS (35.6%) were the preferred methods for monitoring. Among our responders, chest X-ray did not appear to be the first imaging approach to pneumonia (36.7%) and was even less considered for follow-up (21.3%), likely for its known poor sensitivity in interstitial pneumonia [17, 18]. Although the data are limited, and their role unclear, we highlight the growing interest in LUS as an easily available bedside technique that does not require infectious patients to be moved [19, 20].

In the absence of therapies of proven efficacy, respiratory support is key in providing care for patients with COVID-19 pneumonia [21]. Despite the available data being mostly focused on treatment in the ICU [4], our expert panel reported the frequent use of CPAP as first-line treatment for acute respiratory failure (56.4%), followed by HFNC (18.6%) in the general wards, while intensivists were less frequently called for evaluation in the first instance (17%). This latest finding may be a consequence of the overwhelming work of intensivists during the pandemic, which likely reduced their availability outside of the ICU. On this topic, we refer the reader to the recent teaching papers written by Tobin [6] and Gattinoni et al. [5, 22]. Our data simply highlight how the majority of patients affected by severe COVID-19 pneumonia in Italy, and likely in other countries as well, were treated with non-invasive respiratory support (either CPAP, HFNC, or NIV) outside of the ICU. The efficacy and safety of these techniques and settings deserve further dedicated studies. Pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis are frequent complications of COVID-19 [23, 24, 25]. Although the experts strictly apply pharmacological thrombosis prophylaxis, they disagree on the use of standard (48.4%) or higher (51.6%) dosage of LMWH. Randomized evidence is therefore required to better define the issue.

Most of the experts prescribed antiviral drugs, particularly the chloroquine family, and corticosteroids. In the absence of conclusive data regarding the safety and usefulness of these pharmacological agents in the management of COVID-19 pneumonia, their use is likely based on clinical observation and opinion leaders [26, 27].

The consequences of COVID-19 are an open question not only for the scientific community, but also for healthcare systems, governments, and society [28, 29]. After the acute phase, one third of the experts (34.6%) diagnosed a clinically relevant respiratory impairment.

A dedicated psychological service was usually available for physicians (69%). However, its accessibility and perceived efficacy seems to require improving as 37% of physicians had no time to attend it, and only 6% of the responders judged it to be useful.

As a final caveat, we stress that the present survey was not intended to provide guidelines in caring for COVID-19, but to report the real-life clinical practice in the context of a currently limited evidence-based literature. The final aim of this project is to foster clinical discussion, shifting it from hospital wards to the scientific community in order to stimulate clinical research on the many open topics.

Study Limitations

The study was a self-administered survey of physician practice conducted over a few days during the acute phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. Like all surveys, potential issues such as response bias and interpretation must be taken into account [30]. We are aware that expert opinion is only the first level in the pyramid of evidence; however, we consider it of great usefulness given the urgent need for practical information amongst the physician community. We also acknowledge that there are other more structured ways to survey experts, such as through a consensus method [31]. However, because of time constraints and in light of our group's past research experience [10], we considered our approach to be the most appropriate choice.

Another issue we encountered was the definition of “experts” in the management of COVID-19. This unprecedented disease has a variety of manifestations and severity degrees, making it a challenging task to define the level of clinical practice to identify a physician as “expert.” COVID-19 is managed mainly outside the ICUs, and an adequate care for inpatients requires skills and competences that encompass different specialties. We therefore selected as “experts” those physicians who had the most solid clinical background and had managed a larger number of COVID-19 patients. On the other hand, we chose to assess the clinical practice of different medical specialties because it well reflects the multidisciplinary in-hospital approach to COVID-19, and we value this as one of the main strengths of the study.

Although many respondents took part in the study, the overall response rate was relatively low, thus limiting the generalizability of the results. However, the potential for a low response rate among physicians is known [11], and the percentage of responders to this study was higher than that in similar studies [32].

The survey was administered in Italy. This choice was based on the fact that Italy was affected early and particularly hard amid Western countries and, therefore, it is particularly representative of the pandemic [2, 4]. Most of the responders were from the north of Italy, therefore mirroring the geographic distribution of the disease.

In conclusion, our survey shows the current best practice in COVID-19 over a wide range of clinical aspects, ranging from diagnosis to treatment. Some major topics, such as the role of non-invasive respiratory support and drug treatments, e.g., antivirals, steroids, or heparin dose, show disagreement between experts, likely reflecting the absence of high-quality evidence studies. We also report the significant respiratory sequelae following COVID-19 pneumonia, for which proper respiratory and physical therapy programs should be promptly made available. This study provides a clinical guide to focus further research on the complex issue of caring for patients with COVID-19.

Statement of Ethics

There were no ethical considerations relevant to this work.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

G.F.S.P. is the recipient of a grant from the University of Milan (Unitech for research on COVID-19) for the RECOVER study (recovernet.org), a multicenter clinical registry of hospitalized patients affected by COVID-19. This survey stems from the expert opinion drawn by the analysis of the clinical features of patients and their hospital management, and is the result of the networking of the project.

Author Contributions

G.F.S.P. conceived the idea. M.A., G.F.S.P., G.M.P., S.P., S.D.P., F.C, and G.C. developed the questionnaire. All authors reviewed the questionnaire. M.A., G.F.S.P., P.F., G.M.P., and S.P. guided the survey administration. G.F.S.P., M.A., G.M.P., and M.M.C. wrote the first draft of the paper. All authors contributed to data interpretation and reviewed the manuscript. F.C., G.M.P., S.D.P., G.C., S.C., and A.C. critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data

Acknowledgements

Firstly, we thank all physicians who answered our questions during the overwhelming days of the pandemic. The authors gratefully acknowledge the support by Med Stage, in particular Emanuele Cavo, and PleuralHub, with special thanks to Giampietro Marchetti for the administration of the survey. We also are very grateful to Mattia Toma, Lina Visocchi, and Antonella Frattari for their support on the project. We thank the University of Milan and the hospital of Lodi (Ospedale Maggiore Lodi) for fostering clinical research into COVID-19.

Collaborators for the RECOVER Investigators Study Group: Umberto Amato (Med Stage), Giampietro Marchetti (Cardiothoracic Department, Division of Pulmonary Medicine, Spedali Civili Hospital of Brescia), Veronica Pacetti (ASST Lodi, UOC Medicina)

References

- 1.Wang R, Zhang X, Irwin DM, Shen Y. Emergence of SARS-like coronavirus poses new challenge in China. J Infect. 2020 Mar;80((3)):350–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu JT, Leung K, Leung GM. Nowcasting and forecasting the potential domestic and international spread of the 2019-nCoV outbreak originating in Wuhan, China: a modelling study. Lancet. 2020 Feb;395((10225)):689–97. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30260-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nacoti M, Ciocca A, Giupponi A, Brambillasca P, Lussana F, Pisano M, et al. At the Epicenter of the Covid-19 Pandemic and Humanitarian Crises in Italy: Changing Perspectives on Preparation and Mitigation. NEJM Catalyst; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, Antonelli M, Cabrini L, Castelli A, et al. COVID-19 Lombardy ICU Network Baseline Characteristics and Outcomes of 1591 Patients Infected With SARS-CoV-2 Admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy Region, Italy. JAMA. 2020 Apr;323((16)):1574–81. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gattinoni L, Chiumello D, Caironi P, Busana M, Romitti F, Brazzi L, et al. Intensive COVID-19 pneumonia: different respiratory treatments for different phenotypes? Intensive Care Med. 2020;14:1–4. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06033-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tobin MJ. Basing Respiratory Management of COVID-19 on Physiological Principles. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020 Jun;201((11)):1319–20. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202004-1076ED. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cunningham AC, Goh HP, Koh D. Treatment of COVID-19: old tricks for new challenges. Crit Care. 2020 Mar;24((1)):91. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-2818-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sotgiu G, Gerli AG, Centanni S, Miozzo M, Canonica GW, B Soriano J, et al. Advanced forecasting of SARS-CoV-2-related deaths in Italy, Germany, Spain, and New York State. Allergy. 2020 doi: 10.1111/all.14327. doi: 10.1111/all.14327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization . Strengthening the health systems response to COVID-19, technical guidance No. 2: creating surge capacity for acute and intensive care. Recommendations for the WHO European Region. Copenhagen: WHO; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zanforlin A, Tursi F, Marchetti G, Pellegrino GM, Vigo B, Smargiassi A, et al. AdET Study Group Clinical Use and Barriers of Thoracic Ultrasound: A Survey of Italian Pulmonologists. Respiration. 2020;99((2)):171–6. doi: 10.1159/000504632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burns KE, Duffett M, Kho ME, Meade MO, Adhikari NK, Sinuff T, et al. ACCADEMY Group A guide for the design and conduct of self-administered surveys of clinicians. CMAJ. 2008 Jul;179((3)):245–52. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.080372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zanforlin A, Livi V, Santoriello C, Ceruti P, Trigiani M, Valerio M, et al. Ultrasound Fissure Observation: Assessment of Lung by Pleural-Hub Affiliates. Chest. 2018 Aug;154((2)):357–62. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beasley TM, Schumacher RE. Multiple regression approach to analyzing contingency tables: post hoc and planned comparison procedures. J Exp Educ. 1995;64((1)):79–93. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bender R, Lange S. Adjusting for multiple testing—when and how? J Clin Epidemiol. 2001 Apr;54((4)):343–9. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00314-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shi H, Han X, Jiang N, Cao Y, Alwalid O, Gu J, et al. Radiological findings from 81 patients with COVID-19 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020 Apr;20((4)):425–34. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30086-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bai HX, Hsieh B, Xiong Z, Halsey K, Choi JW, Tran TM, et al. Performance of radiologists in differentiating COVID-19 from viral pneumonia on chest CT. Radiology. 2020 Mar;10:200823. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoon SH, Lee KH, Kim JY, Lee YK, Ko H, Kim KH, et al. Chest radiographic and ct findings of the 2019 novel coronavirus disease (Covid-19): analysis of nine patients treated in korea. Korean J Radiol. 2020 Apr;21((4)):494–500. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2020.0132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mondoni M, Fois A, Centanni S, Sotgiu G. Could BAL Xpert(®) MTB/RIF replace transbronchial lung biopsy everywhere for suspected pulmonary TB patients? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2016 Aug;20((8)):1135. doi: 10.55888/ijtld.16.0379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soldati G, Smargiassi A, Inchingolo R, Buonsenso D, Perrone T, Briganti DF, et al. Is there a role for lung ultrasound during the COVID-19 pandemic? J Ultrasound Med. 2020 Mar;••• doi: 10.1002/jum.15284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soldati G, Smargiassi A, Inchingolo R, Buonsenso D, Perrone T, Briganti DF, et al. Proposal for international standardization of the use of lung ultrasound for COVID-19 patients; a simple, quantitative, reproducible method. J Ultrasound Med. 2020 Mar; doi: 10.1002/jum.15285. doi:10.1002/jum.15285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Phua J, Weng L, Ling L, Egi M, Lim CM, Divatia JV, et al. Asian Critical Care Clinical Trials Group Intensive care management of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): challenges and recommendations. Lancet Respir Med. 2020 May;8((5)):506–17. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30161-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gattinoni L, Coppola S, Cressoni M, Busana M, Rossi S, Chiumello D. COVID-19 Does Not Lead to a “Typical” Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020 May;201((10)):1299–300. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202003-0817LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klok FA, Kruip MJHA, van der Meer NJM, Arbous MS, Gommers DAMPJ, Kant KM, et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res. 2020;191:145–7. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu J, Wang L, Zhao L, Li F, Liu J, Zhang L, et al. Risk assessment of venous thromboembolism and bleeding in COVID-19 patients. Research Square. 2020 doi: 10.1111/crj.13467. doi: 10.21203/rs-18340/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Llitjos JF, Leclerc M, Chochois C, Monsallier JM, Ramakers M, Auvray M, et al. High incidence of venous thromboembolic events in anticoagulated severe COVID-19 patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2020 Apr; doi: 10.1111/jth.14869. doi: 10.1111/jth.14869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shang L, Zhao J, Hu Y, Du R, Cao B. On the use of corticosteroids for 2019-nCoV pneumonia. Lancet. 2020 Feb;395((10225)):683–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30361-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mehta P, McAuley DF, Brown M, Sanchez E, Tattersall RS, Manson JJ, HLH Across Speciality Collaboration, UK COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet. 2020 Mar;395((10229)):1033–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. COVID-19: delay, mitigate, and communicate. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;2600((20)):30128. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30128-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.The Lancet Emerging understandings of 2019-nCoV. Lancet. 2020 Feb;395((10221)):311. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30186-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DesRoches CM, Campbell EG, Rao SR, Donelan K, Ferris TG, Jha A, et al. Electronic health records in ambulatory care—a national survey of physicians. N Engl J Med. 2008 Jul;359((1)):50–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0802005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Di Marco F, Balbo P, de Blasio F, Cardaci V, Crimi N, Girbino G, et al. Early management of COPD: where are we now and where do we go from here? A Delphi consensus project. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2019 Feb;14:353–60. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S176662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ehrmann S, Roche-Campo F, Sferrazza Papa GF, Isabey D, Brochard L, Apiou-Sbirlea G, REVA research network Aerosol therapy during mechanical ventilation: an international survey. Intensive Care Med. 2013 Jun;39((6)):1048–56. doi: 10.1007/s00134-013-2872-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data